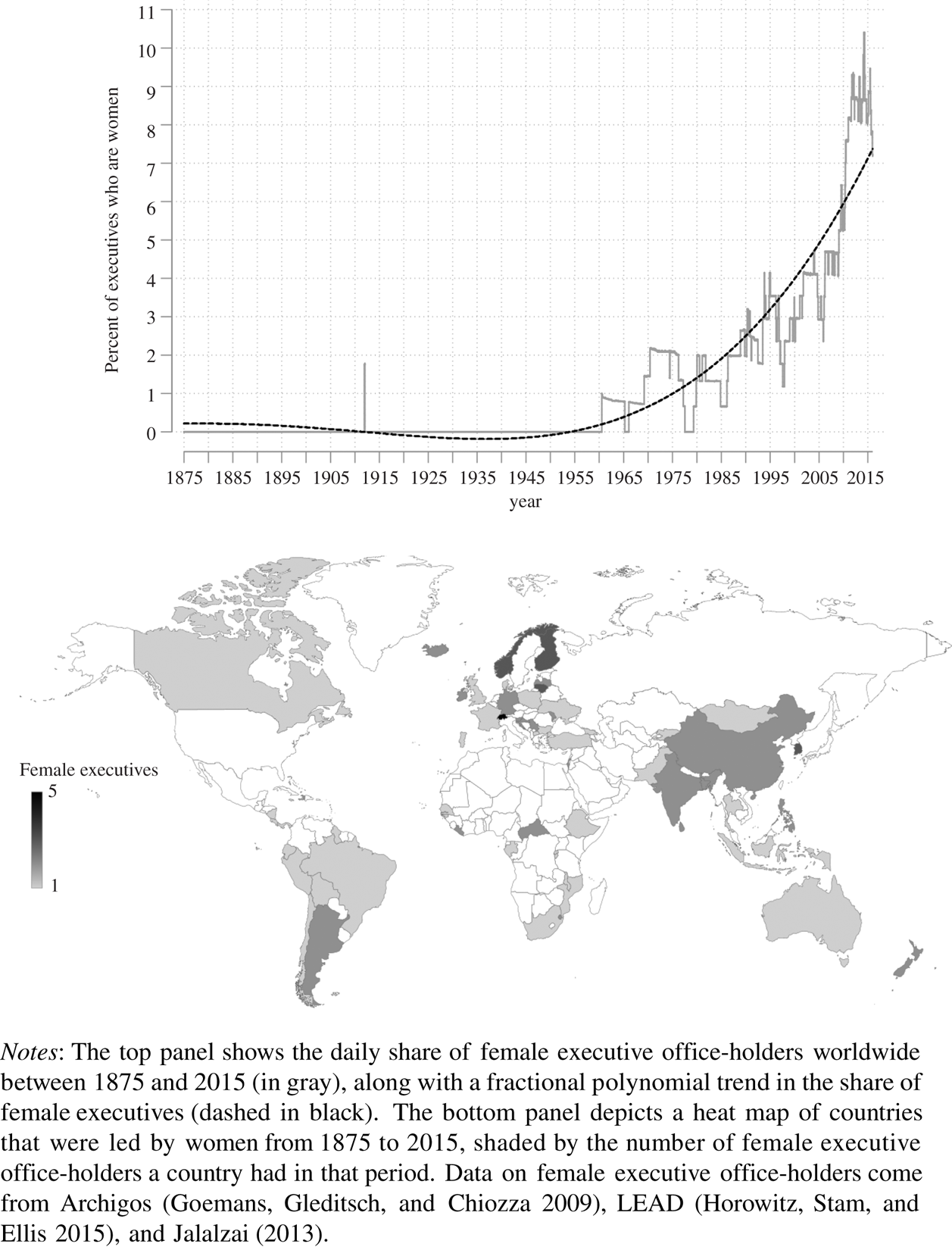

During the 1984 presidential campaign, Geraldine Ferraro, the first major-party female vice-presidential candidate in US history, was asked at a debate, “do you think in any way that the Soviets might be tempted to try to take advantage of you simply because you are a woman?”Footnote 1 Similar questions dogged her entire campaign. In a follow-up on Meet the Press, hosts questioned whether Ferraro was “strong enough to push the [nuclear] button.”Footnote 2 These statements reveal a pervasive gender stereotype: that men are better equipped to handle national security issues than women.Footnote 3 While gender stereotypes persist, the number of female political leaders has grown markedly over time. As Figure 1 indicates, women occupied nearly 10.5 percent of all executive offices worldwide in 2015, and have served as head of state in sixty-six countries since 1875.Footnote 4 The growing prevalence of women in high political office thus raises important questions about the role of leaders’ gender in the conduct of war and peace. Toward this end, we investigate how common gender stereotypes affect crisis-bargaining dynamics. Specifically, we address a gap in the literature by presenting the first evidence of how gender stereotypes affect leaders’ abilities to generate audience costs.

Figure 1. Female leadership is becoming more common over time and across countries

Audience costs are the domestic political punishments leaders face for making a threat and then backing down.Footnote 5 Kertzer and Brutger identify two components of audience costs: inconsistency and belligerence.Footnote 6 Inconsistency costs, the traditional audience cost, are those leaders pay for making threats but failing to follow through. These threats tie leaders’ hands because inconsistency costs are paid only if leaders back down.Footnote 7 Belligerence costs are those leaders pay for threatening force in the first place. These are sunk costs since leaders pay them immediately after issuing a threat.Footnote 8 Given that leaders always have an incentive to bluff, the benefit of being able to generate higher audience costs is greater credibility at the bargaining table, since only genuinely resolved leaders would be willing to tie their hands and sink costs.Footnote 9 Generating audience costs also allows leaders to better communicate their intentions, thereby reducing the chances that miscalculation will lead to war.Footnote 10 The disadvantage—especially with inconsistency costs—is that backing down from threats becomes more difficult as leaders become “locked into their position[s],” which can hamper efforts to de-escalate existing crises.Footnote 11 Drawing on insights from political science and psychology, we argue that female leaders pay greater inconsistency costs than male leaders facing male opponents. If female leaders demonstrate “weakness” by backing down from threats, they activate descriptive gender stereotypes about women's ill-preparedness for the demands of high office generallyFootnote 12 and conflict in particular.Footnote 13 Male leaders who act inconsistently, by contrast, are judged less harshly because men's failures are more often attributed to situational factors beyond their control rather than dispositional factors related to their character.Footnote 14 In other words, female leaders are held to a higher standard than their male counterparts and are punished more for perceived policy failures, like inconsistency.

But gender stereotypes are not wholly irrelevant for male leaders. We also contend that male leaders pay greater inconsistency costs for backing down against women than they do for backing down against fellow men. Since gender stereotypes dictate that women are less capable in the realm of national security, and that men should be strong and assertive, backing down against women is viewed as emasculating and seen as a negative signal of a male leader's competence. This kind of dynamic is evident even in schoolyard disputes where “you lost to a girl” is a common pejorative.

Finally, given that female leaders may have political incentives to “act tough” during international crises to combat gender-stereotypical expectations of weakness, and male leaders have incentives to avoid appearing weak against female foes, we argue that female leaders will pay lower belligerence costs than male leaders facing fellow males, and the same is true for male leaders acting belligerently against female leaders.Footnote 15

To isolate the effects of gender stereotypes on public evaluations of leaders in interstate disputes, we conducted two survey experiments. Experiments help overcome two related issues that plague observational studies on this topic: sample size and selection issues.Footnote 16 Because war and female leadership are historically rare, and since women both attain and perform in high political office nonrandomly, the feasibility of inference from observational data is limited. In an experimental setting, we can randomly vary leaders’ genders and crisis behaviors while holding other factors constant. Our primary experiment, which includes 2,342 subjects recruited through the Time-Sharing Experiments for the Social Sciences (TESS) panel conducted with the National Opinion Research Center (NORC) at the University of Chicago, reveals support for our theory. Female leaders pay greater inconsistency costs for backing down from threats than male leaders do against fellow men, and likewise for male leaders acting inconsistently against female leaders. These results also held in a pilot experiment we conducted on 1,607 Amazon Mechanical Turk (mTurk) subjects, lending further confidence in our findings.

Our results with respect to belligerence costs are somewhat more mixed, but also generally support our hypotheses. Results from our TESS experiment reveal that female leaders, and male leaders facing female leaders, pay lower belligerence costs than male leaders facing fellow men. A similar pattern emerges in our mTurk study, though the results are not statistically significant. Sentiment analysis conducted using open-ended responses from our TESS study corroborate our main findings on inconsistency and belligerence.

In sum, this study makes four principal contributions. First, we extend the bargaining literature by applying the logic of audience costs to an important empirical trend: the growing number of women in high political office. A large literature on audience costs has examined how these vary with regime type;Footnote 17 electoral structure;Footnote 18 media environment;Footnote 19 leaders’ rhetoric;Footnote 20 and audience characteristics.Footnote 21 However, no study we are aware of has analyzed the impact of gender and gender stereotypes on leaders’ abilities to generate audience costs.Footnote 22 More broadly, our study extends the burgeoning experimental literature on gender.Footnote 23

Second, our findings extend those of Kertzer and Brutger and lend further support for the notion that it is essential to disaggregate audience costs into inconsistency and belligerence in order to draw appropriate inferences from audience-cost experiments.Footnote 24 Simply looking at overall audience costs obscures the key fact that female leaders generally pay greater inconsistency costs and lower belligerence costs. Because these two effects are countervailing, a nondisaggregated replication of our study would miss critical nuances in the role of gender stereotypes during crises.

Third, our results strengthen the emerging consensus that leader attributes matter in important ways.Footnote 25 Research examines how factors like age,Footnote 26 post-tenure security,Footnote 27 and attitudinal dispositionsFootnote 28 affect leaders’ behavior, but pays less attention to gender. Melding the rich literature on gender and politics with scholarship on leaders, our findings highlight the importance of gender and gender stereotypes in international relations.Footnote 29 We hope future scholarship will pay closer attention to the roles of gender and gender stereotypes in shaping leader conduct.

Fourth, this study has implications for debates about whether increasing gender equality in executive office holding will lead to less belligerent foreign policies and more peace, or the reverse. Supporters of the “women-as-peacemakers” view, like Steven Pinker, argue that “over the long sweep of history, women have been and will be a pacifying force. Traditional war is a man's game.”Footnote 30 This perspective implies that bioevolutionary factorsFootnote 31 and socialization processesFootnote 32 incline women toward peace, so a world with more female leaders should be more pacific. Alternatively, supporters of the “iron ladies” view contend that more belligerent female leaders are selected into office,Footnote 33 and that once in office, female executives face incentives to combat gender stereotypes by adopting hawkish policies.Footnote 34 Our findings help reconcile these perspectives.

On one hand, our findings suggest that women's increasing roles in executive office may have a pacifying effect because female leaders have bargaining advantages. Since they are punished more for inconsistency, female leaders are better able to tie hands, which is the most efficient means for establishing credibility in crises.Footnote 35 Enhanced credibility should lead to more effective communication, reduced uncertainty, and a lower chance of international conflict. This is especially the case since male leaders competing against female leaders are also better able to generate inconsistency costs, facilitating clear communication. On the other hand, the mechanism driving this relationship is not that women are innately pacifistic or socialized to avoid aggression, but that they face political pressure to combat gender stereotypes by acting tough. Female leaders have political incentives to behave hawkishly, rendering their threats more credible, but also locking them into their positions and making it harder to de-escalate after threats have been made.Footnote 36

Theory

Stereotypes are pervasive, durable, shared beliefs held about groups on the basis of certain (often ascriptive) characteristics. These biases typically incorporate both descriptive and prescriptive dimensions, meaning gender stereotypes influence beliefs about both what men and women are perceived to be like and what they ought to be like.Footnote 37 In complex environments like international crises, stereotypes serve as heuristic devices, guiding decision making on the basis of simplified categories.Footnote 38 Our intuition that evaluations of leaders’ behavior are influenced by gender stereotypes and the normative expectations these biases conjure builds from these social psychological insights. Specifically, we draw on Heilman's Lack of Fit model.Footnote 39

The Lack of Fit model suggests that individuals rely on stereotypes to form expectations of performance when assessing leaders.Footnote 40 Even though the number of female executives has increased over time, descriptive stereotypes implying women are ill-suited for the realm of national security endure. Specifically, many studies find that men are viewed as tougher and better able to handle military crises than women.Footnote 41 For instance, Lawless finds that 61 percent of respondents believe that men are better prepared to respond to military crises than women; just 3 percent of respondents believe women are better able to handle military crises than men.Footnote 42 Likewise, those who consider national security as the top issue facing the country are significantly more likely to believe that a male president would do a better job than a female president,Footnote 43 and the public prefers male leadership during times of heightened terrorist threat.Footnote 44

As the Lack of Fit model implies, these findings reflect a perceived discordance between the qualities women possess and the qualities necessary for success in foreign affairs. Particularly, gender-stereotypical expectations that men are strong, aggressive protectors, and women are delicate and require protection, drive divergent beliefs about how male and female leaders will perform in military crises.Footnote 45 Because of female leaders’ perceived “lack of fit” for the role of commander-in-chief, they face heightened scrutiny for their decisions, meaning women in power are often held to higher standards and have to outperform men in order to be evaluated equally highly.Footnote 46

Perceptions of women's “lack of fit” for positions of leadership during crises are compounded by the fact that women's failures are more likely to be attributed to dispositional factors like incompetence, while men's failures are more likely to be attributed to situational factors beyond their control.Footnote 47 This means that observers will be likely to view female leaders’ failures as confirming gender-stereotypical expectations about women's “lack of fit,” while male leaders’ failures may not shift expectations about male fitness for leadership.

Further, gender stereotypes may also operate as second-order beliefs, or beliefs about what others believe. This means that even if individuals do not personally subscribe to gender stereotypes—though many do—they may behave in accordance with the Lack of Fit model because they believe that other individuals and world leaders hold gender stereotypes. In the context of a military crisis, for example, a respondent might hold a female leader to a higher standard not because they personally believe women are ill-suited to the role of commander-in-chief, but because they believe foreign leaders subscribe to gender-stereotypical expectations about women's lack of fit, and so fear any misstep will cause the female leader to be viewed as an irresolute and incredible target.Footnote 48

To combat gender-stereotypical expectations of weakness and minimize criticism, female leaders have political incentives to act tough during international crises.Footnote 49 For example, female chief executives are more likely to increase defense spendingFootnote 50 and initiate militarized interstate disputes than male leaders.Footnote 51 Likewise, high-ranking female foreign policymakers—like Jeane Kirkpatrick, Madeline Albright, Condoleezza Rice, and Hillary Clinton—often advocate more aggressive foreign policies than their male counterparts.Footnote 52 In the medieval period, married queens were more likely than kings to be aggressors in interstate conflicts.Footnote 53 Examples of modern “iron ladies”—like Margaret Thatcher, Indira Gandhi, and Golda Meir—and ancient “warrior queens”—like Cleopatra, Boudica, and Isabella of Spain—lend further credence to the view that female leaders have political motivations to pursue relatively hard-line policies to combat gender stereotypes.Footnote 54 Mark Penn, Hillary Clinton's chief strategist in 2008, argued that Clinton had political incentives to portray strength:

Regardless of the sex of the candidates, most voters in essence see the presidents as the “father” of the country. They do not want someone who would be the first mama, especially in this kind of world … [Thatcher] represents the most successful elected woman leader in this century—and the adjectives that were used about her (Iron Lady) were not of good humor or warmth, they were of smart, tough leadership.Footnote 55

The Lack of Fit model suggests that if women demonstrate weakness by, for example, acting inconsistently, support will wane. Because audiences are stereotypically inclined to believe women will fare worse in conflicts, a female leader's failure to follow through will confirm mass suspicions about her “lack of fit” for executive office, and the public will respond punitively, attributing her perceived failures more to dispositional than situational factors. Even individuals who do not themselves believe women are ill-suited for leadership may believe that foreign leaders believe gender stereotypes and will view female leaders as incredible; these individuals will punish female inconsistency because of second-order gender-stereotypical beliefs and extrinsic concerns about reputation. In short, when female leaders perform poorly in international crises by making a threat and then backing down, gender stereotypes are likely to be activated, leading to greater disapproval from the general population than when male leaders behave identically.

From the Lack of Fit model's logic, we derive a number of testable implications about how gender stereotypes affect leaders’ abilities to generate audience costs. In any potential conflict dyad, there are four possible gender combinations: (1) the most common male-male (MM) dyad, involving two male leaders; (2) the female-male (FM) dyad, where the domestic leader is a female and the foreign leader is a male; (3) the male-female (MF) dyad; and (4) the presently rare female-female (FF) dyad.Footnote 56 The male-male dyad, the most common historical combination by far, can be thought of as the baseline group against which we are comparing other dyads.Footnote 57 Our first two hypotheses compare the FM and FF dyads to the MM baseline:

H1a Female leaders pay greater inconsistency costs compared to the MM dyad.

H1b Female leaders pay lower belligerence costs compared to the MM dyad.

While there may be a strategic logic to bluffing, the public typically perceives acting inconsistently by making a threat and then backing down as a policy failure.Footnote 58 Indeed, inconsistency is what scholars commonly think of when they discuss audience costs.Footnote 59 The Lack of Fit model predicts that gender stereotypes will be activated when female leaders behave inconsistently, leading to greater disapproval from the general population than when male leaders behave the same way against fellow men. Thus, female leaders in mixed (FM) and same-gender (FF) dyads should face higher inconsistency costs than male counterparts in same-gender (MM) dyads. Because female executives’ failures are often perceived as dispositional,Footnote 60 women in general are more likely to be perceived as incompetent for acting inconsistently or failing to respond forcefully to aggression. Essentially, when female leaders perform poorly in international crises by backing down, gender stereotypes are activated regardless of the gender of the rival leader, leading to greater disapproval from the general population. There is empirical support for this argument. Carlin, Carreras, and Love find that increases in terrorism—a clear policy failure—reduce the public approval of female but not male leaders.Footnote 61

We also expect that female executives will pay lower belligerence costs compared to the male-male baseline. In traditional audience-cost experiments, including ours, domestic leaders are faced with a clear case of foreign aggression: the invasion of a third country by an adversary. In this context, the Lack of Fit model implies that female heads of state will have political incentives to act belligerently to combat descriptive gender stereotypes that they are weak.Footnote 62 To understand this intuition, think of the inverse of belligerence costs: “inaction costs.” These are the costs that leaders pay for doing nothing in response to the invasion of a third country, relative to making a threat in response and following through on it.Footnote 63 We expect that female leaders will pay greater inaction costs—and consequently lower belligerence costs—because, according to the Lack of Fit model, doing nothing in response to foreign aggression will activate descriptive gender stereotypes of perceived female weakness in military affairs.

We now turn to situations where male leaders face female opponents. Comparing the mixed-gender MF dyad to the male-male baseline, we hypothesize:

H2a Male leaders facing female opponents pay greater inconsistency costs compared to the MM dyad.

H2b Male leaders facing female opponents pay lower belligerence costs compared to the MM dyad.

In this situation, relational stereotypes are relevant. As Ellemers describes, gender stereotypes do not merely prescribe how individuals of different genders are expected to perform in general, but also how they are expected to perform in relation to one another.Footnote 64 Building from the Lack of Fit model's expectation that men are perceived as better equipped to handle national security affairs than women, the logic of relational stereotypes suggests that backing down against a female leader will be viewed as emasculating and a particularly negative sign of a male leader's competence. Put simply, for male targets of female-initiated threats, backing down should be perceived as a sign of weakness, defying expectations about masculine strength and “fit” for leadership according to the Lack of Fit model. Consequently, male leaders have political incentives to act tough against female leaders to avoid perceptions that they backed down against an opponent who people expect to be weaker. Anecdotal evidence corroborates this expectation. In 60 CE, Boudica, a Celtic queen, led an uprising against Rome. Cassius Dio, a Roman historian, wrote of Roman losses to Boudica: “all this ruin was brought upon them by a woman, a fact which in itself caused them the greatest shame.”Footnote 65

This logic also extends to our expectations regarding belligerence costs. We predict that, on balance, male leaders facing female opponents will pay lower belligerence costs compared to the MM baseline. According to the Lack of Fit model, male leaders are likely to be viewed as better suited than women for military crises. Descriptive stereotypes that men are stronger and more capable in military affairs mean male leaders will have political incentives to act belligerently against female leaders to avoid the perception that they feared fighting a weaker opponent. Returning to the hypothetical inverse of belligerence costs, inaction costs, our logic suggests that male leaders should face greater inaction costs—and thus lower belligerence costs—in a crisis against a female initiator because inaction against a female adversary could signal surprising “lack of fit” for the role of commander-in-chief.Footnote 66

By way of illustration, consider Yahya Khan's eagerness to fight Indira Gandhi during the Bangladesh crisis of 1970–71. As he noted, “If that woman [Indira Gandhi] thinks she is going to cow me down, I refuse to take it. If she wants to fight, I'll fight her!”Footnote 67 Clearly, Khan was not afraid of fighting a female leader, as prescriptive stereotypes might suggest. Rather, documentary evidence suggests Khan was motivated by the fear that he would be perceived as weak if he refused to fight Gandhi in the first place, or failed to follow through on his threats once made.

Tables 1 and 2 summarize these hypotheses. In our experimental framework, the domestic leader is the leader whose cost-generating capacities we measure.

Table 1. Inconsistency cost predictions vs. male-male dyad

Table 2. Belligerence cost predictions vs. male-male dyad

Experimental Design

To test our hypotheses, we designed and administered a 3 × 2 × 2 × 2 between-subjects experiment fielded in collaboration with TESS on a pool of 2,342 subjects recruited from NORC's nationally representative AmeriSpeak panel.Footnote 68 Our design and hypotheses were pre-registered with Evidence in Governance and Politics (EGAP).Footnote 69 To maximize comparability, the design and wording of the experiment closely follow that of seminal audience-cost experiments conducted by Tomz and Kertzer and Brutger.Footnote 70 The factors we varied are the United States’ crisis action (stay out, not engage, and engage); the US president's gender; the foreign leader's gender; and the US president's partisan affiliation. We blocked on respondent party identification to ensure approximately equal numbers of Democrats, Independents, and Republicans in each experimental cell. Every respondent was presented with the following introduction:

The following questions are about US relations with other countries around the world. You will read about a situation our country has faced many times in the past and will likely face again. Different leaders have handled the situation in different ways. We will describe one approach US leaders could take in the future and ask whether you approve or disapprove.

The only difference between this introduction and the one utilized by Tomz and Kertzer and Brutger is that instead of telling respondents that “we will describe one approach US leaders have taken,” we told them that “we will describe one approach US leaders could take in the future.”Footnote 71 The reason for this difference is that there have not been any female US presidents in the past and so, to be realistic, our scenario had to be forward looking. With this caveat in mind, we were sanguine about the prospect that respondents would approach scenarios describing female presidents seriously. In three of the last four US presidential elections, a woman has served as a major party presidential or vice presidential nominee, and in all four of the last US presidential elections, female candidates have made serious primary bids.Footnote 72 Further, we fielded our study in August and September 2019, in a period when six women—Elizabeth Warren, Amy Klobuchar, Kamala Harris, Kirsten Gillibrand, Tulsi Gabbard, and Marianne Williamson—were Democratic primary candidates for the 2020 presidential election.Footnote 73 Despite the fact that the US has never had a female president, we think concerns that respondents did not take our prompt seriously are mitigated because of the realistic possibility of a female president.

After the introduction, we presented respondents with information about a hypothetical international crisis scenario:

A country sends its military to take over a neighboring country. The attacking country is controlled by a [female/male] leader.

Next, we presented respondents with the identity of the US president:

The [Republican/Democratic] US President, [Erica/Eric, Stephanie/Steven] Smith…

Following Trager and Vavreck, we randomized the party of the US president.Footnote 74 This is particularly important for analyzing the effects of gender since women are often perceived as more liberal than men.Footnote 75 The name combinations we utilized are similar, but clearly primed gender.Footnote 76 They should not, however, have primed any notable politician because no former US presidents or vice presidents share any of the names we employed. Although Hillary Clinton is the most prominent female politician in US history, an advantage of fielding this study during the 2020 campaign cycle is that the large number of female candidates running should reduce the extent to which respondents thought solely about Clinton when evaluating the crisis scenario. Research by Kromer and Parry also demonstrates that priming Hillary Clinton does not aggravate or diminish gendered expectations.Footnote 77 We randomized name assignment within the US president's gender condition to mitigate any effects of name choice.

After presenting respondents with the identity of the US president, we randomly assigned them to one of three different scenarios for how the United States responds. To distinguish between inconsistency and belligerence costs, we employed the same three categories that Kertzer and Brutger used: stay out, not engage, and engage.Footnote 78 In the stay-out scenario, the US president promises to refrain from intervening in the crisis and abides by this promise:

…says the United States will stay out of the conflict. The attacking country continues to invade. In the end, [Erica/Eric, Stephanie/Steven] Smith decides not to send troops, and the attacking country gains 20 percent of the contested territory.

In the not-engage scenario, the US president promises to deploy troops to resolve the crisis, but fails to do so:

…says that if the attack continues, the United States military will push out the invaders. The attacking country continues to invade. In the end, [Erica/Eric, Stephanie/Steven] Smith does not send troops, and the attacking country gains 20 percent of the contested territory.

In the engage scenario, the US president promises to deploy troops to resolve the crisis and follows through:

…says that if the attack continues, the United States military will push out the invaders. The attacking country continues to invade. In the end, [Erica/Eric, Stephanie/Steven] Smith orders the US military to engage. The attacking country gains 20 percent of the contested territory and the US experiences zero casualties.

Note that following Kertzer and Brutger, we hold constant outcomes in all three conditions to isolate the effect of inconsistency and belligerence.Footnote 79 Like previous studies, our outcome measures are binary and seven-point Likert scales to measure approval or disapproval of the US president's handling of the crisis. Within this framework, inconsistency costs equal disapproval in the not-engage condition minus disapproval in the engage condition. Belligerence costs equal disapproval in the engage condition minus disapproval in the stay-out condition. Audience costs equal inconsistency plus belligerence costs.

Experimental Results

Table 3 displays the percentage point difference in mean disapproval for the FM, FF, and MF dyads compared to the MM baseline.Footnote 80 Positive values indicate that audience, inconsistency, or belligerence costs are greater for the respective dyad relative to the MM baseline, and negative values indicate that these costs are lower. In accordance with previous studies, Table 3 collapses the seven-point measure of approval or disapproval into a binary measure of disapproval to more clearly illustrate substantive effects.Footnote 81 Substantively identical results emerge with the full seven-point measure.Footnote 82

Table 3. Percentage point difference in mean disapproval compared to the male-male baseline

Notes: Results depict average treatment effects (ATE) for a binary measure of disapproval calculated from 2,000 bootstraps. The main quantities reflect the average percentage point difference in disapproval for the respective dyad in the left column compared to the male-male baseline. For example, 20.7 percentage points more respondents disapprove of a female president acting inconsistently against a foreign male leader than a male president acting inconsistently against a foreign male leader. Mean disapproval for the two experimental groups used to calculate ATE are in parentheses. For example, average disapproval of a female president behaving inconsistently against a foreign male leader was 61.9%, while average disapproval of a male president behaving inconsistently against a foreign male leader was 41.2%. * p < .10; ** p < .05; *** p < .01.

We begin by examining H1a and H2a, which hold that inconsistency costs should be greater in the FM, FF, and MF dyads than in the MM baseline. Column 2 in Table 3 demonstrates statistical support for these hypotheses, as well as substantively large effects. Disapproval is 20.7 percentage points greater for a female president acting inconsistently against a foreign male leader compared to a male president acting inconsistently against a fellow male (p ≈ 0.001; 95% bootstrapped CI: 6.7, 34.2). Similarly, disapproval is 18.2 percentage points greater for a female president acting inconsistently against a foreign female leader than the MM baseline (p ≈ 0.008; 95% bootstrapped CI: 3.4, 32.2). Further, male presidents who act inconsistently against foreign female leaders face disapproval rates that are 15.4 percentage points greater compared to when they act inconsistently against male leaders (p ≈ 0.018; 95% bootstrapped CI: 1.2, 29.7).

Our findings with respect to belligerence costs also comport with our hypotheses. Recall that H1b and H2b predict that belligerence costs will be lower in the FM, FF, and MF dyads compared to the MM baseline. In accordance with this expectation, disapproval is 14.4 percentage points lower for a female president acting belligerently against a foreign male leader compared to a male president acting belligerently against a fellow male (p ≈ 0.026; 95% bootstrapped CI: -29.0, 1.0). For a female president acting belligerently against a fellow female, disapproval is 13.6 percentage points lower than the baseline (p ≈ 0.037; 95% bootstrapped CI: -28.9, 1.4). Finally, disapproval is 10.8 percentage points lower for a male president acting belligerently against a foreign female leader compared to a male president acting belligerently against a fellow male (p ≈ 0.079; 95% bootstrapped CI: -25.7, 3.7).

We did not hypothesize about total audience cost effects because we anticipated the effects of inconsistency and belligerence costs to countervail one another. Specifically, because we expected that inconsistency costs would be greater in the FM, FF, and MF dyads compared to the MM baseline, while belligerence costs would be lower, our theory predicts null or small aggregate effects. These expectations bear out. In column 1 of Table 3, we examine whether there are any differences in total audience costs across dyads. Consistent with our expectations, no statistically significant differences emerge when we analyze total audience costs. This null, however, masks critical heterogeneity. Thus, our results provide additional support for Kertzer and Brutger's argument that it is essential to disaggregate audience costs.Footnote 83 Simply looking at overall audience costs obscures the fact that female leaders pay greater inconsistency costs and lower belligerence costs because these two effects work against one another.

To ensure the robustness of our core findings, we take a number of steps. First, we verify that results are substantively similar when we use the full sample of respondents, rather than only those who passed the attention check.Footnote 84 Second, we show that substantively identical results emerge when we employ the full seven-point measure of approval or disapproval.Footnote 85 Third, we show that results hold in a regression that controls for factors like the partisan identity of the US president in the scenario; the respondents’ gender, age, education, partisanship, level of sexism, and level of militant assertiveness; and whether our sexism battery was administered pre- or post-treatment.Footnote 86 Fourth, we present results from our exploratory mTurk pilot study fielded in February 2019, which are substantively similar, though yield more modest support on belligerence costs.Footnote 87 The robustness of our results across these tests builds confidence in our main findings.

Sentiment Analysis

To further probe the robustness of our findings, we asked respondents (after presenting each crisis scenario) to provide four words that they believe best described the US president.Footnote 88 Open-ended questions can help provide a more direct view into a survey subject's beliefs.Footnote 89 Using the tidytext package in R, and a dictionary developed by Liu, we classified respondents’ word answers as positive or negative.Footnote 90 As an alternative to our primary measurement strategy, which relies on a forced-choice Likert item, we use the average sentiment score for each respondent calculated from the mean of the four words given. Each respondent's sentiment score about the president in the crisis scenario serves as an alternative way to operationalize their disapproval of the president's crisis action. Table 4 presents the results from our sentiment-analysis exercise. Positive values indicate that audience, inconsistency, or belligerence costs are greater for the relevant gender dyad compared to the MM baseline, and negative values indicate that these costs are lower. Results in Table 4 are substantively identical to our estimates in Table 3, lending further confidence in the robustness of our main results.

Table 4. Percentage point difference in mean negative sentiment compared to the male-male baseline

Notes: Results depict average treatment effects (ATE) calculated from 2,000 bootstraps. The main quantities reflect the average percentage point difference in negative sentiment for the respective dyad in the left column compared to the male-male baseline. For example, negative sentiment was fourteen percentage points higher for a female president acting inconsistently against a foreign male leader than a male president acting inconsistently against a foreign male leader. Mean negative sentiment for the two experimental groups used to calculate ATE are in parentheses. For example, average negative sentiment of a female president behaving inconsistently against a foreign male leader was 56.8%, while average negative sentiment of a male president behaving inconsistently against a foreign male leader was 42.8%. * p < .10; ** p < .05; and *** p < .01.

Internal Validity

Experiments are the gold standard for causal identification but they are not entirely immune from confounding. In our context, the most likely source of confounding is a lack of information equivalence, where manipulating one factor (e.g., gender) leads respondents to update their beliefs about other relevant, but not experimentally manipulated, dimensions.Footnote 91 Our experimental design explicitly controlled for one possible confounding factor—the party of the US president—but two other possibilities stand out. First, it is possible respondents will think that female presidents are more likely to be nonwhite than male presidents. If this is the case, then it could be racial stereotypes that drive higher inconsistency costs for female leaders rather than gender. Second, survey subjects might infer that foreign countries led by a woman are more likely to be democratic. To rule out these possibilities, we asked respondents placebo questions at the end of the survey to gauge their perceptions about the US president's race and the foreign country's regime type. Promisingly, we find no systematic evidence of confounding. Female US presidents were only marginally more likely to be perceived as nonwhite (ρ ≈ 0.05), and foreign countries led by women were only slightly more likely to be perceived as democratic (ρ ≈ 0.11). These correlations demonstrate that there is no widespread association between the gender of US presidents and race, or the gender of foreign leaders and regime type. More importantly, our results are robust to the inclusion of controls for these variables in a regression.Footnote 92

Three other potential concerns also warrant mention. First, it is possible that respondents intuited from our experiment that our focus was on gender. This possibility raises the specter of experimenter demand effects, which occur if respondents surmise researchers’ hypotheses and adjust their behavior to validate those expectations. Recent work, however, suggests respondents are often unable to adjust behaviors to conform with researchers’ expectations, so demand effects are unlikely to bias our results.Footnote 93 A second, related concern stems from social desirability. Respondents could have intuited our focus on gender stereotypes and adjusted their behavior to appear less sexist. While possible, this would bias against our inconsistency cost results because respondents seeking to appear less sexist would be more approving of women's crisis actions. Order effects are a third potential concern because some respondents received a battery of questions designed to measure sexism before treatment, while others received the battery after treatment. However, assignment to the order of the sexism battery was randomized, and our results hold when the order is controlled for in a regression.Footnote 94

Heterogeneous Effects

In the appendix, we analyze whether the effects of gender stereotypes on audience costs vary across respondent subgroups, focusing on five respondent characteristics: militant assertiveness, partisanship, sexism, age, and respondent gender. Contrary to our expectations, we find no evidence that our hypotheses are stronger among Republican, more sexist, older, or male respondents.Footnote 95 These null results, especially with respect to sexism, are consistent with gender stereotypes mattering more as second-order beliefs. We cannot test this contention directly, but it is a ripe avenue for future research. We also replicate Kertzer and Brutger's findings: Democrats and individuals low in militant assertiveness impose higher belligerence costs, and Republicans and individuals high in militant assertiveness impose higher inconsistency costs.Footnote 96 By replicating Kertzer and Brutger's well-known findings about partisanship and militant assertiveness in the context of disaggregated audience costs, we build confidence in our design.

Conclusion

As the number of women in executive office grows, it is imperative to consider how gender dynamics impact international politics. This study provides the first causal evidence that gender stereotypes affect leaders’ abilities to generate audience costs. Our most important finding is that female leaders, and male leaders facing female leaders, pay greater inconsistency costs for backing down from threats than male leaders do against fellow men. These results have critical implications for theory and policy, and speak to calls for more nuance in understanding the reasons men and women have for fighting.Footnote 97

The evidence in this research note suggests that female leaders hold important advantages and disadvantages in bargaining situations. On one hand, their greater ability to generate inconsistency costs means women should find it easier to tie their hands in crises, and in turn are better able to establish credibility and signal resolve. As a result, female leadership may facilitate peace by making it easier to communicate intentions ex ante. On the other hand, because women face higher costs for backing down from threats, and lower costs for initiating in the first place, gender stereotypes may contribute to military adventurism and conflict risk because female leaders will find it tempting to make threats and difficult not to escalate once threats have been made.

As far as theory, these findings build on the rich literature on feminist approaches to international relations, and bear critically on the debate over the peace-inducing effects of female leadership in world politics. While some scholars contend that greater equality in holding executive office will facilitate peace because women are innately less belligerent than men for bioevolutionaryFootnote 98 or social reasons,Footnote 99 our work in this piece points to a more complicated view. Because female leaders hold bargaining advantages, more women holding executive office may indeed lead to peace, but not because women are less willing to fight than men. In fact, our results suggest women may actually be more willing to fight. The peace-inducing effects of female attainment of high office, rather, stem from the fact that women make more credible threats, and can communicate their intentions and resolve more effectively. In sum, our empirical results may help unify extant theoreticalFootnote 100 and empirical critiquesFootnote 101 of the women-as-peacemakers view that Fukuyama and Pinker, among others, espouse.Footnote 102 In this way, our theoretical framework and results can account for the seemingly disparate facts that female leadership is associated with peace,Footnote 103 and that women are as or more likely than men to initiate conflicts.Footnote 104

Our results also highlight a number of promising avenues for future research. First, new work suggests that apart from inconsistency and belligerence costs, incompetency costs also weigh in the public's mind during international crises.Footnote 105 These are costs that leaders pay for failing to achieve their audiences’ desired outcomes. While beyond the scope of this project, it would be interesting to extend our argument about gender stereotypes to an analysis of incompetency costs to determine whether women are also held to higher standards than men in evaluations of policy success, as some scholars imply.Footnote 106 Second, more research is needed to unpack the diverse ways gender stereotypes matter, ranging from chivalry reactions in cooperative scenariosFootnote 107 to the costs we identify in interstate crises. Third, our findings speak to the need for more research on whether gender stereotypes operate primarily as first- or second-order beliefs among members of the public. Fourth, and relatedly, what are leaders’ first- and second-order beliefs about how gender stereotypes affect rival leaders’ credibility? Future research could fruitfully tackle this question with elite surveys.Footnote 108 Finally, our results raise questions about how other pervasive biases, such as racial stereotypes, affect international policymaking. Greater appreciation for the role of gender and other stereotypes in international relations can help scholars understand the likely implications of greater diversity in the world's executive offices.

Data Availability Statement

Replication files for this research note may be found at <https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/LRP3SZ>.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material for this research note is available at <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818320000223>.

Funding

Generous support for this research was provided by the Christopher H. Browne Center for International Politics at the University of Pennsylvania and Time-Sharing Experiments for the Social Sciences (TESS). Some of the data were collected by Time-Sharing Experiments for the Social Sciences, NSF Grant 0818839, Jeremy Freese and James Druckman, principal investigators. This research was approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board (IRB Protocol #832589).

Acknowledgments

This is one of several joint articles by the authors; the ordering of names reflects a principle of rotation with equal authorship implied. We thank Diana Mutz, Shira Pindyck, Dawn Teele, Ryan Brutger, Jonathan Chu, James Druckman, Jeremy Freese, Michael Horowitz, Nicholas Sambanis, Dustin Tingley, Alex Weisiger, participants at the 2019 Harvard Experimental Political Science Conference, two anonymous TESS reviewers, two anonymous International Organization reviewers, and the editors and staff of International Organization for helpful comments and advice.