Clinical Implications

-

• Impulsive aggression (IA) can occur in children, adolescents, and adults, and is a source of serious clinical concern, especially when considering the detrimental impact pediatric IA can have on development.

-

• The ability to properly identify, monitor, and treat IA behavior across clinical conditions is hindered by two major obstacles: (1) the lack of an assessment tool designed for and sensitive to the aggregate set of behaviors comprising IA, and (2) the absence of a treatment specifically indicated for IA symptomatology.

-

• Current assessment tools for aggressive behavior encompass IA symptoms, but few are validated in a population with IA, and they may not sufficiently distinguish these behaviors from other forms of aggression.

-

• Newly emerging solutions, including novel assessment tools and investigational drugs to treat aggression, are discussed with the goal of improving patient outcomes for those with persistent IA.

Introduction

Aggression is one of the most common reasons children are referred to psychiatric clinics.Reference Jensen, Youngstrom and Steiner1 Aggression can be a natural or adaptive response to social cues manifesting as behavior directed toward a perceived threat; however, when the aggressive response becomes exaggerated, it can come with negative consequences for the aggressor and be considered “maladaptive.”1–5 Impulsive aggression (IA) is the most common form of maladaptive aggression seen in the clinical setting, and is associated with a variety of neuropsychiatric disorders.Reference Saylor and Amann4 IA is a reactive, unplanned form of aggression that is eruptive, sudden, and occurs outside of social norms.4–6 Despite how often IA is seen in the clinic, there are two central unmet needs preventing this disorder from being addressed appropriately. First, current metrics available for assessing aggressive symptoms are not designed to accurately differentiate between the various subtypes of aggression.Reference Vitiello, Behar, Hunt, Stoff and Ricciuti7, Reference Raine, Dodge and Loeber8 While there are tools that differentiate proactive from reactive aggression and there is a general consensus among clinicians on the concept of IA,Reference Jensen, Youngstrom and Steiner1, Reference Vitiello, Behar, Hunt, Stoff and Ricciuti7, Reference Raine, Dodge and Loeber8 the lack of a clinically accepted assessment tool to measure IA behavior creates diagnostic and therapeutic barriers. Second, as IA is associated with multiple neuropsychiatric disorders across age groups and is not a distinct diagnostic entity, little research has been conducted to develop and investigate treatments specifically targeted toward IA, particularly pediatric IA.Reference Jensen, Youngstrom and Steiner1, Reference Young, Youngstrom and Findling9 This is a substantial clinical gap in the treatment of IA behavior,Reference Jensen, Youngstrom and Steiner1, Reference Saylor and Amann4 making it difficult for referred children to receive accurate, evidence-based diagnosis and treatment,Reference Saylor and Amann4 creating challenges for clinicians, patients, and parents alike.

An evidence-based nosology for IA behavior across disorders does not yet exist,Reference Young, Youngstrom and Findling9 and IA is not defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th edition) or classified in the International Classification of Diseases. 10 As such, differentiating IA behavior from disorders such as intermittent explosive disorder (IED), conduct disorder (CD), organic aggressive syndrome, and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) can pose a substantial clinical challenge.Reference Connor3, Reference Saylor and Amann4, Reference Coccaro11 Furthermore, IA can occur in each of these disorders (and other common neuropsychiatric disorders) across age groups, but not all individuals with these disorders necessarily exhibit IA. As the treatment approach for a specific disruptive or conduct disorder vs IA may differ, these diagnostic issues complicate the management of aggression and can lead to significant, lasting disturbances for the affected patient.Reference Jensen, Youngstrom and Steiner1, Reference Saylor and Amann4Addressing this diagnostic gap may, in turn, promote the development of more specific treatment recommendations for children and adolescents with IA.

Here, we review the unmet needs surrounding the diagnosis and treatment of IA, with a focus on children and adolescents, and introduce two novel approaches to closing these gaps that are under development. Specifically, a novel assessment tool developed to capture IA behaviors, the IA diary, will be discussed, as well as a novel treatment investigated specifically in children with IA, extended-release molindone. The goal of this review is to improve recognition and treatment of IA early in life, and to assist clinicians in navigating the treatment path for individuals affected by aggressive behavior.

Methods

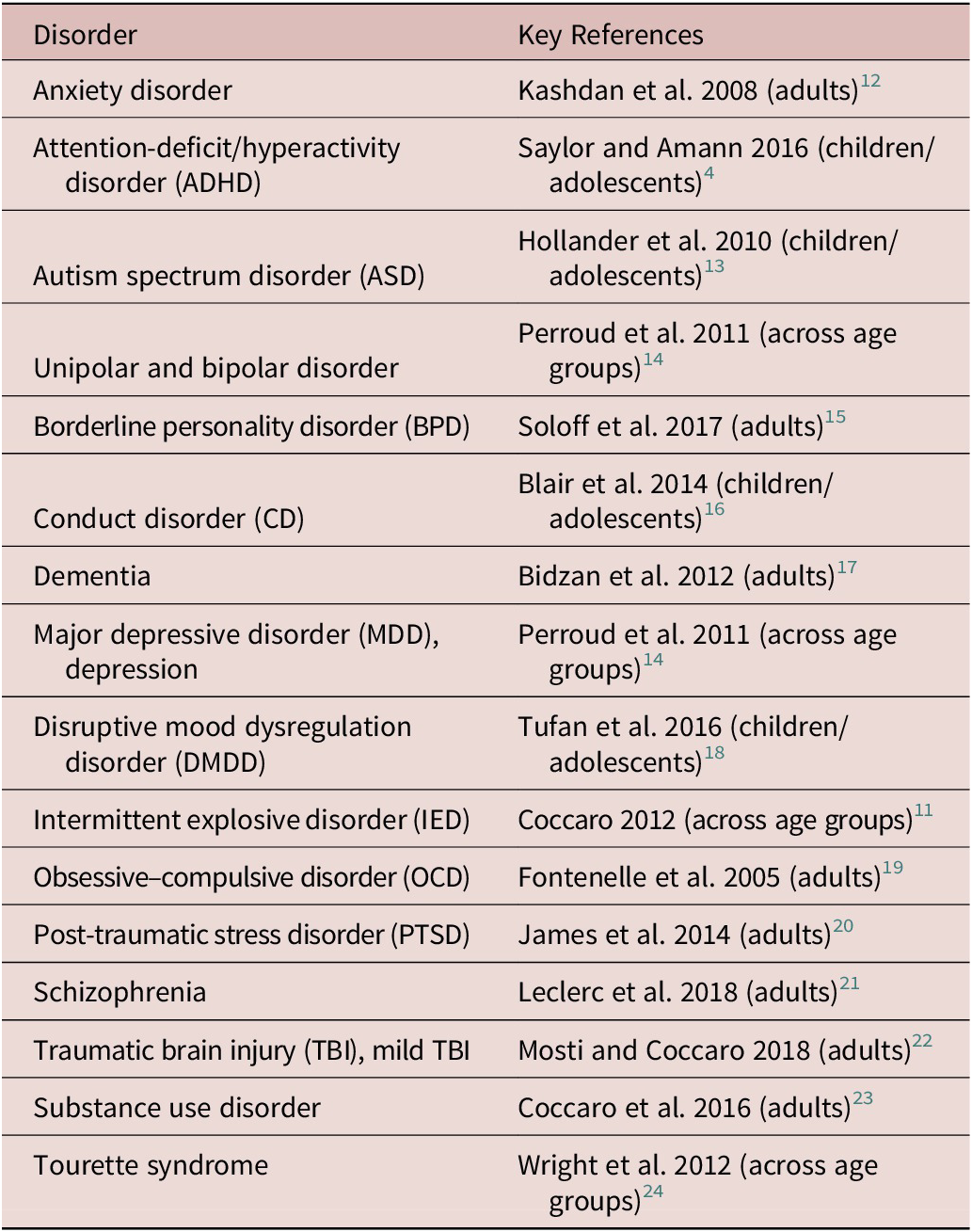

In order to review the current literature on IA, published reviews and clinical research characterizing or investigating treatments for IA were searched on PubMed and ClinicalTrials.gov using the search terms “impulsive aggression” and “treatments” or “approved agents” with no limits in time. Results yielded approximately 200 references that were manually filtered to confirm relevance to IA as opposed to other aggression subtypes across multiple disorders and within multiple age groups. The key results of this search are summarized in Table 1 (disorders exhibiting IA) and Table 3 (treatments used to manage symptoms related to IA).

Table 1. Impulsive Aggressiona Across Neuropsychiatric Disorders.

a Studies included disorders found in both child/adolescent and adult populations; population reviewed in key reference noted.

Understanding Impulsive Aggression as a Measurable and Treatable Symptom Cluster

Maladaptive aggression, which affects 10% to 25% of children and adolescents, based on reports of psychiatric referrals and problem behavior, is an umbrella term that encompasses various subtypes of aggression including proactive aggression, reactive aggression, and IA.Reference Saylor and Amann4, 25–27 When aggression becomes maladaptive, it is a result of underlying central nervous system malfunction resulting in a response disproportionate to a social or environmental trigger.Reference Blair2, Reference Saylor and Amann4, Reference Connor28 Within this context, reactive aggression can be described as a defensive, hostile response to a frustration, while proactive aggression can be described as planned, deliberate, goal-directed aggression.Reference Connor, Newcorn and Saylor5 In this article, we define IA behavior within the pediatric setting as a type of reactive aggression that is unplanned (not premeditated), immediate, and explosive in nature.Reference Jensen, Youngstrom and Steiner1, Reference Saylor and Amann4, Reference Barratt, Stanford, Dowdy, Liebman and Kent29 Despite being one of the most detrimental symptoms reported by families impacted by aggression,Reference Saylor and Amann4 IA is not a single, monolithic entity. In patients with IA, the perceived need for an immediate reaction to an event hinders the ability to consider an alternative and more appropriate response to frustration or to an interpreted threat, leading to “emotional impulsivity.”Reference Connor3, Reference Saylor and Amann4 IA presents as an associated feature across multiple pediatric neuropsychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders (Table 1), somewhat like a fever presents in an illness.Reference Jensen, Youngstrom and Steiner1, Reference Connor3, Reference Saylor and Amann4 The epidemiology of pediatric IA across neuropsychiatric disorders remains poorly described.30–33 Within these disorders, IA behaviors can present as early as 4.5 years of age, although IA has not yet been comprehensively characterized throughout all life stages.Reference Jensen, Youngstrom and Steiner1, Reference Saylor and Amann4 Although the pathophysiology of IA throughout childhood and adolescence is similarly not fully understood, it is thought to be a result of altered central nervous system biology interacting with stressful environments.Reference Blair2 The current primary hypothesis is that the neural circuit regulating the acute threat response is dysregulated in patients with IA, providing a rationale for the use of dopaminergic and serotonergic modulators to treat aggression.Reference Blair2, Reference Potegal34 Furthermore, agents targeting noradrenergic tone and/or influencing indirect effects of norepinephrine on these neural circuits have been used to treat aggression, and support the rationale for noradrenergic modulators in the treatment of pediatric IA.Reference Gurnani, Ivanov and Newcorn25, Reference Connor28

Neuropsychiatric Conditions Associated with Impulsive Aggression: Spotlight on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

GuidelinesReference Jensen, Youngstrom and Steiner1 specify that aggression, including IA, should be evaluated within well-defined disorders (eg, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder [ADHD], autism spectrum disorder, depression, bipolar disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder [PTSD]).Reference Jensen, Youngstrom and Steiner1, Reference Connor and McLaughlin35 As most evidence-based research on aggressive symptoms is within the context of ADHD,Reference Jensen, Youngstrom and Steiner1 we will focus on studies in individuals with a primary diagnosis of ADHD. The prevalence of ADHD is 9.5% in children ages 6 to 11 years and 11.8% in adolescents ages 12 to 17 years in the United States.36, Reference Pastor, Reuben, Duran and Hawkins37 In a post hoc analysis of the Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD (MTA), a substantial proportion (54%) of children with ADHD exhibited clinical aggression prior to treatment.Reference Jensen, Youngstrom and Steiner1 Furthermore, IA is the predominant subtype among preadolescent children with ADHD and aggression.Reference Saylor and Amann4 After 14 months of ADHD treatment in the MTA study,38 26% of children whose symptoms were managed by ADHD medication exhibited persistent aggressive behavior.Reference Jensen, Youngstrom and Steiner1, 38 In another study, IA was found to be significantly more common than proactive aggression in a sample of children and adolescents clinically referred for ADHD.Reference Connor, Chartier, Preen and Kaplan39 Specifically, aggression motivation, as assessed by the Proactive/Reactive (impulsive) Aggression Rating Scale, demonstrated that children and adolescents with ADHD had significantly higher IA scores vs proactive aggression scores.Reference Connor, Chartier, Preen and Kaplan39 The persistence of these symptoms with available medications indicates that alternative, more effective treatments are needed.

In the context of ADHD, children with IA suffer from a range of social issues, including bullying, estrangement from peers, and fewer friendships, which can extend into adolescence.Reference Saylor and Amann4 While the focus of the present review is on IA in children and adolescents, properly diagnosing IA early in life is important in promoting optimal development for a healthy adulthood.Reference Dowson and Blackwell40 Longitudinal studies of individuals who had ADHD in their youth suggest that there are “life consequences” exacerbated by aggressive-hyperactive-impulsive behavior, including an increased risk for psychosocial, academic, or behavioral problems, as well as risk for legal issues.Reference Saylor and Amann4 These burdens can impact not just the individual, but the entire family—the parents of children with severe aggression are also more likely to rate themselves as feeling impaired and request changes to their child’s treatment regimen—causing higher rates of medication use despite a lack of strong evidence-based treatments specific to IA.Reference Saylor and Amann4

The Unmet Need: Diagnosing IA Behavior

As IA is a multidimensional construct overlapping with multiple subtypes of aggression,Reference Mathias, Stanford and Marsh41 defining IA within the context of other primary disorders presents several potential obstacles. One such roadblock is that the measurement of IA is difficult and complex using existing clinical assessment tools. While psychometric evaluations such as the Retrospective-Modified Overt Aggression Scale (R-MOAS),Reference Tsiouris, Kim, Brown and Cohen42 the Aggression Questionnaire,Reference Vitiello, Behar, Hunt, Stoff and Ricciuti7 and the Reactive-Proactive Aggression QuestionnaireReference Raine, Dodge and Loeber8 are currently used to evaluate the severity of aggressive behavior and categorize aggression by subtype (planned vs affective/impulsive), respectively, they are not designed to differentiate and assess IA-related behaviors over time.Reference Jensen, Youngstrom and Steiner1, Reference Vitiello, Behar, Hunt, Stoff and Ricciuti7, Reference Raine, Dodge and Loeber8, Reference Mathias, Stanford and Marsh41, Reference Jurewicz, Takakura and Augello43, Reference Kaat, Farmer and Gadow44 Reactive aggression vs predatory aggression (motivated, controlled, subversive toward a goal) can be measured by the Aggression Questionnaire, for example, yet this scale relies on caregiver-reporting and reliable recall of aggressive episodes over a 1-month period.Reference Vitiello, Behar, Hunt, Stoff and Ricciuti7, Reference Connor28 Recently, a novel aggression scale called the Impulsive/Premeditated Aggression Scale (IPAS) was validated in psychiatric patients in Mexico, although this scale does not question specific behaviors and instead probes the patient’s impression of his or her own behavior (ie, “I consider the acts to have been impulsive” vs “I planned when and where my anger was expressed”).Reference Romans, Fresan and Senties45 Furthermore, this scale does not provide a mechanism for temporal tracking of IA behavior, a feature that would be useful during both diagnostic assessment and clinical investigation of response to therapy.Reference Romans, Fresan and Senties45 In contrast, the R-MOAS does probe specific behaviors (ie, “breaks objects, smashes windows”), but similarly does not provide information on the nature of these behaviors over time and relies on recall over a 1-week period for behavior reporting.Reference Knoedler46 The R-MOAS was designed to monitor symptoms in psychiatric inpatients and does not capture the variety of IA seen in the outpatient setting. These gaps create a challenge in distinguishing IA from disruptive mood disorders such as IED, CD, or ODD, which can exhibit differing frequencies of outbursts over time.10 This lack of a clinically accepted, specific metric for IA causes difficulties in distinguishing IA from other forms of aggression and prevents proper symptom identification and quantification.Reference Mathias, Stanford and Marsh41

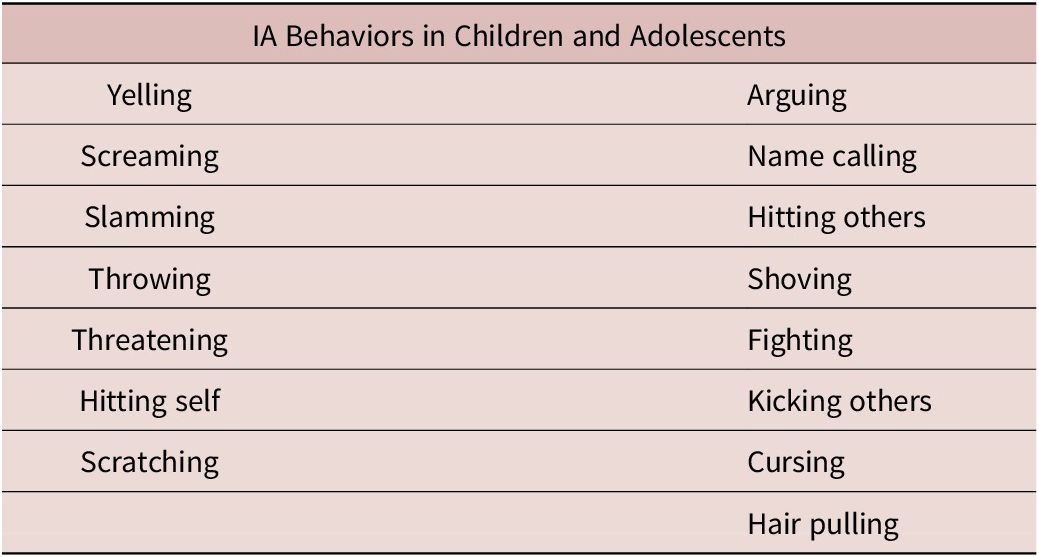

A novel measurement tool, the IA diary, was developed to specifically assess the frequency and type of IA behaviors in children with ADHD with the goal of improving the assessment and diagnosis of IA symptomatology.Reference Ceresoli-Borroni, Liranso and Brittain47 Based on reporting prevalence in a sample population, 15 IA behaviors were psychometrically validated in children with ADHD (yelling, screaming, slamming, throwing, threatening, hitting self, scratching, arguing, name calling, hitting others, shoving, fighting, kicking others, cursing, hair pulling; see Table 2), and qualitatively supported in adolescents.Reference Ceresoli-Borroni, Liranso and Brittain47, Reference Ceresoli-Borroni, Liranso and Brittain48 Exploratory analysis and item response theory modeling of the IA diary revealed two subdomains within its item set, wherein arguing, cursing, name calling, shoving, hair pulling, fighting, hitting others, and kicking others represented more severe aggressive behavior toward others, as opposed to the aggression items not necessarily directed at another person.Reference Ceresoli-Borroni, Liranso and Brittain47 Importantly, while some of the behaviors in the IA diary are also featured in the R-MOAS, the contemporary nature of the IA diary provides a unique, novel mechanism for tracking changes in IA behavior over time.Reference Knoedler46 More specifically, the IA diary is designed to capture IA behaviors as they happen (episodically) in real time.Reference Ceresoli-Borroni, Liranso and Brittain47 Furthermore, in contrast to the R-MOAS, the IA diary was developed after an initial study assessing the frequency of IA-cluster behaviors in children, thus allowing for more reliable assessment of IA-specific behaviors, as opposed to behaviors that may be more common in other forms of aggression. The development of such new tools may improve accurate diagnosis of IA and enhance clinical monitoring of potential treatments for this behavior. Future developments that seek to better understand IA behavior, and perhaps any potential compounding environmental factors (such as familial, societal, or economic stressors), may also improve the clinical approach to identifying IA symptomatology.Reference Jensen, Youngstrom and Steiner1, Reference Connor and McLaughlin35

Table 2. Impulsive Aggressive (IA) Behaviors Assessed in the IA Diary

The Unmet Need: Treating Impulsive Aggression

Clinical studies have demonstrated that IA appears to be treatment responsive compared to other forms of maladaptive aggression, particularly predatory aggression,Reference Connor, Chartier, Preen and Kaplan39, Reference Malone, Bennett and Luebbert49 yet it often remains refractory to interventions targeting the primary neuropsychiatric disorder.Reference Saylor and Amann4 The current treatment paradigm for IA is to first treat the primary disorder using monotherapy when possible in conjunction with psychosocial interventions, and if the first-line pharmacotherapy fails to manage aggression, utilize combined pharmacotherapy.Reference Jensen, Youngstrom and Steiner1, Reference Gurnani, Ivanov and Newcorn25, Reference Scotto Rosato, Correll and Pappadopulos26, Reference Pappadopulos, Macintyre Ii and Crismon50 While a threshold for prescribing medication for IA is difficult to establish in children and adolescents, given the issues surrounding its diagnosis, current guidelines suggest that the type of aggressive behavior should be characterized prior to treatment.Reference Felthous and Stanford51 Evidence-based psychosocial interventions, including educational and behavioral techniques, should be first-line treatments for aggression and implemented through all phases of care.Reference Jensen, Youngstrom and Steiner1, Reference Gurnani, Ivanov and Newcorn25, Reference Scotto Rosato, Correll and Pappadopulos26, Reference Pappadopulos, Macintyre Ii and Crismon50, Reference Knapp, Chait, Pappadopulos, Crystal and Jensen52

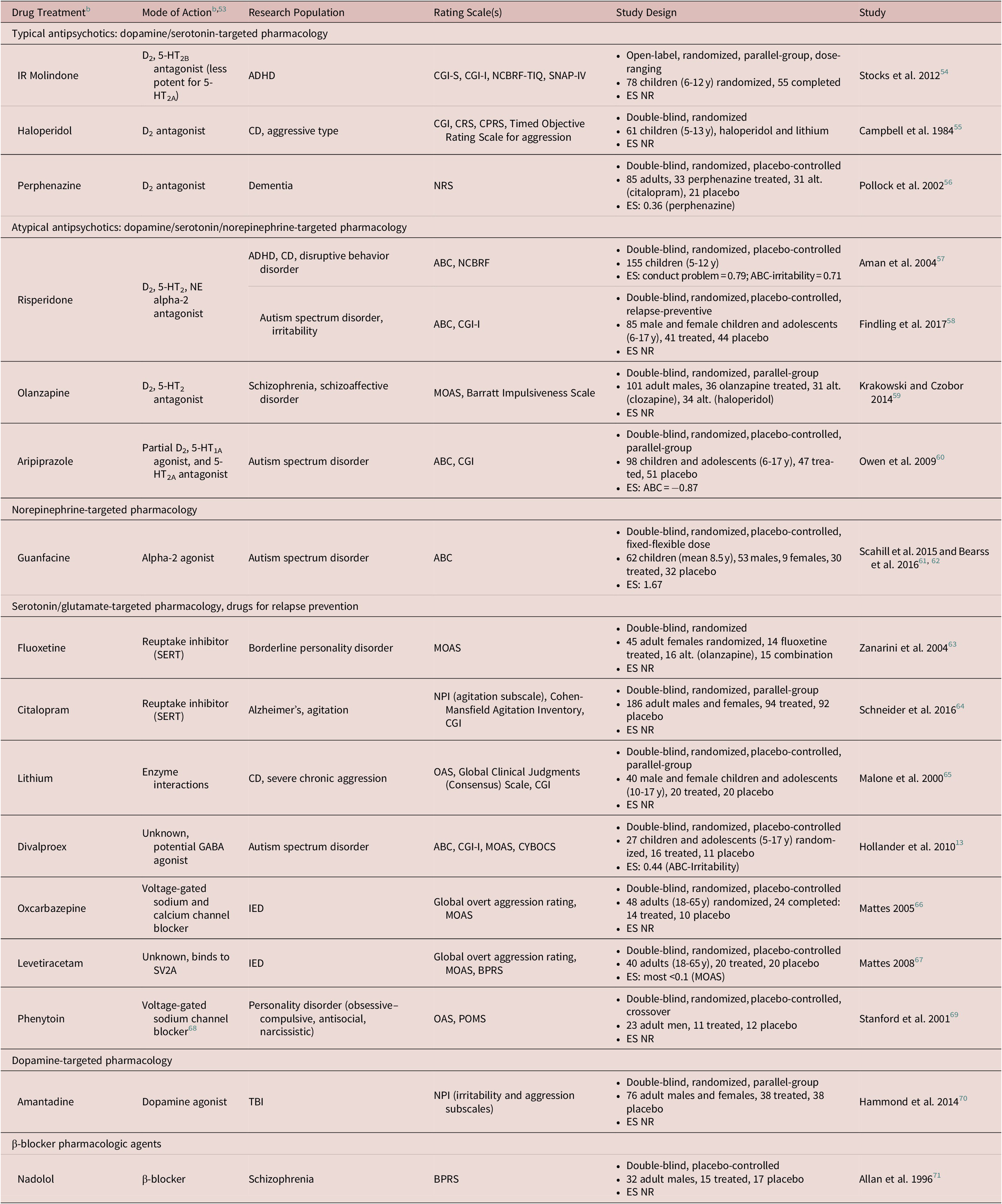

Despite the logic behind these guidelines, in reality, pharmacologically based treatment of IA is a significant challenge in clinical practice across age groups, as few evidence-based treatments specifically developed and approved for IA behavior are currently available.Reference Connor3 Even so, aggression-targeted treatments with antipsychotics and other psychotropic medications have been explored for IA and other forms of maladaptive aggression (a highlighted list of drugs used to treat aggression is provided in Table 3). For example, antipsychotics such as risperidone are indicated for irritability, including aggression, associated with autism.72 Nonetheless, IA is not yet adequately managed in many children and adolescents being treated for core symptoms of neuropsychiatric conditions comorbid with IA—in the context of IA in ADHD, the current paradigm fails to ameliorate symptoms for 36% to 44% of children.Reference Jensen, Youngstrom and Steiner1, Reference Stocks, Taneja, Baroldi and Findling54, Reference Aman, Binder and Turgay57 In youths with ADHD, aggressive behaviors may not be mitigated by standard pharmacotherapy used to treat ADHD, and combination pharmacotherapy with atypical antipsychotics (drugs initially developed for the treatment of psychosis, but often used for other indications; D2, 5-HT2 receptor antagonists)Reference Seeman73 have only moderate effects.Reference Jensen, Youngstrom and Steiner1, 38, Reference Stocks, Taneja, Baroldi and Findling54, Reference Aman, Binder and Turgay57, Reference Aman, Bukstein and Gadow74, Reference Kronenberger, Giauque, Lafata, Bohnstedt, Maxey and Dunn75 Particularly given the risk of unwanted side effects often associated with antipsychotics, randomized, controlled trials are needed to determine the optimal therapeutic combination for persistent IA in children and adolescents.Reference Jensen, Youngstrom and Steiner1, Reference Saylor and Amann4

Table 3. Select Studies Investigating Treatment of Aggressive Behaviora Within Neuropsychiatric Disorders

Abbreviations: IR, immediate release; ES, effect size; NR, not reported; SERT, Serotonin Transporter; SV2A, Synaptic Vesicle protein 2A.

Abbreviations (rating scales): ABC, Aberrant Behavior Checklist; ABS, Aggressive Subscale of the Antisocial Behavior Scale; BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; CAS-P, Children’s Aggression Scale-Parent; CAS-T, Children’s Aggression Scale-Teacher; CBCL, Child Behavior Checklist; CGI-I/S, Clinical Global Impression-Improvement/Severity; CPRS-R:L, Conners Parent Rating Scale-Revised, Long Form; CPRS, Children’s Psychiatric Rating Scale; CRS, Conners Rating Scale/Questionnaire (teachers and parents); CYBOCS, Child-Yale–Brown Obsessive–Compulsive Scale; MOAS, Modified Overt Aggression Scale; NCBRF, Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form; NCBRF-D, Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form-Typical IQ, Disruptive Total Score; NCBRF-TIQ, Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form-Typical Intelligence Quotient; NPI, Neuropsychiatric Inventory; NRS, Neurobehavioral Rating Scale; OAS, Overt Aggression Scale; POMS, Profile of Mood States; R-MOAS, Retrospective-Modified Overt Aggression Scale; SNAP-IV, Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham Questionnaire; WAI, Weinberger Adjustment Inventory.

Abbreviations (disorders): ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; CD, conduct disorder; IED, intermittent explosive disorder; OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder; ODD, oppositional defiant disorder; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; TBI, traumatic brain injury.

a Studies include those conducted within child, adolescent, and adult populations.

b All agent classes are listed per Neuroscience-based Nomenclature (NbN) glossary terms where applicable for agent pharmacology and mode of action.

Studies utilizing typical and atypical antipsychotics for IA continue to report extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) and metabolic side effects in children and adolescents, respectively, underscoring the need for treatments directly targeting the causes of IA with fewer side effects. Such issues are particularly of concern given the young population in need of therapy for IA and its chronic nature.Reference Saylor and Amann4 In children with ADHD, risperidone in addition to optimized stimulant therapy and parent training resulted in moderate but significant improvements in severe aggression that were sustained in an extended 12-week blinded study.Reference Findling, Townsend and Brown58, Reference Aman, Bukstein and Gadow74 However, behavioral outcomes did not differ significantly at 1 year and acute effects seen at 9 weeks decreased over time.Reference Saylor and Amann4, Reference Findling, Townsend and Brown58, Reference Aman, Smith and Arnold76, Reference Gadow, Brown and Arnold77 While such behavioral therapy in youths with aggression and ADHD has shown moderate success, patients undergoing psychosocial interventions often remain symptomatic. Clinical trials evaluating risk–benefit profiles of medications for the treatment of persistent IA will serve to improve clinical practice by identifying agents with maximal efficacy and the fewest AEs in children and adolescents.Reference Jensen, Youngstrom and Steiner1, Reference Saylor and Amann4 As current therapies fail to sufficiently maintain control of IA symptoms and come with adverse side effects, new pharmacotherapy is needed to safely and effectively treat IA.Reference Jensen, Youngstrom and Steiner1, Reference Stocks, Taneja, Baroldi and Findling54

At the time of publication, new investigational therapies are emerging as potential candidates for the treatment of IA. Previous studies reported that immediate-release molindone improves aggressive behavior in children with CD.Reference Stocks, Taneja, Baroldi and Findling54, Reference Greenhill, Solomon, Pleak and Ambrosini78 On the spectrum of antipsychotic-associated side effects across age groups, immediate-release molindone is a dopamine D2 receptor antagonist with serotonergic activity that has a low propensity for causing weight gain and elicits little to no parkinsonism or EPS.78–83 SPN-810 (extended-release molindone), a suggested IA modulator,Reference Robb, Schwabe and Ceresoli-Borroni6 is currently under development as a novel treatment for patients being treated for ADHD with IA, and is designed to deliver more constant plasma drug concentrations with longer dosing intervals.Reference Ceresoli-Borroni, Nasser and Adewole83, Reference Ceresoli-Borroni, Adewole, Liranso and Findling84 To date, the efficacy and safety of SPN-810 have been evaluated in a multicenter, phase 2b, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging (12-54 mg, stratified by weight) study in children ages 6 to 12 years with ADHD (N = 118) and persistent aggression that was impulsive in nature.Reference Ceresoli-Borroni, Nasser and Adewole83 SPN-810 administered at the low (12 mg/18 mg) and medium (24 mg/36 mg) doses resulted in significant improvements from baseline in R-MOAS vs placebo, and remission rates (subjects with R-MOAS score ≤ 10), depending on weight, were at least twice that of the placebo group.Reference Ceresoli-Borroni, Nasser and Adewole83 SPN-810 was generally well tolerated, with headache, sedation, and increased appetite being the most common AEs; AEs associated with EPS were infrequent and resolved with discontinuation.Reference Ceresoli-Borroni, Nasser and Adewole83 Given the suggested efficacy and safety of SPN-810 in children and adolescents, investigational therapies such as this could represent a promising therapeutic approach toward pediatric IA. Importantly, it has not yet been investigated if other dopamine-, serotonin-, or norepinephrine-based pharmacologic agents used at low doses similarly retain antiaggressive function.

Results from a search for additional recruiting or ongoing clinical trials investigating medicinal IA therapies indicated that a pilot study of phenytoin for the treatment of IA associated with PTSD is ongoing, though the recruitment status is unknown at the time of this publication (clinical trial identifier: NCT00333931).85 Also, a phase 1/2 clinical trial is recruiting subjects for the investigation of a neurokinin (NK) 1 antagonist for the treatment of aggression in patients with IED and/or DMDD, though this study does not investigate IA specifically (clinical trial identifier: NCT02989779).86 The investigation of other therapeutics specifically for their antiaggressive effects may provide further information on the spectrum of drugs that could be applied to the treatment of IA symptoms.

Conclusion

There remains a clinical gap in accurately diagnosing and adequately treating IA behavior in children and adolescents. Differential diagnosis between IA, antisocial behaviors, and disruptive disorders will be improved with the development of new tools such as the IA diary. As forms of aggression (eg, predatory vs reactive) respond differently to treatment,Reference Malone, Bennett and Luebbert49 delineating the subtype of aggressive behavior is critical to determining optimal therapeutic approach. New tools such as the IA diary, although currently validated only in youths with ADHD, may also help evaluate the efficacy of emerging therapies for IA behavior across neuropsychiatric disorders if validated in the context of other primary disorders in the future. Investigational pharmacotherapies developed for the treatment of pediatric IA may provide a more specialized treatment path for IA. Closing these knowledge gaps regarding the characteristics unique to IA will help foster the development of safe, effective pharmacotherapies more specifically targeted to the underlying causes of IA behavior.

Acknowledgments

Editorial support was provided by IMPRINT Science, New York, NY, USA.

Funding

This work was funded by Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA. Azmi Nasser, Welton O’Neal, Stefan Schwabe, Gianpiera Ceresoli-Borroni, and Shawn A. Candler, employees of Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Inc., were involved in the design, analysis, and reporting of the literature review.

Disclosures

A.S.R.: Actavis/Forest Laboratories (consultant, research support, travel support); Aevi Genomic Medicine, Inc. (data safety monitoring board); AACAP (honorarium, travel support); AAP (honorarium, travel support); Bracket (consultant); Case Western Reserve (honorarium, travel support); Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Society of Greater Washington (honorarium); College of Neurologic and Psychiatric Pharmacists (honorarium, travel support); Eli Lilly (royalties); GlaxoSmithKline (royalties); Guilford Press (royalties); Johnson & Johnson (royalties); Lundbeck/Takeda (advisor, research support, travel support); Neuronetics (data safety monitoring board); Neuroscience Education Institute (honorarium, travel support); Nevada Psychiatric Association (honorarium, travel support); National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (research support); NICHD (advisor); NIMH (data safety monitoring board); NINDS (research support); NACCME (honorarium, travel support); Pfizer, Inc. (research support, stock/equity, travel support); Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (advisor, travel support); Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (research support); SyneuRx (research support); University of Cambridge (advisor). D.F.C.: Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (consultant); Shire Pharmaceuticals (grant). B.H.A.: Tris Pharma, Inc.; Rhodes Pharmaceuticals L.P.; Neos Therapeutics, Inc.; Takeda Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Lundbeck, Inc.; Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd.; Shire Plc; Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (grants). B.V.: Consultant for Medice and Teva Pharm. A.N., W.O., S.S., G.C.-B., and S.A.C.: Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (employee). J.H.N.: Served as an advisor and/or consultant to Akili Interactive, Alcobra, Arbor, Cingulate Therapeutics, Enzymotec, KemPharm, Lundbeck, Medice, NLS Pharma, Pfizer, Rhodes, Shire, Sunovion, and Supernus, and received research support from Enzymotec, Lundbeck, and Shire. J.K.B.: In the past 3 years has been a consultant to, member of advisory board of, and/or speaker for Janssen Cilag BV, Eli Lilly, Lundbeck, Shire, Roche, Medice, Novartis, and Servier. He has received research support from Roche and Vifor. He is not an employee of any of these companies, and is not a stock shareholder of any of these companies. He has no other financial or material support, including expert testimony, patents, royalties. R.L.F.: Acadia (consultant); Aevi (research support, consultant); Akili (research support, consultant); Alcobra Pharma (research support, consultant); Allergan (research support, consultant); AACAP (speaker’s bureau); Amarex Clinical Research (consultant); American Psychiatric Press (royalties); Arbor (consultant); Bracket (consultant); Daiichi-Sankyo (speaker’s bureau); ePharmaSolutions (consultant); Forest Laboratories, Inc. (research support); Genentech (consultant); Ironshore Pharmaceuticals & Development, Inc. (consultant); KemPharm, Inc. (consultant); Luminopia (consultant); Lundbeck, Inc. (research support, consultant); Merck & Co., Inc. (consultant); National Institutes of Health (research support, consultant); Neurim Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (research support, consultant); Neurim (research support, consultant); Noven (consultant); Nuvelution (consultant); Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc. (consultant); PCORI (research support); Pfizer, Inc. (research support); Physicians Postgraduate Press (consultant); Roche (research support); Sage Therapeutics (royalties); Shire (research support, consultant); Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (research support, consultant); Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (research support, consultant); SyneuRx (research support); Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. (consultant); TouchPoint (consultant); Tris Pharma, Inc. (consultant); Validus Pharmaceuticals LLC (research support, consultant).