In April 2015, the Guatemalan Public Prosecutor’s Office (MP) and the UN International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG) uncovered a massive customs fraud network operating in the country’s tax administration. Dubbed La Línea after the telephone line used to negotiate customs fraud, the structure oversaw illicit procedures in which importers paid 40 percent of the customs duties they legally owed to the state and 30 percent to criminal operatives, pocketing the remaining 30 percent (CICIG and MP 2015). Though the total amount diverted from state coffers is impossible to discern with precision, think tank ASIES estimates that in 2014 alone, the Guatemalan state was defrauded some $940 million, or 1.6 percent of GDP (ASIES 2017, 13).

The exposure of La Línea prompted a series of popular protests on a scale unprecedented since Guatemala’s return to civilian rule in the mid-1980s. Guatemalans of all political stripes converged on the capital city’s Plaza de la Constitución with signs excoriating the country’s corrupt political class and demanding ¡Renuncia Ya!—that President Otto Pérez Molina, a former military general, and his vice president, Roxanna Baldetti, tender their resignations, which they eventually did (see Schwartz Reference Schwartz2020a).

For the protesters, the La Línea revelations served as a watershed moment in the country’s history. However, buried in the renewed political fervor was something else that received far less attention but was equally striking: this was not the first time that a massive customs fraud scheme had been uncovered in Guatemala’s tax administration. In September 1996, almost two decades earlier and on the eve of the signing of peace accords to end Guatemala’s 36-year civil war, the MP exposed a nearly identical scheme that had taken root within the Ministry of Finance. The earlier criminal structure was named the Moreno Network after the low-ranking military intelligence agent who managed the scheme, Alfredo Moreno. The investigations, however, revealed that Moreno was not the one pulling the strings. Instead, the predatory institutional arrangements in Customs were devised and implemented by an elite clique of high-ranking military intelligence officers, which had seized control of the state as the country’s armed conflict escalated in the late 1970s. These counterinsurgent elites crafted and institutionalized new procedures for fabricating customs forms and “disappearing” shipping containers to siphon off revenue destined for state coffers.

The predatory informal rules governing customs fraud survived from the Moreno Network to La Línea despite robust, internationally backed reforms in the late 1990s aimed at redesigning formal institutions and redistributing political power and resources. How did the informal customs fraud procedures endure for nearly two decades despite the reform efforts? What does this case reveal about the mechanisms through which predatory informal rules persist more broadly? This case warrants attention not only because it finds parallels in contexts across the globe, but also because it encapsulates modalities of institutional resilience that remain underexplored in existing literature. To address these shortcomings, this article unpacks the mechanisms of informal institutional persistence and offers broader insights into the ways formal institutional reforms fail to uproot predatory informal rules, instead allowing them to adapt and survive.

Drawing on unique archival and interview data often difficult to access in postauthoritarian and postconflict settings, this research found that the persistence of the predatory informal rules in the Guatemalan case is best attributed the adaptive abilities of the dominant coalition with a stake in the fraudulent customs procedures. Despite their displacement from the formal state sphere, the military intelligence elites who oversaw the illicit customs scheme managed to exercise coercive power through political party channels, placing strategic allies in government posts. Moreover, measures to further privatize the port system allowed authoritarian-era elites to occupy new, nonstate spaces critical to upholding the predatory informal rules. In sum, the survival of the corrupt institutional arrangements does not reflect reformers’ inability to disrupt the dominant coalition in government circles; instead, it illustrates the failure to guard against that coalition’s reconstitution and continued influence after its initial displacement from the state sphere.

Overall, this article offers a number of contributions to the study of informal institutions and state reform in Central America and more generally. First, against a prevailing scholarly focus on processes of institutional change, it distills and hones the mechanisms underlying the persistence of predatory informal rules amid Latin America’s abiding gap between the promises and realities of democratization. It illustrates that distributional approaches to institutional survival must be attentive not only to how political power may be reallocated within the contours of the official state sphere, but also how those with a stake in the informal rules exercise power from outside. Relatedly, the case of Guatemala’s customs administration indicates that state reform is about much more than “the state” itself. Even within standard policy prescriptions, reforming state institutions must better account for how political and economic liberalization facilitates alternative spaces to wield authority and subvert change.

Furthermore, this article provides a new perspective on peacebuilding and democratization in Central America specifically. Though existing regional analyses note the vast deficiencies of postauthoritarian efforts to strengthen formal institutions (e.g., Cruz Reference Cruz2011; Bowen Reference Bowen2019; Wade Reference Wade2016; Lehoucq Reference Lehoucq2012; Schneider Reference Schneider2012), this case study paints a more complex picture. Substantial reforms to purge the bureaucracy and insulate administrative institutions from undue influence did, in some cases, take place. Thus, the limits of the state reform process in Guatemala, and Central America more broadly, may not necessarily be about the failure to restructure power within the state but the lack of attention to the informal channels of political influence outside it.

The Persistence of Predatory Informal Rules: Unpacking Potential Mechanisms

Despite the advance of democratization throughout much of Latin America, political and economic reforms have given way to lackluster institutional performance, diminishing citizenship and the rule of law (Brinks et al. Reference Brinks, Steven and María2019). Within these institutional gaps lies another defining feature of Latin America’s political landscape: informal institutions, or “socially shared rules, usually unwritten, that are created, communicated, and enforced outside officially sanctioned channels” (Helmke and Levitsky Reference Helmke and Steven2006, 5–6). While some informal rules bolster democratic aims (Gryzmala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse2010, 324–31; Holland Reference Holland2017), others compete with and subvert the formal rules, undermining democracy and development (Brinks Reference Brinks2007). Contemporary constitutions, party systems, and bureaucracies sit alongside what O’Donnell (Reference O’Donnell1996, 40, 43) termed particularism, or corrupt schemes involving patronage or nepotism. Instead of aberrations, such informal rules reflect “the way most political institutions actually work.”

This article focuses on a specific subset of these particularistic schemes, which it terms predatory informal rules. Drawing on scholarly efforts to conceptualize predatory states, it defines predatory informal rules as those “that promote the private interests of the dominant groups inside the state (such as politicians, the army, and bureaucrats) and/or influential private groups with effective lobbying” (Vahabi Reference Vahabi2020, 2).Footnote 1 Such rules structure forms of state-based extraction “at the expense of society, undercutting development” (Evans Reference Evans1995, 12). They are thus institutional arrangements that subvert the official activities state organizations are typically expected to perform (i.e., the collection of tax revenue, monopolization of violence, and provision of basic goods and services).

In many ways, predatory informal rules resemble a specific type of corruption—what scholars have referred to as “institutionalized,” “endemic,” or “systemic” corruption (Darden Reference Darden2008; Mishra Reference Mishra2006; Persson et al. Reference Persson, Rothstein and Teorell2013; Chayes Reference Chayes2017). Institutionalized corruption not only encompasses the pervasive use of public office for private gain, but is a form of corruption that is rule-bound—it is “organized and enforced from above”; and “a refusal to go along risks incurring important costs” (Helmke and Levitsky Reference Helmke and Steven2006, 7).

Though sweeping governance reforms and anticorruption efforts have sought to stamp out predatory informal rules within the state apparatus, such campaigns, more often than not, produce little substantive change, particularly in developing contexts that lack the bureaucratic means to implement reforms (Bersch Reference Bersch2019; Schneider and Heredia Reference Schneider and Blanca2003; Persson et al. Reference Persson, Rothstein and Teorell2013). Indeed, while “punctuated equilibrium” models treat such reforms as critical junctures that produce institutional change, in the weak institutional environments of the developing world, these moments are often more conducive to institutional resilience and stability, allowing the prevailing rules to solidify or even deepen (Levitsky and Murillo Reference Levitsky and María2013, 94; Madariaga Reference Madariaga2017; Goldsmith Reference Goldsmith2017). But despite these patterns, there have been few scholarly efforts to understand how these moments serve as sites of institutional stability and the precise mechanisms through which existing institutional arrangements outlast governance reforms. As Madariaga (Reference Madariaga2017, 638) notes, “contemporary debates on causal mechanisms and institutional change have installed the idea that change is pervasive, leaving us with few alternatives to understand continuity.”

Questions of institutional continuity are perhaps even more important when focusing on the kinds of informal institutions that animate this study: predatory informal rules in weak states. While a focus on formal institutions might attribute institutional persistence to the failure of or deficiencies within processes of change, scholars of informal institutions posit that informal rules “can replace, undermine, and reinforce formal institutions irrespective of the latter’s strength” (Grzymala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse2010, 311, emphasis in original). Because official rules and their unwritten counterparts can coexist in the same policy domain, formal and informal rules are not necessarily mirror images of one another; the deficiency (or strength) of the former does not directly correspond to the persistence (or breakdown) of the latter. As Grzymala-Busse (Reference Grzymala-Busse2010, 323) notes, predatory informal institutions in postcommunist Europe, such as illicit party financing and unregulated privatization, undermined “both powerful and weak formal institutions.” Thus, the unofficial quality of predatory informal rules means that persistence, even in less institutionalized settings, cannot be attributed merely to the failures of formal change, but itself is a process that warrants nuanced theorization.

To further this aim, this article brings together the limited scholarship on institutional persistence with literature on informal institutions and institutionalized corruption to distill three potential mechanisms underlying the persistence of predatory informal rules. These hypothesized mechanisms will serve as the basis of an inductive process-tracing analysis within Guatemala’s tax administration. They are the manipulation of formal institutional reforms, the institutionalization of cultural categories or ideas about appropriate behavior, and the preservation of the dominant social and political blocs—the distributional coalitions—that underwrite the existing rules.

Per the first proposed mechanism, predatory informal rules survive periods of state reform through elite manipulation of the timing, implementation, and enforcement of corresponding formal institutional changes, thereby preserving the informal status quo. Under one possible scenario, incumbents or “rulemakers” intent on preserving existing institutional arrangements outmaneuver reform coalitions by stalling implementation until mobilization for reform has subsided (Capoccia Reference Capoccia2016). However, even when reforms are implemented, political elites can “use de jure discretion to limit enforcement” or “use de facto discretion to permit—or engage in—the violation of the rules” (Levitsky and Murillo Reference Levitsky and María2013, 101).

Weak enforcement allows the predatory informal rules to persist because the new formal rules “remain on the books as window dressing” without affecting the institutional status quo (102). These explanations, though slightly varied, are premised on the same general mechanism, which reproduces the potentially misguided view that the strength (or weakness) of formal and informal rules is inversely linked: predatory informal rules endure because the formal institutional changes meant to dismantle them do not take hold and the corrupt incentive structures that underlie them thus remain intact (Manion Reference Manion2004; Geddes Reference Geddes1994).

A second potential mechanism examines the question of institutional survival more directly, focusing on the role of ideas and cultural categories. Here, predatory informal rules endure because of abiding collective beliefs that they are “normal” or “legitimate” (see March and Olsen Reference March and Olsen1998). Capoccia (Reference Capoccia2016) refers to this mechanism as the “institutionalization of cultural categories,” a process in which stable normative understandings of rules and behaviors counteract substantial reform. Scholarship on corruption similarly highlights the ideational foundations of predatory informal rules, noting how shared expectations generate “other moralities” (Prasad et al. 2018, 105).

At the same time, studies of institutionalized corruption note that collective beliefs about corrupt behavior as improper and illegitimate are often not enough to dismantle the rules governing such acts, if they are so pervasive (Mishra Reference Mishra2006, 349). Corruption, in this view, can be modeled as a collective action problem: “even if the majority of actors morally condemn corrupt practices … the incentives to organize a solution to the collective action problem are simply undermined by shared expectations about other actors’ behavior” (Persson et al. Reference Persson, Rothstein and Teorell2013, 457). Thus, this second mechanism may provide less leverage in examining the persistence of institutionalized predation.

The third potential mechanism underlying the persistence of predatory informal rules focuses on the distribution of political power and resources. Predatory informal rules outlast governance reforms through the influence of dominant social and political blocs, which, according to Madariaga (Reference Madariaga2017, 642), maneuver “to defend [their] interests and policy preferences,” thus preserving the institutional status quo.Footnote 2 Consistent with distributional approaches within studies of formal institutions (e.g., Mahoney and Thelen Reference Mahoney and Kathleen2009), informal institutions in developing contexts (e.g., Helmke and Levitsky Reference Helmke and Steven2006), anticorruption reform (e.g., Manion Reference Manion2004), and crony capitalism (e.g., Kang Reference Kang2002), predatory informal rules survive through the ability of the institutional “winners” within the existing system—those with a stake in predatory activities—to retain their political influence and prerogatives. I refer to this group as the distributional coalition.Footnote 3

The dominant distributional coalition ensures the stability of the predatory informal rules by using its political clout to shield those abiding by the informal institutional order from sanction and through innovations, or “marginal adjustments” (Madariaga Reference Madariaga2017, 642), that allow it to evade detection and outlast reform. In short, distributional approaches go beyond the enforcement-based mechanism. Formal and de facto stakeholders not only limit or manipulate the enforcement of formal institutional changes (Levitsky and Murillo Reference Levitsky and María2013), but they also actively ensure the preservation of the corrupt informal rules through processes of adaptation and by wielding their influence to ensure impunity.

Though such approaches focus on the question of persistence and are more attentive to power, there remains a lack of clarity about the channels through which distributional coalitions exercise influence to ensure the continuity of predatory informal rules. Studies of formal institutional persistence highlight the presence of hegemonic social and political blocs within official circles of power, asserting their clout through “the continuity of government posts and influence in policymaking” (Madariaga Reference Madariaga2017, 642). Yet predatory rules can survive even when authoritarian or wartime actors are removed from official political power. As scholarship on transitional justice illustrates, authoritarian-era specialists in violence, for example, often defect to organized crime following democratization and secure impunity through previous ties (Trejo et al. Reference Trejo, Albarracín and Tiscornia2018). Research on state capture amid political liberalization suggests a similar dynamic, as powerful private sector blocs distort decisionmaking for their own benefit (Hellman et al. Reference Hellman, Geraint and Daniel2003, 752). This dynamic can be seen in Central American bureaucracies, where undue societal influence is just as, if not more, pronounced than meddling by politicians (Bowen Reference Bowen2017; Chayes Reference Chayes2017).

Furthermore, studies of privatization as a solution to institutionalized corruption shed light on the informal centers of political and economic power that can reinforce predatory informal rules. By allotting leaders “discretionary power” to authorize private concessions, market reforms often “engender changes in the modalities of corruption” without eliminating them, as newly empowered private sector elites buy into previous predatory procedures (Manzetti and Blake Reference Manzetti and Blake1996, 685). Economic liberalization can thus create new avenues to uphold the old rules, rather than redistribute power (Snyder Reference Snyder2001).

In sum, this third proposed mechanism—the survival of the prevailing distributional coalition—requires further refining to better understand whether dominant social and political blocs uphold predatory informal rules primarily through official policymaking circles, or whether such rules can endure through extra-state spaces and unofficial channels as the prevailing distributional coalition reconstitutes itself on the margins of government and adapts to the postreform environment. The empirical analysis in this study bears in mind both variants of this third mechanism.

Case Selection, Methodology, and Data

To examine how predatory informal rules persist in the face of comprehensive state reforms, this study analyzes the case of Guatemala’s tax and customs administration following the transition to democracy and the end of the 36-year civil war. This particular case is useful for identifying the mechanisms underlying informal institutional endurance precisely because Guatemala’s customs apparatus experienced significant changes in the late 1990s, following the signing of the peace accords and the Moreno Network revelations, thus reflecting the “big bang model” of anticorruption reform (Prasad et al. 2018).Footnote 4 Yet the survival of the predatory informal rules within the customs apparatus continued to undermine formal taxation for decades, as the case of La Línea illustrates, raising the question of how the authoritarian-era institutional arrangements remained so resilient despite transition-era transformations.

Moreover, as a case of predatory informal rules, Guatemala’s fraudulent customs scheme reflects a broader phenomenon that stymies political and economic development yet remains poorly understood. Illicit, predatory activities in diverse postauthoritarian and postconflict contexts often remain resilient despite efforts to remake state bureaucracies and security services (Barma Reference Barma2016). Yet in contrast to many comparable contexts, the Guatemalan case offers extraordinary qualitative data on illegal practices, which are often difficult to access in fragile transitional settings. In particular, stores of wartime archives and recent investigations conducted by the landmark CICIG, established in late 2006 to combat illegal security structures, help shed light on the predatory informal rules in Customs in Guatemala. Though the CICIG was ousted in late 2019 after Guatemalan president Jimmy Morales refused to renew its mandate, earlier investigations provide fine-grained evidence that allows for examining the mechanisms of informal institutional persistence in depth.

To examine the underlying mechanisms, this analysis utilizes process tracing, “the analysis of evidence on processes, sequences, and conjunctures of events within a case for the purposes of either developing or testing hypotheses about causal mechanisms” (Bennett and Checkel Reference Bennett and Checkel2015, 7–8). While this article primarily focuses on inductive theory building, it also takes seriously the interplay between inductive and deductive modes and draws on broad theoretical propositions in existing literature as the scaffolding of theory construction and refinement (see Bril-Mascarenhas et al. Reference Bril-Mascarenhas, Maillet and Mayaux2017).

The data for this analysis come from a number of archival and interview sources. Original wartime documentation was collected from the Historical Archive of the National Police (AHPN), the Presidential Military Staff (Estado Mayor Presidencial, EMP) archive, and the Ministry of Finance, in addition to court documents, declassified US government cables, CICIG presentations and communiqués, and press clippings. Sixty-five elite interviews also were conducted with former military and civilian intelligence officers, Ministry of Finance personnel, prosecutors, and business leaders.Footnote 5 These archival and interview data were used to carefully triangulate empirical claims related to the postwar persistence of the informal customs procedures in Guatemala’s tax administration.

Prereform Origins: The Wartime Consolidation of the New “Rules of the Game”

On September 14, 1996, authorities from Guatemala’s Public Prosecutor’s Office (MP) raided the home of Alfredo Moreno Molina, the alleged leader of a criminal network within the customs administration, seizing computers, personnel files, and more than 50 IDs issued to him by different state entities (Siglo Veintiuno 1996a). As they put the pieces together, the investigators uncovered a vast series of illicit customs fraud procedures within the Ministry of Finance and the General Directorate of Customs, which were implemented by a high-level criminal structure, the Moreno Network, and may have defrauded the Guatemalan state of up to $30 million on a monthly basis for nearly 20 years.

The predatory institutional arrangements implemented and enforced by the Moreno Network in Customs were rooted in changes that occurred at the height of Guatemala’s civil war in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when new counterinsurgent imperatives prompted the increased professionalization and autonomy of military intelligence. Both a perceived increase in rebel threat and intramilitary mistrust facilitated the creation of elite intelligence units insulated from broader military structures (see Schwartz Reference Schwartz2020b).

One such unit, tied to the EMP, was known as the General Archive and Support Services Section, or El Archivo. Equipped with superior training and resources, El Archivo was tasked with intelligence collection and analysis “on individuals considered enemies of … the government” (CEH 1999, vol. 2, 101). But its operational discretion went beyond neutralizing regime opponents and included control of numerous government ministries. The penetration of the state apparatus was seen as a necessary measure “to monitor the guerrilla movement” and to combat the smuggling of weapons over land (Intelligence Agents 2016; Intelligence Officer 2016; Anticorruption Expert 2015). Thus, by the late 1970s, members of Intelligence had seized the entire state apparatus, including the Ministry of Finance, through a new section called the Office of Special Ministerial Services (SEM) (CEH 1999, vol. 2, 101).

The case files reveal that through the Moreno Network, military intelligence elites in the SEM introduced two kinds of predatory informal procedures to capture customs revenue. The first involved the fabrication of customs forms to underreport the amount of customs duties legally paid. Here,

two forms were created … one was legal and the other fictitious, but with the same identification number. The original was given to the client…. And the copy was made with the false form, which included a much smaller amount…. There would be a form saying they paid 50,000 quetzales, but according to the fictitious form, they paid 1,000, so the state was defrauded 49,000 quetzales. (Organismo Judicial 2003).

A second method involved the “theft” of shipping containers: declaration forms “would be stamped as received by the General Directorate of Customs, but taxes were never paid,” and shipments would vanish, only to have the merchandise appear in warehouses or store shelves weeks later (Organismo Judicial 2003).

Day-to-day enforcement of the predatory informal rules in Customs occurred through violent and nonviolent coercion. The Moreno Network possessed total control over the naming and transfer of customs personnel, enforcing the rules governing customs fraud with threats of layoffs. Moreover, according to Moreno’s right-hand aide, Francisco Javier Ortiz, “Moreno made it known that whoever got in his way, he would kill him” (Organismo Judicial 2003). Customs inspectors who testified in 1999 intimated that this was actually the fate of several network associates who died in the early 1990s.

But the military intelligence officers pulling the strings also sought to secure the survival of the illegal scheme into the future. This required a longer-term vision for consolidating a climate of impunity and a robust client base. As a result, the Moreno Network forged a broader distributional coalition of state and nonstate actors who reproduced the new rules in Customs. This coalition included two key sets of players: an association of lawyers, politicians, judges, and military officers; and importers and commercial elites.

To foster an environment in which the Moreno Network could operate without the threat of judicial sanction, this coalition developed a formal legal body called Grupo Salvavidas (life preserver group), which used the resources accrued through customs fraud to buy impunity in the MP and the court system. Grupo Salvavidas was created to serve as “a powerful influence-peddling [tráfico de influencias] network” (La República 1996). In the words of one informant, “The name Salvavidas had its significance … to be able to save anyone involved in actions related to contraband, drug trafficking, and tax evasion from the application of justice” (La República 1996). Led by the military officials, who drew on their intelligence knowhow, Grupo Salvavidas targeted key actors participating in the investigations and trials of members or associates, offering bribes in exchange for information, silence, or favorable outcomes. It was thus the nucleus of the distributional coalition underwriting the informal rules, utilizing its resources and contacts to bring key actors into the fold and secure impunity.

Beyond Grupo Salvavidas, the longer-term viability of the predatory customs procedures also depended on a solid client base to demand the Moreno Network’s services. This client base was cultivated among a wide range of foreign and domestic business elites and importers, who grew accustomed to the savings they accrued by arranging customs duty adjustments and shipment “thefts” in exchange for off-the-books payments. Recovered correspondence with domestic and foreign importers and exporters reveals how the Moreno Network secured the necessary arrangements with customs administrators and inspectors to allow “clients” to pass shipment containers through customs processing uninspected and with falsified forms.Footnote 6 There is evidence that such procedures also provided a conduit for illicit goods, such as narcotics, particularly as Central America’s emerging drug market evolved (Hernández S. Reference Hernández1996).

A robust multisectoral alliance of institutional “winners”—a broad distributional coalition—was thus critical to consolidating the new, informal rules of the game within Guatemala’s customs apparatus. That alliance included the military intelligence elites who controlled the state apparatus, the high-ranking state officials in the judicial and security apparatus who traded impunity for illicit gains, and the economic elites who had financial incentives to abide by the informal rules and evade formal customs processing.

Reform and Postreform Continuity: Adaptation of the Distributional Coalition

Following the Moreno Network revelations, reformers in the first peacetime government of Álvaro Arzú (1996–2000) remade the tax administration, creating a new, autonomous entity, the Superintendent of Tax Administration (SAT). Despite these transition-era efforts to purge and modernize Guatemala’s tax agency, the country’s fiscal apparatus remained plagued by the predatory informal rules that undermined revenue extraction, as the 2015 La Línea scandal revealed. Succumbing to the same institutionalized predation of the conflict era, the SAT “started as a dream and turned into a nightmare,” noted one executive official (Executive Official 2017).

The remainder of this article assesses potential mechanisms of informal institutional persistence to account for the resilience of the predatory informal rules within Guatemala’s newly modernized tax administration. Overall, the analysis reveals that the postreform survival of the predatory informal rules is best attributed to the adaptation and reconstitution of the authoritarian-era distributional coalition. Yet these findings also illustrate that the dominant political and economic blocs that constitute the distributional coalition did not need to directly occupy official government posts to uphold the predatory informal rules; instead, they exerted influence through semi- or extra-state spaces—such as political party channels and privatization processes—to maintain impunity and locate strategic allies on the inside to preserve the institutional status quo.

To make these claims, this section unfolds as follows. First, it surveys the reforms that took place within the tax and customs administration during Guatemala’s transition, with special attention to how the changes displaced powerful military and political blocs from official government positions. Second, it illustrates how the reconstitution of the dominant distributional coalition on the margins of state power facilitated informal institutional survival. Then it examines the two alternative mechanisms proposed above—manipulation of formal institutional reforms and shared ideas of “normal” behavior—to illustrate how these receive less support in this analysis.

SAT Reforms and the Redistribution of Official Political Power

The foundations of tax administration reforms were elaborated in Guatemala’s Peace Accord on Socioeconomic Issues, signed on May 6, 1996. In the accord, the Guatemalan state pledged to increase the tax burden by 50 percent between 1995 and 2000—a commitment that would set the goal at 12 percent of GDP. The accord further stipulated policy measures to achieve this objective, among them “promoting a reform to the Tax Code to establish heavier sanctions for evasion,” “evaluating and strictly regulating tax exemptions [to eliminate] abuses,” and “strengthening the existing mechanisms of investigation and tax collection” (Government of Guatemala 1996).

While the accord did not explicitly mandate the creation of an entirely new fiscal apparatus, top Ministry of Finance authorities were convinced that there was no rescuing the two existing entities responsible for tax collection: the General Directorate of Customs and the General Directorate of Internal Revenue. In the words of one high-ranking official, “when we went in to see what was going on with the General Directorates of Customs and Internal Revenue, we saw that there was corruption on all sides” (Executive Official 2017). In November 1996, then minister of finance José Alejandro Arévalo announced the dissolution of both branches, the activities of which would be subsumed by the new tax collection agency, the SAT (Siglo Veintiuno 1996e). With the support of international financial institutions like the World Bank, Decree 1-98 laid out the SAT’s functions, which included “the collection, control, and auditing … of taxes, … the administration of the customs system, [and] carrying out judicial actions to collect taxes” (ICEFI 2007, 220).

Broadly, the SAT sought to “recover society’s confidence in public authority” by eliminating the predatory informal rules that allowed military, political, and economic elites to capture state revenue on a systematic basis (Arévalo Reference Arévalo2014, 5). One institutional aspect crucial to this process was the enhanced autonomy built into the SAT’s design. Whereas the authoritarian-era Ministry of Finance was led by executive appointees, the SAT was headed by a board of directors, which consisted of the Minister of Finance at the helm; the superintendent, named by the president; and three additional members, named by the legislative branch, the courts, and the country’s universities, respectively (El Gráfico 1997). The SAT thus assumed a corporate structure meant to ensure that no single political force was able to dominate or to engage in undue meddling. Additionally, the newly minted SAT was granted its own budget and was not subject to previous civil service laws restricting its ability to hire new employees—measures seen as stemming clientelism and preventing previous fraudulent operations from re-emerging.

The postauthoritarian reforms also sought to bring an end to the predatory informal rules in Customs by dismantling the wartime distributional coalition that wielded total control over the state apparatus. Following the 1986 return to civilian rule, military intelligence elites prominent at the height of the counterinsurgent campaign continued to rotate through high-level government posts (Siglo Veintiuno 1996g; El Periódico 2001), but this changed following the Moreno Network revelations in late 1996. The ensuing months saw the exodus of previously powerful counterinsurgent actors from formal military ranks. Drawn primarily from Guatemala’s naval forces, Arzú’s military chiefs of staff oversaw the discharge of the key architects of the customs fraud network, all of whom were high-level army intelligence officers who had occupied top posts during the 1980s and 1990s. Though the military would remain a prominent political force, the “old guard” that had institutionalized customs fraud would, in theory, no longer have influence in executive decisionmaking.

Perhaps the most important of the officers expelled was Luis Francisco Ortega Menaldo, who served in the EMP from 1979 to 1982. Ortega Menaldo enjoyed significant political influence as the son-in-law of former president Carlos Manuel Arana Osorio (1970–74), who oversaw the escalation of counterinsurgent activities. During his father-in-law’s presidency, Ortega Menaldo was a mere adjutant in the EMP, but in 1978, he was brought in by then minister of finance Hugo Tulio Búcaro to “help control tax collection” (Brenes and Shetemul 1992). Once in the Ministry of Finance, Ortega Menaldo installed the SEM office and served as its first chief until the March 1982 coup. Even after the 1986 return to civilian rule, Ortega Menaldo continued to occupy prominent political positions, including head of the EMP in the early 1990s.

Ortega Menaldo was discharged from the military after Moreno’s capture, along with another of the military intelligence officers who directed the Ministry of Finance’s SEM office during the 1980s: Roberto Letona Hora (El Periódico 1996). According to police archives, Letona Hora served as SEM chief following the August 1983 coup that ousted military president Efraín Ríos Montt. Even after ceding that post, Letona Hora reportedly served as a primary liaison between the Moreno Network and international commercial interests seeking to arrange customs duty adjustments and the passage of contraband (Zamora Reference Zamora2002).

The list of military officials forced into retirement only grew during the late 1990s, coming to include then vice minister of defense César Augusto García González; Colonels Mario Roberto García Catalán, Rolando Augusto Díaz Barrios, Jacobo Esdras Salán Sánchez, and Major Napoleón Rojas Méndez (Siglo Veintiuno 1996b; Robles Montoya 2002, 126). Beyond military circles, the government ousted other security and judicial personnel linked to the customs fraud network, including 12 chiefs from the national police and a local magistrate (Siglo Veintiuno 1996c, d).

Another key reform measure meant to shift the balance of power and dismantle the authoritarian-era distributional coalition involved intervening in Guatemala’s port system to extricate it from military control. Guatemala’s national port system consisted of two main ports: the Quetzal Port on the Pacific Ocean and the Santo Tomás de Castilla Port on the Atlantic Ocean. Both ports were administered by their own port companies, which, while state-owned, were highly decentralized. While overseen by boards of directors named by distinct government and business organizations, the administration of day-to-day port operations was largely contracted out to private companies. Those companies built port infrastructure and, in some cases, maintained their own terminals to offload and process shipping containers (Carcamo Miranda Reference Carcamo and Iliana2018, 75–85).

Less than a month after the exposure of the Moreno Network, President Arzú dismissed all port company authorities and named auditors to identify sources of corruption and propose remedies. Indeed, the early auditing efforts indicated that port officials also had played a key role in “the falsification of documents, which served to alter the declared merchandise or note lesser quantities” to defraud the tax administration (Siglo Veintiuno 1996f). Removing port company leadership largely targeted high-ranking military officers, who had come to occupy key posts in the port system as the counterinsurgent campaign escalated (López and Hernández S. Reference Hernández1996). The head of the Quetzal Port Company was former senior navy officer Capt. Mario Enrique García Regás, and at the Santo Tomás de Castilla Port, the head of the board of directors was Marco Antonio González Taracena, a former minister of defense. Both were removed following the intervention decree. Though these previously dominant actors did not face criminal prosecution for their role in the Moreno Network scheme, the dominant social and political blocs with a stake in the fraudulent customs procedures were displaced from the official government sphere through Arzú administration actions.

The Survival of the Predatory Informal Rules

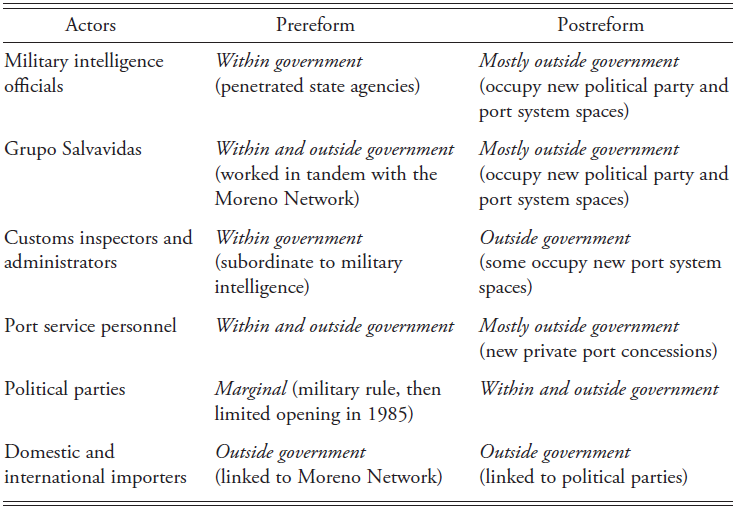

Efforts to purge the Guatemalan state of those groups that formed the dominant authoritarian-era distributional coalition, however, had a limited effect on the predatory informal rules in the customs administration. The military, political, and economic actors that coalesced around the fraudulent customs activities seized new channels on the margins of the formal state sphere—spaces that were, in large part, facilitated by Guatemala’s nascent political party system and by greater economic liberalization. These diverse sectoral interests thus adapted to the new posttransition environment and preserved the wartime distributional coalition by straddling the public and private spheres (see table 1). These extra- or semistate channels of political and economic influence allowed the authoritarian-era distributional coalition to maintain impunity for the illicit customs activities, locate strategic allies in the government, and adjust the fraudulent procedures in the postreform landscape.

Table 1. Adaptation of the Distributional Coalition Before and After State Reforms

Guatemala’s return to elected, civilian rule and its process of political liberalization offered new avenues of influence through the party system. The previously dominant counterinsurgent actors who had devised and enforced the customs fraud scheme quickly occupied these new semistate spaces, which allowed them to uphold the predatory informal rules from outside the government. We see this dynamic through one political party in particular, the right-wing, populist Guatemalan Republican Front (Frente Republicano Guatemaltecto, FRG). The FRG, which became the electoral vehicle of former dictator Ríos Montt, rose to prominence by the end of the 1990s. When the Constitutional Court barred Ríos Montt from seeking the presidency because of his participation in the 1982 coup that brought him to power, Alfonso Portillo, a congressional deputy from Guatemala’s Christian Democratic Party, became the FRG’s candidate in 1999. Garnering wide support across Guatemala’s countryside, Portillo won and assumed office in January 2000, with the FRG forming the largest legislative bloc.

Having consolidated its hold on political power, the FRG constituted a new avenue through which the architects of the Moreno Network adapted and preserved the wartime distributional coalition and the informal rules governing customs fraud. In the words of Peacock and Beltrán (Reference Peacock and Beltrán2003, 33), the FRG, which controlled the executive and legislative branches, was “an important vehicle for consolidating the political authority of hidden powers … that wielded great influence, … further weakening the government’s ability to fight against corruption and impunity” (emphasis in original). Among the past figures who again rose to prominence with Portillo and the FRG were three former military intelligence officials discharged from the armed forces in late 1996 due to their links with the Moreno Network: the architect of the SEM and its first chief, retired general Francisco Ortega Menaldo; and former officers Jacobo Salán Sánchez and Napoleón Rojas Méndez. Though Ortega Menaldo never formally occupied a government position during the Portillo administration, experts indicate that he was one of Portillo’s top advisers (Peacock and Beltrán Reference Peacock and Beltrán2003, 16; Font Reference Font2002). Similarly, Salán Sánchez served as the de facto head of the EMP—a unit Portillo had vowed to dismantle on taking office. Rojas Méndez was a campaign security adviser to Portillo and eventually served as second-in-command of presidential security during Portillo’s presidency (Reyes Reference Reyes2004).

Thus, while the FRG allowed the displaced military blocs to eventually regain access and dominance in the state sphere, they utilized new extragovernmental political channels to do so. In the words of one former military intelligence officer, actors like Ortega Menaldo, Salán Sánchez, and Rojas Méndez “left the army but when Portillo returned, they entered again, but now as part of an external structure” (Intelligence Agents 2017). As another former official put it, the ex-intelligence elites “returned to the orbits of influence surrounding presidential power and customs” (Politician/Executive Official 2017). Despite the primarily informal roles the intelligence officers played, unofficial access to state power ensured their influence in naming personnel and moving state funds, which were funneled to the EMP (Peacock and Beltrán Reference Peacock and Beltrán2003, 24, 41).

Importantly, the former military intelligence elites sought to shore up the predatory customs procedures by naming SAT officials who would do their bidding—by placing criminal operators on the “inside.” Though early SAT officials reportedly refused to bow to political pressures (Trejo Reference Trejo2001), in 2002, Portillo named Marco Tulio Abadío as SAT superintendent, a move that led to the “destruction of [the institution] as we knew it,” in the words of one economist (Economist 2017). Abadío, who had served as head of the General Comptroller’s Office during the Arzú government, became superintendent of the SAT through an apparent accord with the retired military elites seeking to control the customs administration once again (Finance Official 2017). In March 2004, he was indicted for embezzling more than $5.5 million through a sophisticated scheme of shell companies, which he had transposed from the General Comptroller’s Office (Palma Reference Palma2004). Even with the reconfiguration of political power within the state, the ex-military elites who oversaw the Moreno Network preserved the wartime distributional coalition by maneuvering on the outside to locate strategic allies inside.

Beyond co-opting new spaces in Guatemala’s more competitive political landscape, the wartime distributional coalition also sought alternative economic spaces afforded through market reforms. This was particularly the case with Guatemala’s port system, which, along with numerous state-owned enterprises, experienced rapid privatization during the Arzú government.Footnote 7 While Guatemala’s major ports had included both public and private features since their inception, the intervention and auditing processes undertaken after the Moreno Network revelations generated a host of new private concessions related to port infrastructure and services. These concessions provided new avenues for previously dominant actors to maintain the predatory informal rules governing customs fraud by adjusting fraudulent procedures and keeping state authorities out of customs-processing activities.

For instance, following the October 1996 intervention in the Santo Tomás de Castilla port, the government awarded about $8 million in new contracts to Equipos del Puerto, a private firm created by former employees of the state-owned port company’s Department of Containers. Equipos received the concessions without a competitive bidding process (El Periódico 2000). The new, privatized mechanisms of moving imports were thus in the hands of the same actors who once had controlled them from within the state.

Furthermore, while the package of posttransition reforms sought to vest authority in a modernized, independent tax administration—the SAT—the increasing privatization of port services led to new autonomous pockets, to which tax authorities were denied entry. As one customs inspector remarked, “the different firms in the port were in agreement not to give all of the information on shipping containers to the SAT. And so there were a lot of containers that they would refer to as ‘fly’ … in that there never existed any register of the container…. It was as if it never entered the country” (Customs Inspectors 2017). The method described here as “fly” is virtually identical to the shipping container “disappearances” that occurred during the Moreno Network era.

Another example of the reconstitution of the wartime distributional coalition following formal bureaucratic reforms can be seen in new private port infrastructure projects, like the Inter-Oceanic Corridor, or “dry canal,” which sought to connect the Atlantic-based Santo Tomás de Castilla and Pacific-based Quetzal ports. Among those spearheading the project was ex-colonel Mario Roberto García Catalán, one of nine military officials discharged following the Moreno Network investigations (El Gráfico 1996). In a 2011 interview, García Catalán’s cousin and partner in the project, former army lieutenant Guillermo Catalán, indicated that the duo’s military ties facilitated the concession (Arce Reference Arce2011). Though the Inter-Oceanic Corridor remains under development, it illustrates how well-connected former military elites seized new economic spaces from outside to maintain their influence.

By contrast, the 2015 La Línea revelations marked the reentry of the wartime distributional coalition into the official state sphere to a much greater extent. The coalition underwriting La Línea’s illicit customs activities mirrored the wartime alliance between retired military officials, tax authorities, private sector elites, and organized criminal elements, yet those spearheading the scheme did so from the executive branch more directly. President Pérez Molina and Vice President Baldetti were at the helm of the “internal structure,” represented by Baldetti’s private secretary, Juan Carlos Monzón, an ex–army captain discharged for his suspected ties to a car theft ring run by Alfredo Moreno’s relatives (Barreto Reference Barreto2015).

From outside the government, Salvador Estuardo González, president of one of Guatemala’s major publishing companies, coordinated the financial aspects of the illicit customs operations, overseeing the distribution of profits (Barreto Reference Barreto2016). In addition, those in the upper echelons of the criminal structure strategically named SAT officials like Superintendents Carlos Muñoz and Omar Chacón and customs head Claudia Méndez to ensure that the staffing of inspectors permitted the illegal customs duty adjustments to go on unimpeded (Barreto Reference Barreto2015). While the modalities of customs fraud under La Línea were virtually identical, the distributional coalition underwent another period of adaptation and accommodation as it again gained a greater foothold in official government circles.

Assessing Alternative Mechanisms

Overall, this process-tracing analysis illustrates that informal institutional persistence is driven by the adaptation of the authoritarian-era distributional coalition on the margins of state power. Though previously dominant military and political blocs were displaced from the state sphere, they used new extra-state channels to wield continued influence by adapting the predatory informal rules, securing impunity, and locating strategic allies on the inside. This analysis, however, also considered two other potential mechanisms: the manipulation of formal institutional reforms and the endurance of collective understandings that rendered the predatory informal rules “appropriate” or “legitimate.” However, these explanations find less support in this particular case.

Observably, the first alternative mechanism—incumbent manipulation of the timing or enforcement of formal institutional changes—would be reflected in Arzú administration attempts to stall reform efforts or impede the enforcement of new SAT provisions, which this analysis does not bear out. After the Moreno Network revelations, the sitting government acted swiftly to remove implicated political and military officials and undertook a fairly robust, internationally backed process to build a new tax entity, which exceeded Peace Accord provisions. Instead of waiting for the completion of the investigations, the Arzú government decided to dismantle the criminal structure to disrupt the predatory informal rules in Customs. As then minister of foreign affairs Eduardo Stein confirmed, “The decision of President Arzú was to proceed immediately to prevent [the accused] from destroying evidence and maintaining access to these levels of power” (Presidencia de la República 1997, 315).

Of course, an important critique of the Arzú administration’s approach was that criminal prosecutions for those involved—save for Alfredo Moreno himself and Salvadoran contrabandista Santos Hipólito Reyes—remained off the table, weakening the potential deterrent effect of judicial sanctions, as one executive official noted (Politician/Executive Official 2017). The commercial “clients” of the Moreno Network were barely even investigated, according to an ex-intelligence agent, because of the narrow national security focus (Intelligence Agents 2017). And although discharged, the military intelligence elites evaded criminal prosecutions, although Salán Sánchez, Rojas, and Portillo were eventually convicted for corruption and embezzlement carried out in the early 2000s (see Peacock and Beltrán Reference Peacock and Beltrán2003). While it is hard to assess the potential effects of broader judicial sanctions, efforts to displace high-ranking officials and the rapid implementation of SAT reforms largely contradict this alternative mechanism.

The second potential mechanism—collective understandings of the predatory informal rules as “appropriate”—also finds little support in this analysis. If this mechanism plausibly accounted for informal institutional persistence, we would expect to see the continuation of wartime views that military elites “had the right to do these [corrupt] things” because of their heroic acts in defense of the country (Intelligence Agents 2017), or that such behavior was seen as socially permissible among customs inspectors and administrators. Instead, the wartime justification for the customs fraud scheme fell away with the end of the armed conflict. Moreover, SAT reforms sought to combat collective understandings of the predatory informal rules as “normal” or “legitimate” by purging the bureaucracy and vetting new personnel. According to executive officials, the government’s only option was “to remove this function from Public Finance employees … since, to date, the authorities have not been able to locate the employees that engage in acts of corruption, given the sophisticated mechanisms that they utilize” (El Periódico 1998). Before the SAT’s creation, officials forged a “mutually satisfactory” agreement with the unions to create a voluntary retirement program. In the end, there was an exodus of some two thousand customs employees. Just 1.25 percent of previous personnel remained in their posts (Executive Official 2017; Customs Inspectors 2017).

To fill the void, the SAT contracted and trained brand-new personnel, who met a series of more rigorous educational standards. Conversations with those involved in the process, as well as members of the first cohort of new customs inspectors, suggest that these vetting procedures instilled a new sense of public duty—a new collective understanding of how tax administration personnel ought to behave. In the words of one former customs inspector hired with the creation of the SAT, those entering the new bureaucratic posts “were very good, they had principles” (Customs Inspectors 2017). As a result, the corrupt agents in the tax administration were now “in the minority.”

But despite the best intentions of the SAT designers, the training and resources were modest. According to one former inspector, “we were only given very basic training, and so, above all, we were learning as we went. But the intention to do things correctly was there.” In spite of the challenges as the SAT remained “in diapers,” those in the new agency “were more transparent … so the SAT began to advance little by little” (Customs Inspectors 2017). In sum, though new SAT personnel faced clear obstacles, there is little evidence that the normative acceptance of the predatory informal rules drove their survival.

Conclusions and Implications

The roughly 20-year period between the Moreno Network and La Línea revelations illustrates that predatory informal institutions may succeed in outlasting bureaucratic reforms when the broader distributional coalition, with a vested stake in the previous order, adapts to and exerts influence from new political and economic spaces. In other words, the decadeslong distortion of Guatemala’s customs administration was not necessarily the result of insufficient formal institutional reforms, but of inattention to where the targets of reforms would go and what they would do in the aftermath. In the words of one former politician and businessman, “it’s that these people [previously powerful authoritarian figures] are there, and they have time, they have space … and they are more creative than the rest. They persist, they live in the shadows, and they wait for an opportunity to return, for someone to open the door” (Politician/Executive Official 2017).

Through this lens, the case of Guatemala’s tax and customs administration holds important implications for state reform, both theoretically and empirically. Broadly, the theoretical insights derived here illustrate how predatory informal rules outlast—and may deepen amid—conventional bureaucratic reform efforts, however well resourced and well intentioned, because they fail to account for how the remnants of authoritarian-era coalitions find new venues beyond the formal state sphere through which to piece themselves back together. The persistence of predatory informal rules occurs through the adaptation of the authoritarian-era political, military, and economic blocs to new spaces of influence on the margins of formal state power—arenas that allow them to distort decisionmaking, maintain impunity, and shield illicit activities from new controls. What previous theories miss is not that formal institutions can coexist alongside predatory informal rules, but how the latter can flourish in the face of targeted eradication efforts. Governance reforms premised on dramatic institutional overhaul may exacerbate the challenges of identifying and neutralizing these new, extra-state channels of influence.

These insights can illuminate dynamics in other Latin American transition settings in which political and economic reforms have failed to uproot or have even deepened predatory informal rules. For example, these dynamics extend beyond tax and administrative institutions and into the security sector, where authoritarian-era rules governing extrajudicial killing in places like Brazil, Argentina, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Colombia have outlasted police and military reforms (Brinks Reference Brinks2007; Silva Ávalos Reference Silva2014; Fernández Reference Fernández2011; Casey Reference Casey2019). Understanding the diverse sectoral interests with a stake in these predatory institutional arrangements and how they have adapted to formal institutional changes may be the key to uncovering the mechanisms by which such illicit procedures have persisted despite repeated attempts to strengthen the rule of law in these contexts.

These insights also shed light on postconflict settings and the obstacles to peacebuilding reforms in particular. The imperative of combating an internal enemy provides counterinsurgent actors extraordinary discretion to introduce new predatory rules within the state; however, in myriad contexts, including the Balkans, Liberia, and Afghanistan, periods of postwar reform further entrench pernicious wartime activities (Andreas Reference Andreas2008; Reno Reference Reno and Zaum2012; Barma Reference Barma2016). Mapping the postwar displacement of counterinsurgent actors and the new channels through which they exercise influence, as this article does, can shed light on how modes of wartime predation adapt to the strictures of formal peace over the long term.

In addition, these conclusions offer lessons for policy efforts to combat corruption and criminality—powerful sources of conflict and fragility in the eyes of the international community (World Bank 2011). In Central America, the now-defunct CICIG and the ousted OAS-led Mission to Support the Fight Against Corruption and Impunity in Honduras (MACCIH) exposed criminal structures embedded within the state, while El Salvador proposed creating a similar entity to investigate and prosecute high-level corruption (Call Reference Call2019). Yet given the complex and fluid networks that underwrite such activities, a one-size-fits-all approach to international anticorruption assistance is unlikely to yield lasting change. As such missions seek to combat state criminality, they must also remain attentive to the blurred boundaries between formal and informal spheres and the fluidity with which diverse predatory political and economic actors traverse them.