Introduction

Parenting encompasses a complex and flexible set of social behaviors that contribute to offspring survival (Clutton-Brock, Reference Clutton-Brock1991) and are considered the cornerstone of offspring's socio-emotional development (Bornstein & Bornstein, Reference Bornstein and Bornstein2007; Feldman, Reference Feldman2021). These sets of behaviors are influenced by parental personality and psychopathology, and social contextual sources of stress (Belsky, Reference Belsky1984). Variation in early parental nurturing affects the developing offspring's brain, thus affecting future social behaviors, including parental style and caregiving (Bush et al., Reference Bush, Wakschlag, LeWinn, Hertz-Picciotto, Nozadi, Pieper and Posner2020; Rilling & Young, Reference Rilling and Young2014). Animal studies have shown that the early care young received from their mothers predicted a wide variety of developmental outcomes, including the type of maternal care that female offspring provided when they became mothers (Lomanowska, Boivin, Hertzman, & Fleming, Reference Lomanowska, Boivin, Hertzman and Fleming2017).

Intergenerational transmission of parenting

There is converging evidence from cross-sectional and longitudinal studies to support the hypothesis that early experiences of nurturing and early bonding with parents shape the type of parenting style and behavior that offspring provide when they become parents, and that the quality of parent–child relationships may be transmitted intergenerationally (for reviews, see Belsky, Conger, & Capaldi, Reference Belsky, Conger and Capaldi2009; van IJzendoorn, Reference van IJzendoorn1992). While most intergenerational studies of human parenting have based their conclusions on two successive generations, recent work has begun to adopt a three-generation approach (i.e., including three consecutive generations in one study). These three-generation studies have investigated the transmission of parenting (e.g., constructive parenting, maltreatment, harsh parenting/discipline, and monitoring parenting) in healthy families and high-risk ones (e.g., families exposed to poverty and violence, substance-using families) by focusing on the continuity of perceived and/or observed parenting in the first two generations (i.e., grandparents to parents), and its impact on various social–emotional–cognitive developmental outcomes (e.g., internalizing, externalizing behavior/antisocial behavior, emotion dysregulation) among the third generation (i.e., children) (Bailey, Hill, Oesterle, & Hawkins, Reference Bailey, Hill, Oesterle and Hawkins2009; Buisman et al., Reference Buisman, Pittner, Tollenaar, Lindenberg, van den Berg, Compier-de Block and van IJzendoorn2020; Kerr, Capaldi, Pears, & Owen, Reference Kerr, Capaldi, Pears and Owen2009; Kitamura et al., Reference Kitamura, Shikai, Uji, Hiramura, Tanaka and Shono2009; Neppl, Diggs, & Cleveland, Reference Neppl, Diggs and Cleveland2020; Smith & Farrington, Reference Smith and Farrington2004; Warmingham, Rogosch, & Cicchetti, Reference Warmingham, Rogosch and Cicchetti2020; Wu, Zhang, & Slesnick, Reference Wu, Zhang and Slesnick2020). These studies suggested that some aspects of parenting show patterns of intergenerational transmission across the first generational cycle (G1→G2), which in turn impacted a wide range of outcomes among the second and third generations (G2 and G3). To our knowledge, one cross-sectional study with a nonclinical sample of families (Roskam, Reference Roskam2013) is the only study to examine the intergenerational transmission of parenting among three-generations of respondents (G1 and G2 reported about their parenting styles towards their children, and G3 reported about the parenting they would plan to display as future parents). They found that parenting practices, mainly supportive, tend to be similar from one generation to the next.

Still, these studies and others have found only modest to moderate associations between parenting across adjacent generations (Belsky, Jaffee, Sligo, Woodward, & Silva, Reference Belsky, Jaffee, Sligo, Woodward and Silva2005), which suggests that other factors may mediate, reduce, or strengthen the links between parents’ bonding to their own parents during their childhood and the parenting they provide to their offspring (Rutter, Reference Rutter1998). Only a few studies have examined individual characteristics that mediate the inte rgenerational transmission of human parenting style, as reported by parents or offspring, including individuals’ unstable personality (Caspi & Elder, Reference Caspi, Elder, Hinde and Stevenson-Hinde1988), antisocial behavior (Capaldi, Pears, Patterson, & Owen, Reference Capaldi, Pears, Patterson and Owen2003), externalizing behaviors (Hops, Davis, Leve, & Sheeber, Reference Hops, Davis, Leve and Sheeber2003), lack of early supportive relationship with peers (Shaffer, Burt, Obradović, Herbers, & Masten, Reference Shaffer, Burt, Obradović, Herbers and Masten2009), and poorer academic performance (Neppl, Conger, Scaramella, & Ontai, Reference Neppl, Conger, Scaramella and Ontai2009). As for moderating mechanisms, social support was examined as a moderator (Egeland, Jacobvitz, & Papatola, Reference Egeland, Jacobvitz, Papatola, Gelles and Lancaster1987), but only in the context of abusive parenting. Still, the psychosocial mechanisms underlying continuity and discontinuity with regard to the intergenerational transmission of human parenting style are not fully understood.

By using our three-generation longitudinal design of individuals at high and low familial risk for major depressive disorder (MDD) with richly characterized clinical and psychosocial data over time, we had a unique opportunity to investigate how experiences of parenting received in childhood are passed down from one generation to the next, and to elucidate the psychological, behavioral, and/or social processes that mediate or moderate such continuities across generations. We first examined such continuity/discontinuity in G1 (parents) and their G2 offspring; namely, whether G1 experiences of parenting during their childhood would predict G2 experiences of parenting during their childhood. We further tested if a similar pattern of transmission would be observed in the next generational cycle; in G2 and their spouses (G2+S) who had children (G3); namely whether G2+S experiences of parenting during their childhood would predict G3 experiences of parenting during their childhood. Finally, in a subsample of families where there were three generations, we examined the transmission of parenting styles across three generations –grandparents→parents→children (G1→G2→G3); namely, whether G1 experiences of parenting during their childhood predict G2 experiences of their parenting during childhood, which in turn would predict G3 experiences of parenting during their childhood.

Psychosocial mechanisms for the intergenerational transmission of parenting

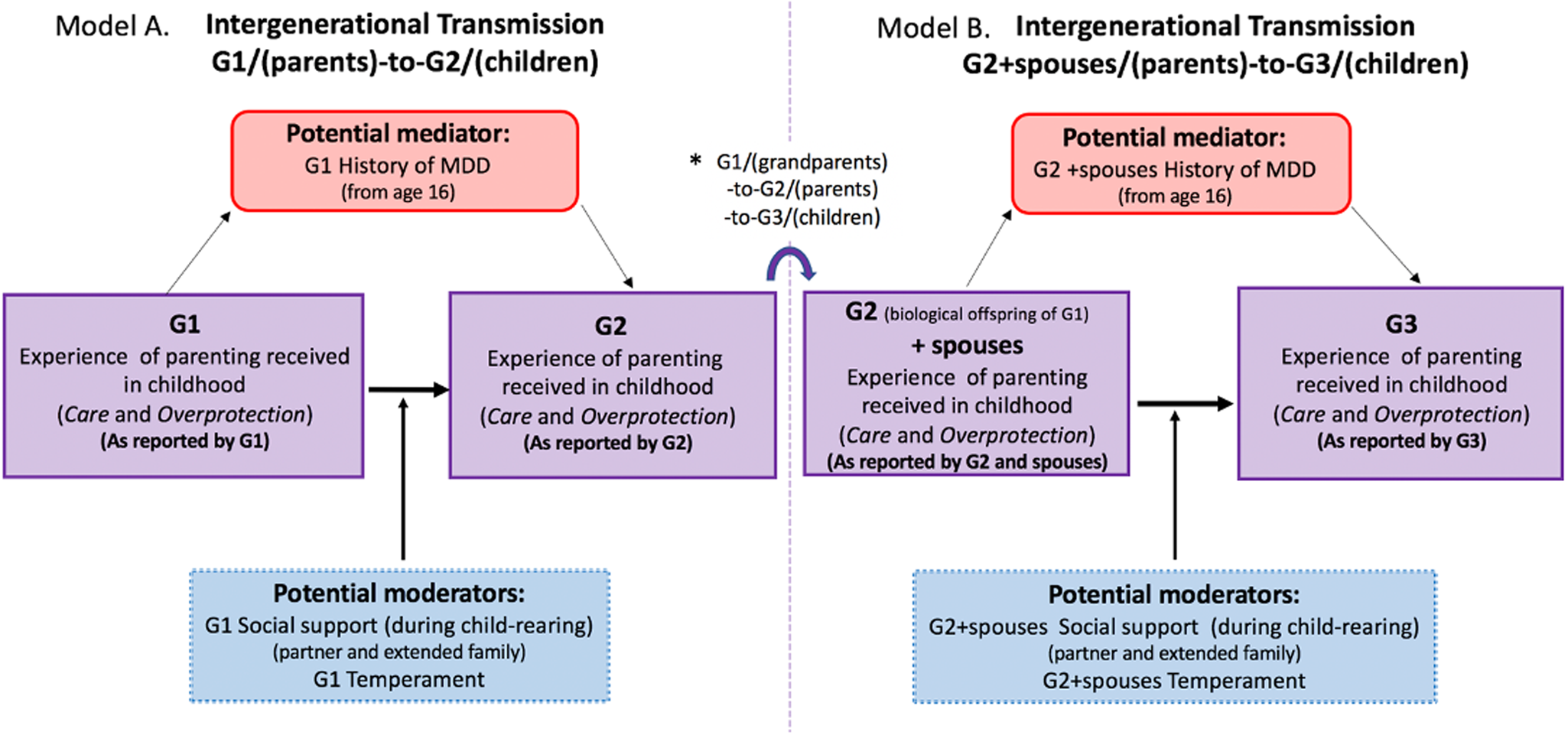

In attempting to explore further the mediating and moderating psychosocial mechanisms underlying the intergenerational transmission of parenting style in humans, Belsky's (Reference Belsky1984) framework of parenting behavior might be especially relevant. Within this framework, the following multiple determinants of parenting have been described: (a) parents’ characteristics – including developmental history (e.g., rearing experiences in early life), personality (characteristics and temperament), and psychopathology (e.g., depression); (b) family social environment – contextual sources of stress and support (e.g., marital quality, family structure, and social support). We explored the relationships between these factors in the contexts of intergenerational continuity/discontinuity of parenting styles. We used the Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI) (Parker, Tupling, & Brown, Reference Parker, Tupling and Brown1979) to measure two aspects of early parental rearing styles, as reported by offspring: parental care (e.g., sensitive and responsive parenting) and parental overprotection (e.g., intrusive and excessively controlling parenting). Respondents in each generation (G1, G2+S, and G3) independently reported on their experiences of parenting received in childhood; that is, G1 reported on their parents’ parenting styles, G2+S reported on their parents’ parenting styles, and G3 reported on their parents’ parenting styles. We focused on three central psychosocial processes involved in human parenting and social behavior as potential mechanisms of the intergenerational continuity and discontinuity in parenting styles across generations: as a potential mediator we considered an individual's history of MDD; as potential moderators we considered an individual's temperament traits and the social support she or he received during childrearing years. We postulated a model of the intergenerational transmission of perceived parenting style (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Psychosocial mediator and moderators in the intergenerational transmission of perceived parenting – a conceptual model of how offspring's experiences of parenting received in childhood are associated with parenting displayed to their own children across two generational cycles. G1 = generation 1; G2 = generation 2; S = spouses; G3 = generation 3. (a) Intergeneration model G1→G2. (b) Intergeneration model G2+S→G3 (for those in G2 who had G3 children). * indicates there was an overlap of 67 biological offspring of G1 (G2) participants who had 58 parents (G1) and 133 children (G3).

Major depression as a mediator

Previous work has revealed that experiences of low care and high overprotection provided by parents during childhood have consistently disposed to the onset of major depression (Gotlib, Mount, Cordy, & Whiffen, Reference Gotlib, Mount, Cordy and Whiffen1988; Mackinnon, Henderson, & Andrews, Reference Mackinnon, Henderson and Andrews1993; Parker, Reference Parker1990, Reference Parker, Hadzi-Pavlovic, Greenwald and Weissman1995; Patton, Coffery, Posterino, Carlin, & Wolfe, Reference Patton, Coffery, Posterino, Carlin and Wolfe2001; Sato, Uehara, Narita, Sakado, & Fujii, Reference Sato, Uehara, Narita, Sakado and Fujii2000), including its development and maintenance (Alloy, Abramson, Smith, Gibb, & Neeren, Reference Alloy, Abramson, Smith, Gibb and Neeren2006; Hein et al., Reference Hein, Thomas, Naumova, Luthar and Grigorenko2019), as well as a number of symptoms in sub-clinically depressed adults (Canetti, Bachar, Galili-Weisstub, De-Nour, & Shalev, Reference Canetti, Bachar, Galili-Weisstub, De-Nour and Shalev1997). Moreover, ample evidence has suggested that depression is robustly linked with a range of social deficits, including poor caregiving (Lovejoy, Graczyk, O'Hare, & Neuman, Reference Lovejoy, Graczyk, O'Hare and Neuman2000; Weissman, Reference Weissman2020). Mothers and fathers who are prone to negative emotional states such as depression tend to behave in less sensitive, less responsive, and more hostile ways than other parents (Foster, Garber, & Durlak, Reference Foster, Garber and Durlak2008; Wilson & Durbin, Reference Wilson and Durbin2010), even those who are not currently depressed but have experienced past depressive episodes (Lovejoy et al., Reference Lovejoy, Graczyk, O'Hare and Neuman2000). However, the mediating role of MDD in this intergenerational transmission of offspring's childhood experiences of maladaptive parenting has not been formally tested.

Social support and temperament as moderators

Social support is defined as the extent to which an individual's emotional, informational, and instrumental needs are satisfied through interactions with other individuals, groups, and the larger community, including their partner and extended family members (Lin, Ensel, Simeone, & Kuo, Reference Lin, Ensel, Simeone and Kuo1979). Social support has been considered a protective factor and a stress buffer that promotes physical and psychological health and overall wellbeing to the individual and their offspring across the life span (Pierce, Sarason, Sarason, Joseph, & Henderson, Reference Pierce, Sarason, Sarason, Joseph, Henderson, Pierce, Sarason and Sarason1996) and confers resilience to psychosocial stress (Ozbay, Fitterling, Charney, & Southwick, Reference Ozbay, Fitterling, Charney and Southwick2008). As for its effect on parenting, it has been found that social support from one's partner, extended family, and peers has a direct positive impact on parental behavior, regardless of context, and can buffer the negative impact of psychosocial stressors on the parent (Green, Furrer, & McAllister, Reference Green, Furrer and McAllister2007). Furthermore, parents who have reported higher levels of social support have displayed more effective parenting practices and sensitive behaviors (Cutrona, Reference Cutrona1984), and their children had better social–emotional functioning (Serrano-Villar, Huang, & Calzada, Reference Serrano-Villar, Huang and Calzada2017).

Temperament is conceptualized as early emerging biologically influenced individual differences in reactivity and self-regulation (Rothbart, Bates, Damon, & Eisenberg, Reference Rothbart, Bates, Eisenberg, Damon and Lerner2006). A person's temperament is relatively consistent over the life span and plays a central role in social behavior across the life span (Newman, Caspi, Moffitt, & Silva, Reference Newman, Caspi, Moffitt and Silva1997). Previous theories (e.g., Chess & Thomas, Reference Chess and Thomas1982) have suggested that a parent's temperament is strongly related to their parenting behaviors. Mothers who had a “more difficult” temperament (Thomas & Chess, Reference Thomas and Chess1977) (e.g., exhibited irregular biological patterns, withdrawal responses to novel stimuli, slow adaptability to change, and predominantly negative mood of high intensity) endorsed more concerning potential for child maltreatment (Lowell & Renk, Reference Lowell and Renk2017), exhibited higher levels of corporal punishment and inconsistent discipline (Latzman, Elkovitch, & Clark, Reference Latzman, Elkovitch and Clark2009), experienced higher levels of parenting stress, and had a lower likelihood of using positive parenting practices (Puff & Renk, Reference Puff and Renk2016). Conversely, an “easy” temperament, which includes positive mood and suitable control and inhibition, has been found to foster resilience and is associated with better adjustment and emotion regulation when confronted with frustration (Cumberland-Li, Eisenberg, Champion, Gershoff, & Fabes, Reference Cumberland-Li, Eisenberg, Champion, Gershoff and Fabes2003). As for parenting, an easy temperament has been associated with parental sensitivity (Malmkvist, Hansen, Damgaard, & Christensen, Reference Malmkvist, Hansen, Damgaard and Christensen2019) and greater self-regulatory processes that parents use to regulate interactions with their children (Bugental & Johnston, Reference Bugental and Johnston2000). However, to our knowledge, no study has yet examined the joint contribution of temperamental traits and early experiences of being parented to the parenting styles one eventually displays with one's own children.

The current study hypotheses

Three primary hypotheses tested the intergenerational transmission of G1(parents)→G2(children) experiences of parenting in childhood (see intergeneration model A in Figure 1).

• Hypothesis 1: G1 experiences of parenting in childhood (specifically parental care and overprotection) would demonstrate continuity with the next generation (G2).

• Hypothesis 2: A history of MDD after the age of 16 years (MDD episodes that developed after the period of parenting styles being reported on using the PBI) in G1 would account for the association between G1 childhood experiences of maladaptive parental rearing styles (lack of care and high overprotection during the first 16 years of life) and the way their own G2 children experienced the parenting they provided.

• Hypotheses 3a and 3b: Greater social support from a partner and/or extended family members during childrearing years (hypothesis 3a) and having an easy temperament in G1 (hypothesis 3b) would provide protective buffers against the cyclical intergenerational continuity of childhood experiences of overprotective and less caring parental styles.

We then further tested if similar mechanisms (hypotheses 1–3) would be involved in the continuity/discontinuity of parenting styles in the next parent→offspring cycles. See intergeneration model B in Figure 1 – G2+S(parents)→G3(children), for those G2+S who had children (G3).

Finally, using the subsample of families where there were three successive generations (grandparents, parents, and children), we examined the transmission of perceived parenting across three generations (G1→G2→G3).

Method

The Institutional Review Board of the New York State Psychiatric Institute approved the study procedures. Adult participants provided informed consent; minors provided informed assent and a parent/guardian provided consent.

Study design and participants

Data were derived from a three-generation (up to 38 years) longitudinal study of families at high and low risk for MDD (Weissman, Berry et al., Reference Weissman, Berry, Warner, Gameroff, Skipper, Talati and Wickramaratne2016; Weissman, Wickramaratne et al., Reference Weissman, Berry, Warner, Gameroff, Skipper, Talati and Wickramaratne2016). The three-generation cohort began with the recruitment of two groups of adult probands. The first group (depressed group) had moderate to severe MDD and was seeking treatment at outpatient facilities. The second group (nondepressed group) was recruited from the same community and had no MDD or lifetime psychiatric history, as determined by several interviews. The participants were all of European descent, as was the norm for family studies when this study began in 1982, and predominantly Catholic. Clinical data and reported parental bonding, social support, and temperament were collected across 38 years – at Year 0 (baseline) and in subsequent waves at Years 2, 10, 20, 25, 30, and 38. The second generation (G2) and their spouses (G2+S) and the third generation (G3) of offspring were included in the study as they aged: G2 was entered at Year 0 or Year 2; G3 started to enter at Year 10. Further descriptions of the study design and longitudinal follow-up can be found elsewhere (Weissman, Berry et al., Reference Weissman, Berry, Warner, Gameroff, Skipper, Talati and Wickramaratne2016; Weissman, Wickramaratne et al., Reference Weissman, Berry, Warner, Gameroff, Skipper, Talati and Wickramaratne2016).

• G1(parents)→G2(children) (hypotheses 1–2; Figure 1a) included 367 parents–children pairs, from 83 original families (high risk = 57, low risk = 26): 133 G1 (79 probands and their 54 spouses) [age completing the PBI: 28–74 years; 75 females (57.6%)] and their 229 corresponding G2 biological offspring [age completing the PBI: 16–41 years; 128 females (55.7%)].

• G2+S(parents)→G3(children) (Figure 1b) included 223 parents–children pairs, from 111 G2+S (70 biological offspring of G1 and their 41 spouses) [age completing the PBI: 15–56 years; 64 females (57.7%)] and their 136 corresponding G3 biological offspring [age completing the PBI: 15–31 years; 67 females (50.3%)].

• G1(grandparents)→G2(parents)→G3(children): There was an overlap of 67 G2 participants between the first model (G1→G2) and the second model (G2+S→G3). These 67 G2 participants [43 females (44.2%)] had 58 G1 parents [35 females (60.3%)] and 133 G3 children [67 females (50.3%)] (i.e., 58 G1→67 G2→133 G3], from 39 original families.

Measures

Parental bonding style

Offspring reports of parental care and overprotection in childhood were measured by the PBI (Parker et al., Reference Parker, Tupling and Brown1979) from study entry up to Year 30 (i.e., Years 2, 10, 20, and 30). The parental care dimension ranges from affection, closeness, empathy, and reciprocity (high scores) to rejection, coldness, and indifference (low scores), including items such as “my parent spoke to me in a warm and friendly voice,” “my parent appeared to understand my problems and worries,” “my parent was affectionate to me,” and “my parent could make me feel better when I was upset.” The parental overprotection domain ranges from overprotection, extensive intrusion, control, and infantilization (high scores) to the promotion of independence and autonomy (low scores), including such items as “my parent tried to control everything I did,” “my parent did not want me to grow up,” “my parent tried to make me feel dependent on her/him,” and “my parent invaded my privacy.” The PBI developers defined “optimal parenting” as high levels of care and low levels of overprotection (Parker et al., Reference Parker, Tupling and Brown1979). The respondents (over 16 years of age) reported their parents’ parenting styles during their first 16 years of life. In the current study, PBI values were obtained from retrospective reports at the earliest wave (=Year) to minimize the effect of memory distortions. The PBI consists of 25 items assessing the reports of parenting style/behaviors of each parent on a 4-point scale: participants indicated how much their parents were like each statement (0 = not at all to 3 = always). The PBI has survived many tests over the years and remains an important clinical moderator of outcomes in intergenerational research nearly 40 years after it was introduced (Wilhelm, Boyce, & Brownhill, Reference Wilhelm, Boyce and Brownhill2004). The validity of the PBI has been supported by many studies showing that subjects’ ratings correlated strongly with the ratings of their parents themselves, siblings, and impartial raters, including observational assessments of parental behavior, regardless of clinical state (Holmbeck et al., Reference Holmbeck, Johnson, Wills, McKernon, Rose, Erklin and Kemper2002; Murphy, Wickramaratne, & Weissman, Reference Murphy, Wickramaratne and Weissman2010; Steiger, Feen, Goldstein, & Leichner, Reference Steiger, Feen, Goldstein and Leichner1989). In addition, by administering the PBI to depressed persons and repeating this when they remitted, we have previously shown that the care and overprotection scores were stable over time in the current sample (Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Wickramaratne and Weissman2010).

The Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia

The Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia – Lifetime Version (SADS-L) is a semi-structured interview providing detailed information on a variety of DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) diagnoses, including affective and anxiety disorders (Mannuzza, Fyer, Klein, & Endicott, Reference Mannuzza, Fyer, Klein and Endicott1986). At each wave (=Year) of the study, participants over age 18 years were interviewed with a version of the SADS-L; otherwise they were interviewed with a child/adolescent version (K-SADS) (Kaufman et al., Reference Kaufman, Birmaher, Brent, Rao, Flynn, Moreci and Ryan1997). Interviews were conducted by trained doctoral or master's level mental health professionals who were blinded to the clinical status of the parents and other generations. Final diagnoses for all participants were based on the best-estimate procedure, commonly used in psychiatric interviews (Leckman, Sholomskas, Thompson, Belanger, & Weissman, Reference Leckman, Sholomskas, Thompson, Belanger and Weissman1982). At each wave of our study, a PhD or MD clinician who was not involved in interviewing the participant directly best-estimated current and lifetime diagnoses by reviewing the most recent SADS-L/K-SADS interview and clinical narrative written by the interviewer, as well as the interviews and narratives from earlier waves, which could shed additional light on current symptoms. Participants who were ever diagnosed with MDD with definite certainty via the best-estimate procedure are classified in this paper as having a lifetime MDD; otherwise, they are classified as not having a lifetime MDD (1 = yes; 0 = no). At each wave, the best-estimate procedure was also used to rate each participant on the Global Assessment Scale. A life chart was used during the interview to enable the identification of developmental patterns in the offspring. Training remained the same across all data collection waves (for a full description of training, see Weissman, Fendrich, Warner, & Wickramaratne, Reference Weissman, Fendrich, Warner and Wickramaratne1992). Interrater reliability for depressive disorders has been shown to be very high, as previously reported (Weissman et al., Reference Weissman, Wickramaratne, Nomura, Warner, Verdeli, Pilowsky and Bruder2005). Diagnoses were cumulative across all waves of data collection. DSM-IV diagnoses at the definite level of certainty were used. A definite diagnosis required five out of the nine criteria for MDD to be met, with a duration of depressed mood or loss of interest for 2 weeks or more. In the current analyses, as a mediator, we used the history of MDD following the first 16 years of life and up to the age at which her/his particular child turned 16 years old (1 = history of MDD; 0 = no history of MDD).

Parental social support (from partner and/or extended family)

Social support was assessed at study entry up to Year 38 (i.e., Years 2, 10, 20, 25, 30, and 38) using two specific roles/scales areas from the Social Adjustment Scale – Self-Report (SAS-SR), a 54-item widely used, reliable and validated measure of social role functioning (Weissman & Bothwell, Reference Weissman and Bothwell1976), and its: (a) primary relationship (relationship with one's romantic partner) (9 items) and (b) relationship with extended family members (8 items). Each question was rated on a 5-point scale, with a higher score indicating greater social impairment. The aggregate measure of social/family support (averaged across the two roles) provided an index of support from partner and extended family members (Cronbach's alpha = .78). In some waves we used SAS-SR short, an officially shortened but largely equivalent version of the SAS-SR (Gameroff, Wickramaratne, & Weissman, Reference Gameroff, Wickramaratne and Weissman2012), yielding the same role area scores.

Parental temperament

The Dimensions of Temperament Scale – Revised (Windle & Lerner, Reference Windle and Lerner1986) was used to assess parents’ self-reports of their temperament at Year 20 and Year 25. This 54-item questionnaire was used to measure nine attributes of temperament (Windle & Lerner, Reference Windle and Lerner1986), with Cronbach's alphas in parentheses: activity level – general (.84), activity level – sleep (.89), approach–withdrawal (.85), flexibility–rigidity (.78), mood quality (.89), rhythmicity – sleep (.78), rhythmicity – eating (.80), rhythmicity – daily habits (.62), distractibility (.81), and persistence (.74). Participants rated items using a 4-point Likert scale. We used the average temperament scores (averaged across all nine dimensions) to assess the overall temperament of each participant. Higher scores on the averaged temperament scale indicated an easier temperament (e.g., more adaptability to approach new situations, people, or events; greater flexibility; greater level of a positive quality of mood), while lower scores indicated a more difficult temperament.

Data analytic plan

The study described is a three-generation longitudinal study. G1 probands were recruited, with the inclusion criterion of having one or more children who also participated in the study. The subsequent follow-up of G2 and G3 were naturalistic, with no further study inclusion/exclusion criteria imposed. Of G2, 161 did not have children or had children who were too young to participate. Given this design, we opted a priori to examine our main hypotheses in G1→G2 first, and then to test whether similar patterns of continuity were observed from G2+S→G3 and, for the families where there were three consecutive generations, continuity from G1→G2→G3. The analyses described below were based on this design.

We conducted hierarchical, two-level structural equation modeling, implemented to account for the nested family structure, to examine the transmission of parental styles and their psychosocial mechanisms (mediation and moderations) (Table 1 shows the bivariate correlations). Data were analyzed with SPSS v26 and lavaan package in R (Rosseel, Reference Rosseel2012). To test for indirect effects in these models, we used bootstrapping (2,000 samples, 95% confidence interval). Model fit was assessed using the comparative fit index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). CFI values closer to 1 indicate better fit, with CFI ≥ .90 reflecting an adequate fit (Hu & Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1999; West, Taylor, & Wu, Reference West, Taylor, Wu and Hoyle2012). RMSEA ≤ .08 is considered acceptable (Hu & Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1999), whereas RMSEA ≥ .10 reflects a poor fit (Browne & Cudeck, Reference Browne, Cudeck, Bollen and Long1993). RSMR < .10 is indicative of adequate fit; RSMR < .05 indicates good model fit (Hu & Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1999; Iacobucci, Reference Iacobucci2010; Kline, Reference Kline2011; Schermelleh-Engel, Moosbrugger, & Müller, Reference Schermelleh-Engel, Moosbrugger and Müller2003). Missing data were accounted for using full information maximum likelihood estimation for individuals who participated in the study and had at least partial data. Data were missing for the following variables: G1 father overprotection (0.5%); G1 PBI age of completion (0.5%); G1 social support (16%); G2 father overprotection (0.1%); G2 PBI age of completion (0.1%); G2+S social support (29%); G2+S temperament (35%). For variables with more than 5% of data missing, which can lead to biased estimates (Dong & Peng, Reference Dong and Peng2013; Graham, Reference Graham2009; Jeličić, Phelps, & Lerner, Reference Jeličić, Phelps and Lerner2009; Newman, Reference Newman2003), we checked for differences between individuals whose data were and were not missing on the main parental variables that were included in all models. With regard to outcomes, those with missing G1 social support scores did not differ from participants without missing G1 social support scores on average G2 overprotection, t (365) = 0.77, p > .1, but did differ on average G2 care, t (365) = −2.30, p = .022. Participants with missing G2 social support scores did not differ on either average G3 overprotection, t (221) = −1.59, p > .1, or average G3 care, t (221) = 0.52, p > .1. Finally, participants with missing G2 temperament scores did not differ on either average G3 overprotection, t (221) = −1.79, p > .1, or average G3 care, t (221) = −1.96, p > .1. This suggests that, with respect to social support and temperament, participant data were not missing completely at random. Only one outcome – G2 perceived care – differed based on the missing variables, and none differed for perceived overprotection. Confirmatory factor analysis was used to test whether a two-factor latent variable model fitted parental care (factor 1; maternal and paternal) and overprotection (factor 2; maternal and paternal), but this did not provide an adequate fit to the data for either model (e.g., RMSEA = .205 and .211). Next, we assessed the fit of models with maternal and paternal care and overprotection included separately. Overall, this provided a poorer fit to the data relative to average scores (e.g., for G1→G2 model with parents’ parenting variables included as separate PBI scores, CFI = .83, RMSEA = .080, SRMR = .030, vs. CFI = .97, RMSEA = .057, SRMR = .035 for average parents’ PBI scores).

Table 1. Bivariate correlations of study variables

Note: Higher scores in social/family support scale denote less social support from partner and extended family members during the first 16 years of childrearing; higher scores in parental care denote higher parental sensitivity and warmth; higher scores in parental overprotection denote higher parental intrusiveness; higher scores in temperament (Dimensions of Temperament Scales – Revised) denote “easier” temperament characteristics. G1 = generation 1; G2 = generation 2; S = spouses; G3 = generation 3

a p < .1; *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

For all final analyses, we used the average of the mother's and father's care and overprotection scores as indexed of one's bonding to one's parents (i.e., G1 experiences of total parenting style received in childhood and G2+S experiences of total parenting styles received in childhood), as shown in previous studies (e.g., Feldman, Gordon, & Zagoory-Sharon, Reference Feldman, Gordon and Zagoory-Sharon2011; Gordon et al., Reference Gordon, Zagoory-Sharon, Schneiderman, Leckman, Weller and Feldman2008). This decision was based on the following three considerations.

• We did not have specific hypotheses for care and/or overprotection provided by mothers or fathers (see Abraham, Zagoory-Sharon, & Feldman, Reference Abraham, Zagoory-Sharon and Feldman2021; Feldman, Reference Feldman2021).

• G1 and G2+S PBI scores on their mothers’ and fathers’ parenting styles were strongly correlated in the G1→G2 and G2+S→G3 models, respectively (Table 1).

• We had concerns with the latent factor fit, given that separating mother's and father's PBI scores yielded a poorer model fit.

In the current analyses, to ensure that the predictor and mediator were in distinct chronological order, we used a history of MDD following the first 16 years of life until the first 16 years of childrearing as a mediator (history of MDD = 1; no history of MDD = 0) in order to separate the periods of parental styles/PBI (first 16 years of life) from a history of MDD (following the first 16 years of life until the first 16 years of childrearing).

Age at the time of parent–child bonding (PBI) assessment, parent sex, offspring sex, and socioeconomic status (education and household income) were all included in the analyses as potential confounding variables. Familial risk for MDD (defined as “high risk” if G1 probands had a history of MDD; otherwise, defined as “low risk”) was included as a covariate in the G2+S(parents)→G3(children) analyses.

Results

Preliminary analysis

Bivariate correlations of the study variables are shown in Table 1 and descriptive statistics of parenting styles across generations are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Mean and standard deviation (SD) of parenting (PBI) variables

Note: PBI = Parental Bonding Instrument; G1 = generation 1; G2 = generation 2; S = spouses; G3 = generation 3

Hypothesis 1: G1(parents)→G2(children) intergenerational continuity of experiences of childhood care and overprotection

The model provided a good fit to the data (CFI = .97, RMSEA = .057, SRMR = .035). The effect of G1(parent) perceived care (i.e., G1 experiences of care received from their parents in childhood) on G2(children) perceived care was significant (β = .22, SE = .05, p < .001). The effect of G1 perceived overprotection on G2 perceived overprotection was also significant (β = .23, SE = .05, p < .001). The correlation between G1 perceived care and overprotection (r = −.55, p < .001) and G2 perceived care and overprotection was also significant (r = −.39, p < .001). When the data were stratified by G1 sex, the results indicated a similar pattern of intergenerational continuity of parenting styles in both mothers and fathers. For mothers, their perceived care was associated with their offspring perceived care (β = .15, SE = .06, p = .02) and perceived overprotection was associated with G2 perceived overprotection (β = .27, SE = .07, p < .001). For fathers, their perceived care was associated with G2 perceived care (β = .35, SE = .07, p = .002) and perceived overprotection was associated with G2 perceived overprotection (β = .23, SE = .08, p = .003). In other words, experiences of care and overprotection received from parents in childhood appeared to be transmitted from one generation to the next (i.e., from G1→G2).

Hypothesis 2: G1(parents)→G2(children) mediation (history of MDD)

Overall, the model provided a good to acceptable fit to the data (CFI = .90, RMSEA = .078, SRMR = .026; see Figure 2a). As shown in Figure 2a, the direct effect of G1 perceived care on G2 perceived care was significant (path c: β = .17, p = .001). Lower levels of parental care when G1 were children were related to the development of MDD after the age of 16 in G1 (path a: β = −.14, p = .003), which, in turn, was associated with G2 receiving less care from their parents (G1) in childhood (path b: β = −.14, p = .005), with a significant total effect across paths a and b (β = .19, p < .001). The indirect effect of G1 perceived care on G2 perceived care via a history of MDD in G1 was significant (indirect effect: β = .02, p = .036), indicating partial mediation. A history of MDD in G1 did not mediate the associations between G1 perceived overprotection and G2 perceived overprotection (see Figure 1a of the Supplementary Material). In other words, the development of MDD in G1 after the age of 16 accounted for the intergenerational transmission of experiences of low care received in childhood in the G1→G2 cycle.

Figure 2. Results of structural equation modeling. Standardized parameter estimates and standard errors are presented for structural equation models testing the psychosocial mechanisms (parent's history of major depressive disorder (MDD) after the age of 16 years as a mediator; parent's social support and temperament as moderators) underlying the intergenerational transmission of parenting styles, as perceived by offspring. G1 = generation 1; G2 = generation 2; S = spouses; G3 = generation 3. (a) Intergeneration model A: G1→G2, N = 133 G1 and N = 229 G2 (hypotheses 1–3). (b) Intergeneration model B: G2+S→G3, N = 111 G2+S and N = 136 G3. “Perceived care/overprotection” = individual reported her/his experiences of caring/overprotective parenting (by her/his parents) in childhood, respectively. Higher scores in social/family support scale denote less social support from partner and extended family members during the first 16 years of childrearing; higher scores in parental care denote higher parental sensitivity and warmth; higher scores in parental overprotection denote higher parental intrusiveness; higher scores in temperament (Dimensions of Temperament Scales – Revised) denote “easier temperament.” History of MDD (0 = no; 1 = yes). Age at time of parent–child bonding (PBI) assessment, parent sex, and offspring sex (0 = female; 1 = male) were all included in the analyses as potential confounding variables. Familial risk for MDD (0 = low; 1 = high) was included as a covariate in the G2+S→G3 analyses. G1 = generation 1; G2 = generation 2; G3 = generation 3. ᛭ p < .1; *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001. ▵in model B = although the interaction between G2(+S) perceived parental overprotection and their temperament did not reach the level of significance when social support was included in the model, it was significant when social support was not included in the model.

Hypotheses 3: G1(parents)→G2(children) moderations (social support and temperament)

There was a main effect of G1 perceived overprotection on G2 perceived overprotection (β = .14, p = .003), but no main effects of G1 social support (β = .07, p > .05) or G1 temperament (β = −.08, p > .1) on G2 perceived overprotection. The main effect of G1 perceived overprotection on G2 perceived overprotection was qualified by significant interactions: (a) G2 Perceived Overprotection × G2 Social Support (β = .11, p = .048) (hypothesis 3) and (b) G1 Perceived Overprotection × G1 Temperament (β = −.12, p = .023) (hypothesis 4). Simple slope tests were used to follow up on the significant interactions. For each test, ±1.5 standard deviations (SD) above and below the mean of the standardized variables were used to examine effects at “high” and “low” levels of the moderators. As shown in Figure 3a, at lower levels of G1 social support (+1.5; higher scores denote lower social support), but not at higher levels (−1.5), G1 perceived overprotection predicted G2 perceived overprotection (β = .33, SE = .09, p < .001; Figure 3a1); whereas at lower levels of temperament (difficult temperament; −1.5), but not at higher levels (+1.5), G1 perceived overprotection predicted G2 perceived overprotection (β = .34, SE = .07, p < .001; Figure 3a2). Neither the interaction between G1 Perceived Care × G1 Social Support (β = −.03, SE = .05, p > .1), nor G1 Perceived Care × G1 Temperament (β = −.02, SE = .04, p > .1) predicted G2 perceived care; thus, these variables did not moderate the relationship between G1 perceived care and G2 perceived care. In other words: (a) G1 parental social support from partner and extended family moderated the association between experiences of overprotection received in childhood, from G1→G2, with stronger associations for those having low social support during childrearing; (b) G1 parental temperament moderated the association between experiences of overprotection received in childhood from G1→G2, with stronger associations for those with a difficult temperament.

Figure 3. Moderating effects of parental social support and temperament. Experiences of parents’ overprotective style in childhood predicting child's experiences of overprotection in childhood as moderated by parental social support (from partner and/or extended family) and temperament. “Perceived overprotection” = individual reported her/his experiences of overprotective parenting (by her/his parents) in childhood. G1 = generation 1; G2 = generation 2; S = spouses; G3 = generation 3. (a) Intergeneration model A (G1→G2): (1) interactive effects of G1 perceived overprotection and G1 social/family support (during childrearing) on G2 perceived overprotective parental style, with a significantly stronger positive association (significant slopes) only for those with low social support (higher scores of social support scale) during childrearing. (2) interactive effects of G1 overprotection and G1 temperament on G2 perceived overprotection, with a significantly stronger positive association (significant slopes) only for those with difficult temperament (lower scores on the Dimensions of Temperament Scales – Revised) (hypotheses 3). (b) Intergeneration model B (G2+S→G3): (1) interactive effects of G2+S perceived overprotection and G2+S social/family support (during childrearing) on G3 perceived overprotection, with significantly stronger positive association (significant slopes) only for those with low social/family support during childrearing. (2) interactive effects of G2+S perceived overprotection and G2+S temperament on G3 perceived overprotection, with a significantly stronger positive association (significant slopes) only for those with a difficult temperament. G1 = generation 1; G2 = generation 2; G3 = generation 3. (ns) p > .1; ***p < .001. For each test, ±1.5 standard deviations above and below the mean of the standardized variables were used to examine effects at “high” and “low” levels of the moderator.

G2+S(parents)→G3(children)

(a) Intergenerational continuity of experiences of childhood care and overprotection. The model provided a good fit to the data (CFI = .97, RMSEA = .067, SRMR = .027). The effect of G2+S perceived care (i.e., their experiences of care received from their parents in childhood) on G3 perceived care was significant (β = .31, SE = .06, p < .001). The effect of G2+S perceived overprotection on G3 perceived overprotection was also significant (β = .19, SE = .06, p = .002). The correlations between G2+S care and overprotection (r = −.35, p < .001) and G3 care overprotection were also significant (r = −.38, p < .001). When the data were stratified by G2+S sex, the results indicated a similar pattern of intergenerational continuity of parenting styles in mothers and fathers. For mothers, their perceived care was associated with G3 perceived care (β = .28, SE = .08, p = .003) and perceived overprotection was associated with G3 perceived overprotection (β = .18, SE = .10, p = .051). For fathers, their perceived care was associated with G3 perceived care (β = .22, SE = .13, p = .049) and perceived overprotection was associated with G3 perceived overprotection (β = .18, SE = .12, p = .06). In addition, there was no interaction between the familial risk status for MDD (i.e., G1 probands MDD) and G2 perceived parenting in predicting G3 perceived parenting (care: β = .09, SE = .54, p > .1; overprotection: β = .08, SE = .49, p > .1).

(b) Mediation. Overall, the model provided a good to acceptable fit to the data (CFI = .90, RMSEA = .080, SRMR = .031; see Figure 2b). While G2+S perceived care predicted G3 perceived care (direct effect, path c: β = .24, p = .001) and G2+S perceived care predicted a history of MDD in G2+S (path a: β = .26, p < .001), a history of MDD in G2+S (from age 16 years) did not predict G3 perceived care (path b: β = .06, SE = .16, p > .1). Therefore, G2 history of MDD was not a mediator for the association between G2+S perceived care and G3 perceived care (indirect effect: β = .02, p > .1). In addition, a history of MDD in G2+S did not mediate the associations between their perceived overprotection and G3 perceived overprotection (see Figure 1b of the Supplementary Material).

(c) Moderators. The main effect of G2+S perceived overprotection on G3 perceived overprotection was approaching significance (β = .11, p = .094). There were no main effects of G2+S social support (β = .08, SE = .08, p > .1) or temperament (β = −.06, SE = .07, p > .05) on G3 perceived overprotection. There was, however, a significant interaction between G2+S perceived overprotection and their social support (β = .17, p = .03). Although the interaction between G2+S perceived overprotection and their temperament did not reach the level of significance when social support was included in the model (β = −.11, p > .1), it was significant when social support was not included in the model (β = −.18, SE = .06, p = .016). As shown in Figure 3b, at lower levels of G2+S social support (+1.5; higher scores denote lower social support), but not at higher levels, their perceived overprotection predicted G3 perceived overprotection (β = .33, p < .001; Figure 3b1). At lower levels of temperament (difficult temperament; −1.5), but not at higher levels, G2+S perceived overprotection predicted G3 perceived overprotection (β = .37, p < .001; Figure 3b2). Similar to G1→G2, neither the interaction between G2+S perceived parental care and social support (β = .16, SE = .08, p > .1) nor G2+S perceived parental care and temperament (β = .11, SE = .10, p > .1) significantly predicted G3 perceived care; thus, these variables did not moderate the relationship between G2+S perceived care and G3 perceived care.

In other words: (a) G2+S experiences of care and overprotection received from parents in childhood appeared to be transmitted from one generation to the next, from G2+S→G3; (b) G2+S social support from partner and extended family moderated the G2+S→G3 experiences of overprotection, with stronger associations for those G2+S having low social support during childrearing; (c) G2+S temperament moderated the association between G2+S→G3 experiences of overprotection, with stronger associations for those G2+S with a difficult temperament.

Multigenerational [G1(grandparents)→G2(parents)→G3(children)] continuity of experiences of childhood care and overprotection

This model provided a good fit to the data (CFI = .94, RMSEA = .078, SRMR = .059; see Figure 4). In a subsample of 39 families with three successive generations, we found that while G1 perceived care predicted G2 perceived care (path a: β = .38, p < .001), it did not predict G3 perceived care (path c: β = .07, p > .1). In addition, G2 perceived care did not predict G3 perceived care (path b: β = −.03, p > .1). As for perceived overprotection, we found that while G1 perceived overprotection predicted G2 perceived overprotection (path a: β = .23, p < .001), it did not predict G3 perceived overprotection (path c: β = .07, SE = −.07, p > .1). However, G2 perceived overprotection predicted G3 perceived overprotection (path b: β = .17, SE = .07, p = .013). We found a significant indirect (i.e., mediation) effect (indirect effect: β = .04, p = .039), indicating that G1 experiences of overprotection received in childhood were indirectly associated with G3 experiences of overprotection received in childhood (from G2), via G2 experiences of overprotection received in childhood (from G1).

Figure 4. Results of structural equation modeling results for three successive generations (G1→G2→G3). Standardized parameter estimates and standard errors are presented for structural equation models testing the multigenerational transmission of parenting styles in a subsample of families with three successive generations (G1→G2→G3; 39 original families; 58 grandparents, 67 parents, 133 children). “Perceived care/overprotection” = individual reported her/his experiences of caring/overprotective parenting (by her/his parents) in childhood, respectively. G1 = generation 1; G2 = generation 2; S = spouses; G3 = generation 3. *p < .05; ***p < .001.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study of three generations is the first to investigate the transmission of parenting style – both adaptive and maladaptive aspects of parenting – across two consecutive parent→offspring cycles (and in a subsample of families with three successive generations), by focusing on individual differences in psychopathology, personality, and socialization as a potential psychosocial mechanism of intergenerational continuity/discontinuity.

Overall, we found continuity of experiences of parental care and overprotection received during childhood, from G1(parents)→G2(children). Low parental care and high parental overprotection during childhood, as experienced by G1, were associated with greater bonding difficulties with their own children (G2). A history of MDD in G1 mediated the association between their experiences of low parental care and the way they cared for their own children when becoming parents. The G1→G2 perceived overprotection continuity was mainly defined by interactive effects, so that G1 with low social/family support during childrearing and/or with difficult temperamental traits repeated their parents’ maladaptive parenting practices (i.e., high overprotection) while growing up and becoming parents to G2. Moreover, the findings on intergenerational continuity/discontinuity of parenting were largely similar in the next parent→offspring cycle: (G2+S→G3). Finally, in the subsample of families where there were three successive generations – G1(grandparents), G2(parents), and G3(children) – we found that G1 experiences of overprotection showed continuity to the next two generations, that is, from G1→G2→G3, and that G1 experiences of overprotection were indirectly associated with their grandchildren's (G3) experiences of overprotection, via the G2 experiences of overprotection.

Our findings were based on independent offspring's reports in each generation: G3 rated their parents’ (G2+S) early parenting styles; G2+S rated their parents’ early parenting styles, and G1 rated their parents’ early parenting styles. This minimized systematic report bias, such as shared method variance and other potential confounding factors often present in multigenerational analyses (e.g., one informant reports on both experienced and actual parenting). Our findings were largely consistent across generational cycles (G1→G2 and G2+S→G3), which suggests that the first cycle has far-reaching generational consequences that do not dissipate and allowed us to be more confident about intergenerational continuity and its psychosocial mechanisms.

Four important aspects of the intergenerational transmission of human parenting

Our findings highlight four important aspects of the intergenerational transmission of human parenting.

First, we found continuity of parenting from G1(parents)→G2(children), which suggests that the previous generation's experiences of positive and maladaptive parenting style are accurately reflected in the next generation's experienced parenting. In addition, no sex differences were found in the intergenerational transmission of parenting styles, namely, the way mothers’/fathers’ early-life experiences of parenting received from their parents predicted the way they parented their own children. The findings are consistent with recent work in rodent models (Bales & Saltzman, Reference Bales and Saltzman2016) and humans (Abraham & Feldman, Reference Abraham and Feldman2018; Abraham, Hendler, Zagoory-Sharon, & Feldman, Reference Abraham, Hendler, Zagoory-Sharon and Feldman2016), highlighting that the caregiving of both parents contributes in quite similar ways to offspring development over time and suggesting that intergenerational pathways are supported by similar neural and hormonal pathways. Of note, in a subsample of families with three successive generations, we found multigenerational [G1(grandparents)→G2(parents)→G3(children)] continuity of overprotective parenting, but only G1→G2 (path a) continuity of caring parenting. In addition, there were no associations between G1 experiences of parenting and G3 experiences of parenting. One explanation may be that different socialization experiences have a greater impact and produce greater discontinuity between nonconsecutive generations. Another explanation is the reduced statistical power in the G1→G2→G3 model. Future studies with a larger sample size and complete multigenerational data in families are needed to further explore these differences.

Second, we found that MDD history in G1 accounted for the continuity of their experiences of low parental care, but not overprotection, during childhood from G1(parents)→G2(children); lower levels of parental care when G1 were children were related to the development of MDD from age 16 years, which, in turn, was associated with them providing less parental care to their own children (G2). This finding is in line with previous evidence showing that low care is more predictive for depression than is overprotection (Alloy et al., Reference Alloy, Abramson, Smith, Gibb and Neeren2006). Our findings corroborate previous studies that have identified parental rejection as a causal process of offspring depression (Garber & Flynn, Reference Garber and Flynn2001). Those studies reported that depression is robustly linked with a range of social deficits, including poor caregiving (Hirschfeld et al., Reference Hirschfeld, Montgomery, Keller, Kasper, Schatzberg, Moller and Versiani2000). Studies have also shown that parents who are prone to negative emotional states, such as depression, tend to behave in less sensitive, less responsive, and more hostile ways than other parents (Wilson & Durbin, Reference Wilson and Durbin2010), even those who were not currently depressed but have experienced past depressive episodes (Lovejoy et al., Reference Lovejoy, Graczyk, O'Hare and Neuman2000). Our findings suggest a history of MDD as one of the mechanisms underlying the intergenerational risk for maladaptive parenting style. It is important to note that while depression can bias memory towards negative events, we and other researchers have previously found stability of the PBI scales over 20 years, regardless of clinical state (e.g., Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Wickramaratne and Weissman2010; Wilhelm, Niven, Parker, & Hadzi-Pavlovic, Reference Wilhelm, Niven, Parker and Hadzi-Pavlovic2005).

Third, we found that the social support of G1(parents), in particular the extent to which an individual's emotional, informational, and instrumental needs were satisfied through interactions with their partner and extended family members during childrearing, moderated the association between G1→G2 experiences of parental overprotection in childhood and overprotective practices toward their own children (G2). Our findings suggest that individuals who experienced maladaptive caregiving (i.e., more extensive intrusion, control, and infantilization) from their parents during childhood but did not repeat these maladaptive parenting practices while growing up and becoming parents had experienced supportive close relationships with their partner and extended family members. Our finding, in concert with those of previous studies, confirms the role of social support in promoting physical and psychological health and overall wellbeing to the individual and offspring across the life span (Pierce et al., Reference Pierce, Sarason, Sarason, Joseph, Henderson, Pierce, Sarason and Sarason1996). In addition, this finding is consistent with previous animal and human studies highlighting the social buffering effect across the life span (Gunnar & Hostinar, Reference Gunnar and Hostinar2015) and showing that social attachments, including pair bonding, friendship, and family bonds, have been found to moderate both genetic and environmental vulnerabilities and confer resilience to stress and adversity (Abraham et al., Reference Abraham, Posner, Wickramaratne, Aw, van Dijk, Cha and Talati2020; Feldman, Reference Feldman2020; Levy & Feldman, Reference Levy and Feldman2019; Schury et al., Reference Schury, Zimmermann, Umlauft, Hulbert, Guendel, Ziegenhain and Kolassa2017; Vakrat, Apter-Levy, & Feldman, Reference Vakrat, Apter-Levy and Feldman2018).

Fourth, we found that the temperament of G1(parents) moderated the links between their experiences of childhood parental overprotection and their overprotective practices toward their own children in G1→G2. G1 with difficult temperament were more vulnerable to adopting their parents’ overprotective style than those having an easier temperament. The findings are in line with research characterizing easy temperament as one of the individual protective factors and as a behavior regulation mechanism (Cederblad, Dahlin, Hagnell, & Hansson, Reference Cederblad, Dahlin, Hagnell and Hansson1995), and difficult temperament as a risk factor predicting the emergence of emotional and behavioral disorders across the life span, including dysfunctional parental care (McCrae et al., Reference McCrae, Costa, Ostendorf, Angleitner, Hřebíčková, Avia and Smith2000). In addition, the findings support developmental research on the moderating effect of child temperamental characteristics on the association between early parenting and child adjustment (Gallagher, Reference Gallagher2002). Overall, our findings suggest that temperament, as well as social support from partner and/or extended family, buffered the effect of negative early-life experiences on the way offspring parented their children. The crossover pattern evident in the interaction plots (Figure 3) may suggest that parents with a difficult temperament and/or lower social support who had experienced lower levels of maladaptive parenting (low overprotection) during childhood provided lower levels of maladaptive parenting to their children, compared with parents with an easy temperament and higher social support who had experienced lower levels of maladaptive parenting in their childhood. While the patterns of the findings may indicate support of the differential susceptibility hypothesis (e.g., Belsky & Pluess, Reference Belsky and Pluess2009), testing these effects was beyond the scope of the current work and future studies of larger cohorts should examine them.

Finally, we showed that the findings in the G2+S(parents)→G3(children) cycle were largely similar to those found in the first parent→children cycle (G1→G2); namely, a continuity of positive and negative aspects of parenting from G2+S→G3, and G2+S social support and temperament moderated the intergenerational continuity of overprotective parenting. Interestingly, a history of MDD in G2+S did not account for the association between G2+S→G3 experiences of either caring or overprotective parenting. Differences between the mediating effect of MDD for G1→G2 (stronger) and G2+S→G3 (weaker) could be related to different sample sizes, differences in depression severity and persistence (G1 MDD = individuals with moderate to severe MDD, seeking treatment at outpatient facilities vs. individuals without MDD and other psychiatric disorders; G2+S = individuals with MDD with and without impairment vs. those without other psychiatric conditions), and timing of collection.

Limitations and future studies

A few study limitations merit consideration. First is our reliance on an individual's retrospective report of the parenting that was received while growing up. Future studies should consider integrating self-report and observational measures (e.g., coding parent–offspring social interactions) to evaluate parenting behavior and parent–offspring bonding during early childhood in order to confirm our findings. Second, we did not have sufficient data on resident status (e.g., single-parent/dual-parent households) and thus could not consider this as a covariate in the analyses. Third, our sample size of three successive generations in a family was underpowered to investigate multiple mediations and/or moderations. Therefore, we investigated our hypotheses on two separate parent→child cycles. Nevertheless, our study presents a unique three-generation cohort and this study is a good first step toward justifying further studies investigating the psychosocial mechanisms underpinning the intergenerational transmission of human parenting across multiple generations. Future studies with larger sample sizes and multigenerational data in families are needed to explore our hypotheses further. Fourth, our sample was of European ancestry, as was the norm for family studies when the project originated, and thus our findings may not generalize to other population subgroups (Fujiwara et al., Reference Fujiwara, Weisman, Ochi, Shirai, Matsumoto, Noguchi and Feldman2019; Kitamura et al., Reference Kitamura, Shikai, Uji, Hiramura, Tanaka and Shono2009). Since parenting embeds cultural models and meanings into basic psychological processes that maintain or transform the culture, and culture expresses and perpetuates itself through parenting practices (Bornstein, Reference Bornstein and Sameroff2009; Feldman & Masalha, Reference Feldman and Masalha2010; Feldman, Masalha, & Derdikman-Eiron, Reference Feldman, Masalha and Derdikman-Eiron2010), it is critical to conduct more studies on the psychosocial mechanisms underlying the intergenerational transmission of parenting practices across various cultures before the findings can be generalized. The cultural and historical context of intergenerational patterns of parenting and their evolution over generations should be further studied. Finally, while this study focused on the characteristics of the parent and the social environment as putative psychosocial mechanisms, future studies should explore the child's contribution to the process of parenting (Belsky, Reference Belsky1984) as a potential mechanism for the intergenerational continuity of parenting.

Conclusion

Using our unique three-generation longitudinal design with richly characterized clinical, psychological, and social functioning data over time, we were able to provide new insights into the psychosocial mechanisms underpinning the continuity/discontinuity of parenting styles in subsequent generations – depression, parental temperamental traits, and social support from partner and extended family – which may be useful to the planning of further studies as well as timely interventions to “break the cycle” of early adversity across generations. Early treatment of depression that reduces current symptoms and the rate of depressive relapse, and at early stages in symptom presentation before the course of a disorder crosses the clinical threshold, is needed to mitigate the likelihood of problematic parenting in later life stages (Muñoz & Weissman, Reference Muñoz and Weissman2020). In addition, since individual differences in temperamental reactivity and regulation are also critically molded by the social environment and experiences (Rothbart & Bates, Reference Rothbart, Bates, Damon and Eisenberg1998), specific strategies directed to help parents who have more difficulty in regulating their emotions and behavior to cope with stress and interact with their young children (e.g., appropriate and consistent response to infant signals, positive regard) might be targets of interventions. Finally, more focus on evidence-based psychotherapy that provides strategies to resolve relational problems that disrupt social support and increase interpersonal stress may assist parents to deal better with difficulties in parenting, regardless of their own early-life nurturing experiences.

Supplementary Material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579421000420.

Funding Statement

This work was supported in part by grant R01 MH-036197 from the National Institute of Mental Health (MMW and JP, Principal Investigators). In the last three years, Dr. Weissman has received research funding from the National Institute of Mental Health, the Brain and Behavior Foundation, the Templeton Foundation, and the Sackler Foundation, has received book royalties from Perseus Press, Oxford Press, and APA Publishing, and receives royalties on the Social Adjustment Scale from Multi Health Systems. None of these are a conflict of interest. Dr. Weissman received no royalties from the SAS-SR used in this study. Dr. Posner's research has been supported by Takeda (formerly Shire) and Aevi Genomics. None of these present any conflict with the present work, and no other authors report any disclosures.

Conflicts of Interest

None