Introduction

The term childhood adversity (CA) is a broad concept which includes child maltreatment (all forms of physical and/or emotional ill-treatment, sexual abuse, neglect or negligent treatment or commercial or other exploitation by an adult), peer victimization (e.g. bullying), experiences of parental loss and separation, war-related trauma, natural disasters, and witnessing domestic or non-domestic violence (Butchart, Putney, Furniss, & Kahane, Reference Butchart, Putney, Furniss and Kahane2006). CA is a major public health problem as it has been linked with increased mortality and morbidity rates (Gilbert et al., Reference Gilbert, Widom, Browne, Fergusson, Webb and Janson2008) and with long-lasting adverse consequences for mental health, including the development of depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), suicide, and substance misuse (Afifi et al., Reference Afifi, Enns, Cox, Asmundson, Stein and Sareen2008; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Murad, Paras, Colbenson, Sattler, Goranson and Zirakzadeh2010; Evans, Hawton, & Rodham, Reference Evans, Hawton and Rodham2004; Infurna et al., Reference Infurna, Reichl, Parzer, Schimmenti, Bifulco and Kaess2016; Li, D'Arcy, & Meng, Reference Li, D'Arcy and Meng2016; Norman et al., Reference Norman, Byambaa, De, Butchart, Scott and Vos2012; Simpson & Miller, Reference Simpson and Miller2002; Weich, Patterson, Shaw, & Stewart-Brown, Reference Weich, Patterson, Shaw and Stewart-Brown2009).

Psychotic disorders encompass various categories of severe mental disorders, including non-affective psychosis (e.g. schizophrenia), affective psychosis (e.g. bipolar disorder, mania or major depressive disorder with psychotic features), and other psychotic disorders (due to alcohol or substance use or to general medical conditions). Evidence suggests that psychotic symptoms refer to five broad domains: positive psychotic symptoms (e.g. delusions and hallucinations), negative symptoms (e.g. reduced drive and volition), cognitive alterations (e.g. memory or executive function impairment), depressive symptoms, and mania (van Os & Kapur, Reference van Os and Kapur2009). The role of CA in psychosis has recently been established: meta-analyses indicate that childhood maltreatment accounts for up to one-third of the individuals affected with psychosis (Varese et al., Reference Varese, Smeets, Drukker, Lieverse, Lataster, Viechtbauer and Bentall2012) and it is associated with an increased risk for subclinical psychosis and clinically-relevant psychotic disorders, in terms of both onset (Kraan, Velthorst, Smit, de Haan, & van der Gaag, Reference Kraan, Velthorst, Smit, de Haan and van der Gaag2015; Mayo et al., Reference Mayo, Corey, Kelly, Yohannes, Youngquist, Stuart and Loewy2017; Velikonja, Fisher, Mason, & Johnson, Reference Velikonja, Fisher, Mason and Johnson2015) and persistence (Agnew-Blais & Danese, Reference Agnew-Blais and Danese2016; Trotta et al., Reference Trotta, Murray and Fisher2015b). However, the prevalence of CA among patients with schizophrenia is not significantly greater than in patients with affective psychoses, personality disorders, and depression (Matheson, Shepherd, Pinchbeck, Laurens, & Carr, Reference Matheson, Shepherd, Pinchbeck, Laurens and Carr2013), suggesting that CA represents a common, rather than specific, risk factor.

A growing body of literature has investigated possible biological and psychological mechanisms, as well as the mediating or moderating role of other risk factors that might account for the link between CA and psychosis. Existing narrative reviews have focused on the effect of CA in individuals with a positive family history of psychosis or with particular genotypes, such as specific variants of BDNF or COMT (Ayhan, McFarland, & Pletnikov, Reference Ayhan, McFarland and Pletnikov2016; Uher, Reference Uher2014), and described the interaction of CA with cannabis use and adult life events or psychosocial stressors (Beards & Fisher, Reference Beards and Fisher2014; Parakh & Basu, Reference Parakh and Basu2013; Pelayo-Teran, Suarez-Pinilla, Chadi, & Crespo-Facorro, Reference Pelayo-Teran, Suarez-Pinilla, Chadi and Crespo-Facorro2012; van Winkel, Van Nierop, Myin-Germeys, & van Os, Reference van Winkel, Van Nierop, Myin-Germeys and van Os2013; van Zelst, Reference van Zelst2008). A role for insecure attachment styles, dysfunctional cognitive schema, reasoning biases, and non-psychotic symptoms has also been evidenced in the literature (Bebbington, Reference Bebbington2015; Freeman & Garety, Reference Freeman and Garety2014; Rafiq, Campodonico, & Varese, Reference Rafiq, Campodonico and Varese2018). Moreover, several mediating pathways linking CA with positive psychotic symptoms have been hypothesised, such as internal source monitoring processes and dissociation mediating the association between childhood sexual abuse and auditory verbal hallucinations, and reasoning biases and attachment insecurity mediating the relationship between neglect, parental separation, and persecutory delusions (Bentall et al., Reference Bentall, De Sousa, Varese, Wickham, Sitko, Haarmans and Read2014). These findings seem suggestive of an affective pathway to psychosis, linking CA to positive psychotic symptoms via psychological mechanisms and affective symptoms (Isvoranu et al., Reference Isvoranu, van Borkulo, Boyette, Wigman, Vinkers and Borsboom2017; Myin-Germeys & van Os, Reference Myin-Germeys and van Os2007).

In light of the growing body of literature in this area, this paper aims to systematically review the potential mediating and moderating factors involved in the relationship between CA and psychosis. For the purpose of this review, the definition of CA was limited to physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, as well as physical and emotional neglect, plus separation and parental death occurring prior to 18 years of age. In order to keep the review focused and maximize the effect of CA on psychosis, we did not include those studies where CA was only represented by indirect forms of abuse and maltreatment (e.g. parental discord, communication deviance, witnessing interpersonal violence) or by peer victimization (e.g. bullying). Informed by previous reviews, which suggested possible moderators and mediators of the CA – psychosis relationship (Ayhan et al., Reference Ayhan, McFarland and Pletnikov2016; Beards & Fisher, Reference Beards and Fisher2014; Bebbington, Reference Bebbington2015; Freeman & Garety, Reference Freeman and Garety2014; Parakh & Basu, Reference Parakh and Basu2013; Pelayo-Teran et al., Reference Pelayo-Teran, Suarez-Pinilla, Chadi and Crespo-Facorro2012; Rafiq et al., Reference Rafiq, Campodonico and Varese2018; Uher, Reference Uher2014; van Winkel et al., Reference van Winkel, Van Nierop, Myin-Germeys and van Os2013; van Zelst, Reference van Zelst2008), we will investigate the effect of genetic vulnerabilities, and biopsychosocial risk factors (e.g. substance use, adult life events and prolonged social stress), as well as psychological mechanisms (e.g. attachment styles), and non-psychotic symptoms (e. g. depression) as moderators or mediators of the effect of CA on psychosis. We refer to mediation as the mechanisms through which the effect of CA on psychosis may be explained (e.g. depression). We refer to interaction as the way in which the effect of CA on psychosis may be modified by the presence of another factor (e.g. a genetic polymorphism) (Baron & Kenny, Reference Baron and Kenny1986; Kraemer, Stice, Kazdin, Offord, & Kupfer, Reference Kraemer, Stice, Kazdin, Offord and Kupfer2001). Therefore, mediation studies help to clarify the biological or psychological mechanisms underpinning the CA-psychosis relationship that may be the targets for preventive intervention, while moderation studies identify the conditions under which an exposure influences a particular outcome and thus indicate vulnerable groups that might benefit most from these interventions (Wu & Zumbo, Reference Wu and Zumbo2008). Following the continuum model of psychosis (van Os, Linscott, Myin-Germeys, Delespaul, & Krabbendam, Reference van Os, Linscott, Myin-Germeys, Delespaul and Krabbendam2009) we will include studies of subclinical psychotic phenomena in members of the general population, as well as individuals at different stages of psychosis, i.e. individuals with prodromal symptoms of psychosis or at ultra-high risk (UHR), as well as those experiencing a first episode of psychosis (FEP) and those with non-FEP psychotic disorders. We acknowledge that since the role of CA in psychosis has been increasingly recognised, the literature on potential pathways linking CA with psychosis and moderators of this association has become quite vast, involving numerous possible mediators/moderators, study populations, study designs, and statistical models. This suggests that a summary of the existing literature might be challenging, but at the same time very much needed in order to identify potentially vulnerable populations and pathological mechanisms through which CA links to psychosis and, ultimately, to inform possible preventative and therapeutic interventions.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

A systematic review of the literature on biological, psychological, and social risk factors mediating or moderating the effect of CA on psychotic symptoms and disorders was carried out, following the PRISMA guidelines (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009), using the PsychINFO, Embase classic and Embase, Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily and Ovid MEDLINE(R) databases. Keywords related to (a) childhood adversities were connected with each other by the Boolean operator OR, and the same process was repeated for terms related to (b) psychosis, (c) mediation or moderation, and (d) specific mediating/moderating factors; second, the above four strings were connected with each other using the Boolean operator AND. The full list of the search terms used is provided in online Supplementary Tables S1 and S2 and was developed by LS who is an experienced librarian. A systematic database search from 1806 up to the 31st August 2019 was conducted. Database filters were applied to exclude articles published before January 1956, non-human studies and those without abstracts. Conference proceedings were also searched along with the reference lists of the selected papers to identify any additional relevant papers.

Studies were included if (a) they were original articles, (b) they were published in English, (c) they had a case-control, cross-sectional or cohort design, (d) they had psychotic disorders, psychotic symptoms, or psychotic/psychosis-like experiences (PLEs) as an outcome, (e) one of the exposures was CA (occurring prior to 18 years of age), and (f) the mediating or moderating effect of at least one other factor was investigated. A diagnosis of psychotic disorder, schizophrenia, or schizoaffective disorder, based on DSM Criteria, Research Diagnostic Criteria, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9), ICD-10, or psychiatrist or psychologist evaluation was considered eligible. Dimensional measures were defined in terms of individuals in the general population reporting psychotic symptoms, including subclinical psychotic experiences. Studies were excluded if (a) they had a case report or review design, (b) the timing of social adversities was not specified (e.g. the distinction between childhood and adult sexual abuse was not clear), or (c) involved a clinical sample that included organic aetiology of psychosis or substance-induced psychosis, with no separate data provided. Studies conducted on the same sample were included only if they analysed the relationship between CA and different mediators/moderators or their joint effect on different outcomes (e.g. psychotic disorder and PLEs).

Studies were critically appraised using a modified version of the quality assessment tool employed in the Trotta et al. (Reference Trotta, Murray and Fisher2015b) review (see online Supplementary Tables S3–S5). A study was defined as methodologically robust if it achieved a score above 15 for studies assessing the moderating/mediatory effect of genes (maximum score = 21) or above 13 for studies involving only environmental or psychological mediators/moderators (maximum score = 19) corresponding to a 70% cut-off on the quality assessment scale. For papers reporting the findings of different analyses or different studies, separate scores were calculated. Two researchers (LS and AT) independently conducted the quality assessment of each study included (Cohen's k = 0.898, p < 0.001). Any disagreements (e.g. in score attribution for selection bias, results, and confounders) were resolved via a discussion between LS, AT, and HLF.

Results

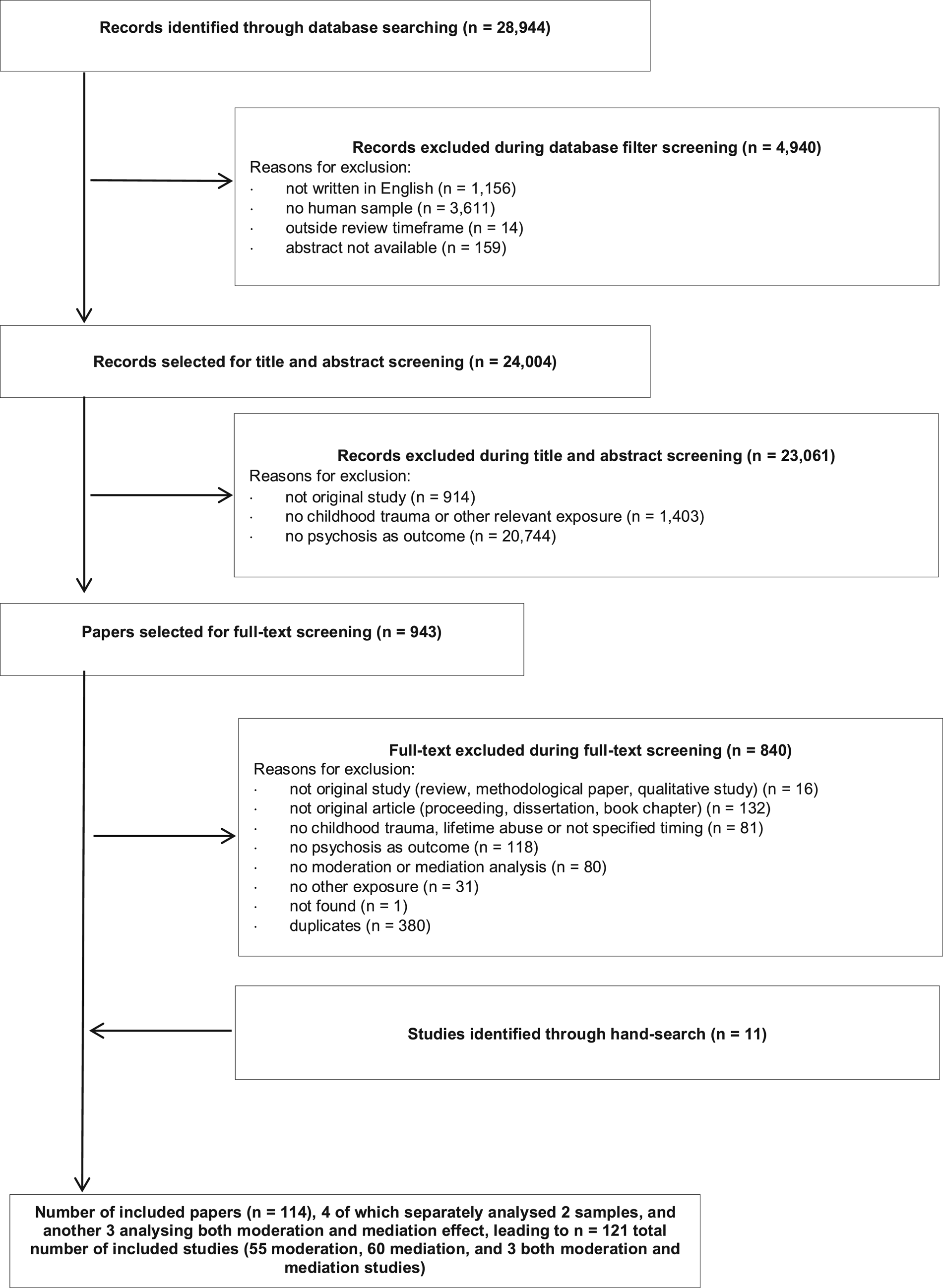

From the 28 944 initial records identified by the search, 24 004 articles were selected for the title and abstract screening, and subsequently 943 articles for full-text screening. A total of 114 papers were included in the review (Fig. 1). These 114 papers utilised data from 85 community and clinical samples and are summarised in online Supplementary Tables S6 and S7 by type of sample and the mediating or moderating factor investigated. Since four papers reported the findings of two different studies, and another three analysed both moderation and mediation effects, the total number of appraised studies was 121. Of these studies, 55 analysed moderation, 60 mediation, and three both moderation and mediation. Several studies investigated the effect of more than one moderator or mediating variable.

Fig. 1. Flow chart of literature screening.

Methodological appraisal

Only 26.4% (32/121) of the studies satisfied our criteria for robustness (scored over 70% on the quality assessment scale; online Supplementary Tables S4 and S5). The most common limitations were related to selection bias, with 57.9% (n = 70) of the studies using unspecified or inadequate selection strategies, and 71.1% (n = 86) reporting low or undefined participation rate, thus limiting generalizability. Although the majority of the studies (78.5%, n = 95) included at least 100 participants and some large epidemiological studies involved more than 1000 (see online Supplementary Tables S6 and S7), the insufficient sample size could have affected the power of the studies and is particularly an issue for interaction studies (Ma, Thabane, Beyene, & Raina, Reference Ma, Thabane, Beyene and Raina2016; van Os, Rutten, & Poulton, Reference van Os, Rutten and Poulton2008). Another main caveat is the quality and heterogeneity of the measurement instruments utilized. Only 11.6% (n = 14) of the studies assessed CA using documented evidence (Debost et al., Reference Debost, Debost, Grove, Mors, Hougaard, Børglum and Petersen2017; Paksarian, Eaton, Mortensen, Merikangas, & Pedersen, Reference Paksarian, Eaton, Mortensen, Merikangas and Pedersen2015; Räikkönen et al., Reference Räikkönen, Lahti, Heinonen, Pesonen, Wahlbeck, Kajantie and Eriksson2011; Walker, Cudeck, Mednick, & Schulsinger, Reference Walker, Cudeck, Mednick and Schulsinger1981; Wicks, Hjern, & Dalman, Reference Wicks, Hjern and Dalman2010) or semi-structured interviews (such as the Childhood Experience of Care and Abuse (CECA) interview; Bifulco, Brown, and Harris, Reference Bifulco, Brown and Harris1994), while the majority relied on self-report instruments (most frequently the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ): Bernstein et al., Reference Bernstein, Fink, Handelsman, Foote, Lovejoy, Wenzel and Ruggiero1994, Reference Bernstein, Stein, Newcomb, Walker, Pogge, Ahluvalia and Zule2003). The latter instruments may be more susceptible to recall bias in clinical populations, although some studies have suggested they are not (Schäfer et al., Reference Schäfer, Morgan, Demjaha, Morgan, Dazzan, Fearon and Fisher2011). Moreover, the quality of information about genetic, environmental, or psychological mediators varied widely across studies, as well as the validity of the outcome measures. In only one-third of the studies (29.8%, n = 36), did the assessment of psychosis involve clinical diagnosis or standardized measures.

Most of the studies, including robust prospective (Lataster, Myin-Germeys, Lieb, Wittchen, & van Os, Reference Lataster, Myin-Germeys, Lieb, Wittchen and van Os2012; Mansueto et al., Reference Mansueto, Schruers, Cosci, van Os, Alizadeh, Bartels-Velthuis and van Winkel2019; Ouellet-Morin et al., Reference Ouellet-Morin, Fisher, York-Smith, Fincham-Campbell, Moffitt and Arseneault2015) and semi-prospective studies (Janssen et al., Reference Janssen, Krabbendam, Hanssen, Bak, Vollebergh, de Graaf and van Os2005; Konings et al., Reference Konings, Stefanis, Kuepper, de Graaf, Have, van Os and Henquet2012; van Nierop et al., Reference van Nierop, van Os, Gunther, van Zelst, de Graaf, ten Have and Van Winkel2014), retrospectively assessed CA with self-report measures, and only a few robust studies used register-based information (Debost et al., Reference Debost, Debost, Grove, Mors, Hougaard, Børglum and Petersen2017; Paksarian et al., Reference Paksarian, Eaton, Mortensen, Merikangas and Pedersen2015; Räikkönen et al., Reference Räikkönen, Lahti, Heinonen, Pesonen, Wahlbeck, Kajantie and Eriksson2011; Walker et al., Reference Walker, Cudeck, Mednick and Schulsinger1981; Wicks et al., Reference Wicks, Hjern and Dalman2010), thus preventing inferences about causality from being drawn. A recent meta-analysis found that prospective and retrospective measures of CA may identify different risk pathways to mental illness (Baldwin, Reuben, Newbury, & Danese, Reference Baldwin, Reuben, Newbury and Danese2019). According to a recent study, retrospective self-report measures may be more strongly associated with mental health problems, compared to prospective reports, particularly in relation to affective symptoms (Newbury et al., Reference Newbury, Arseneault, Moffitt, Caspi, Danese, Baldwin and Fisher2018b). Taking into account the possible effect of affective symptoms on memory bias and the limitation in establishing causality, this study suggested that retrospective measures may be still useful to assess CA in clinical populations.

Of the total, 74% of the studies (n = 90) provided information on the distribution of the main exposures and 93.4% (n = 113) statistically tested the interaction or mediation model. However, robust statistical tests for interaction (e.g. including interaction terms in linear regressions for multiplicative models, Risk Difference and Interaction Contrast Ratios for additive models) and mediation (e.g. Sobel's test or estimate of the direct and indirect effects) were used by only some of the studies. In total, 74% (n = 89) controlled the analysis for potential confounders (though 34.7%, n = 42, only adjusted for basic socio-demographic variables), and only half of the interaction studies (55.2%, 32/58) investigated potential gene-environment or environment–environment correlations, suggesting that alternative explanations might have been overlooked.

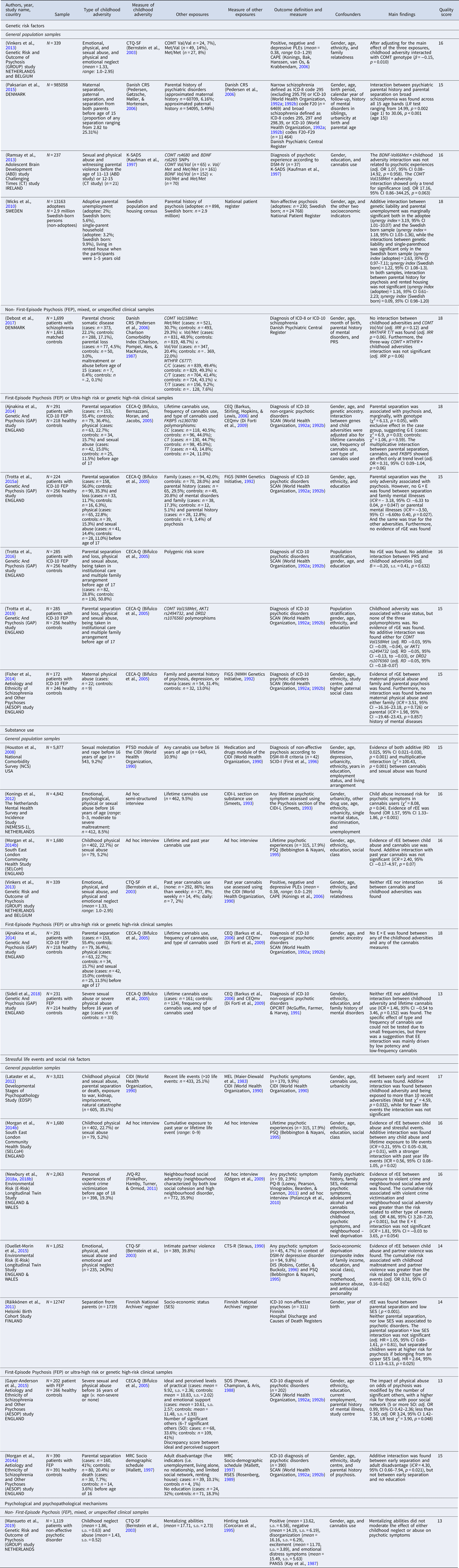

Given the heterogeneity of the designs employed by the studies included in this review, along with the variety of exposures, mediators, moderators and outcomes analysed, it was not possible to conduct a quantitative synthesis of the findings. Therefore, a narrative review of the studies that met our quality assessment threshold is provided below and a summary of the data extracted is presented in Tables 1 and 2. In addition a visual summary of both robust and less robust studies is provided in Figs 2 and 3.

Fig. 2. Findings from robust and less robust moderation/interaction studies. The figure shows the percentage of significant (p < 0.05) and non-significant interaction studies reported by more robust and less robust studies, by type of risk factor. GWAS, genome-wide association study. PRS, polygenic risk score.

Fig. 3. Findings from robust and less robust mediation studies. The figure shows the percentage of significant (p < 0.05) and non-significant mediation studies reported by more robust and less robust studies, by type of risk factor. PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Table 1. Summary of the findings of methodologically robust interaction and moderation studies by type of exposure and population

Adj, adjusted; AVH, Auditory Verbal Hallucinations; BDNF, Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor; CI, confidence interval; COMT, Catechol O-methyltransferase; DIS, Diagnostic Interview Schedule; EPP, Extended Psychosis Phenotype; DRD, Dopamine Receptor D; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of mental disorders; E × E, Environment × Environment interaction; FEP, First Episode of Psychosis; FKBP5, Binding protein 5; G × E, Gene × Environment interaction; ICD, International Classification of Disease; ICR, Interaction Contrast Ratio; IQ, Intellectual Quotient; JVQ, Juvenile Victimization Questionnaire; LR, Likelihood Ratio; MRC, Medical Research Council; MTHFR, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase; OR, odds ratio; PD, Psychotic Disorder; PLEs, Psychotic-Like Experiences; PRS, polygenic risk score; PTSD, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder; RD, Risk Difference; rEE, Environment–Environment correlation; rGE, Gene–Environment correlation; s.d., Standard Deviation; s.e., Standard Error; SES, Socio-economic status.

AAQ, Adult Attachment Questionnaire; ASI, Attachment Style Interview; BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; CAARMS, Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States; CAPE, Community Assessment of Psychic Experiences; CAPPS, Current and Past Psychopathology Scale; CECA, Childhood Experience of Care and Abuse; CECA-Q, Childhood Experience of Care and Abuse Questionnaire; CEQ, Cannabis Experiences Questionnaire; CEQmv, Cannabis Experiences Questionnaire modified version; CIDI, Composite International Diagnostic Interview; CIS-R, Clinical Interview Schedule – Revised; CRS, Danish Civil Registration System; CTQ, Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; CTQ-SF, Childhood Trauma Questionnaire – short form; CTS-R, Conflict Tactics Scale-Form R; FIGS, Family Interview for Genetic Studies; K-SADS, Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children; MEL, Munich Interview for the Assessment of Life Events and Conditions; OPCRIT, Operational Criteria System; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; PBI, Parental Bonding Instrument; PSE, Present State Examination; PQ-B Prodromal Questionnaire – Brief version; PSQ, Psychosis Screening Questionnaire; RSES, Rosenberg self-esteem scale; SCAN, Schedule for Assessment in Neuropsychiatry; SCID-I, Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM Axis I disorder; SOS, Significant Others Scale; UM-CIDI, University of Michigan Composite International Diagnostic Interview.

Note: when not reported in the paper, frequencies were calculated from percentages. References of measurement instruments are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

Table 2. Summary of the findings of methodologically robust mediation studies by type of exposure and population

Adj, adjusted; AVH, Auditory Verbal Hallucinations; BDNF, Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor; CI, confidence interval; COMT, Catechol O-methyltransferase; DIS, Diagnostic Interview Schedule; EPP, Extended Psychosis Phenotype; DRD, Dopamine Receptor D; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of mental disorders; E × E, Environment × Environment interaction; FEP, First Episode of Psychosis; FKBP5, Binding protein 5; G × E, Gene × Environment interaction; ICD, International Classification of Disease; ICR, Interaction Contrast Ratio; IQ, Intellectual Quotient; JVQ, Juvenile Victimization Questionnaire; LR, Likelihood Ratio; MRC, Medical Research Council; MTHFR, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase; OR, odds ratio; PD, Psychotic Disorder; PLEs, Psychotic-Like Experiences; PRS, polygenic risk score; PTSD, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder; RD, Risk Difference; rEE, Environment–Environment correlation; rGE, Gene–Environment correlation; s.d., Standard Deviation; s.e., Standard Error; SES, Socio-economic status.

AAQ, Adult Attachment Questionnaire; ASI, Attachment Style Interview; BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; CAARMS, Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States; CAPE, Community Assessment of Psychic Experiences; CAPPS, Current and Past Psychopathology Scale; CECA, Childhood Experience of Care and Abuse; CECA-Q, Childhood Experience of Care and Abuse Questionnaire; CEQ, Cannabis Experiences Questionnaire; CEQmv, Cannabis Experiences Questionnaire modified version; CIDI, Composite International Diagnostic Interview; CIS-R, Clinical Interview Schedule – Revised; CRS, Danish Civil Registration System; CTQ, Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; CTQ-SF, Childhood Trauma Questionnaire – short form; CTS-R, Conflict Tactics Scale-Form R; FIGS, Family Interview for Genetic Studies; K-SADS, Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children; MEL, Munich Interview for the Assessment of Life Events and Conditions; OPCRIT, Operational Criteria System; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; PBI, Parental Bonding Instrument; PSE, Present State Examination; PQ-B, Prodromal Questionnaire – Brief version; PSQ, Psychosis Screening Questionnaire; RSES, Rosenberg self-esteem scale; SCAN, Schedule for Assessment in Neuropsychiatry; SCID-I, Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM Axis I disorder; SOS, Significant Others Scale; UM-CIDI, University of Michigan Composite International Diagnostic Interview.

Note: when not reported in the paper, frequencies were calculated from percentages. References of measurement instruments are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

Interaction studies

Genetic risk factors

The role of genetic factors in the association between CA and psychotic disorders has been investigated in terms of gene–environment correlation (rGE), that is genes influencing exposure to CA, and gene–environment interaction (G × E), that is genes influencing sensitivity to the effects of CA once exposed, using quantitative (e.g. affected relatives) or molecular (e.g. specific polymorphisms) genetic measures (Table 1). A total of 34 studies investigated such associations and 10 (29.4%) were considered methodologically robust (see online Supplementary Table S6). Two robust population-based cohort studies showed that parental history of psychosis interacted significantly with parental separation (Paksarian et al., Reference Paksarian, Eaton, Mortensen, Merikangas and Pedersen2015) and parental unemployment (Wicks et al., Reference Wicks, Hjern and Dalman2010) in increasing the risk of non-affective psychosis. Two studies on FEP samples found no evidence of gene–environment interaction between CA and familial risk for mental health problems (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, McGuffin, Boydell, Fearon, Craig, Dazzan and Morgan2014; Trotta et al., Reference Trotta, Di Forti, Lyegbe, Green, Dazzan, Mondelli and Fisher2015a), one of which reported a significant association between high genetic risk for psychosis and self-reported severe physical abuse from mother (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, McGuffin, Boydell, Fearon, Craig, Dazzan and Morgan2014), indicating the potential presence of a passive rGE.

Interactions between potential molecular genetic susceptibility and exposure to CA in predicting the development of psychotic symptoms have mainly focused on candidate genes. COMT Val158Met × CA interaction has been associated with psychotic experiences in a non-FEP prospective study (Vinkers et al., Reference Vinkers, Van Gastel, Schubart, Van Eijk, Luykx, Van Winkel and Boks2013). However, such G × E was not replicated by other studies (Debost et al., Reference Debost, Debost, Grove, Mors, Hougaard, Børglum and Petersen2017; Ramsay et al., Reference Ramsay, Kelleher, Flannery, Clarke, Lynch, Harley and Cannon2013; Trotta et al., Reference Trotta, Iyegbe, Yiend, Dazzan, David, Pariante and Fisher2019), and no relationship was found with FKBP5 (Ajnakina et al., Reference Ajnakina, Borges, Di Forti, Patel, Xu, Green and Iyegbe2014), BDNF (Ramsay et al., Reference Ramsay, Kelleher, Flannery, Clarke, Lynch, Harley and Cannon2013), MTHFR C677T (Debost et al., Reference Debost, Debost, Grove, Mors, Hougaard, Børglum and Petersen2017), DRD2 or AKT1 risk haplotypes (Trotta et al., Reference Trotta, Iyegbe, Yiend, Dazzan, David, Pariante and Fisher2019). Only one study used genome-wide association and polygenic risk score methods in FEP, with negative findings (Trotta et al., Reference Trotta, Iyegbe, Di Forti, Sham, Campbell, Cherny and Fisher2016). The less robust studies overall replicated the inconsistent findings regarding the moderating effect of genetic vulnerability, and the sparse findings regarding specific genetic susceptibilities, with the more consistent results for FKBP5, BDNF, and a suggestion of a three-way interaction between COMT Val158Met, CA, and cannabis use in individuals carrying the Val/Val genotype, which showed an effect on positive (e.g. delusions and hallucinations) and negative (including reduced social drive and volition, blunted emotions, lack of energy, poverty of speech and thoughts) psychotic experiences (see Fig. 2 and online Supplementary Table S6).

Substance use

Out of 12 studies on substance abuse, six were methodologically robust (see online Supplementary Table S6) and all of them explored the relationship with cannabis use. Additive and multiplicative interactions were found in large epidemiological surveys (Houston, Murphy, Adamson, Stringer, & Shevlin, Reference Houston, Murphy, Adamson, Stringer and Shevlin2008; Konings et al., Reference Konings, Stefanis, Kuepper, de Graaf, Have, van Os and Henquet2012), but not replicated in other population and case-control studies (Ajnakina et al., Reference Ajnakina, Borges, Di Forti, Patel, Xu, Green and Iyegbe2014; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Reininghaus, Reichenberg, Frissa, Hotopf and Hatch2014b; Sideli et al., Reference Sideli, Fisher, Murray, Sallis, Russo, Stilo and Di Forti2018; Vinkers et al., Reference Vinkers, Van Gastel, Schubart, Van Eijk, Luykx, Van Winkel and Boks2013). Several of these studies (Konings et al., Reference Konings, Stefanis, Kuepper, de Graaf, Have, van Os and Henquet2012; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Reininghaus, Reichenberg, Frissa, Hotopf and Hatch2014b) claimed that the CA × cannabis interaction may be confounded by environment–environment correlation (rEE), but other studies (Sideli et al., Reference Sideli, Fisher, Murray, Sallis, Russo, Stilo and Di Forti2018; Vinkers et al., Reference Vinkers, Van Gastel, Schubart, Van Eijk, Luykx, Van Winkel and Boks2013) did not confirm this finding. However, the CA–cannabis interaction was also reported by the majority of the less robust studies (see Fig. 2 and online Supplementary Table S6).

Social, psychological and psychopathological mechanisms

Seven out of thirteen studies assessing social risk factors were rated as methodologically robust (see online Supplementary Table S6). Two population-based studies reported an additive interaction between CA and life events, particularly when numerous and occurring in the previous 12 months (Lataster et al., Reference Lataster, Myin-Germeys, Lieb, Wittchen and van Os2012; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Reininghaus, Reichenberg, Frissa, Hotopf and Hatch2014b). In a prospective cohort study, the experience of both CA and intimate partner violence was related to a more than double risk for psychotic symptoms in major depressive disorder, compared to the exposure to either type of event (Ouellet-Morin et al., Reference Ouellet-Morin, Fisher, York-Smith, Fincham-Campbell, Moffitt and Arseneault2015). The moderating role of life events was partly confirmed by around half of the less robust studies (see Fig. 2 and online Supplementary Table S6). In a case-control study, the effect of physical abuse on FEP was significantly reduced by the presence of close others (Gayer-Anderson et al., Reference Gayer-Anderson, Fisher, Fearon, Hutchinson, Morgan, Dazzan and Morgan2015), suggesting a protective role of social support against the psychotogenic effects of CA. Less consistent were the findings on the role of adult disadvantage: while in a case-control study, adult disadvantage interacted with parental separation in the risk for psychosis (Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Reininghaus, Fearon, Hutchinson, Morgan, Dazzan and Craig2014a), in a birth cohort no synergism was found (Räikkönen et al., Reference Räikkönen, Lahti, Heinonen, Pesonen, Wahlbeck, Kajantie and Eriksson2011), and a single less robust study reported negative findings. Among the two studies investigating the role of broader social factors, a robust cohort study found that the interaction between CA and neighbourhood social adversity only approached significance (Newbury et al., Reference Newbury, Arseneault, Caspi, Moffitt, Odgers and Fisher2018a). Of the three studies on psychological mechanisms, only one satisfied criterion for robustness (Mansueto et al., Reference Mansueto, Schruers, Cosci, van Os, Alizadeh, Bartels-Velthuis and van Winkel2019), which reported no evidence of moderation by mentalizing abilities.

Mediation studies

Genetic risk factors, substance use, stressful events, and social risk factors

Neither of the two studies on genetic risk factors was methodologically robust and both reported negative findings. The only robust study (out of five) analysing the mediating role of cannabis use on the relationship between CA and psychotic symptoms led to negative results (van Nierop et al., Reference van Nierop, van Os, Gunther, van Zelst, de Graaf, ten Have and Van Winkel2014) and a single less robust study suggested a partial mediating effect of substance abuse. Life events were found to partially mediate the CA-psychosis association (47% of the total effect), with a greater mediation effect for violent (v. non-violent) life events (Bhavsar et al., Reference Bhavsar, Boydell, McGuire, Harris, Hotopf, Hatch and Morgan2019) but the findings have not been replicated by less robust studies. A single mediation study on adult disadvantage found that it mediated the effect of parental separation on psychosis, accounting for 75% of the total effect (Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Reininghaus, Fearon, Hutchinson, Morgan, Dazzan and Craig2014a). In two large population studies, evidence for a mediatory pathway between CA and psychosis was found for social defeat (van Nierop et al., Reference van Nierop, van Os, Gunther, van Zelst, de Graaf, ten Have and Van Winkel2014) and for loneliness (Shevlin, McElroy, & Murphy, Reference Shevlin, McElroy and Murphy2015), and the results were also consistent in less robust studies (see Fig. 3 and online Supplementary Table S7).

Psychological and psychopathological mechanisms

A total of 56 studies focused on psychological mechanisms, and eight (14.3%) were methodologically robust (see online Supplementary Table S7). The most consistent evidence concerned the mediating role of attachment and non-psychotic symptoms. Two prospective studies pointed to the potential mediating role of parental bonding and institutional care (Janssen et al., Reference Janssen, Krabbendam, Hanssen, Bak, Vollebergh, de Graaf and van Os2005; Walker et al., Reference Walker, Cudeck, Mednick and Schulsinger1981). With regards to the role of specific types of attachment insecurity, the NCS study highlighted specific pathways linking different types of CA to psychotic symptoms, via avoidant and anxious attachment (Sitko, Bentall, Shevlin, O'Sullivan, & Sellwood, Reference Sitko, Bentall, Shevlin, O'Sullivan and Sellwood2014), and a Spanish study suggested that angry/dismissive attachment specifically mediated the effect of parental antipathy on PLEs (Sheinbaum et al., Reference Sheinbaum, Bifulco, Ballespí, Mitjavila, Kwapil and Barrantes-Vidal2015). The mediating role of insecure attachment was confirmed by five out of six less robust studies (see Fig. 3 and online Supplementary Table S7).

PTSD and anxiety symptoms, but not depression, partially mediated the effect of sexual abuse on auditory verbal hallucinations (McCarthy-Jones, Reference McCarthy-Jones2018). Moreover, the totality of less robust studies (n = 22) reported mediation via dissociation and/or PTSD symptoms. In another study, mood instability lay on the pathway connecting CA to social defeat to PLEs (van Nierop et al., Reference van Nierop, van Os, Gunther, van Zelst, de Graaf, ten Have and Van Winkel2014). A single robust study reported that depression decreased the mediating effect of attachment insecurity on the relationship between CA and psychosis (Sitko et al., Reference Sitko, Bentall, Shevlin, O'Sullivan and Sellwood2014). The mediating role of depression, mood instability, and other affective symptoms was further confirmed by most of the less robust studies (12 out of 16). Only one robust study investigated the role of self-esteem with negative results (Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Reininghaus, Fearon, Hutchinson, Morgan, Dazzan and Craig2014a). According to a single robust study, mentalization abilities partially mediated the effect of childhood neglect on negative and affective symptoms of psychosis (Mansueto et al., Reference Mansueto, Schruers, Cosci, van Os, Alizadeh, Bartels-Velthuis and van Winkel2019). However, a number of less robust studies (15 out of 17) suggested mediation via mentalization or metacognitive abilities, core beliefs about the self and others, and other cognitive processes (see Fig. 3 and online Supplementary Table S7).

Discussion

This systematic review included 121 studies exploring potential genetic, social, psychological, and psychopathological mediating and moderating factors of the relationship between CA and psychosis (from subclinical psychotic experiences through to clinically diagnosed psychotic disorders). To maximize the comprehensiveness of the review, the search was not limited to mediation studies (Williams, Bucci, Berry, & Varese, Reference Williams, Bucci, Berry and Varese2018) but also included interaction studies. However, only a quarter of the studies satisfied our criteria for methodological robustness. Moreover, due to the large degree of heterogeneity across the studies included and the small number of studies available for each mediating/moderating factor, it was not possible to conduct a quantitative synthesis of the findings. Indeed, caution has been urged when attempting to apply meta-analytical methods to only a few heterogeneous studies, as it can result in biased effect estimates and too narrow or too broad confidence intervals (Debray, Moons, & Riley, Reference Debray, Moons and Riley2018; Guolo & Varin, Reference Guolo and Varin2017). In order to limit the effect of publication bias, the narrative synthesis was mainly focused on methodologically robust studies. However, Figs 2 and 3, which show the percentage of studies with statistically significant findings among the robust and less robust studies, suggest that findings were largely consistent across studies, regardless of their methodological quality. Furthermore, a visual inspection of the robust interaction studies suggests that studies with negative findings were well represented (online Supplementary Table S8), suggesting a limited effect of reporting bias. Although robust mediation studies led, with few exceptions, to significant results, these mostly came from large population-based studies (online Supplementary Table S9), suggesting that evidence of the mediatory role of social and psychological factors is unlikely to be based on smaller studies. Nevertheless, in this review a statistical estimate of publication bias could not be calculated due to the heterogeneity of the studies.

Overall, non-FEP studies were scarcely represented among the robust studies. The majority of the statistically significant findings regarding moderation and, especially, mediation effects came from the general population and, to a lesser extent, FEP/UHR studies focusing on psychotic symptoms and PLEs. This may be related to the phenotypic expression of psychosis according to a continuum model of psychosis (van Os et al., Reference van Os, Linscott, Myin-Germeys, Delespaul and Krabbendam2009), the greater prevalence of PLEs compared to psychotic disorders (Linscott & van Os, Reference Linscott and van Os2013), and/or the greater statistical power of studies using continuous rather than dichotomous outcomes. The latter also suggests that evidence of moderation/mediation between CA and other risk factors may have been underestimated among studies using disorder-level outcomes.

Summary of findings

The existing biological findings from the more robust studies suggest that the effect of CA in increasing the risk for psychosis might be partially independent of pre-existing genetic liability. Interaction between CA and family history for psychosis as well as specific polymorphisms led to inconsistent findings, and the few positive results were related to genes, such as COMT, whose role in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia was not confirmed by a recent meta-analysis (Ripke et al., Reference Ripke, Neale, Corvin, Walters, Farh, Holmans and O'Donovan2014). On the other hand, genes involved in dopaminergic and glutamatergic transmission, as well as in immunity function (e.g. FKBP5), whose role in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia has been increasingly recognised (Ripke et al., Reference Ripke, Neale, Corvin, Walters, Farh, Holmans and O'Donovan2014), were less explored by current interaction studies and should be further investigated in relation to CA by methodologically robust studies. However, the findings should be interpreted in light of the fact that G × E studies had fairly limited sample sizes which may have reduced the likelihood of detecting significant interaction effects. In addition, previous studies suggested that investigating the gene–CA interaction in psychosis would be benefitted by using overall measures of genetic risk derived from GWAS studies, replication across different populations, and statistical models accounting for multiple testing and the confounding effect of rGE (Morgan & Gayer-Anderson, Reference Morgan and Gayer-Anderson2016; van Winkel, Stefanis, & Myin-Germeys, Reference van Winkel, Stefanis and Myin-Germeys2008). Further, well-powered research addressing these issues is still required.

Consistent with a previous review (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Bucci, Berry and Varese2018), there were contradictory findings regarding the moderating effect of cannabis use, both in robust and less robust studies, and only a negative mediation study, while no robust studies on other substances were found. Evidence of interaction was found in only a few large epidemiological surveys (Houston et al., Reference Houston, Murphy, Adamson, Stringer and Shevlin2008; Konings et al., Reference Konings, Stefanis, Kuepper, de Graaf, Have, van Os and Henquet2012), suggesting that lack of interaction may be influenced by insufficient statistical power. An alternative explanation may be that all these studies defined cannabis use in terms of using at least once over the life-course (Ajnakina et al., Reference Ajnakina, Borges, Di Forti, Patel, Xu, Green and Iyegbe2014; Houston et al., Reference Houston, Murphy, Adamson, Stringer and Shevlin2008; Konings et al., Reference Konings, Stefanis, Kuepper, de Graaf, Have, van Os and Henquet2012; Morgan et al., Reference Konings, Stefanis, Kuepper, de Graaf, Have, van Os and Henquet2014b; Sideli et al., Reference Sideli, Fisher, Murray, Sallis, Russo, Stilo and Di Forti2018), while it is possible that the impact of cannabis exposure may substantially vary depending upon the quantity, type, and age of first use.

The evidence presented in this review supports a role for social risk factors in the pathway between CA and psychosis, particularly the interaction with (Lataster et al., Reference Lataster, Myin-Germeys, Lieb, Wittchen and van Os2012; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Reininghaus, Fearon, Hutchinson, Morgan, Dazzan and Craig2014a; Ouellet-Morin et al., Reference Ouellet-Morin, Fisher, York-Smith, Fincham-Campbell, Moffitt and Arseneault2015) and mediation by (Bhavsar et al., Reference Bhavsar, Boydell, McGuire, Harris, Hotopf, Hatch and Morgan2019) life events. The effect of social support also seemed to be consistent across studies: while having close others reduced the impact of CA on FEP (Gayer-Anderson et al., Reference Gayer-Anderson, Fisher, Fearon, Hutchinson, Morgan, Dazzan and Morgan2015), loneliness and social defeat mediated the effect on PLEs (van Nierop et al., Reference van Nierop, van Os, Gunther, van Zelst, de Graaf, ten Have and Van Winkel2014) and psychosis (Shevlin et al., Reference Shevlin, McElroy and Murphy2015), a finding also replicated in less robust studies.

According to a few methodologically robust studies examining the role of attachment styles and parental bonding, insecure attachment and institutional care, these factors partially mediated the effect of CA on schizotypal traits (Walker et al., Reference Walker, Cudeck, Mednick and Schulsinger1981), PLEs (Sheinbaum et al., Reference Sheinbaum, Bifulco, Ballespí, Mitjavila, Kwapil and Barrantes-Vidal2015), and psychotic symptoms (Janssen et al., Reference Janssen, Krabbendam, Hanssen, Bak, Vollebergh, de Graaf and van Os2005; Sitko et al., Reference Sitko, Bentall, Shevlin, O'Sullivan and Sellwood2014). Furthermore, a few robust studies supported a contribution of mood, anxiety, and PTSD symptoms to the pathway between CA and psychosis (McCarthy-Jones, Reference McCarthy-Jones2018; van Nierop et al., Reference van Nierop, van Os, Gunther, van Zelst, de Graaf, ten Have and Van Winkel2014) but most of the evidence on the mediating role of mood and anxiety symptoms, as well as PTSD and dissociation, came from a number of less robust studies which had potential limitations in terms of selection bias, crude measurement instruments, and (lack of) adjustment for confounders. This suggests that the size of the mediation or moderation effect might not have been accurately estimated and that alternative explanations might be possible. Only two robust studies explored the role of cognitive mediators (Mansueto et al., Reference Mansueto, Schruers, Cosci, van Os, Alizadeh, Bartels-Velthuis and van Winkel2019; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Reininghaus, Fearon, Hutchinson, Morgan, Dazzan and Craig2014a), among which a single study found evidence of partial mediation of the CA-psychosis association via mentalization (Mansueto et al., Reference Mansueto, Schruers, Cosci, van Os, Alizadeh, Bartels-Velthuis and van Winkel2019).

Pathway specificity

Taken together, the findings regarding the interaction between early and recent adversities and the mediating role of post-traumatic and mood symptoms support the model of the affective pathway to psychosis (Myin-Germeys & van Os, Reference Myin-Germeys and van Os2007). Cumulative adversity can detrimentally affect emotion regulation processes, through which individuals modulate their emotions to respond to environmental demands (Bargh & Williams, Reference Bargh, Williams and Gross2007; Rottenberg & Gross, Reference Rottenberg and Gross2003), and thus may represent a mechanism linking repeated exposure to adversity to development of psychosis. Furthermore, early trauma can shape how we interpret interpersonal contexts throughout the lifespan and is associated with the development of attachment insecurity, including worry about relationships, difficulty in trusting others, and social withdrawal (Berry, Barrowclough, & Wearden, Reference Berry, Barrowclough and Wearden2007). Research suggests this might represent another mechanism through which psychosis develops and is maintained (Bentall et al., Reference Bentall, De Sousa, Varese, Wickham, Sitko, Haarmans and Read2014; Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Dunn, Fowler, Bebbington, Kuipers, Emsley and Garety2013; Sitko, Varese, Sellwood, Hammond, & Bentall, Reference Sitko, Varese, Sellwood, Hammond and Bentall2016).

Cumulative adversity can also ‘get under the skin,’ through stress-sensitization of the dopamine system and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis dysregulation (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Eyre, Jacka, Dodd, Dean, McEwen and Berk2016; Misiak et al., Reference Misiak, Krefft, Bielawski, Moustafa, Sąsiadek and Frydecka2017; Ruby et al., Reference Ruby, Polito, McMahon, Gorovitz, Corcoran and Malaspina2014), possibly via epigenetic mechanisms (Tomassi & Tosato, Reference Tomassi and Tosato2017). Previous reviews suggested that this pathway may be particularly relevant for positive symptoms, and relatively independent of neurodevelopmental delays and cognitive impairment, which in turn seem more related to negative symptoms (Howes & Murray, Reference Howes and Murray2014; Myin-Germeys & van Os, Reference Myin-Germeys and van Os2007). However, this postulated model needs to be further explored since only a single robust study found evidence of an effect on positive but not negative psychotic symptoms (Sheinbaum et al., Reference Sheinbaum, Bifulco, Ballespí, Mitjavila, Kwapil and Barrantes-Vidal2015).

Some studies examined the relationship between particular types of CA and specific moderators or mediators, but only a few led to evidence of an effect. Physical abuse was found to interact with social support in FEP (Gayer-Anderson et al., Reference Gayer-Anderson, Fisher, Fearon, Hutchinson, Morgan, Dazzan and Morgan2015). The effect of sexual abuse on psychotic symptoms was partially mediated by PTSD, compulsions (McCarthy-Jones, Reference McCarthy-Jones2018), as well as attachment anxiety (Sitko et al., Reference Sitko, Bentall, Shevlin, O'Sullivan and Sellwood2014). The effect of neglect on paranoia was found to be mediated by attachment insecurity (Sitko et al., Reference Sitko, Bentall, Shevlin, O'Sullivan and Sellwood2014), whereas the association with negative symptoms was mediated by metacognitive abilities (Mansueto et al., Reference Mansueto, Schruers, Cosci, van Os, Alizadeh, Bartels-Velthuis and van Winkel2019). Although preliminary and less robust studies further confirmed the pathways from sexual abuse via PTSD and dissociation (Bortolon, Seillé, & Raffard, Reference Bortolon, Seillé and Raffard2017; Hardy et al., Reference Hardy, Emsley, Freeman, Bebbington, Garety, Kuipers and Fowler2016; see online Supplementary Materials) and from neglect via attachment insecurity and cognition (Gawęda, Göritz, & Moritz, Reference Gawęda, Göritz and Moritz2019; Pilton et al., Reference Pilton, Bucci, McManus, Hayward, Emsley and Berry2016; see online Supplementary Materials), such a small number of methodologically robust studies does not yet allow for drawing firm conclusions on any specific mediating or moderating pathways.

Compared to the majority of the studies defining CA in terms of parental abuse and/or neglect, only a few of the reviewed studies explored the specific effect of parental separation/death or adoption (Ajnakina et al., Reference Ajnakina, Borges, Di Forti, Patel, Xu, Green and Iyegbe2014; Boyda & McFeeters, Reference Boyda and McFeeters2015; Ierago et al., Reference Ierago, Malsol, Singeo, Kishigawa, Blailes, Ord and Ngiralmau2010; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Reininghaus, Fearon, Hutchinson, Morgan, Dazzan and Craig2014a; Paksarian et al., Reference Paksarian, Eaton, Mortensen, Merikangas and Pedersen2015; Räikkönen et al., Reference Räikkönen, Lahti, Heinonen, Pesonen, Wahlbeck, Kajantie and Eriksson2011; Trotta et al., Reference Trotta, Di Forti, Lyegbe, Green, Dazzan, Mondelli and Fisher2015a; Walker et al., Reference Walker, Cudeck, Mednick and Schulsinger1981) and more subtle forms of parental difficulties, such as parental antipathy, rejection, emotional invalidation (Akün, Durak Batigün, Devrimci Özgüven, & Baskak, Reference Akün, Durak Batigün, Devrimci Özgüven and Baskak2018; Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Schreier, Zammit, Maughan, Munafò, Lewis and Wolke2013; Sheinbaum et al., Reference Sheinbaum, Bifulco, Ballespí, Mitjavila, Kwapil and Barrantes-Vidal2015; Udachina & Bentall, Reference Udachina and Bentall2014), and vulnerable parental status (Wicks et al., Reference Wicks, Hjern and Dalman2010). It is possible that this area was not extensively covered by the search strategy or that studies on these adversities were, in fact, less common. The methodologically robust studies included in this review suggested a possible synergism with social disadvantage and potentially an indirect effect on psychosis via attachment and parental bonding. Less robust studies indicated a further potential mediatory pathway via beliefs about others and the world.

Consistency of findings across community and clinical samples

The more consistent findings on the moderating/mediating effect of adult adversities both on PLEs (Bhavsar et al., Reference Bhavsar, Boydell, McGuire, Harris, Hotopf, Hatch and Morgan2019) and psychotic symptoms (Lataster et al., Reference Lataster, Myin-Germeys, Lieb, Wittchen and van Os2012; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Reininghaus, Fearon, Hutchinson, Morgan, Dazzan and Craig2014a; Ouellet-Morin et al., Reference Ouellet-Morin, Fisher, York-Smith, Fincham-Campbell, Moffitt and Arseneault2015) were consistently replicated in robust population-based studies. Similarly, the mediatory role of loneliness/social defeat was ascertained both at symptom- (van Nierop et al., Reference van Nierop, van Os, Gunther, van Zelst, de Graaf, ten Have and Van Winkel2014) and disorder-level both in the population (Shevlin et al., Reference Shevlin, McElroy and Murphy2015) and clinical FEP samples (Gayer-Anderson et al., Reference Gayer-Anderson, Fisher, Fearon, Hutchinson, Morgan, Dazzan and Morgan2015). Among psychological mediators, the mediating role of parental bonding and attachment insecurity was consistently observed on PLEs (Sheinbaum et al., Reference Sheinbaum, Bifulco, Ballespí, Mitjavila, Kwapil and Barrantes-Vidal2015) and symptoms (Janssen et al., Reference Janssen, Krabbendam, Hanssen, Bak, Vollebergh, de Graaf and van Os2005; Sitko et al., Reference Sitko, Bentall, Shevlin, O'Sullivan and Sellwood2014) in population-based studies, as well as in a high-risk for psychosis sample (Walker et al., Reference Walker, Cudeck, Mednick and Schulsinger1981). Taken together, the findings suggest that large population studies provided more consistent findings for possible pathways (i.e. adult adversities and parental bonding) from CA to psychosis, both at the symptom and disorder levels.

Directions for future research and clinical implications

The present work suggests that recent life events, the experience of loneliness and social defeat, attachment and parental bonding, and, to a lesser extent, mood and PTSD symptoms mediate and/or moderate the impact that CA has on psychotic symptoms across the lifespan. However, most studies were affected by a number of limitations that reduce the potential impact of the findings. Inadequate sampling strategies and lack of information on participation rate may have affected the generalizability of the findings as well as the sensitivity to selection bias. Furthermore, retrospective assessment of CA and mediatory variables may have increased the possibility of recall bias. Moreover, the differential effect of childhood v. adolescent exposure to adversity on psychosis in relation to specific mediators and moderators was not investigated by the studies included in this review and warrants exploration. Small sample sizes are likely to be associated with lack of power and risk for type II errors. Moreover, evidence suggests that additive interaction may be more effective than multiplicative interaction in capturing the effect of those exposures – such as CA, substance misuse, or genetic risk factors – that may act either independently or synergistically on the same outcome (van Os et al., Reference van Os, Rutten and Poulton2008; van Winkel et al., Reference van Winkel, Van Nierop, Myin-Germeys and van Os2013) and few studies adopted this approach. In mediation studies, the lack of longitudinal prospective studies and in some cases the likely co-occurrence between CA and possible mediators, which may have also occurred in childhood (Janssen et al., Reference Janssen, Krabbendam, Hanssen, Bak, Vollebergh, de Graaf and van Os2005; Räikkönen et al., Reference Räikkönen, Lahti, Heinonen, Pesonen, Wahlbeck, Kajantie and Eriksson2011; Walker et al., Reference Walker, Cudeck, Mednick and Schulsinger1981), makes it difficult to establish a temporal order between the exposure and the mediator. In both types of studies, robust statistical methods for testing interaction and mediation models are warranted, as well as adjustment for other genetic, social, and psychological risk factors.

We suggest that future research should focus more on prospective cohort studies, including samples at different points along the psychosis spectrum, and employing consistent and validated measures of multiple exposures and outcomes to more robustly study these potential mechanisms. The benefits of conducting methodologically robust studies are multiple: (a) they allow researchers to unravel causal links between the mediators/moderators of the well-established CA-psychosis association; (b) inform public health policies; and (c) facilitate the development of tailored preventative and therapeutic interventions to reduce the ‘toxic’ effect of CA throughout development at an individual and societal level (Shonkoff et al., Reference Shonkoff, Garner, Siegel, Dobbins, Earls, McGuinn and Wegner2012).

Psychological mediating and moderating factors in relation to the CA-psychosis association include anxiety, depression, and emotion dysregulation, in a context of relational insecurity, perceived discrimination, and lack of social support. These factors might be linked with the way individuals with CA and psychotic symptoms process internal and external information (Garety, Kuipers, Fowler, Freeman, & Bebbington, Reference Garety, Kuipers, Fowler, Freeman and Bebbington2001). A recent meta-analysis reported that a few studies have focused on interventions for people with psychotic symptoms and developmental trauma, with initial but limited evidence for mindfulness-based acceptance and commitment therapy, skills training in affective and interpersonal regulation, psychodynamic psychotherapy and systemic approaches (Bloomfield et al., Reference Bloomfield, Yusuf, Srinivasan, Kelleher, Bell and Pitman2020). If the findings of this review are replicated in more robust studies, then it would be important for individual and family interventions to focus on such potential treatment targets, including emotion regulation, acceptance, interpersonal skills, trauma re-processing, and the integration of dissociated ego states (Brent, Reference Brent2009; Louise, Fitzpatrick, Strauss, Rossell, & Thomans, Reference Louise, Fitzpatrick, Strauss, Rossell and Thomans2018). Such treatment targets would also be crucial for preventive interventions for high-risk children and adolescents who were exposed to CA (Gillies et al., Reference Gillies, Maiocchi, Bhandari, Taylor, Gray and O'Brien2016; Macdonald et al., Reference Macdonald, Higgins, Ramchandani, Valentine, Bronger, Klein and Taylor2012; Mavranezouli et al., Reference Mavranezouli, Megnin-Viggars, Daly, Dias, Stockton, Meiser-Stedman and Pilling2020).

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720002172.

Acknowledgements

AT is supported by the UK National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre Early Career Bridging Grant. HLF was supported by an MQ Fellows Award (MQ14F40) and a British Academy Mid-Career Fellowship (MD\170005).

Conflicts of interest

None.