Introduction

To stop the Iron Horde, we must overcome prejudice and work together, if only for this purpose. Horde, Alliance, past, present … all meaningless in the face of this enemy. We will retake Shattrath together … or die trying.

Archmage Khadgar, The Battle for Shattrath, Warlords of Draenor.

The ‘cottage industry’ of security studies was once specialised in pinning down new definitions of security beyond its traditional military focus.Footnote 1 It has since shifted its production to supply abundant criticism of arguably the most successful proposal to ‘widen’ the concept of security: securitisation theory. Coined by Ole Wæver within the broader Copenhagen School,Footnote 2 securitisation considers the fundamental essence of security to be a speech act that raises an issue above the normal workings of politics, by positing an existential threat to a referent object that must be defended through exceptional measures. Among many other aspects of the theory, this notion of exceptionality has been widely contested. As it ‘reflects the traditionalist element in the wide/narrow debate’,Footnote 3 it has been accused by the more critical scholars of maintaining an essentialised if not statist view of security, informed by Carl Schmitt's infamous political theory of the sovereign exceptionFootnote 4 and predicated on liberal democratic ‘normal politics’.Footnote 5

Many securitisation scholars have thus moved away from this exceptional view, instead stressing an alternative logic of risk, how practitioners perceive their own actions, or mundane processes forming ‘little security nothings’.Footnote 6 Nevertheless, without reference to exceptional measures or existential threats, much of the originality of the Copenhagen School's theory risks being lost, as securitisation could be reduced to a mere ‘shorthand’ for the ‘social construction of security’.Footnote 7 Following Juha Vuori's suggestion to ‘investigate security speech in as many contexts as possible’,Footnote 8 this article explores the force of securitisation theory's ‘logic of exception’Footnote 9 in an unusual and demanding context: the video game World of Warcraft. In this fantasy world without liberal modern states, and where armed violence is portrayed as a regular state of affairs, this article asks whether a distinct mode of exceptional security can still be identified.

World of Warcraft (WoW), launched by Blizzard Entertainment in 2004, is one of the first and most popular MMORPGs (massively multiplayer online role-playing game) in history, with 12 million players at its 2010 peakFootnote 10 and professional gamers attracting millions of followers on streaming platforms today.Footnote 11 What matters for this article is less its cultural and economic significance, or its role in co-constituting what its gaming audience perceives as security issues, than its potential as a thought experiment about security dynamics in a large fictional world. In one sense, a world of ‘Warcraft’ could be assumed to have securitisation as its premise, and thus lack contrasting normal politics.Footnote 12 In another sense, armed conflict is so pervasive in the game that it may qualify as ‘normal’, thus voiding the relevance of a distinct security realm – an issue also raised regarding societies marked by colonial violence.Footnote 13 By analysing the security discourse in the game's storylines, this article finds that exceptionalist securitisation is significantly present in WoW. Furthermore, what counts as normal and securitised is practically invertedFootnote 14 compared to the ‘real’ (Western) world.Footnote 15

This article seeks to show that Copenhagen School securitisation is only contingently associated to the Schmittian or liberal state of exception and to their normative pitfalls. As a careful reading of the School reveals, classical securitisation is better understood around the possibility of an absolute loss of meaning. This article first reviews the critiques of the exception in securitisation theory and how they are tied to the assumption of the Western liberal state. Second, it exposes how popular culture and video games can stimulate theory development in International Relations (IR), and presents some of the existing work on World of Warcraft in other disciplines. Third, it examines what constitutes both normal and exceptional politics in WoW, finding that they require a closer reading of the deconstructive intents in the early Copenhagen School texts. Fourth, it analyses how securitisation shapes political ordering in WoW, where societal and supranational securitisation counterbalance the violence of normal politics, and where state securitisation opens a space for political contestation. The article concludes on the potential normative consequences of this reading of securitisation theory.

The ‘liberal exception’ assumption in critiques of securitisation theory

Since its inception in the 1990s, securitisation theory has mainly evolved through criticism directed at its original Copenhagen School formulation. Even though the Copenhagen Peace Research Institute (COPRI) was dissolved in 2003 and later, ‘Copenhagen School’ productions largely became synonymous with Ole Wæver's individual work,Footnote 16 two of the major securitisation books in the 2010s insist on calling themselves ‘post-Copenhagen’.Footnote 17 While the state of the art in securitisation theory has considerably progressed beyond the theory's ‘classical’ version,Footnote 18 the latter's status as the ‘mainstream’ of critical security studies and as a ‘foil’ for much contemporary securitisation scholarship makes it important to study closely.

The focus here will be on one specific aspect of classical securitisation theory, the ‘logic of exception’, which has been contrasted to the ‘logic of routine’.Footnote 19 The latter evolved from critiques emitted by scholars such as Didier Bigo or Jef Huysmans regarding the empirical relevance of locating security in the exceptional, as opposed to concrete institutionalised practices. This article will leave aside such routine-based criticisms, as they pertain more to the empirics than to the structure of the theory. While recent theoretical contributions have mostly been critical of the exceptionalist version, empirical literature remains largely reliant on the Copenhagen School,Footnote 20 which statement of securitisation may read as such:

The answer to what makes something an international security issue can be found in the traditional military-political understanding of security. In this context, security is about survival. It is when an issue is presented as posing an existential threat to a designated referent object … The special nature of security threats justifies the use of extraordinary measures to handle them.Footnote 21

Given such a phrasing, it comes to no surprise that both empirical and theoretical literature assumed securitisation theory to reflect the state of exception as developed in the modern, Western, liberal sovereign state. This ‘liberal exception’ assumption is mirrored in many critiques.

The German jurist Carl Schmitt was brought into the discussion of securitisation theory by Jef Huysmans and later Michael Williams.Footnote 22 In Political Theology and The Concept of the Political,Footnote 23 Schmitt lays out two interrelated propositions: any legal order may be suspended with a sovereign decision to declare an exception; and the political is founded in a friend/enemy distinction that ultimate expression lies in the possibility of war and physical death. These positions influenced Schmitt's adhesion to the Nazi party in 1933–6.Footnote 24 Although Wæver had not engaged with Schmitt until these debates,Footnote 25 he now states that the theory's concept of security is Schmittian, coupled with an Arendtian concept of politics.Footnote 26 Despite these ambiguous roots, many scholars have assumed that exceptionalist securitisation is ‘inspired primarily by Carl Schmitt’.Footnote 27 Claudia Aradau suggests that Copenhagen School securitisation ‘activates a Schmittian politics’ that endows it with a ‘non-democratic, exceptional and exclusionary logic’.Footnote 28 Securitisation, as a form of ‘panic politics’ in which ‘we must do something now, as our very survival is at stake’, seemingly reduces the possibilities for deliberation to a minimum.Footnote 29 Not only it tends to enact normatively undesirable forms of politics;Footnote 30 by focusing on this manifestation of security, the securitisation analyst risks reinforcing the very forms of security she intended to question,Footnote 31 to the detriment of other security claims articulated by marginalised groups.Footnote 32

In Ken Booth's words, ‘the language of “securitisation” freezes security in a statist framework, forever militarised, zero-sum, and confrontational’,Footnote 33 inexorably bound to a certain conception of the Western state. The assumption that securitisation refers to ‘the state's initiation of exceptional, sovereign interventions to protect its ongoing existence’,Footnote 34 implying a ‘militarized response’,Footnote 35 is still commonplace in the empirical literature. The exceptional/normal divide is seen to reflect the ‘long-critiqued distinctions between high and low politics’ that feminism sought to problematize.Footnote 36 ‘Exceptional measures’, in short, are interpreted in the mould of stately ‘exceptionalism’, whether directly inspired by Schmitt or as later developed by Giorgio Agamben.Footnote 37 Given that such exceptionalism is bound to the development of the liberal state and to what Foucauldian security scholars called the ‘liberal way of war’,Footnote 38 earlier securitisation literature often supposed that ‘[i]t is in relation to the procedural “normalcy” of democracy that the “exceptionalism” of securitization can be theorized.’Footnote 39 Already too realist in the Schmittian sense, securitisation theory is now too liberal, and possibly unadapted outside the Western world.Footnote 40

Some recent proposalsFootnote 41 substitute the Schmittian exception in securitisation theory with Andreas Kalyvas's concept of the ‘politics of the extraordinary’, which sought the foundings of democracy in ‘those infrequent and unusual moments when the citizenry, overflowing the formal borders of institutionalised politics, reflectively aims at the modification of the central political, symbolic, and constitutional principles and at the redefinition of the content and ends of a community.’Footnote 42 While Kalyvas's work may spotlight the security speech act's ‘insurrecting potential to break the ordinary’,Footnote 43 the existential threat is lost in translation. Indeed for the Copenhagen School, ‘securitization is not fulfilled only by breaking rules (which can take many forms) nor solely by existential threats (which can lead to nothing), but by cases of existential threats that legitimize the breaking of rules.’Footnote 44 The ‘existential threat’ half of the speech act remains interestingly underdeveloped to this day. Juha Vuori, in pinning down a cross-cultural securitisation logic, tautologically claims that ‘something is an existential threat for a referent object that should continue to exist’,Footnote 45 while Holger Stritzel awkwardly defines securitisation as constructing ‘a threat … that is so existential’ that it legitimises special measures.Footnote 46 Jef Huysmans follows then-neorealist Barry Buzan in relating the existential threat to the ‘autonomy’ and ‘functional integrity’ of political entities.Footnote 47 One possible exception to this trend is Rita Floyd's theory of just securitization,Footnote 48 which defines the existential threat as pertaining to the ‘essential properties’ of the referent object.

This article argues that the ‘liberal exception’ assumption in securitisation theory is informed by an inattentive reading of Wæver's early work, particularly of his formulation of the ‘existential threat’, and that the links between securitisation and ‘the traditional military-political understanding of security’Footnote 49 are contingent, not constitutive. This theoretical argument could be made in a detached way, simply on the basis of Wæver's writings. Yet this would raise questions for the argument's relevance: can securitisation actually work in an unambiguously non-Schmittian mode, and what happens when it does? To answer that question, I rely on the fact that securitising discourse can be used in Western popular culture in a mode that is far removed from the state-centric, authoritarian, and ironically Western view of security. The next section explores the place of popular culture and video games in IR, and lays out this article's use of World of Warcraft.

Popular culture, video games, and IR

Securitisation theory has been deployed to analyse how popular cultural artefacts may be leveraged in real-world securitising discourse.Footnote 50 Beyond the role of visuality in constructing security issues, its engagement with popular culture remains limited.Footnote 51 This is perhaps surprising given how securitisation patterns can be very explicit in fiction, as when the main character in the Splinter Cell: Blacklist video game reflects on having been granted ‘the right to defend our laws, by breaking them’.Footnote 52 Many IR frameworks have been proposed for the study of popular culture.Footnote 53 Charli Carpenter summarises three main approaches: ‘pedagogical’, drawing analogies between popular culture and IR concepts; ‘interpretive’, providing data for how societies think of themselves; and ‘explanatory’, examining causal or constitutive effects of popular culture on world politics.Footnote 54 The first relates to Iver Neumann and Daniel Nexon's ‘mirror’ approach, which describes the use of popular culture as both an analogical ‘medium for exploring theoretical concepts, dilemmas of foreign policy, and the like’Footnote 55 and a tool for communicating IR to the classroom or to a broader audience.Footnote 56 Most studies in the ‘mirror’ approach have a pedagogical or illustrative purposeFootnote 57 rather than try to draw novel theoretical arguments from popular culture itself. An attempt to the latter may be the use of Battlestar Galactica as a ‘quasifactual’ world where the nuclear taboo does not exist,Footnote 58 but even these authors claim only to ‘[raise] awareness of the contingent nature of the real-world nuclear taboo' through a ‘fruitful exercise’ providing ‘illustrative material’.Footnote 59

Literature on video games and world politics is primarily rooted in the field of game studies, which largely examined the links between military games and militarism broadly speaking, as well as video games’ colonial and capitalist underpinnings.Footnote 60 IR scholarship on the matter tends to focus on military video games, mainly first-person shooters but also strategy games and role-playing games.Footnote 61 While IR attention has also been cast on the utopian and dystopian aspects of virtual worlds, as well as on humanitarian anti-trafficking games,Footnote 62 the discipline has retained, in Felix Ciută's words, a ‘narrow focus on war-themed blockbuster games’.Footnote 63 Methodologically, Nick Robinson encourages to approach video games from the three angles of the narrative, the visual, and the gameplay; while Ciută, in line with a broader movement in popular culture and world politics, calls for analysing the dynamics of whole game genres and of audience circulation instead of taking individual games out of their socioeconomic context.Footnote 64

From these regards, the present article may first appear conservative in its methodology and choice of case. First, it strictly focuses on World of Warcraft's discursive content and eschew gameplay mechanics, audience reception, and the broader industry WoW is located in. This choice is nevertheless motivated by the scale of the fictional world the MMORPG genre (and WoW in particular)Footnote 65 can accommodate, which provides in itself considerable discursive material. WoW storylines are furthermore unaffected by player choice.Footnote 66 By using a fictional world as a thought experiment to observe and stimulate an existing theory, this article further develops Robinson's claim that video games can ‘enhance theoretical understanding’, in particular through ‘foundation-revealing’ scholarship that uses video games to ‘open up gaps and reveal the foundations upon which theory is based’.Footnote 67

Second, WoW is indeed a war-themed blockbuster game. Yet contrary to the realistic settings of most games studied in IR, WoW's fantasy world seeks little to emulate the real-world conduct of politics. It is rife with cartoon-like, visually non-realistic violence, and shuns the overt philosophical depth that is more frequent in science fiction. Academically, WoW has been the object of extensive scholarship in fields including cultural and communication studies, psychology, anthropology, sociology, or philosophy.Footnote 68 While scholars have approached the game on the performance of gender and sexuality, the racialisation of both players and the game world, or the embeddedness of capitalist ideology in the game,Footnote 69 few works have specifically addressed the game's relationship to other aspects of politics – mostly war, through cultural or legal angles.Footnote 70 This article hopes to highlight overlooked elements of the game thanks to the lenses of international politics and security studies.

In World of Warcraft, the player creates and controls a character that can explore a virtual world, fight creatures, interact with in-game characters, and engage in various activities. Although the game is online and multiplayer, all characters mentioned beside the player's will be assumed to be non-playable. Characters utter greeting sentences and sometimes have written lines; some of them give quests, tasks that the player must perform for a reward, and which are the main support for the game's various storylines. A story arc is usually made of one or several ‘quest chains’ taking place in a given geographical zone. The original WoW from 2004 has been modified through successive ‘expansions’, which added new main storylines associated to new regions. These expansions are The Burning Crusade (TBC, 2007), Wrath of the Lich King (WotLK, 2008), Cataclysm (Cata, 2010), Mists of Pandaria (MoP, 2012), Warlords of Draenor (WoD, 2014), Legion (2016), Battle for Azeroth (BfA, 2018), and Shadowlands (SL, 2020). Besides Cataclysm, which altered many zones from the original WoW, each expansion is relatively standalone, and all expansions can be played today.

Empirical data for this article includes text from quests, in-game dialogues, and dungeon and raid descriptions, including content deleted during later updates. I have been a player since 2013, and have additionally taken notes while playing the WoD, Legion, and BfA expansions with characters from both Horde and Alliance, the game's two umbrella factions. For practical reasons, I later gathered the text from the user-maintained website Wowpedia,Footnote 71 which I consider by experience to be largely reliable regarding such material. I only downloaded text from quests and dialogues that I had played beforehand in the game. References to in-game content are indicated in brackets by the name of the quest followed by the expansion it takes place in. To limit data collection, I have overlooked the earlier Warcraft games (starting from 1994), the many books (including 29 novels) considered part of the franchise, as well as the latest Shadowlands expansion.

Results are highly consistent within and across all expansions. The World of Warcraft universe exceeds even the levels of hostility expected by Schmittian political thought, rendering this common assumption about exceptionalist securitisation inapplicable. It pushes to redefine what counts as an existential threat through Wæver's early arguments about the loss of all meaning. This logic allows to better understand securitisation as shaping the limits for ‘what can be imagined’ within a political community, and therefore setting what does or does not qualify as normal politics therein.

World of Warcraft's challenge to securitisation

The existential threat: Schmitt and the deconstruction of realism

On the surface, World of Warcraft seems to depict a very Schmittian understanding of politics. Sharply defined ‘factions’, which names are indicated in or under their members’ onscreen names, routinely engage in physical violence and discursive otherisation against each other. However, a closer reading of Schmitt reveals an important mismatch between his theory and WoW. The possibility of violent death is fundamental to his concept of the political, as ‘the friend, enemy, and combat concepts receive their real meaning precisely because they refer to the real possibility of physical killing’, as opposed to mere ‘competition’ or ‘symbolic wrestlings’.Footnote 72 Conversely, ‘the readiness of combatants to die’ and ‘the physical killing of human beings who belong on the side of the enemy’ can only be justified within the political, as it ‘has no normative meaning, but an existential meaning only’:Footnote 73

There exists no rational purpose, no norm no matter how true, no program no matter how exemplary, no social ideal no matter how beautiful, no legitimacy nor legality which could justify men in killing each other for this reason. If such physical destruction of human life is not motivated by an existential threat to one's own way of life, then it cannot be justified.Footnote 74

Herbert Marcuse comments this passage: ‘What, then, remains as a possible justification? Only this: that there is a state of affairs that through its very existence and presence is exempt from all justification.’Footnote 75 Yet many, if not most, recourses to physical killing in WoW are justified by mere norms and rational purposes. This is true for most in-game peoples, despite stark differences in their handling of politics. A peaceful Pandaren invokes limited justification to send the player killing sprites, small wooden humanoids who are capable of speech: ‘Ugh! I hate sprites! They totally give me the creeps! They're so small, and … and … they jump on you and … and … they have cold, dead little stick hands! … Get rid of those things, please!’.Footnote 76 At the other cultural extreme, when the player frees an Orc gladiator of the Laughing Skull clan who is forced to fight in an arena, he exclaims ‘Now I can kill who I want, when I want!’.Footnote 77 While Schmitt judges that ‘to demand seriously of human beings that they kill others and be prepared to die themselves so that trade and industry may flourish for the survivors … is sinister and crazy’,Footnote 78 two in-game peoples with highly capitalistic cultures, the Goblins and the Ethereals, engage precisely in this.Footnote 79 One thing that Schmitt does accurately suggest is that ‘war’, even in WoW, must involve securitisation. The word ‘war’ is used sparsely in the game and only applies to large-scale military campaigns: the Horde and the Alliance are not described as being at war until Battle for Azeroth, despite being engaged in deadly military clashes throughout every expansion.

In WoW, and contrary to Jef Huysmans's argument, the ‘ordering force of the fear of violent death’ found in ‘Schmittean political realism’Footnote 80 would seem an inadequate basis for the ‘existential threat’ of classical securitisation. But before suggesting another definition of the ‘existential threat’, the Copenhagen School's relationship to exceptionalist state security must be specified. Ole Wæver's wording can make it easy to interpret securitisation as conservatively reproducing the traditional security logic and extending it to non-military sectors.Footnote 81 But this reliance is based on the claim that ‘security, as with any other concept, carries with it a history and a set of connotations that it cannot escape’ and on the contingent observation that ‘[t]here is no literature, no philosophy, no tradition of “security” in non-state terms.’Footnote 82 This has important normative implications: as Wæver argues in ‘Security, the Speech Act’ in a critique of the critical IR scholars of the late 1980s, ‘metaphysical concepts like sovereignty and state’ keep ‘show[ing] up in new forms’ when denounced.Footnote 83 Such a view is indebted to Jacques Derrida who, speaking of some of the founding blocks of Western metaphysics, claimed that:

it is not a matter of ‘rejecting’ these notions: they are necessary and, at least today, for us, nothing is thinkable without them anymore … We must even less give up these concepts in that they are today indispensable for us in order to shake the legacy they are part of.Footnote 84

These ‘movements of deconstruction’ are ‘necessarily operating from the inside’Footnote 85 of the established system of thought, from the inside of what Derrida calls the clôture (‘closure’ or ‘enclosure’). Indeed, any break in the tradition ‘reinscribe[s] itself, fatally, in an ancient fabric which must be interminably unraveled’.Footnote 86 ‘There is not a transgression’ if it means installing oneself in some kind of outside, superior truth that was alledgedly not born in the enclosure.Footnote 87 Wæver closely follows Derrida's deconstructive approach when he calls for working with realist concepts ‘in a way which is faithful – but too faithful’, by ‘asking patiently for the intrinsic meaning of the concept’ until it is ‘not able anymore to function in the harmonious self-assured standard-discourse of realism’.Footnote 88 Wæver's deconstruction of the existential threat is first found in ‘Security, The Speech Act’ and then reiterated in ‘Securitization and Desecuritization’:

The basic definition of a security problem is something that can undercut the political order within a state and thereby ‘alter the premises for all other questions’. Threats seen as relevant are, for the most part, those that effect the self-determination and sovereignty of the unit. Survival might sound overly dramatic but it is, in fact, the survival of the unit as a basic political unit – a sovereign state – that is the key. Those issues with this undercutting potential must therefore be addressed prior to all others because, if they are not, the state will cease to exist as a sovereign unit and all other questions will become irrelevant.Footnote 89

As restated in the Framework book, ‘If one can argue that something overflows the normal political logic of weighing issues against each other, this must be the case because it can upset the entire process of weighing as such: “If we do not tackle this problem, everything else will be irrelevant …”.’Footnote 90 The basic argument of securitisation is that if the threat is left unchecked, everything else will lose its meaning. The securitising speech act constructs the referent objectFootnote 91 and frames it as what holds the world together.Footnote 92 If the referent object is removed, all meaning falls apart, making it impossible to grasp or deal with any reality. The world cannot be imagined without it. Physical death is only one possible case of such a breakdown, and whether this death is violent matters little. In this reading, the friend-enemy distinction and its controversial baggage are unnecessary.

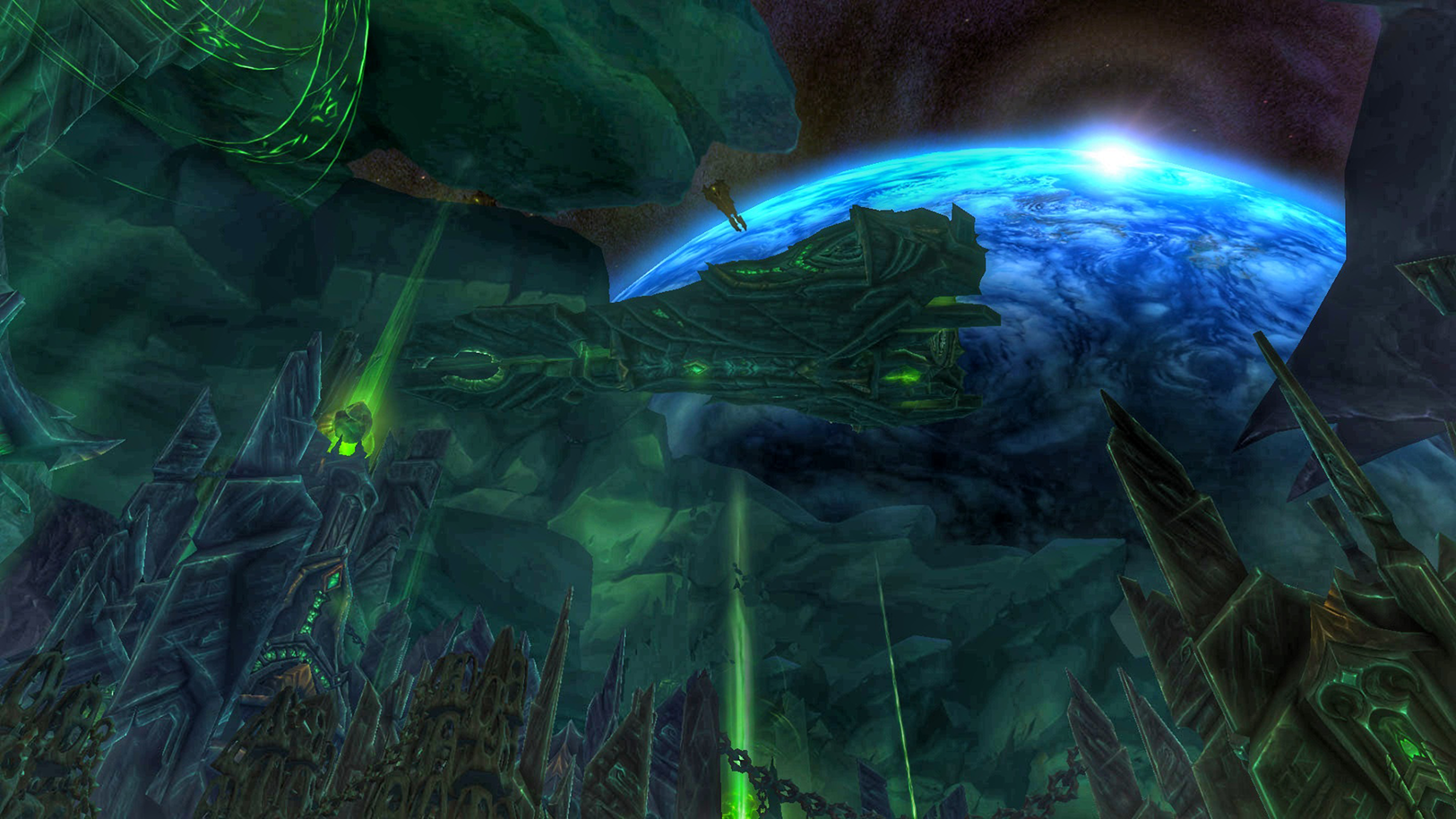

Securitisation enacts the boundaries for what can or cannot be imagined. Rather than by referring to a mythical past state of nature, securitisation works by intensifying the possibility of a future where the ‘world’ falls apart.Footnote 93 In this ‘barely imaginable future’, the only depictable thing is the destruction of the referent object; by definition, none of the rest can be grasped. Visions of a barely imaginable future, sometimes through past examples of ‘the unthinkable’ happening, are fundamental to the construction of security in World of Warcraft. The two worlds in the game, Azeroth and Draenor/Outland, are overwhelmingly scarred by past demon invasions: the first was flooded undersea and is marked with a maelstrom where the demons arrived; and the second exploded into floating debris. Such references can be explicitly leveraged in securitising discourse, as when one enemy ‘is channeling too much power to this place. If he's not to stop, Azeroth will be the next Outland!’.Footnote 94 When the demons invade Azeroth again in Legion, their devastated homeworld Argus becomes the ominous exhibit for a demon-dominated future, and is contrasted both with the pristine blue planet of Azeroth (Figure 1) and the still-glorious ruins from the demon world's former inhabitants (Figure 2). Elsewhere, forms of time travel are used to depict what the world could become if a threat is not stopped, or what it used to be before falling to an uncountered threat.Footnote 95 Numerous antagonists in WoW visually demonstrate their capacity for unprecedented destruction at their first appearance, and environmental devastation is often involved, to the point of being colour-coded to signal a given antagonist.Footnote 96 When playing the game, the visual securitising power of such displays of destruction is obvious.Footnote 97 Securitisation is indeed abundant and significant in WoW, where it plays a major role in moving storylines forward and endowing them with emotional force.

Figure 1. The world of Azeroth seen from the demon world Argus.

Source: World of Warcraft: Legion, courtesy of Blizzard Entertainment, Inc.

Figure 2. Remnants of Argus's past civilisation floating above the ravaged planet.

Source: World of Warcraft: Legion, courtesy of Blizzard Entertainment, Inc.

Exceptional measures: Rules, honour, and magical powers

The theoretical arguments above suggest that securitisation can function in World of Warcraft, despite the prevalence of normalised violence in that universe. This subsection shows how securitisation works in WoW by separating normal politics, associated with honour and revenge, from exceptional politics, often linked to powerful magic. As WoW is already used to inform securitisation theory, one cannot apply a detailed securitisation analysis to WoW without falling into methodological circularity.Footnote 98 This is why it would be unwise here to study the representational politics of how security is portrayed in the game, as would be more obvious to do in many IR works on pop culture.Footnote 99 The aim is rather to expand on a corollary of the ‘barely imaginable future’: facing the unimaginable suggests the use of hitherto scarcely imaginable means to thwart it. A properly constructed existential threat thus implies the legitimation of exceptional measures.

Indeed, the Framework book poses a very low threshold for what counts as exceptional, defined counterfactually as having broken ‘free of procedures and rules [one] would otherwise be bound by’ had securitisation not occurred.Footnote 100 The ‘exceptional measures’ of classical securitisation theory, in other word, have no meaning independent of the securitising act. Indeed, following Juha Vuori, ‘we cannot define “special politics” very specifically. However, we can say that all societies have “rules”.’Footnote 101 For Huysmans, securitisation ‘defines what counts as normal or democratic in the very act of identifying what is considered abnormal or non-democratic’.Footnote 102 In the rest of this article, I rely on a narrow criterion for WoW securitisation, only considering explicit speech actsFootnote 103 constructing an existential threat. This deliberately leaves out institutionalised forms of security, where certain matters have been integrated as inherently securitized,Footnote 104 as well as phrases that have become ‘master signifiers’ with securitising connotations.Footnote 105

A substantial part of the armed violence in WoW is justified by the logic of ‘crimes to be punished’ or of ‘honour to be avenged’. This justice-like logic is not usually combined to claims of existential threat, though it often constructs a radical Other.Footnote 106 Compare the following declarations:

1. A Tuskarr villager: ‘Everyone I knew was slain, including my father Ariut. By tuskarr law I must seek retribution against those who shed my kin's blood.’

2. A Human ghost: ‘The very men who destroyed our village and slew our fellows toast their “amazing victory” while we are helpless to avenge the fallen. We must not allow these crimes to go unanswered! Be the instrument of our vengeance … Go to Sunfury Hold and claim the lives of those responsible for this crime.’

3. A Thorignir dragon: ‘The dragon who guided you to me awaits his vengeance against the vrykul. Together I wish for you to show these Drekirjar what it means to cross the Thorignir. Their toll must be paid in blood.’

4. An Orc warrior: ‘These defilers – the lice-ridden wolf-men running rampant over the shrine – dishonor this memory of the wolf god. They arrived with the Twilight's Hammer, howling with their own twisted religion. They seek to corrupt noble Lo'Gosh to fit their own warped pantheon. Kill them!’Footnote 107

The difference between the logic of justice and that of securitisation is sometimes explicit. The Grummles of Mists of Pandaria, whose worldview is based on notions of good and bad fortune, move packages on roads that are regularly attacked by the Hozen people. Their violent deaths at Hozen hands appear as limited matter for concern: ‘The Broketooth hozen south of here killed all of my grummles. What is worse, their packages are undelivered. Fortune frowns on a grummlepack undelivered.’Footnote 108 Yet one Grummle insists that ‘we have very few grummles these days’ and asks the player to ‘destroy some of the Broketooth hozen’, arguing that ‘this is not vengeance or fortune, it is survival.’Footnote 109

The WoW logic of securitisation, defined by reference to an existential threat, often involves recourse to heroic actions by the playerFootnote 110 or to especially powerful magic. In a lush jungle that is partly devastated by the undead Scourge (WotLK) – a vision of a barely imaginable future – the use of an ancient weapon is framed in explicit and detailed securitisation grammar:

the Scourge's invasion has not slowed down. The situation is becoming desperate … There exists a last resort … To ensure the safety of their experimentation sites, the titans created a defense mechanism. Its destructive force is unparalleled … It borders on sacrilege that these secrets be revealed to a mortal such as yourself, but I have little choice. … Life must be protected at any cost.Footnote 111

More generally, the grammar surrounding such magical measures insists on them being uncommon, distant in place or time, difficult or dangerous to attain, rare or unique in kind, and/or historically significant. Rarely are these magical measures entirely ‘new’, as they are often rooted in a mythical or legendary past; it is their invocation ‘here and now’ that is framed as extraordinary. As a village cleric says in MoP:

I was taught many rituals, and have performed all of them, save one. There was one, an extremely ancient one, that we were told to call upon if our people ever turned against us. This must have happened in our people's distant past, because we haven't needed to use it in our village's memory. I suppose now is the time to do so.Footnote 112

Exceptional measures in WoW are defined less negatively as the breaking of rules than positively as the recourse to awe-inspiring magic. This hints at normative implications: in WoW, securitisation is largely seen as desirable. The next section will develop how securitisation maintains order in the game universe.

Securitisation as world order: Enacting political communities

By declaring which objects are necessary for imagination, and by separating normal from exceptional politics, securitisation shapes political communities. This extends beyond democratic communities;Footnote 113 a community that securitises the nation is different from one that securitises its territory, or from one, like the capitalistic Goblins in World of Warcraft, that rarely securitises anything. Such a reasoning can be extended to the international order. This section's argument falls in line with Jonas Hagmann's claim that ‘securitisation produces worlds imageries’ and ‘effectively systematises the international’. In asserting ‘who threatens whom and why’, securitisation ‘populates the international with distinct relations and actor formations’, and thus ‘describes nothing less than the international reality in which a country finds itself’.Footnote 114

An attentive player of WoW can be struck by how the relative importance of securitisation sectors differs from the real world. The sectoral analysis of security was first presented in Barry Buzan's People, States and Fear,Footnote 115 15 years before it was combined with securitisation theory in the Framework book. While there have been later attempts to delimitate additional sectors in religion or cybersecurity,Footnote 116 the sectoral framing has faded out of securitisation scholarship, which nowadays focuses on specific topics rather than pinning them to a concept of sector. Several of Buzan's sectors nevertheless emerge in World of Warcraft with distinctive securitisation dynamics. This is additionally noteworthy given that, due to the ubiquity of armed violence, the military sector should have overshadowed the other ones and voided the interest of a sectoral analysis. Instead, the opposite seems to have happened: the military sector in WoW is emptied of its substance, made of small-scale securitisations with little impact on the broader pattern of relations.

This section will describe the international order in WoW through its sectoral dynamics. Its claims are based on the whole of WoW, but it relies on the Legion expansion for examples.Footnote 117 Released in 2016, Legion is one of the most appreciated expansions among current WoW players.Footnote 118 The storyline revolves around an invasion of the Burning Legion demons, who threaten to wipe out all life on Azeroth after having ravaged countless other worlds. They established a foothold in the Broken Isles, where they occupy the ancient city of Suramar to exploit its magic resources for their war efforts. The player is part of a worldwide military coalition against the demons and must retrieve powerful artefacts scattered around the Broken Isles. She must convince the locals to offer their help, usually in return for support in their own political issues. In WoW, securitisation fills in the role of international norms and organisation and compensates the violence of normal politics.

In the real world, military security is traditionally about the protection of the state.Footnote 119 In World of Warcraft, the state is not a distinctly military concern until the seventh expansion, Battle for Azeroth. Once the state is removed, the military sector is left concerned with territorial losses and military bildups in the opposite camp. Both concerns are found throughout the game. Calls for protecting a military position or village are common, but often fail to invoke measures beyond ordinary fighting, except perhaps when an enemy is suspected to acquire a powerful weapon.Footnote 120 In the absence of the state object, and given the strong normalisation of military violence, military securitisation is often subordinated to other kinds of securitisation and cannot propel a major storyline on its own.

Rather than a state, the referent object that is most often constructed as existentially threatened by armed violence is a ‘people’ or nation. The coincidence between nation and state has been associated to modern statehood, yet this coupling is often so strong in WoW that it makes little sense to securitise the state instead of the nation. The societal sector thus absorbs most of the military sector's substance. The three main ‘threats’ to societal referents in the Framework book – migration, external cultural influence, and integrating or secessionist projects – are practically unheard of in WoW securitisation. Yet ‘depopulation’, which ‘is not specifically part of the societal sector's logic of identity, except perhaps in cases where extermination policies are motivated by the desire to eliminate an identity and in extreme cases – such as AIDS in Uganda – where quantity turns into quality’,Footnote 121 is commonplace following these two cases. Societal securitisation then seems to safeguard against the extinction of entire collectives through armed violence. On the Broken Isles, a group of blue dragons, guardians of magic, try to survive after the political institution they belonged to was disbanded. They are attacked by exiles from Suramar who try to fulfil their addiction to magic. The exiles both tap into the region's magic faultlines, on which rests the blue dragons’ culture (‘Without the power of the ley lines, we are nothing’),Footnote 122 and try to vampirise young dragons for their magic (‘we can no longer bear eggs. My whelplings are the last of the last. I need you, champion. Help defend my whelplands’).Footnote 123 By securitising the survival of their culture and people, the blue dragons draw the involvement of the player, who eventually saves them.

In WoW, the environment is highly institutionalised, with nature spirits able to securitise their own survival and with immediately visible threats. These factors all lack in the real world and contribute to the success of environmental securitisation, effectively framing ecosystems as state-like entities with a physical and political integrity. However, due to the extreme correlation between nation and state and the pervasiveness of the environment for the rest of the international order, these ‘environmental states’ do not give rise to distinct securitisation dynamics, which remain societal or supranational. On the Broken Isles, druids from the forest of Val'sharah cannot wake up from their magical sleeps, and pacifists must resort to killing aggressive creatures. Alongside this institutional disturbance, the druids’ ‘precious land’Footnote 124 turns red, with the flora and fauna corrupted by the ‘greatest threat Val'sharah has ever faced’.Footnote 125 The securitisation of this red corruption has a societal referent object made of a community of druids, animals, and plants. At the same time, it is made clear to the player that the threat to Val'sharah would impact other national groups in the broader world, not least those who are part of the player's international coalition.

The securitisation of a supranational referent, while seldom considered effective in the real world, is fundamental in WoW. Every expansion is driven by at least one main antagonist posing an existential threat to ‘the world’ as a whole, and lesser examples of supranational securitisation also exist at the scale of a region or zone. Supranational securitisation overcomes the strong national cleavages in WoW's political order. A local faction may use it to draw the attention of other parties, such as that of the player and of larger factions she works for, in a way that Hagmann also noticed at play in real-world Europe.Footnote 126 Supranational securitisation is regularly leveraged to call for cooperation between multiple entities (‘They thought they were ready for us, but they've never seen the forces of Azeroth work with such unity’)Footnote 127 or to maintain it (‘we cannot allow the rest of this land to fall into the demons' foul grip. [The demon general] has dispatched his forces across the Broken Isles, threatening the homelands of the allies you have made’).Footnote 128 Rejecting supranational securitisation then paradoxically becomes a way of reasserting one's sovereignty, as when a local queen declares that her domain is exclusively under her ordinary rule: ‘“Demons” you say? A “Burning Legion?” Hrmph! Nothing burns here but for my ire, shaman, and if these monsters think to corrupt my domain, they will be crushed beneath my dainty beautiful feet!’.Footnote 129 Because they put in check the everyday violence, national and supranational securitisation are overwhelmingly cast as normatively positive in WoW, with a couple noteworthy exceptions.Footnote 130

WoW's the later expansions, which are more sophisticated in terms of storyline and gameplay, complicate this international picture through the rise of state referents in Legion and Battle for Azeroth. The Broken Isles have two such examples, Highmountain and Suramar. These state referents are forged through repeated securitising acts that invoke a territory, people, and political institution interchangeably. The ‘Highmountain’ referent thus simultaneously designates a geographic region, an economy and ecosystem, the various peoples who live therein, a ruling dynasty, the dynasty's legendary founder, and a shared history. The securitising moves of Highmountain's various leaders assert that these heterogeneous things are not only tied together, but are also fundamental to any imaginable idea of ‘Highmountain’. Such securitisation would thus order members of the majority Tauren people not to imagine a ‘Highmountain’ that rejects the minority Drogbar people, or one that is not united under the ruling dynasty. Securitising moves can thus become part of a battleground over what the state ought to be imagined or imaginable as a political entity. Indeed, normative contestation or rejection of securitising moves becomes much more common starting from Legion's Suramar and into the main political players of BfA.

The city-state of Suramar was shaped by a chain of securitising moves. Each attempted to counter the damage caused by the previous one, profoundly affected the city's political structure and the life of its citizens, and each took as referent object ‘Suramar’, defined as both the city and its population. First, Suramar took the ‘desperate choice’ of shielding itself from the world to survive the first demon invasion.Footnote 131 Second, it had to build a powerful source of magic, the Nightwell, as a drastically addictive food substitute that effectively sentenced to death any Suramar citizen cast outside of the city's limits. Third, as the Nightwell's power attracted the demons again, the queen surrendered the city as a price for not being deprived of the vital Nightwell (‘I could not allow my people starve … Now I see a future where the Legion is victorious and my people endure … I will do everything in my power to make it so!’).Footnote 132 Crucially, the queen came to this decision after having failed to see (or imagine) any future where the demons would be defeated – or alternatively, any future where Suramar would not depend on the Nightwell.Footnote 133

The storyline follows an exiled Suramar official who rejected the queen's securitising move and organises a popular rebellion. For the rebels, an alternate mode of organisation is possible for Suramar: one where its inhabitants would be cured of their dependency to the Nightwell, and where Suramar would break its isolation to join forces with the international coalition against the demons. While the concrete insurgency is played in the registers of justice and normal politics, the rebels’ two ideals involve securitisation. With the first, extreme efforts are required to nurture a magical tree (‘If we fail, Suramar is doomed’).Footnote 134 As for the second, in the xenophobic Suramar society, foreign help can only be justified by an existential threat: ‘The fate of my people rests in the hands of outsiders … all of you … to save us from the terrible bargain made by our queen.’Footnote 135 While all securitise the ‘Suramar’ referent object, it is the object's content that is contested. To justify her defection, an officer affirms that ‘I serve Suramar. All of Suramar.’Footnote 136 In WoW's states, securitisation opens alternative futures, rather than close them.

Conclusion

Much of securitisation scholarship still constitutes itself in opposition to classical securitisation theory, making it worthwhile to clarify the latter's foundations. This article identified a widespread assumption about the Copenhagen School formulation of the theory, namely that the concept of securitisation reproduces the Schmittian state of exception as found in modern liberal states. This assumption, which would suggest securitisation theory to be normatively problematic, misreads Ole Wæver's early work and overlooks the role of Derridian deconstruction in motivating the theory. Classical securitisation theory should instead be viewed around the concept of ‘existential threat’, that is, the possibility of an absolute loss of meaning, in which the disparition of a central referent object would open the door to an unimaginable future. Securitisation frames certain referent objects as a necessary condition for imagining the world. As such, securitisation plays a fundamental role in shaping all forms of political ordering, even through its rejection or absence, and draws the limits for normal and exceptional politics within particular communities.

Such a reading of securitisation allows it to be more adapted to non-Western settings, and brings the question of how securitisation was involved in building the modern state. It also raises possibilities for the normative debate. If securitisation can produce a desirable international normative order in WoW, it might do so in the real world, especially against supranational or environmental threats. While there would be tremendous utility in establishing forms of securitisation that overcomes antagonism between hostile parties, or that ensures protection to threatened populations, significant issues complicate such a vision. Supranational threats in WoW usually take the shape of demons, undeads, or malevolent gods, to whom no compassion nor dignity is offered; and when a less personified threat to the environment arises, the latter can speak and securitise for itself. More importantly, the international order of WoW presupposes possibly unacceptable levels of normalised violence, which may offset the cooperation gained with securitisation. One could still counter this last point by referring to the pervasive violence of colonialism,Footnote 137 which may – or may not be – a sufficient condition for the production of WoW-like securitisation dynamics.

Empirically, the frequent occurrence of securitisation in popular culture narratives would require further attention, especially given the divergence between the ways securitisation is used in such narratives and in the real world. This article finally reiterates the usefulness of popular culture and video games for the study of international politics, including as thought experiments that put forward novel theoretical claims.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Philippe Beaulieu-Brossard, Thorsten Brønholt, Christian Bueger, Rosie Collington, Olaf Corry, Maja Touzari Greenwood, Nicklas Johansen, Mathilde Kaalund, Tobias Liebetrau, Cecilie Tobias-Renstrøm, Natalia Umansky, Anders Wivel, and Ole Wæver for discussions and comments on earlier drafts of this article.

Vic Castro is a PhD Fellow at the Department of Political Science of the University of Copenhagen. Their main research is focused on cybersecurity, science and technology studies, materiality, and securitisation theory, with additional work on popular culture.