Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a leading cause of death and disability in trauma patients. Reference Majdan, Plancikova and Maas1–Reference Pfeifer, Tarkin, Rocos and Pape3 In Mexico, it is the third leading cause of death in general, just after heart disease and cancer. Reference Mayén Casas, Guerrero Torres, Caro Lozano and Zúñiga Carrasco4 Adherence to international guidelines for the early management of TBI has been described to be low. Reference Franschman, Peerdeman and Greuters5–Reference Lee, Rittenhouse and Bupp8 Preventing secondary brain injury through appropriate airway management and ventilation to prevent hypoxia and maintain normocapnia has been related to improved outcomes. Reference Rosenfeld, Maas, Bragge, Morganti-Kossmann, Manley and Gruen9,Reference Dumont, Visioni, Rughani, Tranmer and Crookes10 Airway management has been determined as a leading topic for prehospital research, either in physician-based services or with other providers. Reference van de Glind, Berben and Zeegers11–Reference Fevang, Lockey, Thompson and Lossius15 Prehospital endotracheal intubation has been related with improved outcomes; Reference Bernard, Nguyen and Cameron16,Reference Denninghoff, Nuño and Pauls17 however, due to variability in the success rates and how failures in airway management can be deleterious, Reference Timmermann, Russo and Eich18–Reference Bossers, Schwarte, Loer, Twisk, Boer and Schober20 it remains controversial.

The primary goal of this research was to describe the population of severe TBI patients according to their Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) treated by a physician-lead Emergency Medical Service who were intubated. The secondary goals were: to report the anesthetic agents used to assist the procedure and to determine if there was a relevant difference among the patients that were intubated from those who were not.

Methods

This is a retrospective analysis of a database from the Medical Emergencies Regulation Center (CRUM; Mexico City, Mexico). Mexico City’s CRUM is the office of the Health Secretariat that coordinates care from prehospital to public hospitals in those individuals without or with unknown health coverage. Its main responsibility is to assign the most appropriate hospital for the patient’s medical needs. These decisions are based on the clinical information provided by ambulance crews and the information of human and material resources provided by public hospitals three times a day. Also managed by CRUM are intensive care interhospital transfers between the public hospital network.

Four-hundred and fifty different ambulance corporations provide prehospital care in Mexico City. Reference Fraga-sastrías, Asensio-lafuente, Román-morales, Pinet-peralta, Prieto-sagredo and Ochmann-räsch21,Reference Pinet22 Ambulance assignment is based on geography only. The closest ambulance to the incident is dispatched with no regard to its level of care or to the predicted severity of the patient based on the emergency call. Mexico City’s Service of Emergency Medical Care (SAMU) is the operative division of CRUM. The standard SAMU ambulance crew is formed by a physician (mostly general practitioners), an emergency medical technician of variable levels of training, and a driver emergency medical technician.

The CRUM database is filled by emergency medical technicians or physicians assigned to the Medical Regulation room. The data are entered into pre-filled cases in a computer software. This software also provides a space for free-text entering where details not included in pre-filled spaces might be included, but it is not required. No personal data from patients are included in the database. Data entered are based on information provided by the caring physician while he or she is treating the patient. These data are then used to assign the hospital for patient transport. This dynamic of data transfer makes the database a “still shot” of the complete prehospital caring encounter, as treatment provided to patients after the call was made to the CRUM will not be included.

Access to the database was granted through a request of access to public information of the Health Secretariat of Mexico City from the period of January 1, 2012 through December 31, 2016. The database was provided as an Excel file (Microsoft Corp.; Redmond, Washington USA) for each year analyzed.

All patients with a primary prehospital diagnosis of head injury according to International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) classifications S-00 to S-09 treated by a SAMU ambulance were selected to apply the inclusion criteria. Adult patients (15-100 years of age) with a GCS <nine were included. Patients with GCS ≥nine, those that were transported from one hospital to another, patients categorized as deceased, and those with missing data were excluded from the analysis.

After seeing the data, dichotomization of patients into two groups was performed, those with isolated head injury and those with polytrauma, to test the hypothesis of a different incidence in intubation. Polytrauma was defined as traumatic lesions of the neck, thorax, abdomen, pelvis or femur bones, other than “simple contusions.” Patients that could not be dichotomized due to insufficient data were excluded from secondary analysis.

JMP 9.0.1 software (SAS Institute Inc.; Cary, North Carolina USA) was used for statistical analysis. Cross tabulation for airway management (intubation versus no intubation) and the GCS was performed and Chi Square analysis identifying statistical significance at (alpha) 0.01. The same analysis was performed comparing airway management with associated injury pattern (polytrauma versus isolated TBI). Multiple correspondence analysis was used to validate the Chi Square results.

Results

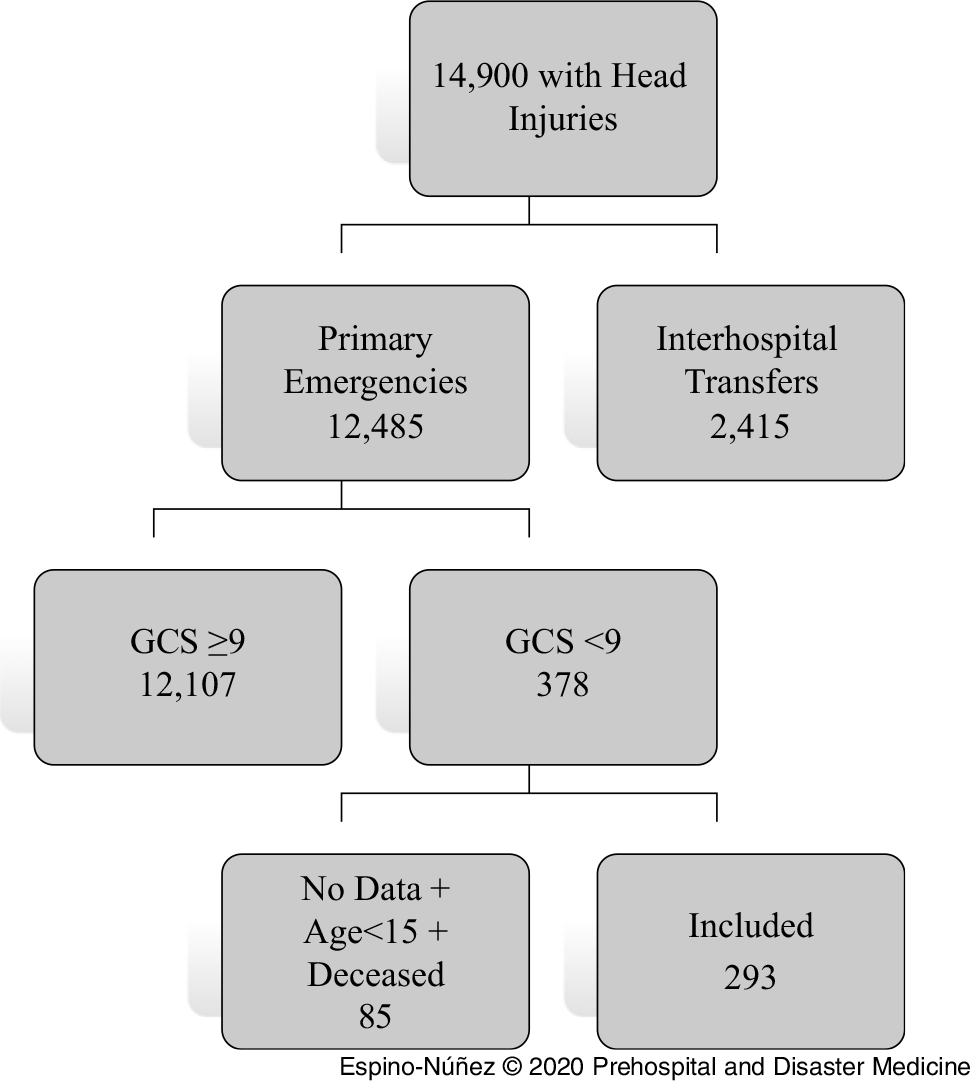

From January 1, 2012 through December 31, 2016, a total of 14,900 patients with an ICD-10 code of S-00 to S-099 were treated by SAMU ambulances in Mexico City. Of those, 2,415 were interhospital transports and were excluded from this analysis (Figure 1). From the 12,485 primary emergency transports, 378 cases had a GCS less than nine (3.0%). Eighty-five cases (22.5%) were excluded. Twelve had missing data, 14 were younger than 15 years old, and 59 were declared life extinct on scene. Of the 293 patients included, the mean age was 42 years old (16-96; SD = 18.83; median 37). Patients had a mean GCS of five (SD = 2).

Figure 1. Database Search Results.

One-hundred and fifty (51.1%) patients were intubated. Twenty-six patients had a reported pharmacologic assisted intubation. Of those, 15 patients received sedation and neuromuscular blockage, four patients were intubated with sedation alone, six patients with neuromuscular blockage alone, and one patient was intubated using opioid analgesia with sedation and neuromuscular blockage (Table 1).

Table 1. Patients Intubated with Medication Assistance

Abbreviations: GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; HR, heart rate; NMB, neuromuscular blockage; RR, respiratory rate.

There was no statistical difference between patients that were intubated depending on their GCS (χ2 = 12.687; CI, -0.388 to 0.028; P = .0265). There was not a statistical difference when comparing the outcome of prehospital intubation between patients with isolated head injury versus patients with polytrauma (χ2 = 0.566; CI, -0.248 to 0.455; P = .452).

Discussion

Patients with severe head injuries have been proven to have higher odds of dying in low- and middle-income countries. Reference de Silva, Roberts and Perel23 Unconscious patients defined by GCS <nine can have a mortality rate up to 40.0%. Reference Grote, Böcker, Mutschler, Bouillon and Lefering24

Only GCS was used to identify head injured patients. Grote, et al described that the correlation of GSC <nine and severe TBI (AIShead > 2) is moderate and the specificity is 82.2%. Reference Grote, Böcker, Mutschler, Bouillon and Lefering24 In the same study of a large trauma database, only 56.1% of patients with severe TBI had a GCS <nine, and almost 20.0% of patients with a GCS 15 had a severe TBI in neuroimaging. Reference Grote, Böcker, Mutschler, Bouillon and Lefering24

Previously was described that five percent of patients with a systolic blood pressure under 80 mmHg were intubated by prehospital providers in another Mexican city, Reference Arreola-Risa, Mock and Lojero-Wheatly25 but there was not a sub-group analysis of TBI patients and it was not a physician-based service. Also, Roudsari, et al reported the capabilities of prehospital care in developing countries, and endotracheal intubation was performed in two percent of trauma patients in the same Mexican city of the previously cited paper. Reference Roudsari, Nathens and Arreola-Risa26

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis by Bossers, et al has made an important distinction between the provider’s experience and the outcomes in patients with severe head trauma and prehospital intubation. Their results demonstrate a correlation between more experienced providers and better outcomes. Reference Bossers, Schwarte, Loer, Twisk, Boer and Schober27 Also, the lack of usage of anesthetics to assist the intubation has been associated with worse outcomes. Reference Evans, Brison, Howes, Stiell and Pickett28

Limitations

This study presents several limitations. It has a retrospective design that is based on a registry that relies on auto-report from the prehospital physicians. The database that was analyzed doesn’t represent the epidemiology of prehospital head trauma in Mexico City; it only represents the patients that were treated by SAMU ambulance crews.

The CRUM database had a significant amount of missing data, especially in the treatment section where 87 out of 293 patients with a GCS below nine (29.7%) had no airway or breathing treatment stated, not even supplementary oxygen. Also, there was a great amount of under-reported blood pressure and pulse oximetry in an issue that is thought to be related to the database and not to the recording habits of crews.

The performance evaluation of the procedure and the prehospital time couldn’t be assessed with the database. First pass success rate, number of attempts, and esophageal intubation, for example, could not be identified. This is relevant because it has been implied by some groups that non-experts should refrain from performing intubation in the prehospital setting. Reference Fullerton, Roberts and Wyse29,Reference Ryynänen, Iirola, Reitala, Pälve and Malmivaara30 Also, it was not possible to have appropriate follow-up of prehospitally treated patients to confirm with other clinical resources that the appropriate diagnosis was TBI, and not another cause of decreased level of consciousness. Reference Bossers, Schwarte, Loer, Twisk, Boer and Schober20 This lack of follow-up restricts the ability to include a more clinical relevant outcome analysis, like survival at any point of care.

The objective of this study was to know the endotracheal intubation frequency to a high-risk group of patients as those with severe head injuries in the prehospital setting. This audit will allow further research regarding the proficiency with which the procedure is performed. This will be the basis to improve advance airway management and oxygenation to head injured patients in the prehospital phase of care lead by physicians.

Conclusions

Patients with a clinically severe head injury are intubated 51.1% of the time by prehospital physicians of the SAMU service in Mexico City. Most of the patients intubated by these providers do not receive anesthetics to assist the procedure.

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.