In December 2017, the government of Canada refused to support the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) resolution that rebuked the Trump administration's recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel. Whereas an overwhelming number of countries, including virtually all of Canada's key allies, voted in favour of the resolution, Canada was among 35 countries that abstained from voting. A spokesperson for Foreign Affairs Minister Chrystia Freeland and Canada's ambassador to the UN, Marc-André Blanchard, issued brief statements expressing “disappointment” at what they said was a “one-sided” resolution (CBC News, 2017), while Prime Minister Justin Trudeau added that Canada's abstention signalled a desire to stay above “political games” (Marquis, Reference Marquis2018). The decision was, and remains, controversial. For some, it was a desperate effort by the Trudeau government to curry favour with President Trump and soften his position on Canada-US trade. Others saw it as hypocritical in light of Trudeau's pronouncements on international law, human rights and on the necessity of reversing the anti-UN foreign policy of the government of his Conservative predecessor, Stephen Harper.

Canadian foreign policy (CFP) scholarship supplies much-needed context for understanding such controversies. In their study of Canada's voting record in the early 2000s at the UN Commission on Human Rights and the UN Human Rights Council, Binette and De Courval (Reference Binette and De Courval2014) find that Canada consistently takes a pro-Israel stance, alongside the US and against its Western European allies. Looking at UNGA voting, Musu argues that Ottawa positions itself between Europe and the US on general issues but closer to the US on Middle East issues, “for example abstaining on a resolution where Washington voted against, or voting in favor where Washington abstained” (Reference Musu2012: 70). Seligman (Reference Seligman2016) concurs, adding that Canada's pro-Israel voting began not under Harper but under the Liberal government of Paul Martin (see also Musu, Reference Musu2012: 71; Zahar, Reference Zahar, Hampson and Saideman2015: 39).Footnote 1

Canada's voting behaviour in the world's most important deliberative body in fact allows us to answer several long-standing CFP questions: Who, exactly, are Canada's like-minded partners? How has Canada's voting pattern changed over time, and on what issues? Have Canadian positions become more pro-US in recent years? Do the UK and France still count as Canada's traditional friends and allies? How do the voting positions of the Liberal governments compare to those of their conservative rivals, the Progressive Conservative party and the Conservative party? And is Ottawa more likely to stand with Washington when the Democrats are in power? We address these questions with a statistical analysis of Canada's UNGA voting record from 1980 to 2017—that is “from Trudeau to Trudeau.” Building on the assumption that observing a pair of member states voting consistently in unison reveals the similarity of foreign policy preferences (also known as “interest similarities” or “affinities”), we analyze this record using two techniques: bilateral affinity, which is well established in international relations (IR) scholarship (Bailey et al., Reference Bailey, Strezhnev and Voeten2017; Voeten, Reference Voeten2013), and principal component analysis (PCA), which is new. Agreement between them is meant to provide greater confidence in our analysis, the limitations of said measures notwithstanding (Bailey and Voeten, Reference Bailey and Voeten2018).

Our main findings are as follows. First, Canada's voting in this period tended to primarily track with the positions of Western European states rather than with US foreign policy positions. This holds true for major European powers, and especially Germany, as well as for select middle powers, such as the Netherlands or Norway. Also high is Canada's voting affinity with the UK, France and Australia. Next, although we find no evidence that Canada's voting is aligned more with the US during the reign of conservative governments in Ottawa, we do identify a sharp pro-US turn in the Harper years, both overall and on the votes cast on resolutions pertaining to the Middle East. Next, while our analysis confirms that partisanship does not matter, we also find that Harperism does matter, and not least because the Harper-era voting pattern appears to continue under Justin Trudeau. Last, we find no evidence that Ottawa tracks with Washington's positions when the Democrats are in power, whether in terms of a Democratic presidency, a Democratic Congress, or both. Together, these findings provide a helpful assessment of continuity and change in Canada's interests, values and foreign policy habits.

We begin by reviewing the relevant knowledge claims from the CFP literature, from which we distil a set of testable hypotheses. We then discuss the measures and methods used, their limitations, and how aspects of our analysis differ from previous studies. This is followed by a presentation and discussion of the findings. By way of conclusion, we evaluate the implications of this study and identify further research areas.

Partners, Patrons, Peers

All states pay close attention to votes cast in the UNGA. For example, the US Congress mandates annual reports that compare the US voting record to those of other member states, with particular emphasis on the voting records of US allies and various regional groupings, thus identifying “a country's orientation in world arenas: where it stands, with whom it stands (at least in a UN context), and for what purpose” (US Department of State, 2018: 3). The US government uses this information to make policy, including policies that reward and punish, as can be seen in President Trump's threats to America's allies prior to the vote on the status of Jerusalem (CBC News, 2017). Such dynamics are naturally of great interest to students of US foreign policy. Two recent examples will suffice: Woo and Chung's (Reference Woo and Chung2017) analysis of the conditions under which the US “buys votes” with aid, and Bailey et al.’s (Reference Bailey, Lee and Voeten2018) brief on the relationship between Trump's international popularity and the propensity to vote in unison with the US.Footnote 2

UNGA voting analysis can likewise be used to shed light on Canadian foreign policy: Where do we sit, with whom, and for what purpose (Sokolsky, Reference Sokolsky1989; Molot, Reference Molot1990; Smith, Reference Smith, Sjolander, Smith and Stienstra2003; Roussel and Morin, Reference Roussel, Morin and Roussel2007; Black and Smith, Reference Black and Smith2014)? Taking a broad view of CFP scholarship, we can see that answers to these questions fall under three general rubrics: continentalism, Europeanism and imperialism (Paquin and Beauregard, Reference Paquin and Beauregard2013; Nossal et al., Reference Nossal, Roussel and Paquin2015; Massie and Vucetic, Reference Massie and Vucetic2017). Continentalism stresses Canada's security and economic dependency on its behemoth southern neighbour, as well as shared continental values, and how all this leads Canadian governments to support US foreign policy goals. Glossing over a considerable heterogeneity of the theoretical approaches and posited causal mechanisms (among others: MacMechan, Reference MacMechan1920; Innis, Reference Innis1952; Sutherland, Reference Sutherland1962; Clarkson, Reference Clarkson1968; Warnock, Reference Warnock1970; Crosby, Reference Crosby1998; Welsh, Reference Welsh, Cooper and Rowlands2005; Bow and Lennox, Reference Bow and Lennox2008; Gindin and Panitch, Reference Gindin and Panitch2012; Massie and Roussel, Reference Massie, Roussel, Smith and Sjolander2013; Vucetic and Tago, Reference Vucetic and Tago2015), we derive a hypothesis (H1) from this literature that Canada's voting record will be consistently similar with that of its foremost ally and largest trading partner or, one might argue, its patron.Footnote 3

Europeanism is our rubric for the argument that Canada's relationship with Europe significantly influences Canadian foreign policy positions—whether through shared values, economic ties, overdependence on the US or some combination of all three.Footnote 4 This claim is borne out by existing research on Canada's UN voting (Paquin and Chaloux, Reference Paquin and Chaloux2009; Binette and De Courval, Reference Binette and De Courval2014). It is also supported by constructivist insights on status and the role of “recognized peers” in international relations, as in Vucetic's (Reference Vucetic2017: 505) contention that Canadian foreign policy makers pay disproportionally close attention to the behaviour of certain midsized, wealthy, progressive and therefore “like-minded” nations of Europe. Based on this literature, we have reasons to expect Canada's voting in the UNGA to be similar to that of the following European states (H2): Denmark, Italy, Sweden, the Netherlands, Norway and (West) Germany. The sample is meant to capture a variety of knowledge claims concerning Canada's European connections in foreign policy: major powers and fellow G7 members (for example, Germany), as well as fellow liberal internationalist middle powers—including those standing outside the European Union (EU) (Norway) and outside NATO (Sweden).Footnote 5

Imperialism is a historical category, but here we use it to examine Canada's relationships to its putative mother countries, the UK and France, and these relationships’ individual and cumulative influence on Canadian foreign policy (see, for example, McLauchlin, Reference McLauchlin2017). We are particularly interested in the arguments involving two neologisms: “the Anglosphere” and “la Francosphère.” The former stands for an imagined and semi-institutionalized grouping of English-speaking empire-states whose influence on international order has been profound (Haglund, Reference Haglund2005; Vucetic, Reference Vucetic2011a, Reference Vucetic2011b; Mycock and Wellings, Reference Mycock and Wellings2019). One contemporary manifestation is the Five Eyes, often abbreviated as FVEY. Once a mere intelligence partnership of Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the UK and the US, this is now a network of networks covering a wide range of policy and operational areas in security writ large.Footnote 6 In the UN, Anglosphere identities manifest themselves in consultations groups that routinely discuss policy issues at the General Assembly and the Human Rights Council—the UN-speak for a group of Canada, Australia and New Zealand is “CANZ” (Gifkins et al., Reference Gifkins, Jarvis and Ralph2019: 4)—and, to a lesser extent, in UNGA voting (Vucetic, Reference Vucetic2011a).

Based on this literature, we can therefore expect to see Canada aligning itself not only with the US (following the continentalist rubric) and the UK (following the Europeanism rubric) but also with Australia (H3).Footnote 7 Along similar lines, if, as Massie (Reference Massie2013) has argued, la Francosphère exerts considerable influence on Canadian strategic culture, then we have good theoretical reasons to expect to see a high voting coincidence between Canada and France (H4). That said, and going back to the previous discussion, we can also interpret evidence of high voting coincidence with France as support for the Europeanist perspective (H2). For comparison, we also consider Canada's voting coincidence with its major hemispheric partners, Brazil and Mexico; with its long time Asian partner, Japan; and finally with China and Russia (formerly the Soviet Union), both of which tend to be framed as threatening to Canada (Massie and Vucetic, Reference Massie and Vucetic2017).

Moving on to the question of partisanship, the scholarly consensus holds that this factor matters only in limited circumstances (Bow, Reference Bow2008; Smith, Reference Smith2008; Gecelovsky and Kukucha, Reference Gecelovsky and Kukucha2008; Nossal et al., Reference Nossal, Roussel and Paquin2015). Taking this into account, we break down our analysis of Canada's voting similarities with the aforementioned states by government, comparing the corresponding voting records of the Liberal governments of Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and John Turner (1980–1984) to the Progressive Conservative governments of Prime Ministers Brian Mulroney and Kim Campbell (1984–1994) to the Liberal governments of Prime Ministers Jean Chrétien and Paul Martin (1994–2006) to the Conservative governments of Prime Minister Stephen Harper (2006–2015) to the Liberal government of Pierre's son, Justin (2015–2017). Next, as mentioned earlier, Seligman (Reference Seligman2016, Reference Seligman2018) has found that the Harper government's UNGA voting record tracked that of the Liberal governments of Chrétien and Martin on most issues, except on Israel/Palestine, where it was the Martin government that set the trend for both the Harper and the Trudeau governments. We consider Canada's voting affinity with Israel (H5)—that is, “Israelophilia”—from 1980 onward as well. We finally add nuance to the continentalist argument by taking into account the role of cross-national ideological affinity. If it is generally true that ideological congruence between and among governments and legislatures facilitates foreign policy coordination (Hofmann, Reference Hofmann2013; also see Blaxland, Reference Blaxland2006, on political “sine waves”), and if it is true that Canadian publics tend to align more closely with the Democrats on most issues (Martin, Reference Martin2012), then we might have reasons to expect that Canada's voting affinity with the US increases when Democrats are in the White House (H1a) and/or when the Democrats control Congress (H1b).

Research Design

To obtain dyadic affinity—also known as voting coincidence or voting alignment between a pair of states—we calculated the mean scores for Canada using the now-standard affinity index that captures similarity of voting positions of two countries in the UNGA (Bailey et al., Reference Bailey, Strezhnev and Voeten2017). It is calculated thus

where d is the sum of metric distances between votes by dyad members in a given year and Dmax is the largest possible matrix distance for those votes from UNGA voting data.Footnote 8 The index varies from −1 to +1, with −1 representing the least similar voting record (least similar interests) and +1 the most similar voting record (most similar interests). The record references only final plenary roll-call votes (decisions on full resolutions), but not preliminary votes (decisions on an operative or preamble paragraph of a resolution taken in advance of the final plenary action). An advantage of this approach is that it accounts for the complicated character of abstentions (“abstain” votes).Footnote 9 A disadvantage is that not all resolutions are subject to voting; most of them, in fact, count as consensus votes, also known as adoptions without votes (Lockwood Payton, Reference Lockwood Payton2010). This, in turn, is known to have ramifications for inferences based on affinity measures (Häge and Hug, Reference Häge and Hug2016; Bailey and Voeten, Reference Bailey and Voeten2018).

Our analysis covers 37 years of UNGA voting, from 1980 to 2017, enabling us to observe continuity and change under different structural conditions and across different governments in Ottawa. Following the earlier theoretical discussion, we analyze affinity scores twice, first in terms of general votes and then, depending on data availability, in terms of votes on the Middle East, Israel's home region. This allows us to evaluate two claims in particular. One is that partisanship matters only in specific foreign policy contexts or in specific periods, such as, for example, during Harper's tenure as prime minister. The other is the Trudeau government's claim that Canada's abstention from the 2017 Jerusalem vote merely followed “the policy of consecutive governments, both Liberal and Conservative” (CBC News, 2017). Throughout this analysis, we also manage a comparison of the Canada-US affinity scores under Democratic presidents in the White House (1980, 1993–2001, 2009–2017), as well as under a Democratic Congress (1980, 1987–94, 2007–2010), versus under their Republican equivalents.

To supplement the bilateral affinity-based analysis, we introduce a new method for measuring voting similarities: PCA. The main difference between the two is that the latter determines the clustering of states in the UNGA by the actual content of their votes rather than by their dyadic similarity, as in the former. Crucially, PCA is based on what we today call machine learning. That is, it takes the covariance matrix of all UNGA votes in a given period and ranks them in order of importance purely through mathematical deduction.Footnote 10 Thus, rather than projecting UNGA voting patterns on a preconceived ideological map (liberal/anti-liberal, West/East, North/South), as in the dyadic analysis, PCA allows us to observe those patterns from an atheoretical vantage point—that is, without imputing any meanings into the content of resolutions themselves.

Results

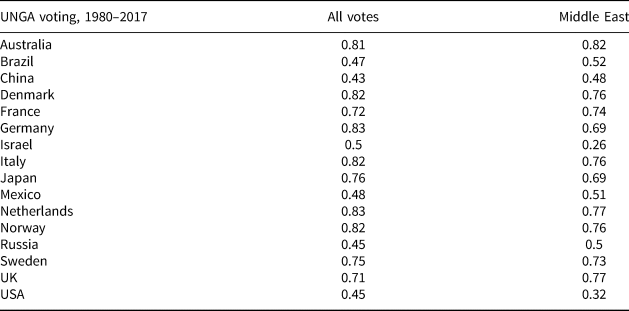

As the first column in Table 1 shows, Canada's overall voting record in the 1980–2017 period most closely tracks that of Western liberal democracies. The most similar records are those of Germany, the Netherlands, Italy, Norway, Denmark, Australia, Japan and Sweden, followed by France and the UK. Next comes a major gap in voting coincidence, falling below the score of .5, which is where we find Israel, Mexico, Brazil, the US, Russia and China. The pattern does not change when looking at the voting coincidences on resolutions pertaining to the Middle East only, shown in the second column. There, the highest affinities are with the middle powers and Europe's big three (Germany, France, the UK), and the biggest gap is with the US and Israel, whose average voting coincidence scores are both below .4.

Table 1 Affinity Scores for Canada

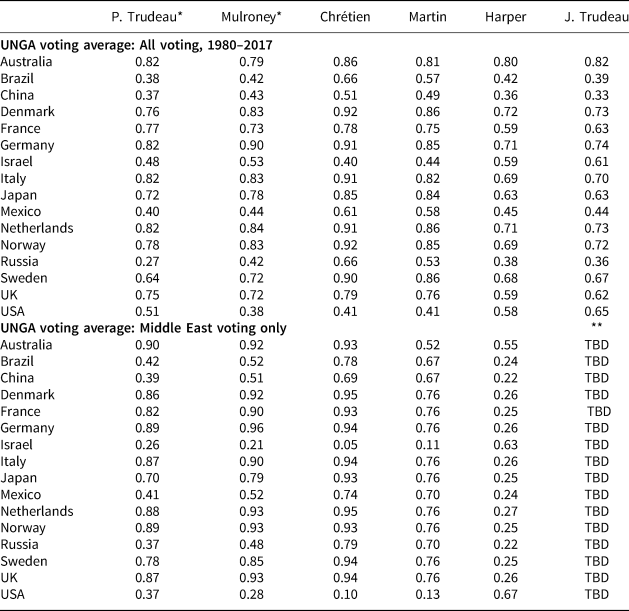

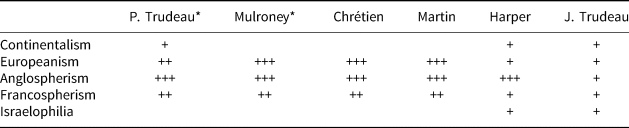

Table 2 breaks down affinity scores between Canada and the listed countries by government in power. The Harper era stands out in terms of its low scores with all but two countries: the US and Israel. Indeed, using the Chrétien years as the benchmark, the US and Israel scores receive respective increases of .01 and .04 under Martin and of .19 and .18 under Harper. The lower half of the table, which lists the scores for Middle East votes only, shows similarly slight increases under Martin but far more dramatic ones under Harper: .57 with both the US and Israel. Next, Canada's Conservative governments are generally no more pro-US and pro-Israel than their Liberal counterparts. Finally, though the Middle East voting data for the first two years of the government of Trudeau Jr. was not available for analysis at the time of this writing, we nevertheless see two things. First, relative to the Harper years, Canada's voting coincidences with its traditional partners and allies increased in all but one case (Sweden). Second, Trudeau fils’s figures on Israel and the US are still closer to Harper figures than to either Martin or Chrétien ones.

Table 2 Affinity Scores for Canada, by Government

* “P. Trudeau” also includes Turner's ministry; “Mulroney” includes Campbell's.

** Middle East voting data for “J. Trudeau” was unavailable at the time of this analysis.

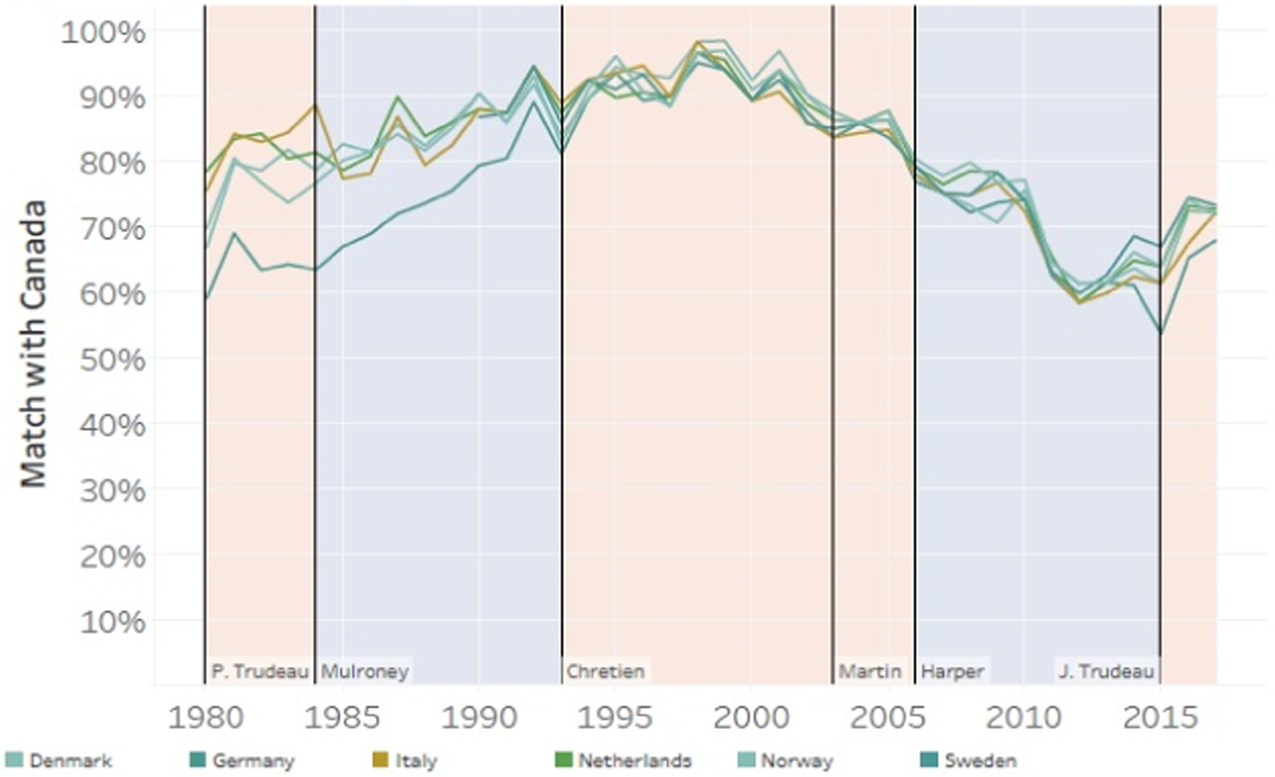

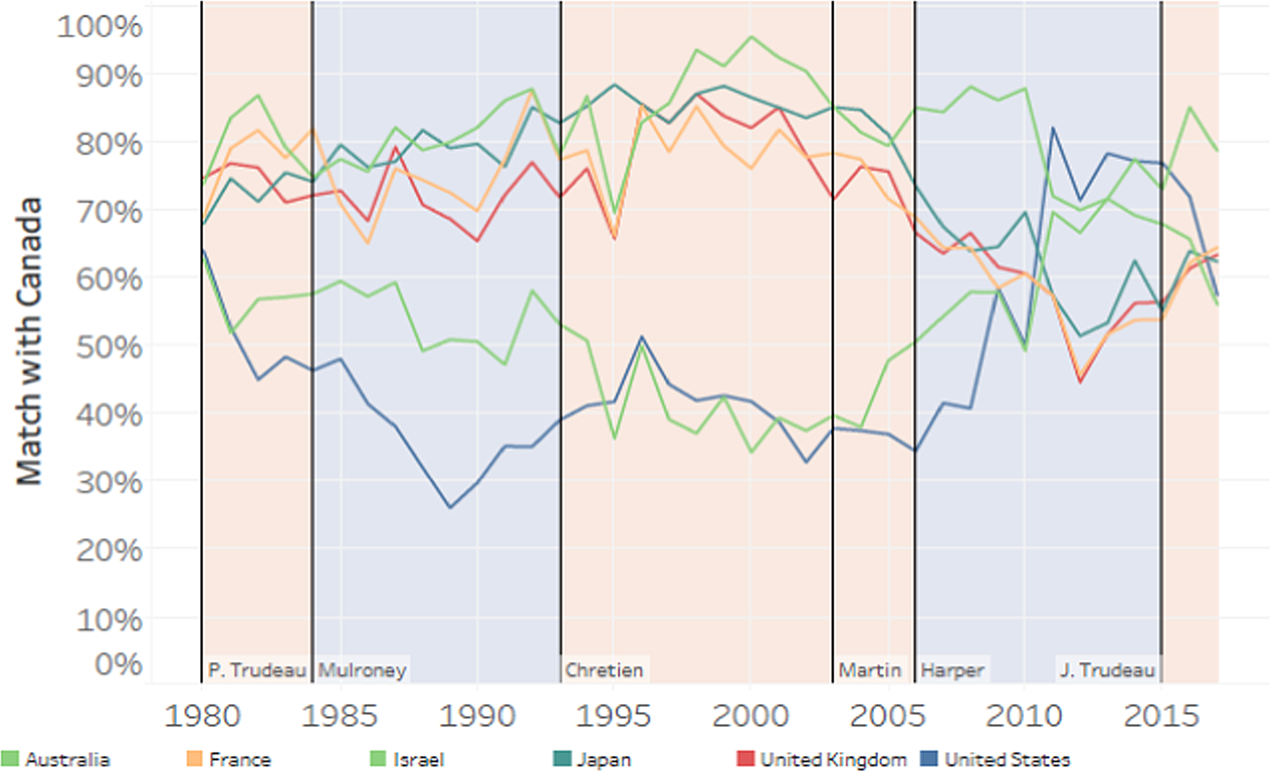

Figures 1 and 2 capture further aspects of the Harperist exception. In Figure 1, which is a graph of Canada's affinity score trajectories with six continental European states between 1980 and 2017, we see the voting coincidences peaking under Chrétien and then reaching its nadir under Harper. In Figure 2, we see consistent affinity score differences between the US and Israel, on the one hand, and France, the UK, Australia and Japan, on the other. The latter are lower than the former throughout until about 2009 (Harper's second minority government, 2008–2011), when we see a sharp pro-US and pro-Israel voting turns. A pro-Israel turn, albeit less sharp, is visible in the Martin years as well. Finally, under Justin Trudeau, Canada's voting record appears to be reverting to the historical trend, albeit not radically so. More on this below.

Figure 1 Canada's UNGA voting alignment with select European states

Figure 2 Canada's UNGA voting alignment with USA, France, UK, Israel, Aus. and Japan

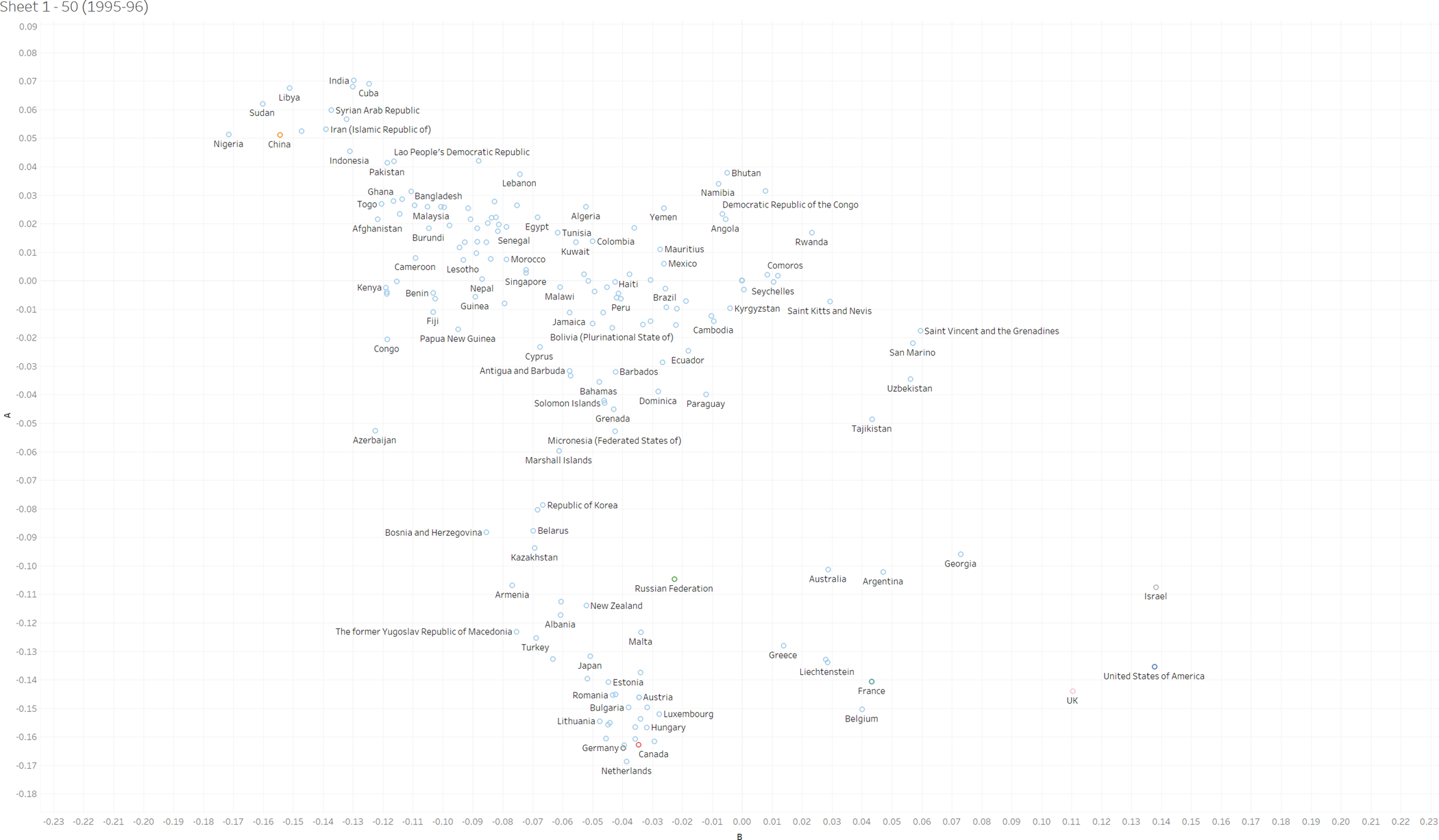

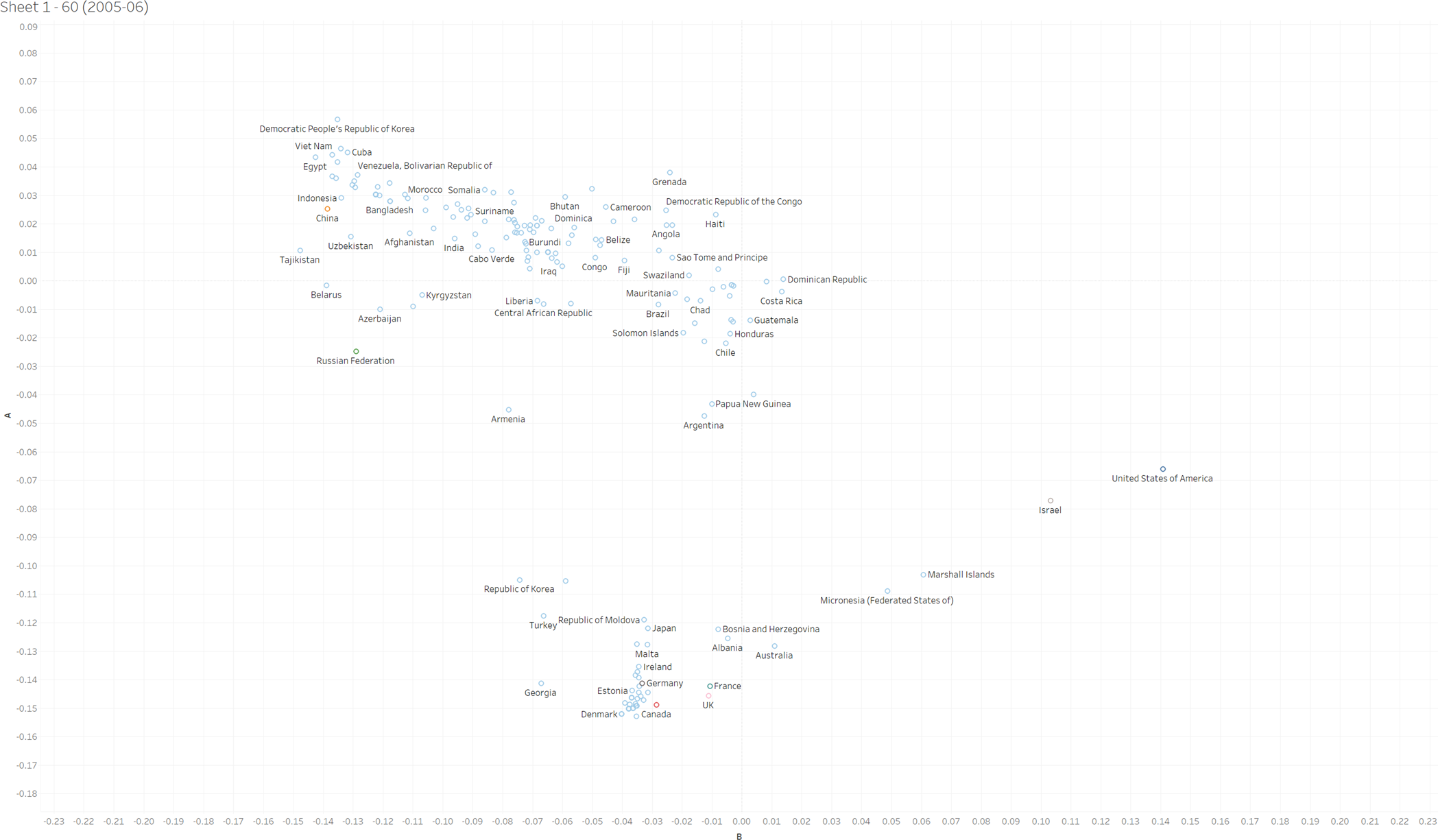

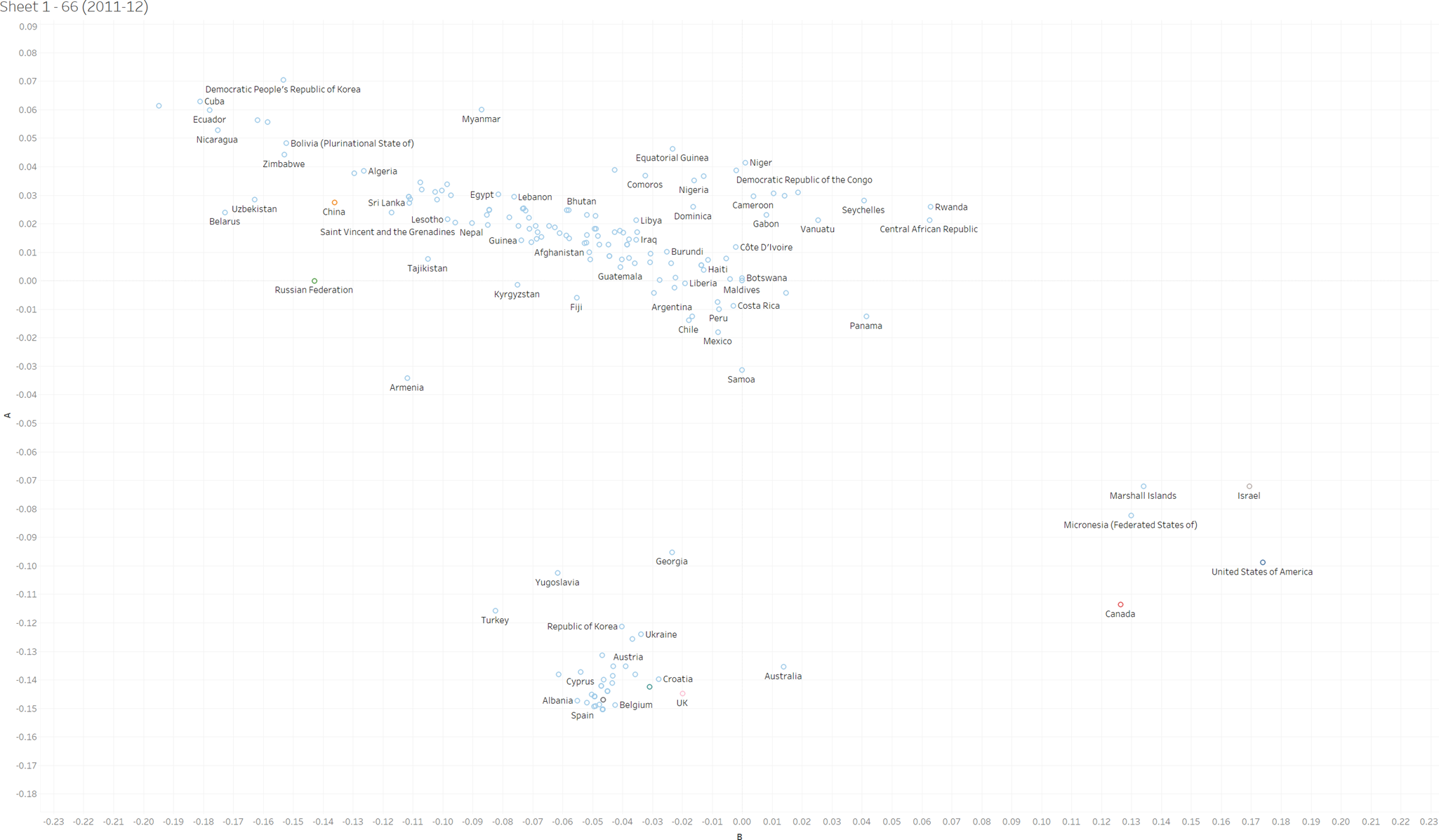

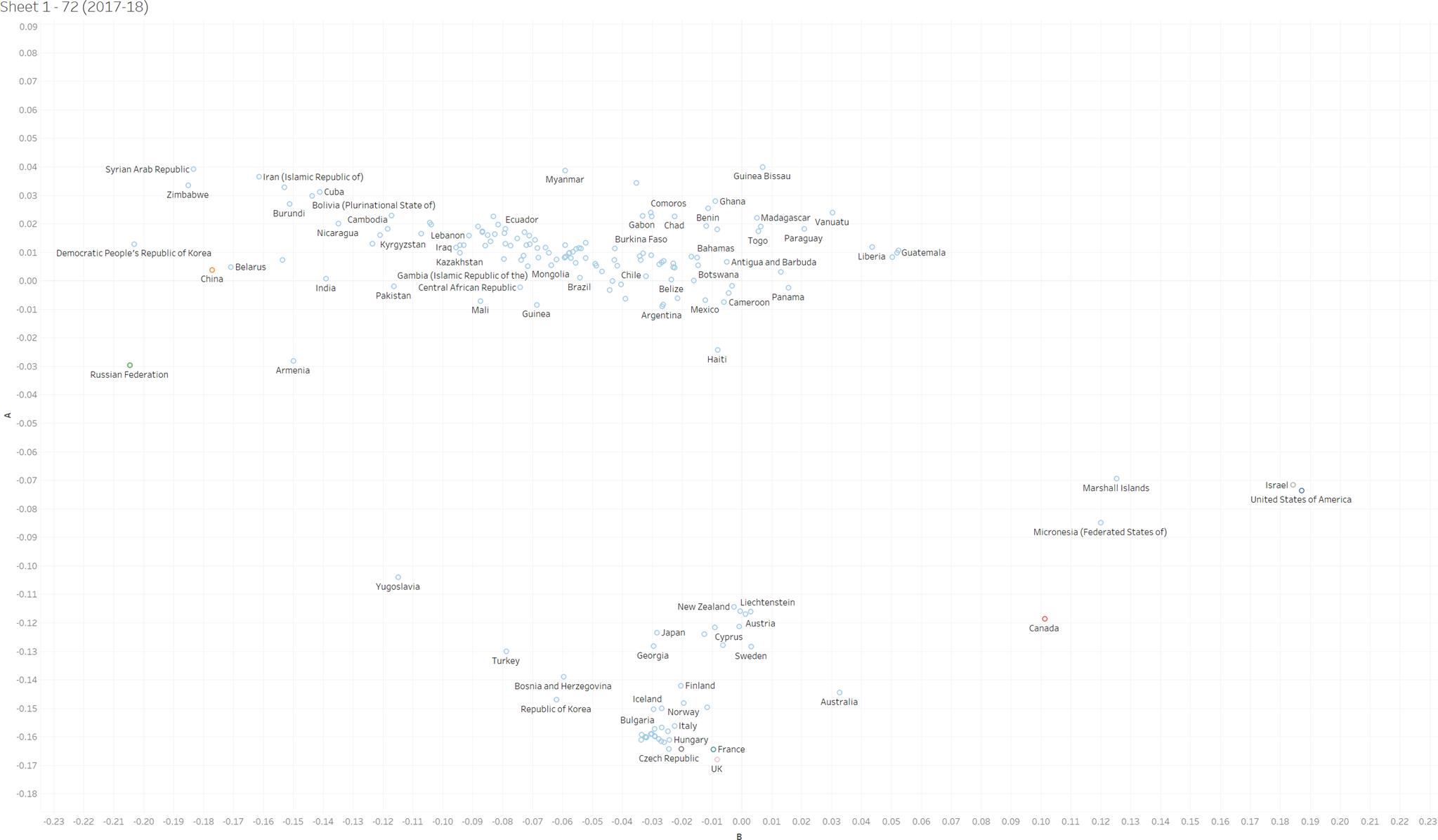

PCA results are very similar to the patterns identified through the dyadic analysis. To begin with, we find that 60 per cent or more of variability in UNGA voting in the entire period under study is explained with only two principal components. We illustrate this in Figures 3 through 6.Footnote 11 The general patterns are as follows. Voting during the Cold War mostly follows the logic of the two rival blocs, East and West, plus the logic of Third World nonalignment. In the post–Cold War period, we see three clusters. EU member states consistently flock together, and their voting pattern in most sessions closely tracked that of fellow liberal democracies such as Australia and Japan. The US anchors its own small cluster, together with Israel, Micronesia, the Marshall Islands and, uniquely in 1995–1996, the UK. Then there is the rest—a fairly large cluster of states that is internally diverse but visibly separate from the other two. Among cluster-to-cluster movements over time, the most notable is Russia's path: it mostly votes alongside the Western cluster in the 1990s but then slowly drifts away toward the rest in the 2000s. The path of Argentina, South Korea and a number of post-Soviet states goes in the opposite direction: after hovering as “in-betweens” in the 1990s, they all move toward the West in the 2000s.

Figure 3 Two-Dimensional Estimate of UNGA Voting, Session 50 (1995–1996)

Canada emerges as Western during and after the Cold War. In 1995–1996, for example, we see Canada joined up with the Netherlands and Germany, with Australia hovering closely nearby. Russia and France are almost equidistant from Canada on their respective axes, with the US more distant still on the x axis (Fig. 4).Footnote 12 A decade later, this picture does not change: Canada is closer to Denmark and Germany than to the UK and France, while being once again distant from the US and Israel (Fig. 5).

Figure 4 Two-Dimensional Estimate of UNGA Voting, Session 60 (2005–2006)

Figure 5 Two-Dimensional Estimate of UNGA Voting, Session 66 (2011–2012)

Much like the dyadic analysis, PCA captures a major shift in Canada's position toward the US cluster during the Harper ministry. The break becomes decisive after 2009, and the Harperist voting pattern stays the course until 2014–2015, which is when Canada begins to drift back to the Western cluster—a likely effect of Trudeau defeating Harper in the 2015 general election. Nothing suggests a U-turn, however. Figure 6, which is derived from the latest available data, places Canada in a gap roughly equidistant between Western and US clusters.

Figure 6 Two-Dimensional Estimate of UNGA Voting, Session 72 (2017 Data Only)

Discussion

Table 3 gives a comparison of theoretical expectations to empirical results derived from the dyadic analysis. The dominant theoretical perspective on Canada's foreign policy positions, continentalism, does not dominate in this analysis. This may not be surprising to many students of UN voting. Though virtually all US allies consult with US diplomats in UN bodies and committees (the UN name for a consultation group of Western countries outside the EU is informally “JUSCANZ,” for example), most of them tend to vote to distance themselves from the US positions. According to Voeten (Reference Voeten2004), the US has, in fact, became more isolated after the end of the Cold War not only because of structural dynamics but also because of Washington's increasingly unilateralist foreign policy turns (see also Cronin, Reference Cronin2001).

Table 3 Perspectives on Canadian Foreign Policy: UNGA Voting Records, All Issues, by Government

Note: '+++ (at least .8), '++ (at least .7), '+ (at least .5). Refer to Table 2 for further details.

* “P. Trudeau” also includes Turner's ministry; “Mulroney” includes Campbell's.

Europeanism fares better overall: most of the time, on most issues, Ottawa was closest to its Western European allies. The results offer some support for the Anglosphere and Francosphere arguments as well. Indeed, Canada's affinity scores with the UK and Australia are relatively high for much of the period under study, as are the scores with France. This would suggest that Canada's like-minded partners tend to be European.

Our analysis does not support the hypothesis that Canada is more inclined to vote with the US under conservative prime ministers. We similarly find no support for the hypothesis that the Canada-US voting coincidence is higher when the Democrats dominate Washington, DC. The interactions of Canadian and US partisanship might matter in some issue areas, but UNGA voting does not appear to be one of them.

PCA results support all of these findings. Together, Figures 3 through 6 confirm Canada's long-standing tendency to vote alongside Europe's major and middle powers. Consistently closest to Ottawa's positions are the positions of the Benelux and Scandinavian states, as well as Germany—a group of states that IR scholars have variously dubbed “civilian powers,” “international do-gooders,” “good international citizens,” “humanitarian superpowers” and “global good Samaritans” (for discussions, see Maull, Reference Maull2000: 56; Smith, Reference Smith2000: 12; Vucetic, Reference Vucetic2017: 506–7).

Though government change is known to significantly affect UNGA voting in general, in Canada this appears to be the case only in the Harper governments, particularly the last two (2008–2011 and 2011–2015). One piece of evidence is a sharp drop in the affinity scores with all listed countries save for the US and Israel (for context, see Chapnick, Reference Chapnick, Chapnick and Kukucha2016) and also, to a lesser extent and only after 2006, Australia (compare Seligman, Reference Seligman2016: 309). PCA provides another piece of evidence, showing Canada's rising affinity with the positions of the US, Israel, Marshall Islands and Micronesia after 2009. These findings support the Harper break thesis in CFP.Footnote 13 The Harper break does not appear to be easily reversible either, given that the government of Trudeau fils in its first two years evidently failed to bring Canada's voting record back where it was under Martin, not to mention under Chrétien. Should this trend continue after 2017, then CFP scholars interested in Canada's UNGA voting practices might be tempted to revisit the meaning of “symbolic obeisance”—a costly public display of submission to the superordinate state (Vucetic and Tago, Reference Vucetic and Tago2015: 106)—and other ideas associated with continentalist frameworks.

Conclusion

In this study, we have examined Canada's UNGA voting records in order to inform the scholarship on Canadian foreign policy. Our main contribution to the literature is in demonstrating the importance of both “Europe” and “Harper.” We find that Ottawa votes less frequently with the US position than the continentalist argument would suggest. Looking at the overall voting records from 1980 onward, we see that Canada tends toward the positions of its Western European allies, with the outstanding exception being the Harper era. The European orientation holds true both for major powers, such as Germany, and for middle powers, such as the Netherlands or Norway. Canada's affinities with the UK and France are similarly high, as is the affinity with Australia—findings that might indicate the legacy of empire and of the respective Anglo- and Francospheres. Next, although we find no evidence that Canada's voting aligns more with the US when the Liberals are out of power, our analysis does capture a sharp pro-US turn under Harper—a development that appears to have outlasted the Conservative prime minister. Finally, nothing in our analysis suggests that Ottawa is more closely aligned with Washington under either a Democratic presidency or a Democratic Congress.

The study's other substantive contribution was the deployment of a new technique for analyzing UNGA voting: PCA. Though the use of dyadic indicators has a bright future, we think that IR scholars should also seek to develop techniques that enable us to pay much greater attention to region-level and peer group–level influences on state behaviour in the world's largest deliberative body. As mentioned earlier, what challenges any voting-based measure of state behaviour is a relatively narrow scope of UNGA voting—that is, the fact that many, if not most, items on the body's agenda are adopted without a formal vote. This is why it is important to consider alternative methodological approaches to the study of Canada in the UNGA. CFP scholars interested in how Canada positions itself vis-à-vis other states might consider content-analyzing official statements issued during the General Debates (Hecht, Reference Hecht2016; Baturo et al., Reference Baturo, Dasandi and Mikhaylov2017), much as Paquin and Beauregard (Reference Paquin and Beauregard2013) did in their study of international crisis statements between 2004 and 2011. More interpretively oriented CFP scholars could do the same using discourse analysis. They can likewise approach the UNGA as a community of practice or as a site for staging specific political performances and then study the ways in which Canadian representatives there act (Sending et al., Reference Sending, Pouliot and Neumann2015). Voeten (Reference Voeten2013), for example, has argued that the key to understanding the role that political manipulation, or heresthetics, plays in the language of resolutions and statements lies in observing everyday habits and routines of UN delegates. Accordingly, CFP would benefit from ethnographic studies of how Canadian delegates choose to support which resolutions, rhetoric and statements, and with what rationalizations for the inevitable gaps between rhetoric and reality.

Our analysis has relevance for contemporary political and policy discourse on Trudeau's foreign policy (see, for example, Vucetic, Reference Vucetic2017; Charron, Reference Charron, Hillmer and Lagassé2018; Nimijean, Reference Nimijean2018). After watching US President Donald Trump continually disrespect laws, institutions and norms at both home and abroad, the representatives in the Trudeau government have repeatedly spoken out to promote the so-called liberal (also known as rules-based) international order—a set of variegated global configurations that was never particularly liberal, rules-based, international or orderly. Long seen as Canada's natural habitat, said order is also under attack by other illiberal forces operating globally—the rise of China, above all, but also the assertiveness of Russia, the growing popularity of ethno-nationalism around the world and the transnationalization of radical conservative political movements. Yet our analysis shows that Ottawa is decidedly not jumping at every opportunity to support Canada's liberal democratic partners and peers in Europe and Asia. However, changing a UNGA voting pattern to fit official pronouncements would only be a start. If the Trudeau government truly believes that liberal democracies can no longer depend on the US to provide leadership and act as liberalism's patron, as Foreign Minister Freeland famously argued in June 2017, and that “we really are at a time when liberal democracy is under greater threat as an idea than at any time since the Second World War,” as she stated in an interview two years later (Ibbitson, Reference Ibbitson2019), then its representatives should work much harder on mobilizing and investing political, economic and military resources in defence of Canada's interests and values.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423919000507.

Acknowledgments

We thank the three anonymous reviewers; Roland Paris, Ravi Pendakur, Byungwon Woo, Wen-Chin Wu; and the participants of the 2019 Women in International Security-Toronto Twitter Conference, particularly Leah Sarson and Veronica Kitchen.