On June 16, 2015, Donald J. Trump descended via escalator to the ground level of Trump Tower to announce his candidacy for President, claiming as a main qualification that “I’m using my own money . . . I’m really rich.” Across news outlets, media coverage of the announcement was remarkably consistent in describing Trump in terms of his celebrity status. The Washington Post cast Trump as a “real estate mogul and reality television celebrity” (Delreal Reference Delreal2015), The Guardian described him as a “69-year-old businessman best known for his ‘You’re fired’ catchphrase on The Apprentice” (Neate 2015), and ABC News added a third descriptor: “Donald Trump, the real estate mogul, reality television star and hair icon” (Santucci and Stracqualursi 2015). The New York Times’ lede read:

Donald J. Trump, the garrulous real estate developer whose name has adorned apartment buildings, hotels, Trump-brand neckties and Trump-brand steaks, announced on Tuesday his entry into the 2016 presidential race, brandishing his wealth and fame as chief qualifications in an improbable quest for the Republican nomination.

The rise of celebrities-turned-politicians has become more possible and likely due to changes in media systems, political systems, and political culture. Yet while this rise has been well documented and theorized, what has been less closely examined is how celebrity politicians’ bids for office are treated by the establishment press. Research on celebrity politics on the one hand and on journalism standards on the other have rarely been brought into conversation with one another. Here, we consider both perspectives in addressing the question: How did entertainment-infused politics interact with traditional journalism practices to shape how the press covered Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign?

As we will develop further, scholarly study of how journalists cover presidential elections has shown clear patterns across several decades. Among other things, this research reveals the tendency of the establishment press to winnow the field of candidates through the press’s assessment of the candidates’ respective credentials and electability. But this research has not yet accounted for the rise of celebrity politicians, who may bring a far different background, skill set, and basis for political support than traditional politicians. At the same time, the literature on celebrity politics has highlighted the increasingly influential role celebrities—and entertainment more broadly—play in politics. Yet this research has not attended to the standards and procedures of the establishment press and its entrenched influence on the political system, glossing over what can in reality be a significant culture clash between the establishment press, with its deeply engrained norms and routines for covering presidential elections, and the rise of entertainment-driven politics.

We begin our consideration of how the press covered Trump’s 2016 campaign first by contextualizing Trump’s campaign as a useful but particular test case for seeing what happens when traditional news outlets encounter a presidential campaign fully steeped in entertainment and celebrity. We then review a standard pattern in press coverage of presidential elections: the tendency to reflexively weed out candidates the press deems unelectable by giving them less coverage or less favorable coverage. Prior research would likely have predicted that Trump, who had little conventional political experience and whose name was synonymous with reality TV, World Wide Wrestling, and brand-named steaks and neckties, would have been treated to derisive, dismissive press coverage, which we refer to as “clown” coverage.

We argue that the collision of entertainment-infused politics with traditional journalism practices created a profound dilemma for the press’s ability to cover the 2016 presidential campaign coherently, and that the press responded to this dilemma by giving Trump as much clown-like coverage as serious coverage, not only in the primaries but even throughout the general election. Unable to conceptualize him as a legitimate and potentially successful contender for the presidency, the legacy press fell back time and again on dismissive and even sarcastic coverage—even as Trump’s campaign was gaining steam.

We offer support for our argument first in the form of illustrative qualitative evidence from interviews with twenty-four journalists, editors, and political strategists active in the 2016 campaign. We then present supporting data from a quantitative content analysis of the New York Times and the Washington Post. Our question is how the establishment press, particularly those well-resourced and respected news outlets that have served as the gold standard for American journalism, grappled with the highly unusual campaign Trump conducted and the highly unusual style of politics he brought into the presidential arena.

What we examine in our content analysis is not the amount, but rather the type of press coverage the Trump campaign received. Other research has documented that along with covering Trump heavily, the mainstream media covered him quite negatively (Patterson Reference Patterson2016b). We explore the nature of that negativity, uncovering a distinctive pattern that we suspect is unlike the coverage received by any major presidential candidate in recent history: A pattern of splintered (we use the term schismatic) coverage that simultaneously treated Donald Trump as a political candidate to be taken seriously and as a laughable clown. We explore this pattern not as an explanation of how Trump won, but rather as a window on how the legacy press struggled to grapple with an unconventional, celebrity-driven campaign. To the extent that the mainstream media will continue to matter in presidential elections, despite the rise of social media and alternative news sources (e.g., Nelson and Webster Reference Nelson and Webster.2017; Pew Research Center 2017, 2018), and to the extent that we can expect future celebrity politicians running for high-level offices, the 2016 election yields critical insights on how the media may cover those future candidacies.

Our content analysis results cannot make claims about how all media covered the election. As discussed further below, legacy newspapers are but one element in an increasingly complex hybrid media environment, and though most political news content is still generated by well-resourced news organizations, it is increasingly distributed and re-contextualized across a variety of other media platforms (Chadwick Reference Chadwick2013; Pew Research Center 2015). We surmise that the press’s schismatic coverage sent mixed signals to citizens about how to conceptualize and evaluate Donald Trump, signals that may have either shaped or simply echoed the electorate’s own complex reactions to a highly unconventional presidential candidate.Footnote 1 Our main purpose is to gain insight into journalistic practices, specifically the challenges serious journalists faced in covering Trump. If the fusion of entertainment and politics continues on the trajectory Trump has helped to set, how will traditional media navigate the colliding streams of traditional and celebrity politics?

Trump’s 2016 Campaign as a Particular Test Case

Although the 2016 presidential campaign provides a clear opportunity to explore what happens when the legacy media cover—and the electorate considers—an entertainment-driven presidential campaign, the Trump campaign does not provide a perfect analytical window on these questions because the 2016 election was, historically speaking, unusual.

A confluence of factors contributed to Trump’s unexpected success, not least the state of the economy (Erikson and Wlezien Reference Erikson and Wlezien.2014; Vavreck Reference Vavreck2009). Other important factors in 2016 included a Republican party that “simply did not do the things a party would do to guide voters’ preferences or limit their choices” (Masket Reference Masket2016); a two-party system that has arguably alienated many voters and laid the ground work for populist unrest (Miller and Listhaug Reference Miller and Listhaug1990; Strömbäck and Dimitrova Reference Strömbäck and Dimitrova2006); and a steady decline in public esteem for political institutions (Gallup Reference Gallup2015; Harrington Reference Harrington2017; see also Pew Research Center2014)—all this before we even get to the weaknesses of the Democratic nominee and her campaign strategy, not to mention the role of gender politics in a campaign that pivoted on traditional gender attitudes and hostile sexism (Bock, Byrd-Craven, and Burkley Reference Bock, Byrd-Craven and Burkley2017; Maxwell and Shields n.d). To this catalogue of complicating factors must also be added the role of Russian cyberwarfare (Jamieson Reference Jamieson2018), and the rising appeal of populism and authoritarianism channeling simmering racial resentments (Hochschild Reference Hochschild2016; Inglehart and Norris Reference Inglehart and Norris.2016; Wade Reference Wade2016; Walsh Reference Walsh2016).

Moreover, the role played by alternative news sources and social media networks in the surprising success of the Trump campaign (Cornfield Reference Cornfield2017; Enli, Reference Enli2017; Wells et al. Reference Wells, Shah, Pevehouse, Yang, Pelled, Boehm, Lukito, Ghosh and Schmidt2016) demonstrate how digital and social media have to some extent supplanted traditional media as a source of campaign information for voters (see Boczkowski Reference Boczkowski2016). According to one recent analysis, key segments of the Trump electorate were not tuning in much to mainstream media, attending instead to Breitbart and other popular conservative sites (Benkler et al. Reference Benkler, Faris, Roberts and Zuckerman2017), although the effect of alternative and “fake news” sources on the election should not be overstated, according to another recent analysis (Allcott and Gentzkow Reference Allcott and Gentzkow2017).

Yet this historical confluence of confounding factors notwithstanding, research strongly suggests that heavy mainstream media coverage of Trump throughout the campaign—particularly in the critical early months of the primary season—was a key factor in his ultimate success (Patterson Reference Patterson2016a, Reference Patterson2016b, Reference Patterson2016c). Several political communication scholars have argued that “the news media helped to nominate Trump” (Azari Reference Azari2016) and that Trump “drove coverage to the nomination” (Wells et al. Reference Wells, Shah, Pevehouse, Yang, Pelled, Boehm, Lukito, Ghosh and Schmidt2016).

The case of Trump is unique in another important sense that is critical to understanding not just the amount, but the type of press coverage Trump received. As we will discuss further, the genesis of Trump’s fame in a distinctive genre of reality television (along with, to a lesser degree, talk radio, cable television, and World Wide Wrestling, as well as his self-applauding books and regular stints on talk radio) made him a particular kind of celebrity politician—one with a low-brow and divisive political style, and one particularly likely to be mocked by the establishment press. Generalizing from these particulars to how the press may cover celebrity candidacies of the future may therefore be challenging. Nevertheless, how the mainstream press covered the Trump campaign offers scholars the first opportunity at the U.S. presidential level to study how legacy media norms and routines may collide with celebrity politics—even as the media’s economic incentives ensured that the media couldn’t look away from a candidate like Trump.

Crashing the Gates: Donald Trump and Celebrity Politics in the Hybrid Media Era

The Trump campaign and the challenge it posed to traditional journalism and presidential politics reflects the growing celebritization of politics, evident decades ago in politicians like John F. Kennedy becoming celebrities, and in candidates like Ronald Reagan who moved from entertainment stardom into politics (West and Orman Reference West and Orman2003). In his influential work on celebrity politicians, John Street (Reference Street2004) cites the examples of two actors-turned-governor of California—Ronald Reagan and Arnold Schwarzenegger—and former pro wrestler-turned-governor of Minnesota Jesse Ventura (to which we might add more recent examples like comedian-senator Al Franken). Street describes these as candidates “whose background is in entertainment, show business or sport, and who trade on this background (by virtue of the skills acquired, the popularity achieved or the images associated) in the attempt to get elected” (2004, 437). Barack Obama’s “global supercelebrity” standing, complete with a European tour and rock star status before he was even elected, evinced the further entwinement of celebrity and politics (Kellner Reference Kellner, David Marshall and Redmond2016; see also Marsh, 't Hart, and Tindall Reference Marsh, Hart and Tindall2010; Wheeler Reference Wheeler2013). As these various examples illustrate, “celebrity politicians” can be either career politicians who become political celebrities, borrowing the techniques of entertainment world celebrity to further their political careers, or they can be entertainment realm celebrities who trade on their fame and stage skills to enter the world of politics.

Today’s political environment is more friendly to celebrity politicians of both sorts, given that, as Kellner puts it, contemporary U.S. politics is “informed by the logic of media spectacle and thus requires that candidates become masters of the spectacle” (Kellner Reference Kellner, David Marshall and Redmond2016, 116)—a dynamic some scholars have called the “tabloidization” of politics (Kellner Reference Kellner, David Marshall and Redmond2016; Turner Reference Turner2004). But from a broader analytical perspective, a growing literature traces the rise of a style of politics in which politicians (whatever their background) “[incorporate] matters of performance, personalization, branding and public relations into the heart of their political representation” (Wheeler Reference Wheeler2013, 87). According to Marshall, celebrity politics are just one expression of the larger phenomenon of “celebrity power,” in which “the disciplinary boundaries between the domains of popular culture and political culture have been eroded” (Marshall Reference Marshall1997, xiii). The phenomenon of celebrity politics is also linked to what Turner calls “democratainment,” reflecting the mass public’s declining identification with formal political parties and institutions, and the fact that “the consumption of celebrity has become a part of everyday life in the twenty-first century” (Wood, Corbett, and Flinders Reference Wood, Corbett and Flinders2016, 594). Indeed, Street argues, “celebrity politics, and the cult of the personality that it embodies, can be seen as a product of the transformation of political communication” (Street Reference Street2004, 441). This transformation, however, has not been consistently recognized in the mainstream of political communication research.

For its part, the political communication literature has identified the evolution of a “hybrid media system,” in which new media platforms and logics compete but also interact with traditional media. In this evolving media ecosystem, older forms of media exist alongside newer invasive species of media, the two sometimes struggling for dominance but both contributing to the news and information flows that shape politics (Chadwick Reference Chadwick2013). A defining feature of this evolving system is what Baym refers to as “discursive integration,” in which the markers dividing news from entertainment are becoming increasingly hard to discern (Baym Reference Baym2005). This transformation has created unprecedented opportunities for nontraditional figures to enter politics, particularly those who understand entertainment-derived values and aesthetics. A variety of actors now traverse the increasingly porous boundaries between traditional and entertainment-driven politics, across an increasing variety of media platforms (Lawrence and Boydstun Reference Lawrence, Boydstun, Walgrave and Van Aelst2017). In today’s mash-up media environment, “politically relevant” media include everything from comic strips and YouTube videos to Hollywood movies and, yes, reality TV shows (Baym Reference Baym2005; Williams and Delli Carpini Reference Williams and Delli Carpini2011). And ultimately, some scholars argue, the performative aesthetics and affective attachments between celebrities and “fans” that are more familiar to the world of entertainment are increasingly the basis for political representation as well (Street Reference Street2004; van Zoonen Reference van Zoonen2005).

While both literatures shed light on the changes in media and politics that made his campaign possible, Donald Trump presented the legacy press with a stark new version of celebrity politics, both in terms of his pre-established fame and (alleged) fortune when he entered the presidential arena, and in terms of his particular pathway to and style of celebrity. When he entered the 2016 presidential race Trump was already an entertainment household name (think: 14 seasons as host of The Apprentice). A Gallup survey of registered Republicans in July 2015, shortly after Trump announced his campaign, found that 92% recognized his name, compared with 81% who recognized the name Jeb Bush (son and brother to two former U.S. presidents), not to mention Ted Cruz (at 66%), and Marco Rubio (at 64%) (Dugan Reference Dugan2015). Trump’s name recognition was also likely due in part to his frequent coverage on FOX News prior to the election and to the increasingly tight bonds between that network and the Republican voter base. (As one journalist who has covered FOX closely recently observed, “Trump is the logical extension of the takeover of Republican party by television and entertainment” [National Public Radio 2018].)

Trump’s experience with the genre of reality TV was particularly important to this performative style. Not only did The Apprentice increase Trump’s name recognition, but the show’s casting calls in cities around the country—particularly in the South and Midwest—gave Trump, who assiduously attended these events that were described as record-breaking by the show’s producers, practice in the skills of campaigning (Frontline Reference Frontline2016). Although the show was for much of its run not as highly rated as Trump has often suggested (Bradley Reference Bradley2017), it helped him hone his unique style, skills bolstered by his numerous appearances on talk television and radio, and pro wrestling events.

Reality TV mattered for the unique case of Donald Trump in another way as well. Research suggests that for heavy viewers of the genre, watching reality TV involves a negotiation of what is “real” and “not real” about such programs. The pleasure in viewing reality TV hinges in part on the tension between the apparent spontaneity and authenticity of happenings within a show and the viewers’ sense that the show is still scripted—what Rose and Wood describe as “contrived authenticity” (Baruh Reference Baruh2010; Rose & Wood Reference Rose and Wood2005). This reality TV aesthetic seems particularly conducive to Trump’s political style—not just the daily installments of new drama but also the bombastic, winking showmanship and frequent crossings into hyperbole and fakery.

As Street observes in a recent essay, “celebrity performances are shaped by the conventions of the genre from which they emerge” (Street Reference Street2017, 16). For Trump, reality TV sharpened a performative style that is particularly aggressive, brash, iconoclastic and, some would say, mean-spirited, encapsulated in the pithy one-liner he inevitably uttered in each episode of The Apprentice: “You’re fired!” For his fans, Trump’s performative style may serve as a proxy for a style of political representation and leadership for which they yearn (Street Reference Street2017, 18).

And that style is key to understanding the challenge Trump presented for journalists. Even more than his lack of previous political experience, Trump’s transgressive political performance sets him apart from predecessors—particularly, his refusal to adopt and adapt to prevailing norms of presidential politics. Previous entertainers-turned-politicians like Reagan and Schwarzenegger shifted from entertainment to politics by rebranding themselves as more or less conventional politicians. Trump deviates from this pattern by continuing—even as president—to behave as an entertainer, “reformulat[ing]…politics as reality TV entertainment” (Schäfer-Wünsche and Kloeckner Reference Schafer-Wunsche and Kloeckner2016, 2). For a swath of American voters, Trump’s roots as an entertainer and, as Forbes once put it, a “business illusionist” (Lappin Reference Lappin2011) proved to be a powerful source of his appeal. Indeed, being an “outsider” was one of the most defining aspects of Mr. Trump’s support among voters (Huang and Yourish Reference Huang and Yourish2016). Although politicians have long succeeded by claiming to be Washington outsiders, Trump is “the first major U.S. presidential candidate to pursue politics as entertainment and thus to collapse the distinction between entertainment, news, and politics, greatly expanding the domain of spectacle” (Kellner Reference Kellner, Armano and Briziarelli2017, 6, emphasis added).

In his examination of the Trump phenomenon, Street observes that Trump “is not a ‘politician’ . . . because he fails to meet the standards expected of a democratic representative [and] expresses no desire to be such a figure” (Street Reference Street2017, 7–9). Indeed, Street argues that Trump must be understood primarily in terms of entertainment, not politics: That Trump is a celebrity first and foremost.

Guarding the Gates: The Legacy Press and Traditional Presidential Politics

Trump’s candidacy, unlike any previous U.S. presidential campaign in the degree to which it was saturated with and driven by entertainment aesthetics and the extent to which it flouted norms of traditional presidential politics, offers an extreme test of how the press reacts when celebrity and conventional politics collide.

One way we might expect that clash to manifest is by examining whether and how the press attempted to “winnow” Trump from the candidate field. As a long line of research has demonstrated, an important structuring feature of presidential elections are the press’s decisions about which candidates are “unserious” or “unelectable” and therefore deserving of less coverage, less favorable coverage, or both. This media handicapping of candidates during the all-important primary phase of a presidential election, when news outlets have to decide which contenders among many to devote their limited resources to covering, can influence candidates’ visibility and, thus, electability (Belt, Just, and Crigler Reference Belt and Crigler2012; Haynes et al. Reference Haynes, Gurian, Crespin and Zorn2004; Matthews Reference Matthews and Barber1978; Patterson Reference Patterson1994; Reference Patterson2016a). In the absence of objective criteria of presidential readiness, the establishment press act as gatekeepers of “electability.”

The literature on journalistic winnowing suggests two main winnowing triggers. First, candidates who lack name recognition, struggle to attract donors, or fail to gain ground in public opinion polls and primary contests are generally subject to winnowing. The press sees these candidates as “likely losers,” and coverage of these candidates is usually less positive, less frequent, or both. By the same token, candidates who are polling well deserve more coverage, journalists reason, because voters are clearly more interested in those candidates and thus they are more likely to win anyway (Hopmann, Van Aelst, and Legnante Reference Hopmann, Van Aelst and Legnante2012; Patterson Reference Patterson2005).

Second, candidates whose background, political views or personal demeanor seem outside the norm, or “unpresidential”, are also subject to winnowing. In particular, the press may deem some candidates not ready for the klieg lights of the presidential stage because of high profile campaign trail gaffes—from Edmund Muskie’s 1972 press conference in which he appeared to cry while defending his wife against politically-motivated attacks, to Howard Dean’s “scream” at an Iowa post-caucus event, which, although not the only factor in Dean’s demise, helped cement journalists’ impression that he was not ready for the presidential stage (Hindman Reference Hindman2005; Patterson Reference Patterson1994). Post-gaffe, candidates can find their media coverage and their campaign chances shift as a narrative of unelectability takes hold.

Most often, historically speaking, candidates who seem unpresidential and thus unelectable are the same candidates who struggle to gain ground at the polls. Think, for example, of Herman Cain’s 2012 campaign, which featured both a struggle to gain electoral steam and a candidate given to unconventional and sometimes unintelligible statements. In other words, the two dimensions of “unelectability”—and the press’s two main winnowing triggers—tend to co-occur. Campaigns featuring gravitas- and poll-challenged candidates, such as the 1992 presidential bid of Democrat Larry Agran, whose highest office held before seeking the presidency was mayor of Irvine, CA, can find themselves figuratively or even literally written out of campaign coverage (Meyrowitz Reference Meyrowitz and Kendall1995).

But public perceptions of presidentialness and electability may be shifting, perhaps shifting sharply, as politics becomes more influenced by celebrity and entertainment, as reviewed earlier, leaving the press in a more uncertain position vis-à-vis their winnowing power. The 2016 election thus presented a sharp and unique test of the press’s two main winnowing criteria: What to do when a profoundly unpresidential candidate (by traditional measures) enters the presidential stage, bringing with him an established brand name, high entertainment value, and an audience from beyond the political arena—and thus a real chance of being elected?

The literature reviewed earlier would likely have predicted that the press would write off a brash political novice and self-aggrandizing celebrity like Trump—much like the examples found in coverage of Trump’s campaign announcement—particularly since, according to some accounts, Trump’s campaign staff were signaling to journalists that the candidate himself did not expect, nor even set out, to win (Wolff Reference Wolff2018). But Trump’s celebrity status and his entertainment-driven campaign, unseemly or laughable as it may have been to journalists accustomed to more traditional candidacies, posed a deep dilemma: If one key threshold for defining a “serious” presidential candidacy is the candidate’s name recognition, not to mention their ability to self-fund their campaign, then Trump—long a household name and a self-reported millionaire—perhaps had to be taken seriously as an electoral contender. A show business candidate, fueled by his own celebrity and dismissive of the traditional rules of politics, posed a new challenge for legacy media.

As the data we present will suggest, the press’s urge to write off Trump persisted alongside Trump’s high entertainment value, which prompted media outlets to give him high amounts of coverage. News routines that took shape in an earlier era in the evolution of the American political and media systems did not adequately equip journalists to cover the unconventional entertainer-turned-candidate Trump. Traditional journalistic practices proved insufficient to the task of alerting the public to what seemed like a reality show but what would turn out to be an effective populist political campaign.

The Journalistic Conundrum of 2016: Treat Trump Seriously or as a Joke?

The literature reviewed earlier suggests that Donald Trump imported a particular style into presidential politics in a way that hasn’t been seen before in the United States. It is as if two enormous currents—the inertial force of the press corps’ standard modes of covering elections, and the potent, transformative rise of entertainment culture—collided in the 2016 election.

This challenge was likely deepened by what social psychologists call “functional fixedness”: once an object is conceptualized in a certain way, it is difficult to re-conceptualize (e.g., Dunker Reference Duncker1945). In Trump’s case, because journalists conceptualized of Trump predominantly as an outlandish TV host and shady business mogul when he entered the presidential race in 2015, it was surely difficult to re-conceptualize him as a politician who could win the presidency—an assumption that at key moments in the campaign was reinforced by polls suggesting the Trump campaign was a longshot. Trump’s target audiences, meanwhile, possibly because they conceptualized him primarily as an entertainer or a political outsider, gave him greater license for incendiary comments and unconventional behavior. Journalist Salena Zito of The Atlantic recognized this dynamic as she covered the Trump campaign, famously quipping that, “the press takes [Trump] literally, but not seriously; his supporters take him seriously, but not literally” (Zito Reference Zito2016).

The challenge was further deepened by the entertainment value, and therefore the commercial value, Donald Trump’s candidacy offered to the media, particularly on cable TV news. Contemporary commercial imperatives for news organizations create strong incentives to make political news more entertaining (Dunaway Reference Dunaway2011; Entman Reference Entman2010; Iyengar, Norpoth, and Hahn Reference Iyengar, Norpoth and Hahn2004; Picard Reference Picard2004). In that context, the Trump campaign seems to have offered the media an ideal formula of daily revelations, controversial statements, tweets, gaffes, and so on that fueled ratings. As Patterson contends, “Trump met journalists’ story needs as no other presidential nominee in modern times” (Patterson Reference Patterson2016c)—particularly at CNN, where, according to one report, the Trump campaign offered “the biggest story we could ever imagine” (Mahler Reference Mahler2017). The reported comments of then president and CEO of CBS, Les Moonves, also confirm that incentive: A campaign dominated by coverage of Donald Trump “may not be good for America,” Moonves reportedly said, but “it is damn good for CBS . . . . The money’s rolling in and this is fun . . . . Bring it on, Donald. Keep going” (quoted in Crovitz Reference Crovitz2016). During the primary campaign alone, Trump received an estimated $2 billion in “free media” (Confessore and Yourish Reference Confessore and Yourish2016).

Thus, while Trump’s celebrity and his brash performative style worked to his advantage in many respects, it left journalists with a profound dilemma. Because the press fundamentally conceptualized of Trump as a celebrity, not a politician (and not a celebrity-turned-politician, since he never “played the part”), and because he offered ongoing newsworthiness and the promise of ratings gold, journalists were not well prepared to handle the conundrum of how to cover him. Whereas the press would have had no conundrum in giving serious coverage to a traditional candidate running a thinly-veiled racist and misogynistic campaign, we expect it was all too easy to treat Trump’s reality TV-shrouded campaign as a joke.

This dilemma might easily be obscured by analyses showing that media coverage of Trump’s campaign was highly negative throughout the election (Patterson Reference Patterson2016c). But the nature of that negativity—frequently dismissive, jokey, snarky—was distinctive. The underlying assumption that Trump was not to be taken seriously was reflected in The Huffington Post’s decision in July 2015 to put all its coverage of the Trump campaign in its Entertainment section. “If you are interested in what The Donald has to say,” the Post wrote, “you’ll find it next to our stories on the Kardashians and The Bachelorette” (Grim and Shea Reference Grim and Shea2015). By December 2015, however, the Post reversed that decision; in a piece titled “We are no longer entertained,” founder Ariana Huffington described Trump’s campaign as “an ugly and dangerous force in American politics” and promised that her outlet would put Trump back in the “politics” category (Huffington Reference Huffington2015).

Importantly, the press’s conundrum about whether to treat Trump as a politician (taking him seriously) or as a celebrity ill fitted for the presidential stage (treating him as a joke) was orthogonal to their estimates of Trump’s electoral chances. That is, winnowing theory would probably predict that Trump’s campaign would be written off to the extent that his polling numbers weren’t strong (Belt, Just, and Crigler Reference Belt and Crigler2012; Haynes et al. Reference Haynes, Gurian, Crespin and Zorn2004; Matthews Reference Matthews and Barber1978). But even at the beginning of the primaries, when Trump’s polling numbers were low, journalists found him impossible to ignore.

Once the primary season was over and Trump had clinched the Republican nomination, the question of winnowing primary candidates was no longer relevant and the journalistic conundrum deepened. Past research shows that during a general election, the press’s “balance” norm tends to govern coverage such that both parties’ candidates receive roughly equal coverage, though the precise “balance” varies with electoral contexts (D’Alessio and Allen Reference D’Alessio, Dave and Allen2000). In keeping with that pattern, in 2016, “week after week [Trump] got more press attention than did Clinton” (Patterson Reference Patterson2016c). But the precise nature of that coverage is distinctive. As the following evidence suggests, in the waning days of the 2016 general election, journalists continued to treat Trump as a joke, a clown, even with the increasing imperative to treat him seriously as the Republican nominee.

Evidence from Interviews

We began exploring this conundrum by considering the insights of people with a view behind the press’s curtain, obtained through interviews the lead author conducted, along with political scientist Peter Van Aelst, with twenty-four journalists, editors, and political strategists who were active in the 2016 campaign. To conduct these interviews, we contacted a range of political journalists and strategists active in the media sector, including national-level journalists (e.g., New York Times, US News & World Report, NPR), journalists with leading regional newspapers (e.g., LA Times, Sacramento Bee), foreign correspondents (e.g., The Guardian), consultants, and ghostwriters. During each interview, we asked for the contact information of relevant colleagues. We then contacted those people in turn, resulting in a non-random but diverse snowball sample of interviews. All interviews were conducted between April and September of 2017 (within ten months of the 2016 election).Footnote 2

For our purposes here, we examined the interview transcripts for any discussion of the press’s treatment of Trump vis-à-vis his celebrity status. The selected quotations below are representative of the relevant comments interviewees made. Our interview data illustrate, first of all, that even though many journalists did not take the Trump campaign seriously, they felt compelled to cover it. As Mike McPhate of The New York Times described it:

[Trump] comes with a sort of baked in news value as a public person. So any time you’re weighing whether or not to do a story, there are certain considerations. Is this a public person, is it salacious, is it local, is there public interest involved, how many people are affected, et cetera, et cetera. And he’s got one of those locked up, which is that he’s famous. You cover famous people because they’re famous (McPhate Reference McPhate2016).

The U.S. press was not alone in thinking of Trump as a joke. An editor and reporter for The Guardian, Martin Pengelly, explained the amount of news coverage Trump received this way:

It was the uniqueness of his campaign, the just all-encompassing thing that was happening . . . . He got more air time than anyone else, but that’s because it was so unusual and ridiculous. As far as I can see, he just demanded it, because it was a movement. I think maybe that’s hindsight, because all the way through, the argument was, “He’s a circus act, why are you giving him this space?” Now, you can say it was a movement. It was a surge. Did we think it was a movement? No. None of us thought he’d win (Pengelly Reference Pengelly2017).

The interviews also revealed how Trump’s refusal to play by the standard political playbook left journalists flummoxed. One veteran national newspaper reporter described the slow process of realizing Trump could “get away” with saying things that other politicians could not:

It was apparent pretty early that the rules had changed . . . [When Trump] made those comments about Megyn Kelly and we all shook our head and said, “Oh, that’s it, he’s done.” Because in the past, I mean, my goodness, somebody made a statement like that, that was it. Plus, he didn’t have any party backing, he wasn’t an insider, and yet he not only survived, but he thrived . . . . There was always this element of surprise about his campaign. The rules didn’t matter. And that continued right on up to the end (Anonymous B 2016).Footnote 3

Political consultant Kevin Eckery described this collision between press standards and entertainment from the perspective of journalists and press outlets doing everything they were supposed to do as individual agents, yet suffering a “system failure” in the aggregate:

Everybody who was following the Trump campaign was following the rules. There was some great journalism. . . . Lots of people did really good work. But, even though a lot of people did really good work, and even though everybody followed the rules, you still had a situation where just that overwhelming volume of Trump access to the media had its own weight. Because, he was bringing his own brand to this. . . . Just the fact that he was out there, so that people can be reminded of his brand, which is brash, successful, rich business man, was good enough. That’s all it took (Eckery Reference Eckery2016).

As some interviewees observed, the end result was that Trump was treated to different coverage than his general election opponent. One White House correspondent told us:

I think that at times, broadly, the American press covered Hillary Clinton as if she were already president. They held her to a very high standard because she could become President of the United States, and I think at times, Donald Trump was not held to the same standard (Anonymous A 2016).

These themes in our interviews were echoed by other reporters who covered election 2016. The performance staged by the Trump campaign was so unconventional, so seemingly risky and beyond the pale that, as Susan Page, Washington bureau chief for USA Today, put it: “You watch Trump, it’s like a high-wire act, you want to see what he’s going to say next, and will he fall off.”Footnote 4 And for at least some reporters on the scene, it was difficult to convey through traditional journalistic means just how unconventional the campaign was. As Alec MacGillis, politics reporter for ProPublica put it, “What the press wasn’t able to do, and what it was almost not set up to do, was to get across the sheer ridiculousness or surreality of Donald Trump running for president.”Footnote 5

Content Analysis Methods and Data

For a more explicit and quantitative test of the idea that the legacy press treated Trump as much as a “clown” as a serious politician throughout the campaign, we examined the press coverage given to Trump in two leading newspapers: the New York Times and the Washington Post. We examined these legacy newspapers, rather than television news for example, because we suspect that while the collision between traditional standards of journalism and Trump’s entertainment trappings also played out on TV—especially cable television, with its more urgent entertainment imperatives—the Times and the Post offer a hardest test case: If any news outlets would be able to navigate that collision skillfully, resisting the urge to dismiss Trump through “clown” coverage, especially as Election Day neared, it would be newspapers such as these that are well-resourced and whose reputation relies on serious journalism.

We examined coverage of Trump’s campaign in these two newspapers at eleven key moments in the campaign, selected after consulting multiple retrospective accounts of the 2016 election (e.g., Guardian Reference Guardian2016; Reuters Reference Reuters2016). These moments capture a mixture of events that reflected either traditional key moments in any election (e.g., passing the delegate threshold) or moments involving highly controversial Trump statements, aiming for a rough distribution of moments across the course of the campaign. Some of the moments reflected relatively well on Trump, others reflected more poorly, but all were major events in some way. We cannot claim these were necessarily the largest or even most important events of the campaign, but they are certainly among them. Specifically, we examined all New York Times and Washington Post stories, both straight news articles and editorial and op-ed pieces, about Trump during the 48 hours following each of the following key moments:

• Trump’s announcement of his campaign (June 16, 2015)

• The first GOP debate, notable not only as the first candidate forum but also for the altercation between Trump and Fox News host Megyn Kelly (August 6, 2015)

• Trump’s call for a travel ban on Muslims (December 7, 2015)

• The Iowa caucuses, where Trump came in second to Ted Cruz (February 1, 2016)

• Super Tuesday II, when Trump won Florida, prompting Marco Rubio to quit the race (March 15, 2016)

• The subsequent exit of Trump’s other close rivals, John Kasich and Ted Cruz (May 3, 2016)

• Trump’s attainment of the requisite delegate threshold (May 26, 2016)

• Public reaction to Trump’s slurs against the parents of slain U.S. soldier Humayun Khan (August 1, 2016)

• The first debate between Trump and Hillary Clinton (September 26, 2016)

• The release of the Access Hollywood tape (October 7, 2016)

• FBI Director James Comey’s announcement that the bureau would re-open its investigation into Hillary Clinton’s emails (October 28, 2016)

Our data comprised articles that appeared in print (both hard news stories and editorials/op-eds) as well as online-only items (blog posts), producing a total of 1,517 in-print and online-only stories. Although blog posts comprised 72% of the articles in our study, the findings are strikingly similar for print and non-print stories, with no major substantive differences, and so we analyze print and online articles together.

We trained undergraduate students to code each story for four variables that offer direct insight into the question at hand.Footnote 6

• The overall tone of the story in portraying Trump (ordinal: positive, neutral, negative)

• The overall tone of the story in portraying Trump’s electoral chances for the race the story was discussing, be it primary or general (ordinal: positive, neutral, negative)

• Whether the story treated Trump as a “serious” political candidate (binary: 1, 0)

• Whether the story treated Trump as a “clown” (binary: 1, 0)

The “overall tone toward Trump” variable offers face validity of our data, as it has been used in previous studies of the 2016 election. The “overall tone of Trump’s electoral chances” code allows us to test the argument that the press’s serious versus clown treatment was not necessarily in line with their estimations of his electoral chances. The final two codes (“serious” and “clown”) allow the most direct test of our argument that the press reacted to the conundrum of how to cover the Trump presidency through schismatic coverage. The “serious” code was used for articles giving substantive consideration to Trump or his campaign with discussion of the possible benefits or drawbacks of a Trump administration. Treating Trump seriously could take several forms, ranging from descriptions of the potential positive foreign policy implications of a Trump administration to discussion of Trump’s campaign as a potentially serious threat to democratic norms. The “clown” code was used for stories that explicitly used dismissive, sarcastic, and/or demeaning descriptors to describe Trump. Treating Trump as a clown included disparaging his persona, as in stories that described him as “Donald the Doofus,” a “ meandering fluff-head,” a “doughy showman,” a “celebrity bomb-thrower and provocateur,” or a “TV caricature.”

We intentionally treated the “serious” and “clown” codes as mutually-exclusive, with the aim of tracking the predominant signal audiences would have received from each article. According to the coders and our own examination of the data, there were almost no instances of a story that could have conceivably been coded as both “serious” and “clown” (had our coding allowed for such double coding). Importantly, note that the “electoral chances” variable was distinct from the “serious” and “clown” variables. Stories coded as “serious” or as “clown” could portray Trump’s chances positively or negatively (or not at all).

For a richer view of how these dueling treatments of Trump played out, we offer some examples from our data—sometimes in the words of journalists themselves or of the sources they quoted in hard news stories, sometimes in the words of editorials and op-ed pieces. Examples of “serious” coverage, meaning coverage that might reflect positively or negatively on Trump but that engaged with him substantively as a presidential candidate, include the following, presented chronologically:Footnote 7

• “It’s disturbing that someone with so little interest in the truth, who is happy to stoke xenophobic fires to advance his cause, and who seems to have little cause other than the glorification of himself, has somehow persuaded so many on the right that his presidency would make America great instead of be a disaster . . . . I don’t doubt the good faith of Trump supporters . . . . The answer isn’t to elect a ‘strong man’ who will find unnamed ways of forcing his views upon others. That’s a dangerous path, and it’s not one that the Constitution envisions or experience recommends.” (December 7, 2015)

• “The plain truth is that a Trump presidency would not only fracture American society along ethnic, racial and, we now know, religious lines. It would also demolish American prestige on the world stage and alienate our most important allies.” (December 8, 2015)

• “Trump is filling a vacuum left by years of inattention to voters who have been patronized and taken for granted. The fissures he exposed in the GOP will not go away.” (May 2, 2016)

• “His evident lack of any kind of self-control has ominous implications for how he would respond as president and commander in chief to real crises and emergencies.” (August 2, 2016)

• “For so many of us, this is the first time in our lives that we are forced to question whether our country will remain free and democratic if a major-party candidate wins.” (August 2, 2016)

• “From this point of view, when Trump opened his first debate against Clinton with a critique of Chinese and Mexican trade and then continued into a detailed discussion of currency manipulation, taxes on exported goods and other technical issues related to international commerce, it was not the specific issues he was discussing that mattered. Rather, what Trump communicated to his supporters was his worldview and his sense of American identity.” (September 27, 2016)

As these quotes illustrate, “serious” coverage of Trump took several forms, including critiques of Trump’s policy positions, concerns about his ability to govern, and the implications of his candidacy for democracy, red flags about his divisive statements, and also recognitions of the appeal of his candidacy for voters.

Examples of “clown” coverage that engaged with Trump as the butt of a joke include the following:

• “Donald Trump entered Iowa as a big-talking strip of New York sirloin. He exited as a second side order of high corn. Still, he remains undiminished as satiric red meat. The steely knives of America’s political cartoonists are close by, primed for serrated illustration.” (February 3, 2016)

• “Before he left the race, Senator Ted Cruz shared a parting thought: ‘If anyone has seen the movie Back to the Future, Part II, the screenwriter says that he based the character Biff Tannen on Donald Trump—a caricature of a braggadocious, arrogant buffoon who builds giant casinos with giant pictures of him wherever he looks.’ (It is, indeed, true that Mr. Trump served as inspiration for the character.)” (May 5, 2016)

• “Donald Trump should be a late-night comedian’s dream—a bombastic reality TV star running for president with a distinctive vernacular (‘yuge,’ ‘loser’) and physical features (hair swoop, suspicious tan) that practically write their own jokes.” (May 27, /2016)

• “If you admire a good story, fine, but why hire an amateur like Trump? Why not J.K. Rowling, who gave us Harry Potter? This would get millions of young people interested in politics, which could use some wizards and special effects, Supreme Court justices flying through the air, robes fluttering.” (September 27, 2016)

• “With his flights of fancy and bouffant of weirdly styled hair, he now seems to be more desperate Bond villain than presidential contender.” (October 28, 2016)

Content Analysis Findings

Our content analysis shows the same high levels of negative coverage of Trump that other analyses reveal (Patterson Reference Patterson2016a, Reference Patterson2016b, Reference Patterson2016c), offering face validity to our data (see Appendix). Our purpose here, however, is to examine the idea that the press covered Trump in a disjointed fashion—sometimes taking him seriously, sometimes treating him as a clown, in ways that cannot simply be explained by their estimation of his electoral chances at the given moment.

We begin with figure 1, which shows the percentage of each moment’s coverage that treated Trump as a “serious” candidate and the percentage that treated him as a “clown.” This figure offers a direct demonstration of our argument that the journalistic conundrum we have described led the press to cover Trump in a schismatic fashion. We see that, at least in these two leading newspapers, coverage was nearly evenly divided between the two modes of coverage. Moreover, the tension between these two versions of Trump in the press was never reconciled, even as Trump secured the GOP nomination. Instead, we see a nearly even give-and-take, with the press framing Trump seesaw-style as someone to laugh at and someone to heed throughout the remainder of the election season.

Figure 1 Coverage of Trump as presidential material vs. clown

As noted earlier, there were no significant differences (at least with respect to the variables we consider here) between print and non-print (i.e., blog) coverage. Overall, 16% of print articles and 19% of non-print articles were coded as treating Trump “seriously.” A two-sample t-test confirms that this difference is not statistically significant (p = 0.242). Likewise, 17% of print articles and 15% of non-print articles were coded as treating Trump like a “clown”—a non-significant difference (p=0.526).

Given how colorful some of the language describing Trump is in the examples provided here, it seems plausible that the “clown” coverage appeared primarily on the editorial pages rather than in “straight” news stories. To explore this possibility, we further divided the articles into editorial/op-ed content and non-editorial content (including everything from Page A1 articles to features stories). Here, we find further evidence of the journalistic conundrum. We might have expected non-editorial content to contain more “serious” coverage, while expecting editorial content, where journalists are freer from strict objectivity norms, to contain more “clown” coverage. However, 23% of editorials were coded as “serious” compared to 13% of non-editorials (a statistically significant difference, p=0.017). And 24% of editorials were coded as “clown” coverage compared to 14% of non-editorials (again, a statistically significant difference, p=0.010). In other words, while dismissive coverage of Trump was more likely on the editorial pages, more serious coverage of Trump was found there as well, while clown coverage was sprinkled throughout “straight” news stories as well as editorials.

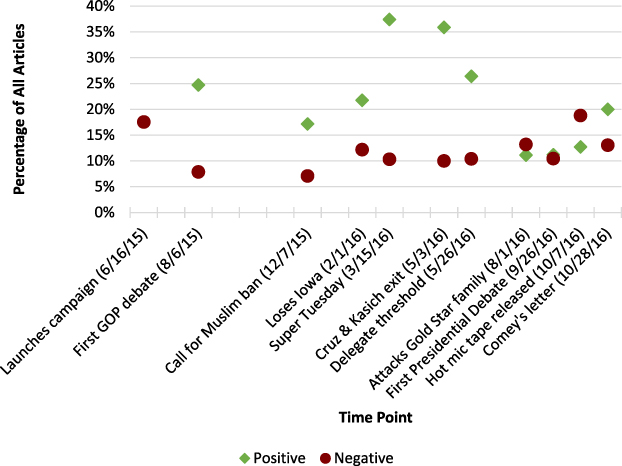

Figure 2, displaying the percentage of each moment’s coverage that cast Trump’s electoral chances in a positive or negative light, supports our argument that disjointed press coverage of Trump (as figure 1 documents) reflects the collision of journalism standards with celebrity aesthetics, rather than the press simply not thinking Trump had a chance of winning. We see here that even as Trump passed the delegate threshold in late May, press portrayals of his electoral chances became less positive—presumably as the press looked ahead toward the general election. When Trump attacked the Gold Star Khan family during the Democratic convention, these newspapers’ assessments of his electoral viability dropped sharply, recovering only when FBI Director James Comey released his letter a week before Election Day announcing the re-opening of the Hillary Clinton email investigation. And even though this development gave Trump an unexpected late-game advantage, media coverage of his chances became only slightly more positive than negative.

Figure 2 Coverage of Trump’s electoral chances

Note: Data includes signals about Trump’s positive/negative electoral chances for the GOP primary (prior to the reaching the delegate threshold) as well as his electoral chances for the general election (throughout).

We can test the idea that “serious versus clown” coverage was orthogonal to “positive versus negative electoral changes” more directly by looking at the co-occurrence of “positive electoral chance” codes (figure 2) with “serious” codes (figure 1) and, likewise, at the co-occurrence of “negative electoral chance” codes (figure 2) with “clown” codes (figure 1). The story-level correlation of positive electoral chance codes with serious treatment codes is a mere 0.16, and the story-level correlation of negative electoral chance codes with clown treatment codes is 0.11. Regardless of the press’s fluctuating estimates of Trump’s chances of winning the presidency, press coverage was schismatic between serious and clown portrayals.

Conclusion: Trump, Celebrity, and the Future of Celebrity Presidential Campaigns

We have focused here on the extreme test Trump’s campaign offers to theories of traditional presidential politics—specifically, how the press responds when faced with a celebrity candidate whose performative style is deemed highly unpresidential. We have argued that entertainment-infused politics collided with traditional journalism practices in 2016, creating a profound conundrum for the press’s ability to cover Trump’s presidential campaign. We show that leading legacy newspapers did not or could not resolve that conundrum in such a way that offered consistent cues to their readers, producing the disjointed conceptualization of Trump illustrated in the examples and figures provided here.

We find that press coverage of Trump’s candidacy veered between serious coverage and dismissive coverage during not only the primary but also the general election. That the press continued to print dismissive coverage of Trump even throughout the general election season suggests that journalists and political scientists alike must re-orient themselves to the role of entertainment in modern politics in order to account for the very real seriousness of celebrity candidates, given the rise of entertainment values and aesthetics as a mode of politics and political representation (Kellner Reference Kellner, David Marshall and Redmond2016; Street Reference Street2004; Turner Reference Turner2004; van Zoonen Reference van Zoonen2005).

This schismatic coverage was problematic, we contend, because every news article and editorial that dismissed Trump as a joke sent a signal to voters. We can imagine that, for liberals, each dismissive article signaled permission to also dismiss Trump. For conservatives and other potential Trump voters, it signaled confirmation of their suspicions of liberal media bias. And overall, it sent mixed signals about how to conceptualize and evaluate Trump. Again, we cannot know how this dismissive coverage might have affected voters, or to what degree it was a cause or a reflection of the public’s own highly ambivalent reaction to Trump’s campaign (Jones Reference Jones2016). But the signals themselves matter as an indication of the culture clash between the establishment press and, by extension, traditional presidential politics, and the rise of celebrity politics that Trump represents.

Of course, since the 2016 Trump campaign was highly unusual in many respects, analysts should be careful in drawing conclusions, even more in making predictions, based on this particular campaign. Trump, in sharp contrast to previous celebrities who have traded on their fame to establish themselves as politicians in more or less the traditional sense of the word, has never evolved into a “normal” politician. Consider President Trump’s early morning Twitter rants; his reality-show-like reveal of his Supreme Court nominees à la The Bachelor; and his live White House policy meetings on immigration, gun control, and video game violence. Trump’s performance of politics, in other words, deeply erodes what remains of the line between entertainment and politics.

Our project contributes to the increasingly relevant intersection between scholarship on celebrity politics and journalism standards by highlighting several factors that future scholarship should take into account. First, it underscores the important and continuing role of traditional political institutions like the establishment press in structuring presidential elections, even when those elections feature celebrity candidates who don’t play by the rules of traditional presidential politics. While legacy press coverage may not determine who ultimately wins the White House, the press’s decisions about who to cover and how are still an important factor in structuring the electoral chances and the public’s images of candidates.

Second, our study underscores the importance of recognizing the cultural collision that occurs when a Trump-like entertainer runs for president. Press coverage of the 2016 campaign reveals a struggle between two modes of politics as the dominant species of the old media and politics ecosystem strive to maintain their place in the emerging, hybrid system. While celebrity politics seemingly prevailed in 2016 (though, as we note earlier, abetted by a myriad of other factors), that may not always be the case, as the struggle for dominance among these two modes of politics continues.

Third, our study helps urge scholars to pay attention to the particular genre of entertainment from which the celebrity politician emerges (as Street Reference Street2017 has recently explored), which will shape their performative style. Affable actors like Ronald Reagan have played the role of conventional politician, but Trump has approached politics like a cutthroat reality TV show. The difference in styles helps explain how the establishment press has responded to their candidacies. Comparative research across celebrity campaigns should explore and document these dynamics.

Fourth, our project helps articulate a dilemma presented by the linked phenomena of the world-wide rise of populism and of populist celebrity politicians. Populist politics present the establishment press with an acute dilemma that is deepened when the face of populism is that of a popular celebrity. As scholars have noted, there is often an “unintended complicity” between the media and populist politicians because of the media’s appetite for the very kinds of controversy populist politicians stir up (Mazzoleni Reference Mazzoleni, Albertazzi and McDonnell2008). A recent report (de Vreese Reference de Vreese2017) offers the following, contradictory advice to journalists: “Cover politics as usual”—that is, don’t feed the populist narrative of exclusion by elites by writing populist candidates out of news coverage; but at the same time, “Don’t cover politics as usual”—that is, don’t normalize populists’ extreme rhetoric, the report advises. Journalists covering Trump’s 2016 campaign faced this dilemma explicitly. Intertwined with that dilemma was another: How to bring the high news value of Trump’s bombastic campaign, the unusual provenance of his candidacy, and the potentially serious implications of his campaign into balance.

Finally, looking ahead, as entertainment further infuses politics, and public sentiment toward celebrity politics continues to shift, a key question will be whether the press will take future celebrity candidates more seriously. This question is a critical one given the recent rise of racist, xenophobic, and authoritarian attitudes both in the United States and around the world, and the accelerating hybridization of the media ecosystem. Trump resembles political leaders beyond the United States who hail from outside of traditional politics and bring a bombastic showman’s style to the political stage. The respective political reigns of media mogul Silvio Berlusconi in Italy (who once declared “I am the Jesus Christ of politics”Footnote 8), Hugo Chavez in Venezuela (who famously starred in his own TV show while in office), and Rodrigo Duterte of the Philippines (who in 2017 debuted his own TV show) suggest that populist/authoritarian politics fueled by entertainment values and tactics are becoming more common.

These trends suggest that the American press may face the conundrum of the celebrity/politics collision, with no easy solution, sometime in the not too distant future. One big difference, however, will be that journalists as well as citizens now know that it is possible for a reality TV celebrity with no traditional political qualifications to become president, even if (or perhaps especially if) that celebrity does not act the part of a traditional politician. And, thus, the press will likely rely less on the assumption that a dismissive tone of coverage will effectively winnow an unqualified candidate. We expect, in other words, that the press might shift to treating future celebrity politicians more “seriously.”

As just one example of how Trump has paved the way for shifting conceptualizations of celebrities and politics, consider a potential celebrity politician of a very different sort: Oprah Winfrey, whose possible candidacy has long been the subject of speculation. Back in 1999, Donald Trump appeared on CNN’s Larry King Live to announce his plans to form a presidential exploratory committee. When King asked “Do have a vice presidential candidate in mind?” Trump responded “Oprah, I love Oprah. Oprah would always be my first choice” (CNN 1999). Newspapers covered the idea of Trump as a presidential candidate and of Oprah as his running mate derisively.9 Oprah was also floated as a presidential candidate, with a similarly dismissive response. CNN host Bobbie Battista asked, tongue-in-cheek, “Would we have to read all the books that she recommends, would that become law?” (Battista Reference Battista1999). In one poll in 1999, more than 80% of Americans said they would not consider Oprah to be a serious candidate (Shaw Reference Shaw1999).

Fast forward to 2018, and pundit discussion about the idea of an Oprah campaign has a much different tenor. Many pundits have offered serious analysis of what an Oprah campaign would look like (e.g., Kurtz Reference Kurtz2018). In the aftermath of Oprah’s riveting speech at the 2018 Golden Globes show, where she accepted a lifetime achievement award, all manner of pundits and politicos weighed in approvingly, including long-time conservative columnist William Kristol, and former Obama senior advisor Dan Pfeiffer, who tweeted, “I slept on it and came to the conclusion that the Oprah thing isn’t that crazy” (quoted in Williams Reference Williams2018). And the public, too, seems to be taking seriously the idea of additional celebrity presidents. In a 2018 hypothetical election poll, Oprah was found to beat Trump by a 51% to 42% margin (Struyk Reference Struyk2018).

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S153759271900238X