“Oh, home of tears, but let her bear this blazoned to the end of time: No nation rose so white and fair, none fell so pure of crime.” So reads the stanza from a poem popular in the South during the Civil War engraved on a Confederate soldier statue unveiled in 1911 on the lawn of the Cooke County courthouse in Gainesville, Texas (Figure 1). It is one of two Confederate statues long on display in the city of some 16,000 some ninety miles north of Dallas.Footnote 1 This larger-than-life soldier, standing high upon a column, towers over an important public space. It is among many Confederate monuments that long occupied public spaces across the United States, often with little local debate, despite their often white-supremacist inscriptions.

Figure 1. A 1911 statue of a Confederate soldier on the lawn of the Cooke County courthouse in Gainesville, Texas (2020). All photographs by the author unless otherwise noted.

In summer 2017, protesters in Charlottesville, Virginia, and elsewhere across the United States began demanding the removal of Confederate monuments. These demands reflected the simmering tension over the meaning of historical statues in public places and who determines their continued presence there.Footnote 2 The statues under siege are often—but certainly not only—to be found in the American South. Many of them were donated by the United Daughters of the Confederacy, who propagated the myth of the “Lost Cause,” the belief that the Confederate cause was just and heroic, a defense of states’ rights, not centered on slavery (Figure 2).Footnote 3 Protests subsequently expanded to include demands for the removal of other statues representing a particular narrow, often racist version of American history.

Figure 2. Civil War Memorial (left; 2017), gifted by the United Daughters of the Confederacy, being removed from its site in Kansas City, Missouri. Empty pedestals in New Orleans, Louisiana and Memphis, Tennessee (both 2018). On the former stood an equestrian statue of Confederate General P. G. T. Beauregard; the latter formerly held a statue of Jefferson Davis. The Davis pedestal was removed to a “secure location” in late July 2018.

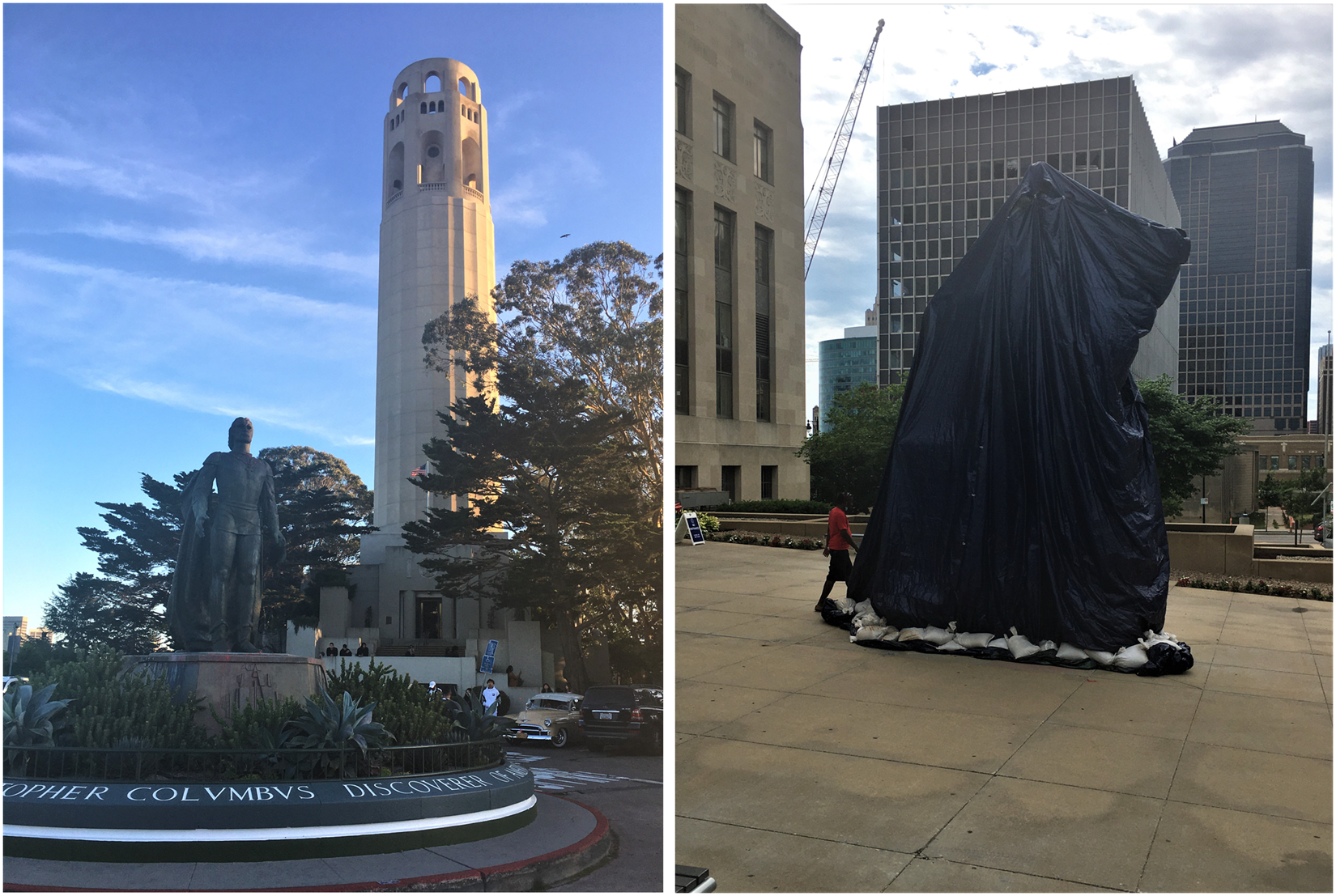

Other statues include the larger-than-life-sized Christopher Columbus (Figure 3, left), who had stood atop San Francisco's Telegraph Hill in the shadow of Coit Tower since 1957, and the equestrian statue of President Andrew Jackson before the Jackson County courthouse in Kansas City, Missouri (Figure 3, right). The San Francisco Arts Commission had the former removed in June 2020, while the latter remained shrouded in black plastic until the city fathers decided what to do with it, which was to add an explanatory plaque and let the voters decide in the November 2020 election, when they chose to keep it.Footnote 4

Figure 3. A 1957 statue of Christopher Columbus (left, 2019) in San Francisco, California. Equestrian statue of President Andrew Jackson (right, 2021) shrouded in black plastic before the Jackson County courthouse, Kansas City, Missouri.

The protests resulted in varying outcomes for the Confederate statues. They were boarded up, vandalized, or taken down in the dead of night, sometimes by protesters, other times by local authorities. In some cases, protesters called for statues of other less divisive figures to replace these monuments; in others, the pedestals remain empty or have been removed altogether. Pitched battles over statues in public places is neither a new issue nor a particularly American one, as students of Habsburg Central Europe well know. Today's statue war in the United States got me thinking about the statue war in the Bohemian lands just more than a century ago, when Czech Legionnaires, war veterans who were either demobilized or active-duty soldiers, and German-speaking citizens of the newly created Czechoslovakia battled over statues of the reforming, enlightened-absolutist Habsburg emperor Joseph II. More often than not, the Legionnaires won these battles, knocking the statues off their pedestals and otherwise damaging them.

Before continuing, I would like to expand a bit on the Legionnaires. Their members included volunteers, deserters, and those relatively few Czech soldiers who left Russian POW camps to fight in paramilitary organizations, the Legionnaires, on the side of the Allies across several fronts during wartime.Footnote 5 About 90,000 Legionnaires returned in waves to Czechoslovakia after the war, the last of them arriving home in 1921. These men formed the backbone of the new state's military, both officers and rank and file. They also played an outsized role in the Czechoslovak bureaucracy.Footnote 6 Celebrated as the first citizens of the republic, military men whose army was older than the state, Legionnaires were transformed into military heroes in Czechoslovakia between the wars. This owed to their national military exploits—above all, to their prowess against the Habsburg military in the July 1917 Battle of Zborov on the eastern front.

The Legionnaires were an extremely important constituent element of the new state's nationalist mythology/genealogy of Czechoslovak democracy (Figure 4). In fact, they helped construct this mythology because they were involved in filmmaking during the war. They performed a function similar to that of Czechoslovakia's World War I propaganda in other media, giving, as Alice Lovejoy has written, “discursive shape to a state that did not yet exist.”Footnote 7

Figure 4. Illustration showing T. G. Masaryk with Legionnaires from all the fronts, “To your health, Father Masaryk!” Jan Dědina, Pravda vítězí: Deset československých vlasteneckyých zpěvů (Prague, 1926).

In this talk, I want to revisit the extralegal removal of the Joseph II statues against the background of the continuation of war in the European east following the 11 November 1918 Armistice on the western front. Despite the Armistice, there was no immediate cessation of violence in Central and Eastern Europe. Rather there was revolution, counterrevolution, ethnic conflict, and civil war between 1917 and 1923.Footnote 8 I am situating the Legionnaires’ attacks on the Joseph II statues in the context of the widespread social unrest and violence that followed the collapse of multinational empires of Central and Eastern Europe during and immediately after World War I.

The national clashes I discuss here constituted part of the building of the postwar Czechoslovak order, in which at least some people considered physical assaults to be a legitimate tool of political struggle. Peaking with the statue war in November and the short-lived general strike the following month, the year 1920 was one of widespread economic, ethnic, and social strife in the First Czechoslovak Republic.Footnote 9 The ongoing unrest in immediate postwar Czechoslovakia is a subject that has only recently begun attracting significant historical attention, having heretofore been overshadowed by the bloodier revolutionary violence elsewhere in postwar Central Europe—for example, in Germany and Hungary.Footnote 10 Certainly, as Czech historian Zdenĕk Karník reminds us, during much of this period the Prague government functioned more as a “Czech national dictatorship” than a thriving liberal democracy.Footnote 11 Analyzing the violence in the early First Czechoslovak Republic—some of it popular, some aided and abetted or even orchestrated by Czech Legionnaires—also helps us better understand the sporadic Czech-German national violence between the wars as well as the relative ease with which Czechoslovakia lurched into authoritarianism in the late 1930s. The unrest in Czechoslovakia between 1918 and 1923, although very different, can also serve as a cautionary tale for the contemporary United States.

The parallels are quite direct. Most of the problematic Confederate memorials in the United States were unveiled during the early 1900s, in the era of Jim Crow and the rising popularity of the Ku Klux Klan, or during the 1950s and 1960s, in a time of increasing demands for equal rights (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Confederate monuments in Front Royal and Luray, Virginia (both 2010).

Similarly, most of the Joseph II monuments were put up long after the events they commemorated, in an era of national tension between Germans and Slavs in the Habsburg monarchy. Again, like the Confederate monuments, these statues were often the gift of private individuals or organizations to towns and cities to be located on public space, their upkeep to be paid from public coffers. Finally, the Joseph II statues also possessed potential political power that was unleashed in an era of national conflict.

I am not sure when I first became interested in Habsburg emperor Joseph II, the statue—not Joseph II, the man. It was sometime in the early to mid-1990s, and I suspect it was in Cheb, formerly Eger, in far western Bohemia. I have a vague memory from my graduate student years of an archival employee furtively leading me down the hall of the district archive and out the back door, and there he was, Ozymandias-like: one-armed and lying face down in the mud in the archive's back garden. When I returned to Cheb after 1989, I returned to the back garden. This time, Joseph II stood until 2003 on a makeshift pedestal, together with statues of several stray communists (Figure 6, left). It was then that members of the local Rotary Club had the statue of the emperor spruced up and moved to nearby Františkovy Lázně/Franzensbad, where he now stands on a very posh pedestal before one of the local spas, Dvorana Glauberových Pramenů (Figure 6, right). His right arm has yet to be replaced. More on that arm later.

Figure 6. Joseph II statue in the back courtyard of Státní okresní archiv Cheb (left, early 1990s) and in Františkovy Lázně/Franzensbad (right; credit John Paul Newman, September 2021).

The Emperor Joseph II statue in Cheb/Eger had plenty of company. Joseph II busts and statues still dot the Lower Austrian countryside. These are among the many that sprang up, mushroom-like, throughout the Bohemian Lands and Lower Austria, as well as in the predominantly German cities of Celje/Cilli, Maribor/Marburg, and Ptuj/Pettau in Lower Styria beginning in the early 1880s. They were all part of an informal, liberal “Joseph II movement,” which was meant to commemorate the November 1881 centenary of the abolition of Leibeigenshaft (serfdom). In Bohemia, as elsewhere in the monarchy, it was German speakers—individuals or organizations—who funded the statues, which were then given over to the local government after they were unveiled. The speakers at the unveiling ceremonies both elaborated the emperor's deeds and asserted his affinity for Germans. German nationalists made increasingly explicit “German” claims on the people's emperor in various ceremonies and commemorations—and sometimes even protests—at the statues. No other figure became such a ubiquitous part of the built landscape and so much a part of collective German memory of a mythical golden past in the Bohemian Lands as Joseph II.

Many of the early Joseph II statues, often holding one of the emperor's modernizing patents in their hand, looked very much alike. Why was this, you might ask? It is because, like many US Civil War monuments, they were products of the monument industry. Designed by sculptor Richard Kauffungen and available by catalog, the Joseph II statues, in bronze or iron, could be scaled down and otherwise modified. There were also Joseph II busts as well as obelisks for those towns and villages with more limited budgets. So many Joseph II statues were ordered in the early 1880s that their production was something of a sideline for the Fürstlich Salm'sche Eisenwerke in Blansko, Moravia, which otherwise produced award-winning steam engines.

Like the monuments themselves, the Joseph II inscriptions were similar. The emperor was often lauded as the “Esteemer of Humanity,” as he is on the bust in the Schlosspark in Gmünd, Lower Austria, just across the border from České Velenice, formerly Unterwielands, which Czechoslovakia seized from Lower Austria under the Treaty of Saint Germain in 1919. The exclusive claims German speakers made on the memory of Joseph II are apparent in the solely German-language inscriptions on the statues, even in areas of mixed Czech-German population. The Germans of the monarchy, especially the Bohemian Lands, overcame other, earlier interpretations of Joseph II, transforming him in the popular imagination from the “Esteemer of Humanity” into the “Esteemer of Germandom.” Claiming his memory exclusively for the German people served to nationalize not only the emperor but also the Habsburg dynasty, thus helping to weaken this important centripetal force of the monarchy.

In the monarchy's last decades, Bohemian German-speakers often met at the statues before going off to do battle with Czechs. For example, during the protests over the Badeni Language Ordinances in 1897, the statues of this supposedly universal Enlightenment emperor more and more functioned to lay German claim to increasingly nationally mixed territory. Indeed, these statues formed a kind of barrier in bronze and iron to separate “German” areas from “Czech” ones as Czech-speaking workers moved into the rapidly industrializing German regions. The Czechs sometimes responded by attacking Joseph II monuments during times of Czech-German tension, as they famously did in southern České Budějovice/Budweis on the twenty-fifth anniversary of the local bust's unveiling in 1908.Footnote 12

Soon after the war's end in early 1919, the Joseph II statues in Lower Styria, now part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, were taken down with relatively little fuss.Footnote 13 But the fate of the Joseph II statues in the Bohemian Lands differed markedly. Following the foundation of Czechoslovakia on 28 October 1918, jubilant Czechs began removing symbols of Habsburg rule, above all the double-headed Austrian eagle and statues of Habsburg historical figures, as they sought to consign them to the dustbin of history. At the same time, politicians in the predominantly German-speaking border regions declared these areas part of newly founded German-Austria. Their existence proved ephemeral as the Czechoslovak troops occupied these border regions in late 1918. The military would remain in the border regions, even expanding the number of garrisons, treating the borderlands as occupied territory.

After decades of increasing politicization, it is no surprise that the fate of Joseph II statues aroused national conflict after 1918. In the new Czechoslovakia, these statues and the national conflict they engendered posed a danger to the nascent multinational state, one that was ruled as a nation-state.

Angry words exchanged in a dance hall or pub, casual name-calling, failure to show sufficient respect for the Czechoslovak national anthem, or graffiti on a Czech-language poster might provide the impetus for an attack on a Joseph II statue. The Legionnaires instigated most of the assaults on these statues. The prevalence of the attacks, and the government's relative inability or reluctance to rein in the violence, reflected the new state's difficulties in consolidating power. Sporadic conflict over the Joseph statues throughout the Bohemian Lands began in 1919, reappeared in the summer of 1920, and escalated in the autumn, culminating in the so-called Statue War of late October and early November, when many remaining Joseph II monuments in the borderlands—and elsewhere—were toppled.Footnote 14 Analysis of the attacks offers a much-needed counternarrative to the idealized vision of the interwar Czechoslovak democracy that appeared, especially in Anglo-American historiography after World War II.Footnote 15

The attacks reflected the myriad problems that the leaders of the multinational state—or, in Pieter Judson's term, “little empire”—ruled as a nation-state, faced in consolidating power.Footnote 16 In addition to the war in the short-lived Slovak Soviet Republic, these problems included the often-disputed annexation of towns and villages in Lower Austria, Galicia, and Germany, which had not previously been part of the Bohemian Lands and could not be claimed based on Bohemian state rights (České státní pravo/Staatsrecht). Rather, they were sought on economic and strategic grounds.Footnote 17 Particularly in the nationally mixed border regions, many residents—not only Germans but also the far smaller number of Hungarians in southern Slovakia—considered the Czechs an occupying power.

Back to the Legionnaires. Legionary political affiliations during the interwar years ranged widely, but much energy was concentrated on the far right; these men were extremely nationalist, anticommunist, and anti-German.Footnote 18 Some participated in fascist organizations between the wars. In particular, between the end of the Great War and the founding of a national organization, the Československá obec legionářská (Czechoslovak Legionary Community) in 1921, local Legionary groups, and individual Legionary actors had more space for independent action, including paramilitary violence, often as an adjunct to state power. Czechoslovakia's interwar history is blotted with examples of armed Legionary violence against Czechoslovakia's civilians, as the Legionnaires brought war home to the country's German, Jewish, and Hungarian citizens in the first years after the war.Footnote 19 It should be no surprise that Legionnaires sought to cleanse the built environment of symbols—and occasionally even historical actors—they considered inimical to their vision of the new Czechoslovak state.Footnote 20 Sometimes these efforts, like the extralegal removal of Joseph II statues, would put some of them in the government's crosshairs.Footnote 21

The Legionnaires often instigated the attacks on Joseph II statues, which although reflecting popular Czech anti-German/anti-Habsburg attitudes also demonstrated their impatience—as well as that of local Czechs—with the regional and national authorities who had heretofore primarily limited themselves to suggesting that statues be covered up or moved to museums. This, until a legal solution was found to the issue.

The pent-up rage of many Czechs, but especially the Legionnaires, over years of what they considered overt German nationalist deployment of Joseph II monuments—and, in the case of the Legionnaires, frankly, what they considered the Germans’ continued lack of respect for and loyalty to the new state—boiled over shortly after the second anniversary of Czechoslovak independence on 28 October 1920. Local Czech-German tension owed to Germans not observing the state holiday—indeed, they worked on that day. Local governments banned Czech celebrations, which the regional authorities often overturned; and in the case of Liberec/Reichenberg, Legionnaires stormed the city hall and threatened to kill the mayor if the Czech national white-red flag was not hung from the building.Footnote 22

Some local German officials placed their statues under guard, while others convinced residents to set aside plans to reerect local statues of the emperor in the aftermath of the Statue War in the interest of peace and order. In still other places, German residents spontaneously and, usually, peacefully restored their towns’ statues. The battles over many Joseph II statues that November resulted in their removal or covering up and, in one case, being pitched headlong into the public toilets. There were cases of violence in connection with attempted removal of Joseph II statues that resulted in destruction of property, numerous injuries, and several deaths.Footnote 23

I am analyzing three Statue War attacks: the first volleys in northern Bohemian Teplice/Teplitz on 28 October; an attack on the statue in far western Bohemian Cheb/Eger on 13 November, which reverberated in Prague and elsewhere; and one of the last and bloodiest clashes, in Aš/Asch, also in western Bohemia, on 18 November. These attacks exemplify Legionary warfare against German-speaking civilians of the Czechoslovak state. In majority German Teplice/Teplitz, national passions were already high on 28 October 1920, the second anniversary of Czechoslovak independence. They were fueled in part by allegations of mistreatment of local German-speaking recruits in the Czechoslovak military.Footnote 24 The participants in the patriotic celebrations included Czech National Socialists, members of the centrist Czech nationalist party, together with Legionnaires and Sokolists (Czech nationalist gymnasts, some of whom were also Czech National Socialists and/or Legionnaires), who marched through the street to the Market Square. One Legionnaire who spoke from the pedestal of the city's bronze Joseph II statue demanded the removal of the emperor—a modern work produced by sculptor Franz Metzner and a point of civic pride—within seventy-two hours. Rather than meet the demand to clear away the statue, district political officials simply boarded it up to buy time while the central government decided what to do with it. This is a ploy we have also seen used by local officials in the US.

The longer the statue of “their” emperor was encased, the angrier the city's overwhelmingly German residents became. In early November, an unknown person or persons removed the Teplice/Teplitz statue's covering. Fearing conflict, the Prague government sent in troops to maintain the peace. While the central government and German parliamentary deputies negotiated in Prague on 11 November, the workers charged with removing the statue laid down their tools. And despite a directive from the Ministry of the Interior to wait, the situation changed abruptly that same day when a delegation from the Pilsen-based 35th Legionary Regiment, led by a captain, arrived in town. The Legionnaires declared they would not leave until the statue had been removed. And the Legionnaires, without waiting for the government, set to work on its demolition. Without orders from the officers, several of them, armed with machine guns, blocked the entrance to the Market Square and removed the statue without damaging it. There were no reports of violence, and the statue was later transported to the garden of the city museum.Footnote 25

Just a few days after the removal of Teplice/Teplitz's Joseph II statue, there was another skirmish, this one in the small, overwhelmingly German-speaking town of Cheb/Eger. In this case, the response of the residents had repercussions across the Bohemian Lands. Since the war's end, local Czechs had sporadically attempted to vandalize Cheb/Eger's Joseph II statue, which also stood in the Market Square (Figure 7). These attacks had been foiled, but they had proven such a nuisance that the central authorities in Prague suggested that city council members move the statue to the local museum. This did not happen. What did happen was a kind of Czech-German guerilla warfare beginning on Saturday, 13 November, two days after the events in Teplice/Teplitz. Incidents included the damaging and removal of the Joseph II statue and its rapid replacement on its pedestal. The skirmishes started when a military band, composed of locally stationed soldiers, marched through Cheb/Eger disrupting German residents who were protesting government taxes on food in a time of inflation and ongoing food shortages, which dated back to the last years of the war.Footnote 26 The Germans hurled insults at the military band members, most of whom quickly and quietly retreated.Footnote 27 Back in their barracks, however, some of the soldiers resolved to retaliate against the civilians. Shortly after midnight on 13 November, some two hundred armed men crept stealthily into the empty square, where they overpowered the watchman and knocked Joseph II off his pedestal, breaking his right arm in the process. The intrepid watch still managed to sound the alarm, and within minutes the square was filled with the sound of church bells and the sight of the town's Germans coming to rescue “their” emperor. Once Germans took to the streets, unrest, including violence on both sides, continued through the night and into the following day. Incensed Germans forced their way into the Hotel Continental, which housed officers—some of whom, apparently fearing for their safety, fired shots through the doors of their rooms. By dawn, however, Joseph II—now one-armed and wearing a sash in German nationalist black-red-gold across his chest—had been restored to his pedestal.

Figure 7. Two-armed Joseph II looking over Eger/Cheb's Market Square sometime before World War I (postcard, property of the author).

Around midday on Sunday, 14 November, the mayor spoke from the base of the Joseph II statue, condemning the Legionnaires’ actions and demanding that German cities be freed of their Czech garrisons.Footnote 28 The Legionnaires were not yet finished with Cheb/Eger's Joseph II statue, however. They reportedly planned to attack it that night or the next. City authorities responded by having the statue welded to its pedestal.

It was adolescent demonstrators participating in Cheb/Eger's November violence, however, whose behavior caused the greatest outcry. They vandalized the town's recently opened Czech-language school and tore up pictures of Czechoslovak President Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk. Czechs angrily responded to this outrage by calling for a mass meeting in Prague two days hence to protest the German damage to the Czech school and the insult to the “President-Liberator's” image. What followed was several days of anti-German, antisemitic demonstrations in the capital, beginning 16 November. Incensed Czechs roamed the streets, attacking both people and property identified as “German” or “Jewish.” This was some of the worst nationalist rioting between the wars. As in the Statue Wars, the Legionnaires helped instigate some of the most violent behavior. In addition to demonstrating before the Parliament and calling for the removal of a German deputy, they seized and occupied the Neues Deutsche Theater (New German Theater) at the top of Wenceslas Square, which would continue to be a flash point for anti-German protests in the capital between the wars.Footnote 29

Meanwhile, in the wake of the riots in Cheb/Eger, the Legionnaires stationed at the Cheb air station sent a list of demands to the Defense Ministry on 18 November. These demands included the removal of the Joseph II statue, which the Legionnaires asserted the city's residents had replaced on its pedestal as a “provocation.” In addition to demanding that the perpetrators of the local Czech-language school's destruction be found and the city forced to pay for its repair, other demands reflected the Legionary mentality that they were occupying Cheb/Eger. These included that the Defense Ministry recognize that the military would “retaliate against” all threats and violence against the military, Czech women, and Czechs in general; a general house-to-house search for military weapons among the civilians; and the transfer of the garrison command to a “purely Czech and trustworthy officer.”Footnote 30

Also on 18 November came a resolution from the nationalist Legionnaires (Družina) who were holding a congress at the time the attacks on the Joseph II statues occurred. Their resolution, together with a congratulatory telegram from President Masaryk to the Legionnaires’ conference, reveals how much power the Legionnaires thought they could exercise and how much the government was willing to tolerate their behavior—because it really had no other choice. The Legionnaires’ announcement reminded Czechoslovak residents that the Legionnaires had “fought and bled for the freedom of the Fatherland.” And, while they—the Legionnaires—did not want to oppress the citizens of other nations, they “energetically demanded that the non-Czech nations be subject to the laws of the Czech Republic.” “We declare once and for all,” the resolution continued, that “we will not tolerate Germans and Magyars impugning the honor of the Legionnaires, as parliamentary representative [Hans, of the German National Socialist Workers’ Party] Knirsch did when he called the Legionnaires the Auffresser (devourers) of the Czechoslovak Republic.” If the government would not defend their honor, the missive continued, the Legionnaires would not concern themselves with parliamentary immunity. The Legionnaires condemned the attitude of the Germans in Cheb/Eger and Teplice/Teplitz and declared that they would retaliate “an eye for an eye; a tooth for a tooth.” They had run out of patience.Footnote 31 Masaryk's telegram to the Legionary congress dated 18 November noted how pleased he was with their pledge to remain true to the Czechoslovak Republic. What he wished above all from the Legionnaires, the telegram continued, was for those in active duty to build a valiant army. He hoped all Legionnaires would prove “exemplars of democratic endeavor and firmly support order and legitimacy,” at a time when they were clearly doing neither.Footnote 32

A few days after the events in Cheb/Eger during the night of 18 November, just as the Prague riots were dying down, some forty Legionnaires from the local garrison knocked down the bronze Joseph II statue that stood in front of the school in nearby Aš/Asch. The soldiers then returned to the garrison, where they fired random salvos into the air. Indeed, the sporadic sounds of gunfire could be heard throughout the night. As in Cheb/Eger, the pealing of bells awakened the town's German residents, who rushed to the defense of their emperor, whom they quickly returned to his pedestal. Described as excited and aggressive, local Germans—some armed, including two who were found to have military-grade weapons—gathered before the Lieutenancy Council and threw stones at the awning-covered windows of the office apartment. Gendarmes guarding the building called for reinforcements because the crowd was trying to force its way into the building, and they feared being disarmed. Two additional gendarmes and a sergeant with twelve enlisted men arrived on the scene. According to some reports, the Legionnaires fired into the crowd. The casualties included three dead and many hospitalized.Footnote 33 Local and national German-language newspapers describing the events referred to the Legionnaires in terms of soldiers “mutinying” and “open revolution and military dictatorship.”Footnote 34 It does appear that at least some of the Legionnaires were willing to act in what they considered the best interests of Czechoslovakia, even if the state did not necessarily agree. Indeed, Legionnaire plans to topple the Joseph II statue in Aš/Asch had apparently “long been known.” Prime Minister Jan Černý asserted that both the district political administration and the garrison command had taken all measures possible under the circumstances to dissuade these soldiers from their plan but had been unsuccessful.Footnote 35 A general was dispatched from Prague to calm the situation.Footnote 36

The Legionnaires’ removal of the statues reverberated throughout the Bohemian Lands. From the Germans came loud complaints about the central government's failure to stop what they considered lawless Czech behavior. On the Czech side, there were popular anti-German protests and attacks on other statues of Joseph II. Czech reactions to the attacks on the statues were, however, complicated. Czech intellectuals had long debated the effects of the Josephinian reforms. While recognizing the emperor's positive contributions in some areas, Czechs stressed the emotional and psychological significance that German nationalists had invested in them. Still, there appears to have been a Czech political consensus that the Habsburg emperor did not belong in the public spaces of independent Czechoslovakia. Prime Minister Černý, to howls of derision from German parliamentarians, initially defended the Czech Legionnaires’ attack on the statue in Teplice/Teplitz because the statue was an “unfortunate reminder of the former Austrian state.”Footnote 37 Many Czech politicians advocated the removal of the statues under government auspices. In late November 1920, they supported a parliamentary motion to remove all Habsburg monuments from public places. The issue of the Joseph II statues’ future, which had in some cases been taken to court, was settled only in the mid-1920s. The basis for these legal decisions was Paragraph 23 of the Law for the Defense of the Republic from 1923, which called for the removal from public view of statues, inscriptions, and memorials of antistate character or of members of the Habsburg or the Hohenzollern dynasties. Under the auspices of this law, the state would remove virtually all the Joseph II statues that hadn't fallen victim to Czech Legionnaires in the Statue War. At least one obelisk above a village outside Teplice/Teplitz remained, its inscription intact (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Joseph II obelisk on a hill above Kostomlaty pod Milešovkou/Kostenblatt, near Teplice/Teplitz.

The removal of the Joseph II statues failed to mollify the Legionnaires. Wherever there was German-Czech tension in the early years of the republic, the presence of Legionnaires often further complicated already difficult national-political situations—or any situation really—that they believed constituted a threat to their vision of the integral Czechoslovak nation-state. Thus, Legionnaires joined gendarmes guarding against destruction by, and battling with, workers during the country's short-lived general strike of December 1920. Some seven months after the Statue War, in June 1921, Legionnaire violence in the predominantly German northern Bohemian city of Ústí nad Labem/Aussig an der Elbe led to casualties and death.Footnote 38 There are numerous examples in the early postwar years of Legionnaires seeking to settle disputes with a knife or a gun.Footnote 39 Moreover, Czech Fascists organized the other great anti-German riots in interwar Prague, protesting German-language films in September 1930. It should be no surprise that one of this party's founders was Legionnaire and Zborov veteran Radola Gajda.Footnote 40 Much like veterans elsewhere in Central Europe, some Czech Legionnaires, who certainly accepted an independent Czechoslovak state, rejected some aspects of the new democratic order and refused to enter civilian life. They insisted on violence as their main means of defense of their republic against both the real or presumed danger of the Bolshevik Revolution and of non-Czech/-oslovak, above all German-speaking, cocitizens.

As Robert Gerwarth and John Horne have pointed out, the replacement of empires by self-styled nation-states after 1918 motivated paramilitary squads to neutralize what they perceived to be threats to their nation posed by local linguistic minorities. Over time, paramilitary ideology shifted to include leftists, owing to the looming threat of communism, along with ethnic minorities as interchangeable enemies to their nation. Like other soldiers formerly in the Habsburg military, the particular practices Legionnaires employed in their battles against German civilians, frequently large in number but usually unarmed or less well-armed, often reflected their Habsburg military training as well as their experience with total war on the eastern front.

At the same time that they were removing statues of Joseph II, Czechs were constructing what they understood to be more appropriate democratic monuments, including of Masaryk and the Legionnaires, occasionally on the very pedestals where Joseph II had stood. Indeed, ČKD Blansko, successor to Fürstlich Salm'sche Eisenwerke, produced some of the Legionnaire statues.Footnote 41 A number of the Joseph II statues were hauled off to museums, where they remained between the world wars. In Ústí nad Labem/Aussig an der Elbe, the local Joseph II statue survived the ire of the Legionnaires but not that of the Nazi occupiers after 1938, who had it removed and, together with a statue of Masaryk, taken off to be melted down for the war effort.

What was the fate of the Teplice/Teplitz Joseph II statue, whose removal had started the whole Statue War? As we know, the Legionnaires removed it from its pedestal before the city hall to the courtyard of the museum, but it is said to have gone missing after World War II. All that remains of the five-meter-tall emperor today is the statue's base, which was repurposed after 1945 as a memorial to Czech soldiers and patriots. Containing soil from Zborov, Dukla Pass, Dunkerque, Ruzyně, Terezín, and Pankrác, it recalls the battles, concentration camps, and political prisons where Czechs died for their country, memorializing a variety of important military and political sites in twentieth-century Czechoslovak history. A second inscription, “To the Victims of Communism” has been added to the pedestal-monument since 1989.

Since the fall of communism in 1989, scores of Joseph II statues have begun reappearing in the Czechoslovak and, after 1992, Czech landscape, even as numerous statues and monuments from the communist era soon had their inscriptions removed or were taken away altogether (Figure 9).Footnote 42 The new Czech-language inscriptions on the Joseph II statues are primarily variations on “Enlightened ruler and reformer,” which Joseph II was.Footnote 43 In the twenty-first century, Joseph II has even occasionally been the focus of popular festivities. At least one statue has been repurposed as a kind of brightly painted garden gnome in front of someone's cottage, while yet another stood during the 1990s—and perhaps still stands—near a roadside restaurant in northern Bohemia.

Figure 9. Joseph II Monument in Josefov/Josefstadt, today part of Jaroměř/Jermer (left, 2016); restored Joseph II Bust Pedestal in Brno/Brünn (center, mid-1990s); Joseph II Monument in Trutnov/Trautenau (right, 2016).

The Czechs’ new—more benign, less nationalist—interpretations of the Joseph II statues, however, reveal the limitations of parallels between them and the US Confederate statues. Although some Confederate monuments may yet someday occupy well-curated spaces in museums, as part of the US historic past, it seems unlikely that they will again occupy public space because their presence in public is unlikely to lose the ability to excite and/or offend many passersby. Emperor Joseph II has become a neutral figure. The likes of General Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis have not.

In the end, what do we learn from rethinking the Legionnaires’ removal of Joseph II statues, locating them in the context of the postwar popular and paramilitary violence that marked the period from 1918 to 1923? What are the wider implications for modern Czechoslovak/Czech history that emerge from this intellectual exercise? The answer is that it helps us see how violence helped to midwife democracy into being after the Great War. We have established that some Legionnaires had posed a danger to the state in its early years as they challenged its political leaders, including Masaryk, over visions of the country's future. A few Legionnaires, including Zborov veteran Radola Gajda, posed that danger as late as 1930. Yet, the Legionnaires were consistently fěted as a constituent part of Czechoslovak democracy, thanks to interwar Czech democratic mythmaking and the growing contrast between Czechoslovakia and the other states of post-Habsburg Central Europe as they became increasingly authoritarian. The Legionnaires’ association with democratic greatness was perhaps heightened by the Nazi occupation and communist authoritarianism. During World War II, the Nazis targeted Legionnaires, sending many to concentration camps. They also removed the remains of the unknown soldier in Prague, a Zborov veteran, and tossed them into the Vltava River. The Nazis damaged and then destroyed the unknown soldier's tomb. It is no surprise that the post–World War II commemoration of the victorious Czechoslovak Legionnaires at Zborov was a time to condemn pan-Germanism. Following the communist coup of February 1948, Legionary participation in the “counter-revolutionary struggle against the Red Army” during the summer of 1918 would be little mentioned in Czechoslovak histories; indeed, the Legionnaires all but disappeared from popular discussion.

Since 1989, the Legionnaires have reemerged in Czech popular memory as heroic warriors whose national exploits played an important role in founding democratic Czechoslovakia. Until the last decade or so, neither their violent behavior in the revolutionary Russian east, where they seized the Trans-Siberian railroad and occupied large swathes of Siberia, nor their violence against residents of Slovakia in June 1919 found much mention.Footnote 44 It seems to have been easier since the Velvet Revolution and the fall of communism in 1989 to rehabilitate Habsburg emperor Joseph II than it is to bring about a wholesale popular reconsideration of the Legionnaires, who remain a cherished part of popular national foundation myths.

Here is where we can return to the issue of Confederate soldiers in the US: Despite a huge historiography that contradicts it, the myth of the Lost Cause of the Confederacy remains popular with a certain segment of the American population that includes white supremacists and other nationalists. Some of these people offered a strong, sometimes armed defense of Confederate monuments against spirited attacks in a time of cultural, economic, political, and social unrest in the United States. The reaction that the Joseph II and the Confederate statues elicited in times of unrest were similar. The Proud Boys, Neo-Confederates, and others trying to prevent the Confederate monuments’ removal were acting as extralegally as the Legionnaires, who were trying to do the opposite: remove the Joseph II statues. Both groups, stretching across history, shared the belief that their behavior was patriotic and justified. This behavior took place in two countries—Czechoslovakia and the United States—whose foundation myths include the idea of being exceptional democracies. They are not. It is vital that historians carefully integrate these episodes into their larger historical narratives.

Nancy M. Wingfield is a cultural and gender historian of modern Habsburg Central Europe. The former editor of Nationalities Papers, her numerous publications include the award-wining monograph The World of Prostitution in Late Imperial Austria (Oxford University Press, 2017) and Flag Wars and Stone Saints: How the Bohemian Lands Became Czech (Harvard University Press, 2007). She has also published articles in the Austrian History Yearbook, Central European History, and Journal of the History of Sexuality. She has been the recipient of Fulbright, American Council of Learned Societies, and Woodrow Wilson Center fellowships.