Allusion, quotation and collage are hallmarks of postmodern music, particularly in the case of opera whose past remains so overwhelmingly present in the opera house. Given that opera was routinely declared outmoded throughout the last century, the very act of creating (not to mention producing) a new opera has long been freighted with particular significance. Similar to the situation faced by would-be symphonic composers post-Beethoven, an aspiring opera composer in the mid- to late twentieth century faced the widespread perception that opera was a genre with a weighty past, and entirely of the past. Only during the last two decades have composers created enough new operas for it to seem increasingly normal to do so.Footnote 1 Recent operas exhibit a wide range of motivations for, and approaches to, making musical allusions to the past – even operas by composers who otherwise seem intent on breaking with tradition. The genre's inherently interdisciplinary form invites intricate types of allusion, as characters, dramatic situations, stagings and lines of text may be shaped to recall earlier works, thereby spinning webs of intertextual meaning and suggesting richly rewarding interpretive pursuits. The play of musical allusion and borrowing in contemporary opera, in both overt and more covert forms, has resulted in examples of obvious sonic slapstick as well as intensely poignant and intricately layered moments of reminiscence.

Though Rossini alluded to Mozart (who quoted himself) and Debussy could never fully exorcise Wagner from Pelléas et Mélisande, rampant allusion in opera is most evident in the genre's recent past. The extensive borrowing from self and others encountered in Handel's operas, in eighteenth-century pasticcio operas, and in the ‘suitcase aria’ practice of the nineteenth century stemmed more commonly from strategies of practical efficiency rather than creative acts of allusion. But since the late 1970s, new operas have been more likely to feature a collage of multiple allusions to specific works, stark stylistic juxtapositions and references to a broader range of styles, with more elaborate symbolic resonances. Allusions in recent operas run the gamut in terms of perceptibility, from the direct references to Bellini's ‘Casta Diva’ and Puccini's Tosca in Ricky Ian Gordon's Ellen West (2019), to ghostly palimpsest traces of Purcell's ‘Dido's Lament’ in Missy Mazzoli's Song from the Uproar (2012).Footnote 2 Contemporary opera's penchant for allusion may be viewed as reflecting a broader cultural phenomenon, given the recent embedding of ‘Easter eggs’ in Hollywood films, the ever-increasing generic reflexivity of Broadway musicals and the evolution of hip-hop from dense collaged sampling to more audible shout-outs to the musical past. In this sense, opera is not so different from other forms of omnivorous contemporary cultural production that capitalise on a seemingly boundless access to the past and inspire illusions of ownership while expressing nostalgia for, or even a political critique of, shared cultural artefacts.

My detailed investigations reveal how musical allusion in contemporary operas can shape our understanding not only of specific characters and plot points in those works but also of each composer's relationship to the genre and its history. In most of the cases considered here, allusions appear to be functional and purposeful, bringing with them relevant meanings selected for specific moments – a finding that contradicts some standard assumptions concerning musical postmodernism. Allusions to canonical operatic music often occur at ‘operatic’ moments in the plot, moments of high emotion (e.g., laments, declarations of love), as well as at moments of pointed satirical representation. This suggests that contemporary composers, and likely their audiences, view older opera as (alternately) profound and ridiculous in emotional register. I find that analytical acts of uncovering and explicating allusions repeatedly produce interpretations of an opera and of a composer's artistic personality that run counter to prevailing views – and to positions stated by the work's authors. In addition, musical allusion tends to produce starkly differentiated experiences between audience members of the same work, an aspect that continues to shape impressions of the genre and its potential future more generally.

In this article I argue that allusions are most often meaningful and even symbolic in recent postmodern operas. I first briefly consider musical collage in operas that represent a proverbial ‘postmodern’ approach to the past, thereby establishing a baseline for my analysis of more recent works. Multiple operas composed from the late 1960s to the early 1990s feature a collage of quotations and allusions; operas by John Cage and John Corigliano serve as extreme cases here. The core sections of the article are then devoted to three operas by prominent contemporary composers whose stylistically divergent approaches illustrate the range of forms and motives that musical allusion has taken in operas produced over the past few decades. All three selected works are explicitly based on the past: John Adams's Nixon in China (1987) stages historic events and iconic moments; Louis Andriessen interweaves several classic literary works in La Commedia (2008), a ‘film opera’ that will serve as my primary example; The Exterminating Angel (2016) by Thomas Adès is based on a celebrated surrealist film from over half a century prior. By detailing the presence and processes of musical allusion in these three works I offer evidence in support of a revisionary understanding of these operas and the aesthetic stances of these composers, who each engaged extensively in musical allusion for different purposes. Adams employs near quotation, particularly of music by Wagner and Stravinsky, resulting in satiric characterisation, despite the creative team's disavowal of intentional political satire. Contrary to his image as a politically motivated ironic iconoclast – and despite his own assessments of his music as unsentimental, detached and non-expressive – I find that Andriessen employs rampant stylistic allusion in La Commedia as both a form of personal expressive symbolism and to deflect, through humorous juxtaposition, our attention away from the otherwise deeply tragic and melancholic affect of this work. Finally, though Adès has referred to his musical allusions as transparent ‘keepings’ from pre-existent music that he simply employs in spots in his scores where they happen to sound right, I show that in The Exterminating Angel he composed what Christopher A. Reynolds has termed ‘assimilative allusions’ that incorporate ‘aspects of the meaning and musical character’ of their source.Footnote 3 Adès proves quite intentional in his careful selection of musical sources as he distorts the musical past to surrealist effect in this opera. In short, the genre has in recent decades repeatedly inspired composers to harness allusion for its potential to suggest specific dramatic and symbolic meanings, to express both emotional depth and satiric deflection, and to declare either distance from or continuity with the operatic past. These examples reveal that though contemporary composers continue to revel in postmodernist play with the past, allusion-making is rarely a mere game. I conclude with several rather unexpected examples of operatic allusion by composers who typically do not reference the musical past at all in their works, thereby indicating the striking prevalence of allusion throughout contemporary opera.

Assessing allusion

The motivations for alluding are myriad. The act of alluding may draw on the energy and prestige of the source or offer the audience familiar material embedded within an otherwise unfamiliar style. In doing so, it may pay homage to or suggest mastery over the musical past, or perhaps undermine it through ironic recontextualisation. Musical allusion may signal a composer's spiritual affinity or private communication with the dead – or with the self. Alternatively, the musical past may be treated as mere material, a source of found objects for the purposes of collage, leaving any interpretive associations completely up to the audience. Composers of contemporary opera have exhibited each (or a combination of each) of these motivations.

It is less easy to determine what qualifies as allusion and whom to credit with the operative role in allusive experiences. My focus will be on contemporary examples of references to specific works from the past and my approach draws on the foundational work of J. Peter Burkholder and Christopher A. Reynolds. Burkholder has considered the study of musical allusion and borrowing from a particularly wide perspective, across time and genres.Footnote 4 However, he has argued for a somewhat strict definition: ‘Proof of borrowing is incomplete until a purpose can be demonstrated. If no function for the borrowed material can be established, its use remains a mystery and the resemblance may be coincidental.’Footnote 5 For Burkholder, if we are unable to identify an intention behind a moment of musical resemblance to a past work we should categorise such moments as examples of ‘curious coincidence’ rather than of borrowing or allusion. This also suggests that the explanation ‘it sounded good to me at this moment in my score’ proffered by some contemporary composers (see my discussion of Adès later) does not qualify as an act of purposeful allusion inviting interpretation. Burkholder has offered several criteria and strategies for adjudicating whether intentional borrowing has taken place, including taking into account the composer's typical practice.Footnote 6 Christopher A. Reynolds has also emphasised compositional intention and audience perception as crucial factors, though he allows for the possibility that the composer was the intended audience for private allusive meanings.Footnote 7 In such cases, our perception of allusion suggests secret knowledge, that we have succeeded in experiencing the musical moment from the composer's private perspective. Of course, such successful sleuthing may well prove illusory. Karol Berger has admonished that ‘we should resist the temptation of trying to decide the undecidable cases’, concluding that ‘it is useless … to appeal to the author's intention’.Footnote 8 A most restrictive position was put forward in 1992 by Michael Leddy who argued that music is only capable of imitation rather than allusion, failing to note that music may more or less closely resemble a specific musical passage from the past without quoting it exactly, thereby allowing for allusive possibilities.Footnote 9 Other scholars have placed emphasis on the perspective of the audience rather than on authorial intention. As Raymond Knapp put the case: ‘it is in the end the music that alludes, not the composer.’Footnote 10

Like Knapp, I leave open the possibility that the mechanisms of musical allusion may well function for audience members who hear resemblance and interpret significance even in cases where the composer was not conscious of making the allusion. Indeed, ‘mere’ resemblance between, for example, a minimalist or post-minimalist opera and the music of specific older works remains a striking and significant feature given common assumptions of minimalism's disassociation from the operatic canon. At the limit point of such unintended allusion we might be tempted to return to the structuralist claims of Deryck Cooke, who argued in 1959 that inherent features or conventional usage of certain melodic gestures and specific intervals led multiple European composers throughout tonal music history to employ similar motives for similar expressive purposes.Footnote 11 Though I remain intrigued by cases of ‘curious coincidence’ in musical resemblance, I will for the most part constrain myself to working within Burkholder's and Reynolds's definitions in my selection of examples here.

Beyond definitional questions, there are several concerns that might well give the would-be analyst of musical allusion pause. A particular source of anxiety is the extent to which we are not only enabled but also limited by our own musical experiences as we approach the investigation of new pieces. For example, are the works of Stravinsky, Wagner, Richard Strauss, Ravel and Monteverdi actually more frequently alluded to by the contemporary opera composers I focus on here, or do I notice these specific allusions, while missing others, because I happen to know this body of earlier music particularly well? Furthermore, is the fact that most of the examples I identify have not been discussed before an indication that my own musical background is predetermining and distorting my encounter with these more recent works? Or, as I would prefer to assume, have some of these allusions remained unremarked because the composer in question has been considered unrelated to and uninterested in the earlier music I cite? Perhaps other critics and scholars do hear these allusions but have feared a version of Brahms's alleged rebuke when he was asked about the allusion to Beethoven's Ninth Symphony in his own First Symphony: ‘any ass can see that’. It is not clear whether one should most dread sceptical responses, suggesting an eccentric hearing, or immediate agreement, suggesting a revelation of the glaringly obvious, when claiming to uncover cases of allusion. Finally, there is the conundrum faced by any scholar of contemporary music: should we consult the composer?

Though I have not queried Adams, Andriessen and Adès about musical allusion in their operas, several experiences have suggested the potential complexities of such conversations. For example, I have suggested that the impact of Wagner's Tristan und Isolde and to a lesser extent Debussy's Pelléas et Mélisande is evident in multiple aspects of Kaija Saariaho's opera L'amour de loin (2000). The medieval setting, emphasis on the sea, an impossible love, the death of the male lead on a distant seashore, and the romantic transcendence of the female from our quotidian realm at the end, all point to Wagner's Tristan und Isolde. Saariaho has frequently mentioned her love of Wagner's opera and others have noted her striking use of a chord that resembles the Tristan chord.Footnote 12 However, I find that Saariaho references Wagner in a nearly inaudible way as well. The very opening starts quite low in Rheingold-depths territory with the opening interval from Tristan, but up a semitone (rising from B♭ to F♯, instead of from A to F) and moving from bass to cello instead of being played on cello alone. I am not alone in noting similarities between Tristan and L'amour de loin as, for example, Liisamaija Hautsalo has explored this subject in detail.Footnote 13 Other scholars, such as Yayoi Uno Everett and Joy H. Calico, have noted the general relationship but have tended to emphasise differences between the two operas, and Pirkko Moisala has gone so far as to claim that Tristan and L'amour ‘do not have anything musical in common; they are products of vastly different stylistic periods in Western art music’.Footnote 14 Should the composer settle this debate? When I suggested details of apparent Wagnerian influence on a panel with Saariaho, she graciously replied that while the resemblance might well exist, it was purely coincidental as she did not have Tristan in mind when composing her opera.Footnote 15 Conversely, during an interview with Christopher Cerrone concerning his operatic works, I happened to mention that I heard suggestions of Tibetan music or, better, of Philip Glass's film score for the 1997 movie Kundun at certain moments in Cerrone's 2013 opera Invisible Cities.Footnote 16 On the subject of musical allusion in his compositions more generally, Cerrone demurred, stating ‘I don't think I would know how [to allude]’. However, he then referred to the influence of Indonesian gamelan music on Invisible Cities and stated that Britten's Curlew River was a major influence on his opera and that the music of the sixth scene in Invisible Cities is a direct ‘ripoff’ of the sixth scene in Bartók's Bluebeard's Castle, an operatic connection that I had somehow missed.

Raising the subject of possible allusions in a composer's work may spark a certain electrical charge between critic and composer, but as Reynolds notes of the efficacy of allusion in an earlier period, ‘[s]everal Romantic composers fulfilled another function of play by creating elite audiences, communities of the initiated, who were privy to musical secrets’.Footnote 17 Compositional techniques aimed at creating exclusive audiences do not appear to be in the genre's best interest at this moment in its storied history. Does musical allusion hold the potential to revitalise opera and to suggest continuity with the past, or does it inevitably emphasise the archaic, exclusive nature of the genre? Though engaging in extensive musical borrowing may expose a contemporary composer to charges of creative dependence on the past, allusion also places a new opera in a lineage, suggesting that this new work might one day itself be alluded to in operas of the future.Footnote 18 Thus, musical allusion may simultaneously highlight the genre's historic status and affirm its creative continuity.

Postmodern operatic collage: Cage and Corigliano

Like other modernist devices that became conventional, collage was easily absorbed, in moderate doses, into the mainstream concert repertoire. There is no reason to apply a term like ‘postmodernism’ to it.

Richard TaruskinFootnote 19Despite Taruskin's tempting invitation to avoid the term entirely, ‘postmodernism’ is routinely employed to label music composed from the 1960s to the 1990s that engages in both moderate and immoderate collage and pastiche of past musical styles and works. However, there the critical consensus ends, for each commentator's description of a postmodernist work is shaped by divergent understandings of the term as it refers to interactions with the artistic past. Those who follow Fredric Jameson's framing, which ill fits much music labelled ‘postmodern’, hear allusions to and borrowings from the past as neutral incorporations made by the composer without comment.Footnote 20 Others have emphasised composers’ active engagement and frequent ironic expression. For example, Linda Hutcheon and David Metzer both point to a postmodernist penchant for ironic distance from and even antagonism with the past while Jann Pasler, drawing on Hal Foster's categorical view of postmodernism as engaging in either conservative reaction or progressive resistance, suggests an evolution in postmodern attitudes to distant sources.Footnote 21 (Foster's assertion that ‘postmodernism is not pluralism’ would likely disqualify several of the operas considered here from the label.Footnote 22) A brief survey of postmodern operas reveals examples in support of all these positions, thereby stretching the term ‘postmodernism’ to the limits of practical use.

Discussion of collage in early postmodern operas routinely points to quotations of J.S. Bach in Bernd Alois Zimmermann's Die Soldaten (1965) and Hans Werner Henze's The Bassarids (1968), echoes of numerous earlier composers in Henri Pousseur's 1969 Votre Faust, and the role of Monteverdi and Striggio's Orfeo in Luciano Berio's Opera (1970, rev. 1977), though these quotations are often not as audible as are allusions made in later postmodern operas.Footnote 23 Ligeti's Le grand macabre (1977, rev. 1996) has proven a particularly relevant model and been much discussed. We will find that the ironic and grotesque expression prominent in several of Andriessen's operas and Adès's twisted distortions of Bach in The Exterminating Angel appear to owe a good deal to the spirit of Ligeti's opera.Footnote 24 Borrowing and quotation in such operas tends to occur in specific scenes rather than throughout the entire score. For example, in the Act II interlude between scenes 1 and 2 in York Höller's Der Meister und Margarita (1989) we hear at Rehearsal Number 50 a clear reference to the celebrated representation of church bells from Mussorgsky's Boris Godunov, and Höller indicates in his score the moment in scene 3 (‘Satan's Ball’) at No. 104 when he draws on Busoni's Doktor Faust, and again at No. 111 an allusion to Berlioz's La damnation de Faust, before the score moves on through a Baroque Handelian brass section to an excerpt from the Rolling Stones ‘Sympathy for the Devil’.Footnote 25 In this case, the multiple references to pre-existent devilish music are directly inspired by the opera's plot. (In fact, the devil, in one guise or another, makes appearances in numerous postmodern European operas. The figure of Faust and Stravinsky's 1951 The Rake's Progress clearly cast long operatic shadows.) However, in several other early postmodern operas, borrowing suggests a more general commentary on the past rather than the creation of a moment when the past has been harnessed to bring a specific meaning to a new work.

Alfred Schnittke's operatic career illustrates this continuum of approach particularly well. His ‘polystylisms’ often appear motivated not by symbolic or dramatic aims in an opera but by seeming to satisfy the composer's omnivorous aesthetic embrace. Indeed, Schnittke's Life with an Idiot (1990) has prompted commentators to list the numerous composers and styles and specific works referenced in the score, but not to make specific interpretive claims beyond pointing to the composer's fundamental satirical impulse.Footnote 26 The stylistic archaicisms heard in his 1992 opera Gesualdo are certainly not unexpected given this operatic subject. However, in his final opera, Historia von D. Johann Fausten (composed 1980–94), allusions frequently appear to convey more specific meanings at certain moments in the drama. As does Gesualdo, Historia prominently features archaic stylistic allusions: Mephistophiles is cast as a countertenor; the orchestra includes transverse flute, krumhorn, lute and zither; the work's structure suggests the Baroque oratorio genre. In the final bars of Act I, at the end of the choral warning against sin (‘A Rhyme Against Faustus's Obduracy’), four trumpets deliver an assertive triplet figure with two crotchet rests between each statement a total of five times – a gesture very similar to the final four bars of Strauss's Salome as that title character is crushed by the orchestra for her deviant sin. The general late Romantic schmaltzy style – a sort of mashup of Mahler and a sentimental pop ballad – heard as Mephistophiles/Mephistophila offer false comfort to the damned Faust, is also specifically motivated by the drama. More pointed allusions appear near the opera's end. We hear a very clear allusion to the second half of the opening phrase of Wagner's Tristan und Isolde as the Narrator refers to Faustus's servant named Wagner (‘Wagner gefunden’) to the accompaniment of saxophones and bassoons.Footnote 27

None of the above-mentioned European examples of operatic postmodernism come close to the flamboyantly collaged, but sharply contrasting, American works to which I now turn: Cage's five Europeras (1987–91) and Corigliano's The Ghosts of Versailles (1987/1991).Footnote 28 These contemporaneous works clearly illustrate divergent approaches to incorporating the musical past and the differing results of mashed up sampling and intricate allusive play. With the Europera label, John Cage – not known for his reverence for or allusions to the musical past – cleverly suggested both his distanced perspective on ‘your operas’ and the European nature of the genre as he sourced eighteenth- and nineteenth-century European operas. Noting Cage's position vis-à-vis the genre, Andrew Stiller referred to Europeras 1 & 2 as an ‘extended multi-media meditation on opera as a European social institution, employing its materials but viewing it from outside with an almost anthropological detachment’.Footnote 29 These works employed chance operations, through a computer programme designed to function analogously to the I Ching, on pre-existent material resulting in a live performance collage of arias, historical costumes, stage directions and orchestral excerpts from the operatic past.Footnote 30 In addition, Cage created what he termed a ‘truckera’ – a tape-collage of 101 superimposed opera recordings that fades in from the right and then out through the left-side speakers, like a sonic operatic semi-tractor-trailer cruising through the performance. In Europera 3, as the ‘truckera’ twice comes barrelling through the soundscape, the arias, rather than ending up as roadkill, continue on as though unaffected by the intrusion. In certain sections, the layered arias happen by chance to blend or coexist in a conventionally beautiful way that suggests a stylistic continuity running throughout the historical source material.

Cage's motives may seem rather obviously deconstructive, with the operatic past offering mere material to be collaged and any interpretation of operatic allusion and juxtaposition left to the listener to determine – assuming the listener is inclined to engage in that particular historically minded game.Footnote 31 In 1965 Cage stated: ‘I would not present things from the past, but I would approach them as materials available to something else which we were going to do now.’Footnote 32 However, when experiencing these works certain moments suggest a nostalgic rather than deconstructive approach to the operatic past, perhaps despite authorial intention. In fact, some commentators have argued that these late career works and the genre of opera inspired a rather different artistic attitude in Cage. David Metzer senses the ‘vulnerability of opera’ and a nostalgia for an ‘irrecoverable past’ in Europera 5.Footnote 33 Similarly, David W. Bernstein argues that with Europeras 1 & 2 ‘one is not in fact experiencing a parody of opera’ and that in creating Europeras 3 & 4 and Europera 5 Cage ‘developed a certain appreciation for operatic singing and repertoire’ and in these later works a thinner texture allows fragments from the operatic past to sound out loud. For Bernstein, Europera 5 even betrays ‘a certain nostalgic quality’ and offers a ‘sentimental retrospective’.Footnote 34 Nostalgia and sentiment are not terms typically employed to describe Cage's music. For numerous recent composers, opera appears to function as a particularly powerful magnetic attraction to the past, pulling into its orbit the most unlikely composers and warping their proclaimed aesthetic profiles.

In contrast to Cage, Corigliano understands the operatic past as a significant part of our current experience, a vast storehouse of available musical and dramatic techniques and meanings that originated in the past but that live on in the present.Footnote 35 Though he had also tackled the operatic past head on in 1970 with David A. Hess in the rock-infused The Naked Carmen, The Ghosts of Versailles stands out in his œuvre, and perhaps in postmodern opera more generally, as the most thoroughgoing and multi-layered approach to pluralistic allusion. The characters in The Ghosts are taken from Beaumarchais's Figaro trilogy – and from the buffa operas of Mozart and Rossini based on the first two of these plays – and from the lives of such historical figures as Beaumarchais himself, Marie Antoinette and King Louis XVI. In this opera's ingenious concept, the ghosts of these historical French figures are discovered stuck in limbo today. The ghost of Beaumarchais is now in love with the ghost of Marie Antoinette and feels rather guilty for her demise given that his plays were cited by Napoleon for helping to inspire the revolution. Beaumarchais has resolved to write a new opera, first to woo Marie Antoinette and then to rewrite history by having his fictional Figaro come to the rescue of the queen whose ghost longs to live again. When Figaro revolts and declines to follow the plot, Beaumarchais enters into his own opera and stages the trial of the queen in order to convert Figaro to her cause. At this moment we (the living audience) observe the ghosts as they watch Figaro watching a re-enactment of the trial. In this second act, the world of the ghosts and the world of the historical figures are collapsed within the frame of Beaumarchais's opera. Such a complex construction, with its multiple dramatic time zones, allowed Corigliano to slip stylistically into and out of the past at will.

Scoring for synthesiser and harpsichord in The Ghosts of Versailles was but one way for Corigliano to reflect this layered temporal reality. Another was to allude to or quote an array of styles, forms and specific opera plots and scores from the past. Some of these operatic ghosts make rather bold appearances, as when Beaumarchais declares to Figaro in Act II scene 1, ‘I am your creator!’ to the stentorian motive of the Commendatore (‘Don Giovanni!’) heard near the end of Mozart's opera. Many of Corigliano's allusions to specific past styles and works appear to have been selected for particular moments in his opera. Corigliano has gone to some lengths to defend his use of the past and to proclaim his originality, explaining: ‘What makes this not pastiche is inevitability – the fact that these different techniques are required by the structure you're building. They're not merely pasted next to each other for effect – they are integral to the working of the piece.’Footnote 36 The critics, reflecting divergent understandings of and attitudes towards postmodernism, have been divided on Corigliano's extensive borrowings. Edward Rothstein, referring to the opera as a ‘postmodern pastiche’, found that ‘in the midst of the irony, there is also a strong sense of longing; when the opera is not parodic, it is nostalgic. … The lost world is not mocked; it is missed’. He concluded that the opera was typically postmodern in that it ‘yearns for something it has too much irony to really want; it escapes into mist, plundering the past, seeking amusements, projecting nostalgia’.Footnote 37 Though also offering an appreciation of Corigliano's allusive techniques, Anne C. Shreffler argued instead that The Ghosts of Versailles did not involve parody and exhibited no distance from its sources and that in Corigliano's borrowings the ‘specific models are not important’.Footnote 38 Other commentators have been less intrigued by Corigliano's allusions, with Alex Ross referring in 1992 to the opera as an exemplar of ‘the increasingly numerous American eclecticists – Adams now included, Corigliano still at the forefront – [who] opt instead for nowhere music, for zombie music, for pastiche’.Footnote 39

The Ghosts of Versailles prompts or even dares us to generate lists of composers and librettists whose styles, techniques and specific works haunt this opera. One such list might well include Mozart, Da Ponte, Rossini, Donizetti, Verdi, Boito, Wagner, Puccini, Strauss, Hofmannsthal, Schoenberg, Stravinsky, Auden, Honegger, Claudel, Britten, Penderecki, Barber and Bernstein, as well as the music of Gregorian chant, North African Arabic traditions, the late eighteenth-century European alla turca operas, French grand opéra, Broadway (particularly the megamusical genre) and serialism. Throughout The Ghosts, Corigliano and Hoffman make significant references to earlier operas and thereby produce intricately layered meanings. Moreover, they tend deliberately to cite similarly self-conscious works that also referenced the past. These references are frequently calculated to point to multiple operatic models simultaneously. For example, before the elegant Act II scene 5 ball is interrupted by the revolutionaries and the aristocrats are led off to prison, the onstage orchestra plays a tune that closely resembles Figaro's ‘Se vuol ballare, Signor Contino’ from Mozart's Le nozze di Figaro. The citation is pointed, given that Mozart's Figaro sings in his cavatina of overthrowing the Count's plans. Corigliano may also have intended an additional reference here, for Mozart himself quoted another tune from Le nozze di Figaro in his music for the onstage orchestra entertaining Don Giovanni as that rakish nobleman dines shortly before the Commendatore arrives to drag him to hell. At that point in Don Giovanni the onstage band plays Figaro's ‘Non più andrai, farfallone amoroso’ with which Figaro taunted Cherubino after the Count announced he would be sent off to the military – a perfect hell for the young rake.

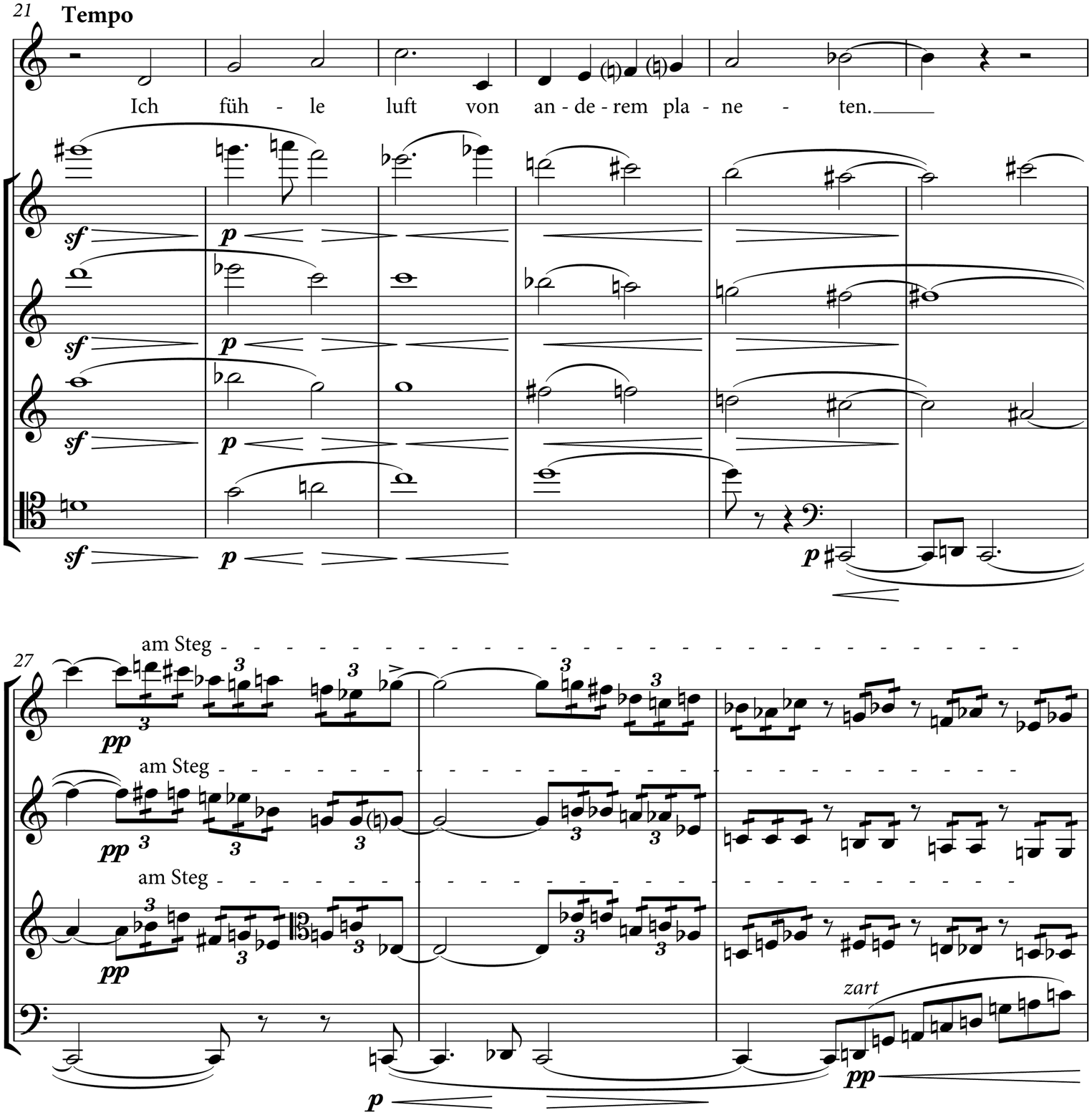

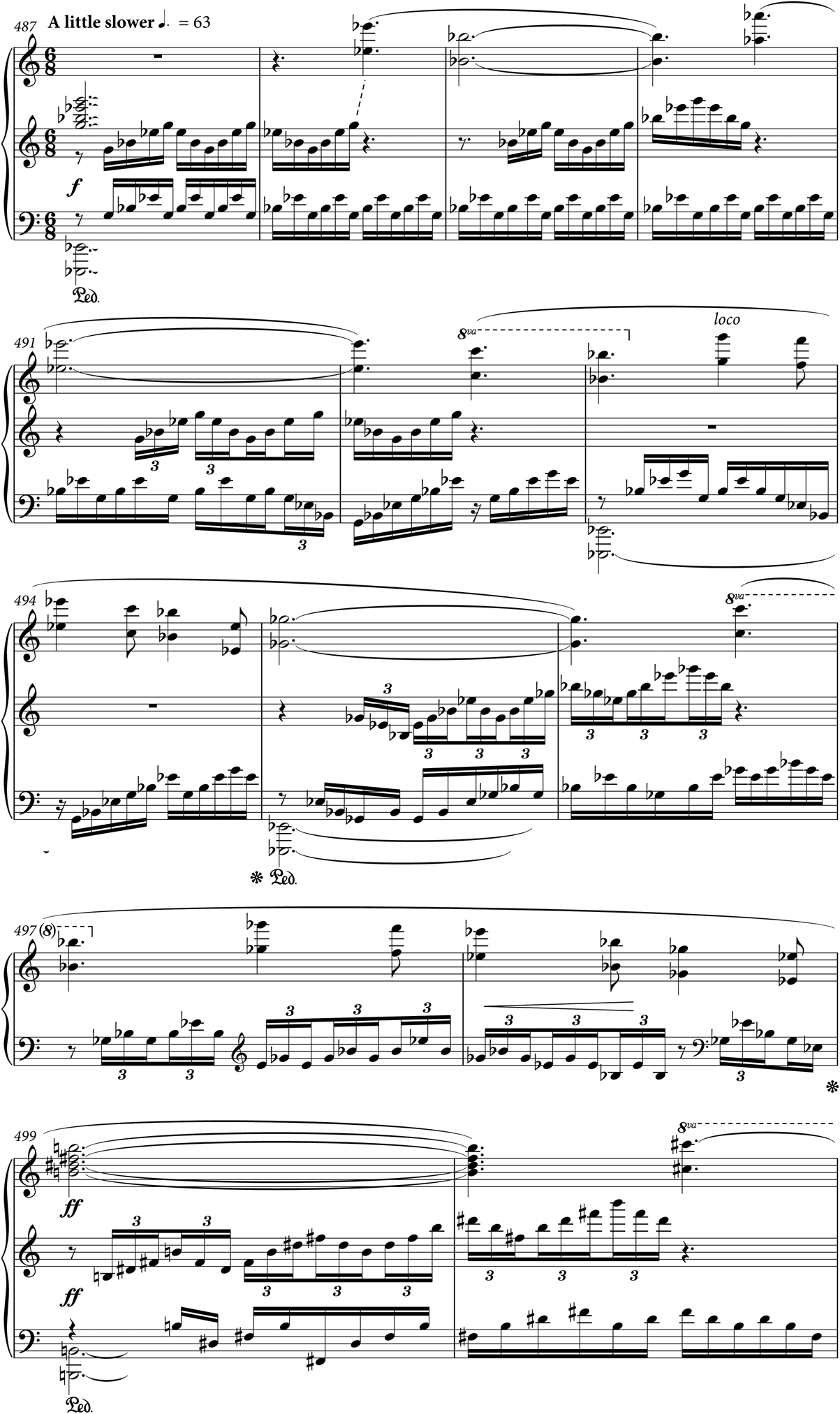

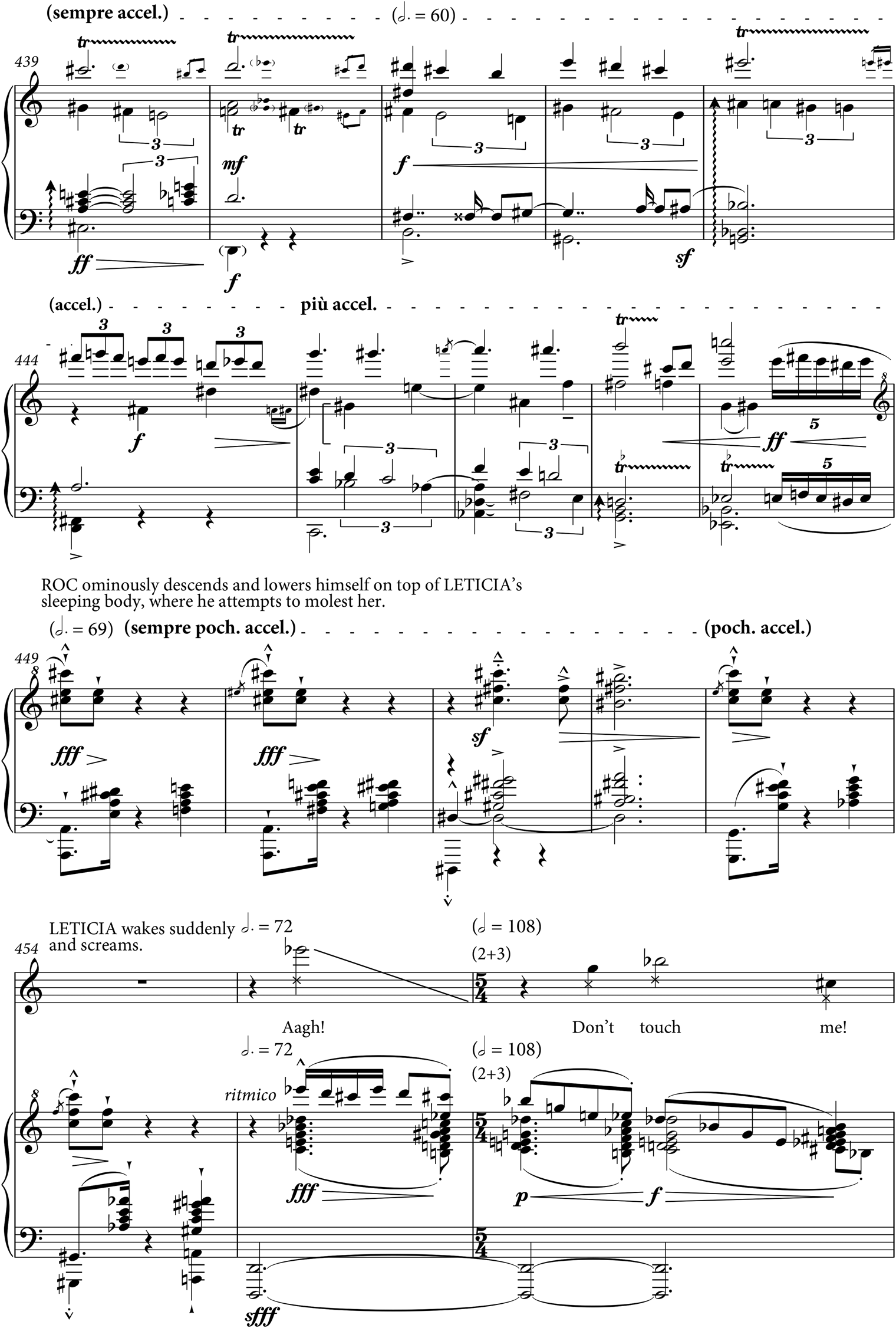

A similar piling on of references is discovered in the outrageous parody of operatic Orientalism in The Ghosts Act I finale. Here, Corigliano and Hoffman explicitly reference the Act I finale of Rossini's L'italiana in Algeri. In this opera, Rossini had himself pointed to Mozart's Die Entführung aus dem Serail and to Monostatos in Die Zauberflöte and he quoted the Commendatore in his Il turco in Italia.Footnote 40 To top it off, Corigliano and Hoffman ironically juxtapose Wagner and Rossini here as the Woman with Hat (one of the ghosts, dressed here as a Valkyrie) enters singing ‘This is not opera!! Wagner is opera!!’ accompanied by a direct musical gesture to the prelude of Tristan und Isolde and to the Tristan chord itself (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A visual allusion to Wagner's Brünnhilde front and centre at the end of Act I in John Corigliano's The Ghosts of Versailles (Metropolitan Opera, Deutsche Grammophon laser disc, 1992 performance, screenshot). (colour online)

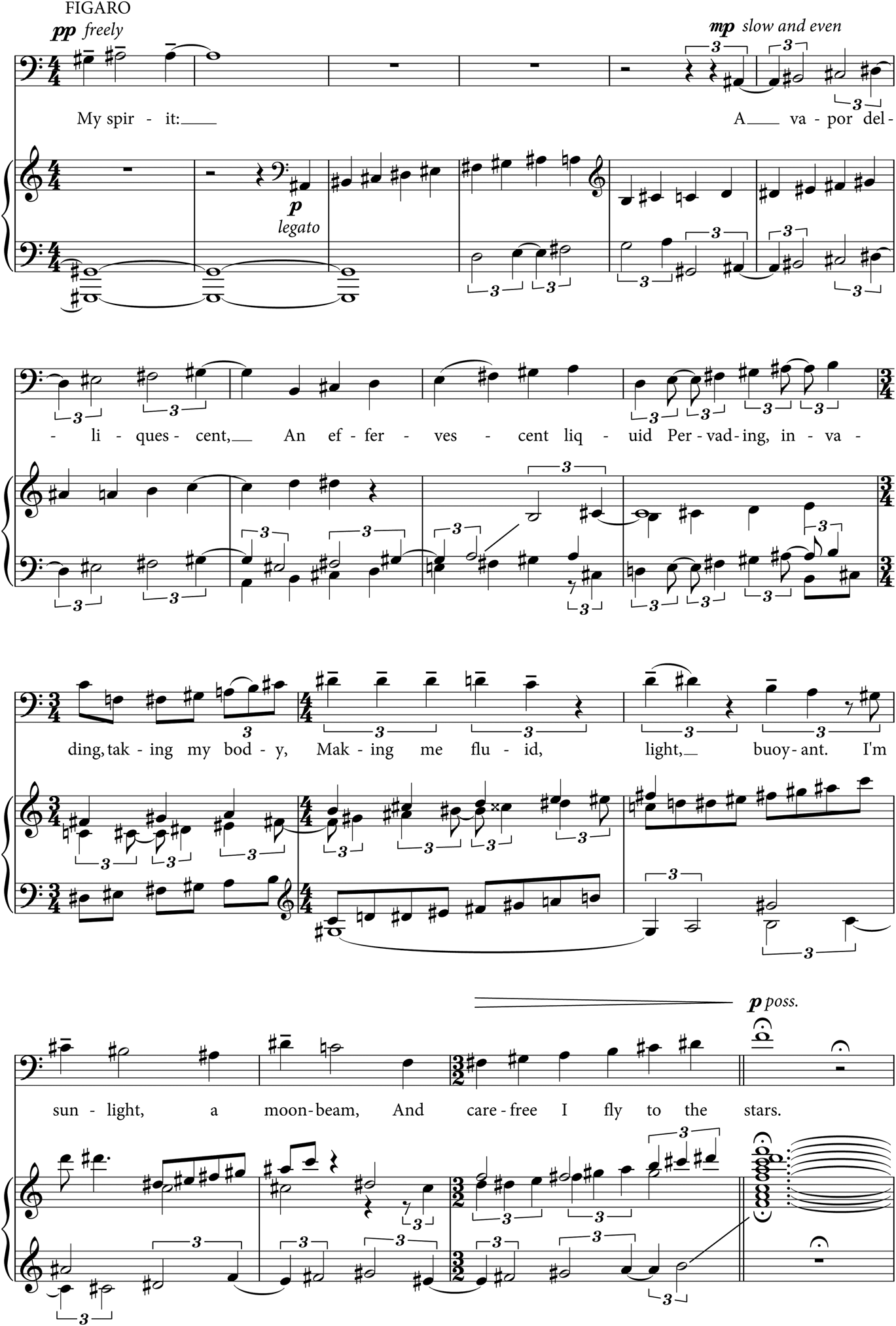

The very opening of the opera sets the stage for Corigliano and Hoffman's dense system of allusions. The collaged opening seems to arrest present time, allowing history to come forward. The first vocal music we hear is the Woman with Hat singing a French text to a twisted version of the tune ‘For he's a jolly good fellow’, which was originally the melody to the French song ‘Marlbrough s'en va-t-en guerre’, a favourite of Marie Antoinette's that became hugely popular at Versailles. The Woman with Hat's words here, however, are actually taken from Cherubino's Romance to the Countess in Act II scene 4 in Beaumarchais's Le nozze di Figaro. Beaumarchais had specified in his play that the ‘Marlbrough’ tune should be used in performances of Cherubino's text. In other sections of the opera, it is the juxtaposition of diverse styles that astonishes. For example, as Figaro is chased in the Act I prologue we hear the briefest of quotations from the overture of Le nozze di Figaro – a moment not that dissimilar from the way in which recognisable fragments from the operatic past pop out in Cage's Europeras, though here the allusion carries an obvious significance. Figaro launches into a patter song complaint about his life that refers directly to Figaro's ‘Largo al factotum’ in Rossini's Il barbiere di Siviglia. He then slips into the musical and textual world of the fourth movement of Schoenberg's Second Quartet as he sings of his effervescent and vaporous spirit and of floating away to the stars, thereby alluding to that movement's lyrics by Stefan George, which are sung by a soprano with the string quartet accompanying: ‘I feel the air from other planets … Then I see the fragrant mists rise … I feel I am above the last cloud, swimming in a shining crystal sea.’ Both Schoenberg's soprano and Corigliano's Figaro ‘fly to the stars’ on waves of rising chromatic lines (Examples 1a and 1b). Again, musical history arises here as time stands still in this opera.

Example 1a. Figaro's ascent to the stars, Act I prologue, John Corigliano's The Ghosts of Versailles (G. Schirmer).

Example 1b. The soprano's interplanetary perception, Arnold Schoenberg, Second String Quartet, fourth movement (Universal Edition).

The most exquisite example of layered allusions in The Ghosts of Versailles occurs in Act I scene 3 at another moment when dramatic time pauses, as Beaumarchais presents a romantic scene between the Countess and Cherubino in hopes of stirring Marie Antoinette's interest in himself. As the Countess repeats Cherubino's name in remorseful remembrance, we hear a distant echo of another Mozartian lament from Le nozze di Figaro. In the opening of the fourth act of Mozart's opera the young Barbarina – in love with Cherubino – laments that she has lost the pin that the Count asked her to deliver to Susanna as a secret signal that he will meet her that evening. Barbarina's beautiful lament has long been assumed to concern not merely a lost pin but instead her lost virginity. Presumably Cherubino – a young Don Giovanni figure – abandons her between the second and third plays in the trilogy. Corigliano coyly alludes to Barbarina's music here, transforming it from F minor to F# minor. Beaumarchais then announces that the scene will shift back twenty years as the Countess reflects on Cherubino's courtship. Cherubino and the younger Countess, dressed as shepherd and shepherdess, are observed playing a flirtatious pastoral game of hide and seek. As Cherubino sings ‘Come now, my darling, come with me’ he echoes the melody he sang to the Countess in Mozart's opera (‘Voi, che sapete’) and may remind us of Don Giovanni's seductive calls to Zerlina in another pastoral setting. The duet swells into a quartet as Beaumarchais and Marie Antoinette parallel this same amorous exchange in the ghostly realm.

Given the high profile of The Ghosts of Versailles, its numerous productions and conspicuous engagement with the past, it is not surprising that some opera composers of the last two decades have been influenced by its model and message. At the time of its premiere at the Metropolitan Opera in 1991 no new opera had been produced in that house for nearly twenty-five years. In creating The Ghosts – initially commissioned to celebrate the one-hundredth anniversary of the Met – Corigliano felt the full weight of this particular historical burden, though it is not entirely clear whether he harnessed allusion primarily to admonish or to court his audience. This opera's exuberant allusions persistently remind the audience of the operatic past and the canon's continuing presence and, more indirectly, point to the near exclusion of new works at that moment in operatic history. The decision to take on the past in this way may, in retrospect, seem inevitable, but it was not without risk. In the operas of Adams, Andriessen and Adès, allusions – both blatant and deeply buried – extend Corigliano's approach to operatic postmodernism by consistently suggesting dramatic and symbolic meanings.

Adams undermining characters with the past in Nixon in China

In comparison with most of the postmodern composers mentioned previously, opera has been more central to the careers of the three composers at the core of this article. This is particularly true of the œuvre of John Adams.Footnote 41 The postmodernist credentials of Adams are not in dispute with, for example, Robert Fink proclaiming the score of Nixon in China a ‘virtuoso postmodern pastiche’, a setting of ‘a brilliant postmodern libretto’.Footnote 42 Surprisingly, however, Adams's musical allusions frequently go unmentioned in the literature.Footnote 43 For example, in his book-length study of Nixon in China, Timothy A. Johnson mentions none of the multiple traces of Wagner's and Stravinsky's music.Footnote 44 Neither does Matthew Daines note allusions by Adams to these earlier composers in his dissertation devoted to the opera.Footnote 45 Why is this the case? Perhaps commentators do not expect to find traces of the musical past in such post-minimalist works, or perhaps resemblances in Nixon in China to music of the past frequently fall within a grey area of uncertain identifiability. We will find that Nixon in China contains examples of allusion illustrating the full continuum, from moments that appear to be coincidental resemblances, to passages presenting nearly exact quotations of earlier music.

A composer's allusions may reveal what music they were drawn to, what they thought that music represented and what their attitude was towards that pre-existent music. Of course, operatic context facilitates this understanding. This is particularly true in the case of Adams who, for example, has made multiple allusions to Wagner and Stravinsky in his operas, frequently for the purposes of characterisation. By repeatedly alluding to these two composers, Adams also reveals two of the main sources for his post-minimalist style: the endless waves of sequences of Wagner and the motoric ostinati of Stravinsky. We might be tempted to hear an allusion in the very opening of Nixon in China to the prelude in Wagner's Das Rheingold, with both featuring a hushed deep register pedal point and a repeated elemental rising scalar or arpeggiated presentation of the key. Alternatively, this opening might suggest to listeners the opening bars of an opera written only four years prior, Philip Glass's Akhnaten – both begin in A minor with a low pedal point on the tonic pitch and with rising lines. Or perhaps both operas independently point back to Wagner's proto-minimalism. This example illustrates a particular challenge to allusion analysis posed by minimalist-style works: can scales and arpeggios serve as melodic evidence of borrowing? At the other extreme of identifiability, a few specific Wagnerian allusions appear to serve satirical purposes. During the Act II Cultural Revolution ballet scene – a parodic allusion to The Red Detachment of Women, a Chinese model ballet – we see a male soldier revive a female comrade. Simultaneously, we hear Jochanaan's theme, from the moment he emerges from his cistern in Strauss's Salome, morph directly into the ‘Innocent Sleep’ leitmotif (transposed a half-step down), which is heard when Siegfried contemplates the sleeping Brünnhilde before wakening her in Act 3 of Wagner's Siegfried (Examples 2a, 2b and 2c). The deliberate Germanic musical allusions are comically out of place here, signalling a false heroic scale and parodying Chinese attempts to adopt Western styles.

Example 2a. Awakening the female comrade with Strauss and Wagner, Act II in John Adams's Nixon in China (Boosey & Hawkes).

Example 2b. Jochanaan emerges from the cistern in scene 3, Richard Strauss, Salome.

Example 2c. Siegfried gazes upon the sleeping Brünnhilde in Act III scene 3 of Richard Wagner's Siegfried.

Though the parodic representation of Cultural Revolution propagandistic art is manifest in Nixon in China, the opera's creators (Adams, Alice Goodman and Peter Sellars) have each – to different extents – claimed that they were not setting out to create a satirical portrait of the principal characters, that these characters were not intended to appear as cartoonish figures. But in response to critics who complained that Nixon and Mao were presented uncritically and even heroically, Adams and Sellars have claimed that there is a pointed critical dimension to the work. Adams in particular has attempted throughout his career to thread the needle, alternately embracing and distancing himself from the postmodern label, both disavowing irony and suggesting its presence in his works. For example, soon after the opera's premiere, Adams explained:

One of the things about the story that I found so appealing and why I enjoyed composing it, was the opportunity to move, during the course of three acts, from the plastic cartoon versions of public people that the media is always presenting us with, to the real, uncertain, vulnerable human beings who stand behind these cardboard cutouts. … But I don't view this as a satirical opera at all. There are elements of satire in it.Footnote 46

Adams has more recently made similar statements regarding his Harmonielehre, composed two years prior to Nixon in China:

There was a playfulness, even an impudence about my ease with appropriation. The music reveled in a kind of enlightened thievery that I would never be able to commit later. … Those writers who mistakenly compared Harmonielehre to postmodernist architecture with its self-conscious borrowings from past traditions miss the spirit in which my work was composed. I doubtless contributed to the typecasting when, a few months after the premiere, I gave an interview to Jonathan Cott, comparing the piece to Philip Johnson's recently constructed AT&T building in New York. That was an inaccurate and misleading connection, because Harmonielehre lacks the cool, calculated irony of Johnson's Postmodernism. … If the work is a parody, it is a parody made lovingly and entirely without irony.Footnote 47

Nonetheless, several of the opera's numerous commentators have pointed to elements of parody, irony and satire. Matthew Daines, for example, has stated that irony ‘certainly seems to be what the creators were aiming at in Act I of Nixon in China’, that the Act II banquet scene ‘is well-suited to the parodistic purpose of Adams, Goodman, and Sellars’ and that Act I is a ‘parody of a grand opera that comments on the Reagan era’.Footnote 48 Similarly, David Schwarz, not letting the opera off the hook one way or the other, remarked that ‘[w]hile Nixon in China is obviously parodying Nixon's epic quest on so many literary and musical levels, the music is powerfully complicit in ideological structures of subject formation’.Footnote 49 With the following examples, I will suggest that musical allusion effectively served the purposes of satirical characterisation in this opera.

Adams sticks it to Nixon in Act I of the opera by accompanying the President's historic arrival on the tarmac outside Beijing with what resembles an enfeebled version of Wagner's sword leitmotif (Figure 2). (Perhaps the emphatic, brassy twelve-bar rhythmic motive of ‘Ride of the Valkyries’ – a dotted quaver and two semiquavers – heard as the jet approaches, suggests this subsequent Wagnerian allusion to my ear.) As Wotan conceives his ‘grand thought’ of a redeeming hero near the end of Das Rheingold, we hear the sword leitmotif for the first time in Wagner's tetralogy and we hear a similar gesture as Nixon arrives with his own ‘grand thought’ to open China. Or perhaps Nixon, like Siegmund, believes that he is the ‘chosen one’, the hero foretold. In Act I scene 3 of Die Walküre, the leitmotif is heard triumphantly as Siegmund pulls the sword from the tree to the accompaniment of semiquaver arpeggiation that resembles the accompaniment heard for Nixon's trumpeted arrival. However, Adams's theme seems to sputter to life, winding up for the upward thrust without quite sounding convincing. Nixon the character (and historical figure) may have felt heroic at this moment, but the musical allusion to Wagnerian heroism undermines him. Adams, however, has pointed to another source of allusion for this moment: ‘Air Force One … taxied onstage to the accompaniment of my stuttering brass tattoos and fractured version of “The Star-Spangled Banner”.’Footnote 50 Of course, the plane does not actually taxi onto the stage, but instead descends from above, and this alleged ‘Star-Mangled Banner’ melody lacks the distinctive opening descending arpeggio of the national anthem. The Adams and Wagner melodies share a more similar shape. Rather than confidently point to a specific source, we might turn here to Deryck Cooke's discussion of the inherent joyful expression imbedded within the intervallic pattern of Wagner's heroic leitmotif.Footnote 51 In any case, this arpeggiated material accompanying Nixon's arrival is not simply a neutral C major arpeggio, as the stuttered rhythmic utterance, instrumentation, dynamics, texture and dramatic context all signal an undermining of a would-be heroic moment.

Figure 2. The Nixons landing on Air Force One, Act I in John Adams's Nixon in China (Houston Grand Opera, PBS Great Performances, 1987 performance, screenshot). (colour online)

Adams's allusions to Stravinsky are both more prevalent and more intriguing.Footnote 52 Nixon in China lampoons the rote repetition of Chairman Mao's sayings, particularly as echoed by his three female secretaries, the Maoettes, near the end of Act I scene 2. Adams makes a direct reference to The Rite of Spring, specifically ‘The Augurs of Spring: Dances of the Young Girls’ section, to mark these Chinese women and their ritualistic and aggressive sloganeering (Examples 3a and 3b). Here Adams extracts half of the famous bitonal or octatonic Stravinsky chord as he closely approximates Stravinsky's ostinato quavers pattern with unexpected accents, although in a more constrained form, with the same articulation and at the same basic tempo.Footnote 53 (In effect, Adams selects the upper chord in violins and violas from Stravinsky and raises it a half-step, coming even closer to an exact quotation of Stravinsky when he adds a G$ on the accented beats some bars after he starts the ostinato.) This musical allusion may also suggest the sacrificial political rites of the Cultural Revolution.

Example 3a. Igor Stravinsky, ‘The Augurs of Spring. Dances of the Young Girls’, The Rite of Spring.

Example 3b. The doctrinaire Maoettes parroting Mao, Act I scene 2 in John Adams's Nixon in China (Boosey & Hawkes).

The doctrinaire intensity of the Maoettes is balanced somewhat by a more sombre and gentle musical depiction of Chinese women as victims, in which Adams once again evokes Stravinsky. In Act II scene 1, Pat Nixon is given a wide-ranging tour of Chinese sites. The Chinese beseech her to ‘look down, look down at the earth’, referring to rivers ‘caught in the hand of death’ and an ‘uncertain sun’, and near the end of the scene warn her to ‘watch your step’ (Example 4a). The musical setting of these lines is nearly the same as what Stravinsky composed for the nymphs in Perséphone (1934) as they entreat Persephone to remain with them and relax in the flower fields, enjoying the ‘tender embrace of the stream’ and the ‘sunlight sparkling on the waves’, but also warning her to ‘be on your guard’ (Example 4b). (Both Stravinsky and Adams employ the same chord – E-G-B-D – just before their choruses start and their choral melodies employ the same pitches and rhythms for a few bars.) Pat feels pity when observing a patient in a clinic and is told not to by the Maoettes; Persephone feels pity for the wretched inhabitants of Hades and is told in Part II not to by Eumolpus. Perhaps Pat Nixon, who forecasted the coming of spring heralded by ‘the west wind’ in the previous scene, is analogous to Persephone: she travels from the West to visit the drab, grey, icy hell of Communist China near the end of the Cultural Revolution. (She announced the arrival of spring again during the celebratory toasts at the end of Act I.) Thus, the musical allusions to both The Rite of Spring and Perséphone involve women and spring. Unlike Stravinsky's nymphs, the Chinese ask Pat to look at the ice and snow of their wintry world.

Example 4a. The Chinese inviting Pat Nixon to ‘look down’, Act II scene 1 in Adams's Nixon in China (Boosey & Hawkes).

Example 4b. The nymphs beckoning Perséphone to remain and rest, in Stravinsky's Perséphone (Boosey & Hawkes).

This possible allusion to Stravinsky's Perséphone seems convincing. However, there are other possible sources for both Stravinsky's nymph music and Adams's Chinese chorus in this scene. For example, Wagner's Flower Maidens in Parsifal, like Stravinsky's nymphs, beckon a heroic central character to remain with them in their flowery world with a similar musical gesture with pregnant rests in triple metre (Example 5). Stravinsky had attended and disparaged Parsifal in 1912, over two decades before composing Perséphone, though Adams's music comes closer to Wagner's Flower Maidens here. (Wagner's Flower Maidens, in turn, might well call to mind Mozart's music for the Three Ladies in Die Zauberflöte, particularly just before their first exit.) Though the possibility is intriguing that Adams drew on both Wagner and Stravinsky, even if only indirectly, or that all three composers happened to gravitate to a somewhat similar musical setting, the textual connections noted earlier point more directly to Stravinsky's nymphs as a source for Adams. What is less clear is the significance of this allusion. The association of Pat with an ancient Greek goddess may gently mock her inflated sense of importance, as she views herself as bringing a breath of fresh air and Yankee optimism to these downcast exotic people on the other side of the world. The ironic contrast between these Chinese citizens in their dismal landscape with the nymphs and their bountiful meadow is in line with the opera's generally unsympathetic portrayal of the Chinese.Footnote 54

Example 5. The Flower Maidens beckoning Parsifal, Act II in Wagner's Parsifal.

Andriessen's allusions to Thanatos, or, that sinking feeling again

For over fifty years Louis Andriessen has been viewed as a composer who alluded with an attitude. His received compositional personality is typically described with terms such as iconoclastic, ironic, cynical, detached, alienated, anti-sentimental and depersonalised, and he is most often classified as a post-minimalist, politically driven, eclectic composer who engaged ironically with past music in compositions that purport to be about music rather than about personal expression. Andriessen buttressed these views through repeated statements made in numerous interviews, in his writings on Stravinsky in particular, and in published discussions of his own works. However, we will find that he employed allusions, often carefully submerged or deliberately oblique, in his late opera La Commedia for the purposes of intensely poignant and personal expression.

In a 1978 article that prefigured much subsequent commentary on this composer, Willem Jan Otten and Elmer Schönberger went so far as to claim that irony and alienation were pervasive in Dutch culture and thus came naturally to Andriessen.Footnote 55 Writing about two of Andriessen's music theatre scores for the Baal Theatre Group, Mattheus Passie/Matthew Passion (1976) and Orpheus (1977), Otten and Schönberger declared that: ‘A composer who, like Louis Andriessen, chooses his own labyrinth in musical history, can only find the way himself; he always ends up back with himself again and this can be heard. In the end, making distinctions between style quotations, literal quotations, allusion and original music is not important.’Footnote 56 Of the Matthew Passion, they explained that the score offers

references and quotes in a musical minefield of irony, parody, paraphrase – in short, a commentary. The musical counterpart to the Baal group's alienation is apparent at all levels of the opera, ranging from the choruses with their remarkable discrepancy between a typical chorus-like method of scoring for four to eight parts and their soloist presentation, to the often perverse treatment of the text with wrong accents.Footnote 57

They noted that Andriessen did not quote past music directly in these works but only in fragments and that ‘reducing things to banality is only one of the functions of the musical commentary; another is cynicism and ridicule, nowhere so biting and sophisticated as in the blend of can-can and tap dance music in the dance of death in the first scene, based on the melody of the Dies irae’.Footnote 58 Otten and Schönberger concluded with the claim that ‘in the end, the Matthew Passion is a depiction of irony itself’.Footnote 59 The authors detected a somewhat different use of irony in Orpheus in which ‘the alluder has come out on top of the allusion … Allusion is anonymous and insignificant: the subject of the music is the music itself’, though they found that ‘the ultimate effect is still ironic’ and that the ‘irony in Orpheus is the result of a shrewd mixture of rhetoric and coarseness which goes so far that the same risk is run as in the Passion – a fruitless excess of irony, an empty play of paradoxes’.Footnote 60

More recent scholars of Andriessen's music have tended to follow suit in emphasising ironic expression and allusion throughout his œuvre. For example, Robert Adlington accurately describes Andriessen's earlier piece Anachronie I (1967) as ‘a witty patchwork of parodied musical styles’ and as a work that ‘delights in pitting pop songs, big-band jazz and clichéd film music against more “elevated” compositional styles’. Adlington points out that this piece was dedicated to Ives who served as an inspiration for Andriessen's career-long penchant for musical borrowing.Footnote 61 Likewise, Yayoi Uno Everett has analysed examples of ‘parody with an ironic edge’ in Andriessen's opera Rosa: The Death of a Composer, or A Horse Drama (1994), in which allusion to Brahms appears satirical, and in Writing to Vermeer (1998), in which Andriessen composed musical irony by adding dissonances to themes from Sweelinck.Footnote 62 Other commentators have been inspired to categorise Andriessen's music by its penchant for irony. Rokus de Groot claimed that Andriessen's explorations of irony in the mid-1990s enabled him to move fully into a postmodern aesthetic,Footnote 63 and Timo Andres has suggested that Andriessen is able to use word painting in La Commedia because there is something more generally ‘cartoonish, or Pop Art’ in his music that allows for such literalism.Footnote 64

Andriessen also discussed his use of musical allusions and interest in irony. In an investigation, co-written with Edward Harsh, of movement one of De Materie, he referred to his music as being in ‘constant engagement with past musics’ and stated that he used pre-existent music ‘purely for its structural properties’ – a rather modernist compositional objective frequently claimed by composers routinely labelled as ‘postmodernist’.Footnote 65 Andriessen and Harsh state that the use of past music in De Materie avoids simple quotation and is distinct from works by other composers in the 1960s and 1970s in which each musical quotation appeared ‘in a sort of museum case; a remnant unearthed by musical archaeology, unable to interact with its environment’.Footnote 66 Andriessen repeatedly noted the influence of Stravinsky on his music and how he even modelled his own approach to musical allusions to the past on Stravinsky's. Similarly, Andriessen appeared in some writings to derive his interest in composing music that is about music and that exhibits a sense of detachment from what he viewed to be Stravinskian aesthetics. For example, much of his book on Stravinsky – The Apollonian Clockwork, co-authored with Elmer Schönberger and published originally in Dutch in 1983 – focuses on Stravinsky's borrowings, including his imitations of Ravel, a composer Andriessen alluded to in his own works, and on Stravinsky's similarity in approach to copying to that of Bertolt Brecht.Footnote 67 Andriessen and Schönberger might well have been discussing Andriessen's own music when they concluded that ‘since the music of Stravinsky is concerned with so much other music, it can be said to be a music with a rich memory’.Footnote 68 They state that ‘every work of art is a kind of feigning’ and that artists who are aware of this and make ‘a subject out of feigning’ are ironists. Classifying Stravinsky as an ‘ironic buffo-composer’, they explain that the ironist without emotion can speak of death, not as tragedy but as ‘merely the confirmation of the insoluble absurdity of a world in which things are always contradicting each other’.Footnote 69

Multiple scholars and critics have detailed Andriessen's borrowings from Stravinsky, and I will reveal other significant examples later. For instance, Jonathan Cross points to echoes of The Rite in Andriessen's De Staat and, in a discussion of M is for Man, Music, Mozart, queries whether ‘Andriessen lived so close to Stravinsky for so long that his own music sometimes becomes little more than an unconscious assemblage of found Stravinskian objects?’Footnote 70 Andriessen repeatedly proclaimed his devotion to specific works by Stravinsky, particularly to The Rite of Spring, and emphasised that in his musical borrowing, Stravinsky's ‘attitude towards material’ served as a formative model, teaching Andriessen that ‘[d]istance is necessary to protect your vulnerability as a composer. Irony has to do with protecting your sentiments. And then you are freed for composing’.Footnote 71 I will explore the role of irony in ‘protecting’ Andriessen's ‘sentiments’ in my discussion of the rather poignantly tragic depiction of death in La Commedia.

Andriessen's aesthetic of detachment has deflected interpretive discussion of possible emotional expression and has instead prompted commentators to focus on political significance and intent in his music. These investigations are supported both by Andriessen's well-documented political activities and by his acknowledgement of Brecht as a model. Robert Adlington in particular has detailed the composer's early political engagement and associations and the importance of Brechtian aesthetics for Andriessen.Footnote 72 Though La Commedia does not appear to have been motivated by any specific political expressive goals, Andriessen's own early political activities are obliquely referenced.Footnote 73 In 1972, Andriessen was instrumental in founding a street jazz band called The Volharding (Perseverance). His politically charged Workers Union was premiered in a street performance in 1975. In Hal Hartley's black and white film contribution to La Commedia, which is screened as part of the staging of the opera, we witness the exploits of a street band in Amsterdam. These fictional disruptive and rowdy musicians, who end up in jail, point to but one of several clues to the autobiographical dimensions of this opera.Footnote 74 Though leftist political expression remains central to much commentary on Andriessen's music, in the past two decades an increasing focus on the topic of death in his work has prompted some scholars to reconsider his use of allusion. In these pieces, Andriessen appears rather alienated from his earlier Brechtian aesthetics and motivations and instead may even be understood to be indulging in personal emotional expression.

Surveying his entire career reveals a wide range of styles in his musical representations of mortality. Maria Anna Harley (formerly Maja Trochimczyk) has suggested: ‘[Andriessen's] preoccupation with the topos of death and dying – obvious in De Materie and triggered, in part, by an increasing awareness of his own mortality – continued through the 1990s and resulted in the creation of several compositions, such as Facing Death for amplified string quartet (1991), and The Last Day (1996) for choir and large ensemble.’Footnote 75 Andriessen's 1957 Elegy/Elegie for cello and piano is quite romantic and I detect no traces of irony. (Though this piece is early and divergent from the composer's core style, there are moments in La Commedia that resemble it closely.) Many of his death-focused works draw on allusions to earlier death-related music. For example, though he employed anarchistic text from Bakunin, which he said expressed his ‘political credo’, he also quoted the Dies irae at two bars before Rehearsal No. 49 in Mausoleum (1979), a work which is stylistically echoed in the Lucifer section (Part III) of La Commedia. The 1991 Lacrimosa for two bassoons, which was based on the eighteenth verse of the Dies irae, features numerous minor seconds and microtones in addition to mournful, sighing gestures, and the Garden of Eros (2002), dedicated to the memory of his brother Jurriaan, also employs the Dies irae chant as did ‘The Last Day’ movement of Trilogy of the Last Day (1997) at No. 21.

Concurrent with Andriessen's focus on representations of mortality was an evolution in his attitude towards irony and allusion. In late 1999 Andriessen explained that for him ‘Irony is basically melancholy and pain. That is what it is all about’, that melancholy and irony are ‘basically the same. They are each other's friends’, and he revealed that this perspective extended to his understanding of Stravinsky, for he found that ‘[e]very bar of Stravinsky's music is profoundly melancholic’.Footnote 76 He also referred to our knowledge of death as involving dramatic irony, a form of irony that is not necessarily jocular but, rather, is rooted in melancholy.Footnote 77 Interpretations of Andriessen's work have also shifted somewhat towards the view that his music is not anti-expressive and detached after all and that his use of allusion betrays emotional investment and genuine expression. This is reflected, for example, in Adlington's discussions of Andriessen's allusions. Adlington refers to Andriessen's attempts to employ quotation and stylistic allusion to avoid ‘the tyranny of subjective expression’, yet he rightly argues that the composer's musical allusions actually ‘intimately reflected Andriessen's own musical proclivities’ rather than achieving depersonalisation.Footnote 78 Adlington pushes back at Andriessen's professed artistic stance by noting that his allusions and quotations represent ‘very personal decisions’ that were not a matter of chance, that the allusions were ‘in essence statements of personal aesthetic preference’ and that Andriessen's ‘profound investment’ in the process of allusion suggests an autobiographical dimension in his pieces that allude and quote.Footnote 79 Ultimately, Adlington finds that many of Andriessen's allusions are actually ‘free of caricature or exaggeration, and indeed often seem notably affectionate’.Footnote 80 La Commedia reveals that the conjunction of ironic allusion and melancholic sentiment, death, the Requiem mass and the fatal figure of Orpheus remains central to Andriessen's late career music as well.

La Commedia is radically allusive, postmodern in its omnivorousness and moments of irony, and yet also deeply felt, particularly in its passages of heart melting beauty. The opera is excessively multilingual (Latin, Italian, Dutch, English) and draws on numerous literary sources for its libretto, including Dante's La divina commedia, the Bible, Vondel's Lucifer and Adam in Exile, and other early texts. The titles of Parts I and IV (‘The Ship of Fools’ and ‘The Garden of Earthly Delights’) point to the influence of Bosch's paintings on this work. The connections between the opera and Dante are particularly intricate.Footnote 81 As Andriessen explained: ‘My use of multiple languages is rather like a fairground where sideshows offer different aspects of personalities or multiple interpretations of the same thing.’Footnote 82 These multilingual texts are placed in dialogue with each other in each of the opera's five parts – at some points seeming to pick up the thread of discourse one to the next, at others seeming to speak a bit past each other. The production design of the opera presents a similar situation – the projected film and simultaneous live staging exhibit numerous moments of clear connection between each other and with the sung text, but, at other moments, they play out seemingly separate narratives.Footnote 83 In short, this opera proclaims its multiplicity in multiple ways: it is multi-authored, with electronic music by Anke Brouwer and concept and direction by the filmmaker Hal Hartley; multimedia, with one large screen and four smaller screens as part of the stage design, and a mostly silent film running concurrently and interspersed with the stage action; and multi-narrative and multi-representational, with the three principal live performers appearing also as characters in the film.

In her discussion of this opera's structure, Jelena Novak has emphasised the separation between the film and the staged ‘dramaturgies’ and declares that ‘the events that are represented by the film and by the live opera performance are not even referring to the same narrative’. She also asserts, despite the very close synchronisation between live music and the film at many points, and between the music and the movements of the live performers, that the ‘music does not accompany what happens on stage’.Footnote 84 In contrast, I find that the connections between stage action and the film run deep and that the film often clearly responds to specific images and references in the texts.Footnote 85 In the film, in addition to following a group of street musicians and two female political activists through the streets of Amsterdam, into a café, on a beach and in jail – as we witness their music-making, love affairs and quarrels – we also see a female television reporter covering the appearance of a female politician (or prominent public figure of some sort), with the reporter eventually accidentally killed by the politician's chauffeured car. In the Inferno section of The Divine Comedy, Dante's narrator serves as something of a reporter covering the underworld and offering a running parallel between the past and his current Florence. In the opera, the same female performer takes the roles of Dante on stage (wearing cardinal red) and the female reporter in contemporary Amsterdam on screen, just as the soprano depicting the politician on screen also takes the role of Beatrice on stage (wearing all white). For most of the film, the actor playing Lucifer on stage (costumed in a dark suit) appears to be depicting the same figure on screen, observing the antics of the musicians with both sardonic and dismayed reactions. (Virgil is represented through choral singing.) On stage, Beatrice makes several momentous appearances and Lucifer and Dante warily circle each other for much of the opera, until Dante's death in Lucifer's loving arms – a death that Lucifer laments. The live staging and physically present performers are framed as though related to but existing beyond the screened contemporary world, as though placed after that screened narrative has finished, with Lucifer viewing the filmed documentation with particular regret and with Dante confronting him on stage in Purgatory following the reporter's death.

Lucifer is clearly the central figure in Andriessen's opera and may loosely stand in for the composer himself. The set design suggests a large multi-level warehouse with workers sporting hard hats and uniforms. Lucifer asserts his authority here but does not actually appear to be the boss in this realm. A pit in the centre of the ringed stage area contains many translucent exercise balls, and the workers are focused on transporting individual balls via a pulley and cable. These balls likely represent individual souls that are transported from this Purgatory to higher realms. Lucifer breaks the fourth wall to address the audience, interacts with the orchestra members who appear as uniformed workers, roughly treats the worker characters on the set and is a keen observer of much of the screened action (whether from his vantage point on stage or from within the film). From the start, he appears to be stressed out, pained, disgusted, dismayed, flustered, anxious and a bit pathetic. In fact, Lucifer is either foreseeing the tragedy to come or is looking back, reliving it with anguish. In some spots, Andriessen composes a rather cartoonish version of Lucifer with tritones (which word paint the word ‘abyss’) and a honking contrabass clarinet (e.g., Part 1, No. 51, Example 6) marking him in a way that reminds me of Stravinsky's use of a bass clarinet for Pluto in Perséphone.

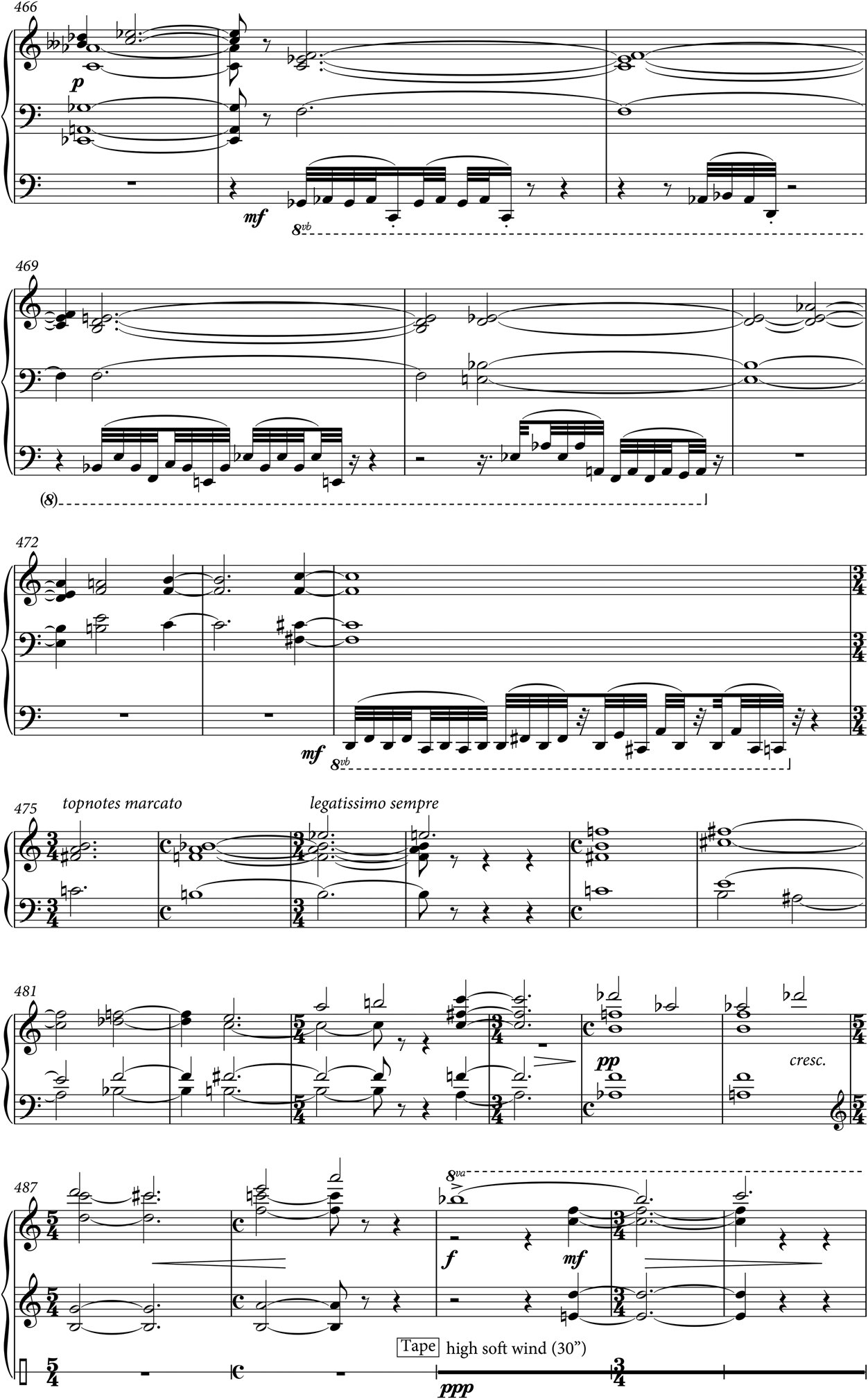

Example 6. Andriessen's allusions to Tristan and Madama Butterfly, with Lucifer's contrabass clarinet line as well, Part IV, La Commedia (Boosey & Hawkes).

Near the end of Part III we arrive at Lucifer's big moment. He releases a ball that was set to be transported up via the pulley system and holds it aloft, hugs it and later will even hump it sexually. Carrying the ball, he raises himself on a lift far above the stage before delivering a rant against God and man (Figure 3). The demons/musicians on screen appear tightly packed together as they gaze upwards at Lucifer from their circle of hell/prison as he addresses them. His music turns briefly glorious, with a swirling texture and bell-like timbres in the orchestra, but the feeling cannot last. We see the female politician in white glancing back over her shoulder and waving onscreen – a repeated backwards Orphic glance that will prove fatal. The live actor playing Lucifer waves back, further connecting the world of the stage with the world of the screen. In the final section of Part III, labelled ‘Lucifer's triumph’, the devil does not sound at all triumphant but is rather crushed. Lucifer is clearly upset about his own downfall and the approaching death of Dante, a character/voice which partway through Part IV is suddenly relabelled ‘Cristina (as a folksinger)’ in the score – a discrepancy with the libretto. This renaming points to the actual performer of this role, Cristina Zavalloni, but more significantly, in my interpretation, perhaps represents a deliberate emphasis on this Dante's female gender.Footnote 86 Indeed, this move was prefigured when Lucifer concluded Part I with a line from The Inferno in which Andriessen switched Dante's word ‘he’ to ‘she’: ‘I was certain that she was sent from heaven.’Footnote 87

Figure 3. Lucifer holding Dante's soul aloft, Part III in Louis Andriessen's La Commedia (Koninklijk Theater Carré, Amsterdam, 2008 performance, Nonesuch Records DVD, screenshot). (colour online)

In Part IV, Dante clearly disapproves of Lucifer's actions and seizes the ball from him so that a worker may return it to the pulley system to be carried aloft. Dante's soul will now ascend and she will die – this is signalled musically by a low and ominous pedal point. Lucifer senses her impending doom and attempts to make the sign of the cross, though everyone in contemporary screened Amsterdam and in the staged Purgatory appears to have forgotten how to perform this gesture. Beatrice portentously signals to Dante on stage to stop moving as Lucifer hunches over in remorse. The reporter on screen and Dante on stage also fail in the attempt to make the sign of the cross. Lucifer gently rests his head against Dante's during her final line and then cradles her collapsed dead body in his arms – a moment of intense and poignant beauty, a moment of Thanatos (Figure 4). The musicians on screen attending the public appearance of the politician dramatically turn their heads to glance over their shoulders at the tragic event, and the camera cuts to the body of the reporter lying in the street.

Figure 4. Lucifer bearing the body of Dante and following Beatrice, Part IV in Andriessen's La Commedia (Koninklijk Theater Carré, Amsterdam, 2008 performance, Nonesuch Records DVD, screenshot). (colour online)

Before turning to the music heard at this poignant moment, it will prove critical to my ultimate interpretive claims first to consider Andriessen's musical allusions throughout the opera. As in the case of John Adams, Andriessen's allusions in La Commedia range from near quotations to rather deeply buried resemblances. In this score, Andriessen includes near quotations of Stravinsky, Ravel and Debussy, clear allusions to Wagner and Messiaen, to 1940s big band and Bebop jazz, to twisted nursery rhyme ditties and to a general late twentieth-century medievalist style. Some of these allusions appear briefly and without clear signification, functioning as part of a general collage of styles, but others involve a more sustained modelling on a specific source and suggest symbolic meanings. A focused hermeneutic approach to musical allusion proves key in uncovering the expressive depths and plausibly autobiographical dimensions of Andriessen's La Commedia.

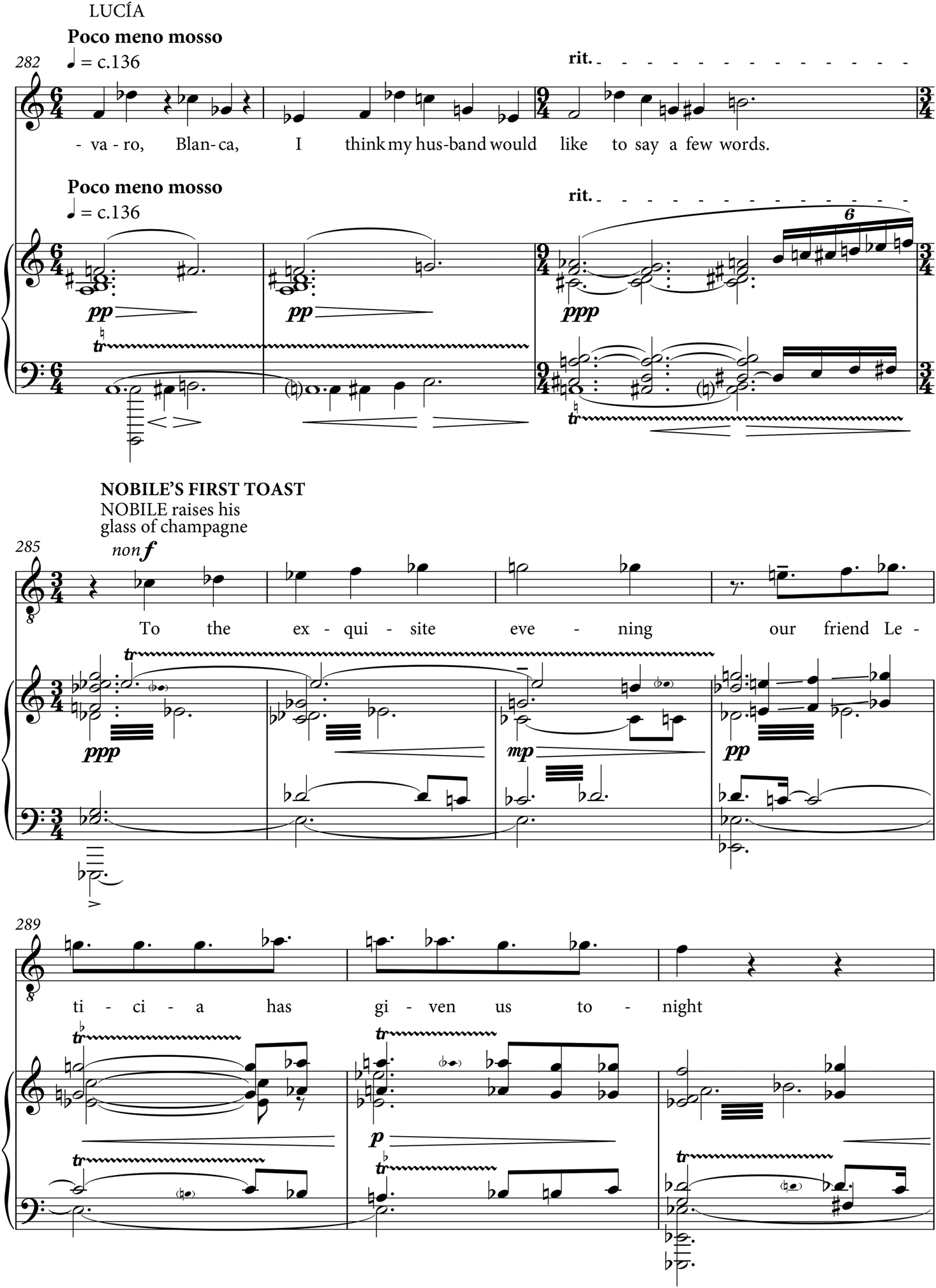

Perhaps to highlight the spiritual and religious aspects of the opera, Andriessen alludes at several points in Part I to the music of the equally omnivorous, though more devoutly Catholic, composer Olivier Messiaen.Footnote 88 Messiaen's avian melodic style appears at bars 133–4 and particularly at Nos. 40 to 42 (which resembles Messiaen's Turangalîla-Symphonie at No. 21), where Andriessen labels the synthesiser part as representing ‘more than thousand angels falling from heaven’. Andriessen nearly quotes Messiaen's Turangalîla at No. 27 as well, but without any apparent connection to the text. His near quotations of Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring in Part II of La Commedia (e.g., see No. 46; also compare Nos. 17–18 with Stravinsky Nos. 151–3 and 162–4) similarly seem unmotivated by the text. Though these allusions are heard in association with descriptions of the violent demons, and a young woman is sacrificed in both works, we should keep in mind that Andriessen echoes The Rite frequently throughout his œuvre. Other isolated moments of stylistic resemblance in the score also prove suggestive though inconclusive in terms of intent. Beatrice's celestial high soprano entrance in Part I is accompanied by clusters in the orchestra that closely resemble the pitch clusters and timbre of the Japanese sho – an instrument that Andriessen emulates in other works. The description of the marching demons near the end of Part II (‘Along the left bank they set off … and he made a trumpet of his ass’; ‘sometimes with trumpets, and sometimes with bells, with drums and with signals from the castle’) inspired Andriessen to write a nasty, brassy, highly dissonant wrong-footed march (Nos. 41–3) worthy of Shostakovich. As the basses sing Virgil's lines in Part I, at the moment when he points to the approach of the boat across the ‘dirty waves’ (No. 32), their rocking melody oscillates between minor and major second intervals with demisemiquavers, which resembles a speeded-up version, with even some melodic overlap in pitches, of the music for the male chorus in Britten's Curlew River (Nos. 9–10) as they describe the flowing river with quaver-note major second oscillations.