Introduction

Violence against women is considered to be a serious public health problem (Garcia-Moreno & Watts, Reference Garcia-Moreno and Watts2011) that affects millions of women around the globe. Worldwide, one in every three women have reported suffering violence at the hands of men (Devries et al., Reference Devries, Mak, Garcia-Moreno, Petzold, Child and Falder2013). A World Health Organization (WHO) multi-country study reported that more women in the Asian regions face intimate partner violence than in other parts of the world (WHO, 2005). The known phenomenon of under-reporting of violence against women may have suppressed the true prevalence. Global collective efforts to eliminate, or at least reduce, the extent of violence against women have not yielded positive results. Indeed, there is evidence that violence against women persists in all parts of the world (Heise & Garcia-Moreno, Reference Heise, Garcia-Moreno and Krug2002). The United Nations resolution for eliminating all forms of discrimination and violence against women has not yet been truly achieved. However, targeted interventions have helped communities reduce violence against women in several countries. Local interventions that consider the local context have been more successful than large-scale programmes.

Research on spousal violence has asserted that its major risk factors are low education levels or illiteracy of women and their husbands (Erten & Keskin, Reference Erten and Keskin2018; Chauhan & Jungari, Reference Chauhan and Jungari2020), husband’s alcoholism or substance use (Wagman et al., Reference Wagman, Donta, Ritter, Naik, Nair and Saggurti2018), gender inequality (Gibbs et al., Reference Gibbs, Corboz and Jewkes2018), lower social status of women (Mahapatro et al., Reference Mahapatro, Gupta and Gupta2012), patriarchy and power relations within the family (Abeya et al., Reference Abeya, Afework and Yalew2011), poor socioeconomic conditions (Ribeiro et al., Reference Ribeiro, da Silva, Alves, Batista, Ribeiro and Schraiber2017; Chauhan & Jungari, Reference Chauhan and Jungari2020), lack of employment and certain community factors. Early marriage contributes greatly to the increase in incidence of violence against women, with women who marry early being at higher risk of violence (Raj et al., Reference Raj, Gomez and Silverman2014).

A study in Afghanistan found that women whose husbands had more than one wife were more likely to experience all forms of violence (Gibbs et al., Reference Gibbs, Corboz and Jewkes2018). Women who justify violence against women have also been shown to experience higher rates of violence (Doku & Asante, 2015). Women justifying the violence that they are subjected to, by their partners or the community, is an indication of the normalization of violence, with women being conditioned to accept violence. It has also been shown that men with more controlling behaviour, men who are patriarchal in their attitudes and practices (Jewkes, Reference Jewkes2002; Fuluet et al., Reference Fulu, Jewkes, Roselli and Garcia-Moreno2013) and those who use substances (Fulu et al., Reference Fulu, Jewkes, Roselli and Garcia-Moreno2013) are more likely to perpetrate spousal violence. In South Asian countries, the preference for sons over daughters is deep-rooted, and often leads to denial of basic nutrition and health care for girls (Fikree & Pasha, Reference Fikree and Pasha2004; Mehrotra, Reference Mehrotra2006; Pande et al., Reference Pande, Nanda, Bopanna and Kashyap2017).

A review of the literature reveals that the various risk factors for violence operate differently in different cultural and contextual settings. Some studies report that women engaged in salaried jobs experience less violence, but others have found that such women in fact experience more violence (Swanberg et al., Reference Swanberg, Macke and Logan2007; Chin, Reference Chin2012).

Violence against women cannot be understood in simple terms, such as the influence of various risk factors. It is the outcome of a complex combination of complicated several factors that makes women vulnerable to violence (Raj et al., Reference Raj, Gomez and Silverman2014; Gibbs et al., Reference Gibbs, Corboz and Jewkes2018). Several qualitative studies have also found that a host of complex situations force women to remain in violent marital relationships for long periods (Evans & Feder, Reference Evans and Feder2016). Many women report staying married for the sake of their children, fear of their community or because they have no other option than to continue living with their violent husbands (Finnbogadóttir et al., Reference Finnbogadóttir, Dykes and Wann-Hansson2014). It is also widely accepted that women’s economic dependence on their husbands increases their vulnerability to violence.

Violence against women has several detrimental consequences that have been documented in various studies. Women who experience violence may suffer from more mental instability, anxiety and mental disorders, and be more prone to suicide (Ellsberg et al., Reference Ellsberg, Jansen, Heise, Watts and Garcia-Moreno2008; Devries et al., Reference Devries, Watts, Yoshihama, Kiss, Schraiber and Deyessa2011). In addition, they are more likely to have poor health status (Decker et al., Reference Decker, Peitzmeier, Olumide, Acharya, Ojengbede and Covarrubias2014) and less likely to utilize health care services (Stokes et al., Reference Stokes, Seritan and Miller2016), as well as suffer from stigma. Lack of timely medical treatment for serious injury could even cost a woman her life. Women victims of violence are also more likely to have a poor quality of life (Loke et al., Reference Loke, Wan and Hayter2012) and bond poorly with their families.

Recent studies of violence against women have estimated the economic cost of violence at the community level. Pregnant women who experience violence have more severe health consequences, such as premature delivery, low birth weight babies, abortions and poor breastfeeding practices (Sørbø, Reference Sørbø, Lukasse, Brantsæter and Grimstad2015; Baker et al., Reference Baker, Story, Walser-Kuntz and Zimmerman2018). Women who experience violence in their homes are at higher risk of partner violence during pregnancy (Jungari, Reference Jungari2018). This could mean that a large proportion of women may be experiencing violence during pregnancy.

Afghanistan has been experiencing serious problems of internal insecurity and conflicts, and political instability, for several decades. The consequences of this unrest have been especially severe for Afghanistan’s women, whose lives are controlled and tightly restricted. The loss of freedom has made them more vulnerable to abuse and violence. In fact, violence against women has become normalized, often justified as a means of ‘controlling’ them (Abirafeh, Reference Abirafeh2007; Hennion, Reference Hennion2014). Historically, Afghanistan’s women have experienced gender bias, but now they are also the victims of political war (Abirafeh, Reference Abirafeh2007; Sikweyiya et al., Reference Sikweyiya, Addo-Lartey, Alangea, Dako-Gyeke, Chirwa and Coker-Appiah2020).

Various studies have reported high rates of violence against women in Afghanistan. Qualitative as well as quantitative studies have highlighted the extent of women’s suffering (Mannell et al., Reference Mannell, Ahmad and Ahmad2018). It is estimated that about 50% of Afghan women have experienced intimate partner violence in their lifetime (Nijhowne & Oates, Reference Nijhowne and Oates2008), but there is wide variation in its prevalence within the country: from 6% in Helmand and 7% in Badakhshan provinces to 92% in Ghor and Herat provinces (Central Statistics Organization, 2016). A recent Demographic and Health Survey found that about 52% of Afghan women in the reproductive age group had experienced violence (Central Statistics Organization et al., 2017).

The risk factors found to be associated with intimate partner violence in Afghanistan include early marriage, gender inequity, women’s poverty and low education levels, and the widespread acceptability of intimate partner violence (Nijhowne & Oates, Reference Nijhowne and Oates2008; UNFPA, 2016). The persistence of violence against women in Afghanistan is a serious problem for the country’s efforts at empowering women and poses a serious threat to Afghanistan’s development in a post-conflict era.

Few studies have attempted to understand the prevalence of violence against women in Afghanistan and its risk factors (Hennion, Reference Hennion2014). Those that have been conducted have been in small settings with limited sample sizes and nationally representative insights are not available (Gibbs et al., Reference Gibbs, Corboz and Jewkes2018). The aim of the present study was to utilize a large nationally representative sample of currently married Afghani women to examine the relationship between spousal violence and socioeconomic factors, along with multidimensional features of gender inequality.

Methods

Data

The study used data from the 2015 Afghanistan Demographic and Health Survey (2015 AfDHS) conducted jointly by the Central Statistics Organization (CSO) and the Ministry of Public Health (MoPH) from 15th June 2015 to 23rd February 2016. The 2015 AfDHS is a national sample survey that provides recent information on fertility levels, marriage, fertility preferences, awareness and use of family planning methods, child feeding practices, nutrition, adult and childhood mortality, awareness of and attitudes towards HIV/AIDS, women’s empowerment and domestic violence. The target groups for the survey were women and men aged 15–49 years from randomly selected households across Afghanistan.

The 2015 survey drew a stratified two-stage cluster sample of 950 (260 in urban areas and 690 in rural areas) units from Afghanistan’s 34 provinces for estimation of key national-level indicators. The sample was drawn from an updated version of the Household Listing Frame, which was first prepared in 2003–04 and updated in 2009, provided by the CSO. In the second stage, households were selected systematically. A fixed number of 27 households per cluster was selected through an equal probability systematic selection process. To mitigate the issue of difficult-to-reach households because of the ongoing security issues, 101 reserve clusters were selected in all provinces to replace the inaccessible clusters. Over 70 of the selected clusters were found to be insecure during household listing, so a house listing operation was also carried out in all 101 pre-selected reserve clusters. Household listing was successfully completed in 976 of the total of 1051 clusters and the survey was successfully carried out in 956.

A total of 25,741 households were selected, of which 24,941 were found to be occupied during fieldwork. Of the households that were occupied, interviews could be conducted in 24,395 – a response rate of 98%. In these households, 30,434 ever-married women aged 15–49 years were identified for personal interviews, which were completed for 29,461 – a response rate of 97%.

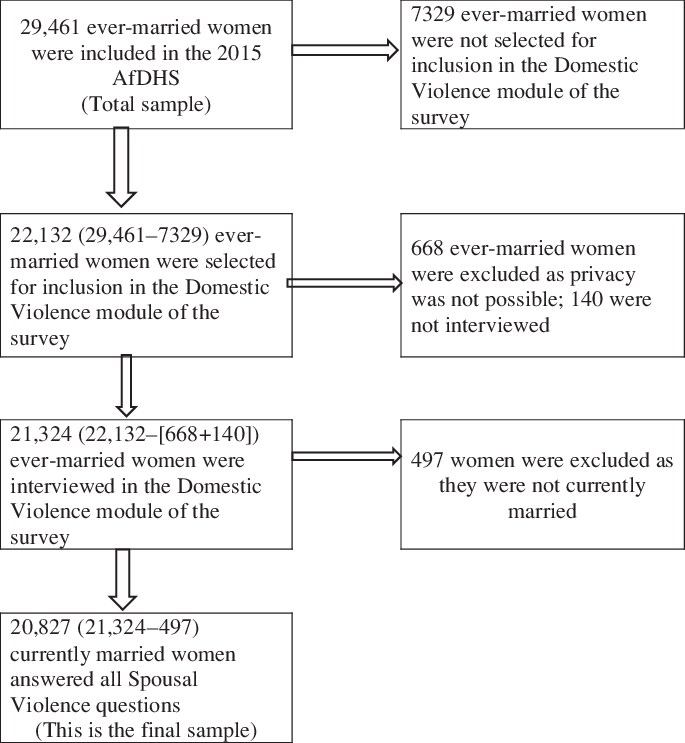

The 2015 AfDHS had three questionnaires. These were initially drafted in English and then translated into Dari and Pashto. The survey protocol and questionnaires were approved by the ICF Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the Ministry of Public Health of Afghanistan. The domestic violence module was a relatively new addition to the 2015 AfDHS. In accordance with WHO guidelines for the ethical collection of information on domestic violence, one eligible woman per household was randomly selected for participation in this module. A total of 21,324 ever-married women were selected for data collection on domestic violence and interviewed. About 4% of eligible women could not be interviewed for various reasons. The present analyses only included currently married women aged 15–49 years, and the sample size was 20,827. The selection process for arrival at the final sample size is explained in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Selection of the study sample from the 2015 Afghanistan DHS.

Outcome variable

The primary outcome variable was ‘spousal violence against a wife’. Perpetration of spousal violence by a husband was assessed using twelve survey items. In the 2015 survey, questions on physical spousal violence were asked before introducing those on emotional and sexual violence.

If a woman’s husband engaged in one or more of the following the woman was classified as experiencing ‘physical violence’: 1) pushed, shook or threw something at her; 2) slapped her; twisted her arm or pulled her hair; 3) punched her with his fists or hit her with something that could hurt her; 4) kicked her, dragged her or beat her up; 5) tried to choke or inflict burns on purpose; 6) threatened harm or attacked her with a knife, gun or any other weapon. A ‘yes’ answer to any of these questions was given a score of 1 and the respondent was classified as experiencing physical violence; responding ‘no’ to all questions was scored 0, indicating that there was no physical violence.

Women who reported that their husbands engaged in any of the following behaviours were classified as having experienced ‘sexual violence’: 1) physically forced her to have sexual intercourse with him when she did not want to; 2) physically forced her to perform any other sexual acts that she did not want to; and 3) used threats or other forms of intimidation to make her perform sexual acts that she did not want to. A ‘yes’ to any of these questions was given the score 1 and the women was classified as experiencing sexual violence; if she answered ‘no’ to all the questions she scored 0 and was classified as having experienced no sexual violence.

The prevalence of ‘emotional violence’ was assessed from the women’s responses to questions on their husband’s behaviour. If she reported that her husband 1) said or did something to humiliate her in the presence of others; 2) threatened to hurt or harm her or someone she cared about; 3) insulted her or made her feel bad about herself, this was considered as emotional violence. A response of ‘yes’ to any of these was coded as ‘1’ to represent her experiencing emotional violence; otherwise, a code of ‘0’ indicated she experienced no emotional violence.

A composite variable was created to denote ‘any violence’, to include one or more forms of violence. ‘Any violence’ was defined as experiencing any physical, sexual or emotional violence. ‘No spousal violence’ (coded 0) was recorded if a respondent did not report experiencing any physical, sexual or emotional violence. For those who experienced any physical, sexual or emotional violence, a code of 1 was assigned to represent the event of experienced any spousal violence.

The recall period for responses to the questions was defined as ‘since the age of 15 years’. However, the data gave the freedom to estimate women’s experiences of all events of domestic violence in the last 12 months. As domestic violence is a very sensitive issue and responses may be influenced by ideology, there is the possibility of recall bias. To reduce this, the study focused on any kind of violence inflicted on currently married women by their husbands in the last 12 months.

Explanatory variables

Socioeconomic and demographic explanatory variables that have been theoretically and empirically linked to spousal violence were included in the study (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Schuler, Islam and Islam2004; Uthman et al., Reference Uthman, Lawoko and Moradi2009). These included respondent’s age, grouped into 15–19, 20–24, 25–29, 30–39 and 40–49 years; place of residence, categorized as rural or urban; household wealth index, categorized as poorest, poor, middle, rich, richest; and number of living children, grouped as 0, 1–2, 3–4 and 5 or more; education levels of women and their husbands, classified as no education, primary, secondary and higher; and women’s working status, classified according to whether they were currently working or not (working, not working). The media exposure variable had three categories depending on the frequency of reading newspapers/magazines, listening to the radio or watching TV: 1=not at all; 2=less than once a week; and 3=at least once a week. A response of ‘not at all’ to all three (print, radio and television) put respondents in the ‘not exposed to media’ category, with a code of 0. Exposure to any of the three indicators was considered ‘partial exposure’ and assigned a code of 1. ‘Full exposure’ was considered to occur if a respondent was exposed to all three types, and was coded 2.

Ethnicity of the respondents was categorized as Pashtun, Tajik, Hazara, Uzbek or other. Duration of cohabitation was coded as <5, 5–9 and 10+ years.

Women’s level of empowerment was assessed using two separate indices based on survey response information on their participation in household decision-making and attitudes towards wife beating. The first index was the number of household decisions in which the respondent was a participant, either on her own or jointly with her husband. This was developed from the women’s responses to questions on their own health care, large household purchases, visits to family or relatives and what to do with the money husbands earn. The value of the index ranged from 0 to 4, with a higher value meaning greater women’s empowerment, and reflects the degree of control women are able to exercise in decisions that affect their own lives, as well as their environment.

The second index, which ranged from 0 to 5, reflected the number of reasons for which wife beating was justified by respondents. This was calculated from responses to questions related to justifying wife beating: wife going out without telling her husband; wife neglecting the children; wife arguing with her husband; wife refusing to have sex with her husband; and wife burning the food. A higher value of this index can be interpreted as a more supportive attitude towards wife beating. It also indicates that a woman who believes that her husband is justified in beating his wife, for one or all of these reasons, may consider herself to be of inferior status both relative to that of her husband and in absolute terms.

Studies have suggested that disparity in education level, where the husband if considerably better educated, increases the chances of the husband exercising his dominance through violence (Hornung et al., Reference Hornung, McCulluogh and Sugimoto1981). However, there is also evidence that there is an increased risk of marital disagreement if a woman is better educated than her husband (Hornung et al., Reference Hornung, McCulluogh and Sugimoto1981; Ackerson et al., Reference Ackerson, Kawachi, Barbeau and Subramanian2008). Educational disparity between spouses was classified into four categories: 1) both wife and husband were literate; 2) only husband was literate; 3) only wife was literate; and 4) both wife and husband were illiterate. The couple’s desire for children was considered as an explanatory variable to assess the influence of gender inequality in decision-making. The number of children desired was defined and coded as: 1) both wanted the same number of children; 2) husband wanted more children than his wife; and 3) husband wanted fewer children than his wife.

The property ownership variable was constructed using women’s responses to the survey questions: ‘Do you own this or any other house either alone or jointly with someone else?’ and ‘Do you own any land either alone or jointly with someone else?’ If a woman reported not owning a house or any land this was categorized ‘does not own’ with a code of ‘0’. If a woman reported owning a house or some land on her own, this was categorized as ‘owns alone’ with a code of ‘1’. Similarly, if she reported owning a house or some land with someone else, this was considered ‘owns jointly’ with a code of ‘2’. If she reported owning some property alone and some jointly with someone else, this was classed ‘owns both alone and jointly’ and coded ‘3’.

Statistical analysis

The data were analysed using descriptive statistics and bivariate and multivariate regression techniques. Bivariate analysis used a chi-squared test to assess the associations between the outcome and independent variables. The univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to assess the association between the explanatory variables and the outcome variables. The results of the logistic regression analyses are presented as odds ratios (ORs) with 95 % confidence intervals (CIs). Statistical analysis were performed using Stata Version 13.0.

Results

Socio-demographic profile of respondents

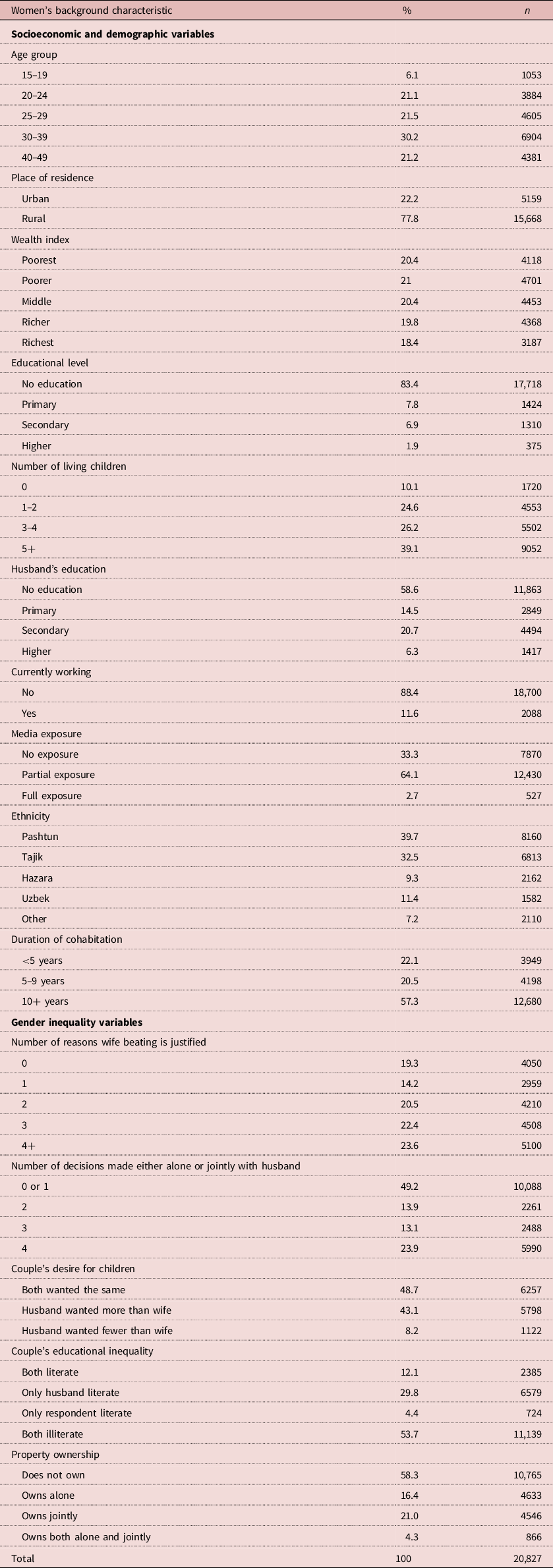

Table 1 shows the distribution of the sample women by socio-demographic indicators and gender inequality variables. The majority of the respondents (30.2%) were in the 30–39 year age group, followed by 21.5% in the 25–29 year and 21.2% in the 40–49 year age groups. Most (78%) lived in rural areas and only 18.4% belonged to the richest wealth quintile. The majority (83.4%) had no education and 39% had 5 or more children. Most of the women (88.4%) were not working and a third (33.3%) had no media exposure. Pashtun women comprised 39.7% of the sample. Over half (57.3%) of the women had been living with their current husband for 10 or more years. Wife beating was justified for four or more reasons by 23.6% of the women. Four or more decisions were made with women’s involvement, either singly or jointly. Less than half (48.7%) of respondents’ husbands wanted the same number of children as their wives did. The survey also found that 53.7% of the couples were illiterate.

Table 1. Distribution of currently married women aged 15–49 by socioeconomic, demographic and gender inequality variables, Afghanistan, 2015

Percentages were weighted and all ‘n’ values were un-weighted. Total may not be equal due to some missing cases.

Experience of spousal violence by background characteristics

Table 2 shows the results of the bivariate analysis of the prevalence of different forms of spousal violence by women’s background characteristics. A significant proportion of the women (45.9%) reported experiencing physical spousal violence; 34.4% emotional violence; and 6.2% sexual violence. Overall, 52% of the women reported experiencing all three forms of spousal violence.

Table 2. Prevalence of experience of different types of spousal violence by currently married women by background characteristics, Afghanistan, 2015

Chi-squared test was applied to calculate the association of significant (p-value). Percentages were weighted and all ‘n’ values were un-weighted. Total may not be equal due to some missing cases.

The prevalence of spousal violence increased with the age of the women, and was higher in urban than in rural areas. Physical violence, sexual violence and ‘any type of violence’ were all more prevalent among women in the poorest wealth quintile and those with no education, than among women in the other wealth quintiles and those who were literate. Also, as the number of children increased, so did the prevalence of spousal violence. Non-working women were less likely to report having experienced spousal violence than working women. Women with exposure to all types of media were less likely to be abused in any way (physically, emotionally or sexually) than women with partial or no exposure to any form of media. Physical and other forms of violence were prevalent among Pashtun women, and those who had lived with their husbands for 10 or more years.

Women who participated in four or more decisions, either singly or jointly, who tended to justify wife beating less in comparison to women from the corresponding categories. Agreement between spouses on the number of children they wanted also considerably reduced the chances of violence. Spousal violence was significantly more frequent if both the woman and her husband were illiterate.

Predictors of spousal violence

Table 3 shows the results of the multivariate analysis of the association between women’s experience of spousal violence and background variables. Crude and adjusted odds ratio were calculated to determine the adjusted and unadjusted effects of the independent variables on dependent variables. In the adjusted logistic regression, the women’s and their husbands’ education levels were excluded from the analysis due to multi-collinearity with the educational inequality variable. The crude (COR=2.180; CI=2.000–2.377) and adjusted (AOR 1.938; CI=1.727–2.174) regression models indicated that there was a significantly higher risk of spousal violence with a greater number of reasons for justifying wife beating. The highest risk was for the category ‘four or more’. Also, woman’s involvement in decision-making in the household was a strong predictor of spousal violence. In the crude model, women who had participated in four decisions, either singly or jointly with their husbands, were 53% (COR=0.476; CI=0.446–0.509) less likely to experience spousal violence. Even after adjustment for demographic and socioeconomic factors, women who participated in all four decisions, either singly or jointly with their husbands, were still at lower risk of spousal violence (AOR=0.472; CI=0.431–0.516). In both the crude and adjusted models, a woman was at lower risk of spousal violence if her husband’s desired number of children was different from her own.

Table 3. Odds ratios (OR) and 95 % confidence intervals (CI) for factors associated with any form of spousal violence against currently married women, Afghanistan, 2015

Ref.=reference category; COR=crude odds ratio; AOR=adjusted odds ratio; CI=95% level of confidence interval.

Levels of significance: *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

In the crude model, compared with women and husbands who were literate, all education inequality categories (illiterate women whose husbands were literate, literate respondents with illiterate husbands, and illiterate couples) had an increased risk of spousal violence. After adjusting for demographic and socioeconomic variables, the strength of the association diminished but remained significant when only the respondent was literate, or when both spouses were illiterate. As for property ownership, the risk of spousal violence was significantly higher (COR=1.263; CI=1.178–1.353; AOR=1.159; CI=1.051–1.278) when women jointly owned property compared with when they did not own property. In both the crude and adjusted models, the risk of spousal violence was less when women owned property, either alone or jointly, compared with when they did not own any property. In the adjusted model, however, the relationship was not significant.

In both the crude and adjusted models, the prevalence of any spousal violence was higher among older women than those aged 15–19 years. The odds of prevalence of any type of violence were higher in rural than in urban areas (COR=1.562; CI=1.46–1.66; AOR=1.420; CI=1.259–1.601). The risk of spousal violence was 18% (AOR=0.824; CI=0.696–0.975) less for women in the richest category compared with their counterparts in the poorest. Interestingly, working women were more likely to experience spousal violence than those who were not working. This was true in both the crude and adjusted models, though the odds of any spousal violence were higher in the adjusted model.

Another finding of interest was that the risk of spousal violence was higher among women who had partial or full media exposure compared with those who had not media exposure. This was true in both the crude and adjusted models. Duration of cohabitation was significantly positively associated with spousal violence in both the adjusted and unadjusted models.

Discussion

This study used national AfDHS 2015 data to determine the prevalence of spousal violence among Afghan women. The results showed that more than half (52%) of the women surveyed reported experiencing some form of violence. About 46% suffered from physical violence, 34.4% were subjected to emotional violence and 6.2% had experienced sexual violence. The prevalence of spousal violence in Afghanistan in 2015 was higher than rates reported in some South Asian countries, such India, Pakistan, Nepal and Sri Lanka (Kalokhe et al., Reference Kalokhe, del Rio, Dunkle, Stephenson, Metheny, Paranjape and Sahay2016; Guedes et al., Reference Guedes, Bott, Garcia-Moreno and Colombini2016). There are several possible reasons for the higher rates of violence against women in Afghanistan: early marriage, gender inequality and the normalization of violence against women in Afghan society (Gibbs et al., Reference Gibbs, Corboz and Jewkes2018; Metheny & Stephenson, Reference Metheny and Stephenson2019).

The prevalence of spousal violence was greater among women who justified wife beating. This has been shown to be the case in many other countries, with many studies reporting that women who justify the violence inflicted by their husbands experiencing greater violence (Tran et al., Reference Tran, Nguyen and Fisher2016; Jungari & Chinchore, Reference Jungari and Chinchore2020). The likely reasons are: 1) a woman’s lack of awareness of her rights and 2) conditioning by her family from an early age that women must expect punishment from males for the smallest ‘mistakes’. Long-term interventions are needed to educate and empower Afghani women so that they can realize their rights and entitlements, exercise full control over their bodies and know that spousal violence is unjustifiable.

The study further revealed that women’s participation in decision-making, either alone or jointly with their husbands, was significantly associated with spousal violence. Women who participated in household decision-making experienced less violence than those who did not participate in them. Day-to-day gender dynamics within households have a greater influence on women’s vulnerability, influencing the prevalence of spousal violence. Other studies have reported similar findings on the association of women’s participation in decision-making processes and violence (Kalita & Tiwari, Reference Kalita and Tiwari2017).

The risk of violence was found to be higher if there was disagreement between spouses over the number of children they wanted. Women were more vulnerable to abuse by their husbands when they wanted fewer or more children than their husbands (Chauhan & Jungari, Reference Chauhan and Jungari2020). This can be interpreted as a lack of autonomy of women over their reproductive behaviours. Furthermore, women without an education, and those from poor socioeconomic households, as well those in unions where both spouses were illiterate, were at an elevated risk of spousal violence. Many studies in Afghanistan and other Asian countries have arrived at similar conclusions (Ferguson, Reference Ferguson2018; Gibbs, et al., Reference Gibbs, Corboz and Jewkes2018). Educating women can significantly reduce their vulnerability to violence, so increasing the enrolment of girls in schools and keeping them there, and facilitating their higher education, are essential. Evidence from studies in many countries suggests that empowering women and encouraging their participation in economic activities could also reduce their vulnerability to violence (Noble et al., Reference Noble, Ward, French and Falb2019), so interventions need to be designed to reduce women’s economic dependence on their partners and empower them (Wu, Reference Wu2019).

The present study did not find a clear association between ownership of property and the risk of spousal violence. It can be argued that an association between property ownership and a reduced risk of spousal violence could be due to woman’s control over economic resources enhancing their ability to exercise choice. The obvious benefit is that having control over resources may give her the ability to balance the costs and benefits of alternative uses of resources so that they may be employed in the most efficient manner (Smith, 1995). Also, the more the control she has of economic resources, the more likely she is to challenge the acceptability of partner violence, and increase her social support through the mobilization of new and existing community groups (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Watts, Hargreaves, Ndhlovu and Phetla2007)

The study results indicate that high levels of spousal violence in Afghanistan make it impossible for the country to achieve the Sustainable Developmental Goals (SGDs), particularly those related to women’s health. Urgent effort is needed from local, national and international organizations and the Afghan government to undertake appropriate interventions to reduce violence against women if the SDGs are to be achieved. In resource-poor countries such as Afghanistan it is always a matter of allocating resources to women’s issues, particularly women empowerment, which will ultimately improve women’s status.

The study has its limitations. Being cross-sectional, exact temporal relationships could not be examined. Also, as the study used secondary data, the impact of social and cultural covariates could not be adequately examined. The outcome variable ‘spousal violence’ relied on self-reporting by women and some response bias was likely. Furthermore, the acceptance of wife beating by the women was measured from the responses to close-ended questions. Hence, attitudes of the women towards this practice could not be probed.

In conclusion, the reported high levels of spousal violence against women in Afghanistan is a serious public health problem that calls for immediate policy and legal actions by the government. There is an urgent need for the empowerment of Afghani women through better access to education and opportunities for participation in economic activities. However, this alone is not enough to protect women from violence by their husbands; women must be made aware of their rights, and their husbands sensitized to accepting that their wives have equal rights. Efforts are being made at the national and international level to end violence against women in Afghanistan, with recent large protests in the capital Kabul. More qualitative and quantitative studies are needed to fully identify the factors associated with intimate partner violence. These should include the investigation of the perceptions and attitudes of the perpetrators of the violence to inform the design and planning of appropriate interventions to educate and sensitize Afghan men on the issue.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial entity or not-for-profit organization.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Ethical Approval

This analysis was based on the Demographic and Health Survey data from Afghanistan available in the public domain. The data can be downloaded from www.DHSprogram.com. The study conducted a secondary analysis with no identifiable information on survey respondents.