11 ‘Two-dimensional’ symphonic forms: Schoenberg’s Chamber Symphony, before, and after

The century following the death of Beethoven was an era of extreme formal experimentation in the field of symphonic music. A major and constant concern for many composers was the integration of the separate movements of a multi-movement design by presenting them as an intrinsic whole rather than as a relatively random collection. This concern manifests itself in many ways, the most far-reaching of which doubtless is the phenomenon that I call ‘two-dimensional sonata form’: the combination of the three or four movements of a sonata form within an overarching single-movement sonata cycle. This chapter explores the use of this pattern of formal organisation in symphonic music of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In order to appreciate the significance of two-dimensional sonata form, it is necessary to review some of the other strategies composers have used to integrate the different movements of a multi-movement cycle. The most common of these can be grouped into three categories.

A first group involves thematic connections between otherwise separate and essentially self-contained movements. Examples are numerous and range from the relatively modest restatement of themes from all previous movements in the Finale of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony (1822–4), to the systematic but largely subcutaneous motivic connections between movements in César Franck’s ‘cyclic’ Symphony in D minor (1886–8), and to Antonín Dvořák’s rather less subtle deployment of the cyclic principle in his Ninth Symphony (1893). In a second group of works, individual movements remain somehow incomplete, thus requiring the presence of other movements. Anton Bruckner’s Eighth Symphony (1890 version) offers a spectacular example. Although the first movement appears outwardly closed, its recapitulation remains unsatisfactory. Only at the end of the Finale’s coda does the first movement’s main theme (along with themes from all subsequent movements) appear in the aspired tonic major. Thus solving a problem that had persisted since the first movement, the coda transcends its local function, becoming the coda not just of the Finale, but of the entire symphony. A third category, finally, comprises works in which pauses or boundaries between movements become minimised or blurred, as in Felix Mendelssohn’s ‘Scottish’ Symphony (1842) or Camille Saint-Saëns’s Third Symphony (1886). Refashioning the end of the penultimate movement as a lead-in to the finale (as in Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, 1807–8) remained an especially popular strategy at least as late as Jean Sibelius’s or Alexander Skrjabin’s second symphonies (both 1901–2).

Further examples of all three categories abound, and as several of those cited above could illustrate, any combination of these different strategies is possible – Robert Schumann’s Fourth Symphony (1841/51, already considered in Chapter 9) is an extreme example. Yet however strong the ties are between different movements and however smooth the transition from one movement to another, at the most fundamental level of formal organisation, the traditional plan of the multi-movement sonata cycle remains firmly in place in all of these symphonies.

Two-dimensional sonata form takes the inverse approach: combining the movements of a sonata cycle within one overarching sonata form, it creates the impression of a fundamentally single-movement composition. This strategy is deployed in several large-scale instrumental works by Franz Liszt, Richard Strauss and the young Arnold Schoenberg amongst others.

That two-dimensional forms hold a special place in the history of symphonic music in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries has long been acknowledged, especially by Germanic writers. In an important essay on Schoenberg’s Chamber Symphony Op. 9 (1906), Reinhold Brinkmann suggests that the ambition to integrate a multi-movement pattern into a single-movement form is typically symphonic. For Brinkmann, the Chamber Symphony is crucial in this respect: not only does it draw the consequences from ‘the problem of symphonic form in the nineteenth century’; it de facto solves it. In its formal organisation, Brinkmann writes, ‘the Chamber Symphony is an endpoint’.1

To be sure, two-dimensional sonata forms continued to be written after 1906. Yet as we will see, Schoenberg’s Chamber Symphony does mark a shift in the role they play in the history of symphonic music. For this reason, the present chapter starts with a somewhat detailed consideration of this composition, introducing a theoretical model of two-dimensional sonata form and illustrating a number of opportunities and problems associated with it. The second half of the chapter offers a tour d’horizon of two-dimensional symphonic forms composed before and after Schoenberg’s Chamber Symphony.

Schoenberg’s Chamber Symphony

Two-dimensional sonata form can be conceptualised as the loose projection of a single-movement sonata form and a multi-movement sonata cycle onto each other.2 The result is a form that unfolds in two dimensions: the dimension of the (multi-movement) sonata cycle and that of the (single-movement) overarching sonata form. Theoretically speaking, it is possible that all sections of the sonata form and all movements of the sonata cycle neatly coincide. This is the model underlying the concept of ‘double-function form’ that William Newman coined in 1969 to describe Liszt’s Piano Sonata in B minor.3 In compositional reality, this situation never occurs: not all sections of the sonata form necessarily stand in a one-to-one relationship with movements of the sonata cycle. A movement may coincide seamlessly with a section of the sonata form, but it may also overlap with only part of a section, or with parts of several consecutive sections. Often, entire movements stand between two different sections of the sonata form, thus fulfilling a function in only one of the two dimensions. Following Carl Dahlhaus’s coinage, the situation in which formal units of the sonata form and the sonata cycle coincide may be called ‘identification’; that in which a movement of the cycle stands between units of the form, ‘interpolation’.4 The opposite of an interpolated movement is an ‘exocyclic’ unit: a unit that belongs exclusively to the overarching sonata form and plays no role in the sonata cycle.

Interior movements and finales can be either interpolated or identified. For first movements, interpolation is not an option: either the overarching sonata form simultaneously functions as the first movement of the sonata cycle (which has, as it were, soaked up the ensuing movements of the cycle), or there are indications of a more-or-less autonomous sonata-form first movement in the opening portions of the overarching sonata form. Only in the latter case is the first movement of the sonata cycle identified with the initial sections of the overarching form.

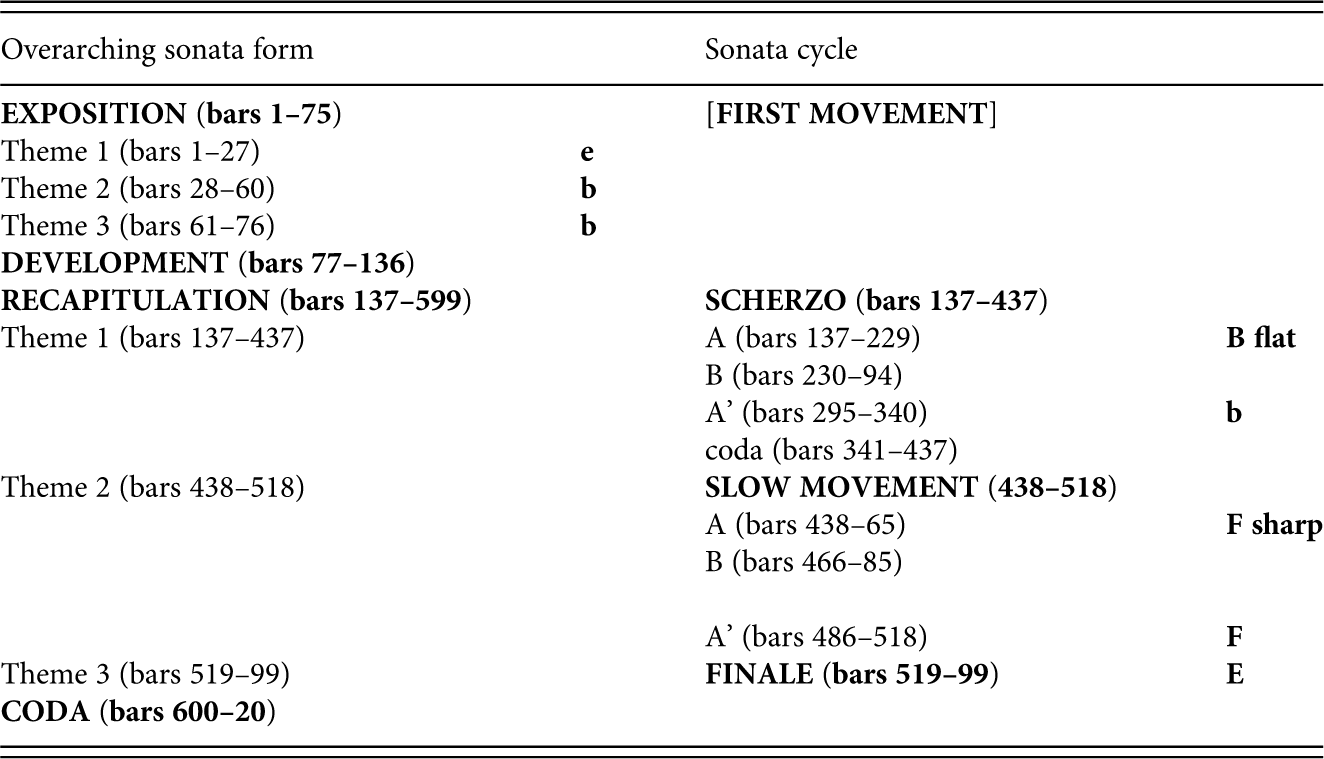

As shown in Table 11.1, applying this model to Schoenberg’s Chamber Symphony reveals that the first movement of the sonata cycle is identified with the exposition and the beginning of the development (more specifically, the false exposition repeat) of the overarching sonata form, and that the Finale is identified with both the final portion of the recapitulation and the coda of the overarching sonata form. The Scherzo, by contrast, is interpolated, standing between rather than coinciding with different units of the development. The slow movement begins as an interpolated movement, but evolves into a unit that is identified with part of the development.

Table 11.1 Schoenberg, Chamber Symphony Op. 9

Even from this superficial overview, it becomes clear why Brinkmann claims that the Chamber Symphony – or, by extension, two-dimensional sonata form in general – solves ‘the problem of symphonic form in the nineteenth century’. It is difficult to conceive of a way to integrate the separate movements of a sonata cycle more strongly than by incorporating them in an overarching single-movement form. From this point of view, two-dimensional sonata form really is the endpoint of the tendency towards cyclic integration in symphonic music of the nineteenth century.

But there is more to the issue than this. Two-dimensional sonata form does not merely address the integration of the multi-movement sonata cycle; it can also be understood in the context of that other central issue in the Problemgeschichte of nineteenth-century sonata-style composition, namely the so-called recapitulation problem. As has often been observed, many composers from the generation of Schumann and Mendelssohn onwards experienced the close analogy between exposition and recapitulation that is essential to eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century sonata form as deeply problematic. Once the onset of the recapitulation had been attained, the rest of the form could, at least in principle, unwind almost mechanically.5 If two-dimensional sonata form can be said to occupy a crucial position in the history of large-scale instrumental form in the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, then this is to a large extent because it engages with both central preoccupations of nineteenth-century form: cyclic integration and the recapitulation problem.

Indeed, what is especially fascinating about two-dimensional sonata form is that it deals with one preoccupation through the other. More specifically, the presence of a finale whose beginning coincides with or follows the onset of the recapitulation radically changes the form’s internal dynamics. If the finale of the sonata cycle appears identified with the recapitulation of the overarching sonata form, then this adds to the latter’s weight as a formal unit. The recapitulation not only acquires a double necessity – in the cycle and in the form – but also an increased independence from the exposition. If, by contrast, the finale is identified mainly with the coda or interpolated between the recapitulation and the coda, then the apex of the form shifts from the recapitulation to the finale or the coda.

In his Chamber Symphony, Schoenberg chooses the latter strategy. Most commentators have opted to let the recapitulation begin with the return of the transition from the exposition in bar 435. Given the absence of both a thematic and a tonal return, however, it is more plausible to hear bars 435–47 not as the beginning of the recapitulation, but as the end of the development; more specifically, as a retransition. This idea is particularly attractive given that the return of a transition as a retransition is not uncommon in sonata forms since the eighteenth century, especially when the order of themes in the recapitulation is inverted. This is exactly what happens in the Chamber Symphony: the recapitulation begins in bar 448 with the subordinate theme group in the tonic, which then leads to the recapitulation of the main theme group (bar 477) in the same way as it led to the closing group in the exposition.

The inversion of the thematic order in the recapitulation has far-reaching consequences. Obviously, it individualises the overall design of the recapitulation from that of the exposition. But it also postpones the most emphatic moment of return, the ‘double’ return of the main theme in the tonic. A crucial element in this strategy is that, as in the exposition, the recapitulation of the main theme is preceded by a motto. Throughout the composition, this motto functions as a formal marker, returning at almost all major junctions in the form. Its return here seems to suggest, therefore, that the reprise of the main theme is not merely the beginning of a new segment of the recapitulation, but also the beginning of something on a larger scale. Bars 474–593 can be interpreted as a full-fledged finale, with an exposition comprising a main theme, a transition and a subordinate theme, a development (mainly based on subordinate-theme material) and a truncated recapitulation. By multiplying the number of recapitulatory gestures (the return of the subordinate theme in the tonic, the double return of main theme and tonic and the recapitulation of the Finale), Schoenberg sustains the momentum much longer than would have been the case had the recapitulation paralleled the exposition. The presence of a finale that is partly independent of the overarching sonata form’s recapitulation not only enables the last of these recapitulatory gestures – which appears, naturally, very late in the piece – but in fact requires it.

All this is not to claim that the integration of a sonata cycle into a single-movement sonata form is not itself deeply problematic. On the contrary, this integration engenders a very strong tension between both dimensions that becomes particularly palpable when a movement of the sonata cycle is identified with units of the overarching sonata form. When they coincide, form and cycle often have very different requirements that are not always easily reconciled. This becomes eminently clear in bars 5–147 of the Chamber Symphony, to the extent that one might debate whether they have a double function at all. Doesn’t the first movement rather coincide with the entire overarching sonata form, which has absorbed the three following movements? There can be little doubt that on the most fundamental level, bars 5–147 constitute the exposition and false exposition repeat of the overarching sonata form. Yet it is tempting to read some of the striking features of this exposition as motivated by the simultaneous presence of the first movement of the cycle. Bars 10–57, for instance, which comprise the first and contrasting middle parts of a ternary main theme, may be heard simultaneously as the main theme, subordinate theme and closing group of a smaller-scale exposition in its own right. And the false exposition repeat in bars 136–47 can surely be understood as the abridged first-movement recapitulation (which must remain incomplete in order to avoid premature closure, thus preventing the continuation of the overarching form). But what about bars 58–135? In the overarching sonata form, they constitute the reprise of the opening part of the main theme (concluded by an emphatic cadence), the transition, the subordinate theme and the closing group. Yet all of these functions are incompatible with the development function that the same music has to fulfil in the first movement. The problem is obvious: one and the same group of formal units cannot possibly have the structure of both an exposition-cum-false-repeat and a complete sonata form; and since bars 5–135 clearly have the structure of a sonata-form exposition (a specific succession of formal functions combined with a specific cadential plan), the articulation of the sonata cycle’s first movement necessarily remains limited to a mere suggestion of some of its surface characteristics.

Difficulties of balance between both dimensions may also arise with interpolated movements. Here, the risk exists that the presence of an interpolation may seem unmotivated from the point of view of the overarching sonata form and that it may be difficult for the overarching form to resume afterwards. The ways in which composers have integrated interpolated movements into the overarching sonata are among the most analytically interesting aspects of two-dimensional sonata forms. In Schoenberg’s Chamber Symphony, the two interpolated movements are integrated into the overarching sonata form in very different ways.

The Scherzo is integrated by thematic means into the development (of the overarching sonata form) that follows it. In bars 335–54, the second phrase from the Scherzo theme (originally in bars 163–4) is developed alongside material from the exposition of the overarching sonata form and even assimilated to the latter’s main theme. Integration of the slow movement is rather achieved by formal means. When the overarching sonata form resumes in bar 415, the slow movement is left formally open; this incompleteness is compensated for later in the overarching sonata form. Bars 415–34 initially seem to be the middle section of the slow movement. Instead of leading to the expected recapitulation of the first section, however, they are followed by the return of the transition from the exposition, which belongs to the overarching sonata form. Retrospectively, bars 415–34 can be reinterpreted as a double-functional unit that is both the middle of the slow movement and the resumption of the overarching sonata form’s development. Identifying the final unit of an incomplete interpolated movement with the resumption of the overarching sonata form is a very subtle way to shift back from one dimension to the other. Only when no slow-movement recapitulation follows the middle section does it become clear that we have left the dimension of the cycle. The openness of the slow movement is redressed in the coda of the overarching sonata form. Bars 509–15 constitute an almost literal return of bars 382–6 from the slow movement’s exposition; these bars can be understood as a postponed slow-movement recapitulation.

Before

Compositions that combine form and cycle as systematically as Schoenberg’s Chamber Symphony are relatively rare; and even within this limited group of works, the idea is treated with considerable flexibility, allowing for very different individual solutions. Nonetheless, the issue of how to incorporate a multi-movement pattern into a single-movement design was addressed with some frequency by composers from the 1850s onwards, often in their most progressive large-scale instrumental music.

Few of these compositions, however, are symphonies. When Liszt experimented with two-dimensional form in the 1850s, he did so in the genres of the piano sonata (his 1853 Sonata in B minor has acquired the status of a textbook example), the piano concerto and the symphonic poem. In his Faust and Dante symphonies, by contrast, he firmly holds to a multi-movement layout. From Liszt, the interest in two-dimensional form spread all over Europe, leaving traces not only in piano sonatas by several of his pupils, but also in such diverse works as Bedřich Smetana’s symphonic poems – both the early Wallensteins Lager (1859) and Šarka (from Má Vlast, 1875) spring to mind – Saint-Saëns’s Cello Concerto in A minor Op. 33 (1872), several of Strauss’s tone poems and Schoenberg’s Pelleas und Melisande (1903). Yet when composers of the same generations titled a composition ‘symphony’, that predicate seems to have implied an essential separation of movements.

This is especially striking in the light of Brinkmann’s assertion that the problem solved in Schoenberg’s Chamber Symphony is a specifically symphonic one. It seems paradoxical that the most inherently symphonic innovation in instrumental music of the second half of the nineteenth century took place outside the genre of the symphony. At the same time, it is not a coincidence that Liszt’s interest in incorporating a multi-movement pattern in a single-movement form arose at the highpoint of what Dahlhaus and others have called the ‘tote Zeit der Symphonie’: the dead era of the symphony (although mindful of David Brodbeck’s challenge to this model in Chapter 4). As Dahlhaus remarks, one of the concomitant phenomena of the mid-century crisis of the symphony was what one could call the ‘symphonisation’ of other genres: while the symphony’s own viability as a genre was questioned, typically symphonic characteristics – such as the monumental scale, the multi-movement plan and the ambition to integrate the movements that constitute this plan – migrated to other genres.6Thus one might speak not only of the symphonic poem, but also of the symphonic sonata, the symphonic concerto, and later, in Schoenberg and Zemlinsky, even the symphonic quartet.

Several of Liszt’s symphonic poems attest to this ‘symphonising’ tendency. Whether Ce qu’on entend sur la montagne (1847–56) combines its relatively obvious overarching sonata form with the ‘allegro first movement, the slow movement, and the finale’ that Dahlhaus discerned in it remains open to debate.7But works such as Tasso (1847–54), Les Préludes (1849–55) and Die Ideale (1856–7) clearly integrate a sonata cycle into an overarching sonata form, thus transcending a simple single-movement design. In Les Préludes, for example, a relatively unadventurous sonata-form plan (slow introduction in bars 1–34, exposition in bars 35–108, development in bars 109–99; see Table 11.2) is interrupted in bar 199 by an interior movement that fuses characteristics of a scherzo and a slow movement. The presence of this movement considerably alters the further course of the form. Not only does it merge seamlessly with the transformed tonic return of the subordinate theme with which the (inverted) recapitulation opens in bar 296, but from bar 344 onwards, what initially appears to be a transformation of the transition from the exposition is expanded in such a way that it alludes to the finale of a sonata cycle. The thematic material from the transition (bars 346–55) has undergone a march-like transformation and is played in a faster tempo than in the exposition. Moreover, it is followed by a new thematic idea that is sequenced and fragmented (bars 356–69) and leads to yet another transformation of subordinate-theme material in bars 370–7. Given that bars 378–404 are a transposed recapitulation of bars 344–69, the entire unit starting in bar 344 can be regarded as a relatively self-contained (but tonally open-ended) miniature finale in ternary form. Only then, in the last bars, does the recapitulation of the main theme enter. It is not difficult to see how the form of Les Préludes addresses concerns similar to those in Schoenberg’s Chamber Symphony. The inverted recapitulation and the Finale serve the same purpose in both compositions: minimising the analogy between the exposition and recapitulation and thus sustaining the momentum until the very end of the form.

Table 11.2 Liszt, Les Préludes

One reason why similar experiments do not occur in the genre of the symphony proper might be that the younger genre of the symphonic poem came with a licence for far-reaching formal innovation unavailable in the more venerable symphony. Another probable reason is that the use of two-dimensional sonata form symphonised the essentially single-movement genre of the symphonic poem, whereas imposing an overarching sonata form on a symphony proper would have resulted in a reduction of its symphonic character. It seems unlikely that two-dimensional form would have been practicable at the grandest symphonic scale, especially after 1850. It would appear that in the genre of the symphony proper, the combination of more conservative generic conventions and the aesthetic of monumentality trumped the tendency towards integration, so that the techniques described at the beginning of this chapter might very well have been the maximum attainable cyclic integration.

Not surprisingly, then, two-dimensional form enters the genre of the symphony proper through the back door: in Strauss’s Sinfonia domestica (1902–3), a symphony in name, but fundamentally still a tone poem. The Domestica is not Strauss’s first work to combine single- and multi-movement plans. Both Don Juan and Ein Heldenleben are two-dimensional sonata forms, and Macbeth and Tod und Verklärung also contain obvious references to the interior movements of a sonata cycle, even though neither shows any trace of the outer movements. In calling his new piece a symphony, Strauss may have been drawing conclusions from the inflated proportions of his tone poems from the mid 1890s onwards. In the Domestica, the multi-movement pattern is present in an unusually direct way: a ‘Scherzo’, ‘Adagio’ and ‘Finale’ are all explicitly labelled in the score. In addition, it has often been observed that the sections before the Scherzo and the Finale ‘relate to each other, at least initially, as if they are exposition and recapitulation’.8

The form of the Domestica is, however, of considerable ingenuity and few of the labels Strauss gives can be taken at face value (see Table 11.3). In the dimension of the cycle, for instance, it is misleading to assume that one movement necessarily ends only when the next one begins. From bar 392 onwards, long before the label ‘Adagio’ appears in the score, scherzando characteristics give way to a heterogeneous succession of units, none of which seems to allow for an interpretation as part of the Scherzo. Some of them are developmental; others, such as the Wiegenlied in bars 517–46 or the unit in bars 559–88, are suggestive of a slow movement. Being tonally closed in G minor and concluding with their proper coda, both units are even more reminiscent of a self-contained slow movement than the unit labelled ‘Adagio’ (which also has its own coda, but begins in E major and ends in E-flat major).

Table 11.3 Strauss, Sinfonia domestica

The music preceding the Scherzo initially seems to be neither a full-fledged exposition nor an actual (sonata-form) first movement. Not without reason, it has often been described as an introduction that merely presents the composition’s main thematic material (labelled as ‘themes 1, 2 and 3’ in the score). Yet as Walter Werbeck has proposed, the exposition of the overarching sonata form may in fact extend as far as bar 392. In this reading, the Scherzo becomes an interpolated movement that is strongly integrated and, indeed, functionalised within the overarching sonata form’s subordinate-theme group. It transforms the initial, hesitant statement of the third theme in D minor into the grand D major restatement in bars 338–61 and projects its surface characteristics onto what begins as a closing group but soon becomes a transition to the development (bars 362–92).

In the dimension of the overarching sonata form, bars 1–152 (theme 1, theme 2 and the varied return of theme 1, ending with a perfect authentic cadence in the tonic) constitute a ternary form that functions as a main-theme group balancing the lengthy subordinate-theme group. That the middle of the main-theme group bears the label ‘theme 2’ may be explained by its function in the first movement of the sonata cycle. For it may not be too much of a stretch to claim that the juxtaposition of two starkly contrasting themes, the superficially developmental characteristics of the later portions of part B and the stereotypical retransition preceding the return of part A suggest something of a small-scale sonata-form first movement. In the context of the piece as a whole – that is to say, being followed by three further immediately recognisable movements of a sonata cycle – they certainly can be heard as such.

Strauss’s thematic labels in the large ‘Finale’ are equally misleading. It is not difficult to see how this unit can be heard as both a finale and a recapitulation: its formal course and stylistic register differ from the exposition, but at the same time it recapitulates all of its themes (in a more-or-less transformed shape, but in the original key). This recapitulation is, however, less straightforward than it may initially seem. Theme 1 of the double fugue is not a transformation of theme 1 in the exposition, but of theme 3 in the key of theme 1 (or at least its head; the rest is new). Only much later does motivic material from the exposition’s theme 1 start to make itself heard.

After

While Strauss, Liszt and the composers between them use two-dimensional sonata form to symphonise the tone poem (or other genres), Schoenberg does exactly the opposite. In his Chamber Symphony, two-dimensional sonata form is what enables the highly un-symphonic compression of the multi-movement plan, a compression that parallels the piece’s reduced instrumentation. If the Chamber Symphony can be said to solve the problem of symphonic form, its cost is a significant loss in monumentality and, thus, symphonicity. Therefore, its form is not so much (or not only) an endpoint in the sense of a culmination of nineteenth-century symphonic form, but rather (or also) a reaction against the genre’s excesses.

After Schoenberg’s Chamber Symphony, two-dimensional sonata form ceased to be the vehicle of the musical avant-garde it had been since the 1850s. In the decades following 1906, its use often constitutes a deliberately conservative gesture. In the few pieces in which it is used otherwise, formal organisation becomes increasingly free, moving away from both sonata form and sonata cycle. Franz Schreker’s Chamber Symphony of 1917, for instance, has less in common with Schoenberg’s eponymous Op. 9 than its title suggests, treating the combination of multi- and single-movement plans in a considerably less rigorous way. It consists of a lengthy introduction and a sonata form, within which the interior movements of a sonata cycle have been interpolated. More specifically, the (relatively brief) development of the overarching sonata form is preceded by a slow movement and followed by a scherzo. Surprisingly, the slow movement reappears in its entirety between the recapitulation and the coda of the overarching form. Traces of a first movement and a finale, moreover, are lacking.

A similar tendency towards looser large-scale formal organisation can be observed in the First Symphony, Op. 7 (1921) by Ernst Krenek (a student of Schreker). In spite of the proliferation of contrasting sections – some clearly reminiscent of movements from a sonata cycle or sections from a sonata form, others less so – Krenek’s Symphony retains a strong sense of overarching formal design, especially through the recapitulation of the opening section right before the coda. The overarching form, however, is not a sonata form, nor can the multi-movement pattern be considered a sonata cycle.9

Starkly contrasting with Schreker’s and Krenek’s handling of two-dimensional form is the Fourth Symphony (1932–3) of the Viennese composer Franz Schmidt. Schmidt’s conception of two-dimensional sonata form is significantly more traditional. The first movement of the sonata cycle is identified with the exposition and development of the overarching sonata form (the development simultaneously functions as a recapitulation). The slow movement and the Scherzo are interpolated between the development and the recapitulation, which can be heard as a finale only because of the conspicuous presence of the preceding three movements of a sonata cycle. Schmidt’s Symphony is remarkable for its symmetrical design. The middle section of the central slow movement begins with a melody that modulates from G minor to C-sharp minor and is thereupon repeated, now beginning in C-sharp minor and, consequentially, modulating back to G minor. From this middle section, symmetry expands over the entire Symphony. It comprises the introductory trumpet solo, the exposition, the development and the opening section of the slow movement on one side, and the reprise of the slow movement, the interpolated Scherzo, the recapitulation and the concluding trumpet solo on the other. The tritone relationship at the heart of this symmetrical plan is reflected at several other formal levels, such as the tonal organisation of the exposition (main-theme group in C, subordinate-theme group in F sharp) and the recapitulation (main-theme group in F, subordinate-theme group in B).

An important single-movement symphony that stands somewhat apart from the Germanic tradition is Jean Sibelius’s Seventh Symphony (1924). This work’s most striking characteristic is that its overarching form is slow and that, as a consequence, the different movements do not amount to an orthodox sonata cycle. In addition, neither in the overarching form nor in any of the movements of the sonata cycle does Sibelius make use of standard Formenlehre forms. After a slow introduction (bars 1–22), what follows seems to be an exposition that culminates in the statement of the grand trombone theme in C major in bar 60. This theme, along with its two later appearances, first in C minor (bars 222–41), then back in C major (bars 476–507), structures the overarching form. The three statements of the trombone theme provide a framework within which the other sections and interpolated movements appear in an arch-like design (see Table 11.4). The first statement is followed by a development and a scherzo-like interpolated movement, the second statement by another interpolated movement and a unit that forms a pendant to the first development. After the trombone theme’s climactic last statement, the Symphony concludes with a coda that recalls the introduction. Boundaries between different sections in Sibelius’s Seventh are often remarkably fluid, so that reading a symphonic pattern into it may seem tendentious. It is, however, a reading that the composer himself purposely seemed to invite. After the work had been premiered as ‘Fantasia sinfonica’, Sibelius not only decided to rename it to ‘Symphony No. 7’, but also added the (conspicuously German) subtitle ‘In einem Satze’.

Table 11.4 Sibelius, Symphony No. 7

An echo of Sibelius’s Seventh resounds in Samuel Barber’s First Symphony (1936), which is similarly subtitled ‘In One Movement’. Although there are strong indications that Barber’s Symphony was intended as a response to Sibelius’s, his single-movement design remains significantly closer to Central-European models. As shown in Table 11.5, it begins with a three-theme exposition. The development that follows gives way not to a recapitulation, but to the three further movements of a sonata cycle: a Scherzo, a slow movement and a Finale. Both interior movements are ternary forms, and their main thematic material is derived from the exposition’s main and subordinate themes respectively. At the same time, both movements conspicuously avoid tonal closure, bringing a recapitulation in a key a half step away from their expositions. Each of the interior movements culminates in a grand restatement of the motto-like opening of the main theme. The Finale is a passacaglia on a bass derived from the opening of the main theme that appears thirteen times in total. In the initial variations, thematic material appearing over the bass is either new or else derived from the exposition’s third theme (now transposed to the tonic).

Table 11.5 Samuel Barber, Symphony No. 1

The way in which Barber integrates form and cycle is unique: all movements from the Scherzo onwards are identified with the recapitulation of the overarching sonata form. A thematic recapitulation is thus spread out over the three movements in the sense that thematic material from the exposition reappears in the original order as the main thematic content of each movement. From the Finale onwards, this relatively abstract recapitulatory layer is combined with the increasing prominence of the main theme’s head motive at pitch, first as a bass for the passacaglia, then, especially from variation eight onwards, saturating the entire texture. At the climax of the Finale (variations eleven and twelve), the head of the main theme is contrapuntally combined with theme three from the exposition.

Barber’s First Symphony might very well be the last important two-dimensional sonata form in the orchestral repertoire. In it, this extraordinary principle of formal organization comes full circle. Its function for Barber is the same as for any composer of the Germanic musical avant-garde of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries: it guarantees a maximal degree of cyclic integration between the different movements of his Symphony. More than any other composition discussed in this chapter, however, Barber’s Symphony attests to two-dimensional sonata form’s inherent symphonicity. This may seem surprising, given Barber’s chronological and geographical distance from the heyday of two-dimensional sonata form several decades earlier and on another continent. It is, however, exactly because he was working in so different a context that Barber could, as it were, quote two-dimensional sonata form as a token of the nineteenth-century symphonic style that he was trying to emulate. In doing so, he succeeded in what for composers of the generations of Liszt, Strauss and Schoenberg seemed impossible: to write a symphony in two-dimensional sonata form that is truly symphonic.

Notes

1 ‘Die Kammersinfonie zieht Konsequenzen aus dem sinfonischen Formproblem des 19. Jahrhunderts wie es Schönberg aus seinem Traditionsverständnis heraus begriff, und erklärte es durch sich für erledigt . . . [A]nders also als in den übrigen Schichten der Komposition [harmony, thematic organisation, polyphony, instrumentation] ist hier die Kammersinfonie ein Endpunkt.’ See , ‘Die gepreßte Sinfonie. Zum geschichtlichen Gehalt von Schönbergs Opus 9’, in , ed., Gustav Mahler. Sinfonie und Wirklichkeit, Studien zur Wertungsforschung, 9 (Graz, 1977), 133–56 , this quotation 142.

2 For a fuller introduction to the theory of two-dimensional sonata form as well as an analytical discussion of a number of individual works, the reader is referred to the author’s Two-Dimensional Sonata Form: Form and Cycle in Single-Movement Instrumental Works by Liszt, Strauss, Schoenberg, and Zemlinsky (Leuven, 2009).

3 , The Sonata since Beethoven (Chapel Hill, 1969), 134 and 375–7. Newman writes that Liszt’s Sonata in B minor ‘is not a simple “sonata form” but a double-function form, because its several components also serve as the (unseparated) movements of the complete cycle’ (p. 134).

4 , ‘Liszt, Schönberg und die große Form. Das Prinzip der Einsätzigkeit in der Mehrsätzigkeit’, Die Musikforschung, 41 (1988), 202–13.

5 Needless to say, this doesn’t always happen. But modifications to the course of the recapitulation in sonata forms from the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, too, can be understood as attempts to avoid an extreme parallelism with the exposition.

6 , ‘Liszts Idee des Symphonischen’, in Klassische und romantische Musikästhetik (Laaber, 1988), 392–401.

7 , ‘Liszts Bergsymphonie und die Idee der Symphonischen Dichtung’, in , ed., Jahrbuch des Staatlichen Instituts für Musikforschung Preußischer Kulturbesitz 1975 (Berlin, 1976), 96–130, this quotation 99.

8 , ‘Richard Strauss’s Tone Poems’, in , ed., The Richard Strauss Companion (Westport, 2003), 103–44, this quotation 132.