1. Introduction

1.1 Essential health benefits and state flexibility

A core component of the Affordable Care Act's (ACA) coverage expansion efforts targeted improving the quality of health insurance coverage. One of the primary mechanisms for improved quality of insurance was the creation of Essential Health Benefits (EHB). The EHBs are minimum insurance benefits encompassing 10 categories of care, which the ACA required all non-grandfathered individual and small-group market plans, and all plans sold on the health care marketplaces, to cover (Willison and Singer Reference Willison and Singer2017). EHBs have been a prime target in the Congressional Republicans efforts to repeal and replace the ACA. Republicans have argued that EHBs increase the costs of insurance and force benefits on individuals who do not want the coverage and have led to a spike in premiums for these insurance plans. However, the future viability of EHBs is as much contingent on continued Republican efforts to undermine their impact, as well as federalism and implementation decisions made by the Obama administration.

We evaluate the current state of how EHBs have been implemented through a comparative analysis of state benchmark plans and coverage variation for mental health and substance abuse disorders in the individual and small group markets. Coverage for behavioral health services are of particular concern because of the historic inequities in behavioral health coverage compared to other types of medical care insurance coverage (Barry, Reference Barry2006). Understanding present EHB standards establishes an important benchmark to evaluate future health insurance-plan benefit coverage offerings. Additionally, we compare EHB coverage benefits for mental health and substance use disorder with medical practice guidelines, as a means to measure the quality of plan benefit structure. These findings are particularly timely because of persistent efforts by the Trump administration and Congressional Republicans to reduce the federal government's role in health insurance oversight and the continued political and policy tension over the quality of insurance coverage available under the ACA.

The results of our evaluation of the quality and quantity of EHB coverage for mental health and substance use disorders highlight the double-edged sword of federalism and implementation of health reform that relied on states to ensure their participation. There is significant variation in mental health and substance use disorder coverage across states' benchmark plans. This variation exists in how plans define treatment, coverage limits, and exclusions. Yet, variation across states is not inherently bad. The Obama administration had to navigate a difficult political calculation in the implementation of the law. While EHBs were national in scope, the federal government relied heavily on state assistance and participation to cultivate acceptance of the law. State participation in the implementation of reform allows for greater regulatory flexibility and lets states experiment and innovate, to account for and address different health system structures, health care needs and financial constraints on policymaking. Flexibility allows states to better balance all these priorities in creating benefit plan standards that fits their particular populations and policy preferences.

Yet, this flexibility comes with its own drawbacks. Supporters of health reform viewed EHBs, especially the inclusion of mental health and substance use disorders, as a major reform and victory for individuals who needed those services. Federal parity laws have brought mental health and substance use disorder out of the shadow of other medical conditions and inclusion as an EHB would bring increase coverage in insurance. Yet, relying on a federated approach to EHBs risks promoting inequity. This inequity in coverage is particularly troubling when it comes as the expense of practice standards (Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, 2001). Here, practice standards refer to guidelines issued by professional medical societies including the American Psychiatric Association, and guidelines issued by the National Institutes of Health as consensus from systematic reviews of peer-reviewed medical guidelines and research (Powers et al., Reference Powers, Nishimi and Kizer2005; Institute of Medicine, 2006; Gelenberg et al., Reference Gelenberg, Freeman, Markowitz, Rosenbaum, Thase, Trivedi and Van Rhoads2010). We recognize that, in using this standard and in evaluating variation in EHB insurance plans, we are conforming to current frameworks of insurance coverage that inherently regulate access to medical services sometimes a priori of clinical judgment.

Our research finds notable divergence between accepted medical practice standards and the reviewed essential benefit benchmark plans standards. Coverage that does not reflect minimum standards of care threatens to harm individuals and populations and may constrain providers' ability to provide appropriate quality care. These findings question whether incongruence between formalized professional practice standards and plan benefits is acceptable, while raising questions about the efficacy of a federated benchmark-plan approach. This is even more salient as political efforts to reduce health care policy regulations and decrease federal standards in favor of federated approaches to health insurance benefit design and oversight.

1.2 A brief history of state authority and mental health benefit exclusion

1.2.1 Mental health coverage

Evaluating coverage amounts across benchmark plans is particularly important for mental health and substance use disorder care. In the United States, mental health care, including counseling, medications and treatment for addiction disorders, grapples with a long history of insufficient health insurance coverage, or being entirely excluded from insurance plan coverage. These coverage gaps do not align with disease prevalence. One in five adults, in the United States, suffers from a mental health or substance use disorder. Mental disorders account for four of the 10 leading causes of disability (U.S. Census Bureau, 2013). Mental health is also one disease state in which people are most often underinsured (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration, 2013b). The combined severity, prevalence and insufficient health insurance coverage gave impetus for including mental health and substance use disorder services as an EHB (Health Policy Brief: Essential Health Benefits, 2013; Cauchi, Reference Cauchi2015).

1.2.2 Federalism and health insurance regulation

EHB implementation characterizes the regulatory division between state and federal government over private health insurance management and oversight. Traditionally, states have held a major role in regulating private health insurance in the United States (Klein, Reference Klein, Grace and Klein2009: 13–51). Yet in 1974, the federal government's role expanded significantly, through the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA). Large, self-insured employers were now subject to federal ERISA oversight as opposed to state-level regulation. With the EHBs, the ACA made the first ever attempt to federally standardize and regulate insurance coverage for multiple categories of medical services and across different types of health insurance (Haeder, Reference Haeder2014: 285–286). The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 (MHPAEA) extended the Mental Health Parity Act from 1996, which required health plans to not charge more for behavioral health services than general medical services but did not address disparities in service coverage between mental health and general medical care. MHPAEA of 2008 attempted to standardize access and affordability between mental health and medical services (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration, 2013a). However, the nature of this shared regulatory environment between states and the federal government produced variable benefit packages across the states (Bagley and Levey, Reference Bagley and Levy2014: 446–447). Table 1 outlines the history of these state and federal regulations. The EHBs offered an opportunity to standardize the quality of these packages across states.

Table 1. Timeline and progression of major U.S. mental health legislation and regulations for private insurers

a Does not apply to self-insured small private employers that have 50 or fewer employees and self-insured non-Federal governmental plans that have 50 or fewer employees. Large, self-funded non-Federal governmental employers may opt-out of MHPAEA requirements. MHPAEA does not require large group health plans or health insurance issuers to cover MH/SUD benefits.

b MPHEA was amended by the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010 (part of the ACA) to also apply to individual health insurance coverage.

c The ACA's EHBs apply to any private large group plan offered on the Health care Exchanges. The ACA's EHB components do not apply to private large-group plans off the health care exchanges.

Many states have their own state mental health parity laws and regulations, although many are not comprehensive, and exclude self-insured plans or small firms (Buchmueller et al., Reference Buchmueller, Cooper, Jacobson and Zuvekas2007). Under the federal parity legislation, large, self-funded non-federal governmental employers may elect to opt out of parity requirements (The Center for Consumer Information & Insurance Oversight, 2016). Large group health plans not sold on the Health care Exchanges are also not required by any federal authority to cover specific services, even under the ACA (The Center for Consumer Information & Insurance Oversight, 2016). Poor coverage is less of an issue for large group plans, which historically provide more comprehensive benefits than individual and small group plans. Individual and small group plans, prior to the ACA, were not required by any federal authority – including parity law – to cover any specific services, often leaving these plans with inadequate benefits, and disadvantaging enrollees (Schoen and Doty, Reference Schoen and Doty2011).

This variation across states as well as the limited scope of coverage regulations in the individual and small group markets prompted the Obama Administration to create the 10 EHBs (Giovannelli et al., Reference Giovannelli, Lucia and Corlette2014). Section 1302 of the ACA originally tasked the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) with developing the EHBs (Haeder, Reference Haeder2014). Yet in 2011, HHS unexpectedly delegated EHB plan development to the states, allowing states to design their own benchmark plans for minimum insurance coverage, within some broad parameters. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) gave states four options to generate a benchmark plan: (1) the largest plan by enrollment in any of the three largest products by enrollment in the state's small group market; (2) any of the largest three state employee health benefit plan options by consumer enrollment; (3) any of the largest three national Federal Employees Health Benefits Program plan options by enrollment or (4) the HMO plan with the largest insured commercial non-Medicaid enrollment in the state (Haeder, Reference Haeder2014; The Center for Consumer Information and Insurance Oversight, 2015a, 2015b, 285).

Twenty-five states and Washington D.C. selected their benchmark plan from one of those options. Of those states, 19 states chose a benchmark plan from the small group plan, four states selected a benchmark plan from their largest HMO plan and three selected a benchmark plan from their state employee plan (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2014). Of the remaining states, HHS selected the largest plan in the state's small group market as the default benchmark plan (The Center for Consumer Information & Insurance Oversight, 2015a, 2015b).

When HHS announced the rules to design EHBs, they assumed that there would be some variation in benefits and coverage among some markets and some plans, but that overall, there would be ‘no systematic difference noted in the breadth of services among these markets’ (Center for Consumer Information and Insurance Oversight, 2011). This and other research demonstrates that this is not the case. While in an early stage, previous evaluations of EHB coverage for pediatric care, nutrition and weight loss, autism treatment and chiropractic care have found wide variation in the coverage and benefits plan features across the states (Grace et al., Reference Grace, Noonan, Cheng, Miller, Verga and Rubin2014: 2136–2143; Weiner and Colameco, Reference Weiner and Colameco2014).

With enactment of the ACA, all plans sold on the health care exchanges or the individual or small group market had to comply with federal parity law established by MPHAEA. Our analysis focuses on coverage in the 2012–16 plans, with an additional review of the 2017 plans. CMS did not require EHB plans to comply with parity until 2017 (The Center for Consumer Information and Insurance Oversight, 2015b). However, all states were encouraged to comply early, and all states identified and listed their EHB plan for the purposes of creating state Insurance Exchanges, by 2014 (Bagley and Levey, Reference Bagley and Levy2014). Therefore, this analysis of the pre-parity requirements serves as an important reference point for measures of individual and small group market behavioral health coverage. Further, comparisons of state plans from 2012 to 2016 with 2017 reflect similar levels of coverage stringency, variation and potential inadequacy (The National Center on Addiction and Substance, 2016). This analysis does not make any claims to evaluate state plans' compliance with federal parity law. Compliance with parity is mandatory, but implementation may be difficult, and is beyond the scope of this analysis. Rather, this paper is concerned with understanding how states varied in the design of their insurance plans under the ACA.

2. Methods

To understand the degree of variation across state benchmark plans and their compliance with medical practice coverage guidelines, we collected coverage information for mental health and substance use disorder treatment from the EHB benchmark plans in every state, the District of Columbia, and all six U.S. territories. State benchmark plans and EHB coverage data are publicly available from CMS (The Center for Consumer Information and Insurance Oversight, 2015b). The analysis includes benchmark plans and all supplemental coverage plans from 2012 to 2016, state required benefits, and all 2017 benchmark plans, any supplemental coverage plans, and updates to coverage from 2012 to 2016 for all U.S. states and territories. In total, we evaluated 112 benchmark plan documents across the states, creating a unique dataset of mental health and substance use disorder coverage outlined in state benchmark plans in effect from 2012 to 2016.

We then conducted analyses comparing minimum required coverage between geographic states. To gage the efficacy of each state's minimum coverage requirements in their benchmark plan, we also compared requirements to the most recently available medical practice guidelines for appropriate and effective inpatient and outpatient treatment for mental health and substance use disorder care. For the remainder of the paper, the term ‘state(s)’ will be used to refer collectively to the states, District of Columbia and U.S. territories.

Following the standards established by CMS, there are four categories of care for mental health and substance use disorder coverage: (1) mental health inpatient, (2) mental health outpatient, (3) substance use disorder inpatient and (4) substance use disorder outpatient. These four categories are the primary categories of care used in the analysis. We developed a new coding scheme to classify nine comparison variables [Residential Treatment/Custodial, Services Not Medically Necessary, Methadone Maintenance, Court Ordered Treatment Referrals, Missed Appointments, Telephone Therapy, Other (e.g. partial programs), Ending Treatment Against Medical Advice, Treatment of Codependency] between each of the four categories of care for each state's benchmark plan. These categories were created by two coders, coding independently and then together for interrater-reliability. Of particular note were variables cataloging variation in the quantitative limits and exclusions of care within each state's benchmark plan.

In addition to the variables for state benefit plans, we retrieved professional medical practice guidelines for each of the four categories of care. To collect medical practice guidelines, we utilized a search strategy to identify and evaluate the relevant literature and professional societies issuing mental health and substance use disorder practice guidelines. To find the most recent medical practice guidelines, we used PubMED to identify the literature addressing practice standards for mental health and substance use disorder care. Combinations of MeSH (Medical subject headings) terms used in the literature search included mood disorders, mental disorders, public health, patient readmission, aftercare and substance-related disorders/therapy. Keywords searched (in Google and PubMED) included practice standards, efficacy, best-practices and effective care. We applied combinations of keywords and MeSH terms to the PubMED search to collect all extant literature. The use of Scopus citation tracking helped to further identify relevant literature. We determined which standards were primary standards by reviewing standards drafted by professional medical organizations, and or accredited medical bodies.

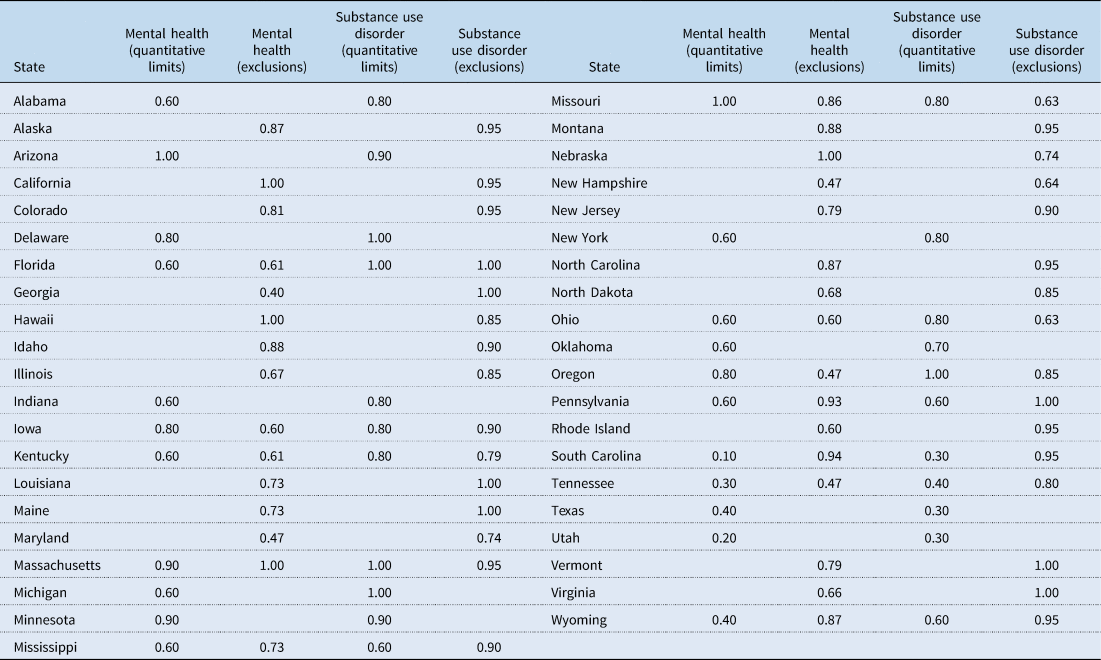

To further illustrate the variation in benefit plans across states, we created a scale to represent the generosity or stringency of mental health and substance use disorder coverage across states. The measure of state generosity is directly informed by the number of Quantitative Limits and degrees of Exclusions on coverage contained in benchmark plans, which are the means by which plans limited coverage. We constructed the generosity scale by combining CMS’ measures of coverage (Quantitative Limits and Exclusions) and professional medical practice guideline recommendations for adequate health insurance coverage. Not all states included a limit/exclusion in each care-category. Each generosity score is set between 0 and 1, with a higher score representing greater benefit coverage generosity. States that did not restrict coverage for a category of care received a score of 1 for generosity in that category of care. Each item comprising the generosity score was weighted equally and treated as a binary entity, scored as present or not for each item. A detailed discussion of the generosity scale construction is given in the next sections.

2.1 Quantitative limits generosity score

We used the following items to construct the generosity score for Quantitative Limits for inpatient and outpatient mental health. Five items comprise the score:

(1) No limit on services

(2) Any limit complies with established practice guidelines

(3) Limit does not apply to two or more categories of care

(4) Limit provides an exception for severe mental illness

(5) Does not provide a stringent limit (defined as less than half of the recommended days or visits for care)

Items (1) and (2) are the baseline measures of generosity – whether or not a state's mental health services coverage complies with recommended practice guidelines, and whether or not a state limited the number of services enrollees can receive annually. Item (3) refers to placing a quantitative limit on coverage to two categories of care, a common practice among state benchmark plans. Combining limits act as a way for plans to limit access to care by constraining coverage. For example, South Carolina limited inpatient care – for mental health and substance use disorder services combined – to 7 days a year, total. The fourth item is related to limits on services that do not distinguish for patients with severe mental illness, who may have greater care needs. By not allowing coverage modifications based on disease severity, these plans' benefit coverage becomes less generous. The last item captures the degree to which a state is in violation of recommended coverage, or how flagrantly a state is in violation of practice guidelines.

The generosity scale for Quantitative Limits on substance use disorder services uses the same first four items as the prior generosity scale. This scale also includes an item used only in benchmark plans related to limiting coverage of substance use services. Some states that place an annual quantitative limit on substance use disorder coverage include an upper limit, a lifetime cap on service coverage (e.g. a type of care is limited to a certain number of times a patient may receive that type of care, over their lifetime). Texas, for instance, limits inpatient substance use disorder service coverage to three series of treatments per lifetime.

To calculate each state's generosity score, a state received credit for each item their benchmark plan observes. We then calculated an overall generosity score from the proportion of items a state plan meets. E.g., if a state meets two out of five items for Quantitative Limits, it would receive a generosity score of 0.4.

2.2 Exclusions (non-quantitative limits) generosity scale

The second way by which plans limited coverage was exclusions (non-quantitative limits) that they place on the types of services that are not covered by insurance. These exclusions were grouped together into larger categories that shared similarities. The most common type of exclusions was for Residential Treatment Centers (RTCs), Learning Disorders Testing/Therapy and Counseling. In total there were eight categories of care. The generosity score for exclusions was derived from the number of categories of care that were excluded for mental health and substance use disorders, ranging from zero to one (similar to the generosity score described above). If a state did not exclude any categories of care, they received a score of 1, indicating their benchmark plans were the most generous. For example, the benchmark plan in Ohio excludes three of the eight care categories, leaving five categories as unrestricted. The generosity score is based on the percentage of categories that are not excluded, so Ohio receives a generosity score of 0.625 (5/8).

3. Results

3.1 Overview of results

Overall, there are three themes that emerge from our analysis of insurance benefit design for mental health and substance use disorders in benchmark plans. First, benchmark plans for EHBs are marked more by what is not covered, as opposed to what is covered. The use of exclusions and quantitative limits were commonly used in mental health and substance use disorder coverage. When divided into four different settings for care (inpatient and outpatient care for mental health and substance use disorder), coverage limits were accompanied by substantial variation across the states to the extent they were used (see Table 2). For example, for inpatient mental health coverage, South Carolina's benchmark plan is limited to only 7 days per year, the strictest limits in the nation. Conversely, Oregon's benchmark plans are the most generous, allowing for up to 45 days per of inpatient coverage per year.

Table 2. Range of limitations on care coverage by category of care

Second, state autonomy in the selection of EHB plans has led to divergence in the benefit design of mental health and substance use disorders and professional medical practice guidelines. This comparison is useful to judge the quality of coverage made available under the ACA, as improving plan quality was a goal of EHBs and provide a base-level indicator of the appropriateness of the coverage outlined in a state's benchmark plan. Similar to the use of exclusions and quantitative limits, the results of plan adherence to clinical guidelines was subject to a geographic lottery, where an individual lives is connected to the quality of the coverage in benchmark plans.

Overall, 35% of the states that included Quantitative Limits, limited care to the degree that the coverage departed from medical practice guideline standards for adequate behavioral health benefit coverage. Of states with coverage exclusions, 17 states placed exclusions that do not adhere to professional coverage standards. Divergence from medical practice guidelines was evident for inpatient substance use disorders as well. For example, guidelines recommend 28-day treatment programs, compared to programs with shorter duration (Barnett and Swindle Reference Barnett and Swindle1997; Olmstead and Sindelar, Reference Olmstead and Sindelar2004), resulting in lower readmission-risk is associated with fewer early discharges, a longer intended treatment duration, more patient participation in aftercare, and treating patients on a compulsory basis (Peterson et al., Reference Peterson, Swindle, Phibbs, Recine and Moos1994). For patients with co-occurring substance use and mental health disorders, longer treatment durations have also been found to be the most effective at reducing readmissions (Brunette et al., Reference Brunette, Drake, Woods and Hartnett2001). Yet, half of the states placed Quantitative Limits on inpatient substance use disorder care. Thirty-seven percent of states with Quantitative Limits on inpatient substance use disorder care covered 21 days or less. Similar divergence between coverage and medical guidelines was found for outpatient mental health benefits for mood and anxiety disorders (Agency for Health care Research and Quality, 1993; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Delmer and Kessler2002: 92–98; Alexandre, Martins, and Richard, Reference Alexandre, Martins and Richard2009; Gelenberg et al., Reference Gelenberg, Freeman, Markowitz, Rosenbaum, Thase, Trivedi and Van Rhoads2010: 44).

Exclusions exhibited the same type of divergence between guidelines and benefit coverage (see Table 3). This divergence is most evident in the use of RTCs. The State Associations of Addictive Services lists RTCs as one of the most important means of effectively treating substance use disorders (State Associations of Addiction Services, 2013: 2), which is supported by substantial evidence across the literature (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2002: 5; O'Brien and Perfas, Reference O'Brien, Perfas, Lowinson, Ruiz, Millman and Langrod2004; Institute of Medicine, 2006; Reif et al., Reference Reif, George, Braude, Doughtery, Daniels and Ghose2014). Yet, RTCs are the most frequently excluded benefit across all state benchmark plans and all categories of care.

Table 3. Frequencies of exclusions

The third theme which emerged from the results of the analysis is a comparison of exclusions and quantitative limits between mental health and substance use disorder. To make this comparison we analyzed the generosity scores for both inpatient and outpatient coverage and for exclusions and quantitative limits. Across all care settings, state benchmark plans were more generous for substance use disorder treatment, with an average generosity score of 0.72, compared to 0.62 for mental health coverage in both inpatient and outpatient coverage. Similarly, benefit coverage is more generous for exclusions, meaning states placed exclusions less often than other coverage restrictions. The average generosity score for mental health exclusions was 0.75, while substance use disorder benefit coverage had an average of 0.88. These results were supported by results from Pearson correlation coefficients (Table 4).

Table 4. Average state generosity scores for quantitative limits and exclusions

However, these results do not necessarily indicate that substance use disorder benefits are necessarily generous overall. One mechanism that limits the generosity of these benchmark plans is combining quantitative limits on coverage for mental health and substance use disorder care. For example, Utah capped mental health and substance use disorder inpatient coverage at 8 days a year for both services, placing severe constraints on access to care for an EHB (see Table 2). While substance use disorder had consistently more generous coverage, variation was constant across the states, especially for individuals insured on the individual and small group markets, health insurance coverage of behavioral health services is largely determined by the geographic lottery.

In 2017, 19 states submitted revised plans to the federal government. There was some sign toward improved benefits coverage for mental health and substance use disorders in the revised plans. While most states had quantitative limits in their benchmark plans, all but six states removed those limits in their 2017 plans. Yet, of the six states that retained their quantitative limit, two, Michigan and South Dakota, actually increased the stringency of their mental health and substance use disorder limits and reduced access to services. Exclusions for mental health and substance use disorders remained comparable to previous plans.

4. Discussion

Historically, policymakers have given less attention to mental health policy than traditional medical care policy. Mental health coverage improved over the past decade due to state and federal legislation addressing parity and equity, and determining behavioral health to be an ‘essential’ health benefit. Yet in the age of the ACA's EHBs, mental health coverage remains subject to geographic lottery – where one lives determines the richness and costs of one's benefits. Variation is a double-edge sword. CMS itself stated that, ‘this approach best strikes the balance between comprehensiveness, affordability, and state flexibility’ (The Center for Consumer Information & Insurance Oversight, 2015a, 2015b). The wide-variation and questionable quality that this research found in the 2012–16 plans advises further deliberation and consideration of the federated division of regulatory power in design and implementation for health insurance coverage standards. The implications of federated divisions of power, for insurance coverage standards design and oversight, grow increasingly important in light of political efforts to further devolve insurance-policy decision-making to state governments.

An important implication of these findings is that determining state EHB plans is a regulatory, rather than a legislative task. While policymakers can and are currently taking actions to decentralize health care policy and decision-making, state-level regulators are responsible for setting – and expanding or restricting – state benefit plans. Tensions between federal oversight, and state interests such as private insurance markets and marketplaces, exert pressure on state regulatory choices. Yet, the regulatory decisions being made at the states is not divorced from pressure. Increased awareness of the divergence of benchmark plans and medical guidelines, as well as increased federal oversight into the management of benchmark plans can assist in improving the quality of coverage available for mental health and substance use disorder.

This study is limited in three aspects. First, the primary focus of this analysis is restricted to diagnostic classifications of Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders. Services for mental health and substance use disorders have a history of under-provision and underreporting, and these findings could be an artifact of earlier historical trends in access for these services. Second, this analysis is descriptive in nature and does not address the underlying causes of variation among the states. There are many reasons why states may have more or less generous EHB plans, including partisanship, private insurance stakeholder networks, medical costs and the history of state-level investment in behavioral health. Research focused on how states constructed their benchmark plans should be the focus of future work in this field. Additionally, this paper does not attempt to measure enforcement of the EHBs by state. The variation described here may in fact be wider depending on the nature of implementation and enforcement by states. This may be another important area of future research.

Efforts to reduce the federal government's role in health insurance oversight persist (Oberlander, Reference Oberlander2017). Further, despite failed efforts to repeal and replace the ACA, much new Republican effort targets expanding state flexibility in health insurance regulation. An existing component of the ACA – State Innovation Waivers – would allow states to opt-out of key components of Obamacare, so long as health coverage is not endangered, and the federal deficit is not increased (Levitis, Reference Levitis2017; Singer, Reference Singer2017). Yet, the Trump administration has taken the regulatory teeth out of those restrictions, allowing less robust insurance products to count as coverage. This proposed guidance ‘allow states to provide consumers with plan options that best meet their needs’ (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2018), but it can also lead to reduced coverage for mental health and substance use disorders. These efforts can ultimately lead to increased variation in minimum coverage requirements across the states.

EHB plans established under the Obama Administration's vary considerably from state-to-state, and many include strict-coverage limits that question the efficacy of coverage provided for accessing essential medical services. The persistent efforts to undermine the ACA and EHB regulations are even more concerning given this existing variation in coverage standards. The prevalence of behavioral health disorders and the history of inadequate insurance coverage for behavioral health care necessitate appropriate and effective health insurance coverage standards. The EHBs future rests on state and regulatory action.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744133119000306.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Nicholas Bagley, Jessica Berg, Peter Jacobson and Kirsten Herold for their helpful comments on the manuscript.