Introduction

Exposures in the prenatal and early developmental periods are thought to affect neural development and have been identified as risk factors for a range of psychiatric disorders (Nosarti et al., Reference Nosarti, Reichenberg, Murray, Cnattingius, Lambe, Yin and Hultman2012). Among the most severe and fatal psychiatric illnesses (Chesney, Goodwin, & Fazel, Reference Chesney, Goodwin and Fazel2014), eating disorders (EDs) generally occur early in life (Zerwas et al., Reference Zerwas, Larsen, Petersen, Thornton, Mortensen and Bulik2015), which points investigations of potential environmental risks towards a focus on factors operating early in life. Many psychiatric disorders appear to be influenced by pre- and perinatal factors, whereas the evidence for similar patterns in EDs is contradictory.

Twin-based heritability estimates range from 48% to 74% for anorexia nervosa (AN) (Bulik et al., Reference Bulik, Sullivan, Tozzi, Furberg, Lichtenstein and Pedersen2006, Reference Bulik, Thornton, Root, Pisetsky, Lichtenstein and Pedersen2010; Dellava, Thornton, Lichtenstein, Pedersen, & Bulik, Reference Dellava, Thornton, Lichtenstein, Pedersen and Bulik2011; Kipman, Gorwood, Mouren-Simeoni, & Ades, Reference Kipman, Gorwood, Mouren-Simeoni and Ades1999; Klump, Miller, Keel, McGue, & Iacono, Reference Klump, Miller, Keel, McGue and Iacono2001; Kortegaard, Hoerder, Joergensen, Gillberg, & Kyvik, Reference Kortegaard, Hoerder, Joergensen, Gillberg and Kyvik2001; Wade, Bulik, Neale, & Kendler, Reference Wade, Bulik, Neale and Kendler2000), and 55% to 62% for bulimia nervosa (BN) (Bulik, Sullivan, & Kendler, Reference Bulik, Sullivan and Kendler1998; Bulik et al., Reference Bulik, Thornton, Root, Pisetsky, Lichtenstein and Pedersen2010; Kortegaard et al., Reference Kortegaard, Hoerder, Joergensen, Gillberg and Kyvik2001; Trace et al., Reference Trace, Thornton, Baker, Root, Janson, Lichtenstein and Bulik2013), whereas single-nucleotide polymorphism-based heritability of AN has been estimated at 20% (Duncan et al., Reference Duncan, Yilmaz, Gaspar, Walters, Goldstein, Anttila and Bulik2017). That genetic variation seems to explain some, but not all, of the variation in EDs encourages exploration of other factors in ED etiology, including the associations between in utero and perinatal environments with ED development.

Two studies reported that higher paternal age was associated with increased risk of AN and EDs in general (Javaras et al., Reference Javaras, Rickert, Thornton, Peat, Baker, Birgegard and D'Onofrio2017; McGrath et al., Reference McGrath, Petersen, Agerbo, Mors, Mortensen and Pedersen2014).

A review and meta-analysis investigated obstetric factors and ED risk (Krug, Taborelli, Sallis, Treasure, & Micali, Reference Krug, Taborelli, Sallis, Treasure and Micali2013). Of the six studies eligible for meta-analysis, five reported non-significant associations for vaginal instrumental delivery and prematurity in AN. Another systematic review reported that among numerous factors that have been associated with ED risk, only prematurity had been replicated across ED samples and only for AN (Raevuori, Linna, & Keski-Rahkonen, Reference Raevuori, Linna and Keski-Rahkonen2014).

Two reviews on BN found no replicated perinatal risk factors, partly due to a few studies and incomparable exposure measures (Krug et al., Reference Krug, Taborelli, Sallis, Treasure and Micali2013; Raevuori et al., Reference Raevuori, Linna and Keski-Rahkonen2014). A birth cohort study on self-reported lifetime BN did not find any associations with birth characteristics (Nicholls, Statham, Costa, Micali, & Viner, Reference Nicholls, Statham, Costa, Micali and Viner2016). To our knowledge, no studies have specifically evaluated the associations between pre- or perinatal factors and eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS).

Thus, the conflicting findings across samples strongly encourage large-scale studies to provide more definitive results. The Danish national registers include information on the entire population, free of recall and selection bias, and provide unique opportunities to study even rare conditions. This study investigates and compares associations among a wide range of prenatal and perinatal factors and the risk of AN, BN, EDNOS, and, for comparison, other psychiatric disorders, in a large nationwide sample of both males and females.

Methods

Study population

All Danish citizens are assigned a unique identification number which is used as a personal identifier in all national registers and makes the accurate linkage between registers possible (Pedersen, Reference Pedersen2011). Using the nationwide Danish Civil Registration System (Pedersen, Reference Pedersen2011), we identified all individuals born in Denmark between 1 January 1989 and 31 December 2010, to parents also born in Denmark. Individuals who died or emigrated before their 6th birthday were excluded from the study.

Eating disorders

All contacts to Danish hospitals are recorded in the Danish National Patient Register (NPR) (Lynge, Sandegaard, & Rebolj, Reference Lynge, Sandegaard and Rebolj2011) and the Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register (Mors, Perto, & Mortensen, Reference Mors, Perto and Mortensen2011). Inpatient contacts have been registered in the NPR since 1977 and in the Psychiatric Central Research Register since 1969. Both registers have included outpatient contacts since 1995. The International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10) has been the diagnostic system used in Denmark since January 1994. Prior to that, the International Classification of Diseases, 8th revision (ICD-8) was used.

The outcomes of interest were ICD-10 diagnoses of AN (F50.0, F50.1), BN (F50.2, F50.3), and EDNOS (F50.8, F50.9). For comparison, we also included diagnoses of depressive disorders (F32, F33), anxiety disorders (F40, F41), and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) (F42). These disorders were chosen due to their symptomatic overlap with EDs.

Date of onset was defined as the admission date of the first occurrence of an in- or outpatient contact recorded in the NPR or the Psychiatric Central Research Register with each diagnosis of interest, irrespective of other previously received diagnoses. Only contacts after age 6 were included to reduce diagnostic misclassification of, for example, feeding disorders in infancy and childhood.

Prenatal and perinatal factors

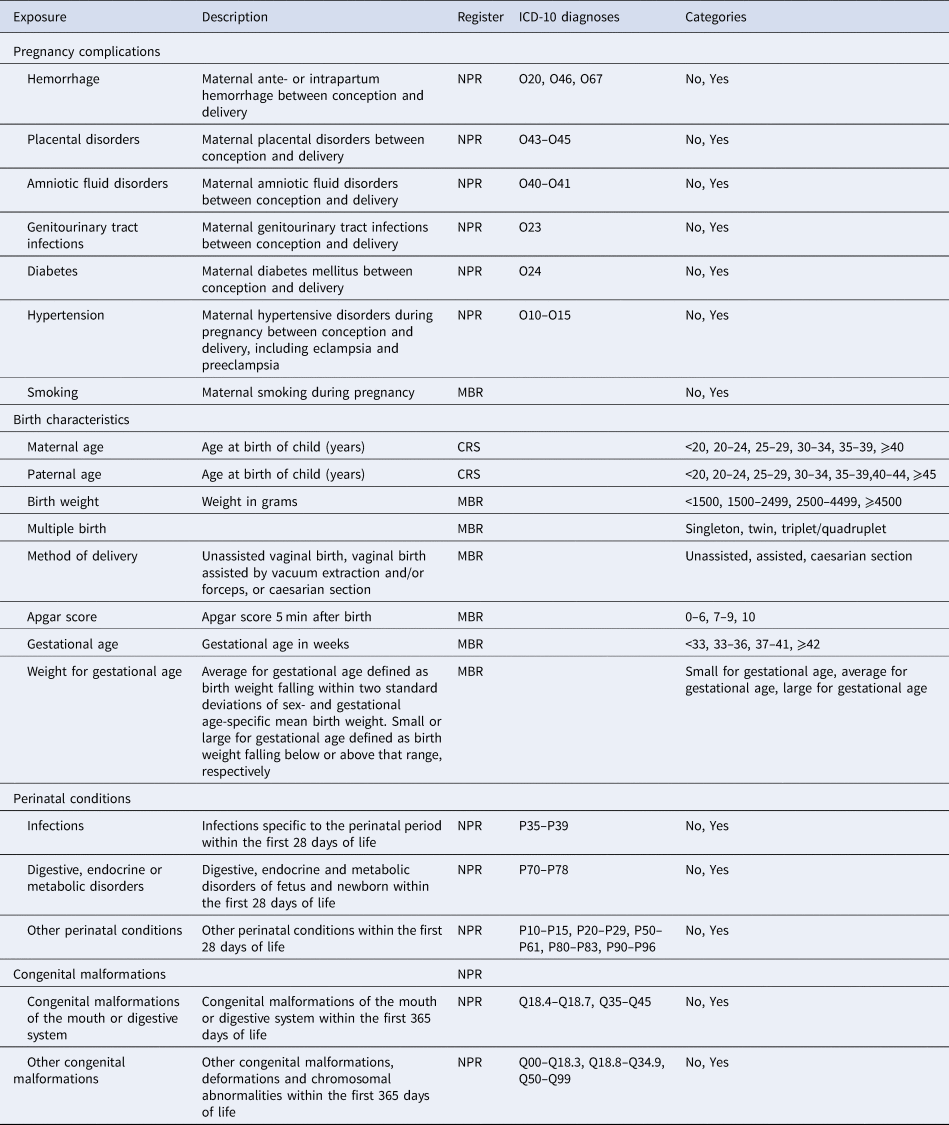

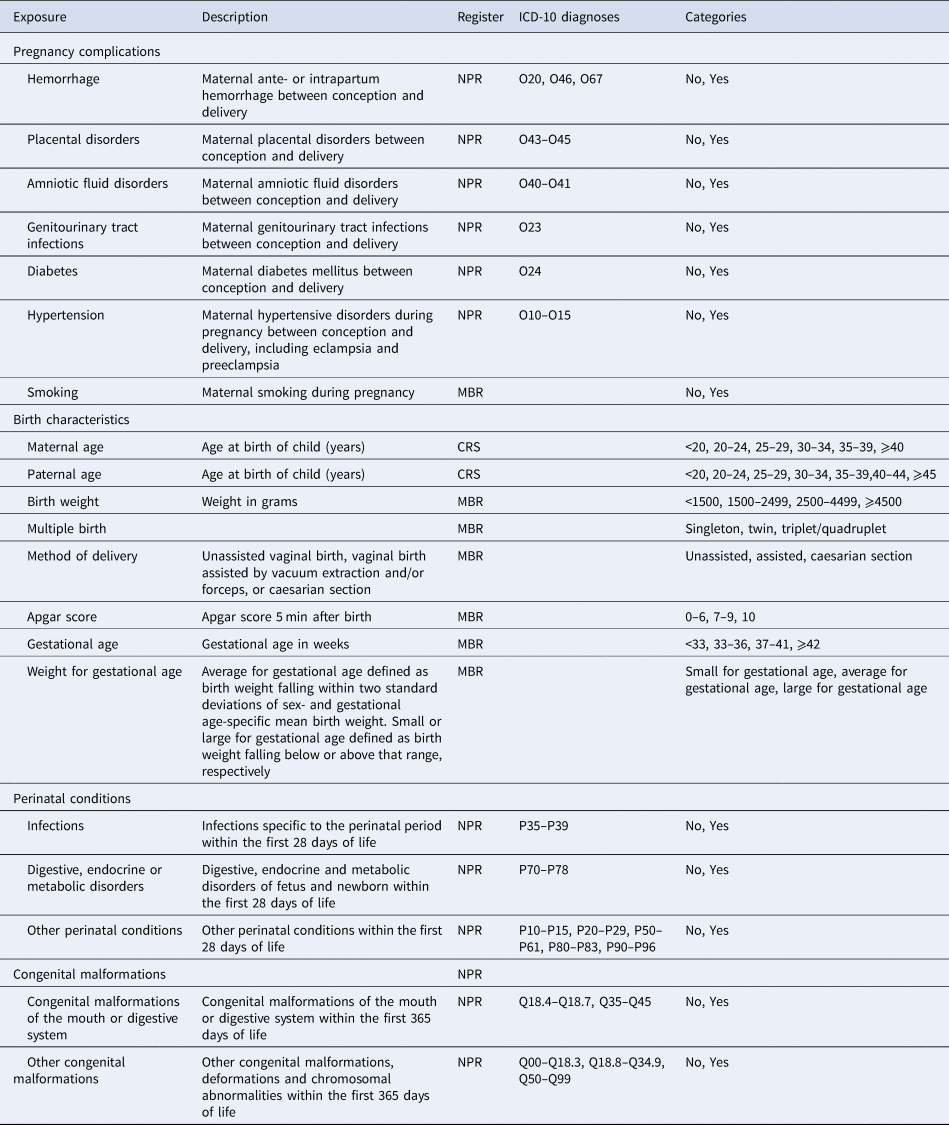

Birth characteristics and pre- and perinatal factors were defined using information from various registers. Details on definitions and categories are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Definitions of pre- and perinatal factors

NPR, National Patient Register; MBR, Medical Birth Register; CRS, Civil Registration System.

Pregnancy complications were defined by identifying maternal diagnoses of hemorrhage, placental disorders, amniotic fluid disorders, genitourinary tract infections, diabetes, and hypertension in the NPR between conception and birth. Date of conception was estimated using registered gestational age in the Danish Medical Birth Register (Bliddal, Broe, Pottegard, Olsen, & Langhoff-Roos, Reference Bliddal, Broe, Pottegard, Olsen and Langhoff-Roos2018) or, if unknown, assumed to be 280 days prior to birth. Information on smoking during pregnancy was obtained from the Medical Birth Register and has been recorded from 1991 onwards.

Parental ages at the birth of the child were calculated by subtracting the date of birth of the child from the parent's date of birth. Exposures related to the birth came from the Medical Birth Register. They included information on the following: method of delivery, gestational age, multiple births, Apgar score, birth weight, and weight for gestational age [categorized as defined by Marsal et al. (Reference Marsal, Persson, Larsen, Lilja, Selbing and Sultan1996)].

Perinatal conditions and congenital malformations were defined as contacts to a hospital, recorded in the NPR. Perinatal conditions diagnosed within the first 28 days of life were included and were categorized as diagnoses of infections, digestive, endocrine and metabolic disorders, and other perinatal conditions (e.g. respiratory and cardiovascular disorders). Congenital malformations diagnosed within the first year were categorized as congenital malformations of the mouth or digestive system, and other congenital malformations.

Pregnancy conditions, perinatal conditions, and congenital malformations were defined using only ICD-10 diagnostic codes and therefore were available only for children born 1995 or later for pregnancy conditions and 1994 or later for perinatal conditions and congenital malformations.

Statistical analysis

Follow-up began on the 6th birthday and ended on the date of onset, death, or emigration, or 31 December 2016, whichever came first. Using Cox proportional hazards models, we estimated hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each type of ED. All analyses were adjusted for sex using separate underlying hazard functions, for age as the underlying time in the Cox model, for time-dependent calendar-time (categorized in 5-year intervals starting in 1995), and time-dependent mother's history of any ED (ICD-8 306.50, 306.58, 306.59; ICD-10 F50, with date of onset occurring prior to or during follow-up defined similarly to the outcome diagnoses) in analyses of AN, BN, and EDNOS. In analyses of depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, and OCD, we adjusted for maternal history of the same disorder (depressive disorders: ICD-8 296.09, 296.29, 298.09, 300.39; ICD-10 F32, F33. Anxiety disorders: ICD-8 300.09, 300.29; ICD-10 F40, F41. OCD: ICD-8 300.39; ICD-10 F42). When the sample size in each exposure-outcome strata was adequate, we conducted analogous sex-stratified analyses.

We performed multivariable analyses adjusting birth weight, weight for gestational age, and method of delivery for multiple births, and gestational age-adjusted for genitourinary tract infection during pregnancy. This was done to account for the increased risks of low birth weights and required assistance during birth occurring when delivering multiple babies and for the increased risk of preterm delivery following genitourinary tract infection (Romero, Espinoza, Chaiworapongsa, & Kalache, Reference Romero, Espinoza, Chaiworapongsa and Kalache2002; Verma, Avasthi, & Berry, Reference Verma, Avasthi and Berry2014).

All analyses were performed in Stata version 15 using the ST suite of commands (StataCorp, 2017).

Results

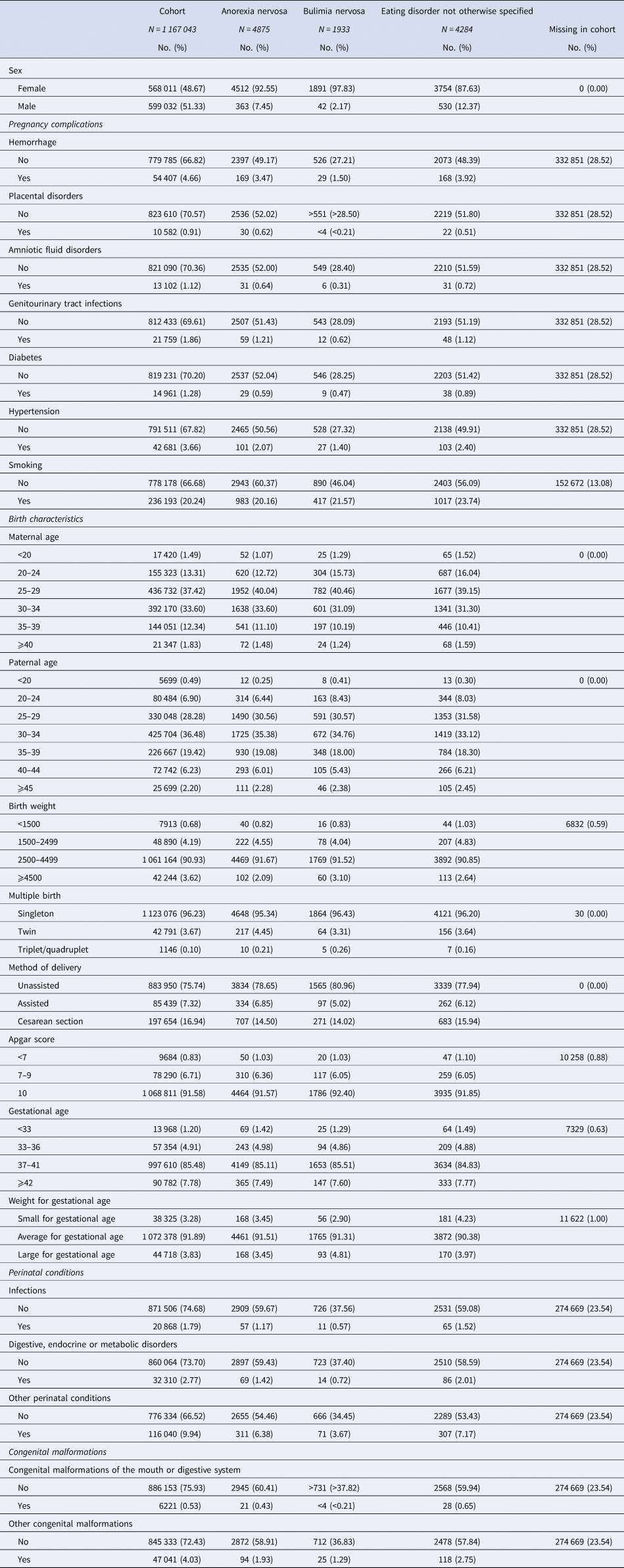

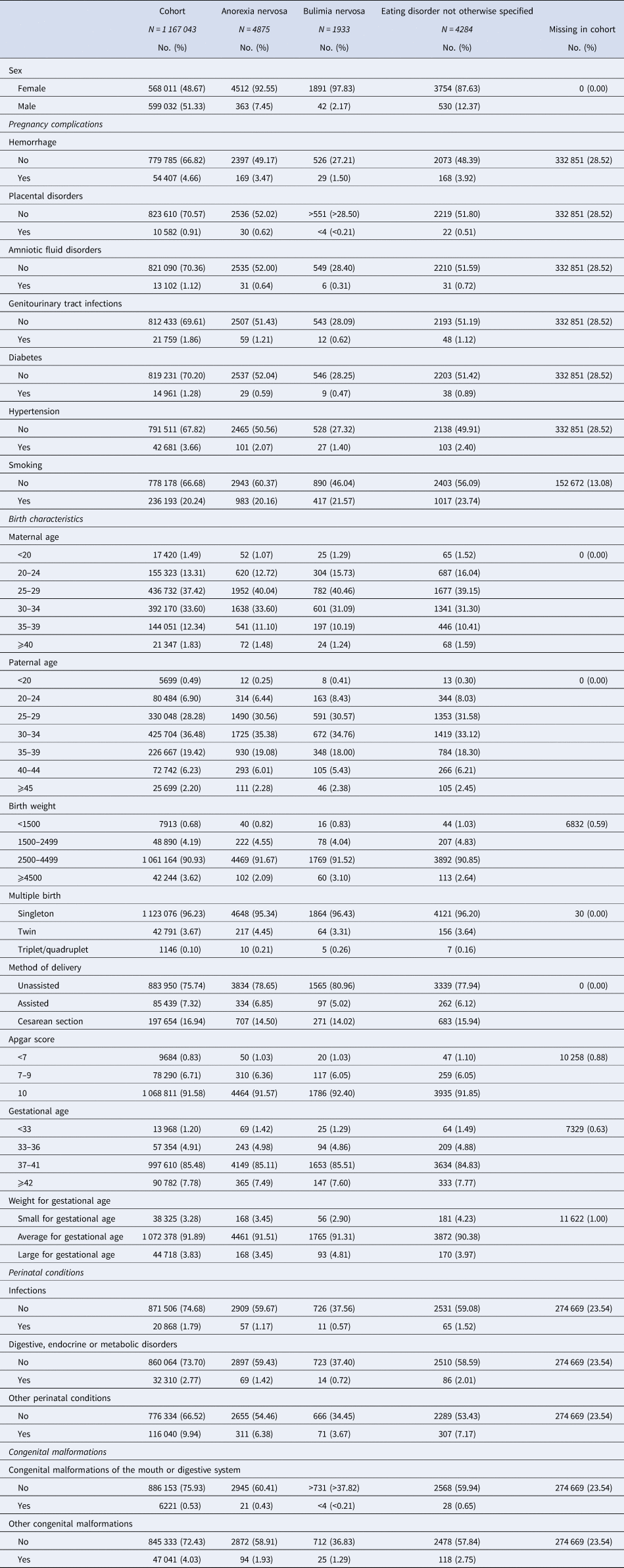

The study population comprised 1 167 043 individuals (48.67% females) and was followed for 13 million person-years. Frequencies for sex and exposures for the study population and for ED groups are presented in Table 2. The diagnostic groups were not mutually exclusive as persons diagnosed with multiple EDs during follow-up were included as cases in each group. A total of 231 individuals were diagnosed with both AN and BN, 1321 individuals with both AN and EDNOS, 361 individuals with both BN and EDNOS, and finally, 169 individuals were diagnosed with all three types of EDs during follow-up.

Table 2. Frequency of sex, pre- and perinatal factors in the cohort and in eating disorder groups

Estimated HRs with 95% CI for associations between pre- and perinatal factors and ED are presented in Table 3. The multivariable analyses with mutual adjustments for selected exposures did very little to change the conclusions and results are not shown. Sex-specific results are presented in online supplementary eTables 1 and 2. For all EDs, most results were driven by females.

Table 3. Estimated hazard ratios of eating disorders after exposure to pre- and perinatal factors

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Results that are statistically significant at α = 0.05 are highlighted in bold.

a Adjusted for sex, age, calendar-time, and history of any maternal eating disorders.

b Not estimated due to few exposed cases.

Equivalent results for the comparison disorders are presented in online supplementary eTables 3 and 4. A total of 20 147 individuals were diagnosed with depressive disorders during follow-up, 15 205 with anxiety disorders, and 7640 with OCD.

Anorexia nervosa

Significantly increased risk of AN was observed for genitourinary tract infection [HR 1.49, 95% CI 1.15–1.93], whereas a significantly decreased risk of AN was observed for smoking [0.83 (0.77–0.89)]. AN risk increased with increasing maternal and paternal ages at birth of child, with significantly decreased risks for parental ages below 25 years. For birth weights, only weights above 4500 g were associated with a decreased risk of AN [0.82 (0.67–0.99)]. Multiple birth was associated with AN risk with increased risk for both twin and triplet/quadruplet births [1.41 (1.23–1.61) and 1.92 (1.03–3.57), respectively] compared to singleton births. Significantly increased risk of AN was observed for caesarean section compared to unassisted vaginal birth [1.09 (1.00–1.18)] and for congenital malformations of the mouth or digestive system [1.65 (1.07–2.53)]. Gestational age was inversely associated with AN risk, with increased risks for those born before term [1.40 (1.10–1.77) for gestational age<33 weeks and 1.16 (1.02–1.32) for 33–36 weeks] and decreased risk for those born after week 42 [0.87 (0.78–0.97)].

Bulimia nervosa

Increased BN risk was observed for increasing parental ages, with significant associations for maternal ages 30–34 years [1.12 (1.00–1.24)] and for paternal ages 30–34 [1.12 (1.00–1.25)] and 35–39 years [1.20 (1.05–1.37)].

Birth weight above 4500 g was also associated with significantly increased BN risk [1.41 (1.09–1.82)]. Being born large for gestational age was associated with increased BN risk [1.36 (1.11–1.68)] compared to being born average for gestational age.

Eating disorder not otherwise specified

Significantly increased risk of EDNOS was observed for hemorrhage [1.19 (1.01–1.39)]. Paternal age below 20 years was associated with a decreased risk for EDNOS [0.55 (0.32–0.94)]. Patterns similar to those of AN were also observed for cesarean section [1.18 (1.09–1.29)] and pre-term gestational ages [1.46 (1.14–1.88) for less than 33 weeks of gestation] for EDNOS. Increased EDNOS risk was observed for birth weight below 1500 g [1.57 (1.17–2.12)], being born small for gestational age [1.21 (1.04–1.40)], infections [1.44 (1.13–1.85)], digestive, endocrine, or metabolic disorders [1.33 (1.07–1.65)], other perinatal conditions [1.23 (1.09–1.38)], and for congenital malformations of the mouth or digestive system [2.36 (1.63–3.43)].

Comparison disorders

Multiple factors were associated with risks of depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, and OCD. Most pregnancy complications and smoking were significantly associated with increased risk of depressive and anxiety disorders, as were higher and especially lower parental ages. Some pregnancy complications and smoking were also associated with increased risk of OCD, as were higher maternal ages. Low birth weights, being born small or large for gestational age, and congenital malformations of the mouth or digestive system were also associated with increased risk of depressive disorders. Small for gestational age was also a risk factor for both anxiety disorders and OCD. Multiple birth was associated with decreased risks of depressive and anxiety disorders and increased risk of OCD. Low birth weight, low Apgar score, and prematurity were associated with an increased risk of OCD. Infections, digestive, endocrine or metabolic disorders, and other perinatal conditions were all associated with increased risks of both anxiety disorders and OCD. Congenital malformations of the mouth or digestive system were associated with increased risk of all three disorders, and other congenital malformations also with increased risk of anxiety disorders.

Discussion

In this population-based study, we investigated the associations between pre- and perinatal factors and risk of three types of ED and three comparison psychiatric disorders. Both similarities and differences emerged within EDs and when comparing to other psychiatric illnesses.

We found inverse relationships between gestational age and risks of all three EDs, with increased risks for prematurity and decreased risk for gestational age above 42 weeks, although not significant for BN. Similar patterns were seen for all three comparison disorders. Our results on gestational age are in agreement with previous findings from reviews (Krug et al., Reference Krug, Taborelli, Sallis, Treasure and Micali2013; Raevuori et al., Reference Raevuori, Linna and Keski-Rahkonen2014). Prematurity has previously been shown to be a risk factor for various psychiatric disorders (Byrne, Agerbo, Bennedsen, Eaton, & Mortensen, Reference Byrne, Agerbo, Bennedsen, Eaton and Mortensen2007; Eaton, Mortensen, Thomsen, & Frydenberg, Reference Eaton, Mortensen, Thomsen and Frydenberg2001; Monfils Gustafsson, Josefsson, Ekholm Selling, & Sydsjö, Reference Monfils Gustafsson, Josefsson, Ekholm Selling and Sydsjö2009; Nosarti et al., Reference Nosarti, Reichenberg, Murray, Cnattingius, Lambe, Yin and Hultman2012), suggesting neurodevelopmental factors and a general vulnerability following preterm birth which may lower the threshold for expression of genetic predispositions. A consequence of premature birth is the impaired maturation of the gastrointestinal tract and gut microbiota, which can affect health later in life (Arboleya et al., Reference Arboleya, Sanchez, Solis, Fernandez, Suarez, Hernandez-Barranco and Gueimonde2016; Henderickx, Zwittink, van Lingen, Knol, & Belzer, Reference Henderickx, Zwittink, van Lingen, Knol and Belzer2019), and emerging evidence based on genetic correlations support the idea that AN perhaps should be re-conceptualized as a metabo-psychiatric disorder (Watson et al., Reference Watson, Yilmaz, Thornton, Hubel, Coleman, Gaspar and Bulik2019). Furthermore, preterm children have increased risk of feeding difficulties in infancy (Saigal & Doyle, Reference Saigal and Doyle2008) and early childhood (Hvelplund, Hansen, Koch, Andersson, & Skovgaard, Reference Hvelplund, Hansen, Koch, Andersson and Skovgaard2016), which could contribute to increased ED risk later in life, perhaps in part through a negative impact on the mother–child interaction in relation to feeding situations and food in general.

We found suggestive evidence of increasing risk of AN, and to a lesser degree BN and EDNOS, for increasing parental ages. The increased risk for higher paternal age is in accordance with the findings from previous studies on AN and EDs in general (Javaras et al., Reference Javaras, Rickert, Thornton, Peat, Baker, Birgegard and D'Onofrio2017; McGrath et al., Reference McGrath, Petersen, Agerbo, Mors, Mortensen and Pedersen2014). The steadily increasing relationships for EDs, and AN in particular, differ from the more U-shaped relationships observed for parental ages for both depressive and anxiety disorders in this study. The patterns for parental ages in OCD, a disorder that shares many common traits with EDs and a high genetic correlation with AN (Anttila et al., Reference Anttila, Bulik-Sullivan, Finucane, Walters, Bras, Duncan and Murray2018; Watson et al., Reference Watson, Yilmaz, Thornton, Hubel, Coleman, Gaspar and Bulik2019; Yilmaz et al., Reference Yilmaz, Halvorsen, Bryois, Yu, Thornton, Zerwas and Crowley2018), were more similar to the ones observed for EDs. The increased risk of EDs in offspring of older fathers suggests an influence of age-related de novo mutations, as proposed for other types of psychiatric illness (Frans et al., Reference Frans, Sandin, Reichenberg, Langstrom, Lichtenstein, McGrath and Hultman2013; Malaspina et al., Reference Malaspina, Harlap, Fennig, Heiman, Nahon, Feldman and Susser2001). However, this does not explain the increasing ED risk also seen for higher maternal age, suggesting shared genetic or environmental exposures influencing both parental reproductive age and offspring ED risk and/or environmental influence of parental age on ED risk in offspring. The associations between parental ages and EDs may, in part, be driven by higher educational attainment of older parents, as postponing reproduction until after completion of higher education is common in Denmark. Several studies have found increased incidence rates of EDs in offspring of highly educated parents (Ahrén, Chiesa, af Klinteberg, & Koupil, Reference Ahrén, Chiesa, af Klinteberg and Koupil2012; Ahrén et al., Reference Ahrén, Chiesa, Koupil, Magnusson, Dalman and Goodman2013; Ahren-Moonga, Silverwood, Klinteberg, & Koupil, Reference Ahren-Moonga, Silverwood, Klinteberg and Koupil2009; Goodman, Heshmati, & Koupil, Reference Goodman, Heshmati and Koupil2014a; Goodman, Heshmati, Malki, & Koupil, Reference Goodman, Heshmati, Malki and Koupil2014b), and Watson et al. (Reference Watson, Yilmaz, Thornton, Hubel, Coleman, Gaspar and Bulik2019) found positive genetic correlations between AN and educational attainment measures.

For maternal smoking, the decreased risk was observed for AN, but not for other disorders. A study using the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study reported that the prevalence of smoking during pregnancy was non-significantly lower in mothers with AN than in mothers with other types of ED and mothers with no EDs (Lupattelli et al., Reference Lupattelli, Spigset, Torgersen, Zerwas, Hatle, Reichborn-Kjennerud and Nordeng2015), which might help explain the lower AN incidence in offspring of smoking mothers in the present study. Another possible explanation for this association could be the lower prevalence of smoking during pregnancy and the higher incidence rate of AN in offspring of mothers with higher educational levels (de Wolff et al., Reference de Wolff, Backhausen, Iversen, Bendix, Rom and Hegaard2019). It should be noted that smoking status was self-reported by mothers in early pregnancy and probably has lower validity than most variables included in this study due to social desirability bias (Grimm, Reference Grimm, Sheth and Malhotra2010).

Multiple birth increased the risk of EDs in a dose-response manner for twin and triplet/quadruplet births compared to singleton births. This was most strongly observed in AN, which replicates the results of a Swedish study with a design analogous to the present study (Goodman et al., Reference Goodman, Heshmati, Malki and Koupil2014b). A similar pattern was seen in OCD, but not in depressive or anxiety disorders, where multiple births were associated with decreased risk. The increased risk of EDs seen in offspring of multiple births could possibly be attributed to increased risk of complications during pregnancy and birth, although we found no significant differences in risk estimates when adjusting multiple birth for other birth characteristics, pointing to environmental influence linked to growing up as a twin.

BN incidence rates were increased for large for gestational age and (non-significantly) decreased for small for gestational age, a pattern that is opposite those observed for EDNOS, depressive disorders, and anxiety disorders with increased risks for small for gestational age. This aligns with the study by Goodman et al. (Reference Goodman, Heshmati, Malki and Koupil2014b), which found a positive dose–response relationship between birth weight and BN risk. This association might be an indicator of overweight mothers being both more likely to give birth to a large baby and to have an overweight child (Black, Sacks, Xiang, & Lawrence, Reference Black, Sacks, Xiang and Lawrence2013; O'Reilly & Reynolds, Reference O'Reilly and Reynolds2013). High body mass index in even very young girls has recently been shown to be a risk factor for later development of BN (Yilmaz, Gottfredson, Zerwas, Bulik, & Micali, Reference Yilmaz, Gottfredson, Zerwas, Bulik and Micali2019).

For EDNOS, we identified several statistically significant associations, particularly within the perinatal conditions, suggesting a susceptibility during the perinatal period. Similar results were observed for anxiety disorders and OCD. The doubled risk seen singularly in EDNOS for children born with congenital malformations of the mouth or digestive system could suggest that some of those who are diagnosed with EDNOS, in fact, suffer from eating problems directly associated with their congenital malformations.

The observed increased risks of all three ED types (although only statistically significant for AN) for genitourinary tract infections and the significantly increased risk of EDNOS for perinatal infections are in agreement with studies that have reported increased risks of AN, BN, and EDNOS following hospitalization or medication for infection (Breithaupt et al., Reference Breithaupt, Köhler-Forsberg, Larsen, Benros, Thornton, Bulik and Petersen2019) and an association between exposure to in utero viral infections and increased AN risk in offspring (Favaro et al., Reference Favaro, Tenconi, Ceschin, Zanetti, Bosello and Santonastaso2011). Fetal exposure to maternal infection and the resulting immune response may affect offspring neurodevelopment (Deverman & Patterson, Reference Deverman and Patterson2009) and later mental health, and infectious agents may be able to cross the blood-brain barrier and affect the central nervous system (Banks, Kastin, & Broadwell, Reference Banks, Kastin and Broadwell1995). Significantly increased risks were also seen for genitourinary tract infection in all three comparison disorders and for perinatal infections in anxiety disorders and OCD, demonstrating that the infection-psychiatric illness association is not specific to EDs (Köhler-Forsberg et al., Reference Köhler-Forsberg, Petersen, Gasse, Mortensen, Dalsgaard, Yolken and Benros2018).

Strengths and limitations

This nationwide population-based study included all individuals born in Denmark 1989–2010 to Danish-born parents. We were able to follow more than 1 million individuals for up to 22 years from their 6th birthday. A main strength of the study is that all data were drawn from Danish registers, which cover all Danish citizens from birth until death. Thereby, loss to follow-up and selection bias is eliminated. Furthermore, the use of register information also eliminates most recall and reporting bias.

The register information used in this study included only hospital-based diagnoses for defining exposures and outcomes. Several of the pre- and perinatal factors were only defined or available for a subset of the cohort, and there are probable differences in their reliability. We assume that measures such as birth weight, Apgar score, and gestational age are fairly reliable measures, whereas, for example, self-reported maternal smoking is more uncertain. Diagnoses recorded in the Danish health registers are generally reliable with high positive predictive values (Bock, Bukh, Vinberg, Gether, & Kessing, Reference Bock, Bukh, Vinberg, Gether and Kessing2009; Jakobsen et al., Reference Jakobsen, Frederiksen, Hansen, Jansson, Parnas and Werge2005; Lauritsen et al., Reference Lauritsen, Jorgensen, Madsen, Lemcke, Toft, Grove and Thorsen2010; Phung et al., Reference Phung, Andersen, Hogh, Kessing, Mortensen and Waldemar2007). However, the validity of the various ED diagnoses may differ: In ICD-10 there is no binge-purge AN subtype and these patients can be difficult to diagnose in a systematic way – some clinicians will diagnose them with AN and some with BN, depending on their weight. This could potentially bias our BN results toward the patterns observed for AN. However, the number of conflicting cases is probably relatively small. The ENDOS diagnosis is given to a broad spectrum of ED subtypes – patients not fulfilling all diagnostic criteria of AN or BN, and patients with binge eating or other types of ED. How this affects our results is difficult to determine.

The Danish healthcare system is paid through taxation and is therefore free of charge for Danish citizens, including treatment in hospitals. This eliminates some differential access to healthcare, but utilization of mental health services still differs depending on factors such as socio-economic status and distance to healthcare providers (Packness et al., Reference Packness, Waldorff, Christensen, Hastrup, Simonsen, Vestergaard and Halling2017; Packness, Halling, Simonsen, Waldorff, & Hastrup, Reference Packness, Halling, Simonsen, Waldorff and Hastrup2019). This may have biased our results, as individuals from a higher socio-economic background could be more likely to be diagnosed with both the outcome disorders and several of the exposure conditions. Furthermore, we were unable to capture those diagnosed only in primary care, those not seeking care, and those with sub-threshold symptoms. Therefore, it is likely only the most severe cases were included, and the true incidences of both outcomes and several exposures are most likely higher than reported here.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that certain pre- and perinatal factors may influence later ED risk. The increased risks of EDs were similar to those seen for other psychiatric illnesses for prematurity and maternal genitourinary tract infection, suggesting a universal influence on neurodevelopment and later mental health. Conversely, patterns of association with parental ages and multiple birth for EDs was similar to OCD but different from those seen for other psychiatric illness, perhaps pointing to differing responses to childhood environment. Comparing ED subtypes, differences also emerged with regard to smoking during pregnancy, being born large for gestational age, and certain congenital malformations, suggesting disorder-specific vulnerabilities also within EDs. Our results encourage further replication in large samples and genetically informed studies to disentangle the potential genetic and environmental mechanisms of the associations.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291719003945

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Lundbeck Foundation (J.T.L., L.P., grant number R248-2017-2003), (L.P., grant number R276-2018-4581); the Klarman Family Foundation (J.T.L., C.M.B, L.M.T.); and Helsefonden (J.T.L., grant no. 18-B-0154).

Conflict of interest

C.M.B. reports Shire (Scientific Advisory Board member); Idorsia (consultant); Pearson (author, royalty recipient).