“To write a poem after Auschwitz is barbarism.”

—Theodor Adorno (Reference Adorno1973)Footnote 1“It, the language remained, not lost, yes in spite of everything.”

—Paul Celan (Reference Celan and Felstiner2001)“One sings, dances, in order to express what one would like to say in words, but can no longer say […] Even a sigh can almost be a primitive song.”

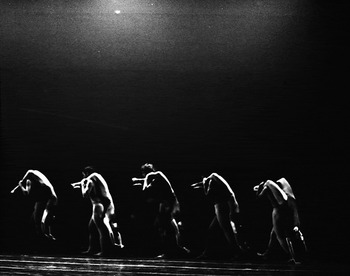

—John Cranko (Reference Cranko1974, 26)Footnote 2Scene I: The bare stage, dimly lit, reveals a single figure standing on the far right in the distance. A voice breaks the silence: “And when my father was taken out to the mound of corpses, in the snow of the alien field, the German officer screamed: Ausziehen!” – The man advances a few steps and halts. “And my father understood the verdict,” says the voice, and the man bows his head slowly, then lifts it up again, makes a quarter turn to the left and walks on solemnly, taking off his jacket and shirt, as if following the orders. “My father took off his shirt and his trousers, like someone discarding the materiality of this world,” the voice goes on, and we see the man take off his trousers. “My father took off his shoes, as on the eve of Tisha B'Av.”Footnote 3 The man stops and takes off his shoes. Another person enters from upstage right and follows precisely the same somber routine. So does a third and a fourth … one by one they enter. One by one they pause; slowly undressing with utmost concentration. In slow, processional, repetitive movements they drop their garments leaving behind them little heaps of apparel. “But when the officer saw that my father was still standing in his underwear, the black yarmulke on his head, he, the vicious one, inflicted a blow between his shoulders with his cold weapon, my father coughed and fell upon his face: as if prostrating himself before God; a deep bow to the bottom of life, and he never rose up again . . . .” One by one the men cough, contract as if hit in the back of their necks. One after another they fall into “the mound of corpses in the snow” on the far left of the stage (Photo 1).

Photo 1. John Cranko, choreographer, “To the Mound of Corpses in the Snow,” from Song of My People—Forest People—Sea. Photographers: Yaacov & Alexander Agor, courtesy of the Bat Sheva Dance Company and the Israel Dance Archive, Beit Ariella.

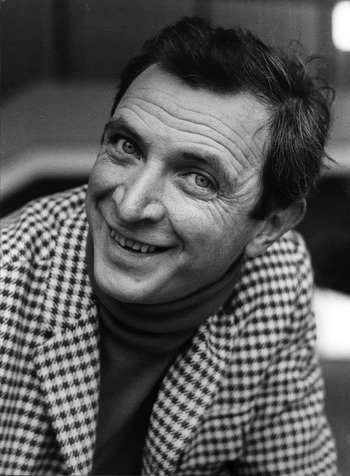

John Cranko (Photo 2) was appointed resident choreographer of the Sadlers Wells ballet at the age of twenty-three (1950) and, in 1961, director of the Stuttgart Ballet, where his international fame soared. Ten years later, at the peak of his career, the celebrated forty-three-year-old South-African choreographer came to Israel by invitation of the Batsheva Dance Company. Including a short preparatory trip to meet the dancers and outline the work, Cranko stayed in Tel Aviv for almost two months, during which he accomplished two totally contrasting tasks: the revival of his humoristic Ebony Concerto Footnote 4 and the creation of a new, utterly serious piece dedicated to the Batsheva Dance Company. Cranko's visit occurred hardly one year after a traumatic terrorist attack directed against Israelis on German soil: the 1970 kidnapping of an El-Al plane by Palestinian terrorists in Munich, in which the foremost Israeli actress, Hanna Maron (who was to play a pivotal role in Cranko's piece), was severely wounded. It may well be that this event confirmed his decision to take the theme “from death to regeneration.” According to John Percival, Cranko put a great deal of thought and preparation into his work with the Batsheva Dance Company: “He read voraciously,” as much Hebrew poetry, translated to English, French and German, as he could lay his hands on (Percival Reference Percival1983, 213).

Photo 2. John Cranko, circa 1970. Photographer: Hannes Kilian, courtesy of the Stuttgarter Ballett, Staatstheater Stuttgart.

Photo 3. John Cranko, choreographer, “My People Forest My People Sea,” from Song of My People—Forest People—Sea. Photographers: Yaacov & Alexander Agor, courtesy of the Bat Sheva Dance Company and the Israel Dance Archive, Beit Ariella.

Cranko's special interest in the project seems to have stemmed from a combination of motives, both personal (his Jewish descent, to which I shall return later, played a role) and artistic: his essential fascination with new creative challenges and a particular interest in the young, intriguing company, which had gained excellent reviews in its first German tour in 1969 (Gluck Reference Gluck2006, 97–98). Founded in 1964 by Baroness Bathsheba (Bethsabée) de Rothchild, under the patronage of the already legendary Martha Graham, the Batsheva Dance Company had by that time gained international fame and stirred up appreciable interest in professional circles. As opposed to the Israeli Classical Ballet Company and the Bat-Dor Dance Company, which, in 1971, were still in their infancy, Batsheva already had an excellent reputation, and the company boasted youth, vitality, virility, and artistic daring (Gluck Reference Gluck2006, 98–99).

Perhaps it is not a mere coincidence that Cranko's piece for Batsheva came to be known by several titles, as though its essence could not have been captured by one definitive name. The odd title chosen by John Cranko for the ballet, Song of My People—Forest People—Sea, or, by its Hebrew name, Ami-yam, Ami-Yaar, which literally means “My people [is] sea, my people [is] forest,” often abbreviated in the company's English programs as Song of My People (henceforth: Ayay)Footnote 5 comes from a poem by the acclaimed Israeli poet Uri Zvi Greenberg, which provides the soundtrack for one of the segments of the dance. The poem addresses the plight of the Jewish people in the face of persecution and violence—a theme that runs as a thread through the entire choreographic piece and ends with the writer's invocation for a miracle.

The program note of the ballet reads: “A Nation and Man Move in Parallel Cycles from Death to Regeneration.” These words imply an ambitious, epic theme, embracing no less than the entirety of Jewish history, as well as the life span of individual persons understood as if in reverse—from death to life. Such an optimistic, almost messianic prospect seems puzzling in light of Adorno's statement that “writing poetry after Auschwitz is barbarism.” Adorno's declaration, which infers a temporal breakdown in history, has been widely elaborated upon since the end of the Second World War (Rothberg Reference Rothberg1997, 45–81). It voiced a widespread feeling among philosophers, writers, and artists that since the atrocities of the Second World War, the limits of representation had to be confronted, and that the very adequacy of language in expressing the trauma of the Holocaust needed, in fact, to be questioned. “The world of Auschwitz lies outside speech as it lies outside reason,” stated George Steiner: “To speak of the unspeakable is to risk the survival of language as creator and bearer of humane, rational truth. Words that are saturated with lies or atrocity do not easily resume life” (Reference Steiner1967, 123). The year 1945 has been referred to as Stunde Null (“zero hour”; Kaes Reference Kaes and Friedländer1992, 207)—a time from which the world had to be restarted from an entropic void. But how does one speak that which has no language, and how can one dance the void, understood as that which cannot be encompassed by representation, linguistic or otherwise?

Cranko seems nevertheless to have taken on this challenge—to dance the un-danceable, and in the process of doing so he drew both on text and movement. There are some ways in which dance can be considered a representational system. The mimetic aspect of dance allows the choreographer to represent phenomena of human behavior, traits of character, and signs of class or status by movement through certain theatrical conventions. It is through mimesis and mime that dance can be considered a representation. Moreover, the narrative aspect of language is brought forth by the choreographic medium through its successive unfolding in time. Essentially, it is a combination of these two aspects, the mimetic and the narrative, that allows dance to represent, or to tell a story. “I have always wanted to compose dances without a plot,” Cranko claimed in a conversation with Walter Erich Schaefer (Cranko Reference Cranko1974, 35), yet nothing in his professional remit suggested his unconventional choice of subject matter in Ayay. Moreover, he was recognized mostly for his dramatic pieces choreographed to symphonic music. He was a master storyteller, whose ballets were often interpretations of literary texts such as William Shakespeare's Taming of the Shrew and Romeo and Juliet, or Alexander Pushkin's Onegin. In these pieces, Cranko advanced and cultivated the pas d'action as a form of operatic recitative in classical ballet. “It is currently in fashion to get rid of the old school pantomime,” he said in the same conversation, “but I was raised on mime. It's a shame it gets lost” (Cranko Reference Cranko1974, 35). Thus, Cranko conceived of himself as one of the few choreographers in his generation whose task it was to safeguard danced narrative. His choices in Ayay broke radically with his accustomed methodology. First of all, his expertise in classical ballet was hardly in evidence; second, there was no plot whatsoever in Ayay. Also unusual was the fact that he used spoken text in the ballet.

Photo 4. John Cranko, choreographer, “Still Night,” from Song of My People—Forest People—Sea. Photographers Yaacov & Alexander Agor, courtesy of the Bat Sheva Dance Company and the Israel Dance Archive, Beit Ariella.

Cranko's use of poetry as a musical score for his dance was peculiar; yet the notion that dance and poetry are closely related has been promoted since the nineteenth century by writers such as Théophile Gautier, Stéphane Mallarmé, Paul Valéry, and others, and has gradually brought about the obliteration of the mimetic aspect of dance in favor of more expressive and, in the twentieth century, abstract forms. The idea, most clearly articulated by Valéry (Reference Paul1930), that dance is like poetry, whereas ordinary walking is similar to prose, stressed the non-utilitarian aspect of poetry as opposed to the purposeful, informative intent of prose. According to Valéry (Reference Paul1930), dance, like poetry, is not meant to replace words by telling a story but rather to capture their suggestive essence as advocated by Mallarmé (Reference Mallarmé and Johnson2007). Indeed, modernist as well as neo-classical and expressionist twentieth century choreographers tended to replace old-fashioned mime by suggestive movement qualities. However, when Cranko came to tackle the text of Ayay, it seems that his unfamiliarity with the Hebrew language trapped him into a literal “translation,” i.e., into miming the words at face value and following them as though they dictated a plot. Commencing with Greenberg's expressionist prose poem “To the Mound of Corpses in the Snow,” Cranko grappled for adequate means to distill the poetic qualities of language into the language of dance. He did so by using a plethora of classical devices, temporal and spatial, common across spectra of artistic practice: balance, symmetry, repetition, rhythmical patterns, symbolic imagery, etc. Moreover, it seems that Cranko searched for the right means to tell the “history,” or rather “his-story,” of the Jewish people through that aesthetic language. He wanted to project the Jewish history toward a triumphant future and give it both a positive magnitude and direction. Yet, in order to achieve that without succumbing to kitsch or overly simplistic forms, he would have to overcome two major obstacles: the severing of narrative's integrity and the crisis of representation, both of which impinge upon language more than ever, after Auschwitz. When body language “re”-presents spoken language by mimesis, we get a representation of a representation, twice removed from reality. Such an amplified aesthetization denies dance its genuine potential to bring forth an authentic physical truth: to testify. It therefore runs the risk of being unethical when it comes to dealing with Auschwitz. How, then, are we to judge Ayay?

With reference to Theodor Adorno's statement, I propose to look at Cranko's attempt to handle these problems in Ayay through the prism of language and testimony. After following Cranko's creative process and its reception in Israel and abroad, in light of its historical context, I will follow Paul Celan, Jacques Derrida, and Giorgio Agamben, who have discussed the shortcomings of language in testifying to the horrors of the Holocaust, and theorized the fallibility of language as a system of representation at large. What one might call the crisis of language after Auschwitz is closely connected with the age-old problem of negativity, which underlies Agamben and Derrida's (Reference Derrida, Budick and Isere1987 approach to language. In other words, the difficulty that Cranko had to resolve was tinged with the inherent philosophical paradox of affirmation and negation at the same time. Spoken words—embodied language—negate (and thus suspend) their inner, ethical content in dance as in any performative act. The never-ending suspension of the voice in language constitutes the problem of philosophy, says Agamben, and “How each of us resolves this suspension is ethics” (Reference Agamben, Pinkus, Hardt, Godzich and Schulte-Sasse1991, 107). In questioning “how to dance after Auschwitz,” Cranko had to walk a fine line suspended between “what one would like to say in words” and that which “[one] can no longer say,” that is, between the articulation of language and the uttering of a sigh. I will show that his attempt to tackle the theme of the Holocaust in a “foreign language,” both in terms of speech and dance, was a courageous tightrope walk between heroism and banality—a dangerous move between a deep, ethical commitment and almost an artistic suicide. Finally I will contend that despite its troublesome reception, rooted in the inevitable failure intrinsic to language, Ayay nevertheless reflects an admirable ethical triumph.

Choreographic Process and the Hebrew Score

It was Cranko's preconceived idea to base his work for Batsheva on Hebrew text, since he was convinced that language, literature, and especially poetry were the deepest and truest expressions of the Israeli people (Percival Reference Percival1983, 213).Footnote 6 The piece was to be choreographed to a soundtrack of recited Hebrew poems, selected and compiled by him especially for this purpose. Only a few musical touches were interwoven into the verbal accompaniment, such as percussion segments by Ruth Ben Zvi (one of them composed and “xylophoned” on a set of champagne glasses), a popular song (by Dubi Zelzer), and one more traditional pas de trois to classical music (by E. W. Sternberg, sung by soprano Netania Davrath)Footnote 7 . All three Greenberg poems in the piece are from Greenberg's book Rehovot Hanahar—sefer ha'ayaliyut vehakooa'ch (Streets of the River—A Book of Potency and Force, 1951). In his essay about the latter, Reuven Shoham states that in these prose poems, “The destruction of the Jews of Europe and the extermination of the Jewish community on its soil extract from the speaker some of the most brutal expressions (Shoham Reference Shoham2003, 296). Oreet Meital contends that Greenberg harnessed his voice to the promotion of a national-political agenda. It was carefully crafted in a strong, masculine, and defying tone, “translating” his personal grief into the hegemonic terminology (Meital Reference Meital, Tamar and Lipsker2007, 257).Footnote 8

The structure Cranko chose for the ballet was that of a suite of scenes, or a continuum of quasi-“snapshots,” each following a different poem, and accordingly, a different stage in man, or nation's, life cycle. Along the way there were suffering and death (To the mound of corpses in the snow, U.Z. Greenberg), rage and bitterness (the severing of the wing, My people forest—people sea, U.Z. Greenberg), love (Song of Songs; Spread your wings, Ch. N. Bialik), hard labor (Not by chance, Ch. N. Bialik), loneliness (Alone, Ch. N. Bialik), faith (Hands of Israel, Y. Lamdan; God Lives, I. Z. Rimon), acceptance (Ich weiß, daßich bald sterben muß, E. Lasker Schüler), and an optimistic finale, set to a contemporary poem by the youngest in the line of the chosen poets, Nathan Zach: “I always want eyes to see the beauty of the world, and to praise this wondrous beauty that is without exception, and to praise the one who did it, so beautifully, fully, to praise fully, so full of beauty” (Zach Reference Zach, Feinberg and Olitzki2009).

Cranko received in advance a selection of canonical poems that reflected early twentieth century, modern Hebrew poetry, but some changes and additions, as well as the final selection and the order of succession, were worked out with the help of Israel Ouval, then a twenty-four-year-old poetry and dance aficionado. Ouval had been rather coincidentally assigned to assist Cranko by Pinhas Postel, Batsheva's general manager at the time.Footnote 9 Ouval did his best to help Cranko not only as his personal interpreter, but in fine-tuning his textual choices for the piece. It was thanks to him that Cranko was acquainted with Zach, who was considered a rebel at the time, ardently advocating the use of spoken language and free verse, as opposed to the pathos and exuberant imagery of the previous generation of Russian-born poets (Dykman Reference Dykman and Tsipi2008). Finally, Ouval also drafted the program note of Ayay, “A Nation and Man Move in Parallel Cycles from Death to Regeneration.” Ouval's preferences were intuitively guided by two main parameters: (1) poems that nominate limbs (such as hands, head, eyes, lap, etc.) including verbs that suggest movement, and (2) poems that repeat the phonemes dam (blood), adam (human being, person), and adama (earth, land). Ouval told me that Cranko was fascinated by these primordial words, whose consonance shares a common etymological origin.Footnote 10 Ouval had the impression that Cranko was spellbound by the sound of the Hebrew language and by the way words were constructed. Perhaps he intuitively sensed some similarity between the morphological system of ballet technique—his accustomed habitus—in which small building blocks are articulated and combined into meaningful utterances, and the morphological system of the Hebrew language, in which meaningful phonemes are combined as building blocks of words. However, it seemed that he delighted in the encounter with the ancient language, as a well of new poetic inspiration.

At the beginning of his work on each new scene, Ouval would accompany Cranko to the studio in order to read the chosen poem out loud and explain it to the dancers. Then Cranko would demonstrate the movements that he had thought out beforehand. He never improvised spontaneously, nor did he consult the dancers. Cranko's choreographic choices were basic and minimalist; this may have been due to his concept of the theme, which will be discussed later, but apparently also to the dancers at hand; almost all of them were late starters in the field of dance, who hardly had any classical training at all. The men in particular were strong, impudent, and renowned for their charismatic appeal, yet their technical command of the language of ballet was lacking. In this respect, they were the complete opposite from the Stuttgart Ballet stars. Cranko, on the other hand, was ignorant of modern dance technique. Consequently, the movement spectrum he could use for the piece was rather personal and elementary. The company members revered Cranko, but sneered at his choreographic choices. They regarded themselves as pertaining to a rebellious generation of elite avant-garde artists. On the one hand, they felt proud and excited about working with the great artist, but on the other hand, they resented the easy, unsophisticated movements that didn't challenge them or show off their skills. Moreover, they begrudged the predominance of the recited text, which almost deprived them of their priority as performers. It was as if they had been relegated to secondary participants in an outdated pageant that reminded them of the kind of ceremonies they had loathed at school, in youth movements, or in the kibbutz.Footnote 11

“During rehearsals Cranko was always surrounded by outsiders,” recalls Esther Nadler, then a promising young dancer in the company (whom Cranko later invited to join the Stuttgart Ballet). “I have never seen a choreographer (except, perhaps, Martha Graham, who was a celebrity and a super-star) who gathered around him such an entourage of artists from all fields of art,” says Nadler.Footnote 12 She was under the impression that this may have been for two reasons: first of all, for the sake of the work, since Cranko attempted to create an interdisciplinary piece, which involved continuous consultations with musicians, singers, actors and poets. The second reason, however, seemed to relate to a deeper psychological need. Nadler believes that Cranko felt somewhat insecure. He knew that he was treading on unfamiliar ground, touching upon a very delicate nerve. Nadler assumes that he needed the moral support of colleagues who were au courant in the local scene and who could offer an alibi for his artistic choices. In her book about the Batsheva Dance Company, Rena Gluck quotes Linda Rabin, one of Cranko's rehearsal managers on Ayay: “The project meant a lot to him. He wanted to make the best of it and was very patient. He had clear ideas, at least for some parts. I remember the first section, The Mound of Corpses and the doubtfulness of the dancers, who dreaded the audience's response …” (Gluck Reference Gluck2006, 116–17). Ultimately, Gluck herself felt that she could not participate in the piece and asked to be discharged right from the start. For her, the theme was too emotionally charged. She remembers a conversation with Cranko on the balcony of his rented flat in Tel-Aviv, where he introduced his ideas of the dance to her, and she advised him to beware, as “The subject is extremely sensitive!”Footnote 13

Photo 5. John Cranko, choreographer, “Still Night,” from Song of My People—Forest People—Sea. Photographers Yaacov & Alexander Agor, courtesy of the Bat Sheva Dance Company and the Israel Dance Archive, Beit Ariella.

Representing the Holocaust—The Israeli Context

The question of how to deal with the memory of the Holocaust was at the heart of public discourse in Israel, and has remained a constant issue of debate ever since the establishment of the state (Zertal Reference Zertal2005). As a matter of fact, the Holocaust was grasped as the immediate pretext for the establishment of the state, yet ironically, a pretext that had to be negated and denied in order to make room for the emergence of a totally new and different form of life for the Jewish people (Gertz Reference Gertz2004, 13). This new life had to be defined by apophasis: not a catastrophe, but a joy and a blessing, not marked by defeat and surrender, but a sign of defiance and victory, not ashes of extermination, but a miracle of personal flourishing and national growth. This mutually exclusive dialectic was so dichotomous that the trauma of the Holocaust needed to be practically hushed-up and suppressed by its survivors. A large percentage of Israelis have been deeply traumatized Holocaust survivors, who felt compelled to shield their mental sanity by “forgetting.” For them it seemed to be the only choice in order to get on with their personal lives and with the collective national tasks. There were even those radical Canaanites, who denied any affinity between the Jews of the Diaspora and the new Israelis (Laor Reference Laor2009). The former—Yiddish speaking, who were seen as effeminate, helpless refugees—were looked down upon by followers of the Canaanite movement, which promoted a basically secular, virile, and resourceful society for the Hebrew youth. The adjective “Hebrew” (or Hebraic) was added to numerous youth movements, newspapers, and various organizations, in order to distinguish their Israeli secular outlook from that of the “Jewish” Diaspora (Shavit Reference Shavit1987; Sheleg Reference Sheleg2010). Jewishness was out. Hebrew youth were in! The ideology of the Canaanite movement gained renewed popularity in the 1960s, especially in the cooperative settlements (in which some of Batsheva's dancers at the time had been brought up). For all the above mentioned reasons, the commemoration of the “Shoah” (Holocaust) was consistently left out of the personal, quotidian strata of life and reserved for the lofty pedestals of public ceremonies. Tribute to the memory of the six millions murdered was paid on a grand scale and invested in big monuments, but was absent from daily life.

As a result of this social and cultural background, the Holocaust was rarely tackled as a theme in art and literature during the first decade of the state. Most scholars agree on the fact that this situation of collective denial and psychological suppression started to change in 1962, during the highly publicized Eichmann trial (Fellman Reference Felman, Porter and Waters2000; Gretz Reference Gertz2004; Laor Reference Laor2009; Zertal Reference Zertal2005; Zimmerman Reference Zimmerman2002). The trial was broadcast on the radio and followed by practically every household in the country. Suddenly the wall of silence cracked, but it was still there: many survivors of the Shoah were emotionally shaken by the trial, which brought their vulnerabilities back to the forefront. The crucial step towards the legitimization and personalization of the Holocaust memory was made only after the Six-Day War (1967). In his book Leave My Holocaust Alone, Moshe Zimmerman states that, in retrospect, the readiness to acknowledge the Shoah and its significance constituted one of the major changes in Israeli culture since 1967 (Zimmerman Reference Zimmerman2002, 220–24). Although the war itself lasted only six days, the menacing pre-war period cracked the Israeli facade of omnipotence. The existential threat reawakened the Holocaust trauma and stimulated the urge to process its undercurrents in the arts. As of the late 1960s, an ever-growing number of artists (first and second generation survivors of the Shoah) challenged the canonical, impersonal representations of the Holocaust. Movies, theater plays, novels, and other art works began to offer alternative treatments of the subject, based on personal testimonies.

It is at the beginning of this new period that Cranko arrived in Israel. Hardly any allusions to the Holocaust had been made beforehand in Israeli concert dance. One exception was Anna Sokolow's Dreams, which she had staged in Israel for the Lyric Theatre in 1962,Footnote 14 which was received ambivalently. “Watching Dreams seems like reading someone's personal letters …” said journalist Ilan Reichler (Reference Reichler1962) at the time. “Touching upon these personal zones is probably what deters so many viewers who expressed their reservation about the work in speech and in writing … however it is these personal issues in Dreams that render the work honest, significant and convincing” (Reichler Reference Reichler1962).Footnote 15 Numerous other works concerned with the Holocaust memory have been created in Israel since the 1970s, yet it was not until 1994 that one of these, Aide Mémoire, by the Israeli choreographer Rami Be'er of the Kibbutz dance company, gained substantial local and international success (Aldor Reference Aldor2000, 152–153).Footnote 16

Symbolism as a Means of Representation in Ayay

Scene II, Still Night Footnote 17 : On the left hand side of the stage “the mound of corpses” is still heaped up (Photo 5). To the sound of drumming enter six women from upstage right, barefoot, dressed in identical tights and leotards. They tip-toe, revolving in a circle—gently holding hands with their arms intertwined. “Stars still sow their light,” Hanna Maron's dramatic voice narrates, as the circle dissolves and the women cautiously approach the mound and recoil from it. “Still fields are being cultivated by those whose hands have shed no blood,” the voice goes on, and the women promptly extend their arms, and then rotate their palms inwards and look at their hands, as if to acknowledge their innocence, or their guilt. The lyrical poem goes on to talk of the quiet, apparently normal life: “Still mothers tend to their crying babies,” while the women bend down and sit on the floor, in a cradling movement. The reciting pauses, yet the drumming goes on and the group suddenly discovers the mound of corpses. “Still the clock serenely beats time” … One of the women seems shocked; almost paralyzed by the sight of the corpses: she tries to get away from it and hide behind the group. “Still the world is silent,” the line is repeated twice, and the women, who formed a line and shuffled along as though ticking time, now encircle the mound of corpses. “Still night by night a dream forgives/the day's sins/but what is it, that whines without voice, Negates and never goes mute/Who is it, that questions, and prays not/only the wind howls. And our heart stopped.”Footnote 18 The line of women encloses the mound, and the women softly lie down in a circle around the men, each one putting one hand on the back of the man lying next to her and continuing to wave the other hand, as the lights dim (Photo 6).

Photo 6. John Cranko, choreographer, “Still Night,” from Song of My People—Forest People—Sea. Photographers Yaacov & Alexander Agor, courtesy of the Bat Sheva Dance Company and the Israel Dance Archive, Beit Ariella.

Photo 7. John Cranko, choreographer, “The Severing of the Wing,” from Song of My People—Forest People—Sea. Dancer: Gabi Barr. Photographers: Yaacov & Alexander Agor, courtesy of the Bat Sheva Dance Company and the Israel Dance Archive, Beit Ariella.

Does this lyrical ensemble allude to a nightmare? Are the dancers the comforting dreams? The howling wind? The cradling mothers? Yes, they are all of these. In fact, they carry out a mostly gestured illustration of the text. Language has different functions that take effect simultaneously. Jean-Paul Sartre (Reference Sartre and Frechtman1988) distinguishes between the opaque and the translucent functions of language. While the translucent function carries out the “see-through” informative agency of lexical meaning (as in prose), the opaque function corresponds mainly to the poetic aspect, i.e., that of aesthetic qualities (as in poetry). By watching Ayay, it becomes clear that Cranko approached the text from these two discrete perspectives, both of which inspired his interpretation of the verbal score: the “translucent” perspective, i.e., the plot of the poems, as mediated by Ouval, and the “opaque” perspective, i.e., their prosody, tonality, consonance, etc., which were carried across to him in an immediate manner, through Maron's recitation. Perhaps he was trying out a new way of combining the old story ballet with the abstract “plotless” dance; however, I believe that this was one of the biggest stumbling blocks of the piece. For the Hebrew speaker, the two functions automatically and intuitively converged into one; yet—because Cranko was unfamiliar with Hebrew—he tended to “translate” the semantic content into a gesticulated narrative and to regard the acoustic content as a musical score. The outcome often fell into the trap of miming the words, so that the spectator would watch what she was hearing. For example, the words “crying babies” (tinokothabochim) were conveyed simultaneously by a rocking motion; “the dome of heaven” and the “skullcap” (kipa) were given a realistic pantomime, with arms uplifted, en couronne, and then placed on the top of the head; and “the severing of the wing” (critatcanaf), which I will describe below, was literally danced with one arm only, the other one tucked under the dancer's gown.

Scene III, The Severing of the Wing Footnote 19 (Greenberg Reference Greenberg and Carmi1981): “So very suddenly, one cloudless morning, the fragrance of growth filling the air, and all the birds were flying with some sort of single wing … Woe to the man who, seeing them thus, did not pluck the grapes of his eyes and crush them with his hands!” The mound of corpses, surrounded by the circle of reclining women, is still there, on left hand side of the stage. A strange figure, some kind of a specter, appears on the right: completely draped in cloth, which covers her body as well as her head (Photo 7). Her broad, sudden movements stretch the material with which she is covered and produce a line of sculpted poses at the beginning of her dance, vaguely reminding the spectator of Martha Graham's Lamentation. When the word “wing” is sounded, the figure sharply extends one arm underneath her drape. The other arm remains tucked close to her chest. She then begins to circle her head in an ecstatic, accelerated tempo; her entire upper body—still only one extended arm—joins in the woeful movement, which brings her down to the floor. “Even the birds, they themselves, do not know who cut off their wing. So very suddenly, and they were flying through the air, thus tilted to one side. And no blood drips, and there is no sign that every bird once had two wings, to carry.” A tilted run-around ends in a pause, and a sudden unveiling of the dancer. Now she moves “from over here to over there” in desperate, not particularly stylized movements, brandishing her drape behind her, torso uplifted and the eyes raised. “Yearning hearts from over here to over there. Now over there is no more. By the word of God, as if in a dream, the wing was cut off, and then He sealed up the gash.” More and more, the dancer seems to be overtaken by the rhythmical reading and the emotional pathos of the reciting. She whirls around toward the mound on the far left, throws off her drape, and shows off her bent arm, “the severed wing” (Photo 8). As the last words of the poem resonate,Footnote 20 the dancer slowly flutters down onto the mound.

Photo 8. John Cranko, choreographer, “The Severing of the Wing,” from Song of My People—Forest People—Sea. Dancer: Gabi Barr. Photographers: Yaacov & Alexander Agor, courtesy of the Bat Sheva Dance Company and the Israel Dance Archive, Beit Ariella.

Rather than portraying characters on stage, Cranko attempted to depict abstract qualities that correspond to the poem's meaning. In “The Severing of the Wing,” the veiled persona is in fact the symbolic incarnation of God—the divine presence or shechina in Hebrew, which is being mutilated. God, explains Shoham (Reference Shoham2003) in his analysis of the poem, has now become a God “of the gentiles,” and this God has planned the catastrophe. “Because there is / God in the world but there is no God for Israel” (Shoham Reference Shoham2003, 296). The entire choreographic style is highly symbolic, with movements iterating what is being said. A symbol, literally meaning “that which is thrown or cast together,” fuses two halves of a broken token into one, to form a whole. Walter Benjamin (Reference Benjamin and Osborne1977) thought the symbol (as opposed to allegory) was alien to our time, in the sense that the whole is alien to the fragmented, broken reality for which modernity stands. It seems to me that Adorno's (1949) notion, that “writing poetry after Auschwitz is barbarism,” points precisely to the absurdity of the symbol at a time that cannot provide any solid frame of reference. The “whole,” as a unity between language and reality in all its aspects, has fallen apart. If the symbol, as a tool of poetic discourse, alludes to the possibility of mending that which has been broken into pieces, of rectifying the out-of-joint world after the Holocaust, then poetic (symbolic) language itself is unethical. From here on, content and its means of expression can no longer integrate their elements into a totality. Furthermore, integrating history into a coherent whole by stringing events onto a continuous narrative chain is doomed to become a cliché, kitsch, forgery, vulgarity; hence, it becomes “barbarism.”

Photo 9. John Cranko, choreographer, “The Severing of the Wing,” from Song of My People—Forest People—Sea. Dancer: Rina Schenfeld. Photographer: R. Falligant, courtesy of the Bat Sheva Dance Company and the Israel Dance Archive, Beit Ariella.

Reception of the Work in Israel

In 1971, I was a young soldier serving in the Israeli Defense Forces. I was also an aspiring professional dancer, as well as a poetry lover, who had just won first prize in a national poetry-reciting contest. Of course, all of Ayay's constituent elements were extremely close to my heart: the dance, the poetry, and its dramatic reciting by Hanna Maron. Like many others in the audience, I would have agreed with Cranko's biographer, John Percival, that “the work was quite extraordinary, like no other, and extremely moving” (Percival Reference Percival1983, 212). It almost felt like an historical moment or, at any rate, an unforgettable event: the poems seemed to have crowned the piece with an aura of intellectual artistry, far beyond mere entertainment. Furthermore, they made the piece “ours.” Not only were they in our own language, but they were by and about us, addressing our actual history. However, in spite of the excitement, something about the ballet caused resentment. What was it that provoked such controversy? Could it have been associated with the problems outlined above?

“I still feel guilt ridden and ashamed when I remember how I resented the solo [The Severed Wing] which Cranko choreographed for me,” says Rina Schenfeld, former Batsheva soloist.Footnote 21 As for most of the dancers, the work seemed to her like a pageant (Photo 9). Indeed, the doubtfulness, skepticism, and resentment of the dancers was at least partly justified by the work's reception in the Israeli press. The Israeli critics were impressed, but far from enthusiastic. Miriam Bar of the Davar daily paper praised the work in general. She described it as “an enormous weave of fragments, loosely connected to one another, yet aiming to produce a continuum of almost visionary beauty”; but she declared a strong reservation concerning the first image: “There are still limits … the death camp cannot be presented in every form to an audience in the Nachmani auditorium that includes survivors of the very same camp …“(Bar Reference Bar1971). Perhaps, she added, it can be done with words, or in a painting, but certainly not with “staged insinuations” (Bar Reference Bar1971). Michael Ohad (Reference Ohad1971) of the Haaretz newspaper wrote that “the performance's flaw lies in its richness.” He agreed with Bar that the shocking bluntness of the undressing men, dropping dead one by one in the opening scene, might have been a mistake, and yet he argued that “this is the most important dance premiere of the year” (Ohad Reference Ohad1971). Avner Bahat (Reference Bahat1971) of Al Hamishmar regarded it as: “Brave yet quite embarrassing. Cranko tried to create an Israeli dance but produced an absurdity. For the first time there's some Israeli flavor in the Batsheva Company, and it's produced by a foreign choreographer. It is understandable: people coming to us from the outside are more sensitive to our uniqueness than we, who experience it as a daily reality.”

Photo 10. Actress Hanna Maron, by Israeli Educational Television. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons - https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hanna_Maron_paints_-_Krovim_Krovim.jpg#/media/File:Hanna_Maron_paints_-_Krovim_Krovim.jpg.

Reception Abroad, Changes, and Reconstruction

Cranko stipulated that Hanna Maron's recitation should always accompany the ballet, and that the Hebrew score should never be translated (Photo 10). Althogh Cranko regarded Maron's voice as “music from the soul” (Percival Reference Percival1983, 213), this stipulation caused a problem for spectators abroad, since not many in the audience understood the Hebrew words. Nevertheless—because of or despite this fact—foreign dance critics also sensed that the piece had somehow missed its mark. During Batsheva's American tour in 1972, many thought the piece was “a strange maverick” (Peters Reference Peters1972). Clive Barnes (Reference Barnes1972), the New York Times critic, wrote sarcastically:

With the oddly named Song of my People—Forest People—Sea, we had the even odder spectacle of a well-known classic choreographer, John Cranko, making his debut as a modern-dance choreographer. . . . The modern dance feel was surface thin. There were certainly adroit moments, but even these were not helped by the background, consisting of Israeli poetry, being chanted in the original language, which deflected even the work's shafts of theatricality.

Deborah Jowitt (Reference Jowitt1972) of The Village Voice described it as wavering “between being a thirties tract dance and a romantic ‘modern’ ballet.” “What we get,” she added, “is a lot of excitement and possibly the controversy it will generate” (Jowitt Reference Jowitt1972). Dorothy Samachson of the Chicago Daily News also deemed the work as agitprop. She wrote, “The ballet was too complicated, with so many starkly uncompromising modern designs, symbols and group patterns, that the entire work had the look of a rather old fashioned patriotic pageant” (Samachson Reference Samachson1972). Linda Winer (1972) of the Chicago Tribune criticized it as “. . . . movement abstractions that never do more than reflect clichés … with a filler—pose—filler motif ….” But perhaps the harshest criticism of all was by John Brod Peters (Reference Brod Peters1972) of the Saint Louis Post, who claimed that “[P]olitical and ethnic propaganda was laid on the audience with a heavy hand and reminded this reviewer—who admits to his being an outsider both ethnically and linguistically—of the hyper political performing arts of totalitarian countries.”

At some point during William Luther's tenure as artistic director of the Batsheva Dance Company (1972–1974), he foreshortened Ayay into a version that lasted only twenty minutes as opposed to the original fifty (Percival Reference Percival1983, 217).Footnote 22 Some of the American critics who reviewed the work during these years state that the choreography consisted of six parts, others mentioned ten, and some quoted the original number of fourteen. However, the entire work was remounted on the company's tour to Canada and the USA in 1978, after it had been restored to its full length by Paul Sanasardo, Batsheva's artistic director at the time, with the help of Moshe Romano and Rahamim Ron. Sanasardo liked the piece and regarded it as a signature piece for Israel. In fact, he had been familiar with the ballet since the time of its conception, having worked in Israel for the Bat-Dor Dance Company in 1971, and being present at its premiere. Today he describes it as “A very beautiful piece; a powerful work of great simplicity, purity and sincerity; a theatrical drama which doesn't use any ballet, or any tricks and acrobatics.”Footnote 23 Ayay even inspired Sanasardo's own creation of The Spirit of Babi Yar (1980), a dance for Israeli television based on Yevgeny Yevtushenko's poem “Babi-Yar,” about the Holocaust, and set to music by Dmitri Shostakovitch.Footnote 24 As far as Sanasardo remembers, Cranko's Ayay was very well received in the 1978 tour to the USA and Canada. Nonetheless, a New York Times review written in 1982 still regards the piece as odd:

Ami Yam Ami Ya'ar (Song of My People—Forest People—Sea), which Batsheva first offered here in 1972, is a real curiosity, for it is one of the few modern-dance works by the late John Cranko, a classical choreographer best known as the director of the Stuttgart Ballet. . . . Despite its sincerity, Mr. Cranko's work never achieves eloquence, principally because it is so fragmentary. Fourteen danced poems may be a few too many and, since there is a pause between each, the choreography never gains momentum. (Anderson Reference Anderson1982)

Did Cranko indeed misstep by forsaking his own language? Did he mistakenly, or perhaps ironically, stray back to the patterns of pre-Auschwitz German Chortanz, or Ausdruckstanz? Ayay has never been mounted in Israel after the early 1970s, and one wonders whether our point of view would have changed if we had seen it today. Until recently, only a very shabby, hardly visible, filmed version of a studio rehearsal and fragmentary footage, shot on outdoor locations as a concise promotional televised version of Ayay, has been available to researchers. However, a full and adequately useful filmed version of the piece surfaced in the process of compiling the new Batsheva Archive.Footnote 25 The document, by an unknown photographer, challenges us to take a fresh look at the piece and question the way in which Cranko negotiated the problems it presented: first and foremost, the problem of language.

“Language, in Spite of Everything”

Against Adorno's widely contended declaration that poetry after Auschwitz is barbarism, or perhaps as a consequence of that declaration, I feel compelled to compare it with another assertion by the Jewish German-speaking poet, Paul Celan. In his often quoted speech, on the occasion of being awarded the Bremen Literature prize in 1958, Celan said:

Reachable, near and not lost, there remained in the midst of the losses this one thing: language. It, the language, remained, not lost, yes, in spite of everything. But it had to pass through its own answerlessness, pass through frightful muting, pass through the thousand darknesses of deathbringing speech. It passed through and gave back no words for that which happened; yet it passed through this happening. Passed through and could come to light again, “enriched” by all this. (Celan Reference Celan and Felstiner2001, 395)

Whether or not Cranko was familiar with Celan's speech, it appears that he had intuitively clutched at language when facing up to his colossal choreographic challenge. The abstract God of Israel is a speaking God, a God whose absence is present in language, and the “word”—the manifestation of absence—is perhaps the most distinctive mark of Jewish identity throughout the generations. It is therefore hardly surprising that the one “thing” that remains “safe and sound amid all ruins,” as Celan put it, was now applied as the “logos” or cornerstone of Cranko's piece. Unlike his previous pieces, this time Cranko did not consider words as a mere inspiration, or as a point of departure, but as a partner—or rather, a rival—whom he had to confront throughout the work. Cranko made an “alliance with the word” in the biblical sense of this expression, to which I shall return later. This, however, did not only declare his intent to deal with his own fragmented Jewish identity, but, like any “incision,” bore the stamp of mutilation, which meant that his whole project engaged in a lethal struggle for life or death.

Bearing in mind this notion of life or death, I would like to suggest that in Ayay, Cranko turned his back on both performance categories: that of presentation, which remains within the factual sphere of documentation, and that of representation, which transfers us to the illusory by using mimetic substitutes. I believe that in this case Cranko was compelled to resort to a third category, that of testimony. Testimony has become a constitutive theoretical notion in our time, “an era of testimony,” as Shoshana Felman (Reference Felman, Porter and Waters2000) called it. Neither an actual presentation, nor a reenacted representation, testimony is concerned with the personal, unmediated experience, which evades any possibility of representation and undermines all knowing. “The value of testimony,” says Giorgio Agamben, “lies essentially in what it lacks; at its centre it contains something that cannot be borne witness to” (Reference Agamben and Roazen1999, 34). According to Agamben, the only authentic testimony after Auschwitz is the mute testimony of those stripped of their human identity, those who, by their very being, personify the collapse of the human into the non-human.

Photo 11. John Cranko, choreographer, “To the Mound of Corpses in the Snow,” from Song of My People—Forest People—Sea. Dancer: Hugh Appet. Photographers: Yaacov & Alexander Agor, courtesy of the Bat Sheva Dance Company and the Israel Dance Archive, Beit Ariella.

Let us return for a moment to the opening scene of the ballet: “Ausziehen!” commands the officer in Uri Zvi Greenberg's poem, and the alien sound stabs the spectator in the stomach. The poet deliberately left the German word untranslated, emphasizing its Unheimlichkeit.Footnote 26 He thus disrobed it of its identity twice: first, by transplanting it into the Hebrew poem, extracting it from the German context of Auschwitz; and a second time, by keeping it in its original language and alienating it from the Hebrew context of the poem. It becomes a “strange maverick” indeed: a specter, a non-entity—a bare witness. Cranko, too, stripped his dancers bare twice—not just of their clothes, but also of their dancer's personae: their physical vitality, their confident posture, and their dependable technique. Just as Greenberg inserted the foreign word into the flesh of the Hebrew corpus, estranging it from its context, Cranko challenged his dancers and audiences alike, by estranging them from the choreographic scene. By doing so, he forced them to bear testimony to the catastrophe, to that which cannot be articulated or danced. If dancers are silent witnesses by definition, Cranko did not stop there. In order to uproot them from the categories of presenters or re-presenters, he aimed, right from the opening scene, to dismantle their identity as dancers: to deprive them of their habitual language of dance. Lawrence Langer, scholar of Holocaust literature remarks that, “[A]n essential characteristic … of almost all the literature … is not the transfiguration of empirical reality … but its disfiguration, the conscious and deliberate alienation of the reader's sensibilities from the world of the usual and familiar … to such a degree that the possibility of aesthetic pleasure as Adorno conceives of it is intrinsically eliminated” (quoted in Schlant Reference Schlant1999, 8).

Could it be that the dislike, even alienation, expressed by some of the dancers stemmed from their feeling of unease as “non-entities”? Moreover, is it possible that the lack of “aesthetic pleasure” expressed by some of the work's critics stemmed from their feeling of unease in being committed to the distressing state of witnesses?

“Cranko wanted no expression, no pose,” said Moshe Romano, Batsheva's rehearsal director at the time, who kindly shared his experiences with me. “He asked the dancers for simplicity, the utmost humaneness of men walking their final path.”Footnote 27 But the film documentation makes it clear that most of the dancers wanted nothing more than to perform and show themselves off at their best as dancers. They obviously resisted the demand to become “cadavers.” “There was tremendous resistance,” recalled Romano, echoing yet again the general discomfort with the dance: “And I suffered twice: once because the dancers were not cooperating and again because I felt bad for John … the dancers were making a mockery. I choked. It was one of the last straws that drove me to leave the company.”

Song of My People—Shibbolet for John Cranko

John Cranko was described to me by those who knew him as a man of contrasts: on one hand he was a lonesome, tormented, and sensitive person, who shut himself away in his apartment and drank heavily; on the other hand, he was a lively, involved, and intense man, who broke plates in a Greek bar on Hayarkon Street in Tel Aviv and almost got himself into a fight. He was a man who loved the Mediterranean temperament but suffered from the Mediterranean heat, a man who took antibiotics against his skin inflammation but kept on drinking. John Percival quotes Domy Reiter-Soffer, who was concurrently choreographing for the Bat-Dor Company, as saying that in a moment of crisis, Cranko confessed:

Do you know that I have Jewish blood in me, in fact a lot of Jewish blood in me? Too much Jewish blood in me to ignore that part of me, and the strangest thing about it is, here I am in Germany promoting and helping to build dance in the very country that helped to exterminate that part of me. In fact if I was living in Stuttgart then I would have ended in some god dam oven. (Percival Reference Percival1983, 216)

Cranko was, in fact half Jewish, on his father's side.Footnote 28 Many times he wanted to quit and get away from the entire project. When the piece was finally done he said: “Well, I can go now, I've done my bit. I've done what I needed for this part of me that belongs here” (Percival Reference Percival1983, 216).

Photo 12. John Cranko, choreographer, Song of My People—Forest People—Sea. Dancers: (center) Nurit Stern, (right) Hugh Appet, Gabi Barr, Yair Lee, Ehud Ben David, Eve Walstrum, Rina Schenfeld, Esther Nadler, Robert Pmper, Yael Lavy, Yair Vardi, Laurie Freedman, and Rahamim Ron. Photographer: R. Falligant, courtesy of the Bat Sheva Dance Company and the Israel Dance Archive, Beit Ariella.

These stark words attest to a deep sense of duty, and also to a strong feeling of belonging that goes far beyond any business obligation, artistic mission, or even a friendly token. It is a serious commitment, Cranko's own commitment to testimony per se:

To bear witness is thus always … in order to address another. This capacity to address is very important—it is an appeal to another, to other human beings, and more generally an appeal to a community. To testify is in this sense always metaphorically to take the witness stand, and the narrative account of the witness is always implicitly engaged both in an appeal and in an oath. In other words, to testify is not merely to narrate but to make a commitment, to commit oneself and to commit one's narrative to others. (Caruth Reference Caruth2014, 322)

The hybrid dance that Cranko created could be viewed as a “sigh,” to use his own words, or as a kind of Muselmann in Agamben's words, undermining any putative taxonomy and defying, one by one, every dance category current at the time: classical ballet, modern dance, folk dance, theater dance, and even the pageant. Yet it testifies not only to a professional search for a language to utter that which cannot be articulated, but also to a personal grappling for an integrated identity; it bears testimony to Cranko's desperate attempt to “speak up” and to mend, through language, his own torn and tormented self. As the scholar of Holocaust literature Alvin H. Rosenfeld has observed, speech “may be flawed, stuttering, and inadequate, but it is still speech” (quoted in Schlant Reference Schlant1999, 8).

At this point, I would like to turn back to the problem of language, this time by virtue of Derrida's (Reference Derrida1986) essay, “Schibbolet: For Paul Celan,” in fact his only Hebrew title. Derrida's complex reading can be summed up this way:

On the one hand language, as something we are born into, an alliance that marks us physically and mentally, can function like the cut of circumcision to recall us back to our alliances. At the same time it is the means by which we turn the cut into a figure, a means by which access is offered to the other person who stands outside our alliance. (Hammerschlag Reference Hammerschlag2010, 223)

At the center of this essay is the biblical story of a “linguistic trick” by which one of the twelve tribes, the Giladites, won the war against their brethren, the Ephraimites.Footnote 29 The trick involved a password, namely Schibboleth (“ear of corn” in Hebrew), which the Giladite guards made the attacking Ephraimites speak out, if they wished to be transferred across the Jordan in their escape. However, the Ephraimites pronounced the word differently from the Giladites (they would say “S” instead of “Sh”), because their regional dialect lacked the /ʃ/ phoneme. The Ephraimites had no choice: they had to cross the Jordan, and since nobody would carry them across, they had to speak their language even at the peril of perishing by their own utterance. Thus, the technical aspect of language—the way in which one organ (the tongue) touches another (the oral cavity)—incriminated the Ephraimites and literally condemned them to death.

How does Derrida's reading of Celan support this interpretation of Ayay, as a testimony to a linguistic crisis? How does the double edge of language urge us to reconsider our critical perspective on this ballet? It seems that by trying to consolidate his alliance with the Jewish people and by turning it into a dance figure, a means of access for others, Cranko chose to capitulate to the unfamiliar linguistic procedure of his own brethren. On the banks of the river Jordan, on the threshold of “passing” (for an insider) and exposing himself (as an outsider), Cranko tried to reconcile his own identity through the very medium, which, on the one hand, marked his alliance, and on the other hand, prevented him from realizing it. It is precisely by turning into its own stumbling block and collapsing as an aesthetic object that the piece challenges us to suspend our aesthetic judgment and reconsider it as an ethical achievement. Like the Ephraimites, Cranko was drawn into failure by his/their own tongue. Here too, as in the biblical story, the very same linguistic procedure carried with it at once the prospect of redemption and that of prosecution. Here, too, it was the articulation of language, the necessity to perform it, which “condemned” him.

And it was not just the use of the Hebrew language that had so complicated matters. It had also to do with the very medium of dance. The balletic dialect of the language of dance which Cranko mastered would have been inadequate, not only because it could not have testified to the calamity of Auschwitz, but because it was so different from the modern dialect in which the Batsheva's company was trained.

John Cranko died on a transatlantic flight only two years after he had completed Ayay. The piece remained unique within his choreographic corpus, and with it the sense of puzzlement for those watching it today. However, it seems that today the work deserves rethinking from a different perspective. Its awkwardness, as this article has suggested, does not have to be received with aversion or contempt. On the contrary, the failure of language seems to be the natural setting for this unique piece. Rather than a stain on Cranko's career, I consider it a badge of honor, adorning the chest of a brave fighter and commemorating his utopian goal to integrate all his identities—as a person, an artist, a choreographer, citizen of the world, and a descendant of the Jewish people—all in one tongue, united under this odd title: My People Sea, My People Forest (Photo 12).

Testimony, as an artistic category, has the potential to collapse aesthetic judgment by exposing it as tasteless and irrelevant. The aesthetic field, within which the work of art operates, loses its grip on the work, which is thus paradoxically left to perform within the expanse of language: reaching out toward the horizons of ethics. As a matter of life and death, failure might be an inevitable injury we are all doomed to suffer, as we struggle with language in an age when the impossibility of telling a story may be the only possible way to tell it.