Introduction

Individual cognitive behavioural therapy for psychosis (CBTp) has proven efficacy as an adjunct to pharmacological interventions for psychosis (Wykes et al. Reference Wykes, Steel, Everitt and Tarrier2008; Burns et al. Reference Burns, Erickson and Brenner2014), it may be an effective alternative (Morrison et al. Reference Morrison, Turkington, Pyle, Spencer, Brabban, Dunn, Christodoulides, Dudley, Chapman, Callcott, Grace, Lumley, Drage, Tully, Irving, Cummings, Byrne, Davies and Hutton2014; NCCMH, 2014) and should be routinely offered to people with a history or current experience of psychosis (NICE, 2014). Routine evaluation of patient and therapist experiences is integral to improving and maintaining CBTp impact and quality (NICE Health and Social Care Directorate, 2014) and continued study particularly within forensic health contexts is warranted to further reinforce and enhance the process of change within CBTp (Steel, Reference Steel2008).

Research into participant experiences has already enabled practitioners to identify and work to resolve barriers to effectiveness. There is a greater appreciation of the centrality of the therapeutic relationship as a result (Messari & Hallam, Reference Messari and Hallam2003; Waller et al. Reference Waller, Garety, Jolley, Fornells-Ambrojo, Kuipers, Onwumere, Woodall and Craig2013). There is a need to foster hope, earn trust, nurture empowerment and be sensitive to divergent frames of reference if therapy is to succeed (Messari & Hallam, Reference Messari and Hallam2003; McGowan et al. Reference McGowan, Lavender and Garety2005; Pitt et al. Reference Pitt, Kilbride, Nothard, Welford and Morrison2007). Therapeutic judgement, skill and the use of self are integral to goal achievement (Waller et al. Reference Waller, Garety, Jolley, Fornells-Ambrojo, Kuipers, Onwumere, Woodall and Craig2013). There is a better understanding of how to enhance the impact of specific therapy components like formulation, homework, psycho-education and social functioning (Dunn et al. Reference Dunn, Morrison and Bentall2002; Miles et al. Reference Miles, Peters and Kuipers2007; Davis et al. Reference Davis, Ringer, Strasburger and Lysaker2008; Morberg Pain et al. Reference Morberg Pain, Chadwick and Abba2008; Kilbride et al. Reference Kilbride, Byrne, Price, Wood, Barratt, Welford and Morrison2013). Encouragingly, the participant voice also suggests that certain CBTp effects may have the potential to generalize across contexts and patient demographics (Miles et al. Reference Miles, Peters and Kuipers2007). Hearing the participant voice has reinforced the importance of core CBTp principles such as genuine collaborative empiricism and the shift from service compliance via compassionate conceptualization of patient priorities (Messari & Hallam, Reference Messari and Hallam2003; Morberg Pain et al. Reference Morberg Pain, Chadwick and Abba2008; Wood et al. Reference Wood, Price, Morrision and Haddock2013). Participants also acknowledge that CBTp has the capacity to rebuild lives (Miles et al. Reference Miles, Peters and Kuipers2007; Pitt et al. Reference Pitt, Kilbride, Nothard, Welford and Morrison2007; Kilbride et al. Reference Kilbride, Byrne, Price, Wood, Barratt, Welford and Morrison2013).

Yet, despite the importance of participant evaluation, research remains limited (Berry & Hayward, Reference Berry and Hayward2011). Aided by Wood et al.’s (Reference Wood, Price, Morrision and Haddock2013) and Berry & Hayward's (Reference Berry and Hayward2011) systematic reviews, we were able to source a number of linked studies from the literature. However, the majority of these only evaluate specific therapy effects or components, involve only community-based samples or adopt methods which may restrict the iterative development and subsequent emergence of implicational meaning among patients with more complex and chronic psychosis histories (Laithwaite & Gumley, Reference Laithwaite and Gumley2007). Indeed, the favoured mode of investigation, the use of interviews to derive data for transcription and subsequent analysis, particularly disadvantages high-security (HS) patients as they are more likely to over-rehearse responses, to self-censor, to provide less reflective responses, to have less developed autobiographical conceptualizations and to have poorer written, spoken and emotional language skills (Laithwaite & Gumley, Reference Laithwaite and Gumley2007). Therefore exploratory application of alternate modes of investigation, particularly in HS health contexts, and further study of participant experiences are warranted.

Chief-complaint orientated CBTp (C-Co CBTp)

Barriers relating to insight, psychological mindedness, adherence and complexity are particularly acute within HS contexts (Laithwaite & Gumley, Reference Laithwaite and Gumley2007). Population and context-specific modes of CBTp delivery are therefore necessary to avoid treatment failure (Bentall & Haddock, Reference Bentall, Haddock, Mercer, Mason, McKeown and McCann2000). A number of case analyses have demonstrated that individual therapy focused on a co-established symptom-based chief-complaint incorporating greater flexibility can address complexity-related therapy barriers, but only with adherent HS patients (Ewers et al. Reference Ewers, Leadley, Kinderman, Mercer, Mason, McKeown and McCann2000; Benn, Reference Benn, Kingdon and Turkington2002; Rogers & Curran, Reference Rogers, Curran, Grant, Mills, Mulhern and Short2004). C-Co CBTp further extends this premise. It theorizes that additional barriers can be addressed with more typical non-adherent HS patients by first focusing therapy on a co-established non-symptom-based chief complaint. This context-specific mode of CBTp offers a gateway to, and platform for, later symptom-based interventions and also substantially increases the likelihood of engagement and subsequent recovery among typical HS patients (Slater, Reference Slater2011).

Aims

The first aim of this study was to use collaborative group game design as part of the routine evaluation of participant experiences of individual C-Co CBTp within HS conditions. The second aim was to evaluate collaborative group game design as a means of evaluating participant experiences within HS contexts.

Research questions

-

(1) What impact does C-Co CBTp have on patient and practitioner participants within a HS context?

-

(2) Is collaborative group game design an advantageous method of evaluating this impact?

Method

Methodology

A qualitative methodology was adopted. Participatory action research (PAR) was the primary mode of study. Elements of grounded theory and thematic analysis were also incorporated and are further explored within the data analysis section. It was felt that qualitative approaches offered a greater potential to perceive the phenomena under investigation, in this instance participant experience of individual C-Co CBTp, with greater depth and richness than quantitative approaches (Bryman, Reference Bryman2012). PAR may be defined as a process in which participants, including the researcher, co-explore and co-develop their understanding of a situation, experience or problem in order to enhance future practice. Its principles and practices of collaboration, democratic ownership and iterative reflection are commensurate with the study ethos of attempting to address disadvantage within the current evaluation literature (Kindon et al. Reference Kindon, Pain and Kesby2007).

Method

Collaborative group game design was used as an innovative PAR method of investigation. Although application in the NHS remained absent, there was growing interest from healthcare professionals, game theorists and game designers to realize similar benefits in health to those achieved elsewhere, particularly in education (Schell, Reference Schell2008; Whitton & Moseley, Reference Whitton and Moseley2012). Reported benefits in education include:

-

• Offering participants the opportunity to reflect on and consolidate linked learning.

-

• Enhancing participants’ abilities to collaborate, communicate and function socially.

-

• Offering participants insights into particular learning experiences.

-

• Developing an accessible format for sharing those experiences thereby facilitating a deeper understanding, enabling consolidation and enrichment of experience and normalization.

-

• Affording a freer level of association and the tapping of implicational as well as propositional experience.

Further benefits may be realized in health. The collaborative nature of group game design parallels the therapy relationship in that it is neither service-user nor service-led. For HS patients in particular, the deeper iterative development of meaning may prove less disadvantageous than interview-based evaluation methods.

Within game design theory there are numerous formats (Schell, Reference Schell2008). It can be advantageous for novice developers to be supplied a format (Whitton & Moseley, Reference Whitton and Moseley2012). A supplied format approach using a ‘Monopoly’-type board game platform was therefore adopted.

Participants

Participants were purposively sampled by the lead author from consenting therapy practitioners and patients who had completed CBTp or were in follow up.

Application

Based on Whitton & Moseley (Reference Whitton and Moseley2012) and Schell (Reference Schell2008), the group adopted a 10-stage sequence to game design (see below). To lessen potential bias, patients and therapy practitioners progressed separately through stages 1–5.

-

(1) Participants initially used a simple questionnaire designed by the lead author to privately reflect on their CBTp experiences.

-

(2) Individuals then chose experiences from their questionnaire responses to share and discuss with the wider group.

-

(3) Participants prioritized experiences to include in the game.

-

(4) Written descriptions and illustrations of experiences were iteratively developed.

-

(5) Game squares were created using the descriptions and illustrations.

-

(6) Patient and therapy practitioner groups were then joined and game squares shared.

-

(7) Squares were then iteratively sequenced into a board game format.

-

(8) Strategies to move around the board reflecting therapy progress were tested and refined incorporating the descriptions for each illustration.

-

(9) All participants were offered the opportunity to play the finished game.

-

(10) Using open feedback cards, participants provided feedback about their experiences of developing and playing the game.

Facilitation

The lead author managed session organization. Sessions were collaboratively facilitated by participants. Process guidance was offered to the therapy practitioner group by the lead psychotherapist (first author), the patient group by the lead psychotherapist and second author, a senior occupational therapist (SOT), and the combined group by the lead psychotherapist and SOT.

Supervision and guidance

The lead psychotherapist and SOT, while supporting each other, also received profession-based supervision as well as guidance from a senior art therapist. Established in 2010 by academics to share and promote game-based research evidence and experiential practice, the Association of Learning Technologies Games and Learning Special Interest Group also guided and favourably reviewed the development of the study approach.

Data and analysis

The study generated the following data: game squares, game play, the game's name and participant feedback. This data lent itself to visual representation and descriptive and thematic analysis. This was initiated by the authors using accepted protocols for each (Boyatzis, Reference Boyatzis1998; Bryman, Reference Bryman2012). An iterative process of respondent validation of descriptions and themes was integral to the analysis (Strauss & Corbin, Reference Strauss and Corbin1998).

Results

General

Participants

Ten patient and five therapy practitioner participants consented to involvement in the study. All patients were male, with only one non-white participant and had an average age of 41 (range 32–50) years. Average length of stay was comparable to that expected pre-discharge (7 years). All but one had index offences of manslaughter and most were diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. All patients were detained with restrictions through either court order (n=6) or Ministry of Justice transfer (n=4). Practitioner participants comprised psychology, nursing and allied professionals at various stages of CBT accreditation (accredited, trainee, non-accredited) and included two females and three males. None of the participants withdrew from the study. Two patient participants only partially attended some sessions due to prior commitments. One patient participant and two practitioners were unable able to attend the first of the combined sessions.

Application

Stages 1–5 were achieved over five sessions with the patient group and two sessions with the practitioner group. Stages 6–10 were achieved over three sessions with the combined group. Practitioner sessions were held in a departmental meeting room. Patient and combined sessions were held in designated ward and central group therapy rooms.

Patient and practitioner experiences of C-Co CBTp

Development of C-Co CBTp game squares

Participants developed 24 game square illustrations (Fig. 1) and matching descriptions. Squares depicted Referral and discharge (n=1), ‘Bridging’ between therapy stages (n=2) and Assessment (n=5), Intervention (n=11), and Relapse prevention (n=5) experiences of therapy. Examples of the types of game squares developed, along with their descriptions, are given in Table 1.

Fig. 1. The ‘Taking Steps’ game.

Table 1. C-Co CBTp game square examples

C-Co CBTp experiences reflected within game square themes

Although a number of patient participants voiced that news of their referral was something that they had not felt prepared for, participants decided to adopt a more service-provider-orientated referral description emphasizing why CBTp was offered. Similarly, some patient and practitioner participants voiced anxieties linked to discharge and follow-up but chose in the description to emphasize the sense of achievement and moving forward that most felt. Patient participants felt the need to stress proving to themselves as well as the multi-disciplinary team (MDT) that they could apply what they had gained during therapy as part of progression towards conditions of lesser security. Participants felt bridging squares were important to reflect their sense of therapy stage transition. Strong themes of fear, anxiety, judgement, trust and relationship building dominated assessment game squares, suggesting that assessment was a particularly vulnerable time for all participants. Commensurate with stage length intervention squares constituted the main bulk of the game. Squares predominantly referenced general impact, impact of specific interventions or a sense of progression. Themes include: journeying away from isolation, of being guided to recovery, of increased self-awareness and insight, of being freed, of developing skills to manage particular experiences and of a nonlinear progression. These generally positive reflections offered a strong contrast to the anxieties of the assessment stage. Relapse prevention squares described the strong sense of achievement at reaching this stage and the hope gained from having a prevention plan.

Insights into C-Co CBTp experiences via game play

Participants developed game-play cards to guide players around the board. Description cards provided the description of the square the player landed on. Bridging cards offered a description of the therapy stage players had progressed to. Movement cards instructed players to move a number of squares backwards or forwards creating a sequential but importantly nonlinear progression linked to the participants’ therapy experiences. Examples are provided in Figure 2. Backward movement cards emphasized mistrust, negative factors within the therapeutic relationship, intervention linked distress, avoidance and increased symptom experiences. Conversely, forward movement cards emphasized working together, trust, sharing, listening, positive risk-taking, trying strategies and seeing them work, giving things a go despite being afraid and the effects of particular interventions like behavioural experiments and evidence gathering. These cards also emphasized the qualities participants felt aided therapy stage transition such as collaborative evaluation and decisions about readiness, co-agreement, openness, positive reinforcement, validation of progress and taking a chance.

Fig. 2. Example of movement cards.

Game size

Participants painted their illustrations onto 0.6 m2 boards. Participants felt the resultant ‘life-size’ 4.2 m2 board game would offer players a more interactive physical journey than a table-top equivalent.

Game name

Participants felt the name ‘Taking Steps’ suggested a proactive undertaking and neatly encapsulated the many different levels of C-Co CBTp experience the game represented. The boards and game play represented the steps participants had taken during therapy as well as those taken to develop the game and to share their experiences. The size of the game board would also mean players physically taking steps along the participants’ journeys.

Collaborative group game design as an evaluation method

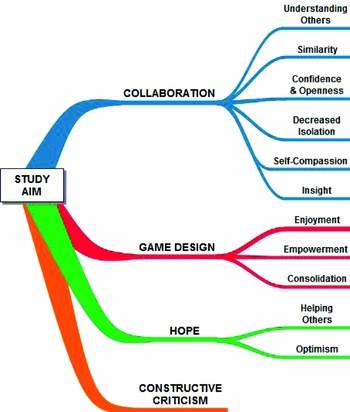

From the feedback card data, 40 incidents relating to collaborative group game design as a method were identified and subsequently coded using a constant-comparative, data-driven mode of emergent analysis (Glaser & Strauss, Reference Glaser and Strauss1967; Glaser, Reference Glaser1992; Boyatzis, Reference Boyatzis1998; Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2006). Four core categories, each with relevant subcategories, emerged (Fig. 3). A tag cloud (Fig. 4) was developed to offer a visual representation of category and subcategory weighting. Dynamic participant and co-facilitator validation informed theme selection (Strauss & Corbin, Reference Strauss and Corbin1998). Discrete incidents are referenced using the prefix ‘i’.

Fig. 3. A tree diagram of identified themes from participant feedback.

Fig. 4. A tag cloud of incident weighting within categories and subcategories.

Collaboration

This was the most heavily weighted emergent core-category incorporating half of all incidents. The title seemed most apt as the emergent subcategories linked to the collaborative ethos the group developed to design the game.

C1. Understanding others: This was the most heavily weighted category within Collaboration and represented the insights participants gained through becoming aware of others experiences.

The group increased my understanding by seeing others’ game squares. (i12)

It helped me see and understand different problems that others had. (i17)

I'm better and more open to understanding other people's experiences. (i20)

I gained a lot from working as a patient/staff team and hearing others. (i9)

I didn't realize practitioners might also be anxious sometimes so reading their explanations and seeing their squares has been helpful. (i27)

C2. Similarity: Participants seemed to recognize similarities between their own and others’ experiences.

I found it good to hear others’ opinions and experiences of CBTp and learn that some of these experiences mirrored my own. (i6)

C3. Confidence and openness: Group members developed greater confidence to share their experiences.

It increased my confidence and lessened my worries about sharing with others the mental experiences I'd usually bottle up. (i18)

C4. Decreased isolation: Participants felt less isolated as a result of collaborating with others.

Hearing others talk about their experiences of CBTp made my own journey feel less isolated. I feel less alone. (i25)

C5. Self-compassion: Collaboration within the group helped some participants to recognize their achievements

The group taught me not to kick myself so much when I've done a good job. (i13)

C6. Insight: Collaborative participation aided insight development.

I gained further insights from being in a CBTp group. (i23)

Game design

This was the second strongest category to emerge from the analysis, this represented experiences that were linked to game design and production.

G1. Enjoyment: A strong subcategory, participants enjoyed using game design to evaluate their experiences.

Producing the boards has been good fun. Using art as a tool to express myself was surprisingly good. (i3)

I enjoyed the challenge of designing a board to reflect my CBTp experience. (i11)

I really enjoyed completing the boards, initially I didn't think it was something I was capable of, but they looked really good. (i26)

It's been challenging to produce the boards and satisfying to see the game come together. (i31)

I've enjoyed converting the different experiences into pictures and seeing all the boards come together. (i36)

G2. Empowerment: Several participants felt game design enabled them to share their experiences in a way they had been unable to before.

The group reinforced my CBTp gains by using a different technique to allow me to share my fears and thoughts. (i5)

G3. Consolidation: Participants also felt that game design helped to consolidate therapy gains.

I felt the group reflected perfectly and helped consolidate what I have done in CBTp. (i33)

Hope

A strong sense of hope emerged from the feedback with many incidents including derivatives of the word hope.

H1. Helping others: This was a strong subcategory and represented the hopes participants held that playing the game might equally help others.

I hope experiencing Taking Steps might encourage others to take a risk and share their experiences so that they can also learn ways of challenging them, particularly voices. (i28)

I would recommend other people who have done or are likely to do CBTp to have a go at something like Taking Steps and hopefully gain the same sense of achievement from working with others to achieve it. (i34)

It's an experience that I believe would be beneficial for others and give them confidence to engage in therapy. (i4)

H2. Optimism: As a result of the group participants felt more hopeful about their futures.

I felt that being part of the group represented a step forward in life. (i8)

It reinforced my hopes for the future. (i22)

Constructive criticism

Although only a minor category comprising less than 5% of incidents it felt important to reflect constructive criticisms offered by participants.

I would have preferred more discussion in the group. (i14)

Discussion

C-Co CBTp game squares and descriptions graphically illustrated stage-linked therapy experiences and transitions, while game play offered insights into the nonlinear yet sequential sense of therapy progress participants experienced. Commensurate with other HS observations (Benn, Reference Benn, Kingdon and Turkington2002), referral was not always co-agreed and emphasis on service needs and pleasing the MDT was evident. Assessment was portrayed as a particularly vulnerable stage with strong themes of fear, anxiety and judgement. Interestingly game development made patient participants aware that practitioners might also be vulnerable during this stage. Game-play emphasis on effective relationship building as a means of addressing vulnerability supports similar findings (Messari & Hallam, Reference Messari and Hallam2003; Waller et al. Reference Waller, Garety, Jolley, Fornells-Ambrojo, Kuipers, Onwumere, Woodall and Craig2013) and reinforces the key components of hope, trust, empowerment, proof and sensitivity identified in earlier studies (McGowan et al. Reference McGowan, Lavender and Garety2005; Pitt et al. Reference Pitt, Kilbride, Nothard, Welford and Morrison2007; Morberg Pain et al. Reference Morberg Pain, Chadwick and Abba2008). Collaboration was a particularly strong theme throughout the literature and in this study. Intervention squares portrayed a collaborative journey away from isolation towards recovery and of increased self-awareness, insight and confidence. However, game play also suggested interventions can be distressing and lead to avoidance. Insights into specific therapy contents and techniques particularly the use of behavioural experiments and the development of relapse prevention plans were also evident. The sense of hope relapse prevention plans offered corroborated the capacity of effective CBTp to rebuild lives observed in earlier studies (Miles et al. Reference Miles, Peters and Kuipers2007; Kilbride et al. Reference Kilbride, Byrne, Price, Wood, Barratt, Welford and Morrison2013).

Participant feedback suggests the approach adopted by the study has several important advantages over more traditional methods of investigation. As well as evaluating therapy experiences the approach consolidated and reinforced gains, offered a strong sense of collaboration, understanding and hope and, importantly, empowered disadvantaged participants to share and reflect (Laithwaite & Gumley, Reference Laithwaite and Gumley2007). Via playing ‘Taking Steps’, the approach may also offer non-participants a deeper, experiential means of appreciating therapy experiences. However, there were constructive criticisms from individuals for whom more traditional discursive routes of evaluation may have been better suited.

Strengths

The study offers a novel and seemingly effective approach for investigating psychotherapy experiences. It adds to the current literature exploring experiences of CBTp and in particular the experiences of HS CBTp participants. Novel forms of experiential dissemination may also be possible with approval to invite non-participants to play ‘Taking Steps’.

Limitations

Although a process of respondent validation was used to lessen potential bias, the dual role of the authors as practitioner participants and facilitators might have limited outcomes. The all-male sample and single-site-specific application also preclude generalizability and the low number of negative case examples within the method evaluation themes may reflect participant self-censoring rather than satisfaction with the process per se (Laithwaite & Gumley, Reference Laithwaite and Gumley2007).

Conclusions

A number of important insights emerged from the data regarding the impact of C-Co CBTp on HS patient and practitioner participants. These add to and support the current literature. The rich quality of generated data suggests that participatory action research using collaborative group game design is a viable and advantageous method for evaluating HS participant experiences of C-Co CBTp, although replication is warranted to determine generalization (Bryman, Reference Bryman2012).

A Summary of the main points

-

• Routine evaluation of patient and therapist experiences is integral to improving and maintaining CBTp impact and quality.

-

• Research into participant experiences of CBTp has enabled practitioners to identify and work to resolve barriers to effectiveness, but remains limited. Current modes of investigation may disadvantage HS participants.

-

• Collaborative group game design was used as a novel method of participatory action research to evaluate patient and practitioner experiences of C-Co CBTp, a variant of CBTp used specifically within HS settings.

-

• Participant feedback and the rich quality of generated data suggests the approach is a viable means of evaluating HS participant experiences of C-Co CBTp and has several important advantages over more traditional methods of investigation.

-

• Evident themes included collaboration, hope, nonlinear progression, difficulty, empowerment, optimism and insight.

-

• Outcomes both support and importantly add to the existing literature and further reinforce the inference that the effects of CBTp may be generalizable across contexts and demographics.

Ethical standards

In order to help categorize the study, the authors completed the Health Research Authority Decision Tool and consulted visiting National Research Ethics Service personnel prior to commencing the group (National Research Ethics Service, 2013; Health Research Authority, 2014). Outcomes suggested the study should be categorized as service evaluation involving standard clinical practice. A formal review of the proposed study by the local Research and Ethics Governance group and Trust lead supported this categorization. Commensurate guidance, support and permissions were sought and gained.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr Townend and Dr Brannigan, members of the Association of Learning Technologies Games and Learning Special Interest Group for their guidance and support and most importantly the participants themselves.

Declaration of Interest

None.

Learning objectives

-

(1) To gain an awareness of the current literature relating to participant experiences of individual cognitive behavioural therapy for psychosis (CBTp).

-

(2) To develop an awareness of participatory action research as an advantageous means of evaluating patient and practitioner experiences of individual CBTp.

-

(3) To explore the application in a healthcare context of collaborative group game design as an innovative participatory action research method.

-

(4) To gain an increased understanding of participant experiences of individual CBTp in high-security conditions.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.