Songs by the Rolling Stones are used in the soundtracks of so many contemporary film and television productions that any attempt to count them would be a fool’s errand. The group’s role as the stars or principal subjects of documentary films concerned with popular music and culture is far easier to chronicle, however, but no less instructive in terms of demonstrating the central influence of the Stones within the world of motion pictures. It is not an exaggeration to suggest the Rolling Stones represent the most documented musical group in the history of cinema. It is explained, in part, as the result of their unrivalled longevity, but equally for the timing of their emergence on the scene and the ease with which they both invited and adapted to the presence of cameras in their professional lives. Looking at Dominique Tarlé’s still-photography (1971) captured during the band’s exile in France and the recording of Exile on Main Street at Villa Nellcôte, alongside home footage from the period (now available within the Stones in Exile DVD, Stephen Kijak, USA, 2010), it becomes clear that the band was surrounded by motion picture cameras – those of professionals as well as their own – to an ubiquitous degree. Over the course of their career, the Rolling Stones embraced documentary film-making and the opportunities made available through increasingly sophisticated, progressively mobile, synchronized sound film technology in a manner rivalled by few, if any, of their contemporaries. Early on, they understood the power of the moving image and the degree to which it could both secure and perpetuate the mythology of the band, collaborating with a range of innovative filmmakers and artists whose approaches would facilitate such a project of self-creation. However, after public controversies, personal turmoil, and diminishing financial returns, the Rolling Stones would begin to exert an increasing amount of control over their cinematic representation, which results in work through the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s that rarely, if ever, demonstrates the innovation and intimacy for which the first decade of their documentary appearances is so celebrated.1

If the theatrical première of the concert revue T.A.M.I. Show (Steve Binder, USA, 1964) marks the emergence of the rockumentary genre as we know it today – that is, those film and television projects recognized for their representations of live musical events, culturally important historic rock music gatherings, and, occasionally, behind-the-scenes tell-alls – we observed the fiftieth anniversary of the genre soon after the Stones celebrated their golden anniversary among rock’s most cherished icons. And in that foundational film, revered by fans for career-defining performances by James Brown and the Supremes, we find Mick Jagger and Keith Richards participating in the birth of one of the documentary genre’s most commercially viable and aesthetically rich categories. The history of the Rolling Stones in documentary film is, essentially, the history of the popular music documentary, and more specifically, the rockumentary genre. Several portraits of the Stones populate the first wave of rockumentaries, films that ultimately define the genre, including the aforementioned T.A.M.I. Show, Charlie Is My Darling (Peter Whitehead, UK, 1966), Sympathy for the Devil (Jean-Luc Godard, FRA, 1968), and Gimme Shelter (Albert Maysles, David Maysles, Charlotte Zwerin, USA, 1970). A survey of several key films spanning the first decade of film-making focused on the group (1964–74) illustrates the pivotal role non-fiction film played in their professional lives and in establishing their celebrity; across this body of work, the main currents and trends comprising the rockumentary genre are represented: the concert film, the artist biography, the festival film, and the “making of” or tour film.2 The visual representation of the Stones in motion pictures is a central plank in establishing the iconography of rock performance (both onstage and off), and the structure and style of these films becomes a standard upon which other filmmakers and artists model their work. The diversity of approaches to documenting the creative work of the band and their persona is matched only by the diversity of ways in which they are revealed – or choose to reveal themselves – to the camera and filmmakers. The Rolling Stones, on film, are both canonized and contribute to the canonization of a documentary genre and a visual grammar of rock.

Roll Camera

Here they are, those five fellows from England, the Rolling Stones!

If the birth of rockumentary is foreshadowed by the 1960 concert film Jazz on a Summer’s Day (Bert Stern, USA), the multi-artist revue film T.A.M.I. Show firmly establishes the basic features of the fledgling genre. The film is a record of the so-called British Invasion of American popular music as it was taking place (despite the absence of the Beatles, who had made their own big screen début several months earlier with A Hard Day’s Night; “They wanted too damn much money,” executive producer William Sargent told the New York Times on October 15, 1964). The Rolling Stones headline a bill alongside Gerry and the Pacemakers, Billy J. Kramer & the Dakotas, and established black crossover acts like Chuck Berry, the Supremes, Marvin Gaye, and James Brown. Originally conceived as the first of an annual film event featuring rock and roll artists, in support of music scholarships for teenagers, T.A.M.I. Show is a valuable document of the diversity of teen-oriented popular music at the time and a vivid illustration of the impact of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 – only months old at the time of the event – with its integrated cast of musicians and dancers as well as an integrated audience. Film director Binder credits producer and band leader Jack Nitzsche (who later appeared on several Stones albums as musician and arranger) for selecting the majority of the acts, most of whom went on to significant careers in pop music. Formally, T.A.M.I. Show is built upon the conventions of television, specifically the well-established variety show format (in many ways the film is a theatrically released compendium of awards show-style musical performances still common today) and broadcast television contemporaries Shindig! (ABC, 1964–66) and the Binder-directed Hullabaloo (NBC, 1965–66). The film is composed primarily of three- or four-song medleys from each artist, with edits limited to the transitions between acts, and introductions by teen pin-ups Jan & Dean serving as bumpers. Most artists appear alone on stage and receive off-screen musical support from select members of the Wrecking Crew – the famed LA session musicians, including Hal Blaine (drums), Tommy Tedesco (guitar), and Lyle Ritz (bass), whose work appears on a dizzying assortment of classic recordings ranging from Frank Sinatra and Herb Alpert to the Beach Boys and Simon & Garfunkel. The Stones are among a small number of artists who perform without accompaniment by the Wrecking Crew, and their segment features more camera movement, crowd-reaction shots, and close-ups than any other in the film. It is important to recall the threat to common decency and conservative morality rock and roll music, and the Rolling Stones in particular, was perceived to present mainstream Western society upon its arrival in the mid-twentieth century. As such, we cannot take for granted the impact of even the most benign performative gestures exhibited by the band. Describing the potency and the rebellious qualities of Jagger’s performance style from the outset, David James writes,

Both spontaneous and calculated, the sexual instability of his body was matched by the dualities in his voice, the combination of the vowels and phrasing learned from blues records with the Cockney affectations becoming one of rock ’n’ roll’s seminal amalgamations of conflicting racial, national, and sexual characteristics, all paraded on a similarly ersatz working-class attitudinizing.3

The physicality of Jagger’s performance and the slow build from his reserved vocal delivery and stationary position during the opener “Around and Around,” to the prowling, crowd-provoking dynamism exhibited during the set’s penultimate song, “I’m Alright,” proves foundational to subsequent cinematic representations of the Stones as performers and central to fan expectations. In this first of many documentary portraits of the group as live performers, the sheer force of Jagger’s musical energy and endless charisma suggests seeing the Rolling Stones is perhaps just as important as hearing them, and that their persona as a group is not discernible solely by way of their sonic identity.

Collaborations with the Avant-Garde

[Charlie Is My Darling] brings out a pathetic sadness about the teenage idolatry about pop singers, and the effect it has on the Stones who emerge from the film as basically very talented musicians who would be completely destroyed once they lost their own individual personalities.

The Rolling Stones’ first starring role in a documentary film exemplifies their relationship with the emergent British arts scene of the 1960s. Moreover, it highlights Jagger’s early investment in cultivating an image of himself and the band that exists outside the perceived triviality of pop music. Nine months after the release of T.A.M.I. Show arrives a tour movie following the band about to explode onto the world stage. Peter Whitehead, trained in film-making during his time at the Slade School of Fine Art in London, was commissioned by the Stones’ then-manager Andrew Loog Oldham to produce a documentary of the band’s September 1965 tour of Ireland, with the hope that it would attract financiers for a feature-length vehicle similar to that of Hard Day’s Night (Richard Lester, UK, 1964) released a year earlier.4 The result, Charlie Is My Darling, is a fifty-minute blend of life on the road, backstage moments, and public appearances alongside several brief musical sequences. Structurally, the film offers viewers no sense at all of the itinerary of the tour, the venues, the scale of the performances, or the audiences themselves; the material is only truly meaningful when refracted through the lens of the Stones’ long history. Unreleased until 2012 as a result of litigation between the band and their former manager (which is to say nothing of the many different unlicensed music sources that appear on the soundtrack, all serving as a major impediment to any official release), the film was nonetheless widely available on bootleg videocassette for many years and would screen at retrospectives of Whitehead’s work when the director was in attendance.

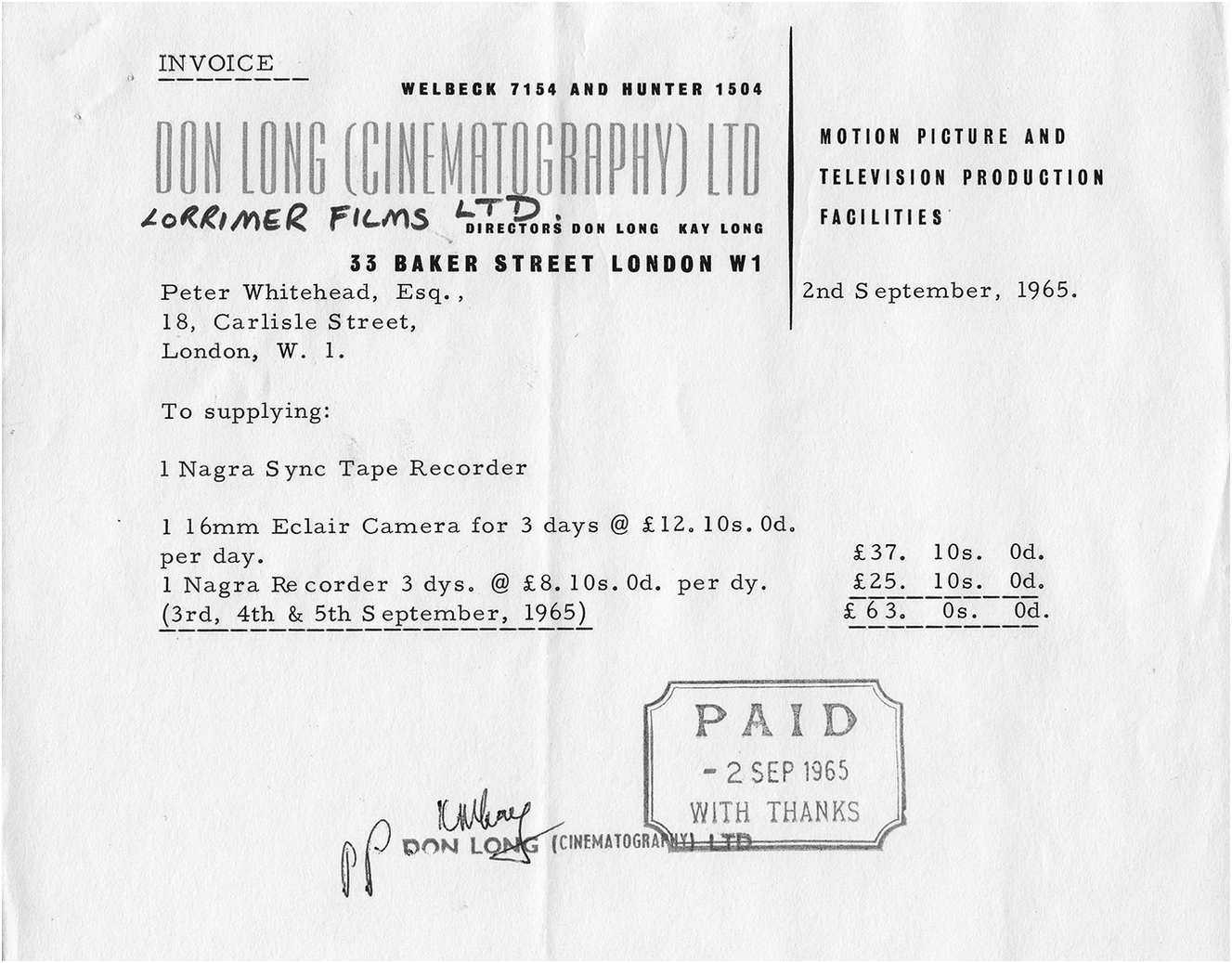

Charlie Is My Darling serves as a counterbalance to the overwhelming number of rockumentaries that adopt a strictly observational mode of address, wherein filmmakers serve as witness to events for the absent viewing audience, oftentimes crafting the illusion of unmediated access to those events.5 Adopting the mobile 16 mm motion picture camera and then-new wireless synchronized sound recorder favored by so many of his contemporaries (a 16 mm Éclair NPR camera matched with a Kudelski Nagra III recorder; see Figure 9.1), Whitehead is an active participant in the events he photographs. At times, his voice is heard off-screen asking questions of those on-screen and directing the action. Recurring images of youthful fans and synch-sound interviews with members of the public feature Whitehead’s insistent queries, “What do you like about them? Why? What is it? When did you first grow your hair long?” Meanwhile, several extended exchanges between Whitehead and band members directly address the hysteria surrounding the group and the dilemma facing young musicians recognized more for their behavior than their music. Guitarist Brian Jones explains he is satisfied with the success of the Stones but creatively unfulfilled by life as a pop star; at Whitehead’s prompting he discusses an unrealized film project based on the principles of Surrealism. Drummer Charlie Watts, after whom the film is named, feels humbled by his experience in the Rolling Stones and plainly states he is not yet an artist, simply a musician in a successful band. These weighty moments clash with scenes of bored band members prepping for the stage and jockeying for a turn in front of the mirror – all appear to be blotting cold sores and other blemishes with cover-up, an image later played for laughs in the classic music mockumentary, This Is Spinal Tap (Rob Reiner, USA, 1986) – but all leave viewers with the same impression that the most powerful acts of revelation in the film are those that suggest the Stones have let down their guard.

Figure 9.1 Invoice for the rental of camera and recorder used by Whitehead for the filming of Charlie Is My Darling.

Stylistically, there is little of note apart from a brief step-printed sequence focused on Jagger’s acrobatic stage persona. “All of it’s acting,” Jagger explains in a voice-over, “But there’s a difference between acting and not enjoying it, and just doing what you want to do. It’s like getting into a part.” Images of the band travelling in cars, waiting in airport lounges, and racing through crowded train stations as enthusiastic fans clutch and grab the Stones seem to fascinate Whitehead more than the music and occupy a large portion of the film’s running time. As Coelho has written,

Blurring the distinction between the “center” and the “periphery” of his subject by training his camera on just about everything – entrances and exits of the band, policemen, bystanders, street life, curious onlookers, rioters, impromptu backstage music – Whitehead prioritizes the mundane, improvised, sometimes vapid offstage culture, as opposed to the frenzy of the more scripted live show.6

There is the customary backstage-to-front-of-house tracking shot now so common to the genre, a feature Charlie Is My Darling shares with the more widely copied shot from D. A. Pennebaker’s Dylan film, Don’t Look Back (D. A. Pennebaker, USA, 1965) produced in the same year. The soundtrack is a mélange of clips from Stones recordings with preference given to “Play With Fire” (a track recorded and released shortly after the conclusion of the Irish tour), instrumental versions of Stones songs recorded by other acts, and candid audio interviews with band members in a manner quite similar to The Beatles at Shea Stadium (ABC Television, USA, 1965). There is not, however, a single musical performance sequence featuring synchronized sound apart from brief moments of the group warming up and jamming backstage. There is an extended performance segment in the middle of the film featuring a number of songs, but the soundtrack appears to be a separate audio recording of the event (poorly) post-synchronized with the image track. The sequence concludes with a stage invasion that completely disrupts the performance and ends the show; the band makes a hasty retreat from the venue with the assistance of police officers as the crowd of screaming girls chants, “We want the Stones! We want the Stones!” It is an eerie portent of the events captured in Gimme Shelter, which serves to document the end of the 1960s idyllic dream of free love and non-violence.

According to Whitehead, Charlie Is My Darling received a Gold Medal at the 1966 Mannheim Film Festival (records suggest it was, in fact, Whitehead’s Wholly Communion that won the prize); it was screened in a truncated version on German television, while the BBC and Granada refused to put it on the air. Joseph von Sternberg, acclaimed filmmaker and director of the festival that year, reportedly said of the film, “When all the other films at this festival are long forgotten, this film will still be watched – as a unique document of its times.”7 Von Sternberg’s prediction, however, would not come to pass for many years as a result of prolonged legal battles and business maneuvering between Whitehead, manager Oldham, and ultimately Jagger himself that kept the film from public exhibition as ownership and commercial rights remained in dispute.8 The film would only become widely available in 2012 when Allen Klein’s ABKCO – owner of most audiovisual materials dating to that period of the band’s history – released a version containing new material (re-edited by Nathan Punwar) dubbed, Charlie Is My Darling – Ireland 1965. The highlight of the film is undoubtedly a step-printed sequence featuring stage invasions at Rolling Stones concerts set to the slow tempo of the Jagger/Richards ballad, “Lady Jane,” from Aftermath (1966). Whitehead’s marriage of the glacially paced acts of violence to the gentle instrumentation of the song – a not-so-subtle commentary on youth culture and fan worship at a transformative moment in popular music history – is ahead of its time in anticipating a recurring trope of contemporary music video, namely an investment in abstraction and expressionistic devices at the expense of conventional portraiture of the performance.9

Oldham, Jagger, and the Stones continued their flirtation with cinema’s avant-garde with the film-making partnerships that followed their work with Whitehead. French filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard’s foray into the emerging rockumentary genre is in many ways influenced by Pennebaker and occurs during a period of collaboration between the French New Wave auteur and the American on another project – the alternately abandoned, disowned, and adopted One P.M. (1972). Godard’s curious portrait of the Rolling Stones, One Plus One (later, Sympathy for the Devil [FRA, 1968]), features camerawork and backstage footage that is not dissimilar from Pennebaker’s largely observational work, but Godard’s methods and philosophy are something entirely different. Focused entirely (musically, that is) on the recording of what became the title track of the film, Godard alternately builds upon and undermines rock’s political potential with a series of digressions that take the viewer far from the recording studio and instead to fictional sequences featuring Black Panthers stockpiling arms for an impending revolution, feminists, and Marxist revolutionaries spouting political slogans, prose from romantic novellas, and long passages from central texts by LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka) and Eldridge Cleaver. It is fair to say that no other example of this bricolage exists in rockumentary history, though Godard’s radical influence is felt in arts documentaries and biographies of avant-garde musicians, all of which share a kinship with the more commercially successful documentary genre. It is a testament to Godard’s talents (and patience as a filmmaker) that the in-studio footage of the Stones remains one of the most comprehensive and illuminating documents of rock songwriting and record production ever captured on film, but it is in no way conventional. Shaun Inouye writes,

the Stones appear more like actors on-set than documentary subjects on-location, ambling through rehearsed material under stage-lights and boom-mikes while Godard’s camera, casting bouncing shadows across the room, ostensibly films its own participation in the recording process. With each tracking pass, Godard seems to suggest that the reality “captured” by the documentarian is no more real than the reality fabricated by a movie studio, and its “real-life” subjects, no more authentic than the actors’ best roles.10

Godard’s in-studio rehearsal footage is beautifully composed and photographed by cinematographer Tony Richmond, who made vital contributions to the rockumentary genre in films such as Let It Be (Michael Lindsay-Hogg, UK, 1970) and The Kids Are Alright (Jeff Stein, USA, 1979) over a career of forty-five years and counting. Completed two years before its 1970 North American release, it is a complex film befitting Godard’s temperament and the Stones’ desire to be validated artistically, and it challenges the conventional representation of musical performance in non-fiction film. As a portrait of the Rolling Stones, however, it remains a difficult film with which to engage and is no doubt the most perplexing entry in the group’s filmography, its importance in chronicling the compositional process of “Sympathy for the Devil” notwithstanding.

Gimme Shelter

There is quite a lot of music and performing in Gimme Shelter, some of it beautifully recorded, but it is not a concert film, like Woodstock. It is more like an end-of-the-world film, and I found it very depressing.

With the December 1970 release of Gimme Shelter arriving as it did eight months after the blockbuster success of Woodstock (Michael Wadleigh, USA, 1970) and only weeks after the première of Elvis: That’s the Way It Is (Denis Saunders, USA, 1970), the box office future of the rockumentary genre seemed assured (despite the unexpected failure of the Beatles’ Let It Be), with the Stones playing a major recurring role in its evolution and emergence. Recognized as one of the great achievements of the rockumentary genre and American documentary history as a whole – in large part the result of its serendipitous murder sub-plot and Altamont’s symbolic standing as the definitive end of the 1960s peace-and-love movement – Gimme Shelter is a structurally complex film that ultimately transcends the genre with its appeal to a general audience. For better or worse, the bedlam and the beauty captured by pioneering American documentarians Albert and David Maysles during the 1969 American tour rank among the most iconic in the band’s history and trap in amber the image of a band at once reckless, composed, and creatively ahead of their peers.

Mick Jagger and new manager Allen Klein discussed the possibility of contracting D. A. Pennebaker to produce a film about the 1969 Stones tour prompted by the knowledge that the Woodstock festival would be filmed and released by a major Hollywood studio; it is said Pennebaker declined to participate because of concerns about the scene developing around the group.11 Ultimately, filmmaker Haskell Wexler (who also passed on the project after a meeting with Jagger) recommended the Maysles brothers and their partner, Charlotte Zwerin, on the basis of the trio’s central place in the American New Documentary movement and their groundbreaking approach to portraiture, including With Love from Truman (1966) and Salesman (1968). Filmed over the course of several weeks in November and December 1969, Gimme Shelter features four distinct areas of action: on-stage and on-the-road sequences shot during the Stones’ US tour in advance of the Altamont Speedway Free Festival (which took place on December 6, 1969 – the film premièred on the first anniversary of the event); scenes of the group recording tracks at Muscle Shoals Sound Studio in Alabama for their forthcoming Sticky Fingers LP (1971); observational footage of the band’s managers, lawyers, and allies making arrangements for the one-day festival event; and performances from the Stones, first at Madison Square Garden, and subsequently alongside other artists at the Altamont concert (shot with the assistance of a team of cinematographers including local film studies graduates George Lucas and Walter Murch). Framing all of these elements are scenes of the band reviewing the Maysles’ rough-cut of the film and commenting upon the unfortunate events of Altamont. It is not a comprehensive portrait of the concert itself: performances by Santana and Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young are not featured (the musicians do not appear in the film at all), while sets by Jefferson Airplane and the Flying Burrito Brothers are represented by single songs. Continuing a trend established with Woodstock, the filmmakers collaborated with an outside sound engineer for the recording of the concert audio tracks. Glyn Johns’ (Bob Dylan, the Beatles, the Who) multi-channel audio recordings of the Madison Square Garden performances of November 27–28, 1969 were edited and mixed for use in Gimme Shelter before serving as the source for the band’s seminal live LP, Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out! The Rolling Stones in Concert (1970); the album was released in advance of Gimme Shelter’s theatrical première.

The death of eighteen-year-old Meredith Hunter at the hands of the Hell’s Angels during the Stones’ headlining set becomes the organizing element that structures the entire film. The death also brings to the fore issues of collaboration and responsibility that run throughout the rockumentary genre (and documentary in general) by forcing viewers to question the role played by filmmaker and subject in the horrible attack. Pauline Kael famously described the film as akin to “reviewing the footage of President Kennedy’s assassination or Lee Harvey Oswald’s murder,” and laid the blame at the feet of the filmmakers themselves in a controversial piece published in the New Yorker (December 19, 1970). Popular music scholar Sheila Whiteley offers a more nuanced analysis of the event:

Whilst the arrogance and brutality inherent in [the Stones’] songs suggest a certain correlation with the events at Altamont it would, nevertheless, seem somewhat simplistic to posit an unproblematic stimulus/response interpretation. Jagger might introduce himself as Lucifer, as “the Midnight Rambler,” but overall it is suggested that his role was more that of the symbolic anarchist, expressing the right to personal freedom, the freedom to experience. As such he provides an insight into degeneracy rather than an incitement to a pseudo-tribal response.12

As a result of the festival’s disorganization and the fatal final act, the Altamont Speedway Free Festival and its filmed record are considered by many to be the symbolic conclusion to the 1960s and the shadowy counterbalance to the idealism of Woodstock (and its film). Robert Christgau argued in 1972 that “writers focus on Altamont not because it brought on the end of an era but because it provided such a complex metaphor for the way an era ended.”13 The spirit of collaboration and the sense of community that has come to define Woodstock and the era as a whole is overturned by Altamont’s entanglement of complex business concerns and the Stones’ cultivated egotism, revealing fissures in a youth culture so often identified as unified and single-minded. That the event concludes with a senseless murder only seems to confirm the film’s status as an eschatological statement of 1960s utopian youth culture.

Gimme Shelter is not the first rockumentary to focus on the off-stage personalities of the performers – Lonely Boy (Wolf Koenig and Roman Kroitor, CAN, 1962), the Beatles documentaries, and Don’t Look Back were pioneers in that regard – nor is it unique in documenting the act of making records. But unlike earlier rockumentaries and the current concert film genre, Gimme Shelter foregrounds the role cinema plays in the act of recollection; the film is a meditation on the act of documentation and becomes something more than an exercise in representing a singular musical event or experience. Moreover, it accents the role of the filmmakers as complicit in the process of mythologizing the event. In his 1970 review of the film, Vincent Canby wrote:

As was the movie about the Woodstock festival, Gimme Shelter was a part of the event it recorded, being, in fact, a commissioned movie, the proceeds from which are to help the Stones pay the costs of the free concert (although they grossed a reported $1.5-million from the other, nonfree [sic] concerts on their tour). Thus, the movie that examines the Stones, and the Altamont manifestation, with such a cold eye, seems somehow to be examining itself.

The film presents viewers with a flow of performances, conversations, arguments, and incidents from before, during, and after the concert that come together as a recollection of, and conversation about, Altamont, leaving a foreboding sense that the Rolling Stones are particularly ill suited to managing and containing the aggression and violence demonstrated at the event (a feeling underscored by their ill-advised decision to employ the Hell’s Angels as protectors); the Maysles and Zwerin foreshadow these events by employing audio recordings of callers to a KSAN radio show after the festival concludes as an expository device throughout the film. Through extensive scenes involving the business behind the production of the event, the presence of band members during the editing of the film, and the incorporation of the KSAN broadcasts, the Maysles and Zwerin contextualize the events of Altamont and encourage interpretation and critique. It is a rare example of a rockumentary film engaging in the ethical debates concerning the relationship between filmmaker and subject, which were crucial to the development of the New Documentary of the 1960s and 1970s.

Gimme Shelter regularly employs a reflexive mode of address during those scenes involving the band screening rushes (daily footage) of the film-in-progress and footage of Hunter, prompting the band members and film audience alike to question the filmmakers’ role in creating the experience; it is a representational strategy not yet explored within rockumentaries at this point in their evolution but employed here with striking effect as the filmmakers highlight the form of the text itself.14 Much has been written about the passive, almost dismissive response of Jagger to the violent footage captured by the Maysles (and Kael was particularly damning in her evaluation of Jagger’s behavior), but less has been said about Watts, who serves as the Maysles’ true object of interest during these passages precisely for his humane response to the events. Watts views the footage and tries to understand how things arrived at such a point, remarking, “Oh dear, what a shame.” Whether or not the Maysles and Zwerin consciously construct Watts as sympathetic figure and a surrogate for the audience is debatable, but there is no denying his appearances convey none of the antagonism demonstrated by Jagger and his dismissive responses to the material he screens in the company of the Maysles (including his evaluation of Tina Turner’s searing performance as an opening act for the Madison Square Garden shows: “It’s nice to have a chick occasionally.”). One might say Watts’ naturalistic behavior casts unfavorable light on Jagger’s inauthentic performance in the company of the filmmakers; his off-stage persona is no less constructed than the one he adopts during live performances.

Gimme Shelter refines many of the basic shooting strategies introduced by earlier works of this classical period of the rockumentary genre. While there are fleeting lyrical elements on display during musical sequences – the slow-motion and superimposition employed during the “Love in Vain” performance, which recalls the “Lady Jane” sequence from Tonite Let’s All Make Love in London – on-stage performances are overwhelmingly shot in a journalistic style. It is worth asking the question whether or not these impressionistic elements were prompted by the likelihood of poor synchronization if the filmmakers proceeded with their decision to include “Love in Vain” in the finished film; the audio recording of the song available on Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out! – and presumably the one available to the filmmakers during post-production – may have come from a performance in Baltimore preceding the New York City concerts. The cameras are positioned at the front and side of the stage and focus on Jagger at the expense of the rest of the band (particularly during the Madison Square Garden performances), and there is an assuredness and clarity to the framing and pictorial quality that dimly sets the film apart from earlier work in the genre, including that of Maysles. What is noteworthy is a higher rate of cutting adopted by the Maysles and Zwerin during performance sequences relative to earlier examples from the genre. The reduction in the average shot length imbues these sections of the film with a particular rhythmic quality, and reflects the dynamism of Jagger’s expressive performance style in a manner that is clearly differentiated from non-musical sequences of observation, interactivity, and reflexivity elsewhere in the film. Also of interest is the way in which the filmmakers accent moments away from the action that nonetheless communicate the decadence and mystique of life on the road and life on stage. The film is peppered with sequences concerned with the mundane moments of a rock star’s routine, but these passages are invigorated by Albert Maysles’ wandering eye and his trademark attention to the quirky details of his subjects. His fascination with Jagger’s flowing red scarf (both backstage and caught in the car door of his chauffeured ride) and Richards’ scuffed and scarred snakeskin boots in Muscle Shoals (while reclining in the studio listening to an early playback of “Wild Horses”) comprise the two most memorable images among Maysles’ inventory of rock iconography, particularly in that they are captured far from the action. Such moments become central to conveying the sense of access that is central to later works within the tour film and “the-making-of” categories, as documentary filmmakers work to carve out the off-stage personalities of rock performers from their outsized celebrity and on-stage personae.

Moving Forward, Moving Backwards

“Never mind vérité,” [Richards] reportedly replied, “I want poetry.”

Two additional feature-length films starring the Rolling Stones appeared in the years immediately following Gimme Shelter and did little to shed the aura of danger surrounding the band. Both films were made during the American tour in support of Exile on Main Street (1972) under the guise of a single production. In the end, two very different films resulted, with the first focused entirely on backstage affairs, reinforcing the veneer of irresponsibility that followed the band after the events of Altamont. Cocksucker Blues (Robert Frank, USA, 1972) is a portrait of excess and debauchery so raw and unflattering that the band immediately filed an injunction against its release, and came to the unheard-of agreement that it could only be screened on a limited basis within the context of a retrospective of the artist’s work and only if the filmmaker was in attendance at the screening.15 The artist in question, celebrated postwar photographer Robert Frank, was approached by Jagger to create the sleeve for Exile on Main Street. Instead, Frank counter-proposed that he design the sleeve as part of a larger project of documentation that would highlight his adoption of 8 mm motion picture photography. Assisted by his friend and protégé, Danny Seymour, Frank would enjoy access to the band and their entourage to a degree previously unheard of in the world of popular music. Frank’s standing in the American art world as a photographer and experimental filmmaker has resulted in the banned film appearing in special engagements at major institutions, including the Whitney Museum of American Art (where it publicly premièred in 1980), Tate Modern (2004), Metropolitan Museum of Art (2009), Museum of Modern Art (2013), and in a touring retrospective in 2016, but it is otherwise only available in various bootleg formats.16

Less interested in musical performance than in the seamy side of the rock lifestyle with its drugs, adoring fans, and celebrity hangers-on (including Andy Warhol, Truman Capote, and Dick Cavett), together with the monotony that quickly comes to define life on the road, Frank leverages the mobility and discrete nature of the Super 8 mm and 16 mm motion picture film formats not only to capture images off the cuff and when the band is most vulnerable, but to hastily conceive and direct sequences that will capture the attention of audiences. How else can we explain images of Keith Richards strung out on heroin, the scene purportedly depicting roadies sexually assaulting groupies on the Stones’ private jet, or Jagger with his hand down the front of his jeans masturbating for the camera? Frank structures footage of tour rehearsals, listening sessions, travel time, backstage prep, and recreation in a stream of consciousness flow with no clear chronology or context for the images. A title card introduces the content of the film as “fictitious” in what can only be presumed to be a legal maneuver to protect the band. Cocksucker Blues represents a level of access never seen before or since, and contributes to the development of the tour film current established by Don’t Look Back and Elvis on Tour, wherein the personalities and lifestyles of the musicians are framed by their backstage routines and lives away from the spotlight, often at the expense of performance footage. Ultimately, the Stones’ sensitivity to their portrayal in this material – so soon after their featured role in Gimme Shelter – deepened their resolve to control its availability, a position further reflected in their selective use of Frank’s material in the contemporary, Stones-produced Stones in Exile, chronicling the making of the album. Cocksucker Blues remains unavailable outside of the original screening agreement struck with Frank, and it isn’t beyond the realm of possibility that whatever quality prints of the film still exist will go to the grave with the director unless the Stones acknowledge the historical significance of the film and accept that it plays a major role both in the evolution of the rockumentary genre and their legacy.

Ladies and Gentlemen: The Rolling Stones, the second film produced during the 1972 US tour, is a relatively bland corrective to the portrayal of excess, abuse, and disaster that follows the band throughout Gimme Shelter and Cocksucker Blues (while nonetheless demonstrating the negative impact the band’s infamous alcohol and drug use had upon their stage performances at this pivotal point in their career). Shot on 16 mm by cinematographers-for-hire Steve Gebhardt and Bob Fries over four nights in Texas, then optically processed to 35 mm for theatrical distribution, stylistically – with its static camera positions and conventional framing and editing – Ladies and Gentlemen … represents a step backward from the sophistication of Gimme Shelter. Many Stones fans regard this period as a high point in the band’s history, yet the absence of any framing material for the performances captured here leaves the film floating free of any historical context with which a casual viewer could properly place the performance within the band’s career.

Frank and his close friend and collaborator Danny Seymour originally intended to focus on the 1972 North America tour in its entirety, but the backstage footage captured by the pair, ultimately crafted into Cocksucker Blues, was deemed inflammatory and uncommercial, and was cast aside. It was at this point that director Rollin Binzer, a highly respected figure in the world of advertising, was brought in to shape Gebhardt and Fries’ concert footage into a feature-length film and market it as a major event. In lieu of a conventional theatrical release, the band opted to “four-wall” the film and present it as a special engagement through 1974 with a multitude of city-by-city promotional stunts, showing it using a customized projector and screen, branded Stones stage curtain, and – most importantly – state-of-the-art quadraphonic sound system.17 Fries and Keith Richards worked on post-production audio for four months at both Twickenham Studios in England and the Record Plant in Los Angeles in an effort to perfect the quadraphonic soundtrack, which was marketed as the first of its kind. In this regard, the Stones consciously enhanced the soundtrack of the film as the spectacular feature of the presentation, and did so with a commitment to leading-edge sound reproduction technology that foreshadows the theatrical concert film of the 1980s and 1990s. While individually the limited-engagement screenings were successful, they didn’t occur in any significant numbers and never outside of major North American centers. Like several other Stones films before it, Ladies and Gentlemen … was officially unavailable for many years after its original release and suffused with some mystique by fans of the band and film collectors; in early 2010 it was briefly rereleased to theatres and finally made available on home video after the band successfully regained various international rights to the film. Importantly, the project as a whole provided the band with a degree of control over the presentation of the event and their image that they had not previously enjoyed, and this set a precedent for the Stones’ participation in future documentary productions.

***

The band, in short, has gone from a threatening R-rated attraction to something in the nature of a PG-rated one, which is not simply that the Stones have gone soft; it’s simply a different approach.18

In the 1970s, the floodgates for the feature-length theatrical rockumentary opened and a torrent of work appeared in the first half of the decade, establishing the genre as a serious box office and record-selling concern. The public’s imagination was captured with chronicles of large-scale cultural events such as Woodstock and Isle of Wight, spectacles based upon elaborately produced stadium tours, and portraits of larger-than-life rock celebrity, all at a time when both record sales and the overall growth of the North American entertainment industries were expanding exponentially. The Rolling Stones, with their featured performance in T.A.M.I. Show, the intimate portraiture of Charlie Is My Darling, the postmodern turn of Sympathy for the Devil, the dark reckoning of Gimme Shelter, and the divergent documentation of the 1972 North American tour as presented in Cocksucker Blues and Ladies and Gentlemen: The Rolling Stones, were a central force in the evolution of this documentary category and used these films to craft and reinforce their public image. Not even the Beatles, featured as they were in a number of key early popular music films and documentaries, kept pace with the Stones on-screen during their brief tenure before their dissolution in the early 1970s. Perhaps both the Stones’ acceptance of, and regular participation in, non-fictional projects was a tactical decision that allowed them to cultivate and more deeply entrench the bad-boy image that served as one of the clearest points of differentiation between themselves and the Beatles within the popular imaginary. Whereas the Beatles were controlling and buttoned-up, removing themselves from both the rigors of touring and the scrutiny of life in the public eye, the Stones toured relentlessly and invited filmmakers to document both their performances and their creative lives offstage. It is then curious that at precisely this moment in the genre’s development, in the wake of Ladies and Gentlemen … and facing a series of personal and professional obstacles, the group would withdraw from cinema’s spotlight. The band would not participate in another theatrical documentary project for nearly a decade, finally returning to the screen with the feature-length concert film Let’s Spend the Night Together (Hal Ashby, USA, 1983). The project was met with mixed reactions, celebrated by some for Ashby’s ability to capture faithfully the pastel-soaked gigantism of the tour’s stage design and enormity of the stadium crowds that the band now commanded (“It’s just a concert,” wrote Janet Maslin for the New York Times, “a beautifully crafted record of the Stones’ performing style at this stage of their career, and Mr. Ashby hasn’t tried to make it anything more.”). It was attacked by others for its complete lack of creativity and several poor editorial decisions; Roger Ebert in the Chicago Sun-Times admonished the band and Ashby for including images of famine victims and decapitated political prisoners in a regrettable montage sequence set to “Time Is on My Side,” images that the band excised from the film upon its release on home video in 2010.

Currently, the Rolling Stones remain ever present in popular music documentaries and committed to non-fictional portraits of their creative process and live performances as key to their artistic personae. With almost each album release, a making-of documentary is included in the album package, while a made-for-home video tour documentary or concert film often follows in the album’s promotional cycle. As Coelho has written, it is the continuation of a practice adopted in the wake of Cocksucker Blues that finds “the Stones [taking] increasing control of their concert footage as a way to rectify, reify, and even deify their historical position within popular music.”19 Occasionally, the investment is made in a production intended for theatrical release or pay-television. Shine A Light (Martin Scorsese, USA, 2008), shot at New York City’s Beacon Theatre during the course of the 2006 A Bigger Bang tour in observance of the band’s 45th anniversary and released theatrically in standard and IMAX formats, was celebrated by fans and critics alike and prompted numerous articles on the resurgent popularity of “rock docs.” It was a box office success, grossing $15.8 million worldwide, ranking it among the highest-grossing documentary releases of 2008 (and for a time in the top ten highest-grossing concert documentaries ever), and the most successful Stones film in their history.20 Nonetheless, for some it was a timid portrait of a rock act in decline. More recently, the fiftieth-anniversary retrospective project for HBO, Crossfire Hurricane (Brett Morgen, USA, 2012), commemorated the first twenty years of their career and did so by accenting the central place the Rolling Stones occupy in the rockumentary canon, explicitly privileging the cinematic record to give visual form to the audio interviews recorded exclusively for the project. The history of the Rolling Stones on film has become the history of the band itself. And so we might playfully ask, were the Rolling Stones the authors of these filmic images that now stand as iconic of the group and representative of rock culture at large, or did the films create the Stones and cement our impression of the group as popular music’s most authentic purveyors of the ideals and rebellious nature of rock and roll?