Introduction

In recent decades, Montenegro has undergone dramatic economic, political and social changes. The disintegration of Yugoslavia, the wars and conflicts in the neighbouring ex-Yugoslav republics in the 1990s, the imposition of UN sanctions, the experience of hyperinflation in 1993, and the adoption of the Euro as the official currency in 2002 and restoration of the independence of the country in 2006 are only some of the most critical events in this extended transition period. The transformation of the economic structure and the deindustrialisation of the economy have significantly affected the labour market situation. Large industrial enterprises and plants were closed due to economic circumstances, global trends and increased competition, and many industrial employees lost their jobs. In contrast, the demand for workers in the service sector has increased. National strategies and plans have targeted the problem of structural unemployment. However, the focus of these policies was on job creation, which was the main indicator of labour market performance. The social position of employees was less analysed, and in-work poverty (IWP) in Montenegro was neglected.

Newly published data shows that in 2020, the IWP rate in Montenegro was 9.8 per cent, which is the highest among all ex-Yugoslav countries. In addition, Montenegro has recorded an increase in the IWP rate while all other ex-Yugoslav countries have registered a decrease of this indicator. In order to analyse in detail the reasons for observed differences we will focus our analysis on comparison of Montenegro with Slovenia and Serbia. Slovenia was chosen because it is one of the most developed ex-Yugoslav countries and is a current EU member state. Serbia was chosen because Montenegro was in a state union with this country for a long time. This article aims to provide a comprehensive overview of IWP in Montenegro in this comparative context. As IWP is a major problem affecting specific groups of the labour force, the article will focus on different labour force categories and the policies that directly or indirectly impact their exposure to poverty. Specifically, the article will focus on an analysis of the policies that influence the incomes of these population groups: minimum wage policies, family policies and taxation policies.

Research on IWP in Montenegro

Despite the growing interest of researchers worldwide on IWP, the literature dealing with this phenomenon in Montenegro is scarce. One of the first assessments of IWP was the Human Development Report: Montenegro Society for All (UNDP, 2009), which provided the first comprehensive analysis of social exclusion in Montenegro. It was based on a household survey, and it revealed that 6.7 per cent of households in which the head of the household was employed were at risk of poverty.

A recent report of the European Social Policy Network identified the role of the minimum wage, social assistance through cash benefits, parental leave, subsidies in education, lifelong learning initiatives and housing initiatives in reducing IWP (Kaluđerović & Golubović, Reference Kaluđerović and Golubović2019).Footnote 1

The literature related to poverty in Montenegro rather indirectly assesses factors and policies connected to IWP. Part of this literature is focused on the general situation in the labour market, the efficiency of active labour market policies and the issue of informal employment, and stresses the fundamental role of employment in the reduction of poverty. Employment is emphasised not just as source of status, but also as a significant source of income, social support, and participation in society. On the other hand, many Montenegrins with low employability are exposed to poverty and social exclusion (Bejaković, Reference Bejaković2021). A similar emphasis is found in an earlier study (Institute for Strategic Studies and Prognoses, 2010). Other literature focuses on aspects such as social protection and social inclusion (Kaludjerovic et al., Reference Kaludjerovic, Sukovic, Krsmanovic, Vukotic, Golubovic and Vojinovic2008), or the position of specific vulnerable groups (UNICEF, 2012).

In line with findings from other countries (Marx & Nolan, Reference Marx and Nolan2012), the highest IWP risk is observed among households with very low work intensity and households with two adults and three or more children (Kaluđerović & Golubović, Reference Kaluđerović and Golubović2019). Gender stereotypes, prejudices, and a traditional division of gender roles may influence the extent of IWP in the more traditional segments of Montenegrin society (Duhaček, Branković, & Miražić, Reference Duhaček, Branković and Miražić2019). The position of women is also influenced by the reduction in average household size and the higher presence of single-parent households during recent decades (Kaluđerović, Reference Kaluđerović2018).

Some studies show that IWP is higher among those with a lower level of education (Ahrendt et al., Reference Ahrendt, Sándor, Jungblut, Anderson and Revello 2017; Spannagel, Reference Spannagel2013). One study on Montenegro links education and skills with employment opportunities, and hence indirectly with IWP (Golubović, Reference Golubović2019). Marginal groups are often excluded from better-paid jobs and from associated opportunities to exit IWP due to prejudice and stereotyping. According to research carried out by the Centre for Democracy and Human Rights (2017), discrimination in Montenegro was about 6 per cent higher in 2017 than 5 years previously. Ethnic minorities such as Roma and EgyptiansFootnote 2 as well as disabled persons often face economic and political marginalisation through discriminatory educational and cultural practices (Ministry of Justice, Human and Minority Rights, 2021). The lack of education and prejudice towards these people are significant obstacles to their finding better paid jobs.

Policy responses to IWP have rarely been the subject of systematic research or evaluation. However, ESPN country reports from 2019 on IWP for Montenegro, Slovenia and Serbia emphasise the importance of minimum wage policies, labour market, and social policy for IWP both in general and for specific population groups.

Comparative analysis of IWP data

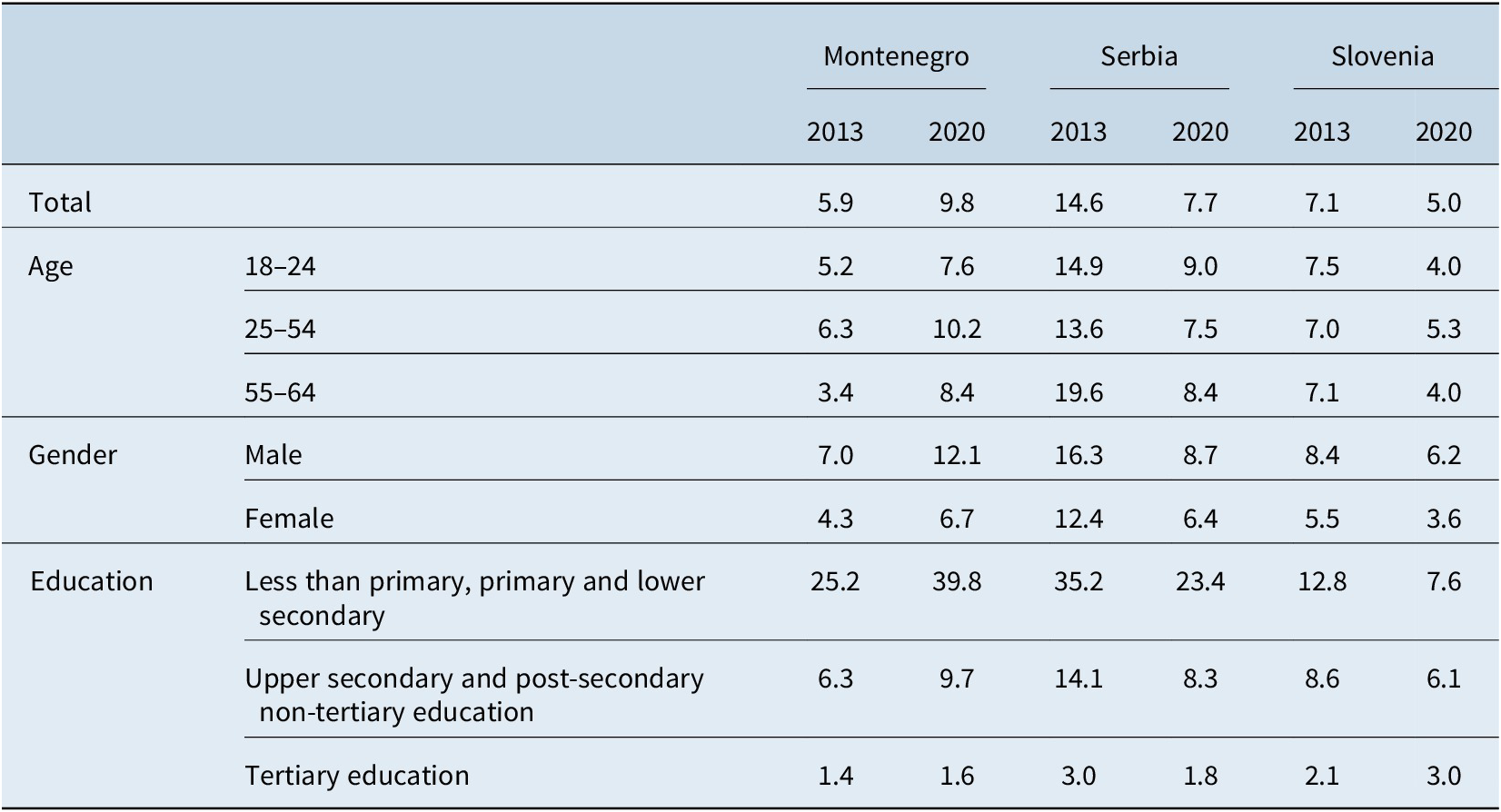

In Montenegro, people in the 25–54 age group face the highest risk of IWP, while those between 18 and 24 record the lowest IWP rate in 2020. Slovenia has low IWP rates for all age cohorts and the differences between them are relatively small. Contrary to Montenegro, in Serbia the youngest age group (age 18–24) has the highest IWP rate. However, the differences between IWP rates between Serbia and Montenegro for the age group 18–24 are not significant, at 9 per cent in Serbia and 7.6 per cent in Montenegro in 2020. From 2013 to 2020) the IWP rate for each age cohort in Montenegro increased, while in Serbia and Slovenia it decreased.

Gender differences in the at-risk-of-poverty rate are found in Montenegro, Slovenia and Serbia and are expressed in lower IWP rates for women than for men. However, these gender differences are much higher in Montenegro and Slovenia than in Serbia, being almost twice as high for men than for women in 2020 in those two countries (Table 1). Yet, by 2020 the IWP rates were higher for both men and women in Montenegro than in Serbia and Slovenia.

Table 1. Selected individual IWP factors for Montenegro, Serbia and Slovenia.

Source: EUROSTAT database, Income and Living Conditions data, accessed on 25 June 2022.

The at-risk-of-poverty rate decreases with increasing levels of education among employees in all three countries. In Montenegro, the IWP rate for persons with less than primary, primary and lower secondary education was 39.8 per cent, while in Serbia it was 23.4 per cent and in Slovenia it was only 7.6 per cent. In addition, the highest IWP rate for upper secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education is in Montenegro, but differences with Slovenia and Serbia are not so evident as in the case of the less educated. On the other hand, Montenegro has the lowest IWP rate among persons with tertiary education. Sectors that register lower wages (eg. accommodation and food service activities) tend to employ less educated workers, who are highly exposed to the risk of IWP.

Household factors (such as work intensity, household size and composition, or other factors) can significantly impact exposure to IWP risk. Lower intensity of work of a household is accompanied by a higher risk of IWP in Montenegro but also in Slovenia and Serbia. In 2020 the risk of poverty for those living in very high work intensity households was 2.2 per cent in Montenegro, slightly lower than in Serbia (2.7 per cent) and Slovenia (2.9 per cent). For those households that have low work intensity, IWP rates are much higher, exceeding 30 per cent in all countries. The reason for the greater IWP risk among households with low work intensity may be that some working adults are less able to increase their working time for various reasons, such as care of dependents. Women in such households are more likely to be secondary income earners (Iacovou, Reference Iacovou, Atkinson, Guio and Marlier2017; Ponthieux, Reference Ponthieux, Lohmann and Marx2018).

Household type is also a factor influencing poverty risk. The number of dependents plays a crucial role in IWP in Montenegro unlike Serbia and especially Slovenia. The IWP rate for a single person family without dependent children is lowest in Montenegro (4.9 per cent in 2020) while it is 10.9 per cent in Slovenia and 8.7 per cent in Serbia. On the other hand, the IWP rate for a single adult household with dependents is highest in Montenegro at 2.5 per cent in 2020, while rates for Slovenia and Serbia are significantly lower. Having dependent children also increases the risk of poverty for families with two parents, and again this increase is most evident in Montenegro (Table 2).

Table 2. Selected household IWP factors for Montenegro, Serbia and Slovenia.

Source: EUROSTAT database, Income and Living Conditions data, accessed on 25 June 2022.

The employment situation of individuals also affects poverty status. The self-employed face a much higher risk of poverty than employees in all three countries. However, Montenegro registered the highest IWP rate for the self-employed in 2020, at 22.8 per cent. Although the overall IWP rate is lower for women than for men in all three countries, Montenegro is the only country in which IWP rate for self-employed women is higher than IWP for self-employed men. In all countries, part-time workers face higher risk of IWP. However, the IWP rate for these workers increased in Montenegro during the last few years, from 8.9 per cent in 2018 to 35.9 per cent in 2020, which is higher than in the other countries.

Therefore, in Montenegro, IWP appears to be exceptionally high in comparison with Slovenia and Serbia in relation to the following groups: (1) early school leavers, (2) single parents and (3) the self-employed. Low earnings and low wages are the main causes of IWP for all these groups. Therefore, we will explore what affects their level of earnings. We analyse different policies with the most significant impact on income such as minimum wage policies, the system of contracts and forms of collective bargaining, to identify why these factors lead to exceptionally high outcomes in Montenegro. We also explore whether family policies that impinge on IWP are different in Montenegro compared to other countries in the region.

Policy context of IWP

Minimum wage policy

Although some studies (Joyce & Waters, Reference Joyce and Waters2019) have shown that the effect of the minimum wage on IWP is small, the literature on IWP in Serbia and Slovenia shows that the minimum wage is the most effective tool for preventing IWP (Pejin Stokić & Bajec, Reference Pejin Stokić and Bajec2019; Stropnik, Reference Stropnik2019). Previous research has also suggested that the minimum wage might also be the most effective tool for reducing IWP in Montenegro (Kaluđerović & Golubović, Reference Kaluđerović and Golubović2019), but as we show below it has not been a very effective in doing so Reference Kaluđerović and Golubović2019. It is determined by collective bargaining institutions and tends to protect labour market insiders.

Since 2008, when it was introduced in Montenegro, the minimum wage has changed several times (Table 3).

Table 3. Minimum net wages in EURO in Montenegro, Serbia and Slovenia.

Source: Statistical Offices of Selected Countries.

Although the minimum wage is assumed to be the basic protection mechanism against IWP in all three countries, its level varied with the different intensity of its adjustment among them. Thus, in the period 2013–2020, the minimum wage in Montenegro increased by only 14.9 per cent and the only increase occurred in 2019. In the same time interval, a significantly larger increase in the minimum wage was recorded in the other two countries. Thus, in Serbia, the minimum wage increased by 48.9 per cent, while in Slovenia it increased by 20 per cent. These differences were reflected in the IWP rates. The differences between Montenegro and the other two countries stem primarily from the manner of determination and adjustment of the minimum wage itself, which played an important role in reducing IWP during these years.

Insight into the minimum wage adjustment policy indicates that the difference between Montenegro and the other countries is that, despite the existence of such a policy, there was no continuous adjustment of the minimum wage in Montenegro as took place in the other countries. Although the legislation related to the minimum wage was based on the definition of the minimum wage as a percentage of the average wage, the laws provided a mechanism for a regular annual adjustment of the minimum wage based on various criteria (eg. the growth of GDP and the growth of wages). However, later regulatory changes in the three countries (mostly since 2013) went in the direction that the law itself recognises the obligation to set the minimum wage on an annual basis by decree of the government (based on the government’s proposal after consultations with social partners). This was not case in Montenegro, where the minimum wage for years remained defined by the Labour law from 2011 at the same level and defined as a minimum of 30 per cent of the average wage from the previous semi-annual period.Footnote 3 Setting the minimum wage in 2013 to around 40 per cent of the average wage led to the absence of new adjustments in the years that followed because formally the legal lower level of the minimum wage was met. Thus, there was a discontinuity in terms of the regular adjustment of this salary, while the work of the Social Council on this issue was passive and meaningless.

Thus, maintaining the minimum wage in Montenegro at the same level during the period 2013–2018 had a significant impact on the increase in total IWP rates in Montenegro. This has also led to the fact that the amount of the minimum wage as a ratio of average gross wages in Montenegro decreased from 39.7 per cent in 2013 to 37.6 per cent in 2018, while in other countries the policy of continuous adjustment allowed this indicator to remain stable in the same period (about 50 per cent in Slovenia) and from 44.4 to 47.8 per cent in Serbia. In the period after 2018, Montenegro increased the minimum wage in 2019 and 2021, but again with no changes in 2020, while the other two countries continued to increase the minimum wage each year.

The consequence of the different way of adjusting the minimum wage, and the absence of a continuous increase in this wage in Montenegro during the 5-year period is best reflected in the comparison of net minimum wage in Montenegro as a percentage of net minimum wage in the other countries. During 2013, the net minimum wage in Montenegro was significantly lower than in Slovenia (at only 33 per cent of the minimum wage in this country) while it was significantly higher compared to Serbia (109 per cent). However, until 2018, due to the absence of minimum wage adjustments in Montenegro, the situation changed. Thus, the minimum wage in Montenegro amounted to 30 per cent of the minimum wage in Slovenia and 89 per cent of the minimum wage in Serbia. This largely explains the opposite trends in the movement of the total IWP rate in Montenegro and other countries during the observed period.

Also, EUROSTAT data indicate that Montenegro is in the worst position when it comes to low-wage earners as a proportion of all employees. Available data for 2014 indicate that this percentage was the highest for Montenegro (27.2 per cent), while it was the lowest in Slovenia (18.5 per cent). All three countries had significantly reduced the share of low-wage earners by 2018, while there is no data for Montenegro.Footnote 4 However, comparing the data from MONSTAT on the number of employees and the data of the Tax Administration for that year, it can be concluded that the percentage of low-wage earners was about 40 per cent higher in 2018 than in 2014 . However, it should be noted that this may be affected by the existence of a large informal economy where, for some of the lowest paid workers, there is a difference between the recorded and the actual salary paid by the employer.

People who work part-time are particularly exposed to the risk of IWP in Montenegro. The data for Montenegro indicate that the IWP rate for those persons in 2020 was as high as 35.9 per cent and is much higher in comparison to comparative countries (15.2 per cent in Serbia and 10.2 per cent in Slovenia). This suggests a high probability that people working part-time in Montenegro are to a large extent minimum wage earners. Among them, less educated persons dominate, who are especially recognised as a vulnerable group. World Bank and WIIW (World Bank & WIIW, 2019) analysis on Western Balkan labour market trends showed that the level of education and exposure to low wages are strongly inversely correlated. This finding is especially pronounced in Montenegro. Data shows that moving from a low to a medium level of education in Montenegro reduces the risk of being a low-wage worker from 61.8 to 35.4 per cent. Surprisingly, the type of contract (temporary or permanent) does not have much effect on IWP in Montenegro. This is not the case in the other two countries. This is due to the established practice in Montenegro according to which employers sign repeated temporary contracts with long-term employees over several years trying to avoid signing permanent contacts with them. Also, changes in labour legislation in 2011 introduced temporary work agencies. These agencies were often abused by employers who used them as a tool to extend fixed-term employment contracts even when not allowed by law.

In addition, the prevalence of part-time employment continued to decline in the Western Balkans, but not in Montenegro (World Bank & WIIW, 2019). Also, according to EUROSTAT data, a higher percentage of part-time workers experience involuntary part-time work in Montenegro than in Slovenia (30.7 compared to 4.7 per cent in 2019) although the rate was somewhat lower than in Serbia (37.2 per cent). LFS data for Montenegro shows that a large majority of part-time workers in 2019 worked in sectors which do not demand a highly educated labour force such as agriculture, construction and trade. This attachment to part-time positions in Montenegro indicates that it largely refers to early school leavers who, due to numerous disadvantages and a poor material position, must accept part-time jobs, which are generally lower paid.

Family policy

In this section, we discuss different aspects of family policy such as in-work benefits, family income support, childbirth grant, child allowance and wage compensation during parental leave.

In-work benefits are not provided for low-wage earners in Montenegro and the situation is the same in Serbia, which also does not provide in-work benefits for low-wage earners (Pejin Stokić & Bajec, Reference Pejin Stokić and Bajec2019). However, in Slovenia the situation differs. In-work benefits are the same for employees on both permanent and fixed-term contracts, and they are almost the same for persons working full time or part time. All employees are entitled to the same number of days of annual leave, while the pay for annual leave is proportionate to the hours worked. The transportation to work allowance is awarded according to the same criteria, and the meal subsidy is the same for all employees (Stropnik, Reference Stropnik2019).

Low wage earners are not eligible for social benefits in Montenegro since, in order to receive the benefits, a person must be unemployed. The Montenegrin Law on Social and Child Protection defines the criteria for different social benefits. Among them, the most important one is material support (social assistance) which is a means tested benefit based on an income test and an assets test. Material support beneficiaries are allowed to exempt a part of their income from the means-test, such as child allowance, birth grant, and unemployment benefits. Although the Law is generous in terms of the income that is not included in the threshold, the threshold is very low, amounting to EURO 63.39 for a single household and EURO 83.30 for a two-member household in 2021. The threshold as well as the level of benefit is adjusted half-yearly (at the beginning of January and at the beginning of July of each year) with the movement of the cost of living and the average salary of employees based on statistical data for the previous half-year. In Slovenia, the working population is eligible for cash social assistance if their income is below a defined threshold level.Footnote 5 In addition, cash social assistance beneficiaries are allowed to exempt a part of their income from the means-test (Stropnik, Reference Stropnik2019). In Serbia right to financial social assistance is universal, irrespective of employment status.

The status of single parent households in Montenegro is difficult, as they are faced with numerous challenges from limited financial means to a lack of support in raising children. Of all divorces, around 60 per cent in Montenegro are in families with children. According to the 2011 census, there were 13,989 single parents with dependent children (2,652 fathers and 11,337 mothers), or 14 per cent of families. The number of single parents is increasing due to an increase in the number of divorces from 2011–2020, which has led to a significant fall in the size of the average household compared to previous decades (Kaluđerović, Reference Kaluđerović2018). This has reduced the redistributive impact of the household as the ability to pool income from multiple sources decreases. Only one in three parents pays alimony in Montenegro, which puts additional pressure on single-parent families. In Montenegro, there is no state mechanism that supports these parents in the event of no alimony payments being received, and a mother who does not receive alimony payments from the father is required to formally sue the father in order to be eligible to receive social benefits instead. This may put additional pressure on single parents to accept lower paid jobs or part time jobs in order to secure any source of household income. Single parents in Montenegro are eligible for social benefits on the same conditions as any other person, that is, in the case when the income of the family is below the defined threshold level (EURO 83.3 for a two-member family in 2021) and when they are unemployed. Thus, working single parents are not eligible for income support and in most of the cases do not have support from another parent, which all increases their exposure to poverty. In contrast, in Serbia child allowance is means tested but that single parents are entitled to 30 per cent higher benefit and have a 20 per cent higher eligibility threshold (Pejin Stokić & Bajec, Reference Pejin Stokić and Bajec2019). Slovenia has a policy that particularly targets those with a lower income, since child allowance rates differ by income group and birth order and are highest for the lowest income groups, both in absolute terms and relative to other social transfers and to the minimum wage.

In terms of child-related benefits, the birth grant, child allowance and wage compensation during parental leave may be used by working parents. The birth grant or benefit for a new-born child is a universal benefit in Montenegro for each new-born child; in June 2021 it amounted to EURO 116. This measure also exists in Serbia and Slovenia and is also universal. However, as it is one-time cash support, it does not provide significant income support. On the other hand, the child allowance does represent a significant contribution to family income. In Montenegro this used to be a means-tested benefit conditioned by material support. However, from September 2021, child allowance is provided to all children under the age of six, whatever the household social status is. Before this change, only up to three children who received material support (or personal disability allowance and other care allowances) were eligible for this kind of support. This means that employed single parents did not receive the child allowance which additionally contributed to their lower income and higher a IWP rate of this population group.

Also, in addition, wage compensationFootnote 6 during maternity or parental leave covers many of those exposed to IWP risk such as self-employed or part-time workers. The wage compensation in Montenegro depends on the actual salary of the beneficiary and the length of the work record and is capped at two average wages in the preceding year. For example, if employment has lasted for 12 months or more, the employer is reimbursed with the average income of the employee over the 12 months preceding the month when the right to maternity or parental leave was acquired. In addition, reimbursement of salary for half-time work is also provided. Similar policies are observed in other countries, with slight differences in terms of contribution history and level of compensation. For example, contribution history in Slovenia requires that a person has to have been covered by parental protection insurance (which is part of social security) just prior to the first day of the leave, or for at least 12 months in the last 3 years before the start of the leave. In Montenegro contribution history ranges from 3 months (30 per cent of average salary refunded) to 12 months (total average salary refunded) for the salary to be refunded by the state.

Although the assumption regarding the indirect connection between childcare and IWP at an individual level has been confirmed by a study conducted for EU countries, no relationship can be established between formal childcare usage and IWP at the country level, mainly because families that use formal care tend to be families with higher levels of work intensity (Ahrendt et al., Reference Ahrendt, Sándor, Jungblut, Anderson and Revello2017). However, analysis of differences between the systems among our three countries may provide some useful policy recommendations. Even though the preschool system is not compulsory in Montenegro, it is a universal right and the cost of children attending public preschool institutions is subsidised from the state budget. Parents pay only the cost of food (on average EURO 40 per month), while other costs are paid from the state budget (UNICEF, 2016). If this where not the case, parents would have to pay much more for childcare, which would represent a significant financial burden, especially for low paid workers and those with more children. In some cases, lack of this kind of support forces some family members (mostly women) to quit their jobs or to reduce their working hours. This situation lowers the household income and may push other employed household members towards a higher IWP risk. The situation regarding child care is similar in Serbia as in Montenegro and kindergarten fees are partially reimbursed for families with inadequate income. However, in both countries employed parents have more chance of having their child admitted, which may have an adverse effect on second earner in the family (Pejin Stokić & Bajec, Reference Pejin Stokić and Bajec2019). In Slovenia subsidies for early childhood education and care (ECEC) are means tested and are higher for low-income families. In general, family policies in Slovenia have played a central role in supporting high labour market participation among women through the development of a widespread network of childcare services, and the introduction of insurance-based social security schemes in the case of maternity (ie. maternity/parental leave) and other family-related benefits (eg. child benefits) (Hrast, Janković, & Rakar, Reference Hrast, Janković and Rakar2020). On the other hand, family policy was not an independent policy area in Montenegro and only those who are eligible for social and child protection in Montenegro can use the various forms of social benefits. The system is targeted mostly at those most in need focusing more on the individual than on the family, and therefore lacks the more integrated approach that can be found in Slovenia.

The self-employed are also recognised as one of the groups at-risk of IWP. A possible reason for the somewhat higher IWP rate among the self-employed in Montenegro is the existence of so-called “bogus” self-employment, which implies that some workers have the formal status of self-employed, but in essence are subordinate to their employer, and is used by employers to reduce their labour costs. Since, there are no policies aimed at the prevention of such occurrences there is little protection for such workers who are in a very unfavourable material position and are forced into such arrangements. On the other hand, in Slovenia since 2012, labour market policy has been aimed at preventing such occurrences and punishing disguised employment and “bogus” self-employment. Legislative changes have been initiated which foresee full labour law protection for the “bogus” (dependent) self-employed which treated them as if they had an employment contract (Stropnik, Reference Stropnik2019).

Self-employed women are particularly exposed to IRW risk. Some of the reasons for such a situation is the fact that self-employed women in Montenegro face numerous barriers which limit or prevent successful business operations. A survey showed that, in addition to the lack of funds, these barriers relate primarily to family duties, lack of understanding from the family or society, distrust of suppliers or the very fact that they are women (Despotović et al., Reference Despotović, Jokismović, Jovanović and Maletić2018). This is confirmed by analysis of the gender pay gap in North Macedonia, Serbia and Montenegro which showed that the “advantage” of women in labour market characteristics is higher in the public than in the private sector in Serbia and North Macedonia, while in Montenegro, men have better characteristics in the private sector and women in the public (Avlijaš et al., Reference Avlijaš, Ivanović, Vladisavljević and Vujić2013). A policy to provide support for these women to establish a balance between family responsibilities and business is lacking in Montenegro.

Taxation policy

Another aspect that is important for assessing and analysing IWP is related to income taxation policy. In Montenegro, income taxation has not played a significant role in reducing IWP, since a proportional system of taxation was applied with no non-taxable part of income, so the same tax rate was applied to different levels of income. The relatively high tax burden on work, which amounted to 39 per cent regardless of the amount of wage, directly affected low wage earners. As mentioned above, the majority in this group are less educated persons, which affected the IWP rate of this population group. In contrast to Montenegro, a different, more progressive, tax policy was applied in Slovenia and Serbia, where the tax burden on labour is lower for employees with lower wages. Tax policy changes in Slovenia introduced benefits for employees with low incomes that consisted of reducing the tax burden for all employees who receive lower wages compared to the national average net wage (Stropnik, Reference Stropnik2019). Similarly, in Serbia there is a non-taxable part of income, and the tax burden is lower for a lower level of salary (36.3 per cent in the case of payment of the minimum wage, 38.1 per cent in the case of payment of the average wage, while the tax burden is higher for a higher amount of salary) (Chamber of Commerce of Montenegro, 2021). Reducing the tax burden on low-income workers can contribute to the reduction of IWP, given that disposable income increases in this way. However, in 2022, when the implementation of the new fiscal program “Europa Now” began in Montenegro, the income taxation policy was changed by reducing the tax burden on labour. This implied the introduction of progressivity in personal income taxation policy, which also included the introduction of a non-taxable portion of earnings. The effects of this change in tax policy on IWP are still unknown. Nevertheless, it can be expected that the application of a tax rate of 0 per cent on gross wages below EURO 700 (which is an amount that is slightly lower than the average net salary) will have a favourable impact on the income of low wage earners, and thus result in a reduction in the IWP rate in Montenegro.

Conclusions

The phenomenon of IWP has gained policy importance in the EU and candidate countries over the past decade. Even though socio-economic developments in Montenegro over the past 30 years have significantly affected the position of workers, the focus of policy makers and the research community on IWP has been limited. By examining data obtained through the EU-SILC survey, this study offers an insight into IWP in Montenegro. Additionally, a comparative analysis was made with Slovenia and Serbia to identify those groups that are exceptional with regards to IWP in Montenegro and determine the impact of certain policies on the current situation.

IWP in Montenegro differs in comparison with Slovenia and Serbia in relation to the following groups: (1) less educated persons (early school leavers), (2) single parents and (3) self-employed, all having higher rates of IWP in Montenegro than in the other two countries. Low earnings and low wages are the leading causes of IWP for all these groups. Hence, we have analysed different policies with the most significant impact on income such as minimum wage policy and tax policy to identify why these factors lead to exceptional outcomes in Montenegro. We also explored whether family policies that impinge on IWP are exceptional in Montenegro compared to other countries in the region.

We conclude that main factors that have contributed to the higher IWP in Montenegro are the absence of the adjustment of the minimum wage for a long period of time, a lack of in-work benefits, low levels of means-tested material support (the main social benefit), child allowance conditioned on employment status, and a relatively high tax burden on earned income.

Through legislative decisions on the minimum wage in Montenegro, and since the institution of the Social Council has been passive, the minimum wage was effectively frozen for five years. On the other hand, in Slovenia and Serbia social councils played an active role in Slovenia and Serbia in the negotiation and regular annual adjustment of the minimum wage. Also, the analysis indicated that Montenegro has the highest percentage of low-wage earners. The combination of an absence of frequent minimum wage adjustments and the fact that Montenegro has the highest percentage of low-wage earners have led to an increase in IWP in Montenegro. In contrast to Montenegro, the trends of IWP were decreasing in the other countries. Hence, in terms of policies aimed at reducing IWP, key challenges in the future concern not only the level of the minimum wage, but also the large percentage of employees on a low wage.

The poverty status of those who work is also affected by the absence of in-work benefits in the case of Montenegro, as in Serbia. However, Slovenia has some in-work benefits kept from the previous system in former Yugoslavia which has contributed to lower IWP rates.

In Montenegro, benefits based on labour policies often exclude some rights to benefits based on social protection policies. For example, those who work are not eligible for family material support (social assistance), which is the main social benefit (means tested with very low income- and very strict asset-thresholds). In addition, the role of social policy is even more limited by the fact that some other benefits such as child allowance are conditioned by eligibility for material support benefit. Until 2021 in Montenegro, the child allowance was linked to family material support and working parents were not eligible. In Serbia and Slovenia, unemployment is not a condition for receiving cash social assistance. In addition, Slovenia has a social policy that provides higher benefits to those with a lower income, especially if they have children.

The analysis has showed the that position of women requires special attention in Montenegro, as they make up a majority of working poor single parents and the self-employed, often women, are more exposed to IWP. Different factors have contributed to this situation, but some that we have identified are a lack of effective alimony mechanisms and a lack of mechanisms that support women to attain permanent work, especially when they work in the private sector. Again, the case of Slovenia may be a positive example as, for decades, social and other related policies (such as childcare) were tailored to support women and their inclusion in the labour market.

In conclusion, although underdeveloped in policy discourse, IWP presents a real, permanent and complex problem in Montenegro, which is confirmed by the fact that Montenegro is an outlier in region. We have shown that the most affected population groups are the low educated, single parents (especially women) and the self-employed (especially women). Neglect of IWP as a real problem not only impacts on the effectiveness of social policies but limits the impacts of development policies and the maximisation of the overall socio-economic potential in Montenegro. Policy makers in Montenegro should be focused on policy improvements that may contribute to reducing IWP, including ensuring continual adjustments to the minimum wage with a more active role of the Social Council, removing the link between eligibility for social benefits and employment status, and introducing a more progressive income tax regime with a more substantial tax free allowance for low income earners.

Disclosure

The authors declare none.

Notes on contributors

Vojin Golubovic, PhD, is Teaching Assistant at University of Donja Gorica and researcher at the Institute for Strategic Studies and Prognoses, Montenegro. His research interests are labour market and social policy.

Milika Mirkovic, PhD, is Teaching Assistant at University of Donja Gorica and research at the institute for Strategic Studies and Prognoses, Montenegro. His research is in the fields of education and labour market.

Jadranka Kaludjerovic, PhD, is an Associate Professor at University of Donja Gorica and director of the Institute for Strategic Studies and Prognoses. She has broad research experience in the fields of social protection and social inclusion and labour market policy. She is the author of many papers in these fields.