Since its discovery in 2015, several aspects of the tomb of the deposed emperor Liu He 劉賀 (92–59 b.c.e.), identified by his later title Noble of Haihun 海昏侯, have garnered widespread attention. Located outside today's village of Datangping 大塘坪, about thirty kilometers north of the modern city of Nanchang in Jiangxi Province, the “Haihunhou” tomb is a rare discovery, not least because the tomb occupant was a notorious figure in Chinese history. After the death of Emperor Zhao 昭 (94–74 b.c.e., r. 87–74),Footnote 1 Liu He, then King of Changyi 昌邑, was raised to the position of Son of Heaven in 74 by the court's power broker Huo Guang 霍光 (d. 68). Liu He held this position for only twenty-seven days before being accused of a litany of ritual breaches and exiled from the capital of Chang'an.Footnote 2 Apparently, his tomb and its contents remained untouched from Liu He's death and burial in 59 until their discovery in 2015.

The richness of the contents of Liu He's tomb will no doubt have a major impact on the study of early Chinese literature, art, and intellectual history. This article will look at one object in the tomb that combines text and image in a unique way—a lacquerware screen and mirror stand that contains both images and capsule biographies of Kongzi and his disciples—in three parts. First, it introduces the tomb as context for the images and texts on the screen and mirror stand. Then it compares specific parallels with Shi ji 史記 (Records of the Archivist) chapters to discuss patterns of circulation of Kongzi and disciple narratives and dialogs and how they were combined to form biographies in the Han. Finally, it contextualizes these texts within broader patterns involving Han cultural representations of Kongzi and the disciples.

A first wave of publications showed that Liu He's cavernous tomb was filled with more than ten thousand gold, bronze, lacquer, and iron items, not to mention small hills of wuzhu coins weighing over ten metric tons, and was located next to a carriage pit and set inside of an expansive family sacrificial complex. Images in the popular media of gold ingots and ornaments circulated widely, followed by the opening of an exhibition at the Jiangxi Provincial Museum, and a CCTV documentary.Footnote 3 While scholars await the publication of over five thousand bamboo slips that were excavated from the site, an image of one of these slips bearing a short passage on one side and the title “Zhi dao” 智道 on the reverse side was published in 2016.Footnote 4 The two-character phrase matches the title of a text that was part of a Han version of the Lun yu 論語, labelled with the regional marker “Qi” 齊 in the Han shu 漢書.Footnote 5 Several subsequent articles have debated the identification of that and other Lun yu–related slips with that particular version of the Lun yu.Footnote 6

Two groups of articles published in 2020 have begun to fill in more details about the texts excavated from tomb M1. One group, published in Wenwu, features articles treating different genera of bamboo slip text in preliminary essays.Footnote 7 The second, a book-length study in twenty chapters edited by the noted epigrapher Zhu Fenghan 朱鳳瀚 entitled Haihun jiandu chulun 海昏簡牘初論, provides a general introduction to the tomb and its contents, a preliminary discussion of the bamboo slip texts, and a final section devoted to the inscribed wooden boards and the inscribed screen and mirror stand.Footnote 8 Detailed analysis of the bamboo-slip texts from the Haihunhou tomb must await the publication of a complete set of photographs, but a growing number of reproductions have been published. For example, Haihun jiandu chulun includes a photograph of a slip with the verso note “from [chapter] 21 ‘Zhidao’” (qi Zhidao nianyi 起智道廿一) that identifies the slips as excerpted from the text that, we saw above, circulated as part of one Han Lun yu recension.Footnote 9

The Haihunhou Screen and Mirror Stand

A tomb artifact for which a complete text transcription and substantial number of photographs have now been published is the inscribed lacquerware screen and mirror stand that was initially identified as the “Kongzi dressing mirror” (Kongzi yijing 孔子衣鏡). Its depiction of a man wearing white robes was widely publicized when it was first found, and sometimes described as the earliest extant depiction of Kongzi. Selected images of the artifact have been published in many venues, and an initial transcription of its manuscript texts, first published in 2016, was revised and published alongside detailed photographs in the 2020 Haihun jiandu chulun.Footnote 10 The artifact had pride of place in the main chamber of Liu He's tomb, which was divided into two sections by wooden partitions. Liu He's coffin rested in the eastern part of the main chamber accompanied by bronze ritual vessels, while the artifact shared the western part of the main chamber with lacquer and gold objects.

Visually, the artifact is a stunning example of early Chinese decorative arts, a two-sided lacquerware screen and frame combining texts and images, which had once been attached to a rectangular bronze mirror measuring 70.3 × 46.5 cm and 1.3 cm thick. During the excavation, two rectangular objects were catalogued that scholars now believe were part of this artifact. One side of a rectangular object identified as M1:1415 contained images associated with longevity on all four sides of the mirror.Footnote 11 The other side contained annotated images of Kongzi and five of his disciples, with the inscribed names Yan Hui 顏回, Zigong 子贛 (i.e., Zigong 子貢), Zilu 子路, Tangtai Ziyu 堂駘子羽 (i.e., Tantai Mieming 澹臺滅明), and Zixia 子夏.Footnote 12 A smaller, more damaged, rectangular object identified as M1:1582 has, arguably, similarly contrasting themes on its two sides. One side contains an image of the legendary Zhong Ziqi 鍾子期 listening (probably to the performance of a lost Boya 伯牙) under a rhapsody specially composed for placement on the object. The rhapsody extols the quality of the mirror and describes the salutary effect of its images.Footnote 13 The other side of the second object is devoted to two other disciples, with annotated images of Zizhang 子張 on the left and a mostly lost Zengzi 曾子 on the right.Footnote 14

While initial scholarship attempted to reconstruct these wooden objects as a larger dressing mirror stand frame with a smaller mirror cover, more recently Wang Chuning 王楚甯 has argued that the two rectangular objects were originally arranged at a right angle on separate pedestals, screening the corner of a couch or bed. Wang argues that Kongzi, the seven disciples, and their biographies faced inward, while the mirror, surrounded by the embodiments of longevity, joined with Zhong Ziqi and the rhapsody, faced outward. This might suggest a division of the room into two spaces, one where the ruler might gain from auspicious images, and one where he might gain from Kongzi, his circle, and their biographies.Footnote 15

Han Biographies of Kongzi and His Circle

The discovery of the screen and mirror stand provides important information about a moment in the Western Han when Kongzi and his disciples were becoming increasingly important. Elsewhere, I have talked about the “disciple vogue” of the first century b.c.e., and the placement of these images and biographies at the center of the former emperor's tomb is consistent with this trend.Footnote 16 Yet applying the term “biography” perhaps assumes too much about the function of the texts inscribed on the object, based on their close relationship to similar materials in the Han histories.

The two chapters devoted to Kongzi and his disciples in Sima Qian's 司馬遷 (145–c. 87) Shi ji have been, until now, the foundational sources for early biographies of the master and his circle. The “Hereditary House of Kongzi” (“Kongzi shijia” 孔子世家) offers a chronological treatment of Kongzi's life, connecting him to important ancestors when describing his birth and youth, recounting his words and deeds during his adult travel from court to court, followed by eulogies of him and brief descriptions of two aspects of his postmortem legacy: his shrine and his posthumous reputation reflecting his descendants’ accomplishments. Another chapter, “Zhongni's [i.e., Kongzi's] Disciples” (“Zhongni dizi liezhuan” 仲尼弟子列傳), identifies the seventy-two direct disciples Kongzi trained in ritual practice and study of the Classics, assigning the first ten of them to one of four categories: “virtuous conduct” (dexing 德行), “government service” (zhengshi 政事), “oral rhetoric” (yanyu 言語), or “literary scholarship” (wenxue 文學).Footnote 17 A greater proportion of the disciple chapter's content overlaps with the content of the Analects, but the Shi ji disciple chapter and the Analects differ formally in that the Shi ji chapter arranges conversations by the identity of Kongzi's interlocutor, while the Analects only rarely groups such passages in that way.Footnote 18

Likely a sampling of a wide array of Kongzi-related works in circulation in mid-Western Han, these two Shi ji chapters not only preserve materials concerning the sage and his community not found in the Analects, but also reflect a construction of a particular image of Kongzi and his community, colored, perhaps, by Sima Qian's own justification for writing his history, which has been characterized as becoming “a second Confucius.”Footnote 19 Whatever Sima Qian's intent, later readers across a number of social groups took the lives of the members of Kongzi's community as paradigms of exemplary conduct, and the composition of the Chunqiu 春秋 as the prototype for later writers who wished to transmit their political and philosophical views to posterity.

The texts on the Haihunhou tomb's screen and mirror frame, which I will call the “mirror texts” for the sake of simplicity, were likely composed in the decades following the compilation of Sima Qian's masterwork. The mirror text biography of Kongzi differs from the those of his disciples in significant ways. For example, it is both longer and relies on chronologically arranged narratives rather than incorporating dialogues. In many ways, these formal distinctions mimic the bifurcation found in the two Shi ji chapters: one is a chronological biographical treatment of Kongzi followed by a short eulogy, while the second consists of brief biographical sketches and snatches of dialogue associated with several prominent disciples. Like the Shi ji chapter devoted to Kongzi, the Haihunhou Kongzi biography mentions key elements of Kongzi's life, including his childhood mastery of ritual, his teachings, and his editorial work on the Classics, presented in the same order as in the longer Shi ji chapter. The Haihunhou text's eulogy even represents a direct parallel to part of the Shi ji postface, minus any attribution to the “Senior Archivist” 太史公. While significant differences in content between the two texts will be discussed in more detail below, these similarities are largely compatible with a hypothesis that the mirror's biography of Kongzi may be an abridgement of some version of the material known from the “Hereditary House of Kongzi” that drew material either from other sections of the Shi ji or from some of the same texts consulted by its compiler.

Like the Shi ji disciples’ chapter, the Haihunhou narratives for the disciples evince slight interest in the disciples’ backstories prior to their inductions into Kongzi's circle and focus instead on Analects-style dialogues between Kongzi and his disciples. As we will see, the mirror disciple texts differ from the treatments provided for these same disciples in the Shi ji in one significant way, despite the highly formulaic framing of each biography: the two texts differ in the selection of narratives and dialogues associated with each disciple. As a result, the mirror disciple texts do not simply represent excerpts of the longer treatments from the Shi ji “disciples” chapter.

The complex relationship between the excavated mirror texts and the two transmitted chapters of the Shi ji is the subject of the next two sections of this article, but these are by no means the only two texts concerned with Kongzi and his circle. Two chapters from the Eastern Han compilation Kongzi jiayu 孔子家語, entitled “Dizi xing” 弟子行 and “Qishi'er dizi jie” 七十二弟子解, contain some material that overlaps with the mirror texts and the Shi ji chapters. The Han shu catalog lists a Kongzi turen tufa 孔子徒人圖法, which likely also concerned the categorization and description of the disciples.Footnote 20 Rather than treating the textual record concerning the early Kongzi community as congeries of exemplary behaviors, in these texts their assembly was in itself authoritative. They rearranged earlier information to shed light on a particular typology or on the relationships between members of that set. The focus was not on the sage alone, but on the sage and the disciples together. The following sections examine these biographies, and then propose some tentative explanations for why this was the case.

The Haihunhou Biography of Kongzi

To the left of Kongzi's image, the thirteen-line text summarizing Kongzi's life contains significant parallels to the earliest biography of the sage in the Shi ji. While the Shi ji “Hereditary House of Kongzi” is certainly a more comprehensive treatment of Kongzi's life story, three passages in the mirror text contain extended parallels with the Shi ji biography. The first set of parallels corresponds to the initial segment of the Shi ji chapter, detailing Kongzi's ancestors, birth, youth, and early career; the second set, to a Shi ji passage covering a late stage of Kongzi's life, from age sixty-three through his final years; and the third set, to the final textual block in the Shi ji biography, the Postface by the Senior Archivist (shortened in the Haihunhou text). Compared with the Shi ji, the mirror text lacks episodes from the middle of Kongzi's life: his travels to the states of Qi and Zhou, his attainment of office, his stays at the courts of Wei, Chen, Zheng, Cai, and then his return to Lu. Also missing are any final statements about Kongzi's death, eulogies by Lord Ai of Lu and the disciple Zigong, an account of the burial and the shrine that grew up around the grave, and a summary of Kongzi's noteworthy descendants.

Below is the transcription of the mirror text's treatment of Kongzi, translated in four sections, followed by a discussion of key contrasts with the Shi ji text.

1. Kongzi's Family, Birth, and Childhood

1•孔子生魯昌平縣棸邑。其先宋人也Footnote 21 曰房叔。房叔生伯夏, 伯夏生叔梁紇。紇與顏氏女㙒居而生孔子。疇於尼丘。2魯襄公廿二年孔子生。生而首上汙頂。故名丘云。字中尼。姓孔子氏。孔子為兒僖戲。常陳柤豆。設 3容禮。人皆偉之。Footnote 22

• Kongzi was born in the settlement of Zou 棸 in the district of Changping 昌平, in Lu. An ancestor named Fangshu 房叔 [had come from Song], and had a son named Boxia 伯夏. Boxia had a son named Shuliang He 叔梁紇, who dwelt in the wilderness with a daughter of the Yan 顏 clan, and it was she who gave birth to Kongzi. They cultivated fields on Ni Hill 尼丘. In the twenty-second year of Lord Xiang of Lu [551], Kongzi was born. Because he was born with a depression on the top of his head, he was called by the personal name of “Qiu” [meaning “hill”]. His courtesy name was “Second-son Ni,” and he carried the Kong master's clan name.

As a child, Kongzi took delight, when playing, in setting out the sacrificial vessels in a ritually correct . . . [fashion]. Everyone thought him . . . [extraordinary].

The opening section contains many parallels to the beginning of the Shi ji chapter, but some of the minor variations suggest a different understanding of Kongzi's family background. Where the Shi ji somewhat notoriously says, “Shuliang He had a tryst in the wilderness with a daughter of the Yan 顏 clan, and she gave birth to Kongzi,” and “they prayed at Ni Hill and were granted [the child] Kongzi,” the Haihunhou version reads zhu 居 rather than he 合, and chou 疇 rather than dao 禱.Footnote 23 The interpretation of ye he 野合 has long been the subject of acrimonious debate, with some commentaries explaining defensively that their joining was “wild” because of the age difference between Shuliang He and the Yan girl, making a formal marriage ritually incorrect.Footnote 24 Since the Haihunhou text instead says they “dwelt in the wilds,” there has been rejoicing in some quarters because now “we can put an end to this malicious slander about Confucius’ birth.”Footnote 25 The character chou may well be meant to be read as dao (prayer), but here I have read it as “cultivated a field” based on the Shuowen jiezi 說文解字 explanation for chou as “cultivated farmland” (耕治之田也). Kongzi's connection to Ni Hill is considerably simpler than in other Han narratives.Footnote 26

While both the Shi ji and the mirror text refer to the child Kongzi's elaborate ritual play, the Shi ji version embeds it in a longer set of narratives about the burials of his father and mother. In the Shi ji telling, Kongzi's status as a ritual prodigy follows his mother's refusal to tell him where his father was buried.Footnote 27 In the mirror text, Kongzi's parents’ burials present no special challenges worth noting. Essentially, the two texts differ where the mirror text omits elements found in the Shi ji account.

2. Kongzi's Early Career

孔子年十七, 諸侯□稱其賢也。魯昭公六年,孔子蓋卅矣。孔子長九尺有六寸,人 4皆謂之長人異之。孔子行禮樂仁義□久。天下聞其聖。自遠方多來學焉。孔子弟子顏回子贛之徒七十有七人。5皆異能之士。 孔子游諸侯毋所遇。困于陳蔡之間。Footnote 28

When Kongzi was seventeen, the various lords . . . praised his worthiness.

In the sixth year of the reign of Lord Zhao of Lu [536], Kongzi reached the age of thirty. Kongzi's height was nine chi and six cun, and people referred to him as “that tall guy” and thought him on that basis exceptional.

Kongzi practiced the rites and music, benevolence, and righteousness . . . for a long time. The people of the world heard about his sagacity and came from far and wide to learn from him. Kongzi's disciples, and the followers of Yan Hui and Zigong numbered seventy-seven; all were shi 士 [i.e., men of breeding] with exceptional abilities.

[Kongzi journeyed] to the courts of the various lords, but none recognized him. He suffered hardship between [Chen and Cai].

This outline of Kongzi's early career contains so many elements familiar from the Shi ji account that it is easy to miss a key contrast: there are no references to Kongzi holding any office whatsoever. By contrast, the Shi ji account of this period of his life seems to link Kongzi's social origins to his incipient career, forming a portrait of an official whose demonstrated effectiveness leads to the greater responsibilities of higher office:

孔子貧且賤。及長,嘗為季氏史,料量平;嘗為司職吏而畜蕃息。由是為司空。

Kongzi was poor and he lacked official rank. When he grew up, he once served as scribe for the Ji clan, and he measured grains fairly. He once served as official in charge of the pastures, and the domestic animals multiplied. As a result, he was made Commissioner of Public Works.Footnote 29

Notably, the Haihunhou version contains no reference to Kongzi's initial career or to his noble descent from displaced Shang ancestors forced to move to Song, one of whom showed proper humility in the context of repeated official promotions,Footnote 30 a point emphasized in the Shi ji. The effect of both of these omissions is that neither the Haihunhou Kongzi nor his ancestors are ever portrayed explicitly as officials.

The treatments regarding Kongzi's training of disciples also exhibit a telling difference. The mirror text biography puts Yan Hui and Zigong alongside Kongzi in the context of his training of disciples. Recall that on the mirror frame, Yan Hui is visually placed on a par with Kongzi. The Shi ji itself is inconsistent in its references to the number of disciples. The “Hereditary House of Kongzi” counts seventy-two,Footnote 31 but the Shi ji disciples chapter uses seventy-seven instead, describing them, as does the mirror text, as “shi of exceptional abilities.”Footnote 32 It is far from clear whether the number seventy-seven was intended to include Zigong and Yan Hui, but it seems notable that the mirror text elevates particular disciples (conventionally construed as his two “teaching assistants”) to share the limelight with the sage, as do its visual complements.

3. Kongzi's Legacy

魯哀公六年,孔子六十三。當此之時,周室烕,王道壞,禮樂廢,6盛德衰。上毋天子,下毋方伯。臣詑君,子□必,四面起矣。強者為右,南夷與北夷交,中國不絕弟縷耳。Footnote 33

In the sixth year of Lord Ai of Lu [489]. Kongzi was sixty-three sui.

At that time, the Zhou ruling house had been extinguished, its Kingly Way was destroyed, its rites and music discarded, and its flourishing virtue in decline. Above there was no Son of Heaven, and below there were no great loyal officials. Ministers cheating rulers, and sons . . . [fathers],Footnote 34—such conduct arose everywhere. Warlords became confederates; the Southern Yi and the Northern Yi became allies, and the Central States were basically hanging by a thread.

孔子 7退,監於史記,說上丗之成敗,古今之□□。始於隱公,終於哀公,列十二公事,是非二百卌年之中,弒君8卅一,亡國五十二,刺幾得失,以為天下儀表。子曰:吾慾載之空言,不如見行事,深切著明也。故作春秋。Footnote 35

Kongzi retired and surveyed the historical records to explain the [political] successes and failures in previous generations . . . past and present. Beginning with Lord Yin and ending with Lord Ai, he laid out events under the twelve lords of Lu, approving or condemning [the various historical actors] over their 240 years, for their thirty-one [regicides] and fifty-two instances of domains destroyed. He needled [the powerful for their] successes and failures, to make [an exemplary model] for the people of the realm. The Master said, “If I desire to convey my abstract views, nothing is as good as demonstrating them through the conduct of events, rendering them deeply felt and clearly shown.” Thus, he made the Spring and Autumn classic.

上 9明三王之道,下辯人事經紀 決嫌疑□□惡。舉賢才,廢不宵。賞有功,誅桀暴。長善苴惡以備王 10 道。論必稱師而不敢專己。追跡三代之禮,序書傳。上紀唐虞之際,下至秦繆,綸次其事,約其文辭。11 詩書禮樂,雅頌之音,自此可得而述也。以成六藝。Footnote 36

Above, he clarified above the Way of Three Kings, and below he distinguished proper guidelines for human affairs. With it [his chronicle], one may [resolve doubtful points and] . . . wrongdoing, promote the worthy and dismiss the unfit, reward the meritorious and execute the violent, encourage good actions and root out the bad, and, in doing so, complete the Kingly Way. In his judgments, Kongzi always praised his models, never daring to monopolize credit for himself. So he pursued the traces of the Three Dynasties rituals and put in order the old manuscripts and traditions. He arranged the records from the time of Tang-Yao and Yu-Shun all the way down to Lord Mu of Qin, analyzing and putting events in their proper sequence, while abridging their words and phrases. It was from this time forward that the Odes, Documents, ritual and music, and the notes of the “Elegantiae” and “Hymns” were passed down. This brought the “Six Arts” into full existence.

This passage, devoted to Kongzi's writings as record of his political vision and ethical ambitions, is notable for how it gives the writer of history agency in the righting of wrongs and in doing so makes a moving case that literature is capable of administering justice. Conspicuously absent are the descriptions of his numerous encounters with the rulers of his day, as found in the Shi ji biography. In their stead, the mirror text biography highlights his transmission of the rites and music inherited from earlier ages, and his editorial labors on the Classics—directly describing his work on the Odes, Documents, and, most centrally, his compilation of the Spring and Autumn chronicle. Whereas the Shi ji “Hereditary House of Kongzi” includes the Changes among its list of the Classics, and even has a separate passage discussing Kongzi's study of it near the end of his life, the Changes is noticeably absent from the discussion of Kongzi's literary work in the mirror text.Footnote 37

The long discussion of the Spring and Autumn classic is set within a narrative of Zhou decline and has parallels not just to the Shi ji “Hereditary House” but also to a discussion of the Spring and Autumn recorded in the final Shi ji chapter often called the “Personal Narrative of the Senior Director of the Archives” (Taishi Gong zixu 太史公自序). In a dialogue between Hu Sui 壺遂 and a Taishi Gong (probably Sima Qian), we read:Footnote 38

「余聞董生曰:『周道衰廢,孔子為魯司寇,諸侯害之,大夫壅之。孔子知言之不用,道之不行也,是非二百四十二年之中,以為天下儀表,貶天子,退諸侯,討大夫,以達王事而已矣。』 子曰:『我欲載之空言,不如見之於行事之深切著明也。』夫春秋,上明三王之道,下辨人事之紀,別嫌疑,明是非,定猶豫,善善惡惡,賢賢賤不肖,存亡國,繼絕世,補敝起廢,王道之大者也。撥亂世反之正,莫近於春秋。春秋文成數萬,其指數千。萬物之散聚皆在春秋。春秋之中,弒君三十六,亡國五十二,諸侯奔走不得保其社稷者不可勝數。

[i.]I have heard Master Dong say, “When the Way of the Zhou declined and was lost, Kongzi was serving as Director of Brigands, but local lords slandered him, and high officials obstructed his career. Knowing his words would be ignored and his way would not be implemented, Kongzi used his approval or disapproval of events spanning 242 years as an exemplary model for the people of the realm. He censured Sons of Heaven, demoted Lords, and condemned high officials, for no reason other than to fully realize the affairs of the true king.”

[ii.] As the Master said, “If I wished to set forth my views in the abstract, it would not be as good as clearly illustrating through the conduct of events, rendering them deeply felt and clearly shown.” So the Spring and Autumn clarified for rulers the Way of Three Kings and discriminated for subjects guidelines for human affairs. With it, one may resolve suspicions and vacillation, set right apart from wrong, make the hesitant firm, treat the good as good and the bad as bad, acknowledge the worthy as worthy and the unworthy as base, preserve lost domains and continue lines that have ended, remedy the depleted and rescue the perished, and, in doing so, perfectly illustrate the greatness of the Kingly Way.

[iii.] To dispel the chaos of generations and return the society to rectitude, nothing is as good as the Spring and Autumn classic. The text of the Spring and Autumn consists of several tens of thousands of words, and it has several thousand instances of censure, yet the gathering and dispersal of the myriad things is contained in the Spring and Autumn. The Spring and Autumn records thirty-six regicides and fifty-two domains destroyed. As for the Lords who fled and could not protect their altars of the soil and grain, their number is too high to count.Footnote 39

The final chapter of the Shi ji contains multiple speakers, and I have cited this passage in extenso to highlight the way that elements of each of the voices are combined without attribution in the Haihunhou biography. This passage contains three sections parallel to this part of the Haihunhou biography: (i) a long quotation usually attributed to Dong Zhongshu 董仲舒 about the decline of the Zhou rule as a motive impelling Kongzi to write the Spring and Autumn, (ii) a quotation ascribed to Kongzi about the benefits of the writing of history and an expansion of that quotation that highlights the capacity of the brush to overcome the sword, and (iii) a third section with the latter-day description by the Senior Director of the Archives of the miraculous effects the Spring and Autumn can achieve. Although sections (ii) and (iii) are separated in the Shi ji by a passage about the Changes (perhaps interpolated), the fact that these three sections appear in the same order in both texts strongly suggests an intertextual connection between the Hu Sui conversation in the last chapter of the Shi ji and the mirror text biography. If the latter is based on the Shi ji, it draws from more than one chapter of that compilation.

Other aspects of this section of the Haihunhou biography have parallels in other Han sources. For example, the Haihunhou tallies of key phenomena in the Spring and Autumn also appear in the earlier Huainanzi 淮南子, which reads, “The Spring and Autumn covers two 242 years, with fifty-two cases of domains destroyed and thirty-six regicides. It selects the good actions and expunges the bad, in order to complete the Kingly Way.”Footnote 40 Two different parts of the above translation of the Haihunhou account of this part of Kongzi's life end on a parallel with a part of this Huainanzi passage. For the transmitted Han texts, we should consider Wang Gang's 王剛 observation that the mirror narrative indicates that the Zhou line has been entirely extinguished (superseded by the Qin and Han empires), as opposed to simply entering into a period of decline, as indicated in other sources.Footnote 41 Parallels from the first half of the first century show that this part of the Haihunhou treatment of Kongzi is not simply an abridgment of the Shi ji “Hereditary House.”

Kongzi's Death and Eulogy

孔子年七十三,魯哀公十六年四月己丑卒。 天下君王 12至於賢人眾矣,當時則榮,歾則已焉。 孔子布衣,傳十餘世,至于今不絕,學者宗之。 自王侯,中國 13言六藝者折中於夫子,可胃至聖矣!Footnote 42

Kongzi lived for seventy-three years, dying in the fourth month of Year 16 of Lord Ai of Lu [479], on the jijiu day of the sexagenary cycle. There have been many past lords and kings on down to worthies in the realm. They were glorified in their own eras, but once they died, their reputations were finished. Kongzi was a commoner, in plain dress, and yet his way has been transmitted over ten generations down to the present, without interruption, and he has been the founder figure for scholars. From kings and nobles on down, he is the one that those who speak of the Six Arts in the central states all acknowledge, and so he may be called the ultimate sage!

While the Shi ji contains further content following the sentence about Kongzi's late years, the final part of the mirror biography is almost an exact parallel to the final section of “Hereditary House of Kongzi,” aside from the Haihunhou omission of two eulogies, information on Kongzi's descendants, and the first part of the Postface comment attributed to the Taishi Gong. Only the second part of the Taishi Gong comment, about Kongzi's glorious reputation continuing after more than ten generations, is shared as the final word in both the “Hereditary House” Shi ji chapter and the Haihunhou text, in nearly identical prose.

The two texts summarized here—the transmitted Shi ji “Hereditary House” biography submitted to the throne some four decades before the excavated Haihunhou text dating to 59 b.c.e. or before—share so many key passages that there must be a fairly direct connection between the two. Yet, the third of the Haihunhou text's four sections about the Spring and Autumn clearly has parallels with other parts of the Shi ji and, equally importantly, with other second-century b.c.e. texts, demonstrating that the Haihunhou text is not simply excerpted from the transmitted version of the “Hereditary House of Kongzi,” contra some initial assessments. But what is the relationship between the two, then?

There are several plausible hypotheses. First, it is worth considering whether the mirror was made in Chang'an, since the Han shu explains that the Shi ji was not widely disseminated and likely would have been hard to access during Liu He's exile. The work was not circulated until the reign that followed Liu He's exile from Chang'an, we are told:

遷既死後,其書稍出。宣帝時,遷外孫平通侯楊惲祖述其書,遂宣布焉。

After Sima Qian's death, his writings were not well disseminated. During the reign of Emperor Xuan (74–48 b.c.e.), [Sima] Qian's daughter's son Yang Yun, Noble of Pingtong, sought to follow his grandfather's precedents and widely disseminate Qian's book.Footnote 43

Notably, the Haihunhou text includes two extensive quotations that are explicitly attributed in the Shi ji to Taishi Gong. When these passages appear in the Haihunhou biographical treatment they are unattributed, perhaps indicating they derive from materials held in the palace archives available in Chang'an prior to the completion of the Shi ji. Finally, if the mirror was made in 74 b.c.e. or before in the capital, it is the sort of luxury item consistent with the use of state resources for personal ends of which Liu He was accused when he was deposed in that same year.

大行在前殿,發樂府樂器,引內昌邑樂人,擊鼓歌吹作俳倡。會下還,上前殿,擊鐘磬,召內泰壹宗廟樂人輦道牟首,鼓吹歌舞,悉奏眾樂。

When the coffin of the prior emperor was in the front hall, [Liu He] ordered musical instruments be brought from the Music Bureau and musicians brought up from Changyi to play drums and sing songs. After the assembly was over, he ascended the front hall. The bells and chime stones were struck and musicians from the Shrine of Grand Unity were summoned to the inner precincts via the dedicated imperial road to Lake Moushou. There they struck, blew, sang, and danced, performing all kinds of music for him.Footnote 44

In such an atmosphere, it is not hard to imagine a member of another bureau being commissioned to collaborate with craftsmen to create an object like the mirror for the new emperor.

Second, we can say with confidence that the Haihunhou prose biography of Kongzi reflects several clear editorial decisions relative to the content of the corpus of Kongzi stories in circulation at the time. As we have seen, the mirror text's Kongzi is missing certain aspects that are present in other Han portrayals like service in various official capacities. Significantly, relative to the many Han images of Kongzi in circulation, the cultural attainments of Kongzi as preserver of the Classics, as well as rites and music practices, are foregrounded, while Kongzi the political advisor is completely absent. In particular, the Haihunhou narrative highlights his political vision in the Spring and Autumn and elaborates on how others may use that text to access Kongzi's “Kingly Way.”Footnote 45

Thirdly, while the Haihunhou text omits mention of the many dialogues reported between Kongzi and the rulers of his day, it emphasizes his teaching of disciples. In addition, his disciples are placed on a level with Kongzi visually, while the disciples Yan Hui and Zixia are singled out in the accompanying rhapsody, and Yan Hui and Zigong are singled out in the description of Kongzi's teaching of disciples in the biography. While the Kongzi biography may largely be an abridgement of Shi ji materials, the process reflected specific editorial choices. Now we turn to shorter texts that accompany the images of the disciples, texts with major formal differences from the Kongzi biography.

The Haihunhou Disciple Biographies

The connections between the Shi ji chapter containing disciple biographies and the mirror text disciple biographies are extremely interesting. To introduce these biographies, here is a complete translation of the text to the right to Yan Hui's image (with line numbers added):

1 • 孔子弟子曰: 顏回魯人。字子淵。少孔子卅歲 。顏回問仁。子曰:克己 2復禮為仁。一日克己復禮,天下歸仁焉。為仁由己,而 3 由人乎哉。顏淵曰:請問其目。子曰 :非禮勿視,非禮勿 4聽,非禮勿言,非禮勿動 。顏淵曰:回雖不敏也,請事 5此語也。顏回渭然歎之曰:仰之彌高,攢之彌堅,瞻之 6在前,忽焉在後。夫子循循然善誘人,博我以文,約我 7以禮。欲罷不能,既竭吾才,如有所立卓爾 。雖欲從 8之,無由也已。孔子曰:顏回為淳仁直。子謂 9顏回曰:用之則行,舍之則藏,唯我與爾有是夫。孔子 10曰:自我得回也,門人日益親。11 • 右顏淵Footnote 46

Kongzi's Disciples Footnote 47 says:

Yan [Hui was from Lu]. His cognomen was Ziyuan. He was thirty sui younger than Kongzi.Footnote 48

Yan Hui asked about benevolence. The Master said,

“Overcoming oneself and returning to ritual is how to be benevolent. If for a single day one can [overcome oneself] and return to ritual propriety, then the people of the world will return to benevolence. Being benevolent comes from oneself, how could it come from others?”

Yan Yuan: “May I ask about the program?”

The Master said, “Do not look at what goes against ritual, do not listen to what goes against ritual, do not speak of what goes against ritual, and do not do anything that goes against ritual.”

Yan Yuan said: “Though I, Hui, am not clever, allow me to put these phrases into practice.”Footnote 49

Yan Hui heaved [a sigh] and said,

“I look up at it, and it rises further. I bore into it, and it grows harder. I see it in front of me, and suddenly it is behind me. In an orderly manner, my master excels at drawing people in, he broadens me with literature, and then reins me in with ritual. If I wanted to stop, I don't know how to go about doing so.”Footnote 50

Kongzi said, “Yan Hui is pure in his benevolence and [uprightness].”Footnote 51

The Master told Yan Hui, “To work when employed but hide oneself when cast aside, only you and I can do this.”Footnote 52

Kongzi said, “Since I got hold of Hui, my followers have grown closer each day.”Footnote 53

• On the right is Yan Yuan.

This biography begins with information about Yan Hui's name and age relative to Kongzi. It then proceeds to three sections having to do with Kongzi, treating the training of Yan Hui in Kongzi's ritual program and Yan Hui's struggles to internalize it. In what is perhaps the most significant line, Kongzi tells Yan Hui, “Only you and I can do this,” a literary echo of the placement of the two figures on the top register. What is it only they can do? The line “work when employed but hide oneself when cast aside” seems particularly significant for a former emperor in remote exile, although it is possible that the screen and mirror stand predates that event.

Yan Hui's mirror text portrayal is in some ways similar to the Shi ji section on Yan Hui. Yet there are also meaningful differences: the former does not include several Shi ji passages (parallel to Analects 6.11, 2.9, and 6.3) found in the Shi ji disciples chapter. It also includes a line about Yan Hui's benevolence and uprightness with parallels in neither the Analects nor the Shi ji—indicating that the mirror text is not a simple abridgment of the Shi ji disciples chapter.

The other disciple texts underscore this conclusion. In every case, the Haihunhou capsule disciple biographies quote dialogues that are not found in the Shi ji version. Indeed, the relationship of mirror texts to the Shi ji disciples chapter is a fascinating one precisely because they each contain a different (if at times overlapping) selection of anecdotes. At times, the different choices made by the compilers result in very different portrayals of the disciples.Footnote 54

To analyze this further, it helps to formally divide each of the Haihunhou texts into two parts: (1) the biographical narratives for each disciple, plus (2) dialogues or anecdotes featuring said disciple as interlocutor or subject. Contrasting these two parts of the mirror disciple texts, it is clear that each has a very different relationship to the Shi ji chapter. While there is a high degree of overlap between the biographical (i.e., non-dialogical) sections at the beginning and end of the disciple texts, when it comes to the choices of dialogues to be supplied for each disciple, the two texts are completely different.

The biographical narratives appear, for most part, at the beginning and end of each disciple section. For each disciple, Table 1 compares the sections that occur before or after the central dialogic passages in both the Shi ji and the mirror texts. There are, to be sure, some significant differences, such as the way Zigong is introduced and whether his service at the end of his life is recounted, or Zixia's age difference with Kongzi. That said, differences occur within a relatively regular formal pattern shared in both texts. Looking at the mirror text disciple treatments as a whole, we find a general formula, even if not every item occurs in every treatment:

1. Identification: name, cognomen, age difference with Kongzi

2. General description of disciple's character

3. The phrase “once they received training” (ji shou ye 既受業)

4. Dialogues

5. Evaluative comment by Kongzi and/or comments on the disciple's career

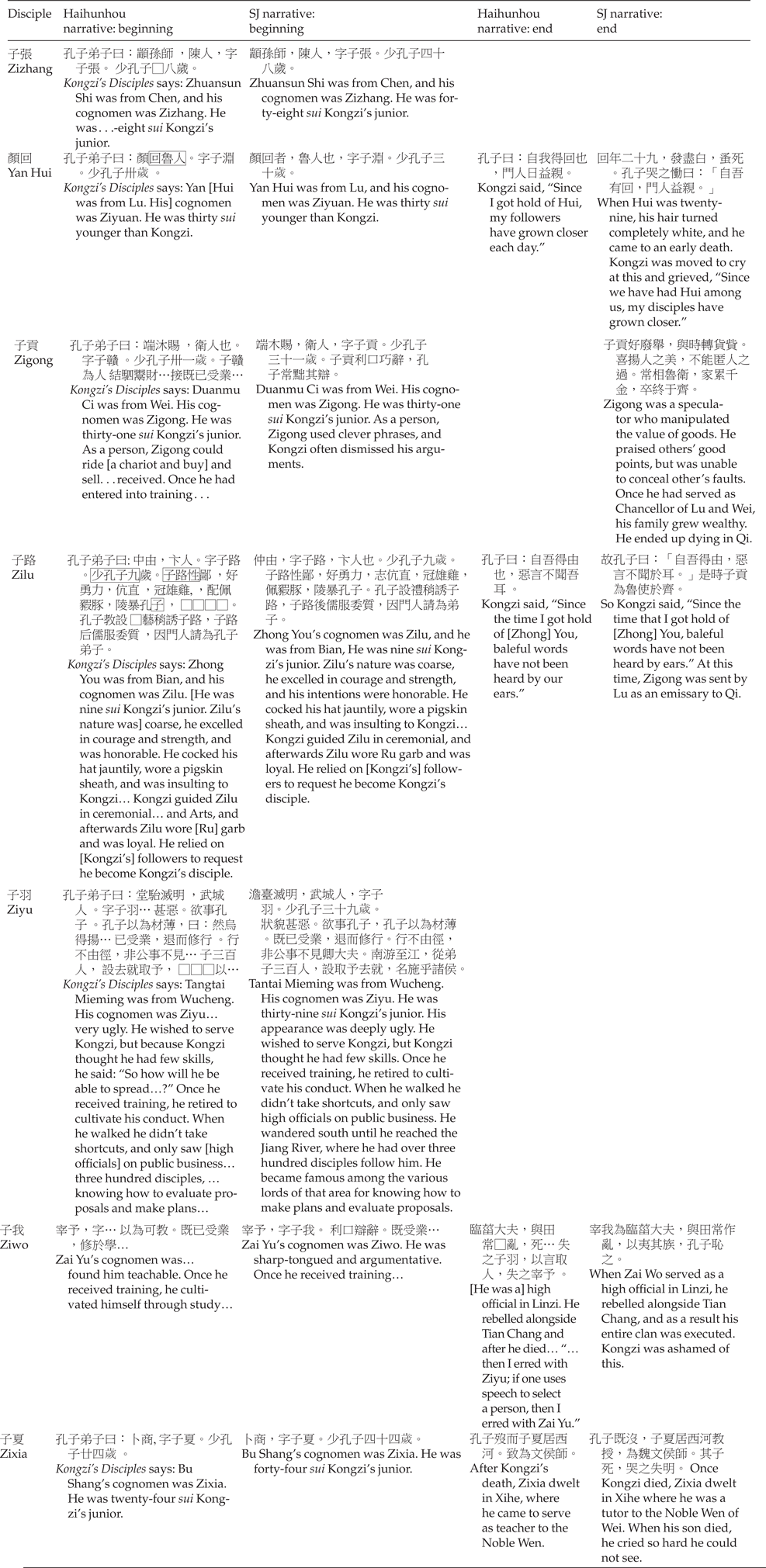

Table 1. The biographical narratives (non-dialogic elements) in the Haihunhou disciple texts, compared with Shi ji “Zhong Ni's disciples” counterparts. Note that the Haihunhou narratives for Ziyu and Ziwo are part of the same block of text, and that block ends with a shared assessment.

While the first and fourth of these elements appear in every biography, Table 1 shows that the other elements are in many (but not all) of the treatments. Despite inconsistencies, when the elements do appear, they appear almost always in the same sequence. However, there are two very notable features that distinguish the mirror text biographies from those of the Shi ji. First, every Haihunhou illustration of a disciple begins with the five-character phrase “Kongzi's disciples says” (孔子弟子曰), a phrase that appears to make at least the “identification” section of the treatment a direct quotation from a manuscript title or a standard oral treatment. Second, for several of the disciples, the Shi ji passages include an additional characterological assessment at the end. For example, both texts end the passage on Zixia by noting he taught Noble Wen of Wei, but the Shi ji treatment ends with the flourish: “When his son died, Zixia cried so hard his vision was impaired.”Footnote 55 The overall formal similarities between the two texts in terms of these biographical sections (items 1, 2, 3, and 5 above) might suggest that the Haihunhou artist was drawing on materials that looked more like the Shi ji chapter, were it not for the fact that the dialogue sections (item 4 above) are so different.

By contrast, the dialogues chosen for each disciple differ substantially in the Shi ji and Haihunhou disciple treatments. Table 2 summarizes these differences using the shorthand of Analects chapter numbers to identify the various dialogues, although it is important to point out that there are variations and discontinuities within many of the dialogues relative to the Analects. The lengths of their accounts differ quite a bit, with the Shi ji parallels often shorter than either the Analects or mirror text versions. The Shi ji also fills in narrative elements more frequently, for example, locating the dialogue between Zizhang and Kongzi found in Analects 15.6 or prefacing the severely abridged dialogue between the Master Ji and Kongzi found in Analects 11.24 with a sentence contextualizing the exchange: “Zilu was serving as steward for the Ji clan.”Footnote 56 The systematic differences suggest both works independently drew upon a common fund of disciple dialogues, or abridged a similar source that had many more dialogues than either compiler chose to include.

Table 2. Dialogic parallels to chapters in the Analects in the Haihunhou disciple texts, compared with Shi ji “Zhong Ni dizi liezhuan.”

One passage is especially telling about the complex relationship between the two texts and between their dialogic and biographical elements. Both the Haihunhou and Shi ji disciple treatments of the disciple Zigong begin with passages that start by locating successive dialogues with the preface “Once he received training, he asked” (既已受業問曰) and “Chen Ziqin asked Zigong” (陳子禽問子贛曰). These narrative elements are followed in the Haihunhou texts by dialogues corresponding to Analects 15.24 and 19.25, respectively. However, in the Shi ji chapter, these very same narrative markers, in the same order, lead into dialogues found in Analects 5.4 and 19.22, respectively. This is evidence that the texts are using a shared narrative frame but inserting different dialogues to enliven their portrayals.

A further complication is the fact that the second of these passages in the Shi ji, parallel to Analects 19.22, identifies the interlocutor as Chen Ziqin, rather than Gongsun Zhao of Wei 衛公孫朝, as does Analects 19.22. Both the Haihunhou treatment of Zigong and the Analects mention Chen Ziqin only as the interlocutor in the single dialogue parallel to Analects 19.25. It is hard to imagine how both texts could have mined sources like the Analects for Zigong stories, and coincidentally placed Chen Ziqin dialogues at the same stage of their Zigong biography—especially since the Shi ji altered it from a Gongsun Zhao dialogue. This strongly suggests that the compilers of both the mirror text and Shi ji disciple treatments (or their proximate sources) were working from similar narrative summaries about the disciples but filled the summaries in with different dialogues and anecdotes. If so, the division of the Shi ji chapters into one chapter on Kongzi and another on the disciples may not have been an editorial decision as much as a consequence of two different corpuses available in the Western Han.

Another passage that appears to confirm this hypothesis is one that appears to capture a Haihunhou artist or copyist making a spontaneous decision to add a narrative summary about one disciple to the biography of another disciple. The biography of Ziyu appears to end on a statement also found in the Lun heng 論衡 about the two times that Kongzi used physiognomy on his disciples but got it wrong: “In using appearance to select a person, he erred with Ziyu, in using his words, he erred with Zai Yu” (以貌取人,失於子羽;以言取人,失於宰予也).Footnote 57 However, inserted into the middle of that statement is the biographical narrative for Zai Yu, complete with several elements of the narrative formula outlined above.Footnote 58 That the Haihunhou treatments contain dialogues not present in the Shi ji treatments, and vice versa, is less significant, I believe, than the fact that the two select dialogues differently for each disciple. As luck would have it, both versions provide information on the different sources they used to construct their disciple biographies.

In the Haihunhou treatments of the disciples, each illustrated disciple text begins with the same phrase (Kongzi dizi yue 孔子弟子曰). It is possible but unlikely that the mirror text simply is talking about the Shi ji chapter and using a different name. However, the pattern of differences between the dialogues used in the Shi ji disciple chapter and the mirror texts shows that the current version of the latter could not be the only source for the former. It is possible that the citation of Kongzi dizi might only extend to the identification of the disciple's names, cognomens, and relative ages. In that case, the Kongzi dizi cited in the Haihunhou text from around 59 is formally very similar to a text with a similar title attributed to a figure who lived two centuries later, Zheng Xuan 鄭玄 (127–200). The Sui shu 隋書 lists Zheng as compiler of the Lun yu Kongzi dizi mulu 論語孔子弟子目錄.Footnote 59 Perhaps Zheng Xuan's innovation was to take earlier Kongzi dizi texts, like the one the Haihunhou artist may have consulted, and trim them to try to produce authoritative identifications for a subset of disciples in the Analects.Footnote 60

In the case of the Shi ji, Sima Qian's comment on his disciple chapter contains a statement that he was using a different source for his biographies of the disciples than others were. The chapter reads:

太史公曰:學者多稱七十子之徒,譽者或過其實,毀者或損其真,鈞(均 ?)之未覩厥容貌,則論言。弟子籍出孔氏古文, 近是。余以弟子名姓文字悉取論語弟子問并次為篇,疑者闕焉。

The Grand Archivist said: When most scholars invoke the 70 followers of the Master, their praise sometimes exceeds the truth, and their criticism sometimes minimizes the reality. In weighing them (or, “In both cases”), since no one can see their personal appearances then we must judge their words. The Dizi ji comes from the Kong clan ancient texts and so is close to the truth. I have used the disciples’ surnames, given names, and its text in all cases to select from the Lun yu disciples’ questions and arrange them in this chapter. Little of it is doubtful.Footnote 61

Sima Qian identifies the Dizi ji 弟子籍 as a source that is superior to others (perhaps like the Kongzi dizi) in part because of its pedigree as a document found in the Kong family source. Above, it was argued that what we appear to be seeing is the matching of shared biographical narrative sources with different selections of dialogues. Sima Qian's own description of his procedure says something very much like this.

While the shared narrative biography sections of the mirror texts and the Shi ji biographies may have relied on mu lu style texts, it is also possible that the section quoted as part of Kongzi dizi (oral or written) was a longer part of each capsule biography or the entire biography. In that case, a Kongzi dizi may have originally been compiled from narrative biographies of the disciples, but without dialogues, perhaps in the late second century b.c.e., and would have looked more like the narrative entries in Table 1. At the start of the first century b.c.e., at the beginning of the period of “disciple vogue” and the wide circulation of the Analects, Sima Qian or perhaps his grandson Yang Yun decided to fill in the narrative framework with passages coming from the Analects or the same compilations of dialogues from which the Analects were later drawn. Those would be more like the strings of dialogues in Table 2, a process recalling the Zuo zhuan's 左傳 addition of narratives to the narrative framework of the Chunqiu 春秋. This alternative might explain why the Shi ji disciples chapter is unique in the Shi ji in being primarily composed of dialogic building blocks. It might be the case, then, that our two sets of disciple treatments represent two draft collations in that process, or two independent selections from another larger collation.

The Significance of Kongzi and His Disciples in Han Court Culture

Michael Loewe has recently observed that during the two Han dynasties Kongzi was not seen as a figure whose “pronouncements affected the choice of a policy to be taken by the imperial government.”Footnote 62 Since Kongzi was an increasingly important figure, where did his cultural significance in this period come from?

In the first century b.c.e., portraits of Kongzi's disciples were closely intertwined with the development of the image of Kongzi, just as their voices were a major part of most of the dialogues of the Analects. Independent texts devoted to particular disciples circulated in the late Warring States period, and texts that centered on the disciples circulated as a group in the late Western Han and early Eastern Han.Footnote 63 A related aspect of the special role of Kongzi's disciples in Han culture may be glimpsed in the Lunheng of Wang Chong 王充. Wang begins the “Questioning Kongzi” (“Wen Kong” 問孔) chapter by arguing that Kongzi's disciples were no more gifted than the men of letters in Wang's day. Yet Wang repeatedly makes the point that Kongzi's disciples were exemplary in their willingness to question Kongzi in ways that Wang's contemporaries are unwilling or unable to do.Footnote 64 Kongzi's disciples were good candidates for high office because they recognized their responsibilities to interrogate the pronouncements of a fallible leader. This shows how the relationship between Kongzi and his disciples was read in some Han sources as a model for that between a ruler and his ministers.

In this light, the wise ruler might, each day, look to his screen and mirror stand to be reminded of the time Kongzi placed himself on the same level as Yan Hui, a theme of Yan Hui's mirror text, which recounts Kongzi saying, “Only you and I are capable of doing this” (唯我與爾有是夫).Footnote 65 He might also be reminded of Kongzi's admonition against superficially evaluating people based on looks or words, the chief theme of the shared biography of Ziyu and Zai Yu. The visual image of the disciples, next to biographies full of Kongzi's evaluative comments, speak to the Kongzi's importance as a judge of good character. After all, according to the “Kongzi shijia,” Kongzi told Duke Ai of Lu that: “good government lies in the selection of ministers” (政在選臣).Footnote 66

The richness of these Haihunhou materials suggests many avenues for research. It has significance not just for the formation of the early images of Kongzi and his disciples, but also about the ways that chapters of the Shi ji and other transmitted texts were formed from earlier materials and subsequently emended. In addition, it shows how stories about Kongzi and his disciples were used in the Han as a didactic proxy for lessons about the ruler and his officials, with an emphasis on the superior's correct evaluations of the skills and character of subordinates. This also suggests an explanation for Loewe's observation that Kongzi was not often invoked during the two Han dynasties in specific policy debates. In the Haihunhou mirror texts, Kongzi may have stood in for an ideal ruler, celebrated for his training and evaluation of his subordinates, instead of a successful official or itinerant advisor, roles central to other early accounts. Kongzi's interactions with his disciples were models for Liu He, and their images and biographies on the mirror frame served as a historical example of the “Kingly Way” that rendered it “deeply felt and clearly seen.”