Introduction

In Australia, older people, aged 65 or over, make up 15 per cent of the population and are expected to account for more than 20 per cent of the population by 2050 (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2018). Globally, the older population is the fastest growing cohort, at 3 per cent per year, and all regions of the world except Sub-Saharan Africa are expected to have nearly a quarter or more of their population aged over 60 by 2050 (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs and Population Division, 2017). Worldwide, studies report that most older people wish to age in place, that is, to continue living safely and independently in their current residence in the community, rather than in institutional care (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2013; National Association of Area Agencies on Aging, National Council on Aging and UnitedHealthcare, 2015; Stepler, Reference Stepler2016). This preference is not only because of an emotional attachment to home, but also a desire to remain connected to a familiar community and services, retaining autonomy and independence, with associated life satisfaction and quality of life (Olsberg and Winters, Reference Olsberg and Winters2005). There are many factors that facilitate ageing in place, including personal characteristics such as resilience, adaptability and independence; and individual, environmental and services factors, such as health, information, assistance, finances, physical and mental activity, company, transport and safety (Grimmer et al., Reference Grimmer, Kay, Foot and Pastakia2015). Ageing in place also has economic benefits compared to institutional care (Chappell et al., Reference Chappell, Dlitt, Hollander, Miller and McWilliam2004). In combination, these factors suggest the need for community services to support older individuals to remain living independently in the community.

As people age, they are more likely to live alone; in Western society, more than one in four people aged 65 and over live alone (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2015; United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs and Population Division, 2017). The number of Australians living alone is projected to double by 2026, in line with predicted population growth and increases in life expectancy (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2006). Whilst for some, living alone may not be the desired living arrangement following relationship breakdown, or death or relocation of a spouse; for others it can be an active decision that promotes personal values, including enhanced privacy, independence, freedom, self-reliance and a reduction in demands on others (de Vaus and Qu, Reference de Vaus and Qu2015b).

Despite positive reasons for ageing in place, concerns around the safety and capability of older adults who live alone permeate almost all narratives surrounding the issue in both academic and public discourse (Iliffe et al., Reference Iliffe, Tai, Haines, Gallivan, Goldenberg, Booroff and Morgan1992; Kharicha et al., Reference Kharicha, Iliffe, Harari, Swift, Gillmann and Stuck2007). Being unable to receive timely help when needed is a real fear for many older adults living alone, as well as their families (Huang and Lin, Reference Huang and Lin2002). This concern is not unfounded, as the mortality rate for those who injure themselves and cannot call for help is as high as 28 per cent (Gurley et al., Reference Gurley, Lum, Sande, Lo and Katz1996; Holland and Rodie, Reference Holland and Rodie2011). Further, older adults living alone have an increased risk of poor health and functioning, falls and difficulties with activities of daily living, compared to those living with others (Kharicha et al., Reference Kharicha, Iliffe, Harari, Swift, Gillmann and Stuck2007). Individuals living alone are also faced with additional social difficulties, including losses in their support network (e.g. death of partner or friends), a perceived lack of social support resources and companionship, loss of previous social roles, and a decrease in functional abilities that can make social engagement more challenging (Adams and Blieszner, Reference Adams and Blieszner1995; Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Fung and Chan2008). These social factors, along with increasing functional disability and physical illness, may affect the psychological wellbeing and mental health of the older person living alone (Asakawa et al., Reference Asakawa, Koyano, Ando and Shibata2000; Savikko et al., Reference Savikko, Routasalo, Tilvis, Strandberg and Pitkala2005; Lucas, Reference Lucas2007; Richard et al., Reference Richard, Rohrmann, Vandeleur, Schmid, Barth and Eichholzer2017).

Given the potential issues facing individuals who live alone, ensuring access to appropriate and effective services to support independence and wellbeing is of high priority. While supply of effective and appropriate care is an essential feature of evidence-based practice, demand-side barriers to access may exclude some populations from the benefits of effective and appropriate care (Ensor and Cooper, Reference Ensor and Cooper2004). Penchansky and Thomas (Reference Penchansky and Thomas1981) developed the Theory of Access (recently updated by Saurman, Reference Saurman2015) which outlines the six dimensions of service access (see Table 1). These independent yet interconnected dimensions revolve around a simple concept; the better the service fits the needs of the user, the better the access (Saurman, Reference Saurman2015). Despite the enduring nature of this theory, many services continue to treat their users as a homogenous group, without considering those in need of assistance who are not optimally accessing services.

Given the importance of these barriers to service use, interventions to optimise the health, wellbeing and quality of life of older people living alone should be developed and evaluated for their accessibility as well as against clinical effectiveness. Building this evidence base is a necessary first step in designing services that will allow older people living alone to age in place. In this context, we aimed to identify and synthesise the evidence regarding the effectiveness of previously implemented interventions to improve the health, wellbeing and quality of life of older people who live alone. Based on findings from included studies, we then assessed each intervention against the six dimensions of service access: accessibility, availability, acceptability, affordability, adequacy and awareness. This systematic review builds on previous reviews which focused on a narrower set of interventions (interventions targeting social isolation in older people) than included in the present study (Findlay, Reference Findlay2003; Cattan et al., Reference Cattan, White, Bond and Learmouth2005; Dickens et al., Reference Dickens, Richards, Greaves and Campbell2011; Masi et al., Reference Masi, Chen, Hawkley and Cacioppo2011; Cohen-Mansfield and Perach, Reference Cohen-Mansfield and Perach2015; Gardiner et al., Reference Gardiner, Geldenhuys and Gott2018).

Methods

We conducted and reported this systematic review in accordance with the PRISMA Statement (Moher et al., Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009). This review was registered in PROSPERO (2017 CRD42017053298).

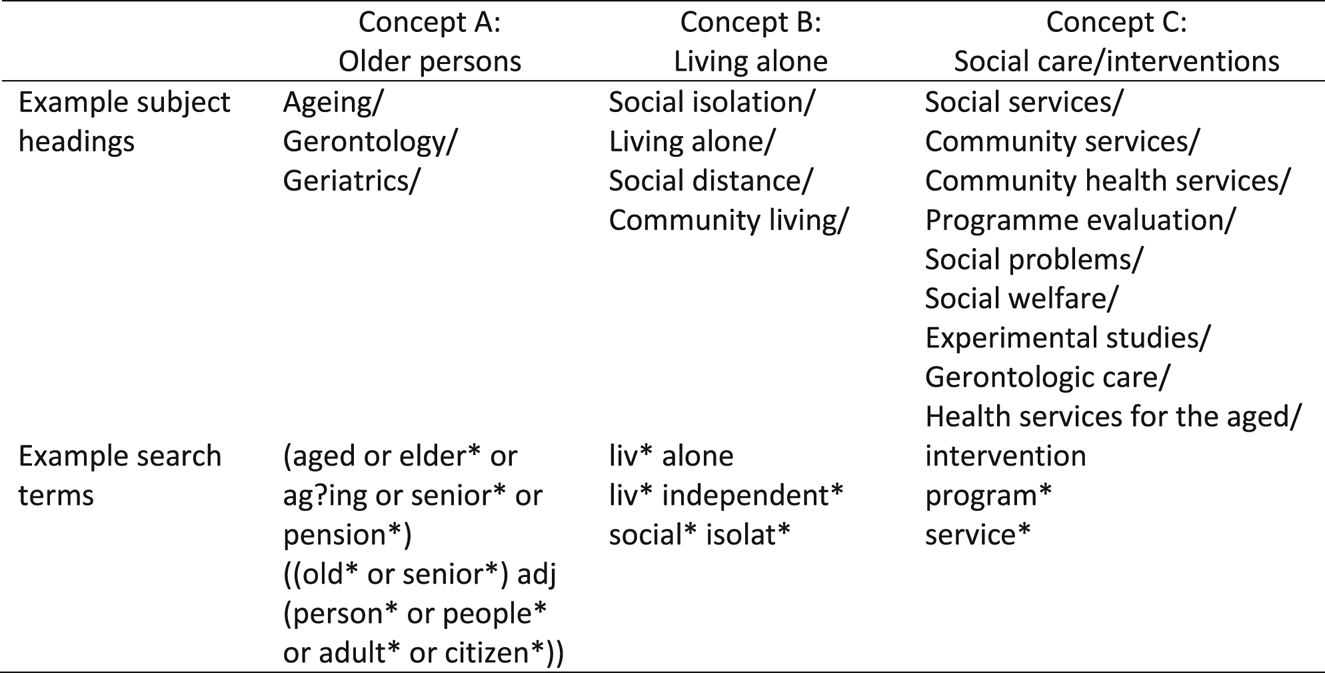

Data sources and search strategy

We conducted an electronic search of CINAHL (1937 to present), MEDLINE (1946 to present), PsycINFO (1806 to present) and Scopus (1823 to present) databases, in August 2018. A library scientist guided the development of the search strategy, which used a combination of keywords, wildcards and appropriate truncations tailored for each database. No limits on publication date were applied (for the search strategies, see Figure 1). We manually searched the reference lists of included studies to identify additional studies.

Figure 1. Example search strategy.

Study selection

Two of three authors (ER, MD, GJ) independently screened titles and abstracts of studies retrieved using the search strategy and those from included reference lists to identify studies that potentially met the inclusion criteria. We retrieved full texts of potentially eligible studies which were independently assessed for inclusion; with any discrepancies resolved by consensus.

Inclusion criteria

As our preliminary scan of the literature revealed little research in this area, we used a broad approach to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. We included studies if they reported outcomes for an intervention intended to increase the health and wellbeing of individuals who were: aged 55 years or older, and living alone in the community (i.e. not living in a residential care facility), or reported results for an intervention for those living alone separately to those who lived with others. The age restriction was set at 55 years to capture issues surrounding the tension between biological and functional age (Levine and Crimmins, Reference Levine and Crimmins2018) and the associated services (e.g. aged care) and entitlements (e.g. withdrawing superannuation, pension) that individuals are eligible to access. Although two studies (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Scharlach and Price Wolf2014, Reference Graham, Scharlach and Kurtovich2018) may have involved a small number of individuals aged under 55 (see Table 2), as the focus of the intervention was older adults, we included them in this review. We included interventions if they reported (a) health and wellbeing outcomes; (b) information relating to the duration, content and context of the intervention; and (c) information relating to the evaluation method of the provided intervention. All study types were included. We excluded articles that did not report primary studies (e.g. editorials, commentaries, opinion pieces), or were in a language other than English.

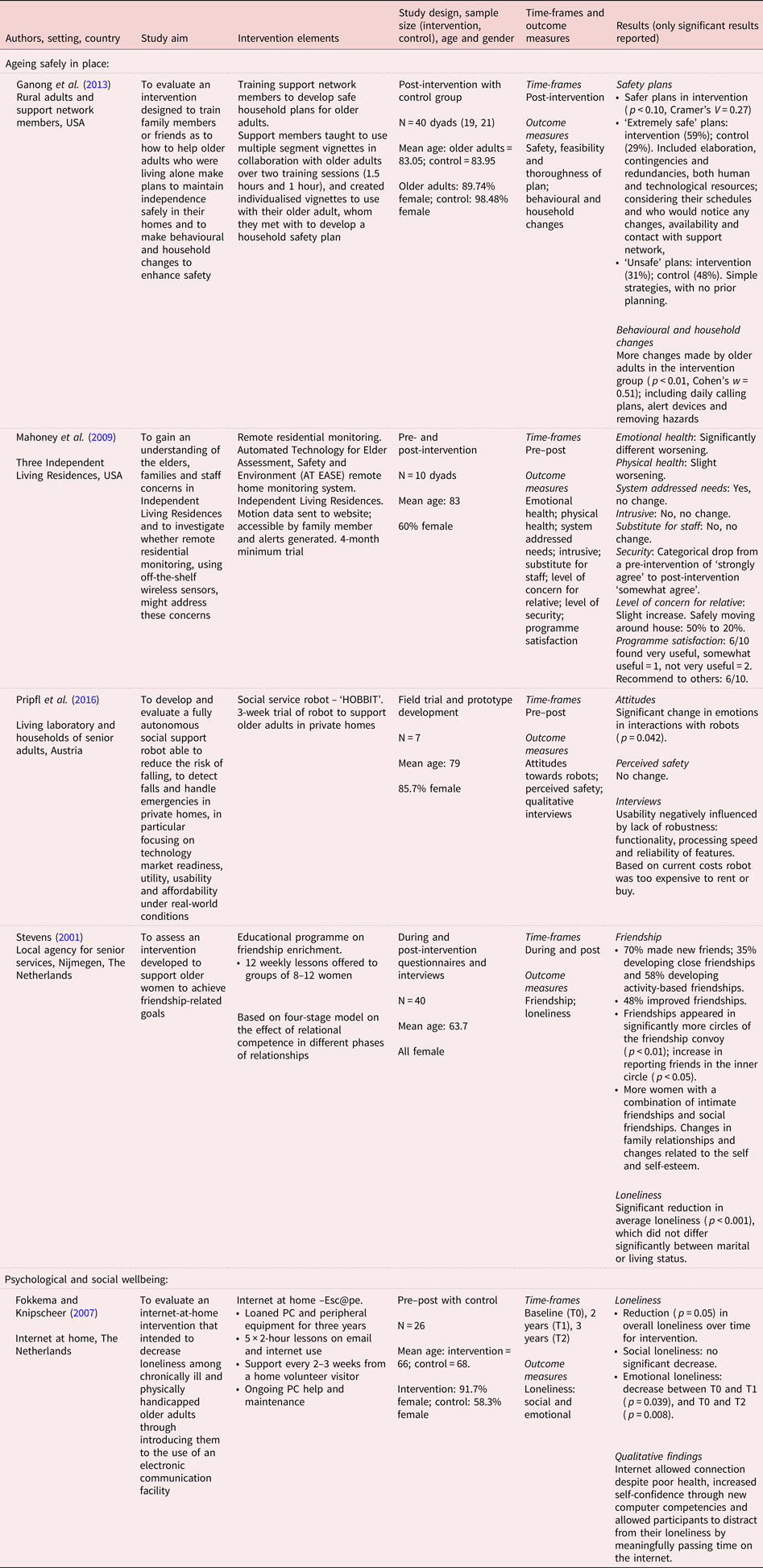

Table 2. Characteristics of quantitative studies

Notes: ADL: activities of daily living. AOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio. CI: confidence interval. DG: discussion group. IADL: instrumental activities of daily living. MSE: mean squared error. OR: odds ratio. PHV: preventive health visit. RCT: randomised controlled trials. SD: standard deviation. SE: standard error. SMD: standardised mean difference. USA: United States of America.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two of three authors (GJ, GM, MD) independently extracted data from the included studies, using forms developed prior to the review. Information on study aims, methodology, population, context, intervention and outcomes were collected. We used two checklists developed by Kmet et al. (Reference Kmet, Lee and Cook2004) for quantitative and qualitative studies as a framework to assess the risk of bias of the included studies. We extracted data including study design, context, sampling, intervention, outcome measures, analysis and results, with different criteria outlined for qualitative and quantitative studies. For mixed-methods studies, we used both qualitative and quantitative checklists. The checklists were completed independently, and consensus was reached through discussion with a third author.

We used the Theory of Access (Penchansky and Thomas, Reference Penchansky and Thomas1981; Saurman, Reference Saurman2015) to evaluate each intervention against the six dimensions of access outlined in the Introduction. Each intervention was reviewed on two considerations, whether (a) any of the dimensions of access were explicitly addressed in the design of the intervention, and (b) whether any of the dimensions of access were explicitly evaluated in the results. Two authors (GJ, MD) completed this independently, with consensus reached through discussion.

Data synthesis

Due to heterogeneity, we used the narrative synthesis method. Narrative synthesis collates the collective findings into a coherent, textual narrative, and is highly appropriate when examining the needs and/or preferences of a specific population group (i.e. older people living alone) (Popay et al., Reference Popay, Roberts, Sowden, Petticrew, Arai, Rodgers, Britten, Roen and Duffy2006).

We grouped included studies together based on their focus on improving or maintaining aspects of life for older people living alone. Four authors (GJ, MD, JL, RO) developed these overarching themes through discussion, with studies included in the most relevant categories as designated through consensus.

Results

Search results are summarised in Figure 2. Twenty-eight articles met the inclusion criteria for the narrative synthesis. Studies were published between 1984 and 2018, and comprised quantitative (N = 19), qualitative (N = 4) and mixed-methods (N = 5) approaches. Quantitative studies included six randomised controlled trials (RCTs), four quasi-experimental studies, two uncontrolled pre-post studies, five cross-sectional studies, one control post-test and one case control. Mixed-methods studies included one each of: pre-post with control, post-intervention with control, during and post-intervention without control, one pre-post without control and one pre-post trial without control. Qualitative studies involved two phenomenological case studies, and one each of semi-structured interviews and qualitative survey data. Over half of the studies (N = 17, 61%) were undertaken in English-speaking countries (United States of America (USA) N = 13; United Kingdom (UK) N = 2; Canada N = 1; Ireland N = 1). The remaining studies originated from Europe (N = 6; The Netherlands N = 2; Sweden N = 2; Austria N = 1, Norway N = 1) and Asia (N = 5; China N = 1; Taiwan N = 2; Korea N = 2).

Figure 2. Search results.

Overall, the mean age of participants was 77.1 years. For those that reported gender, the majority of studies (N = 20) included more females than males, with four studies including only women. Sample sizes ranged from N = 7 participants (Rose, Reference Rose2006; Pripfl et al., Reference Pripfl, Kortner, Batko-Klein, Hebesberger, Weninger and Gisinger2016) to N = 1,753 participants (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Scharlach and Stark2017), and the majority of studies (N = 15) had samples of 100 participants or fewer. Tables 2–4 outline the key characteristics and summary outcome results of included studies.

Table 3. Characteristics of qualitative studies

Notes: ADL: activities of daily living. IADL: instrumental activities of daily living. USA: United States of America.

Table 4. Characteristics of mixed-methods studies

Notes: PC: personal computer. USA: United States of America.

Overall, the studies performed poorly on addressing the dimensions of access in both design and evaluation of interventions. Accessibility was the most considered dimension in the design of interventions, included in 75 per cent of studies. The most popular way in which accessibility was addressed was through the provision of services in the home, particularly in the ageing safely in place category. Acceptability (25% of studies) (e.g. consideration of user needs), affordability (21%) (provision of a free service), availability (18%) (frequency of service provision) and adequacy (14%) (staffing and access hours) were the next most addressed dimensions, with awareness only being considered by two of the 28 studies.

Acceptability was the most evaluated dimension of access, with 57 per cent of studies examining the perception of the user of the service. Availability (39%; could the user access services when they needed), adequacy (32%; functionality), accessibility (25%) and affordability (21%) were the next most evaluated dimensions. Again, awareness was evaluated least frequently, by just five of the 28 (18%) studies. The performance of each study on the dimensions of access is outlined in Table 5.

Table 5. Performance of studies on the dimensions of access

Notes: ✓: addressed in study. X: not addressed in study.

We categorised the interventions into two overarching themes: those that were assessed to promote (a) ageing safely in place (N = 17) and (b) psychological and social wellbeing (N = 11).

Ageing safely in place

Studies in this category involved interventions aiming to keep participants living safely in the community setting, falling under two sub-groups: service provision and assistive technology. Studies in this category were predominately delivered in the home to increase accessibility for users.

Service provision

Seventeen studies addressed ageing in place by providing services to individuals who live alone.

Hospice care

Bly and Kissick (Reference Bly and Kissick1994) evaluated a demonstration programme that provided home hospice care to individuals living alone in Philadelphia, USA. The service was designed considering all but one of the dimensions of access: with accessibility (provided in home), availability (staffing and service adequacy); affordability (payment sources) and adequacy (admission requirements, functions and continuity of care) addressed. Whilst the acceptability to users was not considered, staff's initial concerns about the service were taken into account. Although the home hospice allowed individuals to receive care and die at home, without compromised safety, evaluation of availability and affordability showed that providing hospice care at home was more costly than regular hospice care, and required greater service intensity, particularly on the part of case managers.

Home-care services

Rose (Reference Rose2006) explored the impact of case-managed home-care services such as domestic assistance and meal delivery to housebound older individuals living alone. Six themes emerged from interviews with seven individuals, including discussions of acceptability and adequacy, with themes such as: needing reassurance, a connection to others and a sense of control over circumstances; confidence that someone cared for their welfare; and that they could live alone relatively independently, while receiving help from their case manager if necessary.

Home nursing

Three studies were designed to be accessible to older individuals living alone by utilising home-visiting nurses. Ahn et al. (Reference Ahn, Park and Kim2018) explored the impact of an eight-week nutritional education and support programme for older adults living alone in Korea. Implemented by home-visiting nurses and dieticians, the intervention was designed to be accessible and acceptable, as an individualised programme delivered in the home and via phone calls. Compared to the control group, significant increases in dietary habits and nutritional knowledge were observed in the intervention group, in conjunction with significant increases in blood levels of protein, iron, and vitamins A and C.

Huang et al. (Reference Huang, Wu, Jeng and Lin2004) evaluated the efficacy of a home-based nursing programme in the diabetes management of older people living alone in Taipei. Availability was assessed by comparing two different intensities of home-based nursing care visitations (daily and weekly) with a control group. Both the daily and weekly visits showed significant reductions in fasting blood sugar, post-meal blood sugar, haemoglobin A1c, total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein compared to the control. Although those having daily visits had a significantly greater weight reduction than those with weekly visits, there was no significant difference in diabetes knowledge, depression level or quality of life. Given the results, the authors recommended that although the implementation of daily visits is optimal, given the weekly visits still performed better than the control group, this may be an initial step in improving health and wellbeing in this group where staffing may be limited.

Toien et al. (Reference Toien, Bjork and Fagerstrom2018) assessed the perceived benefits and opinions of preventive health visits (PHVs) to older people in Norway. These annual visits were designed to address multiple dimensions of access; as they were delivered free of charge (affordability) and involved assessing older people's health status and life situation, then providing personalised support (acceptability) including information and referrals to services (awareness). PHVs added to individual's feelings of safety; supported them to live at home and have a good life; and had high ratings of satisfaction and were perceived to be important. Interestingly, those who lived alone felt less supported to stay at home, and felt the service was less important than those living with others, with the authors identifying supporting this group as an area of improvement for the service.

Home-delivered meals

Through investigation of how home-delivered meals are perceived in older adults living alone compared to those living with others, Lee and Raiz (Reference Lee and Raiz2015) evaluated the accessibility, acceptability and affordability dimensions of access. Both groups identified that benefits of the service included food security, better nutrition and the convenience of home delivery. Accessibility (driven by transportation problems), financial benefits (cost covered by the programme) and support provided by the programme were more important to those living alone than to those living with others. Those living alone provided more varied recommendations to improve the service, including greater variety in meals and meals appropriate for specialised diets.

Adult Day Health Centres

Schmitt et al. (Reference Schmitt, Sands, Weiss, Dowling and Covinsky2010) investigated the impact of Adult Day Health Centre participation on health-related quality of life. Overall, physical and emotional role scores as measured by the SF-36 (Ware, Reference Ware1997) improved significantly. Living alone status contributed to physical functioning and mental health at six months, although adjusting for living alone as a factor in predicting quality of life may not completely capture the influence of living alone on this domain. No dimensions of access were addressed in the design or evaluation of the intervention.

At-risk populations

Two studies evaluated the Independent Living Program for Older Individuals Who Are Blind (Moore et al., Reference Moore, Giesen, Weber and Crews2001, Reference Moore, Steinman, Giesen and Frank2006), addressing the acceptability and availability dimension of access by examining programme satisfaction and functional outcomes for those living alone or with others.

Moore et al. (Reference Moore, Steinman, Giesen and Frank2006) found that regardless of living situation, participants were similarly satisfied with the quality, timeliness (getting services when needed) and goal achievement resulting from the services. Additionally, differences in living situation had minimal impact on functional outcomes, with those living alone having greater perceived ability to prepare meals and manage housekeeping tasks, while those living with others could access reading materials better.

Examining a different cohort with the same questions, Moore et al. (Reference Moore, Giesen, Weber and Crews2001) found that those living alone rated the services higher than those living with others, including feeling better able to move confidently around their house, apartment or yard, better able to prepare meals for themselves, better able to manage housekeeping tasks and more in control of making decisions important in their life.

Safe plans

Ganong et al. (Reference Ganong, Coleman, Benson, Snyder-Rivas, Stowe and Porter2013) evaluated an intervention to help older adults remain and enhance their ability to live safely in their home, through training their family or friends. Having these support network members use vignettes to help older people develop safe plans led to plans that were safer than the control group. Participants in the intervention group created more ‘extremely safe’ plans, which included considering their schedules and who would notice any changes, availability and contact with support network, and utilisation of both personal and technological resources. Additionally, significantly more behavioural changes were made by older adults in the intervention group. No dimensions of access were addressed in the design or evaluation of the intervention.

Village membership

Three studies examined the Village model (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Scharlach and Price Wolf2014, Reference Graham, Scharlach and Stark2017, Reference Graham, Scharlach and Kurtovich2018), a consumer-directed, social support, membership organisation that promotes ageing in place and independence. The Village model is designed to be accessible (highly community based), and promote awareness of services through information, advice and referrals.

A retrospective cross-sectional survey of five Californian Villages (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Scharlach and Price Wolf2014) aimed to assess the perceived impact of Village membership on factors associated with the likelihood of ageing in place. The greatest impact was on encouraging social engagement and facilitating access to services. Living status did not affect the impact of the Village on members’ social engagement, perceived service and health-care access, perceived health and wellbeing, or self-efficacy and independence.

A 12-month longitudinal analysis of data from seven Californian Villages (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Scharlach and Kurtovich2018) supported these findings, with members reporting significantly greater confidence ageing in place, perceived social support and less intention to relocate after one year in the Village. This was amplified for those living alone, with those living alone significantly more likely to feel they could get the help they needed to stay in their current residence.

Results from a larger cross-sectional survey (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Scharlach and Stark2017) of active Village members from 28 Villages across the USA also identified the greatest impact of membership being social connection and support. Those who lived alone were also significantly more likely to perceive an increase in access to medical care, improved quality of life and improved ability to get to places they need or want to go.

Combined, the accessibility of Villages was seen to be particularly impactful for those living alone.

Assistive technology

Four of the 17 studies addressing ageing safely in place utilised assistive technology and included service robots (N = 1), medical alert devices (N = 1), home monitoring (N = 1) and eHealth monitoring (N = 1). All studies were pilots or trials to establish feasibility, usability, acceptability and functionality of these technology-based interventions with older people.

Service robots

One small study examined the usability and feasibility of developing and implementing a domestic help robot. Pripfl et al. (Reference Pripfl, Kortner, Batko-Klein, Hebesberger, Weninger and Gisinger2016) addressed the accessibility, acceptability and affordability dimensions of access by running a three-week trial with their ‘HOBBIT’ robot. Although the potential functions of the robot were positively received by the seven older participants, the reliability and speed of functions resulted in negative views of the usability of the robot. This included lack of complexity of tasks performed, errors, lack of adaptability and responsiveness. Additionally, in part due to these limitations, the robot was seen as a novel toy by many participants. At the current pricing, users in the trial reported a preference for the more affordable option of human home care.

Medical alert devices

Morgenstern et al. (Reference Morgenstern, Adelman, Hughes, Wing and Lisabeth2015) investigated the feasibility, acceptability and potential benefits of using medical alert devices on health-related quality of life in older women living alone. The trial could not establish feasibility, due to the inability to recruit sufficient numbers. This was attributed to a lack of adequacy, with participants not having a land-line telephone (a necessity for system installation), or already having a medical alert device. Acceptability was limited. Of the 133 women using the medical alert device, only one intentionally used the device, with nine utilising emergency services without the device. Half wore the device almost all of the time, with 12 per cent never wearing the device. Additionally, the cost of the device was prohibitive for many of the participants, with only 17 per cent planning to keep the device if they had to pay for it. There was no significant improvement in health-related quality of life, anxiety, depression or perceived isolation in the intervention group compared to control.

Home monitoring systems

Mahoney et al. (Reference Mahoney, Mahoney and Liss2009) addressed several dimensions of access in a mixed-methods examination of the implementation of remote residential monitoring in Independent Living Residences. The system was designed based on feedback from older residents, relatives, building managers and nurses, taking into account considerations relating to accessibility, availability, acceptability and adequacy. After the four-month trial period, the participants expressed that the system addressed their needs, was not intrusive, but could not be a substitute for care staff. However, compared to pre-intervention, they reported that the system made them feel less secure (strongly agree to somewhat agree). The authors attributed this to the initial positive expectations of participants, coupled with the lack of visual component in the monitoring system. Although the health and wellbeing of the resident participants did not improve and they felt less secure with the system, the family member participants reported being less concerned about the resident's safety around the house after the intervention. Potential price points and associated features were also explored. Overall, the system was positively viewed, however, some felt the system would be more useful for those with poorer health or concerning behaviours.

eHealth monitoring

Jung and Lee (Reference Jung and Lee2017) conducted a pilot examining the impact of eHealth self-management for older Koreans living alone. As participants did not have computers or internet at home and spent most of the day at the community centre, the pilot was designed to address accessibility and availability through use of a community-based computer to collect eHealth information, in conjunction with four weeks of in-class education and monthly telephone counselling for 24 weeks. The age and level of adoption of technology were also considered in the design of the intervention, drawing on concerns around acceptability and awareness. The eHealth participants showed significant improvement in systolic blood pressure, self-efficacy, self-care behaviours and social support when compared to the control participants.

Psychological and social wellbeing

This category includes interventions designed to address psychological and social wellbeing, including depression, social isolation loneliness and life satisfaction. Interventions included visitor and befriending services (N = 4), group activities (N = 4), online technology (N = 1), case management (N = 1) and reminiscence therapy (N = 1).

Visiting and befriending interventions

Four studies evaluated the impact of visitor and befriending services on older people living alone, with varied findings. Like the services designed to assist individuals to age safely in place, these interventions all were designed to address accessibility by being provided in the homes of participants.

Calsyn et al. (Reference Calsyn, Munson, Peaco, Kupferberg and Jackson1984) compared various modes of weekly friendly visitor programmes on life satisfaction, in a two-part study. Firstly, in comparing face-to-face visiting, phone visiting and no treatment, no differences were found in life satisfaction, with participants’ living situation (alone or with others) also having no impact. Although included as a more cost-effective alternative, the phone visiting intervention was found to lack adequacy, with four participants dropping out. The second part of the study looked at two styles of face-to-face visiting, one focusing on engaging with the participant's past personal history and the other being a present-oriented, companionship style. Again, no significant difference was found between these two styles, although a significant effect of living condition was observed, with individuals living with someone increasing their life satisfaction more than those living alone.

In contrast, Cheung and Ngan (Reference Cheung and Ngan2000) found that a six-month volunteer visiting and networking intervention did have a positive impact on older isolated and frail seniors in Hong Kong. Participation in the intervention resulted in a significant decrease in anxiety and significant increase in community knowledge. Additionally, regression analysis identified that having more contact with a volunteer (availability) significantly reduced anxiety, and increased social integration and knowledge about community services; with the perceived helpfulness of the volunteer (acceptability) also increasing social integration and knowledge. However, the intervention did not achieve its aim of improving participant's physical health, which was attributed to volunteers not being trained or skilled in offering medical advice or assistance.

McHugh Power et al. (Reference McHugh Power, Lee, Aspell, McCormack, Loftus, Connolly, Lawlor and Brennan2016) addressed the accessibility and affordability dimensions of access by investigating a novel application of the friendly visitor concept. Peers visited older people who were living alone and socially isolated, to prepare and share a low-cost weekly meal in their home. This parallel RCT assessed self-efficacy, food enjoyment and energy intake, finding that only the improvement in food enjoyment across all four time-points (baseline, 8-, 12- and 26-week follow-up) was significant between groups.

The remaining study examined befriending services using qualitative methods. Andrews et al. (Reference Andrews, Gavin, Begley and Brodie2003) explored the views of older people living alone who used a local home-visiting befriending service. This study addressed the most dimensions of access of all studies included in this review, addressing accessibility, acceptability, adequacy and awareness. Older people primarily became aware of the service and were referred through female relatives, neighbours or health professionals. Although the befriending service was often only one of many received by the older people, it was seen as more acceptable and having the greatest social impact due to the voluntary nature and focus on building relationships. Adequacy and availability of the service were raised as being important to participants, with the reliability of the befrienders, compatibility and reciprocity in the relationship key. Duration and frequency of visits was an important issue. Overall, users felt that the befriending service did ameliorate the effects of social isolation.

Group activities

Interventions utilising group activities were another means of improving social isolation and engagement. Three out of the four interventions in this category targeted only female participants; these studies will be discussed first.

Andersson (Reference Andersson1985) investigated the impact of small, accessible, neighbourhood group meetings in older women living alone. Significant increases in social contacts and participation in leisure activities were found, as well as a significant decrease in systolic blood pressure in the intervention group when compared to the control group. However, the decrease in blood pressure was determined by the author to be related to trust developed in the intervention, not a reduction in loneliness.

Bidonde et al. (Reference Bidonde, Goodwin and Drinkwater2009) also focused on participation of nine older women through a group fitness programme. One particular theme arising from the qualitative data, ‘It's our programme’ addressed multiple dimensions of access, outlining how participants took pride, responsibility and ownership of the programme to meet their needs. This included the accessibility of the programme, in that their participation was tied to car access; affordability, with the need for the programme to be financially accessible to people on fixed incomes (annual membership of US $5 and nominal drop-in fee); acceptability in relation to ability- and age-appropriate activities; and adequacy, with the programme taken over by the participants part-way through.

The final female-focused intervention by Stevens (Reference Stevens2001) addressed the acceptability and awareness dimensions of access through an educational friendship enrichment programme. The programme was deemed successful by the author in its awareness dimension, managing to attract the intended cohort of lonely women. The majority of participants had made new friends, both close and activity-based friendships. Additionally, the women reported an increased variety of friendships as well as more intimate, trusted friendships. Overall, there was a significant reduction in average loneliness during the year after the intervention. This did not differ significantly based on marital or living status.

In the only group activity study to include both women and men, Zingmark et al. (Reference Zingmark, Fisher, Rocklov and Nilsson2014) examined three occupation-focused interventions designed to increase leisure engagement and ability in activities of daily living. The three interventions –individual, activity group and discussion group – were compared to a control group. Although participants in all groups experienced a decline in activities of daily living and leisure engagement, those involved in the individual intervention and discussion group experienced a decline to a lesser extent at both three and 12 months. However, all effect sizes were small. No dimensions of access were addressed in the design or evaluation of the intervention.

Online technology

Fokkema and Knipscheer (Reference Fokkema and Knipscheer2007) investigated the impact of a three-year, internet-at-home intervention in a population of housebound older adults living alone. A significantly greater reduction in loneliness over time was found for the intervention group compared to the control group. This reduction was particularly evident for emotional loneliness. The internet allowed social connection despite poor health, increased self-confidence through new computer competencies and allowed participants to distract from their loneliness by meaningfully passing time on the internet. Designed to be accessible and affordable through free internet and computer services being provided at home, the intervention was deemed successful at selecting very lonely seniors (awareness), and examining benefits for those with different education levels and consequently different digital sensitivities (adequacy).

Case management

Clarke et al. (Reference Clarke, Clarke and Jagger1992) delivered a case worker-driven intervention in the home to support accessibility, with social support packages tailored to the need of each individual to enhance acceptability. Self-perceived health status was the only outcome measure to show a significantly greater improvement in the intervention group. The authors did note that half the older people in the intervention group declined multiple offers of assistance. This group were more independent, having greater social contact and greater self-perceived health status.

Reminiscence therapy

The remaining study, by Liu et al. (Reference Liu, Lin, Chen and Huang2007), addressed the acceptability dimension of access by exploring the effects of reminiscence group therapy for older people living alone in Taiwan. Comparing this group who received ten sessions with a control group who participated in regular group activities for ten weeks, reminiscence group therapy participants had significantly raised self-esteem, lowered loneliness and improved life satisfaction.

Risk of bias

Quantitative studies

Four-fifths of categories for studies using a quantitative design were rated as adequate, with the remaining categories rated as partially adequate, inadequate or not applicable (see Table 6). Only two studies considered whether the sample size was adequately powered (Moore et al., Reference Moore, Steinman, Giesen and Frank2006; Morgenstern et al., Reference Morgenstern, Adelman, Hughes, Wing and Lisabeth2015). However, one such study was underpowered (Morgenstern et al., Reference Morgenstern, Adelman, Hughes, Wing and Lisabeth2015), failing to recruit sufficient participants. In addition, one further study calculated sample size based on feasibility (McHugh Power et al., Reference McHugh Power, Lee, Aspell, McCormack, Loftus, Connolly, Lawlor and Brennan2016). Over 90 per cent of the studies adequately described the research question, had appropriate and evident study design, and had conclusions adequately supported by the results. Approximately three-quarters had appropriate description and processes of subject selection and characteristics, with two-thirds adequately describing the intervention itself with sufficiently defined and robust measures. Only five studies adequately described random allocation (Calsyn et al., Reference Calsyn, Munson, Peaco, Kupferberg and Jackson1984; Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Clarke and Jagger1992; Zingmark et al., Reference Zingmark, Fisher, Rocklov and Nilsson2014; Morgenstern et al., Reference Morgenstern, Adelman, Hughes, Wing and Lisabeth2015; McHugh Power et al., Reference McHugh Power, Lee, Aspell, McCormack, Loftus, Connolly, Lawlor and Brennan2016), two had blinding of investigators (Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Clarke and Jagger1992; McHugh Power et al., Reference McHugh Power, Lee, Aspell, McCormack, Loftus, Connolly, Lawlor and Brennan2016) and none had adequate blinding of subjects; which is to be expected given the breath of study designs included, the preliminary scope of many studies and the difficulty of blinding to non-pharmacological interventions.

Table 6. Assessment of risk of bias: quantitative

Notes: 1. (a) Question/objective sufficiently described? (b) Study design evident and appropriate? (c) Method of subject/comparison group selection or source of information/input variables described and appropriate? (d) Subject and comparison group characteristics sufficiently described. (e) Intervention (description, duration) adequately described. (f) If interventional and random allocation was possible, was it described? (g) If interventional and blinding of investigators was possible, was it reported? (h) If interventional and blinding of subjects was possible, was it reported? (i) Outcome and exposure measured well defined and robust to measurement/misclassification bias? Means of assessment reported? (j) Sample size appropriate? (k) Analytic methods described/justified and appropriate? (l) Estimate of variance. (m) Controlled for confounding? (n) Results reported in sufficient detail. (o) Conclusions supported by the results. 2. Indicates mixed methods. 3. Sample size based on feasibility. ++: yes. +: partial. −: no. NA: not applicable. NS: not stated.

Source: Criteria adapted from Kmet et al. (Reference Kmet, Lee and Cook2004).

Qualitative studies

Almost two-thirds of the risk of bias categories for qualitative studies were rated as adequate (Table 7). All qualitative studies provided a clear definition of the question and context, which was appropriate for the nominated qualitative study design. All but one connected the study to a theoretical framework or wider body of knowledge (Lee and Raiz, Reference Lee and Raiz2015). Nine had an adequate sampling strategy; seven had systematic data collection. All except one study (Ganong et al., Reference Ganong, Coleman, Benson, Snyder-Rivas, Stowe and Porter2013) that was mixed-methods particularly lacked rigour in their qualitative components, evident in the systematic data collection and analysis components. All presented conclusions supported by results. Four adequately used verification procedures including multiple data sources (Bidonde et al., Reference Bidonde, Goodwin and Drinkwater2009), discussion, peer review or multiple coding within the research team (Andrews et al., Reference Andrews, Gavin, Begley and Brodie2003; Bidonde et al., Reference Bidonde, Goodwin and Drinkwater2009; Cattan et al., Reference Cattan, Kime and Bagnall2011; Ganong et al., Reference Ganong, Coleman, Benson, Snyder-Rivas, Stowe and Porter2013) and triangulation of findings (Rose, Reference Rose2006; Bidonde et al., Reference Bidonde, Goodwin and Drinkwater2009). Overall, the majority of studies lacked reflexivity, with only one adequately addressing (Rose, Reference Rose2006) and one partially addressing (Bidonde et al., Reference Bidonde, Goodwin and Drinkwater2009) this category.

Table 7. Assessment of risk of bias: qualitative

Notes: 1. (a) Question/objective clearly described? (b) Design evident and appropriate to answer study question? (c) Context for the study is clear? (d) Connection to a theoretical framework/wider body of knowledge? (e) Sampling strategy described, relevant and justified? (f) Data collection methods clearly described and systematic? (g) Interview schedule described? (h) Data analysis clearly described, complete and systematic? (i) Use of verification procedure(s) to establish credibility of the study? (j) Conclusions supported by the results? (k) Reflexivity of the account? ++: yes. +: partial. −: no. 2. Indicates mixed methods.

Source: Criteria adapted from Kmet et al. (Reference Kmet, Lee and Cook2004).

Discussion

Numerous interventions have been developed to optimise health, wellbeing, quality of life and independence for older people living alone in the community; with two key foci, to age safely in place and to enhance psychological and social wellbeing. However, few interventions addressed dimensions of accessibility. This is the first study, to our knowledge, to synthesise the evidence for effectiveness and accessibility of such interventions. To date, research has focused on ageing in place, and psychological and social wellbeing, without explicitly addressing all dimensions of accessibility to services as described by the Theory of Access (Penchansky and Thomas, Reference Penchansky and Thomas1981; Saurman, Reference Saurman2015). These dimensions must be considered alongside the needs and preferences of this population during design, implementation and evaluation of interventions to assist individuals to age in place. Of particular note was the observation that studies of higher quality tended to perform poorly on dimensions of access. This is likely a result of high-quality studies such as RCTs, by their very nature, being restrictive in both their sampling and outcomes examined. The most common types of study included were pilot and feasibility trials, resulting in the low sample sizes and overall poor study quality.

Two overarching themes emerged from the studies: ageing safely in place, and psychological and social wellbeing. Studies falling under ageing safely in place focused primarily on providing services to individuals living in their homes, and technology aimed at monitoring and assisting individuals who live by themselves. The second theme, psychological and social wellbeing, included a range of interventions involving visiting or befriending, group activities, case management and reminiscence therapies. This theme also included an emphasis on technology through online communication. Although the concepts of living alone, social isolation and loneliness are often used interchangeably throughout the literature (Yeh and Lo, Reference Yeh and Lo2004), they are not synonymous, and experiencing one does not necessarily mean the others will occur (Klinenberg, Reference Klinenberg2016). Evidently, many factors may impact the health, wellbeing and quality of life of those living alone, and consequently their ability to remain living independently in the community.

Despite being a population for which service access is a particular issue, the included studies performed poorly in both design and evaluation of the dimensions of access. The majority of studies addressed only one or two dimensions of access, and focused on the ‘user’ or ‘person’ characteristics such as accessibility, acceptability and affordability; almost no studies addressed the ‘organisation’ characteristics such as adequacy, availability and awareness. This emphasis seemingly suggests an attitude which places the lack of access to services on the individual rather than organisational level, which may exacerbate poor access for vulnerable populations, including older individuals who live alone. This also hampers sustainability of these programmes beyond the research project, as no consideration is given to how the successful interventions and knowledge can be successfully translated into practice within organisations. Of particular concern to successful implementation or rollout is the lack of focus on awareness of services. If the end-users do not know a service exists, despite being a successful evidence-based programme, it is unlikely to make a difference to the target group (Strain and Blandford, Reference Strain and Blandford2002; Tang and Pickard, Reference Tang and Pickard2008).

Accessibility, in the form of transport, is a significant issue for individuals as they age (Goins et al., Reference Goins, Williams, Carter, Spencer and Solovieva2005; Greaves and Rogers-Clark, Reference Greaves and Rogers-Clark2009; Andonian and MacRae, Reference Andonian and MacRae2011; Bacsu et al., Reference Bacsu, Jeffery, Novik, Abonyi, Oosman, Johnson and Martz2014; Orellano-Colón et al., Reference Orellano-Colón, Mountain, Rosario, Colón, Acevedo and Tirado2015), however, the only way in which transport was addressed by the included studies was to remove it entirely from the equation by bringing the services or interventions into the home. While this is an admirable way to ensure housebound individuals receive the services they require, some of these individuals would be able to leave the house with assistance. It also raises the question of service providers prioritising accessibility (i.e. delivering programmes in the home) over acceptability (i.e. is it what the older individuals would prefer?). Further interventions which facilitate appropriate individuals to leave the house should be considered, in line with a wellness and reablement (Department of Social Services, 2015) or intrinsic capacity (World Health Organization, 2017) approach. In addition, assisting individuals to maintain function before becoming housebound is also worth pursuing.

There was a significant emphasis on technology in the included studies. However, there are many barriers to access that were not addressed, such as technical skill, physical limitations, privacy concerns and cost (Coelho and Duarte, Reference Coelho, Duarte, Abascal, Barbosa, Fetter, Gross, Palanque and Winckler2015; Ofei-Dodoo et al., Reference Ofei-Dodoo, Medvene, Nilsen, Smith and DiLollo2015). This lack of emphasis may be due to the early nature of the research that was particularly characteristic of the technological studies, and may improve as the field matures. However, participants in these studies did identify these barriers as reasons why the interventions, such as service robots or home monitoring, were not feasible, usable or accessible in their current state. In addition, while technology provides exciting new opportunities to assist individuals to age in place, we must be mindful of the group for which these interventions are intended, and ensure that they meet the needs, wishes and skills of this group, whilst remaining affordable.

While one-third of the studies used either a qualitative or mixed-methods approach which allowed for the perceptions and experiences of individuals to be explored, and dimensions of access to be more easily evaluated, there was limited evidence of similar participant-focused principles used in the design of interventions. Involving end-users in the design of new services and interventions is vital to ensure that the intervention meets the access needs of users and service providers (Greenhalgh et al., Reference Greenhalgh, Jackson, Shaw and Janamian2016), with one such approach being co-design. Studies which did not consider dimensions of access in the design stage often identified access problems in the evaluation stage, which could have been addressed and prevented before roll-out. The insights about accessibility (or lack thereof) provided by the included qualitative approaches is evidence of the importance of conducting qualitative, observation and multi-level evaluations alongside high-quality quantitative trials, to ensure that there is a meaningful translation of research evidence into practice (Rychetnik et al., Reference Rychetnik, Frommer, Hawe and Shiell2002). Further, while intervention outcome measures important to service providers are necessary, those receiving the intervention also need to be involved in deciding the measures of success that are important to them. In this way, providers can be sure that they are measuring whether the intervention is actually meeting the needs of the target group. Therefore, further high-quality studies using co-design processes are recommended in this area.

The average age of participants was in the mid-seventies; given increasing life expectancies individuals are living at home for longer (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2017), necessitating further studies to be conducted in older cohorts, particularly the ‘oldest-old’ to ascertain if their needs and preferences differ from the younger individuals. In addition, the studies tended to include more women than men – indeed some studies focused only on women – this may be due to higher proportions of women living alone in older age due to factors such as higher life expectancy, alongside social factors such as widowhood and divorce (de Vaus and Qu, Reference de Vaus and Qu2015a). However, the majority of these studies were not designed specifically with or for women despite the overwhelming population.

Conclusion

Older people comprise an increasing proportion of the global population, and generally wish to age in place in the community. This trend will contribute to increasing numbers of older people living alone in the community, for which appropriate services and supports must be available and accessible to maintain independence and optimise wellbeing. Access to services is a considerable issue in this age group, hence the dimensions of access should be used to guide service development. Likewise, end-users should be engaged in service development and evaluation. Recommendations for future studies include considering the dimensions of access and incorporating co-creation principles into the service design process for each service to ensure that it is meeting the needs not only of older people living alone, but also the service providers. Finally, robust evaluations built in to such service developments are also strongly recommended.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Georgia Major for assisting with data extraction and Lorenna Romero for informing and guiding the search strategy.

Author contributions

MD, JL, ER, JE, DM and RO conceived and designed the study. GJ, MD and ER conducted the search, and extracted and assessed data. GJ and MD wrote the article, with all authors providing critical feedback.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Lord Mayor's Charitable Foundation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.