INTRODUCTION

Although previous studies recognize that the expression of futurity in French can be accomplished in a variety of ways, most have consistently simplified the future-time reference sector to the two or three most frequent verb forms used to make reference to future time. In contrast, data from the present study will show that future-time expression in French in fact draws on a rich inventory of finite verb forms. Our main goal is to provide a more complete picture of verb forms used in future-time expression by a group of native speakers (NSs) and near-native speakers (NNSs)Footnote 1 of Hexagonal French engaging in informal conversation. To capture the full repertoire of verbal means appearing in future-time contexts, and to avoid a priori assumptions based on morphological form, we adopt a concept-oriented approach to the analysis of future-time expression. We agree with Kanwit (Reference Kanwit2014: 16), who writes, ‘[o]verall, concept-oriented approaches are highly justified, given that many linguistic functions are filled by multiple forms, such that limiting the list of permissible forms a priori results in an inadequate analysis that is certain to exclude the full account of forms that may be used in a given context’.

Our corpus allows us to contribute to research on both native and non-native French. The analysis of the NS portion contributes to discussions of the expression of future-time in Hexagonal French, which has received much less attention than Canadian varieties with respect to future-time expression. Moreover, the NS data provide an ecologically valid baseline against which to compare the expression of future time by our NNSs. As concerns non-native French, the current corpus allows us to examine to what extent forms used to make future-time reference by second-language (L2) speakers with proficiency at the highest levels of L2 attainment resemble NSs’ repertoires. In what follows, we begin by briefly discussing our analytical framework before reviewing previous studies on future-time reference in NS and L2 French. We then present what is, to our knowledge, the first concept-oriented study of future-time expression in NS and NNS Hexagonal French. Finally, we discuss our results and the importance of our findings for research on NS and L2 French.

BACKGROUND

In this study, we adopt a functional (and, in particular, concept-oriented) approach in order to examine future-time expression in French. Functional approaches to linguistics focus on the making of meaning within communication, and include variationist approaches (Aaron, Reference Aaron2010: 30), form-function approaches and concept-oriented approaches. Variationist sociolinguistic studies, for example, examine a variety of linguistic and extralinguistic factors that influence the choice of two or more means of expressing a similar notion. With respect to future-time expression in French, variationist studies have shown, among other things, that the presence of sentential negation or a temporal adverbial generally favours the use of the inflectional future over the periphrastic future (e.g. Poplack and Turpin, Reference Poplack and Turpin1999). Form-function approaches, on the other hand, track a single form throughout the language system in an attempt to understand the range of linguistic functions it fulfills (Ellis, Reference Ellis2008). For future-time expression, a form-function analysis of the IF would reveal not only this form's use in the expression of futurity, but also its use as a pseudo-imperative (tu poseras ce livre tout de suite!) or an epistemic (il n'est pas ici il sera malade [example from Jeanjean, Reference Jeanjean, Blanche-Benveniste, Chervel and Gross1988: 253]).

A concept-oriented (or function-form) approach aims to capture the full range of expression used for a given concept. In such studies, the researcher first identifies a concept (e.g. future-time reference) and then inventories and analyses all linguistic forms used to express this concept (Bardovi-Harlig, Reference Bardovi-Harlig, VanPatten and Williams2007; von Stutterheim and Klein, Reference von Stutterheim, Klein and Pfaff1987). We adopt this approach for the study of the future-time reference sector, arguing that it is particularly well suited to the study of different temporal domains. As L. de Saussure notes, ‘tenses do not or not only refer to the time(s) they should refer to according to their intuitive semantics: some present tense utterances tell about a past or a future; some utterances with a past tense tell about a present or a future; some future tense utterances are about the present or the past’ (Reference Saussure, Jaszczolt and de Saussure2013: 47).

Future-time reference in French

Most previous studies into future-time reference in French have presented a restricted view, concentrating on two or three verb forms: the inflectional future (IF), the periphrastic future (PF) and to a lesser extent the futurate present (also referred to as the present-for-future). Examples of each, drawn from the present corpus, appear in (1).

-

(1)

Poplack and Dion's comprehensive Reference Poplack and Dion2009 study shows that much previous research and grammatical commentary have held that these three forms largely occur in distinct future-time contexts. It has been contended that the IF shows a break from present time, making it particularly congruent with the expression of hypothetical (i.e. negative), distal and uncertain events. In contrast, because the PF is anchored in the present, it is argued that it is compatible with events set to occur in the proximal future, or with events that are certain to occur. The use of the futurate present is most often linked to the presence of a temporal adverbial (e.g. Blondeau, Reference Blondeau2006: 74; Le Goffic and Lab, Reference Goffic and Lab2001: 78; Moses, Reference Moses2002: 27). However, Poplack and Dion convincingly debunk such a clear-cut functional division among these forms, showing (a) striking inconsistencies across five centuries of grammatical tradition and (b) highlighting the necessity of empirical research in the study of future expression. For this reason, in the face of a large literature, we privilege empirical accounts of future-time expression in spoken French in our review of previous studies.

Future-time reference in NS French

There exist numerous studies into the expression of future-time reference in Laurentian (Blondeau, Reference Blondeau2006; Deshaies and Laforge, Reference Deshaies and Laforge1981; Emirkanian and Sankoff, Reference Emirkanian, Sankoff, Lemieux and Cedergren1985; Grimm, Reference Grimm2010, Reference Grimm2015; Grimm and Nadasdi, Reference Grimm and Nadasdi2011; Poplack and Dion, Reference Poplack and Dion2009; Poplack and Turpin, Reference Poplack and Turpin1999) and Acadian (Comeau, Reference Comeau2011; King and Nadasdi, Reference King and Nadasdi2003) varieties of French, almost all of which have concentrated exclusively on the two verb forms morphologically marked for future: PF and IF (cf. Poplack and Turpin, Reference Poplack and Turpin1999). In comparison, studies of future expression in Hexagonal French are underrepresented. Existing studies have examined the distributions of the two or three main verb forms in corpora with adult speakers (Fleury and Branca-Rosoff, Reference Fleury and Branca-Rosoff2010; Hansen and Strudsholm, Reference Hansen and Strudsholm2006; Jeanjean, Reference Jeanjean, Blanche-Benveniste, Chervel and Gross1988; Roberts, Reference Roberts2012; Wales, Reference Wales1983) or child participants (Söll, Reference Söll and Hausmann1983). For the present study, two particularly relevant findings with respect to IF and PF emerge from this body of research. First, previous authors have been interested in the overall frequency of verb forms used in the expression of future-time, although no consensus prevails: Whereas both Wales and Jeanjean report a predominance of IF, Fleury and Branca-Rosoff, Söll, and Roberts all find that the PF is the more frequent form.Footnote 2 Second, all studies except Wales examine how speakers use future-situating time adverbials when talking about the future, and all note a tendency for the IF to occur in the company of such adverbials, and in particular of non-specific ones (e.g., une fois).

The present tense, although generally recognized as a player in future expression, is rarely given the same attention as the forms carrying future morphology. In fact, we know of no empirical study on its use for future expression in spoken Hexagonal French. When it is discussed, the consensus is that the present must be accompanied by a future-time adverbial to be construed as making reference to the future. Moses’ (Reference Moses2002: 27) definition is representative of this view: the futurate present is ‘the use of present tense verb morphology accompanied by an obligatory future-marking time adverbial to express a chronologically future event’. Le Goffic and Lab (Reference Goffic and Lab2001: 77) also recognize that the presence of an explicit date is necessary, ‘sauf bien entendu si la date est implicite mais récupérable dans le contexte’.

Previous research into future-time expression in Hexagonal French thus leaves open numerous questions, of which three will receive particular attention in this article. First, no previous study has attempted to capture the full range of finite verb forms used in future-time contexts, concentrating instead on the IF and the PF. Second, disagreements persist as to the relative frequency of these two forms. Finally, although it is recognized that the present can be used in future-time contexts, in particular in the company of temporal adverbials, we know of no empirical investigation into its use.

Future-time reference in L2 French

Previous L2 research on future-time expression in spoken French has revealed several findings, two of which are relevant for the current study. First, previous studies have reported frequency of use for the PF, IF and present. Both Howard (Reference Howard2012) and Moses (Reference Moses2002) report that advanced university learners continue to underutilize the PF (as compared to the IF), even after a year abroad in the case of Howard's learners. Adolescents in an immersion setting (Nadasdi, Mougeon and Rehner, Reference Nadasdi, Mougeon and Rehner2003) and Anglophones living in Montreal (Blondeau, Dion and Ziliak Michel, Reference Blondeau, Dion and Ziliak Michel2014), on the other hand, come close to approximating the norm in Laurentian French (however, 14% of forms used by the immersion students were non-native). Second, two studies (Moses and Blondeau et al.) look beyond the PF, IF and futurate present. Blondeau et al. report that conditional forms occurred in some of the future-time contexts produced by their participants, whereas Moses finds future-time contexts expressed with the futur antérieur, the present subjunctive and lexical futures in the speech of his NSs and L2 learners.

Although these findings aid in understanding how L2 speakers of French make reference to future time, several issues remain unresolved, two of which will be examined in the present study. First, the findings suggest that nativelike approximation of the future-time reference sector (with respect to frequency, forms and linguistic factors) is difficult for even advanced learners; only Blondeau et al. (Reference Blondeau, Dion and Ziliak Michel2014) find that their learners, living in a target language environment, succeed. In this study, however, the authors concentrate on the use of the IF, PF and present, leaving open the question as to whether the L2 speakers rely solely on the major players in future-time expression. Second, Moses (Reference Moses2002) represents the only attempt to provide a full picture of future-time expression. His study, however, looked at 24 learners in a university setting (at four proficiency levels), and included only between 73 and 187 tokens per group. Additional work that will extend Moses’ findings to more advanced learners using a larger dataset is thus merited.

Research questions

Previous research on NS French has generally been limited to the IF and the PF. Whereas L2 research has investigated a wider palette of forms, no study has examined the full range used by NNSs to express future-time. For the first research question guiding the present project, we asked what finite verb forms are used to express the function of future-time reference in informal conversation by NSs and NNSs of Hexagonal French, and whether the inventories and their distributions differ for the two groups. In responding to this question, it became clear that present forms were more strongly represented in our corpus than has been reported in previous research, both for NSs and for NNSs. For this reason, we investigated a second research question: How are present forms used to express the function of future-time in informal conversation, and do the NSs and NNSs differ in their use?

THE CURRENT STUDY

Our study is based on a corpus comprised of ten dyadic conversations between a NNS of French and a NS friend, spouse or close acquaintance of the NNS.Footnote 3 This section provides details about the participants and the corpus, as well as information regarding data coding and analysis.

Participants

To constitute the corpus, NNSs of French whose L1 was English were contacted through advertisements, personal networking and a local Anglophone club in the Southwest of France. An initial sample of approximately 20 candidates who had been living in France for at least four years and who had attained a self-described high level of mastery in French was identified. The ten individuals from this initial pool with the highest proficiency levels, as measured by a replication of Birdsong's (Reference Birdsong1992) French grammaticality judgement task (see Donadlson, Reference Donaldson2011, for further details) were retained and deemed to possess proficiency comparable to other near-native populations reported in the literature. All NNSs were university-educated and received their first instruction in French at age 10 or higher (M = 13;0 years); additional details appear in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of the NNSs

Note. AOI = age of first instruction in French; AOE = age of first significant exposure to French; LOR = length of residence at time of data collection. *estimated (exact LOR not provided).

Each NNS participant selected a French NS friend, spouse or close acquaintance with whom they often spoke in French. Details concerning these NSs appear in Table 2.

Table 2. Characteristics of the NSs

Corpus characteristics

The present corpus differs from other corpora used in the previous literature on future-time expression. Rather than conducting a sociolinguistic interview, which generally involves an interviewer unknown to the participant, the researcher played no active role. Instead, each NNS and his or her self-selected NS counterpart were recorded conversing in a casual, informal setting for between 45 and 58 minutes. The resulting 8.3 hour corpus is comprised of 77,300 words (excluding non-lexical backchannels, hesitations, etc.) and is quantitatively balanced between NS and NNS contributions (see Donaldson Reference Donaldson2011). Importantly, no researcher was present during the conversation, and participants were free to discuss whatever they wished. The decision to ask each NNS to select his or her NS interlocutor was made to facilitate the use of an informal register on the part of both speakers, resulting in a speech sample that reflects freely occurring conversation. These corpus characteristics suggest strongly that the data are representative of the speakers’ everyday informal speech.

Data coding

The ten conversations were transcribed by the third author and each was subsequently checked for accuracy by a NS of French with advanced graduate training in linguistics. The data coding procedure involved three phases. To begin, all three authors independently coded the same transcript (conversation NNS1/NS1). In the second phase, the remaining nine transcripts were each coded by one author. Finally, those nine transcripts were recoded by a second author. Thus, each part of the corpus was coded (minimally) by two different researchers. At each phase, disagreements were discussed and resolved among the three authors.

We identified as a future-time context any finite predicate whose realization was clearly set to occur after the moment of speaking (see Blondeau et al., Reference Blondeau, Dion and Ziliak Michel2014: 678, for a similar definition). To identify such contexts, we relied on contextual cues, such as temporal adverbials, discourse context and shared knowledge between the interlocutors. To illustrate our analysis, we will discuss the extract presented in (2). In this extract the participants are discussing a new colleague who will arrive the Thursday after the conversation. We contend that the ten verbs bolded all occur in future-time contexts. In the first example, the future-time adverbial jeudi prochain corroborates the future morphology on viendra, and establishes “next Thursday” as a discourse topic and a future time frame, both of which will be maintained jointly by the two speakers throughout this extract. Despite the absence of future morphology, où on montre les copies can only be interpreted as occurring next Thursday, as reaffirmed by the temporal adverbial le six, which is co-referential with jeudi prochain. Similarly, je serai(s) à Bordeaux refers to NNS10’s plans for next Thursday. Future morphology appears in the fourth context (on verra); this predicate will be realized after the moment of speaking. The next three examples – t'es pas là, ça se termine and y a un déjeuner – all show present-tense morphology, yet all three clearly refer to next Thursday. The continued reference to next Thursday guides the interpretation of the final three bolded examples: the PF in je vais surement pas rester, and the present indicative in c'est aux Chartrons and je suis à la maison. Note, however, that despite the overarching reference to next Thursday, not all finite verbs in this discourse topic make reference to future time: j'ai accepté, for example, can only be interpreted as past-time reference.

-

(2) NS10 (419, 436):Footnote 4 donc elle viendra très probablement jeudi prochain jour le où on montre les copies le jour des résultats le six

-

NNS10 (417): oui alors moi je serai(s) à Bordeaux jusqu’à midi et demie j'ai accepté de remplacer quelqu'un au pied levé pour ah une traduction simultanée

-

NS10 (420, 439): bah écoute on verra hein si t'es pas là t’ es pas là

-

NNS10 (482, 461, 484, 483): mais donc si je pars à . . . Apparemment ça se termine à midi et demie y a un déjeuner mais je vais surement pas rester pour le déjeuner c’ est aux Chartrons je crois donc je suis à la maison ‘fin ici

-

NS10: oui bon enfin

-

NNS10: à trois heures

Given our concept-oriented analysis, a number of finite verbs with future-tense morphology were excluded. First, we excluded contexts involving what Poplack and Turpin (Reference Poplack and Turpin1999) referred to as false futures (e.g. use of PF or IF to make hypothetical statements, refer to spatial movement or refer to habitual actions). Second, our definition of future-time context as occurring after the time of speech excludes references to the future in a past-time discourse setting, such as the series of IF forms seen in (3).

-

(3) NS5 : mais mais ce qui alors je disais à Guy bon pour pour abattre cet arbre et pour le débiter tu n'auras qu’à venir je viendrai(s) je viendrai(s) te chercher et puis y aura qu’à prendre la remorque

Data analysis

We began by identifying all verb forms used in the expression of futurity by the NSs and NNSs, and then compared the two inventories with each other and with previous research (research question 1). For the second research question, we conducted a qualitative analysis into how the NSs and NNSs used the present in order to make reference to future time, focusing on the presence of temporal adverbials and the use of subjunctive forms.

RESULTS

Inventories of verb forms used in future-time expression

A total of 502 future-time contexts were identified in the NNS portion of the corpus, and 445 were found in the NS contributions. An inventory of 13 different verb forms was identified, an example of each appears in (4).Footnote 5

-

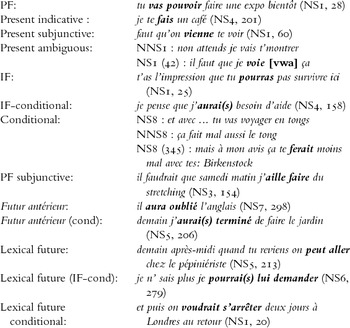

(4)

This inventory reveals a rich picture of verbal resources available in the expression of future time, a picture that goes far beyond the IF, PF and present. Several of the categories necessitate additional comments, as they have not generally been found in previous studies: the distinction among three types of present forms, the IF-conditional forms (IF-conditional, futur antérieur [cond], lexical future [IF-cond]) and the lexical future forms.

Beginning with the present forms, previous studies appear to have restricted their analyses to tokens of the present indicative. Explicitly stated by certain authors (e.g. Nadasdi et al., Reference Nadasdi, Mougeon and Rehner2003; Poplack and Dion, Reference Poplack and Dion2009), others imply this restriction, as the only examples given of the futurate present are presumably indicative ones (e.g. Moses, Reference Moses2002; Roberts, Reference Roberts2012). We say “presumably” indicative, as many subjunctive forms are phonetically non-distinct from indicative ones in oral French, making it impossible to know whether the form in question is indicative or subjunctive, as in (5a) and (5b). In example (5a), the NNS1 is talking about a costume she has made for an upcoming show and wants to show NS1. In (5b), NS7 has just said that she should be able to recuperate an object left with NNS7 and give it to other friends that she intends to see Thursday evening.

-

(5)

-

a. NNS1 : non attends je vais t'montrer

NS1 (42): il faut que je voie ça

-

b. NS7 (340) : parce qu'on les voit jeudi soir

-

Despite the fact that the phonetic realization of voie and voit are identical and that both predicates expressed with voir will occur in the future, we presume that previous studies would have excluded (5a), on the grounds that it was transcribed as a subjunctive form, but included the presumably indicative (5b) in their analysis. In our own future-time contexts, we found unambiguously present indicative forms, unambiguously present subjunctive forms and present forms that are phonetically non-distinct in the subjunctive and indicative moods. Given that mood distinction has been shown to be variable in French (Gudmestad and Edmonds, Reference Gudmestad and Edmonds2015; Poplack, Lealess, and Dion, Reference Poplack, Lealess and Dion2013), we prefer to make no judgement as to the mood marking of the ambiguous forms. For this reason, we coded them separately as present ambiguous.

We faced a similar challenge in our coding of certain first-person singular forms. For many speakers of Hexagonal French, the only difference between the conditional and IF for the first-person singular is an orthographic one: j'aurai (IF) versus j'aurais (conditional). The pronunciation distinction made between these two forms by some speakers opposes the mid-close vowel [e] of the IF to the mid-open vowel [ε] of the conditional; for most speakers, however, both j'aurai and j'aurais are now pronounced with the mid-close variant, especially in casual, unmonitored speech (Gueunier, Genouvrier and Khomsi, Reference Gueunier, Genouvrier and Khomsi1978: 70). It is thus impossible for such tokens to determine whether the speaker used the IF or the conditional. For this reason, we followed Fleury and Branca-Rosoff (Reference Fleury and Branca-Rosoff2010) in creating a separate category for these forms: IF-cond included only instances of the first-person singular in the IF or conditional (a similar category exists for first-person examples of the futur antérieur and lexical future conditionals: futur antérieur [cond] and lexical future [IF-cond]). In our data, we transcribed these forms in the following manner: je serai(s) à Bordeaux (NNS10, 417). Given that most previous research has concentrated on morphological form, it seems likely that a priori (presumably prescriptively informed) decisions about what is an IF form and what is a conditional form were made during the transcription process (much as would be the case for the subjunctive vs. indicative examples given in [5]), and that subsequently extracted IF forms thus reflect prescriptive distinctions.

The final group of forms that we would like to highlight are the three lexical futures (e.g. I want to go to the movies). As a group, lexical futures are periphrastic constructions with agent-oriented modalities. They involve the use of a first verb (generally denoting desire, obligation, ability or attempt) making reference to a present state about a future action (see Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca, Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994). According to Bardovi-Harlig (Reference Bardovi-Harlig, Dekydtspotter, Sprouse and Liljestrand2005: 1), lexical futures are ‘often overtly modal’. In our project, three types of lexical futures were identified: instances where the first verb is conjugated in the present (6a), examples where the first verb is unambiguously in the conditional (6b) and instances of the first-person singular that are phonetically non-distinct between the conditional and the IF (6c).

-

(6)

-

a. lexical future: les chauffeurs routiers doivent travailler (NS5, 212)

-

b. lexical future conditional: est-ce que tu pourrais passer à la bibliothèque (NS10, 406)

-

c. lexical future (IF-cond): lundi comme c'est un jour férié j’ aimerai(s) pouvoir finir cet arbre dans le jardin (NS5, 218)

-

In all three examples, the action – travailler, passer and pouvoir – will happen at a future time, whereas the finite verb expresses a present state about the future action. Lexical futures have not, to the best of our knowledge, been addressed in research on NS French (but Moses, Reference Moses2002, includes them among “other forms” in his investigation of the development of future-time reference in L2 French). Moreover, although they have been investigated in L2 English (Bardovi-Harlig, Reference Bardovi-Harlig, Dekydtspotter, Sprouse and Liljestrand2005) and in L2 Spanish (Kanwit, Reference Kanwit2014), we differ from this previous research in that we identify three lexical future forms (see examples in [6]). In our dataset, lexical futures involve the following verbs: aimer, avoir à, avoir envie, compter, devoir, pouvoir and vouloir.

NS inventory and distribution

NSs produced a total of 13 different verb forms and 111 different lexical verbs in 445 future-time contexts. The 13 verb forms were used by NSs with varying frequencies, as seen in Tables 3a and 3b. Table 3a shows all forms used in more than two percent of total contexts. The PF was the verb form used most frequently in future-time contexts (35.5%), followed by the present forms (indicative, subjunctive and forms that are ambiguous between the two), which together accounted for a full 31.9%. The third most frequent set of forms for the NSs is the IF and IF-cond (18%), whereas lexical futures (present, IF-cond, cond) together account for 12.6%. Finally, as shown in Table 3b, several forms are present in the data, albeit infrequently: lexical future conditionals and IF-conditionals, the futur antérieur, the futur antérieur (cond), conditional forms and the PF in the subjunctive. For these minor forms (i.e. forms that are used in less in 2% of all future-time contexts), it is of note that eight of the ten NSs used at least one such form, suggesting that their use in future-time contexts is not due to the personal preference of a minority of speakers.

Table 3a. NS distribution of major verb forms used in future-time contexts

Table 3b. NS distribution of minor verb forms used in future-time contexts

Presented in this fashion, our data are difficult to compare to previous research, insofar as most work on future-time expression in NS French has been limited to the IF and PF. To provide a point of comparison with the previous studies on native Hexagonal French, we reduced our NS dataset to only the occurrences of the IF and PF and converted the raw scores into percentages. For the sole purposes of comparability with previous studies, we have included all IF and IF-Cond tokens under “IF”. The resultant dataset is small and represents only approximately half of all future-time contexts identified for our speakers (n = 238, as opposed to the full dataset of 445 occurrences). The newly calculated percentages are presented in Figure 1 as Donaldson, along with the data from Roberts (Reference Roberts2012), Fleury and Branca-Rosoff (Reference Fleury and Branca-Rosoff2010), Söll (Reference Söll and Hausmann1983) and Wales (Reference Wales1983).Footnote 6 As can be seen in Figure 1, the PF (relative to the IF) is clearly dominant among our NSs, and slightly more so than has been reported in previous studies of Hexagonal French.

Figure 1. Comparison of PF versus IF in Native Hexagonal French (Oral Production).

NNS inventory and distribution

Turning now to our NNS data, we find that the ten speakers employed 11 verb forms and a total of 127 different lexical verbs in the 502 future-time contexts. The NNS data show exactly the same ranking as the NS data among the four most frequent verb forms (Table 4a), with the PF (39.6%) being used most frequently, followed by the three present forms (29.1%), the two IF forms (15.7%) and finally the three lexical futures (14.3%). As shown in Table 4b, the NNSs also used several minor forms in the expression of future time: lexical future conditionals and IF-conditionals, futur antérieur (cond) and conditionals. A total of eight different NNSs used at least one of these four minor forms in the expression of future time. As opposed to the NSs, no instances of the PF subjunctive or futur antérieur were found for the NNSs.

Table 4a. NNS distribution of major verb forms used in future-time contexts

Table 4b. NNS distribution of minor verb forms used in future-time contexts

To situate our NNS data with respect to findings from previous L2 studies, we calculated percentages of use for the three forms reported on in previous research: PF, present indicativeFootnote 7 and IF. In so doing, our NNS corpus shrinks from 502 to 379 future-time contexts. These percentages are compared to the distribution of forms reported in four previous studies: Blondeau et al.’s (Reference Blondeau, Dion and Ziliak Michel2014: 680) 29 Anglo-Montrealers, Nadasdi et al.’s (Reference Nadasdi, Mougeon and Rehner2003: 205) immersion students in Canada, the six most advanced students from Moses (Reference Moses2002: 138), and all 18 second- and third-year university participants reported on in Howard (Reference Howard2012: 213). As seen in Figure 2, the PF is dominant in the three studies where speakers are using French in a target-language environment: among Anglo-Montrealers, immersion students and our own NNSs. The two studies investigating learners in a university setting both find relatively high levels of IF in their oral interviews (although the number of total tokens for both Howard and Moses is relatively low, 104 and 116, respectively). Finally, the results from the present study stand out insofar as rates of futurate present use are only exceeded by findings from Howard (Reference Howard2012).

Figure 2. Comparison of Distribution of PF, Present, and IF in L2 French (Oral Production).

Use of the present to make reference to future time

The futurate present has been identified as one of the three most frequent verb forms in future-time contexts in several studies of NS and L2 French. Interestingly, these forms account for a much larger portion of our data than reported in previous studies: Whereas Poplack and Turpin (Reference Poplack and Turpin1999) only found the futurate present in 7% of their future-time contexts and Roberts (Reference Roberts2012: 97) justified his decision to exclude the futurate present in his analysis of Hexagonal French in part because of ‘the extremely low token numbers’, these forms make up almost one third of our total corpus. We hypothesize that these strong differences in the percentage of present-for-future forms between our study and previous research may be due to two causes. First, given that our dataset of informal conversations is unique among studies of future-time expression, it is possible that the futurate present is more frequent in spontaneous, informal conversational data (as opposed to the speech elicited in sociolinguistic interviews reported in most previous studies). We leave this point to future research. Second, as already mentioned, most research has defined the futurate present as the co-occurrence of a presumably present indicative form and a future-time temporal adverbial (e.g. Blondeau, Reference Blondeau2006: 74; Le Goffic and Lab, Reference Goffic and Lab2001: 78; Moses, Reference Moses2002: 27). Although such instances are indeed counted among our set of present forms, they are not the majority. If we remove from our dataset all present-for-future forms with no temporal adverbial in the same clause as well as all forms that are clearly or presumably subjunctive, the futurate present would amount to only 13.2% (n = 46) and 10.3 (n = 41) of the NS and NNS corpora, respectively. Although these figures are more in line with previous research, there is no principled reason to restrict present-for-future in such a way within a concept-oriented analysis. One of the notable results of our approach is that it allows us to make the argument for a wider view of present-tense forms used in future-time contexts. We now take a closer look at two aspects of the present-for-future that have received little attention: its use with – but especially without – temporal adverbials and instances of the present subjunctive in future-time contexts.

Although generally claimed that a temporal adverbial is necessary for the present to be able to make reference to future time, it is unclear how “presence of a temporal adverbial” has been interpreted in previous research: Must the adverbial occur in the same clause, the same utterance, the same turn as the verb form? In our coding, we considered an adverbial to accompany a future-time context if it occurred in the same clause, and we indeed find that futurate present forms co-occur more frequently with temporal adverbials when compared to the overall corpus (Table 5). However, the co-occurrence between temporal adverbials and the futurate present is far from categorical, with only 40.8% of all NS present forms co-occurring with a lexical temporal indicator, a figure that drops to 32.4% in the NNS portion of the corpus.

Table 5. Future-Time Contexts that Co-Occur with a Temporal Adverbial

This result can be explained by the fact that temporal reference can be established by means other than an immediate temporal adverbial. It is possible – and, indeed, these are the most frequent examples in our corpus – for future temporal reference to be established elsewhere in the discourse, thus creating a future-time context in which the present can be used without the direct presence of an explicit lexical temporal indicator. Several such examples are provided in the exchange shown in (7). In this passage, the two speakers begin by discussing plans for the following Thursday, as established in NS7’s first turn, before moving on to the topic of weekend plans, introduced by NNS7 in her third turn.

-

(7) NS7 (331, 340): on va peut-être ressayer de le remporter jeudi après-midi parce qu'on les voit jeudi soir

NNS: ah d'accord

NS7 (318, 309, 339): et je pense qu'on pourra pas passer la journée avec nos bagages il faudra qu'on repasse par chez toi le soir

NNS7: ah d'accord

NS7 (299, 300, 301): tu me diras où on peut te laisser les clés ou si on claque la porte ou je sais pas

NNS7 (335): ouais si tu claques la porte bein moi je je ne sais pas encore pour euh mes projets de week-end tout est en train de changer mais euh

NS7: ah oui?

NNS7 (336, 337, 338): ouais parce que je suis fatiguée euh: les autres jours qui XX normalement je descends en Suisse avec un des copains [oui] mais les gens qui j'aime ne descendent pas forcément les gens qui je n'aime pas c'est pas je les aime pas mais c'est que je vais pas pouvoir supporter tu vois les chatches pendant quatre jours donc je ne sais pas

NS7: ça perd de son intérêt

NNS7 (339): oui c'est que en plus je pars en Suède le week-end après

NS7 (302): ah bon tu fais les deux parce que tu m'avais dit un moment Suisse ou Suède

In these 11 turns, we find no fewer than 14 future-time contexts (see bolded verbs), of which eight are expressed using a futurate present. Of these eight, three occurrences are with an immediate temporal adverbial (on les voit jeudi soir, on repasse chez toi le soir and je pars en Suède le week-end après). In the remaining five instances, future temporal reference is established through other means. For the two examples involving the question of simply shutting the door, it is the immediately preceding mention by the NS of picking up of their luggage Thursday evening that allows the hearer to establish future reference. In the next turn, the NNS introduces the topic of her plans for the weekend. The establishment of future-time reference is made here not with a temporal adverbial per se, but with a noun phrase: mes projets de week-end. When the NNS speaks again, she is still on the topic of the coming weekend. Although she does not reiterate the future temporal reference, it is clear that her going to Switzerland is still referring to the weekend in question. Moreover, it should be pointed out that even if je descends en Suisse were the first introduction of the topic, the simple fact that the two people talking are in France – and are not on their way Switzerland – forces the hearer to choose between either a habitual reading (the speaker goes to Switzerland regularly) or a non-present (and, specifically, future) reading of the statement. At the end of this exchange, the NNS redefines the future temporal reference (to speak not about the coming weekend, but the weekend after), to which the NS responds using a futurate present non-accompanied by a temporal adverbial. We thus conclude that although the tendency to use the present to make reference to future time appears to increase in the presence of a temporal adverbial for both NSs and NNSs alike, one must bear in mind that in more than half of all uses of these forms, the present is in fact used in future-time contexts without the immediate presence of a lexical temporal indicator and that this is made possible because future-time reference in these cases has been established by other lexical or discursive-pragmatic means.

The second point that our analysis allows us to address with respect to the futurate present concerns the use of the subjunctive in the expression of future time. We first note that these occurrences are less frequent, appearing in only 4.2% (NNSs) and in 5.4% (NSs) of future-time contexts.Footnote 8 Although infrequent when compared to the other major forms, there is evidence that subjunctive use is actually four to five times higher in future-time contexts than in finite clauses more generally (see O'Connor DiVito, Reference O'Connor DiVito1997: 51, who finds that only 1% of all finite clauses in spoken French contain an unambiguous subjunctive form). Several examples of subjunctive verb forms in future-time contexts are provided in (8) and (9). In (8), the two speakers are discussing the fact that the NNS is going to pick up a friend at 7:45am the following Sunday.

-

(8) NNS5 (225): pour aller à à à la Bastide de Chalos il faut que je parte d'ici à huit heures moins le quart alors?

NS5 (276): bah toi il vaut mieux que tu partes vendredi soir

NNS5: oh t'es pas gentil {laughter}

Whereas the two subjunctive forms in (8) are accompanied by a temporal adverbial, most subjunctives in future-time contexts, including (9a–b), are not. In (9a), the NS asks the NNS to be the godmother of her as yet unborn baby. She adds that if the baby is a girl, she would like the first name of the NNS to be part of the baby's name. These two states – being the godmother and the baby carrying the name of her godmother – cannot already be realized, given that the baby is not yet born. In the NNS example in (9b), the speaker is discussing her efforts to sell her house and then return to the United States. Context makes clear that the house is currently for sale and that the sale will happen in the future.

-

(9)

-

a. mais si tu es d'accord on aimerait bien que tu sois la marraine du bébé {ah} alors deuxième question si c'est une fille j’ voudrai(s) qu'il y ait [NNS's name] dans son nom si ça te dérange pas (NS7, 343, 344)

-

b. voilà. voilà: et euh (1s) et puis voilà donc j'ai envie qu'elle se vende vite pour pouvoir avancer (NNS1, 95)

-

The present subjunctive patterns in a clearly different manner from the other futurate present tokens with respect to temporal adverbials. Whereas NSs and NNSs tend to use both the present indicative and present ambiguous more frequently in the presence of a temporal adverbial, the present subjunctive is not favoured by the presence of a lexical temporal indicator (compare Tables 5 and 6).

Table 6 Uses of futurate present that co-occur with a temporal adverbial

Although we have no definitive explanation for this pattern, we note that both the subjunctive and the future forms (along with the conditional) are used in expressions in the irrealis domain, defined by Poplack (Reference Poplack, Bybee and Hopper2001: 406) as ‘the domain of imagined, projected, predicted or otherwise unreal situations or events’. In other words, it is perhaps no accident that a major exponent of subjunctive modality (i.e. the subjunctive present form) can also be used in future-time contexts without the support of a temporal adverbial (see also Bardovi-Harlig, in press, for mention of the future as a minor device for expressing the subjunctive mood and the subjunctive as a minor device for expressing futurity).

DISCUSSION

The first part of this section is organized around our two research questions: Research question 1 examined the inventory of verb forms used by NSs and NNSs in the expression of future time, whereas research question 2 investigated the use of the present in expressing futurity. In the second part, we address the methodological and theoretical contributions of our analysis to the study of future-time reference in NS French and to the field of L2 acquisition more generally.

Inventory of Verb Forms Used

Research question 1 asked what verb forms are used to express the function of future-time reference by NSs and NNSs of Hexagonal French. Whereas most research into future-time expression in French has reported on the use of the PF and the IF (and the present, for certain studies), our investigation of all finite predicates whose realization was clearly set to occur after the moment of speaking revealed that the number of forms used in the expression of futurity is much larger than previously reported. As discussed in the Results section, this difference is at least in part due to the fact that certain coding decisions in previous research have likely been informed by prescriptive distinctions for those forms that are ambiguous in oral data (i.e. the IF and conditional forms in the first-person singular and many present indicative and subjunctive forms). Finding these decisions questionable, we opted for the coding schema presented in (4), identifying 13 verb forms in the NS corpus and 11 in the NNS corpus. The NSs and NNSs were found to use a similar repertoire of forms, with only two minor forms – the futur antérieur and the PF subjunctive – being used by the NSs and not by the NNSs. Regarding the distribution of these forms (Tables 3a and 3b and Tables 4a and 4b), the NS and NNS portions of our corpus are comparable, with PF and present forms dominating in both parts. Thus, in terms of their make-up, the NS and NNS portions of our corpus are largely similar.

Present forms in the expression of future time

Research question 2 examined how the present was used in making reference to future time in our corpus. In this way, our analysis provides a first empirical analysis of the use of present forms in future-time contexts by NSs and NNSs. Our analysis of the present-for-future confirmed that both the present indicative and the present ambiguous are more frequent in the presence of a temporal adverbial, although the lack of such a temporal marker by no means results in the complete avoidance of such forms. As for the present subjunctive, the distribution of this form does not appear to be connected to the presence of a lexical temporal indicator, a fact that may be linked to its use in the expression of irrealis. What comes out of our analysis is that future-time reference can be signaled in many different ways, and that present forms – which are highly multifunctional – can be used in future-time contexts when such time reference has been established by temporal adverbials, but also when the temporal frame has been established elsewhere in the discourse. Although this sample of NNSs uses the present-for-future in similar ways as the NSs, previous research by Edmonds and Gudmestad (Reference Edmonds and Gudmestad2015) using a written selection task found that the greatest differences between the NSs and four L2 groups concerned the selection of the present for future-time expression. It was concluded that appropriate selection of the present-for-future is acquired late in L2 French; the current study suggests that such acquisition may indeed be possible at very high levels of proficiency.

A final point to be made concerning the use of present forms in the expression of future time is related to the potential role of lexical aspect. In our discussion of the present-for-future, we alluded to the fact that certain predicates (in particular, telic ones) in the present may in fact tend towards a future reading (see our previous discussion of the example je descends en Suisse). Although we did not examine lexical aspect in the current project, much previous research has already established the importance of the relationship between lexical aspect and past-time expression (see Andersen and Shirai, Reference Andersen, Shirai, Ritchie and Bhatia1996). This factor has also received some attention with respect to future-time reference (see Helland, Reference Helland1995, for French, Kanwit, Reference Kanwit2014, for Spanish, Wiberg, Reference Wiberg, Salaberry and Shirai2002, for Italian) and may merit investigation in future research.

Overarching contributions

The present findings contribute to research on future-time expression in French at both the methodological and theoretical levels. In terms of method, we highlighted the fact that what is meant by IF and present varies from one researcher to another. Moreover, most linguists have not specified how they coded for the presence of temporal adverbials. In our study, we have attempted, as far as possible, to illustrate and to justify our own coding choices, arguing that such transparency is essential to refining research within this area. In addition, we hope to have made a convincing argument for the interest of concept-oriented analyses for different aspects of language systems and for different participant populations. This type of analysis constitutes an interesting and perhaps necessary complement to other functional approaches. Within variationism, for example, the Principle of Accountability (Labov, Reference Labov1966: 49) requires that the analyst examine all relevant forms in the system of grammar under study. ‘The idea is that the analyst cannot gain access to how a variant functions in the grammar without considering it in the context of the subsystem of which it is a part. Then each use of the variant under investigation can be reported as a proportion of the total number of relevant constructions, i.e., the total number of times the function (i.e., the same meaning) occurred in the data’ (Tagliamonte, 2012: 10). What is described here by Tagliamonte is precisely what a concept-oriented analysis aims to do. As we have pointed out throughout this article, making reference to future time in French involves much more than the PF and IF. Studies that limit their scope to these forms are unable to truly gain access to how a variant functions in a given subsystem of the grammar (see Aaron, Reference Aaron2010).

Moving now to future-time expression in NS French, we note that this study has contributed to the description of French as it is spoken in France. However, much work remains to be done on Hexagonal French. First and foremost, the corpus analyzed in this study is not sufficiently large in order to be representative of Hexagonal French. It thus remains for future research to determine whether the patterns observed in the present data generalize across a larger dataset that includes a wider range of registers and communicative contexts. In addition, although our sampling procedure was based around a set of NNSs located mostly in the Southwest of France, their self-selected NS interlocutors were not all from this region. At this stage, it is thus impossible to know if future-time reference looks different in different parts of France. The important differences in the expression of futurity from one Canadian French variety to another lead us to suggest that future projects should carefully control for this variable. Nonetheless, we feel that the picture painted in this study allows us to establish a more detailed NS baseline for Hexagonal future-time reference, a benchmark that is particularly important when working within the field of L2 acquisition, as it allows us to make comparisons between L2 speakers at various levels of proficiency and NS use.

This brings us to the contributions made by this study to the field of L2 acquisition, and most notably to the discussion on near-native attainment. Previous research into NNSs of French has demonstrated that they closely approximate NS norms with respect to a variety of characteristics, including the use of formulaic language (Bartning, Forsberg and Hancock, Reference Bartning, Forsberg and Hancock2009), clefts and focus (Donaldson, Reference Donaldson2012), interrogatives (Donaldson, Reference Donaldson2016), among others. However, it has also been demonstrated that NNSs continue to differ from NSs in their use of morphosyntactic structures (see Bartning, Forsberg Lundell and Hancock, Reference Bartning, Forsberg Lundell and Hancock2012). To the best of our knowledge, studies examining how such high achieving L2 users (of any language) fare with variable structures (such as future-time expression) are rare (but see Blondeau et al., Reference Blondeau, Dion and Ziliak Michel2014). Such structures present particular learning challenges, insofar as one must both learn what different forms can be used to express a given meaning, but also how to decide amongst the different possibilities for any given expression of that meaning. In our view, adopting a concept-oriented perspective to investigate the use of variable structures by NNSs is particularly relevant, insofar as such a rich and broad perspective allows us to examine how such speakers use both the most frequent ways of expressing a certain meaning, but also those means that are rarer. In our investigation of the expression of future-time, our concept-oriented approach allowed us to reveal remarkable similarities in the two portions of our corpus for the expression of a variable structure: NSs and NNSs make use of almost exactly the same set of verbal forms and these forms show similar distributions in the two speaker groups.

We interpret this close approximation as a successful application of what Andersen (Reference Andersen, VanPatten and Lee1990) termed the multifunctionality principle. According to Andersen (Reference Andersen1984, Reference Andersen, VanPatten and Lee1990), early L2 acquisition in particular is characterized by the one-to-one principle, namely the mapping of one form to one meaning, a tendency that he hypothesizes is due to processing constraints. For future-time expression, this may take the form of one verb form dominating in the expression of future time, which is precisely what was reported by Bardovi-Harlig (Reference Bardovi-Harlig, Overstreet, Rott, VanPatten and Williams2004) for L2 English (will was the dominant form in early interlanguage). However, Andersen goes on to write that ‘when a learner moves away from a one-to-one representation of form to meaning it is usually in the direction of multifunctionality in existing forms (along with addition of new forms)’ (Reference Andersen, VanPatten and Lee1990: 53). The present results represent the other end of the L2 developmental spectrum, and demonstrate that these NNSs appear to have been successful in developing multiple functions (or meanings) for a form (e.g. with present forms), and multiple forms for the single meaning of future-time reference.

CONCLUSION

Our concept-oriented approach to variable future-time expression among NSs and NNSs of Hexagonal French has provided a broad account of verbal means used in the expression of futurity, contributing to research on future-time expression in NS French and to investigations into near-nativeness in L2 acquisition. In particular, we found that NSs of Hexagonal French drew on an inventory of 13 different verb forms in future-time contexts, and NNSs used 11 different verb forms and that in both portions of our corpus, PF and present-for-future forms accounted for more than 60% of all occurrences, whereas the IF accounted for only between 15.6 and 18%. Finally, our analysis of the present-for-future highlighted its use in contexts in which future-time reference had been established via means other than adverbials. Whereas most research into the expression of temporality has focused on the past, our findings demonstrate the complexity involved in the expression of the future in NS and NNS French. Among other things, future-time reference implicates the larger discourse context, the mood system (e.g., the use of lexical futures and the subjunctive in future-time contexts) and potentially lexical aspect. Concept-oriented approaches, with their broad and multi-level (i.e., lexical, morphological, discursive, pragmatic, etc.) view of the expression of a given concept, are an important tool to arriving at a better understanding of how speakers make reference to future time. They also show great potential to help researchers respond to Bardovi-Harlig's (in press) call to move research from individual form-meaning pairings to a better understanding of the tense-aspect-mood system more generally.