Introduction

In 2018, the number of Chinese citizens aged 65 and above reached about 166 million, accounting for 12 per cent of the total population (NBS, 2018). Nowadays, rapid population ageing and the wellbeing of these senior citizens have become serious concerns for the Chinese government, attracting much attention from the public and academia. Providing social security and social services to such a large elderly population while maintaining rapid economic growth has become a big challenge for China. Numerous studies have tried to identify factors contributing to older adults’ physical health, mental health or quality of life, generating policy implications to improve their welfare and wellbeing effectively.

In the last ten years, the life satisfaction of older adults, a comprehensive indicator of subjective wellbeing and quality of life, has received increasing attention. Existing literature has found that the pension, social support and self-care ability are very significant predictors of older adults’ life satisfaction (Chou and Chi, Reference Chou and Chi1999; Pinquart and Sörensen, Reference Pinquart and Sörensen2000; Bishop, Reference Bishop, Martin, Johnson and Poon2003; Katz, Reference Katz2009; Han, Reference Han2020). Meanwhile, many researchers have also argued that the impacts of these factors on life satisfaction can be moderated by age, gender, education, marital status and living arrangements (Chou and Chi, Reference Chou and Chi2000; Oshio, Reference Oshio2012). Among these moderators, the role of gender deserves special attention in Chinese society, where the patriarchal culture is deep-rooted and gender division of domestic labour still prevails in old age (Wen et al., Reference Wen, Liang, Zhu and Wu2013). Previous studies have given much attention to the gender differences in the association between older adults’ life satisfaction and social relationship, such as marital relations, intergenerational relationships and friendship (Acitelli and Antonucci, Reference Acitelli and Antonucci1994; Cheng and Chan, Reference Cheng and Chan2006; Oshio, Reference Oshio2012; Tobiasz-Adamczyk et al., Reference Tobiasz-Adamczyk, Galas, Zawisza, Chatterji, Haro, Ayuso-Mateos, Koskinen and Leonardi2017). Although many scholars believe that gender will make a difference in many aspects, very few studies, and even fewer in China, have comprehensively investigated the role of gender in the associations between the pension, social support, self-care ability and older adults’ life satisfaction.

In the context of China, a more gendered society relative to many Western countries, are older men more sensitive to pensions than older women after retirement? Are older men more sensitive to social support from friends and family in their old age as they spend much more time at home than before? Who (older men or older women) would be more satisfied with life if they could look after themselves in their daily life? Exploring how gender works with pensions, social support and self-care ability in older adults’ life satisfaction will shed light on how to improve their wellbeing effectively and generate implications relevant to other Asian societies where traditional gender norms still prevail.

Literature review

Compared to younger adults, older adults (i.e. those aged 65 and above) in China were born and grew up in a more traditional environment which was more patriarchal and gendered. They were more affected than the young adults today by the traditional Chinese ideology and culture of ‘male breadwinner, female home-maker’ (nan zhu wai nv zhu nei) and ‘male superiority over women’ (nan zun nv bei) (Shu and Zhu, Reference Shu and Zhu2012). When older adults enter retirement age, the breadwinner model may lose its function for the family as older men exit the labour market (Springer et al., Reference Springer, Lee and Carr2019). The changes in income, employment, relationships and health condition may have different impacts on the lives of older men and women (Van Solinge and Henkens, Reference Van Solinge and Henkens2005). As men enter into older adulthood, they will lose their work and make a much smaller economic contribution to the household, and they will spend much more time at home than before and gradually lose work-related social contacts. Older men may also have to care for the grandchildren and spouse (if she is not in good health) occasionally. Enduring gender scripts inscribe that men should not take up housework and care that are supposed to be ‘women's work’ (Russell, Reference Russell2007; Luo, Reference Luo2016). These socially constructed gender roles may affect older men's life satisfaction when their economic contribution, social networks and daily activities change dramatically after retirement. Older women will become more dependent on economic support from their children as their spouse cannot provide as much income as before, and they may spend more time caring for family members.

Financial security is a crucial factor for Chinese older adults’ life satisfaction, as evidenced in many studies (Zhang and Lucy, Reference Zhang and Lucy1998; Chou and Chi, Reference Chou and Chi1999; Zhang and Liu, Reference Zhang and Liu2007; Lou, Reference Lou2010; Li et al., Reference Li, Chi, Zhang, Cheng, Zhang and Chen2015). There is a Chinese saying ‘raising children to provide against old age’ (yang er fang lao) which highlights the importance of economic support from children to older adults. However, as the fertility rate decreases and family size shrinks in China, the family support system for older adults is weakening and parental expectations regarding economic support from the younger generations is declining (Zhang and Goza, Reference Zhang and Goza2006). Nowadays, the pension has become an important source of economic support, especially in urban areas. The mandatory pension age in China is 60 for men, 55 for white-collar women and 50 for blue-collar women (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2017). The pension scheme, as a part of the social welfare system in China, has been reformed greatly since the late 1980s. Currently, there are two main parallel public pension systems in China: a public pension system for urban employees and a public pension system for urban and rural residents. With respect to the public pension system for urban employees, the scheme includes two tiers. The first is a pay-as-you-go-defined-benefit plan financed entirely by employers, with a maximum contribution of 20 per cent of the payroll (in most areas). The second tier is a funded-defined-contribution (FDC) plan calling for mandatory individual accounts. These accounts are entirely financed by employees who must contribute 8 per cent of their earnings. With respect to the public pension system for urban and rural residents, it is a FDC plan. When covered people reach the retirement age, they will receive monthly benefits derived from the pension scheme.

Ofstedal et al. (Reference Ofstedal, Reidy and Knodel2004) have shown that there is a large gender gap in the percentage of older adults receiving pensions in many Asian countries. Due to the past gender difference in employment, older men in Asia are more likely to receive a pension than older women, and older women to some extent are ‘forced’ to rely on children (Ofstedal et al., Reference Ofstedal, Reidy and Knodel2004). Iecovich and Lankri (Reference Iecovich and Lankri2002) have shown that older women have stronger attitudes towards receiving economic support from adult children than older men. The gender gap in pensions actually reflects the gender difference in lifecourse and is inherent in the culture (Frericks et al., Reference Frericks, Knijn and Maier2009). With norms of gender specialisation, older men may see receiving pensions as a way to restore their role as a breadwinner in the family. Thus, it is hypothesised:

• Hypothesis 1: The pension is positively associated with older adults’ life satisfaction, and this association is stronger among older men than older women.

Social support is consistently proved to be another determinant. One mechanism explaining the association between social support and older adults’ life satisfaction is that social support promotes self-esteem (i.e. feelings of worthiness and respect) (Krause, Reference Krause1987). Oshio (Reference Oshio2012) found that Japanese older men are more sensitive to family support than to friend support, while the opposite is true for older women. This indicates that different sources of social support may work differently for men and women. If a certain type of social support can increase self-esteem, it is very likely to contribute to older adults’ life satisfaction.

The Lubben Social Network Scale (Lubben, Reference Lubben1988) could be a useful tool for assessing social support among older mainland Chinese (Chang et al., Reference Chang, Sha, Chan and Yip2018). According to the LSNS, there can be three sources of social support: family support, friend support and interdependent social support. Older women tend to have more extensive social networks than men and receive more support from friends, spouse, children and other relatives, while men may primarily get support within the family, particularly from their spouse (Gurung et al., Reference Gurung, Taylor and Seeman2003). This difference may result from the gender difference in socialisation expectation in that men are supposed to be independent and self-reliant while women are expected to seek support (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2004; Schulz and Schwarzer, Reference Schulz and Schwarzer2004). Considering such structural difference in social support (in terms of the source), family support may matter more to older men, while friend support may matter more to older women. Lu et al. (Reference Lu, Jiang, Lou, Zeng and Liu2018) have found that in urban China older men are likely to benefit more from family social capital. Therefore, the hypothesis is:

• Hypothesis 2a: The association between family support and life satisfaction is stronger among older men than older women, while the association between friend support and life satisfaction is stronger among older women than older men.

The existing literature has explored the role of family support and friend support (Zhang and Li, Reference Zhang and Li2011; Oshio, Reference Oshio2012), while less attention has been paid to interdependent social support, especially from a gender perspective. Interdependent social support includes confidant relationships (i.e. having a confidant and being a confidant), helping others and living arrangements. Being a confidant (i.e. being consulted in an important decision) and helping others, to some extent, may promote the feeling of self-worth and the sense of value, thus contributing to life satisfaction. Interdependent social support, to some extent, reflects social relatedness. Women are found to value such relatedness more than men and tend to maintain closeness in terms of support exchanges (Cheng and Chan, Reference Cheng and Chan2006). Therefore, our hypothesis on interdependent social support is:

• Hypothesis 2b: The association between interdependent social support and life satisfaction is stronger among older women than older men.

Self-care ability reflects independence in daily life. It is often measured by the activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily life (IADL) scales (Borg et al., Reference Borg, Hallberg and Blomqvist2006; Bai et al., Reference Bai, Guo and Fu2018). Kim (Reference Kim1998) found that there are positive associations among self-care ability, self-esteem and life satisfaction, indicating that the ability to live independently may contribute to life satisfaction by increasing self-esteem. Self-care ability may also contribute to life satisfaction, by reducing loneliness (Borg et al., Reference Borg, Hallberg and Blomqvist2006). Dykstra et al. (Reference Dykstra, Van Tilburg and de Jong Gierveld2005) have found that improvement in self-care ability and network expansion make older adults feel less lonely. Bai et al. (Reference Bai, Guo and Fu2018) have found that once controlling for self-image, the positive association between self-care ability and life satisfaction disappears, indicating the mediation of self-image.

Although self-care ability is widely confirmed to be an important predictor of life satisfaction (Zhang and Lucy, Reference Zhang and Lucy1998; Borg et al., Reference Borg, Hallberg and Blomqvist2006; Høy et al., Reference Høy, Wagner and Hall2007; Enkvist et al., Reference Enkvist, Ekström and Elmståhl2012), whether there is a gender difference in the relationship between self-care ability and life satisfaction remains unclear. It should be noted that in the measurement of self-care ability, particularly the IADL scale, some of the daily activities, such as food preparation, housekeeping and laundry, are supposed to be done mainly by women rather than men in Chinese society. As there are strong traditional gender norms associated with these activities, if men are seen performing them on their own by neighbours, they will lose ‘face’ (mianzi) and their self-image will be damaged, feeling that they are looked down upon by the community. As self-image is found to be more potent to older men's life satisfaction (Bai et al., Reference Bai, Chan and Chow2012, 2018), older men who have higher self-care ability (including doing housework on their own) may not necessarily be more satisfied with life. Therefore, our hypothesis regarding self-care ability is:

• Hypothesis 3: Self-care ability is positively associated with older adults’ life satisfaction; the positive association is stronger among older women than men.

In sum, this paper will examine the associations of pensions, social support and self-care ability with older adults’ life satisfaction from a gender perspective in urban China. This is one of very few studies which comprehensively investigates the potential moderation of gender in various predictors of life satisfaction in the Chinese context. The findings and implications could be very relevant to other Asian societies that have a similar patriarchal culture.

Data and methods

Data collection was based on a face-to-face structured questionnaire survey in January 2018 in Yanshan region, Fangshan District, which is located in the south-west of Beijing, China. The proportion of adults aged 65 or above in Fangshan District (10.92%) is similar to that in the whole of Beijing (10.95%) in 2017 (Beijing Municipal Bureau of Statistics, 2019). The full names of all the registered older adults aged 65+ residing in this district were obtained from the local Bureau of Civil Affairs. Then a systematic sampling method was adopted. If a couple were selected, the older one would be invited to attend the survey. A total of 2,161 respondents aged 65+ were selected from all registered adults aged 65+ living in Yanshan. The sample size accounted for 15.0 per cent of the whole population in Yanshan (N = 14,415). In the questionnaire survey, we tried to invite older adults to answer all the questions by themselves. While for those older adults with severe hearing limitation or cognition impairment, we chose to invite their family members as the proxy to answer the objective questions in the questionnaire, and skipped the subjective ones. Considering that life satisfaction is a subjective measurement that could not be answered by other family members, older adults whose questionnaires were answered by proxies were excluded from the data analysis. Questionnaires with missing values on the key variables of this study were excluded from the study: 114 respondents were excluded, accounting for 5.3 per cent of the total sample. Finally, 2,047 cases were included in the analysis. Data were weighted according to the distribution of age and gender.

The outcome variable was life satisfaction. It was measured using the revised Chinese version of the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al., Reference Diener, Emmons, Larsen and Griffin1985), which contains five items rated on a five-point scale (ranging from 1 = completely disagree to 5 = completely agree) instead of a seven-point scale. So, the total score can range from 5 to 25, with higher scores indicating a higher level of life satisfaction. In this study, the Cronbach's alpha was 0.87.

The pension of a respondent was derived from the question ‘How much is your pension?’ The log of respondents’ pensions was finally used in the model. Social support was measured by the total score of the LSNS scale (Lubben, Reference Lubben1988). Family support, friend support and interdependent social support (including ‘having a confidant’, ‘being a confidant’, ‘being relied upon and helping others’ and ‘living arrangement’) are sub-total scores of questions related to the three dimensions in the LSNS. For specific information on the LSNS, see the online supplementary material. In this study, the Cronbach's alpha of the LSNS was 0.684. The Cronbach's alphas for family support, friend support and interdependent social support were 0.614, 0.846 and 0.478, respectively. Considering Cronbach's alpha for the interdependent social support sub-scale is unsatisfactory, we examined the items of this sub-scale separately in the regression models instead of regarding it as a whole sub-scale. Self-care ability was measured by 15 items related to older adults’ ADLs and IADLs (referring to ADL and IADL scales), including meal preparation, housekeeping, laundry, handling finances, taking medicines, using the telephone, grocery shopping, transportation, bathing, personal hygiene, dressing, mobility in bed, locomotion in home, toileting and feeding. Each item was coded 1 if the respondent did the activity completely by themselves and 0 if the respondent was supported by others on the activity. The total score ranges from 0 to 15, with a higher score indicating a higher level of self-care ability.

Personal attributes, including age, gender, marital status, educational level, number of children and self-rated health status, were controlled in the models. Respondents were asked to report their chronological age. The number of children was measured by a single question: ‘How many children do you have?’ Self-rated health status was measured with a five-point scale ranging from 1 = very poor to 5 = very good. Age, the number of children and self-rated health were treated as continuous variables. Gender and marital status were measured by a binary variable (for gender, 0 = female, 1 = male; for marital status, 0 = currently not married, including never married, divorced and widowed, 1 = currently married). Educational level was measured by the highest level attained on a four-point scale (1 = primary school or below, 2 = junior high school, 3 = senior high school, 4 = college or above) and treated as a categorical variable.

Descriptive analyses were performed to demonstrate the characteristics of the respondents and the distribution of their life satisfaction. Before conducting regression models, bivariate correlations were adopted to test the relationships among variables. Spearman coefficients or Pearson coefficients were estimated to check the linearity of correlation among potential factors. Finally, multiple linear regression models were performed to explore the factors of older adults’ life satisfaction. To explore the gender-specific difference, the interaction of pensions, social support and self-care ability with gender were included in the regression models in a stepwise way. All the analyses were conducted using SPSS version 21.0.

Results

Descriptive analyses

As shown in Table 1, the average age of respondents was 72.9 (standard deviation (SD) = 6.2), 47.4 per cent of the respondents were male and 52.6 per cent were female. With regard to marital status, most of the respondents (about 74.2%) were currently married and 25.8 per cent were not currently married (including never married, widowed and divorced). In terms of education, 29.1 per cent of the respondents had a primary education or below, 36.2 per cent had a junior secondary education, 20.3 per cent had a senior secondary education and 14.4 per cent had a tertiary education. Table 1 also demonstrates the characteristics in both female and male samples. There were some gender differences in socio-demographic profiles (e.g. marital status, educational level, number of children and self-rated health status). As expected, the average amount of the male respondents’ pensions is significantly higher than that of the female respondents. Also female respondents have better performance for friend support than male respondents, as well as some aspects of interdependent social support (e.g. having a confidant, being relied upon and helping others, and living arrangement). On average, female respondents have higher scores in self-care ability than male respondents.

Table 1. Profile of study samples

Note: SD: standard deviation.

Significance levels: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

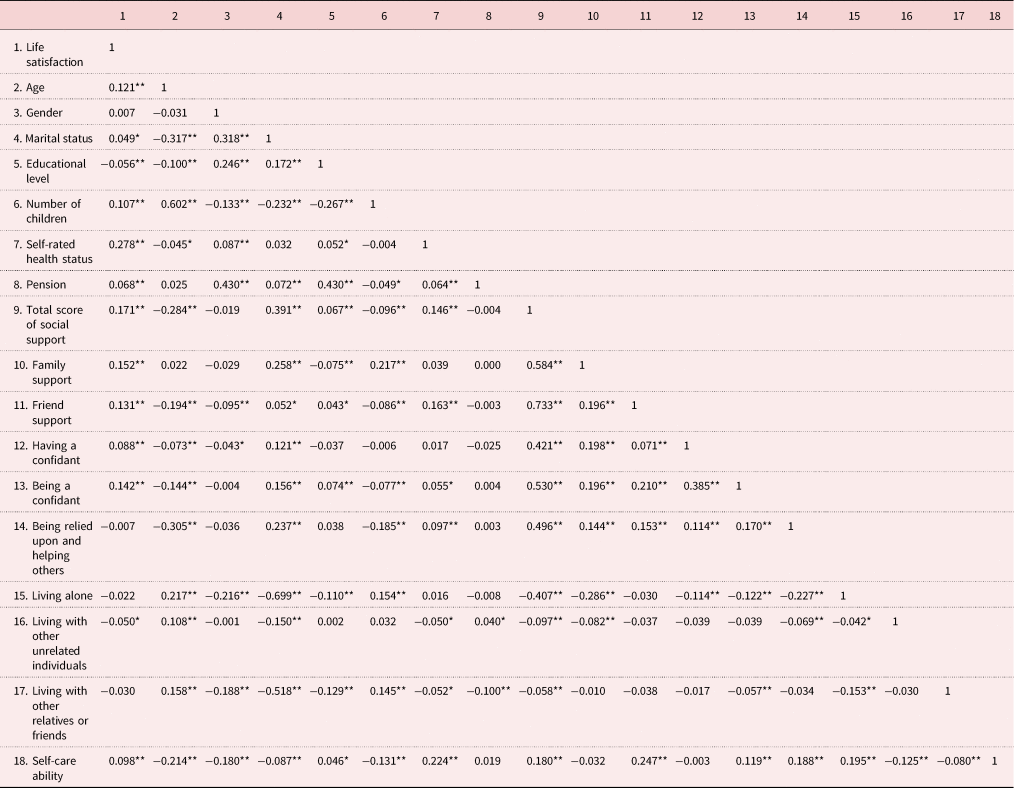

Table 2 shows the results of the correlation analysis. Most variables of interest (pension of respondents, total score of social support, family support, friend support, having a confidant, being a confidant, living with other unrelated individuals, and self-care ability) were significantly correlated with life satisfaction, except for being relied upon and helping others, living alone, and living with other relatives or friends. Among the control variables, educational level was negatively correlated with life satisfaction. The other factors, such as age, number of children and self-rated health status, were positively correlated with life satisfaction. Marital status was also found to be significantly related to life satisfaction.

Table 2. Bivariate correlations among potential factors of life satisfaction

Significance levels: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Factors associated with life satisfaction

On the basis of the correlations above, hierarchical regressions were performed to examine the potential factors of life satisfaction. Six models were run, and the results are shown in Table 3. Model 1 was to examine variables of interest (pension of respondent, total score of social support and self-care ability). Then, we break total score of social support into different sub-dimensions in Model 2. To examine the moderation of gender, Models 3–6 include different interaction terms with gender. As shown in Model 1 – the baseline model – pensions, social support and self-care ability have significant positive associations with life satisfaction. In addition, age, marital status, educational level and self-rated health status were also found to be associated with life satisfaction. Respondents of older age were more satisfied with life. Respondents with a lower educational level had greater life satisfaction, and especially those who were married and those with a primary school education or below were most satisfied with life. This is different from previous findings on education (Chou and Chi, Reference Chou and Chi1999; Ng et al., Reference Ng, Tey and Asadullah2017). One explanation might be that in China, compared to older adults with higher education, those less educated may tend to be more content with what they have if both are in the same circumstances. Older adults with higher levels of self-rated health status were more satisfied with life.

Table 3. Hierarchical regression analysis of life satisfaction

Notes: 1. Self-care ability in daily life was measured by 15 items related to older adults’ activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living (referring to ADL and IADL scales). Ref.: reference category.

Significance levels: † p < 0.1, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

In Model 2, family support and friend support were positively related to life satisfaction. As for interdependent social support, being a confidant is positively related to life satisfaction, while ‘being relied upon and helping others’ is negatively associated with life satisfaction. Probably, being a confidant, which means that a person is involved in the decision-making process of others, increases one's sense of self-worth and feelings of importance. Being relied upon and helping others, to some extent, may increase older adults’ sense of burden.

Model 3 considered the interaction of gender with respondents’ pension. It showed that the interaction was insignificant, indicating that the pension is of the same importance to both older men and women. Model 4 included the interaction of gender with the total score of social support, and this interaction was statistically insignificant. It seems to indicate that there is no gender difference in the relationship between social support and life satisfaction. However, in fact, the sub-dimensions do have some gender-specific patterns, as shown in Model 5. It shows that family support was more important to older men's life satisfaction. Figure 1 shows that with the increase in family support, life satisfaction of older men would have a larger improvement than that of older women. The interaction term regarding friend support is not significant. Besides, the interaction between gender and being a confidant was significantly negative. Figure 2 visualises this interaction. It can be seen that with the increase in the frequency of being a confidant, older women's life satisfaction improves faster.

Figure 1. The interaction between family support and gender.

Figure 2. The interaction between being a confidant and gender.

We also tested the interaction between gender and living arrangement variables (i.e. ‘living alone’, ‘living with other unrelated individuals’ and ‘living with other relatives or friends’). The interaction between gender and living alone was found to be negative, implying that living alone may have stronger negative impact on older men's life satisfaction than on women's. This finding was consistent with previous studies (Sonnenberg et al., Reference Sonnenberg, Deeg, Van Tilburg, Vink, Stek and Beekman2013). Considering the high correlations between family support and living arrangement variables, we only chose to show the interactions between gender and family support. The interactions between gender and living arrangement are shown in Table S1 in the online supplementary material.

As shown in Model 6, self-care ability has a positive association with older women's life satisfaction but a slight negative association with older men's. This gender difference is more clearly illustrated in Figure 3. With the increase in self-care ability, women's life satisfaction increased rapidly but older men's life satisfaction declined slightly. We guess that this gender difference might be related with some activities included in the IADL scale that have strong feminine characteristics. Therefore, to test this, we made a further exploration by constructing another two variables related to self-care ability in the regression models (shown in Table S2 in the online supplementary material). One variable was measured by only four items: activities of meal preparation, housekeeping, laundry and grocery shopping (Model 8a in Table S2 in the online supplementary material), and the other variable was measured by the other 11 items (Model 8b in Table S2 in the online supplementary material). Model 8a shows that the self-care ability (when only including four activities with feminine characteristics) has a significant positive association with life satisfaction of older women but a significant negative association with that of older men. Model 8b shows that the self-care ability (when excluding the four activities with feminine characteristics) has positive associations with the life satisfaction of both older men and women, although the association is less strong for older men. This finding confirms our guess.

Figure 3. The interaction between self-care ability and gender.

Discussion and conclusion

Based on the data collected in Yanshan, Beijing, this study examined the associations of pensions, social support and self-care ability with older adults’ life satisfaction in urban China. This study contributes to the existing literature by adopting a gender perspective to investigate the roles of these factors comprehensively. The results highlight the moderation role of gender in the Chinese context, generating implications also relevant to other Asian societies.

Our analysis has again evidenced that pensions, social support and self-care ability do play positive roles in older adults’ life satisfaction. As for the different dimensions of social support, it is found that both family support and friend support are important to older adults’ life satisfaction, despite some gender differences in the magnitude of their associations. The interdependent social support that is often underinvestigated is actually a predictor of life satisfaction that cannot be ignored. In particular, the confidant relationship (particularly being a confidant) is positively associated with life satisfaction, while being relied upon and helping others is negatively related to one's life satisfaction. This indicates that not all facets of social support would have a positive impact on life satisfaction of older adults

Regarding pensions, the first hypothesis is partially supported. Consistent with previous studies (Zhang and Liu, Reference Zhang and Liu2007; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Zhou and Yiming2016; Han, Reference Han2020), the pension was found to be associated with life satisfaction. But there is no significant gender difference in this association. This implies that an increase in the pension is likely to improve the quality of life of both older men and women in urban China, where, compared to rural areas, the family size is smaller and the family support system is weaker. Nonetheless, Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Zhou and Yiming2016) have found that in China, the older women's pension is much lower than the older men's and suggested that gender equality in pensions should be promoted. Zhao and Zhao (Reference Zhao and Zhao2018) have shown that one-third of the gender gap in pensions is explained by women's fewer years of employment and lower salaries. Thus, improving gender equality in the labour market would narrow down the gender gap in pensions for the younger cohorts when they retire in the future. However, with rapid population ageing and labour force shrinking, the pension system in China may not be financially sustainable in the long term, thus resulting in the falling pension replacement rate. Therefore, the government may have to consider extending the retirement age, optimising the pension funds investment and raising the fertility rate.

The second hypothesis regarding social support is partially validated. It is found that the association between family support and life satisfaction is stronger for older men than for older women while the association between friend support and life satisfaction does not differ across gender. As men retire and enter the family sphere, the time they spend at home will increase much more compared to women. Their contact with work colleagues will reduce, while contact with family members will increase in daily life. This change in older men's social networks during the retirement years indicates that maintaining good family relationships and receiving sufficient family support are likely to enhance their life satisfaction. This finding is consistent with the results from Oshio (Reference Oshio2012) in Japan and Lu et al. (Reference Lu, Jiang, Lou, Zeng and Liu2018) in urban China. But Guo et al. (Reference Guo, Chi and Silverstein2017) found that in rural China older women benefited more psychologically than older men from close international relationships (one type of family support), which is probably due to a limited arena of social relations and activities for women in rural areas. Sonnenberg et al. (Reference Sonnenberg, Deeg, Van Tilburg, Vink, Stek and Beekman2013) have found that in Amsterdam in the Netherlands, older men are sensitive to family support, particularly spousal support. Such inconsistency regarding findings on family support could be due to different social contexts (e.g. Western versus Asian, rural versus urban). Although the focus of this study is not on the contextual difference in the role of family support, future studies could try to investigate this topic. Moreover, being a confidant has a stronger positive relationship to older women's life satisfaction than to men's. The existing literature has documented that women place more importance on relatedness and may also care more about the quality of relationships (Cheng and Chan, Reference Cheng and Chan2006). To women, being a confidant may provide a feeling of deep involvement in a close relationship, thus promoting their life satisfaction to a larger extent.

The third hypothesis, that self-care ability has a stronger positive association with older women's life satisfaction than with men's, is supported by our results. Precisely speaking, it is found that self-care ability has a positive association with women's life satisfaction but a negative association with men's. The latter seems counterintuitive. However, it should be noted that many daily activities, such as meal preparation, laundry and housekeeping, which are used to measure self-care ability, have feminine characteristics in the Chinese context. Older men who perform these activities on their own may feel a loss of face (mianzi) and damage to their self-image, thus reducing their life satisfaction (although they can function very well in daily life). Geist and Tabler (Reference Geist and Tabler2018) have found that in the United States of America older men are also reluctant to share housework. Equal division of housework, especially in activities of preparing meals, doing laundry and cleaning, is realised only when older women are in poor health. This indicates that it is not easy for older women to cut back domestic workload even when older men have resources and time after retirement. Due to data limitation, we do not have information regarding the spouses’ health status in the survey, therefore we do not why some older men do much housework. Nonetheless, the negative relationship between older men's self-care ability and life satisfaction deserves special attention, and it may also be observed in other countries. Therefore, when applying the ADL and IADL scales to measure self-care ability, such a gender difference should be noted. Moreover, researchers and practitioners should be aware of this gender difference in service delivery and intervention programme development for improving their life satisfaction.

This study has some limitations. First, as the analysis was based on a cross-section survey, we were unable to reveal causality between the factors and life satisfaction. However, with follow-up surveys in the future, this concern can be addressed with longitudinal data. Second, as the survey was conducted in Beijing, this study restricts the attention to older adults living in urban China and does not include those living in rural areas in the analysis. Future studies could try to investigate these factors in rural China, where gender norms and patriarchal culture are even stronger. Third, our findings about the current cohort of older adults should be interpreted with caution and may not be fully applicable to younger cohorts as China is experiencing dramatic demographic and socio-economic changes. Fourth, some other public schemes, such as old-age allowance, voucher/cash subsidy for care services and long-term care insurance, could also provide economic support for older adults, which have not been considered in this study because of data inadequacy. More comprehensive measurements of economic support from public schemes are expected in future studies.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X20001877

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful to the comments by the reviewers.

Financial support

This work was supported by ‘Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities’ (reference number 03000-310422109); and ‘Elderly Care Planning Project’ (reference number 03000-227900009).

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval was obtained for this research from the Research Ethics Committee, School of Social Development and Public Policy, Beijing Normal University (reference number SSDPP-HSC2018003).