Introduction

Eggshell quality has been a major economic concern to egg producers as it could reason for serious economic losses (Joshi et al., Reference Joshi, Desai, Ranade and Avari2019; Gül et al., Reference Gül, Olgun, Yıldız, Tüzün and Sarmiento-García2022). Eggshell has different functions such as protects against physical damage and pathogens coming from the external environment, and providing nutrients necessary for embryonic development, especially calcium. Therefore, maintaining the eggshell quality of laying hens remains a challenge for researchers (Ketta et al., Reference Ketta, Tůmová, Englmaierová and Chodová2020)

Eggshell formation depends on different factors such as genotype, environment and diet calcium content (Ketta and Tůamová, Reference Ketta and Tůamová2016; Tufarelli et al., Reference Tufarelli, Baghban-Kanani, Azimi-Youvalari, Hosseintabar-Ghasemabad, Slozhenkina, Gorlov, Seidavi, Ayaşan and Laudadio2021). Obtaining the desired eggshell quality is closely related to the calcium addition at optimum level to poultry diets (Al-Zahrani and Roberts, Reference Al-Zahrani and Roberts2015). Adequate calcium rates depending on the breed used, the calcium/phosphorus ratio, vitamin D content, age and the productive phase (Attia et al., Reference Attia, Al-Harthi and Abo El-Maaty2020; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Teng, Xu, Chi, Ge and Xu2020; Stanquevis et al., Reference Stanquevis, Furlan, Marcato, Oliveira-Bruxel, Perine, Finco, Grecco, Benites and Zancanela2021; Tufarelli et al., Reference Tufarelli, Baghban-Kanani, Azimi-Youvalari, Hosseintabar-Ghasemabad, Slozhenkina, Gorlov, Seidavi, Ayaşan and Laudadio2021). Among those factors, the relationship between layers, age and the calcium content on quality egg have been extensively studied (Swiatkiewicz et al., Reference Swiatkiewicz, Arczewska-Włosek, Szczurek and Puchała2018; Kakhki et al., Reference Kakhki, Heuthorst, Mills, Neijat and Kiarie2019; Attia et al., Reference Attia, Al-Harthi and Abo El-Maaty2020; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang, Qi, Cui, Wu, Zhang and Xu2021). Over the course of the egg production cycle, egg weight increases, internal quality deteriorates, eggshell becomes thinner and the hen ceases to lay eggs. Consequently, efficient calcium metabolism is crucial to ensuring saleable eggs (Kakhki et al., Reference Kakhki, Heuthorst, Mills, Neijat and Kiarie2019). To prevent decreasing eggshell quality as hens age, nutritionists often modify dietary calcium. Therefore, recommendations for calcium in the diet are not static, and the results of previous experiments are often contradictory (Ketta et al., Reference Ketta, Tůmová, Englmaierová and Chodová2020).

Different calcium sources (such as limestone or oyster shell) are used in poultry nutrition (Manangi et al., Reference Manangi, Maharjan and Coon2018; Bagheri et al., Reference Bagheri, Toghyani, Tabatabaei, Tabeidian and Ostadsharif2021; López et al., Reference López, González, Monroy-Barreto, Perez and Olvera2021; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Kothari, Niu, Lim, Park, Ko, Eom and Kim2021). Among that, calcium pidolate (also known as calcium pyroglutamate or calcium pyrrolidone carboxylate) is an organic source of calcium and can be used as a supplement in the diet of laying hens (Bagheri et al., Reference Bagheri, Toghyani, Tabatabaei, Tabeidian and Ostadsharif2021). There is an increasing interest in this supplement in the poultry industry. In calcium pidolate, the calcium ion (13%) is bound to two molecules of pyrrolidone carboxylic acid (87%), which act as a protein support (Joshi et al., Reference Joshi, Desai, Ranade and Avari2019). This protein improves intestinal absorption, facilitates binding to tissues and blood circulation. The main advantage of calcium pidolate is its high solubility and excellent gastrointestinal tolerance, which favours its absorption in the intestine (Falguera et al., Reference Falguera, Mengual, Vicente and Ibarz2010). Previous studies suggest that the inclusion of calcium pidolate may improve certain parameters (such appearance, mechanical resistance and functional properties) of egg and bone (Agblo and Duclos, Reference Agblo and Duclos2011; Al-Zahrani and Roberts, Reference Al-Zahrani and Roberts2015; Joshi et al., Reference Joshi, Desai, Ranade and Avari2019). However, research on its use in laying quails is scarce.

Japanese quails were a valuable animal for avian research. It is due to their small size, they are easily handled and can be kept in a limited space (Lukanov, Reference Lukanov2019; Lukanov and Pavlova, Reference Lukanov and Pavlova2020). Most quail eggs are produced in East Asia and Brazil, while most quail meat is produced in Europe, the USA and China (Lukanov, Reference Lukanov2019). Despite the difficulty of estimating quail populations involved in industrial farming, they have steadily increased in recent decades. Amoah et al. (Reference Amoah, Martin, Barroga, Garillo and Domingo2012) proposed that to improve this development, one of the areas that needs particular attention is nutrition of the birds. The lack of information on nutritional requirements can cause food costs to rise, as well as underestimating or overestimating their nutritional needs, resulting in losses (Sarcinelli et al., Reference Sarcinelli, Sakomura, Dorigam, Silva, Venturini, Lima and Gonçalves2020). The minerals, which make up 5% of an animal's body, are among the most important nutrients. Among all minerals, calcium and phosphorus stand out due to their contribution to skeleton formation (80–85%) and their role in egg shells and muscle development, making them essential to animal functions (Stanquevis et al., Reference Stanquevis, Furlan, Marcato, Oliveira-Bruxel, Perine, Finco, Grecco, Benites and Zancanela2021).

To our knowledge, there are no studies evaluating the relationship between calcium pidolate supplementation and its effect on aged laying hens. In addition, the optimal amount of calcium pidolate in the diet of old-laying quail was not studied. So, in the present study, attempts were made to determine the effect of calcium pidolate in the diet of aged laying quails, on the performance and egg quality traits.

Materials and methods

Animals, diets and management

The trial was conducted on 120 female Japanese quails (Coturnix coturnix Japonica) for 10 weeks at the Department of Animal Science, Faculty of Agriculture, Selcuk University, Turkey (38°1′36, 32°30′45″). Quails of similar body weight (245.8 ± 6.3 g) and 27 weeks of age were obtained from a commercial company. The trial was conducted in four experimental groups consisting of six replicates, each containing five female quails.

Animals were allocated randomly in four identical cages (30 × 45 cm) that had the same environmental conditions. Birds were housed in a well-ventilated room with a lighting programme of 16 h. A temperature of 20 ± 2.0°C was maintained in each pen. Each pen was provided with individual feeder and drinker to allow ad libitum intake.

Control group G1 was fed the basal diet, while experimental groups G2, G3 and G4 were given calcium pidolate additions of 0.25, 0.50 and 1.25 g/kg, respectively, to have 25.1, 25.4, 25.8 and 26.5 g/kg calcium in their diets. Calcium pidolate (in relation to dry matter) consisting of 13% calcium and 87% pidolic acid was supplied by a company in the animal nutrition sector (NutriLab, Konya, Turkey).

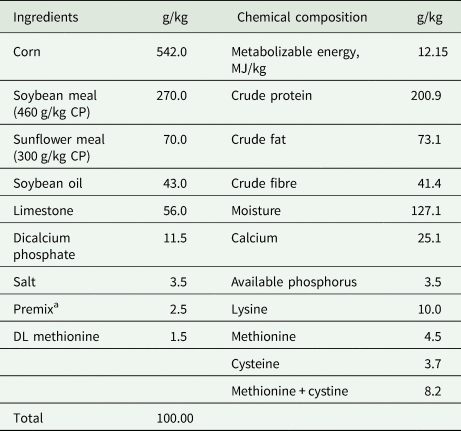

The basal diet was formulated as isonitrogenic and isocaloric according to the recommendation of National Research Council (1994) for layer quails layer requirements. The chemical composition of basal diet was analysed according to AOAC (2006) proceedings: water content by drying at 105°C; crude protein content by the Kjeldahl method; fat content by Soxhlet extraction; and ash content by incineration were determined. Table 1 shows the ingredients of basal diet and its chemical composition.

Table 1. Ingredients of basal diet and its chemical composition

a Premix provided the following per kilogram of diet; manganese (manganese oxide): 80 mg, iron (ferrous carbonate): 60 mg, copper (cupric sulphate pentahydrate): 5 mg, iodine: 1 mg, selenium: 0.15 mg, vitamin A (trans-retinyl acetate): 8.800 IU, vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol): 2.200 IU, vitamin E (tocopherol): 11 mg, nicotine acid: 44 mg, Cal-D-Pan: 8.8 mg, vitamin B2 (Riboflavin): 4.4 mg, thiamine: 2.5 mg, vitamin B12 (cyanocobalamin): 6.6 mg, folic acid: 1 mg, biotin: 0.11 mg, choline: 220 mg.

Determination of performance traits

At the beginning of the experiment, the quails were randomly allotted to the five trial groups; body weight and final body weight were determined by weighing the groups at the beginning and at the end of the experiment with precision weighing balance (±0.01 g). Body weight change was determined by the difference between the initial and final weight (g) of the groups in the trial.

The experimental feeds were administered to the treatment subgroups by weighing and, subsequently, the feed intake was evaluated as the feed consumed (g) per day and animal. At the same time of each day (at 10:00 a.m.) eggs were collected and recorded. Egg production was determined by dividing the number of eggs obtained in a day by the number of quails and multiplying by 100, and it was given as percentage (%).

Egg weight was determined by weighing one by one of all eggs collected in the last 3 days of the experiment with a precision weighing balance (±0.01 g). From these data, egg mass was calculated as daily egg weight per quail (g) according to the equation proposed by Gül et al. (Reference Gül, Olgun, Yıldız, Tüzün and Sarmiento-García2022) (Eqn (1))

Finally, feed conversion ratio (FCR) was determined according to next equation (Eqn (2))

Determination of egg quality traits

During the experiment, broken, cracked and damaged eggs were recorded and calculated as percentage of the number of eggs. Egg internal and external quality traits were determined at room temperature from all eggs collected in the last 3 days of trial. Eggshell breaking strength was assessed by applying supported-systematic pressure to the brunt of the eggs (Egg Force Reader, Orka Food Technology, Israel).

Immediately after the determination of the eggshell breaking strength, the eggs were broken on a clean, glass surface, and after the residues in the eggshell were cleaned, the shells were dried at room temperature for 3 days and weighed, and relative weights were calculated as a ratio (%) of the egg weight. Eggshell thickness was calculated by averaging the measurements obtained from three sections (equator, brunt and pointed parts) of the eggshell using a micrometre (Mitutoyo, 0.01 mm, Japan). Eggs, whose external quality characteristics were determined, were broken on a surface and their albumen and yolk heights were measured with a height gauge and their length and width were measured with a 0.01 mm digital calliper.

The variables calculated from these data and the equations used are as follows. Albumen index was determined by Eqn (3) as Anene et al. (Reference Anene, Akter, Thomson, Groves, Liu and O'shea2021) showed.

To determinate yolk index, Eqn (4) was used as Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Wang and Shan2019) proposed.

Finally, Haugh unit for each egg was calculated using data of egg weight and albumen height according to Eqn (5) proposed by Stadelman and Cotterill (Reference Stadelman and Cotterill1995)

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed by one-way ANOVA using the SPSS 23.0 software package (IBM Corp. Released 2017, Armonk, NY, USA: IBM Corp), using the cage mean as an experimental unit. A probability value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Orthogonal polynomial contrasts were used to assess the significance of linear and quadratic models to describe the response of the dependent variable to a rising calcium pidolate concentration.

Results

Performance traits

The data in Table 2 showed that the calcium pidolate did not significantly affect body weight change, feed intake and FCR (P > 0.05).

Table 2. Effect of calcium pidolate supplementation on performance traits of aged laying quails

s.e.m., standard error mean.

Calcium pidolate was added at the levels of G1: 0 g/kg, G2:0.25 g/kg, G3:0.50 g/kg and G4: 1.00 g/kg.

Body weight gain and egg weight were expressed are in g. Egg production was expressed in percentage (%). Egg mass and feed intake were expressed in g/day/quail. Feed conversion ratio was g feed/g egg.

a,b Different superscripts indicate significant differences within a row (P < 0.05).

Adding calcium pidolate to the diet significantly showed a significant linear response for egg production (P = 0.028). The highest egg production value was found in group G1. The egg weight and egg mass (P > 0.05) did not differ based on the amount of calcium pidolate added to the diet.

Eggshell quality traits

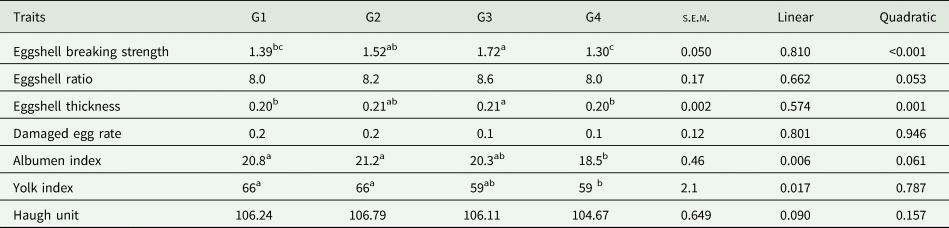

Table 3 provides data on the changes in egg quality traits with the addition of calcium pidolate to the aged laying quail diet. The albumen (P = 0.006) and yolk index (P = 0.017) were linearly affected by the treatment. In both cases, the G4 had the lowest value. In the experiment, the eggshell breaking strength (P < 0.001) and the eggshell thickness (P = 0.001) were affected quadratically by the treatments. In terms of eggshell breaking strength, the highest value was observed in the G3 group (1.72 kg), and the lowest value was observed in the G4 group (1.30 kg). A similar trend was observed to eggshell thickness.

Table 3. Effects of different levels of calcium pidolate on egg quality traits in aged laying quails

s.e.m., standard error mean.

Calcium pidolate was added at the concentration of G1: 0 g/kg, G2:0.25 g/kg, G3:0.50 g/kg and G4: 1.00 g/kg.

Eggshell breaking strength was expressed in kg. Eggshell ratio and damaged egg rate were expressed as percentage. Eggshell thickness was expressed in mm.

a,b,c Different superscripts indicate significant differences within a row (P < 0.05).

The eggshell ratio, damaged egg rate and Haugh unit (P > 0.05) were not affected by the treatment. Despite no significant differences in damaged eggs, the rate was numerically lower in aged laying quails fed with medium-high (G3) and high calcium pidolate (G4) compared to those fed with low calcium pidolate and the control group.

Discussion

Dietary calcium is necessary for both bird development and egg quality (Ahmed et al., Reference Ahmed, Kamil, Hasso, Abduljawaad, Saleh and Mahmood2022). There is a close relationship between calcium metabolism and poultry aging (Manangi et al., Reference Manangi, Maharjan and Coon2018; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Teng, Xu, Chi, Ge and Xu2020; López et al., Reference López, González, Monroy-Barreto, Perez and Olvera2021; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Kothari, Niu, Lim, Park, Ko, Eom and Kim2021), so determining the optimal levels of calcium in the diet is essential to ensure the economic viability of the production. Much is known about the calcium requirements of laying hens, but little information is available on the calcium requirements for laying quails. Therefore, in order to determine the relationship between age and egg quality, different levels of calcium pidolate were used in 27–37 weeks old quail diet.

In the current research, it was determined that the addition of calcium pidolate to the diet had no effect on FCR, feed intake and body weight change, which was in accordance with other reports with aged layers (An et al., Reference An, Kim and An2016; Ganjigohari et al., Reference Ganjigohari, Ziaei, Ramzani Ghara and Tasharrofi2018; Kakhki et al., Reference Kakhki, Heuthorst, Mills, Neijat and Kiarie2019; Islam and Nishibori, Reference Islam and Nishibori2021; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang, Qi, Cui, Wu, Zhang and Xu2021). Similar results had been reported by Arczewska-Włosek et al. (Reference Arczewska-Włosek, Szczurek and Puchała2018) who did not find any influence of dietary calcium level (32–37 g/kg in the diet) on the performance of laying hens (21–70 weeks of age). However, these findings are contradictory. In laying ducks, Xia et al. (Reference Xia, Chen, Abouelezz, Azzam, Ruan, Wang, Zhang, Luo, Wang and Zheng2019) reported an improvement in FCR during the early- and entire laying periods as dietary calcium level increased from 28 to 44 g/kg, while the feed intake was unaffected by calcium level. Valderrama and Roulleau (Reference Valderrama and Roulleau2013) observed an improvement on daily body weight gain when they administered 300 ppm of calcium pidolate in the diet of 55-week-old hens. According to Oliveira and Almeida (Reference Oliveira and Almeida2004), those differences could be explained because quails are more tolerant to calcium variations, and excrete excess of this mineral more efficiently compared to other species without affecting performance parameters. In addition, Ganjigohari et al. (Reference Ganjigohari, Ziaei, Ramzani Ghara and Tasharrofi2018) reported that laying hens will increase feed intake to compensate for calcium deficiency in the diet, resulting in changes in performance if the diet lacks calcium. The results of this study suggested that calcium pidolate supplementation in aged laying quails is adequate for the maintenance of the same performance parameters as control group.

Egg production and dietary calcium level in the diet are a controversial issue. Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Zhao, Tian, Zhang, Ruan, Li, Wang, Zheng and Lin2015) showed that the egg production and the egg mass of laying ducks were reduced to 84 and 47% of control (36 g/kg calcium) for 18 and 3.8 g/kg calcium, respectively. Similarly, Xia et al. (Reference Xia, Chen, Abouelezz, Azzam, Ruan, Wang, Zhang, Luo, Wang and Zheng2019), who studied breed ducks, reported that egg production in the early laying period was directly proportional to the increased calcium level, which is consistent with the findings of Zhao et al. (Reference Zhao, Teng, Xu, Chi, Ge and Xu2020). In contrast, Bello et al. (Reference Bello, Dersjant-Li and Korver2020) and Ganjigohari et al. (Reference Ganjigohari, Ziaei, Ramzani Ghara and Tasharrofi2018) described that egg production, egg weight and egg mass were not affected by calcium levels. According to Ganjigohari et al. (Reference Ganjigohari, Ziaei, Ramzani Ghara and Tasharrofi2018) the most important factor affecting egg weight is not only feed intake but also the level of protein in the diet. In the current experiment, while egg mass and egg weight were not affected by the inclusion of calcium pidolate, changes were observed for egg production. In the current experiment, the 1.0 g/kg calcium pidolate (G4) supplementation resulted in the lowest egg production. Previously, Pelicia et al. (Reference Pelicia, Garcia, Móri, Faitarone, Silva, Molino, Vercese and Berto2009) reported that the increase in calcium levels could occur in a decrease in egg production due to a reduced feed intake. These findings could justify the results of our study, although it is true that differences in feed intake were observed, it was not significant.

Contrary to expectations, eggshell breaking strength and eggshell thickness were significantly higher in G3 than G4; however, no differences between treatments were found in damaged egg rate. Partially agree with these results, previous authors (An et al., Reference An, Kim and An2016; Joshi et al., Reference Joshi, Desai, Ranade and Avari2019; Islam and Nishibori, Reference Islam and Nishibori2021; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang, Qi, Cui, Wu, Zhang and Xu2021) have shown an increase in eggshell thickness and a reduce in damaged eggs when calcium levels increased. In their recent study, Swiatkiewicz et al. (Reference Swiatkiewicz, Arczewska-Włosek, Szczurek and Puchała2018) showed that egg and eggshell quality parameters in 30 weeks old hen were unaffected by dietary calcium; however, eggs of older layers (43–69 weeks old) fed the diet with lower calcium level had reduced eggshell percentage, eggshell thickness and eggshell breaking strength. The improvement in egg quality traits of quails fed 0.5 g/kg of calcium pidolate suggests an increased calcium availability for eggshell formation which is consistent with the studies of Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Wang, Qi, Cui, Wu, Zhang and Xu2021) and Attia et al. (Reference Attia, Al-Harthi and Abo El-Maaty2020). The results showed that 0.5 g/kg of calcium pidolate was adequate for improving egg quality characteristics in aged laying quails and increasing the calcium pidolate level above 0.50 g/kg had no positive effects. The present findings contradicted the findings of Cufadar et al. (Reference Cufadar, Olgun and Yıldız2011) because they reported that dietary calcium level did not significantly affect either eggshell breaking strength or eggshell thickness. There are several explanations for the differences, including a higher calcium content in the quail's diet and older age.

The results of the current study demonstrated that increasing calcium pidolate from 0.25 to 1 g/kg in the diets (G2 to G4) of aged laying quails decreased the albumen index. This fact confirms a lower tolerance of quails to levels above 0.50 g/kg of calcium pidolate. These findings are in accordance with Joshi et al. (Reference Joshi, Desai, Ranade and Avari2019) who reported that the addition of calcium pidolate (0.50 g/kg) had negative effect on the egg albumen index. Also, Attia et al. (Reference Attia, Al-Harthi and Abo El-Maaty2020) observed that there is a linear reduction in albumen index when dietary calcium exceeds 35 g/kg. On the contrary, Al-Zahrani and Roberts (Reference Al-Zahrani and Roberts2015) stated that the addition of calcium pidolate (0.30 and 0.60 g/kg) to the diet increased the albumen index in laying hens.

This study showed that the yolk index decreased linearly as calcium pidolate levels increased. These findings are consistent with those reported by Islam and Nishibori (Reference Islam and Nishibori2021). They reported that diets with 80 g/kg calcium sources performed better than diets with 40 g/kg calcium sources for yolk index. In another study, Attia et al. (Reference Attia, Al-Harthi and Abo El-Maaty2020) stated that above 35 g/kg calcium in the diet of laying hens negatively affected the yolk index. Those authors describe that the negative impact of calcium on egg quality is more pronounced when dietary calcium levels are inadequate. On the other hand, Joshi et al. (Reference Joshi, Desai, Ranade and Avari2019) observed that supplementation of calcium pidolate had no negative impact on yolk index of eggs. It is likely that the differences between the parameters of previous studies and ours may be due to variations in the level of calcium used, and therefore, in the assimilation of calcium by the quails.

The increased strength of eggshell and thickness, as well as the increase in the egg production, is an important goal that has economic importance in commercial terms (Attia et al., Reference Attia, Al-Harthi and Abo El-Maaty2020). In accordance with that, the results of our study showed that a dietary level of 0.50 g/kg calcium pidolate was the best for aged laying quails’ production. When the dietary calcium pidolate level was raised to 0.50 g/kg (G3), the egg production, eggshell breaking strength and eggshell thickness declined dramatically. In addition, the increase in calcium pidolate negatively affected other quality traits such the albumen index and the yolk index.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: A. Sarmiento-García, A. Gökmen, B. Sevim, O. Olgun. Data curation: A. Sarmiento-García, S. A. Gökmen, B. Sevim, O. Olgun. Formal analysis: A. Sarmiento-García, S. A. Gökmen, B. Sevim, O. Olgun. Funding acquisition: B. Sevim, O. Olgun. Investigation: B. Sevim, O. Olgun, S. A. Gökmen. Methodology: A. Sarmiento-García, B. Sevim, O. Olgun. Project administration: B. Sevim, O. Olgun, S. A. Gökmen. Resources: A. Sarmiento-García, B. Sevim, O. Olgun. Software: S. A. Gökmen. Supervision: A. Sarmiento-García, B. Sevim, O. Olgun. Validation: A. Sarmiento-García, B. Sevim, O. Olgun. Visualization: A. Sarmiento-García, B. Sevim, O. Olgun. Writing – original draft: A. Sarmiento-García. Writing – review and editing: A. Sarmiento-García, S. A. Gökmen, B. Sevim, O. Olgun.

Financial support

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors confirm that the ethical policies of the journal, as noted on the journal's author guidelines page. The European National Research Council's guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals were followed.