Over the last two decades, there has been a surge in English academic literature on the musical style known as cumbia. This scholarship has traced cumbia in local and transnational scenes, focusing mostly on its sociocultural dynamics.1 Cumbia is a polysemic signifier, referring to a wide variety of musics, dances, and expressive cultures taking place across the American continent and, at the time of this writing, worldwide. Nevertheless, little attention has been given to its musical and rhythmical aspects.2 However intricate cumbia’s origins may be, they are traceable to the Colombian Northwest and Panamá and the second half of the nineteenth century.3 While the wide array of music practices grouped under this single genre are heterogenous, cumbia’s distinctive rhythmic structures constitute one of the few musical traits present in most of its manifestations. This chapter offers an account of various Colombian grooves, some of which came to be circulated transnationally since the 1940s under the single denomination cumbia.

Focusing on a generation of Colombian drummers active in the 1950s and 1960s, we unpack the percussive lexicon that provided this music with its unique sound. Cumbia was a product of complex networks of music cosmopolitanisms and a generation of talented, creative, and savvy drummers. These artists were influenced by local and foreign sounds. The drummers we discuss and the specific recordings we study coincided with a moment where the Colombian national recording industry was booming. This surge, we argue, was concomitant with a dynamic and creative music practice/industry in which composers, performers, and producers were tuning in their ears to their audiences. Therefore, the musics we consider in this chapter develop between the encounter of a raising modernity that brought the emergence of transnational media industries and rural music practices. We discuss the work of four drummers and five rhythmic structures in Colombian tropical music; Pompilio Rodriguez’s merecumbé, Cecil Cuao’s cumbia, Nicolás Cervantes’s porro, and José María Franco’s gaita and fandango binario.

The style, technique, and instrumentation of these drummers illustrate their cosmopolitan drumming practice. Instrumentally, they used a hybrid drum kit that syncretized variations of the set developed and standardized in the United States (kick, hi-hat, toms, snare, and cymbals) with the timbales, cowbells, and clave found in Afro-Cuban musics. Their style was also influenced by musics coming from these countries, mostly swing and guaracha, respectively. However, a set of local music practices composed the very core of their aesthetic practice. Evidencing exceptional musicianship, these drummers took a series of grooves played by local ensembles and adapted and developed these grooves to be played on the drum kit. In the process, they created a vibrant aesthetic practice. These drummers’ intimacy with local rhythmic structures, evidenced in the way they crafted their grooves and the sense of technique they had, made their sound idiosyncratic. We identify two indigenous ensembles that were particularly influential: millo ensemble and banda pelayera.4

We use música tropical sabanera to refer to the wide array of musics we address. This categorization derives from merging the categories música tropical and música sabanera. Música tropical is an umbrella term used throughout the Spanish-speaking Americas that, broadly speaking, groups musics mostly of Afro-Colombian, Afro-Cuban, and Afro-Dominican descent, considered danceable.5 In the Colombian context, música sabanera refers to musics emanating from the savannahs (thus the ‘sabanero’ denomination) of inland Caribbean territories. Importantly, the ‘sabanero’ category alludes mostly to brass and accordion-based musics.6 Música tropical sabanera groups a diverse set of styles that originated in these same territories and that were actively produced and marketed as danceable musics, but that used a ‘jazz band’ instrumentation without accordion. Though deeply local in its inception, música tropical sabanera and the drummers behind it were the product of complex networks of music cosmopolitanism.

A Cosmopolitan Drumming Practice

In Colombia, música tropical sabanera (and most types of popular music) was recorded and produced in the city of Medellín, located in the northern Andes. As scholars have shown, in the early decades of the twentieth century, Medellín rose as Colombia’s most prominent industrial economy.7 Medellín saw the golden days of Colombia’s recording industry and the dawn of its radio industry. However, the origins of música tropical sabanera and the local recording industry are to be found in the Caribbean cities of Cartagena and Barranquilla.8

The colonial city of Cartagena de Indias was one of the ‘official’ ports through which enslaved African people entered the Spanish-occupied territories. It was in its peripheral territories where colonists, cimarrones (marrons), and indigenous people met, giving birth to a plethora of miscegenated cultural expressions, some of which run deep in the musics we discuss. Barranquilla, not being a colonial post, rose as Colombia’s most prominent port in the Atlantic – a distinction it continues to hold – in the 1920s. In an era of rising modernization across Latin America, Barranquilla became a node through which foreign performers and imported commodities entered the country; this included recordings, musical instruments, and recording gear. On top of this, radio sets in cities such as Barranquilla were capable of tuning in to Cuban radio stations, by then one of the major players in the transnational music market.9 The city was then a cosmopolitan hub. During the first half of the twentieth century, Barranquilla and Cartagena received the most current international sounds. This included jazz, tango, bolero, guaracha, and mambo, among many others.

Cartagena and Barranquilla were also among the first cities with ‘modern’ music industries. Three developments were significant in this regard: the opening of performance venues and the emergence of local radio stations and record labels. In the 1930s, tea rooms, dance halls, and social clubs became meeting points were middle- and upper-class audiences congregated for a time of leisure.10 These establishments offered live entertainment for well-to-do families, employed local talent, and hosted international staples such as the Cuban Trio Matamoros and the Orquesta Casino de la Playa.11 These visiting artists, plus the music local musicians were listening to through radio and recordings, were fundamental in shaping local jazz bands.12

Colombian jazz bands were equally influenced by local ensembles such as the aforementioned millo ensemble and banda pelayera. While the drummers we study did not perform in these indigenous ensembles, they were directly influenced by them. Since at least the 1940s, bandas pelayeras regularly travelled from nearby towns such as Monteria, Sincelejo, and San Pelayo to perform in Cartagena’s main square.13 In the case of Barranquilla, the millo ensemble has been an integral part of the city’s soundscape, particularly of its iconic Carnaval de Barranquilla. Therefore, while both of these local ensembles originated in peripheral areas, they were constantly listened to in the coastal cities.

Radio stations and record labels were also key agents. La Voz de Barranquilla and the Emisora Atlántico began operations in 1929 and 1934, respectively. In Cartagena, La Voz de Laboratorios Fuentes opened in 1934, directed by polymath Antonio Fuentes.14 Many of these stations broadcasted live music in radio-theatres. Antonio Fuentes’s record label Discos Fuentes was key in establishing música tropical sabanera. Bands that pioneered this sound such as Peyo Torres’s Orquesta Granadino (based in Sincelejo) and Simón Mendoza’s Sonora Cordobesa (based in Monteria) recorded for Discos Fuentes as early as 1952.15 Once in Cartagena, the musicians of these bands were hired to perform and record in other projects.16 This further illustrates the fluid musical circuit that existed between the coastal cities and their peripheries.

The high demand for jazz bands established this ensemble as a long-standing phenomenon. It was in the midst of this dynamic, cosmopolitan, and diverse context, that the drumming style we study emerged and developed. Knowledgeable of the rhythmic language behind transnational staples such as swing, mambo, and tango, but also deeply rooted in the wide array of local musics around them, the drummers we profile built the rhythmic foundation of what would eventually become a Pan-American phenomenon.

On Rhythms and Entextualization

The onto-epistemological implications of transcribing musics outside the Eurocentric canon have been dealt with at length by ethnomusicologists worldwide. As Ochoa Gautier has argued, entextualization, that is ‘the act of framing the musical object to be studied through multiple modes of “capturing” it’, has been essential in making non-Western musics ‘objects of knowledge’.17 While we acknowledge this, we also situate the musics we study as another instance of what Ochoa Gautier, following Garcia Canclini, calls Latin America’s ‘unequal modernity’. Being in a liminal space between the dynamics of media capitalism and rural cultural practices, música tropical sabanera is the product of such unequal modernity. Recordings constitute in themselves a form of entextualization.

While the musics we study were influenced by and used techniques derived from Eurocentric knowledge, i.e., orchestration and arrangement techniques, instruments, performance settings, etc., we locate their percussive elements in a space of in-betweenness. Local rhythmic structures intertwined with foreign ones. Importantly, this percussive lexicon existed outside Eurocentric music textualities. The transcriptions below and their respective analysis are then approximations of a rich, fluid, and highly improvisational practice and they constitute themselves an act of entextualization.

Merecumbé, Cumbia, and Porro: The Colombian ‘Tropical’ Sound

The 1950s saw the boom of the Colombian recording industry. Modernized iterations of cumbia (from accordion as well as millo ensembles) and porro pelayero – musics previously deemed as rural and racialized – rose to the national sphere. First emerging in the private clubs, radio stations, and recording studios of Barranquilla and Cartagena, cumbia and porro eventually made it to similar spaces in the Andean cities of Medellín and Bogotá. This was indicative of a major shift in the nation’s aural politics. Such moves came along significative aesthetic changes. Presenting a sophisticated demeanour, the bands leading this charge were those of Edmundo Arias (1925–1993), Antonio María Peñaloza (1916–2005), Francisco ‘Pacho’ Galán (1906–1988), and Luis Eduardo ‘Lucho’ Bermúdez (1912–1994). Such demeanour was matched by the music’s composition. Fully notated arrangements for jazz band ensembles, occasional solos with background accompaniment, and a playful yet controlled rhythmic section were salient characteristics.

Following Wade, scholars have used the concept of whitening to theorize this transition from rural sounds to national soundtrack.18 Proposing a ‘modernist teleology’ suggesting that bands such as those of Galán and Bermúdez diluted the music’s rhythmic complexity, wore formal garments, and portrayed an aura of sophistication in order to appeal to a middle- and upper-class bourgeois sensitivity, Wade argues that these aesthetic and sociocultural shifts were concomitant with a racialized perception white mestizos (broadly speaking, miscegenated yet predominantly racially, and most importantly ethnically, white populations) had of these rural musics. Adapting music techniques and production values derived from the Euro-American canon was thus an aesthetic manifestation of these whitening racial dynamics.

We nuance this argument by suggesting that these bands’ percussive aspects complicate such a claim. Put differently, we find in the rhythmic lexicon we study a rich, inventive, and intricate drumming technique that, although not ‘traditional’, is also not ‘modern’ in the teleological sense the whitening concept presupposes.19 Furthermore, we find in this music practice a delicate balance between creativity and media industries. Record labels, composers, band leaders, performers, venues, and consumers were all part of a network of distributed agency.

Similar to Euro-American dance crazes such as the charleston or the twist, in the 1950s, Colombian band leaders sought to establish novel dance rhythms in the market. Bermúdez’s gaita and Galán’s merecumbé were among the few that achieved national (and international) relevance. Created by Pacho Galán in collaboration with drummer Pompilio Rodriguez (1929–2007), the merecumbé – its creators argued – was a combination of merengue and cumbia (as performed by millo ensembles).20 In 1929, Rodriguez’s father Francisco Tomás Rodriguez founded the orchestra Nuevo Horizonte. Pompilio toured with his father since age twelve, performing a wide array of styles. By the time he started working in Galán’s orchestra in 1956, he was a veteran. Rodriguez explains that, in creating the merecumbé, he was inspired by Galán’s brass arrangements.21 According to Rodriguez, Galán asked him to build a groove that would fit the genre’s self-proclaimed originality.

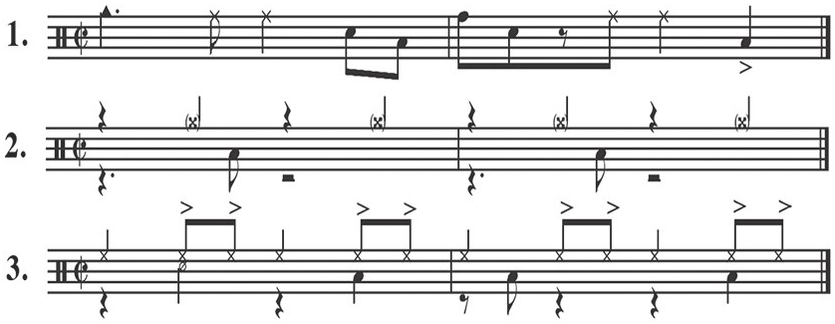

The merecumbé became a major hit, prompting Galán to record entire albums in this style.22 Compared to other structures in this chapter, merecumbé is less improvisational. In the track ‘Rico Merecumbé’, released in 1958 by the label Ondina, Rodriguez built three variations of the groove (Example 4.1) that match Galán’s arrangement. We transcribe the basic structure of each variation and number them using Arabic numerals. Variation number one is the merecumbé proper. With it, Rodriguez accompanied the only sung section of the piece; a chorus intercalated with a call and response arrangement between the saxophones and trumpets. Importantly, the actual merecumbé groove (variation one) only appears when the chorus sings ‘hay que rico merecumbé’, making the connection between Rodriguez’s rhythmic structure and the genre explicit.

In the track, Rodriguez used most timbres of his hybrid drum kit composed of kick, snare, and cymbals with timbales and cowbells. The cowbell, that only appears at the beginning of the cycle, marks a ‘broad downbeat’, becoming an anchor point for an otherwise syncopated structure. The transition from cáscara to timbal high and low was designed to counterpoint Galán’s merecumbé-style brass arrangement.23 The resolution on the second off-beat of the second bar is characteristic of cumbia as performed by millo ensembles. While in traditional formats this accent is played on the indigenous bass drum– like tambora, Rodriguez used the timbal low to emulate the instrument’s low-pitched sonority. In variation two, he ‘opened up’ the groove into the crash cymbal playing the constant off-beat stylistic of traditional banda pelayera and millo ensemble. In jazz band formats, this off-beat is played by the hand-held cymbal doubled by the maracón rattle. The one-quarter-note-two-eighth-notes pattern found in most musics called cumbia appears in variation three. In both the second and third variations, Rodriguez added ornaments. The syncopated eighth note he placed in between the main line (second beat of bars 1 and 2 of variation two, and the first beat of the second bar of variation three) gives the groove more drive.

Along with cumbia and merecumbé, porro was the most popular type of música popular sabanera in the 1950s and 1960s. In fact, porro arrived in México before cumbia.24 While musically distinct, all of these rhythms were circulated outside Colombia under the single name cumbia.25 Being one of the most transnationally successful bandleaders of this scene, Lucho Bermúdez’s porro composition ‘Arroz con Coco’ is illustrative of this style’s rhythmic structures.26 Recorded in 1956 for the label Silver, the track features Nicolás Cervantes on drums. Brother of drummer Reyes Cervantes, Nicolás was part of the Barranquilla-based Emisora Atlántico Jazz Band.

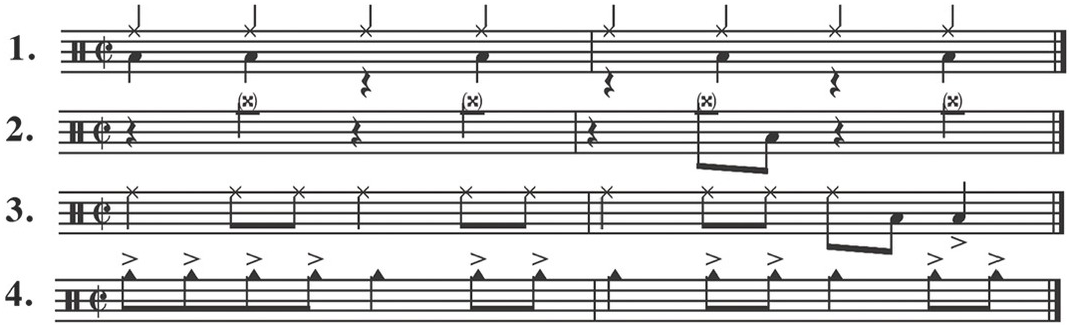

In variation one, Cervantes held a strong downbeat on the cowbell (sometimes doubling it with the kick) and phrased in a fluid and syncopated fashion with his other hand. The one-hand roll (bar 1) and eighth note phrasing (bars 2, 3, and 4) illustrate Cervantes’s mindful equilibrium. On the one hand, Cervantes held the downbeat with the cowbell to provide the dancer with a clear sense of beat. On the other hand, Cervantes played fluidly on the timbales, keeping the groove fresh and engaging. In variation two, Cervantes transitioned from half notes to the quarter-note-eighth-note rhythm on the cowbell in a more soloistic fashion. We transcribe a passage of these variations in Example 4.2. Moving between kick, floor tom, and snare, Cervantes shows great dexterity. While on some occasions Cervantes used the kick to support the downbeats, he also used it to orchestrate the improvised phrases built around the cowbell pattern.

Example 4.2 Two stages of Nicolás Cervantes’s porro groove in Lucho Bermúdez’s ‘Arroz con Coco’

The Cuao family deserves a special mention in the history of música tropical sabanera. Formed by brothers Wilfredo (Lucho Bermúdez’s drummer for several years), Cecil (also known as ‘Ciser’ or ‘Calilla’), Tomás (‘El Mono’), and Juan Carlos (‘Juancho’), all born in the city of Santa Marta, the Cuao drumming dynasty was deeply influenced by Panamanian drummer Ruben Dario Romerín. Romerín arrived in Santa Marta with a jazz band, eventually settling there. His influence speaks of the crucial role Panamá and Panamanian musicians have had in the history cumbia. We focus on Cecil Cuao’s rendition of the cumbia ‘La Pollera Colorá’, composed by Juan Bautista Madera and Wilson Choperena. Cecil Cuao recorded this version in 1960 with the orchestra of Pedro Salcedo (1910–1988). This track contains several of the rhythmic structures that became staples of cumbia, as performed by these formats, especially its opening section. In it, Cuao focuses on the timbal low and cáscara playing a series of breaks (Example 4.3, variation one).

Example 4.3 Three stages of Cecil Cuao’s cumbia groove in Pedro Salcedo’s ‘La Pollera Colorá’

Following the local terminology, we call these repiques. We do so to stress the geopolitical specificity of this drumming practice and avoid faux homologies with Euro-American counterparts such as ‘fills’ or ‘comping’. Repiques are passages where the basic groove is ornamented, leaving the main rhythmic structure altogether at times. Deeply rooted in local drumming practices, repiques are an expression of enjoyment and virtuosity. Although common in transitional parts of the structure, repiques can happen at any time and with different intensities.

In ‘La Pollera Colorá’, Cuao’s repiques derive from the rhythmic structures of the tambora as performed in millo ensembles. These structures are fundamental to set the tone of the track. We include the llamador hand drum in the transcription (replaced on this track by a conga) to show the polyrhythmic quality of the groove. The phrasing constantly driving towards, and often resolving on, the second off-beat (bars 2 and 4 of variation one) is particularly stylistic. After the introduction, Cuao added the cáscara, using flams that emulate the tambora sound and technique (bars 1 and 3 of variation two). In variation two, Cuao used a mixture of rim shots and repiques to accompany the instrumental melody. Finally, when the voice appears, Cuao played a bare-bones version of the tambora cumbia groove in variation three.

Gaitas and Fandangos Binarios: José Mariá Franco and the Rural-Cosmopolitan Sound

José María Franco was one of the most creative drummers of música tropical sabanera. His work with Orquesta Emisora Fuentes, Orquesta A No. 1, Sonora Curro, and band leaders Pedro Laza (1904–1980) and Rufo Garrido (1896–1990) are particularly salient. The sound of these bands has been characterized as ‘rootsy’.27 Arguably, this notion has been constructed in relation to Lucho Bermúdez’s and Pacho Galán’s bands. The latter presented a more sophisticated image and a sound more in line with the Latin American dance bands of the era. In contrast, Laza’s and Garrido’s bands were less stylized. Showing a more direct connection to banda pelayera, their performers displayed a sense of technique and sound quality mostly unconcerned with Eurocentric standards. Under the guidance of Discos Fuentes’ owner Antonio Fuentes, Pedro Laza made the connection explicit by naming his band Pedro Laza y sus Pelayeros.

Drumming-wise, José María Franco’s style was improvisational and deeply rooted in rural traditions. Using a hybrid drum kit composed of snare, kick, hi-hat, cymbals, and timbales, Franco adapted the distributed percussion traditionally performed in banda pelayera (snare, hand-held cymbals, and bass drum) into a single kit. In ‘La Compatible’, Franco performed four variations of the groove (Example 4.4). In the introduction (variation one), eighth notes on the cáscara are overlaid by a constant off-beat on the timbal low, a common trait in the gaita style. During the brass melody (variation two), Franco ‘opened up’ this syncopated feel into the crash cymbal, ornamenting on the timbales. The one-quarter-note-two-eighth-notes cumbia pattern appears with the clarinet melody/solo (variation three), played on the cáscara with some important variations we consider below. For the trombone solo (variation four), Franco ‘closed up’ the groove, avoiding variations and transitioning from cáscara to woodblock/cha cha bell (also called ‘coquito’), playing straight eighth notes at times and making the overall texture more articulated.

Example 4.4 Four stages of José Franco’s gaita groove in Pedro Laza’s ‘La Compatible’

The excerpt from Franco’s repique in La Compatible we transcribe in Example 4.5 illustrates the music’s improvisational nature and rhythmic style. The eighth-note-to-quarter-note rhythmic resolution towards the second off-beat (bars 1 and 8) and the dotted eighth notes transitioning between downbeats and off-beats (bars 2 to 6), all of them in the timbal’s low register, are stylistic of traditional cumbia as performed by tambora in millo ensembles.

In ‘El Arranque’, also recorded in 1960 for Discos Fuentes and released in the album Fandango, Laza and Franco elaborated on the traditional style of fandango as performed by banda pelayera. While the traditional fandango is ternary, El Arranque’s subdivision is mostly binary. Due to the fact that the track is called a fandango in the record but that it is binary, we use the denomination fandango binario. Using a similar drum kit configuration, Franco kept a steady line on the kick throughout (Example 4.6). The structure he used in variation one is found in musics across the Americas; it is commonly known as the Cuban tresillo (♩. ♩. ♩).This cell is also found in several musics of the Colombian-Caribbean. Importantly, the rhythmic feel of the figure is neither binary nor ternary. This probably has to with the track’s fast tempo, but also with Franco’s familiarity with these percussive languages. In particular, the second dotted eighth note falls in a rhythmic space non-quantizable under Eurocentric standards. This is crucial in building the overall character of the track.

As Franco held this figure on the kick, he phrased on the snare. The technique and style are deeply influenced by banda pelayera. The unarticulated rolls and sudden and syncopated rim-shot accents with a three-against-two feel are stylistic of this tradition. The maracón, playing a constant figure departing from the off-beat and landing on the downbeat, created a polyrhythmic, syncopated, and ‘ahead-of-the-beat’ feeling. In the second variation, Franco transitioned to the cha cha bell in ‘coquito’ style. In variation three, Franco doubled the maracón. However, on this occasion, Franco muted the crash cymbal on the downbeat, a common technique used in música tropical sabanera.

In Franco’s style, and particularly in his collaborations with Pedro Laza and Rufo Garrido, we find a language deeply influenced by banda pelayera. However, cosmopolitan influences are also salient. The use of timbales and Franco’s orchestration on the cáscara and cowbells shows a strong link to Afro-Cuban musics, especially to guaracha. As a matter of fact, the bands of Garrido and Laza recorded several ‘Colombian guarachas’. On top of that, the fact that a drum kit was used and that these local musics were being performed by jazz band ensembles signals a strong connection to US swing music. We observe similar influences in the drumming techniques employed by all the drummers considered in this chapter.

Closing Remarks

We have used the term música tropical sabanera to group a wide variety of sociocultural contexts and music practices. On the musical side, two characteristics connect them; the jazz band format and an aesthetic practice that syncretized rural musics of the Colombia-Caribbean with transnational ones such as swing and guaracha. The emergence of these musics was concomitant with the advent of the Colombian music industry in the twentieth century.

This process of commercialization and syncretisation does not imply a teleology in which music continuously evolved to reach Euro-American (read white) standards – what we have called modernist teleology. The aesthetic practices and racial dynamics of música tropical sabanera tell a much more nuanced story. While the music of Pacho Galán, Lucho Bermúdez, and Pedro Salcedo did portray a more sophisticated aura, its percussive lexicon was anything but ‘diluted’ or ‘simplified’ (adjectives often used to describe these musics vis-à-vis the style of millo formats). The rhythmic structures we have analysed tell us about a creative, exciting, and idiosyncratic music practice. Signalling a different aesthetic practice, the bands of Pedro Laza and Rufo Garrido developed a sound more influenced by local practices, particularly banda pelayera. For all practical purposes, the idea of whitening forwarded by Wade and other scholars accounts for the fact that, while Bermúdez, Galán, Edmundo Arias, and Pedro Salcedo rose to transnational prominence, Pedro Laza, Rufo Garrido, Clímaco Sarmiento, Peyo Torres, and bands such as La Sonora Cordobesa did not. Bermúdez, in particular, toured transnationally in México, Cuba, and Argentina, performing his arrangements with local orchestras. These tours were important – though not the only – agents in circulating cumbia across Latin America. In this light, the drummers behind these rhythmic structures are the unsung heroes of a sound that spread throughout an entire continent.

As fundamental as these drummers are, their stories and legacy continue to be mostly unknown, even for Colombian drummers studying traditional musics. While the turn of the millennium brought a renewed interest for rural musics by academically trained musicians, the drumming practices of música tropical sabanera have fallen under their radar. Ignoring that such a process already took place half a century before them, contemporary drummers go back to banda pelayera and millo ensembles and re-adapt these rhythms to the drum kit, thus reinventing the proverbial wheel. Be that as it may, the music created by these drummers continues to resound through an entire continent and, nowadays, with cumbia’s international prominence, the entire world.