14 Manuscript sources and calligraphy

The history of French medieval music is usually told as a history of written rather than sounded music, one that moves from the earliest chant notations to the mensural codes of late medieval polyphony. The present chapter on manuscript sources and their notation will continue in this tradition by revisiting some of the material from Chapters 1 and 2 with special attention to music calligraphy and book production. The manuscripts that have come down to us from the French Middle Ages are products of a particular process, one that is not always directly related to musical performance. The music scribe required a distinctive set of skills among which expert singing or playing was not necessarily included. In the blunt words of one late fourteenth-century writer, ‘not all notators are singers’.1 As emphasised in this chapter, the main goal of book producers and scribes was to produce a beautiful work of visual art. Next to this objective, whether or not a given book was to be used for musical performance was sometimes a secondary concern.

Power and proportion

Writing in the Middle Ages expressed power.2 Music writing for reasons other than the public dissemination of musical pieces may sound unusual by the standards of printed and digital books, but it was not so in the ancient and medieval world. In antiquity as in the Middle Ages, the supernatural potency of written artefacts was important enough that liturgical books were sometimes used in magic healing rituals.3 Few in medieval times could read and write. Writing and books more often than not articulated the gap between the educated elite and those to whom books were literally closed. One historian has called medieval Christianity ‘religions of the book’.4 The luxurious Gospel book that the celebrant held high during the procession at Mass, for example, embodied his power and that of the church he represented. This was also true for later vernacular literature; collections of secular songs commissioned by wealthy patrons reflected their prestige and individual interests.5 The single most important instance of this bookish power play in the history of music notation is that of the Carolingians, whose music books were used to lay imperial claims by means of the Christian liturgy and its music, a blatant case of ‘music as political programme’, in Susan Rankin’s words.6

In all of these instances, power lay in the possession of rare books and in the ability to decipher their writing. Key to the maintenance of this power was secrecy, a favourite medieval notion.7 Techniques of writing music were passed on from master to student and were not usually made public, as discussed below. Nowhere is this secrecy clearer in medieval music notation than in the complex codes of the ars subtilior. Late medieval books such as the Chantilly Codex (Château de Chantilly, Musée Condé, MS 564) present us with stunning specimens of music as a distinctly graphic phenomenon. Only the initiate could decipher these codes, and an even smaller number write them out capably. To a lesser extent the same applies to most other medieval notations. Although written out to make some information public in the modern ‘published’ sense, they were also designed to withhold a great deal of other information, to save it for those few with the power to read.

Symbolism has always played an important part in the high art of music writing.8 In the largely non-literate culture of the Middle Ages, symbols were potent and pervasive. For medieval scribes, even their tools possessed a symbolic and spiritual dimension. The quill, for example, could represent the writer’s tongue or the Holy Spirit.9 Two examples of fundamental and universal symbols relevant to this chapter are the circle and the square.10 The circle, symbol of divine perfection, can be found in the Wheel of Fortune or the sacrament of the Host. The square, symbol of the material world, is the basis for Gothic architecture drawn ‘on the square’ (ad quadratum). The unlearned medieval majority could grasp the basic message of such symbols without needing to understand the intricacies of their specific contexts. For example, it was not necessary to know the multiple Christian legends embedded in the colourful mosaic of a round Gothic stained-glass window in order to grasp the fundamental message: divine perfection embedded in a material world, symbolised by a circle within a square-shaped edifice.

Let us review the notational developments mentioned in Chapters 1 and 2 with an eye to symbolism.11 As seen in Chapter 1, France was home to some of the earliest surviving notation in the West, and this begins with the Palaeofrankish script. The fundamental grapheme in music notation is called a punctus or point, the universal symbol for a creative source, which symbolism is closely related to that of the circle.12 The punctus is the first musical note or neuma, a word attested in the earliest description of musical notes from the tenth century and commonly used thereafter.13 The word neuma or pneuma, meaning ‘spirit’ or ‘Holy Spirit’, is an unsubtle allusion to the divine status of notation, whose most famous icon is that of the Holy Spirit whispering the sacred chants into Pope Gregory’s ear.14 If the punctus is the elemental neuma of music (‘primum igitur, scilicet genus, tempus est’), it is also the first and most basic shape of geometry (‘ut est in geometricis punctum’), as the music writer Remy of Auxerre reminds his reader.15 The eleventh-century composer Odorannus of Sens goes further than this and writes that the geometrical punctus is ‘a centre around which a larger circle revolves’.16 Odorannus is here referring to the combined symbolism of the dot in the circle, the universal symbol for perfection within perfection.17 This very sign is picked up three centuries later in the ars nova graph for perfect time and perfect prolation, a dot within a circle. In the words of the treatise Ars nova, ‘the round shape is perfect’ and is thus perfectly fitted to perfect time.18 To sum up, the symbolism of the point, circle and spirit are pertinent to the elemental note of liturgical chant, the punctus.

From the foundational punctus flows a certain curviness characteristic of early French neumes. Not all shapes are round, of course, the single-stroke virga being a case in point, so to speak. But many compound neumes exhibit especial roundedness. Such is the case for the liquescent Palaeofrankish podatus with its upward swoop (Figure 14.1, far left), and the Norman clivis in the shape of a curved crook (Figure 14.1, second from left). The most striking case is the three-note torculus, whose sensuous S-shape comes out clearly in the script from Nevers (Figure 14.1, middle), whereas it forms hardly more than a half-circle in the Palaeofrankish rendering (Figure 41.1, second from right). Curviness turns decidedly exultant in such compounds as the playful Messine clivis-cum-pressus singled out by Marie-Noëlle Colette (Figure 14.1, far right).19

Figure 14.1 Early neumes: podatus (far left), clivis (second from left), S-shape torculus (middle), half-circle torculus (second from right), clivis-pressus (far right)

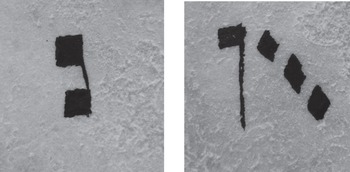

The major graphic development in the seven centuries that span medieval French notation is a move away from the roundedness just described to an angularity or squareness. Progressive monastic orders such as the Carthusians and Dominicans, the intellectual moderns (moderni) of their day, are largely responsible for the shift in medieval music calligraphy from circular shapes to square ones. It is important to stress that this change takes place gradually. Indeed, square shapes are found in several of the earliest regional neume styles, such as several versions of the punctus that tend more towards a tiny square or rectangle than a small circle; Figure 14.2, left, shows the Breton climacus, three somewhat angular punctus stacked together. Certain early compound neumes exhibit a more angular character, such as the pes from Chartres (Figure 14.2, middle).

Figure 14.2 Square notes: Breton climacus (left), two pedes from Chartres (middle and right)

It is only in the thirteenth century that such occasional quadrilateral features spread to the entire graphic gamut, at which point one finds a full-fledged square note with angular compounds. By the middle of the century, both Dominicans and Franciscans decree the nota quadrata as the standard for their music books; an unequivocal square punctus can be seen in the Dominican master book from around 1260 (Figure 14.2, right).20 The choice of square notation coincides with broader late medieval trends, such as Gothic script and a renewed interest in the natural world thanks to the newly published works of Aristotle.21 When music writers first start using the expression nota quadrata in the second half of the thirteenth century, it seems to be with the understanding that the square represents the material world. Franco of Cologne writes that the perfect long, a ‘square shape’, is considered the ‘first and principal’ note of mensural notation since it ‘contains all things and all things can be reduced to it’.22 With the shift from point to square note the musical neuma can be said to have come down to earth.

The key graphic element in this move away from curvature to angularity is the concept of tying together notes in shapes called ‘ligatures’, from the notes being tied together (ligata). Just as the general curviness of neumes had flowed from the punctus, so do the ligatures of the new musica mensurata emanate from the foundational square note. The old compound neumes are revamped as connected squares. In his description of the ligatures in French sources of his day, Anonymous IV sees the pes, for example, as a ‘quadrangle [or square] lying upright above a quadrangle’ (see Figure 14.3, left).23Anonymous IV emphasises the geometrical aspect of these new notes by calling rhomboid shapes elmuahim and elmuarifa, which is Euclidean jargon from newly translated Arabic sources. The old climacus, for example, is now a square followed by ‘two, three or four elmuahim’ (Figure 14.3, right).24 That thirteenth-century music writers speak often of the ‘properties’ (proprietates) of these ligatures is yet one more nod to their double origin in the esoteric ‘properties’ of music and in a new Aristotelian emphasis on the material world.25 These new notes are ‘material’ points, puncta materialia, in Anonymous IV’s expression.26

Figure 14.3 Square ligatures: pes (left), climacus (right)

These important graphic developments in French medieval notation probably would not have occurred without important alterations to page layout in the course of the eleventh and twelfth centuries. Guido d’Arezzo’s proposal for the stave in the eleventh century did impact on book production, as is frequently stated; but it was only one phase in a larger development. In the following centuries, certain French monastic orders made equally important changes to how liturgical music was laid out on the page.27 The impact on book culture of these groups – some of the most innovative and powerful orders emerging in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries – reflects their aspirations for literary control and, in the case of the Dominicans, political domination.

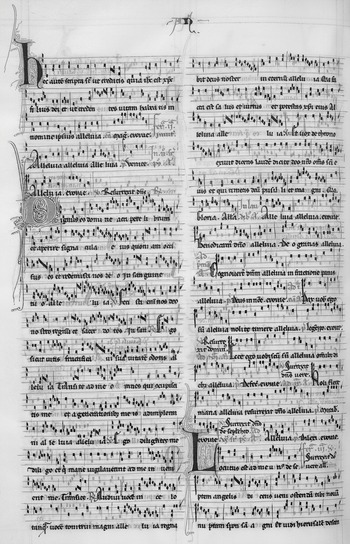

In the twelfth century the Carthusians were responsible for an impressive production of books.28 Key to their signature layout for music books was a pricking and ruling pattern that produced a special harmony between music and text; the text line received a double prick and extra space, as seen in Figure 14.4. The Carthusians also adopted the Aquitanian punctus, which was more angular than that found in other regions.

Figure 14.4 Pricking and ruling pattern in a Carthusian gradual

These innovations in page layout were furthered in the following century by the powerful Dominicans. Their music-book regulations included not only the nota quadrata, as mentioned earlier, but also a stave with four lines spaced ‘a little apart’ (debito modo).29 A page from a copy of the Dominican master book of around 1260 makes clear their achievement (Figure 14.5). As in the intricately lined architectural plan of a Gothic cathedral, lines and grids criss-cross the Dominican page, deftly confining and defining areas of text and music in an elegant proportion – a supreme achievement considering the small size of this particular book (26.2 × 17.6 cm).30 Into this Gothic grid sits the new nota quadrata, the square that ‘contains all things and [to which] all things can be reduced’, in the words of Franco of Cologne cited earlier.

Figure 14.5 Dominican master book from c. 1260

Extant and lost sources

Unfortunately, little has come down to us of the impressive music-writing activity just described, in France as elsewhere in the Middle Ages. In the case of the Cistercians, only one twelfth-century source survives, in the Bibliothèque Municipale de Dijon (MS 114). This sizable liturgical master book (48 × 32 cm) has lost its main musical sections, with only a few scraps of music notation found on fols 102v, 114v, 133–4 and 151r.31 In fact, these few pages from the Cîteaux liturgical master book are, to my knowledge, the only trace of Cistercian music writing in all of twelfth-century Europe that remains today. Another group from the same century, the Carthusians, have fared considerably better. Yet even for the Carthusians’ main library at the Grande Chartreuse, praised in the twelfth century as having ‘an ocean of books’, only a handful of music sources survive from the 1100s.32 Extant medieval manuscripts, then, represent only a fraction of the complete number of books produced in the Middle Ages.

Adding to this loss of presentation-copy parchment books is the near-total absence of the many modest or impermanent sources of which the extant manuscripts are the final and most expensive products. Ancient and medieval writing was a process that was typically divided into stages. The Romans distinguished between taking notes (notare), making an outline and draft (formare) and correcting the draft to produce the final version (emendare).33 General medieval book production was similar. The mostly high-grade manuscripts that have survived were often copied from exemplars ranging from wax tablets to parchment booklets (libelli).34 Almost no specimens survive for the first stage of music writing, note-taking, because notes were usually written on perishable surfaces, the most common of which was the tablet. The ‘Middle Ages … was a wax-tablet culture’, write Richard and Mary Rouse; Bernhard Bischoff states that medieval ‘daily life cannot be imagined without them [i.e. wax tablets]’.35 Recent research has made clear that the perishable medium of wax tablets was common in writing music, even though no medieval wax with musical notes survives.36 The most famous proof of this is a tenth-century depiction of a scribe, presumably Peter the Deacon, writing neumes on a large wax tablet as St Gregory dictates.37 This image evokes a scenario that was ubiquitous with that most common ancient and medieval shorthand system, the Tironian notes: a scribe rapidly taking dictation on wax as an official speaks.38

Concerning the second and third stages of writing (formare and emendare), the extant sources leave us some clues that increase in number as the Middle Ages progress. By far the most abundant type of medieval music book is that associated with the Christian church. The history of these liturgical manuscripts can be succinctly described as a move towards large, heterogeneous collections of previously separate libelli. The earliest full books with music present selective chants, such as the tenth-century southern French collection of tropes Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, lat. 1118, and the twelfth-century Norman cantatorium-troper-tonary Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, lat. 10508.39 By the late Middle Ages, such selective volumes had been subsumed into larger and more compact collections, such as the gradual, antiphoner and breviary. A late medieval missal, for example, typically contains the Kalendar, a small libellus opening the book, followed by chants, prayers and readings for the entire liturgical year, as well as various tropes and miscellaneous musical pieces.40 There is every reason to believe that the page layout of these complex hybrid sources often required a draft or two before the final parchment version, as Andrew Hughes once suggested.41 We should not forget certain books on the fringe of the French liturgy, such as the two early thirteenth-century exemplars of the Feast of Fools, one from Sens (Bibliothèque Municipale 46) and the other from Beauvais (London, British Library, Egerton 2615). Both contain the same proper items for the feast, but the Beauvais book adds four gatherings for polyphony and a liturgical play (gatherings 11–14).42 Here as in the preceding cases, the medieval process of collation and copying is clear, with each individual liturgical source presenting a mixture of standard and unique elements.

The earliest complete sources of French polyphony are liturgical manuscripts. The famous thirteenth-century Parisian collection of organa complements such comprehensive liturgical books as the missal, for it presents polyphonic music performed at certain points during selected feasts. The precious report of Anonymous IV makes clear that a ‘great book of organum’ was compiled over time from a variety of sources, from parchment exemplars (pergameno exempla) to various ‘volumes’ and ‘books’ of organum that would eventually make up the famous ‘great book’.43 He gives the contents of the great book in a list that reads like a series of volumes. In the extant sources, pieces are ranked by number of voices, opening with prestigious four-voice pieces, moving on to pieces in three, then two voices, and ending with monophonic works. Extant sources such as manuscript F (Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Plut. 29.1), copied in Paris in the middle of the thirteenth century, confirm that the great book was made of smaller libelli. The parts of the ‘great book of organum’ identified by Anonymous IV correspond to individual groupings of gatherings (see Table 14.1).

Table 14.1 Sources of Notre-Dame polyphony: Anonymous IV’s description and corresponding contents in F

The process of copying and collating becomes even clearer with authorial collections that first appear around the same time as the extant Notre-Dame sources.44Gautier de Coinci is the first known author and editor of a major work to include music, Les miracles de Nostre Dame, and it is telling that this new kind of author-centred work is in Old French rather than Latin.45 Gautier composed his lengthy two-volume Miracles over nearly two decades.46 The eighty-plus extant manuscripts of the Miracles attest to a work written down in stages; only twelve have music notation and only one of these has the full set of twenty-two songs with music notation (Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, nouv. acqu. fr. 24541). Another of the manuscripts of Gautier’s Miracles offers us a rare glimpse into the copying process, for it shows Gautier sight-reading on the vielle from an open bifolium of music, suggesting that smaller exemplars with just music were among those used to compile the monumental Miracles (Figure 14.6).47

Figure 14.6 Gautier de Coinci sight-reading music for the vielle

Gautier’s is the first of several authorial collections produced in the thirteenth century. A few decades after Gautier, the noble trouvère Thibaut de Champagne evidently supervised a book of his own songs called Les chansons au roy de Navarre; it was written up around 1250 ‘in his hall at Provins’, just south of where Gautier had copied his Miracles near Soissons.48 This collection and slightly later libelli of songs by the troubadour Guiraut Riquier (who dated his compositions, sometimes down to the day49) and the trouvère Adam de la Halle were eventually integrated into larger song anthologies, and it is as booklets in these larger anthologies that the libelli of Thibaut, Guiraut and Adam have survived. The chansonniers of the trouvères are the result of an intense collating and copying activity of vernacular songs during the period around 1300. One chansonnier features several images of scribes writing on parchment rolls (Figure 14.7). One roll of trouvère songs does survive, although regrettably without music.50 A handful of the chansonniers (sigla KNPX) are so similar as to leave no doubt that common exemplars of some sort were used. Others attest to a collating process in that they present unique combinations such as troubadour and trouvère songs with motets, or discrete libelli of songs by genre such as pastourelle, lai or jeu-parti. Contemporary with the chansonniers and related to Gautier’s Miracles are vernacular romances and other literary works containing notated music.51 The most imposing of these is Renart le nouvel (c. 1300) with its seventy-plus refrains, many of which were either copied from or used to copy motet sources.52 The endpoint of this tradition of romances with insertions is the famous manuscript of the Roman de Fauvel copied in Paris by Chaillou de Pesstain around 1316 (Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, fr. 146), a heterogeneous collection par excellence and something of a medieval musical summa with its stunning specimens of chant, vernacular song and polyphony.53

Figure 14.7 Scribe of trouvère songs writing on a parchment roll

The second half of the fourteenth century presents us with a composer who combines the vernacular chansonnier and ‘great book of organum’ traditions. Guillaume de Machaut compiled his musical and poetic works over several decades from around 1350 to his death in 1377. During this process, Machaut’s works circulated in a variety of forms, from booklets to small parchment swatches.54 One of Machaut’s lais, the Lay mortel, even survives with its music on a parchment roll.55 And indeed, Machaut is depicted more than once as writing on a parchment roll, a practice going back to the trouvère seen earlier (Figure 14.8; cf. Figure 14.7).56 The extant manuscripts of Machaut’s complete works testify to such an intricate compilation, one involving ‘a small army of messengers and copyists’, in Sarah Jane Williams’s words.57 A study of the extant manuscripts shows that Machaut’s complete works were compiled even as he continued producing new pieces. Manuscript C from the 1350s, for example, opens with literary works such as the Remede de Fortune and ends with musical pieces ranging from virelais to motets (see Table 14.2). Literary works are prominent in this book; the Remede, for example, is a self-contained booklet (gatherings 4–8), with four folios fleshing out the final quaternion and making an independent libellus. The musical works are more like an afterthought, beginning as they do in the middle of the nineteenth gathering near the end of the book. Dating from two decades later, manuscript A has added several more literary works such as the Prologue, as well as a significant amount of music, here standing independently as a libellus within a larger codex. Machaut’s music opens with gathering 47 as a separate section and takes up fully a quarter of his complete works. It includes recently composed independent pieces such as the Mass, as well as music inserted in the Remede, none of which is found in manuscript C of two decades earlier. Machaut’s manuscripts may well foreshadow the later printed authorial collected works, as is sometimes pointed out, but more significantly they arise out of a long-standing medieval tradition of book production and music writing.

Figure 14.8 Machaut reading a parchment roll

Table 14.2 Comparison of the contents of Machaut manuscripts C and A

The calligraphy of medieval music

If only a small portion of the total music writing from medieval France has survived, even less has come down to us concerning technical aspects of music writing. There is no testimony prior to the twelfth century, despite the fact that music scribes were often highly trained calligraphers. The few statements found so far on their craft do not necessarily occur in literature primarily devoted to music.58 This is partly because most medieval writers on music were typically concerned with theory rather than practice. When Boethius discusses the writing-out (scriptio) of musical notes (notulas), for example, he makes an exhaustive list of the names for the Greek and Latin letters used for music, but devotes not a word to the tools or techniques used to draw these letters.59 The lack of first-hand information on music-writing technique is also due to a general silence on most trades prior to the late Middle Ages.60 This is probably because craft-making techniques were usually passed on orally, being secrets of the trade jealously guarded by competing practitioners. The eleventh-century music scribe Adémar de Chabannes apparently has nothing to say about his skill, for example, even though hundreds of folios with notation in his hand survive.61Anonymous IV breaks this silence for music writing in the thirteenth century, discussing various writing surfaces, stave types and notational traditions and teachers; he goes on to describe with exactitude how seventeen note shapes should be drawn out.62

Beyond this, what can be known about the music-writing trade must be extrapolated from general scribal culture in the Middle Ages. It is important to stress that France was a major production centre of medieval books. The shift from round to square notes described at the beginning of this chapter coincides with a transition from monastic to secular writing centres.63 Before 1100, most manuscripts were copied in monasteries, usually in a room within the monastery reserved for this purpose, the scriptorium. In larger scriptoria, the making of a manuscript was divided into tasks, with one person ruling the parchment, another writing the text and yet another, the notator, writing the music. In some cases, a certain hierarchy obtained, with a head notator supervising less skilled notatores.64 With the Carthusians, each monk was a professional scribe, with his own cell a private scriptorium equipped with all the necessary tools for writing.65 The monopoly of monastic scriptoria disappeared in the late Middle Ages with the rise of secular writing ateliers for profit. The result was a dramatic increase in the number and types of books produced, including some of the vernacular manuscripts discussed earlier in this chapter. The picture for the city of Paris in the thirteenth century is of ‘countless scribes’ – in the words of Roger Bacon – competing for a clientele ranging from university students to wealthy private patrons; many of them lived in their own neighbourhoods, such as the Rue des Écrivains.66 Scribal advertisement sheets featuring musical notation have survived, showing that the skill of writing music was vital in the late medieval book-selling industry.67 We get a glimpse of scribal competitiveness from the same fourteenth-century writer cited at the beginning of this chapter, who complains that ‘scribes leave too much space between syllables, and notators fill up the space, caring only to make money’.68

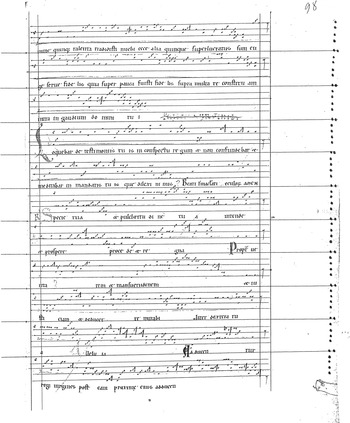

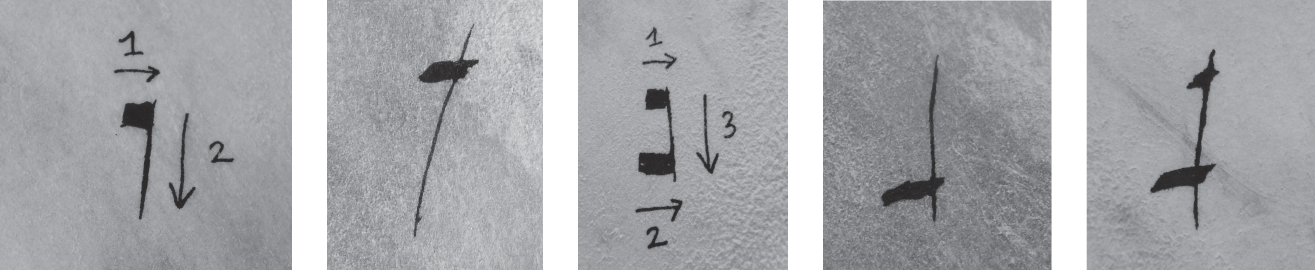

Anonymous IV’s description of how thirteenth-century notes are drawn provides us with a small window into the calligraphic art of medieval scribes. The order of pen strokes he relates is not always the most straightforward one from a modern point of view. For example, he describes a three-note ligature as a series of four separate pen strokes that incorporates the longa; ‘it should look like an oblong shield’, he adds (see Figure 14.9, left).69 From a modern point of view, it would be quicker to draw this ligature without lifting the pen by inverting steps 3 and 4 and making one single, smooth motion. Nevertheless, manuscript evidence matches Anonymous IV’s descriptions. A close-up look at the Dominican master book discussed earlier (Figure 14.5) shows the porrectus drawn Anonymous IV’s way, with protruding and slightly separated strokes betraying where the pen has lifted (Figure 14.9, centre). If this way of doing things does not seem the most logical by modern standards, we should remember that even in today’s calligraphic practices, virtues such as tradition trump that of speed. The Arabic letter kaaf (initial position), for example, is drawn in two strokes even though it would be quicker, though less elegant, to draw it in one step (Figure 14.9, right).

Figure 14.9 Two versions of the porrectus (left, middle), and the Arabic letter kaaf (right)

Anonymous IV’s report of thirteenth-century Parisian musical calligraphy does have the ring of traditional authenticity. Several of his descriptions can be shown to originate in a much older calligraphic practice. For example, implicit in his description of the longa – or virga as it was called in earlier times – is a drawing in two strokes: ‘[a] square with a line descending from its right side’ (Figure 14.10, far left).70 This way of drawing the virga in a distinctive two-stroke sequence (punctus plus tail) can be found in some of the earliest French musical calligraphy (Figure 14.10, second from left).71 The virga appears to have been drawn in the order implied by Anonymous IV, first the punctus and then the line crossing through it. In another instance, Anonymous IV says the pes should be drawn as ‘a square lying above a square … joined with one line on their right side’ (Figure 14.10, centre). The two-stroke sequency implied in this description is clear in certain earlier French renditions of the pes, such as that from Fécamp in Normandy (Figure 14.10, second from right) or Saint-Maur near Paris (Figure 14.10, far right).72 In both cases, the protrusion of the vertical stroke shows that the pen was lifted rather than held in one continuous motion. It seems, therefore, that certain French calligraphic conventions for music had a long life, originating in the earliest phase and enduring well into the square notation period.

Figure 14.10 Two versions of the virga (left) and three of the pes (right)

The reason why the craft of medieval writing matters to music history is that its media and tools at times played an important role in shaping the graphic vocabulary of music. The musical stave, for example, was nothing more than an elaboration of the basic dry ruling patterns found in the earliest medieval books. It was common practice from early on to rule the page with dry, horizontal lines first. It is easy to see how the sight common to medieval scribes of a rectangular grid with horizontally ruled lines on which sat black graphemes almost inevitably led to the musical stave as we know it.73 As for the notes themselves, they bear features specific to the tools that produced them. For example, the sinewy shaded lines so characteristic of the early curvy neumes shown in Figure 14.1 are the natural calligraphic product of a quill charged with black ink. The quill’s flexible beak makes possible a subtly varied thickness of line that is used to special effect in such neumes as the Norman clivis or the Messine elaborated clivis.

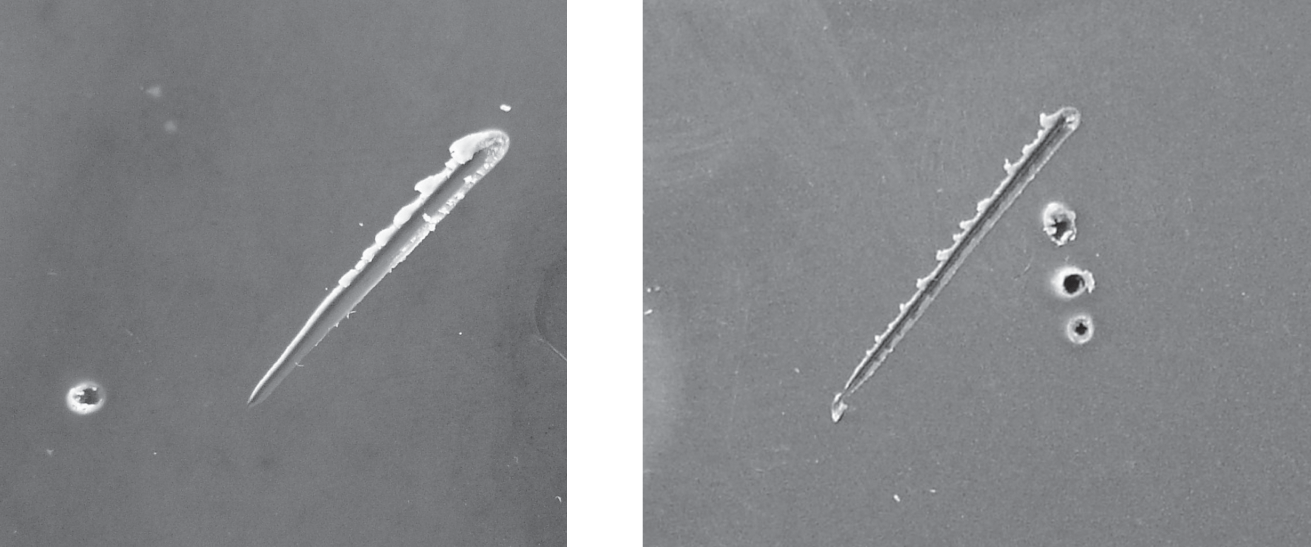

The above are observations based on the extant books. But as suggested throughout this chapter, lost musical graphic evidence should be taken into account too, even if this involves a certain amount of hypothesising. In conclusion, we may look briefly at the most common writing tools of medieval daily life, the wax tablet and stylus. More so than with parchment or paper, the wax surface requires an economy of movement; fewer strokes are better. The stylus moves like a plough through the resistant wax, creating a furrow bounded on either side with tiny mounds of excess wax (see Figure 14.11). The ancient and medieval scribes of the famous Tironian notes knew this first-hand and consequently developed an abbreviation code requiring minimal motion over the wax surface. For example, the Tironian abbreviation for absens is a point followed by a slanted stroke; that for essem, a horizontal stroke over a point (Figure 14.11).74 These markings are easy to make and to erase.

Figure 14.11 Tironian notes and neumes in wax

Such is also the case for the basic code of the earliest musical notes. As mentioned at the beginning of this chapter, the basic building blocks of music calligraphy are a point (punctus) and a stroke (virga). Like the Tironian notes, these shapes are conveniently traced in wax and result in a minimum of wax build-up around each mark (Figure 14.12, left). It is significant that a compound neume such as the clivis, when drawn in wax, bears an uncanny resemblance to the Tironian signs just mentioned (Figure 14.12, right). It is not clear whether there existed a specific connection between the earliest neumes and Tironian notation.75 But it is certainly possible, given that scribes such as Adémar de Chabannes were equally versed in music and Tironian notation.76 Indeed, for most bookish persons in the Middle Ages, the word notae would have first conjured up Tironian rather than musical notes.77 On this subject, as on many others only briefly touched upon in this chapter, more research remains to be done.

Figure 14.12 Neumes in wax

If, as I have suggested here, continuities from one scribal tradition to the next can be observed throughout the high tradition of music writing in the Middle Ages, such continuities are even more evident during the transition from manuscript to print in the Renaissance. Little was to change: the layout of the page, from the basic writing block to the look of the musical stave; the shapes and colours of the stave and its notes; and the rhythmic interpretation of these notes – all these aspects were carried over from medieval music books to early printed ones in the late 1400s and the 1500s. Even today, over five centuries after the first French printed books with music, the influence of medieval music scribes and book producers is still felt. When we write musical notes or input them on our computers, either single (simplices, in the words of late medieval writers) or ‘ligated’, we continue a tradition that can be traced back to the earliest extant medieval manuscripts with music, and even further back yet, to their lost ancestors.

Notes

I would like to thank Karl Kügle, Barbara Menich, Randall Rosenfeld and the students in my ‘Music Notation of the Middle Ages’ seminars for their collective insights. I drew all the figures of individual note shapes for this chapter using quills, parchment, wax and styluses.

1 (ed.), Scriptorum de musica medii aevi: novam seriem a Gerbertina alteram, 4 vols (1876; repr. Hildesheim: Olms, 1963), vol. IV, 253.

2 , The History and Power of Writing, trans. (University of Chicago Press, 1994), 116–81.

3 , A History of Magic and Experimental Science during the First Thirteen Centuries of our Era, 2 vols (New York: Columbia University Press, 1923), vol. I, 759.

4 Martin, History and Power, 102–15.

5 Ibid., 154–65; , Eight Centuries of Troubadours and Trouvères: The Changing Identity of Medieval Music (Cambridge University Press, 2004), 25.

6 , ‘Carolingian music’, in (ed.), Carolingian Culture: Emulation and Innovation (Cambridge University Press, 1994), 275–6; see Martin, History and Power, 124–9.

7 , Science and the Secrets of Nature: Books of Secrets in Medieval and Early Modern Culture (Princeton University Press, 1994).

8 Martin, History and Power, 4.

9 and , ‘The tongue is a pen: Robert Grosseteste’s Dictum 54 and scribal technology’, Journal of Medieval Latin, 12 (2002), 119.

10 and , A Dictionary of Symbols, trans. (London: Penguin, 1996), 195–200, 912–18.

11 Surveys of the different neume types include , Die Neumen (Cologne: Arno Volk, 1977); , Western Plainchant: A Handbook (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993), 346–56; and , ‘Élaboration des notations musicales, IXe–XIIe siècle’, in , and (eds), Histoire de la notation du Moyen Âge à la Renaissance (Paris: Minerve, 2003), 11–89.

12 Chevalier and Gheerbrant, Dictionary of Symbols, 305–6.

13 , ‘Die Überlieferung der Neumennamen im lateinischen Mittelalter’, in (ed.), Quellen und Studien zur Musiktheorie des Mittelalters (Munich: Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1997), vol. II, 14. As Bernhard’s catalogue shows, the word punctus is more common in the earliest descriptions of notes than the word punctum, although they both mean the same thing: ibid., 19–25, 54–60.

14 Corbin, Die Neumen, 1–2.

15 (ed.), Scriptores ecclesiastici de musica sacra potissimum (1784; repr. Hildesheim: Olms, 1963), 1, 81.

16 , Opera omnia, ed. and (Paris: CNRS, 1972), 212.

17 , Fundamental Symbols: The Universal Language of Sacred Science, ed. , trans. (Cambridge: Quinta Essentia, 1995), 46–7.

18 Philippi de Vitriaco Ars nova, ed. et al., Corpus Scriptorum de Musica, 8 (Rome: American Institute of Musicology, 1964), 24.

19 Colette, ‘Élaboration des notations musicales’, 58.

20 , ‘Règlement du XIIIe siècle pour la transcription des livres notés’, in (ed.), Festschrift Bruno Stäblein zum 70. Geburtstag (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1967), 124.

21 , Latin Palæography: Antiquity and the Middle Ages, trans. and (Cambridge University Press, 1995), 173–6; , ‘Anonymous IV as an informant on the craft of music writing’, Journal of Musicology, 23 (2006), 389–90, 397–400.

22 , Ars cantus mensurabilis, ed. and , Corpus Scriptorum de Musica, 18 (Rome: American Institute of Musicology, 1974), 30.

23 Haines, ‘Anonymous IV’, 393.

24 Ibid., 395.

25 See , ‘Proprietas and perfectio in thirteenth-century music writing’, Theoria, 15 (2008), 5–29; , ‘On ligaturae and their properties: medieval music notation as esoteric writing’, in (ed.), The Calligraphy of Medieval Music (Turnhout: Brepols, 2011), 203–22.

26 Haines, ‘Anonymous IV’, 389.

27 , ‘The origins of the musical staff’, Musical Quarterly, 91 (2009), 327–78.

28 , Prêcher en silence: enquête codicologique sur les manuscrits du XIIe siècle provenant de la Grande Chartreuse (Saint-Étienne: Université Jean Monnet, 2004), 242.

29 Huglo, ‘Règlement’, 124.

30 , Medieval Architecture (Oxford University Press, 2002), 65–81.

31 For a description of MS 114, see , Manuscrits enluminés de Dijon (Paris, 1991), 117–19. Jean de Cirey’s fifteenth-century inventory of the books at Cîteaux refers to several now-lost medieval books with music, the problem being Jean’s inconsistent specification of musical notes and age of manuscripts; see et al., Catalogue général des manuscrits des bibliothèques publiques de France, vol. V: Dijon (Paris: Plon-Nourrit, 1880), 517–52, 925–1006.

32 Becdelièvre, Prêcher en silence, 242. Carthusian music sources are discussed in Haines, ‘The origins of the musical staff’.

33 Martin, History and Power, 71.

34 , ‘The musicography of the Manuscrit du roi’ (PhD thesis, University of Toronto, 1998), 87–92.

35 and , Manuscripts and their makers: Commercial Book Producers in Medieval Paris, 1200–1500 (Turnhout: Harvey Miller, 2000), quoted in , ‘Technologies for musical drafts, twelfth century and later’, Plainsong and Medieval Music, 11 (2002), 54; Bischoff, Latin Palæography, 14.

36 The indispensable study on this topic is Rosenfeld’s landmark essay cited earlier, ‘Technologies for musical drafts’; see also Haines, ‘The musicography of the Manuscrit du roi’, 89–90.

37 and , ‘The portrait of the music scribe in Hartker’s Antiphoner’, in (ed.), Pen in Hand: Medieval Scribal Portraits, Colophons and Tools (Walkern: Red Gull Press, 2006), 19–30.

38 On wax tablets and Tironian notes, see and , Histoire de la sténographie dans l’antiquité et au Moyen-Âge: les notes tironiennes (Paris: Hachette et Cie, 1908), 93–103, 233–5 n. 1. Generally on wax tablets, see (ed.), Les tablettes à écrire de l’antiquité à l’époque moderne: actes du colloque international du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Paris, Institut de France, 10–11 octobre 1990, Bibliologia, 12 (Turnhout: Brepols, 1992). For the dictator-notator scenario in a late medieval context, see , ‘Did John of Tilbury write an Ars notaria?’, Scriptorium, 62 (2008), 46–73.

39 See , Les livres de chant liturgiques (Turnhout: Brepols, 1988). On lat. 10508, see , Guido d’Arezzo’s Regule rithmice, Prologus in antiphonarium and Epistola ad Michahelem: A Critical Text and Translation (Ottawa: Institute of Medieval Music, 1999), 175–6.

40 See , Medieval Manuscripts for Mass and Office: A Guide to their Organization and Terminology (University of Toronto Press, 1982), 158.

41 , ‘The scribe and the late-medieval liturgical manuscript: page layout and order of work’, in et al. (eds), The Centre and its Compass: Studies in Medieval Literature in Honor of Prof. John Leyerle (Kalamazoo, MI: Western Michigan University, 1993), 151–224.

42 For this and related sources, see Hiley, Western Plainchant, 39–42.

43 Haines, ‘Anonymous IV’, 384.

44 , Poetry and Music in Medieval France: From Jean Renart to Guillaume de Machaut (Cambridge University Press, 2002), 103–21, 306–7; Haines, Eight Centuries, 20–2; and and (eds), Gautier de Coinci: Miracles, Music and Manuscripts (Turnhout: Brepols, 2006).

45 See , La subjectivité littéraire (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1985).

46 Kathryn Duys, ‘Minstrel’s mantle and monk’s hood: the authorial persona of Gautier de Coinci in his poetry and illuminations’, in Krause and Stones (eds), Gautier de Coinci, 40.

47 Ibid., 53, figure 1.

48 Haines, Eight Centuries, 35.

49 , ‘Cyclical composition in Guiraut Riquier’s book of poems’, Speculum, 66 (1991), 277–93.

50 Haines, ‘The musicography of the Manuscrit du roi’, 90–1.

51 See Butterfield, Poetry and Music.

52 , Satire in the Songs of Renart le nouvel (Geneva: Droz, 2010), 79–110.

53 and (eds), Fauvel Studies: Allegory, Chronicle, Music, and Image in Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, MS Français 146 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998).

54 , Guillaume de Machaut: A Guide to Research (New York: Garland, 1995), 73–4.

55 , ‘An author’s role in fourteenth-century book production: Guillaume de Machaut’s “Livre ou je met toutes choses”’, Romania, 90 (1969), 446.

56 , Guillaume de Machaut, 152, 155, 156, 163, 173, 184, 186; cf. Kathleen Wilson Ruffo, ‘The illustration of notated compendia of courtly poetry in late thirteenth-century northern France’ (PhD thesis, University of Toronto, 2000), vol. I, 166–7; vol. II, figures 109–10.

57 Williams, ‘An author’s role’, 446.

58 Rosenfeld, ‘Technologies for musical drafts’, 47–51.

59 , Traité de la musique, ed. (Turnhout: Brepols, 2004), 236–43.

60 Cf. Thorndike, History of Magic, 760–74.

61 , The Musical World of a Medieval Monk: Adémar de Chabannes in Eleventh-Century Aquitaine (Cambridge University Press, 2006), 37–96.

62 Haines, ‘Anonymous IV’, 381, 384–6, 391–7.

63 , Scribes and Illuminators (University of Toronto Press, 1992), 4–7.

64 , ‘The office of the cantor in early Western monastic rules and customaries: a preliminary investigation’, Early Music History, 5 (1985), 48–51.

65 Haines, ‘Anonymous IV’, 381, 385 n. 39.

66 Rouse and Rouse Manuscripts and their Makers, 23–32.

67 De Hamel, Scribes and Illuminators, 40.

68 Coussemaker (ed.), Scriptorum, vol. IV, 253.

69 Haines, ‘Anonymous IV’, 395.

70 Ibid., 392.

71 Colette, ‘Élaboration des notations’, 27–8. A clearer and earlier example is Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, lat. 11958, fol. 14.

72 Corbin, Die Neumen, 104–6; Colette, ‘Élaboration des notations’, 27–8.

73 Haines, ‘The origins of the musical staff’, 337.

74 , Introduction à la lecture des notes tironiennes (1900; repr. New York: Franklin, 1960), 4, 73.

75 The various theories on the origins of musical notation are laid out in Hiley, Western Plainchant, 361–73. On the Tironian note hypothesis, see and , L’archéologie musicale et le vrai chant grégorien (Paris: P. Lethielleux, 1890), 330–41.

76 Grier, Musical World, 281–2.

77 See , review of , With Voice and Pen, Journal of Plainsong and Medieval Music, 14 (2005), 230–2.