As medicine has become more subspecialised in recent years, a growing number of medical trainees have chosen to pursue additional, subspecialty training. Reference Cassel and Reuben1,Reference Lewis, Mehta and Douglas2 In addition, governing bodies have made efforts to regulate licensed subspecialties while the digitalisation of modern society has progressed. Reference Warnes, Bhatt, Daniels, Gillam and Stout3–Reference Stout, Valente and Bartz5 Training is likely to be most effective if the programme both adheres to the fellows’ preferences and utilises evidence-based teaching strategies. Reference Sawatsky, Zickmund, Berlacher, Lesky and Granieri6

Adult CHD is a nascent subspecialty which is rapidly expanding in response to increasing numbers of adults living with moderate or complex CHD, typically after having undergone paediatric surgical interventions. Reference van der Bom, Zomer, Zwinderman, Meijboom, Bouma and Mulder7–Reference Marelli, Ionescu-Ittu, Mackie, Guo, Dendukuri and Kaouache9 Specialised adult CHD clinical programmes have been developed across the globe, and many now also offer dedicated adult CHD subspecialty fellowships. Reference Webb, Mulder and Aboulhosn4,Reference Baumgartner, Budts and Chessa10 A unique aspect of adult CHD subspecialty training is that fellows with both adult and paediatric cardiology backgrounds can embark in subspecialty training. Reference Warnes, Bhatt, Daniels, Gillam and Stout3,Reference Stout, Valente and Bartz5,Reference Baumgartner, Budts and Chessa10 This presents specific challenges as programmes ideally should be tailored to each fellow’s needs based on their backgrounds and experiences.

Millennials who grew up during the age of digitalisation are now embarking on subspecialty training and may have different learning styles compared to previous generations; many of them are now in the role of programme directors. Reference Turner, Prihoda, English, Chismark and Jacks11 To gain insight and facilitate effective subspecialty training, the International Society for Adult Congenital Heart Disease conducted a survey among current and recently graduated fellows on their strategies and preferences for adult CHD education.

Materials and methods

For this cross-sectional study, an online survey was created using the SurveyMonkey platform (Palo Alto, California, United States of America). This survey (see online appendix) contained questions in three domains: demographic background, institutional-directed adult CHD training, and self-directed adult CHD learning. All cardiology fellows who reported training in adult CHD (adult cardiology, paediatric cardiology, or research) were eligible for this survey. However, only current or past fellows in adult CHD subspecialty training (i.e., those who typically completed 1 or 2 year adult CHD fellowships) were asked to complete the subset of questions about institutional-directed adult CHD training and feedback. The survey link was e-mailed directly to 146 fellows affiliated with the International Society for Adult Congenital Heart Disease. In addition, the International Society for Adult Congenital Heart Disease e-mailed known adult CHD programme leaders from around the globe, who were then asked to forward the survey link to any fellows with training in adult CHD (either within or outside of a formal adult CHD fellowship). The study protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in a priori approval by the Academic Medical Center Amsterdam Human Research Committee.

The survey was completed in approximately 10 minutes and consisted of yes/no questions, categorical questions, and rating scales (1–5 Likert scale).

Statistical methods

Categorical data are reported as number and percentage and continuous data as mean with standard deviation. Rating scale questions were compared to the average rating of similar questions for each individual respondent using Wilcoxon signed ranks test. Responses based on fellows’ background (paediatric versus adult cardiology) were compared using independent sample t-test, Mann-Whitney U-test, or chi-square test, as appropriate. In cases of missing data, analyses were performed on respondents who answered individual questions (i.e., pairwise deletion). Analyses were performed with SPSS version 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York, United States of America). A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographics

A total of 75 fellows participated in the survey between March and July 2017: mean age: 34 ± 5; 35 (47%) female (Table 1). Respondents were born in 27 different countries, most commonly the Netherlands (20%), United States (17%), and India (11%). Fellows were employed/trained in 14 countries, most often the United States (28%), United Kingdom (21%), the Netherlands (19%), and Canada (11%). Interestingly, 30 fellows (40%) were employed/trained outside of their birth country. Respondents included current adult CHD clinical fellows (n = 26; 35%), individuals who had completed adult CHD clinical fellowships within the previous 2 years (n = 9; 12%), current adult CHD research-only fellows (n = 9; 12%), current adult cardiology fellows (n = 10; 13%), current paediatric cardiology fellows (n = 7; 9%), and others (n = 14; 19%), namely imaging fellows and internal medicine residents with interest in adult CHD. Of 35 current or recent adult CHD clinical fellows, 27 (77%) had adult cardiology training background and 8 (23%) came from paediatric cardiology training (Table 1).

Table 1. Institutional-directed adult CHD training.

ACHD = adult CHD; h/week = hours per week; d/year = days per year.

Institutional-directed adult CHD training

Thirty-four recent or current adult CHD fellows responded to at least one of the adult CHD-training specific questions, of whom the majority (62%) trained in 24-month or longer adult CHD fellowships (Table 1). Case-based teaching was usually (58%) considered “very helpful”, while topic-based teaching was considered “helpful” (67%); p = 0.003 favouring case-based teaching.

Self-directed adult CHD learning

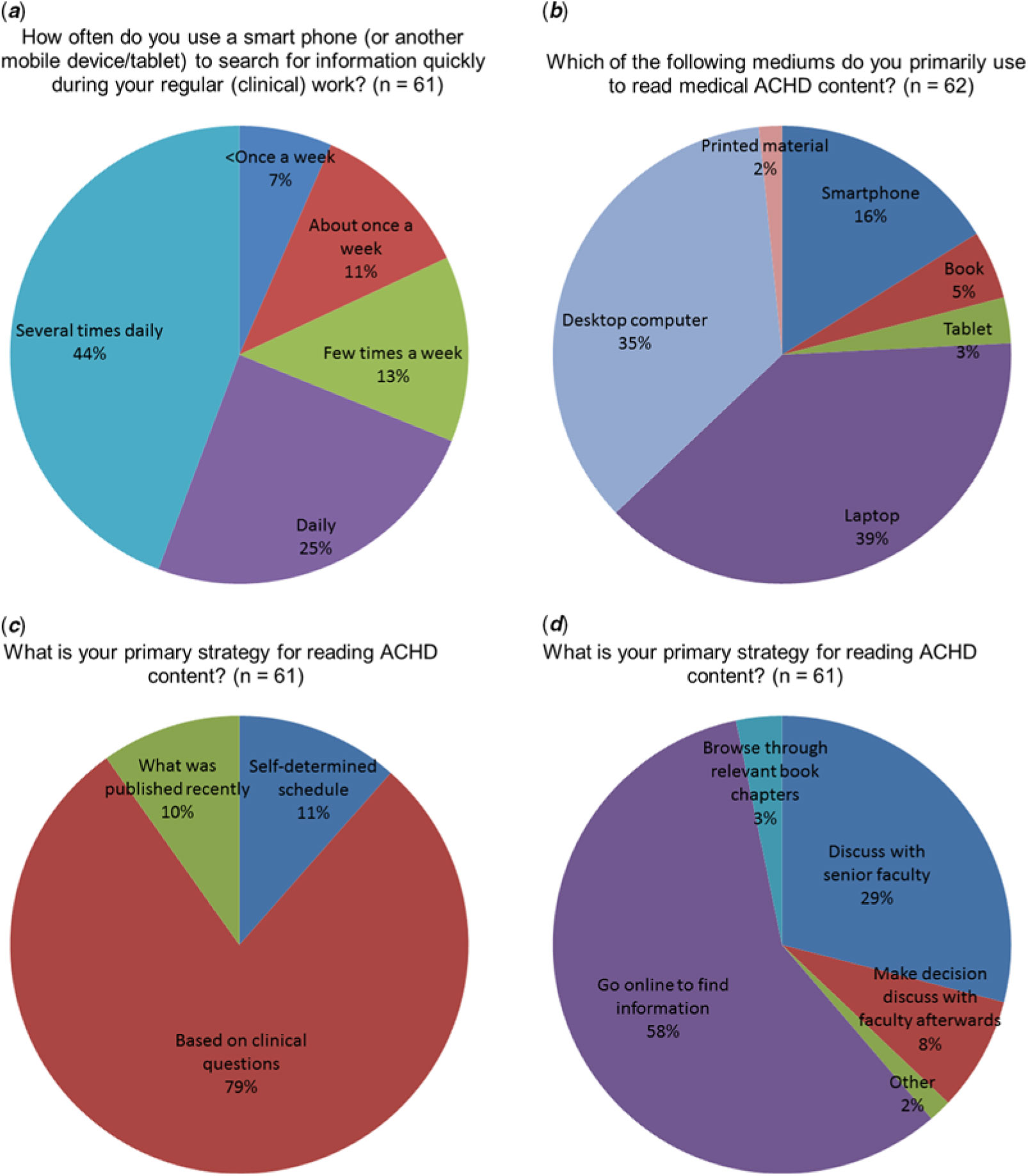

A total of 62 respondents answered questions related to self-directed adult CHD learning. Most respondents (69%) reported that they used their smartphones or other mobile devices at least once daily to quickly search for information during their regular clinical work (Fig 1a). Respondents primarily used a laptop (39%) or desktop computer (35%) to access adult CHD content (Fig 1b). The primary reason for seeking adult CHD content was “clinical questions as they arise” (79%) (Fig 1c). However, fellows with a paediatric cardiology background were more likely to read according to a self-determined reading schedule compared to those with an adult cardiology background (31 versus 5%; p = 0.04). Seventy-seven per cent of respondents would consider a recommended adult CHD reading list as “helpful” or “very helpful”, and this did not vary between those with adult versus paediatric backgrounds. Further, when faced with a non-urgent clinical adult CHD dilemma, most fellows (58%) reported that they would first search online for information on the topic. Fewer fellows (29%) reported that they first turned to faculty for consultation (Fig 1d). The specific online searching and learning resources consulted by fellows are provided in Figure 2.

Figure 1. Fellows’ preferences for learning.

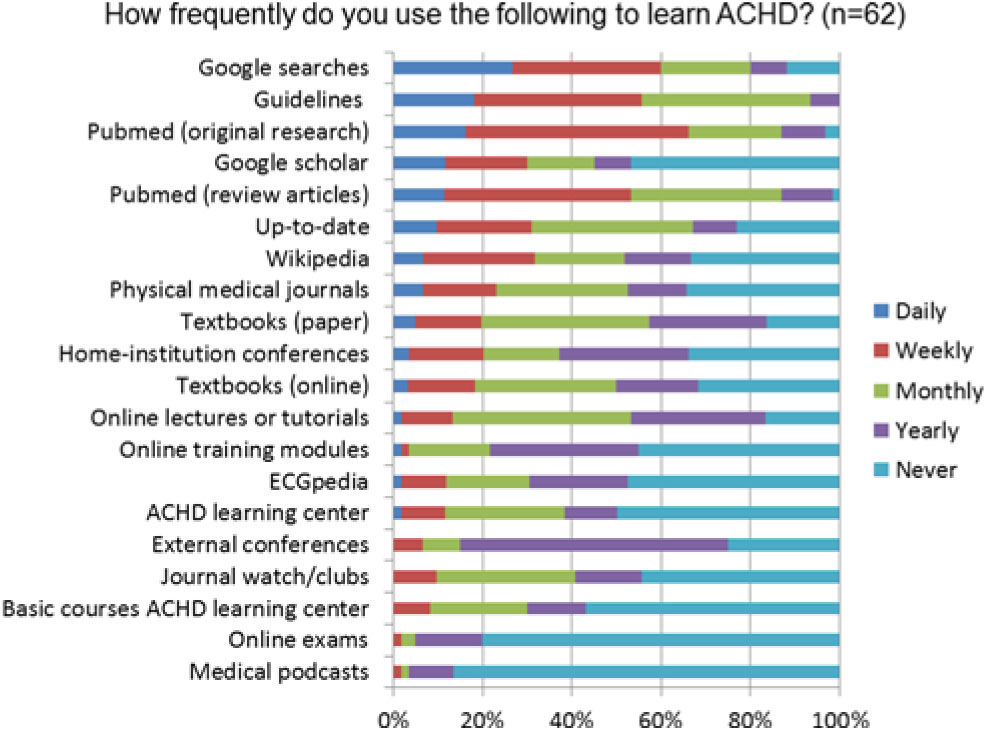

Figure 2. Resources used by fellows for learning adult CHD.

Discussion

The results of this survey indicate that a worldwide group of current and recent fellows with an interest in adult CHD preferred case-based over topic-based teaching and learning. These results may have significant implications for adult CHD fellowship training programmes around the globe.

Case-based learning

Our finding of a preference for case-based learning is similar to a prior study of medical students, Reference Srinivasan, Wilkes, Stevenson, Nguyen and Slavin12 and may have implications for the learning process during adult CHD fellowships. Previous studies revealed an effective attention span limited to 15–20 minutes during lectures, suggesting that an hour-long topic-based lecture may be less helpful. Reference Stuart and Rutherford13 Several studies suggested that case-based training is highly effective when fellows are actively engaged. Reference Sawatsky, Zickmund, Berlacher, Lesky and Granieri6,Reference Mokadam, Dardas and Hermsen14 For example, case-based training was effective in teaching arrhythmia management during residency. Reference Rodriguez Muñoz, Alonso Salinas and Franco Diez15 However, the risk with relying exclusively on a case-based approach is that some topics may be neglected when the case load is unbalanced.

Online learning

Online material was preferred over books, and smartphones were used on a daily basis to search information online. Remarkably, most fellows reported that they would first search online when faced with a non-urgent adult CHD dilemma. This clearly illustrated a preference for real-time online information and suggests most fellows are mature adult learners but might also reflect the likelihood that adult CHD faculty members are not always available for on-the-spot consultation; we did not ask for specific reasons for this preference.

However, these preferences are in line with other medical trainees and typical of the current, digitalised era. Reference Franko and Tirrell16 It should be noted, however, that smartphones have their limitations including a limited screen size, making it difficult to check references and reliability. In addition, finding clinically useful applications may be particularly challenging as applications are unregulated and few fellows received training in how to use smartphones during clinical work. Reference Wiechmann, Kwan, Bokarius and Toohey17,Reference Raaum, Arbelaez, Vallejo, Patino, Colbert-Getz and Milne18 Of note, the specific online searching and learning resources consulted by fellows were listed according to frequency of use in Figure 2, which does not have to reflect the amount of learning. For instance, many short Google searches may be performed, but the amount of information acquired during one learning session with books may be larger.

Implications for adult CHD training

We performed exploratory analyses to detect differences in preferences between adult versus paediatric cardiology background fellows. We only found as difference that fellows with paediatric backgrounds were more likely to read according to a self-determined reading schedule. Therefore, based on our survey, it is not clear whether fellows from other backgrounds should be approached differently during adult CHD training.

When taking into consideration other medical specialties as well as our own survey results, case-based, online, training strategies hold promise for adult CHD fellows, and may have more profound and long-lasting effects. Reference Srinivasan, Wilkes, Stevenson, Nguyen and Slavin12–Reference Rodriguez Muñoz, Alonso Salinas and Franco Diez15 However, risks include an unbalanced case load and the use of online resources of unknown reliability. Fellowship programmes may choose to adopt existing and reliable resources such as the Adult Congenital Heart Disease Learning Center (http://achdlearningcenter.org). These may be combined into a recommended (online) reading list which could serve as a valuable resource for adult CHD learning. These findings also provide valuable information for the International Society for Adult Congenital Heart Disease, which as an organisation has a focus on online education in order to meet the needs of members around the globe; the International Society for Adult Congenital Heart Disease may choose to prioritise opportunities for online case-based learning by providing core case-based modules. Although fellows’ preferences for online training modules may be different according to their background or experience, we believe that well-designed modules should be helpful to the large majority of worldwide fellows.

Limitations

Although this survey had a worldwide response, most fellows were employed in Western countries. The number of respondents was limited, presumably only a small proportion of worldwide fellows in training. As a result statistical power was also limited, and we therefore did not perform additional subgroup analyses comparing fellows from different countries or institutions. In addition, fellows were approached to complete the survey online; this may have resulted in selection of fellows more likely to use online resources. All fellows had an interest in adult CHD, but only half were in formal adult CHD fellowship programmes. Results cannot be generalised to individual adult CHD fellowship programmes. Finally, this survey did not assess the effectiveness (i.e., impact on knowledge or clinical decision-making) of different learning approaches for which additional studies are needed.

Conclusions

The results of this survey, in which adult CHD fellows reported a preference for case-based learning and frequent use of online resources, are relevant for the design and enhancement of adult CHD fellowships and also inform global efforts by the International Society for Adult Congenital Heart Disease for online education. Nonetheless, the results of this cross-sectional survey also highlight the need for future studies to assess changes in knowledge, attitudes, and skill by using various learning strategies in adult CHD.

Financial Support

The work described in this study was carried out in the context of the Parelsnoer Institute. Parelsnoer Institute is part of and funded by the Dutch Federation of University Medical Centers. NUTS OHRA foundation additionally provided funding for this research. This study was endorsed by the International Society for Adult Congenital Heart Disease.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Author Contributions

All authors take responsibility for all aspects of the reliability and freedom from bias of the data presented and their discussed interpretation.

Concept and design of paper: J.P.B., J.A.D., A.H.K., E.N.O., H.B., P.K., B.J.M., G.R.V. Data analysis, statistics, and interpretation: J.P.B., G.R.V. Drafting first version of the article: J.P.B. Critical revision of article: J.A.D., A.H.K., E.N.O., H.B., P.K., B.J.M., G.R.V. Approval of article J.P.B., J.A.D., A.H.K., E.N.O., H.B., P.K., B.J.M., G.R.V.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1047951119002063