According to the UN Migration Agency, migrants make up one billion people worldwide. Migration has become a key issue in domestic and international politics, largely because it increases the social and cultural heterogeneity of a population. A longstanding consensus in the social sciences has been that heterogeneity—ethnic, linguistic, religious, genetic, or social—undermines public goods provision and weakens overall economic performance (e.g., Alesina, Baqir, and Easterly Reference Alesina, Baqir and Easterly1999; Ashraf and Galor Reference Ashraf and Galor2013; Baldwin and Huber Reference Baldwin and Huber2010; Miguel and Gugerty Reference Miguel and Gugerty2005). This relationship has been documented in so many settings as to be considered “one of the most powerful hypotheses in political economy” (Banerjee, Iyer, and Somanathan Reference Banerjee, Iyer and Somanathan2005, 636). One of the leading explanations for this phenomenon is the inability of diverse societies to solve collective action problems. In a heterogeneous setting, the argument goes, cooperative norms do not apply to all, while weak social ties prevent the identification and punishment of uncooperative individuals (Fearon and Laitin Reference Fearon and Laitin1996; Habyarimana et al. Reference Habyarimana, Humphreys, Posner and Weinstein2009).

What has been largely overlooked in this literature, however, is that by weakening informal norms and networks and increasing cultural heterogeneity, migration may increase individuals’ willingness to engage with the state, a potential third-party enforcer of cooperation. Over time, this may contribute to the accumulation of state capacity, as it enables the state to better enforce its rules and to regulate private economic behavior. The greater reach of the state, in turn, facilitates the provision of market-supporting public goods, enabling arm’s length transactions, and advancing economic development more broadly (Besley and Persson Reference Besley and Persson2014; Dincecco Reference Dincecco2017; Lee and Zhang Reference Lee and Zhang.2017). Importantly, the economic implications of these differences in the state–society relationship are conditional on the quality of state institutions. When the state is predatory, the availability of informal enforcement mechanisms, which are stronger in homogeneous communities, can facilitate the provision of local public goods and support private economic activity. By contrast, in common-interest states,Footnote 1 the state’s enhanced ability to regulate economic behavior in heterogeneous communities creates more opportunities for predictable and enforceable arm’s length transactions and generates superior economic outcomes.

I test this argument using an original micro-level dataset on the size and diversity of the migrant population settled in the territory transferred from Germany to Poland in the aftermath of World War II (WWII). The westward shift in Poland’s borders triggered the resettlement of more than five million people, about one-fifth of Poland’s prewar population, from the USSR, Central Poland, and Western and Southern Europe into the communities abandoned by ethnic Germans. Arbitrary resettlement procedures adopted by the Polish authorities produced varying degrees of cultural heterogeneity at the local level. Some municipalities were populated by migrants of the same origin, while others were populated by migrants of different origins. Migrants resettled earlier in the process were able to stay together upon migration while migrants resettled at later stages were dispersed across different areas. The resulting variation in the composition of resettled communities allows me to examine how shared informal norms and networks affect social organization and economic outcomes.

This study shows that homogeneous migrant groups were more likely to establish private-order organizations for the provision of local public goods, such as volunteer fire brigades, while diverse migrant groups faced greater coordination challenges and eventually came to rely on state organizations for public goods provision. I further show that although heterogeneity carried no economic benefits during state socialism, it predicts better economic outcomes after Poland’s transition to a market economy in 1989. Communities settled by diverse migrant groups raised higher tax revenues in the early 1990s and, by the mid-1990s, registered higher entrepreneurship rates and personal incomes than communities settled by migrants from the same region. I also find that the relationship between heterogeneity and entrepreneurship is mediated by the local differences in the state–society relationship, while the differences in incomes may be due to direct effects of heterogeneity on productivity under a market economy. Thus, at a critical historical juncture in Poland’s history, the uprooting and mixing of culturally diverse populations increased the frequency of individual interactions with the state and, after the transition to the market, resulted in a wealthier and more entrepreneurial society.

These patterns cannot be explained by levels of human capital or other group-specific characteristics, sorting, differential state policies, or variation in infrastructure and industrial potential within the formerly German territories. Furthermore, these results are robust to nonparametric modeling strategies and not sensitive to potential unobserved confounding.

The article builds on the body of research that emphasizes the importance of formal institutions and state capacity for economic development (e.g., Dincecco Reference Dincecco2017; Greif Reference Greif1993, Reference Greif2006; North Reference North1990). I advance this work, however, by emphasizing that even within the same state, communities’ demand for formal enforcement may vary with the availability of informal institutional alternatives, independent of their relative effectiveness. Because institutional equilibria are path-dependent, informal enforcement may continue to predominate in some localities following a change in formal institutions, impeding the accumulation of state capacity and reducing economic activity. As a result, past levels of cultural heterogeneity may have enduring consequences for the degree of social control exercised by contemporary states.

The finding that heterogeneous communities are more economically successful in the long run challenges the predominant view of diversity as harmful to economic development and demonstrates the advantages of tracing the development of heterogeneous communities across different institutional settings. It may be no coincidence that the majority of studies pessimistic about the prospects of heterogeneous societies are based on one-time snapshots of the relationship between diversity and development, an approach that stands at odds with the evidence that many states developed by homogenizing their diverse populations through nation and state building (Darden and Mylonas Reference Darden and Mylonas2016; Wimmer Reference Wimmer2016).

The findings also challenge the prevailing view of social capital as contributing to economic growth and weakening with migration and cultural heterogeneity (Knack and Keefer Reference Knack and Keefer1997; Putnam Reference Putnam2007). My analysis suggests that informal norms and networks are a poor substitute for formal institutions in developed market economies such as Poland. The article also contributes to the growing empirical literature on the legacies of displacement and ethnic cleansing in post-WWII Europe (e.g., Bauer, Braun, and Kvasnicka Reference Bauer, Braun and Kvasnicka2013; Becker et al. Reference Becker, Grosfeld, Grosjean, Voigtländer and Zhuravskaya2018; Charnysh and Finkel Reference Charnysh and Finkel2017; Sarvimäki, Uusitalo, and Jäntti Reference Sarvimäki, Uusitalo and Jäntti2009).

ARGUMENT

I argue that communities at different levels of cultural heterogeneity vary in their ability to cooperate for the provision of public goods and, as a result, in their receptivity to state regulation. In homogeneous settings, widely shared reciprocity norms discourage free riding and dense social ties facilitate monitoring and sanctioning of ingroup members (Habyarimana et al. Reference Habyarimana, Humphreys, Posner and Weinstein2009; Miguel and Gugerty Reference Miguel and Gugerty2005).Footnote 2 In the absence of effective third-party enforcement, homogeneous communities with strong social ties will have greater voluntary provision of public goods than heterogeneous communities, where informal mechanisms of cooperation will be less effective. Higher levels of public goods provision, in turn, will support higher levels of private economic activity.

The relationship between homogeneity and public goods provision may change, however, following the introduction of state institutions. In homogeneous communities, the state’s bureaucratic apparatus has to compete with endogenous organizational solutions to the problems of social control and public goods provision (Migdal Reference Migdal1988). Because such communities are effective at “self-help collective action,” they have less need to rely on the state to maintain security or enforce contracts (Bodea and LeBas Reference Bodea and LeBas2014). As a result, the reach of the state will be more limited, and informal institutions will continue to play a role in enforcing cooperation. Even when state institutions are highly functional, switching from informal to formal enforcement entails substantial coordination costs and does not pay off until a sufficiently large population has done so (Gans-Morse Reference Gans-Morse2017; Greif and Kingston Reference Greif, Kingston, Schofield and Caballero2011).

Heterogeneity, on the other hand, increases the need to rely on an external agent, such as the state, for the provision of public goods. Heterogeneous communities have more to gain from state enforcement than homogeneous communities because they lack alternative forms of social control and have lower levels of voluntary cooperation. The state can also penetrate and govern weak heterogeneous communities more easily because such communities lack effective collective action mechanisms to resist state encroachment (Migdal Reference Migdal1988). Thus, the cultural composition of a community and the resulting quality of endogenous (informal) enforcement in one period will be inversely related to the demand for exogenous (formal) enforcement in the subsequent period (Greif and Tabellini Reference Greif and Tabellini2017).

H1: Cultural heterogeneity undermines informal cooperation strategies and increases the demand for third-party (e.g., state) provision of public goods.

Over time, more frequent and encompassing state-society interactions in heterogeneous communities enhance the state’s ability to monitor private economic activity and collect revenue. Greater reliance on state-provided public goods and services also increases incentives to invest in state capacity and pay taxes (Slemrod Reference Slemrod1992). By contrast, the availability of community-provided public goods in homogeneous settings will lower the frequency and depth of interactions with the state, hindering the state’s ability to regulate social and economic activity and reducing tax compliance (Bodea and LeBas Reference Bodea and LeBas2014). Over time, this will result in lower accumulation of state capacity. The dynamic is self-reinforcing: Low state capacity reduces the state’s ability to collect revenue and to provide public goods, and increases the incentives to rely on community-provided substitutes, which further undermines the buildup of state capacity.

H2: Greater demand for state-provided public goods in heterogeneous communities will facilitate the accumulation of state capacity over time.

The resulting differences in state capacity across heterogeneous and homogeneous communities will have important long-run implications for economic development. State capacity is crucial for the provision of secure property rights, the regulation of markets, and the enforcement of contracts. Higher levels of provision of these public goods increase the returns to productive economic activity and lower the costs of economic exchange, increasing long-run economic prosperity (Besley and Persson Reference Besley and Persson2014; Dincecco Reference Dincecco2017; North Reference North1990). While these public goods can be provided endogenously through informal norms and networks, this latter solution is only “second-best,” as it limits the gains from specialization and economies of scale, lowers competition, and can result in market segmentation (Fafchamps Reference Fafchamps2004; Robinson Reference Robinson2016).

And yet, many states do not use their capacities to provide market-supporting public goods. An increase in the administrative capacity of a predatory state may lower the returns to productive economic activity by increasing the risk of expropriation. When state institutions benefit only a few and fail to protect private property, greater access to endogenous enforcement mechanisms in homogeneous settings allows for higher levels of private economic activity. Under communism, informal networks and shared culture facilitated the production and distribution of consumer goods despite the ban on private entrepreneurship (McMillan and Woodruff Reference McMillan and Woodruff2000). Thus, the accumulation of state capacity advances private economic activity only in states with “good” formal institutions. Such states are variously categorized as inclusive or common interest because they protect property rights and enforce contracts of all citizens (Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2012; Besley and Persson Reference Besley and Persson2014).

H3: Higher state capacity facilitates private economic activity only in common-interest states.

What happens when the quality of existing state institutions changes? Heterogeneous communities, already more dependent on state institutions, will adjust to the improvements in the quality of state institutions sooner and benefit from these improvements to a greater extent than homogeneous communities. At the same time, heterogeneous communities will be more vulnerable to the deterioration in the quality of state institutions than homogeneous communities, where informal substitutes are available.

H4: Changes in the quality of state institutions have a greater influence on outcomes in heterogeneous communities.

In sum, cultural heterogeneity at the community level weakens informal enforcement mechanisms and increases the demand for external enforcement and public goods provision. Over time, this may contribute to the accumulation of state capacity and, under common-interest state institutions, generate greater wealth and entrepreneurship rates. Figure 1 presents the main parts of the argument.

FIGURE 1. Schematic Representation of the Argument

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

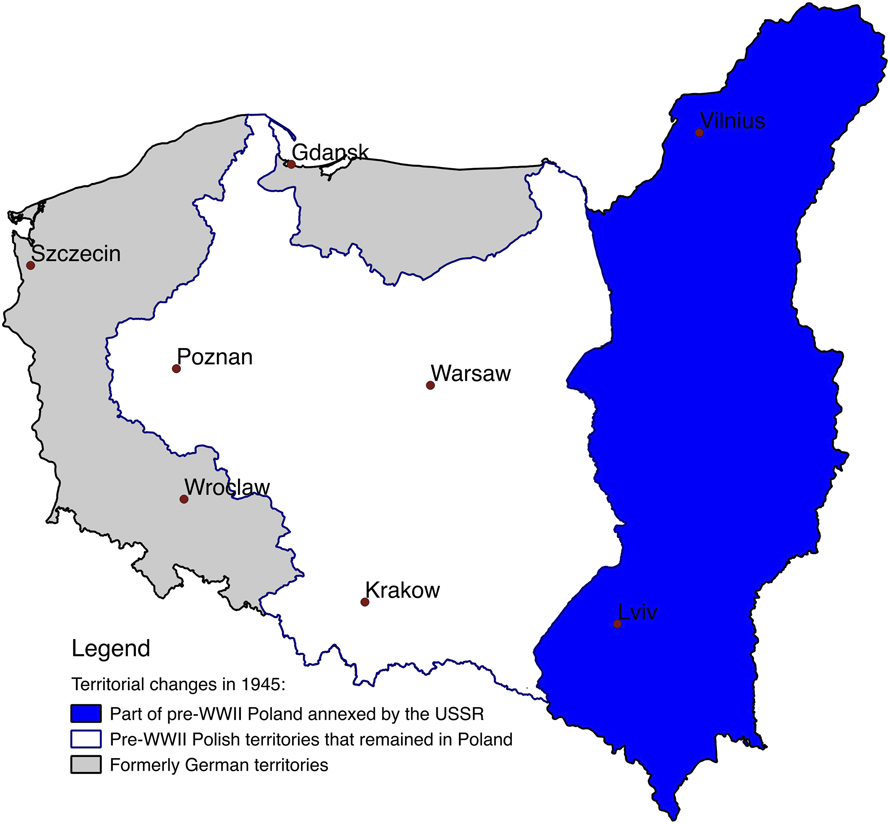

In 1945, Poland’s borders were moved 150 miles to the west. The country surrendered 46% of its prewar territory east of the Curzon line (Kresy) to the Soviet Union and gained an equivalent 26% of prewar territory east of the Oder-Neisse line from Germany (see Figure 2). The border changes set off population transfers. Nearly eight million Germans fled or were expelled, and the area east of the Oder-Neisse was repopulated by over five million Poles, a diverse group originating from the territories annexed by the Soviet Union, Central Poland, and Southern and Western Europe. Only the so-called autochthonous population (autochtoni) stayed, numbering 936,777 people in 1948 and concentrated in Upper Silesia and Masuria. By 1948, immigrants accounted for 81% of the population in the former German territories.

FIGURE 2. Territorial Changes in Poland in 1945

The Polish authorities sought to complete the population transfers as swiftly as possible to ensure the permanence of the new borders and to secure ownership of the German assets. However, relocating millions in a state devastated by war and during an intense political struggle proved “more than the new administration could handle” (Kenney Reference Kenney1997, 158). The situation was exacerbated by a dearth of knowledge about an area that had historically belonged to another state. The resettlement proceeded at a breakneck pace but in a haphazard manner. While the east-west direction of the railway lines shaped the broad distribution of regional groups within the former German territories, the actual shares of each group and the resulting diversity of migrant populations at the local level depended on the arbitrary decisions by Soviet and Polish officials ignorant of local socio-economic conditions. Although the authorities prioritized transferring entire communities and families, housing shortages and coordination failures prevented most families from settling in the same location as their friends and neighbors (Dworzak and Goc Reference Dworzak and Goc2011).

Assignment decisions were made indiscriminately, and migrants were frequently sent from one destination to another when it turned out that the officials had underestimated housing capacity in a given area. Migrant Henryk Zaborowski described his experience with the Polish Repatriation Office (Państwowy Urząd Repatriacyjny, PUR) as follows: “A PUR employee would write the name of a destination in chalk on the side of the railway car, and the cars would be uncoupled and shunted down the tracks” (Zaborowski Reference Zaborowski and Jalowiecki1970, 175). PUR Director Wladyslaw Wolski lamented that migrants were often offloaded midway to their destinations, in the middle of an open field, because the conductors lacked planned itineraries (Ciesielski Reference Ciesielski2000, 23).

Haphazard assignment by short-staffed administrators produced considerable variation in the distribution of migrants. For example, most of the residents of the Galician village of Budki Nieznanowskie were settled together in the village of Gierszowice, Opole province. For them, only the material environment had changed following migration. The inhabitants of the nearby village of Busk, by contrast, were dispersed across 19 villages and eight counties of Opole province, sharing villages with migrants from other regions (Dworzak and Goc Reference Dworzak and Goc2011).

All Polish citizens, migrants from different pre-WWII provinces saw each other as culturally distinct due to the legacy of imperial partitions and low mobility prior to 1945. Reports of intergroup conflicts and misunderstandings were ubiquitous in settlers’ and officials’ accounts alike. Thum (Reference Thum2011, 13) writes: “Settlers from central Poland turned up their noses at those ‘from beyond the Bug’ (zza Buga). They called them Zabuzhanie, which could be translated as ‘hillbillies,’ implying that eastern Poles had been living in the back of beyond.” Studies of heterogeneous villages decades after the transfers concluded that daily interactions were still more frequent within rather than between groups (Chmielewska Reference Chmielewska1965; Pawłowska Reference Pawłowska1968).

Diverse and Homogeneous Migrant Communities Upon Resettlement

WWII weakened both formal and informal institutions across Poland, but the situation in the formerly German territories was particularly dire. The German administration departed in 1945, and the emerging Polish institutions were “weak, facade-like structures unable to control the situation” (Grabowski Reference Grabowski2002, 148). The Citizens’ Police (Milicja Obywatelska, MO), tasked with maintaining law and order, had neither the manpower nor willingness to fulfill its duties. Initially, state authority was confined to cities and towns, and the newly established migrant communities were expected to fend for themselves.

In this environment, homogeneous migrant communities had an important advantage—shared norms and, in some cases, shared networks. Upon migration, such groups were able to quickly replicate the familiar patterns of associational behavior and reestablish order. One migrant describes his arrival to the village of Pyrzany in July 1945 as follows: “Houses in the very center of the village were occupied by the pastor, the organist, and others who deserved it. The poor settled in houses on the outskirts” (Halicka Reference Halicka, Halicka and Mykietów2011, 49). Although the village already had an elder (sołtys), a man from central Poland who had arrived earlier, the more numerous Galicja group elected their own representative. Migrants soon formed a volunteer fire brigade that doubled as a militia, founded a preschool, and reopened the German shops (Halicka Reference Halicka, Halicka and Mykietów2011). In this homogeneous community, shared norms and networks enabled the creation of private-order organizations for the provision of security and other public goods, such as the volunteer fire brigade, facilitating the resumption of private economic activity.

The localities settled by migrants from different regions faced greater challenges. Next to Pyrzany lies the village of Oksza, which was settled by diverse migrants from Central Poland and the USSR. A migrant described his first year in Oksza as follows: “A lot of destruction could have been avoided through better organization of resettlement, but there was no oversight of the process: Everyone was looting and pillaging, like a hungry wolf would do to his prey” (Solinska and Koniusz Reference Solinska and Koniusz1961). To this day, Oksza has no volunteer fire brigade or other communal organizations.

In the absence of shared norms and networks, heterogeneous communities were reluctant to invest in private-order organizations for the provision of public goods or norm enforcement. For many migrants, it was easier to opt out of collective activities altogether to pursue one’s self-interest, sometimes at the expense of others. Not surprisingly, crime rates were higher in heterogeneous areas for decades after the resettlement (see Appendix Section C.3).

Divergent Cooperation Mechanisms

Population transfers were followed by the gradual expansion of Communist rule. The state and its organizations soon played an outsized role in the formerly German territories, providing vital public goods and mediating intergroup conflicts. Stasieniuk (Reference Stasieniuk, Michalak, Sakson and Stasieniuk2011, 154) observes that in resettled communities, formal institutions “not only represented state authority, but also served as an intermediary between different societal groups. It is on the basis of these institutions that social contact was established.” Similarly, Sakson (Reference Sakson2011, 85–6) acknowledges that the new regime was “seen as an organizer of social life” in migrant communities; Kersten (Reference Kersten1991, 165) argues that displacement fostered “ties to new authorities.” Data on Communist Party membership support these conclusions (see Appendix C.1). Of course, not all state–society interactions were voluntary: Mass migration also weakened the resistance to communist authorities and their socioeconomic interventions, as evidenced, for example, by the greater number of collective farms and the higher infiltration of the Catholic Church by the so-called Red Priests (Nalepa and Pop-Eleches Reference Nalepa and Pop-Eleches2018).

I expect that state–society relations varied not only between the resettled and non-resettled areas, but also across migrant communities at different levels of cultural heterogeneity. In homogeneous communities, state institutions were more likely to compete with informal social and economic structures; as a result, their reach was limited. In heterogeneous communities, resistance to the new order—and the organizations that came with it—was weaker. Although the communist institutions encroached on private property and stifled political competition, the state filled an important need for the provision of public goods that heterogeneous communities struggled to provide on their own. Thus, I expect the demand for and the resulting reach of state institutions to increase with heterogeneity.

The shift in approaches to elderly care is illustrative. Jasiewicz (Reference Jasiewicz1972) writes that the traditional custom of families taking care of their elderly failed in diverse communities because social sanctions for noncompliance were ineffective. He finds that the elderly instead increasingly turned to the state, which guaranteed healthcare and a pension in exchange for getting titles to their land. The state was even more important for enforcing cooperation in agricultural work, a role resented in homogeneous villages but appreciated in diverse settings. In the heterogeneous village of Pracze in Lower Silesia, cultural differences restricted the mutual provision of neighborly help to the families and migrants from the same village. The scope of neighborly assistance widened, however, once the state instituted mandatory in-kind contributions to the social welfare fund. State institutions also began to commission and remunerate assistance to the sick, widowed, and elderly, historically provided through voluntary cooperation (Pawłowska Reference Pawłowska1968, 95). State enforcement was also used to maintain the commons and curb free-riding. In Pracze, the devastation of communal fields and orchards or the damage to communal equipment was increasingly addressed in court rather than through the village head or authority figures (Pawłowska Reference Pawłowska1968, 198). By contrast, the residents of homogeneous villages did not need state enforcement and continued to rely on informal enforcement strategies. In the village of Pyrzany, for example, the residents regretted not being “fully free in their activities […and having to] reckon with the new [Communist] political order and to negotiate with regional and county authorities” (Halicka Reference Halicka, Halicka and Mykietów2011, 53).

Institutions, State Capacity, and Economic Outcomes

Poland’s post-WWII history allows a test, however imperfect, of the relationship between heterogeneity, state capacity, and private economic activity in different institutional settings.

In 1950, Poland introduced central planning, nationalized industry, and attempted to collectivize agriculture. Although private farming remained dominant, large estates in the resettled regions were transformed into state farms. The focus on heavy industry undermined the service sector, and many small workshops and businesses were nationalized, taxed into bankruptcy, or forced underground. The state was most successful in quashing private economic activity in the formerly German territories, where its reach was deeper (see Appendix C.2).

Restrictions on private entrepreneurship were partially reversed in 1957, following worker protests in Poznań. Gradually, the “socialist” economic model was altered through the introduction of market elements. By 1980, 602,000 legal private businesses were officially registered, and many more operated informally (Kochanowski Reference Kochanowski2010, 185).

Even so, the reliance on state enforcement carried few advantages because the legal protections afforded to private property remained inadequate. Informal norms and networks, on the other hand, facilitated access to scarce goods and increased opportunities for economic exchange. Even the officially registered private businesses had to rely on informal connections to obtain tools and supplies (Kochanowski Reference Kochanowski2010, 185). Because shared culture facilitates informal coordination and enforcement, I expect homogeneous communities to have been more likely to sustain private economic activity under state socialism.

In 1988, the Polish government removed all remaining barriers to private entrepreneurship. “Shock therapy” economic reform was launched in 1989, expressly to reduce state influence over the economy. Between 1989 and 1994, the share of the private sector in total employment increased from 12% to 61%. Most private sector firms were small and established from scratch rather than by privatization.

Importantly, economic and political reform did not generate a void in formal enforcement. While the “party” element of the party-state disappeared, most other state organizations were subsequently strengthened. This is particularly evident with respect to revenue collection. Under state socialism, taxation was largely indirect, and the state extracted large revenues from industrial enterprises it owned or controlled. During the transition to a market economy, the state was forced to contend with outstanding debt and rising budget deficits, and also to offset declining revenues from state enterprises. In 1992, direct taxes on personal and corporate income were introduced. Tax collection depended largely on taxpayers’ compliance, secured in part through the continuing provision of public goods and services (Easter Reference Easter2002). Maintaining sufficient tax revenue, in turn, enabled the state to expand its administrative capacity and strengthen the institutions for the protection of private property and enforcement of contracts.

A key reform that strengthened state capacity at the local level was the March 1990 Law on Local Self-Government, which expanded the authority of over 2,400 municipalities (gminy). From then on, local bureaucrats were accountable exclusively to elected local councils and paid out of the municipal budgets. Municipalities were now authorized to collect and spend their own fiscal revenues from immovable property, agricultural income, and vehicles, within caps set at the national level.Footnote 3 Municipalities became responsible for financing the maintenance and improvement of local infrastructure, primary education, healthcare, and social assistance. Some negotiated numerous tax exemptions and special deals, yielding to local interests, while others set high tax rates and increased spending on key public goods, supporting private economic activity (Swianiewicz Reference Swianiewicz1996).

The increased fiscal autonomy and responsibilities of local governments widened subnational differences in the degree and quality of governance. The ability to pay bureaucrats affected the privatization of communal property, the distribution of social benefits, and the process of licensing for new businesses and regulating private economic activity more broadly. Localities with the highest levels of fiscal and bureaucratic capacity also promoted entrepreneurship by funding business incubator programs, guaranteeing start-up loans, and offering training programs for the unemployed (Misiag Reference Misiag2000). For example, in the heterogeneous town of Bartoszyce, the municipal government created the Department for the Promotion and Social Affairs, which centralized information about all registered businesses and offered training to the unemployed (Gorzelak and Jalowiecki Reference Gorzelak and Jalowiecki1996). In Dzierzgoń, settled by migrants from Kresy and Central Poland, the government established the Society for the Development of Dzierzgoń to offer legal and economic advice to those interested in starting new firms, as well as the Mutual Guarantee Fund to help small and medium enterprises overcome capital barriers (Gorzelak and Jałowiecki Reference Gorzelak and Jałowiecki1999).

I expect the transformation of national institutions and the decentralization reform to have different implications in homogeneous and heterogeneous communities. Heterogeneous communities, where informal institutions were less effective, would benefit from the improvement in the quality of formal institutions to a greater extent than homogeneous communities. Economic actors in heterogeneous communities could now take advantage of the increased protection of property rights and contract enforcement to engage in market transactions and register new firms. Greater demand for government-provided public goods in heterogeneous communities would also increase their investment in fiscal capacity and thus their ability to finance public goods necessary to support private economic activity. Both channels would contribute to higher private entrepreneurship and incomes in more heterogeneous communities under a market economy.

DATA AND EMPIRICAL STRATEGY

Historical Data on Population Transfers

The data on the origin of population in 1,217 historic municipalities (gminy) of the former German territories come from a census commissioned by the Ministry for the Recovered Territories in December 1948, after the population transfers were largely completed. The data were never published and are contained in the Polish Archiwum Akt Nowych.

The census recorded the size of four distinct population groups: repatriates from the USSR, settlers from Central Poland, reemigrants from Western Europe, and the autochthonous population (see additional information about these groups in Appendix A.1). Polish sociologists generally agree that these are the main categories of residents in the former German territories after WWII (Chmielewska Reference Chmielewska1965). However, this categorization does not encompass all cultural cleavages and thus understates the diversity of the population in this region, which biases against the hypotheses outlined above. The autochthonous population included Protestant Mazurians and Catholic Warmiaks in the north and Catholic Silesians in the southwest, all of whom spoke different dialects and sometimes not a word of Polish. Reemigrants from Western Europe were a diverse group originating in France, Germany, Yugoslavia, and other states. The repatriates from rural Galicia (Ukrainian SSR) included both Catholic and Greek Orthodox populations and had few cultural similarities with repatriates from the more urbanized Lithuanian SSR. The settlers from Central Poland arrived from all three former imperial partitions and were also an internally heterogeneous group.

However, in a given municipality usually only one of these subgroups would be present because the population movement occurred from east to west and followed three major railway routes (see Figure A.2 in the Appendix). As a result, at the micro level migrants in each of the three categories typically came from the same prewar province.

Measuring Diversity

I decompose diversity into (1) the heterogeneity of the migrant population and (2) the share of migrants, following Alesina, Harnoss, and Rapoport (Reference Alesina, Harnoss and Rapoport2016). The first component, Divmig, measures the diversity of migrant groups in each municipality. If s j is the share of migrants from region j from the total population of migrants, with j = 1,…, J, then migrant heterogeneity can be expressed as ![]() ${\rm{Di}}{{\rm{v}}_{mig}} = \sum\limits_{j = 1}^J {\left[ {{s_j} \times \left( {1 - {s_j}} \right)} \right]}$. This expression does not depend on the share of the indigenous population.

${\rm{Di}}{{\rm{v}}_{mig}} = \sum\limits_{j = 1}^J {\left[ {{s_j} \times \left( {1 - {s_j}} \right)} \right]}$. This expression does not depend on the share of the indigenous population.

The second component, Divresettled, measures the share of migrants in the total population. In the Polish context, it serves as a control variable, capturing the effects of displacement and separating migrants from the natives. The latter were concentrated in specific regions, decided against emigration to Germany in the 1940s for economic and political reasons, and could obtain German passports and work abroad in the 1990s, before Poland joined the EU. Divmig was a product of arbitrary assignment of migrants during population transfers, whereas Divresettled can be explained by the historic patterns of nation-building in Germany and Poland.Footnote 4

Figure 3 shows that migrant diversity varied considerably across the formerly German municipalities while the indigenous population was heavily concentrated in the south and northeast. In 82% of the local communities, the share of migrants exceeded 80%.

FIGURE 3. Migrant Diversity and the Autochthonous Population at the Municipal Level in 1948

Unit of Analysis

I test my theoretical predictions using historic and contemporary data at the level of municipalities. This is the smallest unit for which both historical and contemporary data are available. Municipalities are small enough to ensure that migrants from one region will interact with migrants from a different region at high values of Divmig. Furthermore, contemporary municipalities are self-contained social units with legislative and governing bodies and are thus appropriate for studying the effects of diversity on social and economic outcomes. One challenge with adopting this unit, however, is that municipal boundaries have changed considerably since 1939. To account for these changes, I aggregated historical communal (1939) and municipal (1948) data to the level of 630 contemporary municipalities, which are larger in size than historical units (see details in Appendix B.3). If contemporary municipality borders split historical municipalities, I weighted the historical data by the proportion of the overlapping area.Footnote 5

Empirical Strategy

As noted above, officials tasked with resettlement were unfamiliar with the new territory and assigned migrants to locations in an arbitrary manner. I draw on Polish and German data to examine potential determinants of the resulting local heterogeneity. The intuition is that assignment was as-if random, conditional on covariates discussed below, and thus the estimated coefficient on Migrant Diversity can be interpreted causally.

I estimate the following model: ![]() ${y_{i}} = \alpha + \beta \,\times {\rm{Di}}{{\rm{v}}_{mi{g_{i}}}} + \gamma \,\times\, {\rm{Di}}{{\rm{v}}_{resettle{d_{i}}}} + \theta \,\times\, {X_{i}} + {D_j} + {\varepsilon _{i}}$, where y i is the outcome in municipality i; Divmig and Divresettled are the two components of diversity discussed above, X i is a set of municipality-level covariates, and D j is a vector of district-level fixed effects, and ε i are errors. When spatial dependence is present, Moran eigenvectors m i are included as covariates to filter out residual autocorrelation (Thayn and Simanis Reference Thayn and Simanis2013).Footnote 6

${y_{i}} = \alpha + \beta \,\times {\rm{Di}}{{\rm{v}}_{mi{g_{i}}}} + \gamma \,\times\, {\rm{Di}}{{\rm{v}}_{resettle{d_{i}}}} + \theta \,\times\, {X_{i}} + {D_j} + {\varepsilon _{i}}$, where y i is the outcome in municipality i; Divmig and Divresettled are the two components of diversity discussed above, X i is a set of municipality-level covariates, and D j is a vector of district-level fixed effects, and ε i are errors. When spatial dependence is present, Moran eigenvectors m i are included as covariates to filter out residual autocorrelation (Thayn and Simanis Reference Thayn and Simanis2013).Footnote 6

I supplement this specification with regressions that adjust for weights obtained from nonparametric covariate balancing generalized propensity score (npCBGPS) analysis. This approach optimizes covariate balance between the treatment and the control units, reduces model-dependence, and accommodates continuous treatments (Fong, Hazlett, and Imai Reference Fong, Hazlett and Imai2018). I also explore sensitivity of the results to the unobserved confounding.

To establish whether reliance on informal enforcement strategies and resulting differences in state capacity are indeed the mechanisms behind the effects of migrant diversity in 1948 and contemporary economic outcomes, I use sequential g-estimation analysis (Acharya, Blackwell, and Sen Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2016).

Dependent Variables

The theory has a number of observable implications that are summarized in Table 1 and discussed in more detail below.

TABLE 1. Theoretical Concepts, Measurement, and Hypothesized Effects of Migrant Diversity

Enforcement Strategies and Fiscal Capacity

I argue that diversity will undermine informal cooperation mechanisms and increase the demand for formal, third-party enforcement. The role played by informal enforcement mechanisms is difficult to quantify. An additional difficulty arises from the fact that more than seventy years have passed since the population transfers were completed. To get around this problem, I use Greif and Tabellini’s (Reference Greif and Tabellini2017) insight that differences in the strength of informal norms and networks can be inferred from the type and density of local organizations. In the Polish context, a good proxy for the differences in the strength of informal rules is the presence of volunteer fire brigades (OSPs). An OSP relies on reciprocity and social sanctions to provide a local public good. The OSP was one of the first organizations to arise in the formerly German territories. Not only did it precede state institutions, but it also performed some of the state’s key functions: protecting the population from bandits and fires, restoring damaged infrastructure, and socializing young men (Kuta Reference Kuta1987). The OSP was also prevalent across all Polish partitions and allowed to operate during the communist period.

To measure the prevalence of organizations that historically operated informally, I take advantage of the 1989 Law on Associations, which encouraged all OSPs to register in order to receive equipment, funds, and training. This contemporary indicator (Volunteer Fire Brigades per 10,000 people) is a reliable proxy for historic variation in the prevalence of OSPs because more than 90% of the currently registered OSPs existed prior to 1989 (Klon-Jawor 2013). I was able to establish the exact founding dates for many units by calling the local administration and the OSP units themselves, confirming that most OSPs in the formerly German territories emerged in the late 1940s.Footnote 7

A related observational implication of my theory is higher demand for third-party enforcement in more heterogeneous communities. Unfortunately, community-level measures of reliance on state institutions during the communist period are unavailable: State organizations were allocated based on administrative divisions and other potential indicators, such as the use of courts, exist only at the province level. In contemporary Poland, however, reliance on formal enforcement can be inferred from the decision of some municipalities to devote fiscal resources to the creation of a municipal guard, which employs professionals to provide security and supplement national police. Municipal guards now operate on the territory of approximately every sixth municipality and predominate in the resettled territories (see Figure A.4 in the Appendix). Here, I use the presence of the municipal guard (straż gminna) in 2007 (earliest available for all municipalities) as a proxy for reliance on third-party enforcement.

Greater demand for state-provided public goods increases the incentives to pay taxes and invest in state capacity. As discussed above, the introduction of municipal self-governments in 1990 allowed for the manifestation of local differences after decades of indirect taxation and centralized planning. Municipalities could set their own tax rates on immovable property, vehicles, and farming within the nationwide tax cap. Property tax, in particular, was levied on many constituents and amounted to a sizable proportion of local revenue.Footnote 8 Collecting property tax from physical persons required considerable bureaucratic resources because individual taxpayers were exempt if they did not receive tax assessments. This discussion suggests two related measures of local fiscal capacity: (1) Property Tax Rate, computed as 100 × TaxRevenue/(TaxRevenue + TaxExemptions), following Swianiewicz (Reference Swianiewicz1996); and (2) Property Tax Revenue per capita. Both are averaged for 1993–95, the period in which local tax collection began diverging. Property Tax Rate captures willingness to tax, while Property Tax Revenue combines willingness and ability to tax. Conditional on the differences in the tax base, I expect both indicators to increase with migrant heterogeneity.

It bears noting that although the theory predicts that heterogeneous and homogeneous communities will resort to divergent enforcement strategies already in the 1950s and 1960s, I am able to test these predictions quantitatively only for indicators measured in the 1990s or later. While the passage of time biases against finding nonzero effects for these dependent variables, it also prevents me from testing some of the intermediate relationships between the hypothesized subnational differences in state capacity at different levels of cultural heterogeneity and levels of private economic activity during the communist period.

Economic Outcomes

I argue that greater reach of the state facilitates private economic activity only under “good” state institutions. Under state socialism, reliance on formal institutions in heterogeneous communities carried no economic advantages while greater effectiveness of informal enforcement mechanisms in homogeneous communities may have facilitated economic exchange in the shadow economy.

Informal transactions are not directly observable, and the existing approaches to measuring the shadow economy cannot be replicated at the micro level. Instead, I measure the rates of legal private economic activity using data on (1) population engaged in Socialized Economy, regardless of occupation, and in (2) Private Handicrafts as well as (3) the number of Shops Footnote 9 per 1,000 people in 1980–82 (earliest available). Even such legal forms of economic activity typically depended on informal connections (Kochanowski Reference Kochanowski2010). I also use the number of (4) TV-sets and (5) Phones per 1,000 people for the same time period as an indicator of wealth. All of these measures are indirect, and some (Private Handicrafts) are likely measured with error. My theory predicts a positive relationship between Migrant Diversity and employment in the socialized economy and a negative relationship between Migrant Diversity and the remaining four indicators.

To measure private economic activity under the market economy, I use data on Private Enterprises (per 1,000 people) and per capita Personal Income Tax. The earliest measures are available from 1995 and 1993, respectively. Unlike property tax, personal income tax has the same rate across all municipalities and closely tracks incomes.Footnote 10 It is generally collected by employers, which lowers but does not completely eliminate concerns about measurement error due to variation in tax compliance. I expect a positive relationship between historical levels of migrant heterogeneity and post-1989 economic outcomes.

Covariates

Estimating the effects of Migrant Diversity on economic activity is challenging because it is possible that heterogeneous migrants settled in economically more developed areas. There were some instances of skilled migrants from far-flung regions assigned to more industrial localities to facilitate production. Thus, I use the proportion of population employed in industry (Share in Industry) collected from the 1939 German census as a proxy for industrial potential.Footnote 11 The variable explains 12% of the variance in Migrant Diversity (see Appendix B.2).

Localities near the railway were easier to reach for migrants from any point of origin. Proximity to the railway also facilitated state control and economic development, biasing in favor of the main hypotheses. Thus, I account for distance to the nearest railway station, measured in 1948, which explains 9% of the variance in Migrant Diversity.

Distance to post-1945 international borders is another possible confounder. For security reasons, military families were encouraged to settle in the border regions, while migrants of certain origin (such as Lemkos) were prohibited from settling near the borders. Distance to the border also had divergent economic implications before and after 1989. Thus, I calculated the distance to the international border, in kilometers (km), from the centroid of each municipality, which is negatively correlated with Migrant Diversity and explains 11% of the variance.

In rural areas, the resettlement process was influenced by the presence of large German estates, transformed into state-owned farms during the early 1950s.Footnote 12 State farms attracted primarily landless migrants from Central Poland and, in addition to employment, provided important social services during the communist period. After 1989, the closure of state farms increased unemployment rates and generated a host of social ills. However, the location of large German estates, proxied by Share Farms over 100 ha, is only weakly correlated with Migrant Diversity.

I measure access to state public goods provision as distance (in km) between the center of each municipality and the county seat, which contained state police and fire brigade, hospitals, and courts (Distance to County Seat).Footnote 13 Other covariates are population size, as informal enforcement weakens with the size of a community, and the share of the urban population in 1948, when the population transfers were completed. I also collected data on the gender and age of migrants, which do not vary with Migrant Diversity.

Sources and descriptive statistics for all historic and contemporary variables used in the analyses are presented in the Online Appendix (Sections B.1 and B.2). As shown in the Appendix, most correlations between Migrant Diversity and socioeconomic covariates are near zero, which speaks to the arbitrariness of migrant assignment. Nevertheless, I include all covariates that predict some variation in Migrant Diversity or bias in favor of my hypotheses. Regression models also include fixed effects for pre-WWII German districts (Regierungsbezirke), which varied in infrastructure and industrial potential.

MAIN RESULTS

Enforcement Strategies and Fiscal Capacity

My theory predicts a negative relationship between heterogeneity and the prevalence of volunteer fire brigades, which provide a local public good through bottom-up collective action, and a positive relationship between heterogeneity and the prevalence of municipal guards, a contemporary organization for the provision of security through taxation. I test these predictions in Table 2.

TABLE 2. Migrant Diversity, Organizations for Public Goods Provision, and Fiscal Capacity

+ p < 0.1; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.

Model 1 in Table 2 regresses Volunteer Fire Brigades (per 10,000 people) on Migrant Diversity and covariates. The coefficient on Migrant Diversity is negative and significant: Diverse migrant communities have fewer OSPs than homogeneous migrant communities. A change in heterogeneity from zero (homogeneous) to 0.66 (heterogeneous, comparable to a community with three equally sized culturally distinct groups) predicts a decrease in the number volunteer fire brigades by 2.8 per 10,000 people, equivalent to approximately two thirds of a standard deviation, when comparing communities within German districts. The coefficient on the Share of Migrants is negative but does not reach statistical significance.

Model 2 in Table 2 regresses the presence of a Municipal Guard on Migrant Diversity and covariates. The coefficient on Migrant Diversity is positive and statistically significant: Predicted probability of establishing a municipal guard in most heterogeneous migrant communities (Migrant Diversity = 0.66) is approximately 10% greater than in homogeneous communities (Migrant Diversity = 0), as shown in Figure 4. The estimate is conditional on the proximity to the state police and other covariates and captures variation only within formerly German districts. The coefficient on the Share of Migrants is also positive and statistically significant. The predicted probability of creating a municipal guard increases from 3% to 8% as the share of migrants rises from 50% to 100%, which is consistent with the greater need for state enforcement following the disruption of social ties.

FIGURE 4. Predicted Probability of Establishing a Municipal Guard at Different Levels of Migrant Diversity (Left) and Density of Volunteer Fire Brigades (Right). Based on Models 2 and 3 from Table 2

Model 3 examines whether public goods provision through informal enforcement predicts lower demand for public goods provided through taxation by regressing Municipal Guard presence on the density of volunteer fire brigades. The coefficient on Volunteer Fire Brigades is negative and statistically significant. The model suggests the predicted probability of establishing a municipal guard is 3.4% lower, on average, in communities with the average prevalence of volunteer fire brigades (4.17 per 10,000 people) than in communities without any (see Figure 4).

Did greater demand for state-provided public goods affect tax policy and revenues in historically homogeneous and heterogeneous communities? Models 4–7 in Table 2 explore the divergence of fiscal policies in 1993–95, the period when municipalities began determining their own revenues and expenditures. First, I regress property tax rates and revenues on Migrant Diversity and covariates. In Model 4, with Property Tax Rate as a dependent variable, the coefficient on Migrant Diversity is positive but does not reach statistical significance; the coefficient on Share Migrants is negative and significant at the 10% level.Footnote 14 Thus, contrary to expectations, tax rates are similar in communities at different levels of Migrant Diversity. However, in Model 6, with ln(Property Tax Revenue) as a dependent variable, the coefficient on Migrant Diversity is positive and significant at the 5% level. This model suggests that predicted revenues from property tax in the most heterogeneous communities exceed those in the most homogeneous communities by 85 Złoty per capita, on average, an effect that is equivalent to a quarter of the standard deviation in the dependent variable. By contrast, the coefficient on Share Migrants does not reach statistical significance in these models and changes signs, which suggests that the observed differences in fiscal capacity are due to heterogeneity rather than to the uprooting of population.

Models 5 and 7 examine intermediate relationships between voluntary provision of public goods, on the one hand, and investment in fiscal capacity, on the other hand. Regression analysis suggests that both property tax rates and revenues were lower in localities with greater voluntary provision of public goods, proxied by the density of volunteer fire brigades. Thus, culturally homogeneous communities that are effective at informal cooperation appear to have lower demand for state-provided public goods and are less likely to invest in fiscal capacity.

I replicate the results from the main linear models in Table 2 using OLS with weights from nonparametric CBGPSFootnote 15 and demonstrate their robustness to unobserved confounding (see Appendices D.2 and D.3).

Higher prevalence of volunteer fire brigades in historically more homogeneous communities mirrors the conclusions in the literature on the importance of homogeneity for voluntary provision of public goods (e.g., Habyarimana et al. Reference Habyarimana, Humphreys, Posner and Weinstein2009; Miguel and Gugerty Reference Miguel and Gugerty2005). At the same time, the positive effects of Migrant Diversity on the creation of the Municipal Guards and on Property Tax Revenue raise questions about the broader economic implications of lower levels of voluntary cooperation in heterogeneous settings. In particular, the results suggest that homogeneous communities that are effective at collective action may have lower demand for state-provided public goods and thus lower incentives to invest in state capacity, an important determinant of long-run economic growth.

Economic Outcomes before 1989

My theory predicts that greater reach of the state in heterogeneous communities carried few economic advantages and may have even hampered private entrepreneurship during state socialism. By contrast, informal norms and networks, historically stronger in homogeneous communities, created additional opportunities for economic exchange and provided access to scarce resources. Regressions in Table 3 explore the observable implications of the theory using economic outcomes measured in the early 1980s, when private entrepreneurship was legal, but market-supporting formal institutions remained inadequate.

TABLE 3. Migrant Diversity and Economic Outcomes (per 1,000 People) at the Municipality Level in 1980–82. OLS Regression

+ p < 0.1; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.

The coefficient on Migrant Diversity is not statistically significant in the regression models that focus on employment in the Socialized Economy or Private Handicrafts when all covariates are included (Models 1 and 2). Migrant Diversity also does not predict the prevalence of TVs per 1,000 people after conditioning on covariates (Model 5). The coefficient on Migrant Diversity is negative and statistically significant at the 5% level in Models 3 and 4, which regress Shops and Phones on diversity and historic covariates, however. These two models imply that homogeneous (Migrant Diversity = 0) communities have an additional shop and 4.5 more phones per 1,000 people than most heterogeneous communities (Migrant Diversity = 0.66), which is slightly below half a standard deviation for shops and one-fifth of a standard deviation for phones. The coefficient on Share Migrants changes signs depending on the model. Models 1 and 2 suggest lower levels of private economic activity and higher levels of state employment in migrant communities, relative to the indigenous communities in the formerly German territories. Models 4 and 5 imply greater wealth in communities with higher shares of migrant population.

I examine the robustness of the coefficients on the main explanatory variable, Migrant Diversity, to using the npCBGPS methodology in Appendix D.2. The magnitude and statistical significance of the coefficient on Shops increases, while the coefficient on Phones is attenuated and loses statistical significance. The relationship between Migrant Diversity and Shops and Phones is relatively robust to the unobserved confounding, as discussed in Appendix D.3.

In sum, regression analysis shows that homogeneous communities had slightly more shops and phones per capita than diverse communities in the 1980s, on average. At the same time, homogeneity was not associated with the prevalence of TV sets or with employment in the private and socialized sectors. The interpretation of the economic consequences of Migrant Diversity clearly depends on measurement choices. Unfortunately, data do not allow for studying the extent of the shadow economy across communities at different levels of diversity. It is safe to conclude from the analysis above, however, that heterogeneity produced no economic advantages during the communist period and that, if anything, homogeneous communities were slightly better off economically than heterogeneous communities.

Economic Outcomes after 1989

I further argue that after 1989, greater reach of the state in historically heterogeneous communities contributed to higher entrepreneurship and higher incomes. Figure 5 presents the relationship between migrant heterogeneity and gross income per capita as well as gross domestic product per capita, measured in 1995, at the province level. The N = 14 is small, but there is a clear positive relationship between these economic indicators and migrant diversity.

FIGURE 5. Gross Income and GDP in Provinces Affected by Population Transfers

I explore the relationship between heterogeneity and economic outcomes at the municipal level using data on entrepreneurship rates and personal income tax per capita in Table 4. As noted earlier, tax rates on personal incomes do not vary across municipalities, so the latter measure closely tracks municipal differences in individual earnings. All regressions include a full set of covariates, district fixed effects, and control for spatial autocorrelation where it is present.Footnote 16 Model 1 indicates that Migrant Diversity does not predict Personal Income Tax in 1993, the earliest year for which data exist and a year after the tax was introduced. Income differences across resettled communities gradually widened over time, however. The coefficient on Migrant Diversity reaches statistical significance in 1995 and increases in magnitude in subsequent years (Models 2–4). The results for 1995 imply that homogeneous communities collected 13 Zł. less in personal income tax, on average, than most heterogeneous communities, equivalent to more than half a standard deviation in income tax during this period. This is a conservative estimate within regions that accounts for pretreatment covariates and spatial autocorrelation. In 2000, the predicted differences in personal income tax collected from homogeneous and most heterogeneous communities reach 21 Zł, or 40% of a standard deviation in income tax for that year (Model 4). Thus, the differences between homogeneous and heterogeneous communities widen as overall income inequality rises. By contrast, the coefficient on Share Migrants is negative in three out of four models and reaches statistical significance only in Models 2 and 3, for 1995 and 1998 outcomes. This may be because the indigenous population could legally work in Germany during this period, enabling higher earnings.

TABLE 4. Diversity and Personal Income Tax per Capita (1–4) and Private Entrepreneurship (5–7). OLS Regression

+ p < 0.1; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.

Models 5–7 show that Migrant Diversity also predicts higher rates of private entrepreneurship. Substantively, Model 5 implies that within a formerly German administrative district and accounting for all pretreatment covariates, an increase in historical levels of heterogeneity from zero (homogeneous) to 0.66 (most heterogeneous) predicts an increase in private enterprises by five per 1,000 people, equivalent to nearly a quarter of a standard deviation in the outcome. These differences remain statistically significant and substantively meaningful, but decrease slightly over time. By 2000, the predicted differences between most homogeneous and most heterogeneous communities increase to eight enterprises per 1,000 people, on average. Table A.10 in the Appendix shows that the coefficient on Migrant Diversity nearly doubles in size when excluding cities, which have both high levels of cultural diversity and private entrepreneurship. One possible interpretation is greater geographic mobility of urban population. Another is that cultural heterogeneity matters more in rural areas, where interactions with outgroups and the state are otherwise less frequent. There is no statistically significant relationship between Share Migrants and entrepreneurship rates.

Table A.11 in the Appendix explores the relationships between voluntary provision of public goods, taxation, and economic outcomes. All relationships are in the expected direction and statistically significant: The prevalence of volunteer fire brigades and tax rates and revenues in the early 1990s are strong predictors of incomes and entrepreneurship rates in subsequent years.Footnote 17

In Appendix D.2, I show that the magnitude of the coefficient on Migrant Diversity increases when the data are weighted to achieve full covariate balance at different levels of treatment. Sensitivity analysis in Appendix D.3 also demonstrates that findings are robust to unobserved confounding within plausible sensitivity parameters.

EXPLORING THE MECHANISMS

Overall, the results indicate that historically diverse migrant communities perform better in a market economy. Combined with the evidence that before 1989 Migrant Diversity was a weak predictor of private economic activity, the results support the argument that economic implications of heterogeneity depend on the broader institutional environment. The question remains, however, whether local differences in the state–society relationship mediate the relationship between heterogeneity and private economic activity.

To test this hypothesis for post-1989 outcomes, I follow Acharya, Blackwell, and Sen (Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2016) in using sequential g-estimation. Under certain assumptions, this approach allows for estimating the controlled direct effect of heterogeneity, with the hypothesized mediator variables—voluntary provision of public goods and fiscal capacity—fixed at the same level for all units (see Appendix D.4).Footnote 18 Stage one of sequential g-estimation includes Migrant Diversity, pretreatment confounders, and the following intermediate confounders for the relationship between heterogeneity and informal institutions: the number of schools and state farms, employment in the socialized sector, population in private handicrafts, shops, TV-sets, and phones per 1,000 people (some of these variables were used as outcomes in the previous analysis). This analysis is used to demediate the post-communist economic outcomes by subtracting the variation caused by the mediator. Stage two regresses the demediated outcomes on Migrant Diversity and pretreatment confounders.

Figure 6 presents the coefficients on Migrant Diversity from the baseline models of economic outcomes measured in 1998 with only pretreatment covariates (see Table 4 Models 3 and 6) and from the second stage of sequential g-estimation using the prevalence of Volunteer Fire Brigades or Property Tax Revenue as mediators (see Appendix D.4). For demediated entrepreneurship rates, the coefficient on Migrant Diversity decreases in magnitude and loses statistical significance. The changes in magnitude are largest for Property Tax Revenue. This suggests that subnational differences in fiscal capacity indeed mediate the relationship between heterogeneity and private entrepreneurship. By contrast, in models with demediated Personal Income Tax as the outcome, the coefficient on Migrant Diversity decreases only slightly and remains statistically significant. This suggests that Migrant Diversity may affect personal incomes through other channels, such as gains from specialization and trade that could be realized following the transition to the market.

FIGURE 6. Coefficient on Migrant Diversity and 95% Confidence Intervals from the Baseline Models and the Second Stage of the Sequential G-Estimation

An additional empirical implication of the argument is better governance in historically more heterogeneous communities. Most governance indicators exist only at the national or highly aggregated subnational level. For example, the Quality of Government Institute data cover 16 Polish regions, only six of which are located in the formerly German territories. In Appendix E, I analyze data on problems doing business from the BEEPS (EBRD-World Bank 2005) survey using multilevel regression analysis. I find that heterogeneity predicts a lower probability of reporting the inadequate “Functioning of the judiciary” or “Tax administration,” “Corruption,” and “Organized crime” as obstacles to doing business. While far from definitive, since subjective assessments of obstacles to doing business could reflect perceptions of economic outcomes rather than actual institutional quality, the analysis suggests better governance in historically more heterogeneous communities.

ALTERNATIVE EXPLANATIONS

Persistent Cultural Differences

Migrants often bring attitudes toward formal and informal institutions as well as human capital and entrepreneurial initiative with them. In the Polish case, migrants from different regions differed in their institutional heritage. Relatedly, migration experiences varied: Some were forced to relocate while others selected into migration. These factors may have influenced migrants’ attitudes toward the state or their economic behavior. For example, Becker et al. (Reference Becker, Grosfeld, Grosjean, Voigtländer and Zhuravskaya2018), who also examine the effects of post-war population transfers in Poland, show that although migrants from different regions did not differ in their education levels before WWII, experiencing forced displacement incentivized the descendants of migrants from the USSR to increase their investment in human capital, a mobile asset.

Could the presence of a specific cultural group, rather than the diversity of the migrant population, explain the differences in the local provision of public goods or economic outcomes at the municipal level? The prevalence of each group varied by region, with more migrants from Central Poland settling in the north and more migrants from the USSR settling in the south. Thus, including fixed effects for German districts helps address the concern that the main findings are driven by cultural differences rather than the extent of cultural heterogeneity. As an additional test, I regress the main social and economic outcomes on the shares of migrants from each region. Analysis in Appendix F.1 shows that while cultural differences do matter for some social and economic outcomes, they cannot provide a consistent explanation for all of the findings in the article. Furthermore, the main results hold when controlling for the origins of the dominant group in each municipality.

Human Capital and Skills

Could differences in human capital or perhaps the complementarity of skills resulting from divergent migration experiences explain the economic success of diverse resettled communities following the transition to a market economy?

While detailed occupational data are lacking, the 1978, 1988, and 2002 national censuses contain data on education at the municipal level. If the differences in education among diverse and homogeneous migrant communities existed in 1948, they should still be visible in the 1978 census and may either fade away or increase in subsequent periods. Regressions in Appendix F.2 show no statistically significant differences in education across different levels of heterogeneity in 1978 or 1988, but the coefficient on Migrant Diversity is a positive and significant predictor of education levels in 2002. This suggests that higher state capacity and/or greater economic prosperity in historically heterogeneous communities increased human capital, but not the reverse.

Research on positive economic effects of heterogeneity also emphasizes the variety of ideas and abilities that drive productivity and innovation (e.g., Alesina, Harnoss, and Rapoport Reference Alesina, Harnoss and Rapoport2016; Bove and Elia Reference Bove and Elia2017; Ortega and Peri Reference Ortega and Peri2014). These studies measure the diversity of skills as heterogeneity of migrants’ origins, a measure equivalent to Migrant Diversity. They also assume that generational turnover weakens returns to diversity. For example, Alesina, Harnoss, and Rapoport (Reference Alesina, Harnoss and Rapoport2016, 102) state that unlike “people of different ethnic or genetic origins who were born, raised and educated in the same country,” “people born in different countries are likely to have been educated in different school systems, learned different skills, and developed different cognitive abilities.” Accordingly, they find that birthplace diversity in 1990—but not in 1960—affects output in 2000. Alesina, Harnoss, and Rapoport (Reference Alesina, Harnoss and Rapoport2016, 120) interpret this as evidence that diversity increases productivity “primarily through first-generation effects.” By contrast, this article finds that diversity of migrants in 1948 predicts economic outcomes in the 1990s, when the labor force in western and northern Poland consisted largely of second- and third-generation migrants, born in Poland and subjected to homogenizing communist schooling. While the immigrants’ children inherit their skills and abilities, generational change should produce convergence in productivity across homogeneous and heterogeneous communities over time. Nevertheless, the residual heterogeneity of skills in historically heterogeneous localities may still explain their superior economic performance under a market economy, which enabled gains from specialization and trade, a possibility also suggested by the results from sequential g-estimation for the personal income tax.

State Policies

While it is generally agreed that the communist government ruled in a centralized manner and neglected local needs, it is possible that greater resources flowed to more heterogeneous migrant communities with the aim of facilitating integration and reducing social tensions. Regressions in Appendix F.4 show that heterogeneity does not predict higher prevalence of public schools and libraries, employment in the state sector, or the size of municipal budgets and compensatory subsidies from the central government during the communist period.

Sorting

It is possible that migrants from the initially more heterogeneous communities gradually sorted into more homogeneous communities, which were better at voluntary public goods provision. This dynamic could explain the post-1989 reversal of fortunes. Analysis in Appendix F.5 rejects this explanation. Regression results indicate that more people are moving into heterogeneous communities than into homogeneous communities. Thus, rather than becoming more homogeneous over time, such communities might be becoming even more diverse, a pattern also consistent with the greater openness to outsiders due to weaker informal networks.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The case of population transfers in the aftermath of WWII provides us with an important opportunity to examine the implications of cultural diversity for long-run social and economic development. Using original micro-level data on the origins of migrants resettled in the formerly German territories, I show that diversity does not exert a persistently negative effect on social and economic development. Less successful at voluntary public goods provision, communities settled by heterogeneous migrants made greater investments in fiscal capacity and registered higher incomes and greater entrepreneurship in a market economy than communities settled by homogeneous migrants.

Intriguingly, economic differences between communities at different levels of cultural heterogeneity were negligible prior to 1989—though data do not allow for examining shadow economic transactions during state socialism—but became visible in the 1990s, following the strengthening of state institutions for the protection of private property and enforcement of contracts. The analysis thus suggests scope conditions for the negative effects of cultural heterogeneity on public goods provision and private economic activity: low state capacity and/or predatory state institutions, supporting conclusions in Gao (Reference Gao2016), Alesina and La Ferrara (Reference Alesina and La Ferrara2005), and Miguel (Reference Miguel2004).

I advance this research agenda by distinguishing between the characteristics of the “rules of the game” at the national level and subnational variation in the state’s ability to enforce its rules. I propose that the latter can be endogenous to societal characteristics. More specifically, the very weakness of informal social norms and networks in heterogeneous settings increases the demand for state enforcement and thus facilitates the accumulation of state capacity over time. Historically, the disruption of informal norms and networks and the formation of linkages between the state and society have been crucial stages in state and nation building (Migdal Reference Migdal1988). Scholars have also linked the need to mitigate the adverse effects of social fragmentation in diverse populations to the creation of more elaborate and hierarchical institutions (Galor and Klemp Reference Galor and Klemp2017).

In emphasizing that heterogeneity may affect economic outcomes indirectly, by changing economic actors’ relations with the state, I offer an explanation that is distinct from but complementary to the emphasis on the variety of skills and/or changes in human capital as the drivers of innovation and productivity in heterogeneous societies (Alesina, Harnoss, and Rapoport Reference Alesina, Harnoss and Rapoport2016; Bove and Elia Reference Bove and Elia2017; Ortega and Peri Reference Ortega and Peri2014). My findings support the conclusions of the emerging scholarship on how immigrants affect institutions in the receiving states. Researchers have found that immigrants do not weaken and may even improve the host countries’ institutional environments (Clemens and Pritchett Reference Clemens and Pritchett2016; Padilla and Cachanosky Reference Padilla and Cachanosky2018; Pavlik, Padilla, and Powell Reference Pavlik, Padilla and Powell2018), including by lobbying and voting for better economic policy (Clark et al. Reference Clark, Lawson, Nowrasteh, Powell and Murphy2015; Nowrasteh, Forrester, and Blondin Reference Nowrasteh, Forrester and Blondin2018; Powell, Clark, and Nowrasteh Reference Powell, Clark and Nowrasteh2017) or by increasing the natives’ investments in compulsory schooling and other nation-building tools (Bandiera et al. Reference Bandiera, Mohnen, Rasul and Viarengo2018). I propose that in addition to these channels, migrants who stem from different institutional backgrounds are more likely to rely on host-country institutions, which act as a common denominator in culturally heterogeneous settings. Empirical evidence presented here does not definitively test this claim due to data limitations. Additional research is needed to conclusively separate the two channels through which immigration and heterogeneity may advance economic performance: the improvements in the depth and quality of state institutions, on the one hand, and the gains from specialization and skill complementarities, on the other.