Introduction

ENT surgeons are at high risk of work-related musculoskeletal disorders during their careers, with a reported prevalence between 47 and 90 per cent.Reference Babar-Craig, Banfield and Knight1–Reference Boyle, Fitzgerald, Conlon and Vijendren7 This appears consistent with, if not higher than, what has been reported with other surgical specialties and certainly higher than that reported in the general working population across Europe.Reference Schneider, Irastorza and Copsey8–Reference Marciano, Mattogno, Codenotti, Cocca, Fontanella and Doglietto15 Work-related musculoskeletal disorders are conditions that arise over time as a consequence of, or made worse by, repeated actions or exposures associated with any particular occupation and can include tendonitis and carpal tunnel syndrome as well as musculoskeletal pain, swelling, stiffness, restricted movement, and fatigue.

The UK Health and Safety Executive particularly notes that these disorders are more common with prolonged repetitive work, with uncomfortable or awkward working postures, with sustained or excessive force, with carrying out a task without suitable rest breaks and working with powered tools.16 Considering ways to reduce or eliminate the risks of work-related musculoskeletal disorders is advocated by the UK Health and Safety Executive.

Psychosocial risk factors may also be at play in making people more likely to develop and report work-related musculoskeletal disorders, such as high workloads and tight deadlines. Risk factors for the ENT surgeon include poor posture and ergonomic strain combined with routine and repetitive use of specialist equipment in clinics and operating theatres, including microscopes, endoscopes, loupes and headlamps, which can contribute to excessive strain and a higher risk of developing work-related musculoskeletal disorders.Reference Rimmer, Amin, Fokkens and Lund17–Reference Rodman, Kelly, Niermeyer, Banks, Onwuka and Mason23 These risks can be categorised into equipment-based and surgeon and patient position-based risk factors as a recent systematic review has shown.Reference Maxner, Gray and Vijendren24

The overall cost of work-related musculoskeletal disorders in the European Union is estimated to be between 0.5 per cent and 2 per cent of gross national product.Reference Hoe, Urquhart, Kelsall and Sim25 Work-related injury in ENT surgeons leads to pain, discomfort, time off work, early retirement and detrimental effects on stamina, sleep, relationships, concentration and surgical speed.Reference Vijendren, Yung, Sanchez and Duffield4,Reference Howarth, Hallbeck, Mahabir, Lemaine, Evans and Noland21,Reference Soueid, Oudit, Thiagarajah and Laitung26 These problems can start as early as the first few years of ENT training.Reference Ho, Hamill, Sykes and Kraft27

Despite the impact of work-related musculoskeletal disorders and a legal requirement in the UK for employers to carry out a risk assessment and protect workers from injury, only up to 24 per cent of ENT surgeons have received training or education in how to prevent such injuries and only 31 per cent are aware of ergonomic principles designed to prevent musculoskeletal injury.Reference Rodman, Kelly, Niermeyer, Banks, Onwuka and Mason23,Reference Cavanagh, Brake, Kearns and Hong28,Reference Vaisbuch, Aaron, Moore, Vaughan, Ma and Gupta29 We systematically examined the evidence for interventions to prevent work-related musculoskeletal disorders in ENT surgeons and trainees.

Materials and methods

The authors conducted a systematic literature search between 1974 and 8 June 2021 using Ovid to search Medline and Embase databases. A Population, Interventions, Comparison, Outcome search strategy using specific parameters and keywords was adopted to identify relevant articles as shown in Table 1. Duplicates were removed using the automated function within Ovid.

Table 1. Population, Interventions, Comparison, Outcome search strategy

*Parameters of our search used to identify the population of interest are shown below, each of which was formed of multiple keywords linked with the operator ‘OR’. These three parameters were then combined using the operator ‘AND’ to create our final search criteria. The wildcard character ‘*’ was used to account for multiple derivations of the intended keyword. (1) ENT or otolaryngog* or otolog* or rhinolog* or laryng* or endoscop*; (2) occupation* or work-related or ergonomic*; (3) strain* or symptom* or disorder* or discomfort* or problem* or pain* or injur* or complain* or stress* or disease* or ill* or musculoskeletal or neck or back or cervical

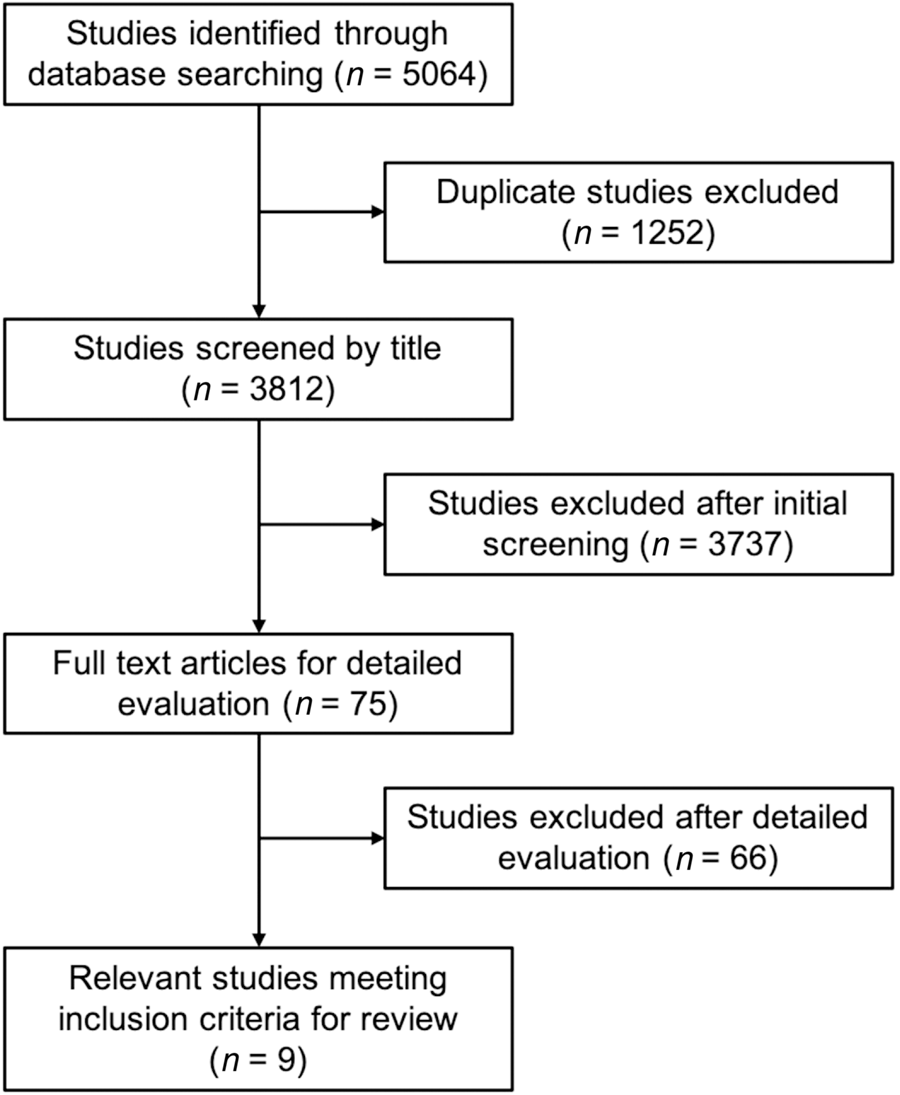

One author (BS) screened 3812 unique articles by title relevance alone, which identified 75 potential articles. Two authors (BS and MV) independently reviewed the abstracts. Predetermined inclusion criteria included any trial of any intervention to prevent musculoskeletal disorders in ENT surgeons in any clinical setting. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses were excluded.

The full-text of the selected studies was then comprehensively reviewed for their setting, interventions, participants, outcome measures and results. The search was summarised in a flowchart following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses guidelines (Figure 1). One author (BS) assessed the level of evidence of the selected studies with respect to the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine evidence table and assessed the risk of bias using the Robins-I tool.30,Reference Sterne, Hernán, Reeves, Savović, Berkman and Viswanathan31 A second author (MV) then verified these measures with any discrepancy being discussed between the two authors before an agreement was reached and published (Table 2).

Fig. 1. Flowchart of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses methodology.

Table 2. Studies implementing an intervention to prevent work-related musculoskeletal disorders within ENT practice

Results

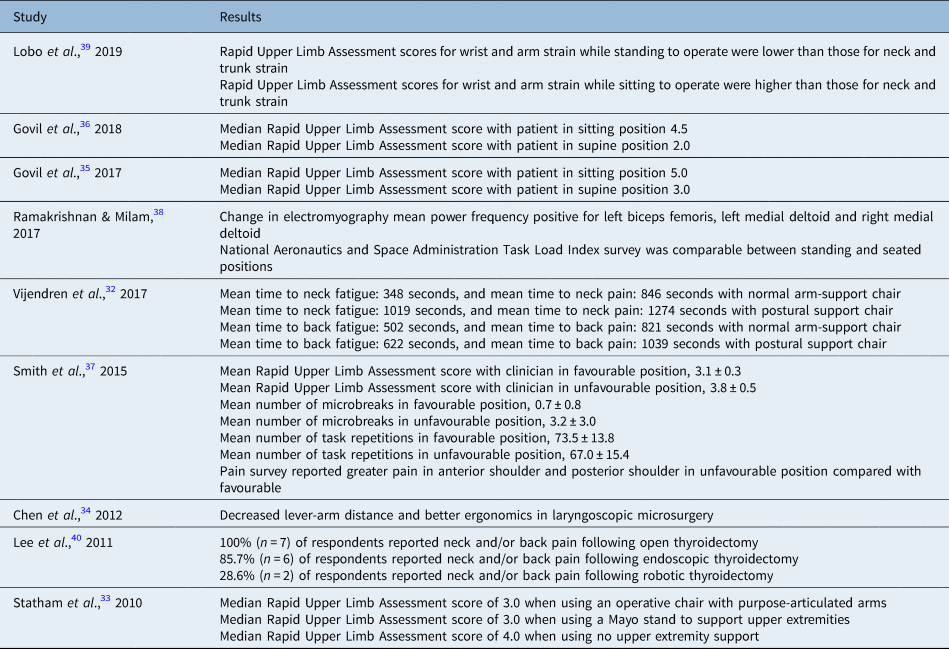

Nine studies were included with a total of 51 participants (50 ENT surgeons or trainees and 1 nurse; see Table 2). Seven prospective cohort studies and two case series were identified. No randomised, controlled trials met inclusion criteria. Quantitative meta-analysis was not possible because of heterogeneity between studies, so a descriptive analysis was performed (Table 3).

Table 3. Results of studies implementing an intervention to prevent work-related musculoskeletal disorders within ENT practice

Of the nine studies included in our review, four were based in a simulated operating theatre setting, two were in an operating theatre setting, two were in a simulated clinic environment and one was in a clinic. Five studies utilised Rapid Upper Limb Assessment scores (ranging from 1 to 7 with higher scores indicating higher risk of ergonomic stress) as primary outcome measures. Other outcomes as measures of early symptoms of work-related musculoskeletal disorders included a change in surface electromyography, prevalence of neck and back pain, and time of onset of neck and back fatigue and pain.

Equipment-based interventions

Three studies investigated novel equipment. Vijendren et al. (2017) investigated a modified chair with sternal support to maintain a neutral position of the cervical and thoracic spine along with a cushion to rest the forehead on to reduce the load on the cervical joints during clinic procedures.Reference Vijendren, Devereux, Kenway, Duffield, Van Rompaey and van de Heyning32 Outcome measures were time to fatigue and pain in the neck and back as well as surface electromyography as a measure of muscular activity as a percentage of the resting value for each participant. The authors reported an increase in time to neck fatigue (p < 0.05) and neck pain (p < 0.05) when using the ergonomic chair compared with a standard operating chair but no statistically significant delay in back fatigue (p = 0.11) or back pain (p = 0.21). There was no correlation with surgical experience. They also demonstrated significant reductions in surface electromyography from the neck (p < 0.05) and back (p < 0.05) when using an ergonomic chair compared with a standard operating chair.

Statham et al. (2010) compared use of a standard design operative chair with articulated arm support against resting arms on a Mayo stand and without any arm support during simulated microlaryngoscopy.Reference Statham, Sukits, Redfern, Smith, Sok and Rosen33 Outcome measures of Rapid Upper Limb Assessment scores were higher, in general, for participants when no upper extremity support was used; statistical significance was not calculated. The degree of neck flexion was also lowest when using an operative chair with purpose-articulated arms.

Chen et al. (2012) investigated a head-mounted microscope and compared it with a stand-mounted microscope with a single ENT surgeon conducting five phonomicrosurgical procedures.Reference Chen, Dailey, Naze and Jiang34 They noted that the head-mounted microscope substantially reduced the working distance between operator and operating field. This in turn reduces the arm lever and the force exerted by muscles, thereby delaying musculoskeletal fatigue.

Patient positioning

Two studies by the same authors investigated ergonomic stress on clinicians performing clinic otological procedures in the clinic with patients in either an upright seated position or supine. Govil et al. (2017 and 2018) looked to measure Rapid Upper Limb Assessment scores by observing joint positions of clinicians while performing cerumen removal using a wall-mounted microscope.Reference Govil, Demayo, Hirsch and McCall35,Reference Govil, DeMayo, Hirsch and McCall36 The authors showed a reduction of 2.0 points (p < 0.05) on the Rapid Upper Limb Assessment scoring system in their first study when mock patients were supine versus sitting, and one year later demonstrated a similar reduction of 2.5 points (p < 0.05) in another study involving 24 genuine patients.

Clinician positioning

Three studies looked into positioning of the clinician. Smith et al. (2015) randomly assigned participants to perform simulated microlaryngoscopy in either a designated favourable (laryngoscope angle of 40o from the horizon, 0–10o neck flexion and with the addition of forearm support at a comfortable height for each surgeon) or unfavourable (laryngoscope angle of 60o, 20–30o neck flexion, and no forearm support) positions as based on data from Statham et al. (2010).Reference Smith, Trout, Sridharan, Guyer, Owens and Chambers37 Doctors allocated to the ergonomically favourable position demonstrated reduced Rapid Upper Limb Assessment scores (p < 0.05), fewer microbreaks (p < 0.05), fewer task repetitions (p < 0.05), less self-reported pain (p < 0.05) and better usability (p < 0.05). There were no significant changes to relevant electromyography metrics.

Ramakrishnan and Milam (2017) compared fatigue for standing and sitting positions when a single surgeon performed simulated bilateral functional endoscopic sinus surgery in eight cadaver heads.Reference Ramakrishnan and Milam38 They found that there were many confounding factors limiting direct comparison; however, electromyography mean power frequency improved for the left biceps femoris and bilateral medial deltoids in the seated position compared with the standing position, representing less fatigue. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration Task Load Index survey was comparable between the two positions, although tasks were more frustrating in the seated position. A physical discomfort questionnaire was also completed with statistically significant worsening discomfort seen in the hamstrings, right calf and eyes on standing.

Lobo et al. (2019) also investigated ergonomics during simulated cadaveric endoscopic sinus surgery.Reference Lobo, Anuarbe, López-Higuera, Viera, Castillo and Megía39 Five of six participants adopted a standing position while one preferred the use of a seated position. Overall Rapid Upper Limb Assessment scores were lower for the seated than the standing position. Rapid Upper Limb Assessment scores for wrist and arm strain while standing to operate were lower than those for neck and trunk strain. The reverse was true for the one surgeon who was seated, with higher Rapid Upper Limb Assessment scores for wrist and arm strain compared with those for neck and trunk. There was no significant association between years in practice and Rapid Upper Limb Assessment score.

Operative technique

Only one study looked into operative technique as an ergonomic intervention. Lee et al. (2011) conducted a survey evaluating musculoskeletal discomfort while performing thyroidectomy, primarily assessing the difference in ergonomics between robotic, endoscopic and open thyroidectomy techniques.Reference Lee, Kang, Jung, Choi, Yun and Nam40 When asked to rank the three approaches based on the pain and discomfort associated with each, most respondents selected the endoscopic approach as causing the most pain.

Discussion

Despite the high prevalence of work-related musculoskeletal disorders in ENT surgeons, our systematic review identified very little evidence on preventative interventions. The few studies identified were of low quality and included a small number of participants with a variety of outcome measures. However, the limited evidence available suggests that optimised patient positioning, clinician posture and the use of supportive equipment may reduce ergonomic strain and symptoms associated with work-related musculoskeletal disorders such as neck and back pain.

Five of the nine included studies measured Rapid Upper Limb Assessment scores as an outcome measure for their intervention. Rapid Upper Limb Assessment scores are a validated numerical measure of the risk of neck, trunk and upper limb strain associated with occupational ergonomic positioning; they are calculated by measuring observed joint angles of various sites of the body, with a higher score indicating greater risk of strain.Reference Mcatamney and Corlett41 This scoring system has been used successfully in a number of other studies looking at surgical ergonomics outside of otolaryngology, including laparoscopic, plastic and dental surgery.Reference Park, Kim, Roh and Namkoong42–Reference Li, Baber, Macdonald and Godwin45 Differences in the measurement of Rapid Upper Limb Assessment scores made comparison between studies difficult. For instance, Govil et al. (2018) used an observer in the room at the time of procedure whereas Smith et al. (2015) measure data from static photography taken at the end of each simulated test session.Reference Govil, DeMayo, Hirsch and McCall36,Reference Smith, Trout, Sridharan, Guyer, Owens and Chambers37 The resulting Rapid Upper Limb Assessment score may be affected by the angle and aspect of the relevant photograph, which limits the generalisability of Rapid Upper Limb Assessment scores measured in different ways across studies.

Principles and interventions proposed outside of ENT surgery may be worth considering. Preventative ergonomic programmes involving physical exercises and demonstrations have shown good outcomes and may even be delivered virtually.Reference Giagio, Volpe, Pillastrini, Gasparre, Frizziero and Squizzato46,Reference Rosenblatt, McKinney and Adams47 One study examined the effect of the Alexander Technique, a psychophysical re-education of the body, on posture in a cohort of laparoscopic surgeons.Reference Reddy, Reddy, Roig-francoli, Cone, Sivan and Defoor48 A Cochrane review found evidence that short breaks reduced upper limb discomfort in office workers.Reference Hoe, Urquhart, Kelsall, Zamri and Sim49 These short breaks or ‘microbreaks’ may offer similar benefits for surgeons. However, there is still clearly a need for further research, with other recent systematic reviews into interventions to prevent work-related musculoskeletal disorders in plastic surgeons and neurosurgeons also concluding this to be an under-investigated topic.Reference Epstein, Tran, Capone, Lee and Singhal11,Reference Marciano, Mattogno, Codenotti, Cocca, Fontanella and Doglietto15

• ENT surgeons are at high risk of work-related musculoskeletal disorders

• Work-related injury can begin in the first few years of training and lead to a range of problems

• A literature search screened almost 4000 articles for possible interventions for work-related musculoskeletal disorders in ENT surgeons

• Only nine studies examining such interventions for ENT surgeons, all of low-quality evidence, currently exist

• The literature suggests that optimal positioning of patients and clinicians during ENT procedures may reduce work-related strain

• Further research in this area is required to produce high-quality evidence and guidelines

Finally, employers may also be under legal duty to put into place certain measures for their workers’ health. In the UK, the Health and Safety Executive sets out a number of recommendations to employers to carry out a thorough risk assessment to protect workers from upper limb disorders in the workplace.16 Following review, their suggestions include many factors already proposed in the surgical literature, such as optimising equipment height, reducing repetitive actions and changing posture for comfort depending on the exact tasks identified as high risk.

Conclusion

Evidence for interventions preventing work-related musculoskeletal disorders in ENT surgeons is limited in its availability, quality and scope. Low-quality evidence suggests that optimal positioning of patients and clinicians during ENT procedures may reduce work-related strain. Further research in this area is needed, with the aim of producing high quality evidence-based guidance to surgeons and trainees.

Competing interests

None declared