Introduction

I feel contaminated by everything, 24 hours a day. . . all over my body and inside myself. To me everything is contaminated, it is just a case of to what degree. . . All the washing and cleaning brings no relief. Just thinking about the government. . . seeing a brown envelope. . .thinking about my wife and all that happened. . .I feel dirty and contaminated and I have to wash. (A patient, referred to as David, talking about his OCD symptoms)

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) affects between 1% and 2.5% of the population (Torres et al., Reference Torres, Prince, Bebbington, Bhugra, Brugha and Farrell2006; Karno, Golding, Sorenson and Burnam, Reference Karno, Golding, Sorenson and Burnam1988) and has been found to be associated with high comorbidity, significant social and occupational impairment and high rates of attempted suicide compared to other anxiety disorders (Torres et al., Reference Torres, Prince, Bebbington, Bhugra, Brugha and Farrell2006). Contamination concerns and the related compulsion to wash excessively is one of the most common presentations of OCD, reported by 38–50% of people with the disorder (Rachman and Hodgson, Reference Rachman and Hodgson1980; Foa et al., Reference Foa, Kozak, Goodman, Hollander, Jenike and Rasmussen1995). Common contamination concerns tend to be culture-specific, with clinically presenting themes being relevant to the difficult-to-see threats in a given society at a given time. For example, contamination-based obsessions increased following the discovery of germs and their link to illness in the late 1800s, with concerns about radiation increasing following World War II and more concerns about illnesses such as HIV and CJD over the last 20 years given media coverage. To date, our understanding of contamination concerns has been predominantly based around the presumption that people experience worries and feelings of contamination when in direct physical contact with a contaminant where there is a threat to life or health, most often dirt, germs or toxic substances (Rachman, Reference Rachman2006). However, is this explanation of contamination adequate to formulate the quote presented above?

If direct physical contact with a life threatening contaminant is required in contamination obsessions, how can we explain obsessions of contamination where no physical contact with a life threatening substance takes place? The quote above is taken from a patient, later referred to here as David, who was not concerned by dirt, germs or toxic substances; David's feelings of contamination were triggered by anything he viewed as being related to the government, such as the National Health Service, Royal Mail, public services, local authorities, any letters from governmental agencies, particularly brown envelopes. He went to great lengths to avoid coming into contact with anything related to the government, as this apparently triggered past memories of a very difficult time in his life when he had been “treated with contempt, nastiness. . . they [government organizations] were not interested. . .they looked down on me as though I was rubbish.” This was linked to the break-up of his marriage; he was mistreated and “betrayed” by his wife and by the government bodies concerned with child support.

The phenomenon of people experiencing themselves as contaminated and washing excessively without physical contact with a contaminant but instead following traumatic acts of betrayal is often referred to in literature; particularly well known is Shakespeare's Lady Macbeth seeking to wash away the stain of murder. Religious rites often include ritual cleansing and purifying. Rachman (Reference Rachman1994) has recently provided a framework to make sense of the OCD manifestation of such phenomena and the linked washing behaviours, coining the term mental contamination:

Mental contamination can arise without physical contact with a contaminant. . .Because it is non-physical in nature, people often have difficulty locating the source and bodily location of their dirtiness and may describe it as an internal or emotional dirtiness. . .washing is generally futile as the contamination is not physical in nature. (Herba and Rachman, Reference Herba and Rachman2007, p. 2805).

A number of studies carried out in student populations illuminate the phenomenon of feeling dirty in the absence of physical contact (Elliot and Radomsky, Reference Elliott and Radomsky2009; Radomsky and Elliott, Reference Radomsky and Elliott2009; Fairbrother, Newth and Rachman, Reference Fairbrother, Newth and Rachman2005).

Rachman proposes that mental contamination differs from contact contamination in a number of ways as summarized in Table 1. For example, he postulates that people experiencing mental contamination will be less likely to identify the bodily location of their contamination, unlike contact contamination where people most frequently report their hands feeling dirty. Rachman also proposes that people with mental contamination will be more likely to report a sense of “all over” or pervasive internal dirtiness. Furthermore, a range of specific emotions may be linked to mental contamination in addition to anxiety and disgust, including shame, humiliation and contempt. Rachman also proposes that the source of mental contamination is primarily a person/people rather than a substance. These proposals are supported by a small qualitative study of 20 participants with a diagnosis of OCD by Coughtrey and colleagues (Coughtrey, Shafran, Lee and Rachman, Reference Coughtrey, Shafran, Lee and Rachman2012).

Table 1. Some of the key features of mental contamination compared to contact contamination (based on Rachman, Reference Rachman2006)

Particularly relevant in the case of David described here, Rachman also discusses the role of being violated and/or betrayed by another person, physically or emotionally, in the development of mental contamination and OCD. Rachman discusses the importance of betrayal, here defined as “a sense of being harmed by the intentional actions, or omissions, of a person who was assumed to be a trusted and loyal friend, relative, partner, colleague or companion” (Rachman, Reference Rachman2010, p. 304). He presents a number of cases whereby betrayal was a key incident in the development of later washing compulsions and other obsessive compulsive symptomology. A further experimental study by Coughtrey and colleagues (Coughtrey, Shafran, Lee, Enright and Rachman, Reference Coughtrey, Shafran, Lee, Enright and Rachman2011) has also looked at past experiences of betrayal in a student sample, and found that bringing this memory to mind did lead to some participants feeling dirty and experiencing an urge to wash.

Rachman (Reference Rachman2010) proposes that, for effective outcomes, treatment for mental contamination in OCD might need to differ from standard OCD treatment, and have more of a cognitive focus with less exposure-based experiments until the patient has been helped to deal with their sense of internal contamination, so seeking to break the link between this and the avoidance and washing rituals. This is noteworthy, given that although psychological treatments for OCD, including exposure and response prevention (ERP; Meyer, Reference Meyer1966) and cognitive therapy (Rachman, Reference Rachman1997; Salkovskis, Reference Salkovskis1985, Reference Salkovskis1989, Reference Salkovskis1999), have been found to be effective in a number of randomized controlled trials (Foa et al., Reference Foa, Liebowitz, Kozak, Davies, Campeas and Franklin2005; Cottraux et al., Reference Cottraux, Note, Yao, Lafont, Note and Mollard2001; Van Oppen et al., Reference Van Oppen, de Hann, van Balkom, Spinhoven, Hoogduin and van Dyck1995; De Haan et al., Reference De Haan, van Oppen, van Balkom, Spinhoven, Hoogduin and van Dyck1997; Ladouceur, Leger, Rheaume and Dube, Reference Ladouceur, Leger, Rheaume and Dube1996; Greist et al., Reference Greist, Marks, Baer, Kobak, Wenzel and Hirsch2002) and effectiveness studies in clinic settings (Houghton, Saxon, Bradburn, Ricketts and Hardy, Reference Houghton, Saxon, Bradburn, Ricketts and Hardy2010), a number of these studies have reported high refusal and drop-out rates (Foa et al., Reference Foa, Liebowitz, Kozak, Davies, Campeas and Franklin2005; De Hann et al., Reference De Haan, van Oppen, van Balkom, Spinhoven, Hoogduin and van Dyck1997). Furthermore, a number of people do not reach statistically reliable reductions in symptomology at the end of treatment (as measured by the Yale Brown Obsessive Compulsive Inventory (Y-BOCS; Goodman et al., Reference Goodman, Price, Rasmussen, Mazure, Fleischmann and Hill1989) (Abramowitz, Taylor and McKay, Reference Abramowitz, Taylor and McKay2009) and for those who do show significant improvement, mean scores often indicate ongoing symptomology reaching clinical levels (Foa et al., Reference Foa, Liebowitz, Kozak, Davies, Campeas and Franklin2005; Cottraux et al., Reference Cottraux, Note, Yao, Lafont, Note and Mollard2001; De Hann et al., Reference De Haan, van Oppen, van Balkom, Spinhoven, Hoogduin and van Dyck1997; Greist et al., Reference Greist, Marks, Baer, Kobak, Wenzel and Hirsch2002). Rachman's proposals could in part explain some of these findings, given the prevalence of mental contamination (Radomsky and Elliot, Reference Radomsky and Elliott2009). The effectiveness of cognitive treatment focusing on mental contamination has, however, yet to be tested.

In this paper a case of a man with mental contamination-based OCD following significant experience of betrayal is presented. David had received previous inpatient and outpatient CBT treatments with limited success. Most recently, he was offered a high quality CBT intervention at a specialist OCD clinic from a highly experienced therapist receiving appropriate supervision, but he disengaged from this treatment with little benefit after 6 sessions. He was then reviewed and treated by the authors based on Rachman's suggestions for modifying treatment in such cases. The service user, who is referred to here as David, has given his consent for details of his case and treatment to be published. Some minor details of David's case history have been altered slightly to aid anonymization. David's case and treatment are outlined and discussed below. It is hypothesized that previous treatment failure arose from the way treatment had been focused and that a focus on mental contamination would be more effective than conventional CBT.

Method

Background information to the case

Presenting difficulties. As outlined above, David was a man in his 40s who had been referred to a specialist outpatient OCD service following a 20-year history of OCD, characterized by compulsive washing and cleaning and obsessions about things related to the government being contaminated. He reported OCD being a problem every waking hour of the day and he was unable to work due to his OCD: he had not done so for 20 years. David's family also had to engage in cleaning routines when entering and leaving the house. His initial YBOCS score was well into the “severe” range.

Previous treatment. David had been trialled on a number of medications including Prozac, Sertraline, Clomipramine and Olanzapine, all at the higher range of recommended doses. He described none of these previous treatments having any significant impact on his OCD symptoms. He was not taking any medication at the time of attending for treatment.

David reported previously having a 3-month inpatient stay at a national specialist OCD unit and had been offered a course of CBT at this time. He then had 4 years of outpatient CBT from this unit and around 30 sessions of private CBT treatment. He reported good engagement with past CBT and that his treatments had predominantly used ERP as the main intervention.

Assessment measures

At assessment the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS; Goodman et al., Reference Goodman, Price, Rasmussen, Mazure, Fleischmann and Hill1989) was used. This is a semi-structured interview-based rating scale found to have acceptable internal consistency, inter-rater reliability and convergent validity (Woody, Steketee and Chambless, Reference Woody, Steketee and Chambless1995). The Y-BOCS consists of 19 items, but the first 10 items are used to calculate the total score, with a maximum potential score of 40. David scored 34 at assessment, which above the clinical cut-off and within the severe range (32–40).

David was given the Obsessive Compulsive Inventory (Foa, Kozak, Salkovskis, Coles and Amir, Reference Foa, Kozak, Salkovskis, Coles and Amir1998), which is a 42-item self-report questionnaire with a maximum potential score of 168, found to have good construct validity, internal consistency and test re-test reliability (see Foa et al., Reference Foa, Kozak, Salkovskis, Coles and Amir1998) that assesses the frequency and distress experienced by individuals from various symptoms across 8 domains of washing, checking, doubting, ordering, obsessions, hoarding, and neutralizing. David scored 47 at assessment, above the clinical cut-off of 40.

David was also given a short version of The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; Spitzer, Kroenke and Williams, Reference Spitzer, Kroenke and Williams1999), a 9-item self-report measure assessing symptoms of depression, with a maximum potential score of 27. The measure has been shown to be a reliable and valid measure of depression severity. David scored 16, within the moderately severe range (15–19).

David also completed the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7; Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Lowe, Reference Spitzer, Kronke, Williams and Lowe2006), which is a validated self-report tool assessing generalized anxiety disorder, although it has found to be reasonably accurate in assessing for panic, social anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorders. There is a maximum potential score of 21. David scored 16 at assessment, falling in the severe anxiety range (15–21).

Finally, David completed the Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS; Mundt, Marks, Greist and Shear, Reference Mundt, Marks, Greist and Shear2002). This is a 5-item self-report scale with a maximum score of 40 that has been found to be a reliable and valid measure of impaired functioning. David scored 35 at assessment, indicating that his difficulties lead to a high level of impact on his daily functioning.

The Vancouver Obsessive Compulsive Inventory-Mental Contamination Subscale (VOCI-MC; Rachman, Reference Rachman2009) is a self-report questionnaire assessing items related to mental contamination and internal dirtiness; it consists of 20 items, with a potential maximum score of 80. David was administered this measure following his initial 6 sessions of CBT but not at initial assessment to the clinic and scored a total of 37 on this item at the start of treatment, which is above an estimated clinical cut-off of 20 or greater on the VOCI-MC, calculated on data currently in preparation for submission (Radomsky et al., in preparation).

First treatment option: high quality CBT treatment

Following David's referral to a clinic specializing in OCD treatment, he was offered a course of high quality CBT with an experienced therapist and attended 6 sessions. These sessions used a cognitive model of OCD to formulate and treat David (Salkovskis, Reference Salkovskis1985, Reference Salkovskis1989, Reference Salkovskis1999). The majority of sessions were focused on cognitive restructuring and behavioural experiments using ERP, putting to the test two theories: Theory A: “The problem is contamination by government/council items – a physical problem”; Theory B: “The problem is I worry about contamination by government/council items – a psychological problem”). However, David disengaged with this treatment after 6 sessions as he reported he did not think the treatment was helping. Despite David's observations, his scores had somewhat improved and fallen below the clinical cut-off on a self-report measure of OCD (OCI) at the end of these sessions. Nevertheless, in terms of his scores on a self-report measure looking at the impact of his problems on his functioning (WASA) and a clinician rated measure of OCD severity (Y-BOCS), there had not been clinically significant improvement. Of note, David's assessment baseline score on the OCI was not very high and, as discussed later, it is unlikely that this measure captures David's mental contamination. However, the change in this measure over the sessions possibly indicates that other more “typical” aspects of his OCD might have been effectively targeted in this episode of treatment even if the mental contamination was unaffected.

Second treatment option: cognitive therapy focused on mental contamination (CTMC)

Given that mental contamination had been identified to be part of David's problem, he was then offered a review with the current authors, due to specialist expertise in mental contamination. A total of 13 sessions of treatment were then offered and attended, with an additional two follow-up appointments (at 4 and 6 months). The initial 8 treatment sessions were extended in length to two hours and remaining sessions were an hour long (approximately 23 hours of treatment in total). Treatment was delivered in a number of steps:

1. Extended assessment and formulation;

2. Psychoeducation and socialization to the mental contamination model;

3. Motivation to change and goal setting;

4. Cognitive work on key appraisals, including imagery re-scripting;

5. Behavioural experiments using ERP and stimulus discrimination;

6. Reclaiming life following OCD;

7. Relapse prevention and booster sessions.

These will be outlined below.

Extended assessment and formulation. An extended period of assessment was given across two intensive sessions. Following detailed exploration it materialized that the onset of David's difficulties had followed a number of events that had left him feeling betrayed, angry and distressed. Just prior to his OCD starting, David's wife had left him and he discovered that she had been having affairs with other men. David described the “deceit and lies” he experienced as being distressing “emotional traumas” and “betrayals”. He reported his home was cleared out and his children taken from him. He was served divorce papers in a brown envelope in a manner that made him feel as though he had been treated “like rubbish” and felt “pure rage” at what he saw as immoral treatment. David was so distressed at the time he was unable to keep his job, working as a civil servant in a large organization. The ongoing legal “battles. . .fighting for every single thing” and disputes with governmental agencies, such as the child support agency, left David homeless and penniless. He described a number of experiences of the local Jobcentre and other agencies where he:

Had to line up with all the dregs. . . I don't like to be unemployed but they were not interested. . .they looked down on me as though I was rubbish, like a sponger.

He described how endless letters in brown envelopes from governmental agencies arrived in his home “like an invasion”; soon he started to feel “disgusted” when he saw any brown envelopes or anything related to the government and started to think these items were contaminated.

David started to feel compelled to wash and clean around the time of his divorce when thinking about the situation. At the start of treatment he said “I felt like I cannot escape from feeling contaminated”; understandably so, given that his own thoughts and memories were leading to these distressing feelings. When thinking about these events or agencies he reported not only feeling contaminated but also feeling angry and humiliated. David was often unaware that the memories of these events had been triggered, yet engaged in hours of washing to try to cleanse himself after being faced with a reminder, such as a brown envelope. In addition to washing, when David got an intrusive thought or memory about these events he would also at times bring what he called “the right thought” to mind: an image of a female friend who had treated him well in the past. However, these neutralizing behaviours were not leading to any relief for him.

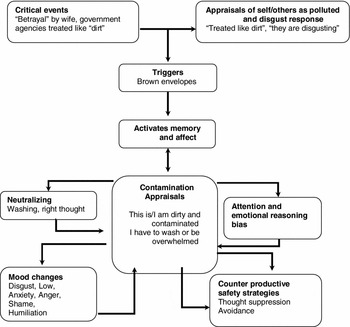

An idiosyncratic formulation was drawn up to explain David's difficulties (see Figure 1). This was in part based on the cognitive model for OCD (Rachman, Reference Rachman1997; Salkovskis, Reference Salkovskis1985) and on the authors’ developing cognitive theory of mental contamination. It was proposed that the key life events of betrayal that David had experienced had been appraised in such a way that to him the people involved, including himself, were polluted: “treated me like dirt. . .like. . .rubbish”. These appraisals understandably led him to feel angry, humiliated, disgusted, low and ashamed, at the time making these events even more distressing for him. It is hypothesized that these memories were possibly not fully integrated into his autobiographical memory system, as in other self-defining memories (Singer and Salovey, Reference Singer and Salovey1993), so were easily triggered by environmental stimuli (such as brown envelopes, or any other reminder of the government). When the “pollution memories” were triggered for David, for example when faced with a reminder of the government, it was predominantly the affect driven by his appraisal of these events that he experienced (as in “affect without recollection” in PTSD: Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000), including disgust, feeling low, ashamed, angry, contempt and humiliated. David then appraised this affect to mean that he must be contaminated in the present moment and interpreted the environmental stimuli (reminder of government) to have caused it. This misinterpretation was possibly informed by emotional reasoning bias (Beck, Emery and Greenberg, Reference Beck, Emery and Greenberg1985), a sort of “feeling action fusion” rather than the more commonly seen “thought action fusion”. Understandably, David then engaged in a number of neutralizing behaviours such as washing and bringing pleasant images to mind to try to avoid the distressing thoughts and feelings he was experiencing. He also used other safety seeking strategies such as pushing unwanted thoughts away and avoiding feelings and situations that might trigger this distress again (i.e. anything government related). Unfortunately, it was hypothesized that these behaviours maintained his negative appraisals and the self-defining nature of the memories.

Figure 1. David's formulation

Psychoeducation and socialization to the model. Once a detailed history had been taken the session content moved to helping David develop an alternative way to view his problems. Psychoeducation was used and the notion of mental contamination was explained to David. A number of case examples of people who had developed contamination concerns following betrayals, reported in a paper by Rachman (Reference Rachman2010), was given to David to read.

The model was not drawn out in full with David at this stage but instead a number of probes (Rachman, Reference Rachman2006) were used to socialize him to the model, helping him see it as a problem of memory and appraisals of past events, not contamination. The following steps were taken:

(a) The patient was asked to rate how distressed and contaminated he felt and how much he feels an urge to wash (0–100%) whilst sitting in the session.

(b) The patient was then asked to close his eyes if he felt comfortable and to bring images of a key violation/betrayal event to mind and keep this in his mind's eye for around 2 minutes, raising his hand when it was vividly held.

(c) The patient was then asked to re-rate how distressed and contaminated he felt, where he felt this, and how much he felt an urge to wash (0–100%) in the moment.

(d) The patient was then asked what he made of this: that he can feel contaminated and have urges to wash in the absence of coming into any physical contact with a contaminant but when he is only thinking of a memory.

David reported initially feeling not at all contaminated or having any urges to wash, but this is what happened when David was asked to close his eyes and bring to mind the image of a memory that bothered him regularly: being interviewed in a Jobcentre by somebody who treated him “like rubbish”:

Therapist: Ok, keep it [the image] in your mind, as clear and realistic as you possibly can. (Pause) How does it feel?

David: Very contaminated. I feel contaminated all over, not just on my hands.

Therapist: Out of 100, how intense is it?

David: Probably about a 90%.

Therapist: What do you make of that?

David: I don't know.

Therapist: Does is surprise you that you can feel that contaminated without touching anything physically?

David: Completely shocked.

Therapist: If you can feel contaminated by a memory in your mind, how will washing your poor hands help?

David: I can't see how it will.

Therapist: You are right, if the problem is your memories and images that make you feel contaminated washing your hands is misdirected. It is never going to get rid of the problem.

The probe provided a rationale for taking a different approach in treatment: working on these distressing memories. Two explicit contrasting ways of looking at his problem (Theory A vs Theory B) were developed:

Theory A: My problem is government material, which is contaminated and makes me contaminated and I need to wash to get rid of it.

Theory B: My problem is that when I am reminded of the betrayals I experienced (by memories or objects that act as reminders of government's influence on me), I feel a hangover of how I felt at the time - upset, angry, disgusted, like rubbish, and I therefore worry that this means I'm contaminated and need to wash to get rid of it.

Motivation to change and goal setting. Time was spent exploring the cost of David's OCD on his and his family's life so far. Given the longevity of his OCD it was important to spend time developing achievable short and medium term goals, but to also consider long-term goals. David was asked to picture himself achieving his goals and what that might be like; these sessions started to install some hope of change after many years limited by obsessions and compulsions. David wanted, in the short term, to go out to shops locally, go for walks in hills, do more DIY at home, have his parents over to his home, and take his son out for the day. In the medium term, he wanted to allow his son to move freely around the home without restrictions, help his son with his homework, start using avoided organizations such as the Royal Mail and, in the longer term, eventually to return to work.

Early on in treatment David was guided to see that the unfair treatment he had received was in part being continued by hours of washing and that David needed to fight back to reclaim his life. David was asked to identify a colour to represent his fight back against OCD and with political relevance (to a contemporary eastern European freedom movement) he chose orange: David's orange revolution began. Another metaphor of David captaining the good ship HMS Defiance against OCD was developed. These metaphors were used as a short-hand throughout therapy to help motivate David to continue to the fight/revolution against OCD.

Cognitive work on key appraisals, including imagery re-scripting. Approximately 5–6 hours of therapy at this stage was devoted to imagery re-scripting. Rachman suggests when it comes to memories that this is done in line with re-scripting as suggested by Arntz and Weertman (Reference Arntz and Weertman1999) and done in roughly three memory stages, in addition to cognitive restructuring to work on the meaning as suggested by Wild, Hackmann and Clark (Reference Wild, Hackmann and Clark2008) when working with negative images in social phobia:

1. The person recalls the memory in the first person, present tense as they experienced it.

2. Cognitive restructuring is used to reappraise the meaning of the event.

3. The person re-forms the memory and changes the outcomes.

This approach was used to work on changing the meaning David had attached to key events that led to his contamination feelings. For example, David being treated particularly badly by staff at a Jobcentre. The meaning of this memory to David was that “I was treated like rubbish, I'm worthless”. Cognitive restructuring helped David to start to develop an alternative view, “I am a good person, worthy of respect”. David was encouraged to re-script the memories to represent his new meaning. David chose to completely transform the image to one where he was being treated like this: the image moved to him being in a hotel, being addressed by his full name and treated with the respect he deserved. This process was repeated for a number of David's key memories: the meaning of each shifting from one of pollution to a more helpful alternative.

Behavioural experiments using exposure and response prevention and stimulus discrimination. Behavioural experiments with exposure constituted a small section of treatment (1–2 sessions and homework tasks set) and followed cognitive work. Two experiments were done in the sessions, touching brown envelopes and reading letters from governmental organizations (such as the inland revenue) and David was encouraged to visit previously avoided buildings, such as NHS sites and polling stations outside of the sessions. As is common in mental contamination, David predicted that nothing bad would happen by exposure to these avoided situations, but that he would feel uncomfortable.

David was observed to have poor stimulus discrimination, i.e. any small similarity between a current stimulus and those present at the time of his betrayals would trigger the memory and associated distress. Therefore, during some experiments a version of stimulus discrimination, a technique described by Ehlers and Clark (Reference Ehlers and Clark2000) and often used in PTSD treatment, was utilized. David was encouraged to observe the differences between “then” (at the time of the betrayal memories) and “now” (holding the brown envelope in the session without any current threat to himself) to realise any distress was a type of “echo” of the past.

Interestingly, during these sessions David noticed that he became upset and cried when exposed to brown envelopes without washing. He was surprised at this and did not know what to make of it, he reported “I didn't think [that touching envelopes] would make me sad”. He rated his feelings when exposed to the envelope as “feeling rotten with sadness”. When this first occurred he promptly slapped himself in the face in the session. On exploring this it became apparent that he did not like to tolerate feelings of sadness. This was used as another illustration that the problem was not one of contamination but feeling upset by past memories that he was trying to avoid. Of note, the following session David had started to make a number of key changes in his life, such as allowing his son to bring post into the house, allowing his son not to wash when he returned home from college, and his own daily washing significantly reduced. He reported his life reaching “80% normality”. When asked what had shifted so much David replied “seeing it completely differently – I am uncomfortable by these things but not contaminated”.

Work on reclaiming life following OCD. As David started to reduce his washing he was left with a lot more time on his hands and limited enjoyable activities, since his OCD had dominated most of his waking day for so many years. He was encouraged to work on scheduling in a mixture of activities with pleasure and mastery and to continue to work towards his goals.

Relapse prevention and booster sessions. The final two sessions and two further follow-up sessions were focused on summarizing the main things David had taken from treatment, how to keep going with his progress and what to do if problems came up again in the future (therapy blueprint was used here).

Results

Following his initial 6 sessions of standard CBT there were some improvements noted in David's OCI scores but no other changes observed; the patient did not want to engage in further sessions as he did not think the sessions were helpful. Following completion of CTMC, David reported that excessive washing due to concerns about contamination was no longer a problem for him. David made good progress with his goals, and reported that he was able to use his local facilities, including buildings he had previously seen as being contaminated by the government, such as local libraries. His family were able to move around the house freely and he was accepting items from royal mail into his home. He was looking for work but finding this difficult, partly due to the economic climate but also having been out of work for 20 years. This contributed to his being in low mood at the follow-up session but he remained determined to get work and that the OCD was not holding him back from this. David gave his therapists a gift at the final session, wrapped up in a number of brown envelopes that he reported no longer bothered him.

Table 2 shows David's weekly outcome scores across standard CBT and CTMC sessions and Figure 2 shows the progress on the Y-BOCS across these two treatment conditions. The reduction in David's score on the clinician rated YBOCS was most prominent, from the severe range (32–40) at assessment (35) to the non clinical range (0–7) by his last session (7). His score had only slightly increased by 6-month follow-up (8) to just fall within the mild range (8–15). David's score on the OCI at the start of treatment (53) had increased since his initial assessment at the clinic (47). By his last treatment session his score (32) fell below the clinical cut-off of 40, and despite increasing slightly at 6-month follow-up (38) continued to be below the cut-off.

Table 2. David's outcome scores on all measures comparing intervention 1 (standard CBT) with intervention 2 (CTMC)

* please note there are no outcomes for session 5 standard CBT and session 11 CTMC

Figure 2. Chart to show change on the YBOCS and WASA across CBT treatment and CTMC

On the VOCI-MC, David's score continues to fall above the estimated cut-off of 20 throughout his treatment and at follow-up, but does fall from 38 at the first session to 29 at the last session. Of interest, David's score on this measure increases around session 5 to 46 before reducing again. This is discussed later.

In terms of more general depression and anxiety scores, at the final session David's depression score (10) fell at the bottom end of the moderate range (10–14), was in the mild range at the first booster session (7), but had increased to the moderately severe range at the last session (17). He attributed this to being unable to find work. His general anxiety scores (GAD-7) stayed within the mild range (5–10) across the final sessions and booster sessions compared to being in the severe range at the start of treatment. Finally, David's score on the WASA fell to 16 at the final session and 20 at both follow-ups, which had significantly reduced compared to the start of treatment and early sessions (35, 39). He viewed his low mood rather than his OCD as impacting on his functioning at the end of treatment.

Discussion

There is a growing body of empirical evidence suggesting that the phenomenology of mental contamination may include important differences to other types of OCD both in terms of the link to past experience of betrayal and the differences in clinical presentations. This single case study further illustrates these developments and goes on to show how an empirically and theoretically grounded intervention (focused cognitive therapy with imagery re-scripting) led to significant changes in symptomatology where a more conventional high quality CBT intervention had not.

David's case illustrates many of the proposals Rachman has made about mental contamination and the need to target the underlying problem through cognitive interventions (Rachman, Reference Rachman2010). Rachman talks about negative life events, such as betrayals or violations, being life “altering” events (Rachman, Reference Rachman2010). It was hypothesized that David's appraisal of these events was key in the development of his mental contamination. David viewed the people involved in these events, including himself, to be polluted in some way and this led to his feeling disgusted and revolted when he recalled these memories. The authors’ hypothesized that he then made further appraisals when the affect of these memories was activated: that he was contaminated in the present moment and needed to wash. The phenomenon in PTSD of “affect without recollection” (Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000), where only the affect is experienced when a memory is activated, may in part explain why David did not always realise that his difficulties were being driven by distressing memories from his past and instead viewed the problem as one of the government being contaminated.

Following initial work early in treatment on his appraisals of feeling contaminated, David experienced a dramatic realisation in treatment that washing was not the solution to his problem, yet he was still unable to reduce washing at this stage. It is proposed that this could illustrate the need to work on the self-defining memories driving the distress. Imagery re-scripting was helpful here. This might fit with the proposal of David's memories being self-defining episodic memories, since episodic memories are mostly represented in the form of visual images (Conway, Reference Conway2005) imagery work is likely to be helpful in shifting the associated appraisals.

David had completed numerous courses of previous CBT without improvement and dropped out of a course of high quality standard CBT at the clinic after finding the treatment distressing. This is reflective of high drop-out rates that have been found in the literature (Foa et al., Reference Foa, Liebowitz, Kozak, Davies, Campeas and Franklin2005; De Hann et al., Reference De Haan, van Oppen, van Balkom, Spinhoven, Hoogduin and van Dyck1997). It is hypothesized that these treatments did not target the heart of the problem: the memories of betrayal that were leading to his appraisal of these situations as meaning he was contaminated in the moment thus motivated him to compulsively wash. This may be one illustration that ERP in the absence of cognitive work on the underlying memories is not helpful in such cases because it may re-kindle the association between the stimuli and the unmodified polluting memory, increasing distress and possibly strengthening the cognitive link. If it is the case that mental contamination might account for a proportion of patients in published studies that fail to recover or disengage from treatment, then if treatments could be adapted and made more palatable and effective, we might see fewer drop-out rates and improved outcomes in OCD treatment more generally. This indicates the importance for ongoing research in this area.

It is interesting to observe that David's OCI score was already low, and had fallen following stage one of the CBT treatment below the clinical cut-off score of 40, despite David reporting that he was engaging in obsessions and compulsions for 24 hours a day at this time. What is the discrepancy here? When we look at measures such as the OCI, around half of the questions around excessive washing are predominantly more focused on contact contamination concerns, such as “I avoid using public toilets because I am afraid of disease or contamination”, “I find it hard to touch garbage or dirty things”, “I think contact with bodily secretions (perspiration, saliva, blood, urine etc) may contaminate my clothes or somehow harm me”. David scored all of these items as “not at all” or “only a little” distressing. Therefore it would seem that this measure was not fully capturing the full extent of his difficulties. This suggests the importance of using mental contamination specific measures in assessing and treating people, such as the VOCI-MC on which David scored above the estimated clinical cut-off throughout. This discrepancy between the VOCI-MC and OCD measures focusing more on contact contamination has been observed by the authors in other clinical cases of mental contamination.

It is also interesting to observe that David's score on the VOCI-MC is not very high at session one CTMC, but then increases when given at mid-treatment before reducing again. This could in part be that David might not have realized certain items applied to him early on in treatment. At the start of treatment David was unaware that his memories were driving his problems; therefore he initially did not endorse items such as “having an unpleasant image or memory can make me feel dirty inside”, “I often feel dirty or contaminated even when I haven't touched anything” and “I often feel dirty inside my body”. However, as his understanding of his problems grew he later started to score higher on these items. This may highlight the importance of giving this measure at regular intervals during treatment. It may also indicate that further work on improving measures of mental contamination is important. It is also noteworthy that David's score at the end of treatment on the VOCI-MC, although reduced since the start of treatment, remained above the estimated clinical cut-off. Reasons for this are unclear. One theory might be that David's baseline score on the VOCI-MC (prior to betrayal events) might have been naturally high and future research could explore whether there might be a relationship between higher scores on the VOCI-MC in non-clinical samples and the likelihood of developing later mental contamination based OCD following significant life events.

The main strength of the present report is the way a serious failure of treatment was turned into a success by the application of new treatment strategies directly derived from an empirically grounded understanding of the nature of the problem being experienced (mental contamination). However, given that this is a single case design there is of course limited generalization possible to a wider clinical setting. Other limitations include the possible impact of the CTMC intervention, coming as it did in sequence with 6 sessions of more conventional CBT. Perhaps the novel therapy approach built on the previous work, and would not have worked without that preparation, not to mention the additional resource of having multiple therapists in this treatment. Much more research, both qualitative and quantitative, is needed in this area to support the propositions for understanding and treating mental contamination outlined here. We would encourage ongoing research particularly around critical life experiences prior to the onset of OCD, the nature of these memories in autobiographical storage, for example whether they are stored similarly to other “self defining memories” (Singer and Salovey, Reference Singer and Salovey1993), and the presence of appraisals relating to the person/s involved being physically or morally polluted.

In summary, this case illustrates the successful clinical application of a cognitive treatment approach specifically tailored for application with mental contamination, after several high quality CBT treatments varying in intensity had been shown to be ineffective. This single case study forms part of a developing empirical grounding that highlights the importance of detailed assessment, in particular where there are past treatment failures, of contamination using measures to explore mental contamination such as the VOCI-MC. We suggest that in cases such as David's, behavioural exposure in the absence of adequate cognitive work is unlikely to be effective and could increase distress and cognitive links between feared stimuli and unmodified pollution memories. Therefore, this paper emphasizes the importance of using predominantly cognitive interventions to treat this predominantly cognitive disorder. An obvious next step is to identify and treat a consecutive series of such patients and evaluate outcomes in ways similar to that done here.

Acknowledgments

With many thanks to David: for his hard work and defiance. Thanks also to our colleagues at the clinic.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.