INTRODUCTION

When people come here to fulfill their dreams—to study, invent, contribute to our culture—they make our country a more attractive place for businesses to locate and create jobs for everybody.

—President Barack Obama, State of the Union Address (January 28, 2014)For decades, open borders have allowed drugs and gangs to pour into our most vulnerable communities. They’ve allowed millions of low-wage workers to compete for jobs and wages against the poorest Americans. Most tragically, they have caused the loss of many innocent lives.

—President Donald Trump, State of the Union Address (January 30, 2018)These statements—just four years apart—represent two very different perspectives on immigration from two very different presidents. Given the vitriolic and xenophobic nature of President Trump’s words, it is not surprising that this type of rhetoric has received extensive scrutiny from the public and academics alike. Indeed, as many scholars have noted, negative discourses about Latinx immigrants actively work to create bright boundaries that distance the racialized Latinx immigrant “Other” from the dominant group (Alba Reference Alba2005; Fox and Guglielmo, Reference Fox and Guglielmo2012; Wimmer Reference Wimmer2008; Zolberg and Long, Reference Zolberg and Woon1999). But what about seemingly positive messages, such as those advanced in the above quote from President Obama? Do these sympathetic discourses challenge racialized stereotypes of Latinx immigrants? Do they blur the lines between “us” and “them”? Or do they sometimes sharpen those boundaries?

This is an especially important line of inquiry given the nature and prevalence of colorblind racial ideology today. In 2003, sociologist Eduardo Bonilla-Silva published Racism without Racists, a groundbreaking analysis of the ways in which seemingly race-neutral language has been used in the post-civil rights era to deny, mask, or justify ongoing racial and ethnic inequalities. Now in its fifth edition, Bonilla-Silva (Reference Bonilla-Silva2017) argues that these changes in discourse corresponded with broader cultural shifts away from open expressions of racial prejudice to subtler expressions of preference based on neoliberal, ostensibly race-blind ideas about individual merit and personal responsibility.

While much scholarship has shown how these kinds of discourses can demean racial and ethnic minorities (Alcalde Reference Alcalde2016; Aranda et al., Reference Aranda, Chang, Sabogal, Cobas, Duany and Feagin2009; Armenta Reference Armenta2017; Gallagher Reference Gallagher2003; Sáenz and Douglas, Reference Sáenz and Douglas2015), less attention has been given to the ways colorblind rhetoric can also be used to uplift them. This dearth of research has created a gap in our understanding of how colorblind ideologies continue to operate and evolve in contemporary times. We fill this gap through an analysis of 1383 frames in front page New York Times articles between 2001 and 2019. Comparing the positive framing of articles about Latinx immigrants with that of non-Latinx immigrants, we show how even (seemingly) positive depictions racialize Latinx immigrants by emphasizing their exploitability, foolish vulnerability, and (presumed) illegality. We also found a single commonality between media representations of Latinx and non-Latinx groups: portrayals emphasizing family and adherence to traditional gender roles. Our analysis shows the flexibility of colorblind discourse to prop up existing racial hierarchies in U.S. society and to “Other” racial and ethnic minorities. More specifically, we show how the use of ostensibly positive colorblind rhetoric, like its overtly negative counterpart, obscures the racialized dimensions of some of our most divisive social issues and reinforces inequalities.

RACIALIZATION, COLORBLIND RACISM, AND LATINX IMMIGRANTS

Like most race and ethnicity scholars today, we view race as socially constructed through the process of racialization. Racialization refers to how a group of people, set apart by phenotypic and cultural markers, become associated with specific traits, expectations, or behavioral tendencies (Alcadle Reference Alcalde2016; Golash-Boza Reference Golash-Boza2006; Omi and Winant, Reference Omi and Winant1994). As originally described by Michael Omi and Howard Winant (Reference Omi and Winant1994), racialization is a profoundly consequential, ongoing process that emerges out of a particular socio-historical context. Racial categorization influences how groups relate to and perceive one another and also serves as the basis for prejudice and discrimination (Lamont and Molnár, Reference Lamont and Molnár2002; Lamont et al., Reference Lamont, Beljean and Clair2014; Omi and Winant, Reference Omi and Winant1994). By drawing distinctions between “deserving” and “undeserving” groups, socially constructed racial categories are used to legitimate an unequal distribution of resources and advantages (Alba Reference Alba2005; Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva1997; Saperstein et al., Reference Saperstein, Penner and Light2013; Yoo Reference Yoo2008). Indeed, the process of racialization undergirds America’s racial hierarchy and upholds notions of White supremacy.

Latinxs, both native-born and immigrant, have long experienced racialization in the United States. José Cobas and colleagues (Reference Cobas, Duany and Feagin2009) assert that for Latinxs, racialization began with early depictions of indigenous Americans and continued into the mid-1800s when White Americans justified their conquest of Mexican land by claiming that Mexicans were inferior and incapable of governing themselves. These initial encounters with early Mexicans set the racialized trajectory for subsequent Latinx immigrants and their descendants in America, who continue to encounter social exclusion and hyper-exploitability in labor markets (Blauner Reference Blauner and Takaki1987; Cameron and Cabaniss, Reference Cameron and Cabaniss2018; Glenn Reference Glenn2015).

Today’s racialization is far more subtle and covert. In his pioneering work on colorblind racism, Bonilla-Silva (Reference Bonilla-Silva2017) shows how many people—especially Whites—use ostensibly race-neutral language to deny, mask, or justify ongoing racial and ethnic inequalities. The popular view among Whites in the United States is that the passage of civil rights laws in the 1960s and 1970s removed all lingering racial barriers to opportunity (Winant Reference Winant2009). The impressive achievements of individual minorities, such as Barack Obama or Oprah Winfrey, are held up as proof that we have transcended our racist past and that our social, political, and economic systems are now open and accessible to all. From a colorblind perspective, “race” and “racism” no longer have any bearing on one’s position in these hierarchies, and anyone who continues to experience disadvantage has only themselves to blame (Gallagher Reference Gallagher2003).

However, as Rogelio Sáenz and Karen Manges Douglas (Reference Sáenz and Douglas2015) note, immigrants of color are still “racial beings” who face ongoing barriers in the United States: “Although the White litmus test was lifted from U.S. laws, it clearly survives in other—colorblind—forms” (p. 171). Research indicates that Latinxs indeed experience racialization and colorblind racism in unique ways. Elizabeth Aranda and colleagues (Reference Aranda, Chang, Sabogal, Cobas, Duany and Feagin2009) find that native-born Latinxs in Miami engage in colorblind racism against Latinx immigrants by making normative distinctions between “deserving” and “undeserving” immigrants based on perceived cultural differences between the groups. Contemporary Whites also use narratives of cultural deficiency to distance themselves from Latinxs (Lacayo Reference Lacayo2017) and “Other” this group through microaggressions (Ballinas Reference Ballinas, Smith and Thakore2016). Cristina Alcalde (Reference Alcalde2016) similarly found that university students in Kentucky rejected notions of “old-fashioned” racism but continued to racialize undocumented Latinx immigrants by using the colorblind rhetoric of “illegality.”

At the institutional level, immigration and enforcement policies that target Latinx immigrants also contribute to the racialized construction of “illegality,” creating consequences for both Latinx immigrants and the native-born Latinx population (Arriaga Reference Arriaga2016; De Genova Reference Genova and Nicholas2004; Flores and Schachter, Reference Flores and Schachter2018; Golash-Boza and Hondagneu-Sotelo, Reference Golash-Boza and Hondagneu-Sotelo2013; Pickett Reference Pickett2016). Amada Armenta (Reference Armenta2017) found that local law enforcement agents routinely used colorblind ideologies that emphasized “illegality” to justify stopping and detaining Latinx drivers for minor traffic offenses. Tanya Golash-Boza and Pierrette Hondagneu-Sotelo (Reference Golash-Boza and Hondagneu-Sotelo2013) argue that the disproportionate targeting of Latino men for deportation constitutes a state-sponsored “gendered racial program” (p. 271).

As this extant body of research shows, the racialization of Latinx groups transpires through systematic racism where oppression, at both the interpersonal and institutional levels, intersects with cultural ideologies of superiority and inferiority to reinforce and justify their low placement in the U.S. racial hierarchy. Most of this scholarship has focused on overtly negative or xenophobic discourses—albeit those that are colorblind in nature. That is, even though claims of undeservingness and illegality may not be openly racist, they are still disparaging and create bright, seemingly impenetrable boundaries between “us” and “them.”

However, we know from previous research that boundaries sometimes shift, moving from bright to blurry to nonexistent (Alba Reference Alba2005; Fox and Guglielmo, Reference Fox and Guglielmo2012; Wimmer Reference Wimmer2008; Zolberg and Long, Reference Zolberg and Woon1999). For example, individuals may engage in boundary-crossing by moving from one group to another without any perceptible change to the boundaries themselves. Another option involves boundary blurring, where distinctions between different social groups become less salient. Lastly, boundary shifting happens when the structure of the boundaries fundamentally changes so that populations once excluded become included. For example, Mara Loveman and Jeronimo O. Muniz (Reference Loveman and Muniz2007) demonstrate that a change in the definition of Whiteness prompted the rapid classification of a large number of people as White in Puerto Rico. Thus, it is at least possible that Latinx immigrants may be experiencing boundary shifting or blurring. If this is happening, we would expect this to be reflected in positive discourse about this group. However, in today’s era of colorblind racism where systems of inequality operate in more covert ways, these same discourses may also reinforce racial and ethnic boundaries.

THE ROLE OF THE NEWS MEDIA

The news media is an ideal institution for examining positive narratives about Latinx immigrants. A critical function of this institution is to report on the activities of other institutions, such as the government, schools, and economy (Altheide Reference Altheide2013), many of which play a significant role in the racialization process. News media also exert considerable influence over public discourse by setting the agenda: editors decide which stories to feature, thereby conveying to audiences which topics are important and “news-worthy” (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Scheudele and Schanahan2002). In regions where immigration receives more media attention, people are more likely to believe it is the most pressing problem facing the nation (Branton and Dunaway, Reference Branton and Dunaway2009).

The news media also influence society by framing topics in particular ways (Gamson et al. Reference Gamson, Croteau, Hoynes and Sasson1992; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Scheudele and Schanahan2002; Saguy et al., Reference Saguy, Gruys and Gong2010). Drawing on Pierre Bourdieu’s (Reference Bourdieu, Jerome and Halsey1977) theory of cultural reproduction, Deenesh Sohoni and Jennifer Bickham Mendez (Reference Sohoni and Sohoni2014) argue that the media represent a forum through which actors engage in a cultural and symbolic struggle over the social construction of reality. Since many Americans do not regularly interact with immigrants, media plays a significant role in shaping public perceptions and responses to them (Padín Reference Padín2005). News coverage of crime and immigration, for instance, contributes to persistent tendencies by Americans to associate immigrants with increases in crime, despite evidence to the contrary (Sohoni and Sohoni, Reference Sohoni and Sohoni2014). By continually drawing associations between immigrants and crime, media help construct and reinforce the “Latino threat narrative” (Chavez Reference Chavez2013; Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, Pitts and Osborne2011) that is often used to justify restrictionist policies (Sohoni and Mendez, Reference Sohoni and Mendez2014). Similarly, Daniel J. Hopkins’ (Reference Hopkins2010) work on politicized places shows how national media discourse, coupled with rapid increases in immigrant populations, can heighten anxieties about immigration among the native-born. Furthermore, experimental research finds that the type of frames used to discuss immigration influences support for various immigration policies (Bloemraad et al., Reference Bloemraad, Silva and Voss2016; National Hispanic Media Coalition Reference Barreto, Manzano and Segura2012) and even political party affiliation (Abrajano and Hajnal, Reference Abrajano and Hajnal2015).

There are striking parallels between the media representations of Asian and European immigrants at the turn of the twentieth century and Latinx immigrants today. In the past, it was common to see certain classes of immigrants depicted in mainstream U.S. newspapers as racially inferior to White Anglo Saxon Protestants. Newspapers routinely stereotyped Chinese immigrants as disease-ridden and dirty; Irish peasants as prone to alcoholism, brawling, and crime; and Italians as low-class criminal types (Lee Reference Lee2007; Ngai Reference Ngai2004; Sáenz and Douglas, Reference Sáenz and Douglas2015). In modern times, similar patterns have emerged in the cultural depictions of Latinx immigrants. Much like what we saw a century ago, the media often portrays these immigrants as hostile, foreign invaders threatening to overtake White America (Chavez Reference Chavez2013; Santa Ana Reference Santa2002).

At the same time, media representations of today’s immigrants have also become less overtly disparaging. Amidst the rise of colorblind racial ideology, derogatory portrayals often appear race-neutral. For example, advocates for “securing the border” (between the United States and Mexico) or revoking birthright citizenship for the children of undocumented immigrants often argue against rewarding those who would seek to enter the country “illegally” rather than against Latinx immigrants per se (Bloch Reference Bloch2014). Without invoking race or ethnicity, they nonetheless tie this group to notions of criminality and immorality and thereby reinforce their lower position in America’s racial hierarchy. Clearly, colorblind rhetoric can be just as effective as openly racist language in creating negative, racialized images of a group (Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva2017; Gallagher Reference Gallagher2003; Sáenz and Douglas, Reference Sáenz and Douglas2015).

A prominent theme centers on Latinx immigrants as fiscally harmful to the state (i.e., burdening the welfare system) and to the nonimmigrant population (i.e., taking jobs away) (Chavez Reference Chavez2013; Deckard and Browne, Reference Deckard and Browne2015; Martinez-Brawley and Gualda, Reference Martinez-Brawley and Gualda2009; McElmurry Reference McElmurry2009; Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, Pitts and Osborne2011). Prior research also finds that news articles commonly portray immigrants as cultural and demographic threats to the United States (Chavez Reference Chavez2013; Flores Reference Flores2003; McConnell Reference McConnell2011; Padín Reference Padín2005). Even a seemingly objective aspect of journalism—coverage of Census statistics—can present a biased perspective. Ellen Díaz McConnell (Reference McConnell2011) found that newspapers report rates of population change for Latinx and Asian immigrants far more often than for Whites and Blacks. This coverage often includes inflammatory language, characterizing these changes as “whopping” or “an explosion.” Lastly, researchers find that the news media frequently describe immigrants as threats to national security and public safety (Brown Reference Brown2013; Brown et al., Reference Brown, Jones and Becker2018; Martinez-Brawley and Gualda, Reference Martinez-Brawley and Gualda2009; Sohoni and Sohoni, Reference Sohoni and Sohoni2014), an especially powerful message that preys on the fears of a mostly White, native-born audience (Glassner Reference Glassner2010).

This expansive body of scholarship provides invaluable insight into how negative discourse associated with Latinx immigrants contributes to their racialization. Recent research examining counter-discourses has also shed light on this process, finding that factors such as the language of the newspaper (López-Sanders and Brown, Reference López-Sanders and Brown2020) and its intended audiences (Browne et al., Reference Browne, Deckard and Rodriguez2016) complicate interpretations of the negative depictions described above. However, positive discourse has received scant attention. An exception to this is Jorge Ballinas’ (Reference Ballinas, Smith and Thakore2016) research on the supportive media coverage of two successful, well-known Latinx immigrants. He found that even sympathetic profiles used colorblind rhetoric and downplayed the systematic nature of racism and emphasized immigrants’ personal achievements. Our study builds on Ballinas’ work by asking more broadly: What are the prevalent positive news media representations of Latinx immigrants? How do we make sense of these discourses? What do they tell us about the ongoing racialization of today’s Latinx immigrants?

DATA AND METHODS

Data Collection

To answer these questions, we examined newspaper articles on immigration printed on the front page of The New York Times (NYT) between 2001 and 2019. We selected this paper because it has the largest national circulation rate (Doctor Reference Doctor2015), influences reporting by other news outlets (Gans Reference Gans1979), and occupies an elite status in the newspaper industry (Martin and Hansen, Reference Martin and Hansen1998). Given the newspaper’s reputation for being liberal and having a more left-leaning audience base (Pew Research Center 2014), we would expect this outlet to be especially sympathetic in its portrayals of immigrants (Abrajano and Hajnal, Reference Abrajano and Hajnal2015). We narrowed our focus to front-page articles because they are the most accessible to the public, newspapers promote them via other mediums (i.e., their websites and apps), and editors use them to compete for readership. While our analysis excludes certain articles (i.e., those not on the front page, editorial/op-ed pieces), the prominent position of front-page articles offers meaningful insight into the NYT’s role in racializing Latinx immigrants.

The period we selected, 2001–2019, spans key historical events including 9/11, the 2008 economic crisis, four Presidential elections, and the rise of state-level immigration restriction laws. While we acknowledge that racialization is an ongoing, sociohistorical process that unfolds over time, given the truncated span of our data, we provide only a preliminary longitudinal analysis of emergent patterns. We discuss the importance of longitudinal data as it relates to the racialization process more thoroughly in our conclusion.

We collected our data through LexisNexis Academic by searching for NYT front-page articles. To ensure that immigration was the main subject of the article, we selected pieces that contained the terms “immigra*,” “emigrant*,” “undocumented,” “alien*,” “foreigner*,” or “illegal*” in their titles and the words “immigrant*” or “emigrant*” in the full text. We excluded articles that were not about U.S. immigration (e.g., articles about the Syrian refugee crisis). This initial search yielded 170 articles. We first sorted the articles based on the overall sentiment expressed—mostly negative, positive, or neutral—although most of the articles contained elements of all three. We considered discourse that was less receptive to immigrants or emphasized hostile responses to immigrants as negative. For example, an article titled “As Illegal Workers Hit Suburbs, Politicians Scramble to Respond” described the strain immigrants put on suburban neighborhoods and the burden they pose for politicians (Vitello Reference Vitello2005). In contrast, we interpreted text that was more receptive to or advocated on behalf of immigrants as positive. For example, an article titled “Illegal Immigrants Are Bolstering Social Security with Billions” attested to the substantial sums migrant workers pay into Social Security (Porter Reference Porter2005). Most of the articles classified as neutral described some aspect of immigration policy and focused on the political activities of lawmakers. After establishing the positive-negative-neutral criteria collectively, we divided the articles for an initial sort. We repeatedly met over several weeks to discuss and double-check how we categorized the articles. In cases of ambiguity, each member of the research team read the article in question, discussed points of disagreement, and came to a consensus about how to classify it. Through this collaborative process, we categorized twelve articles as mostly critical of immigrants, 105 as neutral, and eighty-four as sympathetic. For this paper, we drew our analysis from the articles we classified as predominately positive.

Some of these positive articles discussed immigration as a broad category, while others referenced specific immigrant groups. While we are most interested in understanding the role of positive discourse in the racialization of Latinx immigrants, we also recognize that this process does not take place in a vacuum; groups are often constructed in relation to one another (Kim Reference Kim1999). Thus, our analysis incorporates an element of “racial triangulation,” where we gain a clearer understanding of racialization by comparing positive discourse about Latinx immigrants with that of non-Latinx immigrants. Triangulation is useful for exposing the more implicit and subtle dimensions of positive framing.

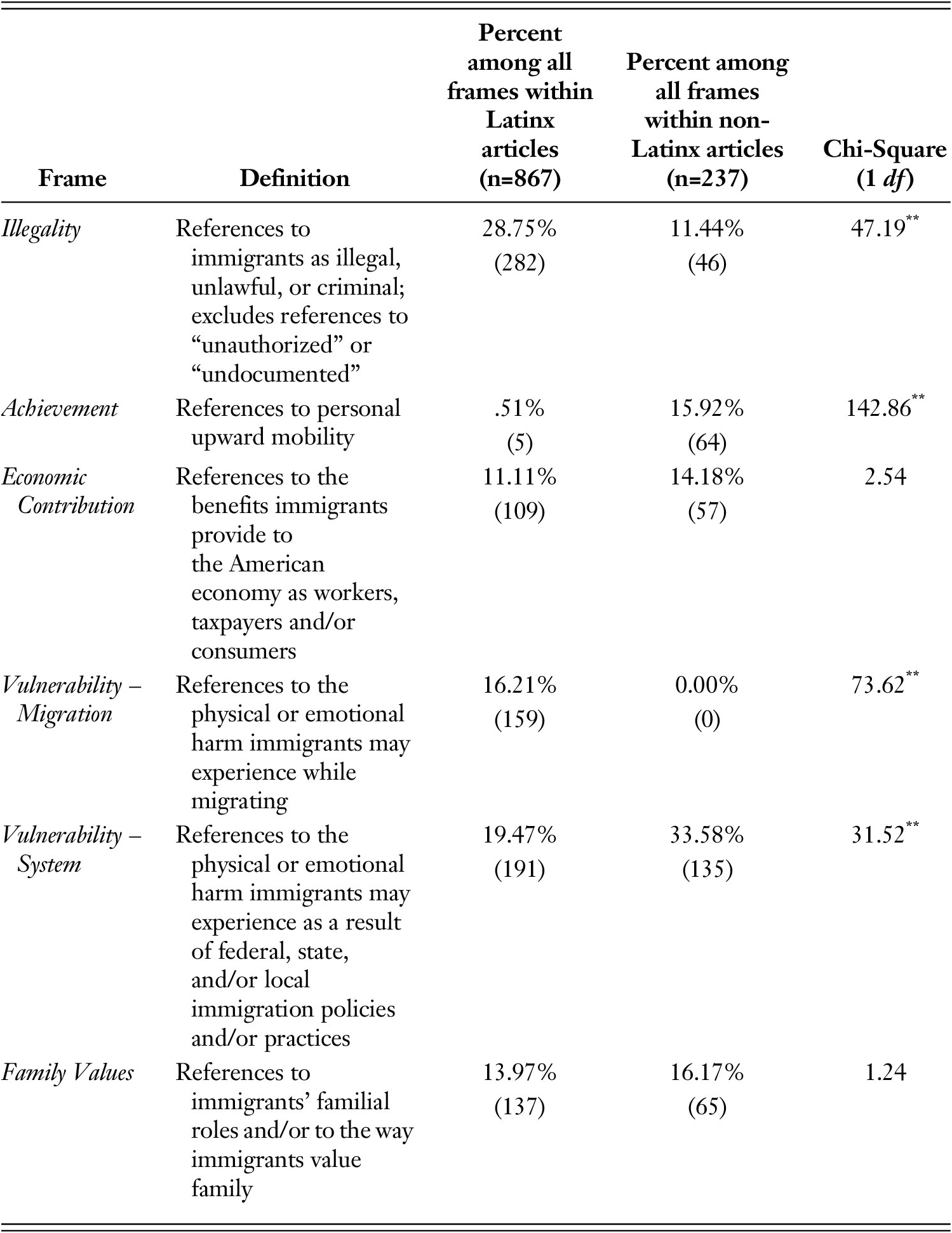

Accordingly, we classified articles that explicitly and exclusively referenced immigrants from Latin American nations as “Latinx” (n = 50). The remainder of the positive articles either referenced immigrants from other nationalities, multiple immigrant groups, or immigration more broadly without reference to specific nationalities.Footnote 1 Because Latinx immigrants were not the focus of these articles, we refer to them as “non-Latinx” articles (n=34). As is customary (McConnell Reference McConnell2018), we performed chi-square (X2) tests of two-by-two contingency tables in order to determine if quantitative differences were statistically significant (Table 1).

Table 1. Prominent themes in positive, front-page coverage of Latinx and Non-Latinx immigrants in New York Times coverage (2001–2019).

Note: Paragraphs could include multiple themes. Frequencies in parentheses.

*p<.05; **p<.01

Data Analysis

We used frame analysis to examine positive newspaper discourse in our study. Erving Goffman (Reference Goffman1974) describes frames as “definitions of a situation [that] are built up in accordance with principles of organization which govern events—at least social ones—and our subjective involvement in them” (p. 10). Frames set the parameters for how social actors speak, think, and write about an issue, and thus, help make sense of the world. They also make some ideas more salient than others by highlighting particular bits of information or ways of thinking (Entman Reference Entman1993). As William Gamson and Andre Modigliani note, “Media discourse can be conceived of as a set of interpretive packages that give meaning to an issue…At its core is a central organizing idea, or frame, for making sense of relevant events, suggesting what is at issue” (Reference Gamson, Modigliani and Braungart1987, p. 3).

We approached our data with interest in the depictions of immigrants but were otherwise open to examining themes as they emerged. In that sense, our approach was quasi-inductive. We began by conducting two pilot analyses on a portion of text. Each member of the three-person research team read the same articles, noting emergent themes related to race-based frames. We used this preliminary analysis to establish a codebook that included category names, definitions, and examples.Footnote 2 We went through two rounds of testing and revising the codebook and discussed disagreements as they arose. Once we achieved intercoder reliability, we divided the articles and proceeded to code them individually. Our coding categories included achievement, family values, illegality, vulnerability (migration or immigration system); and economic contributions (see Table 1 for definitions and descriptive information). To standardize our analysis, we applied these codes at the paragraph level. There were 3088 paragraphs across all eighty-four positive, front-page articles, with each article containing an average of 36.76 paragraphs. Latinx articles contained 1820 paragraphs; non-Latinx articles contained 1268.

We used NVivo 11 to code and analyze our data because of its ability to accommodate large bodies of text, easily identify emergent patterns, and allow multiple users. Due to the nature of our data, not all paragraphs received a code (i.e., some did not reference the primary themes we established), and some received more than one (i.e., by referencing more than one theme). After our initial round of focused coding, we revisited the coded text to see how these frames were portrayed. For example, paragraphs labeled “achievement” were re-examined to determine if achievement was discussed as individual achievement or achievements for a community or group. In total, we applied our frames to 1383 paragraphs. Of those, 981 came from articles on Latinx immigration, 402 from non-Latinx articles.

FINDINGS AND ANALYSIS

Latinx Immigrants Are Exploitable…but in a Good Way

One of the most prevalent themes in our data emphasized how immigrants serve the American economy as workers, taxpayers, and consumers. As reported in Table 1, the proportion of this frame within Latinx and non-Latinx articles appears to be quite similar. However, a closer examination reveals meaningful differences. First, articles featured this frame for the two groups in significantly different time periods. Portrayals of Latinx immigrants as contributors to the economy were prominent throughout the period we examined but were especially prevalent in 2005 and 2007. These years bookend the contentious immigration debates of 2006, and the paper’s depiction of Latinx immigrants during this time echoes some of the language used by immigrant rights advocates to raise awareness of the importance of Latinx immigrants to the U.S. economy (Voss and Bloemraad, Reference Voss and Bloemraad2011). In contrast, portrayals of non-Latinx immigrants as workers and consumers were virtually absent from 2001 to 2016, but then exploded in 2017. As with the Latinx immigrant articles, this shift is likely in response to significant changes in the political landscape surrounding immigration, in this case, the emergence of Donald Trump’s presidential campaign, his “America First” platform, and his ultimate election.

Significant qualitative differences also emerged in how Latinx and non-Latinx immigrants were framed as workers. While Latinx immigrants’ contributions to the economy often emphasized their willingness to perform labor Americans deem too lowly or hazardous, non-Latinx immigrants’ contributions were often framed in terms of the special skill and education they offer high-tech industries. The following passage about undocumented immigrants doing the dangerous work of fighting forest fires in the Pacific Northwest is a good illustration of the way the labor of Latinx workers was framed: “Other forestry workers say firefighting jobs may simply be too important—and too hard to fill—to allow for a crackdown on illegal workers” (Johnson Reference Johnson2006). The work is “too important” (to Americans), the article suggested, to punish undocumented workers who are willing to do it. Another article reported on the strategies officials in American cities used to attract Latinx immigrants to fill labor shortages, again implying this group is valued largely for its labor contributions. One article referred specifically to recruitment efforts targeting immigrants “from Mexico, El Salvador and Puerto Rico for landscaping and welding jobs that started at $10 to $12 an hour” (Schmitt Reference Schmitt2001). In contrast to this type of portrayal in the Latinx articles, articles often portrayed non-Latinx immigrants as professional, highly-skilled workers. For example, in reference to family reunification immigration policy, an article focusing on the contributions of mainly high-skilled immigrants suggested, “It’s mostly Asian, Indian, Chinese people who are coming to do mid- and high-level professional jobs” (Appelbaum Reference Appelbaum2017). It went on to assert, “Economists say that skilled immigrant workers are clearly good for the American economy. The United States could import computers; if it instead imports computer engineers, the money they earn is taxed and spent in the United States.”

Articles also framed the economic contributions of Latinx immigrants through descriptions of the negative impact restrictive immigration legislation has on American businesses, something not noted among the non-Latinx pieces. For example, the article titled “Immigrant Crackdown Upends a Slaughterhouse’s Work Force” (Greenhouse Reference Greenhouse2007) describes how the North Carolina hog industry had been adversely affected by immigration raids, asserting, “1,100 Hispanic workers have left the 5,200-employee hog-butchering plant, the world’s largest, leaving it struggling to find, train, and keep replacements.” Another article explained that a town in New Jersey was rethinking its legislation against “illegal immigrants” given their importance to the local economy. The article reported that after passing restrictive legislation, “Within months, hundreds, if not thousands, of recent immigrants from Brazil and other Latin American countries had fled” and then went on to suggest, “With the departure of so many people, the local economy suffered. Hair salons, restaurants, and corner shops that catered to the immigrants saw business plummet” (Belson and Capuzzo, Reference Belson and Capuzzo2007). While we classified these articles as mostly positive because they advocate against restrictive legislation, they focused almost exclusively on how these policies negatively affected local businesses, rather than the immigrants themselves. The underlying message was that restrictive immigration policies should be reconsidered because they harm Americans and American businesses. As others have noted, emphasizing the adverse effects of restrictive legislation on the dominant group contributes to inequality by privileging their well-being over that of a marginalized group (Estrada et al., Reference Estrada, Ebert and Lore2016).

An entirely different frame related to the economy focused on achievement and, once again, stark contrasts emerged between immigrant groups. Economic framing of non-Latinx immigrants often valorized their individual achievements and emphasized upward mobility. This appeared in almost 16% of the frames found within the non-Latinx articles but appeared in less than 1% of the Latinx frames (Table 1). An example of this is an article that described the entrepreneurship of a Burmese refugee. The article reported, “Over two years, Mr. Aung, who never finished high school and is still working on his English, went from running one grocery-store sushi counter to three. Along the way, he saved enough for a $700,000 house and trained 10 fellow Burmese to follow in his footsteps” (Jordan Reference Jordan2017). The article goes on to quote Mr. Aung as saying, “‘I came true with my American dream.’” Another article described the successful gubernatorial campaign of Bobby Jindal and emphasized his family’s Indian American roots. The article, describing his acceptance speech, reported, “The message could not have been clearer: I’m one of you, a normal, red-blooded football-loving Louisiana guy” (Nossiter Reference Nossiter2007).

While both the economic contribution and achievement-oriented frames are ostensibly positive, their implications—especially for America’s racial hierarchy—are quite different. Passages that described Latinx immigrants as consumers and hard workers advocate for their inclusion based on their “good market citizenship” (Deckard and Browne, Reference Deckard and Browne2015) or their image as a “good immigrant worker” (Kibria et al., Reference Kibria, O’Leary and Bowman2018), suggesting they are like Americans in important ways. Indeed, immigrant rights advocates often use similar frames in their appeals for more inclusive immigration policies (Cabaniss and Gardner, Reference Cabaniss and Gardner2020; Patler Reference Patler2017). While this frame may convey “Americanness,” it also (re)creates Latinx immigrants as racialized, neoliberal objects. Within these frames, Latinx immigrants are treated as worker-consumers, physical “things,” that are important vis-à-vis their contribution to the economy. This deprives Latinx immigrants of subjectivity and reduces them to little more than cogs in the capitalist machine. These kinds of frames, when repeated over and over, are especially consequential in today’s neoliberal regime where a person’s value is largely determined by their economic contribution to society (Gazso and McDaniel, Reference Gazso and McDaniel2010; Lavee and Offer, Reference Lavee and Offer2012).

The implications of these frames become even clearer when contrasted with the economic framing of non-Latinx immigrants. By highlighting their individual successes, they are treated as whole, complete persons whose dignity through work is recognized. This difference in portrayal is an example of implicit “relative valorization” (Kim Reference Kim1999) in which non-Latinx immigrant groups are praised for their achievement and upward mobility, while Latinx immigrant groups are recognized for their place within a neoliberal, capitalist economy. Although a positive frame, Latinx immigrants’ worthiness for inclusion is tied to their service to the U.S. economy via their purchases and labor. In this way, the frame subtly reinforces boundaries between Latinx immigrants and other groups.

When articles consistently describe the labor Latinx immigrants perform as something Americans are unwilling to do, especially when the labor contributions of non-Latinx immigrants are glorified, these frames also create a racialized stigma around the work Latinx immigrants perform (Heyman Reference Heyman1998). This characterization suggests that Americans are fundamentally different from Latinx immigrants and that their status is so much higher that they cannot or will not demean themselves by doing society’s “dirty work,” or occupations and tasks that the public perceives as degrading, messy, or otherwise repellent (Hughes Reference Hughes1962). When news articles repeatedly depict Latinx immigrants as all too eager to do this kind of work, the stigma attached to these jobs becomes associated with Latinx immigrants themselves (Waldinger and Lichter, Reference Waldinger and Lichter2003). When they are portrayed in this way far more often than other immigrant groups (who also do menial jobs), it contributes to Latinx immigrants’ racialization as the nation’s dirty workers. This seemingly positive framing thus reinforces the nation’s racial hierarchy by affording citizens (especially White Americans) more dignity and status as workers than Latinx immigrants.

Blameless Victims and Victim-Blaming

Vulnerability emerged as a prominent theme in our data, for both Latinx and non-Latinx immigrants. However, once again, clear distinctions between the two groups emerged. While Latinx and non-Latinx framing alike emphasized the adverse effects of America’s immigration system (i.e., bureaucratic mazes, detention system, court hearings, etc.) on immigrants (“vulnerability-system”), this framing focused almost exclusively on harsh enforcement practices among the Latinx articles. An additional distinction between the two groups emerged related to a different type of vulnerability: the adversity immigrants experience while undertaking the migration journey itself (“vulnerability-migration”). While this frame was completely absent among the non-Latinx framing, it comprised 16.21% of all Latinx framing (Table 1).

A notable longitudinal pattern emerged for the vulnerability-migration frame in the Latinx articles: Approximately 96% of instances of this frame appeared between 2001 and 2003. This may reflect increased enforcement efforts along the U.S.-Mexico border, which began in the mid-1990s under President Clinton and continued into the early 2000s under President Bush. Indeed, many articles pointed to increased border patrols as the reason border-crossings have become more precarious. For example, an article describing the deaths of fourteen young Mexican immigrants in Arizona reported that, “Federal policies to stanch the flow of illegal immigrants near urban areas… had led to such deaths by pushing the illegal border crossers to more and more remote areas” (Sterngold Reference Sterngold2001). Another article asserted, “To avoid the stepped-up border patrols in populated areas, the most desperate migrants cross in the more unguarded and desolate deserts of Arizona and eastern California” (Nieves Reference Nieves2002).

Many of the vulnerability-migration frames highlighted the role of smugglers. Articles routinely described them as cunning and immoral, only concerned with making a profit at the expense of poor, desperate immigrants. An article about increased enforcement efforts noted, “The shift has also made expensive smugglers… indispensable…. Possibly hundreds of migrants have died because they have been abandoned by these smugglers” (Nieves Reference Nieves2002). Another article noted the increased use of cell phone technology by smugglers, who, according to veteran Border Patrol agents, “are constantly innovating to elude the authorities” (Lacey Reference Lacey2011). A piece about parents who hire smugglers to accompany their children across the border quoted an Immigration and Customs Enforcement official: “These are not Robin Hoods who are interested in helping families…. They are cold-blooded capitalists. The smugglers have seen children as the next important exploitable population” (Thompson Reference Thompson2003).

Articles that included the vulnerability-migration frames also frequently implied migrants themselves were responsible for their vulnerability. In the article about parents who contract with smugglers, the writer noted, “American officials warn that immigrant parents are leaving themselves and their children vulnerable to smugglers’ abuses” (Thompson Reference Thompson2003). Other articles asserted that “crossing the border illegally has always come with risks” (Nieves Reference Nieves2002) and referred to migration as a “death-defying gamble” (Fountain and Yardley, Reference Fountain and Yardley2002). Passages such as these suggest that immigrants (especially parents) know it is dangerous to cross the border, yet choose to do so anyway, putting themselves and their children at risk.

The vulnerability-migration frame found exclusively in the Latinx articles is in stark contrast to the vulnerability-system frame, which was presented differently depending on the group that was the focus of the article. For non-Latinx immigrants, articles emphasized the injustices they experienced as they interact with U.S. immigration authorities and related social systems. Some articles, for instance, reported on immigrants dying in detention facilities. An article titled “Immigrant Detainee Dies, and a Life is Buried, Too” asserted, “The difficulty of confirming the very existence of the dead man, Ahmad Tanveer, 43, a Pakistani New Yorker, shows how death can fall between the cracks in immigration detention” (Bernstein and Williams, Reference Bernstein and Williams2009). Other articles about non-Latinx immigrants focused on institutional barriers that left them behind. For example, in describing the inability of the public school system to address the needs of Liberian immigrant children who have never experienced formal education, a professor suggested, “This is the very literal definition of slipping through the cracks” (Medina Reference Medina2009). These kinds of articles suggest non-Latinx immigrants were made vulnerable through no fault of their own.

Especially after 2016, articles focusing on Latinx immigrant also made frequent reference to the vulnerability they experience in the immigration system but focused almost exclusively on harsh enforcement efforts as a result of the Trump administration’s policy changes. For example, an article titled “As Arrests Surge, Immigrants Fear Even Driving” reported that when Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) is spotted in an Atlanta neighborhood, “It takes less than 15 minutes for everyone in the complex to hear about ‘la migra,’ whereupon they shut their doors and hold their breath. Some show up late to work, and others skip it altogether. The school bus might leave some children behind” (Yee Reference Yee2017) and then noted, “President Trump has declared anyone living in the country illegally a target for arrest and deportation, driving up the number of immigration arrests by more than 40 percent this year.” While this portrayal of Latinx immigrants is sympathetic, the article frequently references “illegality”—something completely lacking in the framing of non-Latinx immigrants as vulnerable.

Frames that focus on vulnerability invoke sympathy by centering migrants’ emotional or physical pain. However, differences in how this frame was developed and used with Latinx and non-Latinx immigrants contribute to racialization by implicitly blaming Latinx immigrants for their own suffering. While the reader may feel sympathy for the vulnerable Latinx immigrant who undertakes an arduous journey through the desert to reach the United States, the articles gave readers little to no context for understanding why immigrants embark on such precarious journeys in the first place. Instead, articles described over and over the tragic consequences of Latinx immigrants’ decisions to take such a “risky” journey. Without the broader economic and political context, Latinx migrants’ personal choices become the only explanation for their troubles, and they are subtly racialized as reckless decision-makers.

This victim-blaming of Latinx immigrants becomes even more evident by considering how vulnerability was framed in the non-Latinx pieces. Articles prominently featured the struggles and failures of non-Latinx immigrants to navigate the nation’s maze of immigration policies and procedures. Non-Latinx immigrants were portrayed as having become trapped in a system that does not make sense and that anyone would see as unfair. In contrast, Latinx immigrants’ struggles were framed primarily around their entry to the country but not around what happens later, as they, too, run head-first into the same brutal immigration industrial complex. Latinx immigrant youth are just as likely to fall behind, drop-out, or otherwise “slip through the cracks” of an educational system that is not designed to address their particular needs. Yet, very few of the articles about the vulnerability of Latinx immigrants highlighted these kinds of routine, daily encounters with unreceptive and sometimes negligent U.S. social systems. This almost exclusive focus on Latinx immigrants’ vulnerability while crossing the border (but not while attempting to navigate the onerous immigration system) also reinforces negative stereotypes of this group as invaders who knowingly flout U.S. laws to enter the country illegally.

Latinx Immigrants are “Illegal”

One of the most prominent differences in coverage between Latinx and non-Latinx immigrants centered on references to illegality. We are referring specifically to use of the word “illegal” and its variants (e.g., illegally), as opposed to words like “undocumented” or “unauthorized.” Language matters; surveys find that Americans respond more favorably to the term “undocumented” than “illegal” (Barreto et al., Reference Barreto, Manzano and Segura2012; see also Haynes et al., Reference Haynes, Merolla and Ramakrishnan2016). Among the Latinx-focused articles, there were 282 references to “illegal,” which comprised 28.75% of all frames coded within these Latinx articles. In non-Latinx focused articles, journalists used “illegal” only forty-six times (11.44% of non-Latinx frames) (see Table 1). While references to Latinx immigrants as illegal were consistent across time, we noted an increase in references around 2006 that spiked in 2007. Again, it was during this period that contentious debates around immigration reform were taking place in the streets, in media, and in Congress (Voss and Bloemraad, Reference Voss and Bloemraad2011).

To better understand the “illegal” frame, we performed a supplementary analysis of the titles of the articles in our dataset. Eighteen out of fifty Latinx articles (38%) used illegality in the headline. Examples include “Church Group Provides Oasis for Illegal Migrants to U.S.” (Goodstein Reference Goodstein2001) and “Hospital Falters as Refuge for Illegal Immigrants” (Sack and Almanzar, Reference Sack and Almanzar2009). In contrast, the non-Latinx article headlines were completely void of references to “illegal.” In fact, the single reference to legal status in the title of non-Latinx articles used the word “undocumented” in an article about a South Korean immigrant: “Undocumented Life Is a Hurdle as Immigrants Seek a Reprieve” (Semple Reference Semple2012).

Many of the Latinx articles used “illegal” in reference to border crossings. For example, an article titled “Illegal Immigrant Death Rises Sharply in Barren Areas” (Nieves Reference Nieves2002) provides a vivid description of immigrants who perished while trying to enter the United States through the desert. While the article itself portrayed the immigrants sympathetically, it also made clear that their migration was “illegal,” emphasizing the unlawful actions of the people who died. Articles also used the term “illegal” to describe the economic contributions of Latinx immigrants. An article titled “Illegal Immigrants Are Bolstering Social Security with Billions” (Porter Reference Porter2005) reported, “While it has been evident for years that illegal immigrants pay a variety of taxes, the extent of their contributions to Social Security is striking.”

The pervasiveness of references to Latinx “illegal immigrants”—especially given that the pattern emerged in ostensibly positive articles—casts a definitive shadow over the positive framing discussed in the previous sections and is an important part of the racialization process. While readers may feel sympathy toward Latinx immigrants who suffer while trying to enter the country, they are, in the end, undertaking these journeys “illegally.” And, while this group may bolster the economy as workers, taxpayers, and consumers, they are, again, still “illegal.”

In April 2013, the Associated Press (AP) changed its style guide to advise journalists and editors to use the word “illegal” only to describe actions (i.e., immigrating illegally) but not people (i.e., illegal immigrant) (Colford Reference Colford2013). In keeping with this advice, we expected the NYT to stop using the expression “illegal immigrant(s).” Indeed, journalists never used these terms to describe non-Latinx immigrants after 2013; however, they continued using them in five articles about Latinx immigrants in our dataset.

The finding that journalists persisted in using “illegal immigrant(s)” only in articles about Latinx immigrants after 2013 may reflect how different immigrant groups arrive. Latinx immigrants, after all, are more likely than immigrants from Europe, Asia, or Africa to enter the country “illegally” by crossing a border (but not more so than those from Canada). However, border-crossing is not the only way one becomes “illegal.” Many immigrants, including those from Latin America, fall out of legal status by overstaying or otherwise violating the terms of a visa. The selective description of Latinx immigrants as “illegal immigrants” contributes to their association with crime. As we mentioned earlier, articles that describe the difficulties non-Latinx immigrants face when navigating the immigration system are often about experiences that could be labeled “illegal” but are not, implying their immigration violations are somehow different and less criminal than those of Latinx immigrants. The fact that the NYT continued to use these derogatory expressions exclusively to describe Latinx immigrants, but never in reference to non-Latinx immigrants after 2013 vividly illustrates how seemingly race-neutral language, when applied selectively to one group, can have the effect of racializing that group.

Since the founding of the United States, policymakers have used explicitly racist ideologies in deciding who should or should not be included in the national fold and in doing so, racially constructed the category of “illegal immigrant” (Chomsky Reference Chomsky2014; Coutin and Chock, Reference Coutin and Chock1997; De Genova Reference Genova and Nicholas2004; Ngai Reference Ngai2004). For decades, Asian immigrants were deemed “unassimilable” by lawmakers and were, consequently, barred from becoming U.S. citizens (Chomsky Reference Chomsky2014; Lee Reference Lee2007; Ngai Reference Ngai2004). By linking today’s Latinx immigrants with illegality, media reinforces an insidious practice that legal scholars call crimmigration, or the merging of civil immigration litigation with criminal codes, a trend that has increased in recent years (Stumpf Reference Stumpf2006). Much of this shift has been undergirded by the idea that unauthorized Latinx immigrants are inherently “criminal” (García Hernández Reference Hernández and Cuahtémoc2014).

(Good) Immigrants Adhere to American Values

While our analysis suggests several significant differences in the portrayals of Latinx and non-Latinx immigrants, a singular similarity emerged. Regardless of nationality, articles framed immigrants positively based on their (apparent) adherence to core American values, specifically a commitment to family and traditional gender norms. This frame appeared in 13.97% of all Latinx immigrant frames and 16.17% of non-Latinx immigrant frames, a difference that was not statistically significant (Table 1). There was no discernible longitudinal pattern in the use of this frame.Footnote 3

Articles that framed male immigrants sympathetically often focused on their efforts to provide financially and serve as leaders and protectors for their families. We see this in an article focused on a community’s efforts to provide financial support for a young Mexican man’s wife and children while he underwent treatment for kidney failure. The article reports, “He was a waiter in his early 30s, a husband and father of two, so well liked at the Manhattan restaurant where he had worked for a decade that everyone from the customers to the dishwasher was donating money to help his family” (Bernstein Reference Bernstein2011). It continued, highlighting his enduring commitment to providing for his family members, “‘My boss, she tried to help me,’ said the waiter, who supported his mother and half-siblings from the age of 16 and worked his way up from busboy, paying taxes, mastering English and learning enough French to counsel diners on the wine list” (Berstein Reference Bernstein2011). The article frames him sympathetically by emphasizing both his work ethic and his status as his family’s breadwinner—a role that his illness was preventing him from fulfilling.

Similarly, articles that portrayed immigrant women positively often depicted them as devoted mothers, wives, and caregivers. For example, the following passage portrays immigration raids as unfairly targeting a Honduran immigrant woman, a good mother whose U.S.-born children were suffering emotionally without her. A teacher at her son’s school is quoted as saying, “He is refusing to eat and needs to be coaxed to take sustenance…. He asks for his mother repeatedly” (Preston Reference Preston2007).” Passages such as these humanize immigrants by showing loving attachments; they also counter pervasive stereotypes of immigrants as subhuman criminal invaders to be feared and protected against (Bloch Reference Bloch2014; Chavez Reference Chavez2013; Romero Reference Romero2011).

Considering the notable differences in coverage of Latinx and non-Latinx immigrants identified in our analysis, the fact that positive articles framed individuals from both groups as family-loving and embracing traditional gender norms is interesting. By highlighting their devotion to their families and casting them in familiar and sympathetic roles, this narrative appears to engage in a type of “citizenship framing” that centers on themes of belonging and civic engagement (Patler Reference Patler2017). However, this framing also contributes to racialization by uplifting a specific set of traditional American values and ideals that have historically been associated with and exalted by class-privileged Whites and treating them as the standard by which immigrants should be assessed (Feagin and Cobas, Reference Feagin and Cobas2008).

This framing also exemplifies the colorblind frames of cultural racism and abstract liberalism. News articles portray immigrants who conform to these narrowly defined “American” values as deserving of sympathy, which suggests that other immigrants are undeserving—not because of their race or ethnicity, but because they choose not to embrace these same values. Thus, in this framing, we see an implicit distinction being made between “good/deserving” immigrants and “bad/undeserving” ones (Marrow Reference Marrow2012; Yoo Reference Yoo2008). This is akin to the “model movement strategy” described by Grace Yukich (Reference Yukich2013), where social movement organizations selectively choose which actors to use as spokespersons to counter the negative stereotypes associated with the group. Parallel to the frame presented here, immigrants lifted up by the NYT as deserving were those who adhered to dominant cultural values—or at least could be portrayed in that way.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

By examining how The New York Times contributes to the racialized social representations of Latinx immigrants while using seemingly positive, race-neutral language, our research offers insight into the subtle ways race and racism continue to operate in contemporary society. We found that even newspaper articles that appear to advocate on behalf of Latinx immigrants contribute to their racialization, especially when compared to articles about non-Latinx immigrants. Unlike its portrayal of other groups, the NYT’s positive depictions of Latinx immigrants often presented them as economically exploitable, vulnerable in ways that subtly blame the victim, and as mostly illegal. We also found that positive newspaper articles frequently depicted immigrants of all nationalities as devoted to their families and highlighted their commitment to traditional gender roles. However, we argue that this depiction reinforces a hierarchy based on notions of deservingness and conformity to White middle-class ideals (Feagin and Cobas, Reference Feagin and Cobas2008). Our analysis, thus, shows that the racialization of Latinx immigrants not only transpires through openly xenophobic newspaper discourse, but also through (seemingly) sympathetic rhetoric. There are several implications of these findings.

First, our research demonstrates how colorblind ideology operates through frames that appear to be supportive. Bonilla-Silva’s (Reference Bonilla-Silva2017) original work focused on more negative, race-neutral narratives. For example, the cultural racism frame he outlined suggests that the reason Whites fare better in terms of income, education, and wealth is because ethnoracial minority groups have the “wrong” culture. While this frame is race-neutral, in that it does not fault racial minority groups explicitly, it explains their disadvantages by pointing to cultural deficiencies. In contrast, the colorblind frames we highlighted are largely positive. By examining how members of society use colorblind discourse to not only demean ethnoracial minority immigrants but also to uplift them, our research illustrates the flexibility of racial ideologies to bolster existing racial hierarchies. More specifically, we show how the use of ostensibly positive colorblind rhetoric, like its negative counterpart, obscures the racialized dimensions of some of our most contentious and divisive social issues, a complication that makes solving them all the more difficult.

Our research also highlights the gatekeeping powers of the elite media, as journalists and editors create images of “acceptability” for Latinx immigrants and determine whether they measure up. We found that articles generally upheld an assimilationist model that lauded adherence to White middle-class values and promoted “model immigrant” stereotypes (Yukich Reference Yukich2013). Immigrants who demonstrated commitments to their families, to traditional gender roles, and to working hard without complaint were frequently featured in the articles we analyzed. At the same time, we found that sympathetic portrayals often simultaneously depicted this group as not like “us” in meaningful ways. As objects who benefit American companies or communities, as workers eager to fill unsavory jobs “real” Americans shrink from, as victims whose own decisions may have contributed to their plight, Latinx immigrants were repeatedly constructed by the NYT as different from Americans. On the surface, these depictions—as simultaneously like us and unlike us—seem contradictory. In fact, they follow a consistent and familiar pattern set by powerful elites who put less powerful groups in double binds by holding them to impossible standards (Kleinman and Cabaniss Reference Kleinman, Cabaniss and Jacobsen2019). The “model minority” myth, for instance, suggests that immigrants who act in ways that are pleasing to the dominant group will be accepted and integrated fully into American society (Chou and Feagin, Reference Chou and Feagin2015). When the United States was attacked by Japan in World War II, however, the U.S. government justified the internment of over 100,000 Japanese Americans by portraying them as disloyal, potential saboteurs who, by virtue of their racial heritage alone, were presumed to be enemy sympathizers unworthy of the rights and protections granted to other Americans. In an instant, Japanese Americans moved from being “us” to being “them.” The seemingly contradictory portrayals of acceptable Latinx immigrants in the NYT similarly repeat this pattern of elites setting high, often inconsistent, standards for a subordinated group and ultimately deciding if, when, and how they meet them.

Our work also has implications for understanding the intersections of race and origin of birth. The racialized boundaries around Latinx immigrants—and the Latinx community more broadly—are so entrenched that even discourse that is sympathetic can brighten the lines between “us” and “them.” That is, even discourse that appears to advocate for this group’s inclusion does so in only a limited sense. This contingent acceptance may reflect how Latinx groups were initially incorporated into the United States as colonized persons (Blauner Reference Blauner and Takaki1987) and the perceived legitimacy of boundaries between immigrants and nonimmigrants in a racially divided society. This legitimacy stems from an underlying assumption of the nation-state system that those included have something in common (i.e., work ethic, religion, or family values), distinguishing them from those excluded (Verdery Reference Verdery, Hans and Cora1994). This perceived legitimacy, coupled with America’s existing racial hierarchy of White supremacy, helps us understand how laudatory discourses about Latinx immigrants create “outsiders within.”

Our project suggests several opportunities for future research. We focused on positive, race-neutral discourse about Latinx immigrants in one elite newspaper, but it is equally important to examine the use of similar rhetoric in other news outlets. Researchers have already uncovered meaningful differences in negative discourse between outlets (Browne et al., Reference Browne, Deckard and Rodriguez2016); we would expect to find similar patterns with positive discourse. Future research may also uncover significant changes over time. Although we noted some shifts in our data during the nineteen-year span of our analysis, a more substantial longitudinal investigation over a longer period might yield a much fuller understanding of how the racialization of Latinx immigrants unfolds over time. For example, more recent NYT coverage of Latinx immigrants from Central America appears to provide more context for their border-crossing, noting, for instance, that many families are fleeing violence and persecution and are seeking asylum. This is in stark contrast to how border-crossings were decontextualized and emphasized “illegality” during the period of our study. A comparative analysis of past and current coverage could help identify when and how discursive practices related to racialization shift. Future research should also examine readers’ responses to the articles we analyzed and the social consequences of these frames. While media framing plays a significant role in shaping how people view and come to understand certain issues, audiences also contribute to this knowledge-building process (Gamson et al., Reference Gamson, Croteau, Hoynes and Sasson1992).

Finally, our work suggests that people who consider themselves to be allies to Latinx immigrants should think critically about their advocacy narratives. Michael Schwalbe and colleagues (Reference Schwalbe, Godwin, Holen, Schrock, Thompson and Wolkomir2000) argue that one way dominant groups maintain their dominance is by controlling the discourse, or ways of talking and writing, about less powerful groups. If those interested in creating a more inclusive social and political environment for immigrants use the language of powerful elites, they may inadvertently reinforce the very marginalization they are fighting against.