Introduction

Allergic rhinitis represents an inflammatory disorder of the nasal mucosa caused by an immunoglobulin E mediated response to allergen exposure.Reference Papadopoulos, Bernstein, Demoly, Dykewicz, Fokkens and Hellings1 It is a common problem in both childhood, adolescence and adult life,Reference Asher, Montefort, Bjorkston, Lai, Strachan and Weiland2 with a negative impact on patient quality of life (QoL).Reference Bousquet, Demoly, Devillier, Mesbah and Bousquet3–Reference Bousquet, Van Cauwenberge and Khaltaev6 The prevalence of allergic rhinitis is approximately 20 to 35 per cent depending on geographic location, with the highest incidence occurring among children.Reference Bauchau and Durham7,Reference Mallol, Crane, Mutius, Odhiambo, Keil and Stewart8 It is considered an outstanding public health problem worldwide.Reference Mallol, Crane, Mutius, Odhiambo, Keil and Stewart8

Since the 1990s, there has been an increasing trend towards assessing the impact of allergic rhinitis on patients’ QoL.Reference Meltzer9 During the last few years, the evaluation of allergic rhinitis has been considered an important subject in clinical investigation as well as being important for monitoring the effectiveness of a specific treatment in disease management.Reference Speth, Hoehle, Phillips, Caradonna, Gray and Sedaghat10–Reference Thompson, Juniper and Meltzer12

Many factors are involved in health-related QoL, and a variety of validated and standardised questionnaires have been developed. These questionnaires can be classified as either generic or specific.Reference Meltzer13–Reference Leong, Yeak, Saurajen, Mok, Earnest and Siow16 Generic QoL instruments are applicable to all individuals and allow comparison of the burden of illness across different medical conditions. They can be used for any health condition and may evaluate an entire population's well-being.Reference Juniper14–Reference Leong, Yeak, Saurajen, Mok, Earnest and Siow16 As generic profiles are broad and comprehensive, they may lack the detail to be responsive to small but significant changes in patients’ QoL as a result of a specific disease. Disease-specific health-related QoL questionnaires concentrate on aspects of health-related QoL that are most relevant to the disease and are more responsive to changes in the particular disease-related aspect of the patients’ lives.Reference Petersen, Kronborg, Gyrd-Hansen, Dahl, Larsen and Løwenstein15–Reference Juniper, Thompson, Ferrie and Roberts19 The main disadvantage of specific instruments is that they cannot be used to compare the QoL across different diseases and patient types.

Specific health-related QoL questionnaires for allergic rhinitis include the Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire and its shorter, modified version (the Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire).Reference Juniper and Guyatt17–Reference Juniper, Thompson, Ferrie and Roberts19 The Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire is a widely used and validated instrument.Reference Juniper and Guyatt17 It was developed according to previously established principlesReference Kirshner and Guyatt20 and methodsReference Guyatt, Bombardier and Tugwell21 which have proved successful in the development of instruments for chronic diseases.Reference Juniper and Guyatt17 The questionnaire is reproducible when the clinical state is stable, responds to clinically important changes even if those changes are small and is relatively short in order to optimise cost and efficiency.Reference Juniper and Guyatt17 The Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL QuestionnaireReference Juniper, Thompson, Ferrie and Roberts19 is a self-administered, validated rhinoconjunctivitis-specific QoL questionnaire. The Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire includes fewer items; however, it has strong measurement properties and measures the same construct as the original Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire. The choice of questionnaire should depend on the task at hand.Reference Juniper, Thompson, Ferrie and Roberts19

Although both questionnaires have been translated into many languages and are used extensively throughout the world, the adaptation and validation of the Greek versions of Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire and Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire instruments have not been published. Additionally, there are no studies to investigate this topic in the paediatric population. For these reasons, the utility of child self-reports has long been an area of debate in clinical research,Reference Riley22 and historically most health-related QoL measures have relied on parent or proxy reporting.Reference Theunissen, Vogels, Koopman, Verrips, Zwinderman and Verloove-Vanhorick23,Reference Upton, Lawford and Eiser24 Although children can be capable self-reporters, the use of instruments that are not validated for use in children may limit the strength of any conclusions drawn. This is the reason why most authors who have administered non-validated health-related QoL instruments to children have also acknowledged the limitations of their methodologies.Reference Wong, Piraquive, Troiano, Sulibhavi, Grundfast and Levi25

Accordingly, the aims of the present study were to develop the Greek versions of Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire and Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire for clinical and research purposes (even for the paediatric population), discuss their differences, evaluate their psychometric characteristics, and assess the impact of allergic rhinitis on QoL and psychological status related to age (children, adolescents and adults), gender and changes following treatment.

Materials and methods

Ninety-eight patients (40 males (40.8 per cent) and 58 females (59.2 per cent); mean age, 31.66 ± 15.23 years; range, 9–79 years) suffering from allergic rhinitis were enrolled in this prospective study. All patients were recruited from the University Department of Otorhinolaryngology in Alexandroupolis.

The diagnosis of allergic rhinitis was based on medical history, clinical examination and confirmed by positive skin prick test results. All patients fulfilled the criteria of allergic rhinitis according to the 2008 Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma guidelines.Reference Bousquet, Khaltaev, Cruz, Denburg, Fokkens and Togias26 Exclusion criteria were: forms of rhinitis other than allergic rhinitis (chronic rhinosinusitis, cystic fibrosis, any malignancy or any other disease), cognitive disorders and psychiatric diseases. Additionally, patients with a history of anaphylaxis or angioedema and dermographism and recent use of oral or nasal corticosteroids for four weeks prior to inclusion and oral antihistamines for one week prior to the skin prick test were also excluded.

Skin prick tests were carried out in the rhinology unit of the department, according to the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology recommendations.Reference Dreborg27 We used allergens that are the most commonly found in the study area:Reference Katotomichelakis, Nikolaidis, Makris, Zhang, Aggelides and Constantinidis28,Reference Katotomichelakis, Nikolaidis, Makris, Proimos, Aggelides and Constantinidis29 Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus and farinae, mixed grasses, Olea europaea, c1upressaceae family, pinaceae family, parietaria, animal (cat and dog) epithelia, and alternaria and cladosporium molds. The skin prick test was performed by applying a drop of each allergen extract on the skin of the forearm aspect, and evaluations were made 20 minutes after application. Skin prick test evaluation was made according to the method used by Demoly et al.Reference Demoly, Piette, Bousquet, Adkinson, Yunginger and Busse30 We used the allergen panel from Sublivac®. Allergic rhinitis patients were treated with 20 mgr (bilastine) caps once daily per os and nasal spray (fluticasone propionate and azelastine hydrochloride) once into each nostril 2 times per day for 3 months.

Symptom evaluation was made using the Total 5 Symptoms Score, which includes the symptoms of nasal discharge (rhinorrhoea), nasal congestion, itchy nose, sneezing and itchy eyes; the first evaluation was performed when the patients reported exacerbated symptoms. All symptoms were graded from 0 (absent) to 3 (very troublesome), with total scores ranging from 0 to 15.Reference Bousquet, Anto, Demoly, Schünemann, Togias and Akdis31 Total 5 Symptoms Score was evaluated at baseline, three weeks and three months after treatment.

All patients suffering from allergic rhinitis completed four paper-and-pencil generic questionnaires: two generic questionnaires (Short Form-36 Health Survey and Beck Depression Inventory) and two disease-specific questionnaires (Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire and Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire).

In order to evaluate patients’ well-being in relation to allergic rhinitis, a disease-specific questionnaire, the Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire (according to Juniper & GuyattReference Juniper and Guyatt17) in its Greek form was used. The patients filled in the questionnaires at three time points: at baseline and at three weeks and three months after treatment.

The Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire is one of the most widely used and validated disease-specific questionnaires. It consists of 28 questions, which made up the final evaluation, and were divided into 7 subgroups: (activity limitations, sleep impairment, non-hay fever symptoms, practical problems, nasal and eye symptoms and emotional problems). The evaluation was on a scale from zero (non-existent) to six (maximum). The overall QoL was calculated from the mean values of the 28 symptoms.Reference Juniper and Guyatt17 We also used its shorter modified version, the Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL QuestionnaireReference Juniper, Thompson, Ferrie and Roberts19 which is a self-administered, validated rhinoconjunctivitis-specific QoL questionnaire. It has 14 items in 5 domains (activity limitations, practical problems, nose, eye and other symptoms). Each item is scored for the preceding week on a scale from zero (not troubled) to six (extremely troubled). The overall and domain specific scores are, respectively, the mean of all scores or all domain scores. The process of adapting and validating the aforementioned questionnaires has to be completed in three phases, according to the guidelines for cross-cultural validation proposed by Guillemin et al.Reference Guillemin, Bombardier and Beaton32 During the first phase, translation of the English language to the Greek language was completed by two independent certified translators. In the second phase after linguistic negotiation, the Greek language questionnaire was translated back to English. The Greek questionnaire was pilot-tested in a group of patients, and finally it was given to the study population to fill in.

For comparison, other validated and widely used but general psychometric instruments were used (Short Form-36 Health Survey and Beck Depression Inventory) at baseline and three weeks later. The Short Form-36 Health Survey explores QoL in eight domains.Reference Ware and Spilker33,Reference Pappa, Kontodimopoulos and Niakas34 Higher scores indicate a lower impact of disease and better overall health. The Beck Depression Inventory constitutes an instrument for patients’ mood. The Beck Depression Inventory is used to measure depression, and its scores range from 0 to 63 points, with higher scores indicating more severe depression.Reference Hautzinger, Bailer, Worall and Keller35 The study protocol was approved by the University Hospital Scientific Committee. All patients were volunteers and the purpose, design and clinical use of the study was explained to them. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Hong Kong.

We used SPSS® (version 19.0) statistical software to perform the statistical analysis of the data. All quantitative variables were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), whereas qualitative variables were expressed as frequencies (and percentages). The normality of quantitative variables was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The internal consistency of the questionnaires and their subscales was assessed using Cronbach's alpha coefficient. The test–retest reliability was analysed using the intraclass correlation coefficient, Pearson's r correlation coefficient and paired samples t-test in the subgroup of patients, who were re-examined and had reported no change to symptoms during the period that had elapsed. The convergent validity of the questionnaires and its subscales was assessed by correlating their scores with other well-established psychometric tests using the Pearson's r coefficient of correlation. The discriminative validity was evaluated by assessing the treatment response in total and domain scores of the Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire and Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire, and in Total 5 Symptoms Score between baseline and three months after treatment using paired samples t-tests. The relation of the questionnaire scores to patients’ gender and age was also examined by employing Student's t-test and Pearson's r correlation coefficient, respectively. Moreover, the comparison of treatment response according to patients’ gender and age was assessed using Student's t-test, analysis of variance and the chi-square test. In all cases, non-parametric tests used for analysis markedly deviated from the normal distribution of quantitative variables (such as Beck Depression Inventory). All tests were two-tailed and statistical significance was considered for p-values less than 0.05.

Results

The internal consistency of the Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire and Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire were high. The Cronbach's alpha coefficient was 0.92 for the overall Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire: 0.91 for sleep, 0.95 for non-hay fever symptoms, 0.86 for practical problems, 0.88 for nasal symptoms, 0.94 for eye symptoms, 0.90 for activities and 0.95 for the emotion domain. Regarding the Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire, the Cronbach's alpha coefficient was 0.94 for the overall Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire: 0.93 for activity limitations, 0.87 for practical problems, 0.90 for nose symptoms, 0.91 for eye symptoms and 0.96 for other symptoms.

Test–retest reliability was calculated based on the results of all patients (interval at three weeks between the two measurements and patients had no knowledge of or access to their original answers; Table 1). We found no statistically significant differences between the first and second measurement in total Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire and Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire scores (Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire: 2.93 ± 0.85 vs 2.98 ± 0.87, p = 0.082; Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire: 2.90 ± 1.13 vs 2.89 ± 1.1, p = 0.830). Scores of all domains of the two questionnaires were also similar between the first and second measurement (all p > 0.05; Table 1). Moreover, correlation analysis showed an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.976 (p < 0.001) for total Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire and 0.924 (p < 0.001) for total Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire scores; Pearson's product-moment correlation coefficient was 0.953 (p < 0.001) for total Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire score and 0.859 (p < 0.001) for total Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire score. Intraclass and Pearson's correlation coefficients for all domains of the two questionnaires were also very high (Table 2).

Table 1. Test–retest reliability: comparison of Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire and Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire total and domain scores between two measurements

SD = standard deviation; QoL = quality of life

Table 2. Test–retest reliability of the Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire and Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire

Results of correlation analysis of the Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire and Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire total and domain scores between two measurements. QoL = quality of life

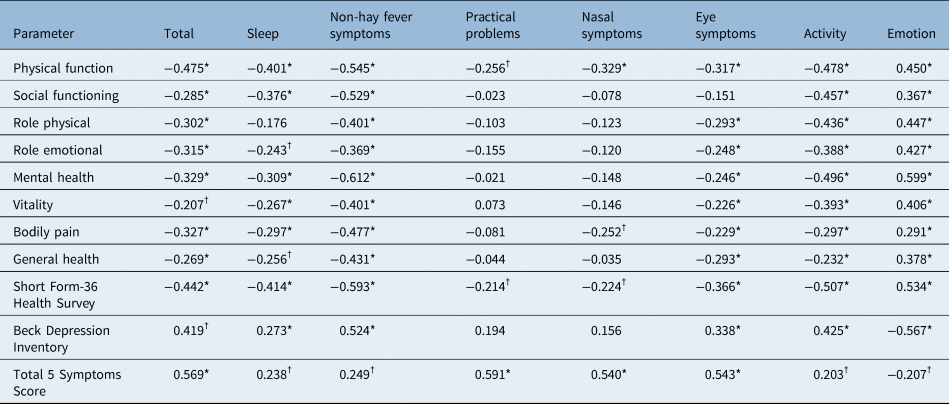

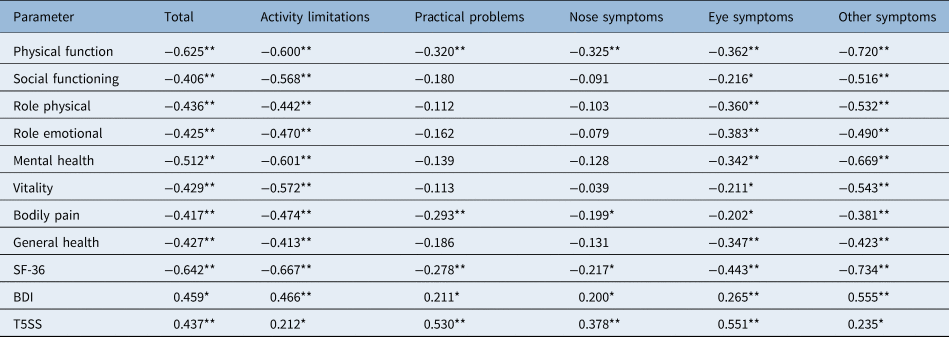

Convergent and discriminant validityReference Van Oene, van Reij, Sprangers and Fokkens36 were both performed to explore validity. Convergent validity of Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire and Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire and their domains was evaluated by correlating their scores with other psychometric instruments (Short Form-36 Health Survey and its subscales, Beck Depression Inventory, and Total 5 Symptoms Score; Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3. Correlation of Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire with other psychometric tests

*p < 0.01; †p < 0.05. Table shows correlation of Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire with other psychometric tests (Short Form-36 Health Survey, Beck Depression Inventory, Total 5 Symptoms Score) expressed as Pearson's r or Spearman's ρ correlation coefficient. QoL = quality of life

Table 4. Correlation of Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire with other psychometric tests

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. Table shows correlation of Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire with other psychometric tests (Short Form-36 Health Survey, Beck Depression Inventory, Total 5 Symptoms Score) tests expressed as Pearson's r or Spearman's ρ correlation coefficient. QoL = quality of life; SF-36 = Short Form-36 Health Survey; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; T5SS = Total 5 Symptoms Score

Statistically significant negative correlations of total Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire and Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire scores with overall Short Form-36 Health Survey score (Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire: r = −0.442, p < 0.001; Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire: r = −0.642, p < 0.001) and with all subscales of Short Form-36 Health Survey were observed. Overall Short Form-36 Health Survey was statistically significantly correlated with all domains of the Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire and Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire. Moreover, statistically significant positive correlations were observed between Total 5 Symptoms Score and the total score of Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire (r = 0.569, p < 0.001), the total score of the Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire (r = 0.437, p < 0.001) and all the domains of the two questionnaires (all p < 0.05). All correlations are depicted in Tables 3 and 4.

Furthermore, we examined the discriminative validity of the two questionnaires by evaluating the treatment response in total and domain scores of the Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire and Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire, and in Total 5 Symptoms Score between baseline and three months after treatment. All measurements after treatment were statistically significant in improvement for all instruments and all domains (all p < 0.001; Table 5).

Table 5. Total and domain scores for Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire, Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire and Total 5 Symptoms Score between the two measurements

SD = standard deviation; QoL = quality of life

Sex- and age-related differences of the Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire and Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire were also established. Females presented highly significant increased scores in total Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire and Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire (Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire: 3.23 ± 0.78 vs 2.50 ± 0.76, p < 0.001; Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire: 3.27 ± 1.08 vs 2.38 ± 1.08, p < 0.001) and lower Short Form-36 Health Survey scores (67.03 ± 19.78 vs 83.63 ± 13.01, p < 0.001) compared with males. Similarly, females exhibited worse scores in all domains of the two questionnaires (all p < 0.05), with the exception of nasal symptoms of Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire and nose symptoms of the Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire, where the tendency towards higher scores in females did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.058 and p = 0.099, respectively).

Patient age was positively correlated with total scores of Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire (r = 0.219, p = 0.031) and Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire (r = 0.283, p = 0.005), while it was negatively correlated with overall Short Form-36 Health Survey (r = −0.308, p = 0.002). At the 3-month follow up, statistically significant reduction of Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire (2.93 ± 0.85 vs 1.98 ± 0.64, p < 0.001), Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire (2.91 ± 1.13 vs 1.51 ± 0.77, p < 0.001) and Total 5 Symptoms Score (8.50 ± 3.03 vs 3.23 ± 1.75, p < 0.001) was observed. Total 5 Symptoms Score changes were positively correlated with Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire changes (Pearson's r correlation coefficient = 0.366, p < 0.001) but not with Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire changes (r = 0.114, p = 0.263).

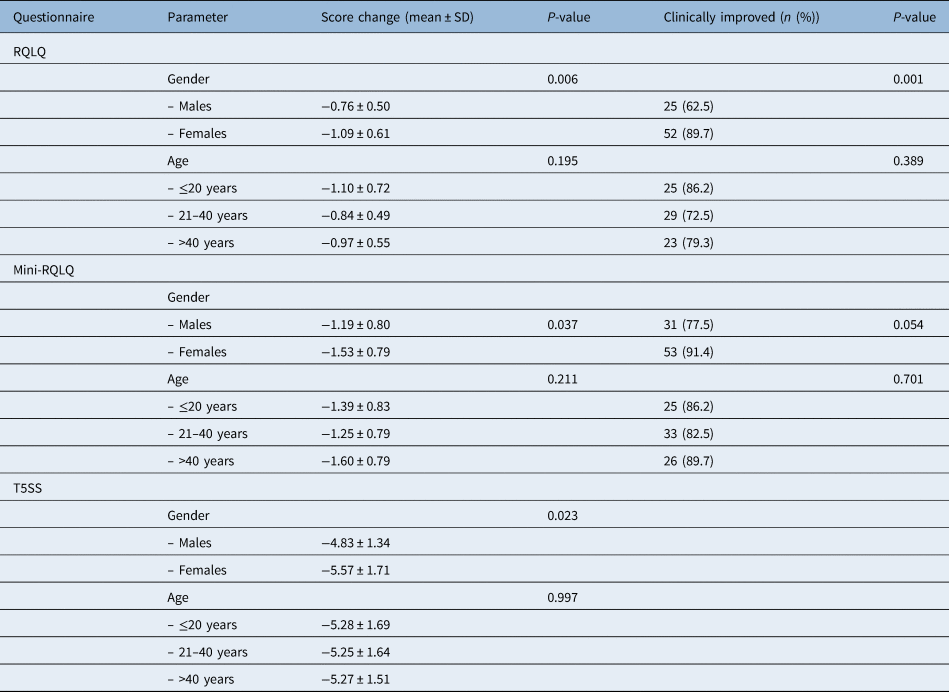

The changes in all questionnaires were significantly greater in females compared with males (Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire, p = 0.006; Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire, p = 0.037; Total 5 Symptoms Score, p = 0.023), but they were not associated with patient age (Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire, p = 0.195; Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire, p = 0.211; Total 5 Symptoms Score, p = 0.997) (Table 6).

Table 6. Change of Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire, Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire and Total 5 Symptoms Score in relation to patient characteristics

Minimal clinically important difference for: (1) Rhinoconjunctivitis Quality of Life Questionnaire (RQLQ), a decrease of 0.425 points, (2) Mini-RQLQ, a decrease of 0.565 points and (3) Total 5 Symptoms Score (T5SS), a decrease of 1.52 points. SD = standard deviation; QoL = quality of life

Additionally, the clinically significant improvement for each questionnaire was defined as a change of more than or equal to 0.5 SDs of the pretreatment score.Reference Dreborg27 Accordingly, improvement was defined as a decrease of 0.425 points for the Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire, 0.565 for the Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire and 1.52 points for Total 5 Symptoms Score. Among the entire cohort, clinically significant improvement was observed in 77 patients (78.6 per cent) for Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire, 84 patients (85.7 per cent) for Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire and in all patients (100.0 per cent) for Total 5 Symptoms Score. The prevalence of a clinically significant improvement of Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire and Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire was higher among females compared with males (Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire, p = 0.001; Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire, p = 0.054, while it was independent of patient age (Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire, p = 0.389; Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire, p = 0.701) (Table 6).

Discussion

This is the first time that the widely used allergic rhinitis questionnaires Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire and its modified short version (Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire) have been validated and adapted for the Greek population, including the paediatric population. We first examined internal consistency reliability of both questionnaires and their domains, and both were found to have high internal consistency reliability. This finding supports the hypothesis that there is a high correlation among questions and a high tendency for items within scales to measure QoL changes related to allergic rhinitis symptoms in both children and adults.

Test–retest reliability for all scores, with an interval of three weeks, showed no statistically significant differences between the first and second measurement in total Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire and Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire scores, suggesting that the Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire and its modified short version have high reproducibility, within all domains of both questionnaires.

We also checked validity, ensuring the ability of the questionnaires to measure what they are supposed to measure.Reference Van Oene, van Reij, Sprangers and Fokkens36 The two different types of validity, convergent and discriminant, were evaluated. We checked the convergent validity of the Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire and Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire and their subscales and checked their scores with other validated and commonly used psychometric instruments (Short Form-36 Health Survey, Beck Depression Inventory, Total 5 Symptoms Score). Additionally, convergent validity is proved when scores of the questionnaire being examined are highly correlated to scores of another questionnaire that measures similar or related concepts, and both QoL questionnaires were proved to be valid. Furthermore, we discovered their discriminant validity to reflect changes in QoL after treatment and found that both questionnaires and their subscales were sensitive in detecting changes in QoL after treatment.

Juniper et al.Reference Juniper, Thompson, Ferrie and Roberts18,Reference Juniper, Thompson, Ferrie and Roberts19 , who validated both questionnaires, gave the first evidence that the Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire and Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire instruments have strong discriminative (cross-sectional) and evaluative (longitudinal) measurement propertiesReference Guyatt, Kirshner and Jaeschke37 and that they can be used with confidence to measure rhinoconjunctivitis QoL in epidemiological surveys, clinical trials and group patient monitoring.Reference Juniper and Guyatt17

After comparison of the Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire and its short version, we found that both instruments were valid and sensitive. However, the internal consistency reliability for the Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire was slightly higher. This may be attributed to the fact that the questions selected for the short version reflect more precisely health-related QoL. Moreover, the clinically significant improvementReference Dreborg27 in our study group was defined as a decrease of 0.425 points for Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire compared with 0.565 for the Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire. Among the entire cohort, clinically significant improvement was observed in 84 patients (85.7 per cent) for the Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire, which is more than the 77 patients with an observation of clinically significant improvement (78.6 per cent) for the Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire. This may be because the least troublesome items were removed from the Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire when developing the Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire; as a result, the Mini-Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire instrument should contain the items that are most responsive to the changes brought about by interventions. This difference in the clinically significant improvement between the two instruments will be important to remember when interpreting the results of clinical trials.

• Allergic rhinitis represents a common problem for children, adolescents and adults, with a negative impact on patients' quality of life (QoL)

• The Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire and its modified short version have been validated and adapted for the Greek population

• For gender, changes in all questionnaires were significantly greater in females compared with males

• Women had significantly better clinical improvement than men in both QoL questionnaires

• The clinically significant improvement in QoL was independent of patient age

• This means that both questionnaires can be used in the paediatric population as well as for adolescents and adults

Finally, we evaluated the influence of age and gender on QoL results after treatment response. We observed that the changes in all questionnaires were significantly greater in females compared with males, and women had significantly better clinical improvement than men in both questionnaires. The changes in all questionnaires were not associated with patients’ age, and accordingly the clinically significant improvement was independent of patients’ age (children, adolescents and adults). To date, there are few studies providing evidence for health-related QoL questionnaires in children and adolescents.Reference Wong, Piraquive, Troiano, Sulibhavi, Grundfast and Levi25 In a review article by Wong et al.,Reference Wong, Piraquive, Troiano, Sulibhavi, Grundfast and Levi25 only five studies were found that recorded health-related outcome measures directly from children. Although children can be capable self-reporters, the use of instruments that are not validated for use in children or enrolling patients who are too young even for validated instruments may limit the strength of any conclusions drawn. In our study, we found no significant differences in children, adolescents and adult populations. This is a very important finding as it proves that both instruments are valid and reliable instruments irrespective of patient age.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we proved for the first time that the Greek versions of the Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire and its short version are reliable and valid methods of exploring health well-being in relation to allergic rhinitis with high specificity and sensitivity for the pediatric population as well as adolescents and adults.

Competing interests

None declared