Introduction

In the absence of an intact incus, Austin defined four types of ossicular chain defectsReference Austin 1 : type A, malleus handle present, stapes superstructure present; type B, malleus handle present, stapes superstructure absent; type C, malleus handle absent, stapes superstructure present; and type D, malleus handle absent, stapes superstructure absent. The commonest ossicular chain defect is Austin type A, accounting for almost 60 per cent of cases, with type B accounting for 23 per cent, type C for 8 per cent and type D for 8 per cent.Reference Austin 1 , Reference Iurato, Marioni and Onofri 2 A wide variety of materials are available for reconstructing ossicular chain defects, for example, an autologous or homologous incus or a commercially available prosthesis made of titanium, hydroxyapatite or Teflon. However, very few prospective clinical trials have compared materials: studies have usually reported the results of ossiculoplasty with only one type of prosthesis or have compared the results of using different prostheses based on historical data.Reference Yung and Smith 3 The two best available materials are an autologous incus and a titanium prosthesis. As it comprises the patient's own tissue, an autologous incus has advantages such as biocompatibility, a very low extrusion rate, no risk of transmitting disease, cost-effectiveness and no need for reconstitution.Reference O'Reilly, Cass, Hirsch, Kamerer, Bernat and Poznanovic 4 Titanium is reported to be an excellent material for ossicular reconstruction because of its high biocompatibility, high biostability and low ferromagnetism. In addition, it is lightweight and rigid, making it a good sound conductor.Reference Martin and Harner 5 As both sculpted autologous incus interposition and titanium prosthesis have clear advantages, we undertook the present study to evaluate and compare the results of ossiculoplasty using these materials.

Materials and methods

Patients

A total of 234 patients aged 10–60 years with chronic otitis media with conductive hearing loss (clinical and audiological; hearing loss of more than 40 dB) with evidence of ossicular erosion underwent exploratory tympanotomy between December 2008 and November 2012 at KLES Dr Prabhakar Kore Hospital in Southern India (Belagavi, Karnataka). Of these, 40 patients who fulfilled the inclusion criterion of having an Austin type A defect underwent ossiculoplasty; those with mixed hearing loss and extensive cholesteatoma (Austin type B, C and D defects) were excluded.

The required sample size was calculated using the formula: n = (2 × (zα + zβ)2 × s 2) ÷ d 2 = 2 × (1.96 + 0.84)2 × 5.62 ÷ 52 = 19.66 = 20 in each group (total 40), with an effect size (d) of x 1 − x 2 = 05 and a common standard deviation of 5.6. The type I error (α) was 0.05 (zα = 1.96), the type 2 error (β) was 0.2 (zβ = 0.84) and the power of the study was calculated as 1 – β = 0.8 = 80 per cent.

Participants were allocated to an autologous incus interpositioning group or a titanium prosthesis group using a computer-based random number generator (www.graphpad.com/quickcalcs). Patients in the titanium prosthesis group underwent ossicular chain reconstruction using a Decibel's titanium prosthesis wire and bell type with flanges.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee for Research on Humans of KLE University. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants using a standardised consent form approved by the ethics committee. For minors, consent was obtained from the parent or guardian and assent was obtained from the patient.

All procedures included in this study complied with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional guidelines of the Institutional Research Board on Human Experimentation of KLE University and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Surgical procedure

Most procedures were performed under local anaesthesia comprising 2 per cent xylocaine with 1 in 100 000 adrenaline infiltration into four quadrants of the canal wall at the bony cartilaginous junction, and at the incisura terminalis, the retroauricular groove, the temporalis region and over the mastoid process. General anaesthesia was administered to patients who were excessively apprehensive and uncooperative.

A post-aural approach was used in all procedures. A Wilde's post-aural incision was made about 5 mm behind the retroauricular groove, extending from the highest point of attachment of the pinna to the tip of the mastoid. A temporalis fascia graft was then harvested and standard tympanomastoidectomy was performed to clear disease from the middle-ear cleft prior to ossicular reconstruction. Patients with mucosal disease underwent canal wall up mastoidectomy with establishment of aditus patency and those with squamous disease underwent canal wall down mastoidectomy with removal of cholesteatoma and granulations.

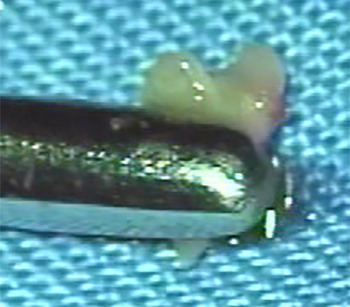

For both patient groups, the incus with a necrosed lenticular or long process was detached from the incudomalleal joint and removed. In the autologous incus interpositioning group, the incus was held with Derlacki ossicle holding forceps so that the body of the incus could be drilled and reshaped with a 0.6-mm diamond burr. The remnant of the long process was drilled out to make it cylindrical with a flat base.Reference Mahadevaiah 6 A socket was then drilled under the surface of the remodelled long process for engaging the head of the stapes (Figure 1). Part of the short process and the articular facet of the body were removed to avoid ankylosis with the posterior canal wall. The superior border of the body was then flattened to facilitate its attachment to the tympanic membrane and a notch was drilled on the superior surface of the body to accommodate the handle of the malleus (Figure 2).Reference Sanna and Haberman 7 The mobility of the footplate was first confirmed by applying intermittent pressure over the stapes superstructure and assessing round window reflex. The refashioned incus was then interposed between the handle of the malleus and the stapes superstructure (notched incus with short process; Figure 3).

Fig. 1 Photograph showing a socket being drilled with a 0.6-mm diamond burr into the remnant of the long process of incus for engaging the stapes head.

Fig. 2 Photograph showing a notch made with 0.6-mm diamond burr over the body of incus to fit the handle of the malleus.

Fig. 3 Photograph showing the refashioned incus (I) interposed between the handle of the malleus (M) and the stapes head (S).

In the titanium prosthesis group patients, the incus was removed and a prosthesis was placed between the handle of the malleus and the stapes superstructure (Figure 4). The length of prosthesis required to bridge the ossicular defect was measured using an osseous sizer. A piece of conchal cartilage was placed over the prosthesis to prevent extrusion and resultant residual perforation. This was followed by temporalis fascia grafting over the cartilage, followed by packing the external auditory canal with Gelfoam®. Canal wall down mastoidectomy included wide meatoplasty. The wound was then closed in layers and a mastoid dressing was applied.

Fig. 4 Photograph showing a titanium partial ossicular replacement prosthesis (PORP) placed between the handle of the malleus (M) and the stapes superstructure (S).

Post-operative follow up

Patients were followed up weekly for the first 3 weeks and then at 6 and 12 weeks. After one week, sutures were removed and the wound was examined. After six weeks, graft take up was assessed (anatomical outcome). After 12 weeks, hearing was evaluated by pure tone audiometry (functional outcome) and the graft status was assessed.

Anatomical outcome

The operated ear was evaluated otoscopically for graft take up, displacement and extrusion at 6 and 12 weeks. Anatomical success was defined as tympanic membrane healing, an intact graft and resolution of ear discharge. Post-operative complications were considered an unsuccessful outcome.

Functional outcome

Hearing was measured by pure tone audiometry at 3, 6 and 12 months post-operatively. Audiometric evaluation included measuring pre- and post-operative air-conduction and bone-conduction thresholds at four frequencies (0.5, 1, 2 and 4 kHz). The air–bone gap (ABG) was calculated pre- and post-operatively by calculating the difference in average air- and bone-conduction thresholds measured at the same time. Pre- and post-operative ABGs were then compared to assess the hearing outcome. Audiometry was reported according to American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery guidelines,Reference Black 8 except for thresholds at 3 kHz, which were substituted in all cases with thresholds at 4 kHz because 3 kHz measurements are not routinely made.

An ABG closure of less than 20 dB (i.e. hearing gain) was considered a successful outcome, an ABG closure of 21–30 dB was considered a satisfactory outcome and an ABG closure of more than 30 dB was considered an unsuccessful outcome.

Statistical analysis

For quantitative parameters, the mean, median and standard deviation were calculated. Student's t-tests were used to compare basic parameters (such as age, sex and laterality) between the two patient groups. Student's t-tests (unpaired) were used to determine significant differences in hearing outcome between the two groups. Paired t-tests were used to compare pre- and post-operative hearing results within each group. All data were analysed using SPSS for Windows software version 16.0 (Chicago, Illinois, USA). Statistical significance was set at a p value of 0.05.

Results

Comparison of basic parameters and demographic data

Basic parameters (such as age, sex and laterality) and demographic data for both groups are compared in Table I. The average patient age was 24 ± 9.8 years. In all, 22 of the 40 patients (55 per cent) were male, 23 patients (57.5 per cent) had right ear involvement, 22 patients (55 per cent) had mucosal type disease and 18 (45 per cent) had squamous disease. There was no significant difference in patient parameters and demographics between groups. The average operative time (i.e. time required for ossicular reconstruction after clearance of middle-ear disease) was 35 ± 8 minutes for the autologous incus group and 15 ± 5 minutes for the titanium prosthesis group.

Table I Basic parameters for both groups

*t-test. †χ2 test. PORP = partial ossicular replacement prosthesis; SD = standard deviation; COM = chronic otitis media

Hearing outcome

The average pre-operative ABG in the autologous incus and titanium prosthesis groups was 42.14 ± 6.96 and 44.37 ± 9.54, respectively, and the average post-operative ABG closure after 3 months was 24.23 ± 8.50 and 31.27 ± 13.87 in the autologous incus and the titanium prosthesis group, respectively (Table II). There was significant post-operative hearing improvement in both groups (autologous incus group, p = 0.006; titanium prosthesis group, p = 0.032; paired t-test). However, the mean reduction in ABG was significantly better in the autologous incus group (17.91 ± 7.14) than in the titanium prosthesis group (13.05 ± 12.46; p = 0.047). The mean post-operative ABG closure was also significantly better in the autologous incus group than in the titanium prosthesis group (p = 0.062; Student's unpaired t-test).

Table II Average post-operative hearing in both groups

Data are means ± standard deviation (range). *Comparison of pre-and post-operative hearing. †Paired t-test. ‡ p values are statistically significant. **Comparison of patient groups. §Student's unpaired t-test. ABG = air–bone gap; pre-op = pre-operative; post-op = post-operative; mon = months; PORP = partial ossicular replacement prosthesis

An average post-operative ABG closure of less than 20 dB (i.e. hearing gain) representing a successful outcome was achieved in 13 patients (65 per cent) in the autologous incus group and 7 (35 per cent) in the titanium prosthesis group (Figure 5). An ABG closure of 21–30 dB representing satisfactory subjective hearing improvement was achieved in three patients (15 per cent) in the autologous incus group and six (30 per cent) in the titanium prosthesis group.

Fig. 5 Graph comparing hearing outcomes between patient groups in terms of the air–bone gap (ABG) closure. *Successful hearing gain. Ti = titanium; PORP = partial ossicular replacement prosthesis

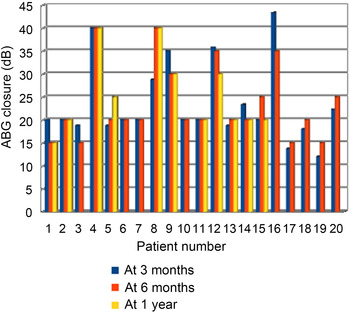

Comparison of hearing outcomes at different follow-up times

Hearing outcomes (ABG) at 6 and 12 months post-operatively were compared to those at 3 months to identify changes in long-term hearing outcomes (Figures 6 and 7). In the autologous incus group, the difference in ABG between 3 and 6 months was 1.52 ± 8.27 (p = 0.422, paired t-test) and between 3 and 12 months was 0.82 ± 5.55 (p = 0.634). In the titanium prosthesis group, the difference in ABG between 3 and 6 months was 0.72 ± 10.11 (p = 0.752, paired t-test). However, only 11 of these patients attended the follow up at 12 months; the difference in ABG between 3 and 12 months was 0.79 ± 9.83 (p = 0.794, paired t-test). These results indicate that there was little change in hearing outcome with a longer follow-up period (up to 1 year) in both patient groups. Poor patient compliance with longer follow up was the only concern.

Fig. 6 Graph showing hearing outcomes at 3, 6 and 12 months after ossiculoplasty in patients in the autologous incus group. ABG = air–bone gap

Fig. 7 Graph comparing hearing outcomes at 3, 6 and 12 months after ossiculoplasty in patients in the titanium partial ossicular replacement prosthesis group. ABG = air–bone gap

Comparison of hearing outcomes by type of mastoid surgery

In the autologous incus group, 12 patients underwent canal wall up mastoidectomy with ossiculoplasty for mucosal type chronic otitis media and 8 patients underwent canal wall down mastoidectomy with ossiculoplasty for squamous type chronic otitis media. In the titanium prosthesis group, 10 patients underwent canal wall up mastoidectomy with ossiculoplasty for mucosal type chronic otitis media and 10 underwent canal wall down mastoidectomy with ossiculoplasty for squamous type chronic otitis media. In the autologous incus group, the post-operative ABG was 22.16 ± 6.64 in patients who underwent canal wall up mastoidectomy with ossiculoplasty and 27.35 ± 10.25 (p = 0.233, Student's unpaired t-test) in those who underwent canal wall down mastoidectomy with ossiculoplasty. Similarly, in the titanium prosthesis group, the post-operative ABG was 29.75 ± 6.63 in those who underwent canal wall up mastoidectomy with ossiculoplasty and 32.80 ± 18.88 in those who underwent canal wall down mastoidectomy with ossiculoplasty (p = 0.639, Student's unpaired t-test). These data indicate no significant difference in post-operative hearing outcome between canal wall up and canal wall down mastoidectomy with ossiculoplasty for both patient groups (Table III).

Table III Hearing outcome by type of mastoid surgery

*Student's unpaired t-test. PORP = partial ossicular replacement prosthesis

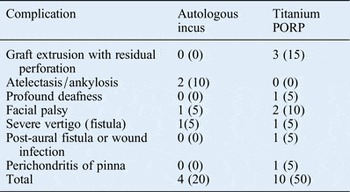

Comparison of post-operative complication rates

In the autologous incus group, 4 patients (20 per cent) developed post-operative complications, compared with 10 (50 per cent) in the titanium prosthesis group (Table IV). The commonest complication in the autologous incus group was ankylosis of the incus graft to adjacent middle-ear structures secondary to atelectasis, which was seen in two patients (10 per cent). In contrast, the commonest complication in the titanium prosthesis group was prosthesis extrusion with residual tympanic membrane perforation, which was seen in three patients (15 per cent).

Table IV Post-operative complication rates in both groups

n = 20 in each group. Data are n (%). Ti = titanium; PORP = partial ossicular replacement prosthesis

Discussion

The ossicle most commonly involved in chronic otitis media is the incus (i.e. an Austin type A defect), and ossicular reconstruction is challenging in such cases. Very few clinical trials have compared the results of using different materials for reconstruction. Before undertaking the present study, an extensive literature search (1960–2008) of various databases (MEDLINE, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials) identified no prospective clinical trials comparing the results of ossiculoplasty with an autologous incus versus a titanium prosthesis. In 2010, Yung and Smith reported only two clinical trials comparing different ossiculoplasty materials, and emphasised the need for more clinical trials to standardise ossiculoplasty techniques and identify a universally acceptable ossiculoplasty material.Reference Yung and Smith 3

The present study was conducted on the southern Indian population of Belagavi, Karnataka. Comparison of basic demographic data showed that both groups had similar age, sex and other parameters. Patients aged between 10 and 60 years were included in this study. This age range was selected because Eustachian tube function (a prerequisite for successful ossiculoplasty) is not well developed in younger children, who also have a higher rate of middle-ear infections.Reference Austin 1 , Reference Telian, Schmalbach, Snow and Ballenger 9 In patients aged above 60 years, hair cell degeneration leading to age-related sensorineural hearing loss (presbyacusis) may compromise the surgical outcome.Reference Telian, Schmalbach, Snow and Ballenger 9

In the present study, post-operative hearing improvement (as determined by ABG closure) was significantly better in the autologous incus group than in the titanium prosthesis group. A successful hearing outcome (ABG < 20 dB) was achieved in 13 patients (65 per cent) in the autologous incus group and 7 (35 per cent) in the titanium prosthesis group. Moreover, three patients (15 per cent) in the autologous incus group and six (30 per cent) in the titanium prosthesis group had an ABG closure of 21–30 dB, which was considered a satisfactory outcome. Iñiquez Cuadra et al. defined the social hearing level as an ABG of less than 30 dB.Reference Iñiquez Cuadra, Alobid, Bores Domenech, Menedez Colino, Caballero and Bernal Sprekelsen 10 In the only retrospective study similar to ours, Ceccato et al. reported ossiculoplasty outcomes for 148 patients (autologous incus, 98; titanium prosthesis, 50), concluding that ossiculoplasty was significantly better when using an autologous incus rather than a titanium prosthesis.Reference Ceccato, Maunsell, Morata and Portmann 11 The present authors reported similar results in a preliminary study into the reconstruction of Austin types A and B defects with an autologous incus or a titanium prosthesis (as a partial or total ossicular replacement prosthesis).Reference Naragund, Mudhol, Harugop and Patil 12 However, that study was limited by a smaller sample size and broader inclusion criteria, thereby making it difficult to standardise the results and make conclusions. Thus, the more focused present study was undertaken.

Most patients underwent concurrent ossiculoplasty: only 4 of the 40 patients underwent ossiculoplasty during second stage surgery (1 in the autologous incus group and 3 in the titanium prosthesis group). No differences in anatomical and functional outcomes were observed between patients who underwent staged surgery and those who underwent ossiculoplasty as a primary procedure. Kim et al. reported similar results in patients who underwent primary and staged surgery.Reference Kim, Battista, Kumar and Wiet 13 These authors concluded that a staged approach to ossicular reconstruction after tympanomastoidectomy is preferable, with more severe disease necessitating the creation of an open mastoid cavity in an ear without an intact stapes superstructure. In patients with limited disease that can be adequately removed with a closed mastoid cavity, concurrent ossicular reconstruction is preferable.

In the present study, there were no significant differences in anatomical and functional outcomes at 3, 6 and 12 months post-operatively. However, a major drawback was poor patient compliance for longer follow up. At 1 year post-operatively, only 14 patients (70 per cent) in the autologous incus group and 11 (55 per cent) in the titanium prosthesis group attended follow up. Yung retrospectively evaluated long-term outcomes in 242 ossiculoplasty patients by conducting an ear audit clinic.Reference Yung 14 Patients were followed up at 3 weeks, 6 weeks, 3 months and 6 months post-operatively and then on a yearly basis until 5 years. At 6 months 232 patients (92 per cent) attended follow up, but the number gradually dropped at each subsequent follow up; at 5 years, only 134 patients (74 per cent) were followed up. Successful hearing gain (ABG of less than 20 dB) was seen in 64.2 per cent of patients at six months, 62.1 per cent at one year and only 50 per cent at five years.Reference Yung 14

In the present study, the ratio of patients who underwent canal wall up surgery with ossiculoplasty to canal wall down surgery with ossiculoplasty was 12:8 in the autologous incus group and 10:10 in the titanium prosthesis group. There was no significant difference in post-operative hearing between patients who underwent either procedure in both groups. Most studies have concentrated on the use of different techniques and different graft materials for ossiculoplasty and not on the type of mastoid surgery.Reference Yung and Smith 3 Few studies have reported the results of ossiculoplasty according to the type of mastoid surgery. The outcome of reconstruction depends on Eustachian tube function, which in turn is determined by whether the patient had safe or unsafe disease.

In the present study, there were more complications with a titanium prosthesis than with an autologous incus: the latter is more physiological and biocompatible and is therefore well tolerated by the body. The commonest complication with an autologous incus was ankylosis of the graft to adjacent middle-ear structures secondary to atelectasis, which was seen in two patients (10 per cent). This may be due to post-operative Eustachian tube dysfunction leading to negative middle-ear pressure, resulting in atelectasis and ankylosis of the ossicular graft with adjacent structures or its extrusion.

-

• Austin type A is the commonest ossicular defect (present in more than 60 per cent of patients)

-

• Ossiculoplasty using an autologous incus or a titanium partial ossicular replacement prosthesis provides the best graft take up rates and hearing results

-

• This study compared the anatomical and functional outcomes of ossiculoplasty using these materials

-

• Ossiculoplasty with an autologous incus provided the best hearing results, with minimal post-operative complication and extrusion rates, and was most cost-effective

The most common complication for patients in the titanium prosthesis group was prosthesis extrusion, resulting in residual perforation and conductive hearing loss (3 patients; 15 per cent). The cause of early extrusion may be attributed to post-operative infection or graft failure, while late extrusion may be attributed to poor Eustachian tube function, cartilage slippage from the prosthesis head or the prosthesis being too long.Reference Silverstein, McDaniel and Lichtenstein 15 The cause of facial palsy in both groups was a displaced graft or prosthesis impinging onto the dehiscent facial nerve near to the second genu, as found on re-exploration after three weeks. In affected patients, the prosthesis was removed and facial nerve decompression was performed. As the middle ear has low immunological reactivity, various kinds of materials can be used in chronic otitis media surgery.Reference Geyer 16 , Reference Hüttenbrink 17 Olgun et al. attributed failure to technical aspects and not to an immunological reaction.Reference Olgun, Kandagon, Gultekin, Guler and Cerci 18 These authors reported that an adequately shaped implant used with adequate tension between the reconstructed tympanic membrane and oval window generally gives good results. To achieve this, a piece of cartilage should be placed over the platform of the prosthesis.

Overall, there is a need for extended follow up to evaluate the long-term results (at one to five years) of ossiculoplasty. There is also a need for more clinical trials including different graft materials and larger cohorts to standardise the ossiculoplasty techniques and identify the best type of ossicular prosthesis.

Conclusion

Hearing results and graft take up after ossiculoplasty are significantly better when using an autologous incus rather than a titanium prosthesis for reconstructing Austin type A ossicular defects. However, the titanium prosthesis has also shown promising results and can be considered an alternative for ossicular chain reconstruction in cases where the incus is unavailable or completely diseased. The major disadvantages of using a titanium prosthesis are unpredictable results and higher post-operative complication and extrusion rates compared with the autologous incus. The only limitation of incus interposition ossiculoplasty is the need for longer operative time and a greater skill level to ensure that appropriate sculpting and repositioning are achieved.

Ossiculoplasty using an autologous incus provides better hearing results with minimal post-operative complication or extrusion rates and is cost-effective compared with a titanium prosthesis for reconstructing Austin type A ossicular defects.

Acknowledgements

The authors are sincerely grateful to P Kore, C K Kokate and V D Patil for providing the necessary infrastructure and support for conducting this study. We also thank N S Mahanshetti, Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College, for her constant encouragement during the study.