One of the central debates in international relations dissects what role the public plays in foreign policy and world politics. Many liberal theories of international politics assume both that the public actively constrains foreign policy in democracies and that these public constraints have positive policy repercussions.1

See Bueno de Mesquita et al. 2003; Russett 1993; Martin 2000; and Schultz 2001, for a summary of arguments and evidence.

See Schultz and Weingast 2003.

However, realist critics argue that the empirical record is not uniformly consistent with the public-as-constraint assumption. These scholars suggest that the systematic spikes in public approval for a leader during international conflicts—known as the rally-'round-the-flag effect7

The literature on the rally-'round-the-flag effect is too voluminous to cite comprehensively. Hetherington and Nelson 2003 includes a succinct summary of the patriotism arguments; while Brody 1991 explores the logic of the opposition criticism perspective.

See Mueller 1970. Even the opposition criticism model—Brody 1991—assumes that the public follows elite cues rather than constraining policy from the bottom up.

Morgenthau 1967; 558.

In this article, I suggest that the conventional interpretations of the rally-effect and the foreign policy processes they imply suffer from both theoretical and empirical anomalies.12

Despite these problems, the rally effect has continued to be cited by critics of the public-as-constraint assumption. For a recent example, see Rosato 2003.

I conduct several tests of the informational theory on data taken from the United States and compare it to conventional explanations. Specifically, I expect that foreign policy actions and crises that carry a high probability of post hoc verification and meaningful punishment will lead to large rallies in the United States. The observable implications of this approach are that the rally should correlate with the costliness of the foreign policy action, the electoral calendar, active term limits, political security, control of congress, freedom of information laws, and trust in government. The model and supportive empirical findings suggest that the presence of a rally-effect should not be used as evidence that the public is irrelevant to international affairs. Conversely, rally behavior can be representative of a retrospective-accountability equilibrium where leaders act in the public interest and the public supports those actions.

This article proceeds in four parts. First, I critically consider the conventional models of public opinion change. Second, I attempt to build an integrative model of the rally by focusing on the factors that centralize but then retrospectively facilitate the dynamic diffusion of foreign policy information. The structure of this informational argument is illustrated formally within a principal-agent signaling framework. Third, I present the hypotheses and research design. The aim of this section is to formulate adequate tests of the informational theory of the rally. Finally, I present the results of a battery of empirical tests, including both in-sample and forecasting methods. The findings offer strong and consistent support for the informational model and suggest several avenues for future research linking secrecy, accountability, and international relations both within and beyond democratic contexts.

Previous Explanations for the Rally

Patriotism

With the advent of political polling, scholars of international politics noted that public approval of a U.S. president tended to rise during international crises.13

However, Mueller proffered the first systematic explanation of the rally in the United States.14 This research suggested that patriotism and nationalistic emotion explain the empirical fact that support for the U.S. president increases in times of international crises, even when the crises seem to be handled poorly. Mueller's causal logic specified that international conflict, regardless of blame, causes the public to feel threatened. This threat to core values reminds people of their patriotism and love of country. As such, the public rallies to symbols of that patriotism, such as the flag. The national leader, as the personal embodiment of the state, is one of the most powerful patriotic symbols. Thus, international crises infuse the public with strong patriotic feelings and renewed support for the leader and country.Is Patriotism Blind?

While the patriotism explanation is consistent with the observation that approval of the president in the United States increases on average during international crises, other findings suggest that patriotism is not the end of the story. First, and most obviously, the size of the rally in the United States has varied considerably over the last fifty years. According to one data source, rallies have varied between significant losses in support (−13 percent) to large gains in approval for the executive (+33 percent).15

Rallies as coded in Baum 2002 and updated through 2004 by the author (see below).

Six of the twenty-six negative rallies would be considered significant given conventional statistical significance levels (p < .05). Four of these are considered defensive crises.

I would like to thank an anonymous reviewer for highlighting this point.

Of course, these could be small rallies that become overwhelmed by other factors.

Second, it appears that the public does not reflexively rally to support the president, but at least pauses to consider the avowed goals of the foreign policy. Several authors19

report that crises involving defensive versus offensive goals, at least as publicly espoused in the press, garner larger rallies for the U.S. president. Jentelson and Britton20See Jentelson and Britton 1998.

See Hetherington and Nelson 2003. This rewriting does not make the amended theory any less true, ex post. It remains an empirical question whether the offensive/defensive goals explanation supersedes other explanations.

Finally, there is also a strategic paradox inherent in the patriotism argument. If citizens know they are patriotic, tending toward supporting a president during an international crisis, they should be aware that they are vulnerable to political manipulation. For example, an executive interested in reelection need only initiate a (defensive) international crisis to increase his popular support and reelection probability according to the patriotism logic. Knowing this tendency, the public should be skeptical of blindly supporting a leader. If members of the public are even marginally strategic, merely having the innate drive toward patriotism may not be enough to create rally behavior. Knowing that leaders can use patriotism to their private advantage22

I explore the specific private advantages leaders may gain below.

I analyze the strategic logic of rally events and test several hypotheses relating to elections, low approval, and scandals below.

Opposition Politics

In response to many of these anomalies in the patriotism theory, Brody and Shapiro24

constructed an alternative explanation for the rally effect. They suggest that during periods of international calm, in the absence of a foreign policy crisis, presidential approval reflects the thrust and parry of elite politics. Each party attacks and defends in turn. Presidential approval oscillates with these oppositional forces, as the public rallies not to patriotic symbols but their party's message. However, according to the opposition theory of the rally, the opposition elite ceases its criticism during an international crisis. Therefore, the rally effect occurs because the downward pressure on presidential approval, exerted from opposition attacks and criticism, is removed. Approval rises because only voices supporting the president are relayed to the public.The opposition theory therefore not only predicts that presidential rallies will occur as an international crisis breaks out, but also predicts two additional, and testable, empirical regularities. First, one should see opposition criticism of the executive decrease25

One should also observe an increase in average support.

The problem for the opposition-criticism theory is that these two additional hypotheses have received, at best, mixed support. While Brody26

provides evidence to support the importance of opposition cues in explaining the rally, others have been unable to replicate these findings using alternative data sources. Baum and Groeling27See Baum and Groeling 2004.

See Oneal, Lian, and Joyner 1996.

Less systematically, Hetherington and Nelson 2003 highlights a few anomalous cases.

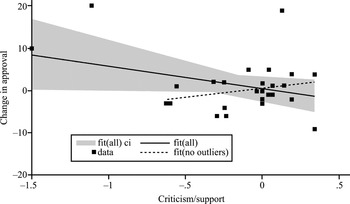

To further probe the plausibility of the opposition theory, I created a daily measure of opposition criticism coded from Reuters news stories from 1991 to 1998. The scale ranges from −6 to 6 with negative numbers reporting greater criticism and positive numbers reporting support.30

For example, an opposition group denouncing the government would score a −6, while another political party rewarding the government would receive a +6 score. The scale was created using a panel of expert coders, the Virtual Research Associates (VRA) parsed events, and the IDEA event coding scheme. See Bond et al. 2004; and King and Lowe 2003. Only opposition statements and actions targeted at the national executive and the government are coded on the criticism scale. More information on the criticism scale is included in Colaresi 2004.

Rally events are coded as in Baum 2002.

For example, at the .10 level of significance.

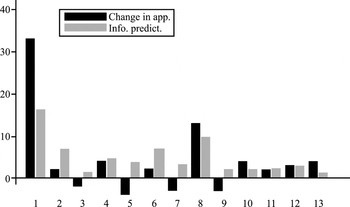

The univariate distribution of criticism (−)/support (+) the week before, during, and the week after a rally event

Figure 2 plots the results of two bivariate regressions of immediate opposition criticism (the day after an international crisis) and the subsequent rally (the change in presidential approval pre- and postevent).33

The opposition-criticism measure is as explained above. The substantive results are even less supportive of the opposition theory when different lags are used and when opposition is measured in a change metric. Rally events and intensities are as measured in Baum 2002. See below for a more complete definition of the data. The rally intensity is measured with the change in presidential approval.

Bivariate regression results for opposition criticism and the rally (with and without outliers)

What Rally?

Some recent research has called into question whether the rally effect even exists. Oneal, Lian, and Joyner34

See Oneal, Lian, and Joyner 1996.

For a discussion of MID data, see Jones, Bremer, and Singer 1996.

Despite these anomalies, there are several strong reasons to continue to probe the interaction between the public and elite foreign policy decisions. First, the anomalous empirical findings rely on an operationalization of foreign policy events that does not comport with the conception of a rally as suggested by Mueller.36

Mueller 1973.

Ibid., 209.

See Kernell 1978.

This seems reasonable given the domestic focus of inaugurations.

See Oneal, Lian, and Joyner 1996.

Controlling for salience, for example by measuring placement in a major newspaper, alleviates some of these problems.

James and Rioux 1998.

However, it is apparent that there is more variance in the way the public reacts to U.S. foreign policy actions than suggested by the original conception of the rally-effect. What one needs is a theory that can predict ex ante which events are ex post likely to lead to rallies and which are not. Conceptualization of variables must be tied to a theoretical model to avoid the charge that the measures were selected based on the dependent variable. Additionally, a research design including out-of-sample prediction can help alleviate concerns that the model was created to “fit the data” and support the external validity of the theoretical model.

The Building Blocks: Alert Patriotism and Loud Opposition

The anomalies do not suggest that either the patriotism or opposition-criticism theories are useless. Work by Baum and Groeling44

has made considerable progress in updating the political opposition argument to account for media effects. These authors suggest that the public's perceptions of approval or disapproval are contingent on available information. The vast majority of this information comes from the media. Therefore, Baum and Groeling specifically analyze media incentives for broadcasting pro- or antigovernment information to the public. Below, I offer a theory that builds on and generalizes this logic of information accumulation.The strengths and weaknesses of previous research can serve to triangulate several attributes that a more successful theory of the rally must contain. As the patriotism theory avers in the U.S. case, the public generally cares about the country. The majority of the public would rather see the nation continue to exist and prosper. At the most general level, the preferences of the public—those who constitute the rally or those who stay in opposition—should be part of any explanation. Although patriotism may not be blind, it can still exert an important influence on decisions. Similarly, the strength of the opposition-criticism theory is that it identifies a significant source of information for the public as citizens make up their minds to support or oppose presidential action. Even if the opposition is not immediately silent, it may be part of the rally story. Further, other sources of information may be available to the public, including information emanating from nonexecutive branches of government, independent media investigations, and whistle-blowers. Opposition silence or voice and the transmission of that information may be only the tip of the information iceberg. From this perspective, the rally occurs because citizens are persuaded to support an action based on the information they receive. The institutional, operational, and political contexts in which this information is sent could have a profound effect on whether it is perceived to be credible and persuasive.45

See Lupia and McCubbins 1998.

An Alternative Explanation: Information, Institutions, and Foreign Policy

Temporary Information Asymmetries

A leader's foreign policy decisions are calculated within a dynamic institutional context. Even in democratic states such as the United States, these institutions include mechanisms for the centralization and concentration of foreign policy information in the executive. Classification is carried out through legal confidentiality clauses, penalties for endangering the nation (treason), and executive privilege. It has been generally acknowledged that information centralization and concentration mechanisms are executive powers necessary for implementing and formulating consistent and effective foreign policy. Quite simply, policies that involve surprise, hiding, lying, sneaking, and bluffing require the executive to have private information. If everyone in a country had immediate access to all information on foreign policy, it is highly probable that another country would also discover that private information.46

Bargaining, even with an international ally over trade policy, is less effective for a state that has no private information. The value of secret information is even greater during military maneuvers and planning.There are two categories of relevant private information held by the executive. The first is the public cost/benefit forecasts. How strong is the threatening state or how destabilizing is the international situation? What are the net benefits of foreign policy action? For example, in early 2002, the U.S. public was asked to support military intervention in Iraq. The information necessary for the public to make an informed decision on the merits of this operation was classified. The probability of gaining public benefits from action, in this case the expected reduction in threat posed by weapons of mass destruction, severing a potential Iraq–al Qaeda alliance, and eliminating a regional destabilizing force, depended on the current state of the world (did those threats exist) and the likely state of the world at the end of the war (would action reduce the threats or exacerbate them). While point predictions concerning these benefits were made public before the war, the certainty with which those point predictions held (the standard errors of the predictions) and the methods by which the predictions were derived (from what sources of what credibility) were private information.47

Additionally, the classification of uncertainty estimates is pivotal when the ambiguity is asymmetrical around the publicized point prediction.

Derived at least in part as an unintended consequence of these primary information asymmetries, a second executive information monopoly concerns the private benefits that might accrue to the leader if the public reflexively supported foreign policy action. International confrontations may allow presidents to brandish their leadership skills with photo opportunities employing military personnel and equipment and possibly divert press and public attention from domestic problems. For example, George W. Bush took to calling himself a “war president” after 9/11 and Bill Clinton was accused of diverting attention from his personal scandals when he launched cruise missile attacks on al Qaeda targets in 1998. McMaster claims that President Lyndon B. Johnson twisted the facts surrounding the Gulf of Tonkin incident to boost his reelection chances.48

Gibbs 1995 for his relevant discussion of “internal threat” motivations.

See Kaufmann 2004 for a summary of the public-elite discourse in the prelude to the 2003 Iraq War. Action might also motivate support for other facets of a president's agenda, rather than promoting public security. For example, trumpeting international threats may help to increase defense spending, if believed, on specific presidential priorities. John F. Kennedy and Ronald Reagan highlighted Soviet threats during the Cold War to attempt to push for increased spending on missile and Star Wars programs respectively. Similarly, George W. Bush underlined the threats from China, North Korea, and Iran when attempting to motivate support for his missile defense shield.

Because the public is unsure of the threat level they face and what options are most likely to efficiently maximize public security, private presidential motivations could be wrapped in public interest rhetoric. For example, ex-CIA Sudan station chief Milt Bearden's first reaction to the 1998 cruise missile attacks on the night of Monica Lewinsky's return to grand jury testimony was “what do they know? What is this about?”, referring to the information and motivations that drove the specifics of the retaliation.50

Frontline, 13 September 2001. Full interview can be downloaded from 〈www.pbs.org/frontline〉.

The attack in Sudan has drawn criticism on this point.

The United States and other democracies also have constructed, maintained, and at times ignored, countervailing institutions that create an opportunity for the diffusion of retrospective foreign policy information. Most fundamentally, freedom of speech allows for different points of view and new information to be offered, shared, and exchanged with the public. U.S. laws include provisions for legislative and judicial subpoena and oversight on international executive decisions. Currently in the United States, there is a practical, affordable, and judicially reviewed method for the public to query information under the 1974 revisions to the original Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). Similarly, once information is in the public view, the transmission of that information in press is usually protected. In the United States, these protections were illustrated in the Pentagon Papers case.52

See Prados and Porter 2004.

This figure is a simplification. Direct information flows from foreign policy facts to the public, unmediated by the executive, are not only theoretically possible but real. The recent U.S. scandal over the Abu Ghraib prison illustrated this process. It should be noted that the same diffusion institutions are still at work.

The centralization and potential diffusion of foreign policy information

It is important to note that the mere presence of an opportunity for foreign policy facts to reach the public does not imply that information diffusion is automatic and constant. On the contrary, the willingness of both the press and the legislature to use their publication and oversight powers varies over time in predictable ways. For example, the press is more likely to probe and broadcast information on dramatic foreign policy actions. The legislature is more likely to hold hearings and investigate presidential decisions under divided government, when intraparty cooperation between the executive and legislative branches does not counterbalance the institutional political checks on executive power.54

Furthermore, the public's trust that these political institutions police themselves ebbs and flows over time (see below).

Information taken from and classified using the Policy Agendas Project. See 〈http://www.policyagendas.org〉; and Baumgartner and Jones 2005. The difference in means is significant at the .05 level using a t-test.

What emerges from these countervailing forces in the United States are volatile tides of information centralization within the executive and diffusion of information to the public. By design, the public is relatively ignorant of the immediate facts on the ground in a foreign policy crisis, but may be confident that information will eventually come their way, given the right operational and political circumstances.56

While the resulting information will not be encyclopedic, it is likely to provide ample basis to inform retrospective judgments. See Lupia and McCubbins 1998 for a discussion of the many mechanisms by which incomplete information can lead to near-efficient decision making. Note that opposition voices can play a large role in this process.

For example, when one party controls the executive and legislative branches.

For example, the situation in the United States before the Freedom of Information Act was strengthened in 1974.

A related set of democratic institutions allows the public to punish a leader for enacting policies that they do not perceive to be in the national interest. Yet again, the opportunity to punish a leader if foreign policy abuse is discovered is not constant within the United States, or in other democracies. The most obvious form of leadership punishment is direct electoral defeat. Elections serve as low-cost mechanisms to punish and deselect an executive from power. This suggests that the information diffusion process must be complete before election day. Since diffusion occurs with a lag, a crisis and foreign policy action that occurs just before an election is unlikely to be scrutinized in time. A leader in a precarious political situation (low approval or facing a scandal) or who is term-limited, also may avoid the conditional electoral punishment.59

However, additional punishments include imposing further electoral defeats on the leader's party, and rejecting policies that the leader may care about. Finally, reporters, academics, or other members of the public are free to accost a leader's record and legacy in print.

I explore the logic of this argument below, but a preview will help to frame the discussion. The results of a simple signaling model suggest that institutions and situations that protect and accelerate post hoc information revelation and contingent leadership punishment help to create the atmosphere in which rallying is a rational response to foreign policy action. When the public is weighing its reaction to a presidential foreign policy initiative, it takes into account the likely motives of the leadership. If the current crisis provides the leadership with an institutionally constituted opportunity to politically manipulate foreign policy for private gain, through information control, and no counterbalancing incentive to avoid abuses of foreign policy power exists, the public is likely to be skeptical of foreign policy moves. On the other hand, situations that provide an active disincentive to mislead the public increase the probability of a public rally, even in the face of limited contemporaneous information. The post hoc revelation of abuses of power and opportunity to punish any abuses, with both the public and the leadership's common knowledge, supplies just such an incentive. In short, some situations lend themselves to elites credibly signaling foreign policy needs to the public because leaders are vulnerable to punishment if they abuse their temporary informational advantage. This variation leads to several potentially observable patterns in rally behavior in the United States.

Signaling a Rally: A Principal-Agent Model

The informational argument can be illustrated in a simple incomplete information principal-agent model. The structure of the game is as follows,

1. Nature chooses an international crisis situation. This is revealed to the agent (the president) but not the principal (the public). The principal has belief p ∈ (0,1) about whether the specific situation is one where action will accrue private benefits to the agent (β) or the complementary belief (1 − p) that action in this case will provide a benefit to all (θ).

2. The agent chooses action α or ¬α.60

Some may object to a model of the rally that treats the public as responding to a leader's action. However, both the opposition and foreign policy restraint defensive goals hypotheses rely on a similar, though unstated assumption. For example, in the opposition-criticism argument, a crisis arrives, then the leadership and opposition act and comment, and the public rallies or not, conditional on this dynamic. Similarly, in the foreign policy restraint/defensive goals hypothesis, the rally depends on the previous government explanation of its goals and the press coverage of that explanation.

3. The game ends with the status quo if ¬α is chosen. Payoffs are (0,0).

4. If the agent acts (α), the principal chooses whether to support (S) the action or oppose (O) it.

[bull ] Support leads to payoffs (β − (p(ν|α) × φ),−γ) in a β world and (θ,θ − γ) in a θ world. γ includes both the cost of the action and institutional maintenance costs. p(ν|α) represents the probability that the principal will be able to verify that the action was not in their interest, where p(ν|α) ∈ (0,1). φ measures the level of punishment that an agent can incur if verification occurs. β measures the private benefits and θ indicates the public benefits.

[bull ] Oppose leads to payoffs (τa,τp).

For simplicity, I define ε = p(ν|α) × φ. The costs γ and φ are constrained to be greater than 0, as are the benefits β and θ. Further, θ > γ, constraining the game to model crisis situations where the potential benefit to the national interest/security of the state is strictly greater than the costs incurred in a θ world.61

If this inequality is reversed, the distinction between the β and θ world breaks down, as does the uncertainty. Regardless of the state of the world, the public would like to avoid α if possible.

There are a multitude of simplifications within this model and theory. I follow other work in suggesting that the worth of a model should be measured by the usefulness of its empirical predictions rather than the truthfulness of its assumptions. As noted by Morton 1999, all models, by design, include false assumptions.

One slight difference is that I interpret the uncertainty in the model as reflecting private information about the crisis situation rather than private information about the “type of player.” This is similar to the Lupia and McCubbins 1998 model that separates uncertainty about the situation and the player.

Proposition 1: In situations where β − ε > 0, no pure separating equilibrium exists.

The proof is included in the Appendix. In situations where retrospective information diffusion and conditional punishment are unlikely, foreign policy action does not convey information to the public. Since θ > 0, the agent will prefer α to ¬α, if the anticipated probability of support from the principal is sufficiently high. However, the converse is true if opposition is the principal's likely strategy (τp < 0). When the outcome (β,α,S) is better than the status quo for the agent (β − ε > 0), the incentives for a β crisis are similar to the incentives in the θ case. Both crisis situations supply the agent with an incentive to act (α) when the anticipated probability of support from the principal is high enough. Similarly, both types have an incentive to avoid being opposed, because τa < 0. If the principal is skeptical enough to prefer opposition to support, then both crisis types will lead an agent to avoid α. If the principal is trusting enough (that is, p is sufficiently low), both types of agents can take advantage of that and offer α. For the principal, support strictly dominates oppose when p < [−τp + (θ − γ)]/θ. Significantly, seeing α or ¬α does not supply the principal with information on the crisis situation. The two pure strategy pooling equilibria under these conditions are (¬α,¬α,O) if p > [−τp + (θ − γ)]/θ, and (α,α,S) if p < [−τp + (θ − γ)]/θ.64

This game includes a continuum of mixed strategy equilibria when: p = [−τp + (θ − γ)]/θ. These are described by: (α,α,σp(S) > m), where m = −τa/[((−τp + (θ − γ)/−θ)(β − ε − θ)) + θ + τa] and σp(S) is the probability with which the principal plays support.

These pooling equilibria have significant implications for the interaction between foreign policy and public opinion in the United States. When post hoc information diffusion and contingent leadership punishment are unlikely (ε < β), for example, because of proximate elections, unified government, or a disinterested media, either the principal can be taken advantage of, given β and a low enough p, or an agent can fail to garner principal support, given θ and a high enough p. Here, policy action and support depend to a large extent on prior beliefs, and these beliefs are not updated based on action. Therefore, action does not credibly signal an international threat.

Proposition 2: When τa < β − ε < 0, a separating equilibrium exists where α is chosen only in a θ situation, and the principal supports that action.

In crisis situations where principals are sufficiently confident that they can recognize and punish agents for acting in the private interest (β − ε < 0), only a θ situation will lead an agent to offer α. Agents in β situations do not offer α, because they prefer the status quo (0 > β − ε). Conversely, θ situations do present an incentive for α, over ¬α (θ > 0). The specific situations that allow for post hoc verification and punishment, by raising ε, create the conditions for an informative signal to principals that the situation is one of national rather than private interests. Knowing this, principals can update their beliefs (p|α) about the crisis situation and judge that support rather than opposition is their best strategy. Under these key conditions, skepticism does not lead to inaction (¬α) but rather to both action and support. When principals see a signal, they can be confident that the situation calls for action in the national interest. Active checks on the president as the foreign policy agent, through an active press following a hot story, or an opposition-controlled legislature, can both reduce private-interest action (those that are solely in the private interest of the agent) and induce principal support (due to the informative signal).

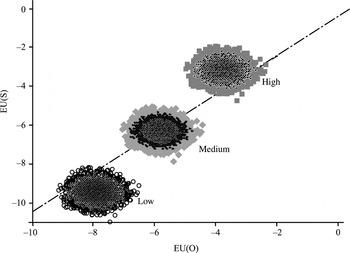

Hypotheses

By aggregating the signaling model results over a diverse population of citizens, the informational perspective leads to several new and specific observable hypotheses related to the rally effect in the United States. The sunflower plot in Figure 4 illustrates the process with a population of citizens where the signaling model sets the mean expected utility of support (EU(S)) and opposition (EU(O)) for individuals but other factors lead to deviations. The greater the mean expected utility of support, relative to the mean expected utility of opposition (EU(S) > EU(O)), the greater the proportion of the population likely to rally. In Figure 4, three simulated crisis situations are represented by the three distributions. The greater the area65

This is represented in two dimensions by the density of the dots in the sunflower plot. If one were to project these plots in three dimensions, the third axis would represent the density or frequency of dots falling on the grid.

Sunflower plot of hypothetical expected utility distributions

Specifically, this perspective suggests that the size of a rally will be related to the probability of ex post verification and punishment for private versus public gain.66

Where Proposition 2 holds, the citizen distribution of support should look like the “high” distribution in Figure 4.

On the operational level, the probability of verification and penalty vary with the action chosen by the executive, when holding other institutions and concepts constant. Different types of actions facilitate greater or lesser degrees of scrutiny, economic cost, and direct diffusion of information. For example, one can think about actions leading to information diffusion in at least three ways. First, when troops are on the ground, there are additional eyes and ears that can report what they see. Troops not only talk to the government but also to networks of friends, family, and sometimes news organizations. Second, the mobilization of military strength costs money. The greater the budgetary strain, the more likely a move is to stir up legislative and press attention. In these cases, the power of subpoena and other post hoc checks on executive power are more likely to be used. Finally, dramatic events such as direct military conflict increase the probability of press and public attention. Again, drama increases the chances that information about the crisis will diffuse to the public ex post. This leads to the hypothesis that the more “costly” the action for the leader—meaning the more likely that action is to subject the leader to after-the-fact verification and potential punishment if motivated by private gain—the greater the number of people who will be persuaded to support the action.67

Another way to phrase this is that a brigade is worth a thousand words.

Specifically, I organize foreign policy actions into five categories (see Table 1). Purely verbal actions have the lowest verification propensity because they do not put any eyes and ears on the ground, fail to generate mobilization costs,68

Talk is cheaper than tanks.

By modeling the rally as a function of presidential action, I am assuming that the expected immediate rally does not in turn explain the costliness of action. I probe this assumption using a two-stage least squares model in the Appendix. There is some anecdotal evidence that presidents do not form policy solely on the basis of conditional public opinion forecasts. Clinton argues that he ordered the cruise missile strikes on al Qaeda targets in 1998 despite warnings from his staff that the action would draw heavy criticism; see Clinton 2004. Kennedy expected to be criticized domestically for ordering a blockade of Cuba instead of aggressive air strikes during the Cuban Missile Crisis; see Kennedy 1969. However, leadership justifications and motivations such as these should be taken with a healthy dose of skepticism. It remains an empirical question whether approval drives action or action drives approval.

Potential costliness of foreign policy actions, ex post

H1: The greater the likelihood that an action will draw media and legislative attention, the greater the rally.

In the United States, as well as other democratic contexts, the probability of a leader losing office can also affect the perceived utility of supporting an executive's foreign policy choices. A president that is suffering from political trouble may benefit from a foreign policy diversion and rally. This political trouble increases the value of β for the incumbent. For example, some political opponents suggested that President Clinton timed his punitive cruise missile strikes against al Qaeda in 1998 to divert attention from the Lewinsky scandal. The suggestion is that a president could benefit from a foreign policy crisis (conditional on a rally) even if that crisis was not in the public interest.

This perverse incentive simultaneously raises the citizens' prior probability of a β world (p). Citizens may be aware and skeptical of a weak politician attempting to politically manipulate foreign policy. Therefore, a weak incumbent should be less able to mobilize a rally, given the comparatively higher value of β (the private interest in a crisis) and p (the prior probability of a crisis being in a leader's private interest). Additionally, presidential scandals could have the same political effect. A president that was on his political heels because of a scandal relating to abuses of power (Watergate), secrecy (Iran-Contra) or lying (Lewinsky scandal) may be in danger of impeachment. Again, this serves to increase the public's skepticism of any future crisis (p), while increasing a leader's incentive to initiate action for private gain (β).

These political insecurity hypotheses are also related to the value of φ, the contingent punishment (and thus by definition ε). For example, φ may be lower for an insecure and scandalized leader because the probability of losing office has already increased. Therefore, the threat of being evicted from power if an abuse of power is uncovered is not an effective deterrent. These politicians have less to lose politically by acting in their private interest (α|β).70

However, this only captures one of many potential vectors of a leader's utility function. For example, if leaders care not just about holding office, but also about their legacies, political party, or policy concerns, numerous punishments remain to be levied.

H2: Foreign policy actions initiated by an executive with weak approval ratings will lead to a smaller rally than other types of situations.

H3: Foreign policy actions initiated when an executive is involved in a scandal will lead to smaller rallies than actions initiated under normal circumstances.

Five additional observable hypotheses can be derived from situations that raise or lower the probability of ex post political verification (p(υ|α)) and punishment (φ).71

Which together define ε.

There are many situations when the president's party will criticize the executive. The difference is relative, not absolute.

Fourth, laws that institutionalize the release of national security information and open government archives increase the probability of retrospective information revelation (p(υ|α) and ε). In the United States, the implementation of the 1966 Freedom of Information Act and the 1974 Privacy Act served to increase post hoc verification probabilities for the public. Knowing this, leaders are less likely to act in their private interest and the public is more likely to support foreign policy action. Finally, post hoc verification depends, to some extent, on the government itself to function. In the United States, checks and balances must operate to bring dubious actions to light. Legislative committees must oversee rather than overlook the executive's policy actions. The courts must be trusted to punish abuses of power. It is also helpful if the executive branch is willing and perceived to police itself.73

For example, the naming of special prosecutors and investigation teams can serve the purpose of self-policing. The naming of Lawrence Walsh as a special investigator to the Iran-Contra affair is one example.

Political situations, signaling model parameters, and rally hypotheses

H4: Foreign policy actions initiated under conditions of divided government will lead to a greater increase in support for a leader, as compared to actions under unified government.

H5: Foreign policy actions initiated in an election year will lead to a smaller rally than other foreign policy actions.

H6: Foreign policy actions initiated by a term-limited incumbent will elicit a smaller rally than actions initiated by other types of incumbents.

H7: Increases in the institutionalization of public access to national security archives and retrospective information will lead to larger rallies.

H8: The greater the percentage of the public that trusts government institutions, the greater the size of the rally.

Methodology

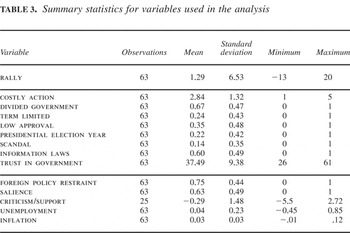

In order to test the new hypotheses suggested by the informational theory, I assemble data on rally events and the relevant independent variables. To measure costly action, I categorize the rally events listed in Jentelson and Baum74

by their differing verification probabilities. All of these events were sorted as either verbal, small-scale, or large-scale mobilizations, or small-scale or large-scale fighting (coded numerically 1 through 5).75The categorization was done through historical research utilizing both the MID and ICB data sets as well as the Fordham 1998 description of events. The Archives of the New York Times were also used as a primary source for what action was announced and when it happened. For the analysis utilizing militarized disputes, I also constructed a measure of costliness based on the hostility level of the dispute and the crisis level; see Chapman and Reiter 2004. This measure (see below) does not rely on historical research, reducing the potential for measurement bias. The results were substantively identical.

Additionally, I code divided government whenever the opposition party has a majority in either the U.S. House of Representatives or the Senate. I include three dummy variables to measure the political insecurity of an incumbent. The first takes on nonzero values during a presidential election year. The second measures when the president's approval is below 52 percent and thus the incumbent is politically weak. The third variable is coded as 1 for three large-scale presidential scandals—Watergate, the Iran-Contra affair, and the Lewinsky investigation—and 0 otherwise. Finally, a dummy variable measuring whether term limits are in effect for a president is calculated (1 = lame duck, 0 otherwise).76

Scandal timing coded as in Baum 2002.

The last two informational variables measure the change in information laws in the United States and the trust in government. In the United States, significant changes in freedom of information laws occurred in 1966 and 1974. The Freedom of Information Act was passed and signed into law in 1966. The law was strengthened, fees and response times regulated, exemptions narrowed, and a review process initiated in 1974. I code a dummy variable equal to 1 after the year 1974 to measure these significant changes in information laws. While the 1966 law created the infrastructure for post hoc information revelation, the use of the Freedom of Information Act only significantly rose after the 1974 changes.77

Changes in 1966 were not statistically significant when tested empirically.

I code the variable equal to the index in the past election for nonelection years. Question wording and data are available from 〈www.umich.edu/∼nes〉.

I use several research strategies to explore the plausibility of the informational model. In all models presented below, the dependent variables are defined as the change in Gallup polls on presidential approval pre- and postrally events from 1950 to 1998.79

The data are coded in accordance with the research design in Baum 2002 and updated for the post–9/11 period using the Roper Center database (for approval scores).

These control variables are suggested by the patriotism argument (salience), the revised-patriotism argument (foreign policy restraint goal), opposition criticism (the opposition-criticism hypothesis), and previous investigations of presidential approval (inflation and unemployment, see Baum 2002).

See Jentelson 1992.

This data was taken from the Archives of the New York Times. The relevant dates were found in Jentelson 1992 and Baum 2002.

See Brody 1991. Criticism of the president is measured using the scaled IDEA Event Data described above.

See Baum 2002.

Summary statistics for variables used in the analysis

I carry out a number of robustness checks to probe the possibility that my findings are a product of unmeasured dynamics, selection bias, or endogeneity.86

See Appendix 2.

I control for the dynamic nature of presidential approval by diagnosing the series using Box-Jenkins methods. The polls are taken at irregular intervals. I use the sequence of the polls to diagnose autocorrelation. An AR(2) model produced white noise residuals. I also control for ceiling effects by including a lagged approval level variable. Presidents with very high levels of approval are less likely to have large rallies because approval is bounded at 100. I report one-tailed hypothesis tests as all expectations are directional. In addition, I also replicated the in-sample findings using MID data taken from Chapman and Reiter 2004 with a different indicator of signals and found substantively identical results.

After reporting the in-sample findings, I use the pre-1998 model to generate predictions for several potential rallies for the post–9/11 time period. I then explore whether the informational theory variables provide more accurate out-of-sample predictions than either the patriotism or opposition-criticism models. The forecasting predictions are especially useful for probing the external validity of the informational model.

Results

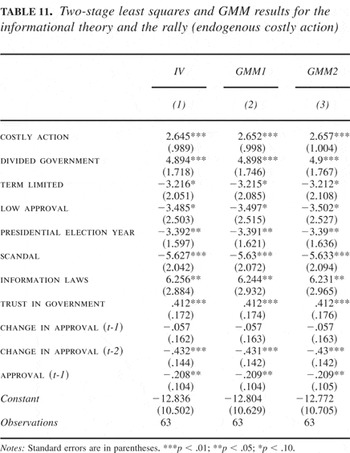

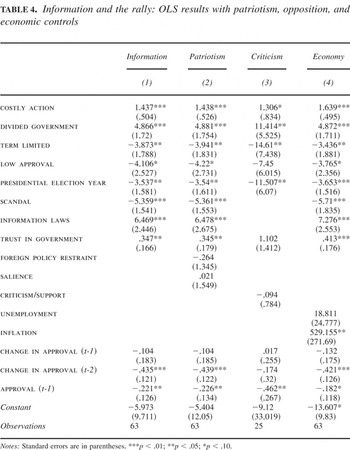

The findings robustly support the informational theory's predictions for the variation in rally size. Table 4 includes results from ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models, with Model 1 representing the informational perspective. In this model—column (1)—each of the informational coefficients are in the predicted direction and statistically significant at or below the .10 level. While the statistical significance of the coefficient is supportive of the theory, the true quantity of interest is the predicted size of the rally. In all cases the informational effects can be interpreted as politically meaningful.88

The definition of a politically meaningful effect is in many ways in the eyes of the beholder. Previous research has appeared to use 3 percent as an implicit cutoff, with politically meaningful rallies needing to exceed that threshold. As noted by Baker and Oneal 2001, since ten out of the fifteen presidential elections since 1948 have been decided by 10 percent or less, even small changes may be substantively meaningful.

Information and the rally: OLS results with patriotism, opposition, and economic controls

The findings on political insecurity and government trust are also consistent with the informational signaling story. Ongoing scandals, low approval, and an upcoming election are expected to decrease the size of a rally by 5.4 percent, 4.1 percent, and 3.5 percent respectively. Being term-limited results in a predicted drop in the rally by approximately 3.8 percent. From the information perspective, under these circumstances, the public either has a reason to expect that a leader may be privately benefiting from foreign policy action (diversion from weak approval or scandal) or a reduced confidence that information will be available or useful in punishing a leader for private-interest action (upcoming election or active term limits). Conversely, a 10-point rise in trust in government is estimated to increase the rally by almost 3.5 percent. The greater the proportion of the country that views the government as self-policing and the lower the proportion of the public that views the government as corrupt, the larger the predicted rally.

These results are consistent when the potentially confounding effects of foreign policy restraint (FPR), salience, opposition support and criticism, and unemployment and inflation are modeled in columns (2) to (4) of Table 4. Only one of these other variables is significant (inflation) and only the low approval and trust measures lose their statistical significance in the criticism model.89

This most likely occurs because the sample size is significantly reduced. The absolute size of the coefficients actually increases, but less than the size of the uncertainty estimates.

The substantive importance of the informational theory can be illustrated by simulating the predicted size of the rally for various different scenarios from the statistical model. Several of these predictions are presented in Figure 5. The two sets of bars represent the 95 percent confidence intervals around the predicted rally size for credible versus less credible circumstances as suggested by the informational theory. Credible circumstances involve an incumbent with strong approval (>52 percent) operaing under divided government circumstances, without relevant term limits and where trust is high (46 percent), outside of an election year. Less credible circumstances involve a leader with weak approval (<52 percent), operating in an election year with a unified government and low trust in government (37 percent).90

For this simulation both the credible and less credible scenarios do not involve scandals and I set the information law variable equal to 1.

The effect of costly action and credibility (strong approval, divided government, nonelection year, no lame duck) on rally size

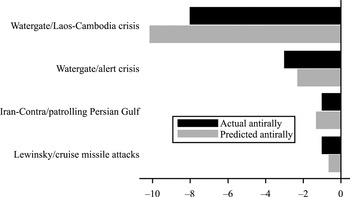

Similarly, Figure 6 illustrates the actual and predicted rallies for four crises that occurred during presidential scandals. In 1973, during the unfolding of the Watergate scandal, the Nixon administration dealt with two international crises: a nuclear alert in reaction to Soviet threats in the Middle East, and also heightened tension in Laos and Cambodia. Because of the ongoing scandal, the informational model as estimated in column (1) of Table 4 predicts that approval would fall by about 10 points (with a 95 percent confidence interval (CI) of −15.2, −5.2), while the actual decline in approval was 8 points. Similarly, the model predicts that Nixon would lose around 2 points (with a 95 percent CI of −6.8, 2.2) during the Middle East alert crisis in October of 1973, where the actual negative/antirally was 3 points. In both of these cases, the estimated model predicts that Nixon could not credibly signal to the public that foreign policy action was in the national interest, rather than in his private interest. In fact, British Prime Minister Anthony Heath suggested in private notes that Nixon might use the Middle East alert crisis to divert attention from his domestic troubles.91

See New York Times, 2 January 2004, A4.

Four predicted and actual rallies during presidential scandals

One can contrast these insignificant and negative rallies with more credible situations, as defined by the informational model. For example, the informational model would predict that George H. W. Bush was in a strong position to mobilize support for the first Gulf War. First, he was neither bogged down in a scandal nor had low approval ratings. Second, he was operating under circumstances of divided government, after the 1974 strengthening of the freedom of information laws, and outside of a presidential election campaign. The empirical model predicts that Bush would receive a rally of 12 points (with a 95 percent CI of 7,17) in this case, while the actual rally was 19.

Summary of In-sample Findings

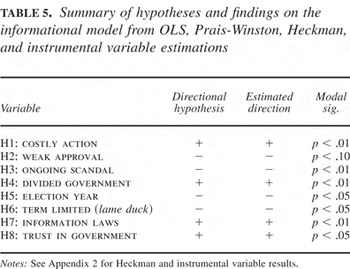

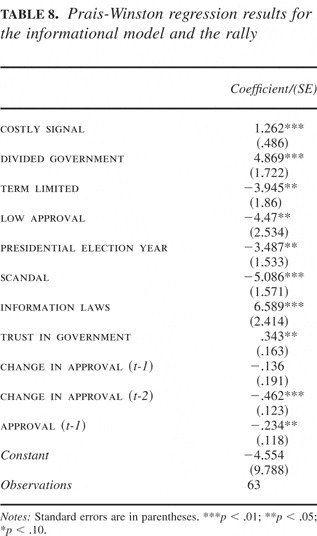

The findings from a battery of estimation strategies presented here and in Appendix 2, including OLS, Prais-Winston, Heckman, and instrumental variable models,92

All non-OLS findings are reported in Appendix 2.

I denote the modal significance as the most frequently reported significance level for the relevant variable.

Summary of hypotheses and findings on the informational model from OLS, Prais-Winston, Heckman, and instrumental variable estimations

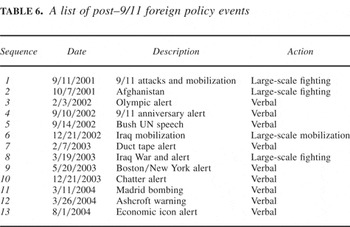

Forecasting

What does the informational model, fit to 1950–98 data, have to say about post–9/11 events? The previous results were all based on in-sample hypothesis tests. An alternative testing strategy is to compare the in-sample predictions with out-of-sample data. This forecasting procedure allows one to probe the external validity of the previous findings and the informational theory. For example, to the extent that the previous results were a product of estimation or specification bias, they should forecast poorly out of sample. Toward this end, I collected data on potential rally events in the post–9/11 period in the United States. This yielded fifteen events, some of which occurred in close temporal proximity. The thirteen events with pre- and postapproval measures are listed in Table 6.94

Gallup did not take polls between 11 September 2001 and the large-scale mobilization for the war in Afghanistan (19 September 2001) and between the Iraq orange alert and the beginning of Operation Iraqi Freedom.

Ignoring the 9/11 rally does not change the substantive conclusions.

Further, directives came from the executive branch, as in a military operation. Also, the media treated the event as a military attack, with headlines reading, “Attack on America,” or some variation.

A list of post–9/11 foreign policy events

This forecasting approach uniquely allows the external validity of the findings to be explored. Forecasting in the post–9/11 world could also be considered a tough test for the theory, since many commentators97

See Mueller 2003 for a skeptical view of the “step function” interpretation.

To represent the informational theory, I generate predictions from the first model in Table 4. I compare these results to two null/no-rally models, where the effects of all informational variables are zero. The first null model predicts that the rally will be zero regardless of previous approval or the costly signal. The second, dynamic null model predicts that the average rally will be zero, but that the previous changes in approval will predict present changes.98

The dynamic null model is computed as in Table 4, but with the informational variables assumed to be zero and the equilibrium (constant) constrained to zero.

The forecasting performance only weakens for the patriotism model when the ex ante mean rally is used.

Specifically, I use the model with the outliers removed (βCrit = 4.86). I then coded whether the opposition party agreed with(1.86), opposed(−1.83), or was of mixed opinion about the rally actions(0).

There are several methods to compare the accuracy of forecasts. These include the root mean squared error (RMSE), the mean absolute deviation (MAD), and Theil's U. The RMSE criterion penalizes models that make big mistakes, while MAD weights errors in proportion to their absolute error. Theil's U is similar to RMSE because it standardizes the mean sum of squared errors by the variation in y.

Regardless of the measure chosen, the informational model provides more accurate predictions than either the mean-rally, opposition-criticism, or null/no-rally models. As illustrated in Table 7, the informational predictions perform the best in the post–9/11 world, producing the lowest RMSE, MAD, and Theil's U. Figure 7 presents the results from the informational model beside the actual measured rallies for each event. Not surprisingly, the costly-signaling predictions substantially underestimate the 9/11 rally. In reality, not only was 9/11 a large-scale event, but it was a mass-observed event. In a unique sense, the event was witnessed, live on television, by millions of viewers. The possibility that the resulting mobilization was noncredible (p in the signaling model) was minuscule.101

Almost 80 million people tuned into news stations on 9/11, approximately 40 percent of the U.S. population; see Althaus 2002.

Adding information on foreign policy restraint and salience decreased the accuracy of the patriotism forecasts.

Forecast error comparisons for the informational, patriotism, opposition-criticism, and insignificant-rally models on the post–9/11 events

Post–9/11 event-by-event forecasting fit for the informational model (actual and predicted)

Conclusion

In this article, I have offered a theory of the rally effect that nests patriotic preferences within a signaling environment. The empirical tests of eight specific hypotheses derived from the informational perspective were highly supportive of the model. Further, the forecasting results for the informational theory suggest that an understanding of the variance in the credibility of foreign policy signals can help researchers predict the size of foreign policy rallies over time. Certain specific and identifiable operational, institutional, and political factors increase the probability of post hoc verification and conditional punishment and create an incentive structure that aids leaders in generating support for their foreign policies. Since there are disincentives for selfish policy, citizens can be more confident that international actions are in the public interest.

The informational theory has implications for a broad range of research in international relations, including the monadic democratic peace and diversionary theory. Instead of viewing democracies as institutionally constant, I have argued that different actions and circumstances will carry varying probabilities of verification and conditional punishment and that distinct constellations of institutional, political and operational factors influence the calculations of both leaders and citizens. Therefore, there is the potential to examine how democracies differ from each other and from nondemocracies based on these retrospective criteria. The signaling model suggests that previous research on the monadic democratic peace is incomplete. First, measures of institutions based on the mere presence or absence of elections and opposition parties ignore the temporal properties of national security classification and diffusion. Due to increased secrecy and classification, democratic accountability on foreign affairs is not constant over time and space. Second, the signaling theory does not suggest that states (such as the United States) with active post hoc verification and conditional punishment institutions will never use force, as the conventional research on the monadic democratic peace investigates. On the contrary, force is likely if it is perceived to serve the public interest. What is predicted is that those states able to credibly signal public interest though foreign policy action should become involved in different types of conflicts as compared to other types of states. One specific hypothesis would be that conflicts launched on territory with easily lootable resources should be comparatively rare in national security–accountable regimes.

Additionally, the informational model suggests that the presence of retrospective foreign policy institutions, when active, reduces the prevalence of diversionary conflict involving large-scale violence.103

This argument runs counter to suggestions made by Gelpi104See Gelpi 1997.

Mitchell and Prins 2004.

With verification depending on the costs of the action and political factors.

A more fruitful avenue for future work would be to analyze the longitudinal and cross-sectional changes in these information-diffusion mechanisms. Even relatively small changes—for example, allowing former executives the choice to keep information secret in perpetuity—could alter the balance between secrecy and accountability.107

U.S. President George W. Bush has signed several executive orders that may move in this direction. Specifically, EO 13233 amending the Presidential Records Act and EO 13292 amending the classification scheme for government information are germane. Jointly, these changes may decrease the probability of post hoc verification in the United States, giving both the current and former presidents the ability to block information diffusion.

Ultimately, this work and other analyses of the rally are important not just for the spike in approval that they represent, but for the triangular theoretical linkages between publics, executives, and international relations that they imply and test. An information-based rally, rather than a reflexive one, challenges the traditional realist supposition that democratic states are disadvantaged in the competitive arena of international anarchy. Kissinger,108

See Kissinger 1995.

Appendix 1: Formal Proofs

Here I explore two perfect Bayesian equilibria, given the constraints:

Proposition 1. When β − ε > 0, at the last stage of the game, P plays S if:

I define:

When p < ħ,Aβ will play α if:

As long as this is true, Aβ plays α.

Similarly, when p < ħ, Aθ will play α if:

This is true by definition. Using Bayes's rule, P's posterior beliefs remain unchanged:

(α,α,S) describes a perfect Bayesian equilibrium when p < ħ, and β − ε > 0. Aβ chooses α, Aθ chooses α, and P chooses support.

When p > ħ, P's best strategy is to oppose. Knowing that, Aβ will only play α if:

Since this is never true by definition, Aβ plays ¬α.

Similarly, Aθ will only play α if:

Again, this cannot be true.

Notice that p > ħ can only be true if |τp| < |γ|. If the cost of opposition was greater than the cost of α, then ħ > 1.

Using Bayes's rule, P's posterior beliefs remain unchanged:

(¬α,¬α,O) describes a perfect Bayesian equilibrium when p > ħ, and β − ε > 0. Aβ chooses α, Aθ chooses α, and P chooses support.

Using the above constraints, a separating equilibrium (¬α,α,S) does not exist. If it is in P's interest to play S, both θ and β situations will lead to α, because:

as described above.

Proposition 2. When τa < β − ε < 0, I still use the cut point ħ to differentiate P's choice.

If p < ħ, P's best strategy would be to support. However, now Aβ and Aθ have differing incentives.

Aβ will play α if:

which is now false. Therefore, Aβ will play ¬α.

Aθ will play α if:

which is always true. Therefore, Aθ will play α. This new information allows P to update her posterior belief, with

Thus, a separating equilibrium is expressed by the triple (¬α,α,S), when β − ε < τa < 0 and |τp| < |γ|.

Appendix 2: Robustness Analysis

In this Appendix I present several robustness checks that were carried out to further probe the plausibility of the statistical results reported above. I examine the exogeneity of the costly action measure,110

I also investigated the linearity of the costly-action measure. Neither a log-linear nor quadratic model provided a statistically superior fit to the data.

Autocorrelated Errors

In the previous models, any unmodeled correlation within the residuals would bias the resulting inferences. A Prais-Winston regression framework allows one to model a specific form of residual autocorrelation, where ρPrais measures the size of the correlation between the previous residual and today's residual.111

ρPrais is computed from a first-stage GLS estimate.

Prais-Winston regression results for the informational model and the rally

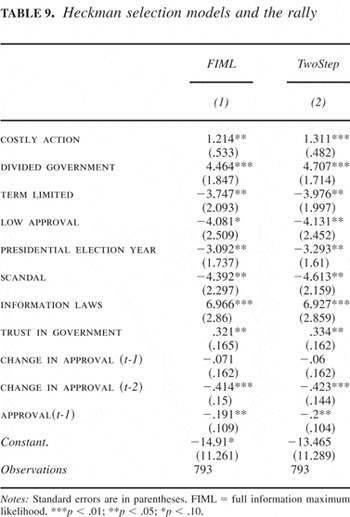

Selection Bias

As a second robustness check, I expand the 1950 to 1998 analysis to include all presidential polls, even those that do not include rally events. This increases the number of observations from 63 to 793 (in the first stage). I then use a Heckman selection model to investigate whether the rally-event findings are an artifact of selection bias. For example, it is possible that some unobserved factors both make a rally event more likely and lead to a larger rally. If these unobserved factors are correlated with the variables of interest, an analysis ignoring the selection of rally events might lead to biased inferences.112

The instruments used to identify the selection equation are explained below and are the same as those used to identify the rally–costly-signal system of equations. For a description of the model, see Heckman 1976.

To create the results in Table 9, I model both the decision to participate in a foreign policy event (first stage, not presented) and the resulting rally (second stage). This is done by including all polls of presidential approval in the first-stage equation, along with the three instrumental variables described below. I present both the full information maximum likelihood estimates (FIML) as well as the two-step estimates for the rally stage. The statistical significance, direction, and magnitude of the coefficients remain consistent. Costly action, divided government, freedom of information laws, and trust in government increase the expected rally, while active term limits, weak approval, scandals, and presidential election years decrease the expected size of the rally. In the Heckman FIML model, the difference between a rally that involves large-scale fighting under conditions of divided government and a popular executive113

Defined as approval greater than 52 percent. In this case, I set approval to 55 percent.

Where estimates from the OLS regression and second-stage Heckman model are compared to each other.

All variables except the costly-signal measure are included in the first-stage model. It is by definition zero when a rally event is not present.

Heckman selection models and the rally

Endogenous Signals

In a final battery of tests I explore the possibility that the costly-action measure is endogenous to the rally. In the signaling model presented above, the same factors that lead to action make a rally more likely. For example, when the public perceives a θ world as highly likely (high p), both action and support are likely. The literature on diversionary conflict116

also suggests a leader is likely to choose a specific foreign policy action only to gain a popularity boost or only in situations where a rally is inevitable. If leaders are choosing costly action only when support is forthcoming for other reasons, the previous models have reversed the empirical relationship. It is not costly actions that cause support, but expected support that is causing costly action.117This implies that the residuals are correlated with the independent variable. Under these conditions, the estimated coefficients represent an unappealing mix of the correlation between x and y and y and the residuals. I should point out that all single-equation tests of the rally effect suffer from this potential inferential pitfall.

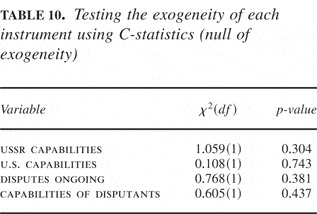

The most direct way of dealing with endogeneity is to explicitly model both the process of presidential support and the costliness of the action. To do this, one must identify instruments that are correlated with the costliness of the signal sent, but not with presidential support. There are four steps in this process. These involve locating instruments, testing whether they are correlated with the potentially endogenous variable, testing whether they are uncorrelated with the residual from the second stage, and finally testing whether the single-equation OLS estimates are biased.

To identify instruments, I combine my discussion of temporary information asymmetries between leaders and the public with work on U.S. uses of force by Gowa and Fordham.118

What I seek to uncover are sources of information that affect leadership actions but do not influence the rally intensity. Gowa and Fordham both suggest that international events and capabilities drive U.S. decisions to use force.119Gowa and Fordham disagree over whether domestic variables such as divided government drive U.S. action. My model does not rely on Gowa's implied zero-restrictions. One operational change I make to these models is to measure threats around the world using disputes rather than wars and to include a capability measure of the states involved in these conflicts. This is needed because of the shorter time frame of the data here and the low frequency of wars.

The multiyear efforts by the Correlates of War (COW) project to code military-relevant capabilities data historically is a testament to the immediate public opacity of much of this information. However, this information does eventually become available both in the form of publicly available data and government estimates through information release policies.

Admittedly, the United States being a hegemonic power for much of this time complicates the exogeneity of international events. However, all empirical tests of this proposition support the usefulness of the instruments. If this analysis was replicated out of the U.S. context, regional crises could be included instead of all crises, and the capabilities of territorial or positional rivals included as threats.

Several different indicators of Soviet capabilities where also investigated. None of these changes altered the results or proved to be superior instruments.

The capabilities, dispute, and military personnel information comes from the COW project; see Jones, Bremer, and Singer 1996. I use the military personnel of those involved in international events, not including those that the United States is already actively involved in, in the previous thirty days.

Many hot spots around the world will flare regardless of U.S. presidential approval scores. Further, the end of the Cold War decreased the costs of U.S. action since the USSR was no longer capable of deterring U.S. intervention. Finally, the greater the military capabilities of the United States, the greater the freedom of foreign policy action.

These potential instruments should predict the costliness of a presidential action and be exogenous to the rally. Specifically, I use the log of the proportion of capabilities controlled by the USSR during the Cold War,125

As measured by the COW project.

Again, from the COW project.

Next, I turn to tests of the correlation between these instruments and costly action. Empirically, useful instruments will be jointly statistically significant and explain a large portion of the variance in the potential endogenous regressor. This can be measured using an F-test that the instruments are all simultaneously zero and r2 measures from the first stage. In this case, I reject the null hypothesis that all of the coefficients measuring the effect of the instruments on costly action are 0 (p ≤ 0.01). Additionally, the uncentered r2 is .88 and the partial r2 is .25. The partial r2 is the most useful statistic because it only measures the amount of variance explained by the instruments, rather than mixing information on the instruments with the other exogenous variables. In both of these cases (the F-test and partial r2), the results suggest that the instruments satisfy my first condition, a significant and meaningful correlation with costly action. Substantively, this implies that hot international conditions and a weak rival make action more likely.

I also must show that the instruments are uncorrelated with the residuals from the second-stage rally equation. This implies that the instruments are exogenous to the rally. The exogeneity of the instruments can be tested both together and then separately for each of the variables. For this purpose of joint testing I report the Sargan overidentification statistic, which tests the null hypothesis that the correlation between all of the instruments and the second-stage residuals is zero. The Sargan statistic is equal to the uncentered r2 × N, where the r2 is derived from running an auxiliary regression of the residuals from the instrumental variable model on the instruments.127

The statistic is distributed χ2. The similar Hansen-J statistic and Bassman tests report substantively identical results.

Testing the exogeneity of each instrument using C-statistics (null of exogeneity)

Finally, I can use these instruments to estimate the effect of costly action on the rally in a two-stage framework. What I am looking for is evidence that my previously reported OLS results were positively biased due to endogeneity. However, when examining the endogeneity of the costly action in an instrumental variable framework, the post hoc costliness of an action remains an important predictor of presidential approval. The two-stage least square (2SLS) and generalized method of moment (GMM) results are presented in Table 11. These methods attempt to model the simultaneous relationship between an executive choosing a signal and the resulting rally. Models 2 and 3 include the computation of Newey-West autocorrelation consistent estimates with 2- and 3-lagged errors respectively. The most conservative model predicts that large-scale fighting increases immediate presidential support by 9 percent more than verbal events, all else equal. The costly-action coefficient is consistently statistically significant at the .05 level. The consistency between the 2SLS, GMM and OLS models is confirmed by the insignificant Wu-Hausman F and Durbin-Wu-Hausman χ2 tests of endogeneity (F(1,50) = 1.81, p = 0.185; χ2(1) = 2.19, p = 0.138). These statistics measure whether significant bias can be detected in the OLS estimates as compared to the 2SLS model. The failure to reject the null of insignificant bias suggests that the reported OLS findings are consistent.128

Note that the failure to reject exogeneity is conditional on the model. While the signaling model suggested endogeneity it also specified several variables, which were included in the model, that should have controlled for much of this correlation between the action and the error term. To probe this idea further, I ran a simple bivariate two-stage model where the rally was a function of costly action. The same instruments were retained. In this case, the costliness of the action did appear to be endogenous, with a significant Wu-Hausman F-test (F(1,57 = 2.81) p = 0.098), at the .10 level. Therefore, it is only when one controls for the other seven informational variables, and removes from the error term the factors that make both action and the rally more likely, that the costly-action measure is not biased in an OLS framework.

Two-stage least squares and GMM results for the informational theory and the rally (endogenous costly action)