The global upsurge in populist nationalism has spurred recent interest in how meritocracy “concentrates advantage and then frames disadvantage in terms of individual defects of skill and effort, of a failure to measure up.”Footnote 1 Meritocracy's legitimacy is ultimately premised on equality of educational opportunity. In sociology, the insight that claims for such equality are undermined by the operation of social or cultural capital informed reproduction theory in the 1970s, which was partly inspired by radical Maoism.Footnote 2 But post-Mao China's own repudiation of egalitarianism marked the triumphant return of an elitist emphasis on education's selective function. The application of meritocratic principles rapidly extended to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) itself, with new procedures for cadre selection and evaluation.

Throughout subsequent decades, other mechanisms for sorting and controlling China's population have persisted, not least the hukou 户口 system of household registration. Fragmenting entitlements helps to buttress control by creating rival vested interests, united only in their dependence on the party-state.Footnote 3 Since the 1990s, accelerating urbanization and marketization have made arbitrary distinctions between urban and rural hukou holders increasingly indefensible, but promoting uniformity of access to public goods for all citizens remains off the agenda. At issue is the fear that equalizing entitlements would trigger an uncontrollable influx of migrants into China's largest cities as those with rural residency seek access to superior urban public services, especially education.

Meritocracy has thus become crucial to lending a sheen of equity to what remains a profoundly unequal distribution of entitlements. Invoking Confucius, the philosophical case for a China model consisting of meritocracy at the top, experimentation in the middle and democracy at the bottom has been elaborated.Footnote 4 The choice, we are told, “comes down to Western-style economic hierarchy with a commitment to social equality versus East Asian-style social inequality with a commitment to economic equality.”Footnote 5 Nanjing's Imperial Examinations Museum today hails the old civil service examinations as China's “fifth great invention,” their “openness” providing a basis for “fair” competition and selection by merit.Footnote 6

The claim that a “just hierarchy” implies commitment to economic equality sits awkwardly with the spiralling inequality that distinguishes China's era of rapid growth from those of its far more egalitarian East Asian neighbours.Footnote 7 Terry Woronov shows how assessment practices reproduce and legitimate social class hierarchy, with high school entrance examinations (zhongkao 中考) irrevocably branding vocationally streamed students as failures. This reflects a pervasive economism that reduces individuals to their human capital, sorting them according to their presumed productive capacity and “quality.” Official obsession with measuring the attributes of the entire population amounts, Woronov argues, to a “fetishization” of “numeric capital.”Footnote 8

Today, the calibration of numeric capital extends to a radical intensification of efforts to monitor, sort and regiment vast swathes of the Chinese population. And groups typically seen as threatening social and political stability – notably, migrant workers and restive minorities – find themselves first in line for this treatment.

This paper analyses the deployment of ostensibly meritocratic procedures for allocating urban school places to migrants, locating this in the context of the wider state project of control through assessment. Our analysis builds on recent research into points systems, the application of which was expanded significantly following the 2014 announcement of a planned national residents’ registration system that decoupled hukou from access to local public services. In 2016, the State Council called on all but the largest cities to ease restrictions and allow college graduates, skilled workers and overseas returnees to obtain urban hukou.Footnote 9 However, Yiming Dong and Charlotte Goodburn suggest that points systems have in fact purposefully reinforced segregation within the urban population.Footnote 10 They conclude that “all levels of the Chinese state give a greater priority to population control than to social equality and cohesion.”Footnote 11 This is consistent with recent analysis of the politics of education in China.Footnote 12 Here, we look beyond the megacities of Shanghai, Beijing and Shenzhen 深圳, the foci of those studies, and examine district-level data from a range of cities including mid-level conurbations that are supposedly licensed to be more accommodating of migrants. And by locating points systems in the context of a larger bureaucratic-ideological project of intensified monitoring and surveillance, we argue that procedures for ranking and sorting migrants should be understood as components of a ramifying assessment state.

We begin by briefly explaining how these new points systems fit into broader arrangements for managing migrant populations, analysing the political background to their introduction. We then discuss the ideological underpinnings of the broader project for ranking and assessing China's citizenry, and its expansion under Xi Jinping 习近平. There follows a more detailed analysis of the introduction and implementation of points systems for the allocation of school places at district level, extending to a brief examination of the language used to justify them, and their reception by local actors. Finally, our conclusions focus not only on points systems’ implications for migrants’ educational access but also on their place in the regime's evolving strategy for managing state–citizen relations.

Urbanization, Household Registration Reform and Points Systems for Migrants

There are currently three overlapping routes for migrant children to enter urban public schools during the compulsory education phase.Footnote 13 A “preferential policy for talent recruitment” (youhui zhengce moshi 优惠政策模式) targets highly skilled personnel.Footnote 14 A second, often parallel, route is “admission on the basis of documents” (cailiao zhunru moshi 材料准入模式) (ID card, residence permit, etc.).Footnote 15 A third mode, which is newer but becoming increasingly widespread, incorporates elements of both approaches into a points system (jifenzhi 积分制) that comprehensively scores submitted documents according to a localized metric.Footnote 16

Points systems themselves come in three overlapping variants. In the first, applicants are scored to determine their eligibility for a full urban hukou. In the second, migrants apply for residence permits, a practice first adopted by Shanghai in 2013 (extended in 2018), allowing children of successful applicants to participate in local public examinations. The last variant – our primary focus here – specifically determines access to public schooling. In some localities, especially in major megacities, the scoring of applications for residence permits or hukou transfer itself forms the basis for allocating school places.

Points systems for migration management, as practised by numerous countries, typically seek benefits for the receiving jurisdiction – maximizing human capital while minimizing public expenditure.Footnote 17 While inspired by these foreign precedents, the Chinese case uniquely applies this approach to the ranking and sorting not of foreign immigrants but of fellow nationals.Footnote 18

In 2014, a State Council “Opinion” declared that the household registration system would be unified nationally, and the residence permit (RP) system (juzhuzheng 居住证) applied fully. Basic public goods, it was announced, would henceforth be extended to all permanent urban residents.Footnote 19

The RP system was first introduced in the early 2000s, but the “New national urbanization plan for 2014–2020” (NUP hereafter) calls for the rigorous extension of its application to migrants. The NUP directs large conurbations to exercise strict control over inward migration, while encouraging smaller cities to relax restrictions in line with local conditions.Footnote 20

While this shift from hukou to RPs is presented as a move towards promoting migrants’ welfare, research has suggested that it involves continued official prioritization of economic growth, fiscal retrenchment and social control.Footnote 21 Migrants tend to be viewed instrumentally as human capital – or, in Jieh-Min Wu's terms, as “privileged non-citizens” rather than bona fide “denizens.”Footnote 22 Following the banning of “guest student fees” (jiedufei 借读费) in the early 2000s, receiving rather than sending localities are required to fund migrants’ schooling.Footnote 23 However, with migrants widely seen as “dangerous enemies who take educational resources … from urbanites,”Footnote 24 local leaders are incentivized to curtail migrant children's access while extracting maximum revenue from their parents.Footnote 25

Regulations stipulating teacher–student ratios further hamper the accommodation of migrant children in urban schools, since teacher quotas are generally based on the number of students with local hukou.Footnote 26 A city accommodating numerous migrants in its public schools may thus need to recruit many off-quota temporary teachers. Similar factors explain a systematic under-allocation of funding for school building.Footnote 27

Receiving localities therefore continue to restrict migrants’ access to schooling, but do so using procedures that grant a veneer of meritocratic legitimacy. Previous research suggests that the widening use of points systems since 2014 has provided cover for cities seeking to reverse earlier trends towards expanded access for migrants.Footnote 28 But the points-based approach must also be understood in relation to a broader, evolving state apparatus for evaluation, monitoring and surveillance.

“Quality” Discourse, Migrants and the Assessment State

Factors besides financial calculation shape views about migrants and their likely impact on urban life. The idea of suzhi 素质 looms large. Literally translated as “essentialized quality,” suzhi has been described as “an amorphous concept that refers to the innate and nurtured physical, intellectual and ideological characteristics of a person.”Footnote 29 Originally used in the 1980s to emphasize the need to discipline peasants and improve “population quality,”Footnote 30 suzhi has since been applied in many fields and assumes a broad range of meanings.

In 1985, the “Decision” to universalize nine years of compulsory education touted raising the suzhi of the nation and production of talented personnel (rencai 人才) as key aims.Footnote 31 Quality-oriented or suzhi education constituted the main theme of the Third National Education Work Conference in 1999.Footnote 32 Suzhi-oriented pedagogical approaches involve promotion of non-cognitive skills, more extra-curricular offerings, and the deployment of better-qualified teachers and more resources per student.Footnote 33 While wealthier urban areas serve as models, various “backward” groups (peasants, minorities) are seen as presenting challenges for the achievement of suzhi-related goals.Footnote 34

Migrants are frequently dismissed as being of low quality, uncivilized and undisciplined.Footnote 35 In 1998, the State Education Commission stressed that “enrolling migrant children in schools is related to the improvement of the suzhi of the whole nation.”Footnote 36 Assuming migrants’ inevitable inferiority, central government policy aspires merely to narrow the suzhi gap between urban-resident and migrant children. Migrant children in public schools have proven themselves capable of outperforming their urban counterparts,Footnote 37 but appropriate support is typically lacking.Footnote 38

More generally, suzhi discourse helps legitimate inequitable allocations of educational resources by emphasizing individuals’ responsibilities for their own welfare in a competitive world.Footnote 39 Ann Anagnost describes suzhi rhetoric as a “quintessential” manifestation of “rational choice” evangelism.Footnote 40 It preaches individual responsibility in order to deflect demands for more equitable welfare provision.Footnote 41 Points systems further institutionalize this meritocratic ideology, making assessment of suzhi, or individual/familial quality, the key determinant of a child's access to urban public schooling.

Under Xi Jinping, meritocracy has increasingly been promoted as a legitimating master narrative, distinguishing the China model from Western liberal democracy. Meanwhile, meritocratic rhetoric has been accompanied by intensified efforts to monitor, assess and rank the population.

The most ambitious of these efforts is social credit. A 2014 framework portrays this as “an ambitious, information technology-driven initiative through which the state seeks to create a central repository of data on … persons that can be used to monitor, assess and change their actions through incentives of punishment and reward.”Footnote 42 Pilot schemes penalize littering, jaywalking and cheating in exams, or reward care for elderly parents. Penalties for undesirable behaviour include being prohibited from booking airline tickets or enrolling children in private schools.Footnote 43 By 2019, the city of Rongcheng 荣成 in Shandong province had built a vast database that combined the personal financial records and government files of its residents, and graded them from AAA, AA, A to B, C and D.Footnote 44 The ultimate scope and impact of the social credit scheme remain unclear, but in conception it is a points system writ large, envisaging governance by assessment and citizenship stratified by merit.

The CCP itself has experimented with points systems for scoring members’ political and moral performance. One city in Jiangsu introduced a points system modelled on the Zhongshan 中山 template (see below) for assessing Party members;Footnote 45 the CCP branch at Kunming Medical University adopted a similar model.Footnote 46 Digital technology is increasingly deployed for this purpose. In one Zhejiang county, members are issued with a Party member pioneer card (dang-yuan xianfeng ka 党员先锋卡), which is linked to the online Red Cloud Platform for Party Construction (dang jian hong yun pingtai 党建红云平台). They then accumulate points under various categories: basic scores are earned through participation in meetings, training sessions, etc.; contribution scores are earned through community or volunteer service; and post scores derive from performing particular Party roles. A Party Member Pioneer Index tabulates individuals’ scores which, in turn, contribute to the score of their branch, which is then recorded on a Party Organization Advanced Index.Footnote 47

Technology is central to many of the new tools for assessment and monitoring and relates also to the nature of the activities scored – Party members, for example, can earn points for social media posts supportive of government policy. Technology is used further in monitoring and surveillance, from expansion of video surveillance across rural areas (the “Sharp eyes engineering project”Footnote 48) to the compulsory mass gathering of biometric data. The latter was piloted first in Tibet (from 2013) and then Xinjiang (from 2016), where DNA was collected from almost all male inhabitants, enabling a further extension of government control in these already tightly monitored regions.Footnote 49 From 2017, this vast exercise in harvesting genomic data was extended to the rest of the country. China's successful efforts to suppress COVID-19 in 2020 lent further legitimacy to the untrammelled collection of data on citizens and to the related use of technology to track movement and monitor behaviour.Footnote 50

Points systems for allocating school places should therefore be seen as cogs in an increasingly elaborate machine of governance by assessment which is dependent on the harvesting of personal data. By virtue of the importance attached to schooling by most parents, these systems constitute a powerful means of eliciting data from communities wary of engagement with the authorities. But submission to such procedures renders migrants complicit in the bureaucratization and legitimation of the very social hierarchy that confines them to its lowest rungs. In what follows, we examine more closely how this works at the local level, showing how the fine-tuning of points metrics underpins an increasingly sophisticated strategy for stratifying and controlling the populace.

Analysing Points-based Systems – Sources and Methods

To investigate the origins, design and implementation of points-based systems, fieldwork was conducted over two three-week periods in August 2018 and September 2019 in Shanghai and Zhejiang province. Relevant documents from Shanghai Fengxian 奉贤区, Jiaxing Nanhu 嘉兴市南湖区, Jiaxing Xiuzhou 嘉兴市秀洲区 and Ningbo 宁波 (see Appendix) were collected from local new residents’ affairs bureaus (xinjumin shiwuju 新居民事务局) or from public schools. Documents from other regions were downloaded from local government homepages (see Appendix).

This study is based primarily on documentary analysis and interviews. We analyse documents relating to ten districts across eight sample cities. Five are in the Pearl River Delta (PRD) and five in the Yangtze River Delta (YRD), both of which are major destinations for migrants and host megacities (Shanghai and Guangzhou) and mid-level cities such as Zhongshan and Jiaxing for which the 2014 NUP mandates different migrant management strategies. The YRD was selected as the main fieldwork site owing to the relative ease of accessing documents and informants there (one author is from Jiaxing). District-level documents from three cities were selected to examine within-city differences in the implementation of points systems. Semi-structured interviews were also conducted with four staff members of local new residents’ affairs bureaus and five public school teachers, with the purpose of supplementing and clarifying information gleaned from official documents, especially regarding the thinking behind the design of local systems and the attitudes of lower-level stakeholders.

Application Process and Scoring Criteria: The Zhongshan Template (2009)

Shanghai was the first city to experiment with points systems for vetting hukou applications (from 2004); it was only from 2009/2010 that such systems were applied more widely. In 2009, the Guangdong city of Zhongshan became “the first to introduce the points system as an integrated system that would allow migrants to apply for hukou, children's enrollment in public education as well as public housing.”Footnote 51 From 2010, Zhongshan's model was promoted throughout Guangdong by the provincial authorities.Footnote 52 Guangdong's approach then influenced the top-level design of policy on hukou and RP reform following the promotion of key local cadres to central leadership positions.Footnote 53

In 2018, Zhongshan rescinded the points-based approach for hukou transfer,Footnote 54 but retained it for the allocation of school places.Footnote 55 In theory a “liberalization” of hukou transfer by making it dependent on length of residency and tax and social insurance payments,Footnote 56 the Zhongshan model in fact reinforces the segregation between hukou and RP holders. Despite central government exhortations to make compulsory education available to all RP holders, Guangdong province has allowed cities to extend this right “in a graded manner.”Footnote 57 Effectively, it takes several years for migrants to successfully navigate the points system that rations entitlements such as school places before they can apply for hukou transfer.

All applications are subject to simultaneous qualification and quota controls, and the application process itself is a complex obstacle course. At the first hurdle, parents must demonstrate their “qualification to apply” (shenqing zige 申请资格), which involves possession of Guangdong RPs and at least a year's local work experience. Acquiring the necessary documentation entails formally registering their employment and paying social insurance. Following clearance from the migrants’ management office (liudong renkou guanli bangongshi 流动人口管理办公室), they can seek certification of their eligibility to apply to local public schools.Footnote 58 Parents of children born within the population planning regulations and who meet a minimum threshold of 30 points can file formal applications, which requires submitting various documents for scoring and ranking.Footnote 59 A lower ranking means assignment to a less prestigious or more remote school, while failure to meet a quota-determined cut-off score results in no allocation.

For applicants to urban public schools, such failure is final as only children in the grade-one or grade-seven age cohorts (the start of primary or junior secondary) can apply. Families must then either enrol in a school in their rural home district or in a private, fee-charging, migrant children's school. However, the latter avenue has narrowed as local governments are increasingly bringing such schools within the remit of the new points systems, subsidizing and regulating selected schools while shutting down the rest.Footnote 60

The Zhongshan system awards two categories of points: basic and additional.Footnote 61 Basic points include individual “quality” attributes (geren suzhi 个人素质), which encompass academic or professional qualifications, and attract high scores (Table 1). An undergraduate degree holder – with 80 points – can leapfrog a high school graduate with 65 points from different categories. Significant weight is also given to work experience: a formal contract and several years of urban employment betoken regular payment of taxes and an understanding of urban norms. Privileging RP holders and longer-term residents reflects an emphasis on upholding social stability,Footnote 62 while rewarding tax and social insurance payments helps, indirectly, to recover the costs of public schooling.

Under additional points, social contributions and financial capital receive significant weighting (Table 2). Contributions encompass capital invested, awards earned in national/regional competitions or through outstanding performance appraisals, or voluntary service (for example, assisting with major events staged by local governments). Possession of “urgently needed talents” (jixu rencai 急需人才) confers 50 points, and a national patent, 30 points. A national-level civic award (including the supplementary award for model citizenship) may on its own confer sufficient points to qualify. Other categories allow points effectively to be purchased, in the manner of a “golden passport” scheme. In Zhongshan, someone investing over 10 million yuan or paying tax exceeding 1 million yuan may thereby reach the qualification mark.

Table 2: Additional Points Categories under the Zhongshan System (2009)

Source:

ZMG 2009b.

Notes:

*There is no limit to the points that can be accumulated through the award of patents, investment or payment of tax.

The Zhongshan system, as originally operated (from 2009), thus prioritizes the recruitment of both human and financial capital to boost local development. Merit defined in these terms indicates the individual's capacity to contribute to economic growth. The use of elaborate metrics for sorting and ranking applicants for school places has subsequently spread to other cities. However, following promulgation of the 2014 NUP, the metrics deployed in the most prosperous and developed urban districts have increasingly diverged from those used elsewhere, as we examine below.

Calibrating Merit for Determining Educational Access: Local Differences

Local government guidelines and official documents at the time of writing indicate that points systems for hukou transfer and/or public school enrolment have been implemented in at least nine provinces (Guangdong, Fujian, Hainan, Liaoning, Zhejiang, Sichuan, Hubei, Jiangsu and Shandong) as well as the municipalities of Shanghai, Chongqing, Tianjin and Beijing. Widespread adoption of this approach reflects the coordinating role of central government,Footnote 63 but divergence in local practice shows that provincial, municipal and district authorities maintain some latitude in interpreting central guidelines according to local conditions.

Focusing on the megacities of Shenzhen, Shanghai and Beijing, Dong and Goodburn reveal considerable local variance within a common pattern of increasing segregation and stratification.Footnote 64 Shenzhen is most tolerant of new arrivals, but its points system, introduced in 2010 (following Zhongshan), nonetheless confines migrant children to the most poorly rated schools. In Shanghai, the 2013 extension of the points system to evaluate all RP holders resulted in the “sharp reversal” of a previously more accommodating approach.Footnote 65 Unequal treatment of migrants within the state system has also worsened. Beijing's approach is harsher still. The capital only introduced its own points system in 2017, and there “the distinction between local and migrant is important above all else.”Footnote 66 Migrants are almost entirely excluded from good state schools, and only the wealthiest can access any schools within their own district.

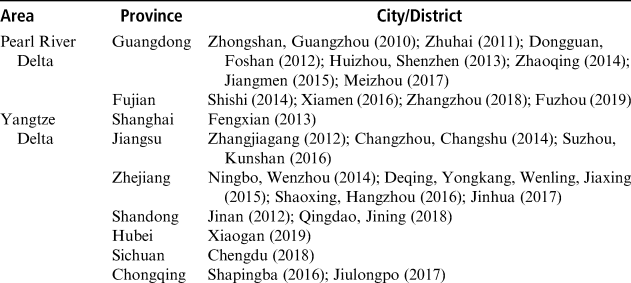

As Table 3 shows, in the five years after 2010, many PRD and YRD cities adopted points systems for allocating school places. As of 2019, ten cities in Guangdong and four in Fujian (together comprising the greater PRD) use such systems. In the YRD, points systems are deployed in six cities in Jiangsu, nine in Zhejiang, and in Shanghai's Fengxian district.Footnote 67 Other Shanghai districts have no separate points system for education and instead allocate school places on the basis of scores awarded through the RP application process.

Table 3: Introduction of Points Systems in Various Cities (year)

Source:

Local government documents accessed via Baidu, April 2019.

The especially rapid adoption of points systems in the PRD and YRD is explained in part by their utility in remedying under-registration of temporary migrants. The scale of rural-to-urban migration towards eastern and southern China is unsettling for a regime intent on control.Footnote 68 The RP system obliges migrants to register with the local police within a month of their arrival. However, since migrants often move on rapidly in search of new job opportunities, many never bother. By incentivizing registration through offering the prospect of eligibility for an urban hukou or state school place, points systems are seen as helping to alleviate such problems.

There is a significant shortage of public school places for migrant children in the PRD and YRD.Footnote 69 As of 2015, according to official figures, Guangdong (4.38 million), Jiangsu (1.5 million), Zhejiang (1.47 million), and Fujian (958,000) hosted the largest numbers of migrant children of compulsory schooling age, together accounting for 48.8 per cent of the nationwide total.Footnote 70 Estimates put the proportion of migrant children attending public schools in the PRD at 46.40 per cent overall, and at 23.18 per cent in Dongguan 东莞, 36.90 per cent in Zhongshan, 42.33 per cent in Guangzhou and 46.18 per cent in Shenzhen.Footnote 71 In the YRD, statistics indicate a higher proportion attending public schools, but substantial shortfalls of school places in many cities. The Zhejiang figures for 2018 show approximately 1.49 million migrant children enrolled in compulsory education, 74.4 per cent of them in public schools.Footnote 72 In Jiangsu, 99 per cent of migrant children were enrolled, 85 per cent in public schools. In 2015, 506,600 migrant children were receiving compulsory education in Shanghai, 80.42 per cent in public schools, the remainder in government-licensed private schools.Footnote 73 However, migrants’ overall access to schooling in Shanghai was by this point in steep decline owing to tightening controls on private schools for migrants. While the short supply of school places because of financial constraints is often cited as necessitating selectivity, such shortages can be exacerbated by authorities determined to restrict in-migration.Footnote 74

Official data typically underestimate migrant under-enrolment.Footnote 75 The figures exclude school drop-outs and children left behind in rural areas by parents who have failed points-based screenings. Unregistered children, or those whose parents are deemed ineligible to apply are also excluded. But some cities are significantly stricter than others. As of 2019, Zhongshan required migrants seeking permission to apply to demonstrate over three months of social insurance payments, while Jiaxing's Nanhu district required three years’ worth of payments. Figures for 2017 from the bureau of migrant affairs in another stricter city, Wenling 温岭 in Zhejiang, show that out of a cohort of 10,381 migrant children due to enter the first year of either primary or middle school, the parents of only 1,370 (13 per cent) actually submitted applications through the points system.Footnote 76

Seeking to understand variations between urban districts – the level at which points systems are precisely calibrated – we selected ten localities from the PRD and YRD and examined their systems as of 2019. These are: Shanghai Fengxian (FX), Suzhou (SZ), Jiaxing Nanhu (NH), Jiaxing Xiuzhou (XZ), Ningbo Beilun 宁波北仑 (BL), Zhongshan (ZS), Guangzhou Tianhe 广州天河 (TH), Guangzhou Huadu 广州花都 (HD), Dongguan (DG) and Zhuhai 珠海 (ZH).

Table 4 shows the application of particular scoring criteria or variables in these different locations. In every instance, possession of a residence permit, duration of residency and payment of social insurance are scored. Educational background, professional qualifications, awards, tax and investment, and property are also scored in most cases. Seven localities award points for employment, social contribution, and abiding by birth control regulations; six award points for patents; and six localities penalize records of crime or “bad behaviour.” Three cities entirely block applications from migrants with criminal records.

Table 4: Frequency of Variables in Ten Points-based Systems (as of 2019)

Sources:

Based on the authors’ calculations using information from official documents published by the relevant local authorities (see Appendix).

Notes:

“1” indicates that the city or district assigns points to this variable; “0” indicates that no

points are assigned.

The deployment of a particular variable tells us nothing about its significance. To assess this, we separately measured the points each variable can yield as a proportion of the maximum potential total (Y).Footnote 77 We postulate a qualified applicant who obtains the highest points for each variable (X), supposing no criminal record. We then calculate the percentage of available points (A) for each variable: A = X/Y. Since several cities set no maximum score for tax payments or investment, we multiply such variables by ten (years), the upper time limit adopted by most cities.

Table 5 presents the results of this calculation. Of the four main categories, individual quality and residence situation are the most heavily weighted; residence situation accounts on average for 56.9 per cent of available points, dominating scoring in Jiaxing Xiuzhou (85.7 per cent), Guangzhou Tianhe (83 per cent) and Shanghai Fengxian (77.5 per cent). The 2014 NUP and related directives encourage megacities such as Shanghai and Guangzhou to prioritize assimilation of long-term residents over attracting new migrants. Guangzhou Tianhe assigns 45.3 per cent of available points to just one variable: RP possession and residency years. In semi-rural Fengxian, Shanghai's only district using a points system for allocating school places, an applicant with a Shanghai RP and owning real estate who has continuously paid social insurance for over six months can gain about 50 per cent of the total available points, while the 20 per cent allocated to education and awards signifies some interest in attracting new talent. Zhongshan and Dongguan, prosperous PRD cities, also highly reward payment of social insurance and possession of real estate, while giving an especially heavy weighting to tax and investment. By contrast, Jiaxing Nanhu (47.9 per cent), Ningbo Beilun (59.1 per cent) and Guangzhou Huadu (70.6 per cent) accord greater weighting to migrants’ individual quality, as do Suzhou and Zhuhai.

Table 5: Points Available through Specific Variables (Criteria) as a Proportion of Maximum Total Points across Ten Systems (%)

Sources:

Calculations based on official data published by the relevant local authorities (see Appendix).

Notes:

Shanghai Fengxian combines 1.1 and 1.2 as one variable, assigning a maximum of 20 points (10%) to educational credentials and/or professional background. It also combines 2.1, 2.2 and 2.3 in a single variable, assigning a maximum of 50 points (25%) to an RP holder who pays for social insurance for more than 46 months or is continuously registered at the urban community neighbourhood committee for more than 3 years.

Comparing districts within the same city can further illuminate the factors influencing the weighting of different scoring categories (see Table 6). Jiaxing Nanhu favours children of highly skilled parents, especially those with science and technology expertise (signified by successful patent applications). However, Xiuzhou district ignores academic or professional performance. Although Nanhu is only slightly wealthier than Xiuzhou overall (with GDP of 60 billion yuan to Xiuzhou's 54 billion yuan), it is considerably more urbanized. In 2017, just over one-fifth of Nanhu's 509,000 hukou holders were registered as farmers (nongmin 农民), compared to just over half of Xiuzhou's 396,000 hukou holders. Nanhu's economy is more reliant on hi-tech industry and services, with manufacturing more important in Xiuzhou, which has 413 light industry enterprises to Nanhu's 232. Jiaxing's urban plan envisages Xiuzhou as a manufacturing hub, and the district has industrialized as entrepreneurs seek a cheaper alternative to nearby Shanghai.Footnote 78 These enterprises employ many low-skilled transient migrant workers, and Xiuzhou hosts far more migrants than Nanhu: 213,000 to 145,000. In Xiuzhou, statistics relating to enterprises over a certain (vaguely defined) size show that only 25,289 employees hold college degrees, while 126,000 have vocational qualifications of some sort. In Nanhu, the figures are 57,484 degree holders to 151,000 vocationally trained workers. Nanhu counts 13,627 people engaged in scientific research and technical services to Xiuzhou's 4,911.Footnote 79

Table 6: Detailed Requirements under Residence-situation Category in Jiaxing Xiuzhou, Jiaxing Nanhu and Guangzhou Tianhe

Sources:

Documents published by the relevant local authorities (see Appendix).

Notes:

“Yes” indicates that this variable is required for an applicant to qualify for points-based assessment; “No” indicates the absence of such a requirement. “*(minimum)” indicates the lowest threshold for assignment of points under a particular variable; “*(maximum)” indicates the level beyond which an applicant will cease to accrue extra points.

The Nanhu authorities, who accord relatively heavy weighting to “quality” indicators, use the points-based system to attract younger, more highly skilled workers to the district's technology sector. By contrast, Xiuzhou, whose factories rely on low-skilled migrant labour, does not emphasize high skills at all. Xiuzhou sets a relatively low requirement for duration of residency (scored on a sliding scale, whereas Nanhu demands possession of an RP) and for payment of income tax, and does not score on duration of employment at all. A key factor in Xiuzhou (absent in both Nanhu and Tianhe) is the size of the enterprise employing the applicant, indicating that the priority here is to help large manufacturers recruit and retain low-skilled workers.

Although local governments represent points-based systems as implementing the State Council's 2014 call to “unify residential registrations,”Footnote 80 hukou status still features as an explicit criterion in some points schedules. In Shanghai Fengxian, if one parent has a Shanghai hukou, 15 points are allotted (7.5 per cent of possible points; Table 4). Guangzhou Tianhe rewards agricultural hukou holders – but only with 3 per cent of available points – while giving exceptional weighting to length of urban residence, including children's experience of urban education. Tianhe's tiny apportionment of points to agricultural hukou holders looks like a token gesture towards compliance with hukou reform rhetoric. Here, as elsewhere and especially in upscale megacity districts, residency status (whether defined as possession of hukou, RP or documented length of residence) constitutes a key barrier to migrant integration.

A comparison of Guangzhou's Tianhe and Huadu districts provides a paradigmatic illustration of how points systems can reflect the objectives of the 2014 NUP.Footnote 81 Tianhe, where over 90 per cent of GDP comes from services, is a completely urbanized district in the centre of Guangzhou; at 2.9 million yuan, its GDP per capita is more than double that of Huadu, a peripheral, semi-rural district with a more mixed economy.Footnote 82 Tianhe's points system is extremely restrictive: in 2019, only 2,158 migrant children were enrolled in local schools in a district with a migrant population of almost one million. In Huadu, by contrast, 81.6 per cent of those applying through the points system qualified for a school place.Footnote 83 In Guangzhou, therefore, an inner-city district effectively denies entitlements to all but the most settled, wealthiest migrants, while a more outlying, less thoroughly urbanized district still seeks to attract new talent. But successful applicants are still stratified hierarchically, with the most “meritorious” allocated places in better, more convenient schools.

The reasons behind other divergences among districts in our sample remain more opaque. Zhejiang districts, as well as Zhongshan, award points for political criteria. Ningbo Beilun, for example, awards 14 per cent of total points for political participation, which can be CCP membership, Party branch committee work or service as an NPC deputy. In addition, Beilun and Zhongshan reward community training whereby migrants participate in lectures offered by the new residents’ office or the urban community neighbourhood committee on themes including points systems, birth control, waste sorting and recycling, traffic rules and “family education.”Footnote 84 Like many other criteria – both relating to residence situation and educational experience or qualifications – this incentivizes and rewards enhancement of individual “quality,” defined as assimilation to the civilized norms of urban Chinese modernity.

Justifying Hierarchy: Merit-based Equity versus Equality

How is this pattern of stratified access justified, and how are such justifications received by local stakeholders? In a study of Dongguan, Zhonghua Guo and Tuo Liang represent points systems as the outcome, in part, of attempts to respond to migrant demands for fuller enjoyment of the entitlements of urban citizenship. While noting issues with resource constraints and a city-management style that excludes migrants from consultation, they portray a general trend towards “greater inclusion but a differentiated exclusion.”Footnote 85 The ultimate destination, they argue, is “equal citizenship with local residents” for “peasant workers.”Footnote 86

This verdict is a slightly nuanced version of claims made by the Chinese authorities themselves. Assuming continued restrictions on places and variable school quality as inevitable, officials promote points systems as a just, fair and transparent method of allocating a limited resource.Footnote 87 While equity and equality are often conflated, this approach is generally represented as equitable rather than equal. It “distributes places for compulsory education more fairly and justly,”Footnote 88 or is “more open and transparent … more scientific and reasonable, and distributes educational opportunities more equally”;Footnote 89 or, again, is “conducive to open, transparent, standardized and orderly school enrolment for compulsory education, and the promotion of educational equity.”Footnote 90 Social media postings (possibly from Party members seeking to enhance their own performance metrics) praise the system as “an equitable and impartial creation.” The Shanghai Fengxian district website featured an article entitled “Enrolment by points-based system: fairness for migrant children,” which carried a quote by an education bureau official endorsing the system as “the fairest way for migrant children to enjoy the resources of public schools.”Footnote 91 Jiaxing Xiuzhou's website similarly hails the fairer and more equitable treatment of migrants. The propaganda efforts extend to students themselves. Guangdong's 2012 high school entrance examination featured a question in the moral education (sixiang pinde 思想品德) paper that asked candidates to specify the advantages of points systems. Correct answers included “maintaining social fairness and justice” and “upholding migrant children's right to equality.”Footnote 92

Conviction of the legitimacy and efficiency of points-based approaches is apparently shared by many urban teachers: our interviews in Jiaxing elicited no criticism and several fervent endorsements.Footnote 93 A public primary school teacher recalled that she and her colleagues had formerly been picketed at the school gates by desperate migrant parents, so that “sometimes we needed to call the police for help.” But the creation of a transparent, bureaucratized process for allocating places had put a stop to this: “points make it clearer and simpler: they cannot enter this school because their points are not high enough.” Moreover, the screening out of “low quality” migrants eased classroom management: “children with parents who have stable jobs and long experience of life in the city are more civilized, similar to those holding local hukou.”Footnote 94

The vice-principal of a private migrant school, herself a migrant from Anhui, also endorsed the system.Footnote 95 Jiaxing offers public support to selected private migrant schools that take students through the points system, bringing such schools under closer official supervision. The vice-principal expressed pride that her school had been chosen by the authorities for assistance and “standardization.” Other private migrant schools, denied this status on the grounds of low quality, are increasingly being forced to close, replicating a pattern observed in nearby Shanghai.Footnote 96

A senior teacher at a branch of a major public primary school observed that “migrants and their children enjoy a better life here,” although the system privileges “talented migrant workers” who are employed by larger enterprises.Footnote 97 Even then, migrant children remain largely segregated from local hukou holders. Only five or six migrant children per year are allotted places on the school's main campus; others from qualified families are assigned instead to a branch school with an 80 per cent migrant intake. Those from lower-scoring families tend to enrol at private migrant schools subsidized by the local government. Moreover, many migrants depend on their employer for assistance in navigating the complex application process. As one worker put it, “I really appreciate that my factory has an office to help us deal with the points system. They give instructions on how to collect the necessary documents, and advice on how to gain high points.”Footnote 98

Conclusion

Points systems for allocating school places are operating as sophisticated bureaucratic mechanisms for ranking and sorting the migrant population according to “merit.” The comparison here of district-level differences indicates broad conformity with the objectives of the 2014 NUP, which aims to divert urban growth away from the most intensively developed megacity districts and towards smaller conurbations or less thoroughly urbanized districts. Where authorities seek to attract talent to boost growth in technology or services, metrics prioritize individual “quality”; where they aim to attract or retain lower-skilled factory labour, the quality bar can be set lower, with an emphasis instead on measures of stability and dependability (in residency, employment, payment of taxes, etc.). In districts where the level of urbanization, the local skills profile and overall wealth are highest, the authorities often seek to pull up the drawbridge, allocating public school places only to the most settled and wealthiest migrant families. These systems serve strategies for maximizing human capital accumulation, while reflecting deficit-driven beliefs about migrants and the threat they pose to urban finances, public order and quality of life. They also ensure that those permitted to enjoy urban public services pay for the privilege – indirectly through taxation, if not directly through fees.

“Merit” as calibrated by more prosperous urban districts has come to be defined primarily in terms not of demonstrated individual abilities or educational attainment, but of criteria such as RP status, home ownership or employment length. However, with stable, remunerative employment increasingly dependent on educational credentials, such provisions penalize the poorly educated, effectively excluding almost all migrants.Footnote 99 Economic, financial or employment-based criteria have become aspects of the numeric capital whereby Chinese citizens are ranked and stratified according to their productive capacity. In the most developed and restrictive city districts, such measures betoken merit or fitness in its rawest, most Darwinian sense: the rare migrants with these attributes have proven their capacity to flourish in an extremely hostile environment.

Notwithstanding the justificatory rhetoric of equity or equality, the logic of the points-based approach negates any link between shared citizenship and uniform entitlements and instead embeds and formalizes hierarchical stratification. Whereas some observers claim that points systems represent a staging post on a path towards equal citizenship, this research supports the opposite conclusion: that they lend a gloss of bureaucratic efficiency and meritocratic legitimacy to the unequal apportionment of public goods, rendering inequality harder than ever to challenge. It may seem paradoxical that meritocratic principles are invoked to disadvantage certain pupils before their education has even begun, but the reliance of the system on assessing and ranking parents underlines its core function as a tool of governance, not of educational equity. By ranking individuals by their economic utility or “quality,” points systems recast social class as officially certified hierarchy, reminding aspirational migrants that to be a 21st-century Chinese citizen is to submit oneself to lifelong measurement by the assessment state.

Can meritocratic hierarchy ever be fair or just? Maoists thought not, and today many Western progressives agree with them. But the CCP under Xi Jinping is tying its legitimacy to a forceful case for both the justice and efficiency of meritocracy, applied to the ordering and monitoring of the entire population. Advocates of the “China model” contend that whereas Western inequality simply serves to highlight the hypocrisy of liberal democracy's egalitarian ideals, Confucian hierarchy has a solid moral underpinning.Footnote 100 Certainly, the articulation of meritocracy in China today is more explicit, and its application to governance more ambitious, than elsewhere. Perhaps, also, meritocracy commands greater legitimacy in China in part because it comes wrapped in the mantle of hallowed ancient tradition.

However, as Daniel Markovits argues with respect to the USA, meritocracy in fact enables and legitimates the “dynastic” transmission of privilege.Footnote 101 China appears no different: from the prevalence of princelings atop the CCP, to the predominance of well-heeled urban youth in top universities, meritocracy hardens class divisions. But as in the US, so in China, elites also pay a price for this, especially through the intensity of the educational competition in which they must engage to justify their inheritance. The effects of meritocracy include not just the exclusion of millions from an equal opportunity to compete but also the pervasive intensity of meritocratic competition itself, with its implications for family finances, decisions over fertility and, ultimately, conceptions of what it means to be a dignified, fulfilled human being.Footnote 102

This is why Markovits describes meritocracy as being a “trap” for elites as well as everybody else; for the CCP, however, precisely the features he bemoans reinforce meritocracy's attractiveness as a tool of governance. Points systems deliberately extend and intensify the competitive, individualizing logic of contemporary Chinese society.Footnote 103 They draw migrants, along with their fellow urbanites, into a never-ending, state-umpired meritocratic tournament that consumes private energies while legitimating class divides. Meanwhile, they supply a template for more all-encompassing and sophisticated methods of monitoring the citizenry and incentivizing approved behaviour in ways that extend well beyond the allocation of school places.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their very helpful comments and suggestions on earlier drafts of this article.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Biographical notes

Yi WAN is a PhD student at Kyushu University. Her research focuses on education, culture and social mobility in China. Her doctoral thesis examines the implications of China's new urbanization strategy and of recent household registration policy changes for migrant children's access to public schools during the phase of compulsory education.

Edward VICKERS is professor of comparative education at Kyushu University, and inaugural holder (from Spring 2021) of the UNESCO Chair on Education for Peace, Social Justice and Global Citizenship. He researches the history and politics of education in contemporary East Asia, and the politics of heritage across the region. His recent work includes Education and Society in Post-Mao China (2017, with Zeng Xiaodong), and Remembering Asia's World War Two (2019, with Mark Frost and Daniel Schumacher). He is also president of the Comparative Education Society of Asia.