Many readers will know the line, often attributed to George Bernard Shaw, that opera is what happens when ‘a tenor and soprano want to make love but are prevented from doing so by a baritone’.Footnote 1 The quip underscores the obvious: it would be hard to imagine producing or interpreting an opera without recourse to the concept of voice type (categories such as tenor, soprano and the like). Opera scholars understand this perfectly well, of course. Catherine Clément reiterated Shaw's point, if on a darker note, observing that archetypal voices and character types such as the tenor hero or the soprano victim are indeed foundational elements of opera's expressive ‘code’.Footnote 2

Yet in a recent book, musicologist Martha Feldman divulged an uncomfortable truth: as a discipline, opera scholars tend to ‘speak of mezzos, lyric tenors, soubrettes, and so on, with varying degrees of historical and musical specificity’.Footnote 3 A small point, perhaps. But if talk about voice type is as variable as Feldman implies, how well can scholars really hope to communicate, much less engage in serious debate, about this elemental aspect of operatic practice?

As Feldman implied, scholars discuss voice type all the time, sometimes from a deeply historical perspective. Feldman herself has detailed a complex system of vocal classifications, character types and hiring practices in eighteenth-century Italy.Footnote 4 Elsewhere, Heather Hadlock and Naomi André have plumbed the meaning of the early nineteenth-century ‘trouser role’ and ‘second woman’.Footnote 5 And James Davies has shown how such seemingly natural voice types as the tenor were in fact developed by musicians, scientists and critics using ‘a whole raft of techniques and technologies’, including the laryngoscope, the lowered larynx and operatic works themselves.Footnote 6

Still, Feldman's remark betrayed a deeper reality: despite the pioneering work of scholars such as Hadlock, André, Davies and others, opera studies still lacks a robust framework for understanding the concept of voice type.Footnote 7 In everyday musicological parlance, such disparate singers as Gilbert-Louis Duprez, Enrico Caruso, Plácido Domingo and Freddie Mercury are all ‘tenors’.Footnote 8 Even the way scholars use the term ‘voice type’ varies a great deal: in recent years, scholars have described not only the familiar soprano or tenor voice but also the ‘low-voiced female jazz singer’, the ‘1st tenor’ and the ‘second woman’ as ‘voice types’.Footnote 9

The problem, to my mind, is largely a matter of method, for while we are relatively well equipped to describe individual voice types, we have focused less on the concept of vocal classification itself.Footnote 10 The aim of this article is to steer us towards a more thoroughgoing approach. I adapt a familiar tool from the broader field of voice studies – the notion of ‘ideologies of voice’ – for the study of voice type in particular. Scholars such as Amanda Weidman have used the phrase ‘ideologies of voice’ to describe ‘how … the voice [can] assume different significances in different times and places’ and ‘the technologies by which experiences of voice are constructed and metaphors of voice made to seem natural’.Footnote 11 Here, I propose the concept of ideologies of voice type. If voice types are the categories people use to classify voices, then ideologies of voice type explain how people understand such types and what they use them for. With this concept I hope to help move the conversation beyond the ‘varying degrees of historical and musical specificity’ to which we have become accustomed and towards a greater shared understanding of this ubiquitous feature of operatic culture.

I begin by surveying some aspects of modern-day ideologies of voice type common among opera critics, composers and scholars. I then turn to a historical example to show how the concept of ideologies of voice type can shed new light on operatic cultures of the past. My case study centres on Maurice Ravel, his 1911 opera L'heure espagnole and the relatively obscure voice type he assigned to the opera's male protagonist, Ramiro, the baryton-Martin. The idea of the baryton-Martin originated at the Opéra-Comique in early nineteenth-century Paris. While scholars have examined this early history in some detail, I follow the career of the baryton-Martin voice into the early twentieth century.Footnote 12 Drawing on a range of historical sources, I explain how by Ravel's time the idea of the baryton-Martin voice had come to be associated by some with an ethos of unaffected simplicity. I then show how Ravel seems to have composed this specific, turn-of-the-century notion of the baryton-Martin voice into the character of Ramiro. While scholars often interpret Ramiro as a manly character and L'heure espagnole as a story about sex and masculinity, I suggest that we can also read the opera as a story about the value of unaffected simplicity associated with the baryton-Martin voice at that time.Footnote 13

In addition to offering a history of the baryton-Martin voice type, I use this history to identify and explain the ideology of voice type Ravel adopted in L'heure espagnole. In this ideology, I argue, voice types express intrinsic aspects of the characters and their place in the drama. They are specific, audible and meant to be interpreted. Today such an ideology might seem conventional. As I discuss in the first part of this article, modern-day composers, critics and scholars often take many aspects of Ravel's ideology of voice type for granted. But as I demonstrate, the ideology Ravel adopted in L'heure espagnole, familiar as it is, was unusual for its time. This helps explain why most of Ravel's critics interpreted the opera in ways that ran counter to the opera's apparent design, and perhaps also why the deeper significance of voice type in the opera has remained hidden for so long. Ultimately, I hope to illustrate that the production and subsequent interpretation of operatic works has sometimes been shaped not simply by voice types and their cultural significance but also by conflicting ideologies of voice type at work within the same operatic culture. I conclude with some brief reflections on the ethical implications of various ideologies of voice type, including Ravel's and our own. As a means of classifying human beings, the concept raises questions about agency and identity that voice and opera studies must ultimately face.

What's in a type?

I define ideologies of voice type as the complex of ideas and practices that guide how individuals understand voice types and their relevance to the operatic experience. Though such ideologies inevitably vary from person to person, we can isolate aspects common to a particular operatic culture at a particular time. Singer and scholar John Potter sums up one common aspect of modern-day ideologies of voice type when he suggests that today opera-goers tend to hear a singer's voice type at least as much as they hear a singer's individual voice:

Our voices are like our faces, part of the essence that defines us as individuals. With modern training some of this individuality is sacrificed in order to produce a voice of the genus ‘tenor’, so that we recognise the voice rather than the person. Of course, we can still distinguish between individual tenors, but what we hear first and foremost is the tenor sound.Footnote 14

In this conception, voice types are what opera-goers notice ‘first and foremost’ about a singer, not unlike how a lover of dogs, passing one on the street, recognises it for its breed.

In the ideology of voice type Potter describes, voice types are fundamental to the operatic experience, a basic, even natural component of how opera-goers understand the genre. We can observe this perspective at work across different sectors of operatic culture today. Critics frequently hear a singer's voice type ‘first and foremost’. Consider the reaction to a spate of performances by singer Plácido Domingo. Though Domingo built a career around his identity as a ‘tenor’ – he became a household name in the 1990s as one of the Three Tenors – in the late 2000s Domingo began performing roles usually sung by baritones.Footnote 15 When Domingo took on one such ‘baritone’ role, the title character in Verdi's Simon Boccanegra, virtually every critic reported hearing first and foremost what they described as Domingo's ‘tenor’ sound. ‘Domingo projects Boccanegra's music into the audience with a tenor's glinting edge rather than a true baritone's heft’, wrote one critic, speaking for many, ‘and [Boccanegra] is a different man as a result’.Footnote 16 Domingo sounded like a tenor, not a baritone, with crucial implications for the opera and its meaning. Ironically, the singer who premiered the role in 1857, Leone Giraldoni, called himself a ‘baritono-tenore’.Footnote 17 But while modern-day ideologies of voice type encourage us to hear voice type first and foremost, they do not encourage much historical consciousness.

Composers today often subscribe to a similar ideology of voice type. In a recent interview, for instance, Jake Heggie explained that when he created the roles for his 2010 opera Moby-Dick, he began ‘thinking in terms of … what defines the character well, what range of voice and what color’ – in other words, what voice type.Footnote 18 Heggie related how friends, following the same logic, assumed the maniacal Captain Ahab would make a natural bass-baritone, but he thought the vocal qualities of another voice type, the heroic tenor, better captured the character. As Heggie explained, he pictured Ahab as ‘an inspired leader … the kind of person whose voice needs to sail over everyone else, so he can not only convey his message but draw them in, and that's a heroic tenor’ (eventually, the role was premiered by celebrated Wagner tenor Ben Heppner). Though they chose different options, Heggie and his colleagues all imagined Ahab as a voice type first and foremost.

Opera scholars, too, sometimes adopt ideologies of voice type similar to that of modern-day critics and composers. Often this appears as a tendency to place a high interpretive premium on the idea of voice type, even in the absence of justificatory evidence. Take, for example, a now classic essay by Carolyn Abbate in which she used the concept of voice type to analyse the character of Klingsor, the evil sorcerer of Wagner's Parsifal. According to Abbate, Wagner composed Klingsor in a range ‘a little high for a true bass’. Because of this, Abbate suggests, ‘some straining will be involved’ for performers of the role, and we should therefore read Klingsor as a strained character, a villain once but no longer ‘fully diabolical’.Footnote 19 Such a reading hinges on the idea of the ‘true bass’, a concept Abbate never explains.

Or consider a more recent example, which also happens to focus on Wagner. In an excellent study of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century operatic performance and reception (which I rely on later in this article), Karen Henson reads Wagner's 1865 essay ‘My Recollections of Ludwig Schnorr of Carolsfeld’ as an encomium to the tenor voice type. Yet this essay is not about the tenor voice type at all but about the individual singer named in the essay's title. When reading Wagner's account of Schnorr, Henson zeroes in on Schnorr's status as a tenor first and foremost. ‘For a composer who pushed tenors extremely hard and was hard to and about singers in general’, Henson writes, Wagner ‘left behind one of the most idealized accounts of the voice’.Footnote 20 In that essay, though, Wagner seems to critique the very idea of vocal classification, not endorse it. In a telling passage, Wagner uses the term ‘tenor’ to describe precisely what Schnorr is not. ‘Nature meant Schnorr for a musician and poet’, Wagner argues. ‘But behold! Our modern Culture had nothing to offer him save theatrical engagements, the post of “tenor”, in much the same way as Liszt became a “pianoforte-player”.’Footnote 21 According to Wagner's ideology of voice type, it would seem that the very notion of voice type corrupted art and debased artists. Nonetheless, Henson interprets Wagner's praise of Schnorr as praise for a voice type.

I call attention to these minor points in the work of Abbate and Henson merely to show how modern-day ideologies of voice type appear to shape how scholars think. Broadly speaking, such ideologies encourage us to hear singers and roles as instantiations of types, even when historical evidence would seem to point in a different direction.

Ideologies of voice type and Ravel's L'heure espagnole

Such discrepancies between modern-day and historical ideologies of voice type merit closer scrutiny. In his opera L'heure espagnole, Ravel adopted an ideology of voice type in which voice types are foundational to the opera's construction. Familiar as it is today, though, this ideology was not one that Ravel's contemporaries necessarily took for granted.

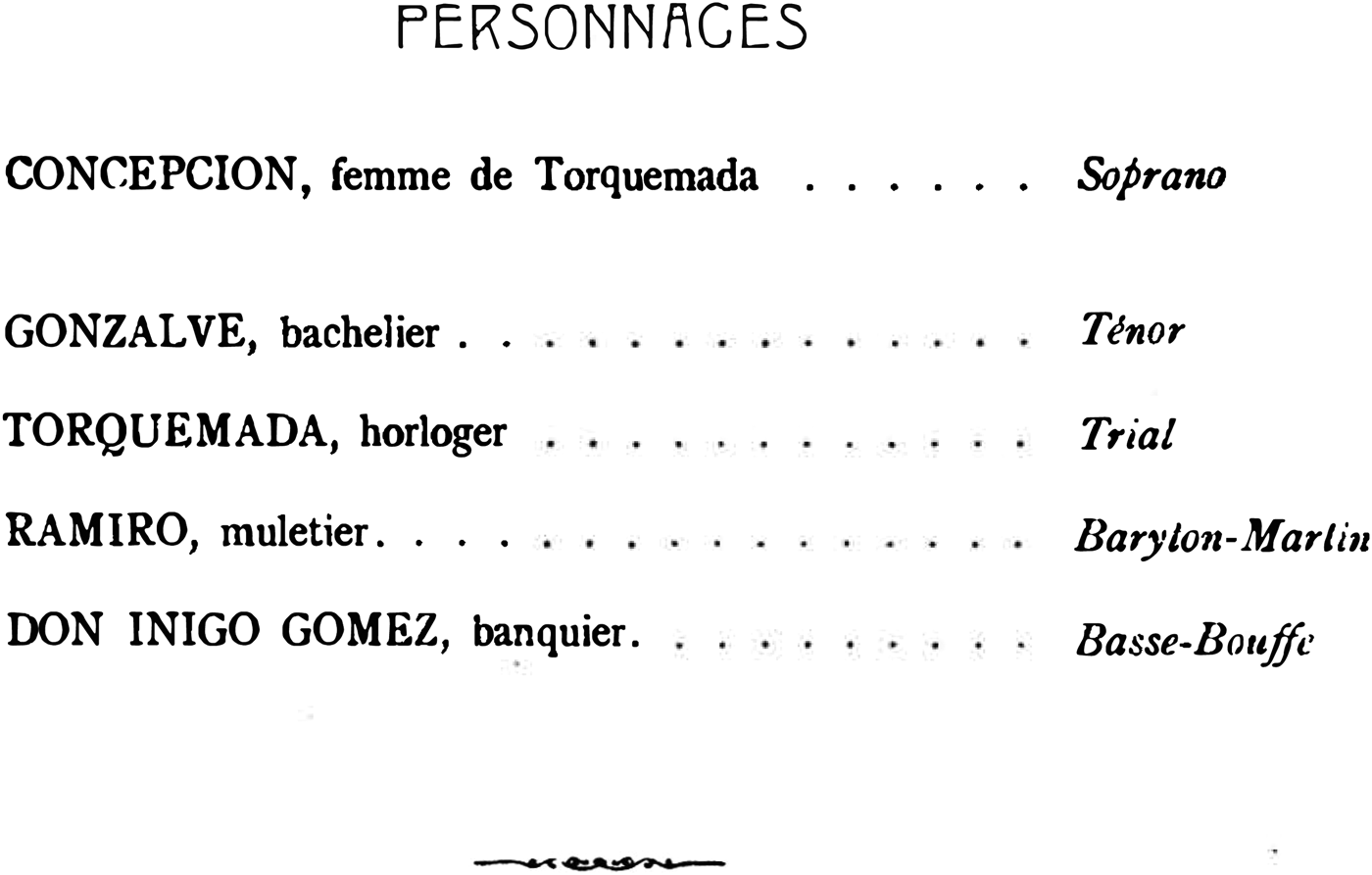

The 1904 stage play L'heure espagnole (‘The Spanish Hour’, or ‘Spanish Time’) by Franc-Nohain (pen name of Maurice Étienne Legrand) tells the tale of one Concepción and her dalliances in the absence of her unsuspecting husband, the clockmaker Torquemada. Ravel completed the opera in 1907, well before he knew where – or even if – it would be performed. In an unusual step, he had the piano-vocal score published immediately anyway, in 1908, three years before the eventual premiere.Footnote 22 In that score, Ravel indicated the voice type he assigned to each of the characters (Figure 1). In light of this, we can be fairly sure that Ravel's vocal casting was not an after-effect of the opera's eventual casting but part of the work's original conception.

Figure 1. Character list, L'heure espagnole, first edition vocal score (1908). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York, PMC 823. Credit: The Morgan Library & Museum, New York.

Loaded with pre-existing musical and characterological associations, the voice types define the characters, clarify their place in the drama and explain their actions. The mule driver Ramiro (baryton-Martin) arrives at the shop of Torquemada (trial) with a broken watch, and unwittingly inserts himself into a love triangle between Concepción (soprano) and two aristocratic would-be suitors, Gonzalve (ténor) and Don Iñigo (basse-bouffe). In the end, Concepción rejects the two aristocrats, having fallen for the unassuming Ramiro. The soprano Concepción invoked other cunning, overtly sexualised heroines of the Opéra-Comique – especially ‘Spanish’ ones such as Carmen (designated a mezzo-soprano in contemporary scores but often sung by soprano singers such as Geneviève Vix, who eventually created the role of Concepción).Footnote 23 One of Concepción's suitors, the loquacious ténor Gonzalve, was a spoof of tenor poet-lovers such as Rodolfo in Puccini's La bohème, which had recently arrived in Paris.Footnote 24 Throughout the opera, Gonzalve sings effusive melodies Ravel called ‘purposefully exaggerated’ – no doubt a reference to a popular contemporary stereotype of ténor singers, often belittled for being unwilling or unable to convey anything to audiences but the sheer beauty of their voices.Footnote 25 Concepción's other suitor, the pompous basse-bouffe Iñigo, recalled Gioachino Rossini's officious doctor Bartolo with his rambling patter and bumbling behaviour.Footnote 26 And though more obscure today, the trial voice Ravel assigned to Torquemada, Concepción's doddering husband, drew on a tradition of doltish characters in French opéra comique. Because a full explanation of Ramiro's baryton-Martin requires a lengthier discussion, I will save a complete analysis for later. As I will explain, the baryton-Martin would have been familiar to audiences as an old, conventional role type associated with Revolutionary- and Empire-era opéra comique; however, Ravel did not draw on the baryton-Martin of the early nineteenth century. Rather, he seems to have composed Ramiro as a more modern baryton-Martin, which by Ravel's day had come to be associated with an earthy identity, a fitting characterisation for the workaday Ramiro.

Ravel derived this classificatory design partially from historical precedent, though its final form was characteristically modern. Ravel described L'heure espagnole explicitly as the revival of an old genre – Italian opera buffa – in modern guise.Footnote 27 Scholars such as Steven Huebner have suggested numerous ways in which Ravel realised this ambition – including, for example, by basing his characters on stock voice and character types.Footnote 28 Instead of using voice types particular to the buffa tradition, though, Ravel selected voice types familiar in his own day.

Ravel integrated role and voice type with a thoroughness reflective of his celebrated attention to detail. He matched voice type and role at the level of character, vocality, musical characterisation and even performance practice. Consider the trial Torquemada. According to Albert Carré, who directed the Opéra-Comique from 1898 to 1914, the term trial referred to ‘naïve country folk, obtuse servants, Jocrisses, [and] clowns who sing la voix en fausset’ (the term ‘Jocrisses’ described a stock theatrical role type defined by simplemindedness but could also refer to a man easily manipulated by his wife).Footnote 29 In the opera, Ravel made the trial Torquemada's naiveté not only something audiences could see but something they could hear. At one point, Torquemada, ever the jocrisse, waxes lyrical about how much he is loved by Concepción, who in fact only longs for other men. Appropriately, Ravel marked Torquemada's line ‘la voix en fausset’. In this way, Ravel composed the sound of the trial directly into the score.

In the case of the ténor Gonzalve, Ravel was even more forceful. As mentioned, throughout the opera the stereotypical ténor sings explicitly ‘exaggerated’ lyrical lines. But according to Ravel's friend, the violinist Hélène Jourdan-Morhange, Ravel went so far as to suggest that a singer who failed to perform Gonzalve's voice type would destroy the opera's dramatic integrity. In the 1940s, Jourdan-Morhange remembered that Ravel ‘often repeated to us that he wanted Gonzalve ténorisant [singing like a ténor] … singers who interpreted this role tended too often to render the character ridiculous’.Footnote 30 Ravel did indeed ‘repeat’ this preference for a properly ‘tenorial’ Gonzalve, and not only to Jourdan-Morhange. In a 1932 letter to the singer Jane Bathori, Ravel likewise explained that Gonzalve should be sung ‘ténorisant à l'excès’ (like a ténor to the point of excess).Footnote 31 So foundational was the idea of voice type for Ravel that if Gonzalve failed to sound like a ténor, the character failed. Stripped of his voice type, the character became nonsensical, even ‘ridiculous’. In this way, Ravel integrated the idea of voice type into the opera at the level of dramatic structure, musical style and performance practice.

As mentioned, Ravel's ideology of voice type recalled the tradition of Italian opera buffa and its close cousin, French opéra comique. Nonetheless, following Huebner's separate analysis of L'heure espagnole, I argue that Ravel's ideology of voice type was characteristically modern.Footnote 32 One particularly modern aspect is this: in the opera, Ravel deployed voice type with characteristic ironic self-consciousness.Footnote 33 By drawing on familiar voice and character types, Ravel seems, in Huebner's words, ‘simultaneously to ground himself historically, that is to justify his project in light of a past model, and to distance himself from the tradition he names by satirising some of its vocal practices’.Footnote 34 The voice types Ravel used in L'heure espagnole not only express the drama but also, because they are so recognisable and even expected, become parodies of themselves, not to be taken wholly seriously.

This ironic use of voice type reinforces the opera's broader comedic design. Drawing a comparison with the philosophy of Ravel's contemporary Henri Bergson, Huebner argues that, in L'heure espagnole, the comedy derives from that which is artificial or predetermined about a character. According to Bergson, we laugh when people do not respond to the world with spontaneity or creativity but instead act according to their predispositions no matter the circumstances. Such mechanical, predictable and in this sense artificial behaviour, Bergson suggests, is the heart of comedy. As Bergson puts it, ‘In one sense it might be said that all character is comic, provided we mean by character the ready-made element in our personality, that mechanical element which resembles a piece of clockwork wound up once and for all and capable of working automatically.’Footnote 35

For Huebner, L'heure espagnole is just such a clockwork comedy: the stereotyped characters behave as their predispositions would predict, even in the most absurd circumstances. Here again, Huebner's analysis helps explain how Ravel used voice types in the opera. We might say that Ravel deployed voice types as ‘ready-mades’, objects with their own ‘automatic’ characteristics that needed only to be ‘wound up’ – composed and distributed to singers – to express their comedic ‘character’. Of course, for all this to work from an aesthetic point of view, voice types need to be recognised by audiences, and for that to happen they first need to be respected by singers. Torquemada had to sing en fausset; Gonzalve had to ‘tenor’. Here, in a nutshell, was Ravel's modern ideology of voice type. Ravel's gripes about his ténors and their failure to tenor already suggests how difficult a pill this ideology would be for at least some of his contemporaries to swallow.

Career of a voice type

Ravel's modern ideology of voice type and its challenge to the status quo are perhaps best exemplified in the character of Ramiro and his baryton-Martin voice. The term baryton-Martin descends from a star of the early nineteenth-century Opéra-Comique, the baryton Jean-Blaise Martin. As Olivier Bara has shown, Martin specialised in ‘cunning valets, Frontins, and humorous artisans’ and a ‘particular kind of vocal exhibitionism, including a fairly pronounced taste for cadenzas and ornamentation’.Footnote 36 He also distinguished himself with his impeccable comic timing, hilarious stage antics and wide vocal range. After Martin retired in the 1820s, opera professionals began referring to his specially designed roles as the ‘Martin’ emploi or role type. Thus when Martin retired, his replacement, Jean-Baptiste Chollet, signed a contract obliging him to sing ‘les rôles de l'emploi dit de Martin’ (‘the roles of the Martin emploi’). Chollet was hired to fill Martin's shoes in every respect, including voice, looks and stage comportment. But as was often the case in the so-called emplois system, eventually Chollet's place in the company evolved. When he established himself as a star in his own right, he too came to embody an emploi of his own.

Ravel and his contemporaries inherited the memory of Martin and his roles but adopted a conception of voice type particular to their own time and circumstances. During the second half of the nineteenth century, the emplois system (in Paris, at least) fell into decline. By century's end, singers’ contracts hardly mentioned role or voice types. Instead, singers typically committed to sing ‘all the roles old and new which will be assigned to me’, as Opéra-Comique boilerplate terminology in use from the 1850s to the 1910s put it.Footnote 37 Contracts at the Paris Opéra were often even more demanding, if not outright threatening, adding, ‘without power to refuse any, no matter the pretext’.Footnote 38

The story of this shift in practice is beyond my scope here, but it seems likely that the breakdown of the emplois system helped foster a new conception of voice type and of the baryton-Martin voice in particular. By the late nineteenth century, French writers tended to describe the baryton-Martin not so much as a role type encompassing the broad sweep of a singer's qualities and responsibilities, but simply as a voice with particular sonic characteristics. Many such commentators described the baryton-Martin as a voice with the same tessitura as that of Jean-Blaise Martin, which was said to span that of the typical ténor and baryton. As one journalist explained in 1912, ‘today we still say “baryton Martin” of a baryton who sings easily in a high-lying tessitura’.Footnote 39 Along these lines, both Jean-Baptiste Faure, the illustrious late nineteenth-century baryton, and composer and pedagogue Reynaldo Hahn described the Martin as a ‘baryton élevé’ (high baryton).Footnote 40

If Ravel's contemporaries generally agreed about the baryton-Martin's tessitura, on other details they were less clear. In 1867, Pierre Larousse defined the baryton-Martin as the ‘name given to a baryton voice whose exceptional timbre is the same as that of the famous singer Martin’, though what timbre Larousse had in mind, much less what made it exceptional, we can only guess.Footnote 41 Faure and Hahn both suggested that the voice was especially quiet, at least in comparison to what they referred to as the baryton d'opéra. Others likewise identified baryton-Martin voices as ‘little’ or lacking in ‘power’.Footnote 42 Still others seemed to suggest the opposite, associating the voice with ferocious high notes. For instance, one critic acclaimed the ‘true baryton-Martin’ Gabriel Soulacroix for the way he ‘poured forth on the high g♯s with the sangfroid of a force of nature’.Footnote 43 Along these lines, another critic explained that the title character in Ferdinand Hérold's Zampa (1831) – created for Martin's successor Chollet and often marked ‘ténor’ in nineteenth-century scores – was usually assigned to the singers that ‘one calls barytons-Martin, in honour of the famous Martin who, by the explosiveness of his high Gs and As, could equal the most vigorous ténors’.Footnote 44

As this latter example suggests, even though the emplois system had fallen out of use, the baryton-Martin voice did still carry dramatic associations.Footnote 45 Singers described as having baryton-Martin voices around 1900, such as the aforementioned Gabriel Soulacroix and others such as André Baugé and Max Bouvet, often played larger-than-life personalities that defied social norms.Footnote 46 For example, Hérold's Zampa, mentioned earlier, is a nobleman-turned-pirate who pays for his misdeeds with a fiery death. Other characters sung by singers described as barytons-Martin included Figaro in Rossini's Le barbier de Séville (simply labelled baryton in an 1897 French edition) and François in André Messager's François les bas bleus (not labelled with a vocal designation in contemporary scores). Equally cunning in letters and love, these characters rival Zampa in their lust for adventure. François is a poet and ‘friend of lovers’ whose star-crossed romance leads to arrest and, eventually, a thrilling escape on 14 July 1793; Rossini's Figaro is, of course, a self-championing ‘factotum’ and romantic mastermind. These characters tend to express their flair for the dramatic with an equally flamboyant vocality, glorying in high-lying fortissimo passages such as those found in Figaro's famous entrance aria. With their cunning ways and ‘vocal exhibitionism’, the characters associated with the baryton-Martin voice seem to have continued the legacy of the original Martin type into the twentieth century. But because hardly any composers used the term baryton-Martin in their scores, characters such as Zampa and Figaro are all we have to go on for how opera-goers understood the expressive associations of the baryton-Martin voice.

Unless, that is, we look beyond the opera house. For it was also around 1900 that yet another conception of the baryton-Martin voice and its associations began to take shape – one that ultimately explains the character of Ramiro and its place in L'heure espagnole. According to this turn-of-the-century conception, the baryton-Martin voice was not forceful or virtuosic but quiet and restrained. Here is how the famed Comédie-Française actor Ernest Coquelin described his own unaffected baryton-Martin voice in the 1890s: ‘I sing the romance with a barely audible baryton-Martin voice’ (‘filet de voix de baryton-Martin’), he told a Le matin reporter, adding, somewhat abstrusely, ‘no bear nor fisherman’.Footnote 47 With this reference, he was probably making a punning allusion to an earlier part of the interview, in which the interviewer jokingly compared Coquelin and his diminutive voice to two famous opera singers, Jean Lassalle and Jean de Reszké. With their resonant voices and larger-than-life stage personas, Coquelin seems to have implied, these giants of the operatic stage could have swallowed his filet de voix whole. In any case, Coquelin prized this diminutive voice precisely because it was so different from the grandiosity he seems to have associated with operatic expression. As he explained, with such a barely audible voice, he could do justice to his favourite kind of songs, those with a ‘fragile melody’ that ‘[evoked] ordinary people and things’ (‘d’êtres, d'objets terre-à-terre’). When Coquelin used this latter phrase, terre-à-terre, which might be literally translated as ‘down-to-earth’, he was not evoking a disarmingly unpretentious celebrity, as we might use this phrase in English. Rather, the phrase terre-à-terre implied that Coquelin's baryton-Martin, like the people and things he liked to sing about, was pedestrian, simple, even dull. Many French writers used the term pejoratively, but what some construed as an insult, Coquelin donned as a badge of honour. By describing his own voice as an ‘ordinary’ baryton-Martin, he seems to have been self-consciously renouncing ostentation in favour of an earthier way of being. This particular conception of the ‘ordinary’ baryton-Martin voice seems to have been especially popular among literati, including some in Ravel's circle.

In 1900 Franc-Nohain, the poet, playwright and soon-to-be librettist of L'heure espagnole, described the baryton-Martin in virtually the same terms Coquelin had used, even including the phrase ‘filet de voix de baryton-Martin’. The borrowed language may not have been coincidental: Coquelin admired Franc-Nohain's work, and the two may well have known each other from the time they both spent at the avant-garde haunt Le Chat Noir.Footnote 48 Franc-Nohain evoked the diminutive baryton-Martin voice in his 1900 poem ‘Musique d'ensemble’ (‘Chamber Music’). In the poem, Franc-Nohain eventually introduces a young husband. Soon, he begins to sing. And what voice do we ‘discover’ in this unassuming petit-mari?

Like Coquelin, Franc-Nohain describes the barely audible baryton-Martin by way of a comparison with the ostentatious world of opera. This time, the contrast is between the humble petit-mari and the opera star Victor Capoul. As contrasts go, this one was well chosen. According to Henson, Capoul was not only a star, he was a sex icon. He even had a hairstyle named after him – the ‘Capoul cut’ – that remained in vogue when Franc-Nohain published the poem.Footnote 50 As Franc-Nohain no doubt expected his readers to understand, if Capoul was the operatic idol of 1900, the petit-mari was an average joe. Appropriately, he sang not with a grosse voix d'Opéra like Capoul but with a barely audible baryton-Martin voice.

In France around 1900, to be ‘barely audible’ in this way was as much a political statement as it was an aesthetic one. As Katherine Bergeron has argued, many French artists, particularly actors and musicians, began to idealise understatement.Footnote 51 Composers such as Debussy and Fauré claimed to prize unostentatious music, while actors and singers cultivated an ethos of restraint, shunning what they considered the pretentious vocal displays characteristic of contemporary operatic performers. As Bergeron explains, this new, reserved aesthetic ideal went hand in hand with an emergent populism. Weary of the pretences of elite society, poets, musicians, educators and politicians looked to ordinary French folk as supposed models of simplicity and naturalness, qualities they deemed essential for a functioning republic. For those who embraced such values, Bergeron argues, quoting historian Philip Nord, ‘the building of a republican order required a new kind of man, one who eschewed pose in favor of sincerity’.Footnote 52 In the Belle Epoque, French artists who adopted this programme helped forge a movement promoting the intertwining values of populist politics and aesthetic reserve, a movement Bergeron dubs a ‘republican counterculture’.Footnote 53 In the imaginations of artists such as Coquelin and Franc-Nohain, the ‘barely audible’, ‘ordinary’ baryton-Martin would seem to have embodied a generation's aesthetic and political ideals.

By the turn of the twentieth century, the baryton-Martin voice had enjoyed quite a career. Born an emplois, it had over the decades acquired many new associations. While some opera-goers prized the vocal pyrotechnics of baryton-Martin singers such as Soulacroix, for others the voice had come to represent the very antithesis of operatic ostentation. Now, in another bit of Ravelian irony, Ravel was about to compose this latter, self-consciously unoperatic baryton-Martin voice onto the operatic stage. As I will suggest, Ramiro along with his baryton-Martin voice holds the key not only to a fresh interpretation of the opera but also to a deeper understanding of the role of voice type in contemporary French operatic culture.

Ramiro's baryton-Martin

When Ravel assigned the role of Ramiro the voice type baryton-Martin, he must have done so deliberately, for the term was hardly ever used in scores. As mentioned, Ravel, bucking convention, labelled the role as such in a score he published years before the eventual premiere. Unusual as it was, for one familiar with the ‘ordinary’ baryton-Martin type, the choice might have seemed obvious: in Franc-Nohain's libretto, Ramiro is nothing if not terre-à-terre. A mule driver by trade, Ramiro describes himself as a man of ‘laidback quietude’. He has ‘nothing to say, nothing to think about’, and that is OK with him. Demure to the point of self-deprecation, he constantly finds himself the butt of the more highfalutin characters’ jokes. At one point, for example, the pretentious Gonzalve teases that Ramiro could not possibly appreciate his poetry, which Gonzalve says he likes to pepper with obscure pagan symbolism.Footnote 54 As penned by Franc-Nohain, the down-to-earth Ramiro was a ready-made, ‘ordinary’ baryton-Martin.

From here, the vocal casting for the other characters would have suggested itself. As we have seen, both Franc-Nohain and Coquelin defined the ‘ordinary’ baryton-Martin against more overtly operatic voices (singers such as de Reszké and Capoul). Ultimately, Ravel likewise chose to define his own baryton-Martin, Ramiro, against Gonzalve, Iñigo and what Franc-Nohain might have called their grosses voix d'opéra.

In the opera this juxtaposition is particularly emphatic – and audible – for while Gonzalve and Iñigo compete for Concepción's affection in shades of forte and fortissimo (particularly in scenes 4 and 7 of the opera), the baryton-Martin Ramiro sings with a voice that is barely audible. In sharp contrast to Concepción's other suitors, Ramiro, in two extended soliloquies (scenes 10 and 16), sings only in shades of piano and pianissimo (Examples 1 and 2). As if anticipating the kind of rebellion that ultimately came to pass with interpreters of Gonzalve, into these soliloquies Ravel inserted copious, even gratuitous p and pp markings, not-so-subtle instructions that seem all but calculated to force performers to conform to the ‘barely audible’ baryton-Martin type. Admittedly, elsewhere Ravel does allow Ramiro some passages marked mezzo-forte or louder. But such exclamations tend to come when Ramiro is clearly uncomfortable, such as when he awkwardly greets Torquemada in scene 1, excuses his lack of manners in scene 3 or hauls heavy clocks in scene 8. When left alone on stage, where theatrical convention suggests he is at his most genuine, this baryton-Martin sings piano or softer. Like the trial Torquemada's voix en fausset and ténor Gonzalve's tenoring, Ramiro's filet de voix de baryton-Martin is clearly perceptible – not despite but because of its low volume.

Example 1. Dynamic profile of Ramiro's first soliloquy, L'heure espagnole, scene 10, bb. 1–35.

Example 2. Dynamic profile of Ramiro's second soliloquy, L'heure espagnole, scene 16, bb. 1–34.

Based on this evidence, that Ravel composed Ramiro specifically as an ‘ordinary’ baryton-Martin strikes me as more than likely. Yet there is further evidence: the score for the 1906 song cycle Histoires naturelles that Ravel composed as a study piece for the opera – and what he had to say about it. Scholars have observed many musical and dramatic connections between this cycle and L'heure espagnole.Footnote 55 Here is another: Ravel seems to have based Ramiro's musical characterisation on one of the cycle's songs, a mélodie entitled, aptly enough, ‘Le martin-pêcheur’ (‘The Kingfisher’). Compare Examples 1 and 2 with Example 3, which outlines the song's dynamic profile. As these examples suggest, ‘Le martin-pêcheur’ is as conspicuously quiet as Ramiro's monologues.

Example 3. Dynamic profile of Histoires naturelles, no. 4, ‘Le martin-pêcheur’.

The two martins also share specific musical material. In ‘Le martin-pêcheur’, the narrator tells how one evening a kingfisher swooped down to land on his fishing pole, mistaking it for a tree. In Ravel's musical setting, he highlights the appearance of the martin with a new tempo (‘Très calme’), a new time signature (7/8 compared with the previous 3/4) and a new musical motif in the piano right hand (Example 4). Six notes long, the motif begins on the offbeat with an ornamental flourish of parallel chords, followed by an upward melodic leap. After a beat's rest, the motif concludes with a brief repetition of the leaping gesture. We hear this figure – which I will call the martin motif – twice before the bird vanishes with a pair of bobbing ‘leaps’ (b. 14 in Example 4).

Example 4. The martin motif (bracketed), with ‘leap’ chords in b. 14, ‘Le martin-pêcheur’, bb. 12–14.

Ravel seems to have used the martin motif as the basis for Ramiro's thematic material. The similarity is plain from the start, when Ramiro arrives at Torquemada's shop (Example 5). Like the martin motif in ‘Le martin-pêcheur’, this initial statement of Ramiro's theme is in 7/8, stated twice over the course of two bars and capped by an echo of the motif's concluding gesture. Also like the martin motif, Ramiro's theme begins on the offbeat with a decorative semiquaver flourish of parallel chords and closes with a melodic upward leap. Ramiro's theme recurs in a number of variations but, as Example 6 shows, never strays far from the martin motif as stated in ‘Le martin-pêcheur’.

Example 5. Ramiro's theme, version 1 (bracketed), L'heure espagnole, scene 1, bb. 9–10, full score (some parts omitted).

Example 6. Examples of Ramiro's theme, with the martin motif for comparison (the spacing in some of the examples has been modified to show the alignment of beats).

And there is yet another connection between the martins in Histoires naturelles and L'heure espagnole: this one dramaturgical as well as musical. In Histoires naturelles, the final song of the cycle, ‘La pintade’ (‘The Guinea Fowl’), violently disrupts the quietude of ‘Le martin-pêcheur’ (Example 7). In L'heure espagnole, Concepción disrupts Ramiro's soliloquies with a similar blast of tremolos and triplets (Examples 8 and 9). Given all these musical and dramatic connections, it would seem that Ravel composed Ramiro very much in the spirit of ‘Le martin-pêcheur’.

Example 7. Histoires naturelles, no. 4, ‘Le martin-pêcheur’, and no. 5, ‘La pintade’, transition.

Example 8. Concepción interrupts Ramiro's first soliloquy, L'heure espagnole, scenes 10–11, transition.

Example 9. Concepción interrupts Ramiro's second soliloquy, L'heure espagnole, scene 16, bb. 31–4.

These connections matter because they help us understand Ramiro's affect. Throughout his career Ravel faced accusations that he composed in an artificial manner (Ravel famously retorted that perhaps he was ‘artificial by nature’).Footnote 56 But in a conversation with his friend Michel-Dimitri Calvocoressi, Ravel apparently listed examples of compositions in which he dropped this self-conscious artificiality for ‘direct’ expression; one such example, according to the composer, was the song ‘Le martin-pêcheur’.Footnote 57 I take this as further licence to speculate that Ravel imagined the martin Ramiro as a character as self-consciously unaffected as ‘Le martin-pêcheur’, and that we can hear in Ramiro's theme and barely audible monologues another example – a literal rehashing – of what Ravel considered self-consciously unaffected music. Taken together, Ramiro's terre-à-terre persona, barely audible voice and links to music Ravel himself described as knowingly unassuming all suggest that Ravel composed Ramiro as a specifically ‘ordinary’ baryton-Martin.

Such a reading sheds new light on the meaning of L'heure espagnole. As mentioned, today many interpret the opera as a story about sex, and for good reason.Footnote 58 The plot, after all, revolves around Concepción – whose name is suggestive enough – and her sexual adventures with Iñigo and Gonzalve, exploits that Ramiro frustrates only until Concepción falls for him instead and, at the end, even invites him into bed. Huebner interprets this raunchy tale as a commentary on sexuality, in which ‘sexual performance becomes the great factor of social equality’.Footnote 59 Michael Puri likewise reads the opera as an irreverent blessing of Ramiro and Concepción's approaching ‘sexcapades’.Footnote 60 Not surprisingly, commentators who adopt this argument tend to regard Ramiro primarily as a macho character. Huebner, for instance, hears in Ramiro's plodding theme a depiction of his hulking physique.Footnote 61

But if we stop and listen to Ramiro's filet de voix de baryton-Martin, he does not sound quite so macho. In a word, he sounds ‘ordinary’ – unabashedly simple, even naïve, a man more concerned with the concrete realities of mules and heavy lifting than the arts of poetry, conversation or seduction. In this, he appears to symbolise the kind of ordinary Frenchman idealised by members of what Bergeron calls the republican counterculture. To modern-day viewers, Ramiro attracts Concepción with his body (in today's parlance, he is a ‘barihunk’). Ramiro is surely ripped, for Concepción continuously sends him up and down her staircase carrying grandfather clocks, duties which Ramiro fulfils with a special pathetic enthusiasm. Still, perhaps it is Ramiro's simplicity – and not merely his muscles – that ultimately attracts Concepción, a woman who usually dallies only with supercilious bores such as Iñigo and Gonzalve. Ramiro is obviously burly, but if he is sexy, I would argue, it is only because he is so irresistibly terre-à-terre.

In the end it is the terre-à-terre baryton-Martin that Concepción chooses – not the highbred ténor or basse-bouffe. And so perhaps we should reread L'heure espagnole as a commentary not only on sexuality but also on the republican countercultural movement and its values. As Bergeron notes, in 1878 the French dramatist Ernest Legouvé spoke for the burgeoning movement when he wrote that ‘if the charm of the ancien régime was to be polite, the duty of democracy is to be sincere’.Footnote 62 L'heure espagnole would seem to affirm Legouvé's dictum. The aristocrats lose, and all because of a baryton-Martin who embodied the democratic sincerity Legouvé and others idealised. Sincerity in this sense was not so much a matter of meaning what you say – indeed, Ramiro hardly says anything at all. Rather, in this form of sincerity, one said whatever one had to say in the most unaffected way possible, without pose or artifice. As Bergeron argues, this was the ‘directness’ that Ravel said he allowed himself in the quiet song ‘Le martin-pêcheur’, which Ravel seems to have used as a study piece for the character of Ramiro. And it is this ‘directness’, this terre-à-terre way of being, that ultimately wins out in L'heure espagnole.

As we might expect, Ravel delivers this apparent lesson with a wink. The opera ends with a gaudy ensemble finale, complete with fantastical trills and overwrought habañera rhythms, in which the characters break the fourth wall to explain the moral. After such a barrage, it is hard to take the opera's conclusion entirely seriously. For Bergeron, Ravel never completely bought into republican countercultural values, an ambivalence the opera seems to confirm. For when the curtain comes down, all we know is this: the ‘ordinary’ baryton-Martin ‘has his day’. But to what end? What does the opera's raucous finale – so foreign to Ramiro's terre-à-terre way of being – portend? The opera leaves us hanging.

Of genus and genius

To accept this reading of L'heure espagnole, we first have to accept Ravel's ideology of voice type, an ideology, as I have argued, in which voice type is integral to the opera at the level of musical style, dramatic structure and performance practice. For it is only from the perspective of such an ideology that an interpretation of the opera based on the concept of voice type has any authority. As I now want to discuss, by way of conclusion, this was an authority that most of Ravel's contemporaries appear to have been unwilling or unable to accept.

Though critics had much to say about L'heure espagnole, most ignored the issue of voice type altogether. This was almost certainly not for lack of information. Because Ravel had published the piano-vocal score beforehand, complete with the voice types of each character, critics had ample opportunity to study the work and its classificatory scheme. Critics, immersed as they were in the Parisian operatic scene, would also likely have been familiar with the voice types associated with the original cast. Jean Périer in particular had been associated with the baryton-Martin voice since his Conservatoire days in the 1890s.Footnote 63 Separately, he had even at times been singled out for his low-volume singing. While Périer was still attending the Conservatoire, one of his professors took note of his ‘petite voix’ (‘small voice’).Footnote 64 Years later, in 1912, just one year after the premiere of L'heure espagnole, a reviewer praised Périer's turn as the title character in Mozart's Don Giovanni at the Opéra-Comique with these words: ‘The serenade … was but a whisper, but so pure and so penetrating … his duet with Zerlina was but a caress, but so tender and enveloping!’Footnote 65 Though this critic made no reference to the baryton-Martin, his description echoed Franc-Nohain's encomium to the filet de voix de baryton-Martin: ‘nothing but a wisp, but what a wisp! So pure, so musical’. Reviewing the same 1912 performance, another critic remarked, ‘M. Périer uses with intelligence and incomparable art a voice that only at times could have been louder.’Footnote 66 To my knowledge, no critic ever described Périer as an ‘ordinary’ baryton-Martin in the mould of Coquelin. Still, all the pieces were there, practically begging to be put together. Here was Périer, known at least to some as a baryton-Martin with a quiet voice, portraying a character seemingly custom-built to embody the barely audible baryton-Martin type and even identified, idiosyncratically, as a baryton-Martin in the score.

In the end, critics seem to have overlooked this aspect of the opera completely. Critics called Périer ‘top-notch’, ‘priceless’, ‘the top character actor in Paris’ and ‘an extraordinary singing actor’ – but not a baryton-Martin.Footnote 67 None that I am aware of so much as mentioned the term, or any other voice type, for that matter. Some critics described the opera as a farce, its characters caricatures.Footnote 68 Yet this perception did not lead them to the idea of voice type. Instead, unsympathetic critics concluded only that the characters ‘could not be more lacking in life and soul’, that the opera was little more than ‘a pointless adventure’, ‘as banal as it is coarse’, and its male protagonist, Ramiro, but a ‘sympathetic brute’, ‘proud of his muscles’.Footnote 69 Of course, it is possible that these critics did recognise Ravel's use of voice types and simply dismissed it as yet another insipid Ravelian joke. Even if this were the case, though, it is telling how easily these critics could dismiss such an approach. For them, it would seem, when it came to interpreting opera and its performance, voice type was hardly worth mentioning, if they considered it at all.

In fact, the only reviewer to even raise the issue of ‘types’, composer Gabriel Fauré, claimed that Périer had transcended types altogether. ‘Nothing could be funnier than Jean Périer as the muleteer furniture mover’, Fauré effused: ‘This superlative artist does not reproduce types [ne reproduit pas des types], he invents them’.Footnote 70 Here, Fauré implicitly acknowledged that Ravel designed his opera around stereotypes. Even so, for Fauré, Périer succeeded because he did not play to types at all but ‘invented’ a wholly original character by dint of sheer genius. Even and perhaps especially in an opera built of stereotypes, listeners such as Fauré valued individual artistry first and foremost.

As Henson has shown, such a focus on individual artistry was altogether typical for the time. In late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century France, musicians and audiences idealised what the star singer Victor Maurel called the operatic ‘interpreter’. Such a performer, Henson explains, excelled in bringing characters to life not merely through voice but also through ‘gestures, movements, and bearing’.Footnote 71 In this cult of the interpreter, audiences expected great singers not just to sing their roles but also to ‘interpret’ them, to pick them up and to shape them, and through them to manifest their singular gifts. It was Périer's knack for doing just this that wowed those who witnessed him interpret Ramiro. Today scholarship remembers Périer as a ‘typical’ baryton-Martin.Footnote 72 His contemporaries knew that Périer was not a typical baryton-Martin but an inimitable operatic interpreter. Three years after Périer's turn as Ramiro, one critic offered this prediction: ‘They will say “barytons Périer” like they say “barytons Martin” today.’Footnote 73 According to this critic's ideology of voice type, Périer could hardly be contained by a vocal type. Like all great interpreters, he was in a class of his own.

Some might argue that the critics who missed the significance of voice type in L'heure espagnole just did not pay enough attention. Maybe; but that, really, is the point. Critics did not pay attention to Ramiro's baryton-Martin because they did not share Ravel's modern ideology of voice type. If they noticed Ramiro's baryton-Martin at all, they loved Périer's interpretation more. The role of voice type in the opera eluded contemporary critics, and has eluded scholars since, at least in part, because the ideology of voice type Ravel composed into L'heure espagnole cut so sharply against the grain.

As the notion of the baryton Périer suggests, opera-goers who idealised the operatic interpreter did not necessarily reject the idea of voice type altogether. Instead, not unlike Wagner and his rueful account of Schnorr the ‘tenor’, they accepted the concept with some reserve, as if the idea itself, taken too seriously, would only get in their way. Many contemporary opera professionals seem to have felt this way. For instance, Claude Debussy composed the role of Pelléas in his 1902 opera Pelléas et Mélisande for a ténor voice. But when the director Carré offered the role to his star ténor Edmont Clément, the singer refused.Footnote 74 And so Carré cast none other than Périer. That Périer typically sang roles designated baryton mattered little, for according to Carré, the specifics of Périer's voice were irrelevant: ‘I found that it was not so much the voice that mattered for this singular role as the acting ability and the physical appearance’, he later remembered. ‘With his tall, slim profile and his sad, handsome look, Jean Périer seemed to me to be Pelléas himself.’Footnote 75 Carré evidently considered voice type of only minor importance: it was hardly elemental to the character or the opera. In Carré's ideology of voice type, theatrical genius trumped vocal genus.

Debussy apparently felt similarly. As David Grayson has shown, Debussy agreed to cast Périer as Pelléas and adjust some of the character's high-lying passages downward to better suit Périer's lower tessitura. Not only this, but Debussy also circulated the opera in multiple versions: his original version for ténor and one with the adjustments he made for Périer, both of which, with Debussy's encouragement, were widely performed.Footnote 76 At one point Debussy even considered rewriting the part for a female voice.Footnote 77 Unlike Ravel, Debussy does not seem to have complained when his ‘tenor’ role sounded something other than ténorisant.

Such an ideology of voice type appears to have been widespread among French composers. It was not only Debussy who published alternative versions of key roles. For example, in the score of his 1900 opera La basoche, composer André Messager designated the role of Clément Marot for either ténor or baryton. To accommodate such alternative casting, Messager published two versions of the part.Footnote 78 Composer Henri Rabaud did likewise for no fewer than four of the roles in his highly successful Mârouf, savetier du Caire (1914).Footnote 79 Other contemporary composers indicated in scores that certain roles could be performed by singers of different voice types – either ténor or baryton, for instance, or either mezzo-soprano or contralto – without publishing alternative parts.Footnote 80 For example, in the only operatic score I am aware of that used the term baryton-Martin prior to L'heure espagnole, the composer Eugène Diaz designated the title character of his opera Benvenuto (1890) for either ‘Ténor or Baryton Martin’ – no alternative parts necessary.Footnote 81

Some may argue that such openness to various voice types was merely a matter of practicality. There is surely truth in this: some composers would naturally prefer to have their operas performed rather than rejected for lack of the right singers. As Henson points out, turn-of-the-century composers were probably less invested in the idea of vocal classification than musicians tend to be today because the opera industry was not yet governed by a stable international canon.Footnote 82 From this standpoint, a less standardised performance culture around 1900 encouraged a more ‘flexible’ approach to voice type and casting. Yet the standardisation of the canon and performance culture was hardly inevitable, and we should not assume that all musicians around 1900 would have preferred a less ‘flexible’ approach to voice type. A better way of thinking about the issue, I suggest, is to consider that musicians around 1900 hoped most of all to hear the best interpreters available. From our perspective today, their approach to voice type may seem permissive, even reckless. But to them, our modern-day ideology of voice type, with all the weight it affords the concept itself, would probably seem dangerous. And in some ways it is.

Voice types are more than classificatory abstractions. Connected to ideologies of voice type, they guide how musicians live and work – for better or for worse. Earlier I cited John Potter's claim that today a singer's ‘individuality is sacrificed in order to produce a voice of the genus “tenor”’. With its zoological imagery, Potter's words expose this modern-day ideology's darker side: at its most base, it turns people into taxa, mere plots on a chart. As I have argued, in L'heure espagnole Ravel espoused a similar ideology of voice type, one that valued genus over genius, types over interpreters, ideas over people. In light of this, I feel some solidarity with those musicians who appear to have resisted Ravel's modern ideology of voice type, such as the ‘interpreters’ of the role of Gonzalve who, according to Ravel, refused to merely ‘tenor’ their parts. These singers, whoever they were, may have wrecked the opera's dramatic integrity, but at least they maintained their own.

Not all have been so empowered. Consider the fate of famed French singer Jacques Jansen (1913–2002). Jansen identified fiercely with the baryton-Martin voice type, so much so that, by his own account, he refused to accept roles associated with other vocal classifications. In the 1970s Jansen admitted that he had ‘dreamed, like everyone’ of singing tenor roles and that he even ‘had easy [tenor] high Cs’. Impresarios offered, Jansen declined. ‘J’étais baryton Martin’ (‘I was a baryton Martin’), he said. These were dream-puncturing refusals, refusals in which Jansen sacrificed a part of himself on the altar of voice type. Ironically, Jansen seems to have made this sacrifice based, at least in part, on the misbegotten notion that the character of Pelléas, which he performed widely, was essentially a baryton-Martin role. Asked why he refused tenor roles, he replied, simply, ‘In my heart of hearts, I wanted to remain faithful to Pelléas: I owe him the greatest joys of my existence.’Footnote 83

Jansen knew what it meant to sacrifice his individuality to produce a voice of the genus baryton-Martin. It was a sacrifice of joy tinged with profound sadness.