Published online by Cambridge University Press: 09 October 2006

Since linguistic and anthropological study of sign languages began in the 1960s, most research has focused on national sign languages, with scant attention paid to indigenous and original sign languages. Vulnerable to extinction, the latter varieties can expand our understanding of language universals, language typologies, historical comparative linguistics, and other areas. Using Thailand as a case study and drawing on three examples – a rare phonological form, basic color terminology, and baby talk/motherese – from Ban Khor Sign Language, an indigenous signed code, this article describes the problem of benign neglect of sign languages in current discussions of language endangerment and argues for the importance of expanding such discussions to include codes expressed in the manual-visual channel.The linguistic field research upon which this article is based was funded by the Endangered Language Fund, the Explorers Club, IIE Fulbright, Sign Language Research Inc., the Thai-U.S. Educational Foundation, the UCLA Department of Anthropology, the UCLA Office of International Studies and Overseas Programs, the UCLA Wagatsuma Memorial Fund, and the Wenner-Gren Foundation. I wish to thank the following individuals and groups for their assistance in various phases of the project: Alexis Altounian, Poonpit Amatyakul, Jean Ann, Wendy Belcher, Ursula Bellugi, Steve Bickler, Ken Kamler, Peter Ladefoged, Tuanvu Le, Chettah Madminggao, Nutjaree Madminggao, Marina McIntire, Carmella Moore, Pam Munro, Carol Padden, Diana Pash, Nilawan Pitipat, Claire Ramsey, Chip Reilly, Olga Solomon, Kelly Stack, Laura Sterponi, Viphavee Vongpumivitch, and Akira Yamamoto. Special thanks belong to Vien Champa, Lahsee Khammee, Jintala Anuyahong, Anucha Ratanasint, Khwanta Sukhwan, Nipha Sukhwan, Phaiwan Sukhwan, Kampol Suwanarat, Thanu Wongchai, James C. Woodward, the Ratchasuda Foundation, the National Association of the Deaf in Thailand, and, of course, the community of Ban Khor.

Sign languages have been used by speech communities1

Akira Yamamoto pointed out that the very term “speech community” (vs. sign community) reflects a language ideology that is orally rather than manually centered. This critique notwithstanding, since “speech community” is so widely accepted and pervasively used in various academic circles, I have elected to use the term here.

In this article the terms “code” and “language” are used synonymously and interchangeably. “Code” is utilized in this way for two purposes: to provide readers relief from repetitive use of the word “language” throughout the paper, but more importantly, to underscore the distinction between “code” vs. “channel,” or “language” vs. “modality.” This strategic use of “code,” while accepted by many scholars, raises concerns for others who object on the grounds that it hearkens back a time when sign languages were not recognized as languages or were viewed as inferior to spoken languages. Those who dislike use of the term “code” argue that it risks confusing or conflating the distinction between, for example, American Sign Language (which has a grammar distinct from English) and Signed English (which follows the syntax of English). I acknowledge these concerns but draw a different conclusion regarding the advantages and disadvantages of using the term “code.”

Therefore, throughout this article “code” and “language” are used synonymously: the Japanese language = the code of Japanese. Code/language is distinguished from channel/modality (e.g., written, oral-aural, manual-visual, manual-tactile). From this distinction, it follows that while American English is a language usually expressed in the written or oral channels, it can be manually coded and expressed on the hands; the result is manually coded English, or what is often referred to as Signed English. Yet American Sign Language and Signed English are different languages. Finally, in this article all codes (Thai, Thai Sign Language, Nyoh, Ban Khor Sign Language) – signed or spoken – are understood to be full and complete but distinct languages that stand in equal, not inferior, relationships to one another.

In addition to national sign languages, there are numerous indigenous and original sign languages (see below). Far less is known about the latter language varieties – most of which are completely undescribed, and many of which are highly endangered. This dearth of information about indigenous and original sign language varieties is regrettable, because it is often such languages that preserve unique or less common linguistic features, reflect the true linguistic diversity associated with natural human sign languages, and thereby enrich our understanding of universal grammar and linguistic typology. Moreover, indigenous and original sign language varieties represent crucial pieces in the puzzle of constructing “sign language families” (Woodward 1993, Zeshan 2003), an endeavor that in turn promises to expand the field of historical-comparative linguistics.

This article has two primary aims. The first is to focus attention on the problem of benign neglect of sign languages, especially indigenous and original sign languages, which have been largely forgotten in most discussions of language endangerment. The second goal is to demonstrate the importance of documenting and preserving these codes by presenting examples – a rare phonological form, basic color terminology, and baby talk/motherese – of what is at stake, and what might be learned from study or lost through neglect of an endangered indigenous sign language in Thailand.

Toward these two ends, I begin by addressing the questions of why benign neglect of sign languages occurs and how it contributes to the problem of language endangerment. Then, building directly on a new model (Woodward 2000) of sign language typologies in Southeast Asia, I outline what is currently known about sign languages, linguistic diversity, and sign language endangerment in Thailand. Finally, drawing on original anthropological linguistic data from Ban Khor Sign Language, I demonstrate some of the contributions that endangered sign languages promise to make to our collective knowledge of linguistics and anthropology.

Outlined in broad theoretical terms and described in detailed case studies, the phenomenon known variously as “language shift” (Kulick 1992), “language obsolescence” (Dorian 1989), “language death” (Dressler & Wodak-Leodolter 1977, Dorian 1981, Sasse 1990, Brenzinger 1992, Broderick 1999, Crystal 2000), or “language extinction” (Nettle & Romaine 2000), is a rapidly escalating problem – one that has gained the attention and concern of organizations ranging from the Linguistic Society of America to the United Nations. Although there is debate (Hale et al. 1992; Ladefoged 1992; Dorian 1993, 2002; England 2002; Fishman 2002; Hill 2002; Hinton 2002; Silverstein 2003) about how best to conceptualize the problem (e.g., as a threat to biocultural diversity, or as a natural process) and consequently how best to respond to the phenomenon of disappearing languages (e.g., with intervention motivated by humanitarian concerns, or with non-intervention motivated by strict scientific observation), there is widespread consensus about the importance of documenting existing linguistic diversity. Furthermore, there is widespread agreement that particular attention and effort should be directed toward documenting and describing endangered languages.

For example, the Linguistic Society of America Committee on Endangered Languages has published a policy statement on “The need for the documentation of linguistic diversity” (1994), which points out that the study of universal grammar and linguistic typology is greatly enriched by the documentation of linguistic diversity, especially the documentation of languages on the geographical and linguistic “fringe” (LSA 1994). The policy statement recommends support for “the documentation and analysis of the full diversity of the languages which survive in the world today, with highest priority given to the many languages which are closest to becoming extinct, and also to the many languages which represent the greatest diversity” (e.g., language isolates and languages belonging to undocumented or underdocumented language families) (LSA 1994:181–82).

Despite growing awareness and concern about the problem of diminishing linguistic diversity, many sign languages – and the speech communities associated with them – have been overlooked, ignored, or forgotten. At-risk sign languages are threatened for the same complex reasons (demographic, political, economic, social, educational, etc.) that many spoken languages are threatened.3

In addition to the demographic, political, economic, social, and educational factors that threaten many languages (manual-visual and spoken), sign languages also are threatened by negative language ideologies. Although sign languages are acknowledged as languages by linguists and anthropologists, sign languages (and Deaf people) are often pathologized or stigmatized by other professions and by the general public. Given the sociolinguistic power imbalances, it might well be argued that sign languages, as a class of languages, are more endangered than spoken languages.

Sign languages existed long before there was any formal academic recognition of the full linguistic status of codes expressed in the manual-visual channel. Even among linguists, recognition of signed codes as human languages on par with spoken codes is a recent development. The paradigmatic shift in understanding of sign languages began in 1960, when William Stokoe, the father of sign language linguistics, published Sign language structure (Stokoe 1960, revised edition 1978).4

Originally published as Sign language structure: An outline of the visual communication system of the American deaf (Department of Anthropology and Linguistics, University of Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, 1960), Stokoe's theoretical case for the full linguistic status of sign languages was revised and subsequently published as Sign language structure: The first linguistic analysis of American Sign Language (Silver Spring, MD: Linstok Press, 1978).

Stokoe initially proffered the terms “chereme” and “cherology” to describe phonemes and phonology in sign language. Over time, his explanation for the existence of phonology in signed languages was accepted by linguists, but the terms “chereme” and “cherology” were rejected.

Besides the contribution to linguistics, important sociolinguistic implications resulted from acknowledgment of the full linguistic status of sign languages – in particular, a rethinking of the socially constructed meanings of deafness. Rather than focusing on the audiological condition of hearing loss, which typically corresponds with an emphasis on speech pathology, recognition of the full linguistic status of sign languages redefines Deaf (vs. “deaf”) people as members of linguistic minorities.

Use of lower-case “deaf” and upper-case “Deaf” spellings differentiates between the audiological condition of not hearing and references to a particular group of Deaf people who share a sign language, a community, and a culture. This “big D/little d” distinction was first proposed by James C. Woodward in the context of his pioneering sociolinguistic research on ASL and American Deaf culture.6

Padden & Humphries, in their classic work on U.S. Deaf culture, cite the first use of the deaf/Deaf distinction as: “James C. Woodward, ‘Implications for sociolinguistic research among the Deaf,’ Sign Language Studies Volume 1, 1972, p. 1–17.” This is a citation error. Although the distinction was indeed developed by Woodward, it was first introduced in 1975 in a paper entitled “How you gonna get to heaven if you can't talk with Jesus: The educational establishment vs. the Deaf community.”

The legacy of nonrecognition of sign languages as languages, and of Deaf people as linguistic minorities, is the cause of widespread endangerment of many codes in the manual-visual channel. Whereas documentation and description of spoken languages has been an ongoing effort for centuries, similar work on signed languages began just a few decades ago. The research that has been completed in the past 40 years has been heavily skewed toward study of national sign languages, with little attention paid to indigenous and original varieties.

Like sign language linguistics, Deaf studies – a multidisciplinary, cultural approach to studying Deaf people, their languages, identities, experiences, and so on – originated in and focused heavily on Deaf communities in North America and western Europe. Although Deaf studies research has spread to other parts of the world recently, it must be noted that neither sign language linguistics nor Deaf studies have extensively dialogued with broader ethnic or geo-cultural area studies. Nowhere is the impact of continued marginalization of Deaf people as linguistic minorities more evident than in contemporary discussions of language rights as human rights. This point is elaborated in “Sign languages – How the Deaf (and other sign language users) are deprived of their linguistic human rights” (Skutnabb-Kangas 2002), an article on the Terralingua website (8/9/02), which describes contemporary Deaf Europeans' struggles to have sign languages officially recognized as minority languages and thereby to enjoy the same linguistic human rights as hearing/speaking people.

Delayed linguistic and anthropological recognition of sign languages and Deaf people has resulted in severe underdocumentation of sign languages and Deaf cultures, and continued benign neglect only exacerbates the problem. This point is highlighted in “Diminishing diversity of signed languages,” a letter to the editor of Science magazine by Richard P. Meier (2000:1965), who points out that as yet there has been no thorough survey of the sign languages of the world, that “the very existence of some signed languages is threatened,” and that “many signed languages may disappear before we have the faintest understanding of how much signed languages can vary.” In short, he underscores the importance of remembering to include sign languages when we speak of endangered languages.

I have conceptually outlined the problem of benign neglect of sign languages in the previous section; this section examines a real-world example of the problem in Thailand – a linguistically diverse country poised to become a regional center of sign language linguistic research – where until recently little attention has been paid to codes expressed in the manual-visual channel and where sign language endangerment is a serious problem.7

In the 1990s, at the behest of HRH Princess Mahachakri Sirindhorn, Thailand established Ratchasuda College (Mahidol University at Salaya), the first institution in Southeast Asia – and one of only four worldwide – dedicated to providing tertiary education to deaf students. In addition to its mission to educate Thai deaf students, Ratchasuda College was also envisioned as a regional research and training center for study of sign languages in Thailand and other Southeast Asian countries. Sign language linguistic research in Southeast Asia is slowly but steadily expanding to include other countries such as Vietnam (Woodward 1997, 2000), Myanmar (Owen Wrigley, personal communication, 1999), and Indonesia (Branson & Miller 1996).

An earlier, unpublished version of the present article was presented in January 2002 at the 8th International Thai Studies Conference in Nakhon Phanom, Thailand. It constituted the first discussion of sign languages as endangered languages in Thailand.

This dearth of information about sign languages in Thailand is unfortunate for many reasons. To begin with, we do not know how many sign languages actually exist in the country. Preliminary linguistic survey work (Woodward & Nonaka 1997, Nonaka 2000, Woodward 2000, Nonaka 2001a), conducted first in collaboration with James C. Woodward9

James C. Woodward is the leading figure working on comparative sign language linguistics in Southeast Asia, and his work is frequently cited in this article. I had the privilege to work with “Woody” for two years in the Research Department at Ratchasuda College, Mahidol University, Thailand. Intellectually I am deeply indebted to him, and I appreciate his generosity in sharing the data we collected together.

The seven confirmed sign language varieties known to exist or to have existed in Thailand are Thai Sign Language, Old Bangkok Sign Language, Old Chiangmai Sign Language, Ban Khor Sign Language, plus three more indigenous sign languages identified below in note 15. In addition to the seven confirmed sign languages, there are credible but as yet unconfirmed reports from the National Association of the Deaf in Thailand of other sign languages in other regions of Thailand: in the South as well as in the Chiangmai and Chiangrai areas.

Based on recent research he conducted in Southeast Asia, Woodward (1996, 1997, 2000) has proposed a new tripartite model of sign language varieties. He outlines three general types of sign languages – national, indigenous, and original – all of which can be found in Thailand.11

Although Woodward's theoretical discussion is limited to sign language varieties in Thailand and Southeast Asia, potential applications of the model to other areas of the world seem promising.

Modern Standard Thai Sign Language (MSTSL), often referred to simply as Thai Sign Language (TSL)12

Ethnologue (2001) uses TSQ, rather than TSL, to refer to Thai Sign Language.

HRH Princess Mahachakri Sirindhorn acknowledged TSL as the language of Thai deaf people in an address given to formally open the Nippon-Gallaudet World Deaf Leadership program at Ratchasuda College, Mahidol University at Salaya in summer 1998.

Comparative lexicostatistical analysis has revealed that TSL is a language distinct from but closely related to ASL, and that the two codes belong to the same sign language family (Woodward 1996:245). Upon first consideration, this degree of linguistic relatedness between the two sign languages would seem unlikely for obvious areal-geographic reasons. However, the two codes are indeed related because of language contact and creolization (Woodward 1996:245) that occurred some 50 years ago when ASL was introduced into Thailand by Thai educators at the School for Deaf Children at Dusit District, Bangkok – the forerunner of the institution now known as Sesathien School for the Deaf (Sathaporn 1987:283).

The history of formal deaf education, and the tendency toward pedagogical vacillation between oral and manual philosophies and practices, is a complicated one. Suffice it to say that when ASL was introduced into Thailand – notably, before the emergence of sign language linguistics – it was widely assumed that special education necessitated “giving” deaf people what they supposedly lacked: the ability to communicate. In other words, it was assumed that Thai Deaf people lacked a sign language of their own, or if they did have one, that it was inferior to ASL.14

The founder of deaf education in Thailand, Khunying (Lady) Kamala Krairiksh, and other early educators trained in or borrowed heavily from the USA. For example, the Thai manual alphabet (see note 35) was invented in collaboration with American professors at Gallaudet College during the 1950s. In addition, Deaf adults age 50 and over who were members of the first class at the Dusit deaf school, as well as retired teachers from that institution, recall that early on American Sign Language was introduced wholesale at the school. Later, Thai deaf educators, mirroring trends in American deaf education, began developing initialized signs, a system of Signed Exact Thai, and so on. Much to the consternation of many adult members of the Thai Deaf community, whose native language is Thai Sign Language, ASL continues to exert an influence in deaf schools across the country. As Dr. Maliwan Tammsaeng, the director of Sesathien School for the Deaf, laments: “'I've fought for years to get the Hearing teachers to stop using ASL or making up their own signs for things” (Deshaw 1995).

ASL was not introduced into a sociolinguistic vacuum. In fact, as Woodward 1996 has demonstrated, there were at least two, and perhaps more, original sign language varieties (and probably a number of indigenous sign languages) already present in Thailand prior to the 1950s. It was these local Thai sign language varieties, discussed in more detail below, and their creolization with ASL (Woodward 1996) that gave rise to TSL.

In addition to the national sign language, Thailand is home to a number of indigenous and original sign language varieties. Unfortunately, both types of codes tend to be vulnerable to language endangerment and extinction. Exactly how many indigenous and original sign languages exist or have existed is unknown. However, research demonstrates the presence of at least six such sign language varieties.15

There are six confirmed original or indigenous sign languages in Thailand. Besides Old Bangkok, Old Chiangmai, and Ban Khor Sign Language, I have identified three additional indigenous sign languages found in Nakhon Phanom province: Huay Hai, Plaa Pag, and Na Sai sign languages. I first learned of the existence of those indigenous sign languages through contacts at the Issarn regional chapter of the National Association of the Deaf in Thailand (NADT). Liaisoning with Issarn NADT, I traveled to the three villages and met native deaf signers there. In addition, I had the opportunity to interview deaf people from each of the villages who attended a short-course occupational training program sponsored by Issarn NADT that was held in the provincial capital of Nakhon Phanom. Further research is required, but early observation suggests that Huay Hai, Plaa Pag, and Na Sai sign languages are distinct from one another as well as from Ban Khor Sign Language, Old Bangkok Sign Language, Old Chiangmai Sign Language, and Modern Standard Thai Sign Language.

In contrast to national sign languages, indigenous sign languages typically are restricted in use to small (often agrarian village or island fishing) communities (Kushel 1973, Frishberg 1987, Woodward 1982a, Groce 1985, Johnson 1991, Torigoe, Takei & Kimura 1995, Branson & Miller 1996). The cultural notion of a “big D” Deaf community and Deaf culture – which so frequently corresponds with national sign languages – usually is not found in speech communities associated with indigenous sign languages. In speech communities of the latter type, it is common to find neutral to positive attitudes toward deafness, deaf people, and sign language; widespread fluency in the local sign language among hearing people in the community; and a high degree of integration of deaf people into the mainstream of village society. As mentioned before, indigenous sign languages and the sociolinguistic environments that sustain them are frequently highly endangered.

Pasa kidd or pasa bai, translated ‘language (of the) mute’16

Locally, Ban Khor Sign Language is referred to as either pasa kidd or pasa bai, both of which translate as ‘language (of the) mute’; pasa means ‘language’. Bai is the Thai word for ‘mute’. Kidd, which also means ‘mute’, is a word from Nyoh, the dominant spoken language in the community of Ban Khor.

The Thai-English glossary in the Appendix provides phonetic transcriptions and translations of Thai terms used in this paper. It is important to note that there is no single, accepted system for Thai-English phonetic and tonal transcription. Rather, there are a number of commonly used conventions. Unfortunately, not all the tonal and phonetic markings of a given transcription system are included in the font selections of various computer programs. For this reason, the glossary is divided into four columns: 1) romanized transcription of Thai words as they appear in the text; 2) phonetic and tonal notation; 3) Thai script; and 4) English translations of the Thai words.

I would prefer to use a local term, pasa kidd or pasa bai, to name the sign language used in the community of Ban Khor, but this is not possible because there are other indigenous sign languages also called pasa bai ‘language [of the] mute’ that are used in other Thai villages. For the sake of descriptive precision and clarity I have adopted the name “Ban Khor Sign Language” to refer specifically to the manual-visual code used in that community.

It is widely accepted that 1 per 1,000 individuals will be born profoundly deaf or become deaf at an early age (Schein & Delk 1974).

Original sign languages are the third type of sign language variety found in Thailand. Old Bangkok Sign Language and Old Chiangmai Sign Language (Woodward 1996) are two examples of original sign languages that pre-date the national sign language. Both languages are moribund, remembered (e.g., in formal linguistic elicitation sessions) by a few signers over the age of 45 but no longer utilized in daily conversation. It is difficult to establish with precision when (i.e., time/date estimates) and where (i.e., exact speech community boundaries) these languages developed. However, as to the “why” and “how” of their development, Woodward 1997 has hypothesized that in the case of Thailand, original sign language varieties developed in market towns and urban areas, places where deaf people had opportunities to meet and interact.

From a comparative-historical linguistic perspective, learning more about original sign language varieties in Thailand is an important and increasingly urgent matter. “The development and spread of MSTSL [Modern Standard Thai Sign Language], while providing a nationally unifying force for Thai deaf people, has at the same time endangered original sign languages in Thailand” (Woodward 1996:245). This endangerment is both ironic and unfortunate. It is ironic to the extent that Old Bangkok and Old Chiangmai (and perhaps other) sign languages were the very codes that creolized with ASL to produce TSL. Loss of these original codes is unfortunate for many reasons, but particularly because they are critical “link languages” (Woodward 2000:34) that hold important clues for constructing Asian sign language families (Woodward 1993, 2000).

The preceding section summarized what is currently known about sign languages in Thailand. Regrettably, there is much – too much – that remains unknown about these languages, especially indigenous and original signed codes, most of which are endangered and undocumented. Focusing on three examples – a rare phonological form, basic color terminology, and baby talk/motherese – from Ban Khor Sign Language (the indigenous sign language mentioned earlier), this section demonstrates some potential contributions to linguistics and anthropology that can be derived from study of undescribed, underdescribed, and endangered sign languages.

It must be emphasized that these are preliminary findings. Initial observations, analyses, and claims of significance might be subject to revision at a later date. However, if presentation of the following findings about Ban Khor Sign Language succeeds either in expanding discussion of linguistic diversity in Thailand to include sign languages or in focusing attention on the urgent problem of sign language endangerment, then a contribution has been made.

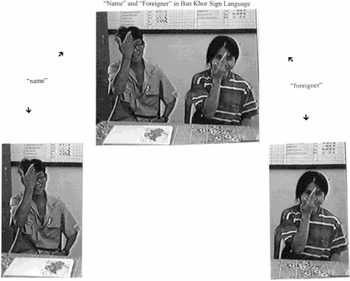

Study of Ban Khor Sign Language promises to expand the known phonological inventory of signed languages. Ban Khor Sign Language includes phonological forms that are rare, if not unique – that is, previously undescribed. For example, consider the lexemes ‘name’ and ‘foreigner’ shown in Figure 1. In the remainder of this subsection, I will examine those two signs to demonstrate how our understanding of sign language phonology might be enhanced from study of indigenous codes like Ban Khor Sign Language.

“Name” and Foreigner” in Ban Khor Sign Language.

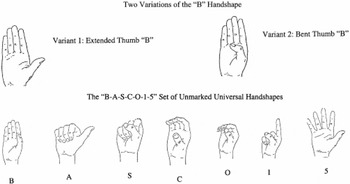

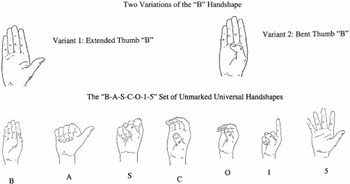

Traditionally, sign language phonology theory has described signs in terms of four parameters: handshape, location, movement, and palm orientation.20

The first three parameters – handshape, location, and movement – were proposed by Stokoe 1960, 1978. The fourth parameter, palm orientation, was proposed subsequently by Battison 1980.

Phonological notation of sign languages is heavily influenced by American Sign Language. Because sign language research began in the United States, many phonological handshapes are described with reference to ASL manual letters or to signs made with the same hand configurations. This notational bias resembles that of the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), which was developed in the nineteenth century by British and French phoneticians and which was based on the Roman and Greek alphabets.

The graphics in Figure 2 originally appeared in The signs of language (1979) and are reprinted here with permission from the original author, Ursula Bellugi of the Salk Institute, La Jolla, California.

Selected hand configurations. (Figures reprinted from The Signs of Language, Klima, Bellugi & Battison et al., 1979.)

With regard to location and movement, the two lexemes are both common and uncommon. They are common to the extent that they are made on the face. Many signs in ASL (Battison 1978), as well as in other sign languages (Nonaka 1997), are made on or near the face. Some scholars (Siple 1978b, Mandel 1981) have even suggested that signs are “built to be ‘seen’” and “shaped by the requirements of the body” (Baker-Shenk & Cokely 1980:80, 82), arguing that prolific articulation of signs in the facial area is directly linked to maximization of visual acuity.

Regardless of whether or not visual acuity bio-evolutionarily determines or drives sign production in the facial area, scholars studying historical-comparative linguistic change in ASL (Battison 1974, 1978; Frishberg 1975, Klima et al. 1979; Woodward 1976, 1978; Woodward & De Santis 1977; Woodward & Erting 1975; Woodward et al. 1976) have identified certain patterns for directional change in sign languages over time. Predictable changes include the following tendencies: (i) two-handed signs become one-handed signs; (ii) compound signs become simplified; (iii) symmetry develops in two-handed signs; (iv) production of signs made below the face/head move toward the midline, from visually peripheral to central locations; and (v) signs made on or at the face to shift to its periphery because of a dispreference for articulation of signs that block the face.23

This claim of dispreference is based on the argument that signs that block the face obscure important non-manual features of the sign language.

Clearly the Ban Khor Sign Language terms ‘name’ and ‘foreigner’ do not conform to pattern (v), the dispreference for articulation of signs that block the face such that signs made on/at the face shift to its periphery. The two signs, especially the word ‘foreigner’, are made directly on the front, central region of the face. Moreover, they do not involve movement but instead remain stationary in that area. This blocking of the face makes the signs phonologically unusual.

The two lexemes, however, are phonologically quite rare, if not “unique,”24

Because this research is in the early phases, I have not yet completed a comprehensive, systematic study of this particular palm orientation compared with all other documented sign languages. However, the assertion that this particular palm orientation is rare is based on a combination of factors: (i) personal discussions and correspondence with sign language linguists in the United States, (ii) interviews with several Thai Deaf native TSL signers, (iii) previous comparative anthropological linguistic research I conducted in Thailand, Japan, and the USA, and (iv) examination of existing resources (e.g. dictionaries and grammars) on Thai Sign Language, Japanese Sign Language, and American Sign Language.

As Valli & Lucas (1992:19) explain, “The term dominant will be used to refer to the hand preferred for most motor tasks, and nondominant will refer to the other hand…. Signers can be characterized as being either left-handed with respect to signing or right-handed with respect to signing. For most signers with right (left) hand dominance, their right (left) hand will assume the active role most of the time.”

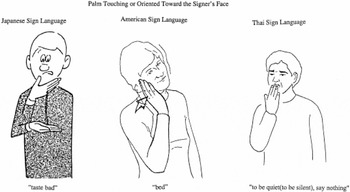

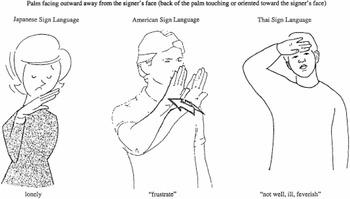

Examples of these three palm orientations appear in Figures 3, 4, and 5 respectively.26

Comparative examples of signs with similar palm orientations in Japanese Sign Language, American Sign Language, and Thai Sign Language were taken from the following sources: An English dictionary of basic Japanese signs (JFD 1991), A basic course in American Sign Language (Humphries et al. 1985), and The Thai Sign Language dictionary (Suwanarat et al. 1990).

“B” handshape palm-orientation #1. (Figures reprinted from An English Dictionary of Japanese Signs, Japanese Federation of the Deaf, 1991; A Basic Course in American Sign Language, Humphries, Padden & O'Rourke, 1985; The Thai Sign Language Dictionary, Suwanarat et al., 1990.)

“B” handshape palm-orientation #2. (Figures reprinted from An English Dictionary of Japanese Signs, Japanese Federation of the Deaf, 1991; A Basic Course in American Sign Language, Humphries, Padden & O'Rourke, 1985; The Thai Sign Language Dictionary, Suwanarat et al., 1990.)

“B” handshape palm-orientation #3. (Figures reprinted from An English Dictionary of Japanese Signs, Japanese Federation of the Deaf, 1991; A Basic Course in American Sign Language, Humphries, Padden & O'Rourke, 1985; The Thai Sign Language Dictionary, Suwanarat et al., 1990.)

Now consider the three preceding examples of known palm orientations of “b” handshape signs with the palm orientation of the Ban Khor Sign Language terms ‘name’ and ‘foreigner’. Articulation of the two Ban Khor Sign Language words involves rotation of the arm 90° from the palm orientation of the signs in Figure 3, 180° from the palm orientation of the signs in Figure 4, and 270° from the palm orientation of the signs in Figure 5. It is important to note that most of the signs in Figures 3, 4, and 5 either are made at “peripheral” areas of the face or involve movement away from or out of the center of the face. By contrast, the two Ban Khor signs remain stationary, produced directly on the front, central region of the face.

Just as clicks in Bantu languages and dental plosives followed by bilabial trills in the Chapakuran languages Wari and Oro Win (Ladefoged & Everett 1996) expanded the known phonological inventory of spoken languages, Ban Khor Sign Language includes unusual phonological forms that promise to broaden our collective knowledge of the phonological inventory of signed languages, and by extension all natural human languages. Interviews with Deaf native users of TSL reveal that the phonological form associated with the lexemes ‘name’ and ‘foreigner’ in Ban Khor Sign Language does not exist in TSL – a fact dramatically underscored by the new TSL sign for the village of Ban Khor, which combines the Ban Khor sign ‘name’ with the TSL sign ‘there/over there’. In addition, the contact point – ulnar side of the hand touching the face – associated with the signs ‘name’ and ‘foreigner’ in Ban Khor Sign Language is also an impossible contact point in ASL, and it would not be predicted to occur in other sign languages based on what is currently known about sign language phonology.27

Marina McIntire noted that it might be possible to argue that the ASL sign ‘schizophrenic’ is made using a palm orientation similar to the one associated with the Ban Khor Sign Language lexemes ‘name’ and ‘foreigner’. However, the contact points differ, with the ASL sign making contact at the fingertips and the Ban Khor signs making contact on the ulnar side of the hand.

Color terminology has long been a standard component of anthropological linguistic inquiry. Traditionally such research has encompassed two broad domains of study – descriptive/linguistic and perceptual/psychological – that have been conducted both for code-specific linguistic documentation and for universal cross-linguistic comparison. In the 20th century, color became “the empirical domain par excellence in which to argue for (and against) the linguistic relativity thesis” (Berlin 2001:27).

The literature on color terminology and perception has grown exponentially since publication of Berlin & Kay's (1969) classic study.28

“In 1969, using the original stimulus set of Lenneberg and Roberts, Brent Berlin and Paul Kay compared the denotations of basic color terms in twenty languages, and based on these findings, examined the descriptions of seventy-eight additional languages from the literature. They reported that there are universals in the semantics of color: the major color terms of all languages being focused on one of eleven landmark colors. Further, they postulated an evolutionary sequence for the development of basic color lexicons according to which black and white precede red, red precedes green and yellow, green and yellow precede blue, blue precedes brown, and brown precedes purple, pink, orange, and gray” (Berlin 2001:28).

Preliminary research into basic color terms in Ban Khor Sign Language appears both to confirm and to challenge aspects of the traditional theory of universal color terminology. Ban Khor Sign Language is a three-color-term language (Nonaka 2001b). Consistent with Berlin & Kay's (1969) original prediction, those three basic color terms, shown in Figure 6, are ‘black’, ‘white’, and ‘red’.

The three basic color terms in Ban Khor Sign Language.

Expression of other colors in Ban Khor Sign Language is achieved in one of two ways (Nonaka 2001b). First, a visual search of the immediate physical environment is undertaken. If an object of the appropriate color can be found, then the speaker points to that object to indicate the color in question. For example, in Figure 7 a native Ban Khor signer describes the color of a carrot by pointing to an orange notebook atop a nearby table: ‘A carrot is … [color search is launched] … orange like this notebook [consultant points to an orange notebook].’

Expression of non-basic color terms. Example: A successful color search of objects in the immediate environment “A carrot is … [color search launched] …” “… orange like this notebook [consultant points to orange notebook].”

Not all color searches, however, are successful. If the color in question cannot be located in the immediate environment, then nonbasic color terms are expressed using one of the three basic color terms – black, white, or red. As an example, see Figure 8. Having scanned the local environment without locating any object similar in color to the deep purple hue characteristic of an eggplant, the linguistic consultant code-switched into Thai Sign Language and said that she really wanted to describe the eggplant as ‘purple’.29

More information about the TSL sign ‘purple’ appears later in this section and also in Figure 12.

The English gloss of her actual TSL utterance is ‘purple none’.

Expression of non-basic color terms. Example: An unsuccessful color search of objects in the immediate environment “An eggplant is … [color search launched but when no object of the appropriate color is found] …” (a) [code switching to Thai Sign Language] … “I really want to say ‘purple’ but there's no sign for ‘purple’ (in Ban Khor Sign Language) …” (b) [code switching back to Ban Khor Sign Language] … “It's black.”

To the extent that Ban Khor Sign Language has three color terms, and those terms are ‘black’, ‘white’, and ‘red’, the indigenous sign language appears to conform to Berlin & Kay's theory. However, Ban Khor Sign Language also appears to contradict their theory in at least one important way: by challenging the operational definition of a “basic” color term. By definition, basic color terms should refer to pure color and not to an object representing the color; thus, gold, turquoise, and orange are not basic color terms. In Ban Khor Sign Language, however, all three basic color terms are signed by pointing to objects – body parts – that represent those colors: hair for ‘black’, teeth for ‘white’, and lips for ‘red’ (see Figure 6).

It is important to note here that ‘black’, ‘white’, and ‘red’ are fully lexicalized in Ban Khor Sign Language. Thus, the pointing31

Studies of lexicalized pointing in ASL strongly suggest that such signs are not analyzed as iconic by the native signer (Petitto 1987, Emmorey et al. 1995).

It is worth noting that in a number of sign languages, certain color terms – especially ‘black’, ‘white’, and ‘red’ – appear to have originated as iconic representations before being lexicalized.

Finally, studying differences and similarities between the color lexicons of the various sign languages in Thailand is useful for comparative and historical linguistic purposes. For example, there is evidence that, like Ban Khor Sign Language, both Old Bangkok Sign Language (Figure 9) and Old Chiangmai Sign Language (Figure 10) were three-color term languages.33

Old Bangkok and Old Chiangmai sign languages are moribund codes. The languages are remembered by and can be elicited from signers over age 45. The data cited here were elicited using a modified version of the Swadesh word list from two male Thai Deaf signers, one born and raised in Bangkok and the other in Chiangmai. Both men attended residential deaf school in Bangkok as children, were members of the first cohort of deaf students at the original deaf school in Dusit District, and as adults have been leaders in the Thai Deaf community.

The modified Swadesh word list was also used to elicit signs from younger adult Thai Deaf signers in the metropolitan Bangkok area who are monolingual in Modern Standard Thai Sign Language. Their elicited signs for ‘black’, ‘white’, and ‘red’ were compared with and found identical to the signs for those words listed in the Thai Sign Language dictionary (Suwanarat et al. 1990). The TSL dictionary clearly demonstrates that modern standard Thai Sign Language is not a three-color-term language, and that colors other than the three core color terms are expressed using initialized signs.

Study of color terms in Ban Khor Sign Language is an ongoing endeavor. The data on color terms cited here were collected from three native Ban Khor signers, two deaf and one hearing. Each consultant used the same three signs for expression of the three basic color terms and employed the same strategies for expression of other color terms, namely launch of a color search of the immediate environment for an object of the appropriate color, or use of one of the three basic color terms for expression of other color terms when a color search of the environment proved unsuccessful.

There is possible evidence to suggest that in addition to the sign ‘hair’/black (Figure 8), another sign ‘eyebrow’/black also existed in Old Chiangmai Sign Language. However, at this early stage of research, I would prefer to err on the side of caution and assume that the linguistic consultant who demonstrated the sign ‘eyebrow’/black was providing the Modern Standard Thai Sign Language lexeme ‘eyebrow’/black, prior to demonstrating the older sign, ‘hair’/black.

The three basic color terms in Old Bangkok Sign Language.

The three basic color terms in Old Chiangmai Sign Language.

TSL has a markedly different color term system: a multi-term color lexicon. Interestingly, however, careful analysis of the various TSL color terms reveals two different types of color vocabulary. As in the country's other sign languages, the three most basic color terms in TSL refer to body parts bearing the appropriate color – eyebrow/‘black’, upper arm/‘white’, and lips/‘red’ (Figure 11). However, as the examples in Figure 12 show, other color terms (e.g., ‘pink’, ‘purple’, ‘yellow’) are “initialized signs,” meaning that they are made using a fingerspelled letter from the Thai manual alphabet.35

The Thai fingerspelling system, a manual representation of the Thai alphabet, was invented by Khunying Kamala Krairiksh, the first principal of the Sesathian School for the Deaf (Sathaporn 1987:283). She developed the system during the 1950s while studying at Gallaudet University and in cooperation with her faculty advisors there. Thus, many letters of the Thai manual alphabet are similar to letters in the ASL fingerspelling system.

The three basic color terms in Thai Sign Language.

Examples of initialized color terms in Thai Sign Language. (Figures reprinted from The Thai Sign Language Dictionary, Suwanarat et al., 1990.)

Most TSL color words are initialized signs. For example, the sign for ‘pink’ is made using the initialized sign “ch” for chomphuu in sii chomphuu, the Thai word for ‘pink’. Similarly, the TSL sign for ‘purple’ is made with the fingerspelled letter “m,” which is the first letter of muang in sii muang ‘purple’, and ‘yellow’, or sii luang, is initialized with the letter “l.” These three signs are typical of the general workings of the second type of TSL color term vocabulary – initialized signs that point to language contact and borrowing from Thai.

Clearly, initialized signs are of a different order than the signs for ‘black’, ‘white’, and ‘red’ in TSL; and the TSL multi-color lexicon is distinct from those of the other known sign languages found in Thailand. Thus, research on color terminology in sign languages in Thailand would appear to be promising for cross-linguistic comparative descriptive purposes, historical linguistic purposes, and perhaps for universal comparative purposes.

In most languages and cultures – although not all (Ochs & Schieffelin 1984, 1986) – adult caregivers, particularly mothers, use a special form of their native language that is specifically modified for use with infants and/or small children. This linguistic register is known as “baby talk” or “motherese,” and it comprises “any special form of a language which is regarded by a speech community as being primarily appropriate for talking to young children and which is generally regarded as not the normal adult use of language” (Ferguson 1964, reprinted in Dil 1971:114).

Where it occurs, baby talk or motherese is commonly assumed to simplify language learning and to contribute to the linguistic development of children. In languages and speech communities where baby talk/motherese is used, a typical or “canonical form develops” (Ferguson in Dil 1971:123). Linguistically, baby talk/motherese involves noticeable changes in phonology, syntax, and lexicon, and even in the paralinguistics of normal language, including the use of special lexical items, mostly monosyllabic words, reduplications, and lack of inflectional affixes (Ferguson in Dil 1971:116–24). Considerable comparative research has been conducted on baby talk/motherese in spoken languages (e.g., Ferguson 1964, 1977; Von Raffler-Engel & Lebrun 1976; Williamson 1979; Blount 1982; Zeidner 1983). Far less is known about baby talk/motherese in signed languages, especially codes other than ASL.

Preliminary research (Nonaka 2001, 2004) indicates that Ban Khor Sign Language has a form of baby talk/motherese. Adults use the register to communicate with infants and small children aged two years or younger. Characteristic features of the special linguistic register include (i) heightened affect, (ii) active physical stimulation of the child, (iii) signing more slowly than usual, (iv) signing close to the child to maximize visual attention, (v) signing on the child's body, and (vi) repetition.

All the features of baby talk/motherese in Ban Khor Sign Language described above are found in the 16-second segment of natural conversation transcribed below. Differences in modality (manual-visual sign language vs. printed text) make it impossible to fully depict the videotaped sequence of talk here. Nevertheless, where it was feasible, still frame-grabs were extracted and are presented in Figures 13, 14, and 15 to illustrate four of the features – heightened affect, active stimulation of the child, signing close to the child to maximize visual attention, and signing on the child's body – of baby talk/motherese in Ban Khor Sign Language.

(1) Transcript excerpt. Participants: Watermelon,36

This child has two names, both of which relate to watermelon. Her Thai name is Jintala, which is a particular variety of the fruit. The child's name sign in Ban Khor Sign Language is also ‘Watermelon’. Hence, I refer to her here by that name.

As indicated in Line 1 and depicted in Figure 13, Mrs. Vien exhibits classic paralinguistic features of baby talk/motherese in Ban Khor Sign. Throughout her interaction with the child, Mrs. Vien demonstrates heightened affect: lots of smiling, highly raised eyebrows and widely opened eyes. She also incorporates lots of active physical stimulation of the child – rubbing the baby's face, stroking her nose, and playfully slapping her hands.

Characteristic features of baby talk/motherese in Ban Khor Sign Language, heightened affect and active physical stimulation of the child.

Characteristic features of baby talk/motherese in Ban Khor Sign Language, signing close to the child to maximize visual attention.

Characteristic features of baby talk/motherese in Ban Khor Sign Language, signing on the child's body.

Mr. Phaiwan's talk too is classic baby talk/motherese. His initial child-directed utterances (lines 1–2) are made while bending directly over Watermelon. The signs ‘you little-birdie’ and ‘feed you’ (Figure 14) are articulated very close to the infant's face, maximizing visual acuity. Furthermore, the entire sequence, especially ‘feed you’, is signed more slowly than in normal adult conversation.

In line 4, Mr. Phaiwan tells the baby, who was born prematurely, that as a result of being fed, ‘Your tummy will get big’, and ‘That's good!’. While signing ‘tummy get big’, (Figure 15) he actually starts the utterance ‘tummy get big’ by touching his hand to the girl's abdomen. Signing on an interlocutor's body is rarely used between adults for purposes of normal, everyday conversation, but the strategy is a classic feature of signed baby talk/motherese.37

I have not researched the matter of signing on an interlocutor's body in the context of adult-adult conversation, but anecdotal evidence based on conversations with Deaf friends suggests that signing on the body might be common in “pillow talk” among signing adults.

Interestingly, the characteristic features of baby talk/motherese in Ban Khor Sign Language also are found in ASL (Erting et al. 1990:105). Given the very different socioeconomic, historical, and cultural contexts in which Ban Khor Sign Language, an indigenous sign language, and ASL, a national sign language, developed, documentation and analysis of the baby talk/motherese registers in the two languages offer a rich opportunity not only for original description but also for cross-linguistic comparison. Moreover, original linguistic description and cross-linguistic comparison might well allow for broader theorizing about universal linguistic features of baby talk/motherese in signed languages and, by extension, in human language generally. As a working hypothesis: The defining features of baby talk/motherese in Ban Khor Sign Language will resemble those of all other human languages in form (phonological, syntactic, lexical, etc.) and function (language acquisition and enculturation), differing only in terms of modality (expression through the manual-visual channel).38

Channel/modality allows for one feature – signing on the child's body – of baby talk/motherese in manual-visual languages that is not found in spoken languages.

To conclude, using Thailand as a case study, this article has argued the importance of remembering to include sign languages in discussions of linguistic diversity and language endangerment as well as in language preservation efforts. At present, we do not know exactly how many sign languages there are in Thailand. As a consequence, our understanding of the country's language ecology is limited and incomplete. There is documented evidence of at least seven signed codes that are of three general types: national, indigenous, and original language varieties. The national sign language, TSL, is used widely throughout Thailand and appears to be thriving. The continued existence of indigenous (e.g., Ban Khor) and original (e.g., Old Bangkok and Old Chiangmai) sign languages, on the other hand, is uncertain.

As little as we know about manual-visual codes in Thailand, it is still far more than is known about sign languages, especially indigenous and original varieties, in most other areas of the world. Historical particularities – the belated recognition of sign languages as languages and Deaf people as linguistic minorities – have resulted in severe underdocumentation and underdescription of codes expressed in the manual-visual channel. Sign languages are threatened for the same complex reasons (demographic, political, economic, social, educational, etc.) as are many spoken languages. However, sign languages and the speech communities associated with them are also needlessly threatened owing to benign neglect – the continued failure to remember to include them in linguistic documentation, preservation, and revitalization efforts.

As we have seen, study of sign languages enriches our collective knowledge of linguistics and anthropology, underscoring the true linguistic (signed as well as spoken) and cultural (Deaf as well as hearing) diversity in the world today. As with spoken languages, it is often the most powerless, underdescribed sign language isolates (e.g., indigenous sign languages) or marginalized, moribund language varieties (e.g., original sign languages) that preserve unique or less common linguistic features, reflect the true linguistic diversity associated with natural human sign languages, and thereby enrich our understanding of universal grammar and linguistic typology.

“What is needed at this point is a large-scale, in-depth sociolinguistic study” of the world's sign languages (Woodward 2000:34). Yet unless such research is undertaken soon, many signed codes, both known and presently unknown, are in danger of extinction within a generation or two. Unfortunately, many sign languages are dying out or are on the verge of disappearing without ever being recorded or described – a fact that underscores the urgency of remembering these forgotten endangered languages.

“Name” and Foreigner” in Ban Khor Sign Language.

Selected hand configurations. (Figures reprinted from The Signs of Language, Klima, Bellugi & Battison et al., 1979.)

“B” handshape palm-orientation #1. (Figures reprinted from An English Dictionary of Japanese Signs, Japanese Federation of the Deaf, 1991; A Basic Course in American Sign Language, Humphries, Padden & O'Rourke, 1985; The Thai Sign Language Dictionary, Suwanarat et al., 1990.)

“B” handshape palm-orientation #2. (Figures reprinted from An English Dictionary of Japanese Signs, Japanese Federation of the Deaf, 1991; A Basic Course in American Sign Language, Humphries, Padden & O'Rourke, 1985; The Thai Sign Language Dictionary, Suwanarat et al., 1990.)

“B” handshape palm-orientation #3. (Figures reprinted from An English Dictionary of Japanese Signs, Japanese Federation of the Deaf, 1991; A Basic Course in American Sign Language, Humphries, Padden & O'Rourke, 1985; The Thai Sign Language Dictionary, Suwanarat et al., 1990.)

The three basic color terms in Ban Khor Sign Language.

Expression of non-basic color terms. Example: A successful color search of objects in the immediate environment “A carrot is … [color search launched] …” “… orange like this notebook [consultant points to orange notebook].”

Expression of non-basic color terms. Example: An unsuccessful color search of objects in the immediate environment “An eggplant is … [color search launched but when no object of the appropriate color is found] …” (a) [code switching to Thai Sign Language] … “I really want to say ‘purple’ but there's no sign for ‘purple’ (in Ban Khor Sign Language) …” (b) [code switching back to Ban Khor Sign Language] … “It's black.”

The three basic color terms in Old Bangkok Sign Language.

The three basic color terms in Old Chiangmai Sign Language.

The three basic color terms in Thai Sign Language.

Examples of initialized color terms in Thai Sign Language. (Figures reprinted from The Thai Sign Language Dictionary, Suwanarat et al., 1990.)

Characteristic features of baby talk/motherese in Ban Khor Sign Language, heightened affect and active physical stimulation of the child.

Characteristic features of baby talk/motherese in Ban Khor Sign Language, signing close to the child to maximize visual attention.

Characteristic features of baby talk/motherese in Ban Khor Sign Language, signing on the child's body.