On January 4, 2019, the House of Representatives voted 418–12 to appoint the Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress as part of the rules package for the 116th Congress. Though few members (seven in total) spoke on its behalf during floor debate, the Select Committee’s creation reflected widespread bipartisan consensus that the Congress is broken. The House charged the Select Committee to “investigate, study, make findings, hold public hearings, and develop recommendations to modernize and improve the way Congress operates” (Congressional Record, 1st session, 2019, H220); these recommendations were published in a 295-page report in October 2020.

The Select Committee’s appointment and broad purview mirror prior reform efforts, including the 1945–46, 1965–66, and 1992–93 Joint Committees on the Organization of Congress, as well as the 1969 Special Subcommittee on Legislative Reorganization of the Committee on Rules.Footnote 1 These reform efforts brought together experienced institutionalists across Congress to hear and learn from experts and their colleagues on the status and future of legislative procedure. Scholars widely agree that the timing and content of the resulting reforms reflected the interests of key stakeholders, including a large cohort of junior members (Schickler, McGee, and Sides Reference Schickler, McGhee and Sides2003); ideological and party factions (Rohde Reference Rohde1991; Rubin Reference Rubin2017); and member and leadership prerogatives (Cox and McCubbins Reference Cox and McCubbins1993; Jenkins and Stewart Reference Jenkins and Stewart2013; Schickler Reference Schickler2001).

This article examines the leadership, participation, and salience of the Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress among individual members, party factions, and external actors, including interest groups and the national media that cover Congress. It addresses these questions: What interests—group, ideological, or institutional—are represented by the Select Committee’s leadership? How do internal and external participants in the Select Committee’s work challenge—or reinforce— potential biases in interests? How salient is the Select Committee’s work among key stakeholders in the 116th Congress?

After analyzing the early stages of legislative reform in the 116th Congress (Baer Reference Baer2022), I find that the Select Committee’s membership is both a microcosm of key factions in both parties and a reservoir of members with significant institutional expertise. Bifurcated participation patterns among individual members result in an overrepresentation of junior members, party leaders, and outside experts, including members of the American Political Science Association’s Task Force on Congressional Reform. Notably, the Select Committee’s work and legislative procedure more broadly seem to have limited salience among the media, factions, and party leaders.

SELECT COMMITTEE LEADERSHIP

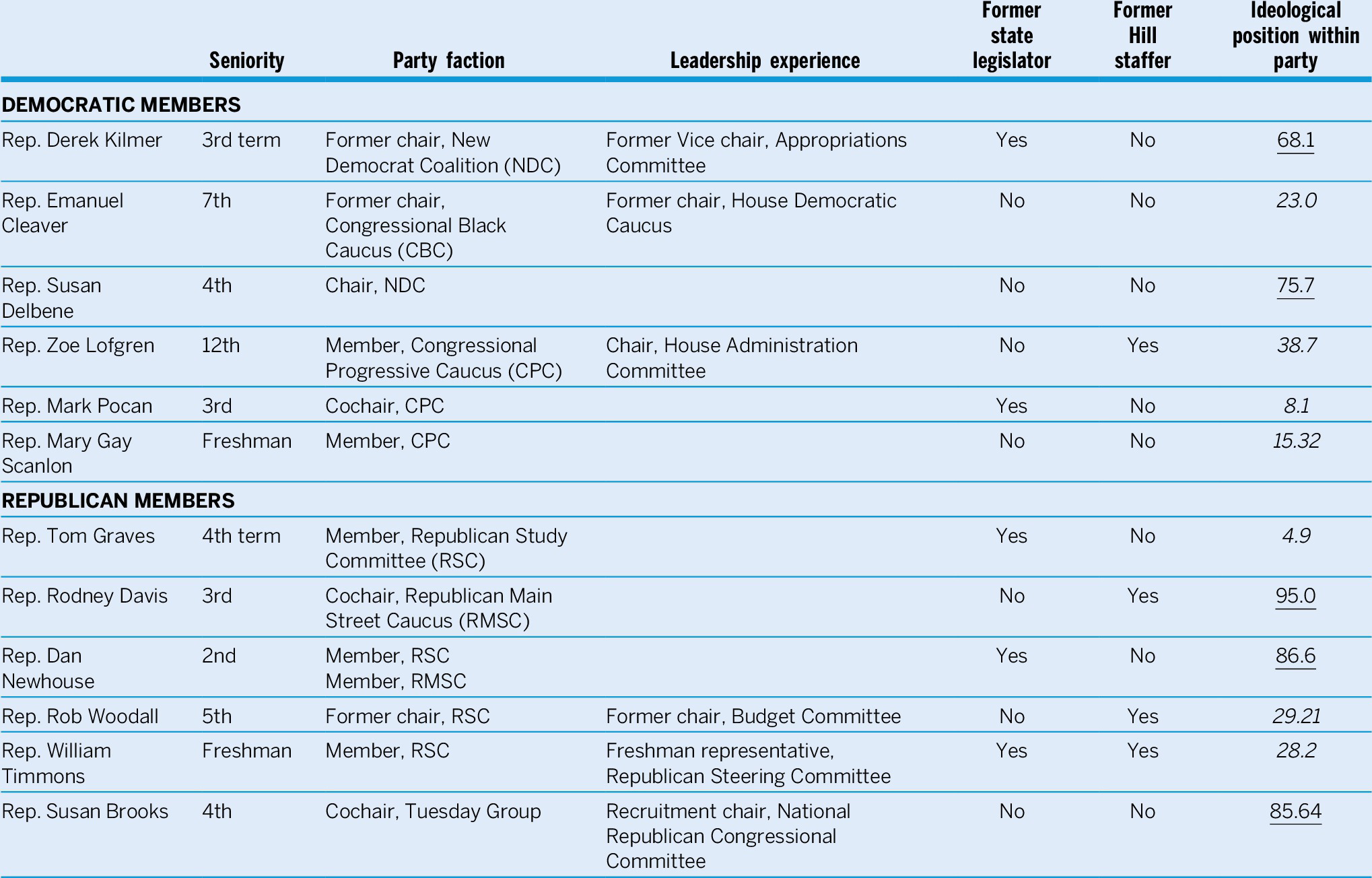

Party leaders appointed Democratic and Republican members to the Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress in the 116th Congress. As table 1 illustrates, strategically and symbolically important factions in both parties, including the Congressional Progressive Caucus, the New Democrat Coalition, the Republican Study Committee, and the Republican Main Street Caucus, are represented on the committee. The Select Committee’s paradoxical composition suggests that party leaders sought a balance between representatives of key factions and ideological groups within each party and members with institutional experience: in fact, seven of the Select Committee’s members currently or previously chaired six legislative factions in the House. Such significant representation is unlikely to be due to chance and suggests that party leaders sought both members with close ties to organized factions and those with institutional experience who might be better positioned to engage in coalition-building activities than their colleagues without such experience.

The Select Committee’s paradoxical composition suggests that party leaders sought balance between representatives of key factions and ideological groups within the party, as well as members with institutional experience.

Table 1 Membership of the Select Committee of the Modernization of Congress, 116th Congress

Note: Percentile rank is calculated using first dimension DW-NOMINATE scores for the 116th Congress. As defined by Harris and Nelson (Reference Harris and Nelson2008), members with italicized rankings (“extremity” position) represent their party’s ideological extreme (1st–39th percentile), whereas members with underlined rankings (“chamber moderate” position) are drawn from outside of the party’s mainstream (61st percentile and higher).

Source: Data in table 1 on member background, experience, and seniority are collected from the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress (2021).

On average, the Republican members of the committee are more junior and hold more extreme views relative to the rest of their party than the Democratic members. This ideological distribution suggests that Democratic members may be better positioned to advocate on behalf of the range of attitudes in their caucus than their Republican colleagues. Notably, neither party’s Select Committee representatives include so-called ideological middlemen, or those members drawn from the middle of their party’s respective ideological distribution (Harris and Nelson Reference Harris and Nelson2008). Instead, party leaders drew from the ideological extremes of their membership. Four Democratic members are from the (liberal) “extreme” of the party, and two are drawn from the (conservative) “chamber moderate” wing of the party. Likewise, three Republican members are drawn from the (conservative) “extreme” of the party, whereas three members come from the (liberal) “chamber moderate” wing of the party. In addition, both parties’ top representatives are outside their party’s mainstream: approximately 5% of the Republican Conference is more conservative than Vice Chairman Tom Graves (R-GA), and approximately two-thirds of the Democratic Caucus is more liberal than Chairman Derek Kilmer (D-WA).

Leaders from both parties appointed members with significant institutional experience. Half of the membership currently or previously held party or committee leadership positions, giving them potential insight into issues of campaign finance, budget and appropriations processes, party caucus prerogatives, and committee powers and processes. Forty-two percent of committee members, including the chair and vice chair, served in their home state’s legislature before being elected to Congress, which mirrors the full House membership according to the National Conference of State Legislatures (Ramsdell Reference Ramsdell2019). Notably, former congressional staffers are also overrepresented among Select Committee members (33% vs. 14% of all House members, according to Congressional Research Service estimates; Manning Reference Manning2020).

SELECT COMMITTEE PARTICIPATION

The Select Committee held 16 in-person hearings and 6 “virtual discussions” throughout 2019 and 2020 to solicit the views of interested individuals and of groups inside and outside Congress. Committee participation patterns among individual members reflect long-standing historical patterns, whereas those of invited, external participants reflect a shift from earlier reform efforts.

Individual Members’ Participation

The most significant—and public—opportunity for individual members to participate in the Select Committee’s work was at the Member Day Hearing on March 12, 2019. As shown in figures 1.1–1.4, the 35 participating members represent a cross-section of the House, although majority party members, junior members, and party leaders are overrepresented.Footnote 2

Figure 1.1 Member Day Hearing Participation, Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress, 116th Congress

Seniority

Figure 1.2 Member Day Hearing Participation, Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress, 116th Congress

State Legislative Experience

Figure 1.3 Member Day Hearing Participation, Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress, 116th Congress

Ideology

Figure 1.4 Member Day Hearing Participation, Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress, 116th Congress

Minority Party Status

Forty percent (or 14) of participating members are freshmen and sophomores (a group that comprises 33% of the full House). Members asked the Select Committee to consider reforms that would respond to the increased salience of workplace sexual harassment amidst the #MeToo movement and to the December 2018–January 2019 government shutdown. Rep. Lauren Underwood (D-IL), for example, sought to expand the Ethics Committee’s jurisdiction and mandate public disclosure of any committee reports. Rep. Mike Gallagher (R-WI) suggested merging appropriations and authorizations processes to end the cycle of “shutdowns, continuing resolutions, and gigantic omnibus bills.” Limiting or abolishing the motion to recommit also received attention from several freshmen from marginal districts, including Reps. Chrissy Houlahan (D-PA) and Cynthia Axne (D-IA). Another freshman member, Rep. Katie Porter (D-CA), used her testimony to highlight class biases, which make it difficult for members from historically underrepresented groups to serve (Porter is a single mother).

In total, 23% of participating members held party or committee leadership positions in the 116th Congress (overall, 17% of House members held such positions), including top party and committee leaders who used their testimony to praise their own past work. Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) emphasized the creation of a Diversity and Inclusion Office and a “family-friendly” legislative schedule. Rep. Steve Womack (R-AR), Budget Committee Ranking Member, used his testimony to tout his efforts as cochair of the Joint Select Committee on Budget and Appropriations Process Reform in the 115th Congress. Both Democratic Majority Leader Steny Hoyer (D-MD) and Republican Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) emphasized their past mutual support for “hack-a-thons” to bring existing and new legislative data to public digital platforms.

Yet, both parties’ leaders made few specific calls for reform; McCarthy touted his idea to incorporate blockchain and artificial intelligence in legislative work, and Hoyer suggested the reinstatement of legislative earmarks. Leader testimony may be indicative of a desire to give the Select Committee broad latitude in identifying potential reforms, but it may also signal leaders’ narrow parameters for potential reform. Such limitations would be consistent with their contemporaneous efforts to stymie controversial reforms, such as leadership term limits (Caygle and Bresnahan Reference Caygle and Bresnahan2019).

Participating members have a more diverse pre-congressional background than is typical. Only 23% of testifying members previously served in their home state legislature—a far lower percentage than among Select Committee members and House members overall. These dynamics reflect changing congressional pipelines, though it is a shift from historical reform efforts that were largely driven by institutionalists with significant legislative experience. Members drew extensively on these nonpolitical perspectives in justifying their proposals. Rep. David Trone (D-MD), for example, linked his background as an entrepreneur to his advocacy for paid internships and new technological investments.

The overrepresentation not only of party and committee leaders but also of junior members at the Member Day Hearing reflects the bifurcated stakes of procedural and organizational reform. These participation patterns suggest a continuation of a paradox observed in earlier reform efforts in which junior members and party leaders share the highest stakes in the adoption of procedural changes (Cox and McCubbins Reference Cox and McCubbins1993; Rohde Reference Rohde1991; Schickler, McGee, and Sides Reference Schickler, McGhee and Sides2003).

External Participants’ Participation

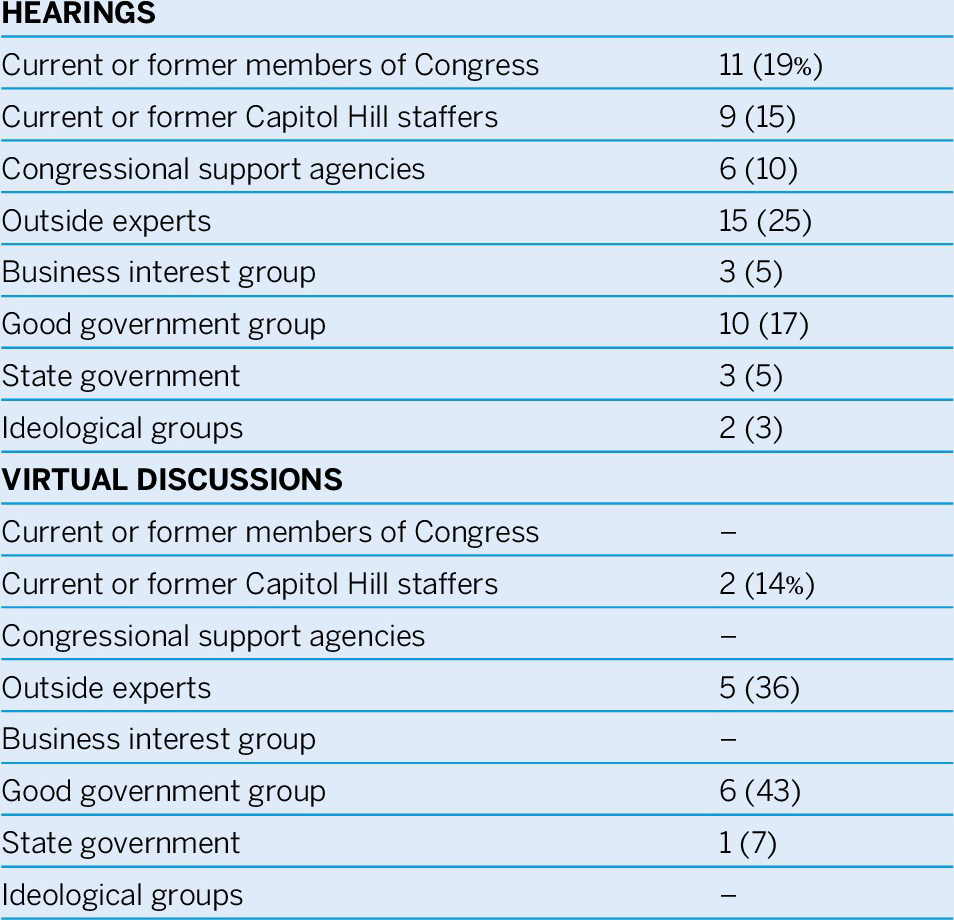

The Select Committee invited 73 witnesses to give oral testimony at 15 in-person hearings and 6 “virtual discussions” (as shown in table 2). The single largest group (25%) of hearing witnesses are outside experts and researchers, a majority (73%) of whom are political scientists, including many members of the American Political Science Association’s (APSA) Task Force on Congressional Reform. APSA Task Force members also comprised a large plurality of virtual discussion participants. Congressional support agencies, including the Congressional Research Service, likewise provided nonpartisan expertise on congressional processes. Incumbent members and current and former congressional staffers together comprise approximately one-third of invited committee witnesses. The Select Committee also solicited the views of good government groups, which comprised 17% of hearing witnesses and 43% of virtual discussion participants.

Table 2 Invited Participation in the Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress, 116th Congress

Source: Compiled from hearing reports, prepared testimony, and video transcripts posted to the website of the Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress.

Two potential stakeholders in procedural reform—the media and ideological interest groups—are notably absent from the Select Committee’s invited participants. No print, broadcast, cable, or other media representatives testified, and only one conservative-leaning (R Street Institute) and one liberal-leaning group (Demand Progress) were invited to testify.

The makeup of invited—and not invited—witnesses suggests that the Select Committee’s leadership prioritized participants who could provide high-quality, often nonpartisan legislative information. The committee’s emphasis on hearing from political scientists—the single largest invited group, fully one-quarter of all hearing and virtual discussion participants—is especially notable. The composition of external participants also suggests a deliberate effort by the Select Committee’s leadership to limit hearing from sources with an ideological or partisan bias—a direct check on the close ties that members themselves hold to organized factions in the House.

The composition of external participants also suggests a deliberate effort by the Select Committee’s leadership to limit hearing from sources with an ideological or partisan bias—a direct check on the close ties that members themselves hold to organized factions in the House.

The list of invited witnesses also suggests that the Select Committee may view reform stakeholders differently than did earlier reform committees. Indeed, the absence of the media, which participated in discussions about reforms to increase legislative transparency and accountability, the topic of two Select Committee hearings in 2019, is striking. Even among good government groups, the Select Committee solicited the views of a new generation of such groups. PopVox, for example, which counts two former congressional staffers among its leadership, leverages new technologies to connect individual citizens with the day-to-day work of lawmakers. By contrast, historically, groups like Common Cause pushed for procedural reform through conventional political activities, including campaign donations, endorsements, and advertising, which leveraged members’ electoral interests and public outrage to build broad public coalitions (Zelizer Reference Zelizer2004, Reference Zelizer2020; Wright Reference Wright2000).

SALIENCE OF SELECT COMMITTEE ACTIVITIES

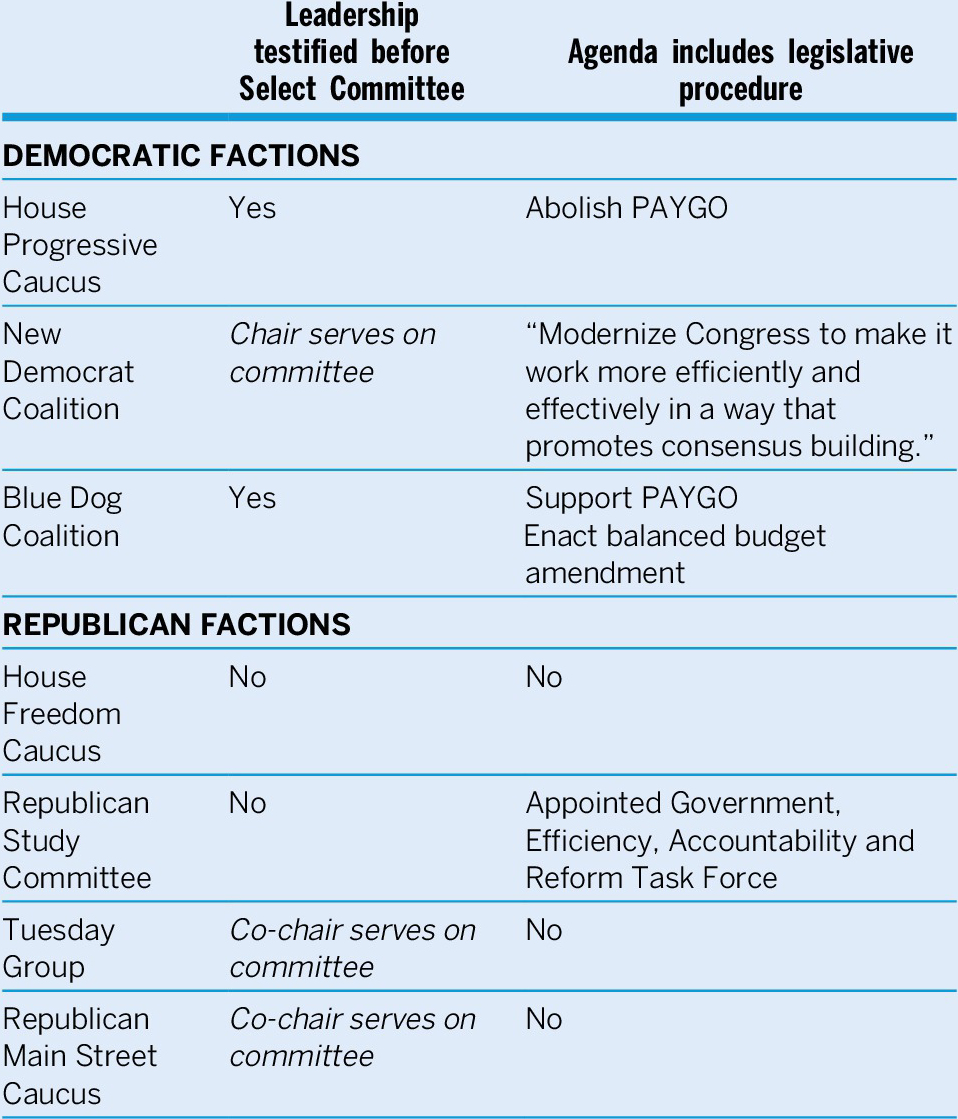

Analyses of the agendas and activities of legislative party factions, the media, and party leaders reveal limited salience of the Select Committee’s work, and notable asymmetries between Democratic and Republican Party factions and procedural and policy priorities for key stakeholders.

Party Factions

Table 3 presents data on reform activities of the largest and most prominent factions in each party’s caucus/conference. Overall, Democratic factions prioritized legislative procedure more than Republicans. The New Democrat Coalition (NDC)—the largest faction in the House Democratic Caucus (104 members in the 116th Congress)—included reform as part of its “20 for 2020” agenda and led the effort to create the Select Committee. Rules Committee chairman Jim McGovern (D-MA) notably singled out the group in floor remarks: “I especially thank Representatives [Derek] Kilmer [D-WA] … as well as the New Democrat Coalition, for this idea” (Congressional Record, 1st sess., H221, italics added). The NDC’s agenda did not identify specific reform proposals, although it may have viewed this an unnecessary given that its former and current chairs serve on the Select Committee.Footnote 3

Table 3 Salience of Legislative Procedure and Reform among Key Party Factions, 116th Congress

Note: Data on caucus agendas identified from press releases and reports issued by each group, as well as news coverage of their activities.

By contrast, the Congressional Progressive Caucus (Axelrod Reference Axelrod2019) and the Blue Dog Coalition (Jagoda Reference Jagoda2019) included specific procedural reforms in their caucus agendas. PAYGO, or the pay-as-you-go provision, is viewed as an impediment to the adoption of Medicare for All, which is supported by liberals and opposed by conservative Democrats (Golshan Reference Golshan2019). Democrats are more unified in their support —albeit for different reasons—for limiting or abolishing the “motion to recommit,” which provides a mechanism for the minority party to force floor votes on contentious policy issues and directly amend legislation: liberals view the procedure as a threat to their policy goals, whereas conservatives view it as a tool for Republicans to attack vulnerable members from marginal districts (Washington Reference Washington2020).

Among Republican factions, only the Republican Study Committee included reform in its agenda for the 116th Congress: then-chairman Mike Johnson (R-LA) appointed a Government Efficiency, Accountability and Reform Task Force headed by Rep. Greg Gianforte (R-MT). However, the Task Force’s (2020) final recommendations exclusively targeted the federal civil service and limitations to executive agency autonomy.

The Select Committee’s October 2020 report received scant public attention from factions, and none endorsed its findings. Although it is not clear whether the Select Committee specifically sought such support, its leaders did visit the largest faction in the opposition party: Chairman Kilmer (D-WA) met with the Republican Study Committee, and Vice Chairman Graves (R-GA) met with the New Democrat Coalition (Monitor’s View Reference View2020). Such outreach suggests that leaders sought some interparty compromise on behalf of procedural reform in conjunction with the Select Committee’s own bipartisan efforts.

Coverage in the Media

As figures 2.1–2.3 illustrate, the media provided limited coverage of both rule and procedural reform, and of Select Committee activities more broadly, throughout the 116th Congress. Overall, 47 news stories and editorials over the two-year period cited the Select Committee’s work.Footnote 4 This news coverage paid periodic, but limited, attention to the motion to recommit and PAYGO, especially at the beginning of the first session when Democrats and Republicans alike drove attention to these specific provisions.

Figure 2.1 Media Coverage of Select Committee Activities and Procedural Reform, 116th Congress, “Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress”

Figure 2.2 Media Coverage of Select Committee Activities and Procedural Reform, 116th Congress, “motion to recommit”

Figure 2.3 Media Coverage of Select Committee Activities and Procedural Reform, 116th Congress, “PAYGO”

This limited attention, of course, may reflect the financial realities of the news business in which public interest drives media stories. Thus, I also analyzed press releases issued by two long-standing national news media trade associations that regularly lobby and testify before Congress, including during the 116th Congress: the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB) and the News Media Alliance (NMA). The NAB (founded in 1922) is the “premier trade association for broadcasters,” and the NMA (founded in 1992) represents “all news media content creators.” In the 116th Congress, the NAB and the NMA, respectively, issued 57 and 25 press releases on congressional activities, including hearings, legislation, (co)sponsorship, leadership appointments, and committee reports. Among the policy issues addressed were media labor rights, radio taxes, a proposed memorial to “fallen journalists,” antitrust concerns, and big tech platforms, as well as little known regulatory issues like retransmission consent. The NAB and the NMA press releases neither addressed the Select Committee nor any issue of media access to legislative activities. Limited lobbying activity may suggest a satisfaction with current access to Capitol Hill, but it is inconsistent with the media’s historical participation in procedural reform efforts, as well as their current participation in legislative debates on issues they deem of interest to the industry.

Involvement of Party Leaders

Figure 3.1 presents data on Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s (D-CA) references in three key public forums to the activities of the two select committees organized for the 116th Congress.Footnote 5 As the data illustrate, Speaker Pelosi clearly made some effort to publicize the creation of the Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress, including the early appointments of committee members and leaders.Footnote 6 The much greater attention to the work of the Select Committee on the Climate Crisis reflects the importance of climate change as a policy issue for Democrats, but it also provides some context for the scope of public support that the Speaker could have offered Chairman Kilmer (D-WA) and other Democrats working on procedural reform. Especially notable is the difference in treatment of the two Select Committees’ final work products. On September 10, 2020, the Speaker noted during her weekly press conference that the Select Committee on the Climate Crisis, “under the leadership of Kathy Castor [D-FL], they have put forth their report, which has received so many accolades from scientific judges of such reports that it is objective, strong and the formula that we need to go forward.” By contrast, the October 2020 report issued by the Select Committee on the Modernization of the Congress received no public attention from the Speaker’s office.

Figure 3.1 Public References to Select Committee Activities by Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA), 116th Congress

Unfortunately, it is not possible to observe Speaker Pelosi’s potential behind-the-scenes efforts to elevate procedural reform among her Democratic colleagues. However, there is limited evidence to suggest that the Speaker sought to elevate issues of legislative procedure—or the work of the Select Committee—for audiences outside Congress.

CONCLUSIONS

What does the creation of the Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress in the 116th Congress suggest about contemporary legislative reform efforts?

Notably, it is a striking example of bipartisanship and proud institutionalism rarely observed in today’s partisan era. Select Committee members are drawn from outside the mainstream of their respective caucuses/conferences and hold close ties to extreme factions in their parties. Yet committee leaders overwhelmingly sought insights from nonpartisan experts, including the APSA’s Task Force on Congressional Reform, and succeeded in producing a unanimous set of reform recommendations—no small task given that the Joint Select Committee on Budget and Appropriations Process Reform failed to do so in the 115th Congress (Butler and Higashi Reference Butler and Higashi2018).

Most notably, the Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress is a striking example of bipartisanship and proud institutionalism rarely observed in today’s partisan era.

More broadly, legislative reform efforts in the 116th Congress both reflect and challenge long-standing historical participation and coalition-building patterns. The close ties of Select Committee members with major factions in both parties, as well as the bifurcated participation of junior members and leaders, is consistent with prior successful reform efforts and the broad, overlapping coalitions emphasized by Schickler (Reference Schickler2001). However, observed asymmetries in participation and salience between Republicans and Democrats on behalf of congressional reform and the lack of media participation represent a shift from past efforts. In the 1960s, minority party Republicans carefully developed their own set of proposals to create a “Modern Congress,” including committee jurisdiction reforms, guaranteed minority staffing, and the introduction of electric voting and television coverage (McInnis Reference McInnis1966). Moreover, in 1970, the Democratic Study Group successfully mobilized newspaper editorial boards across the country to decry the “problem of secrecy” on behalf of House reforms strengthening recorded teller and committee votes and opening committee hearings. This effort indirectly pressured their colleagues to support transparency reforms (Baer Reference Baer2017). Today, such agenda-setting and coalition-building efforts are notably absent among organized factions and the minority (Republican) party.

Finally, participation in the Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress reveals a surprising paradox about congressional reform. In absolute terms, few members participated in Select Committee’s activities, and party factions, the media, and party leaders paid scant attention to its efforts. Theories of reform often assume salience, especially if there is evidence that members recognize existing legislative procedures as an impediment to their policy and power goals (e.g., Cox and McCubbins Reference Cox and McCubbins1993; Schickler, McGee, and Sides Reference Schickler, McGhee and Sides2003). There is clear evidence that members today recognize such linkages (e.g., PAYGO and Medicare-for-All, the December 2018 campaign on behalf of Democratic leadership term limits): Kingdon (Reference Kingdon1984, 207) terms this “problem recognition.” Yet, there is minimal evidence that members, factions, leaders, or observers of Congress view rule and procedural reform as a solution to that “problem” in the 116th Congress. The absence of such salience, despite the creation of an internal mechanism to study congressional organization, raises important normative and theoretical questions about how to promote member interest and engagement on procedural reform in the 117th Congress and beyond.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author declares that there are no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.