Introduction

Autism is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterised by social interaction and communication problems, difficulty relating to people, things and events, and repetitive and restrictive behaviours (APA, 2019). Despite these difficulties, individuals with high-functioning autism spectrum condition (ASC) demonstrate positive attributes, such as analytic thinking, research skills, understanding complex ideas, and intense focus on subjects of interest (Lei et al., Reference Lei, Calley, Brosnan, Ashwin and Russell2018), which fit well with the academic skills required in higher education (HE). However, estimates of HE students with ASC are low, at approximately 2% (MacLeod and Green, Reference MacLeod and Green2009). Initiatives to improve opportunities and access to HE, e.g. the University of Bath’s Autism Summer School (Lei, Reference Lei2019), are resulting in increasing numbers of students identifying as being on the autistic spectrum (Sims, Reference Sims2016). There is, however, an imbalance in HE between knowledge of autism and delivery of services (Durkin et al., Reference Durkin, Elsabbagh, Barbaro, Gladstone, Happé, Hoekstra, Lee, Ratazzi, Stapel-Wax, Stone, Tager-Flusberg, Thurm, Tomlinson and Shih2015), perhaps hindered by limited research examining the needs of students with ASC (Cai and Richdale, Reference Cai and Richdale2016), especially those with mental health needs, which is prevalent in this population.

University is a time of great anxiety for many students, who strive to achieve high grades required for employment in a competitive market. However, individuals with ASC face significantly greater challenges and mental health difficulties than their non-autistic peers (Gurbuz et al., Reference Gurbuz, Hanley and Riby2019). Such challenges can affect their ability to succeed at university (Hotez et al., Reference Hotez, Shane-Simpson, Obeid, DeNigris, Siller, Costikas, Pickens, Massa, Giannola, D’Onofrio and Gillespie-Lynch2018) including: high anxiety and poor stress management (White et al., Reference White, Oswold, Ollendick and Scahill2010); sensory overload (Sims, Reference Sims2016), including sensitivity to light and sound (Martin, Reference Martin2018; Sarrett, Reference Sarrett2018); social isolation (Lei et al., Reference Lei, Calley, Brosnan, Ashwin and Russell2018; Madriaga, Reference Madriaga2010); executive dysfunction (Hill, Reference Hill2006); high stress (Jackson et al., Reference Jackson, Hart, Brown and Volkmar2018); weak central coherence (Booth and Happé, Reference Booth and Happé2010; Happé, Reference Happé2011); social anxiety in group work (Madriaga and Goodley, Reference Madriaga and Goodley2010); and anxiety with reduced academic performance (Owens et al., Reference Owens, Stevenson, Hadwin and Norgate2012). There is emerging evidence that university students with ASC can benefit from psychological interventions such as the Programme for the Education and Enrichment of Relational Skills (PEERS®; Laugeson and Frankel, Reference Laugeson and Frankel2010), which has been effective in improving students’ social skills and friendship closeness (Garbarino et al., Reference Garbarino, Dow-Burger and Ratner2020).

Individuals with ASC exhibit anxiety levels significantly higher than the general population (Bellini, Reference Bellini2004), with prevalence rates between 42 and 79% (Kent and Simonoff, Reference Kent, Simonoff, Kerns, Renno, Storch, Kendall and Wood2017). Social anxiety disorder (SAD) is amongst the most common disorder (Spain et al., Reference Spain, Sin, Linder, McMahon and Happé2018); it is disabling and impacts on social and educational functioning (Wells and Papageorgiou, Reference Wells and Papageorgiou2001). Psychotherapy is gaining support as a viable treatment modality for individuals with ASC (Gaus, Reference Gaus2019) with cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) as the recommended treatment (Weston et al., Reference Weston, Hodgekins and Langdon2016). NICE (2013) recommend Clark and Wells’ (Reference Clark, Wells, Heimberg, Liebowitz, Hope and Schneider1995) cognitive model, which involves idiosyncratic conceptualisation, socialisation and manipulation of safety behaviours (Wells and Papageorgiou, Reference Wells and Papageorgiou2001). CBT for SAD is considered to be efficacious for clients with ASC (Turner and Hammond, Reference Turner and Hammond2016; Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Wilansky-Traynor and Rector2012; Wright, Reference Wright2013) but effects may be inflated and over-estimated (Spain et al., Reference Spain, Sin, Harwood, Mendez and Happé2017). CBT outcomes are, however, reduced in co-morbid conditions (Noyes, 2011), which are common in ASC populations (van Steensel et al., Reference van Steensel, Bögels and Perrin2011) and co-morbidity is associated with increased symptom severity and impairment (Norton et al., Reference Norton, Barrera, Mathew, Chamberlain, Szafranski, Reddy and Smith2013).

Generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) is one of the most common co-morbid anxiety disorders (up to 90%) (Noyes, 2011; Simon, Reference Simon2009), with co-existing conditions responding less well to psychological treatment. CBT is the gold standard treatment for GAD, and NICE (2013) recommends Wells’ (Reference Wells1997) cognitive model of GAD, which is considered suitable for clients with ASC if clinicians adjust the method of delivery or duration of intervention according to the individual’s need. Sze and Wood (Reference Sze and Wood2008) endorse CBT as a viable treatment modality if it is carefully adapted to meet the unique needs of clients with ASC. NICE (2012) recommends treatment for both core ASC symptoms and co-morbid conditions but there is scant research examining the effects of CBT in adult populations, with most studies focusing on children (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Wilansky-Traynor and Rector2012).

NICE (2012) highlight the importance of clinicians having a good understanding of the core symptoms of ASC, and their possible impact on the intervention. The evidence base indicates that psychosocial interventions for adults with anxiety should be informed by NICE guidance for specific disorders (e.g. SAD or GAD); however, a range of adaptations should be made to the delivery of cognitive and behavioural interventions. These include: (i) a more structured and concrete approach, using visual and written information (e.g. mapping out anxiety cycles), (ii) emphasis on changing behaviour rather than cognitions, especially at the start of therapy, (iii) using clear and unambiguous language, (iv) making rules explicit, and explaining the context, (v) involving a family member, carer or professional to provide support during the intervention (if consent is given by the individual), and (vi) offering regular breaks and incorporating specialist interests to aid the individual’s attention. While there is agreement that adaptations are required in order to accommodate neuropsychological and socio-communication difficulties, Spain and Happé (Reference Spain and Happé2020) draw attention to the absence of empirically derived guidance about how best to adapt CBT for individuals with ASC, and argue that more research is needed to clarify the efficacy and acceptability of adapted CBT.

To date, there is a dearth of research identifying the specific support needed for university students with ASC (Barnhill, Reference Barnhill2016), although recent interventions have attempted to meet this gap (e.g. Hillier et al., Reference Hillier, Goldstein, Murphy, Treitsch, Keeves, Mendes and Queenan2018). Only 12% of students with ASC report contact with mental health professionals as a positive experience (Beardon and Edmonds, Reference Beardon and Edmonds2007) as therapists often need more support (Shankland and Dagnan, Reference Shankland and Dagnan2015) and further training in adapting evidence-based interventions to ensure that individuals with ASC receive treatment that meets their needs (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Loades and Russell2018). In the context of limited research in this field, this paper aims to explore the utility of CBT for co-morbid social and generalised anxiety in an individual with ASC.

Method

Design

A single-case (n=1) A-B design (Barlow and Hersen, Reference Barlow and Hersen1984) was employed in this study. An assessment of the client’s difficulties was established during a 3-session baseline (A), followed by 13 weeks of CBT for anxiety intervention (B).

Participant

This case study reports the case of ‘Mark’, a White British male, aged 19 years, with high-functioning ASC, developmental coordination disorder, sensitivity to light and sensitivity to sound. Mark was referred for an autism assessment during childhood, and subsequently received a diagnosis of ASC and was considered to be at the high-functioning end of the spectrum. Mark was referred for therapy to help manage severe social and generalised anxiety that was impacting on his ability to attend and engage in university studies. Mark lived with his parents, who provided significant practical support. Mark met weekly with a trainee clinical psychologist on a doctoral (DClin.) course over a 5-month period (with breaks for university holidays and the university exam period). Mark had no prior experience of CBT and provided consent for the write-up and dissemination of this case study.

Therapist

The trainee therapist received weekly supervision from an experienced clinical psychologist with specialist knowledge of working with people with ASC, and also received monthly supervision from an experienced CBT therapist accredited by the British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies (BABCP). The trainee therapist had pre-doctoral experience of working with university students with ASC and delivering 1:1 therapy with young people with a range of needs. The therapist was on a DClin. course that was BABCP Level 2 accredited, which required assessment of CBT adherence and fidelity on each clinical placement using the Cognitive Therapy Scale-Revised (CTS-R). The therapist received an overall score within the proficient range.

Assessment

A structured CBT assessment took place over three sessions, to identify Mark’s presenting problems, history, goals for therapy, protective factors, and risk. In accordance with Sze and Wood’s (Reference Sze and Wood2008) recommendation that CBT is adapted to meet the needs of clients with ASC, there was no specified time scale for the assessment period, as these sessions went at Mark’s pace, with breaks offered during sessions. The therapist was mindful that concrete examples may be needed, and tried to ensure that language used was clear and accessible.

Presenting problems

Mark presented with severe social and generalised anxiety. He found all social situations daunting; he attributed all difficulties to having autism and a heightened sensitivity to light and sound. Mark was particularly struggling with group-based academic assessments, which were a regular component of his degree. Mark’s generalised anxiety was significantly impacting on all aspects of his life; Mark struggled with specific anxiety about his mother’s physical health and the impact this had on his studies. Mark described having very high expectations of himself, which had been helpful in the past and resulted in previous academic success. This was very important to his family, who had been told by various professionals that Mark should not expect to achieve any academic success. Mark felt proud that he had proved professionals wrong and wanted to continue doing so. Mark did not have any peer support as he had not made friends at university. Mark struggled with sleep and described needing to spend time gaming on his computer to wind down after intense periods of academic study. Mark experienced gastrointestinal problems, which were exacerbated by extended periods of intense study as Mark frequently forgot to drink unless prompted, which contributed to issues with constipation. Mark was prescribed medication for this.

The assessment identified the following features of social anxiety and general anxiety, with specific anxiety about academic work and anxiety about his mother’s physical health:

Social anxiety

Mark said that this included underlying worries about what people thought about him, and difficulties in managing the uncertainty in not knowing how people will respond in different situations. Mark also identified worry about saying something wrong when communicating with others, and worry about being misunderstood in social situations. He also worried about not understanding the intentions of others, and worried that all social interactions would result in disastrous consequences.

General anxiety

General anxiety was described by Mark as ‘anxiety about nothing’, i.e. it was impossible not to feel generally anxious, it ‘feels as though there is no reason for this anxiety, this feels like anxiety for anxiety’s sake’ and ‘this anxiety is not grounded in anything, it is just there’. Mark said general anxiety ‘makes you feel on edge and restless and it makes you feel irritated’. It was hard for Mark to understand general anxiety and he believed ‘I shouldn’t feel anxious’ and questioned ‘why am I feeling like this? I hate this!’.

Anxiety about his Mum

This included worry that ‘everything is in chaos because Mum is in hospital’, worry that ‘I shouldn’t be worrying as Mum wouldn’t want me worrying about her’, worry about needing to spend time visiting his mother in hospital while managing strong feelings of ‘I should be working’, and worry about not having his mother present to help with practical tasks like organising files and assisting with planning the weekly academic work schedule.

Specific work anxiety

This included worry about not being able to get academic work done fast enough or well enough; worry about the intensive approach that is always needed to complete work by set deadlines; and worry about feeling guilty about not working better/faster/to a better standard.

Case history

Mark experienced on-going bullying at school. He described himself as being ‘different from the other children’, as he often engaged in solitary imaginative play and had difficulties with writing, as a result of a developmental coordination disorder and associated fatigue. Mark’s sensitivity to light, sound and crowds caused him to avoid being around groups of pupils and he described himself as being naturally introspective, which he believed contributed to him over-thinking and over-analysing everything. Mark demonstrated awareness that others had different beliefs to his own (i.e. theory of mind) but sometimes relied on his mother to offer alternative perspectives when problem-solving difficulties. Mark did well, academically, with the support of a 1:1 teaching assistant and note-taker, but this support was withdrawn prior to Mark’s GCSEs (as a result of him doing well in academic assignments). Consequently, Mark struggled to cope with the academic demands and was home-schooled for the remainder of school.

Goals

Mark wanted psychology support for severe social and generalised anxiety that were negatively impacting on his ability to engage in his university studies. Specifically, Mark wanted to: (i) make sense of the anxiety that ‘keeps my head feeling very full’ and (ii) find ways to manage social and general anxiety in order to manage better at university.

Protective factors

Mark had very supportive parents, who assisted with a broad range of practical support, including providing transport to university, helping with study techniques and offering emotional support when required. Mark benefited from spending time with the family pet, which he found calming, in addition to playing computer games, which he found relaxing. Mark had developed helpful coping strategies, such as arriving early and sitting at the front of lectures to avoid feeling overwhelmed by crowds of people.

Risk

Risk to self and others was assessed as low during the initial assessment and remained low throughout the therapy process. Although there were no risk concerns, mood was assessed each week during the general check-in part of the session.

Measures

In accordance with NICE (2013), routine sessional outcome measures were employed to assess the impact of the therapeutic intervention on Mark’s anxiety, including:

Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN)

The Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN) scale was administered weekly to assess symptoms of social anxiety. It is a 17-item self-report measure with responses ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely) and is used to screen for and assess the severity of social anxiety disorder. Items include ‘I avoid talking to people I don’t know’ and ‘I am afraid of doing things when people might be watching’. The SPIN has ‘good test-retest reliability, internal consistency, convergent and divergent validity’ (Connor et al., Reference Connor, Davidson, Churchill, Sherwood, Foa and Weisler2000; p. 379). Scores range from 0 to 68, with a clinical cut-off of 19 distinguishing between social phobia and controls (Letamendi et al., Reference Letamendi, Chavira and Stein2009). Scores are categorised as mild (21–30), moderate (31–40), severe (41–50) and very severe (above 50) (Chukwujekwu and Olose, Reference Chukwujekwu and Olose2018).

Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) scale

The Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) scale was administered weekly and is considered a reliable and valid measure of anxiety in the general population (Lowe et al., Reference Lowe, Decker, Muller, Brahler, Schellberg, Herzog and Herzberg2008; Mills et al., Reference Mills, Fox, Malcarne, Roesch, Champagne and Sadler2014; Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Lowe2006). The GAD-7 has cut-off scores of 5 (mild anxiety), 10 (moderate anxiety) and 15 (severe anxiety), with a clinical cut-off score of 10 when screening for anxiety disorders (Williams, 2014), although NHS (2018) advocate a clinical cut-off of 8. GAD-7 has been employed in ASC populations, although the psychometric properties have not been fully assessed (Russell et al., Reference Russell, Cooper, Barton, Ensum, Gaunt, Horwood, Ingham, Kessler, Metcalfe, Parr, Rai and Wiles2017).

Idiographic measures

In the absence of standardised measures to assess anxiety about his mother’s health and work-related anxiety, idiographic ratings of anxiety were recorded every session, on a scale of 0–10, where 0 represents an absence of any anxiety and 10 represents extreme anxiety. These were completed for: (i) social anxiety, (ii) general anxiety, (iii) anxiety about his mother and (iv) anxiety about academic work.

Formulation

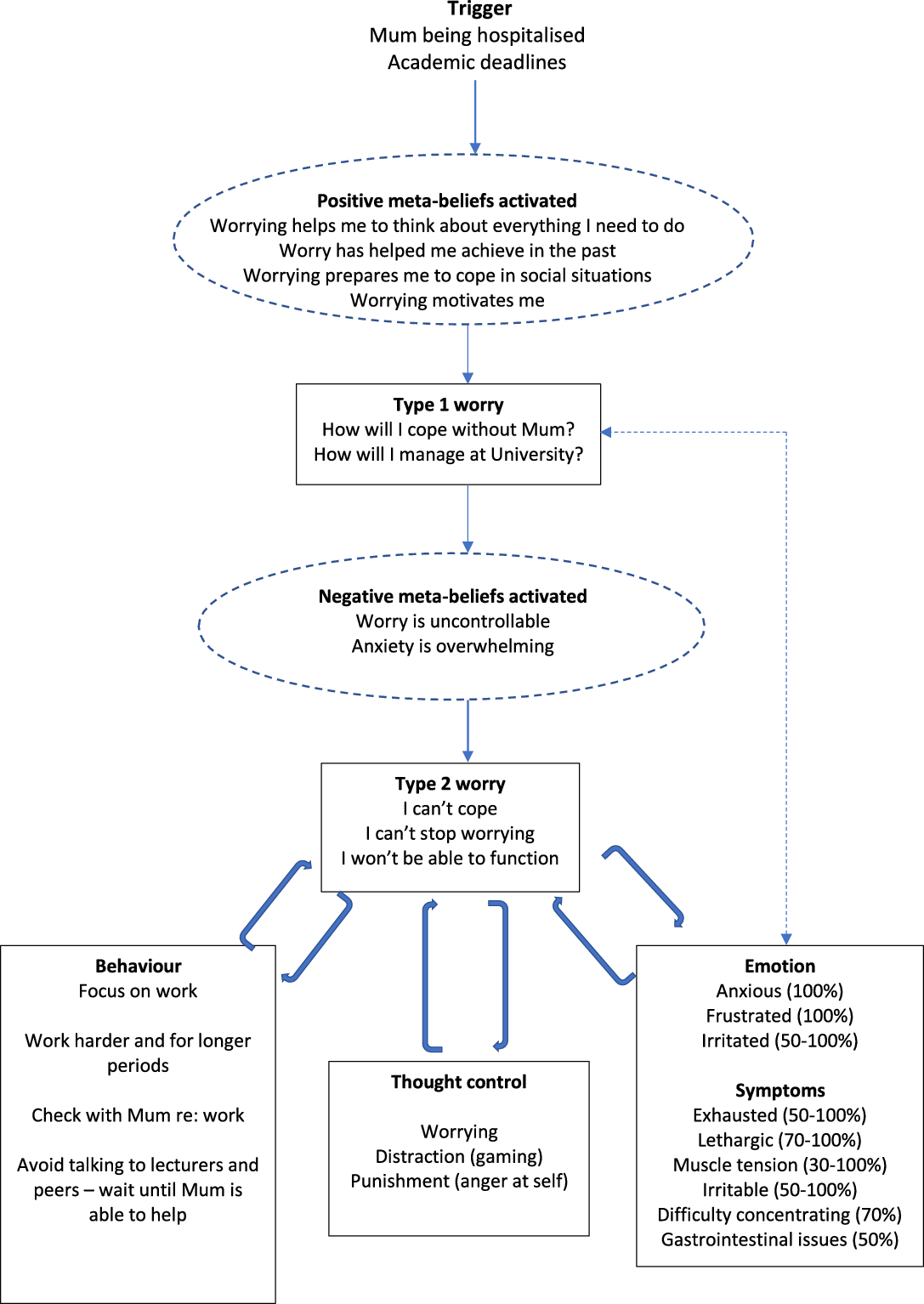

In the absence of a holistic CBT model that accurately captured the nuances of Mark’s co-morbid social and generalised anxiety, separate models were employed to formulate Mark’s difficulties. First, Clark’s (Reference Clark, Crozier and Alden2001) cognitive model of social anxiety was used (as shown in Fig. 1) as it is an updated version of the Clark and Wells’ (Reference Clark, Wells, Heimberg, Liebowitz, Hope and Schneider1995) cognitive model recommended by NICE (2013). Second, Well’s (Reference Wells1997) cognitive model of generalised anxiety was employed (illustrated in Fig. 2) to make sense of the positive and negative meta-beliefs and worries that were triggered by Mark’s mother’s admission to hospital.

Fig. 1. Diagram of cognitive model of Mark's social anxiety.

Fig. 2. Diagram of Mark's GAD formulation.

Mark’s social anxiety formulation was developed through collaborative discussion, which revealed that Mark had developed assumptions about himself and his social world based on negative early experiences (Clark, Reference Clark, Crozier and Alden2001). Mark’s social anxiety was maintained by very high standards of his own performance (Clark and Wells, Reference Clark, Wells, Heimberg, Liebowitz, Hope and Schneider1995), e.g. ‘I must have something novel and valuable to contribute’. Mark had been vocally reticent in school but had received praise from teachers when offering novel perspectives. Mark had also developed conditional beliefs that ‘saying or doing the wrong thing’ would result in disastrous consequences. For example, he believed that saying the wrong thing at university would result in others misunderstanding him and then spreading rumours about him, which he had experienced at school. Mark had developed unconditional negative beliefs about self, including being ‘different’; he believed others saw him as ‘weird’ because of his experiences of early social communication difficulties at a time when he did not engage in peer-play, and instead spent time by himself. He also did not socialise with others because the sensory over-stimulation made it difficult for him to process information. The bullying Mark experienced throughout school informed his beliefs as an adult that others are not to be trusted, and Mark’s school experiences taught him that he felt safest when alone and away from others. Mark’s attempts to avoid negative evaluation by others involved closely monitoring how he behaved and watching every word spoken. However, this resulted in a negative impact of social avoidance (Lambe et al., Reference Lambe, Russell, Butler, Fletcher, Ashwin and Brosnan2019), which resulted in Mark being pre-occupied, unable to keep up with conversations around him and this left him feeling exhausted and wary of engaging with others. A diagrammatic representation of Mark’s social anxiety formulation is presented in Fig. 1. As advocated by Kuyken et al. (Reference Kuyken, Padesky and Dudley2011), the social anxiety formulation was collaboratively modified as Mark shared new information in subsequent sessions.

When collaboratively making sense of Mark’s generalised anxiety (as illustrated in Fig. 2), Mark recognised that he has ‘always been a worrier’ and believed this was part of his personality but noticed that excessive worry had heightened considerably since his mother was admitted to hospital, which coincided with important academic deadlines. At a time of great uncertainty about his mother’s prognosis, positive meta-beliefs were activated, i.e. that worry might actually help Mark to get motivated to tackle his assignments without the support he had always had from his mother. Nonetheless, Mark worried about how he would cope without his Mum and worried about how he would manage his academic studies (Type 1 worry), which kept him awake at night and interfered significantly with his ability to concentrate and attend to academic tasks. Worries about not being able to cope, not being able to stop worrying and not being able to function (Type 2 worries) resulted in Mark feeling anxious, frustrated, irritated and overwhelmed. When this occurred, he tried distracting himself with computer games, but this resulted in feeling guilty for not working and, subsequently, directing anger towards himself for failing to meet work targets. In order to understand the processes involved with trying to complete academic work that caused Mark to feel overwhelmed, a vicious cycle was mapped out, as shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Diagram of vicious work cycle.

Hypotheses

It was hypothesised that tailored CBT would be an acceptable and helpful intervention in reducing Mark’s social and general anxiety, which would have a positive impact on Mark’s academic study.

Course of therapy

Following three assessment sessions, Mark engaged in 13 CBT for anxiety sessions, each lasting approximately 1¼ hours. It was agreed that longer sessions would be offered to accommodate Mark’s request for more time to process information and think about his answers to questions in sessions (NICE, 2013). As recommended by NICE (2017), in the presence of co-morbid anxieties, the most severe anxiety was treated first. Collaborative assessment and formulation revealed that Mark would benefit from focusing on generalised anxiety first, including understanding the dominant themes of worry about his Mum and academic work before moving on to social anxiety (as illustrated in Table 1). Each session consisted of a check-in, review of homework, agenda setting, session content, summary, and setting homework. Although perspective-taking is considered to be challenging for some individuals with autism (Baron-Cohen, Reference Baron-Cohen1989), Mark responded well to Socratic and guided discovery questions. Mark did not require significant adaptations in terms of communication methods; he was cognitively able and articulate. Mark was insightful and adept at communicating his emotional difficulties. Effort was made to adhere to a set time for therapy to help provide structure and routine, which is considered important for people with ASC (Cai and Richdale, Reference Cai and Richdale2016). Although Mark struggled to concentrate on academic tasks, he did not present with attentional difficulties during the course of therapy, but took breaks when required to manage fatigue.

Table 1. Overview of CBT for generalised and social anxiety intervention

The first stage of the intervention (session 1) involved socialisation to the CBT model in a client-centred way to help develop the therapeutic alliance (Daniels and Weardon, Reference Daniels and Weardon2011). It included psychoeducation regarding stress responses, sleep hygiene, and grounding activities (including the five senses exercise, whereby Mark was asked to identify five things he could see, four things he could touch, three things he could hear, two things he could smell and one thing he could taste). Mark found this useful as it focused his mind on one sense at a time. The next phase focused on generalised anxiety (sessions 2–4) and included conceptualising worry; exploring dominant themes of worry about his mother and work; mapping out anxiety maintenance cycles; problem-solving difficulties in being more independent at university; restructuring cognitions; and behavioural experiments, which are considered to be effective strategies in reducing dysfunctional beliefs (Warmerdam et al., Reference Warmerdam, van Straten, Jongsma, Twisk and Cuijpers2010). An adapted (i.e. more literal) safe place exercise was also included in this phase; this included identifying an actual place that has felt safe for Mark, rather than an imaginary location, for example, a tropical island that has not ever been visited. Mark did not require further adaptations, that other individuals with autism might require. The next phase of the intervention (sessions 5–10) focused on social anxiety, including collaborative downward arrow work, exploring safety behaviours, cognitive restructuring and further behavioural experiments, which are evidence-based interventions for anxiety (NICE, 2009; Wilding and Milne, Reference Wilding and Milne2008). Behavioural experiments included testing out what would happen if Mark dropped safety behaviours (e.g. avoiding social interactions) and spoke to his peers during a university class. This provided an opportunity to test whether or not his worst fear of peers laughing at him would happen. Favourable responses from peers enabled Mark to build evidence that his worst fears would not happen when engaging in conversations with unfamiliar people. In order to remain client-centred, the final phase of the intervention (sessions 11–13) returned its focus to generalised anxiety. These sessions included work on unhelpful thinking habits, finding alternative thoughts, managing overwhelm, reviewing work and relapse prevention.

Homework was an essential part of the intervention (Beck, Reference Beck1979; Kazantzis et al., Reference Kazantzis, Brownfield, Usatoff and Flighty2017). It enabled Mark to practise and consolidate new skills (Freeman, Reference Freeman2007), test out alternative coping strategies, implement behavioural experiments and reflect on his achievements during the therapy process. Mark was motivated to try additional behavioural experiments over the Christmas break and reported feeling proud of his accomplishments when reporting them in subsequent sessions.

Outcomes

Social anxiety, as measured by the SPIN, ranged from severe (44) during the assessment phase to moderate (36) in the final session (as illustrated in Fig. 4), with the lowest score (31) in session 9, when Mark had successfully dropped safety behaviours during group work at university as part of a behavioural experiment. Despite the reduction in scores from pre- to post-intervention, SPIN scores remained clinically significant (i.e. above the clinical cut-off score of 19), indicating that Mark’s social anxiety remained stable throughout the course of therapy. Notwithstanding, Mark’s idiographic measures of social anxiety ranged from 10 during assessment to 4 at the end of the intervention, with the lowest level (3) reported in weeks 9 and 10 (also shown in Fig. 4), following further success in dropping safety behaviours in social settings during behavioural experiments. Idiographic measures appear to yield a treatment response not witnessed with the standardised SPIN measure.

Fig. 4. Graph of Mark's SPIN and idiosyncratic ratings of social anxiety.

Mark’s general anxiety, as measured by the GAD-7 increased from 19 during the assessment to 21 at the end of the intervention, indicating severe anxiety from the start to the end of the intervention (refer to Fig. 5). However, improvements in Mark’s general anxiety were witnessed in session 8 (where a GAD-7 score of 12 indicated moderate anxiety) and in sessions 11 and 12 (with consecutive GAD-7 scores of 7, indicating mild anxiety), with the latter considered to be a sub-clinical level of anxiety (Williams, 2014; NHS, 2018). Mark’s idiographic ratings of general anxiety ranged from 6 to 8, with the lowest scores also seen during the middle phase of the social anxiety intervention (sessions 8 to 11). Measurement error and possible transitory effects (such as improved sleep, mood or increased confidence) may account for the mid-intervention dip in scores, which did not continue to the end of treatment. The limited range in Mark’s idiographic ratings of general anxiety (mean=7) suggests relatively stable moderate generalised anxiety that was not impacted by the course of therapy. Idiographic measures of anxiety related to his mother reduced from 10 in the first assessment session to 1 by the end of the intervention (as shown in Fig. 6). Idiographic measures of academic work-related anxiety ranged from extreme anxiety (10) to a self-reported absence of anxiety (0) (illustrated in Fig. 6).

Fig. 5. Graph of Mark's GAD-7 and idiosyncratic ratings of general anxiety.

Fig. 6. Graph of Mark's idiosyncratic ratings of work anxiety and anxiety about Mum.

In addition, Mark identified positive changes during the course of therapy that were not captured in the quantitative measures. For example, Mark employed strategies to successfully manage social phobia in order to travel in a taxi alone for the first time in his life, with initial support from the team’s occupational therapist. This was a great achievement for Mark, who felt proud that he had been able to travel without a parent being present. By the end of the intervention, Mark experienced success in making friends at university and, following successful behavioural experiments, Mark spontaneously instigated contact with peers and arranged gaming competitions with them during the university holidays. Mark delighted in telling the therapist about his achievements and increased confidence (asking his mother to send an email to the psychology service as he could not wait until the next session to share his exciting news). Mark also reported having much greater insight into his anxiety and felt more confident in managing anxiety in future.

Discussion

This case demonstrated the use of CBT for co-morbid social and generalised anxiety in a high-functioning individual with ASC. Standardised ratings, used alongside idiographic measures to assess the impact of therapy, revealed mixed findings. Social anxiety reduced during the intervention on both the SPIN and the idiographic ratings, although Mark’s SPIN scores did not reach sub-clinical levels, indicating that persistent social anxiety remained throughout the intervention. If assessing the efficacy of the intervention using SPIN scores alone, one might conclude that CBT had not been effective in reducing Mark’s social anxiety. However, Mark’s idiographic ratings of social anxiety reduced from 10 (extreme social anxiety) pre-intervention to 4 (moderately low social anxiety) at the end of the intervention, thus indicating a considerable reduction in self-reported social anxiety. It is possible that characteristics of ASC might interfere with the validity of using standardised measures with individuals with ASC. For example, mental inflexibility (Jackson et al., Reference Jackson, Hart, Brown and Volkmar2018) or weak central coherence (Booth and Happé, Reference Booth and Happé2010) may have impacted on the responses given. In Mark’s case, because he had a good memory, he remembered and replicated his answers from the previous week, stating that ‘things broadly feel similar’. Although the therapist encouraged Mark to think about each measure and answer accordingly, a pattern of replicating responses became established and was particularly notable in the final seven sessions where Mark’s SPIN responses and scores were identical. Mark’s idiographic ratings of social anxiety appeared to correspond better with therapy discussions about social anxiety and, from the clinician’s perspective, seemed to be a more accurate appraisal of his social anxiety. This is supported by Hartley and MacLean (Reference Hartley and MacLean2006) who argue that idiographic measures are more suitable for use with people with developmental disorders.

Less favourable results were found for Mark’s GAD-7 scores, which indicated severe anxiety from the start to the end of the intervention. If appraising the efficacy of the intervention on pre- and post-measures alone, it would be reasonable to conclude that the intervention was not successful in reducing Mark’s generalised anxiety. There was, however, a reduction in GAD-7 scores to a moderate level of anxiety mid-intervention and a further reduction to mild levels of anxiety during the social anxiety phase of the intervention, indicating positive but temporary clinical change. The mechanisms of change (Teachman et al., Reference Teachman, Beadel, Steinman, Emmelkamp and Ehlring2014) at these points appear to be behavioural experiments and challenging cognitive distortions, although idiosyncratic factors such as mood could also have impacted on Mark’s scores. It is interesting that the greatest reductions in generalised anxiety were witnessed during the social anxiety intervention.

Mark’s anxiety about his Mum significantly reduced from extreme anxiety at the start of the intervention to very low anxiety by the end of the intervention. The mechanism of change appeared to be having a parent present during sessions, who could hear Mark’s worries and respond in a practical way; for example, by offering help with study planning or organising module files. Anxiety may also have reduced as a result of Mark’s mother experiencing small improvements in her physical health. Although Mark’s work-related anxiety was rated as severe by the end of the intervention, the presence of no anxiety in the first week of the university holidays indicated that idiographic ratings corresponded to academic deadlines, where Mark worried about his academic performance (Owens et al., Reference Owens, Stevenson, Hadwin and Norgate2012). Scores were consistently high in the sessions immediately preceding deadlines, especially for group projects, which are known to increase anxiety (Madriaga and Goodley, Reference Madriaga and Goodley2010). In this case, it was important to attend to wider contextual factors that influenced scores.

It is worth noting that the treatment responses yielded by the idiographic measures may have resulted from changes made in response to managing specific worries about work, Mark’s mother, social anxiety and general anxiety, that would not necessarily have impacted on scores from standardised SPIN and GAD-7 measures. Despite the variation in scores between standardised and idiographic measures, these could be viewed as complimentary to one another in capturing relevant change for individuals (Edbrooke-Childs et al., Reference Edbrooke-Childs, Jacob, Law, Deighton and Wolpert2015). For example, specific symptoms may be captured on standardised measures that could be missed on general idiographic ratings, meanwhile idiographic measures may capture issues very specific and meaningful to clients that may not be captured on standardised measures. Although the measures used yielded differences in results, to Mark, CBT was an acceptable and helpful intervention in reducing anxiety that he described as unmanageable at the start of the intervention.

By the end of the intervention, Mark reported having greater insight into his anxiety and increased confidence in using strategies to manage anxiety. The expansion of his social life was an important and meaningful outcome of this intervention not captured in either of the quantitative measures, and highlights the value in client feedback to psychological interventions. Qualitatively, Mark’s goals had been accomplished. For example, he reported being able to make sense of his social anxiety, particularly with improved understanding that having autism as a child impacted on his opportunities to play and mix with peers. In addition, his proclivity to avoid social interactions was understandable given his sensitivity to light, sound and crowds. Mark understood for the first time that his early experiences had caused him to be mistrusting of others and feel safer alone, but the academic and social requirements at university did not allow him to continue avoiding others. As Sims (Reference Sims2016) reasons, challenges in higher education are posed by the social environment, not deficits in the individual. Furthermore, challenges can be experienced in therapy if adjustments are not considered.

When considering ways in which the therapy process may differ when working with individuals with ASC, a number of specific adaptations were required in this case. First, it was necessary to increase the duration of sessions to 75 minutes to allow additional time for processing information, which can be atypical in diverse areas of cognition (Skoyles, Reference Skoyles2011). Second, it was important to ensure that the room was as free from distraction as possible to minimise sensory overload (Sims, Reference Sims2016). Third, frequent breaks were offered, as attention difficulties are common in individuals with ASC, potentially as a result of difficulties in flexibly shifting attention from one subject to another (Andersen et al., Reference Andersen, Hovik, Skogli and Øie2017). However, for Mark, breaks were required to manage fatigue rather than attentional difficulties. Fourth, therapeutic techniques were adapted to minimise reliance on abstract concepts (e.g. identifying a more literal ‘safe place’). For this reason, the therapist initially avoided the use of metaphors, but Mark valued metaphors being used in sessions, thus reinforcing the value of checking in with clients to identify personal preferences. Fifth, as endorsed by NICE (2012), Mark’s parents attended sessions to offer support and introduce alternative perspectives, which Mark found helpful. Finally, the structured and detail-focused nature of CBT (Kennerley et al., Reference Kennerley, Kirk and Westbrook2016) was a good fit for Mark. However, therapists may need to be mindful that attending preferentially to details can indicate weak central coherence (Happé, Reference Happé2011), which may impact on the therapy process.

Limitations

Threats to validity inherent in this single-case A-B design must be acknowledged. A return to baseline with withdrawal designs (ABA and ABAB designs), or drawing on concurrent baselines with multiple participants would have permitted a more rigorous evaluation; however, it was not possible within the time constraints of this intervention. The lack of randomisation (not possible in this case) further weakens internal validity. Future case study research in this area would benefit from incorporating replication via multiple baseline design. Study validity would have been further improved with follow-up data, which may have indicated longer-term gains (von Allmen et al., Reference von Allmen, Weiss, Tevaearai, Kuemmerli, Tinner and Carrel2015), particularly if Mark was able to continue dropping safety behaviours in social settings. This was not possible as the trainee left the service shortly after completing work with Mark. There is also limited generalisability in this single case design. A further limitation includes the possibility of measurement error, e.g. social desirability, although there was no evidence of acquiescence from Mark. Similarly, weekly measures may have been impacted by idiosyncratic transient factors, including mood and sleep deprivation (Viswanathan, Reference Viswanathan2005) when Mark had been working long into the night to complete assignments. Although the measures employed in this study have previously been used in research with individuals with autism, the psychometric properties for use in this population remains unclear. A further limitation on objectivity is acknowledged as this paper is written by Mark’s therapist. Further research on CBT for co-morbid anxiety in ASC populations may benefit from addressing these limitations.

Conclusion

This case highlights how CBT can be useful for people with ASC; however, fluctuations and improvements may best be captured using standardised measures in conjunction with idiographic measures, with one measure complementing the other. There remains a need for more research in this area, which would benefit from the development of sensitive and specific outcome measures for social and generalised anxiety in individuals with ASC.

Key practice points

-

(1) This case highlights the value in using SAD and GAD models when clients present with co-morbid anxieties, which is common in ASC populations.

-

(2) Characteristics of ASC (such as mental flexibility and central coherence) might interfere with the validity of standardised outcome measures to assess therapeutic change in cognitive behavioural therapy; idiographic measures may offer complimentary data when assessing outcomes in individuals with ASC.

-

(3) Further research is needed to identify what adaptations, if any, or training is required for clinicians to best meet the psychological needs of individuals with ASC.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mark (pseudonym) for his consent to the publication of this case study. Names used in the report have been changed to maintain confidentiality.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest with respect to this publication.

Ethical statement

All procedures contributing to this work comply with the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical reasons.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.