How we assess globalization is largely determined by how we see the world economy. Aggregates such as GDP, trade flow maps, unemployment figures, quality of life indices, natural resource estimates, purchasing power parities, and stock market indices each carry their own narratives about progress and failure in a comparative international framework.Footnote 1 Around 1900, economic data was scarce but economists still engaged in heated debates about how to communicate and evaluate the state of global capitalism. They drew metaphors from contemporary media technologies to do so, including museum exhibitions, cartography, and photography. Their metaphors reflected economic thinking but also helped to shape it, producing expectations and assumptions about the course that global capitalism should and would take.Footnote 2

German and Austrian economists were precocious theorists of the world economy. Even as parallel discussions were happening with different vocabularies, the term ‘the world economy’ itself existed in no major world language except German before the 1920s.Footnote 3 While ‘the economy’ was not described with the definite article in English until the 1940s, German-speaking economists had identified it as a spatial and material object – a ‘measurable entity, a “thing”’ – by the mid nineteenth century.Footnote 4 German and Austrian discussions of the world economy (die Weltwirtschaft) from the 1880s to 1914 are an overlooked first chapter in the genealogy of globalization debates that still continue, providing insight into the emergence of ‘the global’ as a native category rather than one of retrospective analysis.Footnote 5

This article follows a disagreement among German-speaking economists about how to see the world economy. On one side were the so-called ‘historical economists’, who favoured empirical methods of statistics and sociology and were closely linked to projects of social policy reform in imperial Germany and Austria. Their central category was Verkehr, defined as communication and commerce as well as traffic and intercourse. It always implied a foundation in material and legal infrastructure.Footnote 6 Historical economists, including the unjustly forgotten pioneer of international economic statistics, Friedrich Neumann-Spallart, used trade and production numbers and cartography to make visible what they called the ‘world economic organism’ in the late nineteenth century. Their focus on cross-border trade and the extension of telegraph and rail networks reinforced the primacy of distance, inferring that lateral expansion was synonymous with economic progress.

On the other side of the argument were the marginalist economists who rejected panoramic descriptions of the world economy for a narrow focus on price movements. A young Joseph Schumpeter borrowed a metaphor from photography to describe the marginalist method.Footnote 7 At commodities and stock exchanges, he argued, one could literally see world prices being produced from moment to moment. With telegraphs and telephones transmitting those prices to the ends of the earth, commerce and communications seemed to have made a world market without borders a reality.

Historical economists developed their ideas in the shadow of British power and their concepts resonated in countries with similar experiences of uneven development. The German concept of the world economy as a historically constituted space of unequal exchange was translated into 1920s India and 1930s South America and underwrote the dependency theory of Raul Prébisch in the 1950s.Footnote 8 The terms of ‘centre and ‘periphery’ in the world-systems theories of Samir Amin, André Gunder Frank, and Immanuel Wallerstein were first used by the historical economist Werner Sombart in the 1920s.Footnote 9 Including Karl Marx's analyses and the Austrian economist Rudolf Hilferding's theories of imperialism, the entire tradition of critical international political economy emerged from central Europe around 1900.Footnote 10 These German-speaking debates capture a sophisticated discussion about the nature of the world economy and a lasting division in how to see it: either in the spatially expanding networks of communication and trade or in the wandering movement of prices on the world markets.

The panoramic imagination

The universal exhibitions of the nineteenth century were signal venues for both staging and gaining an impression of the world as a single bounded entity. Neumann-Spallart, born the son of a wealthy magistrate in 1837, finished his doctorate in law and economics at the University of Vienna in 1862.Footnote 11 Tasked with compiling a report of several thousand pages on the Paris Universal Exposition of 1867 for the Austrian crown, he focused on three exhibits. The first was a large mounted map showing the ‘thousand-fold intricacies of the European telegraph network’, the second a diorama where a system of ‘needles and threads made the myriad intersecting lines and offices of French telegraphy visible in a tiny scaled-down picture in front of our eyes’, and the third a large sculptural representation of the Suez Canal.Footnote 12 Neumann-Spallart's focus on telegraphy is telling. The advent of international telegraphy, with the first durable transatlantic cable laid in 1866 and others developing rapidly in the following decade, produced an unprecedented sense of global connection as well as presenting new challenges of representation.Footnote 13 The expansion of telegraph networks ‘transformed people's understandings of communication, and with it, their notion of their relation to others’.Footnote 14 Like atlases, maps, and globes, the Paris exhibits represented vast space in miniature, and prompted viewers to imagine themselves inhabiting the space depicted.Footnote 15

Universal exhibitions and museums ‘set up the world as a picture’, in particular through panoramic portrayals of exotic locales and their inhabitants.Footnote 16 Meanwhile, modern optical and epistemological techniques were used to ‘make legible’ populations and territories as part of ‘seeing like a state’.Footnote 17 Dubbing the nineteenth century the ‘century of counting and measurement’, one historian calls the universal exhibitions ‘the most visible expression of the unification of the panoramic gaze with the will to encyclopaedic documentation’.Footnote 18 These insights can be transposed to the realm of the world economic. In their attempts to represent the globe as a space of territorially bounded nations and empires linked by flows of information and commodities, and especially in their intersections with cartography, statisticians sought to see in the same way as universal exhibitions. They set up the world as a picture, supported by an apparatus of positivist factual verification.

Neumann-Spallart published the world's first statistical survey of the international economy after the exhibition that followed Paris, in Vienna in 1873. The reality of global economic interdependence came home that very year with a stock market crash in Vienna.Footnote 19 Mediated by the new communications technologies of the transatlantic telegraph and the stock ticker, the Austrian and German collapse spread across western Europe and the US, leading Baron Carl Meyer von Rothschild to remark that ‘the whole world has become a city’.Footnote 20 In the first article of the Austrian journal Statistisches Monatschrift (Statistical Monthly), Neumann-Spallart observed that the sequence of crashes had created an uncanny scale shift, by which ‘an apparently purely local evil’ spread in ‘concentric waves’ to manifest as a ‘chronic, sagging contagion’ at the continental and international level.Footnote 21

Other events preceding the 1873 crash had conveyed the consequences of the increased international financial entanglement and the new communicability of economic disorders.Footnote 22 The term ‘crisis’ was first coded as primarily economic following the negative effects of the US gold rush in central Europe in the mid 1850s.Footnote 23 In the 1860s, the end of supplies of New World cotton during the US Civil War created the ‘cotton famine’ and the world's first ‘raw materials crisis’.Footnote 24 More long-lasting was the collapse of agricultural prices when improvements in shipping brought US and Argentine wheat into the European market for the first time around 1880.Footnote 25 In a novel by Gustav Freytag published that year, a character describes his town as ‘linked to Weltverkehr now by iron bands’.Footnote 26 The fall in transport costs, the expansion of communication networks, and the mechanization of production fostered an enormous increase in trade volume and, despite rising tariffs, a global convergence of commodity prices, often to the detriment of agricultural producers in central Europe.Footnote 27

By the 1870s, global interdependence could not be ignored. In the introduction to his first volume of statistics, Neumann-Spallart wrote that ‘the world economy has developed with unforeseen rapidity since the middle of our century; the form of a higher organism containing all civilized countries of the earth is emerging ever more clearly’.Footnote 28 A corresponding way of framing this economic reality was necessary both to understand it and to assuage popular anxieties. The matter was urgent because of pressure from protectionist lobbies within both the German and the Habsburg empires.Footnote 29 The 1880s saw tariff walls rise across continental Europe.Footnote 30 As an embattled advocate of free trade, Neumann-Spallart was concerned with the global attribution of blame. Some people, he wrote, were making ‘the world economy responsible for everything evil that happens to us’. Just as ‘we once feared comets, so many people are seized by the sense that some indefinable thing floats above us, adjoins us and could destroy us: free trade. We have overcome the fear of comets, we will also master the fear of the world economy.’Footnote 31

In their efforts to convey the reality of global interdependence to lay audiences and policy-makers, historical economists developed persuasive forms of rhetoric and representation. In 1906, Ernst von Halle, a professor at the University of Berlin, quoted from Goethe's Faust to describe the goal of his multi-volume primer on The world economy. He wanted not only to provide ‘dry figures and data’ but also to demonstrate ‘How each to the Whole its selfhood gives/One in another works and lives’.Footnote 32 The couplet comes in the play's first scene, when Faust, dismayed with secular science, becomes enraptured by the sign of the Macrocosm, an ancient symbol relating the individual to the totality of the universe.Footnote 33 Economists needed to give shape and sense to a stage of global development in which ‘no single branch of production and trade, no single direction of commerce can be judged without seeing the connection of the individual case to the whole’ and ‘everything is so connected by thousands of threads to the conditions of the world market that it cannot expand without a connection to it’.Footnote 34

The importance of the textile industry in European industrial development encouraged metaphors linking networks of communication and transportation with the literal fabric of production. There was an easy slippage between the language of threads (Fäden) and wires (Drähte), woven webs/textiles (Gewebe) and networks (Netze).Footnote 35 Von Halle referred to the world economy in 1900 as ‘the entire garment produced by the labour of millions at the speeding loom’.Footnote 36 In 1894, Max Weber used the textile metaphor to imply both the higher agency and the superior knowledge of the market, saying that economic organization

binds each individual to countless others via uncountable threads. Each person tugs on the network of threads, in order to arrive at a position where he wishes to be and where he believes his place to be, but even if he were a giant, and had many threads in his own hand, he would far more be moved by others over to a place that is actually open for him.Footnote 37

The task of economists was to identify and demystify the world economy, and to recast interdependence as a manageable challenge for informed policy-makers.

Economists turned to the tools of statistics and cartography for their task, leading them to international collaboration. Neumann-Spallart's World economic surveys (Übersichten der Weltwirtschaft) ran through several editions from 1878 until his early death in 1888, when his fellow Austrian economist (and grandfather of Friedrich Hayek) Franz Juraschek took up the project. The World economic surveys were the first synoptic volumes of global trade statistics, producing data still used by economic historians.Footnote 38 Neumann-Spallart compiled them through the International Statistical Congresses (ISC) and later the International Statistical Institute (ISI), which he had a direct hand in founding in 1885. Though commercial statistics were fragmentary and unreliable in this period, his works represented the best available surveys, gathered through standardized forms drafted at the third meeting of the ISC in Vienna in 1857 and distributed on the suggestion of the Prussian statistician Ernst Engel in 1869.Footnote 39 Though authored putatively by Neumann-Spallart, the World economic surveys were the product of an unprecedented transnational exchange of economic information.

The international statistical associations are overlooked fixtures of nineteenth-century ‘global civil society’.Footnote 40 Adolphe Quetelet formed the ISC in 1853 after developing the idea at London's Great Exhibition in 1851.Footnote 41 While the collection of ‘social statistics’ on ‘disease, poverty and crime’ flourished at a national level across Europe after 1830, international cooperation had advanced only slowly.Footnote 42 At its final meeting, in Budapest in 1876, the ISC looked beyond Europe, including delegates from Egypt, Japan, and Brazil.Footnote 43 Despite this, the congress was forced to disband temporarily in 1878, when the Prussian government prohibited statisticians from cooperating with the ISC. This was probably a culmination of Bismarck's explicit antagonism toward statistics that could be used to criticize his policies, as well as that year's political crisis in Germany which ended in an anti-socialist law opposed by many historical economists.Footnote 44

Statisticians revived their efforts at international collaboration in 1885, at the quarter-century jubilee of the Paris Statistical Society and the half-century anniversary of the London Statistical Society.Footnote 45 Leading statisticians tasked Neumann-Spallart with surveying the ISC's successes to date and proposing a reorganization. Speaking alongside Alfred Marshall and Francis Galton and in front of the major figures of social reform and demographic science Edwin Chadwick and Jacques Bertillon, Neumann-Spallart offered the draft statutes for what would become the ISI.Footnote 46 He reflected on the difficulties of observation for statisticians: ‘the astronomer in his observatory, the chemist in his laboratory, the physiologist dissecting the body to investigate its mechanism, all can obtain without extraneous help the most valuable scientific results. The statistician, on the contrary, alone and unaided can do nothing.’Footnote 47 If the astronomer's problem was how to see the heavens, and the doctor's how to see the body, the economist's problem was how to see, and represent, the global economy. Creating such a portrait was, by definition, a collaborative process.

Neumann-Spallart's World economic surveys represented the fruits of this collaboration within international civil society, creating a new authoritative basis for expert economic knowledge about the world economy in an era when debates about free trade versus tariffs divided all major states.Footnote 48 In the statistical surveys published by Neumann-Spallart and Juraschek, the world economy became an entity visible in tables of figures and bound within the boards of a single book. It contained information on trade and production but also data on ‘strikes and lockouts, emigration, marriage and birth-rates, suicides and pauperism’, indicating a more expansive vision of the world economy than just monetised exchange and fixed capital.Footnote 49 The World economic surveys became a standard reference work on both sides of the Atlantic.Footnote 50

The collection of statistics aided in the ‘metaphorical constitution’ of the national economy.Footnote 51 In collating global economic statistics, Neumann-Spallart achieved this task on a planetary scale, making the notion of global economic unity a visible entity capable of being held in one's hands. He saw his task as creating the numerical version of the dioramas he saw at the exhibition: something that imparted information as well as a sense of vastness, and that conveyed complexity while containing it within the frame of representation. Referring to the power of numbers, he wrote that ‘one could see in tables the enormous upswing’ which the international trade of European nations had experienced before the crisis of 1873 and ‘we will be able to follow the progress of recovery clearly in trade statistics’.Footnote 52 Making invisible economic forces visible in the communicative medium of statistical tables, he hoped to tame the fear of global capitalism.

The world economic organism

International opinion was divided about what conclusions to draw from the World economic surveys. In 1888, the US Commissioner of the Board of Labor Carroll D. Wright expressed ‘regret’ and ‘envy’ that the US did not have trained statisticians like Neumann-Spallart to advise policy-makers.Footnote 53 Yet the nation's leading statistical economist, Richmond Mayo-Smith, was sceptical about the specific framing of the argument. A professor at Columbia University and co-founder of the American Economic Association, Mayo-Smith had studied under Wagner and Knies in Berlin and Heidelberg.Footnote 54 He wrote in 1897 that Neumann-Spallart and Juraschek had set out to show ‘the development of a “world economy”, which appears as the highest “organism” whose mission it is, not to obliterate the individual states, but to bring them to the highest manifestation of their powers’. He put the key term in quotation marks, revealing the poor fit of ‘world economy’ in English at the time, even for those acquainted with German historical economics. He distanced himself from the thesis, saying that ‘we may not agree with him in desiring to use the name organism for these international relations’.Footnote 55

The analogous terms circulating in both English and other major world languages in the late nineteenth century were still those gleaned from the widely translated works of Adam Smith and David Ricardo, including variations on ‘the commercial world’, ‘the trade of the world’, and the ‘world's wealth’. None connoted the same amalgam of socioeconomic processes and institutions, material infrastructures, and territory as ‘world economy’. While classical liberals such as Smith and Ricardo had discussed the idea of a global economy, they had been hypotheses and projections. When Karl Marx reported the ‘universal interdependence of nations’ and a ‘world market’ that had ‘given a cosmopolitan character to production and consumption in every country’ in The communist manifesto, he described a world of the future.Footnote 56 By the late nineteenth century, however, the world economy was no longer a prediction but a reality.

The special attention to geography and material infrastructure in the historical economists’ concept of the economy was a deliberate critique of the abstractions of British classical liberalism. They saw the free trade prescription of Smith and Ricardo as a straightforward reflection of the early industrializing Britain's ability to dominate the world market. Friedrich List called the classical liberals’ global state of perfect competition ‘cosmopolitan economy’, arguing that it did not exist in reality but only on the page.Footnote 57 To the placeless perspective of classical liberalism, List and historical economists proposed a conception of the economy rooted in geography and history, relying on statistics and attention to structural factors to interrogate the advantages and disadvantages of free trade. This idea had traction in other developing countries. Adopted from German sources, the territorial idea of ‘the national economy’ was central to nationalist claims made in colonial India and imperial Japan, as well as in critiques of laissez-faire policies in the United States.Footnote 58 Founded two years after the German empire emerged in 1871, the historical economists’ Verein für Sozialpolitik (Social Policy Association) was imitated in Japan, Hungary, Ireland, the US, and elsewhere.Footnote 59 The association, with a membership that was one-quarter Austrian by the late 1890s, offered a template for the economist as policy adviser, producing useful knowledge to support national efforts to catch up with Britain.Footnote 60

Historical economists embraced organic metaphors to describe the national and world economy, adopted, in part, from the social evolutionism of Herbert Spencer.Footnote 61 In their stagist understanding of the economy, the increasing specialization of social groups was a sign of development and progress.Footnote 62 The world economy was the most recent stage of the organism's evolution.Footnote 63 As the scale of economic activity grew over time, institutions also developed to facilitate and regulate the market through social policy.Footnote 64 While economists still disputed the existence of a world economy before 1850, technical advances in communication and transportation, along with international institutions such as the International Telegraph Union (1865), the Universal Postal Union (1874), the International Union on Weights and Measures (1875), and agreements on parcel post (discussed by Léonard Laborie in his contribution to this issue), helped to transform it from a future possibility into a fact to be managed.

Neumann-Spallart's description of the world economy as a more advanced permutation of the national economy was absorbed into German-language scholarship. His article in a leading economics journal in 1876 stated that legal agreements and international associations, along with the infrastructure of ‘trade and freight, railways, post and telegraphs’, meant that ‘the world economy has emerged alongside individual national economies as a higher organism of decided originality’.Footnote 65 Two years later, he said in a speech in front of the Society of National Economists (the Volkswirtschaftliche Gesellschaft) in Berlin that ‘the diversity and volume of goods that move incessantly from country to country, from city to city in the hustle and bustle of the world is so large that it alone infers the de facto existence of a genuine world economy’.Footnote 66

In the same year, Adolph Wagner, who was present at the speech, cited Neumann-Spallart as he formulated what became the most commonly reproduced definition of the world economy in Germany and Austria, writing that

the national division of labour expands to an international one in the world economy … the world economy then, like the national economy, can take on the nature of a great organism, in which the individual national economies (or, more accurately, the individual economies) have the function of limbs. Far more than in previous periods of world history, current conditions have allowed today's trade to unite the national economies into a single world economic organism spanning the earth.Footnote 67

In 1900, Schmoller wrote in his own textbook that ‘we conceive of the totality of economic life on the entire earth as the sum of geographically contiguous and historically consecutive national economies … The sum of the national economies that have come into contact and mutual dependence today we call the world economy.’Footnote 68 Thus, around 1900, the historical economic theory of globalization portrayed the world economy as a unified entity organized by the international division of labour, governed by international treaties, and linked by the ligatures of communication, transportation, and trade.

The primacy of distance

Historical economists arrived at their conclusions about the global economy through an interdisciplinary approach, combining insights from the fields of ethnography, history, and the nascent one of sociology.Footnote 69 They were also guided by organicist metaphors, which led them to an allegorical narrative about the expansion of the scale of economies over time. Along with other contemporary observers of communications networks, economists spoke frequently of the ‘world-spanning’ ties of infrastructure and trade, the spatial barriers overcome by new technology, and the broad scope of international trade.Footnote 70

The tools of measurement used by economists encouraged a perspective that focused on horizontal extension over the earth's surface. The most concrete evidence about the global economy was often drawn from the tables compiled by Neumann-Spallart and Juraschek. Wagner called trade statistics the ‘mirror image’ of the world economic organism, granting them considerable diagnostic authority and suggesting that the columns of figures were the medium in which the reality of the world economy was made visible.Footnote 71 Yet the limitations of available data meant that the ‘mirror’ showed an inevitably distorted image of world economic activity. Juraschek was frank about his own constraints in the handbook to a popular world atlas published in 1899: ‘The vast majority of commerce’, he conceded, happened inside nations or customs unions and thus eluded ‘statistical observation almost entirely’.Footnote 72 Goods were only recorded when they crossed national borders and even then differences in weights and measures, along with price fluctuations, meant that assessment of trade volume was always approximate.

One economic historian has suggested that ‘measurement, maybe even more than theory, contributes to the making of new ontic furniture for the economic world’.Footnote 73 The limitations on statistics-gathering in the first wave of globalization led to a privileging of cross-border commerce and infrastructure, or what could be called a primacy of distance in historical economists’ conceptualization of the world economy.Footnote 74 Werner Sombart voiced this criticism himself in 1903, dissenting from the consensus of those who ‘use trade statistics to speak of the emergence of a world economy’ understood ‘as a state of progressive differentiation and integration of the national economies with one another’.Footnote 75 Such a conception is ‘decidedly false’, he wrote, because ‘even as world-economic relations gain in extensiveness, they decrease in intensity’.Footnote 76 He argued that the domestic market was the motor of development and remained more important even if this was not as easily conveyed in statistics (which often did not exist) or maps (which often focused on the global perspective). Simply because customs data was available, while records of other kinds of trade were not, cross-border commerce assumed disproportionate significance as a metric of economic progress. In his criticism, Sombart correctly identified a tendency in economic history up until the present, whereby overemphasis on long-distance trade can contribute to misleading narratives of development and change.Footnote 77

Without readily available commercial data, the historical economists concentrated on the expanding material ambit of infrastructure. Here, at least, was something that could be both counted and depicted. One author of a German overview of world commerce supported this notion, writing in 1895 that ‘the estimate of the volume of goods set into movement by trade provides only imperfect insight … As our force of imagination is limited by what we can perceive, we already lack the means of measuring its size. Much more instructive is a look at the spatial and material expansion experienced by commerce through modern means of Verkehr.’Footnote 78 The tangibility of infrastructure made it more accessible for scalar extrapolation to a lay audience. Cartography, as one scholar notes, is an effective means of ‘visualizing spatial relations that are too large and complex to be taken in undigested’.Footnote 79 Though picturing vast quantities of goods might strain the imagination, one might more easily link the lines over one's head on the street to those traced across continents and oceans on a map.

Maps and atlases were the most important technologies for representing ‘the world as an ordered totality’ in the nineteenth century.Footnote 80 They illustrated vividly the era's focus on infrastructure. Statistical economists contributed data and occasionally commentary to them. Following the representation of Verkehr in German atlases, which set the standard internationally for the period, shows how maps changed as networks of communication and commerce expanded. Maps first transformed in the nineteenth century from the early modern representation of landmasses and waterways overlaid by a grid of meridians to a new emphasis on ‘contextuality and relationality of space’, including vertical stratigraphical perspectives.Footnote 81

German cartographers were pioneers in the thematic maps portraying these new spatial relationships. Heinrich Berghaus created the first atlas of thematic world maps in 1848, assembled with research material from the globetrotting naturalist Alexander von Humboldt.Footnote 82 Berghaus's atlas was not only significant for German-speaking populations but was also ‘immediately internationally popular’, according to historians of mapmaking, and ‘set a new standard for the depth, coverage and very meaning of cartography’.Footnote 83 One of its innovations was depicting isotherms and trade wind currents, pioneering techniques that were imitated internationally.Footnote 84

In early editions of Berghaus's atlas, only the natural features of winds, magnetic flows, and isotherms linked the world's continents.Footnote 85 Human Verkehr made its first appearance on the meteorological maps in 1869 in the form of sea routes, railways, and telegraph lines, alongside an inset map of climate charts.Footnote 86 The first edition of what would become the most popular German-language atlas – and to which Juraschek would contribute commentary – was Karl Andrees Handatlas (1881), itself modelled on Berghaus. It included a similar map of ‘world Verkehr and ocean currents’, with an inset of global topography.Footnote 87The Times atlas (1897) published by the London newspaper, based on Andrees Handatlas, included a similar map, demonstrating the international influence of Berghaus's designs.Footnote 88 In these cartographic representations, routes of traffic for goods and humans existed alongside natural forms of wind and climate.Footnote 89

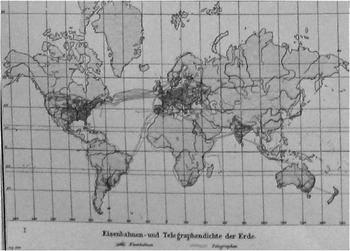

In an important change at the end of the century, the ocean currents vanished from the world map, leaving only commercial sea routes; an inset map of world railway and telegraph networks replaced the map of topography (see Figure 1).Footnote 90 By the early twentieth century, ‘commercial routes’ and ‘commercial highways’ crossed oceans and landmasses on world maps, while currents and winds melted away.Footnote 91 Nature had vanished entirely, to leave only manmade routes as the webwork of the world economy.Footnote 92

Figure 1 ‘Concentration of railways and telegraphy on the earth’. Source: A. Scobel, Andrees allgemeiner Handatlas, 4th edn, Bielefeld: Velhagen & Klasing, 1899.

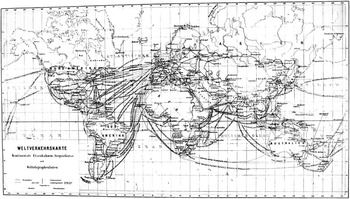

Such world maps could, and did, provide fodder for competition between states. A subsequent edition of Andrees Handatlas (1907) included a graphic representation of the territorial possessions of each empire and separated the telegraphic lines out by colour, based on national ownership, thus playing into inter-imperial rivalries.Footnote 93 Yet, while the panoramic vision of the world economy contained the possibility for zero-sum comparison, one could also interpret it as symbolically supporting free trade arguments about interdependence. The single latticework suggested a shared reliance on the wires and rails linking distant places. The ‘Map of world Verkehr’ included in a 1913 book was one of many that portrayed the world primarily in terms not of sealed-off and stable territories of terrestrial administration but of interstitial flows of information, people, and goods (see Figure 2). The map's accompanying text made its message explicit: ‘Our textile factories use wool from Australian sheep and the fabric that comes from the loom finds its way to distant parts of the world. The most distant countries are linked through an ever denser network of economic connections.’ The authors argued that these relationships created ‘a world economy in the sense that production and consumption have reciprocal effects and the cultural products and progress of every country and its economic and political circumstances have deep corresponding effects far beyond its borders’.Footnote 94

Figure 2 ‘Map of world Verkehr’. Source: C. Merckel et al., Der Weltverkehr und seine Mittel, Leipzig: Otto Spamer, 1913.

The German economist Richard van der Borght wrote in 1894 that the ties of Verkehr meant that ‘dependency is mutual and disruption in one country will soon be felt in the other’.Footnote 95 Maps of communication and trade depicted a state of globalization in which currents of information, people, and objects replaced national borders. Sometimes maps were used alongside arguments for acknowledging and maintaining interdependence. When seen in the mirror of trade statistics and the map, the world economic organism seemed to rely on long-distance commerce to survive. Borne out of the constraints of statistical data-gathering, the primacy of distance became a structuring feature of the historical economists’ concept of the world economy.

World economic statistics, often literally accompanied by world maps, presented a world of goods moving along vectors of trade. But this material vision of a world of flows was challenged by the rise of finance and a new optic that dematerialized the world, exchanging broad spatial flows for the study of social reality in ever smaller units of time measured in the medium of price.

Seeing like a stock market

In the winter of 1904–05, the statistics seminar at the University of Vienna devoted itself to the question of identifying what exactly ‘the world economy’ was. After all, the professors said, it was:

still very undefined in scholarly literature and public discussion. One minute the ‘world economy’ is the highest stage of development of the national economy, whose earlier stages were the village economy, the city economy, the territorial economy and the state economy (Schmoller). The next minute, the world economy as a particular kind of total economy is denied and the word only has meaning as a metaphor, intended to help express the sum of the conditions of Verkehr between nations or even the individual economies within diverse nations.Footnote 96

The two professors in charge were direct heirs to Neumann-Spallart. The first, Karl Theodor von Inama-Sternegg, had participated actively in founding the International Statistical Institute in 1885, and became its president in 1899.Footnote 97 He was also a member of the Verein für Sozialpolitik and co-directed its meeting in Vienna in 1894.Footnote 98 The second was Juraschek, who had taken up the authorship of the World economy surveys after Neumann-Spallart's death.Footnote 99 Among the seminar's participants were two students who would give answers very different from the panoramic perspective and organic metaphors of the eminent statisticians. The seminar reports of the twenty-one-year-old Joseph Schumpeter and twenty-three-year-old Ludwig von Mises, summarized in the journal of the Austrian Central Commission of Statistics, were among the first publications of their respective careers and provide insight into the competing versions of the world economy concept around 1900.Footnote 100

The explosion of financial activity in the last decades of the nineteenth century had directly affected how mainstream economists understood the world economy. The core difference lay in the marginalist economists’ focus on time rather than space, and their concentration on the site of exchange rather than an all-inclusive overview of economic conditions. Against the historical economists’ omnivorous, sometimes diffuse, focus on the expansion and evolution of infrastructure and institutions, marginalist economists concentrated exclusively on the formation of price. In contrast to the organicist understanding in which ‘the railways are the veins of the world economy and the telegraph lines are its nerves’, they proposed microscopic attention to the dynamics of supply and demand on the world's markets.Footnote 101

Historical economics had remained remarkably untroubled by the expansion of financial activity in the late nineteenth century despite (or because of) the serious challenge it posed to their model. The dematerialization of financial exchange eluded the materialist forms of representation captured in maps of communication and trade. More importantly, it appeared to contradict the core conception of historical economics that forms of production and exchange developed in concert and complementarity with state and legal forms.Footnote 102 The Austrian economist Wilhelm Rosenberg wrote in 1901 about the challenge to received economic wisdom presented by the bourses: ‘while it is claimed that commerce only blossoms, in general, under the secure, timely influence of a judiciary, stock market trading has made such rapid, visible progress in spite of the hostile attitude of law and even judiciary that the bourses seems to dominate today's economic conditions in the advanced countries’.Footnote 103 The apparently antagonistic relationship between exchanges and governments refuted historical economists’ notion of synchronicity between state and economic development.

While stock market activity had been robust since the early nineteenth century, a series of spectacular crashes, the emergence of single world prices for a group of standardized products (including grains, coffee, sugar, and cotton) in the last third of the century, and the expansion of futures trading in the late 1880s (described in Engel's contribution to this issue) made finance a matter of public debate.Footnote 104 As the newspaper market boomed around 1900, financial information was delivered daily to cafés, kiosks, and mailboxes. In 1894, Max Weber referred to the ‘dry numbers’ printed ‘at the back of newspapers’ whose ‘change in the course of a year signifies the flourishing and decline of whole branches of production, upon whose situation hangs the happiness or misery of thousands’.Footnote 105 The feuilletonist Maximillian Harden captured the zeitgeist when one of his liberal characters in a comic scenario said in 1901, ‘You talk about politics. Read the price sheet! That's the most important document for the history of today and tomorrow.’Footnote 106 Franz Eulenberg, a student of Schmoller's, confirmed this sentiment in 1906. After pointing out that ‘capitalism has interwoven all individual economies into the general movement of the world economy’, he observed that political events such as the Morocco Incident (1905–06) or even the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05) barely affected ‘the price level’.Footnote 107 It seemed possible that all useful knowledge about the world could be drawn purely from economic data.

Focus on the micro rather than the macro was fundamental to the marginalist contrast with historical economics. Most importantly, they shifted their object of study from the economy as a whole to the price-creating actions of individuals.Footnote 108 This approach was typified in Schumpeter's first book, from 1908. Rather than conceiving of the economy as an organism, which necessarily ‘grew’ institutions as countermeasures to the market, he followed the father of Austrian marginalist economics, Carl Menger, by seeing the economy at the micro-level, as ‘a result of economic actions and the existence of individuals’.Footnote 109 As a young employee of the Austrian Press Department, one of Menger's responsibilities had been tracking stock prices in the newspaper, prompting him to wonder early on about the gap between scholarly theories of prices and those of ‘experienced practical men’, an inquiry he handed down to his followers.Footnote 110 The ‘primacy of observation’ in creating scientific data was consistent with theories of logical positivism current in Vienna, as well as the general desire of neoclassical economists to reproduce the scientific authority of physics.Footnote 111 This perspective took the world economy from a metaphor backed up by imperfect aggregate statistics to a quantifiable site of calculation.

Thus, when Schumpeter spoke of the ‘world market’ in his 1905 presentation, he meant the specific place where one could see the value of commodities being determined most clearly through the act of buying and selling: he meant commodities exchanges. As he put it:

a ‘world price’ requires a ‘world market’. In our empirical investigation, we are not concerned with the general category of the ‘world market’, but rather with concrete spatial centres of price formation, with concrete factors of power and interest groups. The world market for an article can be found very easily: for example, London is simply ‘the world market’ for a whole series of articles.Footnote 112

Prices determined at the exchanges had ripple effects outwards. As Schumpeter said, ‘the London prices set the standard for many commodities in all of Europe, indeed in all the world’. The author of the seminar report, probably Inama-Sternegg, noted that the infrastructure of ‘post, rail and telegraph’ meant that ‘the price of a globally traded commodity is set by the world market price even in remote corners of the earth’.Footnote 113 Yet, even as communications infrastructure created the conditions for the world economy, the site of study shifted from the globe to the floor of the commodity exchange.

Schumpeter's emphasis on the world market price followed that of his mentor Böhm-Bawerk and the pioneering marginalists Alfred Marshall and Léon Walras (as well as the German historical economist Gustav Cohn discussed in Engel's article in this issue). For marginalist economists, the most important indicators of a world economy were the worldwide convergence of commodity prices and the consistency of stock prices at different locales.Footnote 114 The apparent ‘informational consistency’ produced by the telegraph and the telephone allowed for arguments about perfect competition in an ideal-typical space of the market ‘characterized by an absence of institutional structures’.Footnote 115 Relying on analogies to physics, Walras said that one must ‘always suppose a perfectly organized market in respect of competition’ in the marginalist method, ‘just as in pure mechanics one at first supposes frictionless machines’.Footnote 116 Paradoxically, assuming the existence of perfect communication allowed the infrastructure of communication itself to fade from the attention of marginalist economists.

Schumpeter had pointed out a second reason for his focus on the bourse in a presentation in the statistical seminar the year before. He argued that ‘economic tendencies are transformed into reality more quickly and purely in stock exchanges … than in other places, where habit, ignorance and other conditions limit the efficacy of economic principles’.Footnote 117 The stock exchange, in other words, was the site where people were most likely to act as pure incarnations of homo oeconomicus, the constructed subject around which marginalist economists built their analyses.Footnote 118 The bourses were important as both producers of information about the real existing economy and the basis for models of the economy as such.

The chronophotograph and the price movement

Schumpeter began writing his first book, The nature and essence of theoretical economics, following a brief period studying under Schmoller after finishing his doctorate in Vienna in 1906. He aimed to explain the marginalist method to German historical economists who were sceptical of its abstractions and its disavowal of economics as a tool for guiding policy in favour of economic knowledge for its own sake.Footnote 119 In his book, he laid out the neoclassical method programmatically and attacked historical economists directly for spreading

platitudes about the importance of transportation … that brings markets close to one another and is essential to the formation of the world economy, etc. They expound on how postal, telegraphic, and telephonic communication is an integral, indispensable technological element in the form of the modern economy … And for all this we are usually given data and overviews of historical development. What is the scientific value of this? Everyone knows it well already.Footnote 120

Schumpeter dismissed most of the historical economists’ contributions to the study of the world economy with a single stroke. He even singled out the potential distortions of statisticians directly, saying that ‘they don't merely report on what they find, they shape their findings as well, and by shaping their data they transform it’.Footnote 121 What did the marginalist economists suggest instead? Schumpeter proposed that they start small: ‘our sole endeavour is to explain what the price is and draw certain laws of movement from it’.Footnote 122 Although still adhering to equilibrium models that saw the economy as a totality, he advocated abandoning the synoptic, synthetic overviews of the historical economists.

For marginalists, the global structure of communication and transportation became externalities, which were not included in the formal analysis. Schumpeter followed Menger when he wrote that ‘it is a statement as fundamental as it is paradoxical: Should the entity of the national economy be of no concern to the national economist? We do not hesitate to answer in the affirmative.’Footnote 123 Because the goal was only to study price formation, marginalists set narrow borders to the frame of study. Further investigations ‘belonged to the area of sociology’ and not economics. Schumpeter discarded the categories of ‘national wealth’, ‘national income’, and ‘social capital’ because of the unreliability of economic data-gathering not based on direct observation of price formation between individuals.Footnote 124 In 1908, he coined the enduring term ‘methodological individualism’ to describe the marginalist approach.Footnote 125 From this point hence, one should see the world economy through the actions of the individual.

The insistence on disciplinary precision prompted Schumpeter's rejection of the panoramic optic. ‘The Historical School tells us nothing new’, he wrote, ‘when they insist that every economic event is the result of diverse influences, complicated processes.’Footnote 126 Any attempt to find causality through the aggregation of factors was destined to fail, because ‘every causal chain can be countered by another and fitting examples can be found to argue the general applicability of either’.Footnote 127 Instead, Schumpeter presented a pragmatic approach to studying the world economy: measure what you need to, and measure it with exactitude.

Rather than the panorama, Schumpeter offered the metaphor of the camera in his 1908 work. ‘Visually’, he wrote, ‘one can put our approach in the following sensory terms.’ Through the observation of price, ‘we are taking, so to speak, a snapshot of the economy (eine Momentphotographie der Volkswirtschaft). The picture shows everything at a specific stage in apparent calm. We are aware, however, that in reality there is the liveliest movement and we want to describe some of it.’Footnote 128 Observing price changes over time turned the snapshot into a picture in motion while isolating one particular factor. As he wrote, ‘if we loosen the spell and bring part of the image to life, then we hold another much larger part immobile’.Footnote 129 Instances of relative scarcity and abundance were being photographed within a model of general equilibrium over a short period of time: ‘our construction of the new instantaneous image should limit itself to the variations in the quantities of goods in possession of the individual economic subjects’. The only means of measuring these quantities was by reading the price signals of the market, as recorded in daily lists and the continual output of the stock ticker.

The camera metaphor was not incidental for Schumpeter. He elaborated on it in three separate sections of the 1908 work, and referenced ‘images’ and the ‘static apparatus’ to describe his methodology throughout the book. In his later work, he would refer explicitly to the importance of ‘vision’ as the worldview with which economists approached their intellectual problem.Footnote 130 The metaphor resonated with other economists, too. Commentators, including Oskar Lange and Franz Oppenheimer, praised it and adopted it from Schumpeter.Footnote 131 It is still used today to describe the method of comparative statics, on which Schumpeter expanded in his future work on evolution and economic development.Footnote 132 In its implicit prioritization of social phenomena, it vividly recalled Friedrich Engels's denunciation from 1890 of the vision of the ‘money market man’ who saw the world as if through a camera obscura, perceiving changes in industry and labour only through the ‘inverted reflections of the money and stock markets’ and mistaking them for reality.Footnote 133 Yet what Engels condemned as a misapprehension of the world, Schumpeter praised as the only reliable way of perceiving it. Hilferding, who was in Böhm-Bawerk's seminar with Schumpeter in 1905–06, wrote in 1910 that ‘speculation creates a price for every instant of the year’.Footnote 134 For marginalist economists, the record of these prices became a chronicle of the world at large.

What was the social context for the shift from the cartographic to the cinematographic imagination? While Neumann-Spallart and other historical economists grew up in a world of still photographs and maps, Schumpeter, born in 1883, and living in Vienna since the age of ten, was part of the first generation to come of age with devices that used photographs to simulate motion – and the expanded field of visual representation and calculation that came with them. Thomas Edison's kinetoscopes were common at Viennese fairs in the 1890s; Ottomar Anschütz's Elektrischer Schnellseher depicting the isolated motions of animals and humans was first demonstrated in Vienna in 1890 (see Figure 3); and a representative of the Lumière brothers presented the first series of motion pictures on film in the city in 1896.Footnote 135 The ‘thumb cinema’ flipbooks of Max Skladanowsky were also widely distributed examples of the snapshot in motion.Footnote 136 The first permanent cinema opened in Vienna in 1905, the year before Schumpeter finished his doctorate and moved to Berlin and London, where film was even more commonly available.

Figure 3 Ottomar Anschütz's Elektrischer Schnellseher, c. 1890. Rotating still photographs viewed through a single aperture simulated motion. The observation of movements captured in discrete consecutive moments recalls Schumpeter's description of the method of comparative statics. Source: C. Francis Jenkins, Animated pictures, Washington, DC: H. L. McQueen, 1898, p. 14.

Early film and photography were intended for scientific research as much as for entertainment, a tool of the laboratory as much as a medium of diversion. A report on one proto-cinematographic device in an Austrian journal in 1899 advertised that ‘it demonstrates and analyses every movement, every step in dancing, fencing, wrestling, boxing, gymnastics. It will be a living handbook of anatomy and the physiology of movement.’Footnote 137 Schumpeter's description of the neoclassical method recalls these pre-cinematic devices. Yet rather than cinematography, at which it only hinted, Schumpeter's metaphor was most reminiscent of the pioneering ‘chronophotographic’ studies of Eadweard Muybridge, Étienne-Jules Marey, and Anschütz, which captured the movements of animals and humans in isolated frames in order to understand laws of mechanics and the mysteries of gait.Footnote 138 The photographers used different methods to isolate the relevant factors. They filmed their subjects against a black or gridded background, while Marey also clothed his in bodysuits with thin white lines to capture motion better (see Figure 4).

Figure 4 Black bodysuits with white lines isolated moving limbs for scientific study in Marey's chronophotographs. Source: Étienne-Jules Marey, Die Chronophotographie von E.J. Marey, Berlin: Mayer & Müller, 1893, p. 12.

The techniques of chronophotography had clear echoes in Schumpeter's text. He employed multiple photographic metaphors in a single passage, writing of his own ‘isolation method’ that ‘one can never put a phenomenon in the right light and fully understand it if one does not picture it separately, and eliminate the factors that might cloud the image’. In this sense, his ‘snapshots’ did not evoke casual off-the-cuff photography but rather the deployment of the camera in controlled laboratory-style conditions. Like the chronophotographers, he removed all extraneous variables to track the motion of a single indicator.

Although Muybridge's and Marey's photos were visual artefacts, they sought to erase space as the physical body offered itself up for analysis only in terms of its variation over time. Muybridge's photographs were a ‘vision compatible with the smooth surface of a global marketplace and its new pathways of exchange’.Footnote 139 Schumpeter's metaphor, too, suggests an affinity between the medium of film and the process of price formation. Both created an impression of fluid movement by distributing data evenly across discrete but connected moments.Footnote 140 As a record of human life, the price chart resembled Marey's chronophotograph much more closely than a world map of trade. If marginalist economists ‘forgot history’, then they forgot space too, dispensing with the multiple, entangled causalities of the built world of Verkehr for the single site of price production measured in units of time.Footnote 141

Conclusion

Two competing ways of seeing the world economy crystallized around 1900. The panoramic vision of historical economics relied upon statistics and geography and emphasized volume and space. It faced a challenge from the chronophotographic vision of the marginalist emphasis on price and time. This new methodology threatened to invalidate the world economy as an object of study altogether, except in its manifestation as price movements on stock and commodities exchanges. When the concept of the world market eclipsed the world economy, the state disappeared and individuals appeared to encounter one another as buyers and sellers unmediated in a shared global space. The theories – and distortions – of both schools were the product of their chosen metaphors, means of measurement, and sites of calculation. Trade statistics and cartography fostered the primacy of distance for historical economists, while marginalist economists’ fixation on commodities and stock erased the state except as an obstacle to ‘the market’, the latter being a methodological conceit that acquired normative power with time.Footnote 142

The shift in attention from the panorama to the price point had consequences. We can see this clearly in the seminar report of Schumpeter's classmate Ludwig von Mises, who later became one of the most prominent representatives of free-market liberalism. Titled ‘The repercussions of the world economy on the structure of social policy’, Mises's report concluded that European ‘export industries were threatened by worker's protection laws’. Recent legislation in Europe to block traffic in child labourers, regulate night work for women, and protect workers from white phosphorous was, in fact, dangerous for Europe because Japan and China had not signed the legislation. This fact, he said, had ‘drawn our attention to the great danger that Asian competition presents for the future of European social policy’.Footnote 143 If Asian states continued to industrialize, the European nations would face a stark choice: preserve the free trade world economy or continue developing the social state. They might not be able to do both because, as he put it, ‘doubtlessly … the industrial states will be ever more reliant on the Asian market in the future …. English and German workers may have to descend to the lowly standard of life of the Hindus and coolies to compete with them.’Footnote 144 Viewing the world economy through the lens of the price point while assuming free competition, Mises could only foresee a convergence of factor prices downwards to the market-clearing rate. If there was one commodity price, there would eventually only be one wage too. Seeing the world economy as a single market for goods and labour aided in creating formidable rhetorical tools for disciplining the demands of workers for a nascent social state.

The current scholarship on the first wave of globalization reproduces this division between the schools of historical economics and marginalism. Some historians follow the marginalist school by seeing commodity price convergence as the most important indicator of nineteenth-century globalization. Others criticize this perspective for ignoring the role of states, institutions, and coercive practices such as slavery and colonialism.Footnote 145 Echoing the fascination of historical economists with networks and spatial extension, these historians propose a focus on the interplay between increase in international trade, international infrastructure, and a global consciousness.Footnote 146 While scholars have recognized the ‘methodological nationalism’ they inherited from the social sciences of the nineteenth century, they have been less attuned to the ‘methodological globalism’ that came with it.Footnote 147 The vision of a natural planet overlaid by manmade infrastructure and transformed into a ‘world economy’ is as much an inheritance of the nineteenth century as the categories of nation and empire. We see the world economy today, in part, through lenses prepared over a century ago. The political consequences of this fact remain understudied.

Quinn Slobodian is Associate Professor of Modern European History at Wellesley College. He is the author of Foreign Front: Third World Politics in Sixties West Germany (2012).