Introduction

Professional bereavement experiences

Patient deaths are impactful events for professional caregivers (Papadatou, Reference Papadatou2009; Katz and Johnson, Reference Katz and Johnson2013). The bereavement of professional caregivers after the deaths of their patients is referred to as professional bereavement (Wenzel et al., Reference Wenzel, Shaha and Klimmek2011).

According to previous qualitative studies, in face of patient deaths, professional caregivers experience both short-term bereavement reactions and accumulated global changes (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Chow and Tang2018a). Both of them involve a professional dimension in addition to a personal dimension: the professional dimension derives from the perspective of an active practitioner in the medical process that ends up with the patient's death, and the personal one roots in the view of an ordinary person who witnesses the death of an individual he or she knows (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Chow and Tang2018a).

Shortly after each specific patient death, professional caregivers experience bereavement reactions. Among those reactions, there are physical ones like fatigue (Granek et al., Reference Granek, Bartels and Scheinemann2015, Reference Granek, Ben-David and Shapira2017), emotional ones like sadness, grief (Kain, Reference Kain2013), and guilt (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Fong and Wong2014), cognitive ones like intrusive thoughts (Mak et al., Reference Mak, Chiang and Chui2013), relational ones like disconnections from families and friends (Papadatou et al., Reference Papadatou, Bellali and Papazoglou2002), existential ones like death anxiety (Shorter and Stayt, Reference Shorter and Stayt2010), and spiritual ones like the question of religion (Masia et al., Reference Masia, Basson and Ogunbanjo2010).

In addition to reactions toward each patient death, repetitive death encounters in a professional caregivers’ career can lead to accumulated global changes. Such changes are mainly in two aspects: in personal life, professional caregivers may experience changes in religiousness (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Fong and Wong2014; Granek et al., Reference Granek, Bartels and Scheinemann2015), gain new insights into life and death (Rashotte et al., Reference Rashotte, Fothergill-Bourbonnais and Chamberlain1997), and have reduced reactions to personal losses (Moss et al., Reference Moss, Moss and Rubinstein2003); in professional life, healthcare professionals would experiences changes in terms of professional identity (Gerow et al., Reference Gerow, Conejo and Alonzo2010), commitment to work (Shimma et al., Reference Shimma, Nogueira-Martins and Nogueira-Martins2010), involvement into professional–patient relations (Jackson et al., Reference Jackson, Sullivan and Gadmer2005), and competence (Granek et al., Reference Granek, Bartels and Scheinemann2015). Meanwhile, they might get less sensitive to (Granek et al., Reference Granek, Bartels and Scheinemann2015) and more acceptive of (Rashotte et al., Reference Rashotte, Fothergill-Bourbonnais and Chamberlain1997) patient deaths, and become better at coping (Wilson, Reference Wilson2014).

When describing professional bereavement experiences, both short-term bereavement reactions and accumulated global changes should be involved. These two distinct yet related elements, when combined together, form a comprehensive picture of the phenomenon of professional bereavement, which would benefit both theoretical explorations and practical applications: short-term bereavement reactions depict how each patient death bring immediate impacts on professional caregivers, the understanding of which is the premise of in-time symptom-targeted support. Meanwhile, accumulated global changes bring insights into how patient deaths, as inseparable parts of their careers, gradually shape professional caregivers in fundamental ways. Such knowledge could inform education and care plans.

The lack of a satisfactory assessment tool

In existing quantitative explorations on professional bereavement, findings are incomparable across studies, and conclusions about prevalence, intensity, and predicting factors are hardly reliable, owing to the lack of a satisfactory assessment tool (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Chow and Tang2018b).

When measuring professional bereavement experiences, most previous quantitative studies employed inventories for familial bereavement, such as the Grief Experience Inventory (Feldstein and Gemma, Reference Feldstein and Gemma1995), Inventory of Complicated Grief (Anderson and Gaugler, Reference Anderson and Gaugler2006), and Texas Revised Inventory of Grief (Anderson and Ewen, Reference Anderson and Ewen2011). In these measurements, the whole “professional dimension” is omitted. Meanwhile, the only preexisting specific measurement tool for professional bereavement experiences — the Adult Oncologists Grief Questionnaire (Granek et al., Reference Granek, Krzyzanowska and Nakash2016) — has several critical limitations: to begin with, the tool was not based on clear and explicit operational definitions, and accumulated global changes were not covered. In addition, its generalizability is limited as all the empirical studies it relied on for item generation were conducted exclusively among oncologists from Isreal and Canada. Moreover, it has not been strictly validated among an eligible sample so that the quality of its items, its factor structure, and its credibility all remained unknown.

The present study

The present study aims to develop and validate Professional Bereavement Scale (PBS), a specific measurement tool for professional bereavement experiences that is clearly defined, comprehensive, rigorously tested, and generalizable.

Method

Design

Since professional bereavement experiences involve two distinct yet related elements, namely, short-term bereavement reactions and accumulated global changes, two subscales were planned for the PBS. They are the Short-term Bereavement Reactions Subscale (PBS–SBR) and the Accumulated Global Changes Subscale (PBS–AGC). A cross-sectional design was adopted, and data were collected through an online survey.

Measurements

The online questionnaire consisted of three parts: basic information, items for the PBS, and measures for validity tests.

Basic information

Information about the professional caregivers themselves and their most recent patient death experience were collected.

Item generation for the PBS

Items (they are in simplified Chinese and were translated for the present paper) were generated on the basis of a systematic review on previous qualitative studies around the world (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Chow and Tang2018a) and an empirical qualitative exploration in Mainland China.Footnote 1 All open codes (the smallest meaning unit) regarding short-term bereavement reactions or accumulated global changes were extracted, and at least one item was generated for each open code.

For short-term bereavement reactions, the operational definition was “bereavement reactions that manifest within a week after the death of a patient.” Participants were asked to “recall your most recent experience of patient death and rate from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely strong) on the intensity of your reactions within a week after that patient death.”

For accumulated global changes, the operational definition is “changes jointly contributed by all patient deaths in a professional caregiver's career,” and the instruction went “compared with times before you encountered your first patient death, you might have been changed after experiencing all of the patient deaths in your career. Please rate the extent to which you have been changed by patient deaths in each of the following aspects” [0 = no (no such change or the change was not induced by experiencing patient deaths) and 4 = yes, great deal].

The item pool was reviewed by four researchers on bereavement and grief, one physician, and one social science PhD candidate to assure the content validity of the scale (DeVellis, Reference DeVellis2016). Expressions were revised in response to the reviewers’ comments, and 46 and 30 items were included for PBS–SBR and PBS–AGC, respectively (Supplementary Appendix A).

Measures for validity tests

The Chinese Grief Reaction Assessment Form (GRAF; Ho et al., Reference Ho, Chow and Chan2002) and the Professional Quality of Life Scale (ProQOL; Stamm, Reference Stamm2010) were used for validity tests.

GRAF is a tool to measure familial bereavement. Validated among Hong Kong Chinese, it has good internal reliability (Cronbach's alpha = 0.89) (Ho et al., Reference Ho, Chow and Chan2002). This tool was used to reflect familial bereavement in the present study.

Professional quality of life is “the quality one feels in relation to their work as a helper” (Stamm, Reference Stamm2010). ProQOL involves three subscales for burnout, secondary traumatic stress, and compassion satisfaction, respectively (Stamm, Reference Stamm2010). With the permission from the ProQOL Office, the researchers slightly modified expressions in the official Simplified Chinese version.

While the GRAF (Ho et al., Reference Ho, Chow and Chan2002) reflects short-term reactions after a specific death, the ProQOL–burnout subscale focuses on accumulative negative effects of all the impactful events in the career of a helper (Stamm, Reference Stamm2010). Based on the comparability of constructs, the former was used for the construct validity test of PBS–SBR, and the latter for PBS–AGC.

For criterion validity, burnout was used for short-term bereavement reactions. As compassion satisfaction is the general attitude toward the helping job, it was used to test the criterion validity for PBS–AGC.

The secondary traumatic stress subscale measures fear and work-related trauma accumulated in the career, which usually associates with a particular event (Stamm, Reference Stamm2010). As there is no way to ensure that the “particular event” is the most recent patient death, this measurement was only employed to test the criterion validity of PBS–AGC.

Sampling

Formally employed physicians and nurses or medical and nursing students doing clinical practices in urban hospitals in Mainland China who have experienced deaths of at least one patient whom they had treated, cared for, or resuscitated were recruited.

The same sample size was planned for confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) (Nc) as for exploratory factor analysis (EFA) (NE). For EFA, the minimum ratio of sample size to the number of items was set to 5:1 (Bentler and Chou, Reference Bentler and Chou1987). As 46 and 30 items were generated for the two subscales (I 1 = 46, I 2 = 30), respectively, the minimum eligible sample size (N) was calculated as follows:

A combination of convenient sampling and snowballing methods was adopted in participant recruitment. The first few participants were contacted directly by researchers, and they were asked to spread the link for the online questionnaire (on Tencent Questionnaire platform) to eligible participants after they finished the survey themselves.

Data analysis process

Identical steps for scale development and validation were applied for the two subscales. For each subscale, cases with more than 20% of missing items in that scale were dropped, and the excluded participants were compared with the remaining ones in terms of gender, age, and occupation. Missing data in the retained cases were simulated with the expectation–maximization (EM) algorithm (Graham, Reference Graham2009). After that, participants were randomly split into two halves: the calibration sample and the validation sample. The cross-validation method was used, aiming for examining whether the parameter estimates of the calibration sample can replicate in the validation sample (Kyriazos, Reference Kyriazos2018). Such a method could provide valuable information about scale stability (DeVellis, Reference DeVellis2016).

In the calibration sample, item-rest correlations were run to evaluate the consistency of items and drop ineligible ones (DeVellis, Reference DeVellis2016). Then, principal component analysis (PCA) was run with promax rotation and parallel analysis, and items that do not have sufficiently large factor loadings on any of the major components were removed (Matsunaga, Reference Matsunaga2010). After that, EFA (principals axis factoring extraction with promax rotation and parallel analysis) was conducted, and ineligible items were dropped. As factor analysis should always be grounded in theory (Beavers et al., Reference Beavers, Lounsbury and Richards2013), a few items that made sound theoretical sense (e.g., based on open codes revealed in both Chinese and foreign studies) but were not perfectly in line with statistical criteria were also retained in EFA. Eventually, in the validation sample, CFA was run to test the factor structure unveiled in the calibration sample.

While PCA aims to “summarize the information available from the given set of variables and reduce it into a fewer number of components,” EFA is used to “help generate a new theory by exploring latent factors that best accounts for the variations and interrelationships of the manifest variables,” and CFA for testing and existing theory (Matsunaga, Reference Matsunaga2010). The three are different in both theoretical and statistical sense, and they can be used successively to identify the factor structure.

After the structures of both subscales were validated, their reliability and validity were tested among all cases (DeVellis, Reference DeVellis2016).

Eligible criteria for each step of the analysis and related references are listed in Table 1. While the EM algorithm was run with SPSS 25.0 (IBM Corp, 2017), and the CFA was done in Mplus 7 (Muthén and Muthén, 2014), all remaining analyses were conducted in jamovi 0.9.5.12 (Leppink and Pérez-Fuster, Reference Leppink and Pérez-Fuster2019).

Table 1. Steps and criteria adopted in data analysis

Ethical concerns

The present study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Hong Kong (reference number: EA1807022). Participants read the whole consent letter in the first page of the online questionnaire and gave their consent by clicking “I will participate in the research” before formally entered the survey.

Results

Participants

Between August 2018 and December 2018, 563 participants completed the survey. The majority of them are females (87.6%) and nurses (83.3%), and their average age is 32.9 years old (range: 20‒60, SD = 7.82). More information is shown in Table 2. For 499 participants (88.6%), their most recent patient death was not their first patient death in career. Among 401 of them, 144 (35.9%), 163 (40.7%), and 94 (23.4%) experienced less than 10, 10–49, and more than 50 patient deaths in career by the time of the survey, respectively. On average, participants rated the overall influence of the most recent patient death as 1.64 out of 4 (N = 544, SD = 1.291).

Table 2. Basic information about participants (n = 563)

Scale development and validation

The Short-term Bereavement Reactions Subscale

For the validation of PBS–SBR, 25 cases that missed more than nine items were excluded. The excluded participants are of the same age (p = 0.813) and gender (p = 0.492) with the remained ones, but they are more likely to be nurses (100% vs. 82.53%, χ 2 = 5.243, df = 1, p = 0.022) than the retained participants. After data imputation, the remaining 538 cases were randomly assigned into two groups (256 for calibration and 282 for validation).

Since only 13% of the total participants had religious beliefs, the present sample may not be eligible for the validation of R29 “I doubted my religion.” Therefore, this item was excluded, and the remaining 45 were entered into the analysis.

In the consistency test, R4 was deleted for having too low an item-rest correlation. The PCA revealed two main components, and 10 items (R1, R3, R8, R11, R15, R17, R24, R27, R36, and R38) were eliminated for having cross-loadings with absolute values larger than 0.32.

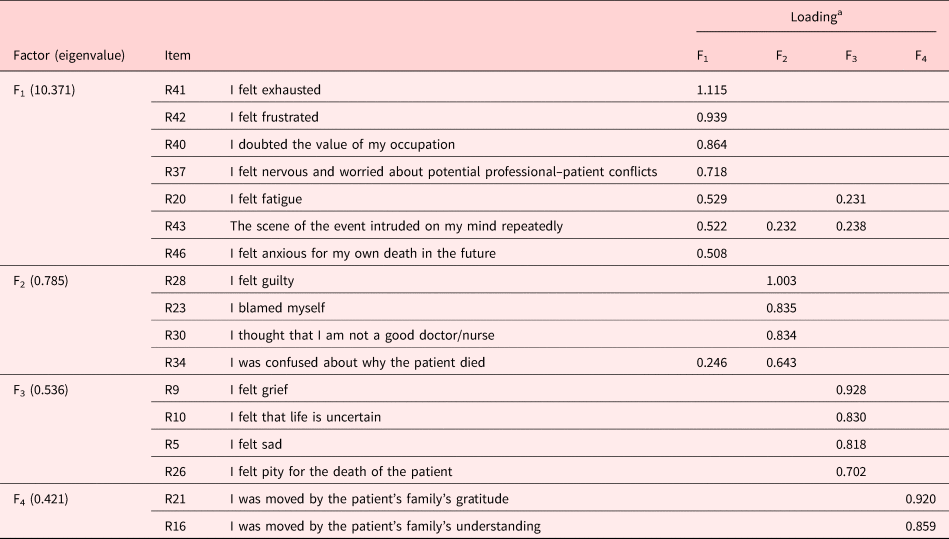

Among the remaining items, Bartlett's test of sphericity was significant (χ 2 = 9,755, df = 561, p < 0.001) and the KMO measure of sampling adequacy was 0.963, thereby indicating suitability for EFA. Parallel analysis revealed four main factors. In the first round of EFA, 13 items (R2, R6, R7, R12, R13, R18, R22, R25, R33, R35, R39, R44, and R45) were excluded for not having a home loading with an absolute value higher than 0.50 or having one or more cross-loadings with absolute values higher than 0.32. Moreover, 4 items (R14, R19, R31, and R32) were deleted for having one or more crossing-loadings with absolute values higher than 0.20 and having no strong theoretical justification for being retained. In the second round of EFA, 1 item (R13) was eliminated for having a home loading (0.431) smaller than 0.5. Eventually, 17 items were retained (for eigenvalues, see Table 3 and the upper part of Figure 1; see loadings in Table 3). Among these items, both Bartlett's test of sphericity (χ 2 = 4,360, df = 136, p < 0.001) and the KMO measure of sampling adequacy (0.945) were eligible.

Fig. 1. EFA (parallel analysis) scree plots for PBS–SBR (upper) and PBS–AGC (lower).

Table 3. Loadings of retained items after EFA for the PBS–SBR

a Loadings with absolute values smaller than 0.20 were omitted.

The outcomes of covariance-based structural equation modeling [CB-SEM; CFI = 0.943, SRMR = 0.0461, RMSEA = 0.0895, 90% CI for RMSEA = (0.0794, 0.0998)] among the validation sample showed that the factor structure revealed in EFA is acceptable (see Figure 2).

Fig. 2. CFA outcome of PBS–SBR.

Based on the items and loadings, the four factors were named “frustration & trauma,” “guilt,” “grief,” and “being moved,” respectively.

The Accumulated Global Changes Subscale

In order to validate PBS-LC, 18 cases were excluded for having missing data on more than five items. There was no difference between the excluded and the remained participants in terms of age (p = 0.894), gender (p = 0.863), or occupation (p = 0.054). After imputation, 269 and 276 cases were randomly assigned for calibration and validation, respectively.

Similar to the case in PBS–SBR, two items based on a premise of having a religious belief, namely, “I have more faith in my religion” (C7) and “My faith in religion is weakened” (C24), were excluded. Item-rest correlations of the 28 remained items were eligible. The PCA revealed two main components, and C21 was eliminated for having cross-loadings larger than 0.32.

Bartlett's test of sphericity was significant (χ 2 = 7,512, df = 351, p < 0.001), and the KMO measure of sampling adequacy was 0.954 for the remaining 27 items. Parallel analysis identified five main factors. In the first and second round of EFA, 8 items (C6, C11, C12, C13, C14, C15, C16, and C20) were excluded for not having a home loading with an absolute value higher than 0.50 or having one or more cross-loadings with absolute values higher than 0.32. Moreover, 2 items (C2 and C23) were deleted for having one or more crossing-loadings with absolute values higher than 0.20 and having no strong theoretical support for being retained. In the second round of EFA, two items (C22 and C28) were eliminated further for not having a home loading with an absolute value larger than 0.50 or having one or more cross-loadings with absolute values higher than 0.32, and 1 item (AC30) was deleted for having one or more crossing-loadings with absolute values higher than 0.20 and having no strong theoretical support for being retained. Among retained items (for eigenvalues, see Table 4 and the lower part of Figure 1; see loadings in Table 4), Bartlett's test of sphericity (χ 2 = 3,622, df = 105, p < 0.001) and the KMO measure of sampling adequacy (0.908) were satisfactory.

Table 4. Loadings of retained items after EFA for the PBS–AGC

a Loadings with absolute values smaller than 0.20 were omitted.

In the validation sample, the CFA revealed eligible results [CFI = 0.958, SRMR = 0.0471, RMSEA = 0.0838, 90% CI for RMSEA = (0.0715, 0.0963), see Figure 3].

Fig. 3. CFA outcome of PBS–AGC.

The five factors were named “new insights,” “more acceptance of limitations,” “more death-related anxiety,” “less influenced by patient deaths,” and “better coping with patient deaths,” respectively.

Psychometric properties of the scale

The Short-term Bereavement Reactions Subscale

Cronbach's alpha for the PBS–SBR subscale and F1 (M = 8.95, SD = 8.04), F2 (M = 3.98, SD = 4.22), F3 (M = 7.37, SD = 4.63), and F4 (M = 3.38, SD = 2.46) among all 538 cases were 0.960, 0.949, 0.923, 0.888, and 0.900, respectively. The split-half reliability was 0.935 (p < 0.001).

Cronbach's alphas for GRAF and ProQOL–Burnout were 0.979 and 0.607, respectively. The PBS–SBR score was the sum of all 17 retained items in the scale. The correlational coefficient between the PBS–SBR score (M = 23.68, SD = 16.98) and the GRAF score (M = 30.55, SD = 37.67) and the ProQOL–Burnout score (M = 17.57, SD = 5.96) was 0.678 (p < 0.001) and 0.333 (p < 0.001), respectively.

The Accumulated Global Changes Subscale

Cronbach's alpha for the PBS–AGC subscale and F1 (M = 11.70, SD = 4.39), F2 (M = 7.40, SD = 3.74), F3 (M = 7.35, SD = 4.61), F4 (M = 3.82, SD = 2.59), and F5 (M = 5.26, SD = 2.47) among all 545 participants were 0.943, 0.917, 0.910, 0.859, 0.949, and 0.948, respectively. The split-half reliability was 0.933 (p < 0.001).

Cronbach's alphas for compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress subscales were 0.949, 0.611, and 0.947, respectively. The correlational coefficient between the PBS–AGC score (M = 35.54, SD = 14.69) and burnout score (M = 18.15, SD = 5.03), compassion satisfaction score (M = 23.39, SD = 1.14), and secondary traumatic stress score (M = 17.33, SD = 10.75) was 0.149 (p < 0.001), 0.562 (p < 0.001), and 0.598 (p < 0.001), respectively.

Discussion

Among more than 500 physicians and nurses in urban hospitals from Mainland China, the present study developed and validated the PBS (full scale in Supplementary Appendix B). Statistics show that both the subscales, namely, the Short-term Bereavement Reactions Subscale and the Accumulated Global Changes Subscale, have satisfactory reliability.

The validity of the two subscales

The validity of PBS–SBR

The PBS–SBR score had a large-sized positive association with the familial bereavement score. As professional bereavement and familial bereavement share the personal dimension conceptually, such a link reflects the satisfactory convergent validity (DeVellis, Reference DeVellis2016) of PBS–SBR.

Participants’ PBS–SBR scores and burnout scores share a medium-sized significant correlation. Among professional caregivers, burnout has been found to link with trauma exposure (Eroglu and Arikan, Reference Eroglu and Arikan2016), omnipotence guilt (Duarte and Pinto-Gouveia, Reference Duarte and Pinto-Gouveia2017), and complicated grief (Anderson, Reference Anderson2008), which are all relevant to certain elements measured in PBS–SBR. Therefore, the significant association between PBS–SBR scores and burnout scores reflects the satisfactory concurrent validity of the latter.

The validity of the PBS–AGC

Participants’ PBS–AGC scores had significant positive correlations with burnout (small effect size), compassion satisfaction (large effect size), and secondary traumatic stress (large effect size) scores.

The concepts of both burnout and long-term changes are based on the accumulated effects of events in professional caregivers’ careers. As the former emphasizes negative outcomes attributed by general events in work while the latter mainly reflects growth lead by patient deaths, the overlap of the two is limited. Therefore, the low correlation revealed the high discriminate validity of PBS–AGC.

Compassion satisfaction reflects participants’ positive feelings relating to their abilities to be effective caregivers (Stamm, Reference Stamm2010). Since the more professional caregivers achieve positive changes in career, the more they may derive pleasure from doing the job well, the high correlation between compassion satisfaction and long-term care shows the satisfactory criterion validity of PBS–AGC.

For the strong positive correlation between secondary traumatic stress and PBS–AGC, insights could be gained from studies on post-traumatic growth: for cancer survivors, the threat of cancer perceived by them is positively linked with their post-traumatic growth (Jim and Jacobsen, Reference Jim and Jacobsen2008), which demonstrates “no pain, no gain.” Moreover, a longitudinal study among bereaved adults unveiled that the positive link between traumatic symptoms and growth exists only when symptoms are at a low to a moderate level (Eisma et al., Reference Eisma, Lenferink and Stroebe2019). According to the cutoff points (Stamm, Reference Stamm2010), 90.5% of the present sample have low to average levels of secondary traumatic stress. Therefore, the strong positive correlation between secondary traumatic stress and PBS–AGC reflects the high criterion validity of the latter.

Clearer distinctions between professional bereavement and familial bereavement

From an event-specific perspective and a global one, respectively, unveiled factorial structures of PBS–SBR and PBS–AGC reinforced the key distinction between professional bereavement and familial bereavement.

Regarding short-term reactions, professional caregivers’ average GRAF score (30.55 out of 160) in the present study is much lower than that among families of the deceased (69.78/160 for males and 87.49/160 for females) in Hong Kong (Ho et al., Reference Ho, Chow and Chan2002). This vividly demonstrates how a familial bereavement assessment tool underestimates short-term reaction in professional bereavement by just telling parts of the whole story. On the contrary, the factor structure of PBS–SBR shows the more comprehensive picture by involving both the personal and the professional dimension: “Grief” and “being moved” grasp the personal one while “guilt” reflects the professional one, and “frustration & trauma” lies across the boundary.

In PBS–AGC, four out of the five factors depict growth. Such an idea of “great good can come from great suffering” (Tedeschi and Calhoun, Reference Tedeschi and Calhoun2004) bears many similarities to the concept of post-traumatic growth (Tedeschi and Calhoun, Reference Tedeschi and Calhoun1996). However, two differences between the long-term changes in professional bereavement and post-traumatic growth after familial bereavement are worth noticing. Firstly, as patient deaths challenge professional caregivers’ “basic assumptions” in not only daily lives but also their careers, PBS–AGC captures deeper insights and corresponding growth in both fields. Secondly, one major long-term change in professional bereavement is that professional caregivers become more at ease with numerous similar patient death events in the future through learning from past experiences (“less influenced by patient deaths” and “better coping with patient deaths” in PBS–AGC). This is seldom the case in familial bereavement, as it is very rare for one individual's several loved ones to die from similar traumatic events at different times.

Significances

The present research yielded the first specific measurement tool for professional bereavement that is clearly defined, comprehensive, rigorously tested, and generalizable to different professional caregivers from various departments. Consisting of two subscales for short-term bereavement reactions and accumulated global changes, respectively, the PBS can measure multidimensional reactions during professional bereavement, and both immediate and accumulated, both event-specific and global impacts are covered. The scale has good content validity, construct validity, and criterion validity, as well as satisfactory internal consistency and split-half reliability. Such a tool enables all studies on professional bereavement that used to be limited by difficulties in a precise and holistic measurement of the phenomenon. Based on the aims and focuses of future assessments, the subscales could be used singly or in combination.

Meanwhile, findings have promoted the clarification of the concept of professional bereavement: from the factorial constructs of both PBS–SBR and PBS–AGC, the existence of a professional dimension in addition to a personal dimension, which is the key to distinguish professional bereavement from familial bereavement, is vividly illustrated.

Limitations

In the present study, only physicians and nurses in urban hospitals are involved, and participants are relatively young. Moreover, owing to limited resources, convenient sampling was adopted so that physicians were underrepresented in the sample. All these might impede the external validity of the findings. Besides, participants’ ratings on short-term reactions to the most recent patient death were based on memory, which might introduce recall bias. Also, the test–retest validity of the tool was unknown.

Future directions

For future studies, it would be ideal to validate such a tool among professional caregivers who work in nursing homes, hospices, or patient homes in different regions of the world. In those studies, the test-rest reliability could be evaluated. Also, future studies could reveal the chronological and causal links between short-term bereavement reactions and long-term changes, identify influencing factors on subscale scores, and explore how the two constructs link with well-beings of professional caregivers and qualities of the service received by patients.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951521000250.

Acknowledgments

The authors show our gratitude to Professor Shuzhen DI from Hebei University of Chinese Medicine for her help in participant recruitment and Professor Danai PAPADATOU from the University of Athens for her comments on the manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared that they have no conflicts of interest to this work.