Anton Giulio Bragaglia and the Italian theatre scene at the start of the Second World War

Irish drama had a decisive role in the Italian theatrical scene during the Second World War. The ambiguous and fluid status of Irish literature allowed Italian intellectuals of different, and often contrasting, aesthetic and political beliefs to negotiate a space for innovation within both Fascist and newly liberated Italy. Drawing on underexplored archival resourcesFootnote 1 and through an analysis of the role of cultural mediators such as Anton Giulio Bragaglia, Lucio Ridenti and Paolo Grassi in the literary field, I investigate a crucial moment of change within both Italian politics and theatre, emphasising strands of continuity between Fascist and post-fascist practices.

I will first establish the importance of Anton Giulio Bragaglia within Italian theatre in the interwar period, emphasising how his role as mediator of foreign theatre in general, and his promotion of Irish theatre in particular, played a key part in restructuring the Italian theatre scene during the transition from Fascist to post-fascist Italy. After the pioneering years of Carlo Linati’s discoverta (1914–1920)Footnote 2 , Irish drama had nearly disappeared from the Italian stage. With the exception of Oscar Wilde and George Bernard Shaw, who were traditionally perceived simply as English, productions of Irish plays in the 1920s and 1930s were rare and generally linked to exceptional circumstances, such as the staging of Lord Dunsany’s Gods of the Mountain by Luigi Pirandello in 1925. From 1939 onwards, however, things started to change. The surprising surge in translations and productions of Irish theatre during the Second World War can be traced directly to a specific alignment of circumstances and, in particular, to the efforts of a small network of literati (including intellectuals, theatre directors, magazine editors, and critics) variously connected to the charismatic figure of Bragaglia. Bragaglia had a long artistic career, spanning futurist photography and Commedia dell’Arte. One of Italy’s first stage directors in the modern sense (Alberti Reference Alberti1974, 37–47), Bragaglia established the Teatro degli Indipendenti in Rome in 1923, which quickly became one of the most successful independent theatres in Fascist Italy. He brought the works of Jarry, Schnitzler, O’Neill and Brecht to Italian audiences, along with numerous emerging Italian playwrights (e.g. Barbaro, De Stefani, and Bacchelli), in keeping with the theatre’s innovative vision. Notwithstanding his numerous productions of Italian plays, and frequent statements on the need to italianise the national stage, Bragaglia was especially interested in discovering new and promising foreign playwrights (Scarpellini Reference Scarpellini1989, 332). He was also aware of the strong appeal of foreign authors for Italian theatregoers, and it was in the light of this conviction that he and Luigi Bonelli organised a hoax during the early years of the Teatro degli Indipendenti. At a time when Russian ballet was very popular both in Europe and Italy, Bonelli himself wrote a few satirical plays under the pseudonym of anti-Bolshevik Russian playwright Wassili Cetoff Sternberg. The plays, performed from 1925, were very successful, and Cetoff was hailed as one of the great playwrights of the time, but little was known about him. It was only at the end of February 1927 that Luigi Bonelli (allegedly Cetoff’s translator) came out onto the stage after the premiere of his L’imperatore and revealed the truth (Alberti et. al 1987, 283-286). This was not to be Bragaglia’s only hoax involving the nationality of playwrights, as we will see in the third section of this article.

Bragaglia’s international renown provided him with a greater degree of freedom during the Fascist period, compared to other uomini di teatro, as was the case, albeit on a larger scale, for Benedetto Croce (Grassi Reference Grassi1962, 343). One of the results of his distinction was that, in 1937, Bragaglia was appointed director of the largely state-funded Teatro delle Arti, in Rome. The Teatro delle Arti occupied a unique position in Italian theatre of the 1930s. Situated in the same building as the Confederazione fascista professionisti e artisti (Fascist Confederation of Professionals and Artists) (Pedullà Reference Pedullà2009, 198), it was neither a commercial nor an experimental theatre; its liminal status translated into a repertoire that mixed orthodox canonical plays with more audacious choices, such as Pietro Aretino’s Cortigiana, which often pushed the boundaries of acceptability and Fascist censorship (Alberti Reference Alberti1974, 290).

The Teatro delle Arti received substantial subsidies from the Duce himself, but despite such patronage, Bragaglia’s choices were quite daring and followed in the footsteps of his innovative Indipendenti productions of the mid-to-late 1920s. In particular, considering the increasing severity of state censorship from the mid-1930s, Teatro delle Arti’s productions featured a surprising number of foreign playwrights and controversial themes. This was made possible both by Bragaglia’s links with the regime and by the theatre’s relatively small capacity (approximately 600 seats). The Arti represented a sort of safety valve for the regime, ‘a fig-leaf of cultural respectability’ (Griffiths Reference Griffiths2005, 80), which granted it a certain reputation for not crushing dissenting or unorthodox voices, and it is certainly telling that their productions did not enjoy the same freedom when touring Italy (Zurlo Reference Zurlo1952, 330), particularly from June 1940 onwards. If the creation of the Commissione per la bonifica libraria (variously translated as Commission for Book Reclamation (Bonsaver Reference Bonsaver2007, 169–187) or Commission for the Purging of Books (Rundle Reference Rundle2010, 170)) that began in 1938 was a defining moment for the book market, June 1940, when Italy entered the war on the side of Nazi Germany, marked an equivalent watershed for Italian theatre. On 6 June 1940, the Italian Copyright Agency (SIAE) circulated an order prohibiting English and French ‘opera lirica, drammatica, operetta, rivista, composizione musicale’ (opera, play, operetta, revue, musical composition) (SIAE, 1940), which, up to that point, had represented a considerable percentage of the works staged and published in Italy.

The reduction in the number of plays by English and French authors was sudden and radical, though the ban did not extend to classic authors such as Shakespeare and Molière and, since the United States had not yet joined the war, Eugene O’Neill, Thornton Wilder, and other successful playwrights were not officially banned. The impact of the regulation was therefore less immediate and pervasive, but the United States’ progressive closeness to the Allied forces meant that theatre managers began to look at ways to sidestep any future difficulties. Moreover, as we will see in the next section, the relative void left by English and French plays would be filled by Irish ones, as their nation was not directly involved in the war. This would have far-reaching consequences both in terms of Italian appreciation of Irish drama and the reform of the Italian theatre scene.

The rediscovery of Irish theatre in wartime Italy

The decision to keep Ireland out of the war was an extremely important moment in Taoiseach (Prime Minister) Eamon De Valera’s development of a foreign policy that would separate Ireland from the United Kingdom once and for all. However, Irish neutrality ‘did not protect Ireland from all the war’s effects’ and it somehow provided her with a ‘strange, ghostly existence … both in and outside the war’ (Wills Reference Wills2008, 5–11). As Clair Wills has shown, Irish literati could not avoid getting involved in, and reflecting upon, the Second World War, and this section will focus on how the translation of their works abroad contributed to that process. With Italy joining the war, Irish literature was in a very convenient position to gain access to Italian territory: it could be staged safely, because Ireland had not officially joined the Allies’ side, and was widely recognised as an alternative to both British and, later, North-American literature (Bigazzi Reference Bigazzi2004, 9). As we will see, Irish neutrality also indirectly confirmed the narrower image of the country constructed by Italian nationalist narratives: Ireland was a simple, monological entity, a rural Catholic country opposed to the plutocratic perfidious Albion, and friendly to Fascist Italy.

Irish playwrights were undergoing something of a rediscovery after so many years of almost total absence from the Italian stage. Works by Yeats, Synge, Lord Dunsany, Shaw, Wilde, O’Casey, Robinson and Carroll were translated for the first time or republished, and often staged by some of Italy’s leading companies, including Emma Gramatica’s, and in important venues such as the Quirino and Eliseo in Rome, and the Manzoni in Milan. In the meantime, Linati was apparently asked by Enzo Ferrieri (at this stage working for the public service broadcaster) to ‘unearth some unknown Irish play’ (Ferrieri Archive, Centro Manoscritti, Pavia, [FACM], Correspondence, folder 58, item 110]. This was particularly common along the Rome-Turin axis that connected Bragaglia and Lucio Ridenti, editor of Il Dramma, a Turin-based popular magazine that specialised in publishing scripts (which were highly sought after by amateur theatre companies) and theatre news. Neither Bragaglia nor Ridenti had ever shown any keen interest in Irish theatre. It is particularly surprising, then, that between December 1939 and December 1943, Il Dramma published 24 Irish plays, and almost as many English or American plays presented as Irish, as we will see in the following section, while Bragaglia produced several of them at the Teatro delle Arti. These two facts are closely related, not only because of the strong longstanding collaboration between Ridenti and Bragaglia, but also because plays that were translated and performed at the Teatro delle Arti were almost invariably published in Il Dramma shortly afterwards. Bragaglia’s deep involvement in Ridenti’s editorial choices is confirmed by their correspondence, archived at the Centro Studi del Teatro Stabile in Turin, in the Ridenti Archive (RA) (Perrelli Reference Perrelli2018), although the former never had an official role on the magazine. What is certain, though, is that Il Dramma heavily relied on Bragaglia’s supply of freshly translated scripts to flesh out its pages, which suffered from a paucity of plays in wartime. I will now consider the extent to which this surge in interest was provoked by a genuine appreciation of Irish theatre, and the impact it had both on the future of Irish drama in Italy and on the Italian theatre scene.

An analysis of the pages of Il Dramma immediately confirms the extent to which the surge in translations (and productions) was linked to the Italian regime’s recent decision to join the war. The very first issue of Il Dramma published after 10 June 1940 featured a clear statement of anti-British sentiment, in the place usually reserved for op-eds. The column was surmounted by a pencil outline of George Bernard Shaw’s face and featured a rather blunt criticism of English people as devious and rapacious:

THE ENGLISH are a race apart. WHEN HE [the Englishman] WANTS A THING, HE NEVER TELLS HIMSELF THAT HE WANTS IT. … As the great champion of freedom and national independence, he fights wars with half the world and annexes it, and calls it colonisation. (Shaw Reference Shaw1975, 205)

Although the connotation is altered slightly in the Italian version (e.g. ‘a race apart’ becomes ‘una razza curiosa’, ‘a curious race’), the text is taken from Shaw’s The Man of Destiny. The anti-British barb was originally (that is, in the 1897 play) uttered by Napoleon, and constituted the climax of the comedy. It was, of course, particularly convenient for pro-fascist propagandists to have such an anti-British statement attributed to one of Britain’s most renowned playwrights. Shaw’s Irishness is not the crucial aspect here, as his being a subject of the British Empire was equally effective from a propagandist point of view. This is indirectly confirmed by the following issues of the magazine, which included, in the same location, similar criticisms attributed to British writers such as Lord Byron and Aldous Huxley, as well as prominent Italian writers such as Alfredo Oriani and Gabriele d’Annunzio. This strategy is similar to that adopted around the same time by the likes of Luigi Villari, Franco Ciarlantini, Nicola Pascazio, Amy Bernardy and other Fascist propagandists, and involved showing the British Empire as profoundly divided, and harshly criticised by its own subjects. In these publications, anti-British criticism was often coupled with a pro-Irish stance; Ireland was perceived as the thorn in Britain’s side, and her absence from the war, though legitimate, was seen as bordering on treason (Wills Reference Wills2008, 7). Ridenti was exceptionally quick to align his magazine with the regime’s official stance. The publication of Irish scripts soon followed; two plays by Synge featured in the following issue and in the October issue, and two by Wilde were published in September. Around the same time, Bragaglia was planning Teatro delle Arti’s 1940–1941 season, and made sure to include as many safe plays as possible in the pre-programme, including two Irish scripts: Synge’s Riders to the Sea, for the second year in a row, and The White Steed by Paul Vincent Carroll. This did not, however, constitute an increase on the 1939–1940 season, which had included Synge’s play and Sean O’Casey’s Juno and the Paycock. Should we then conclude that Bragaglia’s interest in Irish theatre had arisen independently of the Fascist ban on British plays? This is partially true. Synge’s folkloric tones and ‘gritty realism’ (Linati Reference Linati1932, 43) certainly appealed to Bragaglia, who had frequently staged adaptations of the works of Giovanni Verga, the Italian writer most often compared to Synge at the time (Pellizzi Reference Pellizzi1934, 283) and had been a sincere admirer of Eugene O’Neill since the Indipendenti period. Nonetheless, private correspondence demonstrates that concerns over the nationality of playwrights predated the June 1940 SIAE circular. Bragaglia’s dependence on the regime for subsidies – up to one million lire per year, according to Alberti (Reference Alberti1974, 361) – cannot be overstated. He was always keen to have Mussolini’s approval and made sure that the Duce bought two season tickets each year for his theatre as a form of endorsement. Indeed, one of the countless invitations Bragaglia sent to Mussolini sheds some light on the exceptional status enjoyed by Irish theatre in Italy from the start of the war. The letter, dated 16 January 1940 (six months before the official ban), lists the plays that Bragaglia wanted Mussolini to attend. One line, referring to J.M. Synge’s play Riders to the Sea, is particularly significant: ‘Cavalcata al mare di Singe [sic] (irlandese)’ (Alberti Reference Alberti1974, 295). Bragaglia’s zeal in indicating the nationality of the playwright is quite surprising at this stage, and shows, perhaps, that even his early interest in Irish theatre had at least been inspired by political considerations, and was meant as a not-too-subtle ruse to continue producing foreign plays without breaking either explicit or tacit rules.

Whatever the motivation, these choices prompted two closely related effects: a wider recognition of the specificity of Irish literature in Italy, and a subsequent expansion of the Irish canon, as we will see. In order to appreciate this, it is instructive to look at the statistics put together by the SIAE itself in the years both leading up to and during the Second World War. These statistics, published in the yearly publication Lo spettacolo in Italia, provide interesting information concerning the number of shows performed in Italy (theatre, music, cinema) and their revenue, broken down by region, along with the percentage of foreign shows divided by country of origin (Società Italiana degli Autori ed Editori 1939, 46; 1940, 41-42; 1941, 35-36; 1942, 31). Despite being effectively independent since the early 1920s, Ireland was still not included in these statistics as a separate country until 1940: (Table 1).

Table 1 Data based on SIAE, Lo spettacolo in Italia (1939–1942)

This table details the number of shows of Irish and English plays (‘teatro di prosa’, that is, excluding opera and revue) staged in Italy in the period 1939–1942. The figures relating to plays written by English authors remain high because classic writers such as Shakespeare were not banned; some works were tolerated by the censor, meanwhile, because they were either innocuous or showed the enemy in a bad light (Scarpellini Reference Scarpellini1989, 299–300). The presence of Irish literature, however, is remarkable. In 1939 there is no entry for Irish plays and Ireland is only considered relevant for statistical purposes from 1940 onward. Moreover, the number of productions of Irish plays continues to grow, while that of English plays decreases. As alluded to above, this represents a belated acknowledgment on the part of the SIAE of Irish independence, but one which is strongly linked to the country’s neutrality in the Second World War rather than any actual appreciation of its cultural status. It is nonetheless an official recognition of sorts, the first in the field of literature: the Italian literary system had never been more widely aware of the existence of Irish literature as a specific tradition within the Anglosphere. The figures also reveal another interesting fact: the Irish plays were almost exclusively staged by the so-called ‘compagnie primarie’ (Pedullà Reference Pedullà2009, 132–136). These were prominent companies that received a larger proportion of state funds in accordance with the recent Italian theatre reform, which had given rise to the birth of the Ispettorato del teatro (Theatre Inspectorate), the first centralised body to govern key aspects of theatre life in the country, including overseeing censorship, ‘the modernisation of antiquated theatre buildings’ and the ‘formation of new companies’ (Thompson Reference Thompson1996, 103). As of 1935, then, companies that had ‘valore nazionale’ (nationally recognised companies) and privileged national playwrights were officially considered ‘compagnie primarie’. The initiative was perfectly in line with the autarchic policy of the Fascist regime. The small group of primary companies (only 22 in the 1936/1937 season) was therefore subject to tighter control than the so-called ‘secondary companies’ (approximately 150 in the same year) and was granted access to more prestigious venues, such as the ones mentioned above where Irish plays were more often produced.

This relatively new system of funding had crucial consequences for the development of Italian theatre, but one of its side-effects was that it contributed to the recognition of Ireland as one of the main centres of theatre activity in Europe. This Ireland was, once again, a substitute for England: it appeared on Italian (political and literary) maps mostly thanks to its anti-English function. The reception of Irish drama in Italy maintained its traditional link with Irish politics, although with a subtle difference: the political character of Irish plays that had interested Carlo Linati and Mario Borsa at the start of the century was now almost exclusively attached to Irish playwrights because of the politics of their country of origin rather than to their works. Moreover, many writers were considered Irish that had not been regarded as such over the previous decades, in particular Shaw and Wilde. Around the same time, theatre magazines, such as Il Dramma and Scenario, regularly ran features on Irish drama. The elasticity of the Anglo-Irish canon was a constitutive aspect of the revival presented in these articles, which was mainly the product of a political ruse, but that effectively challenged the borders of Anglo-Irish literature itself. Ireland’s neutrality in the war proved to be a difficult legacy for the country, but as far as Italy was concerned, it brought about a wider recognition of Irish cultural specificity. This, however, gives rise to a number of questions. Which Ireland was now being presented to Italian theatre-goers? How did the canon of Irish literature evolve in Italy during the war and what were the consequences for the Italian scene? An examination of both the translations and discourses surrounding Irish theatre in magazines will therefore be particularly instructive.

The oriundi and the new Irish canon of O’Bragaglia

In 1940 and 1941, Il Dramma published plays by Synge, Wilde, Yeats and Joyce. If we consider them in relation to other foreign plays, the numbers are overwhelming, with almost one in two being Irish. The source of the translations is also quite telling: they are almost invariably attributed to Carlo Linati, and are those published by him between 1914 and 1920. I will return to that ‘almost’ soon, but in the meantime, it is worth emphasising that this choice, while probably influenced by the ready availability of these translations, was also associated with a strong, and by then traditional, idea of Irish drama as particularly linked to nationalist themes. After the first issues of the summer of 1940, the magazine stopped publishing overtly anti-British propaganda and focused on extolling Irish literature rather than criticising England. By 1943, even Linati’s articles acquired more obvious political tones:

It could be argued that the inexhaustible inventiveness and the generous idealism of the Irish have always somewhat served as the rich reservoir from which English literature has drawn the strength to renew itself in its moments of tiredness or decadence; from Sterne to Wilde, from Swift to Shaw, countless writers, born in Ireland and inebriated with its coarse and tenacious sap, enrichened the old trunk of Anglo-Saxon Literature with new branches. (Linati Reference Linati1943, 50. Translations, unless otherwise stated, are mine)

While consistent with a received idea of Ireland as rural, the naturalistic metaphor is quite surprising as it introduces a relatively rare image (particularly in Linati’s works) of Ireland as masculine and strong, a new force ready to revive the wilted British civilisation. Linati’s rhetoric recalls Fascist propaganda and stresses an implicit link between the regime’s self-image and Irish culture. The image of Ireland that one gathers from Il Dramma in the years of the war is that of a rural, Catholic, masculine and anti-British country. Arguably, the main goal in exalting Irish culture was to undermine Britain’s cultural relevance. In this sense, Ridenti’s magazine was perfectly aligned with the general tendency of Fascist cultural propaganda, as can be perceived in other publications such as Meridiano di Roma, Civiltà fascista and Scenario, to name but a few.

This rapidly gave rise to an extensive translation project. With the help of new mediators, Ridenti and Bragaglia set out to expand the repertoire of Irish literature in Italy and move beyond Linati’s choices. They did so in a way that simultaneously provided them with a wealth of new, legitimate plays and complied with the Fascist policy of undermining the enemies’ cultural status, in a convergence of aims that put both Bragaglia and Ridenti at the forefront of theatrical innovation while maintaining the favour of the regime.

Ridenti, in particular, began by exploring as-yet untranslated texts by known Irish playwrights and then, more timidly, shifted his attention to lesser-known writers. This also entailed widening their circle of translators (e.g. Agar Pampanini, Michaela De Pastrovich and the experienced Alessandra Scalero), and involving new mediators. The main newcomer was Vinicio Marinucci (b. 1916), a future protagonist of Italian cinema and president of the Italian Film Critics Union (Sindacato nazionale giornalisti cinematografici italiani), but at this stage a young and bold theatre and film critic. Marinucci tried to expand the canon of Irish drama in Italy by introducing the public to Lord Dunsany, whose works he also translated, Lennox Robinson, and Paul Vincent Carroll (but tellingly, shying away from the latter’s very successful 1942 play on the Glasgow blitz, The Strings Are False). His initiative was only partially successful. Of the numerous contemporary Irish playwrights he introduced in his 1942 articles (Marinucci Reference Marinucci1942a and Reference Marinucci1942b), very few made it to the stage or even to the pages of Il Dramma. A reason for this can be found in Bragaglia’s dislike for Marinucci, whose desire to gain a more central position in the system of Italian theatre (and in Il Dramma) he strongly opposed (Letter to L. Ridenti, n.d. but early March 1943, RA, Correspondence, item 104), as well as in his growing uneasiness with the political elements of Irish drama: ‘O’Casey and the others have already managed to tire us with Irish patriotism’ (Letter to G. Dauli, 3 May 1943, GDA, Correspondence). Marinucci’s articles confirm one aspect of the reception of Irish theatre in Italy in the first half of the twentieth century: despite its recent relative success, the Italian public was not yet conversant with Irish literature. Critics and scholars never presumed a familiarity with it on the part of their readers, something that is apparent from the relatively lengthy introductory sections preceding most contributions: Irish literature had to be summed up, so to speak, at every occurrence, partly in order to reframe it, and partly in order to account for the relative novelty of the subject. Nonetheless, such rediscovery eventually had a positive outcome for the dissemination of Irish theatre. It was during this period that most Irish plays were produced for the first time and achieved some popular success. While Linati could complain to Facchi that Italian audiences seemed blind to the charm of Synge’s Playboy of the Western World in 1919 (Letter to G. Facchi, 3 March 1919, Linati Archive, Biblioteca di Como [LAC]), the one-act play Riders to the Sea had become a staple of Bragaglia’s repertoire and was frequently staged by amateur companies; some Irish plays were also being aired on national radio by Enzo Ferrieri, a former collaborator of Linati’s. The success of these plays was also demonstrated by the effect they had on a future protagonist of Italian literature: the poet, playwright and filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini. Pasolini’s encounter with Synge was to have a strong impact on the 19-year-old poet and, arguably, on his views on rural dialects. According to Roberto Roversi, Pasolini was so impressed by Synge’s work (read in Il Dramma in 1940) that he staged it with his friends in his parents’ home (Casi Reference Casi2005, 28). Any further exploration of such fascinating relationships is beyond the chronological scope of this study, but such occurrences are nonetheless worth noting as the fruits of what had certainly been a ‘new discovery’ for the Italian public.

This rediscovery was also accompanied by an unusual development, which made the identity of Irish drama, and its national character, a matter of both popular and critical debate. This emerged when the progress of the war made it clear that the regime also regarded American playwrights as enemies. Due to the combined efforts of Ridenti, Bragaglia and Marinucci, English language authors who had hitherto had little or no association with Ireland suddenly began to be presented as Irish. This entailed an even greater expansion of the Irish canon, and was again facilitated by the convergence of interests between these mediators and the regime. For propaganda reasons, American theatre was then presented as a poorer, exclusively commercial version of European theatre; claiming prominent playwrights such as Eugene O’Neill (who had been awarded the Nobel prize in 1936) as Europeans thus responded to an old-world logic whereby Europe stood as a symbol of culture, and the ‘new world’ as the site of mechanisation and ignorance (Alessio Reference Alessio1941). This attitude, of course, became even more pervasive when the US joined the war on the side of the Allied forces.

There were two main routes through which playwrights from enemy countries could be staged in wartime Italy: the first was to be critical of their own country, and therefore potentially instrumental to Fascist propaganda, while the second was to have ‘safe’ ancestors. The former group was very popular, and Bragaglia devoted almost the entire fifth season of his Teatro delle Arti to American proletarian theatre. The latter was more controversial: from the beginning of 1942, after the US officially joined the war, several American playwrights became Irish, allegedly on account of being born to Irish parents. The foreign-born Irish writers (oriundi) included some Irish-Americans such as Eugene O’Neill, George Kelly, and Philip Barry, but also writers whose Irishness was rather more questionable, such as Allan Langdon Martin (pseudonym of the North-American Jane Cowl and Jane Murfin) and Emily Brontë. In these cases too, however, the authors were presented as Irish, while some of their plays were even allegedly ‘translated from the Irish’ (Kelly Reference Kelly1943, 39). The ruse also allowed Bragaglia to dodge payment of staging fees, as the Minister of Popular Culture, Pavolini, had passed a law allowing such fees to be waived when enemy countries were concerned (Scarpellini Reference Scarpellini1989, 297). The lack of any hard evidence – due in part to the inaccessibility of Bragaglia’s archive – makes it very difficult to state with certainty whether the ruse originated in Bragaglia’s theatre, or whether it can in fact be traced back to the Minculpop (Ministry of Popular Culture). Some of Bragaglia’s letters to Ridenti show his efforts to reassure the latter of the legality of publishing O’Neill and the other oriundi, and seem to suggest that the idea for the strategy may have come directly from the government itself. On 25 December 1942, Bragaglia wrote: ‘I saw with my own eyes a memo from the Minister to the Duce, in which it is stated that O’Neill is Irish. When the time comes, we will have to inform the General Director for the Press that the latest version is that he is Irish.’ (A. G. Bragaglia, Letter to L. Ridenti, 25 December 1942, RA, item 81). However, no clear proof of this can be found at the Archivio Centrale dello Stato (Central Archives of the State), where most of the memos and notes are concerned with either clarifying the Irishness of playwrights or their political and/or aesthetic value (Alberti Reference Alberti1974, 295–311; Vigna Reference Vigna2008, 321–363) and the memoirs of the theatre censor Leopoldo Zurlo (Zurlo Reference Zurlo1952, 328–333) are quite vague in this regard.

What first strikes the reader is that the frequent articles published on O’Neill up until the end of 1941 (both in Il Dramma and elsewhere) make no secret of his being an American writer and, most importantly, barely mention his Irishness. This is even more surprising given that Bragaglia and Ridenti had been aware of the special status of Irish Americans at least since the summer of 1941, as is evident from their correspondence. A letter from Bragaglia to Gian Dauli (24 July 1941), for instance, shows that American playwrights were already frowned upon before Pearl Harbour, but that the ban did not apply to Irish-Americans (A. G. Bragaglia to G. Dàuli, 24 July 1941, GDA, Correspondence). Since Italy’s declaration of war on the US, however, O’Neill’s father, the Irish actor Joseph, became a stable presence in his biographies, as proof of his son’s Irishness. While Bragaglia had little trouble with the censor, Leopoldo Zurlo, the ruse was not unanimously accepted, and he received criticism from orthodox Fascist periodicals, which gently mocked him for his loose notion of Irishness. Bertoldo, a satirical magazine, produced a cartoon on the subject in which two theatregoers facetiously argue over O’Neill’s nationality (Quargnolo Reference Quargnolo1982, 98–99), and he was even dubbed O’Bragaglia by the press (Alberti Reference Alberti1974, xxi). While Bragaglia could count on the support of the Minculpop, his actions were still frowned upon by more conformist Fascists, who viewed them as a way to sidestep the ban on enemy writers.

Nonetheless, through publications, paratextual elements and relentless advertising, Bragaglia, Ridenti and the new voices of Il Dramma managed to construct a common narrative in which both they and their intended audience were embedded (Bruner Reference Bruner1991). Since 1940, Il Dramma had insisted on the Irishness of Synge and Yeats in particular, showing a tendency to remind their readers of this ‘new’ phenomenon of Irish theatre in various guises. The magazine was laced with short notes on Irish theatre, reminders of the issues that had included Irish plays, ads directly addressed to amateur theatre companies with details of where they could find the scripts, as well as short reviews. This was common for the magazine, but the extent of the campaign was more pervasive than ever before, as was the zeal with which the nationality of the playwrights was constantly referenced. Indeed, following the publication of a number of plays by O’Neill (including Mourning Becomes Electra and Beyond the Horizon), and the ensuing debates, Il Dramma announced an article by Marinucci, tellingly entitled: ‘Quanti sono questi oriundi irlandesi?’ (How many of these foreign-born Irish are there?) for its 380th issue (15 June 1942). Marinucci had not previously been associated with Irish theatre, but it may be argued that selecting him to deliver the first direct attack was a strategic decision: as a young expert on Irish theatre with no previous strong links to either Bragaglia or Il Dramma, Marinucci could be perceived as a fresh voice contributing to the debate. While the planned provocative title for the article was ultimately dispensed with in favour of the purely denotative ‘Panorama degli oriundi irlandesi’ [Survey of foreign-born Irish], his claims were no less daring. Marinucci’s survey of Irish-American playwrights emphasised that they were not simply Americans with Irish origins, but children of Irish parents ‘who have either emigrated to the US or just happened to be there’ (Marinucci 1942, 30). He showed a certain awareness of the ongoing debate, and stressed that this was a ‘discovery’ not an ‘invention’. These authors were Irish because their parents were Irish, and their Catholic background was still perceptible in their works and the ways in which they opposed American capitalism. Marinucci’s take on Irish theatre was essentially spiritualistic and based on an alleged set of shared values between Irish and Irish-American Catholics: the same set of values that would, in his view, appeal to Italian audiences. His words were a much-needed addition to Bragaglia’s campaign, a strong contribution to the narrative that he and Ridenti were constructing, as we have seen, through various channels and ‘repeated exposure’ (Baker Reference Baker2006, 101–103). Moreover, the construction of an Irish identity for Irish-American playwrights mirrored Fascist reflections on race and nationality. One of the last paragraphs of Marinucci’s article states:

Those who still hesitate to regard the above-mentioned authors as being of genuine Irish stock, should remember that Italy always considers herself the Mother of her foreign-born children. Remember how she ascribes their works among those of her people, and how the characteristics of the country of origin are never extinct in the above-mentioned writers; in America, on the other hand, these same conspicuous characteristics cause authentic Americans to consider such writers almost as foreigners. (Marinucci Reference Marinucci1942a, 31)

In this excerpt, the notion of nationality itself is called into question. The oriundi stratagem, while interesting for the history of Irish and Italian theatre, is equally noteworthy as a reflection of Fascist theories of race and nationality, and Marinucci showed political shrewdness in selectively appropriating and employing such compelling arguments in a moment in which they were becoming even more dominant in the cultural sphere, especially in reference to translations (Rundle Reference Rundle2010, 165–205). Such inclusivity was obviously problematic and controversial, as both the protests and the jokes quoted above demonstrate, but it did tackle a thorny subject: the loose conception of nationality and the essential difficulty in establishing national borders when talking about artistic creations. This issue related not only to playwrights’ nationalities, but also to the theatrical tradition to which they belonged. For instance, while O’Neill was undoubtedly an American playwright and never even visited Ireland, ‘he adopted the Abbey style in one-act form and realistic dialogue’ and ‘had been inspired to become a playwright by the Irish Players from the Abbey in their first [American] tour in 1911’ (Harrington Reference Harrington2016, 598). His European fame was also bolstered by the successful productions of his works at the Abbey where, in 1927 his The Emperor Jones (1920) was one of the first and most influential American plays ‘without obvious Irish context exported from American theatre to the National Theatre of Ireland’ (Harrington Reference Harrington2016, 599). Moreover, in 1932 he had been invited to join the Irish Academy of Letters, which made it possible for Il Dramma to invariably refer to his plays as being penned by an ‘accademico d’Irlanda’ (Member of the Irish Academy) and to stress his Irishness as frequently as possible. As hinted at earlier, this phenomenon was the theatrical equivalent of the anti-English books published during the same period, as it went hand-in-hand with the production of foreign plays whose ‘degenerate morals’ were supposed to strengthen stereotypes concerning their country of origin (Scarpellini Reference Scarpellini1989, 298–299). Both of these discursive strategies were ultimately meant to undermine British and American cultural status. Unsurprisingly, it was also part of Bragaglia’s rhetoric to present such acts as part of a cultural war, as he made clear in a letter to Ridenti: ‘I put on plays as acts of war authorised by the Italian State, at war with America’ (A. G. Bragaglia, Letter to L. Ridenti, 2 February 1942, RA, Correspondence, item 63).

The dissemination of Irish and Irish-American drama in Italy during the Second World War can therefore shed some light on both the politics of cultural transfer in wartime Italy and the fluidity of the Irish canon itself. It is also thanks to the international discourse on the Irish diaspora, which seeped into the Italian literary system, that Italian theatregoers could accept such a number of allegedly Irish playwrights, albeit suspiciously. While all national literatures have essentially porous borders, the Irish canon was, and to some extent still is, a very controversial case, involving not just linguistic and biographical elements, but also thematic issues, political allegiances and conflicting national narratives (Cairns and Richards Reference Cairns and Richards1988). Bragaglia and Ridenti’s activity certainly helped the case of Irish literature in Italy and prompted a conversation about the specificity of Irish literature within the Anglosphere; however, as we will see in the final paragraph, their uncompromising strategy, along with the simplification which accompanied it, led to some confusion in the literary system. Paolo Grassi’s theatre collection would prove how the status of Irish literature in Italy was still unclear, and left significant room for both political and aesthetic manipulation.

Paolo Grassi and Rosa e Ballo: publishing anti-fascist Ireland

In the spring of 1941, Paolo Grassi (b. 1919), a young actor and director, put together a programme of 19 titles with Palcoscenico, an ensemble he had co-founded with fellow-students of the Accademia dei Filodrammatici in Milan and future protagonists of Italian theatre: Giorgio Strelher, Franco Parenti, Mario Feliciani, Aegle Sironi (the painter’s daughter) and others. As Oliviero Ponte di Pino reminds us, Palcoscenico was one of the filiations of Corrente di vita giovanile (1938–1940), the short-lived, but influential anti-fascist literary magazine that had been shut down in 1940. With headquarters at the Sala Sammartini in Milan, Palcoscenico was ‘the only experimental theatre ensemble outside the GUF’ (Ponte di Pino Reference Ponte di Pino2006, 44; the GUF being the Fascist university student association) and had quite an eclectic repertoire, including some Italian plays but mainly consisting of the works of some of the few foreign playwrights permitted by wartime censorship: Yeats, Synge, O’Neill, Chekhov, Evreinov, and Shakespeare. Several factors lay behind such choices. While the group of young intellectuals drawn to Corrente was actively engaged in fighting Fascist rhetoric and aesthetic impositions, their room for manoeuvre was nonetheless limited by the regulations explored above. Despite the relatively small corpus of plays of which performances were permitted during the war, the choices made by Grassi and his acolytes are remarkable: Synge, Yeats, and the oriundo O’Neill play a prominent role, and Grassi’s future career proved that this was not accidental, nor merely the result of the political circumstances affecting theatre at the time. The two Irish plays staged by the Palcoscenico ensemble (Synge’s Riders to the Sea and Yeats’s Cathleen Ni Houlihan) had a certain political significance. Cathleen Ni Houlihan, on the one hand, focused on the story of a country occupied by a despotic regime, and its attempts to rally its sons to subvert it: not only did it have anti-British connotations, it also gave voice to more general rebellious impulses that could easily be interpreted as anti-fascist. Riders to the Sea, on the other hand, did not convey any direct political meaning, but its international production and adaptation history could result in it being regarded as shorthand for anti-fascist theatre: not only was its rhetoric antithetical to the triumphal regime’s mantra, it had also been adapted by the exile Brecht as Die Gewehre der Frau Carrar, in 1937 (Parker Reference Parker2014, 366). The prominence of Synge, Yeats and O’Neill is evidence of the need to constantly negotiate a space for anti-fascist initiatives within the scant room for manoeuvre afforded by wartime Italy. Although histories of Italian theatre have a tendency to privilege rupture over continuity when discussing Fascist and post-fascist practices (Pedullà Reference Pedullà2009, 9–46), demonstrating existing links can help us understand the dynamics of cultural change. It can also facilitate an examination on how well-crafted framing and branding strategies can significantly rearticulate the discourses surrounding a homogeneous, and rather limited, corpus of plays such as that under examination here.

The link between Grassi and contemporary initiatives such as Il Dramma and the Teatro delle Arti was indeed quite strong. Grassi himself acknowledged this link in a letter to Ridenti: ‘I must confess, the Dramma as it was for many years, up until three years ago, was not the magazine for us young people, but recently it has been the only lively organ in Italy.’ (Letter to L. Ridenti, 24 August 1944, Rosa e Ballo Archive, Fondazione Mondadori, Milan, from now on AsReB, Correspondence, folder 5, file 5, item 13). Grassi’s reference to three years before here seems unlikely to be an accident. Up until three years earlier, or rather before 1940, Il Dramma was, in effect, quite a different magazine and held no real appeal for the younger generation; things had changed radically, however, with the start of the war and the attention given to Irish and American playwrights. Grassi’s career was also rapidly changing. Two years after the Palcoscenico experience, he made a name for himself as a theatre critic in Milan. He was then hired by Ferdinando Ballo to be in charge of the drama series of his fledgling publishing house, Rosa e Ballo. The importance of the ‘Collezione Teatro’ edited by Grassi cannot be overstated: its influence was deep and even outlived the publisher that first hosted it, since it was later bought by La Fiaccola, another Milanese publisher. ‘Teatro’ was Grassi’s first attempt at reaching a national audience. As Michele Sisto recently stated (Sisto Reference Sisto2016), it was a way for Grassi to acquire a prominent position in the literary field, by combining anti-fascist stances and breathing life into a theatrical revolution in Italy. In a letter to D’Amico, Grassi states that his aim was to put together scripts that were ‘tangible signs of modern theatre’ and in order to accomplish that, the line-up for the first issues of the series was mainly composed of two separate strands: ‘we will publish the Irish and the German expressionists’ (Letter to S. D’Amico, Christmas 1943, Silvio D’Amico Archive, Museo dell’Attore, Genoa [SDA], Correspondence, folder 5). Of the first 20 issues, eight of the elegant Rosa e Ballo booklets were dedicated to Irish drama, including the likes of Synge (with his entire oeuvre in four volumes), Yeats (two volumes) O’Casey (one) and Joyce (one), which Grassi published in the traditional translations by Carlo Linati, only ever so slightly revised more than 20 years after their first appearance. As with the selections for the Palcoscenico programme, political convenience was certainly on Grassi’s mind,Footnote 3 but this alone could not justify a similar number of Irish works. Moreover, Rosa e Ballo’s catalogue also included Synge’s The Aran Islands (the only work Linati translated for the first time) and other Irish translations were planned. The Rosa e Ballo archive, held at the Fondazione Mondadori in Milan, for instance, contains an unpublished translation of The Importance of Being Earnest (AsReB, Editorial office: folder 13, file 5), as well as evidence of the strong interest shown by Grassi in publishing Eugene O’Neill (AsReB, Correspondence: folder 4, file 8) and Geneva by G. B. Shaw (AsReB, Foreign Rights: folder 17, file 3), an obviously anti-fascist play and therefore one of the very few Shavian works not published by Mondadori during the regime. Moreover, a look at the contracts shows that Linati had also committed to writing ‘30/40 page-long introductions’ to Synge and Yeats (AsReB, Contracts: folder 19, file 10). It is not clear whether the introductions were to constitute separate volumes, but the contracts suggest that this might have been the case, as they are listed as separate entries after the other planned volumes. While these introductions were never written (the longest preface is barely four pages long), this shows a definite commitment to Irish literature.Footnote 4

Focusing on Irish literature sheds light on Grassi’s complex position-taking in a way that problematises the conclusions of earlier scholars who have devoted their attention to the Rosa and Ballo enterprise. Grassi’s aim to include ‘all the best foreign drama produced in the last 50 years’ (Sisto Reference Sisto2016, 74) and to revive Italian theatre does not involve a choice of writers unknown to the Italian public; rather it entails a rebranding of texts with which the public was already at least partly familiar. ‘His main aim was, in fact, not to “discover” new texts and authors, but rather to put together a repertoire of recognized works that would, in turn, ensure him recognition’ (Sisto Reference Sisto2016, 76). Even seen in this light, his choices regarding Irish literature are quite significant. Although several other Irish playwrights were available for publication either through Il Dramma or through their translators, Grassi decided against it. He did not promote Lennox Robinson and Denis Johnston’s Pirandellian drama, nor did he show much interest in Irish mysticism and Orientalism, by dismissing Lord Dunsany. Even with Yeats’s plays, he favoured those in which the political allegory was quite blatant, such as Cathleen Ni Houlihan. He also privileged the expressionist tones of Synge and the bleak political realism of the socialist O’Casey. The choice of contributors was also telling. Along with newcomers such as Guerrieri and others, some of the main exponents of Fascist theatre were asked to contribute (e.g. D’Amico and Bragaglia), testifying to the continuity Grassi aimed to establish with the recent past: without underestimating the importance of his revolution, we can safely say that it was achieved through shrewd reform rather than a clean-cut rupture with the past.

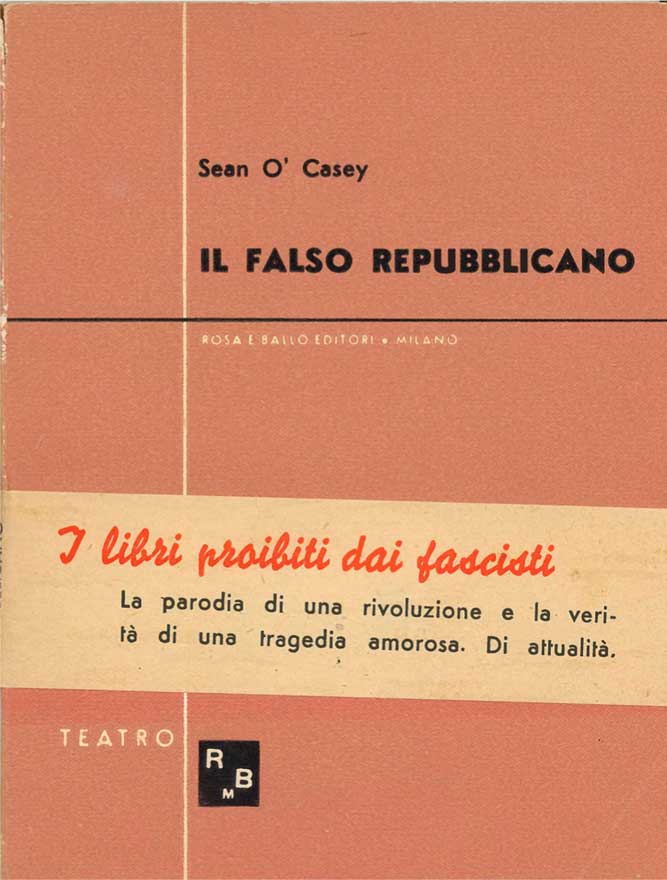

This apparently safe choice of texts, however, was ingeniously reframed as subversive and anti-fascist by Grassi. For instance, despite the fact that all these plays had freely circulated during the Fascist period, O’Casey’s The Shadow of a Gunman (1923), translated as Il falso repubblicano (The False Republican), was published with a surprising and factually inaccurate blurb, stating that it belonged to ‘books banned by the fascists’ and that the play was ‘the parody of a revolution …. Topical’ (Figure 1). The book was printed in September 1944, but it is safe to assume that the blurb was added after the end of the war. The blurb was a severe denunciation of Fascist censorship and could be interpreted as a reference to the regime’s claimed revolution, thus supporting Grassi’s anti-fascism, but could also refer to more ‘topical’ events, such as the Resistance, at the end of which left-wing revolutionary forces were being gradually sidelined by the more moderate Christian Democrats, led by the Minister of Foreign Affairs Alcide De Gasperi.Footnote 5 It was Grassi’s subtle masterstroke. His carefully reformist canon was being reframed as a subversive one and, ‘[a]fter April 1945’ his position in favour of the socialist O’Casey and Irish theatre, though it entailed the adoption of plays that had been safely produced during Fascism, could be perceived as anti-fascist and ‘could be symbolically associated with a position-taking in favour of a social revolution in liberated Italy’ (Sisto Reference Sisto2016, 77).

Figure 1 Sean O’Casey, Il falso repubblicano (Milano: Rosa e Ballo editori, 1944)

Grassi’s editorial decisions had a positive impact on the immediate future of Irish theatre in Italy. While Grassi himself did not produce Irish plays in the first seasons of his Piccolo Teatro in Milan (from 1947), thus indirectly confirming the idea that Irish theatre was merely instrumental in his reform, other Italian theatres saw a good number of productions of Irish plays arising from the slightly outdated canon proposed by Linati and Grassi, particularly in Genoa (Teatro Sperimentale Pirandello) and Florence (Teatro dell’Università). Moreover, these years also saw a rediscovery of Yeats’s plays and poetry in Italy, involving the likes of Leone Traverso, Eugenio Montale and in particular the young critic Giorgio Manganelli, who would go on to become one of Italy’s most acclaimed and original writers. Manganelli was commissioned to produce a translation of Yeats’s plays and poetry by Guanda, which triggered his lifelong interest in Yeats and Ireland (Manganelli Reference Manganelli2002).

As we have seen, Irish literature was able to play such a unique role in Italy mainly due its ambiguous and uncertain status. The Italian public’s relative unfamiliarity with its repertoire, as well as the latter’s liminal political status, made it an ideal object of both political and aesthetic manipulation. After the early discovery by Linati and others at the start of the century, prompted by a genuine appreciation of Irish literature, the 1940s renaissance of Irish drama was primarily a result of political convenience. While mediators like Marinucci seemed invested in acquiring prestige through their association with the rapidly expanding repertoire of Irish drama and struggled to make the Italian public more familiar with it, Bragaglia’s interest seemed rather spurred by a lack of legitimate alternatives and was soon sidelined by his longstanding commitment to disseminating O’Neill’s works, as well as other successful Anglo-American plays, in Italy. The later use of ‘Irish drama’ by Grassi clarifies how adaptable the category was then, as is also shown by Grassi’s dismissal of it in subsequent years. It is certainly interesting to investigate the dissemination of Irish literature in Italy, but what this essay suggests is that despite the fluctuating elements constituting Irish literature in 1940s Italy, the history of the category – one is almost tempted to call it a ‘label’ – and its uses show how such a repertoire could be easily appropriated by both fascist and anti-fascist intellectuals, despite their profound ideological differences. If Ireland was simultaneously in and out of the war, the Irish canon in Italy also conveyed a comparable ambivalence; it was at once narrow and broad, fascist and anti-fascist, employed for political purposes and appreciated for aesthetic reasons, essentialised, rather than explored. It is perhaps no surprise, then, that while the interest in certain playwrights (e.g. Joyce, Yeats and Synge) remained strong in post-war Italy, the discourse on Irish drama rapidly left the centre-stage of the post-fascist and left-wing theatrical scene once its political value had faded.

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank Christian Goeschel, Christopher Rundle and Michele Sisto for the precious time they gave this article, the professional and patient archivists for their great support, and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. This work was supported by the Marie Skłodowska-Curie action under Grant (627852). Project Acronym: ItalianIrish

Antonio Bibbò has lectured at the Universities of Genoa, L’Aquila (Italy) and Manchester (UK), where he was Marie Curie Research Fellow (2014–2017) with a project on the reception of Irish literature in Italy 1900–1950. He curated the ‘Irish in Italy’ exhibition (Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Roma, Italy, 2016–2017), and has published essays on modernist literature, the politics of translation and canon formation, as well as critical editions of The Years by Virginia Woolf (Feltrinelli, 2015) and Moll Flanders by Daniel Defoe (Feltrinelli, 2017) in Italian. He sits on the editorial board of Contemporanea, Rivista di studi sulla letteratura e sulla comunicazione, and is currently an Honorary Research Fellow at the University of Manchester.