Introduction

Feeding and eating disorders (FED): current perspectives

FED are a set of conditions with different presentations and a multifactorial pathogenesis, featuring the interaction between neurobiological, genetic, and environmental factors.1, Reference Culbert, Racine and Klump2 Although in this field of psychiatry often the pathogenetic role of social environment has been overly stressed, recent studies, focused in particular on restrictive eating disorders, pointed out that the psychopathological core underlying this kind of FED can be found unaltered in different socio-cultural conditions, although these latters may influence the specific clinical presentation.Reference Di Nicola3, Reference Dell’Osso, Abelli and Carpita4 This core, linked to individual vulnerability factors,Reference Dell’Osso, Abelli and Carpita4, Reference Harris5 is characterized by traits such as restriction or avoidance in food intake, perfectionism, rituality, inflexibility, and eventually, emotional dysregulation and impulsivity.Reference Dell’Osso, Abelli and Carpita4, Reference Bemporad6 It should be noted that these traits are detectable not only among those patients who require a treatment for a FED, but also among the wider population of subjects who show milder, subthreshold manifestations of the same psychopathological spectrum.Reference Dell’Osso, Abelli and Carpita4 In the last decades, increasing research has stressed the importance of a dimensional approach in psychiatry, which may reconsider mental diseases as a continuum spanning from personality traits to full-fledged clinical syndromes, and including core, typical manifestations as well as atypical, subclinical, temperamental, and behavioral traits.Reference Kety, Rosenthal, Wender, Rosenthal and Kety7- Reference Mauri, Borri and Baldassari11

The emerging phenomenon of orthorexia nervosa (ON)

In the last few years, it has been reported an increased spreading of different kinds of behavioral patterns that may fall in the spectrum of FED, sometimes featuring possible new full-fledged clinical disordersReference Dell’Osso, Abelli and Carpita4: among the others, particular attention has been paid to the emerging phenomenon of ON.

ON could be defined as a fixation on healthy food, featuring “highly sensitive cognitions and worries about healthy nutrition, leading to such an accurate food selection that a correct diet becomes the most important part of life.”Reference Donini, Marsili and Graziani12- Reference Bratman14 Subjects with ON typically show strong nutritional beliefs and generally attribute a great value to the perceived healthiness and to nutritional properties of foods, rather than to the taste and the enjoyment of the food itself.Reference Varga, Dukay-Szabo and Tury15- Reference Segura-García, Papaianni and Caglioti17 The pervasive concern for correct nutrition, health and well-being leads orthorexic subjects to check daily the food quality, origin, and packaging, resulting in severe distress, and sometimes, in an impairment in social, occupational, or school functioning.Reference Moroze, Dunn and Craig Holland18- Reference Aksoydan and Camci20 Moreover, the tendency toward a progressively stricter selection on food may finally lead to malnutrition and/or severe weight loss, similar to those reported among AN patients.Reference Dell’Osso, Abelli and Carpita4 To date, ON is not formally included in the last edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth editin (DSM-5), nor in the International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision (ICD-11).21 It is still debated whether ON should be considered a specific and unique disease, a variant of other syndromes or, more simply, a behavioral attitude influenced by the cultural context.Reference Bartrina22- Reference Turner and Lefevre24 However, many authors reported data that seem to support the existence of a continuum between ON and AN.Reference Dell’Osso, Abelli and Carpita4, Reference Dell’Osso, Carpita and Muti25- Reference Chaki, Pal and Bandyopadhyay30 A higher prevalence of ON has been reported among female subjects with low body mass index and restrictive food patterns,Reference Dell’Osso, Abelli and Carpita4, Reference Dell’Osso, Carpita and Muti25 while both ON and AN are characterized by restrictive eating habits and traits of perfectionism, rigidity, anxiety, poor insight, and a tendency toward weight loss (although in ON it may appear as an indirect effect of food selection rather than a direct effect of a full-fledged drive for thinness).Reference Ramacciotti, Dell’Osso and Paoli26- Reference Chaki, Pal and Bandyopadhyay30 Furthermore, it has been noticed how severe ON symptoms may represent a risk factor for AN.Reference Ramacciotti, Dell’Osso and Paoli26 The mean prevalence of ON symptoms has been reported to be 6.9% among the general population and 35% to 57.8% among high-risk subjects, such as dietitians, nutrition students, other healthcare professionals, or also sport practitioners and performance artists.Reference Dell’Osso, Abelli and Carpita4, Reference Varga, Dukay-Szabo and Tury15, Reference Marazziti, Presta and Baroni16

The relationship between autism spectrum and FED

It is noteworthy how traits such as perfectionism, rituality, cognitive rigidity, and narrow interests, which can be commonly found in AN, have previously led some authors to stress a possible association between AN and obsessive–compulsive disorder.Reference Koven and Abry29, Reference Altman and Shankman31- Reference Anderluh, Tchanturia, Rabe-Hesketh and Treasure33 However, an increasing number of researchers hypothesized also a possible relation between AN and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) stressing the presence among patients with AN not only of a pattern of narrow interests and stereotyped behaviors linked to food and diet, but also of an impairment in social functioning, including social anhedonia and an altered theory of mind.Reference Dell’Osso, Abelli and Carpita4, Reference Tchanturia, Davies and Harrison34, Reference Baron-Cohen, Jaffa and Davies35 A possible relationship between ASD and AN was firstly hypothesized by Gillberg, who stressed the presence of several symptomatology overlaps as well as a familiar association for these conditions.Reference Gillberg36 After Gillberg’s report, several data, including results from studies with a longitudinal design, reported a higher prevalence of ASD among subject with AN.Reference Rastam37- Reference Huke, Turk and Saeidi41 The recent interest in a dimensional approach toward ASD psychopathology progressively leads to expand the investigation on the relationship between AN and ASD, including also subthreshold autistic symptoms and traits. The importance of subthreshold forms of ASD was firstly stressed when investigating the presence of autistic-like traits among first degree relatives of patients with ASD.Reference Dell’Osso, Muti and Carpita42, Reference Dell’Osso, Lorenzi and Carpita43 However, further studies stressed that autistic traits seem to be distributed in a continuum ranging from the general to the clinical population, with higher prevalence among specific groups and in clinical sample of patients with other psychiatric disorders.Reference Dell’Osso, Muti and Carpita42- Reference Baron-Cohen, Wheelwright and Skinner44 The importance of investigating autistic traits lies in the fact that they seem to be associated, also when subthreshold, with a higher vulnerability toward psychopathology, traumatic events, and suicidality risk.Reference Dell’Osso, Muti and Carpita42, Reference Dell’Osso, Carpita and Gesi45- Reference Dell’Osso, Carpita and Cremone51 In this framework, several studies highlighted the presence of autistic-like traits among patients with AN, stressing how the pattern of pervasiveness, rigidity, and stereotyped behaviors that characterizes the eating habits of patients with AN, closely resembles the one of ASD patients.Reference Gillberg36, Reference Oldershaw, Treasure and Hambrook52 Both disorders present social anhedonia,Reference Tchanturia, Davies and Harrison34, Reference Tchanturia, Smith and Weineck53, Reference Chevallier, Grezes and Molesworth54 deficit in emotional intelligence,Reference Petrides, Hudry and Michalaria55, Reference Hambrook, Brown and Tchanturia56 impairment of executive functions,Reference Strober, Freeman and Morrell57, Reference Carton and Smith58 and rigidity in the set-shifting test.Reference Baron-Cohen, Jaffa and Davies35, Reference Takahashi, Tanaka and Miyaoka59 Moreover, a common structural and functional alteration in the regions of the “social brain,” such as superior temporal sulcus, fusiform face area, amygdala, and frontal orbital cortex, was observed in both AN and ASD.Reference Gillberg, Rastam and Wentz60, Reference Zucker, Losh and Bulik61 Prevalence studies also reported a higher prevalence of autistic traits among patients with AN by means of the Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ), an instrument developed and validated for measuring subthreshold autistic symptoms.Reference Westwood, Eisler and Mandy62 These findings support Gillberg’s initial hypothesis that ASD and AN share common cognitive characteristics and neural phenotypes, although showing an inverted gender prevalence.Reference Gillberg36, Reference Gillberg, Rastam and Wentz60, Reference Treasure63, Reference Krug, Penelo and Fernandez-Aranda64 According to this evidence, some authors also hypothesized how AN may be considered as a female phenotype of autism spectrum, featuring the typical pattern of narrow interest and repetitive behaviors, although focused on food and diet.Reference Dell’Osso, Abelli and Carpita4, Reference Gillberg36, Reference Dell’Osso, Carpita and Gesi45, Reference Oldershaw, Treasure and Hambrook52, Reference Gillberg, Rastam and Wentz60, Reference Treasure63-Reference Lai, Lombardo and Auyeung65 Studies about specific female manifestations of ASD highlighted several differences from the typical male presentations, including a milder impairment of social functioning, with a higher tendency to camouflage social difficulties by imitating peers’ behaviors.Reference Dell’Osso, Lorenzi and Carpita66 A different pattern of narrow interest has also been independently reported among females of the autism spectrum, featuring more social acceptable activities, such as enjoying fictions, spending time with animals, or focusing on food and diet.Reference Dell’Osso, Lorenzi and Carpita66, Reference Auyeung, Taylor and Hackett67 Despite the significant body of data about AN and autism spectrum, limited literature has focused on the prevalence of autistic like traits in other kinds of FED. A few studies available suggest the presence of underling autistic traits also in bulimia nervosa (BN) and binge eating disorder (BED).Reference Tchanturia, Anderluh and Morris68-Reference Medina-Pradas, Navarro and Álvarez-Moya70 One of the most recent studies in this field, a multicenter study led by our research group, compared levels of autistic traits in a sample of patients with restrictive or binge-purging AN, BN, and BED as well as in healthy controls (HC) by means of the Adult Autism Subthreshold spectrum (AdAS spectrum), a questionnaire developed and validated to evaluate the wide range of autism spectrum manifestations.Reference Dell’Osso, Carpita and Gesi45 Results from this study evidenced a higher prevalence of autistic traits in all FED patients when compared to HC, although the highest levels were found among patients with restrictive type of AN, suggesting a higher degree of autism spectrum in patients with restrictive FED.Reference Dell’Osso, Carpita and Gesi45

Aims of this study

In this framework, despite the increasing body of research about ON psychopathology, and the frequent reported similarities between ON and AN,Reference Dell’Osso, Abelli and Carpita4, Reference Koven and Abry29 no study, to the best of our knowledge, has yet investigated the presence of autistic traits among subjects with ON. However, as in the case of AN, subjects with ON show several traits similar to those of subjects in the autism spectrum.Reference Dell’Osso, Abelli and Carpita4 They are obsessed with a correct nutrition, showing a strict cognitive focus on food and diet and reporting ritualized patterns of food preparation and ingestion; moreover, they often experience social isolation due to their feelings of moral superiority and intolerance from other’s food beliefs, with severe difficulties to adjust with social environment.Reference Dell’Osso, Abelli and Carpita4 These symptoms resemble, as it has been stated for AN, to the inflexible adherence to routine and to the pattern of repetitive behaviors and narrow interests, together with impaired social interaction, typical of the autism spectrum. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between ON and autistic traits in an Italian University population.

Methods

Participants

An e-mail invitation through University of Pisa Institutional Governance (Rectorate) was sent to all the students and University workers of University of Pisa. Subjects were asked to provide a set of socio-demographic data and to fulfill the psychometric questionnaires through an anonymous online form. No subject received payment or other benefits for agreeing to participate in the survey. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the local Ethics Committees approved all recruitment and assessment procedures.

Instruments

ORTO-15

The ORTO-15 questionnaire, developed by Donnini et al, is the instrument most frequently used to assess orthorexia symptoms in the literature.Reference Donini, Marsili and Graziani12, Reference Dell’Osso, Carpita and Muti25, Reference Donini, Marsili and Graziani71, Reference Dell’Osso, Abelli and Carpita72 It is composed of 15 items providing a 4-point Likert scale for answers. The items are tailored to investigate cognitive, emotional, and behavioral patterns linked to ON. Scores range from 15 to 60; a lower score is associated with higher orthorexic tendencies.Reference Donini, Marsili and Graziani12, Reference Donini, Marsili and Graziani71 According to previous studies from our group, in the present work, we used the cutoff of 35,Reference Dell’Osso, Carpita and Muti25, Reference Dell’Osso, Abelli and Carpita72 which demonstrated good specificity (94.2%) and negative predictive value (91.1%).Reference Dell’Osso, Abelli and Carpita4, Reference Dell’Osso, Carpita and Muti25, Reference Wentz, Lacey and Waller38

AdAS spectrum

The AdAS spectrum is an instrument developed and validated with the aim to evaluate the wide range of autism spectrum symptoms and traits in adults without intellectual impairment and language development alterations. It is composed of 160 dichotomous items (answer Yes/No) organized in seven domains: Childhood/adolescence, verbal communication, nonverbal communication, empathy, inflexibility and adherence to routine, restricted interests and rumination, and hyper/hypo-reactivity to sensory input.

According to the validation study, the AdAS spectrum demonstrated a good validity and reliability, and it has been already employed in several researches in clinical and nonclinical settings as a reliable measure of the autism spectrum.Reference Dell’Osso, Gesi and Massimetti73

Statistical analysis

The sample was divided in two groups on the basis of the score reported on ORTO-15. Subjects who reported a score lower than 35, which is associated in the scientific literature with the presence of significant orthorexic symptomsReference Donini, Marsili and Graziani12, Reference Donini, Marsili and Graziani71 were included in the “ON group,” while the other subjects were considered as HC. Chi-square tests and Student’s t-test were employed to compare socio-demographic variables and AdAS spectrum scores between groups. A multiple linear regression analysis was performed with ORTO-15 score as the dependent variable and AdAS spectrum total score, age, and sex as independent variables. Finally, another multiple linear regression analysis was performed with ORTO-15 score as the dependent variable and AdAS spectrum domain score, age, and sex as independent variables.

All statistical analyses performed with SPSS version 23.0.

Result

Comparison of ORTO-15 scores and sociodemographic variables in the sample

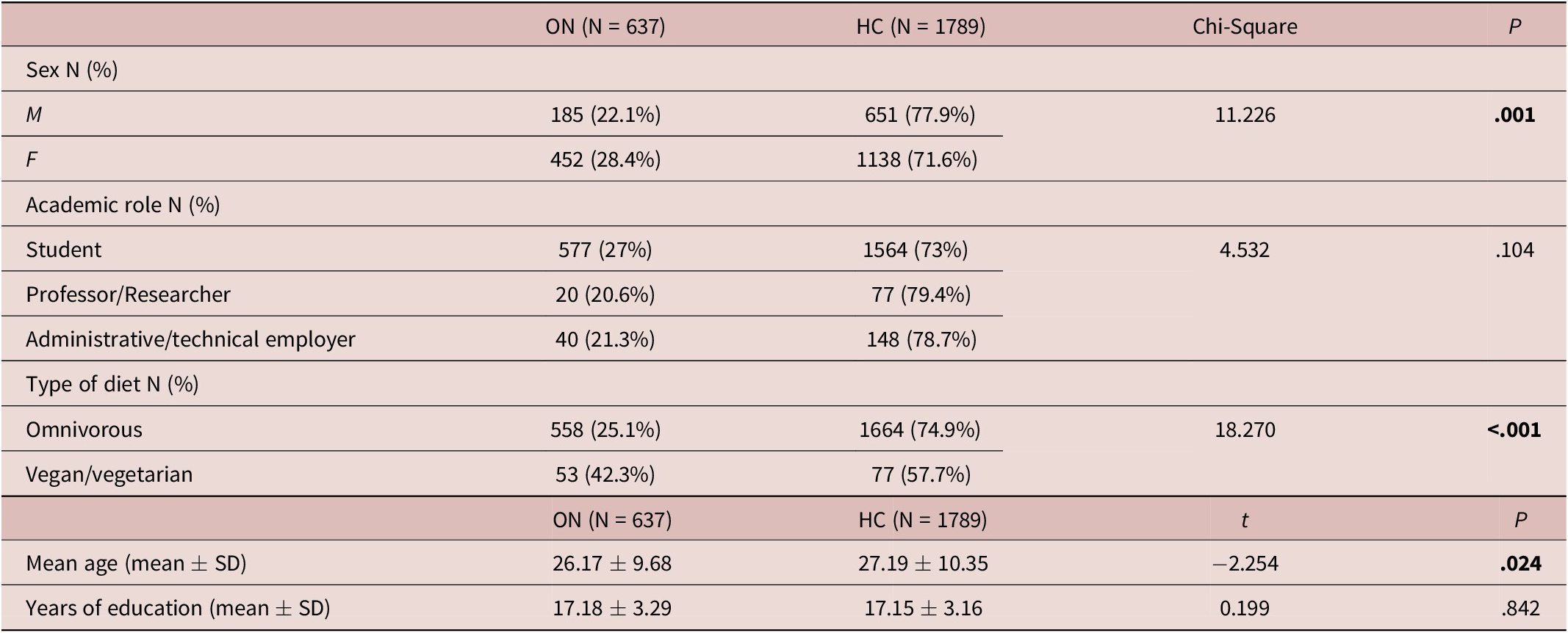

Globally, 2426 subjects answered to all the questions of the psychometric instruments. Among them, 637 subjects (26.3%) reported a score lower than 35 on ORTO-15 questionnaire, and were included in the “ON group,” while 1789 subjects (73.7%) did not show a score associated with orthorexic symptoms, and were therefore considered as HC for the purpose of this study. The ON group was composed by a significantly higher proportion of females than males (28.4% vs 22.1%, P = .001). Moreover, we found in the ON group a significantly higher proportion of subjects who follow a vegan/vegetarian diet than an omnivorous one (42.3% vs 25.1%, P < .001), while opposite results were found in the HC group. The ON group showed also a significantly lower mean age (26.17 ± 9.68 vs 27.19 ± 10.35, P = .024). Groups did not significantly differ with respect to years of education and academic role (student, teacher/researcher, and administrative/technical employer) (see Table 1).

Table 1. Comparison of Socio-Demographic Features Between Groups.

Abbreviations: HC, healthy controls; ON, orthorexia nervosa; SD, standard deviation. The p of statistically significant results are reported in bold.

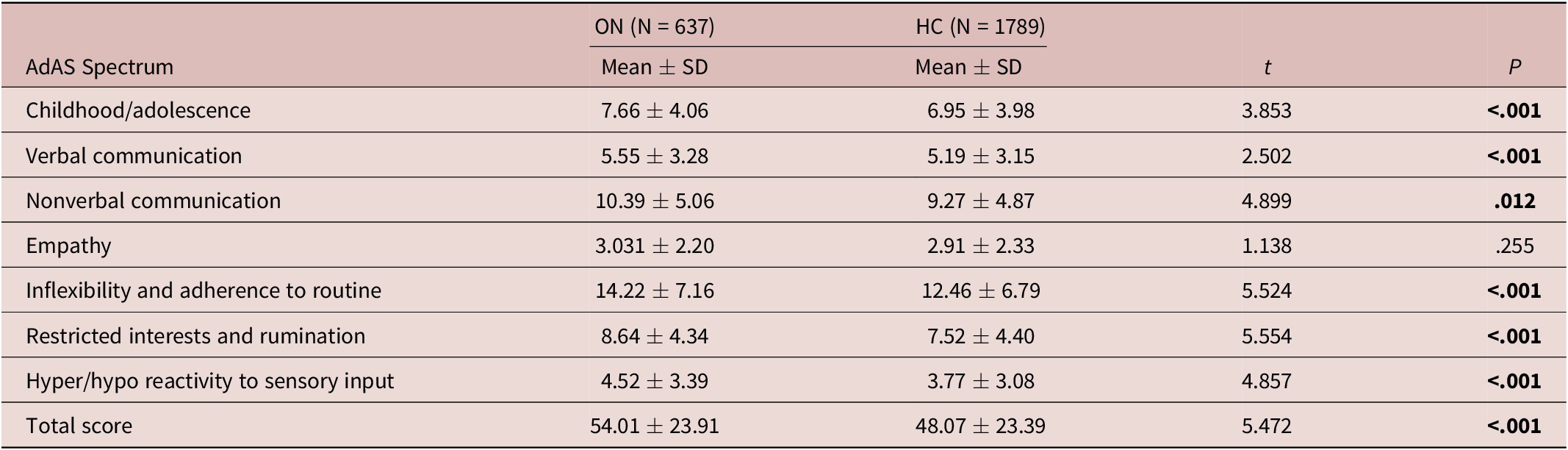

Comparison of AdAS spectrum scores between groups

Subjects in the ON group reported significantly higher AdAS spectrum total and domain scores, with the exception of the AdAS spectrum Empathy domain, for which the two groups did not show a significantly different score (see Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of AdAS Spectrum Score Between Groups.

Abbreviations: AdAS, Adult Autism Subthreshold; HC, healthy controls; ON, orthorexia nervosa; SD, standard deviation. The p of statistically significant results are reported in bold.

Multiple linear regression analyses with ORTO-15 score as dependent variable

We performed a multiple linear regression analysis in order to evaluate the statistically predictive value of sex and autistic traits with respect to ORTO-15 score, considering this latter as the dependent variable and AdAS spectrum total score and sex as predictive variables. According to our results, the regression equation was significant: (F[3, 2422] = 15.930, P < .001). A higher AdAS spectrum total score, younger age, and female gender were statistically predictive of a lower ORTO-15 score (higher orthorexic tendency) (see Table 3). In light of this result, a further multiple linear regression was performed in order to specifically identify which AdAS spectrum domains were statistically predictive of ORTO-15 score, including all AdAS spectrum domains, age, and sex as independent variables. The model identified the following predictors of a higher orthorexic tendency (lower ORTO-15 score): female gender, younger age, a lower AdAS spectrum verbal communication domain score, a higher AdAS spectrum inflexibility and adherence to routine and restricted interests and rumination domain scores, with a significant regression equation: (F[9, 2416] = 8.338, P < .001) (see Table 4).

Table 3. Linear Regression Analysis with AdAS Spectrum Total Score, Age, and Sex as Independent Variables and ORTO-15 Score as Dependent Variable.

R 2 = 0.019; Adjusted R2 = 0.018.

Abbreviations: AdAS, Adult Autism Subthreshold; CI, confidence intervals; SE, standard error. The p of statistically significant results are reported in bold.

Table 4. Linear Regression Analysis with AdAS Spectrum Domain Scores, Age, and Sex as Independent Variables and ORTO-15 Score as Dependent Variable.

R2 = 0.030; Adjusted R2 = 0.027.

Abbreviations: AdAS, Adult Autism Subthreshold; CI, confidence intervals; SE, standard error. The p of statistically significant results are reported in bold.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to investigate the relationship between autism spectrum and ON in a large sample of university students and employers of the University of Pisa. To date, although a large amount of data is available about the relationship between restrictive eating disorders and ASD, no study has yet evaluated the presence of a possible association between autistic traits and ON.

Orthorexic symptoms and socio-demographic features in the sample

In our sample, we found the prevalence of significant orthorexic symptoms was 26.3%, as reported by means of ORTO-15. Moreover, ON group showed a significant lower mean age, which was also a significant predictive factor for the presence of ON in the regression analyses. This finding is in line with previous results in similar samples, which reported a prevalence around 30% when considering the whole university population, with a slightly higher prevalence among students and among younger subjects.Reference Dell’Osso, Carpita and Muti25, Reference Dell’Osso, Abelli and Carpita72 These data further confirm the higher vulnerability toward ON among academic populations, which seem to show a prevalence of ON symptoms higher than the one reported by studies conducted among the general population.Reference Dell’Osso, Carpita and Muti25, Reference Chevallier, Grezes and Molesworth54, Reference Dell’Osso, Abelli and Carpita72, Reference Dell’Osso, Gesi and Massimetti73-Reference Lombardo, Ashwin and Auyeung77 Moreover, we found that the ON group was composed in higher proportion by females and by subjects who follow a vegan/vegetarian diet, while opposite proportions were found among HC. These data are in line with previous researches that reported a higher prevalence of ON among females; some authors hypothesized that females may show a higher interest on healthy diet due to the purpose of controlling body weight and reaching a specific kind of physical appearance, influenced by social media campaigns.Reference Dell’Osso, Carpita and Muti25, Reference Wentz, Lacey and Waller38, Reference Huke, Turk and Saeidi41, Reference Tchanturia, Anderluh and Morris68, Reference Dell’Osso, Abelli and Carpita72, Reference Huke, Turk and Saeidi78 The association between ON and female gender supports the possible presence of a continuum between AN and ON.Reference Dell’Osso, Carpita and Muti25, Reference Dell’Osso, Abelli and Carpita72 Concerning the higher prevalence of vegan/vegetarian diet in the ON group, it should be noted that the link between ON and a specific interest on dietary habits, with a tendency toward ritualized behaviors related to food, was reported also by previous studies and may support the presence of similarities with the autism spectrum continuum.Reference Dell’Osso, Abelli and Carpita4, Reference Dell’Osso, Carpita and Muti25, Reference Huke, Turk and Saeidi41, Reference Lombardo, Ashwin and Auyeung77, Reference Hambrook, Tchanturia and Schmidt79

Links between ON symptoms and presence of autistic traits

When considering the relationship between ON and autism spectrum, our results highlighted that subjects in the ON group showed a significantly higher prevalence of autistic traits than HC, as measured by the AdAS spectrum questionnaire. Moreover, the study highlighted that scoring higher on AdAS spectrum, a lower mean age and being female were statistically predictive factors for the presence of orthorexic symptoms. These results were somewhat expected on the basis of the reported overlaps between AN and ON,Reference Dell’Osso, Abelli and Carpita4, Reference Koven and Abry29 and, on the other hand, of the increasing literature which stresses the close relationship between AN and female autism phenotypes.Reference Dell’Osso, Abelli and Carpita4, Reference Huke, Turk and Saeidi41, Reference Oldershaw, Treasure and Hambrook52, Reference Dell’Osso, Carpita and Gesi45 In this framework, ON could be considered as a manifestation of the same autism spectrum phenotype of AN: according to this hypothesis, for both disorders the symptomatological core may be identified in the underlying autistic traits, manifesting with a specific focus on food and diet.Reference Dell’Osso, Abelli and Carpita4, Reference Dell’Osso, Lorenzi and Carpita43, Reference Dell’Osso, Carpita and Gesi45 Differences in subjective mentalization of symptoms between AN and ON (e.g., adopting restrictive dietary habits on the basis of subjective beliefs about “healthiness” of foods or on the basis of their caloric intake) may depend from changes in the specific inputs received by social environment and/or by the severity degree of the clinical picture.Reference Dell’Osso, Abelli and Carpita4, Reference Dell’Osso, Carpita and Gesi45

Links between specific AdAS spectrum domains and ON

When deepening the investigation about specific autistic features linked to ON, we found that, among AdAS spectrum domains, those statistically predictive of orthorexic symptoms were inflexibility and adherence to routine and restricted interests and rumination. This result is in line with a previous studyReference Dell’Osso, Carpita and Gesi45 which, when evaluating autistic traits by means of AdAS spectrum in a sample of patients with different kinds of FED, found that patients with restrictive AN scored significantly higher than patients with binge eating behaviors on AdAS spectrum total score and on the inflexibility and adherence to routine and restricted interest/rumination AdAS spectrum domains. The association reported in the present work between ON and the same AdAS spectrum domains supports the hypothesis that the link between autism spectrum and ON should be considered in close resemblance to the association of autism spectrum with AN, further stressing the presence of common psychopathological underpinnings for these three conditions. Intriguingly, we found also that higher scores on AdAS spectrum verbal communication domain negatively predicted the presence of orthorexic symptoms, despite subjects with ON scored higher than HC on the same domain. The positive association of ORTO-15 score with AdAS spectrum verbal communication recorded in the regression analysis, despite a reverse direction of effect in the univariate analysis, is a counter-intuitive finding, but an explanation of this result lies in the pattern of associations among the different autistic domains, which were not designed to be orthogonal. The effect of AdAS verbal communication score as a negative predictor of higher ON symptoms may be explained in light of previous descriptions of female autism phenotypes, which would feature a more preserved social functioning, often responsible of the underdiagnosis of autistic traits or even full-blown ASD among females.Reference Dell’Osso, Abelli and Carpita4, Reference Gillberg36, Reference Lai, Lombardo and Auyeung65, Reference Attwood, Grandin and Faherty80 Girls and women in the autism spectrum are more able to recognize their own social difficulties and mask them through the imitation of others’ behaviors, adopting a pattern of camouflaging strategies.Reference Dell’Osso, Abelli and Carpita4, Reference Gillberg36, Reference Attwood, Grandin and Faherty80 They often show also higher levels of social anxiety, a disorder which, as ASD, is associated with an impairment of the social brain but, as AN, is more frequent among females.Reference Lai, Lombardo and Auyeung65, Reference Dell’Osso, Lorenzi and Carpita66, Reference Attwood, Grandin and Faherty80-Reference Dell’Osso, Abelli and Pini85 In this framework, it is possible that a severe impairment in verbal communication would not be associated with the specific autism phenotype underlying restrictive eating disorders such as AN or ON, which would feature, conversely, a more preserved ability to mask social difficulties with learned behaviors and camouflaging strategies, according to previous literature about female autism phenotypes.Reference Lai, Lombardo and Auyeung65, Reference Dell’Osso, Lorenzi and Carpita66

Limits

This study should be regarded in light of several limitations. Firstly, our sample was recruited among university students and personnel, limiting the applicability of our results to other populations. Secondly, subjects were enrolled on voluntary basis, eventually leading to further bias in sample selection. Moreover, both AdAS spectrum and ORTO-15 are self-report questionnaires, and final scores may be biased by over or underestimation of symptoms depending from participant judgment. The design of the study as an online questionnaire evaluation is another element that may have led to inaccuracies in the assessment of symptoms. Finally, the cross-sectional design of the study did not allow making inferences about possible causal or temporal relationships between autism spectrum and ON. Future studies are needed to clarify the link between ON, FED, and autism spectrum. A better understanding in this field may shed light on both autism spectrum and FED psychopathology, leading to improve early diagnosis, prevention, and therapeutic strategies for these disorders.Reference Dell’Osso, Carpita and Gesi45

Disclosure

The authors have nothing to disclose.