Debates about the challenges of Muslim integration in Germany are pervasive. Angela Merkel's recent pronouncement that multiculturalism has failed is only one of the latest declarations in a long line of similar sentiments generally informed by an understanding of Muslim culture as unchanging and insurmountably different, and at odds with German liberal values. Sexual and gender-based mores have been repeatedly cited as the primary reason for this incompatibility. We might note, for example, the 2005 efforts by Baden-Württemberg and Hesse to impose citizenship tests on Muslim applicants with questions about gender and sexuality; the recent campaigns by such figures as Necla Kelek and Sayran Ates accusing Germans of being too tolerant of Muslim Turks’ poor treatment of women; or Alice Schwarzer's 2010 publication Die große Verschleierung (The Great Cover-Up), advocating the banning of the headscarf. The popular press and political discourse offer numerous other examples. Scholarly treatments have provided a more nuanced assessment of the evolution of attitudes on the issue; a number of studies have usefully noted the strongly gendered construction of these arguments, especially the ways in which Muslim women have become the ‘other’ within Germany. Most of this scholarly literature focuses on the guestworker integration debate from the 1970s onwards. It is important to understand, however, that debates about German–Muslim relations centring on issues of sexuality, gender and marriage began much earlier, in the 1950s – a fact recognised in neither the scholarly literature nor popular debates.

A growing body of work has insightfully illustrated that, while older notions of biological racism became taboo after Nazi Germany's defeat, concepts of cultural difference prevailed.Footnote 1 Rita Chin and Heide Fehrenbach are among those who have noted that post-war concepts of cultural difference, while avoiding arguments based on genetic notions of incompatibility, nevertheless justified discrimination on political, legal and economic grounds. The politics of exclusion engendered by this way of thinking have led Chin and Fehrenbach to insist that ‘Questions of race and difference should be mainstreamed in historical inquiry and recognised as central to the larger political, social and cultural articulation of national and European identities, institutions, economies and societies’.Footnote 2 Scholars who have researched Muslim guestworkers in Germany have embraced this approach, showing that the presence of foreigners challenged long-held views of Germany as ethnically and culturally homogenous and therefore central to the process of (re)negotiating post-war German identity.Footnote 3 Ruth Mandel, Karin Hunn and Rita Chin, for example, have explored shifting ideas about hierarchies of difference as central to national identity in the post-war period, particularly in the context of the Turkish diaspora in Germany.Footnote 4 As their studies have shown, Turks emerged as the quintessential ‘other’ from the 1970s, when it became clear that an increasing number of those who had come to Germany as guestworkers were bringing spouses and children and intending to settle. The ensuing debates about integration revealed a German understanding of culture as largely unchanging and essential, thus positing as impossible the idea that former guestworkers and their families could ever be considered fully ‘German’.

Esra Erdem, Monika Mattes, Katrin Sieg and others have also postulated that subsequent debates about integration show how central gender became in marking migrants with a Muslim background (most of them of Turkish origin) as ‘other’ in the wake of the recruitment ban in 1973.Footnote 5 Islam came to be understood as a religion that not only allowed but also mandated the victimisation of women by patriarchal pashas. It was this aspect of Islam more than any other that became the demonstration par excellence of the impossibility of Muslim integration into German society. And yet, it is important to note that while ideas about the supposed unchanging qualities of Islam and the inherent incompatibility of Muslim and German identities in the post-war period have persisted over decades, the precise manifestation of the sites of contestation have changed quite dramatically.

Ideas and tropes about Muslim–non-Muslim sexual relationships forged between the late 1950s and the early 1970s emphasised inherent differences between these two communities, especially as manifested in marriages that challenged traditional German mores. These ideas have proved to have remarkable staying power. Yet it is essential to recognise that this earlier period differed from the subsequent, more familiar (and more thoroughly studied) periods in three fundamental ways. First, before the 1970s, the Muslim foreigners in question were students and interns from Africa and the Middle East who were in Germany temporarily and entered relationships with German women, not guestworkers and their descendants who settled in Germany. Second, in this earlier discourse, it was German Christian women – specifically those who moved abroad after their marriage to Muslim foreigners – and not foreign Muslim women in Germany who were the presumed victims of Muslim men. Finally, the earlier discourse about Islam (prior to the 1970s) was strongly shaped by national church institutions charged with the welfare of these German Christian women, while the discourse since the 1980s has been located primarily within the public political realm. Giving due attention to the context in which concerns about Christian–Muslim romantic relationships were initially articulated in post-war Germany allows us to understand the roots of popular attitudes about Islam as incompatible with Western enlightened values and therefore in conflict with German democracy. It also encourages us to acknowledge that these ideas were formed in a context fundamentally different from that of subsequent decades.

The social and legal framework informing the debate

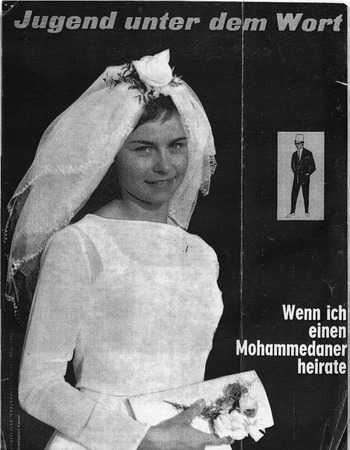

In May 1962, a very young-looking German bride in a white wedding gown smiled from the cover of the Christian girls’ magazine Jugend unter dem Wort (Youth Under the Word), boldly contemplating: ‘When I Marry a Mohammedan’ (see Figure 1).Footnote 6 Though he was far less prominent than the German bride, the same magazine cover also depicted the presumed Muslim groom: a small, cartoonish caricature of a man sporting a double-breasted suit and tie, sunglasses and a fez. A tool-wielding blue-collar worker he is not. The issue of Jugend, largely dedicated to Muslim–Christian romantic relationships, made it abundantly clear that the Muslim men that were of most concern to those who considered themselves the protectors of innocent young German women were not guestworkers but Muslim men studying at German universities. As articles within the magazine made clear, Jugend's editors and writers cautioned against the cover-girl's marital ambitions, citing experts who considered her desires highly misguided and naive, if not foolishly dangerous.

Figure 1. The May 1962 cover of Jugend unter dem Wort

Source printed with permission of the Archiv für Diakonie und Entwicklung, Berlin, HGSt 6049. Despite my best efforts to pursue image rights, I have been unable to identify or contact the copyright holder.

Jugend's publishers were not the only ones who noted with concern the trend of a growing number of German women and girls wanting to marry ‘Mohammedans’. By the early 1960s a number of Christian charitable organisations, working in conjunction with the West German state to counsel prospective emigrants, spearheaded information campaigns on intermarriage. As the May 1962 Jugend cover suggests, these organisations were preoccupied with the welfare of German women who seriously considered marrying a Muslim and moving to the husband's home country. Indeed, the individuals who led and wrote for these organisations considered themselves German women's advocates, the would-be brides’ protectors against men who embodied a religion (Islam) and culture (‘Oriental’) that was inherently different from the women's own German, Christian upbringing. An examination tracing the interethnic marriage debate through the documents created and widely disseminated by these organisations shows how church-run welfare organisations, supported by the state, actively shaped attitudes about religion, race and difference in post-war Germany. These ideas persisted well beyond the period and contexts in which these organisations framed the discourse. Indeed, many of these views have continued to live on in largely secular discussions about German and Muslim identity. They have retained their currency even as the views of the religious organisations that originally promoted them evolved beyond these essentialist views, and as the organisations themselves receded as influential shapers of popular discourse about intermarriage and German identity.

When the May 1962 special issue of Jugend appeared, more than 700,000 foreigners were employed in Germany, over 180,000 of them of Turkish origin (the rest being mainly southern Europeans); but the Muslims discussed in relation to interethnic marriages were not primarily guestworkers.Footnote 7 Rather, they were part of a small group of approximately 7,400 students from Africa and the Middle East attending German universities.Footnote 8 Certainly, the presence of guestworkers in Germans’ midst also generated much debate, especially when relationships with German women were involved.Footnote 9 The public image of Mediterranean labourers focused on their supposed hot-bloodedness, sexual prowess and gallantry, which made them exceedingly attractive to German women, who were apparently used to ‘coarser fare’ from their German suitors.Footnote 10 Yet the state and the churches were most keenly focused on the non-European, and initially non-Turkish, Muslim male population who were seen as seducing German women and luring them into miserable lives in the Middle East as wives subject to violent treatment at the hands of Muslim men.

To a certain extent, living arrangements and national origin can help explain state and church officials’ apparently disproportionate concern about German women marrying Muslim men, and Muslim students in particular. As noted, in the early 1960s, the number of Turks in Germany was still comparatively small; most guestworkers at the time were southern Europeans. Moreover, guestworkers lived rather circumscribed lives that afforded fewer opportunities to forge relationships with German women. They worked primarily in male-dominated sectors of the economy, such as the iron and metal industry, and in construction, and the vast majority of them lived in dormitory-style living quarters.Footnote 11 In contrast, foreign students often sought and secured private housing, and the university environment facilitated mingling with German peers.Footnote 12 Many German commentators thus viewed Muslim students as more likely potential spouses for German women, and hence more threatening. Indeed, the very fact that male Muslim students shared a campus environment, and that they had respectable educational, financial and career aspirations, threatened to make these Muslim men seem attractive to young German women as prospective husbands. As we will see, post-war public information campaigns often sought to reveal the presumed hidden, immutable character of Muslim men that was purportedly masked by their superficial adoption of some German behaviours and customs. Without such efforts, German state and religious authorities feared that the core character of a prospective Muslim groom might remain hidden until it was too late, after an innocent young German woman was already irretrievably trapped: married to an abusive Muslim man and living in an oppressive Muslim society abroad that condoned his violence against her. With their public information campaigns, the Christian organisations set out to save German women from this fate.

The organisations that mounted the public information campaigns were responding to some real demographic, legal and social conditions. More German women than German men married foreigners. This trend continued until 1995, when, for the first time, more German men than German women married foreigners.Footnote 13 It is also crucial to recognise that, even when a German woman and a Muslim man met in Germany, it was widely assumed that the German woman would leave Germany to reside in her prospective husband's home country. Indeed, various laws made such women's emigration almost a foregone conclusion. Before 1953, German women lost their citizenship upon marriage to a foreigner. Although an equality statute passed in 1957 officially eliminated the automatic loss of citizenship in such a way, implementation was slow; legal gender equality would be a decades-long process. While naturalisation of foreign women marrying German men became a mere formality the same year the equality statute was passed, the same was not true for foreign men marrying German women.Footnote 14 In 1969, the naturalisation and citizenship law was revised, so that neither foreign men nor foreign women were able to gain German citizenship automatically upon marriage, though the general process of naturalisation was overall made easier, as long as the prospective immigrants met certain conditions.Footnote 15 Moreover, until 1975, the children of interethnic couples received the father's citizenship, creating major problems for German women in cases of divorce and child custody battles.Footnote 16 It was not until 1986 that the reform of the Private International Law (which governs litigation when laws of different countries conflict, as is the case in intermarriages) came into effect; before then, in cases of divorce, spousal support and child custody, the law of the husband's country had generally prevailed. Finally, until 1975, the marriageable age for German women was sixteen (in contrast to twenty-one for men), which also helps to explain the heightened concern and doubt about whether the prospective brides in question were sufficiently informed and mature enough to make such an important and permanent decision as marrying a foreigner.Footnote 17

Because German women who married foreigners were expected to leave Germany and reside in their husbands’ home countries, questions of interethnic marriage were principally taken up by departments and institutions that focused on providing guidance on emigration rather than immigration. Such offices were key in informing, organising and counselling on the topic of interethnic, international marriage – referred to in the German literature as bikulturelle (bicultural), binationale (bi-national), gemischt-nationale (mixed-national) or Mischehe (mixed marriage), as well as Ehe mit Ausländern (marriage with foreigners). Within the prevailing social and legal context, Christian charitable organisations were the principal state-sanctioned institutions offering counselling for prospective emigrants, including women considering marriage to a foreigner. Especially prominent were the Department of Migration of the Protestant social welfare organisation, Diakonie, and the Catholic association St Raphaels-Verein (later renamed Raphaels-Werk). These institutions already had a long history of aiding foreigners in Germany and Germans planning to go abroad, reaching back to the mid- to late-nineteenth century. During the Weimar Republic, they had formalised their collaboration with the German state to provide social services; they renewed that co-operation in the post-war period.Footnote 18 These organisations were instrumental in providing support and Betreuung (assistance) for guestworkers in West Germany from the mid-1950s onwards to facilitate their transition to living (albeit supposedly only temporarily) in a new country and a new job. Their work with guestworkers is well known, if not yet fully analysed. Their efforts to counsel Germans who were contemplating marriage to foreigners, especially German women, has escaped attention entirely. Yet this function too was critical and provides fascinating insight regarding the construction of race, religion, gender and identity in post-war Germany.

The Christian lay organisations served as liaisons between state authorities represented by the Bundesverwaltungsamt – Amt für Auswanderung (Office of Emigration within the Federal Administration Office; hereafter BVA–AfA) and the public, including individuals seeking information and advice about marriage between Germans and non-Germans. The BVA–AfA provided a variety of educational materials, including bulletins that contained examples of Muslim marriage contracts and information about legal requirements for citizenship in various African and Asian countries. The office also distributed updates on policy and judicial decisions, newspaper articles on intermarriage, and accounts received from people who lived or had lived in the Middle East, usually with an emphasis on the problematic living conditions facing prospective German brides abroad.Footnote 19 They also provided didactic material that went beyond strict legal guidance to provide advice about what German women could expect if they married Muslim men. The 1962 issue of Jugend featuring the cover-girl bride contemplating marriage to a Muslim man is just one sample from the broad and multifaceted public information campaign through which these organisations disseminated their advice to young women – advice based on particular characterisations of Muslim men and gender roles in Muslim societies.

Protestant and Catholic organisations kept each other apprised of their efforts in regards to educating the public about Christian–Muslim marriages. They exchanged their materials on interethnic marriages with one other and disseminated each other's pamphlets and brochures to interested parties.Footnote 20 They believed that their concerted efforts were very important indeed. As one Diakonie counsellor noted when talking about sharing intermarriage counselling responsibilities with other mainline Catholic and Protestant organisations: ‘The more [organisations are involved] the better’.Footnote 21 Also included in the exchange were such diverse institutions as the very active and well-established Protestant Württembergischer Landesverein der Freundinnen junger Mädchen (Württemberg Regional Association of the Friends of Young Girls) as well as the evangelical Orientdienst (Middle East Services) founded in 1963.Footnote 22

The unbridgeable chasm between Christianity and Islam

Thomas Mittmann has recently argued that in the post-war period Christian institutions were instrumental in identifying Islam as the crucial barrier to integration of the Muslim migration population in Germany.Footnote 23 The intermarriage dialogue provides further evidence for this assessment, as the various Christian organisations examined here depicted Islam as a monolithic religion that was fundamentally different from Christianity, entrenched in its patriarchal family and gender relations, and which promoted violence. In this view, marriage could not be successful because love itself was defined by religion; it therefore had a different meaning for Christians and Muslims. A successful union based on a common understanding of love – the fundamental value on which marriage rested – was thus impossible.

In the early literature and correspondence, descriptions of Muslim men were neither uniformly negative nor entirely unique.Footnote 24 Terms such as ‘Muslim’ (or, in the early years, ‘Mohammedan’), ‘Oriental’ and ‘Afro-Asian’ were used interchangeably, but, in many ways, Muslim men were depicted in terms similar to those used for European Christian guestworkers from the (European) Mediterranean countries: hot-blooded, virile and gallant. Various pamphlets and conference papers depicted Muslim men as initially ‘exceptionally polite’, ‘considerate’, ‘generous’ and exuding ‘exotic charm’.Footnote 25 In this way, they were ‘not nearly as “prosaic”, “matter-of-fact” or “sober” as the central European’ man.Footnote 26 Moreover, just like ‘the Mediterranean’, ‘the Oriental’ had a violent streak.

Yet the particular nature and object of Muslim men's violence fundamentally distinguished them from European men. Whereas a ‘hot-blooded’ European might be depicted as using violence against men whom he saw as amorous competitors, as was often reported about Mediterranean guestworkers, the Muslim man was also portrayed as violently attacking his female spouse. The Muslim husband's violent behaviour towards his wife became an established trope in accounts of intermarriage in the Middle East, so that religious devotion came to be considered a predictor of violent, oppressive behaviour condoned by Muslim society at large.Footnote 27 Some commentators conceded that life in Oriental culture could change politically, economically and in some social respects, yet they were nearly unanimous in their belief that two factors of Muslim culture exhibited an ‘unvarying capacity to persist . . .: Religion and the clan, Islam and family ties’. It followed that ‘The status of women and family remains fundamentally Islamic-Orientalist, even if the Oriental has studied in Europe and is trying to live a European way of life’.Footnote 28 This argument was repeated throughout the advice literature, asserting that cultural difference – including the violent treatment of women – could not be overcome, no matter how much Muslim men otherwise adapted to a European lifestyle while living in Germany. Rather, Muslim men were intrinsically ‘Oriental’, their views on women, violence and marriage inextricably connected and unchanging.Footnote 29

Advice literature attempted to lift women's veil of ignorance about Muslim culture by explaining stringent Muslim customs particularly in relation to women's role in society: women were not allowed to leave the house without the husband's permission; the man had the right to have up to four wives and to castigate them, and he often made use of this right; men could not be accused of adultery, while women could be punished for it – with six months in prison in ‘civilised countries’, and with death by stoning in countries such as Saudi Arabia and Yemen.Footnote 30 A 1966 booklet by religious education teacher Erich Volandt, entitled Ausländer zum Heiraten gesucht (Seeking Foreigner for Marriage), underscored its discussion of the violent, patriarchal nature of Muslim culture with ostensibly humorous sketches that depicted a stereotypically Middle Eastern man wearing a caftan and turban, hitting a woman (his wife) with a whip or cane. In another, a woman was literally getting kicked out of the house.Footnote 31 Orientdienst's Die christlich–islamische Mischehe (The Christian–Muslim Mixed Marriage) gave added authority to the argument of the oppressive and violent nature of marriage in Muslim countries. The pamphlet was made up almost exclusively of quotes from the Koran and Islamic scholars – and thus what could be considered authoritative sources about intrinsic aspects of Islamic life and religion. Apart from reiterating the primacy of male authority, including the man's right to polygamy and to holding his wife captive, quotations from Muslim theologians compared the role of the wife to that of a slave or argued that the husband would only have contempt for his wife (because otherwise she would not honour him). The text further quoted from a Saudi Arabian Muslim marriage contract that underlined the power a husband had in marriage, and the booklet closed with the Orientdienst's own – negative – stand on Christian–Muslim intermarriage.Footnote 32 A memo from the headquarters of Diakonie praised the publication as ‘matter-of-fact and clear . . . The warnings about a Christian–Muslim mixed marriage are by no means exaggerated’.Footnote 33

At the heart of these assessments was the idea that love itself was religiously constituted. Authorities weighing in on intermarriage doubted that the male Muslim partner could understand love the way his female Christian partner did, let alone reciprocate it. As Volandt explained, different understandings of love and sexuality existed among ‘Orientals’, even if foreigners were of the ‘erroneous opinion’ that their ‘feelings are just the same as ours’.Footnote 34 Hermann Haeberle, who for many years ministered to German women married to Muslim men abroad, maintained that ‘To the Oriental, the woman is the object of his sexuality, the bearer of his children, neither their educator, nor their mother in the original sense of the word. The man does not know marital fidelity. He abandons his wife when she starts to wilt physically’.Footnote 35 In another instance, a contributor to Jugend argued that ‘Love is able to bring together forces drawn in opposite directions; it only receives its deepest and strongest power, however, where it continues to be buoyed and strengthened by the power of faith. But Christian faith and Islam cannot be united through love’.Footnote 36 Ruth Braun, head of the Württembergischer Landesverein der Freundinnen junger Mädchen, seconded this assessment in the same magazine issue, arguing that ‘the love of two people is not able to unite the two worlds’ of Christianity and Islam.Footnote 37

The idea about different religious conceptions of marriage and love also informed assertions published in Herder Korrespondenz (Herder Correspondence) that Muslim men chose German women not because they loved them but because it seemed expedient. Because of social and religious customs in their country of origin – especially the concept of arranged marriage – Muslim men did not have the opportunity to meet their wives prior to marriage; even more importantly, they had to pay a ‘handsome amount’ to the family of the bride. Choosing a Western woman therefore made marriage more convenient and less costly.Footnote 38

The advice literature repeatedly warned women that religion did play a role in their romantic relationships with Muslim men, not just because it had informed the prospective Muslim partners’ mental world but also because the women's own mental world was that of a Christian – even if they did not want to acknowledge that fact. Thus, the apparently inevitable outcome of ignoring such advice resulted in ‘a lack of spiritual [seelischen] connections between [the Muslim] man and [the Christian] woman’.Footnote 39 Attempts to bring the two worlds of Orient and Occident, Islam and Christianity, together could thus be viewed as problematic not only because such efforts supposedly brought about turmoil but also because they took young women even further away from their religion. This was somewhat like closing the barn doors after the horses had already left. Romantic connections – even if they were not spiritual in nature – were already afoot, as reflected in the growing numbers of German women marrying non-Western non-Christian men.

This line of argument conformed to an understanding of religion as a force essential to culture that indelibly stamped one's character. Volandt, for example, argued that ‘We are all somehow the sum of our two-thousand-year-old history and cannot escape the view of the world and of the reality informed by it. Even the outspoken atheist is influenced by these ways of thinking [Denkvoraussetzungen], whether he accepts them or not’.Footnote 40 Haeberle was unusually frank when he stated Islam was ‘the religion without Christ’, and for him that was ‘the bottom line’. He continued to enumerate the elements he saw sorely lacking in Islam: it was the ‘Religion without the gospel, without forgiveness, without prayer to thy father in heaven, without the strengthening, consoling leadership of the Holy Spirit that provides a feeling of security. Islam is purely a religion based on law [Gesetzesreligion], belief, not faith, but submission’. In this depiction, Islam did not merely seem utterly unattractive but also completely different from Christianity. Not surprisingly, Haeberle ultimately concluded that ‘From the first, what is missing is the common ground that carries and sustains a marriage with all its pressures and tensions’.Footnote 41 While some ministers actually did recommend converting to Islam in some instances to obviate marital conflicts, most did not even address this possibility, and those who did generally argued that even this dramatic step would not prevent marital problems, because ‘it will be incomprehensible to the oriental family that one could change one's religion like one changes one's shirt out of love for another person’.Footnote 42 As we see, Christian authors were themselves dubious that religious beliefs could be so easily put off and taken on. Indeed, the article in Herder Korrespondenz asserted that the disappearance of ‘existing racial prejudices and religious qualms’ and the growing number of interethnic relationships forming as a result could paradoxically engender a host of new problems, because young German women in relationships with Muslim men did not appreciate the lack of religious common ground that Haeberle and others considered so crucial.Footnote 43

Part of the explanation for the vehement defence of religious difference has to be sought not just in contemporary Christian understandings about Islam, but also in the churches’ own insecurities at the time about the role of the Christian faith in German people's lives, particularly in its institutionalised form.Footnote 44 Considered in this light, the positive comments about Christianity and the equality of men and women within it become more comprehensible and compatible with more critical statements about Germans and their own religious lives: ‘how fragile our own lives are, how weak our own power of faith [Glaubenskraft]’.Footnote 45 The following observations about Christianity and Islam by a young German woman, who married a man in Tehran and converted to Islam to facilitate her married life there, then also make more sense. In an interview published in the special issue of Jugend, this young German convert to Islam openly challenged the readers to ask: ‘Where in Christendom can we find such strong ties to God amidst a community of people [inmitten menschlicher Gemeinschaft], as are evident, for example, among Mohammedans on the shop floor? You Christians are already ashamed when you pray at the dinner table’.Footnote 46 Ultimately, it seems, her loss of faith in Christianity was due to the lack of answers and support within the Christian community prior to her conversion.

To understand the disproportionately strong reactions to the very low number of marriages between German Christian women and foreign Muslim men at the time, we have to look beyond the various religious organisations’ concern – apparently genuine – for the wellbeing of German women. The scepticism expressed towards Islam and intermarriage was linked to the problems and anxieties that existed within the German Christian churches at the time about their standing within German society. The churches’ growing concerns about their tenuous hold on members might also explain the irritation among intermarriage experts about the decision to allow Muslims to celebrate the end of Ramadan at the cathedral in Cologne on 3 February 1965. In the media, the gesture did not evoke open protest. As Karin Hunn has argued, news coverage of the event showed that ‘religion among the Turks occasionally even met with sympathy’. Hunn concludes that in 1965, ‘In contrast to the coming years, the Muslim religion did not yet form a negative point of reference among the German public’.Footnote 47 This may well be true insofar as the German public was concerned, especially if that public saw Muslims’ presence in Germany as fairly marginal and self-contained, and moreover recognised and appreciated religious difference and understood Islam in Germany as a temporary phenomenon. Yet the reaction in those sectors of the Christian community that dealt with the intermarriage issue was very different; there the generous act was read as trying to minimise the importance of religious differences, and therefore became highly problematic.Footnote 48 In a letter to Cardinal Frings, then the archbishop of Cologne, the head of the Office of Emigration in the Federal Administration Office, Karl-August Stuckenberg, expressed these anxieties openly while asking the cardinal to reconsider such gestures in the future. After all, as Stuckenberg later explained to the head of the Department of Migration at Diakonie:

Among those who have not yet married [their Muslim partner], often the only reason that prevents them [from doing so], is the Christian faith . . . Now that the Catholic Church has opened up [Cologne] cathedral for Muslim ritual [Ritus des Islam] and given that other churches and cathedrals will probably follow this example, I foresee with great trepidation that those girls raised in the Christian faith, who up until now had reservations about entering into marriage with a follower of the Muslim faith, will now be relieved and take the next step, and all those who so far have kept their acquaintances at bay [bisher nur Bekanntschaften per distance pflegten], will now seriously plan to start a relationship. The example set by the Church will now be used as an argument presented to the parents.Footnote 49

Here, Stuckenberg expressed a fear also voiced in other contexts by emigration counsellors: that German Christian women did not sufficiently appreciate key distinctions between the two religions, thus leading to intermarriage heartache and ultimately failure.Footnote 50

Overall, however, commentators made a self-conscious effort to acknowledge the validity of Islam generally and express appreciation for Muslims in Germany in particular. Officials were keenly aware that their portrayal of Islam and life in the Orient appeared harsh and might fall on deaf ears, but, as they explained, the stated goal was not to ‘create resentment between us and our Mohammedan friends. On the contrary, we want to help both sides’.Footnote 51 They had not set out purposefully to ‘paint black in black. And far be it for us to raise the contempt of the foreigners who work and study here. We just want to see what is.’Footnote 52 Despite evidence to the contrary, as discussed above, publications insisted that they did not understand Christianity as superior to Islam. However, pronouncements about intermarriage also continued to reveal their utter conviction about the incompatibility between Orient and Occident, between Islam and Christianity, especially in the context of marriage. As one article in Jugend argued in 1962, ‘The message of Jesus Christ and Mohammed are so categorically different that a Christian and a Mohammedan have a completely different attitude towards life’. This included their position on marriage and on the role of women in society. The article further asserted that such assessments had

nothing to do with a false sense of arrogance to place ourselves [German Christians] above other peoples [Völker und Menschen] and religions. It is not the intent to argue that, as we might naturally assume, everything is brighter and better here [in Germany]. Rather it is about the importance of realising how much the world in which we live differs from the world of a Mohammedan.Footnote 53

Even more explicit in her assessment of religious differences was Ruth Braun. She very much welcomed the meeting of youths from different (Christian and non-Christian) countries if they were ‘conducted the right way’, because it could ultimately lead young people to realise ‘the abyss that exists between Europe and the Orient’. Education, in other words, would not so much lead to the two religions moving closer together and recognising their commonalities as it would to bringing about the acknowledgment that the differences between the two were too great to overcome in marriages and other areas. A mid-1960s bulletin by St Raphaels-Verein therefore implored women to ‘Make a clear and courageous decision! Undo the relationship [with a Muslim]! You will save yourself and your family much sorrow and misfortune. And just believe in this: If God has appointed you to be married, then He will make sure that you find a Catholic partner that suits you’.Footnote 54

The deployment of racial rhetoric

While asserting the unbridgeable religious and cultural chasm between Orient and Occident, writers of the advice materials generally tried to avoid any association with racial politics as they had been practised in Germany just two decades earlier. There were exceptions; in particular, those who counselled German women abroad sometimes still deployed racialist ideology when trying to explain the failed marriages they encountered. For example, Haeberle asserted that he had ‘noticed repeatedly that children born in those marriages often develop into conflicting [zwiespältige] characters, as they combine oppositional genetic material [gegensätzliche Erbanlagen]’.Footnote 55 More commonly, however, officials strenuously denied that ‘chromosomes’ or ‘biology’ factored into the dire assessments of an interethnic couple's marital longevity.Footnote 56 For example, Gerhard Stratenwerth, then head of the Kirchliches Außenamt der Evangelischen Kirche in Deutschland (the Office for Foreign Affairs of the Protestant Church in Germany; hereafter KA), argued that the issues raised in assessing marriages to foreigners were ‘not questions of a biological nature. This would rightfully be rejected as racist discrimination’.Footnote 57 Pre-emptively addressing – and then dismissing – charges of biological racism made it possible to continue to talk about culture and difference without completely striking the concept ‘race’ itself from the vocabulary.

From the beginning of the debate, internal correspondence, advisor conferences and advice literature explicitly and unselfconsciously utilised the concept of race. For example, Stuckenberg argued at the annual meeting of emigration counsellors in 1961 that the most pressing questions on intermarriage were ‘certainly raised about marriages that European women want to enter into with Oriental men or other members of the coloured races’.Footnote 58 Diakonie talked about Völkervermischung (mixing of peoples) and romantic ‘relationships between different races’ in their correspondence to parents seeking advice. As late as 1980, a Caritas counsellor, while admitting that German society was not free of prejudice vis-à-vis foreigners, still referred to ‘racial differences’.Footnote 59

In other instances, ‘race’ as a category was not only used as a matter of course within the intermarriage discourse, but its application also explicitly defended. As various editions of the advice brochure Ehen mit Ausländern (Marriage to Foreigners) between the mid-1960s and mid-1970s stated:

What is true for religion, folk traditions [Volkstum] and language, is even more relevant for the differences between the races. On this point we [Germans] are a bit sensitive, as differences between races were once overemphasised here and the value of our own race excessively promoted. Race hatred is contemptible to us. The equality of all humans has become self-evident for us, and whoever says anything else rightfully encounters the charge of being backward.Footnote 60

This passage reflects a common trope in post-war Germany: a tortured attempt to reject the racial politics of the Nazi period while also insisting that the concept of race was real. The 1967 radio play ‘The Black Groom: A Contribution to the Race Debate’, broadcast by the Bayerischer Rundfunk (Bavarian Broadcast) Church Radio, explicitly defended the continued salience of the concept of race if not the term itself. The play featured a conversation between a daughter who was in love with a Muslim and her father. While the daughter tried to convince her father that it was time for love to scale the wall between cultures, races and religions, and to bring about one community, even if it was difficult to do so, her father depicted these same boundaries not only as natural, but also as permanent and necessary. Therefore it would be futile if not harmful to breach them. As the father maintained:

To divide [the world] into races is a fairly new development within human history, definitely not as old as the races themselves. One could abolish racial thinking. It might even be possible to get rid of the word ‘race’ completely. But what will not disappear are the differences that exist among humans. New names will be given to them and divide [humans] anew. Not just out of malice but out of the necessities of life. We are all creatures that must assert ourselves against one another. Therefore, boundaries have to exist. Life would just be chaos otherwise. Not every human being accepts another as equal, unfortunately. Yes, before God we are all equal, but not before one another.Footnote 61

The father's words echoed what many other commentators also argued, if in less explicit terms: differences between peoples, whether labelled ‘racial’ or not, were real and inevitable; trying to overcome them was futile, even dangerous, threatening to bring about ‘chaos’.

Participants in the debate also continued to employ rhetoric based on biological understandings of race. Friedrich Minning, former general counsel for the Protestant Church in Erfurt and head of the BVA–AfA until 1973, was among the most strongly invested in the issue of intermarriage. In a 1972 article, he proclaimed that

Even the [Muslim] husband's good intentions usually cannot change customary and usually established habits . . . The inherent [angeboren] affinity for traditional ways of thinking, feeling and acting that shape his environment . . . often differ fundamentally from that of the central European [husband] . . . We would be mistaken if we criticised and judged the foreign partner because of his immersion [Einfügung] in his native behavioural pattern.Footnote 62

Here, Minning managed to emphasise the racial incompatibility of European/Christian and Muslim cultures even as he ostensibly posited both as equally valid. At the November 1973 Conference on Foreigner Questions, Enver Esenkova, an Islamic scholar, used even more problematic language when he defined marriage between a Muslim and a Christian as a union ‘between a man and a woman of different faiths, different habits, and different social and racial origins’, and argued that such a union ‘represents the invasion of foreign elements into a body’.Footnote 63 Esenkova's statement unselfconsciously echoed Nazi rhetoric about Jews and others deemed undesirable during the Third Reich.

Even if arguments did not specifically use racial rhetoric, they did represent views that betrayed hierarchies of difference. In his discussion of German women married to Muslim men in Egypt, Minister Unkrig from the German Protestant parish in Cairo argued:

One would have to have an understanding of youth psychology to be able to understand this [Egyptian] people. Among them, we find the very lovable pushiness [Aufdringlichkeit] of a four-year-old, the once-seen-and-ready-to-do-it [approach] of a bright eight-year-old, the know-it-all attitudes of a freshman [1. Semester], the puberty-fuelled emotional outbursts vacillating between love and hate of a fourteen-year-old, the hidden inferiority complexes of a slow Latin student, but also the enthusiastic [offenherzige] friendliness, the proud hospitality of the poor, and skilful adaptability.Footnote 64

Unkrig's condescending characterisation only contributed to reaffirming observations that were rooted in racial arguments, as Egyptians appeared as childlike, and therefore stunted and inferior from an evolutionary point of view.

Those who ultimately paid the price for daring to enter into interethnic relationships with ‘incompatible’ partners were the German women living in the Middle East. According to the experts, they were woefully ill-equipped to deal with these experiences. As a result, according to Unkrig, ‘many break down because of the permanent emotional overexertion, they become slovenly, [they] Egypticise. They move around unkempt during the day, wearing a night-gown or bathrobe and slippers in their own home’.Footnote 65 The Catholic nun Sister Liselotte Köhler, who also worked within the German Protestant Community in Cairo, asserted that

after asking around 300 German wives who are married to Egyptian men, newlyweds, or established couples, who are in marriages that seem to work, I received the same answer from every one of them: if I had to decide again about marrying an Egyptian, I'd never do it. I also want to add that, if a wife is not able to come to terms any more with marriage and family, an escape from this situation is rarely possible. The husband even has the right to castigate his wife. Suicide or the insane asylum might be the end result of her despair.Footnote 66

We have to wonder if Köhler's horror scenario of brutal, dominating husbands and abused wives, and Unkrig's assessment of women's ‘Egypticisation’, were not also tainted by the writers’ own highly sceptical views of Middle Eastern culture – Islam in general, and Christian-Muslim marriages in particular. Reports in the 1980s and 1990s argued that residents of German communities in parts of the Middle East were highly biased against interethnic marriage and not very welcoming of their female compatriots who married Muslim partners.Footnote 67 Similar attitudes probably also prevailed in the preceding decades. Thus, it might not have been Muslim customs alone but also the attitudes of Germans themselves that made the life of German women in interethnic marriages difficult.

The mixed legacy of the 1970s

The most explicitly racial remarks about Islam and the detrimental effects of life in a Muslim country emerged most strongly during the early 1970s, the heyday of the intermarriage debate. At the time, key aspects of the discourse were already changing, however, as the focus turned towards those interethnic couples who lived or wanted to live in Germany but found it difficult to do so legally. Women in such relationships had started to speak up and organise themselves to address the injustices they as German citizens suffered because they were married to foreigners. Their activism also effected legal changes, some of which were already under way due to the state's attempt to deal with the growing presence of guestworkers and their dependents within Germany's borders. The growing plurality of voices from the early 1970s onwards, the concomitant shift in focus towards Germany and the enactment of legal reforms contributed to a broader acceptance of intermarriage without at the same time appreciably changing the tenor of characterisations of Islam. Instead, in what other scholars have identified as growing concern about ‘re-Islamicisation’ in the early 1970s, well-worn tropes about Muslim religion and culture continued to inform discussions that focused increasingly on Turks qua Muslims. This occurred even as alternative voices within the emerging interfaith dialogue also attempted to provide more nuanced understandings about the Muslim religion in the context of marriage.Footnote 68

Especially those who still assumed that women would move to their husband's country of origin continued their strident rhetoric against intermarriage to warn of the dangers of such a union. For example, Friedrich Minning, who had been instrumental in shaping the debate since its early days, in 1972 still defiantly maintained that:

The modern mobile society has reached a greater freedom when it comes to choosing one's partner, but has not minimised or even solved the concomitant problems. Such a depiction has nothing to do with race discrimination. Only those maliciously inclined [Böswillige] or those who are ideologically blinded can claim such a thing. In reality it is the revelation of sociological findings, which shed light on the fact that people from faraway and foreign countries are not inferior but absolutely equal – it is just that their perception and behaviour are different.Footnote 69

Reiterating some of the earlier arguments about the problems that arose due to the lack of (physical and ideological) barriers properly to direct partner choice, and rejecting the charge of racism, Minning also managed to emphasise once more that insistence on the existence of cultural and religious difference was not a value judgment. At the Conference for Foreigner Questions in 1973, he expanded on the dire consequences of not heeding those differences, saying that he dared to be

so bold as figuratively to extend the basic principles of current social welfare legislation, which grants the blind and handicapped legal claims to take advantage of the aid of the community, to those women who want to enter into marriage with a foreigner, and who are thus – quasi blind or handicapped – in need of support in these particular circumstances because of their ignorance or misjudgement of the circumstances that will principally shape their lives.Footnote 70

In other words, to ignore or to dismiss the warnings about incompatible values was a form of self-mutilation, rendering women virtually blind or handicapped and reliant on the mercy of the state.

Given such an outlook, the persistence of intermarriage worried many experts, and the assumption that these women would move abroad also endured.Footnote 71 By 1972, the counselling of young women and girls considering marriage to a foreigner was listed among the top four priorities of the Department of Migration in the Diakonie, even though in the early 1970s such work only made up between about 1%–3% of the overall case load.Footnote 72 In addition, by March 1973 all parishes of the German Protestant Church in the Middle East had social workers and ministers to advise and support German women who were married to foreigners.Footnote 73 Organisations redoubled their efforts in the information campaign that aimed to discourage women from interethnic unions. By 1971, a group of counsellors had initiated a workshop on ‘Marriage with Foreigners’ that focused on ‘the position of the woman in marriage and public abroad’ rather than on the problems the couples faced in Germany – an emphasis retained at the second workshop a year later, even if brief asides now also acknowledged the difficult legal situation faced by couples who wanted to stay in Germany.Footnote 74 The counsellors’ aims in holding the workshops were to expand and intensify existing efforts to provide information on intermarriage and to increase the visibility of the advising services through public-relations campaigns.Footnote 75

The pattern of concentrating on the vicissitudes of married life abroad endured. Various organisations had reported time and again how many desperate calls for help they received in the form of letters from young women stuck in difficult if not downright desperate and abhorrent situations abroad. Letters published in magazines in response to articles about interethnic marriage also attest to this.Footnote 76 It is undoubtedly true that, on average, these marriages did face greater challenges than marriages between Germans. One has to consider, however, that women in happy interethnic relationships had much less reason to write to magazines or to seek assistance and information from the various organisations. Moreover, the claims that these marriages failed because of irreconcilable cultural and religious differences merit further scrutiny. Prejudicial attitudes among those who were supposed to provide aid and support for these women may have exacerbated rather than assuaged marital problems. The legal framework also probably contributed to creating rather than solving the problems, but at the time there was no critical evaluation of the ways in which the tenuous legal situation of foreign male partners might drive a couple to marry just so that they could be in the same country. Marital success stories, on the other hand, when they were presented at all, served as the exception to the rule, paradoxically underscoring the unlikelihood of a successful marriage rather than serving as a hopeful example.Footnote 77

While essentialist arguments about Islam and Muslim culture continued to circulate, especially in the context of emigration, the debate also slowly brought more attention to the situation couples faced in Germany. This was due to the fact that those directly affected by popular negative attitudes towards foreigners and discriminatory laws began to speak up themselves. At the annual meeting of emigration counsellors in 1973, for example, Minning felt the need to assert his views in the context of ‘sensitivities tainted by prejudices especially among members of the Third World, as well as the narrow perspective and rigidity of ideologues’ that he encountered in Germany.Footnote 78 According to this line of argument, the problem was caused not by problematic perspectives among some German experts but by the foreigners’ misreading of those perspectives. The ‘ideologues’ mentioned were apparently Germans, most of them theologians. At a meeting at the Protestant Academy Hofgeismar, they had seconded Muslim participants’ demands for improved legal rights for immigrants after critical remarks by one of the German presenters had provoked members from Muslim countries ‘to protest heatedly that the depiction neither reflected the current circumstances nor the true legal situation’. Minning dismissed those charges and warned against falling into the trap of ‘following the well-intentioned disposition to give in to emotions’.Footnote 79

Apart from Muslims and Christian theologians, women married to foreigners in Germany made themselves heard as well. In September 1972, Rosi Wolf-Almanasreh, a German woman married to a Palestinian, founded the Interessengemeinschaft der mit Ausländern verheirateten deutschen Frauen (Interest Group for German Women Married to Foreigners), commonly known by its abbreviation IAF. Wolf-Almanasreh started the organisation after the terrorist attacks at the Olympic Games in Munich that year, fearing that her Palestinian husband could be caught up in the wave of deportation of Arabs that followed the attacks.Footnote 80 Through her media-savvy efforts to establish a network of self-help groups for German women in similar situations, word about the organisation spread rather quickly, and local branches formed as a result. Beyond providing advice and a venue for talking about the experiences women had as wives of foreigners, the IAF worked towards improving public relations and effecting legislative reform. It also focused on education about other cultures and religions (especially Islam) in the context of intermarriage and protested against discrimination towards their foreign husbands and themselves. Crucially, it was the rights of German women as German female citizens and German wives – specifically, their right to choose their spouses and to live with their families in Germany – that were also at the heart of the IAF's concerns and efforts. In their role as German women, as mothers of children with foreign citizenship and as wives of foreign husbands, IAF members’ efforts to educate the public about interethnic partnerships and to lobby against discriminatory legal practices contributed to shaping the outlook on intermarriage in Germany.

The legal situation improved only gradually, however. As Karen Schönwälder has pointed out, changes in the regulations on the Verwaltungsvorschrift zum Ausländergesetz (implementation of the aliens act) in May 1972 stated that ‘The constitutionally guaranteed protection of marriage and family was now to be given preference over the other concerns, residence permits were to be issued and expulsions were to be avoided’.Footnote 81 Yet by mid-1977 guidelines for naturalisation still asserted that people from developing countries who had come to Germany in the context of foreign aid programmes should not be naturalised.Footnote 82 Moreover, the courts still largely insisted that German women could be expected to follow their husbands back to their home country upon expiration of the residency permit or because of expulsion.Footnote 83 Given that until 1975 the children of interethnic couples received only the foreign father's citizenship, the deck was clearly stacked against the couple's permanent residency in Germany. The tenuous and often confusing legal situation, and continued scepticism about Muslim culture, led Karl-Heinz Kopetzki, then head of Raphaels-Werk, to proclaim defensively that

even if all you [my colleagues] disagree with me, as a counsellor I would go so far as to advise girls in no uncertain terms: keep away from [such interethnic relationships]; nobody can guarantee you that your husband can stay here, [and] nobody can predict how you will cope with the different circumstances [in your husband's home country]; you get into difficulties and cannot escape or get yourself out of trouble on your own. A return [to Germany] is almost hopeless.Footnote 84

He also pointed to the contradictory messages the organisations and the public received: on the one hand, organisations were informed that the Federal Ministry for Economic Co-operation supported Germany's responsibility towards developing countries that students and interns should immediately return after the conclusion of their training. On the other hand, various newspapers and magazines informed their readers that foreigners married to Germans no longer had to fear deportation.Footnote 85 Kopetzki ultimately concluded that the staff of the various organisations involved in counselling prospective intermarriage partners were simply overwhelmed with the task at hand due to the cacophony of messages they received. Recognising these hurdles, organisations slowly came around to identifying structural problems within Germany rather than inherent religious, cultural or racial differences as responsible for the difficulties interethnic couples faced.Footnote 86

The conference in November 1973 for migration counsellors organised by the KA is indicative of the tensions between the different constituencies within the intermarriage debate at the time. While the BfA–AfA had requested that the KA put on another conference on the topic, and asked Minning, the ardent opponent of intermarriage, to give the keynote speech, the conference ultimately and self-consciously attempted to frame the meeting as a counterpoint to the 1966 conference it had hosted, which had emphasised ‘preventative counselling’ and was focused on emigration to the husband's home country. The following comment made by one of the counsellors from the Frankfurt office speaks volumes about how little the idea of couples remaining in Germany had been considered a viable – and advisable – possibility up to that point: ‘the focus [of the conference] is mainly supposed to be on those who stay with their foreign husbands in Germany (!!!???) [sic]. So far, we know only of very few who have managed that’.Footnote 87 So, while Minning still spoke out against interethnic unions, the organisers of the 1973 conference also became more cognizant about the legal problems interethnic couples faced when staying in Germany, mentioning the ways in which the equality statute and sanctity of the family inscribed in the German constitution came into potential conflict with residency and naturalisation laws. In other words, the conference started to raise awareness about the ways in which it was the state, rather than women's desire to marry foreigners, that was the problem. Such a shift in focus also led to a rethinking of how to aid foreigners and conduct advice work, including seminars for emigration advisors to update and further develop their skills and knowledge, and, crucially, the consultation of intermarriage partners themselves at the conferences. Some counsellors still believed that advising was done well when the woman or girl ‘backed out of the marriage to a foreigner’.Footnote 88 Nevertheless, instead of exclusively treating and depicting the marriage partners as the ones in (present or future) crisis, in need of help, counsellors started to view them as potentially valuable sources of information, who could provide insight into the ways intermarriage could also succeed. Contact and co-operation with the IAF also speak to this change in approach.Footnote 89 This gradual shift in attitude was also reflected in other small if significant ways. In mid-1974, for example, a memo circulated by the Office of Migration at the Diakonie advised: ‘Never say “Mohammedan”. The term “Mohammedan” is considered a swear word among those of the Muslim faith!’Footnote 90

Despite growing awareness about the state's complicity in creating difficulties for interethnic couples, continuing difficulties were caused by problematic and undifferentiated depictions of Islam, Muslim men and life in the Middle East, even as those Muslims were increasingly of Turkish origin. By the late 1970s, Turkish men were among the top five foreign marriage partners of German women. While experts and literature acknowledged that fact, they merely included Turks among the ‘Afro-Asians’ or ‘Orientals’, as the following comment by a participant at the second meeting of the workshop on ‘Marriages with Foreigners’ in 1972 illustrates: ‘While I am now going to stick to my example of Turkey, it can symbolically stand in for all Afro-Asian marriages’. She added that ‘slight differences’ might exist, but recognising them in this context ‘would be taking things too far’.Footnote 91

Already by 1965, Orientdienst had produced a pamphlet specifically targeting women considering marrying a Turk. Entitled Seine Frau werden? (To Become His Wife?), it was organised as a series of (mostly leading) questions and answers regarding various issues that should be considered in the marriage decision: how the couple met; what the boyfriend really thought about his girlfriend; whether the boyfriend might already be engaged to be married to somebody else; and whether the prospective wife knew what to expect in her partner's home country, especially in terms of living conditions, family life and religion. While mostly focused specifically on life in Turkey and interactions with Turks, the answers also reflected notions expressed in earlier literature about the primacy of the Muslim religion and the incompatibility between a Christian wife and her Muslim husband. The pamphlet maintained, for example, that the young woman would enter her prospective husband's household ‘as a servant’ and warned that ‘nobody will respect your religion’. Maintaining old friendships would be a futile endeavour because the husband would insist that ‘the relationship with his family has to suffice’. The fact that the first edition was largely unchanged when it was reprinted in 1982 shows the longevity of these ideas. The later edition was merely expanded to include a six-page letter from a 28-year-old German wife of a Turkish man in Anatolia that was to serve as a warning about the difficulties of such a relationship. The editors insisted that the document was ‘not supposed to be a “warning” against intermarriage in the usual manner’. Instead, it was meant to provide a realistic illustration of ‘the situation in which a German woman married to a Turk can find herself’. Despite the fact that the woman had been happily married for five years, the letter underscored and gave concrete examples related to the various issues raised in the original pamphlet. It emphasised in great detail the woman's difficult interactions with the extended family – manageable mainly because of her ability to keep the Turkish relatives at bay – and the challenging and unfamiliar way of life in Turkey more generally. Crucially, the letter writer concluded that ‘It would be impossible for me to live among the extended Oriental family’, highlighting the way in which Turks were both specifically recognised and also used as an illustration for Oriental (Muslim) culture at large.

As the title of the 1983 publication Ehen mit Muslimen: Am Beispiel deutsch–türkischer Ehen (Marriage to Muslims: The Example of German–Turkish Marriages) suggests, the trend of seeing the life of Turks as representative of broader Muslim culture while also identifying them primarily according to their faith continued.Footnote 92 While the authors took care to present diverse experiences of German wives in Turkey, they ultimately asserted that ‘A large number of Turks do not want to adapt to life in central Europe’ and argued that ‘Islam in Turkish society has more import than Christianity in central Europe. Islam is not merely personal faith but the expression of national belonging.’Footnote 93 In other words, Islam was intrinsic to national identity. Reflecting on women's roles in Turkish society, the authors of Ehen mit Muslimen maintained that ‘the veil had fallen’. Images throughout the publication showed Turkish women wearing headscarves, even a niqab, underscoring the assertion that traditional Muslim gender norms nevertheless governed everyday life.Footnote 94 The message of the publication was therefore ambivalent. While not wanting to dismiss intermarriage out of hand, the assessment of life in Turkey provided by the publication reflected the deep scepticism about Muslim culture that had informed the intermarriage debate for decades.

Epilogue

The evolution of the intermarriage debate beyond the 1970s merits further exploration, especially as it has intersected with interfaith dialogue initiatives and the mounting concerns over the growing numbers of foreigners, particularly Turks, settling in Germany. The following observations are meant to highlight some of the trends that have developed since the 1980s. For example, voices within the Catholic Church have self-consciously positioned themselves in opposition to the official – mostly negative – assessment about Islam and intermarriage. Yet broader trends have also persisted, such as the identification of Turks primarily as Muslims and the reliance on Christian scholars as authorities on Islam.

These authorities have emerged within initiatives and groups fostering interfaith dialogue that have developed since the 1960s, and some of which have also dealt with questions of marriage to foreigners, particularly Muslims. For example, the Ecumenical Office for Non-Christians (Ökumenische Kontaktstelle für Nichtchristen, ÖKNI), was founded in Cologne in 1974 under the leadership of a member of the White Fathers, Werner Wanzura.Footnote 95 A few years later, another White Father, Hans Vöcking, was tasked by the Catholic Church with establishing the Christian-Muslim Congress and Documentation Centre (Christlich-Islamische Begegnungs- und Dokumentationsstelle, CIBEDO), which he headed for twenty years.Footnote 96 Other organisations and groups such as the Protestant Church Service for Mission and Ecumenism (Gemeindedienst für Mission und Ökumene, GMÖ) and the Committee of the Protestant Church in Germany to Aid Foreign Employees (Ausschuss der EKD zur Hilfe für ausländischen Arbeitnehmer) have also increasingly turned their attention to the growing number of Muslims in Germany. They all produced literature focused on Islam and Christian–Muslim dialogue from the early 1970s onwards.Footnote 97 Tellingly, the very first guide called Moslems in der Bundesrepublik (Muslims in the Federal Republic), created by a committee within the Protestant Church and endorsed by its council, also contained chapters on marriage to Muslims and on the emigration information offices.Footnote 98 As Thomas Mittmann has recently shown, the role of the Christian churches in the interfaith dialogue has proved to be highly problematic, especially in the way that they have shaped popular perceptions of the Turkish population and the Muslim religion. He argues that ‘Through semantic and discursive strategies, the Christian institutions succeeded in identifying the “foreign religion” [Islam] as the decisive barrier to integration of the migrant population in Germany and Europe’.Footnote 99 Churches have propagated a largely homogenous view of Islam, depicted as unsuitable for the contemporary secular world because it has supposedly lacked the modernising trends within the Christian faith.

These perceptions were certainly reflected in the early discourse on intermarriage as well, and Muslims themselves remained conspicuously absent among the experts on Islam. Still, a more complicated picture emerged from the 1980s onwards. The Catholic Church, for example, did not respond with one voice to the ongoing challenges posed by intermarriage. On one hand, Muslime in Deutschland (Muslims in Germany), published in 1982 by the Deutsche Bischofskonferenz (Conference of German Bishops), still warned about fundamental differences between the religions, including their divergent concepts of marriage. According to the publication, these ‘profound disparities’ could not be overcome, so that marriage between a Catholic woman and a Muslim man needed to be prevented ‘as much as possible’.Footnote 100 On the other hand, since the 1970s Raphaels-Werk had created a number of pamphlets on intermarriage that did not reject the idea of intermarriage outright, though it was not until 1983 that a more in-depth publication appeared, entitled Ehen zwischen Katholiken und Moslems in Deutschland (Marriages between Catholics and Muslims in Germany) and specifically directed at the clergy.Footnote 101 As the preface, written by Father Wanzura, stated, the guide was not an official announcement from the Catholic Church, but was supposed to provide support for pastors faced with prospective couples who saw their marriage as a ‘done deal’, and the Catholic partners who wanted ‘to remain in the Church despite the resistance’ they faced.Footnote 102 At a conference for migration counsellors, Wanzura explicitly spoke out against the warning of the Conference of German Bishops, remarking that it was ‘highly questionable, since it [the official warning] would not prevent’ these marriages.Footnote 103 Like the Protestant literature from the 1970s onwards, the content pointed out both similarities and differences between the religions rather than dwelling on immutable chasms, and in the context of intermarriage mentioned first commonalities such as the primacy of family, honour and love within it and the responsibilities as well as rights of the husband.Footnote 104

Criticism about the negative assessment of intermarriage continued from within the Church's ranks. At the annual conference for migration counsellors in 1984, Father Hans Vöcking took the Christian churches in Germany to task for emphasising ‘dangers . . . more than opportunities’ in the context of intermarriage.Footnote 105 He also insightfully criticised the German state for failing to recognise partnerships beyond marriage, thus creating difficulties for unmarried interethnic couples. He further chided those who viewed culture as a closed system and theoretically advocated greater openness towards foreigners in general and interethnic couples in particular. And yet, for Vöcking, life for a German woman in a Muslim country was a difficult endeavour as it seemed nearly impossible to live the ‘European family model’, as he called it, because Muslim society just exerted too much pressure on the couple to follow traditional European/Christian family patterns.Footnote 106 Vöcking still presented Islam in very homogeneous terms, as a monolithic religion prescribing a strictly patriarchal social order in which women are forever dependent on men (such as fathers and husbands) and therefore at odds with Western Christian values.Footnote 107

In contrast, as the topic of Islam in the context of intermarriage was revisited at the 1992 conference for migration counsellors, Father Wanzura not only expressed admiration for key tenets of Muslim life, but also acknowledged the cultural diversity among followers of the Muslim religion. As he put it, ‘Islam as such does not exist’.Footnote 108 As a major point of departure, Wanzura praised the importance Islam bestowed on family, with the Koran's emphasis of mutual respect and love between the spouses and the feeling of security and protection it offered. Thus, Wanzura managed to reinterpret aspects of Muslim culture as positive and supportive that had previously been disdained as confining and limiting for the German wife. Furthermore, one of the greatest sticking points in the past had been the Muslim man's right to polygamy. Wanzura tried to confront and disarm this criticism by pointing out that the Koran stated that men had to treat and love equally each of their wives, arguing – disarmingly simply – that this was hardly possible. Muslim theologians, he continued, had concluded that the Koran was therefore really supporting monogamy ‘though by law polygamy was still possible’. Wanzura even defended arranged marriages, arguing that they had one of the lowest divorce rates because of the support of the families who were invested (presumably emotionally as well as financially) in these unions.Footnote 109 He ended on a confident note, remarking that in his experience ‘when couples sufficiently reflect [on their decision] before the wedding, then these [interethnic] marriages are as solid as “normal” marriages’.Footnote 110 Despite Wanzura's positive assessment of the Muslim religion, the distinction between interethnic marriages and ‘normal’ ones indicates that these unions, more than four decades after the debate began, still were not considered mainstream.

Furthermore, in his presentation ‘with an emphasis on the situation in Turkey’, Wanzura followed the common trend of identifying Turks first and foremost as Muslims, even as he quoted statistics showing that 75% of adolescent and adult Turks in Germany did not have and did not want to have anything to do with Islam.Footnote 111 Even more dramatically, according to Wanzura, 90% of all Turks living in Germany were ‘unable to explain their faith’, many mistaking ‘Turkish customs for Muslim duty’. Referring to his publication on marriage between Catholics and Muslims in Germany, Wanzura remarked that in the conference proceedings the organisers could just ‘say Germans here instead of Catholics. I had to say Catholics because I am a priest and need the imprimatur of the cardinal’.Footnote 112 Tellingly, Wanzura did not advise the conference organisers to identify the German marriage partners as ‘Christians’, further highlighting the primacy of religion in understanding the foreign marriage partners, while downplaying it when talking about their German spouses. Thus, by the 1990s, an uneven picture had emerged. On one hand, Christian experts on intermarriage had moved away from issuing warnings about the perils of Christian–Muslim marriages and homogenous, problematic views of Islam. Yet, they also reinforced the notion that Islam centrally informed Turkish identity while further cementing their roles as authorities on Muslim theology.

This ambiguity in the German churches’ views in the 1990s is consistent with the trajectory plotted in the scholarly literature, which has highlighted the 1970s as a crucial decade for migration discourse in Germany, leading to a ‘political and ideological shift towards cultural incommensurability’ based on the religion of Turkish immigrants.Footnote 113 Indeed, the churches’ views in the 1990s are just one example of the continuing power of these ideas about cultural incompatibility. Yet this investigation of the post-war intermarriage discourse has shown that those insisting on insurmountable differences between Germans and Muslim Turks from the 1970s onwards were able to draw on readily available tropes developed several decades earlier – what I have called the first two decades of the intermarriage debate. With its focus on Islam, gender and difference, the intermarriage discourse from the late 1950s through the early 1970s reveals the roots of key concepts of the more recent integration debate. It is equally important to recognise that those ideas were originally articulated in the very different context of West Germany in the initial decades after World War II, and that both the Muslim men and their wives (putative victims) were very different populations than they would be in the 1970s and beyond. The impetus for discussion in the 1960s and 1970s emanated from the church community rather than the political pulpit. Moreover, the focus during these years was on the potential victimisation of German women (not Muslim women) in Muslim countries (not Germany) at the hands of Muslim men, generally university students (not guestworkers) in Germany.