The integration process of cybersecurity certification by the European Union (EU) had surprisingly ended in a policy regime that is very close to what is already in place. Despite promises by EU policymakers to “completely replace” and “fundamentally change” the ecosystem for certification (EU Commission 2017), the policymaking process ended up with a regime that is strikingly similar to current arrangements.

Theoretically, this is a case of both “market integration” – creating a market for certified products, and an “integration of core state powers” – mobilising the capacity to set standards and certify nationally sensitive infrastructures. Post-integration, these two types of integration differ on the design they envision for an integrated policy regime, suggesting either supranational or intergovernmental policy arrangements, with varying levels of control for national authorities. This study aims to uncover how the EU cybersecurity certification policy regime has been shaped between these two integration rationales and discuss the causal mechanisms that drove policy design decisions to create a rather marginal change from current certification practices.

The paper asks (1) how and to what extent the cybersecurity certification regime has been integrated by the EU? and (2) how can we explain the rather limited nature of Europeanisation in this case? The first research question is an empirical question that uncovers the dependent variable of this study – the changes in the EU cybersecurity policy regime after the recent integration attempt. The second question is a theoretical one and aims to explain the chosen post-integration policy design, based on classic theories of EU integration – neofunctionalism and intergovernmentalism.

Empirically, this article addresses the puzzle of how come an emerging policy regime at the EU level only marginally diverges from the current regime that is in place. How come a policy regime that aimed to solve functional problems in the cybersecurity certification ecosystem does not really change current certification practices?

This case study questions assumptions from the literature according to which EU integration cases are classified across mutually exclusive dynamics of either market or core states powers integration (e.g. Majone Reference Majone2006; Genschel and Jachtenfuchs Reference Genschel and Jachtenfuchs2016, Reference Genschel and Jachtenfuchs2018). Market integration emphasises joint gains from harmonised trade settings and usually settles the shape of integration based on the largest common multiple with a decisive role to EU’s supranational institutions. The integration of core states powers, in contrast, involves contested resource mobilisation of national capacities to the EU level, which are derived from the state’s monopoly on national security, defense, and coercion. For such integration, state elites are expected to prefer intergovernmental over supranational arrangements with a narrowly defined and tightly controlled EU mandate.

In the case of EU cybersecurity certification, we see both of these dynamics in-play, in ways that challenge the dichotomous understanding of EU integration dynamics and post-integration policy design. By certifying products for cybersecurity, the EU is at one and the same time creating a harmonised market for certified products, for which supranational institutions are expected to play a central role, and mobilising standardisation and certification capacities that are closely related to states’ sovereignty and are likely to be organised through intergovernmental arrangements. Moreover, this is the first time the EU aims to shift national decisionmaking and capacities over cybersecurity to supranational or intergovernmental levels. The goal then is to explain the dynamics of this potentially innovative phase in the EU cybersecurity policy space.

Through a process-tracing analysis based on 41 policy documents and 18 interviews, this study deconstructs EU cybersecurity certification into standardisation, accreditation, certification and evaluation components, analyses and labels each of these multilevel regime components according to their national, intergovernmental or supranational nature, and explains how and to what extent mainstream theories of EU integration – neofunctionalism and intergovernmentalism – explain how cybersecurity certification has been “Europeanized” in a rather limited fashion.

The findings show how the design of a limited Europeanised regime serves functional and political goals for stakeholders involved. Three different causal mechanisms explain this puzzling outcome to a different degree, revealing drivers for the creation of a “Europeanization on Demand” model in the space of cybersecurity certification. This highlights the difficulty of designing market integration policy regimes for issues that touch upon core state powers.

The article is organised into six sections. The next section is a review of the literature on EU integration dynamics which underlines the theoretical motivation to study the recent EU attempt to integrate cybersecurity certification. This section also reviews the literature on EU integration theories and EU cybersecurity from which research hypotheses are derived. The second section presents the chosen analytical framework and methodology for answering the research questions, detailing the indicators used for testing each hypothesis. The third section is an empirical analysis of the development of the EU cybersecurity certification regime over the last two decades. This section frames the dependent variable of this research – temporal variance in the EU cybersecurity certification regime. The fourth section tests the three research hypotheses, the fifth discusses the results, and the last section concludes.

Literature review: cybersecurity certification between two models of EU integration

The literature on EU integration has been classifying drivers and dynamics for integration based on two “models” of integration (Genschel and Jachtenfuchs Reference Genschel and Jachtenfuchs2013, Reference Genschel and Jachtenfuchs2016, Reference Genschel and Jachtenfuchs2018). The first is “Market Integration,” which describes the integration of national economies over social and economic issues along with the preservation of core national sovereignty (e.g. Majone Reference Majone2006). Demand for integration is driven by economic externalities and spillover effects that are derived from the interdependence between economic sectors across member states. This creates collective benefits from supranational policy coordination that push stakeholders to agree on integration measures.

This type of integration is promoted through regulatory unification. It is dominated by joint gains from trade and creates a market for “EU-labelled” products, under the assumption that trade liberalisation benefits all participating states, at different levels. Distributive conflicts between states are usually limited as the most affected actors are businesses that have to comply with new regulatory requirements. Such “classic” mode of integration allows the EU to operate without significant powers over issues that are close to state sovereignty.

The second “model” of EU integration in the literature captures the increasingly important role of EU institutions in areas that are traditionally reserved to sovereign states. Such integration, of core state powers, takes place through resource mobilisation of national capacities to the EU level. Those capacities are derived from the state’s monopoly on national security, defense, coercion, and taxation. When national powers restrict market freedoms, market players are likely to lobby for more EU regulation. But since the EU is operating here beyond Pareto-improving issues of market creation, the supply of integration becomes a contested issue. The creation of “state” capacities at the EU level increases the likelihood of zero-sum conflicts between states. This mostly affects state elites who are likely to prefer intergovernmental arrangements or national veto points to secure a role for national officials in managing the newly created capacities. In such integration dynamics, the EU mandate is usually narrowed by member states and the role of supranational institutions is reduced. Ultimately, state elites are usually sceptical towards supranational architectures that empower Eurocrats.

Post-integration, the two models differ on the design they envision for an integrated policy regime. While market integration dynamics often lead to supranational policy regimes that advance the creation of common standards and cast a central role to EU institutions, the dynamics of integration of core state powers are likely to lead to intergovernmental policy regimes that create mutual recognition agreements between member states, along with veto points for national policymakers.

The integration of cybersecurity certification is at one and the same time a case of market and core state powers integration. It leaves us with mixed expectations regarding what kind of policy regime to expect. On the face of it, certification is about market creation. By certifying products for cybersecurity, the EU helps create a harmonised market for these products, overcoming national fragmentation in certification schemes, and creating mutually recognised certificates across the Union. Supranational institutions are expected to play a key role in coordinating the development of standards and authorising mutually recognised certificates in member states. At the same time, the integration of cybersecurity certification involves practices that are close to states’ sovereignty. These include national capacities to certify sensitive infrastructures, national standard setting for security certificates and national monitoring of certification bodies to ensure the quality of their processes and outputs. These capacities are directly related to the security efforts of the state, and as such, their integration is likely to follow core state powers’ integration dynamics, leading to intergovernmental arrangements with significant control points for member states.

Previous attempts to integrate cybersecurity policies in the EU indicate that integration attempts thus far did not include the mobilisation of national cybersecurity capacities to either intergovernmental or supranational levels. Initially, the EU was influential in this policy space only through soft tools. It promoted cooperation between actors by establishing the European Agency for Network and Information Security (ENISA) in 2004, the European Cyber Crime Center (EC3) in 2013 and the Contractual Public-Private Partnership in 2016. Up to that point, cybersecurity policy regimes remained national, with the EU providing coordination tools and expertise. In 2016, however, the EU has become more active, using legislative tools for the first time. It enacted the Network and Information Security (NIS) Directive, setting minimum levels of protection in member states by arguing that disruption of networks in one state can have wider effects on others and create a barrier to the EU’s Single Market approach (Christou Reference Christou2016). The Commission viewed this Directive as a shift from the hands-off meta-governance approach to a hands-on mandatory stance, in order to improve the protection from and monitoring of cyber incidents among member states (Christou Reference Christou2019). The goal was to incentivise member states to adopt practices that would lead to more effective cybersecurity governance at the national level.

Thus, the NIS Directive followed the trend of leaving cybersecurity responsibilities solely to national authorities. It sets standards for institutional development and private sector behaviour but does not shift national cybersecurity decision-making processes to extra-national levels. In contrast, the integration of cybersecurity certification aims to do exactly that. The EU seeks ways to overcome national fragmentation in standard setting and certification by creating new rules for the market of certified products, changing the way national authorities set standards, monitor certification bodies and certify for cybersecurity. This is expected to be a much more contested cybersecurity integration attempt than the previous ones, with no clear expectations for what kind of a policy regime is likely to arise.

Research hypotheses

In order to explain why integration ended up with certain policy design, that only slightly diverges from the existing certification regime, this study relies on competing theories of EU integration – neofunctionalism and liberal intergovernmentalism – and seeks to understand their explanatory power for policy design decisions in this case. The theories differ in the arena they highlight and the causal mechanisms that connect actions to policy outcomes. Consequently, each hypothesis below suggests different drivers and dynamics of EU integration, viewing integration as an episode of either path-dependent spillovers or intergovernmental bargaining.

The first two hypotheses draw from the neofunctionalism theory and differ on the micro-mechanisms for policy change. Neofunctionalism highlights social and market patterns that push actors towards supranational institution building (Haas Reference Haas1961; Sweet and Sandholtz Reference Sweet and Sandholtz1997). Once a supranational institution was born, a new dynamic emerges, creating new social expectations and behaviour. This theory views pro-integration actions and the growing density of supranational governance arrangements as reducing the capacities of member states to control the outcomes. The causal path is characterised by path dependence, highlighting how the timing and sequence of prior integration narrow the range of policy options and practically lead to further integration, creating an upward trend of integration over time (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2019).

The first hypothesis tests for the extent that functional spillovers from previous integration attempts explain the nature of the new EU cybersecurity certification regime. Functional spillover mechanisms from earlier EU harmonisation attempts are relevant for examination here since they are hypothesised to motivate private and public stakeholders who advocated for a European cybersecurity framework due to regulatory burdens and the lack of mutually recognised certification standards across member states. For instance, to certify smart meters, manufacturers will have to pay 1 million Euros to operate in Germany, but only 150 k Euros to operate in France and the UK (EU Commission Impact Assessment Part 4 2017). This creates heavy burdens on industry actors and impedes trade among member states, undermining previous integration attempts to liberalise trade and harmonise market rules as part of the creation of the European Single Market.

Moreover, the national fragmentation of cybersecurity certification is expected to challenge previous integration attempts specifically in the field of cybersecurity, which aimed to create an “effective cybersecurity culture among member states” (Christou Reference Christou2019) and a minimum baseline for cybersecurity in Europe. The security of products has become an important component of cyber resiliency, but the current process of certifying for security does not fit the dynamic threat landscape. Certification processes are long, expensive and not suitable for the life cycle of digital products. The integration of cybersecurity certification is hypothesised to make this more effective, complementing previous cybersecurity integration goals by creating a solid baseline for cybersecurity across member states.

H1: The design of the EU cybersecurity certification regime can be explained by functional spillovers from previous single market and cybersecurity integration efforts. An efficient policy regime vis-a-vis previous functional problems is expected.

The second hypothesis is derived from neofunctionalism as well but highlights a different causal mechanism – cultivated spillover dynamics of policy change. According to this mechanism, supranational actors cultivate integration for their own interests. This approach views Eurocrats as agents of further integration who push for a supranational agenda, despite member states’ reluctance (Niemann et al. Reference Niemann, Lefkofridi, Schmitter, Wiener, Börzel and Risse2019). Specifically, I expect the EU Commission’s supranational aspirations to become more influential in the cybersecurity policy space and drive a supranational agenda for regime design. The literature on EU cybersecurity governance reveals that even though most competencies in this policy arena remained in the hands of member states, the EU has been increasingly active over the years and clearly stated its ambition to play a central role in developing the regulatory framework for cybersecurity (Wessel Reference Wessel, Tsagourias and Buchan2015). Since cybersecurity is absent from EU treaties, the Commission has been in continuous conflict with member states, trying to increase its mandate to govern cybersecurity by linking cyber-related policies to existing EU competences. Recently, the EU has been endeavouring to make provisions for cybersecurity in the fields of national defense and security, threatening the exclusive mandate of member states further (Odermatt Reference Odermatt, Blockmans and Koutrakos2018). In the certification case, national fragmentation in existing policies and the legal EU basis to ensure the functionality of the single market lend legitimacy to EU attempts to forge a European Cybersecurity Certification Framework, regardless of the opposition of member states.

As an international government organisation, the EU is significantly constrained by member states. But through the promotion of a supranational certification regime, the EU can theoretically bypass member states and govern targets beyond its jurisdiction without states’ intermediation (e.g. Abbott et al. Reference Abbott, Genschel, Snidal, Zangl, Abbott, Genschel, Snidal and Zangl2015, Reference Abbott, Genschel, Snidal and Zangl2019). Evidence shows that this had happened before. Through the EU’s New Approach, which harmonises technical standards in Europe, the EU has been trying to bypass national authorities (Borraz Reference Borraz2007), perceiving standards as instruments of supranational governance that offer the opportunity to reduce the influence of national interests and quicken the pace towards the achievement of a single market (Brunsson and Jacobsson Reference Brunsson and Jacobsson2000).

H2: The design of the EU cybersecurity certification regime can be explained by cultivated spillovers by the EU Commission to increase its influence in the cybersecurity policy space and create a policy regime with significant decision-making authorities for EU institutions.

The third hypothesis is derived from the liberal intergovernmentalism theory of EU integration. This theory argues that EU integration results from states searching for beneficial bargains (Moravcsik Reference Moravcsik1998). Supranational institutions, according to this theory, are designed by states and are kept under their control. The theory describes member states as the “masters” of EU treaties. Post-integration, the theory argues, states continue and enjoy decision-making powers, similar to pre-integration periods. The role of EU institutions is mainly for mediating between interest groups and acting as reactive agents to member states’ instrumental policymaking practices. The mechanism in play is described as rising interdependence between member states that leads to national policy formulation and intergovernmental bargaining that then creates supranational or intergovernmental arrangements to secure states’ interests (Moravcsik and Schimmelfennig Reference Moravcsik, Schimmelfennig, Wiener, Börzel and Risse2019).

I expect powerful states in the cybersecurity certification arena – Germany, France, and the UK – to take advantage of this integration attempt and seek a policy regime that stabilises and further legitimises their central role in the certification space. These nations are heavily invested in national certification frameworks and enjoy an influential voice in EU policymaking. The literature on EU cybersecurity governance confirms the willingness of member states to further anchor their influence in this policy arena. In negotiations over the NIS Directive, powerful member states created a clear border for EU intervention, further legitimising national, rather than supranational influence on cybersecurity governance (Christou Reference Christou2016; Bendiek et al. Reference Bendiek, Bossong and Schulze2017). For instance, the influential voice of Germany was able to push back provisions that required mandatory security practices from national public administration agencies. Thus, I expect a certification regime that will provide national control through either intergovernmental or supranational arrangements.

H3: The design of the EU cybersecurity certification regime can be explained by intergovernmental bargaining that leads to an increased influence of powerful states on the designed certification regime.

Analytical framework and methodology: labeling and explaining post-integration policy design for EU cybersecurity certification

In order to trace and explain how EU integration developed in a policy field that sits between market and state sovereignty issues, I conducted an in-depth case study analysis of the EU cybersecurity certification regime. This case was selected since it demonstrates market creation for certified products at the EU level as well as the integration of practices that are closely related to the state’s sovereignty, attempting to diverge, for the first time, from national decision-making over cybersecurity in Europe.

To trace the development of the EU cybersecurity certification regime I analysed cybersecurity certification in Europe between the years of 1997 to 2019. I chose the year of 1997 as my starting point since this is the first time in which cybersecurity certification was addressed at the extra-national level through the Senior Officials Group Information Security (SOG-IS) agreement. I completed my data collection with the 2019 Cybersecurity Act (CSA) that created a new framework for EU cybersecurity certification.

For my analytical framework, I adopted Börzel’s (Reference Börzel, Wiener, Börzel and Risse2019) conceptualisation of the EU as a political system that combines different varieties of governance. I offer a framework for political and policy analysis based on the notion of “policy regimes” (e.g. Hood et al., Reference Hood, Rothstein and Baldwin2001; May and Jochim Reference May and Jochim2013) to capture and label policymaking outcomes based on their national, intergovernmental or supranational character (e.g. Levi-Faur Reference Levi-Faur1999a).

I labelled policy arrangements as “national” when the different certification regime components – standardisation, accreditation, certification and evaluation – are exclusively conducted or controlled by national authorities and remain relevant only within their borders. I labelled policy arrangements as “intergovernmental” when common agreements across nations allow mutual recognition of nationally oriented governance arrangements. Finally, I labelled policy arrangements as “supranational” when common standards are created and facilitated by supranational institutions.

It is important to distinguish between intergovernmental and supranational forms of Europeanisation. The distinction is based on the degree of transfer of control to extra-national institutions and arrangements. Both intergovernmental and supranational policy regimes involve such upward transfer of control, but while the former has specific provisions that provide room for autonomy and control by national actors, the latter allows less national discretion (e.g. Levi-Faur Reference Levi-Faur1999b).

This analytical framework does not hold much explanatory power of its own and has to draw on EU integration theories to explain how and why specific policy outcomes came about. Different regime components may be labelled differently, and based on EU integration theories, we can better assess who were the influential actors and what were the drivers for creating a certain certification regime at the European level.

In terms of data collection, the policy regime approach enables a backward mapping of governing arrangements for a given policy problem, while shedding light on the link between politics of the policy process and policy outcomes (May and Jochim Reference May and Jochim2013). It considers institutional structures, rules and actors that are associated with governing specific problems (Hood et al. Reference Hood, Rothstein and Baldwin2001) and helps to illuminate the multiple dimensions of how a given problem is addressed over time. Adopting the policy regime lens thus allows to cope with a fragmented and disjointed certification field, which takes place in multiple levels of governance, across different actors and practices.

I collected 41 relevant policy documents and reports: 17 policy documents from EU institutions (see Appendix Table A.1), 16 position papers from 22 private organisations and associations engaged in the policy process (see Appendix Table A.2), and eight ENISA reports (see Appendix Table A.3) that are related to cybersecurity certification. I also interviewed 18 stakeholders from different types of organisations that span across – The EU Commission, Parliament, and Council, ENISA, national certification agencies, private certification bodies, private evaluation laboratories, product manufacturers, digital service providers and industry associations (see Appendix Table A.4). Each interview lasted 50 minutes on average, during which I asked for insights about the current and prospective EU certification regimes, the interests of the different actors, the pressure exercised on policymakers, and bargaining conducted during the negotiation processes. This wide range of data sources allowed to tackle the risk of incorporating potential bias in my evidence.

To answer the first research question on how the cybersecurity certification regime has been integrated, I conducted a longitudinal qualitative analysis to trace how the institutional frameworks designed by EU, member states, and private certifiers for cybersecurity have changed in the past 22 years, up until the emergence of the newly designed certification framework at the EU level. I labelled each regime component as supranational, intergovernmental, or national and traced how it changed over time.

To answer the second research question and explaining why the new integrated policy regime was designed in ways that only marginally diverge from the existing regime, I conducted a process-tracing analysis to test for the three research hypotheses. I tested whether (1) functional considerations from previous integration attempts, (2) the Commission’s impact and involvement in the process, and (3) the influence of strong member states had initiated causal mechanisms for the observed regime design, focusing on sequential processes in the EU legislative process of the recently approved CSA.

To assess the stream of evidence per each of the three expected causal mechanisms, I relied on Van Evera’s (Reference Van Evera1997) framework and classified pieces of evidence as certain, unique or both with regard to the hypothesised causal mechanism. According to this classification of evidence, I stated my degree of confidence in each hypothesised mechanism (e.g. Beach Reference Beach2016).

To measure the impact of functional considerations from previous integration attempts on the emerging regime, I looked for indicators that reveal how the primary goal of the integration was the functioning of the single market and how previous integration measures for cybersecurity resulted in a need for further integration in cybersecurity certification. Specifically, I searched for evidence that indicated a causal mechanism that started with functional problems from previous integration attempts and then created pressure on policymakers to integrate the certification domain, but only in a limited fashion, for functional purposes.

To measure the impact of the EU Commission on the initiation and design of the integrated regime, I looked for indicators that had shown how the Commission was willing to compromise on rather limited changes in control arrangements, as long as some sort of Europeanisation took place. I searched for evidence for a causal mechanism that started with the Commission acting as a policy entrepreneur, stating its willingness to push for further integration despite the reluctance of member states. Then the newly designed regime assigns new roles to supranational bodies that become part of the cybersecurity certification regime, even under limited conditions.

To measure the influence of strong member states on the observed policy outcomes, I looked for evidence for a causal mechanism that started with statements from government leaders that express integration as a solution, and continued with member states that enjoy significant certification capacities – Germany, France and the UK – leading national opposition and designing a rather limited European regime to legitimise their role, in ways that their benefits from integration are larger than the costs.

Empirical analysis: the development of the EU cybersecurity certification regime (1997–2019)

Certification as a tool of governance refers to “regulation through authorization” and addresses giving a quality assurance based on a successful evaluation process conducted according to standards-based certification schemes (Frieberg Reference Freiberg2017). The focus of this article is on the integration of cybersecurity certification for products. Such certification involves the evaluation of security based on products’ technical designs and communication interfaces.

The institutional framework for certification contains four types of mutually reinforcing independent actors: (1) standardisation bodies that set the requirements to produce certification schemes. These schemes include the methods and principles for the issuance of certificates. (2) Certification bodies that certify products/services according to evaluation processes conducted by (3) independent laboratories and based on certification schemes. The evaluation process is the assessment of the product, while the certification process oversees the evaluation and ends with the actual certificate. The fourth type of actors in the institution of certification is (4) accreditation bodies that verify the quality and monitor the operation of certifiers.

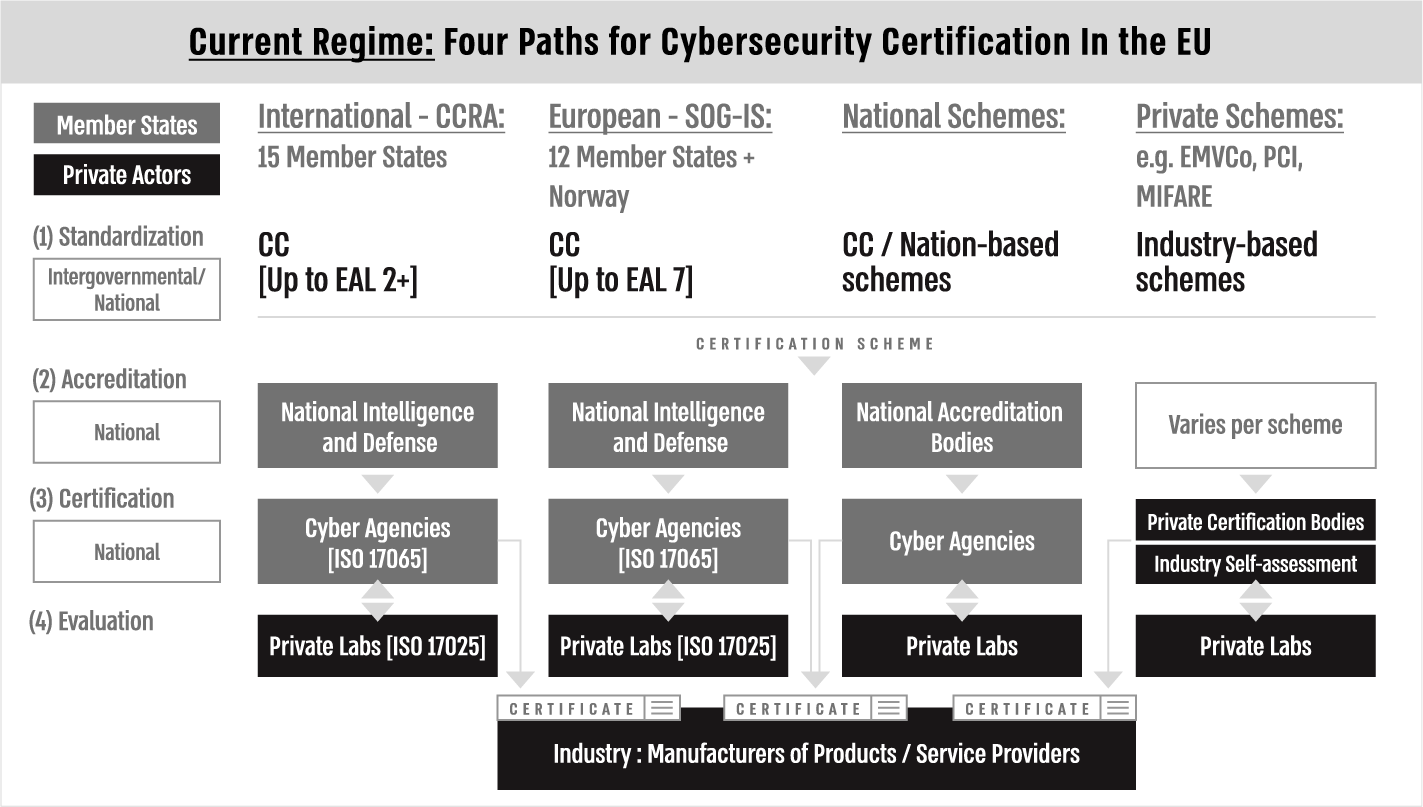

Current regime

These four components come together through intergovernmental, national and private arrangements in the current patchy terrain of cybersecurity certification in the EU. Certificates are issued through four distinct paths that are differently recognised at the international, European, national and industry levels. Each certification path demonstrates the dominant position of national authorities in the certification process.

First, internationally recognised certificates are provided based on the international Common Criteria (CC) standards, featuring one of seven possible hierarchical Evaluation Assurance Levels (EAL). The international community had embraced the CC standardisation through the Common Criteria Recognition Agreement (CCRA) whereby signers have agreed to accept the results of CC evaluations performed by other CCRA members. Currently, 15 member states are part of the agreement. The object of CCRA is to enable a context where products and protection profiles that earned a CC certificate can be procured or used among all participating states without the need for further evaluation.

The requirements of CC standards are developed by an international consortium known as the Common Criteria Development Board and Common Criteria Maintenance Board. These are management committees consisting of senior representatives from each signatory country of the CCRA, which was established to implement the arrangement and provide guidance to the respective national bodies, including on evaluation and validation activities. The public certification body in each member state is responsible for overseeing evaluation laboratories, whereas national intelligence and defense agencies accredit public certification bodies. Officially, only evaluations up to EAL 2+ are mutually recognised.

While standardisation is happening through international arrangements, national actors control the whole process through accreditation and certification by national defense and cyber agencies. They audit and license private evaluation bodies, which includes the monitoring of the personnel, facilities and evaluation processes in labs on a yearly and per-project basis. In case of noncompliance, the national certification body can revoke the license of the lab.

The second certification path in the current regime is a European path, established by the 1997 mutual recognition agreement between 12 member states + Norway regarding CC certificates, also known as the Seniors Officials Group on Information Systems Security (SOG-IS) agreement. It is currently the main certification mechanism at the European level and was produced in response to EU Council Decision from 1992 (92/242/EEC) and a subsequent Council recommendation from 1995 (1995/144/EC) on common information technology security evaluation criteria.

The purpose of SOG-IS is to coordinate the standardisation of CC and certification policies among public certification bodies in each participating state. Each party to the agreement recognises evaluations done up to EAL 7, by a limited number of nations that are defined as “certificate issuing parties.” Another goal was to coordinate the development of certification schemes to comply with legal requirements at the EU level. Still, the scope of mutual recognition is limited to product types that involve digital signatures, digital tachographs and smart cards. National authorities wanted to limit the high levels of recognition of CC standards to specific technical domains, where adequate agreements around evaluation methodology and laboratory requirements have been in place.

Similar to observed interactions under the international path for certification, national actors remain in control throughout this process as well. They agree on standards through intergovernmental agreements and control accreditation, certification and evaluation practices. Private evaluation labs are heavily monitored by public certification bodies and can be blocked from being licensed in multiple countries. Certification bodies accredited by national intelligence and defense agencies have to ensure that all laboratories follow SOG-IS criteria in addition to CCRA requirements.

A third path for certification in the EU is national. Public certification bodies provide nationally recognised certificates in several Member States – Germany, France, the UK, Spain and the Netherlands – for two purposes: (1) they set high-level cybersecurity requirements for national security in components of state’s infrastructures under CC standards and (2) create efficient alternatives to CC for low assurance levels. With the lack of mutual recognition agreements, these certificates are recognised only within national boundaries. Unlike previous certification paths, national authorities not only control accreditation, certification, and evaluation but also exclusively set the standards for certification.

The Commercial Product Assurance scheme in the UK is an example of a national scheme that provides low assurance levels. The scheme is open for application to all vendors with a UK sales base and has no mutual recognition agreement. The national accreditation body in the UK accredits Commercial Evaluation Facilities (CLEFs) as testing laboratories based on ISO 17025. UK’s national cyber agency authorises CLEFs, keeping their operations under review.

France and Germany hold distinguished national certification capacities as well. The French certification scheme – Certification Securitaire de Premier Niveau– was established by the National Cybersecurity Agency of France in 2008. The German certification schemes are facilitated by the Federal Office for Information Security (BSI), defining national security requirements in the evaluations of critical components. Emerging national certification initiatives are also developing in Italy, Sweden, Norway, the Czech Republic, Ireland, and Poland (EU Commission Impact Assessment Part 6 2017).

Still, not all member states hold public certification capacities and expertise. This creates different bargaining positions across states over new certification frameworks at the EU level.

The fourth path for certification is completely private, where private actors drive standardisation, accreditation, certification and evaluation. Industry associations adopt certain standards and deploy certification schemes that are recognised within industrial sectors. Product manufacturers apply for certificates through private certification bodies that work with private laboratories. The need for accreditation varies according to the private scheme. Examples of such schemes include the ISASecure certification programme in the industrial automation sector, the EMVCo and the Payment Card Industry schemes, and the MIKRON FARE Collection (MIFARE) scheme by NXP Semiconductors for ticketing solutions. Most cybersecurity certification in the market is currently based on this private path. Product manufacturers are reluctant to adopt the slow and complex certification processes provided by the previously described public paths (Interview with an EU Commission policymaker 2019).

To summarise, current paths for certification in the EU are either dominated by national control points or operated based on market powers through private actors. Standard setting in public certification paths is intergovernmental or national, while accreditation and certification are happening exclusively at the national level. Evaluation is conducted by private laboratories under strict national control, with private labs that can even be banned from licensing with multiple national authorities.

Figure 1 illustrates the four paths for cybersecurity certification in the EU before the recently agreed CSA, with assigned labels for each regime component.

Figure 1. Current regime – cybersecurity certification paths in the EU.

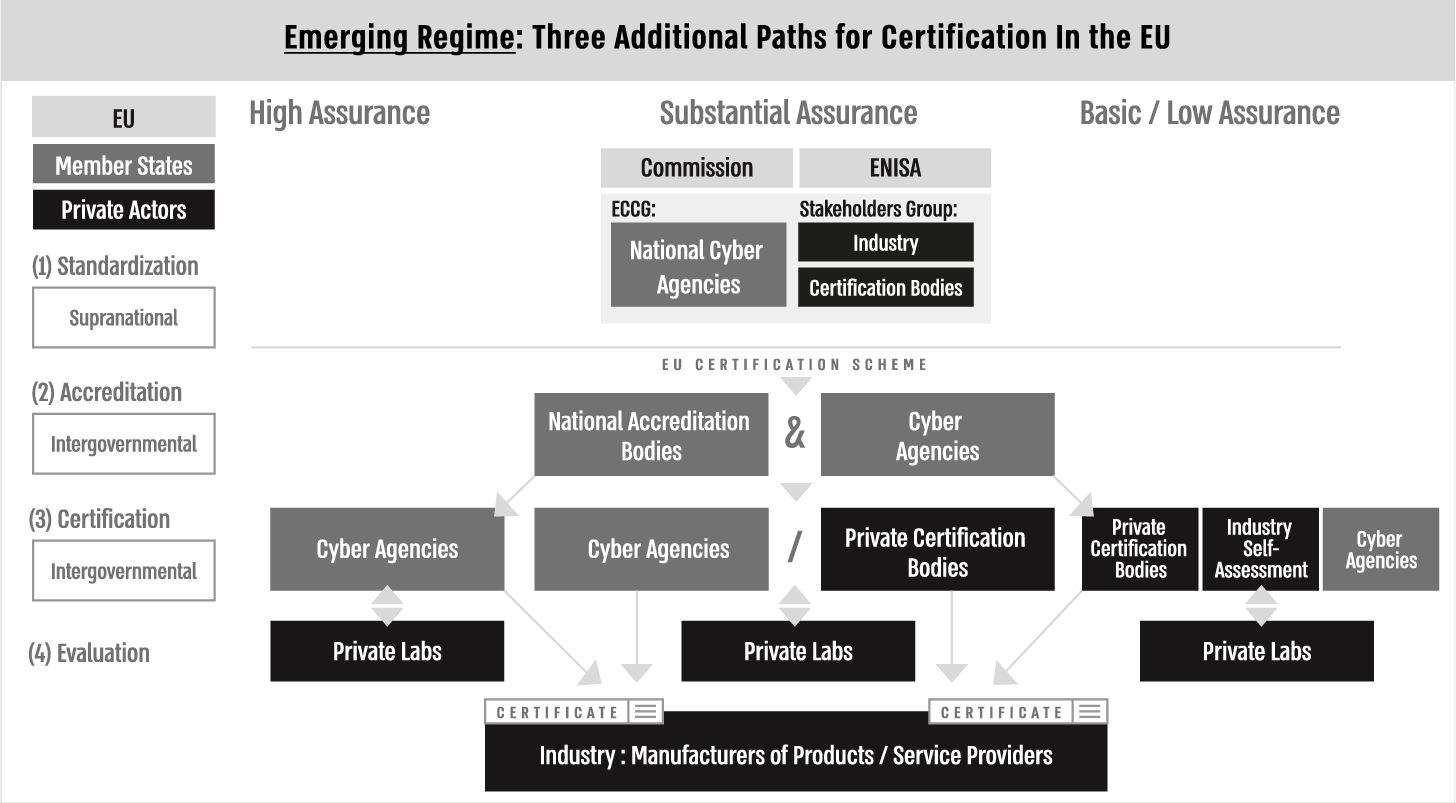

Emerging regime

The paragraphs below render an account of the creation of three new paths for EU certification, delineating the extent of transfer of control from national to extra-national actors in the proposed certification framework.

In September 2017, the Commission proposed the CSA, a regulation that strengthens the mandate of ENISA and establishes a new EU Cybersecurity Certification Framework at the same time. The trialogue negotiations successfully ended in December 2018, and the EU Parliament had voted to adopt the Act on March 12, 2019, creating a new EU cybersecurity certification regime.

Through the CSA, three new European certification paths for basic/low, medium, and high levels of security assurance were generated, aiming to change national decision-making mechanisms over certification and upgrading the role of private certification bodies to certify on behalf of the EU. The addition of private certification bodies to the policy regime ensued from reasons of scale and resources. Since these bodies already enjoy capacities to certify, they can cope with the expected surge in the demand for certificates and fulfil gaps for member states with no certification capacities (Interview with EU Commission policymaker 2019). In addition, the act created new national veto points over the “European” certification process through accreditation, monitoring and enforcement mechanisms. Each certification body has to register with a national authority, and its status can be revoked in cases of noncompliance with national accreditation and regulatory requirements.

Certificates issued at the security assurance level of basic/low are defined as providing a limited degree of confidence. Evaluation should include a review of the technical documents of the product. For this assurance level, CSA opens the possibility of a conformity self-assessment by industry actors in addition to third-party assessment. The first-party certification process permits manufacturers to voluntarily issue a statement of conformity to requirements laid down in the scheme. They assume responsibility for the compliance of their products and carry all evaluation checks by themselves.

Certificates issued at the security assurance level of substantial are defined as providing a higher degree of confidence. Verification of the security functionalities with the product’s technical documentation informs the evaluation. Both public and private certification bodies are allowed to issue certificates at this level. This path enables private certification bodies to work with market actors from several member states and produce EU-recognised certificates without the need to go through lengthy processes of the SOG-IS or CCRA mechanisms. Evaluation is done in private labs, and accreditation is conducted through a joint effort by national cyber agencies and accreditation bodies.

Certificates issued at a high level of security assurance are defined by the Act as providing the highest degree of confidence. The evaluation is guided by efficiency testing that assesses the resistance of the security functionalities of tested objects against high-level cyber attacks. Only national certification bodies are allowed to issue certificates at this level.

Newly created governance frameworks that apply to all assurance levels support these emergent certification paths and enable national control points over each and every regime component. These frameworks address the (1) standard-setting process of developing European certification schemes, (2) accreditation of private certification bodies and (3) the monitoring and enforcement practices over certification bodies and certified products. These frameworks transfer the control over the certification process from national to extra-national arrangements, at the intergovernmental and supranational levels, but only on a case-by-case basis, based on the discretion of national cyber authorities in every member state.

Limited supranational standardisation

The CSA defines a new framework of rules governing the adoption of European certification schemes pertaining to cybersecurity. The governance processes involve multiple stakeholders from the EU, member states, industry and certification bodies to decide upon new schemes to embrace. When a need for a certification scheme is identified, the Commission will ask ENISA to prepare a scheme for specific services/products. Member states and stakeholder groups may also propose to the Commission a scheme to deploy. Stakeholders come together and influence the process through two different groups – (1) the EU Cybersecurity Coordination Groups (ECCG), headed by the Commission and ENISA, which comprises heads of national cyber agencies, and the (2) Stakeholder Cybersecurity Certification Group that includes businesses, digital service providers, consumer organisations, and standardisation, accreditation, and certification bodies. The schemes detail the specification of cybersecurity evaluation requirements including the level of assurance they provide, methods to evaluate, rules for surveillance and compliance, and consequences for noncompliance. Once a need for a scheme is identified, the request is submitted via the Commission and/or ECCG to ENISA, which works with all stakeholders for transparently drawing the scheme. Thus, through the development and deployment of certification schemes, the EU and stakeholders set the regulatory framework for certification bodies, including monitoring requirements and sanctions for noncompliance.

I labelled this new standardisation process as “limited supranational” since on the one hand, it produces common standards – an EU certification scheme – and is facilitated by EU institutions, the Commission and ENISA, that hold veto powers on which scheme to develop in the first place. On the other hand, national discretion is allowed throughout the process, and member states can prevent the adoption of a new certification scheme or declare a certification case as a “national security issue” that should be dealt with under the sole discretion of national authorities.

Intergovernmental accreditation

Accreditation in the new EU framework is designed as a joint effort of different national agencies and is recognised across member states. National accreditation bodies, which operate according to regulation EC 765/2008, and national cyber agencies, which usually have the expertise in the field, come together to assess the quality and ensure the capacities of certification bodies. For each EU scheme, national authorities ought to notify the Commission of the accredited certification bodies that are allowed to certify. In cases of noncompliance, national authorities can restrict, suspend or withdraw existing authorisations of private certification bodies.

The Act creates a new intergovernmental monitoring mechanism – the “peer-review” arrangement. This arrangement allows national authorities to cooperate by sharing information on possible noncompliance of labs or certification bodies with the schemes. The new mechanism serves two purposes – it increases the control of national authorities over private certification bodies and ensures equivalent standards and practices throughout the Union to prevent a race-to-the-bottom in the quality of issued certificates. Information sharing covers the procedures for supervising the compliance of products, services, and processes with certificates, and verifies the appropriateness of the expertise of the personnel in certification bodies.

I labelled this accreditation arrangement as “intergovernmental” since it is a mutually recognised practice across member states, conducted by national agencies, and with significant discretion to national actors. Nation-states enjoy veto powers and control points over the process, promoting it through intergovernmental information sharing mechanisms to ensure proper accreditation for recognised certification bodies across the Union.

Intergovernmental certification

Certification according to CSA takes place by public and private actors, and for the first time, becomes recognised across member states, with strict veto points for national authorities. The CSA forges a new framework for monitoring and enforcing the compliance of certification bodies and certified products in the post-certification process. The compliance of certified products is going to be tested through information gathering based on current Market Surveillance Authorities in member states, as defined in EC 765/2008. These are periodic checks on certified products to ensure that the certification is still valid. In addition, the operation of private certification bodies is designed with comprehensive monitoring frameworks by national actors. National cyber agencies can revoke noncompliant certificates and withdraw certification bodies from the list of authorised entities. National cyber agencies are also authorised to supervise private certification bodies, conduct investigations, impose penalties, and handle complaints regarding their operation. They are empowered to request information from certification bodies on their performance and compliance practices and obtain access to any premises of the certification body or certificate holders.

I labelled this certification arrangement as “intergovernmental” since certification becomes mutually recognised across member states, with significant discretion and control points to national actors using new and existing monitoring capacities.

Figure 2 illustrates the three new additional paths for cybersecurity certification in the EU, assigning a label for each regime component.

Figure 2. Emerging regime – newly designed cybersecurity certification paths in the EU.

Hypotheses testing: explaining a case of limited Europeanisation

In this section, I explain the rather limited Europeanisation of the cybersecurity certification regime. We witness how standardisation moves from a national/intergovernmental process in the current regime to a supranational process in the emerging regime, but with significant veto points to national authorities that question the supranational nature of the standardisation process. In existent certification paths, standards are set through either intergovernmental negotiations (In CC and SOG-IS arrangements) or exclusively by national authorities. In the emerging regime, common European certification schemes are produced for the first time in a process that is facilitated by EU institutions but is in fact under full control by the same national authorities.

The second regime component of accreditation of certification bodies becomes intergovernmental instead of exclusively national but is heavily controlled by the same national authorities. In existing public paths for certification, national defense and intelligence agencies accredit only state’s certification bodies and are relevant within national borders. In the emerging regime, accreditation is recognised across member states and operates through intergovernmental “peer-review” mechanisms but allows the same national authorities to control the whole process and prevent integration within their jurisdictions if they please.

Certification in the newly designed regime becomes intergovernmental as well, with the option of first-party certification to be conducted by private manufacturers. In existent public certification paths, certification takes place through national agencies. They are the only ones that hold the capacity to certify according to intergovernmental or national standards. Their certification processes are usually recognised within national boundaries, with a few exceptions for CC certifications. Private certifiers are currently operating based on industry association schemes and are recognised based on market practices. In the emerging regime, however, certifiers are recognised across the EU but are heavily controlled by national agencies.

Table 1 compares the nature of the different components in the current and emergent certification regimes over time. The limited nature of Europeanisation that takes place among each and every regime component is the dependent variable I aim to elaborate on below.

Table 1. Temporal variance in the Europeanised cybersecurity certification regime (1997–2019)

Hypothesis #1: neofunctionalism – functional spillovers from previous single market and cybersecurity integration attempts design a rather limited Europeanised regime

To examine the influence of functional spillover mechanisms on the rather limited European nature of the emerging cybersecurity certification regime, I searched for evidence that would support the following causal mechanism: functional problems that resulted from previous integration attempts created pressure and need to integrate the cybersecurity certification domain. This led to the design of a new regime that aims to solve observed functional problems by only slightly diverging from control arrangements in the current regime.

I analysed position papers, policy documents and interviews with key stakeholders to capture the extent to which functional considerations from previous integration efforts drove the design of the new regime.

A few pieces of evidence were found to be necessary but not sufficient to testify on the above casual mechanism (also known as “hoop tests” in Van Evera Reference Van Evera1997). They demonstrate functional considerations in promoting the new policy option. In the agreed policy text, it is clearly stated that the new certification framework aims to solve the lack of trust in the digital single market. The problem with the current paths for certification is framed by the Commission as the lack of cooperation among member states. This created nationally separate testing and evaluation procedures in ways that might protect indigenous industries and increase the regulatory burden for manufacturers that have to be certified in several states. This fragmentation is framed as a problem for the European Single Market, and the goal of the new certification framework is to “improve the conditions for the functioning of the internal market…creating a digital single market for products, services, and processes” (EU Commission, CSA, p. 77). This is also evident in a Parliament amendment that was added to the policy text in the negotiation process and recognised how manufacturers face increased costs due to fragmentation and why mutual recognition among national certification bodies should be promoted. And indeed, according to an ENISA representative, “Industry and private certification bodies pressured national policymakers to agree on the harmonized certification framework. They used the current fragmentation and consequent regulatory burden to push their public officials to agree on CSA” (Interview from February 20th, 2019).

Efforts to integrate cybersecurity certification were driven not only by single market problems but also from functional issues with prior cybersecurity integration efforts. Those attempts, mainly the NIS Directive, are perceived as contributing to a high level of cybersecurity in the single market. Current certification paths, however, undermine these efforts. The existent process of certification is perceived by stakeholders as long, expensive, and not suitable to the dynamic lifecycle of high-tech products (EU Commission Impact Assessment Part 4 2017). Cybersecurity “has the potential to drive the Union’s economic growth” and serves as “the backbone to achieve the digital single market” (EU Commission, CSA, p. 2). Specifically, policymakers stated how regulated sectors in the NIS directive are “also sectors in which cybersecurity certification is critical” (EU Commission, CSA, p. 20) and the current certification process, according to this perspective, should be improved.

Two pieces of evidence passed a “straw in the wind” test, as they are weak or circumstance evidence (not certain nor unique for the hypothesised causal mechanism according to Van Evera Reference Van Evera1997), but can slightly increase our confidence on what drove the Commission to act in this space. In a 2016 Commission’s Communication, the Commission outlined the need for high-quality, affordable and interoperable cybersecurity products and solutions that the current certification paths were unable to offer. As such, and to ensure the quality of produced certificates, a framework should “be established in a uniform manner in all member states in order to prevent certification shopping based on differences in levels of stringency between the Member States” (EU Commission, CSA, p. 22). Even prior to the recent Act, in a Mid-Term Review on the implementation of the Digital Single Market Strategy, the Commission highlighted the need for safe connected products and systems, and indicated that “the creation of a European cybersecurity certification framework could both preserve trust in the internet and tackle the current fragmentation of the cybersecurity market” (EU Commission Communication, May 2017, p. 13).

Significantly, a few pieces of evidence passed a “smoking gun” test, as they are unique but not certain. Passing such a test strongly affirms the hypothesis but is not necessary (Van Evera Reference Van Evera1997). For instance, according to an ENISA representative who was deeply involved in the policy process: “current fragmentation in the market was used to put pressure on public officials…industry and private certifiers (have) pressured national policymakers to agree on the harmonized framework.” Moreover, the intergovernmental accreditation arrangement ensures equivalent standards and practices throughout the Union to prevent a race-to-the-bottom in the quality of issued certificates in different states. Manufacturers might choose to get certified by certifiers that are less rigorous than others, but through an intergovernmental accreditation process, EU policymakers aim to prevent an overall decrease in the quality of certificates provided in the Union, ensuring certain levels of cybersecurity protections across the Union (Interview with an EU Commission representative, March 6, 2019). Another significant piece of evidence is the fact that intergovernmental certification ensures mutually recognised certificates across member states and decreases regulatory burden and trade barriers in the current market for certified products. The reliance on private rather than only public certifiers allows creating a certification capacity across the Union, providing an easier certification process for manufacturers in different states. In addition, the “liberal” mode of certification by first-party manufacturers, which was promoted by the Parliament and Council, allows an efficient certification process for low assurance levels and stimulates the use of EU certificates by manufacturers to signal certain trust levels and advance trade and security further. This decreases market fragmentation issues and incentivises cross-national trade within the Union.

Ultimately, functional spillovers are useful for explaining not only why integration attempts were initiated in the first place, but also how certain aspects of regime design aim to respond to functional problems in previous integration efforts. Singe market issues and the inconsistent levels of cybersecurity across the Union pushed decision-makers to adopt functional solutions for the new certification regime that are reflected in the chosen accreditation and certification arrangements. Still, the evidence does not show why these functional problems are better served by a rather limited Europeanised certification regime. A supranational/intergovernmental regime that is not heavily controlled by national authorities would have served the same purposes even better. Reducing the regulatory burden on market actors, decreasing national fragmentation, and ensuring the quality while increasing the efficiency of the certification process are all better addressed by a harmonised rather than nationally controlled policy regime. We now better understand why national authorities wanted to control the accreditation process (to ensure the quality of certificates produced), or why private certifiers were elevated (to ensure the capacity of member states to certify in a common fashion), but still puzzled about why member states incorporated significant veto points throughout the finalised policy text in ways that allow them to prevent the deployment of an EU scheme and maintain their control over every component in the cybersecurity certification process. Moreover, the fact that previous certification paths are still valid provides avenues for the traditional, complex, and nationally oriented certification processes to remain relevant.

This is all counter-intuitive to the functional problems in the current certification regime, highlighted following previous integration attempts, that the new regime aimed to solve. While some of the functional problems were addressed by the design of the emerging regime, functional spillover dynamics are not sensitive enough to the particular regime design decisions in this case.

Hypothesis #2: neofunctionalism – cultivated spillover dynamics by the EU commission settle on a rather limited Europeanised regime to secure long-term interests

To examine how and to what extent the EU Commission’s supranational aspirations cultivated only a limited integration of cybersecurity certification in order to secure its long-term interests, I searched for evidence that would support the following casual mechanism: The EU Commission acted as a policy entrepreneur and chose to lead integration in this field. It then instrumentally approved some kind of integration, despite initial reluctance of member states, and compromised on designing a rather limited Europeanised regime to secure its long-term interests of increasing influence in this space.

Observable implications for this mechanism include initiatives by the Commission in this policy space, before any pressure from member states; evidence about the Commission acting as a change agent, to the best of its abilities, to approve any kind of integrated regime; flexibility in policy design decisions according to the interests of other stakeholders; and putting in place mechanisms that would increase the influence of the Commission in the long term.

I found that a few pieces of evidence passed a “hoop test” as they are necessary but not sufficient to increase our confidence in the causal mechanism above. Policy documents showed that unsurprisingly, and in line with the process of EU policymaking, the Commission was the “first-mover” to initiate and lead the agenda for a new European Cybersecurity Certification Framework, without any initial demand from member states. The need to develop a new framework was firstly recognised in a 2016 EU Commission Communication that identified the urgency of harmonising national evaluation practices and certification schemes. Consequently, in September 2017, coinciding with the Commission’s President State of the Union speech, the Commission proposed a new EU cybersecurity certification framework. The Directorate-General for Communications Networks, Content, and Technology held an entrepreneurial role in setting the agenda, defining the problems of trade liberalisation and overall quality of cybersecurity to be solved, and formulating the EU Cybersecurity Certification Framework as the solution to these problems. Eventually, despite initial reluctance by the influential states of France and Germany (French Senate 2017; Schabhuser Reference Schabhuser2017), the Commission was able to facilitate the creation of new certification paths, on top of the existing ones, but with significant veto points for member states.

Significantly, few pieces of evidence passed a “smoking gun” test, as they are unique and allow us to increase our confidence in the hypothesised causal mechanism. First, evidence on how eager the Commission was to pass CSA, at any cost, was found in the coupling of the new certification framework with the strengthening of ENISA under a single proposal for consideration by EU institutions. This coupling was not a coincidence. ENISA is a valuable agency for member states as it allows them to get assistance and support at a low cost, and such coupling created incentives for collective action by member states. According to an ENISA representative: “the agency (ENISA) is weak to stand up against member states, but can still support, assist, and advise them. Therefore, member states would not want to explain to their taxpayers why they did not agree to the strengthening of ENISA,” and by that, “The Commission wanted to increase its opportunity of success, so it moved in an area where member states did not agree before – certification, together with a popular proposal to strengthen ENISA. By putting two seemingly different things together, the Commission increased the chances that member states will accept everything as a package.” Another evidence that passed a “smoking gun” test was found in the initial consideration of policy options, in which the Commission chose the only policy option that elevated its long-term role in the cybersecurity policy space. All other options relied on existing frameworks, leaving the Commission with the same levels of influence as before. These options included the development of nonbinding EU cybersecurity standards, the turning of SOG-IS into a mandatory certification framework, and the use of EU’s New Legislative Framework for harmonising standards in the internal market. These options were rejected because they were perceived as either burdensome for market actors or unlikely to solve the current national fragmentation (EU Commission Impact Assessment Part 4 2017). Most importantly, none of them boosted the influence of EU institutions in the long run as the chosen policy option.

Indeed, throughout the negotiation process, and somewhat unsurprisingly, member states were able to increase their veto points and create a regime that only marginally diverges from the current practices of cybersecurity certification. But a few agreed arrangements in the new regime stand out as providing the Commission potential long-term benefits of increased influence in this policy space, to the extent that the Commission was willing to accept a rather limited Europeanised nature for the new regime, viewing the agreed policy as a first step towards reaching its broader supranational goals. For instance, in the new governance processes for developing new schemes, ENISA enjoys leading roles of facilitation and coordination, while the Commission is authorised to approve every scheme. This is a new supranational agenda for the standard-setting process of security certificates that powerful member states – UK and France – were reluctant to accept (UK Parliament 2018a; French Senate 2017). Consequently, an amendment by the Council vested standardisation authority to the ECCG group consisting of heads of national cyber agencies, to state the priorities of scheme development alongside the Commission. Still, the Commission was able to cast a central role to its institutions and is responsible for the operation of the whole process. Furthermore, CSA’s text specifically stipulates that national schemes will cease to apply once a similar EU certification scheme has been deployed. Member states are not allowed to introduce new schemes in case they are already covered by an approved EU one. This is likely to create a situation in which gradually, EU certificates will replace national ones. Even though the Act allows the continuation of national paths of certification, and provides member states with the authority to block the adoption of an EU certification scheme, the Commission was able to require national agencies to communicate their desire to develop a new scheme and get an approval from the Commission and the ECCG group to do so. This is quite an achievement for EU institutions.

Another substantial achievement for the Commission in the long run is the authorisation of private certification bodies to operate and be recognised across member states. Previous institutional arrangements blocked private actors from operating in several nations. In the emerging regime, however, private certifiers can voluntarily enlist themselves with any member state, creating a capacity for the Commission to indirectly govern industries in member states, even if no public cybersecurity certification authority is in place. Despite their intergovernmental nature, the new certification arrangements can potentially serve supranational interests in the long run.

Ultimately, evidence showed that we can increase our confidence in the hypothesised causal mechanism. The Commission was acting instrumentally to create and then approve a Europeanised certification regime, despite initial reluctance of member states, using political tactics that go beyond its traditional role in the EU policymaking process. A closer look at the regime arrangements reveals that the design of a regime that only marginally diverges from the current regime served the Commission’s long-term interests. The newly designed supranational process of standardisation, along with new mutually recognised accreditation and certification arrangements, can potentially boost the Commission’s influence on this policy space in the long run and provide a central role to supranational institutions despite significant veto points of member states. In particular, ENISA would support the new regime by ensuring administrative maintenance and technical management of the European certification framework. According to a senior ENISA representative: “The main novelty of the CSA is the fact that the EU is taking responsibility over cybersecurity certification schemes and implements them in a European fashion” (Interview from February 20th, 2019). This is a tremendous success for the Commission, given the proven record of EU policymaking in the cybersecurity policy space up to this point. While the new regime also includes critical veto points for member states throughout the designed certification process, long-term political goals of the Commission are potentially served and explain why a compromise on a limited Europeanised regime was reached.

Hypothesis #3: liberal intergovernmentalism – intergovernmental bargaining and the influence of powerful states designed a limited Europeanised regime to maintain states’ influence

To examine how bargaining by powerful states impacted the design of a limited Europeanised regime, I searched for evidence that would support the following causal mechanism: Powerful states dominated national opposition to the integration proposal and were able to significantly change regime arrangements during the negotiation process. As a result, they chose to design a regime with significant national control points, in ways that only slightly diverge from the current regime, and in order to legitimise their already influential position in the cybersecurity certification space.

Observable implications for this mechanism include statements from government leaders of powerful states that view integration as a solution, evidence for how benefits from integration are greater than costs for member states, and incorporation of features in the agreed policy text according to states’ will and benefits, keeping supranational and intergovernmental regime components under strict national control, to create only a marginal change in the current regime.

The “powerful” member states in the policy negotiations were the ones that usually enjoy dominant positions in EU policymaking – Germany, France and the UK. They are also the ones that enjoy significant certification capacities. Early on, these states had expressed concerns of any integration attempt that does not rely on their capacities and therefore danger their dominant position in this policy space. They provided the most significant opposition to the Commission’s policy initiative and aimed to craft a policy design that fits their interests.

Policy documents and interviews do not indicate significant bargaining between member states, but rather an opposition to certain aspects in the Commission’s proposal by national parliaments and EU Council representatives, that goes along with the concerns of the powerful states. Whereas the Commission argued that the vast majority of stakeholders across member states appear to welcome the creation of a new European cybersecurity certification framework (EU Commission Impact Assessment Part 4 2017), evidence from national parliaments showed otherwise.

A few pieces of evidence pass a “hoop test” (Van Evera Reference Van Evera1997), providing certain but not unique evidence for the hypothesised causal mechanism. This includes policy documents and interviews with key stakeholders that reveal the willingness of powerful states to further legitimise their central role in the cybersecurity certification ecosystem by limiting significant changes to current practices. The UK was concerned that new certification schemes would override its “Secure by Design” initiative and made it clear that it will challenge any proposal that seeks to create EU-only standards and allow certification by EU-controlled bodies (UK Parliament 2018b). The French argued that the new certification framework wrongly places ENISA at the heart of the certification process, while the agency has no proper expertise to facilitate such processes. France demanded that national authorities in charge of cybersecurity remain in power over certification processes and should not be limited to a consultative role (French Senate 2017). The German BSI argued that “proven certification schemes do exist on the national level already” and “excluding such national systems bears the risk that they could not be implemented effectively any longer.” Such an “infringement into matters of national security is not necessary and a European certification scheme could be supplemented by national measures” (Schabhuser Reference Schabhuser2017).

The interests of powerful states are shaped not only due to the capacities they already have in this field, but also since cybersecurity certification touches upon core national security issues that are close to states’ sovereignty. The promotion of these interests is evident by nations that do not necessarily enjoy significant certification capacities. For instance, according to the Romanian parliament – “cybersecurity is a matter of national sovereignty” (The Parliament of Romania Senate 2017). Also, the Czech Senate stated that “member states are primarily responsible for national security, including cybersecurity” (The Senate of the Parliament of the Czech Republic 2017). According to a senior ENISA official: “Cybersecurity, especially as a component of critical infrastructures and national assets protection, remains a national responsibility within EU treaties.”

Several pieces of evidence passed a “straw in the wind” test, as they are weak or circumstance evidence (not certain and not unique for the hypothesised causal mechanism according to Van Evera Reference Van Evera1997), but can slightly increase our confidence on the stand and interests of member states in this policy space. For instance, an evaluation lab owner had described how “national authorities care about security, not about business,” and this is where they diverge from the EU’s approach to cybersecurity. Subsequently, they would like “private certification bodies to be very controlled…and these bodies should worry about their levels of independence under the new Cybersecurity Act.” The interviewee perceived cybersecurity as “a sensitive topic,” for which national authorities are imposing their mandate and will over other actors. National scepticism to external actors is evident not only towards the EU but also within national boundaries. According to an EU Commission policymaker, “national cyber agencies do not trust national accreditation bodies to properly accredit private certifiers.”

Significantly, observations on how the policy proposal has changed during the trialogue negotiation process passed a “smoking gun” test, as they are unique for highlighting the extent of influence of member states on the design of the emerging policy regime. The coupling of cybersecurity with national sovereignty concerns is instrumentally used by powerful states to legitimise their already existing capacity in the field and promote their agenda of nationally controlled certification processes. Once the Commission had initiated a policy proposal and negotiations over policy design took place, the interests of powerful states turned into EU Council and Parliament amendments that had significantly impacted the chosen policy design. Therefore, member states promoted substantial changes during the legislative process and consequently enjoy significant national veto points and monitoring capacities over the proposed certification framework. According to a senior ENISA representative, “the power shift in the agreed text (after the negotiation process) is toward member states – they get to control the Commission in every step of the way, enjoy discretion to act as they please, and retain full operational capacities in the aftermath of the proposal in terms of accreditation and supervision over certification.”

Veto points for national authorities were injected throughout the newly designed certification regime components, bringing the emerging regime very close to the existing one. First, for the supranational standardisation process, a Council amendment allowed member states to block the production of EU certification schemes once they decide to declare a specific certification case as a “national security” issue, to be kept under their sovereignty. They could also vote against recommended EU schemes during the comitology process when the EU proposes new schemes to deploy. Member states were also able to include provisions to the development process of certification schemes. The Commission, which had been initially empowered to state annual priorities, lost that prerogative to the ECCG group consisting of member states’ representatives, after an amendment by the Council vested it with the authority to request and decide on new schemes.

Second, member states enjoy increasing control and monitoring capacities through the intergovernmental accreditation arrangement in the new regime. They have the authority to accredit and approve every certification body and revoke its accredited status if necessary. Moreover, several amendments by the Council incorporated some provisions meant to increase the capacity of monitoring through accreditation bodies and national agencies. This includes the authority of accreditation bodies to suspend and restrict certificate authorities, and the double-accreditation requirements – from both a national accreditation body and a national cyber agency. An additional change in the policy text permits significant national influence through the establishment of the “peer-review” mechanism by national representatives. This was jointly promoted by EU Parliament and Council and created a framework of information sharing between national agencies to ensure the quality of authorised certifiers, but most importantly, increase national control over public and private certification bodies.

Third, in terms of valid certification paths, national schemes have not been excluded, and based on an amendment by the Parliament, the SOG-IS arrangement still holds. Furthermore, a Council amendment suggested that national agencies can still issue national certificates that are valid only within their borders. This can happen in cases where an EU scheme is not provided, or when issues of national security arise.