Introduction

The genus Mononchoides was described by Rahm in 1928 based on the longitudinally striated (ridged) cuticle and buccal cavity having a large dorsal tooth, a right subventral tooth and small denticles. Goodey (Reference Goodey1963) revised the genus Mononchoides and listed 11 species in the group. Later, four species were added to the genus – namely, M. adjunctus Massey, 1966, M. fortidens (Shuurmans Stekhoven, 1951) Taylor & Hechler, 1966, M. changi Goodrich, Hechler and Taylor, 1968 and M. bollingeri Goodrich, Hechler and Taylor, 1968. Calaway and Tarjan (Reference Calaway and Tarjan1973) revised the group, listed 18 valid species and considered M. longicauda (Rahm, 1928) as the type species of the genus. However, Goodey (Reference Goodey1963) synonymized M. longicauda (Rahm, 1928) with Diplogaster (=Mononchoides) striatus (Bütschli, 1876) and considered it as the type species of the genus Mononchoides. Later, Andrássy (Reference Andrássy1984) revised the group and synonymized five species – namely, M. bicornis (Rahm, Reference Rahm1928), M. linocercus (Völk, 1950), M. longicaudatus (Khera, 1965), M. parastriatus (Paesler, 1946) and M. subdentatus (Gunhold, 1952) – under the genus Mononchoides. Gagarin (Reference Gagarin1993, Reference Gagarin1998, Reference Gagarin2000, Reference Gagarin2001) added five species to the group, providing a key to the species. The intricacies of stoma morphology within the family were not clarified until Fürst von Lieven & Sudhaus (Reference Fürst von Lieven and Sudhaus2000) illustrated the ultrastructure and provided updated diagnostic characters of an unnamed species in the genus Mononchoides. Sudhaus & Fürst Von Lieven (Reference Sudhaus and Fürst Von Lieven2003) synonymized several species and listed 43 valid species under the genus. After that, nine species were added to the genus: six on the basis of light microscope data only (Siddiqi, Reference Siddiqi2004; Siddiqi et al., Reference Siddiqi, Bilgrami and Tabassum2004; Mahamood et al., Reference Mahamood, Ahmad and Shah2007; Yousuf et al., Reference Yousuf, Mahamood, Mumtaz and Ahmad2014) and three with supporting molecular data – namely, M. composticola Steel, Moens, Scholaert, Boshoff, Houthoofd and Bert, 2011 (small subunit (SSU) 18S ribosomal DNA (rDNA)), M. iranicus Atighi, Pourjam, Kanzaki, Giblin-Davis, De Ley, Mundo-Ocampo, and Pedram, 2013 (D2/D3 domain of large subunit (LSU) 28S rDNA) and M. macrospiculum Troccoli, Oreste, Tarasco, Fanelli and De Luca, 2015 (SSU 18S rDNA and D2/D3 domain of LSU 28S rDNA). Of the dozens of species first described in the previous century, only M. adjunctus (Massey, 1966) was redescribed based on the information that included SSU 18S rDNA (Mehdizadeh et al., Reference Mehdizadeh, Shokoohi and Abolafia2013). Currently, out of 46 valid species, only two species – M. composticola Steel, Moens, Scholaert, Boshoff, Houthoofd and Bert, 2011 and M. iranicus Atighi, Pourjam, Kanzaki, Giblin-Davis, De Ley, Mundo-Ocampo, and Pedram, 2013 – were described with the inclusion of scanning electron microscopic (SEM) observations.

The present paper deals with the description of M. kanzakii sp. n. and M. composticola Steel et al., 2011 supplemented with their molecular characterization using SSU 18S rDNA and the D2/D3 domain of LSU 28S rDNA gene markers. The phylogenetic analysis was carried out using Bayesian inference to confirm the separate status of the apparently morphologically similar species among the congeners and the congruence in their placement.

Materials and methods

Collection of soil samples/insects

The species were collected from manure and the shore of the Ganga River (contaminated with the effluents of tanneries) from the district Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh, India. Besides the soil sample, M. composticola Steel et al., 2011 was also isolated from the dung beetle Oniticellus cinctus (Fabricius, 1775), collected from a cowpat in the Terai region of Balrampur, eastern Uttar Pradesh, India. The soil samples were placed in a polybag, and beetles were kept in a plastic vial containing a small amount of dung/manure and covered with a lid perforated for aeration, before bringing them to the laboratory.

Extraction/isolation of nematodes

Nematodes from the soil samples were extracted using Cobb's (Reference Cobb1918) sieving and decantation method and the modified Baermann (Reference Baermann1917) funnel technique. From the insects, the nematodes were isolated by dissection and plating. The beetles were washed with distilled water 3–4 times and placed on an ice pack to make them inactive. The beetles were excised and plated on 1.5% nematode growth medium plates with head, elytra and abdominal cavity placed separately to study microhabitat specificity.

Light microscopy (LM) and SEM study

For LM, the nematodes were fixed in 4% formalin, processed to anhydrous glycerine (Seinhorst, Reference Seinhorst1959) and mounted on glass slides using the wax ring method (De Maeseneer & D'Herde, Reference De Maeseneer and D'Herde1963). The nematodes were observed under an Olympus BX51 microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), drawn using a drawing tube and photographed using a Jenoptik ‘ProGress’ camera (Jena, Germany) mounted on the microscope. For SEM, the nematodes were processed following the protocol adopted by Mahboob et al. (Reference Mahboob, Chavan, Nazir, Mustaqim, Jahan and Tahseen2021) involving fixation in SEM fixative (1.6% paraformaldehyde and 2.5% glutaraldehyde), washing in phosphate buffer and dehydration in ethanol grades. The dehydrated nematodes were dried in a critical point dryer using carbon dioxide, mounted on a stub on double-sided adhesive tape and coated with 10 nm gold before observing at 10–15 kV under a Hitachi 4000 Plus scanning electron microscope (Hitachi, Tampines Grande, Singapore).

Molecular characterization

For DNA extraction, five individuals were picked from the culture to prepare a temporary mount and verify their identity under an Olympus CX31 microscope. After identification, the nematodes were cut or smashed using a sharp blade and transferred to an Eppendorf tube containing 20 μl lysis buffer (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Schrank, Huynh, Shownkeen and Waterston1992) and incubated in a thermocycler at 65°C for 45 min, followed by 95°C for 15 min. For DNA amplification, 5 μl DNA template was used in 20 μl polymerase chain reaction (PCR) reaction mix following the manufacturer's protocol (GeNei, Bengaluru, India). For the amplification, we used the forward primer SSU18A-5′–AAAGATTAAGCCATGCATG′–3′ and reverse primer SSU26R-5′–CATTCTTGGCAAATGCTTTCG–3′ for amplifying SSU 18S rDNA, and the forward primer 5′–ACAAGTACCGTGAGGGAAAGTTG–3′ and reverse primer 5′–TCCTCGGAAGGAACCAGCTACTA–3′ for amplifying the D2A/D3B domain of LSU subunit 28S rDNA. PCR was performed at 94°C for 2 min, followed by 35 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 57°C for 45 s, 72°C for 3 min and final extension for 10 min at 72°C for SSU 18S rDNA vs. initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min; followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, 72°C for 1 min and final extension for 10 min at 72°C for D2A/D3B domain of LSU subunit 28S rDNA. Sequencing was done in both directions.

Phylogenetic analysis

The newly obtained sequences were edited in Chromas version 2.6.6. (Technelysium Pty Ltd, www.technelysium.com.au) to remove the ambiguous sequences from both extremities. Both sequences (forward and reverse) were aligned in BioEdit (Hall, Reference Hall1999) and a consensus sequence generated. The sequences of M. composticola of SSU 18S rDNA (800 bp) and of the D2/D3 domain of LSU 28S rDNA (743 bp), and the sequences of M. kanzakii sp. n. of SSU 18S rDNA (867 bp) and of the D2/D3 domain of LSU 28S rDNA (792 bp) were submitted to GenBank with accession numbers MW648792, MW763076 and MW649133, MW763063, respectively. The sequences of both gene markers (SSU 18S r DNA and D2A/D3B domain of LSU 28 rDNA) were aligned along with published data of the orthologous loci in 39 and 40 closely related taxa, resulting in data matrices containing 810 and 625 bp, respectively, in MEGAX (Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Stecher, Li, Knyaz and Tamura2018) using the clustal W alignment tool (Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Gibson, Plewniak, Jeanmougin and Higgins1997). The ambiguously aligned sequences were removed using the online version of Gblocks 0.91b (Castresana, Reference Castresana2000). The phylogenetic trees were constructed based on the Bayesian inference method using MrBayes version 3.1.2 (Huelsenbeck & Ronquist, Reference Huelsenbeck and Ronquist2001). For both gene markers, the best models were selected under the Akaike Information Criterion model selection criterion using jModelTest version 2.1.3 (Darriba et al., Reference Darriba, Taboada, Doallo and Posada2012) and online version PhyML 3.0. (Guindon et al., Reference Guindon, Dufayard, Lefort, Anisimova, Hordijk and Gascuel2010). The General Time Reversible (GTR) substitution model with a proportion of invariable sites and gamma-distribution rate variation across sites (GTR + I + G) was used for the evolutionary history. The Akaike-supported model, log-likelihood, state frequency of nucleotides, substitution rate across the sites, proportions of invariable sites, the shape parameter of gamma distribution and rate of variation were examined during phylogenetic analysis. The obtained values of the above parameters for SSU 18S rDNA were as follows: log-likelihood (InL = −4011.5409); state frequency of nucleotides (freqA = 0.2601, freqC = 0.1941, freqG = 0.2678, freqT = 0.2780); substitution rate across the sites (R(AC) = 0.2780, R(AG) = 2.8799, R(AT) = 1.8629, R(CG) = 0.4506, R(CT) = 5.3035, R(GT) = 1.0000); proportions of invariable sites (pinvar = 0.5220); gamma distribution and rate of variation (shape = 0.5540). The values for the D2A/D3B domain of LSU 28S rDNA were as follows: InL = −5543.8754; freqA = 0.1917, freqC = 0.2078, freqG = 0.3377, freqT = 0.2628; R(AC) = 0.6254, R(AG) = 2.3044, R(AT) = 1.3489, R(CG) = 0.4841, R(CT) = 6.2527, R(GT) = 1.0000; pinvar = 0.2930; gamma shape = 0.7830. The analysis was run with the Markov Chain Monte Carlo for 4 × 106 generations. ‘Burn-in’ samples were discarded at every 1000 generations, and a consensus tree with a minimum 50% majority rule was used for analysis. Pseudodiplogasteroides compositus Körner, 1954 and Pseudodiplogasteroides sp. were taken as an outgroup for the two markers. The trees were visualized, edited and saved with FigTree 1.4.0 (Rambaut, Reference Rambaut2014).

Percent similarity and genetic divergence

The percent similarity among the sequences of selected species of Mononchoides (tables 1 and 2) was estimated using the online Sequence Identity And Similarity (SIAS) tool (http://imed.med.ucm.es/Tools/sias.html).

Table 1. Percent similarity within the species of Mononchoides based on SSU 18S rDNA sequences along with information on the habitat/insect host and country-wise location (similarity statistics are as follows: minimum = 91.78; maximum = 100; mean = 95.19; standard deviation = 2.70).

Table 2. Percent similarity within the species of Mononchoides based on the D2/D3 domain of LSU 28S rDNA sequences along with information on the habitat/insect host and country-wise location (similarity statistics are as follows: minimum = 74.43; maximum = 100; mean = 84.63; standard deviation = 9.35).

The number of base differences per sequence (genetic divergence) of the selected markers in species Mononchoides (tables 3 and 4) was computed using the Transition + Transversion substitution model with gamma distribution rate and invariant sites, and evaluated with 1000 bootstrap replicates. The gaps and missing data were eliminated using the complete deletion option. The divergence analyses with 531 positions, including parts of both loci in the final dataset, were performed in MEGAX.

Table 3. Base differences per nucleotide sequence of SSU 18S rDNA in selected species of Mononchoides. The values below diagonal indicate the base differences, while those above the diagonal (in blue) indicate standard errors.

Table 4. Base differences per nucleotide sequence of the D2/D3 domain of LSU 28S rDNA in selected species of Mononchoides. The values below the diagonal indicate the base differences, while those above the diagonal (in blue) indicate standard errors.

Results

Systematics

Class: Chromadorea Inglis, 1983

Order: Rhabditida Chitwood, 1933

Suborder: Rhabditina Chitwood, 1933

Infraorder: Diplogastromorpha De Ley & Blaxter, 2002

Superfamily: Diplogastroidea Micoletzky, 1922

Family: Diplogastridae Micoletzky, 1922

Genus: Mononchoides Rahm, 1928

Diagnosis

Body cylindrical, straight or slightly ventrally arcuate upon fixation. Cuticle punctated or non-punctated, with or without longitudinal ridges and fine transverse striations. Labial sensilla papilliform or setiform. Stoma divided into two parts; anterior broader and posterior narrow, tubular part. Cheilostom divided into several plates with number variable in different species. Apex of each plate bifurcated, extending outside the oral aperture. Stegostom anisotopic and anisomorphic. Metastegostomal wall bearing a moderate- to large-sized, movable claw-like or thorn-shaped dorsal tooth and more or less similar right subventral tooth; left-subventral wall armed with serrated plate or bearing variable number, shape and size of denticles; telostegostom long. Pharynx divided into a long slender procorpus; an oval highly muscular metacorpus; a short, narrow isthmus; and an elongated to pyriform basal bulb. Secretory–excretory duct opening posterior to nerve ring. Female reproductive system didelphic, amphidelphic. Vaginal glands often discernible. Vulva a small ovoid aperture situated equatorially. Spicules free, slender, more or less ventrally arcuate, with or without distinct neck and head. Gubernaculum proximally attenuated. Genital papillae nine pairs with three pre cloacal and six post cloacal pairs. Phasmids located posterior to anus. Tail long, conoid to filiform.

Type species. Mononchoides longicauda Rahm, 1928

Other species

Mononchoides adjunctus Massey, 1966

Mononchoides albus (Bastian, 1865) Sudhaus & Fürst von Lieven, 2003

Mononchoides americanus (Steiner, 1930) Chitwood, 1937

Mononchoides andersoni Ebsary, 1986

Mononchoides andrassyi (Timm, 1961) Gagarin, 1998

Mononchoides aphodii (Bovien, 1937) Sudhaus & Fürst von Lieven, 2003

Mononchoides aquaticum Gagarin & Nguyen Thanh, 2006

Mononchoides armatus (Hofmänner, 1913) Gagarin, 1998

Mononchoides asiaticus Gagarin, 2001

Mononchoides bicornis (Rahm, 1928) Andrássy, 1984

Mononchoides bollingeri Goodrich, Hechler and Taylor, 1968

Mononchoides changi Goodrich, Hechler and Taylor, 1968

Mononchoides composticola Steel, Moens, Scholaert, Boshoff, Houthoofd and Bert, 2011

Mononchoides elegans (Weingärtner, 1955) Goodey, 1963

Mononchoides filicaudatus (Allgén, 1947) Sudhaus & Fürst von Lieven, 2003

Mononchoides flagellicaudatus (Andrássy, 1962) Zullini, 1981

Mononchoides fortidens (Schuurmans Stekhoven, 1951) Taylor & Hechler, 1966

Mononchoides gaugleri Siddiqi, Bilgrami and Tabassum, 2004

Mononchoides gracilis Dassonville & Heyns, 1984

Mononchoides intermedius Gagarin, 1993

Mononchoides isolae (Meyl, 1953) Goodey, 1963

Mononchoides iranicus Atighi, Pourjam, Kanzaki, Giblin-Davis, De Ley, Mundo-Ocampo, and Pedram, 2013

Mononchoides latigubernaculum Yousuf, Mahamood, Mumtaz and Ahmad, 2014

Mononchoides leptospiculum (Weingärtner, 1955) Goodey, 1963

Mononchoides linocercus (Völk, 1950) Andrássy, 1984

Mononchoides longicauda Rahm, 1928

Mononchoides longicaudatus (Khera, 1965) Andrássy, 1984

Mononchoides macrospiculum Troccoli, Oreste, Tarasco, Fanelli and De Luca, 2015

Mononchoides megaonchus Mahamood, Ahmad and Shah, 2007

Mononchoides microstomus Gagarin, 1998

Mononchoides paesleri (Gunhold, 1952) Sudhaus & Fürst von Lieven, 2003

Mononchoides paramonovi Gagarin, 1998

Mononchoides parastriatus (Paesler, 1946) Andrássy, 1984

Mononchoides piracicabensis (Rahm, 1928) Goodey, 1963

Mononchoides przhiboroi Tsalolikhin, 2009

Mononchoides pulcher Zullini, 1981

Mononchoides pulcherrimus Andrássy, 1987

Mononchoides pylophilus (Weingärtner, 1955) Goodey, 1963

Mononchoides rahmi (Goodey, 1951) Sudhaus & Fürst von Lieven, 2003

Mononchoides rhabdoderma (Völk, 1950) Calaway & Tarjan, 1973

Mononchoides ruffoi Zullini, 1981

Mononchoides schwemmlei (Sachs, 1950) Gagarin, 1998

Mononchoides splendidus (Körner, 1954) Goodey, 1963

Mononchoides striatulus (Fuchs, 1933) Goodey, 1963

Mononchoides striatus (Bütschli, 1876) Goodey, 1963

Mononchoides subamericanus (Van der Linde, 1938) Calaway & Tarjan, 1973

Mononchoides subdentatus (Gunhold, 1952) Andrássy, 1984

Mononchoides tenuispiculum Yousuf, Mahamood, Mumtaz and Ahmad, 2014

Mononchoides trichiuroides (Schneider, 1937) Goodey, 1963

Mononchoides trichuris (Cobb, 1893) Andrássy, 1984

Mononchoides vulgaris Gagarin, 2000

Mononchoides kanzakii sp. n.

Material examined

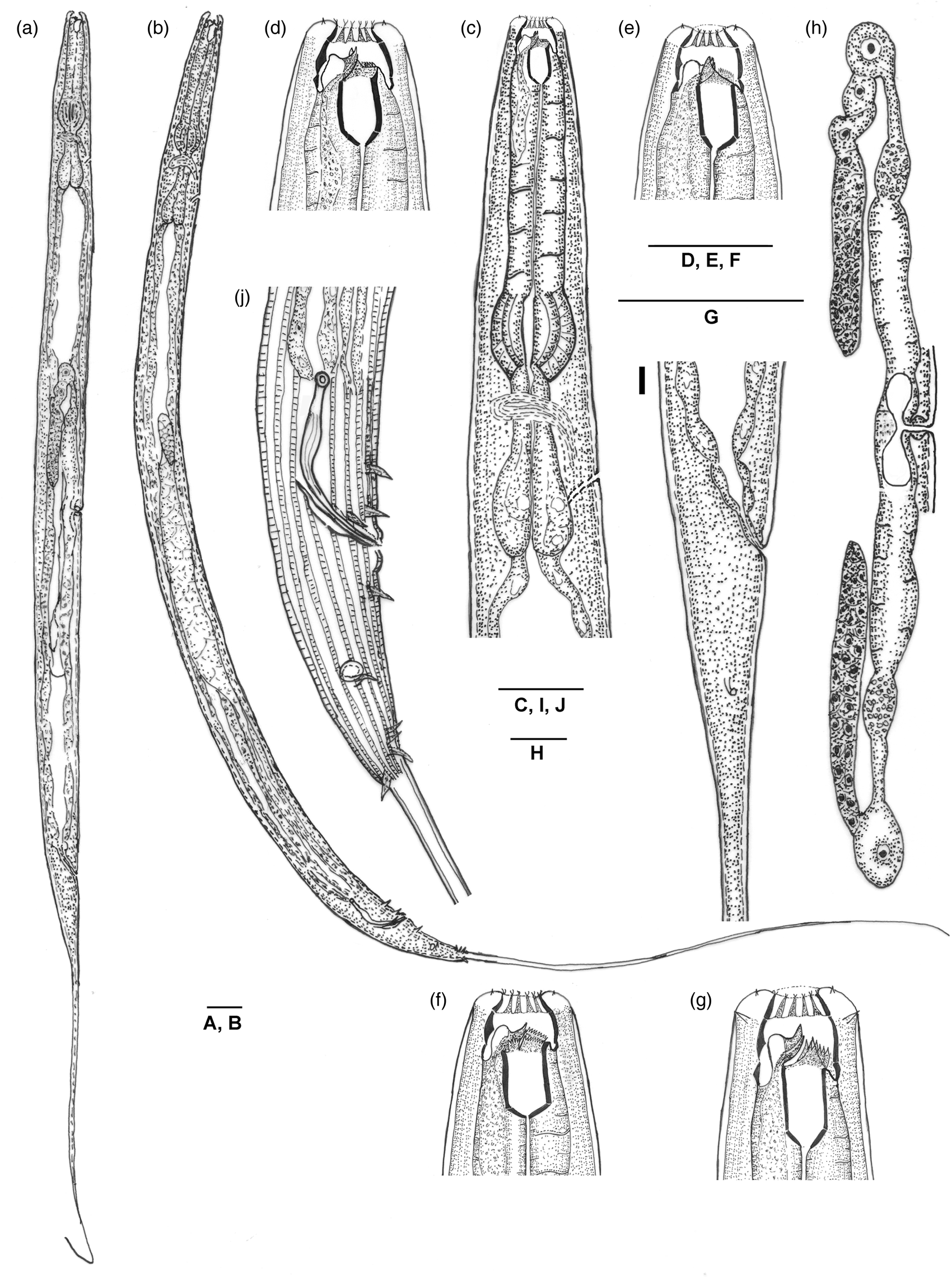

The type material representing 15 females and 15 males in good condition was examined (figs 1–4).

Fig. 1. Line drawings of Mononchoides kanzakii sp. n. (a) Entire female. (b) Entire male. (c) Female pharyngeal region. (d–f) Female anterior end, showing dorsal and right subventral teeth, and left subventral plates with denticles, respectively. (g) Male anterior end. (h) Female reproductive system. (i) Female posterior region. (j) Male posterior region. Scale bars: 25 μm.

Fig. 2. Light micrograph of Mononchoides kanzakii sp. n. (female). (a–c) Anterior end, showing dorsal tooth with a prominent pharyngeal gland duct and left subventral plates with denticles, respectively. (d) Discontinued ridges at anterior end. (e) Ridges at mid-body. (f) Posterior pharyngeal region. (g) Dumbbell-shaped uterine sac. (h) Posterior genital branch. (i) Posterior region. Scale bars: 10 μm.

Fig. 3. Light micrograph of Mononchoides kanzakii sp. n. (male). (a, b) Anterior end showing dorsal tooth with a prominent pharyngeal gland duct, right subventral tooth and left subventral plates with denticles, respectively. (c) Posterior pharyngeal region. (d) Genital branch with reflexed part of testes. (e–h) Cloacal region showing spicule and gubernaculum. (i) Cloacal region showing arrangement of genital sensilla. Scale bars: 10 μm.

Fig. 4. Scanning electron micrographs of Mononchoides kanzakii sp. n. (a, b) En face view (female), (a) Closed oral aperture, (b) Open oral aperture. (c) Anterior end (male). (d) Compact ridges in anterior body region. (e) Spaced ridges in posterior body region. (f) Posterior region (female). (g) Posterior region (male). Scale bars: 5 μm.

Measurements

For measurements, see table 5.

Table 5. Morphometric data of Mononchoides kanzakii sp. n. Measurements are in μm and in the form: mean ± standard deviation (range).

a, total body length/body diameter; b, total body length/pharynx length; c, total body length/tail length; c’, tail length/anal body diameter; V/T, vulva percent with respect to total body length/male gonad percent with respect to total body length; G1, female anterior genital branch percent with respect to total body length; G2, female posterior genital branch percent with respect to total body length.

Description

Adult. Body long, straight upon fixation, and slightly arcuate in males. Cuticle with prominent longitudinal ridges c. 28–32 in number at mid-body and fewer in number at anterior and posterior region; discontinuous at the level of stoma. Lip region continuous with the adjoining body. Lips six, amalgamated, each with a small papilliform sensilla. Amphidial aperture faintly discernible under LM, located just posterior to metastegostomal armature. Stoma longer than wide, differentiated into cheilo-, gymno- and stegostom. Cheilostom divided into 16 to 18 conspicuous plates, outwardly directed and bifurcated apically, and often referred as cheilostomal filaments or rugae. Gymnostom anisomorphic and anisotopic, with dorsal wall relatively thicker and shorter than subventral walls and having a denticle-like protrusion. Stegostom anisomorphic and anisotopic, differentiated into broader pro- meso- and metastegostom and a narrower tubular telostegostom. Metastegostom armed with a robust thorn-shaped dorsal tooth with prominent subapical opening of dorsal gland duct; a flattened, triangular, curved right subventral tooth, almost equal in size to dorsal one. The left subventral sector in females armed with a denticulate ridge comprising a row of 12–14 fine denticles separated by a smaller group of five denticles by a groove vs. a denticulate ridge of 6–8 relatively conspicuous denticles in males; telostegostom c. 1.4–1.5 times longer than wide, or 13–15 μm × 9–10 μm in dimension. Pharynx differentiated into a long slender procorpus of about 93–105 μm in length; a rounded to oval, highly muscular metacorpus of c. 28–32 μm × 28–34 μm dimension and a short, narrow isthmus expanding into an elongated basal bulb of 30–38 μm × 23–30 μm dimension. Nerve ring encircling middle of isthmus at c. 70–72% of total pharyngeal length. Secretory–excretory duct opening located posterior to nerve ring at c. 81–83% of total pharyngeal length from anterior end. Intestine granular with wide lumen. Cardia conoid, embedded into intestine. Phasmids located at 42–50 μm or 1.5–1.6 times anal body diameter posterior to anus. Tail long, filiform, constituting c. 33–39% of total body length.

Female. Reproductive system didelphic, amphidelphic. Ovaries reflexed, with anterior one on the right and posterior on the left side of intestine. The distal tip of each ovary extending up to the corresponding uterus but does not reach vulva. Oocytes with prominent nuclei, arranged in three rows in germinal and two rows zone. A large oocyte with distinct nucleus present at proximal end of ovary. Oviduct conspicuous, connected with ovary subterminally, expanding into an ovoid spermatheca, the latter slightly shorter than oviduct, containing small-sized, rounded sperms. Uterus spacious without marked differentiation of glandular and muscular parts, approximately 2–3 times longer than oviduct and slightly separated from spermatheca; dumbbell-shaped uterine sac connecting distal parts of both uteri. Vagina muscular, with narrow lumen. Vulva median, reduced with small opening, barely visible under LM.

Male. General morphology similar to female except for slightly smaller and more slender body, arcuate at posterior region after fixation; four cephalic setae, present in addition to the six labial setae. Testis monorchic laterally reflexed. Cloacal rim present, cloacal lips conspicuous with a triangular process on the upper cloacal lip. Spicules ridged, obtuse with rounded capitulum, conspicuously long neck, proximally bulging ventral arm, tapering distally and ending into a sharp, thin tip. Gubernaculum approximately half of spicule length or slightly more than half, cuticularized and narrow proximally and distally with a relatively wider central part. Genital sensilla setose, nine pairs; three pre cloacal and six post cloacal pairs arranged in v1, v2, v3d/v4, Ph, ad, v5–7, pd in configurations in addition to two pairs of minute pericloacal papillae. v1 subventral, located at one anal body diam. anterior to cloacal opening; v2 subventral, located just anterior to cloacal opening; v3d lateral, located at the level of upper cloacal lip; v4 subventral, located slightly posterior to the lower cloacal lip; ad situated laterally at about one anal body diam. posterior to cloacal opening. Phasmids located just anterior to ad at about one or less than one anal body diameter; v5–7 grouped together with v5 and v6 trifid, relatively shorter than v7; pd situated dorsally, located at just posterior to the group of v5–7.

Type habitat and locality

Mononchoides kanzakii sp. n. was collected from manure, Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh, India, at coordinates 26°25ʹ34″N, 80°23ʹ49″E.

Type material

Holotype female, ten paratype females and ten paratype males on slides M. kanzakii sp. n. KNP/SERB/M30/1–10 deposited in Nematode Research Laboratory, Department of Zoology, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh, India.

Etymology

The species name is given to honour Dr Natsumi Kanzaki for his important contribution to the taxonomy of diplogastrids.

Diagnosis and relationships

The new species showed a combination of characters such as cuticle with prominent ridges, discontinuous at level of the stoma; amphidial apertures inconspicuous; cheilostom divided into 16 to 18 conspicuous plates, bifurcated apically; gymnostom anisotopic and anisomorphic with dorsal walls relatively smaller and thicker than subventral walls and having a denticle-like protrusion in females and subventral walls longer than dorsal ones in males; metastegostom armed with thorn-shaped dorsal tooth; a flattened, claw-like right subventral tooth, and left subventral sector in females armed with a denticulate ridge comprising a row of 12–14 fine denticles separated by a smaller group of five denticles by a groove; males with a flattened pyramidal to curved right subventral tooth and denticulate ridge in the left subventral sector with 6–8 relatively conspicuous denticles; telostegostom c. 1.4–1.5 times longer than wide; cloacal lips with a distinct rim. Spicules ridged, obtuse with rounded capitulum, conspicuously long neck with a sharp, pointed distal tip; gubernaculum approximately half of the spicule length with a cuticularized, proximal and distal extension equal in length, about half of the wider part of gubernaculum; genital sensilla setose, nine pairs: three precloacal and six postcloacals, arranged in v1, v2, v3d/v4, Ph, ad, v5–7, pd in configurations; phasmids located just anterior to ad; v5–7 grouped together with v5 and v6 trifid, relatively shorter than v7 and pd located just posterior to the group of v5–7.

The new species comes close to M. changi Goodrich et al., 1968 in most morphometric and morphological characters but differs in left subventral sector having two groups, the first containing 12–14 (vs. 32) serrations/denticles and the second group having 5–8 denticles of unequal size (vs. five denticles of about equal shape and size); relatively shorter corpus (93–105 μm vs. 107–125 μm in females and 70–82 μm vs. 100–105 μm in males); phasmidial aperture located at the level or just anterior to the ad genital sensilla (vs. in between the ad genital sensilla and the group of v5–7); testes without lobed (vs. with lobed) distal end; gubernaculum with equal length of attenuated distal and proximal extension (vs. distal extension shorter than proximal one) in M. changi Goodrich et al. (1968).

Mononchoides kanzakii sp. n. differs from M. macrospiculum Troccoli et al., 2015 in having cuticle at the level of the stoma with discontinuous ridges (vs. tessellated punctations); amphidial aperture inconspicuous (vs. conspicuous); telostegostom (1.4–1.5 vs. 2.5) times longer than wide; pharyngeal corpus (3.2–3.3 vs. 3.4–4.6) times metacorpus length; cloacal rim present (vs. absent); gubernaculum (53–56% vs. 60%) of total spicule length; distal attenuated extension about half of (vs. equal to) the wider part and rectum equal to (vs. 1.6–1.7 times to anal body diameter in M. macrospiculum apud Troccoli et al. (2015)).

The new species differs from M. armatus (Hofmänner, 1913) Gagarin, 1998 in having larger (1423–1619 μm vs. 900–1300 μm) body size, greater b (7.2–8.8 vs. 3.7–4.5) and c′ (16.2–19.7 vs. 7–8), values and smaller c values (2.6–3.1 vs. 4.8–8.0 in M. armatus apud Gagarin (1998)).

Mononchoides kanzakii sp. n. differs from M. latigubernaculum Yousuf et al., 2014 in having relatively larger (1423–1619 μm vs. 916–1361 μm) females; cuticle at level of stoma with discontinuous ridges (vs. punctated); left subventral sector armed with a denticulate ridge with denticles in two groups (based on observations of the original specimens of M. latigubernaculum) (12–14 + 5 vs. 6–7 + 6–7); greater anal body diameter (28–32 μm vs. 15–25 μm) and rectum length (27–35 μm vs. 18–27 μm) in males; cloacal rim present with a triangular process on upper cloacal lip (vs. absent); gubernaculum unkeeled (vs. keeled) with both proximal and distal ends having (vs. only distal) attenuated extension in M. latigubernaculum apud Yousuf et al., 2014.

Mononchoides kanzakii sp. n. differs from M. tenuispiculum Yousuf et al., 2014 by large-sized (1423–1619 μm vs. 958–1117 μm) females having wider (18–20 μm vs. 14–15 μm) lip region; longer (25–27 μm vs. 15–19 μm) stoma with telostegostomal part narrower (1.5–1.8 vs. 1.0–1.2 times longer than wide); distal parts of ovaries not reaching vulva (vs. distal parts mostly reaching vulva or crossing each other); larger spicule (45–50 μm vs. 31–36 μm); gubernaculum larger (24–28 μm vs. 14–18 μm), covering (53–56% vs. 23–50%) of total spicule length, proximally attenuated (vs. notched in M. tenuispiculum apud Yousuf et al., Reference Yousuf, Mahamood, Mumtaz and Ahmad2014).

The new species differs from M. composticola Steel et al., 2011 in having larger (1423–1619 μm vs. 810–1150 μm) females; cuticular ridges conspicuous with disruption (vs. low to compressed ridges forming corncob-like pattern) at anterior level of stoma; telostegostom wider (1.5–1.8 vs. 2.5–2.8 times longer than wide); excretory pore in the isthmus region (vs. in region of basal bulb); ovaries relatively smaller with distal parts not reaching vulva (vs. reaching vulva or often extending beyond); cloacal rim present (vs. absent); gubernaculum dissimilar in morphology, covering (53–56% vs. 34–36%) of total spicule length with attenuated proximal end as long as distal extensions equal-sized (vs. proximal extension shorter than distal one and middle part of even thickness (vs. wider proximally in M. composticola apud Steel et al., Reference Steel, Moens, Scholaert, Boshoff, Houthoofd and Bert2011).

The new species differs from M. iranicus Atighi et al., 2013 in having a larger body size (1423–1619 μm vs. 851–1205 μm); greater b (7.2–8.8 vs. 4.8–6.3) and c′ (16.2–19.7 vs. 8.4–12.8) values; cuticle at the level of stoma with conspicuous but discontinuous ridges (vs. low to compressed ridges forming corncob-like pattern); amphidial aperture indiscernible or faintly discernible (vs. conspicuous); relatively shorter (25–27 vs. 30–35) stoma with telostegostom short, wide (vs. long, slender) about (1.5–1.8 vs. 2.4–3.5) times longer than wide; cloacal rim present (vs. absent); gubernaculum (53–56% vs. 37–40%) of total spicule length with attenuated proximal as long as distal extensions equal-sized (vs. only distal extension present in M. iranicus apud Atighi et al., 2013).

Mononchoides composticola Steel et al., 2011

Material examined

The voucher material representing ten females and six males in good condition was examined (figs 5–8).

Fig. 5. Line drawings of Mononchoides composticola Steel et al., 2011. (a) Entire female. (b) Entire male. (c, d) Female anterior end, showing dorsal and right subventral teeth, and left subventral plates with denticles, respectively. (e) Male anterior end. (f) Female pharyngeal region. (g) Female reproductive system. (h) Female posterior region. (i) Male posterior region. Scale bars: 25 μm.

Fig. 6. Light micrograph of Mononchoides composticola Steel et al., 2011 (female). (a–f) Anterior end showing (a) Dorsal tooth with a prominent pharyngeal gland duct, (b) Right subventral tooth, (c) Dorsal and right subventral teeth, (d) Apical end of dorsal and right subventral teeth, (e) Dorsal tooth, (f) left subventral plates with denticles. (g) Anterior pharyngeal region. (h) Posterior pharyngeal region. (i) Anterior and (j) posterior genital branch. (k) Vulval region. (l) Posterior region. (m, n) Ridges at mid-body. Scale bars: 10 μm.

Fig. 7. Light micrograph of Mononchoides composticola Steel et al., 2011 (male). (a–c) Anterior end showing dorsal tooth with a prominent pharyngeal gland duct (a), right subventral teeth (b) and left subventral plates with denticles (c). (d) Neck region with cuticular punctation, amphidial aperture and cephalic sensilla. (e) Posterior pharyngeal region. (f, h) Posterior region showing spicule (f) and arrangement of genital sensilla (h). (g) Cloacal region showing gubernaculum. Scale bars: 10 μm.

Fig. 8. Scanning electron micrographs of Mononchoides composticola Steel et al., 2011. (a, d) Anterior region (enface view). (b, c) Anterior end showing cuticular pattern and ridges. (e) Body region showing secretory–excretory pore. (f) Vulval region. (g) Posterior region (female) showing discontinuous ridges and crescent-shaped anal opening. (h) Cloacal region (male). Scale bars: 5 μm.

Measurements

For measurements, see table 6.

Table 6. Morphometric data of populations of Mononchoides composticola Steel, Moens, Scholaert, Boshoff, Houthoofd and Bert, 2011. Measurements are in μm and in the form: mean ± standard deviation (range).

a, total body length/body diameter; b, total body length/pharynx length; c, total body length/tail length; c′, tail length/anal body diameter; V/T, vulva percent with respect to total body length/male gonad percent with respect to total body length; G1, female anterior genital branch percent with respect to total body length; G2, female posterior genital branch percent with respect to total body length.

Description

Adult. Body long, straight to slightly arcuate ventrally upon fixation, more in males. Cuticle with fine transverse striations and conspicuous longitudinal ridges c. 24–28 in number at mid-body. Cuticular ridges less conspicuous, compressed forming corncob-like pattern in the stomal region. Lip region continuous with the adjoining body. Lips six, amalgamated, each with small papilliform sensilla. Amphidial aperture small, elliptical located at the level of cheilostomal base. Stoma longer than wide. Cheilostom anisomorphic, with the relatively thicker and highly cuticularized dorsal wall than sub ventral ones, having a small denticle, divided into 14–16 cheilostomal plates outwardly projecting into cheilostomal filaments bifurcated apically. Gymnostom anisotopic with dorsal wall shorter than sub ventral walls. Stegostom anisomorphic and anisotopic, divided into a broader part of pro-, meso- and metastegostom and a narrow tubular telostegostom. Metastegostom armed with a robust claw-like dorsal tooth with subapical opening of dorsal gland duct, a flattened, curved to pyramid-like right sub ventral tooth, as almost equal to dorsal one and a denticulate ridge of seven denticles arranged in two groups, telostegostom c. two times longer than wide or 13–15 μm × 7 μm in dimension. Pharynx divided into a long, slender procorpus, expanding posteriorly into oval highly muscular metacorpus of 24–30 μm × 22–28 μm dimension and a short, narrow isthmus expanded into an elongated pyriform basal bulb of 24–33 μm × 19–24 μm in dimension. Nerve ring encircling the anterior part of isthmus at c. 68–69% of total pharyngeal length. Secretory–excretory duct located posterior to nerve ring at c. 71–72% of total pharyngeal length. Intestine granular with wide lumen. Cardia conoid. Phasmids located 20–25 μm posterior to the anus. Tail long, filiform, constituting c. 43–49% of total body length.

Female. Reproductive system didelphic, amphidelphic. Ovaries reflexed, usually extending up to vulva with anterior branch on the right, posterior branch on the left side of the intestine. Oocytes with prominent nuclei, arranged in three in distal part followed by two rows proximally. A large oocyte with distinct nucleus at the proximal end of ovary present. Oviduct very short, expanding into a globular, relatively large-sized spermatheca, containing a cluster of small-sized, rounded, numerous sperms. Uterus spacious without marked differentiation of glandular and muscular parts, uterine pouches inconspicuous or faintly visible. Vagina muscular, with narrow lumen. Vulva reduced with small opening located along a ridge, barely visible under LM due to small circular pore. Vulval lips weakly cuticularized, not protruded.

Male. General morphology similar to female except slightly smaller and slender body as well as more arcuate at posterior region after fixation and with four additional cephalic setae. Testis monorchic laterally reflexed. Spicules free, arcuate with knobbed capitulum, conspicuously long neck, followed by proximally bulging ventral arm tapering towards a sharp, thin distal end. Gubernaculum less than a half of the spicule length with small distal lateral sleeve and a cuticularized and attenuated proximal extension. Genital sensilla setose, nine pairs; three pre cloacal and six post cloacal pairs arranged in v1, v2, v3d/v4, ad, Ph, v5–7, pd in configurations. v1 subventral, located at one anal body diam. anterior to cloacal opening; v2 subventral, located just anterior to cloacal opening; v3d lateral, located at the level of upper lip; v4 subventral, located at just behind the lower cloacal lip; ad lateral, one anal body diam. posterior to cloacal opening or just anterior to phasmidial aperture. Phasmids located in between v4 and the group of v5–7; genital sensilla v6 composed of three fine sensilla of which two appear more conspicuous; pd dorsal, located at the level of v7.

Habitat and locality

The present populations (table 6) of M. composticola Steel et al., 2011 was extracted from a soil sample from the shore of the Ganga River, Jajmua, Kanpur, at geographical coordinates 26°26ʹ13″N, 80°24ʹ11″E; from a tree tunnel, Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh, at geographical coordinates 27°55ʹ44″N, 78°4ʹ35″E and isolated from O. cinctus (Fabricius, 1775) (Scarabaeidae), collected from district Balrampur, Uttar Pradesh, at geographical coordinates 27°25′28″N, 82°10′57″E.

Voucher materials

Ten paratype females and six paratype males on slides M. composticola NIT/MON/1–8 were deposited in Nematode Research Laboratory, Department of Zoology, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh, India.

Emended diagnosis

Mononchoides composticola Steel et al., 2011 is characterized by cuticle with prominent, 24–28 longitudinal ridges; stoma longer than wide; cheilostom anisomorphic, with 14–16 plates projecting into cheilostomal filaments with bifurcated apical end; dorsal wall relatively much cuticularized; gymnostom anisotopic with dorsal wall shorter than subventrals; stegostom anisomorphic and anisotopic; dorsal tooth claw-like with a prominent duct opening; right subventral tooth flattened, curved or pyramidal, approximately equal to dorsal tooth; left subventral wall with denticulate ridge with seven denticles arranged in two groups; males with spicules having knobbed capitulum, long neck followed by protruded ventral arm tapering into a sharp, thin distal end; gubernaculum with small lateral distal sleeve and a cuticularized attenuated proximally hooked extension and nine pairs of setose genital papillae with v6 represents three smaller sensilla.

Remarks

The phoretic juveniles and adults (50–60 in number) of the present population of M. composticola Steel et al., 2011 were found to be associated with the mouthparts of the dung beetle (O. cinctus). Insects were collected from 1–2-day-old cow dung. During the excision of beetle, several phoretic juveniles and adults were observed actively moving on the head region. Within 3–4 days, their number increased in the culture with a 1:1 sex ratio. The dioecious females were observed to be oviparous, with most embryonation occurring outside the female body. Gravid females generally laid single- to two-celled eggs. Uterus accommodated usually 2–4 oval, smooth-shelled eggs measuring 65–70 μm × 25–30 μm in dimension.

Mononchoides composticola Steel et al., 2011 is generally found in organically enriched habitats comprising compost and manure, and is associated with insects by phoresy. The original population was recorded from Belgium. The present population conforms to the original population of M. composticola Steel et al., 2011 barring a few minor differences, such as narrower lip region (12–15 μm vs. 16–22 μm) and slightly larger gubernaculum (20–24 μm vs. 14–18 μm). Steel et al. (Reference Steel, Moens, Scholaert, Boshoff, Houthoofd and Bert2011) highlighted the differences between M. composticola and Mononchoides sp. described by Mahamood et al. (Reference Mahamood, Ahmad and Shah2007); however, on comparing the present population with the former two populations (M. composticola and Mononchoides sp.), an overlap in the morphometric characters has been observed – namely, female tail (550–620 μm vs. 391–550 μm vs. 330–475 μm), male tail (395–450 μm vs. 304–548 vs. 204–369 μm), female basal bulb (24–30 μm vs. 19–32 μm vs. 16–20 μm), shorter neck in the male (125–139 μm vs. 97–113 μm vs. 118–143 μm), shorter and smaller spicules and gubernaculum (respectively, 35–40 vs. 30–38 μm vs. 37–43 μm, and 16–19 vs. μm 10–14 vs. 14–22 μm). An important feature – that is, the structure of the sixth sub ventral genital sensilla in males – in the present population resembles that found in M. composticola Steel et al. (2011). The population described by Mahamood et al. (Reference Mahamood, Ahmad and Shah2007) did not reveal the intricate nature of v6 genital sensilla as observed in M. composticola, probably due to oversight or due to low resolution of the employed light microscope to differentiate a structure of a size less than 1 μm. Also, the position of excretory pore in the three forms coincides (i.e. located in isthmus region); and the distal part of ovary/ovaries extends up to vulva or beyond in the present population, M. composticola Steel et al., 2011 and Mononchoides sp. Mahamood et al. (2007). Therefore, we believe that the correct species identity of the latter seems to be M. composticola, like our own populations described above. In another species of Mononchoides (M. fortidens), v6 was reported to be bifid in nature (Tahseen et al., Reference Tahseen, Ahmad, Bilgrami and Ahmad1992).

Discussion

Habitat preferences

The genus Mononchoides is a highly advanced group, placed as sister clade next to Tylopharynx de Man, 1876 within the family Diplogastridae Micoletzky, 1922 in morphology-based cladograms (Fürst von Lieven & Sudhaus, Reference Fürst von Lieven and Sudhaus2000) and in the molecular analyses of Steel et al. (Reference Steel, Moens, Scholaert, Boshoff, Houthoofd and Bert2011) and Troccoli et al. (Reference Troccoli, Oreste, Tarasco, Fanelli and De Luca2015). They are largely terrestrial, generally found in organically enriched habitats, such as compost, dung, manure, decaying woods, leaves, etc. (Steel et al., Reference Steel, Moens, Scholaert, Boshoff, Houthoofd and Bert2011; Yousuf et al., Reference Yousuf, Mahamood, Mumtaz and Ahmad2014; Troccoli et al., Reference Troccoli, Oreste, Tarasco, Fanelli and De Luca2015). However, some of them are associated with several soil-dwelling insects by phoresy to disperse in search of favourable environments. The species M. adjunctus Massey, 1966, M. aphodii (Bovien, 1937) Sudhaus & Fürst von Lieven, Reference Sudhaus and Fürst Von Lieven2003 and M. macrospiculum Troccoli et al., 2015, demonstrating endophoresy, were recorded from the body cavity/haemocoel of insects (Bovien, Reference Bovien1937; Massey, Reference Massey1966, Reference Massey1974; Poinar et al., Reference Poinar, Triggiani and Merritt1976; Troccoli et al., Reference Troccoli, Oreste, Tarasco, Fanelli and De Luca2015); however, the new species M. kanzakii was found associated with the mouth part of the insect showing ectophoresy. Nearly 6–7 species comprising 12% of the representatives of the genus are known to be associated with insects (Mahboob & Tahseen, Reference Mahboob and Tahseen2021).

Differential characteristics of the genus

The genus differs from the other genera of Diplogastridae in having prominent longitudinal ridges, stoma divided into the anteriorly wide and posteriorly tubular part, cheilostom divided into several narrow plates ending into bifurcated apices, anterior edges of gymnostom usually serrated, with the inner wall bearing a number of denticles; metastegostom with dorsal tooth claw-like having prominent dorsal pharyngeal gland duct and distinct subapical opening, right subventral tooth flattened, conical/pyramidal attached to the anterior edge of telostegostom and a left subventral denticulate plate. The prominent longitudinal ridges are similar to those found in Fictor, with representative species Fictor vorax Goodey, 1929, Fictor suptilis Yousuf & Mahamood, 2017, Fictor longicauda Yousuf & Mahamood, 2017, Fictor platypapillata Mahboob & Tahseen, 2022, etc. However, the genus Mononchoides is distinctly separated from the above-mentioned species of Fictor Paramonov, 1952 in having long, cheilostomal plates with bifurcated apices as well as the long, tubular telostegostom in contrast to relatively short cheilostomatal plates with apices not furcated and short telostegostom present in Fictor Paramonov, 1952. The movable claw-like dorsal tooth with prominent dorsal pharyngeal gland duct and aperture, and a movable claw-like/triangular, flattened or cone-shaped right subventral tooth are homologous in Allodiplogaster Paramonov & Sobolev in Skrjabin Shikobalova et al., 1954, Fictor Paramonov, 1952, Neodiplogaster Cobb, 1924, Micoletzkya Weingärtner, 1955, Koerneria Meyl, 1960, etc. and the right subventral tooth can move directly along with the dorsal tooth but the triangular, flattened/cone-shaped right subventral tooth of Mononchoides differs in its placement as it is attached to the anterior edge of testegostom and its movement indirectly depends on the movement of telostegostom (Fürst von Lieven & Sudhaus, Reference Fürst von Lieven and Sudhaus2000). The shape, size and number of left subventral armatures are not fully resolved due to unavailability of SEM observations in most species and due to the low-resolution LM images. Although the left subventral armature is meagerly known, most of the species have been described based on only serrated plates.

Stomatal morphotypes

A good number of nematode groups of Diplogastridae show two (sometimes even more) stomatal morphs, which appear to be connected due to their ability to survive in adverse conditions such as lack of food resources, overcrowding and resulting competition. Others are primarily monomorphic, having a tubular or narrow stoma and feeding upon the bacteria and other micro-organisms by sucking/ingesting them. In the dimorphic species, in addition to stenostomatous morphs with such a narrow stoma, there also occur individuals with a wider stoma (eurystomatous), having strong armature suitable for predation. However, the monomorphic stoma of the species of Mononchoides with both wide as well as narrow parts and having advanced armature seems to be well equipped for multiple modes of feeding (bacteriophagy, rupturing larger spores/yeast cells and predation). Hence, the species representing one type of stoma may demonstrate predation as the predominant strategy, although a switch over to bacteriophagy can occur when required. It may also depend on the substrate conditions, where nematodes cultured in labs with prey species have restricted nutrient options as compared to those in natural microhabitats with ample diet combinations.

Phylogenetic status

The blast analysis of new species M. kanzakii was conducted in order to analyse its similarity with different taxa of Diplogastromorpha. The blast results of the SSU 18S rDNA sequence showed similarity with 21 genera of Diplogastridae – namely, Allodiplogaster Paramonov & Sobolev in Skrjabin, Shikobalova, Sobolev, Paramonov and Sudarikov, 1954; Butlerius Goodey, 1929; Cutidiplogaster Fürst von Lieven, Uni, Ueda, Barbuto, and Bain, 2011; Diplogastrellus Paramonov, 1952; Diplogasteroides De Man, 1912; Fictor Paramonov, 1952; Koerneria Meyl, 1960; Mehdinema Farooqui, 1967; Mononchoides Rahm, 1928; Mycoletzkya Weingärtner, 1955; Neodiplogaster Cobb, 1924; Oigolaimella Paramonov, 1952; Paroigolaimella Paramonov, 1952; Parapristionchus Kanzaki, Ragsdale, Herrmann, Mayer, Tanaka and Sommer, 2012; Pristionchus Kreis, 1932; Pseudodiplogasteroides Körner, 1954; Rhabditoides Goodey, 1929; Sachsia Meyl, 1960; Teratodiplogaster Kanzaki, Giblin-Davis, Davies, Ye, Center and Thomas, 2009; and Tylopharynx De Man, 1876. However, the blast analysis of the D2/D3 domain of LSU 28S rDNA showed similarity with 19 genera of Diplogastridae – namely, Acrostichus Rahm, 1928; Butlerius Goodey, 1929; Cutidiplogaster Fürst von Lieven et al., 2011; Diplogastrellus Paramonov, 1952; Fictor Paramonov, 1952; Koerneria Meyl, 1960; Levipalatum Ragsdale, Kanzaki and Sommer, 2014; Mononchoides Rahm, 1928; Mycoletzkya Weingärtner, 1955; Myctolaimus Cobb, 1920; Neodiplogaster Cobb, 1924; Paroigolaimella Paramonov, 1952; Parapristionchus Kanzaki et al., 2012; Poikilolaimus Fuchs, 1930; Pristionchus Kreis, 1932; Pseudodiplogastroides Körner, 1954; Rhabditolaimus Fuchs, 1914; Rhabditoides Goodey, 1929; and Sachsia Meyl, 1960. Forty-one taxa of 18S rDNA sequences from 12 closely related genera and 39 taxa of the D2/D3 domain of LSU 28S rDNA sequences from 11 genera under Diplogastridae including Pseudodiplogastroides (as outgroup) were selected for analysis. The selection criterion was based on the homology of the functional morphology of the buccal cavity. The selected taxa have similar feeding behaviour (bacterial feeders and predators in adverse conditions), cheilostom is divided into several plates, movable dorsal and right subventral teeth and dorsal tooth with distinct pharyngeal gland duct opens the subapical region of the dorsal tooth. Interestingly, Koerneria spp. are different in possessing undivided cheilostom (Kanzaki et al., Reference Kanzaki, Ragsdale and Giblin-Davis2014), despite forming the sister group with the taxa having claw-like movable dorsal with subapical gland opening and right subventral teeth. The telostegostomatal apodemes found in all the members of the genus Koerneria present it as a monophyletic group (Fürst Von Lieven & Sudhaus, Reference Fürst von Lieven and Sudhaus2000), although the genus was later split into Koerneria, Allodiplogaster and Anchidiplogaster, and Koerneria with undivided cheilostom was considered as a paraphyletic group (Kanzaki et al., Reference Kanzaki, Ragsdale and Giblin-Davis2014). Pseudodiplogastroides sp. has been taken as an outgroup because of its plesiomorphic characters – namely, distinct converging muscles of the basal bulb and inter-radial rods of the cuticular lining posterior to the grinder of the basal bulb are homologous to rhabditids nematodes; however, these characters are lacking in the other dipogastrid nematodes (Fürst Von Lieven & Sudhaus, Reference Fürst von Lieven and Sudhaus2000). Other characters such as tubular stoma and undivided cheilostom of Pseudodiplogastroides, Diplogastroides, Diplogastrellus, Rhabditolaimus, Acrostichus and Myctolaimus, homologous to the stoma of Rhabditidae, might be considered plesiomorphic characters. In that context, the taxa selected for the phylogenetic analysis, which possess wide buccal cavity and cheilostom divided into several plates, reflect apomorphic traits.

The phylogenetic analyses reveal congruence in the placement of M. kanzakii sp. n. in both trees (figs 9 and 10) and also show similarity with previous analyses, especially in the positions of Mononchoides and Neodiplogaster species, despite different outgroup taken (Kanzaki et al., Reference Kanzaki, Ragsdale and Giblin-Davis2014; Troccoli et al., Reference Troccoli, Oreste, Tarasco, Fanelli and De Luca2015; Kanzaki, Reference Kanzaki2016; Slos et al., Reference Slos, Couvreur and Bert2018; Mahboob and Tahseen, Reference Mahboob and Tahseen2022). The new species M. kanzakii showing a close relationship with Mononchoides sp. (LC210629) with 100% posterior probability values in both analyses might be considered conspecific. The closer identity draws support from the calculated values of percent similarity (tables 1 and 2) and base difference per sequence (tables 3 and 4) when compared with other closely related congeners. The genus Mononchoides appears to be paraphyletic in partial 18S SSU phylogeny, as M. americanus along with other Mononchoides sp. splits with the sister taxon of Neodiplogaster with a 99% posterior probability value; the new species M. kanzakii sp. n. along with M. macrospiculum, M. composticola and M. striatus forms another group with a 91% posterior probability value (fig. 9). However, Mononchoides shows monophyly with all its species reflected in one clade with a 99% posterior probability value in the analysis of the D2/D3 domain of 28S rDNA (fig. 10). Therefore, in order to ascertain the status of the genus Mononchoides, further analyses of complete 18S SSU and 28S LSU as well as mitochondrial DNA cox 1 are needed.

Fig. 9. Bayesian phylogenetic tree inferred based on SSU 18S rDNA in MrBayes version 3.1.2 (Huelsenbeck & Ronquist, Reference Huelsenbeck and Ronquist2001). The tree topology indicated the status of Mononchoides kanzakii sp. n. and the present population of Mononchoides composticola Steel et al., 2011 (marked with red) among the congeners. The evolutionary history was evaluated using the GTR + I + G model. The consensus tree with minimum 50% majority rule was used for analysis. The posterior probability values are reflected at appropriate clades. Scale bar shows the number of substitutions per site.

Fig. 10. Bayesian phylogenetic tree inferred based on the D2/D3 domain of LSU 28S rDNA in MrBayes version 3.1.2 (Huelsenbeck & Ronquist, Reference Huelsenbeck and Ronquist2001). The tree topology indicated the status of Mononchoides kanzakii sp. n. and the present population of Mononchoides composticola Steel et al., 2011 (marked with red) among the congeners. The evolutionary history was evaluated using the GTR + I + G model. The consensus tree with minimum 50% majority rule was used for analysis. The posterior probability values are reflected at appropriate clades. Scale bar shows the number of substitutions per site.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Science and Engineering Research Board (SERB), Government of India, New Delhi, India.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional guides on the care and use of laboratory animals.