Introduction

Functional neurological disorder (FND), also known as conversion disorder, is a syndrome of neurological symptoms without a neuropathological cause (Aybek, Kanaan, & David, Reference Aybek, Kanaan and David2008). For the last century, the dominant model for FND has been the idea that it is caused by psychological trauma (Kanaan, Reference Kanaan2016). In recent years, this model has been challenged, not least because such events are not reported by a substantial proportion of patients with FND. In a meta-analysis of controlled studies, we confirmed the association between stressful life events and FND – that such events occur before the onset of FND twice as commonly as in other psychiatric conditions, and eight times as commonly as in the healthy – although they were not found in 14–68% of cases, depending on how they were assessed (Ludwig et al., Reference Ludwig, Pasman, Nicholson, Aybek, David, Tuck and Stone2018). Though a critical first step, confirming this association does not explain why they are associated.

There are many ways in which life events might contribute to developing FND (Keynejad et al., Reference Keynejad, Frodl, Kanaan, Pariante, Reuber and Nicholson2019). Recent studies have focused on how psychosocial stressors may alter biological markers, which in turn may favour the appearance of FND symptoms. Higher number of life stressors and their subjective impact seems to be associated with higher levels of stress hormones (cortisol and amylase) in FND (Apazoglou, Mazzola, Wegrzyk, Frasca Polara, & Aybek, Reference Apazoglou, Mazzola, Wegrzyk, Frasca Polara and Aybek2017; Bakvis et al., Reference Bakvis, Spinhoven, Giltay, Kuyk, Edelbroek, Zitman and Roelofs2010). Stress, early in life, may alter the genetic expression of proteins involved in the stress response and represent a vulnerability factor for FND (Apazoglou, Adouan, Aubry, Dayer, & Aybek, Reference Apazoglou, Adouan, Aubry, Dayer and Aybek2018). These neuroscience advances suggest that life events may play a causal role in many people with FND, but a step back is needed to better characterise which stressors may be relevant, as stressors predispose to almost all neuropsychiatric disorders, in potentially different ways.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), for example, is only caused by events considered life-threatening (American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5 Task Force, 2013). By contrast, the loss of a spouse, while perhaps just as ‘stressful’, is associated with different pathologies, such as depression (Zisook & Shuchter, Reference Zisook and Shuchter1991). Although there may be factors in the person or their circumstances that contribute to why one person develops depression and another PTSD, some of this difference appears to lie in the nature of the stressors and the aetiological ‘ingredients’ they engender – in these cases, sadness (Keller, Neale, & Kendler, Reference Keller, Neale and Kendler2007) and fear (Ehlers & Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000). Whether there is any degree of such specificity in FND is unknown, although aetiological models for FND would make varying predictions. For example, the Freudian conversion model emphasised events that were experienced as shameful (Breuer & Freud, Reference Breuer, Freud, Freud, Strachey, Freud, Rothgeb and Richards1895); if this were true, we would expect to see more preceding events where shame was more likely, such as sexual trauma (Kizilhan, Steger, & Noll-Hussong, Reference Kizilhan, Steger and Noll-Hussong2020), and fewer of those where shame was less likely to be a feature, such as accidents. An object-relations model, by contrast, would clearly anticipate the antecedent events to be interpersonal events occurring within key relationships (Fairbairn, Reference Fairbairn1954). In addition to the type of events, the models make varying predictions about other characteristics, such as whether they emphasise singular rather than multiple events, or of events closely preceding onset (Keynejad et al., Reference Keynejad, Frodl, Kanaan, Pariante, Reuber and Nicholson2019).

We hypothesised that a more fine-grained analysis of the specific life events in FND might yield more information about its aetiology, therefore, as different types of events are likely to differ in their potentially causative components. We aimed to build on our previous meta-analysis (Ludwig et al., Reference Ludwig, Pasman, Nicholson, Aybek, David, Tuck and Stone2018) by systematically analysing all studies of FND that considered the type of preceding stressors with a view to further defining the risk relationship. Given that the roles and nature of events occurring in childhood are likely to be very different, we restricted our assessment to adulthood.

Methods

Search strategy

We searched the databases PubMed, Medline and Google Scholar using the terms ((Hyster* OR functional neurological* OR psychogenic* OR ‘conversion disorder’) AND (life events OR trauma* OR stress*)), from database inception to search date (February 2019). Where the databases permitted restrictions on results, the searches were limited to studies in English, of adults, of humans and where full text was available. Additional articles were sought from the references of included articles, from five published reviews (Aamir, Reference Aamir2005; Brown & Reuber, Reference Brown and Reuber2016; Fiszman, Alves-Leon, Nunes, Isabella, & Figueira, Reference Fiszman, Alves-Leon, Nunes, Isabella and Figueira2004; Ludwig et al., Reference Ludwig, Pasman, Nicholson, Aybek, David, Tuck and Stone2018; Roelofs & Spinhoven, Reference Roelofs and Spinhoven2007) and by consultation with experts. After review of titles and abstracts, the full text of promising articles was reviewed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria by two authors (SM and RK).

Study inclusion and exclusion

We included studies if (i) the participants were adults (16 years and over); (ii) symptoms were defined in the articles as medically unexplained (neurology), functional, psychogenic, conversion, hysterical or dissociative; (iii) patients had any motor or sensory presentations – including psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES), voice disorders and mixed symptoms; (iv) they included at least 20 patients with FND; (v) they provided qualitative breakdown of preceding life events occurring in adulthood, whether they used a specific screening tool [such as the life events and difficulties schedule (Brown & Harris, Reference Brown and Harris1978), life events checklist (Gray, Litz, Hsu, & Lombardo, Reference Gray, Litz, Hsu and Lombardo2004), presumptive stressful life event scale (Singh, Kaur, & Kaur, Reference Singh, Kaur and Kaur1984)] or not, and whether a preceding event was a diagnostic requirement or not and (vi) they were of any study type (case–control or cohort).

We excluded studies (i) when they were exclusively or largely of children (under 16 years); (ii) where the life events occurred subsequent to the onset of symptoms; (iii) with duplicate data and (iv) which were not available in English or in full text.

Analysis

Data were extracted by SM, with any uncertainty resolved by discussion with RK and then the other authors. We gathered the following data on both patients and, where available, on controls: the gender of subjects, the age of onset of their symptoms, the study country's economic development [developed or developing, according to the United Nations criteria (UN, 2020)], the types of life events, their severity and number. The events of interest were adult life events preceding the onset of symptoms. Where the events clearly post-dated onset, they were excluded, but where the temporal relationship was unclear the authors were contacted to clarify, and if it remained unclear the studies were retained, but noted as a qualification and subgroup analyses undertaken without them. Similarly, events clearly occurring in childhood were excluded, but where this was not specified or was unclear, they were retained but noted as a qualification on the results, and subgroup analyses undertaken without them.

The primary planned analysis was of the type of events most commonly preceding onset (the number of studies where each category was most common, and total number of events in each category), by comparison with control groups where available; secondary analyses were of the differences in the type of event by gender, mean age of onset (before or after the median), economic development (developed and developing) and the number and severity of events. As we anticipated each study would use unique event typologies, we did not have an a priori categorisation for them. Rather, the studies' unique typologies were initially utilised, and an emergent categorisation used, with the types rationalised into as small a number of categories as could be sustained without loss of meaning, by SM, in discussion with RK. Additional comparative analyses were planned for the subgroup of controlled studies, including, where the data permitted it, a meta-analysis of event type, using RevMan 5.3 (The Cochrane Collaboration, 2020), using a random effects model, with heterogeneity quantified by I 2.

We evaluated methodological quality of the included studies using the modified version of the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale we previously used (Ludwig et al., Reference Ludwig, Pasman, Nicholson, Aybek, David, Tuck and Stone2018) for controlled studies and a similarly adapted Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for cohort and cross-sectional studies (Peterson, Welch, Losos, & Tugwell, Reference Peterson, Welch, Losos and Tugwell2011). Each study was assessed by SM and RAK, with uncertainty resolved by consultation with the author group.

Results

Our search identified 2603 studies after removal of duplicates (see PRISMA flowchart, online Supplementary Fig. S1). Two thousand, three hundred and twenty-five articles were excluded because their titles suggested they were not about FND. A further 180 articles were excluded based on their abstract. Finally, 47 articles were excluded after reading the full text, mainly because they did not discuss types of life events, leaving 51 articles for analysis (see Tables 1 and 2, online Supplementary Fig. S1): 30 uncontrolled and 21 case/control – representing 4247 FND patients and 2076 controls. Mixed symptoms (21 studies) and seizures (15 studies) predominated. The included studies were conducted in 19 different countries reflecting both developed and developing economies. Thirteen of the studies' data were suitable for meta-analysis.

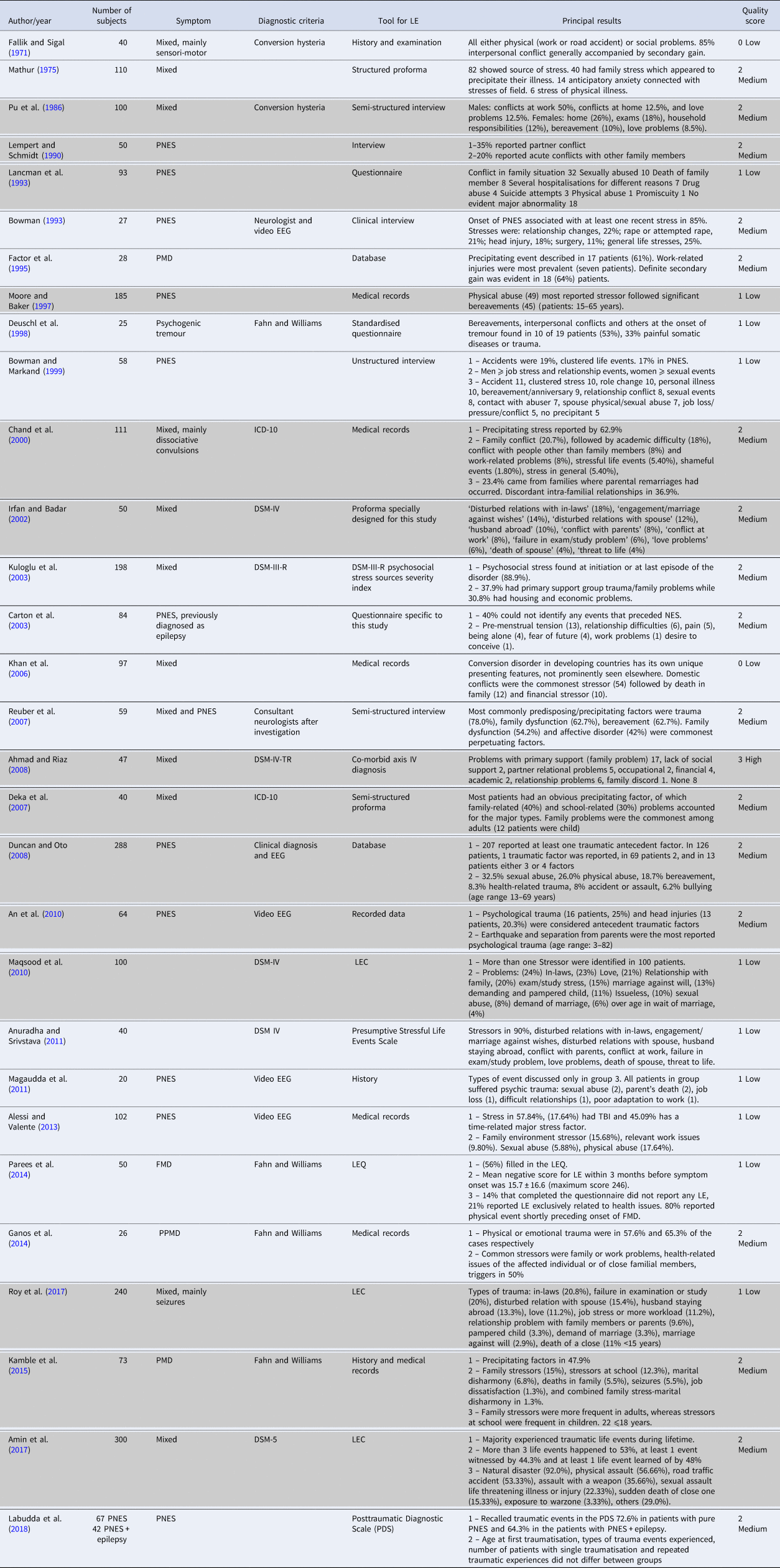

Table 1. Uncontrolled studies

Rows in grey are studies where there were either a minority of children, or it was not clear that all events preceded onset. FMD, functional movement disorders; PNES, psychogenic non-epileptic seizure; LEDS, life events and difficulties schedule; CD, conversion disorder; DRE, drug-resistant epilepsy; OVD, organic voice disorder; FNS, functional neurological symptoms; EEG, electroencephalography; HC, healthy controls; LEC, Life Events Checklist; LEQ, The Life Events Questionnaire; OVS, organically explained vestibular symptoms; PMD, psychogenic movement disorders; CNS, central nervous system; DSM-III, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition; DSM-III-R, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition, Revised; DSM-IV) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition; DSM-IV-TR, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text revision; ICD10, The 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems; DSM-5) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition; PPMD, psychogenic paroxysmal movement disorders.

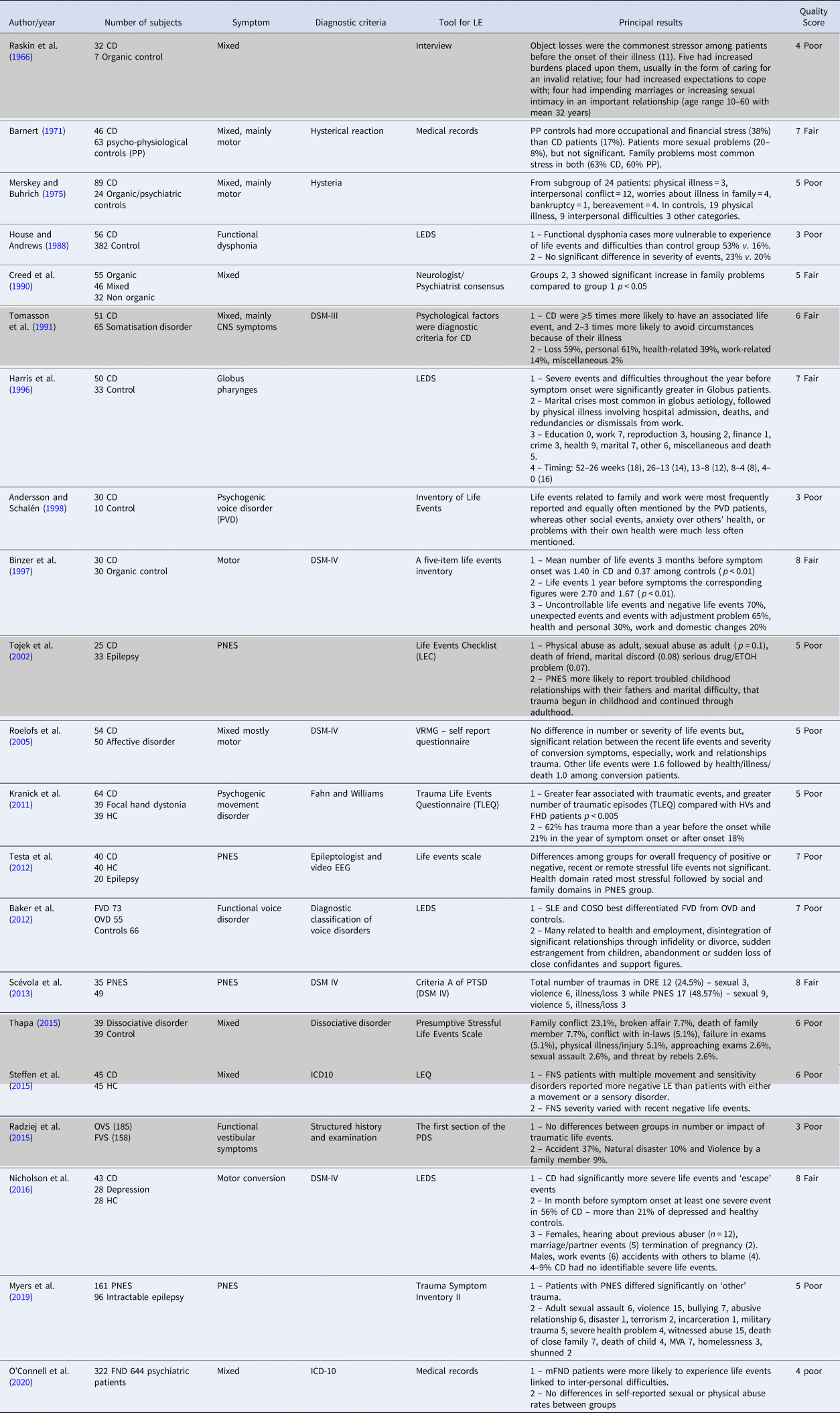

Table 2. Case–control studies

Rows in grey are studies where there were either a minority of children, or it was not clear that all events preceded onset. FMD, functional movement disorders; PNES, psychogenic non-epileptic seizure; LEDS, life events and difficulties schedule; CD, conversion disorder; DRE, drug-resistant epilepsy; OVD, organic voice disorder; FNS, functional neurological symptoms; EEG, electroencephalography; HC, healthy controls; LEC, Life Events Checklist; LEQ, The Life Events Questionnaire; OVS, organically explained vestibular symptoms; PMD, psychogenic movement disorders; CNS, central nervous system; DSM-III, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition; DSM-III-R, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition, Revised; DSM-IV) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition; DSM-IV-TR, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text revision; ICD10, The 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems; DSM-5) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition; PPMD, psychogenic paroxysmal movement disorders.

The range of quality scores for the uncontrolled studies was 0–3 (with a maximum possible score 3) and median of 2 (fair quality), respectively. Controlled studies ranged from 3 to 8 (with a maximum possible score 11) and a median of 5 (poor quality). See online Supplementary Tables S1 and S2 for details.

In 32 studies, the events described clearly preceded the onset of FND, and they were exclusively of adults, whereas in the other 19 these were not so clear: either the temporal relationship could not be definitively established (four studies), a minority (less than half) of their subjects were under 16 (11 studies), or both (four studies). In the following, these 19 studies are denoted as the ‘time/age questionable’ studies, and are highlighted, although all were included in our analysis.

Analysis of all studies

Types of event in patients with FND

The studies' full categorisations of events are presented in Table 3. The categories that recurred most frequently were Family, Relationships, Abuse/violence, Health, Accidents and Work (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Number of studies where each category of event was commonest. Where a study had a combined category (such as ‘family or health’) or had two equally commonest categories, each category is counted half a study.

Table 3. Number of events by category in all studies that included numerical categorisation, patients only

Original categories or synonyms used; no categories have been merged. Categories with fewer than ten cases in total are not shown. (*) 3 battle stress 3 strenuous work 2 fear of army 1 handling dead bodies (1) 21 conflict at home 7 household responsibilities (2) 44 family/relationship events (3) 8 sexual abuse 7 contact with abuser 7 spouse physical or sexual abuse (4) separation from loved one (5) economic and migration (b) 13 premenstrual tension 5 pain (6) illness in family (7) 14 family/ relationship events (a) 51 Adults (8) severe illness/loss of loved one (9) 15 violence + 15 witnessed abuse (10) 50 (in-laws) 37 (spouse) 23 (family member) 27 love problem (11) 7 violence by a family member 11 violence by a stranger 2 torture (12) Traumatic brain injury (13) 1 job loss 1 poor adaptation to work (14) 8 demands of marriage and 6 late marriage (15) Giving birth (16) Academic failure of child (17) worry about illness in family (18) 7 partner 6 other including children (19) death/ miscellaneous (20) reproduction (21) include health of others (22) hearing of previous abuser (23) termination of pregnancy.

Family was the most common category of preceding stressful life event in 18 studies, the largest number (Ahmad & Riaz, Reference Ahmad and Riaz2008; An, Wu, Yan, Mu, & Zhou, Reference An, Wu, Yan, Mu and Zhou2010; Andersson & Schalén, Reference Andersson and Schalén1998; Anuradha & Srivstava, Reference Anuradha and Srivstava2011; Barnert, Reference Barnert1971; Chand et al., Reference Chand, Al-Hussaini, Martin, Mustapha, Zaidan, Viernes and Al-Adawi2000; Creed, Firth, Timol, Metcalfe, & Pollock, Reference Creed, Firth, Timol, Metcalfe and Pollock1990; Deka, Chaudhury, Bora, & Kalita, Reference Deka, Chaudhury, Bora and Kalita2007; Kamble et al., Reference Kamble, Prashantha, Jha, Netravathi, Reddy and Pal2015; Kuloglu, Atmaca, Tezcan, Gecici, & Bulut, Reference Kuloglu, Atmaca, Tezcan, Gecici and Bulut2003; Lancman, Brotherton, Asconapé, & Kiffin Penry, Reference Lancman, Brotherton, Asconapé and Kiffin Penry1993; Magaudda et al., Reference Magaudda, Gugliotta, Tallarico, Buccheri, Alfa and Laganà2011; Mathur, Reference Mathur1975; Pu, Mohamed, Imam, & El-Roey, Reference Pu, Mohamed, Imam and El-Roey1986; Raskin et al., Reference Raskin, Talbott and Meyerson1966; Reuber, Howlett, Khan, & Grunewald, Reference Reuber, Howlett, Khan and Grunewald2007; Thapa, Reference Thapa2015; Tomasson, Kent, & Coryell, Reference Tomasson, Kent and Coryell1991). Second were relationship difficulties, the commonest event category in 12 studies (Deuschl, Köster, Lucking, & Scheidt, Reference Deuschl, Köster, Lucking and Scheidt1998; Fallik & Sigal, Reference Fallik and Sigal1971; Irfan & Badar, Reference Irfan and Badar2002; Khan et al., Reference Khan, Ladha, Khan, Khan, Malik, Memon and Naqvi2006; Lempert & Schmidt, Reference Lempert and Schmidt1990; Maqsood, Akram, & Ali, Reference Maqsood, Akram and Ali2010; Merskey & Buhrich, Reference Merskey and Buhrich1975; O'Connell, Nicholson, Wessely, & David, Reference O'Connell, Nicholson, Wessely and David2020; Raskin et al., Reference Raskin, Talbott and Meyerson1966; Reuber et al., Reference Reuber, Howlett, Khan and Grunewald2007; Roy et al., Reference Roy, Akhter, Begum, Karim, Begum and Roy2017; Tomasson et al., Reference Tomasson, Kent and Coryell1991). Next were eight studies where the commonest category was abuse/violence – of these, sexual abuse was commonest in four (Duncan & Oto, Reference Duncan and Oto2008; Magaudda et al., Reference Magaudda, Gugliotta, Tallarico, Buccheri, Alfa and Laganà2011; Nicholson et al., Reference Nicholson, Aybek, Craig, Harris, Wojcik, David and Kanaan2016; Scévola et al., Reference Scévola, Teitelbaum, Oddo, Centurión, Loidl and Kochen2013), physical abuse in three (Alessi & Valente, Reference Alessi and Valente2013; Labudda et al., Reference Labudda, Frauenheim, Illies, Miller, Schrecke, Vietmeier and Bien2018; Moore & Baker, Reference Moore and Baker1997), and violence the commonest in one (Myers et al., Reference Myers, Trobliger, Bortnik, Zeng, Saal and Lancman2019). Health issues were the most commonly reported events in six studies (Binzer, Andersen, & Kullgren, Reference Binzer, Andersen and Kullgren1997; Carton, Thompson, & Duncan, Reference Carton, Thompson and Duncan2003; Ganos et al., Reference Ganos, Aguirregomozcorta, Batla, Stamelou, Schwingenschuh, Münchau and Bhatia2014; Harris, Deary, & Wilson, Reference Harris, Deary and Wilson1996; Parees et al., Reference Parees, Kojovic, Pires, Rubio-Agusti, Saifee, Sadnicka and Edwards2014; Testa, Krauss, Lesser, & Brandt, Reference Testa, Krauss, Lesser and Brandt2012); in two it was accident (Bowman & Markand, Reference Bowman and Markand1999; Radziej, Schmid, Dinkel, Zwergal, & Lahmann, Reference Radziej, Schmid, Dinkel, Zwergal and Lahmann2015) whereas one (Factor, Podskalny, & Molho, Reference Factor, Podskalny and Molho1995) found it to be work-related problems. The remaining four studies had a largest category of ‘general traumas’ (Bowman, Reference Bowman1993), natural disaster (Amin, Dar, Maqbool, Paul, & Kawoos, Reference Amin, Dar, Maqbool, Paul and Kawoos2017), earthquakes/separation from parents (An et al., Reference An, Wu, Yan, Mu and Zhou2010) and family/education problems (Anuradha & Srivstava, Reference Anuradha and Srivstava2011). If we exclude the ‘time/age questionable’ studies, this would have the effect of promoting both abuse and health to joint second with relationship problems.

Effect of gender on type of event

Ten of the studies compared events between genders (Anuradha & Srivstava, Reference Anuradha and Srivstava2011; Bowman & Markand, Reference Bowman and Markand1999; Duncan & Oto, Reference Duncan and Oto2008; Factor et al., Reference Factor, Podskalny and Molho1995; Ganos et al., Reference Ganos, Aguirregomozcorta, Batla, Stamelou, Schwingenschuh, Münchau and Bhatia2014; House & Andrews, Reference House and Andrews1988; Kamble et al., Reference Kamble, Prashantha, Jha, Netravathi, Reddy and Pal2015; Nicholson et al., Reference Nicholson, Aybek, Craig, Harris, Wojcik, David and Kanaan2016; Pu et al., Reference Pu, Mohamed, Imam and El-Roey1986; Reuber et al., Reference Reuber, Howlett, Khan and Grunewald2007), nine of them finding that females and males differed, and one that they did not (Ganos et al., Reference Ganos, Aguirregomozcorta, Batla, Stamelou, Schwingenschuh, Münchau and Bhatia2014). Family and relationship events were the commonest category most frequently in females, and work events in males. Excluding the ‘time/age questionable’ studies would remove three of those that differed (see online Supplementary Table S4).

Effect of economic development on type of event

The current review included 33 studies in developed countries (12 in UK, 11 in USA, 5 in Germany and 1 each in Australia, Italy, Netherland, Sweden and Denmark) and 18 studies in developing countries (5 in India, 4 in Pakistan and one each in Nepal, Bangladesh, Brazil, Argentina, China, Israel, Turkey, Libya and Oman) – see Fig. 2. In studies in developed countries, the most common event categories were, in descending order, family and health, equally, followed by abuse and then relationship difficulties. In developing countries, family problems (9) was the most commonly reported stressor category followed by relationship difficulties (5).

Fig. 2. Most common category of events in studies in developed and developing countries. Where a study had a combined category (such as ‘family or health’) or had two equally commonest categories, each category is counted half a study.

Effect of age of onset

Twenty of our studies reported the age of onset of FND (Alessi & Valente, Reference Alessi and Valente2013; An et al., Reference An, Wu, Yan, Mu and Zhou2010; Bowman, Reference Bowman1993; Carton et al., Reference Carton, Thompson and Duncan2003; Deuschl et al., Reference Deuschl, Köster, Lucking and Scheidt1998; Ganos et al., Reference Ganos, Aguirregomozcorta, Batla, Stamelou, Schwingenschuh, Münchau and Bhatia2014; Kamble et al., Reference Kamble, Prashantha, Jha, Netravathi, Reddy and Pal2015; Kranick et al., Reference Kranick, Ekanayake, Martinez, Ameli, Hallett and Voon2011; Labudda et al., Reference Labudda, Frauenheim, Illies, Miller, Schrecke, Vietmeier and Bien2018; Lancman et al., Reference Lancman, Brotherton, Asconapé and Kiffin Penry1993; Lempert & Schmidt, Reference Lempert and Schmidt1990; Magaudda et al., Reference Magaudda, Gugliotta, Tallarico, Buccheri, Alfa and Laganà2011; Moore & Baker, Reference Moore and Baker1997; Myers et al., Reference Myers, Trobliger, Bortnik, Zeng, Saal and Lancman2019; O'Connell et al., Reference O'Connell, Nicholson, Wessely and David2020; Reuber et al., Reference Reuber, Howlett, Khan and Grunewald2007; Testa et al., Reference Testa, Krauss, Lesser and Brandt2012; Thapa, Reference Thapa2015; Tojek, Mahr, Lumley, Thomas, & Barkley, Reference Tojek, Mahr, Lumley, Thomas and Barkley2002; Tomasson et al., Reference Tomasson, Kent and Coryell1991). The mean age of onset ranged from 21 (An et al., Reference An, Wu, Yan, Mu and Zhou2010) to 42 (Deuschl et al., Reference Deuschl, Köster, Lucking and Scheidt1998), with a median of 29/30, see Table 4. Dividing the studies into those with mean age of onset higher and lower than (or equal to) the median, nine of the 10 studies with earlier onset were of PNES (Alessi & Valente, Reference Alessi and Valente2013; An et al., Reference An, Wu, Yan, Mu and Zhou2010; Bowman, Reference Bowman1993; Carton et al., Reference Carton, Thompson and Duncan2003; Labudda et al., Reference Labudda, Frauenheim, Illies, Miller, Schrecke, Vietmeier and Bien2018; Lempert & Schmidt, Reference Lempert and Schmidt1990; Magaudda et al., Reference Magaudda, Gugliotta, Tallarico, Buccheri, Alfa and Laganà2011; Moore & Baker, Reference Moore and Baker1997; Tojek et al., Reference Tojek, Mahr, Lumley, Thomas and Barkley2002), whereas the three with latest onset were of psychogenic movement disorder (Deuschl et al., Reference Deuschl, Köster, Lucking and Scheidt1998; Ganos et al., Reference Ganos, Aguirregomozcorta, Batla, Stamelou, Schwingenschuh, Münchau and Bhatia2014; Kranick et al., Reference Kranick, Ekanayake, Martinez, Ameli, Hallett and Voon2011). Experience of abuse was more commonly associated with early onset (Alessi & Valente, Reference Alessi and Valente2013; Labudda et al., Reference Labudda, Frauenheim, Illies, Miller, Schrecke, Vietmeier and Bien2018; Magaudda et al., Reference Magaudda, Gugliotta, Tallarico, Buccheri, Alfa and Laganà2011; Moore & Baker, Reference Moore and Baker1997), whereas family problems were the commonest stressors associated with later onset (Kamble et al., Reference Kamble, Prashantha, Jha, Netravathi, Reddy and Pal2015; Lancman et al., Reference Lancman, Brotherton, Asconapé and Kiffin Penry1993; Reuber et al., Reference Reuber, Howlett, Khan and Grunewald2007). Excluding the ‘time/age questionable’ studies would make health and relationship events equally common with family events in the older onset group. Post-hoc, we also considered these data from the perspective of symptom type, and although the studies are fewer, we note the suggestion of difference – 5 of 12 studies of seizures had abuse as the commonest event, compared with none of the others – although given the apparent distinction of age of onset, any symptom-specific difference in events may be confounded by this difference in age.

Table 4. Commonest category of event by age at FND onset

Those in grey have later age of onset than the median. NA, not available.

Number of events per patient

Thirty-seven studies allowed a calculation of the mean number of events per patient: in 20 of these (Ahmad & Riaz, Reference Ahmad and Riaz2008; Amin et al., Reference Amin, Dar, Maqbool, Paul and Kawoos2017; Andersson & Schalén, Reference Andersson and Schalén1998; Bowman, Reference Bowman1993; Bowman & Markand, Reference Bowman and Markand1999; Deka et al., Reference Deka, Chaudhury, Bora and Kalita2007; Duncan & Oto, Reference Duncan and Oto2008; Harris et al., Reference Harris, Deary and Wilson1996; Kuloglu et al., Reference Kuloglu, Atmaca, Tezcan, Gecici and Bulut2003; Labudda et al., Reference Labudda, Frauenheim, Illies, Miller, Schrecke, Vietmeier and Bien2018; Magaudda et al., Reference Magaudda, Gugliotta, Tallarico, Buccheri, Alfa and Laganà2011; Maqsood et al., Reference Maqsood, Akram and Ali2010; Merskey & Buhrich, Reference Merskey and Buhrich1975; Moore & Baker, Reference Moore and Baker1997; Nicholson et al., Reference Nicholson, Aybek, Craig, Harris, Wojcik, David and Kanaan2016; O'Connell et al., Reference O'Connell, Nicholson, Wessely and David2020; Radziej et al., Reference Radziej, Schmid, Dinkel, Zwergal and Lahmann2015; Reuber et al., Reference Reuber, Howlett, Khan and Grunewald2007; Roy et al., Reference Roy, Akhter, Begum, Karim, Begum and Roy2017; Tomasson et al., Reference Tomasson, Kent and Coryell1991), there was more than one event per patient; in the other 17 (Alessi & Valente, Reference Alessi and Valente2013; An et al., Reference An, Wu, Yan, Mu and Zhou2010; Carton et al., Reference Carton, Thompson and Duncan2003; Chand et al., Reference Chand, Al-Hussaini, Martin, Mustapha, Zaidan, Viernes and Al-Adawi2000; Creed et al., Reference Creed, Firth, Timol, Metcalfe and Pollock1990; Factor et al., Reference Factor, Podskalny and Molho1995; Irfan & Badar, Reference Irfan and Badar2002; Kamble et al., Reference Kamble, Prashantha, Jha, Netravathi, Reddy and Pal2015; Khan et al., Reference Khan, Ladha, Khan, Khan, Malik, Memon and Naqvi2006; Lancman et al., Reference Lancman, Brotherton, Asconapé and Kiffin Penry1993; Lempert & Schmidt, Reference Lempert and Schmidt1990; Mathur, Reference Mathur1975; Myers et al., Reference Myers, Trobliger, Bortnik, Zeng, Saal and Lancman2019; Pu et al., Reference Pu, Mohamed, Imam and El-Roey1986; Raskin et al., Reference Raskin, Talbott and Meyerson1966; Scévola et al., Reference Scévola, Teitelbaum, Oddo, Centurión, Loidl and Kochen2013; Thapa, Reference Thapa2015) there was less than one event per patient. The median study had 1 event per patient, and the overall mean number of events per patient over all 37 studies was 1.2. Although this suggests the majority of patients had only 1 event, five studies (Bowman, Reference Bowman1993; Duncan & Oto, Reference Duncan and Oto2008; Labudda et al., Reference Labudda, Frauenheim, Illies, Miller, Schrecke, Vietmeier and Bien2018; Radziej et al., Reference Radziej, Schmid, Dinkel, Zwergal and Lahmann2015; Reuber et al., Reference Reuber, Howlett, Khan and Grunewald2007) reported that some of their patients had no events (and other studies may have found the same but not reported it), which means that those patients who did have events had proportionately more.

Analysis of controlled studies

The subset of controlled studies allows comparative and quantitative studies of the commonest category and meta-analysis of types. Additionally, four of the controlled studies (Baker, Ben-Tovim, Butcher, Esterman, & McLaughlin, Reference Baker, Ben-Tovim, Butcher, Esterman and McLaughlin2012; Harris et al., Reference Harris, Deary and Wilson1996; House & Andrews, Reference House and Andrews1988; Nicholson et al., Reference Nicholson, Aybek, Craig, Harris, Wojcik, David and Kanaan2016) used the Life Events and Difficulties Schedule (LEDS), which allow additional analyses – the timing and severity of events, but also study-specific event typologies, hypothesised to be of particular relevance to FND.

Types of event – commonest category and meta-analysis

Among the 21 controlled studies, 16 found differences between patients and controls in the proportions of types of events experienced (Andersson & Schalén, Reference Andersson and Schalén1998; Baker et al., Reference Baker, Ben-Tovim, Butcher, Esterman and McLaughlin2012; Barnert, Reference Barnert1971; Binzer et al., Reference Binzer, Andersen and Kullgren1997; Creed et al., Reference Creed, Firth, Timol, Metcalfe and Pollock1990; Harris et al., Reference Harris, Deary and Wilson1996; House & Andrews, Reference House and Andrews1988; Merskey & Buhrich, Reference Merskey and Buhrich1975; Myers et al., Reference Myers, Trobliger, Bortnik, Zeng, Saal and Lancman2019; Nicholson et al., Reference Nicholson, Aybek, Craig, Harris, Wojcik, David and Kanaan2016; O'Connell et al., Reference O'Connell, Nicholson, Wessely and David2020; Raskin et al., Reference Raskin, Talbott and Meyerson1966; Scévola et al., Reference Scévola, Teitelbaum, Oddo, Centurión, Loidl and Kochen2013; Testa et al., Reference Testa, Krauss, Lesser and Brandt2012; Tojek et al., Reference Tojek, Mahr, Lumley, Thomas and Barkley2002; Tomasson et al., Reference Tomasson, Kent and Coryell1991), two found no difference between groups (Radziej et al., Reference Radziej, Schmid, Dinkel, Zwergal and Lahmann2015; Roelofs, Spinhoven, Sandijck, Moene, & Hoogduin, Reference Roelofs, Spinhoven, Sandijck, Moene and Hoogduin2005) and three did not include these data (Kranick et al., Reference Kranick, Ekanayake, Martinez, Ameli, Hallett and Voon2011; Steffen, Fiess, Schmidt, & Rockstroh, Reference Steffen, Fiess, Schmidt and Rockstroh2015; Thapa, Reference Thapa2015) (see Table 3 and online Supplementary Table S3). Of these studies, nine (Barnert, Reference Barnert1971; Creed et al., Reference Creed, Firth, Timol, Metcalfe and Pollock1990; Harris et al., Reference Harris, Deary and Wilson1996; Merskey & Buhrich, Reference Merskey and Buhrich1975; Myers et al., Reference Myers, Trobliger, Bortnik, Zeng, Saal and Lancman2019; Radziej et al., Reference Radziej, Schmid, Dinkel, Zwergal and Lahmann2015; Scévola et al., Reference Scévola, Teitelbaum, Oddo, Centurión, Loidl and Kochen2013; Tomasson et al., Reference Tomasson, Kent and Coryell1991) included sufficient type data to allow the determination of a commonest type of event for both patients and controls. All nine of these compared the patients to pathological control groups (including two comparing to somatisation disorder). In terms of the commonest type of event, there were four differences between patients and controls, where relationship events were the commonest in patients but not in controls (Merskey & Buhrich, Reference Merskey and Buhrich1975; O'Connell et al., Reference O'Connell, Nicholson, Wessely and David2020), sexual trauma commonest in patients compared with physical violence in controls (Scévola et al., Reference Scévola, Teitelbaum, Oddo, Centurión, Loidl and Kochen2013) and financial/legal events equally common with family events in controls, but not in patients (Creed et al., Reference Creed, Firth, Timol, Metcalfe and Pollock1990) – see online Supplementary Table S5.

These same nine studies' data permitted meta-analysis of event type, combining types to create 10 categories: work and education events, family events and bereavements, relationship events, accidents, legal events, health events, physical or sexual assault or abuse, warfare, disasters and financial events (see online Supplementary Table S3 for details). Although family (31% of all cases, unweighted), assaults (25%) and relationship events (24%) were the most common events preceding illness onset in FND (see Fig. 3), that was also true for pathological controls. However, work (odds ratio (OR) 3.95, p < 0.001), family (OR 3.13, p < 0.0001) and relationship events (OR 2.12, p = 0.04) were more common preceding FND than controls by random effects meta-analysis (see Fig. 3). The other categories of events did not differ between groups.

Fig. 3. Forrest plot of meta-analysis of nine controlled studies of events in FND compared with pathological controls.

Fig. 4. Forrest plot of studies that examined events where symptoms might provide a solution to the stressor. The control group in Raskin et al. was pathological controls, otherwise the comparisons are with the healthy control groups.

Types of event – study-specific typologies

The LEDS has a unique way of rating events through ‘contextual measures’, typically study-specific typologies hypothesised to be of particular disease relevance. For example, the ‘Escape’ rating (Aybek et al., Reference Aybek, Nicholson, Zelaya, O'Daly, Craig, David and Kanaan2014), developed by some of the authors of this review, measures the extent to which the effects of an event could be ameliorated by subsequently developing an illness (hence, ‘escaping’ from the event through illness). This was derived from Raskin et al. (Reference Raskin, Talbott and Meyerson1966), who found that gain from symptoms solved the conflicts of the precipitating stressors. House and Andrews (Reference House and Andrews1988) and Baker et al. (Reference Baker, Ben-Tovim, Butcher, Esterman and McLaughlin2012) measured ‘conflict over speaking out’ (CSO) – the extent to which events involve subjects being under pressure to say something, even though doing so might worsen the situation. This can also be understood to reflect Raskin's concept of the symptom potentially solving the problem of the stressor, since in these studies the symptoms were voice disorders. Finally, Harris et al. (Reference Harris, Deary and Wilson1996) assessed ‘loss’ and ‘danger’ – respectively, the amount of loss for the subject resulting from the event and the degree of unpleasantness from a specific future crisis that might occur as a result of the event.

All found significant differences in their contextual measures. Baker et al. and House and Andrews found their patients with functional voice disorder experienced more severe CSO events than their respective healthy controls, and more than the organic voice disorder group in Baker et al. (Baker et al. Reference Baker, Ben-Tovim, Butcher, Esterman and McLaughlin2012; House & Andrews, Reference House and Andrews1988); Nicholson et al. found that FND patients reported higher rates of Escape events than either depressed or healthy controls (Nicholson et al., Reference Nicholson, Aybek, Craig, Harris, Wojcik, David and Kanaan2016). Combining the three LEDS studies which, as above, can be seen to have measured events where symptoms may provide a solution together with Raskin et al. in a meta-analysis, found such events were markedly more common in patients than in controls (unweighted proportion of 54% v. 8%) [OR 13.11(95% confidence interval (CI) 6.85–25.09), p < 0.00001, I 2 = 0%; Fig. 4]. Repeating the analysis without Raskin et al. due to its small control group, would trim the OR to 12.99 (95% CI 6.53–25.83), p < 0.00001, I 2 = 0%); using the pathological, instead of the healthy, control groups in Nicholson et al. and Baker et al., would reduce the OR to 7.6 (95% CI 3.05–18.9), p < 0.0001, I 2 = 54%). Note that the LEDS makes a distinction between ‘events’, which are briefer, resolving within a couple of weeks, and ‘difficulties’, which are sustained problems over a month or more. The above comparisons are of their ‘events’, which are presented in more detail and more uniformly, although the studies appeared to find similar patterns with their ‘difficulties’.

Severity of events

Six of the studies measured severity, using somewhat different methods. Roelofs et al. (Reference Roelofs, Spinhoven, Sandijck, Moene and Hoogduin2005) and Radziej et al. (Reference Radziej, Schmid, Dinkel, Zwergal and Lahmann2015) used self-report ratings of the impact of events, the former basing this on the self-rated ‘unpleasantness’ of the event, and Radziej measuring PTSD-type symptoms arising from the event. Neither found difference in these measures between patients with FND and healthy controls. The four LEDS studies all rated severity either by the assessor or by a blinded panel, defining it as how ‘threatening’ a typical person would find the event if they were in the subject's circumstances. Three of the four studies found their patients with FND had more severe events than controls (Baker et al., Reference Baker, Ben-Tovim, Butcher, Esterman and McLaughlin2012; Harris et al., Reference Harris, Deary and Wilson1996; Nicholson et al., Reference Nicholson, Aybek, Craig, Harris, Wojcik, David and Kanaan2016), whereas the difference in House and Andrews (Reference House and Andrews1988) was not significant. Note that these differences, although often substantial (Baker et al., for example, found 74% of their patients with FND had had a severe event in the preceding year, compared with 13% of healthy controls), were of proportions of subjects, not of events, and would therefore potentially be confounded by the overall greater number of events previously demonstrated in FND (Ludwig et al., Reference Ludwig, Pasman, Nicholson, Aybek, David, Tuck and Stone2018): however, in each of the three (Baker et al., Reference Baker, Ben-Tovim, Butcher, Esterman and McLaughlin2012; Harris et al., Reference Harris, Deary and Wilson1996; Nicholson et al., Reference Nicholson, Aybek, Craig, Harris, Wojcik, David and Kanaan2016), the total number of events (Harris et al., Reference Harris, Deary and Wilson1996), or proportion having events of any kind (Baker et al., Reference Baker, Ben-Tovim, Butcher, Esterman and McLaughlin2012; Nicholson et al., Reference Nicholson, Aybek, Craig, Harris, Wojcik, David and Kanaan2016), did not differ between groups, only the proportion of severe events, so this confound appears unlikely.

Timing of events

Three of the LEDS studies (Harris et al., Reference Harris, Deary and Wilson1996; House & Andrews, Reference House and Andrews1988; Nicholson et al., Reference Nicholson, Aybek, Craig, Harris, Wojcik, David and Kanaan2016) and Binzer et al. (Binzer et al. (Reference Binzer, Andersen and Kullgren1997) divided the preceding events into different epochs – typically, the preceding 12 months and 3 months – allowing a temporal characterisation of events in relation to onset. Although all appeared to show similar pictures, of events being proportionately more common closer to onset in FND compared with controls, none provided a statistical calculation. Both Binzer et al. (Reference Binzer, Andersen and Kullgren1997) and Harris et al. (Reference Harris, Deary and Wilson1996) found that more than half of the number of annual events occurring in patients with FND occurred in the last 3 months before they became ill, whereas for controls they were evenly distributed, with under a quarter of events occurring in the last quarter of the year. Nicholson et al. provided the most detailed description (Nicholson et al., Reference Nicholson, Aybek, Craig, Harris, Wojcik, David and Kanaan2016), breaking down epochs into the preceding month, week and day, in addition, and found that all groups had proportionately more events closer to onset, but that the difference was largest for the patients with FND. Although these differences appear very substantial (annualised rates over four times higher in the last day before onset in FND, compared with healthy controls, e.g.), no confirmation of statistical significance is possible given the data. Finally, although House et al. did not provide a statistical comparison, their data permit one: more of their women had a CSO event in the 4 weeks before onset (21%) than in the whole rest of the year (13%), whereas none of their healthy controls had a CSO event in the last 4 weeks, and 6% did in the rest of the year, a difference which was not quite significant (Fisher's exact test, p = 0.078).

Discussion

Taking all of the studies together, the commonest category of event preceding the onset of FND was ‘family events’ in the largest number of studies, followed by relationship events. Taking these categories together, as reflecting problems with significant others, would make them the commonest category in the majority of studies (30 of 51). Potential contributors to this were found in the effects of economic development, gender and age, and possibly of symptom type. The median number of events reported before the onset of FND was one. In the controlled studies, although there were some similarities, most (16 of 18) found differences in the types of events patients with FND experienced from their control groups. In meta-analysis of nine studies, family, relationship and work events were more common in patients with FND than in their pathological comparator groups. Those four studies that compared events in which patients' symptoms had the potential to solve the problem of their stressful event found these events were more common in patients with FND than in healthy or pathological controls, and preceded the onset of most FND cases. The analyses of severity and timing suggested that events were proportionately closer to the onset of FND, and proportionately more severe, than in controls, but statistical testing was not available, and the number of studies was relatively small. In summary, as hypothesised, these reveal that the risk relationship with life events appears different from their comparator conditions in those respects. Returning to the models in our introduction, we did not find support for the Freudian idea that shameful events were in excess of other events, but arguably did find support for the idea that events were more likely to occur in interpersonal relationships, broadly understood.

There are substantial limitations to our analysis. First, the variation was very substantial, only partly due to methodological differences: few of the effects noted occurred in a majority of studies or a majority of patients. The assessment of events was made using different tools/questionnaires, which made comparisons inexact. Many of these tools were self-report, which may be more valid, given that it is the subjective experience that is likely to be important; but they inevitably make recall bias more likely, and may be particularly problematic if the disorder of interest is hypothesised to involve under-reporting through some pathological process, such as repression or dissociation (Kanaan & Craig, Reference Kanaan and Craig2019). Many were assessed through clinical history, which runs a clear risk of under-reporting, particularly of event types where disclosure to another may be inhibited, such as those considered illegal or immoral. A meta-analysis of these different approaches may reduce this variation to a single number, but it will dilute the contribution of the better studies with the worse. Some studies did not give exact numbers of subjects for each category, and only the LEDS studies considered the duration of events. Although we tried to limit our analysis to adult events, some of our studies included some children, and it was rarely possible to definitively establish that the events occurred in adulthood (even in adult subjects) as this information was not usually given. The timing of events was in general a weakness of the studies, with seven studies establishing that all of their events preceded onset and only a handful giving a temporal breakdown in any detail. We divided our cases by stage of economic development, which is a crude measure and perhaps only significant because it indexes associated cultural factors such as the social position of women. We categorised events into types, which unavoidably required a degree of interpretation because every study had its own categorisation system, which sometimes involved unique terminology, or might use similar terms with quite different meanings. One prominent example would be ‘sexual events’, which in some studies clearly referred to sexual violence, and in others clearly referred to sexual problems in intimate relationships, and in yet others left this unspecified. We were in every case limited by the descriptions provided in the studies, which sometimes were sparse. We did not combine categories unless they were clearly synonymous, or subordinate, but sometimes we were forced to combine where studies did: for example, if one study in an analysis used a combined category of ‘work and education’, we would do likewise for the other studies in that analysis. Our pooling for the meta-analysis of studies where the symptoms might provide a solution to the stressor, although we feel it is a reasonable deduction, does go beyond the original concepts of those measures. Most studies were uncontrolled, and the overall quality of the studies was low-medium. Studies used different criteria for FND, and one-third did not mention which criteria they used, if any, so some studies may have included subjects that would not be considered to have FND today and the heterogeneity of studies is likely to be even higher. Although the statistical heterogeneity in our meta-analyses was low, except in the pathological controls sub-analysis, the studies are clearly diverse, and we have presented random-effects analyses as a result. Publication bias in favour of studies which identified a positive association with event types cannot be excluded, and we had too few studies in our meta-analyses for funnel plots. This is relatively weak evidence, or these are relatively weak effects, or both.

Nevertheless, these features, particularly where they differ from controls, are potentially informative about the role of stressors in the aetiology of FND. The relative proximity of events to onset would argue for a critical role for the final event and that the process from event to symptoms in these cases is relatively quick – with the events acting as a final trigger, perhaps in someone with general vulnerability (Parees et al., Reference Parees, Kojovic, Pires, Rubio-Agusti, Saifee, Sadnicka and Edwards2014). Equally, it appears that in very many cases it was a single event, rather than an accumulation of events, which served that role. The most challenging data to interpret regards event type. We asked whether a particular type of event would be disproportionately common preceding FND, and found that three types were – events in work, family and relationships. These may simply reflect confounding, of course, for example by the age, gender or cultural background propensities to increase family events we reported above. And although some of the contributing studies controlled for some of these effects (see online Supplementary Table S2), other confounds, of unmeasured variables, are always possible. But, the more intriguing possibility, and the premise of this study, is that these types of events may be richer in some ingredient that is particularly aetiologically potent for FND.

We can only speculate as to what that ingredient, or ingredients, might be. The workplace and the family may suggest a response to gendered power relationships (Micale, Reference Micale1995). But, from a more contemporary perspective, we note that work, family and relationships are categories considered particularly likely to be implicated in our concept of ‘Escape’, the potential some events have of being resolved by a subsequent illness (Nicholson et al., Reference Nicholson, Aybek, Craig, Harris, Wojcik, David and Kanaan2016). Therefore, through that lens, work problems might be solved by becoming sick, because the sick person avoids the bullying boss; family problems might be solved by becoming sick, because the sick person no longer needs to care for their abusive uncle and so on. There are obviously many other possibilities for what the ingredient might be, but unlike those others, ‘events where symptoms may provide a solution’ was studied in this review, and its association with the onset of FND was strongest of all.

Even this possibility requires significant qualification, however. First, an association does not mean causation. It may be that events where symptoms may provide a solution is only associated because it leads to patients being identified for studies, for example, or because it is associated with symptoms that endure, perhaps preventing recovery. Second, there were still clearly many patients with FND who had no history of such events, and many controls who did, so it is far from a sufficient explanation. If we extend our causal typology, this suggests a variety of differing models are in play. It is also very clear that FND is multi-factorial in its aetiology: given how frequently such events occur in the population, we would expect a global epidemic of FND if they were enough to cause FND by themselves (Espay et al., Reference Espay, Aybek, Carson, Edwards, Goldstein, Hallett and Morgante2018). In most patients, there must be other factors, vulnerability arising from earlier adversity, antecedent co-morbidity or co-incident trauma, that lead to the development of symptoms at the moment they do. Third, it cannot be taken to imply anything deliberate or conscious on the part of patients with FND, therefore we are not suggesting that individuals choose to be unwell (Kanaan & Jamroz, Reference Kanaan and Jamroz2018). Defences which resolve problems are found in animals (Kanaan, Reference Kanaan2010), presumably unconsciously, and there is preliminary evidence to suggest defences against external threat, operating quite automatically, may be abnormal in FND (Zito, Apazoglou, Paraschiv-Ionescu, Aminian, & Aybek, Reference Zito, Apazoglou, Paraschiv-Ionescu, Aminian and Aybek2019).

It is also clear that the support for this position needs significant strengthening, given the limitations of the evidence. Studies which directly tested its distinctive features would provide the most compelling evidence, but they are more challenging to conduct. LEDS studies permit this kind of specific enquiry, and do have an approach to managing the key biases that arise in life events research, but they are highly time-intensive. So that although it is as always true to say that larger studies are needed to replicate these findings, this will require considerable commitment from researchers if they are to avoid the many pitfalls that conducting life events research in this area has involved so far.

Conclusions

The risk relationship between life events and FND appears to differ from other conditions in some respects. Events involving work, families and relationships appear to be particularly common, possibly because they afford more opportunity for ‘Escape’ from the consequences of the event. In most patients, it appears that only a single preceding event occurred, and this occurred closer to symptom onset than in comparator conditions. The variation was considerable, however, and the quality of the studies was generally low-medium, and the evidence often indirect. Studies which directly tested the distinctive features of this model would provide more compelling evidence.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721004669.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

Alan Carson is unpaid president elect of the functional neurological disorders society, holds a range of grants for assessment and treatment of fnd, and gives independent testimony in Court on a range of neuropsychiatric subjects including FND.