Introduction

Glyphosate, a nonselective herbicide, is the most widely used herbicide worldwide, due to its use in glyphosate-resistant (GR) crops (Duke and Powles Reference Duke and Powles2008). Resistance to glyphosate was thought unlikely to develop because of the critical role of the shikimate pathway in plant function, the high conservation of the EPSPS binding domain, and inability of plants to detoxify glyphosate (Bradshaw et al. Reference Bradshaw, Padgette, Kimball and Wells1997). However, with persistent broadscale use, resistance to glyphosate has evolved in 36 weed species, including common ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia L.), hairy fleabane (Erigeron bonariensis L.), horseweed (Erigeron canadensis L.), goosegrass [Eleusine indica (L.) Gaertn.], Italian ryegrass [Lolium perenne L. ssp. multiflorum (Lam.) Husnot], rigid ryegrass (Lolium rigidum Gaudin), kochia [Bassia scoparia (L.) A. J. Scott], tall waterhemp [Amaranthus tuberculatus (Moq.) J. D. Sauer], and Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri S. Watson) in North America (Heap Reference Heap2017).

To date, resistance to glyphosate in weeds has been reported to be primarily conferred either by target-site (TSR) or non–target site (NTSR) mechanisms in the EPSPS gene (Fernández-Moreno et al. Reference Fernández-Moreno, Alcantara-de la Cruz, Cruz-Hipólito, Rojano-Delgado, Travlos and De Prado2016; Shaner et al. Reference Shaner, Lindenmeyer and Ostlie2012). NTSR mechanisms with respect to glyphosate include reduced absorption and translocation (Fernández-Moreno et al. Reference Fernández-Moreno, Bastida and De Prado2017; Vila-Aiub et al. Reference Vila-Aiub, Balbi, Distéfano, Fernández, Hopp, Yu and Powles2012), increased vacuolar sequestration (Ge et al. Reference Ge, d’Avignon, Ackerman, Collavo, Sattin, Ostrander, Hall, Sammons and Preston2012), degradation to nontoxic compounds (Rojano-Delgado et al. Reference Rojano-Delgado, Cruz-Hipolito, De Prado, de Castro and Franco2012), and rapid tissue necrosis followed by regrowth (Moretti et al. Reference Moretti, Van Horn, Robertson, Segobye, Weller, Young, Johnson, Douglas Sammons, Wang, Ge and d’Avignon2017; Van Horn et al. Reference Van Horn, Moretti, Robertson, Segobye, Weller, Young, Johnson, Schulz, Green, Jeffery and Lespérance2017). Reduced glyphosate translocation is the most commonly reported NTSR mechanism (Dinelli et al. Reference Dinelli, Marotti, Bonetti, Catizone, Urbano and Barnes2008; Feng et al. Reference Feng, Tran, Chiu, Sammons, Heck and CaJacob2004; Perez et al. Reference Perez, Alister and Kogan2004; Wakelin et al. Reference Wakelin, Lorraine-Colwill and Preston2004). TSR mechanisms confer resistance to glyphosate as a result of either changes in the herbicide-binding site in the EPSPS (Fernández-Moreno et al. Reference Fernández-Moreno, Alcantara-de la Cruz, Cruz-Hipólito, Rojano-Delgado, Travlos and De Prado2016; Yu et al. Reference Yu, Jalaludin, Han, Chen, Sammons and Powles2015) or overexpression of the EPSPS protein by gene amplification (Gaines et al. Reference Gaines, Zhang, Wang, Bukun, Chisholm, Shaner, Nissen, Patzoldt, Tranel, Culpepper, Grey, Webster, Vencill, Sammons, Jiang, Preston, Leach and Westra2010; Ribeiro et al. Reference Ribeiro, Pan, Duke, Nandula, Baldwin, Shaw and Dayan2014; Salas et al. Reference Salas, Dayan, Pan, Watson, Dickson, Scott and Burgos2012). Mutations at Pro-106 and Thr-102 of EPSPS endow low-level resistance to glyphosate and used to be the most commonly reported TSR mechanisms in GR weeds (Baerson et al. Reference Baerson, Rodriguez, Tran, Feng, Biest and Dill2002; Kaundun et al. Reference Kaundun, Dale, Zelaya, Dinelli, Marotti, McIndoe and Cairns2011; Ng et al. Reference Ng, Wickneswary, Salmijah, Teng and Ismail2004; Yu et al. Reference Yu, Cairns and Powles2007). Reduced translocation results in a higher level of resistance (7- to 11-fold) than the level of resistance (2- to 3-fold) afforded by the EPSPS mutations mentioned (Preston and Wakelin Reference Preston and Wakelin2008). Lately, the amplification of EPSPS has been reported as a TSR mechanism conferring moderate to high level of resistance in three Amaranthus species (Chandi et al. Reference Chandi, Milla-Lewis, Giacomini, Westra, Preston, Jordan, York, Burton and Whitaker2012; Chatham et al. Reference Chatham, Bradley, Kruger, Martin, Owen, Peterson, Mithila and Tranel2015; Gaines et al. Reference Gaines, Zhang, Wang, Bukun, Chisholm, Shaner, Nissen, Patzoldt, Tranel, Culpepper, Grey, Webster, Vencill, Sammons, Jiang, Preston, Leach and Westra2010; Nandula et al. Reference Nandula, Wright, Bond, Ray, Eubank and Molin2014), L. perenne (Salas et al. Reference Salas, Dayan, Pan, Watson, Dickson, Scott and Burgos2012), B. scoparia (Wiersma et al. Reference Wiersma, Gaines, Preston, Hamilton, Giacomini, Buell, Leach and Westra2015), and ripgut brome (Bromus diandrus Roth) (Malone et al. Reference Malone, Morran, Shirley, Boutsalis and Preston2016).

Amaranthus palmeri is highly competitive, has extremely rapid growth, high fecundity, and extended emergence behavior, which allows it to escape weed management tactics (Monks and Oliver Reference Monks and Oliver1988; Ward et al. Reference Ward, Webster and Steckel2013). It is the number one most troublesome and difficult-to-control weed in the United States (WSSA 2016). Amaranthus palmeri is among the most herbicide resistance–prone dicots, with resistance to six herbicide sites of action in the United States (Heap Reference Heap2017). Intensive use of glyphosate has resulted in the evolution of GR A. palmeri in 30 states, including Arkansas. Multiple resistance to glyphosate and acetolactate synthase (ALS) and protoporphyrinogen oxidase (PPO) inhibitors is increasing (Salas-Perez et al. Reference Salas-Perez, Burgos, Rangani, Singh, Refatti, Piveta, Tranel, Mauromoustakos and Scott2017), making weed management difficult. Although GR A. palmeri is widespread in Arkansas, the mechanisms involved are not yet known. This study was conducted to (1) survey the occurrence of EPSPS gene amplification and target-site mutation(s) among GR A. palmeri accessions from Arkansas and (2) determine the correlation of EPSPS copy number with resistance level to glyphosate.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material

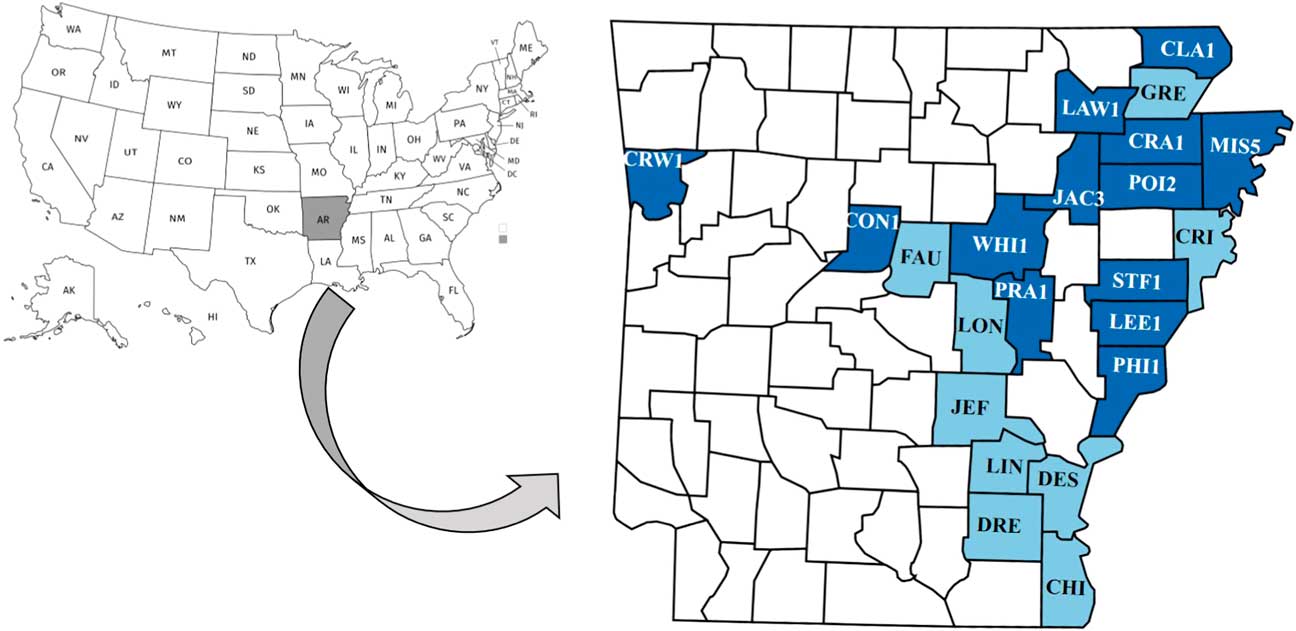

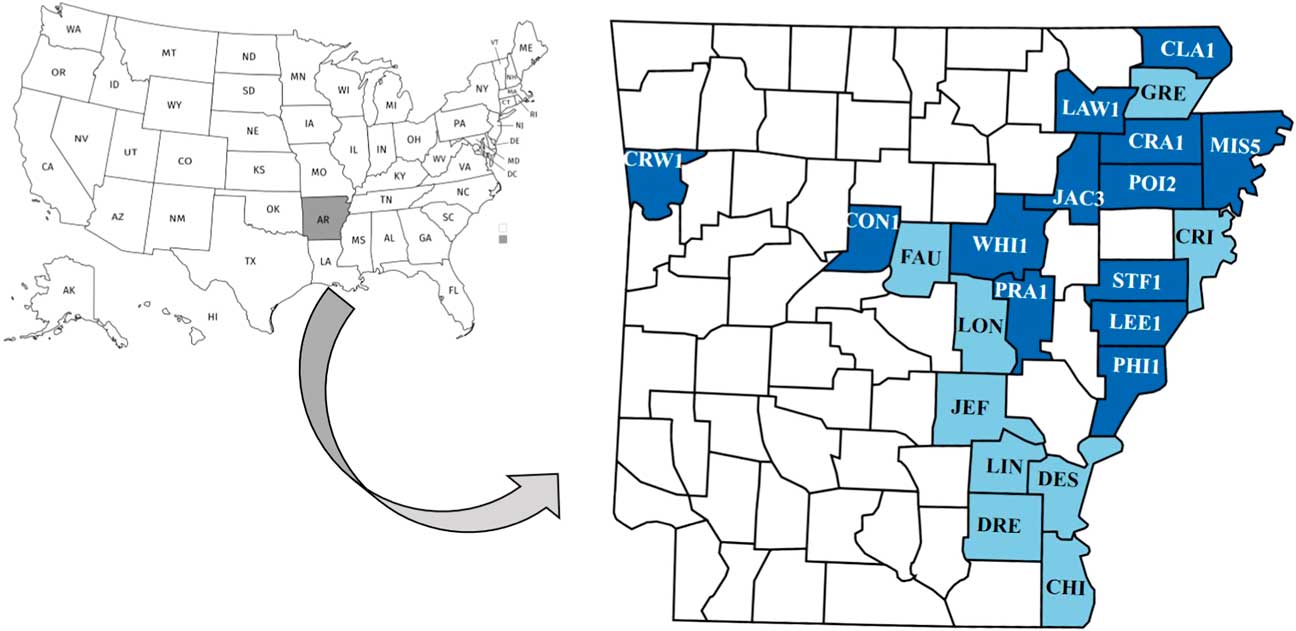

Amaranthus palmeri plants remaining in the fields at the end of the growing season were sampled in late summer between 2008 and 2014 from crop production fields in Arkansas, mostly cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) and soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.]. Inflorescences of at least 10 plants field−1 were collected (Burgos et al. Reference Burgos, Tranel, Streibig, Davis, Shaner, Norsworthy and Ritz2013), air-dried, and manually threshed. A composite seed sample from each field (hereafter referred to as an “accession”) was prepared by mixing 500 mg of seed plant−1. A total of 115 accessions were tested with glyphosate (unpublished data). Out of 115 accessions, 20 were selected from 13 counties (Figure 1) to represent a broad range of responses to glyphosate. These accessions included the susceptible standard (SS), which was collected from a field historically planted mostly with watermelon [Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.) Matsum. & Nakai] and vegetables.

Figure 1 Map of the U.S. state of Arkansas showing counties where Amaranthus palmeri accessions were collected between 2008 and 2014. The 20 selected accessions used in this research were from CLA (Clay), CON (Conway), CRA (Craighead), CRW (Crawford), JAC (Jackson), LAW (Lawrence), LEE (Lee), MIS (Mississippi), PHI (Phillips), POI (Poinsett), PRA (Prairie), STF (St Francis), and WHI (White) counties. The number of accessions selected per county is also indicated.

General Testing for Resistance to Glyphosate

The composite seed samples of 20 accessions were planted in 50-cell trays (Redway Feed Garden and Pet Supply, Redway, CA) filled with potting medium (Sunshine® Premix #1, Sun Gro Horticulture, Bellevue, WA). Plants were grown in a greenhouse with temperature maintained at 32/25±5 C day/night and a 16-h photoperiod. The experiment was set up as randomized complete block design with two replications (50 plants replication−1), with each tray being a replication with 1 seedling cell−1. The bioassay was conducted twice. Thus, 200 plants representing a field were treated with the recommended dose of glyphosate at 840 g ae ha−1 (Roundup PowerMax®, Monsanto, St Louis, MO). Seedlings, 7- to 10-cm tall, were treated in a spray chamber using a boom fitted with two 800067 flat-fan nozzles (TeeJet® spray nozzles, Spraying Systems, Wheaton, IL) delivering 187 L ha−1 at 269 kPa. Plants were labeled and leaf tissues were collected before herbicide treatment for use in succeeding experiments. At 21 d after treatment (DAT), each plant was evaluated visually for injury relative to the nontreated control. Injury was rated on a scale of 0% to 100%, where 0% and 100% represented no injury and complete death, respectively. Data were analyzed using ANOVA in JMP Pro v. 12 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Hierarchal clustering of accessions was done using injury and mortality data (S Singh, NR Burgos, V Singh, EAL Alcober, R Salas-Perez, V Shivrain, unpublished data).

Evaluation of Level of Resistance to Glyphosate

Twenty A. palmeri accessions were used in this study. Seeds of each accession were planted in 11 by 11 cm square pots filled with Sunshine® Mix LC1 potting soil (Sun Gro Horticulture Canada, Vancouver, BC, Canada). Seedlings (5 pot−1, 7- to 10-cm tall) of resistant accessions were treated with eight doses of glyphosate: 0, 110, 220, 420, 840, 1,680, 3,360, and 6,720 g ha−1; and the susceptible accessions were treated with 0, 27.5, 55, 110, 220, 420, 840, and 1,680 g ha−1. Glyphosate was applied following the procedure outlined in the previous section. The experiment was conducted in a randomized complete block design with six replications. The number of survivors and injury were evaluated at 21 DAT using the same scale described previously. Data were analyzed using SigmaPlot v. 13 (Systat Software, San Jose, CA). Dose–response data were subjected to nonlinear regression analysis and fit with a three-parameter log-logistic (Equation 1) to determine the glyphosate dose that would cause 50% and 90% control as follows:

where Y is the % injury; a is the asymptote; b is the slope of the line; c is the inflection point; and x is the glyphosate dose.

Determination of Relative EPSPS Gene Copy Number

After glyphosate application (840 g ha−1), tissues from surviving plants with injuries ranging from 10% to 70%, were collected at 21 DAT to determine the relative EPSPS gene copy number. For susceptible accessions, leaf tissues from nontreated plants were used. Leaf tissues were frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 C until processed. Genomic DNA was extracted from approximately 100 mg of leaf tissue using a modified CTAB protocol (Doyle and Doyle Reference Doyle and Doyle1990), quantified using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE), and checked for quality by gel electrophoresis.

The EPSPS gene copy number was determined by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) relative to the A36 gene, a RNA dead-box helicase from woolflower (Celosia trigina L.) (PI649298). This reference gene was used because the A. palmeri accessions were also resistant to ALS-inhibiting herbicides; should resistance involve any ALS amplification, it could result in underestimation of EPSPS gene copy. The ALS gene has been used by Gaines et al. (Reference Gaines, Zhang, Wang, Bukun, Chisholm, Shaner, Nissen, Patzoldt, Tranel, Culpepper, Grey, Webster, Vencill, Sammons, Jiang, Preston, Leach and Westra2010) and others as a reference to analyze the EPSPS gene copy number. The A36 primers were designed using Biolign and Primer 3 software from sequences of the Amaranthus genus: A36_F244 (5′TTGGAACTGTCAGAGCAACC3′) and A36_R363 (5′GAACCCACTT CCACCAAAAC3′). To amplify the EPSPS gene, the primer sets EPSF1 (5′ATGTTGGACGCT CTCAGAACTCTTGGT3′) and EPSR8 (5′TGAATTTCCTCCAGCAACGGCAA3′) designed by Gaines et al. (Reference Gaines, Zhang, Wang, Bukun, Chisholm, Shaner, Nissen, Patzoldt, Tranel, Culpepper, Grey, Webster, Vencill, Sammons, Jiang, Preston, Leach and Westra2010) were used. For the qPCR, 25-µl reactions were prepared using 12.5 µl of Bio-Rad iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), 1 μl of the forward and reverse primers (10 μM), and 10 ng gDNA. The thermoprofile consisted of 15 min denaturation at 95 C, 40 cycles of 95 C for 30 s, and a single cycle of 60 C for 60 s. This program was followed by a melt-curve analysis of 81 cycles at 55 C for 30 s (Chandi et al. Reference Chandi, Milla-Lewis, Giacomini, Westra, Preston, Jordan, York, Burton and Whitaker2012). A negative control consisting of primers with no template DNA was included. No amplification products were observed in negative control reactions. Data were analyzed using a modified 2−ΔΔCt method to express genomic copy number of EPSPS relative to A36, as ΔCt=(Ct A36 − Ct EPSPS). The relative increase in genomic EPSPS copy number was expressed as 2ΔCt (Gaines et al. Reference Gaines, Shaner, Ward, Leach, Preston and Westra2011). Each population had four biological replicates, and each sample was run in triplicate (for each primer pair).

Partial Sequencing of EPSPS

A 150-bp fragment of the EPSPS gene was sequenced from five GR A. palmeri accessions (4 plants accession−1) that did not have EPSPS amplification to determine whether any of the known resistance-conferring amino acid substitutions at Thr-102 or Pro-106 were present. The EPSPS gene of SS was also sequenced. Forward and reverse primers (EPSPSF: 5′CCAAAAGGGCAGTCGTAGAG3′; EPSPSR: 5′ACCTTGAATTTCCTCCAGCA3′) designed by Varanasi et al. (Reference Varanasi, Godar, Currie, Dille, Thompson, Stahlman and Jugulam2015) were used to amplify a short fragment of EPSPS from genomic DNA. The 25-µl PCR reaction consisted of 12.5 µl 2X PCR master mix (Takara Bio USA, Mountain View, CA), 2.5 µl of both the forward and reverse primers (5 µM), 4 µl gDNA (50 ng µl−1), and 3.5 µl of water. The PCR was performed with the following conditions: initial denaturation at 95 C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 C for 30 s, annealing at 53.5 C for 45 s, final extension at 72 C for 7 min, and infinite hold at 4 C. The PCR product was run on a 1% agarose gel to verify the fragment size and purified using a NucleoSpin® Gel and PCR Clean-up kit (Takara Bio USA). The purified DNA was sequenced with the same primers used for PCR and were prepared with ABI BigDye® Terminator v. 3.1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) for sequencing at Institute for Plant Genomics and Biotechnology, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX. The nucleotide sequences were aligned using BioEdit software (Hall Reference Hall1999). Sequences from SS and GR plants were aligned to the EPSPS sequences of A. palmeri (FJ861242.1 and FJ861243.1) and A. tuberculatus (FJ869881.1) from GeneBank.

Results and Discussion

Response of Amaranthus palmeri to Glyphosate

The A. palmeri accessions used in this study differentiated into three clusters based on frequency of survivors and levels of injury from treatment with 840 g ha−1 glyphosate (Table 1). The first cluster consisted of seven susceptible accessions, including accession SS, with mortality and injury averaging 98% and 99%, respectively, on the remaining plants at 3 wk after treatment. All individuals of the SS accession died at this dose. The second cluster consisted of six slightly resistant accessions with 63% mortality and an average injury of 80%. This cluster was distinct from the susceptible cluster, exhibiting an early phase of selection for glyphosate resistance. The third cluster was composed of seven highly resistant accessions with an average mortality of 32% and 50% injury. The majority of survivors in this cluster incurred 0% to 10% injury. Of the 200 plants accession−1 treated with the 1X rate of glyphosate, the most resistant survivors (0% to 10% injury) were from Conway (112 plants), Mississippi (91), Lee (87), Poinsett (75), and St Francis (70) counties (Table 2). One accession from Mississippi County had the most number of survivors and the lowest injury (5% to 10%). These fields had been planted with GR crops for at least a decade. Field population–level resistance is expected to increase with time of exposure to glyphosate. Once a resistant individual is selected, and the individual is fit enough to compete and survive, each selection cycle is expected to increase the frequency of resistant alleles in the population, leading to the evolution of a highly resistant population.

Table 1 Response of selected Amaranthus palmeri accessions to glyphosate (840 g ae ha−1), Arkansas, USA.

a Accessions were selected to represent different levels of resistance. Abbreviations: CL, Clay; CON, Conway; CRA, Craighead; JAC, Jackson; LAW, Lawrence; LEE, Lee; MIS, Missisippi; PHI, Phillips; POI, Poinsett; PRA, Prairie; STF, St. Francis; WHI, White.

b Plants were sprayed when 7- to 10-cm tall and evaluated 21 d after herbicide application.

c Survivors were categorized based on visible injury: HR, highly resistant (0–10% injury); MR, moderately resistant (31–60% injury); R, resistant (11–30% injury); S, sensitive (90–100% injury); and SR, slightly resistant (61–89% injury).

d Susceptible standard accession.

Table 2 ED50 and ED90 values for selected glyphosate-resistant Amaranthus palmeri accessions (7- to 10-cm tall) from Arkansas, USA.

a ED50 (effective dose to cause 50% injury) and ED90 (effective dose to cause 90% injury) values. Values in parentheses represent SEs. ND (not determined): the highest rate applied resulted in less than 90% control of the accession.

b Resistance levels (R/S) were calculated using the estimated doses relative to the susceptible standard.

c Susceptible standard accession.

Resistance Level to Glyphosate

The glyphosate dose that killed 90% (ED90) of SS was 193 (±16) g ha−1, about one-fourth of the field use rate (Table 2). Other accessions in the susceptible cluster also had low ED90 values. The ED90 values for accessions in the slightly resistant group (Cluster 2) approached the 1X rate of glyphosate; such field populations may have already harbored a few resistant individuals that could tolerate the field use rate. Accessions represented by Cluster 2 do not pose an immediate economic problem, but without mitigation, will adapt to become a problematic weed population perhaps in three or four more cycles of selection. This was demonstrated by the progression of resistance to PPO-inhibitor herbicides after first detection (Salas et al. Reference Salas, Burgos, Tranel, Singh, Glasgow, Scott and Nichols2016). Thus, glyphosate is still effective on some populations but should be monitored closely. Some resistant accessions (CLA11-A; CON09-A; MIS11-A,-B,-C; MIS08-B; PHI08-A; and STF08-A) could not be controlled 90% by the highest dose tested; therefore, the ED90 value was not determined. The resistance levels varied widely among GR accessions (i.e., effective dose to cause 50% injury [ED50] values from 969 g ha−1 to 1,459 g ha−1). Large variation in resistance levels to glyphosate among field populations of A. palmeri indicate the occurrence of different resistance mechanisms or different phases of resistance evolution. Given the same resistance mechanism, populations approaching homozygosity in resistance allele(s) would have higher resistance levels than those with low frequency of resistance allele(s). The ED50 values for GR A. palmeri in Arkansas were similar to those reported previously for other GR A. palmeri (Gaines et al. Reference Gaines, Zhang, Wang, Bukun, Chisholm, Shaner, Nissen, Patzoldt, Tranel, Culpepper, Grey, Webster, Vencill, Sammons, Jiang, Preston, Leach and Westra2010; Ribeiro et al. Reference Ribeiro, Pan, Duke, Nandula, Baldwin, Shaw and Dayan2014) and A. tuberculatus (Nandula et al. Reference Nandula, Ray, Ribeiro, Pan and Reddy2013).

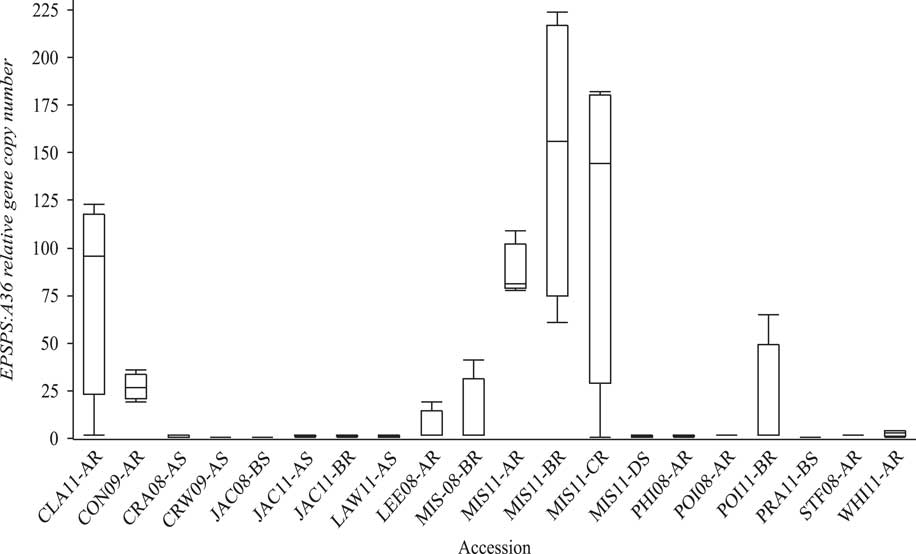

EPSPS Gene Copy Number Relative to A36

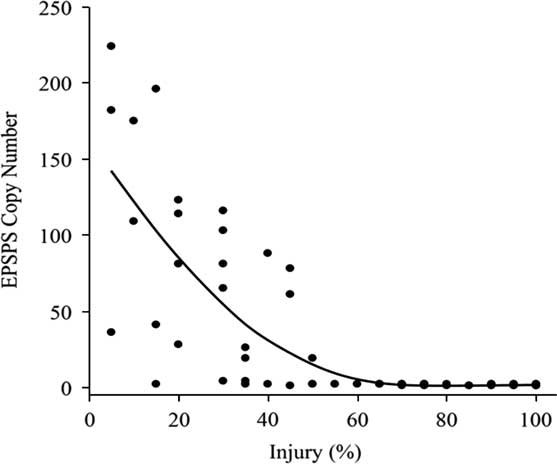

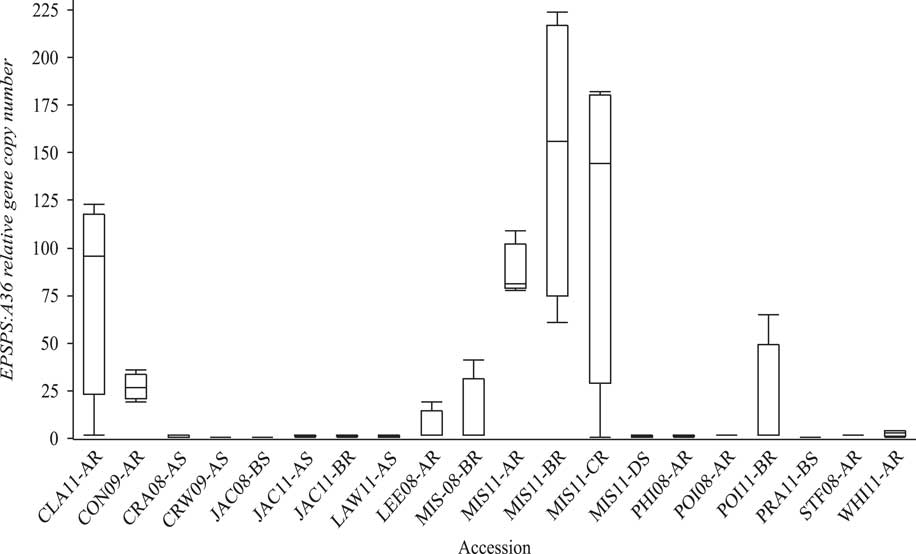

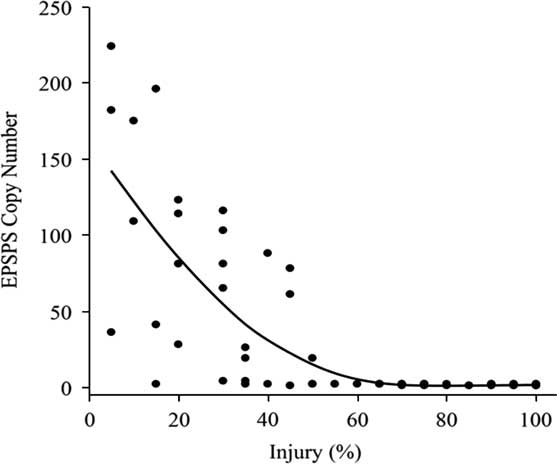

The susceptible A. palmeri accessions from Arkansas had a single copy of EPSPS (Figure 2). Survivor plants from eight GR accessions CLA11-A, CON09-A, LEE08-A, MIS08-B, MIS11-A, MIS11-B, MIS11-C, and POI11-B (Clusters 2 and 3) had 19 to 224 maximum copies of EPSPS, with population means of 6 to 149 copies. Thus, EPSPS copies also differed within resistant populations. For instance, the relative copy number in MIS11-A ranged from 78 to 109; in MIS11-B, 61 to 224; and in MIS11-C from a single copy to 182 copies with SDs of 15, 75, and 84, respectively (Figure 3). In a resistant plant, gene amplification results in abundant EPSPS enzymes, which compensates for the units inactivated by glyphosate. Therefore, resistant plants are still able to produce aromatic amino acids and survive glyphosate application. Resistant plants with a single EPSPS copy most likely harbor a different resistance mechanism. EPSPS gene amplification is a common resistance mechanism among GR Amaranthus spp. In the first case of EPSPS amplification observed in A. palmeri from Georgia, GR plants had up to 160 EPSPS copies that resulted in 40-fold overexpression of the gene (Gaines et al. Reference Gaines, Zhang, Wang, Bukun, Chisholm, Shaner, Nissen, Patzoldt, Tranel, Culpepper, Grey, Webster, Vencill, Sammons, Jiang, Preston, Leach and Westra2010). Glyphosate-resistant A. palmeri from North Carolina had 22 to 63 EPSPS copies (Chandi et al. Reference Chandi, Milla-Lewis, Giacomini, Westra, Preston, Jordan, York, Burton and Whitaker2012); in Kansas, 50 to 140 copies (Varanasi et al. Reference Varanasi, Godar, Currie, Dille, Thompson, Stahlman and Jugulam2015); in Mississippi, 33 to 59 average copies (Ribeiro et al. Reference Ribeiro, Pan, Duke, Nandula, Baldwin, Shaw and Dayan2014); in New Mexico, up to 8 copies (Mohseni-Moghadam et al. Reference Mohseni-Moghadam, Schroeder and Ashigh2013); and recently, in Nebraska, 32 to 105 copies (Chahal et al. Reference Chahal, Varanasi, Jugulam and Jhala2017). It has been reported that fewer than 30 EPSPS copies result in resistance to field-recommended rates of glyphosate (Gaines et al. Reference Gaines, Shaner, Ward, Leach, Preston and Westra2011), but the minimum number of copies needed to confer resistance to glyphosate is not known. In current research, the level of injury from glyphosate application was negatively strongly correlated (r=−0.78) with genomic EPSPS copy number (Figure 3). Resistance to glyphosate increased with EPSPS gene copy number. Seven susceptible accessions (including SS) that had >60% injury had only one copy, whereas those with <60% injury (resistant) had higher EPSPS gene copy numbers. The highly resistant accessions MIS11-A, MIS11-B, and MIS11-C, with average 30%, 31%, and 26% injury at the 1X rate had 87, 149, and 118 EPSPS copies, respectively. Injury declined by 4% with each additional copy of EPSPS. The EPSPS copy number was also strongly correlated with the ED50 values of the GR accessions (r=0.72). Sixty-two percent of the GR accessions had 10 or more EPSPS gene copies and survived the field rate of glyphosate (840 g ha−1). The EPSPS gene duplication mechanism has been studied extensively. Gaines and colleagues (2010) reported that 30 to 50 EPSPS copies enabled plants to survive treatment with 0.5 to 1 kg ha−1 glyphosate. Glyphosate-resistant spiny amaranth (Amaranthus spinosus L.) had up to 37 more EPSPS copies, resulting in a 5-fold resistance to glyphosate (Nandula et al. Reference Nandula, Wright, Bond, Ray, Eubank and Molin2014), and A. tuberculatus had up to eight extra copies of EPSPS compared with the SS and 5- to 7-fold glyphosate resistance (Lorentz et al. Reference Lorentz, Gaines, Nissen, Westra, Strek, Dehne, Ruiz-Santaella and Beffa2014). Bromus diandrus from Australia had 5-fold resistance with 10 to 30 EPSPS copies (Malone et al. Reference Malone, Morran, Shirley, Boutsalis and Preston2016). In L. perenne, up to 30 EPSPS copies conferred 13-fold resistance to glyphosate (Salas et al. Reference Salas, Dayan, Pan, Watson, Dickson, Scott and Burgos2012). Thus, EPSPS gene amplification is becoming the predominant resistance mechanism among more recently evolved GR weed populations.

Figure 2 Variability in relative EPSPS:A36 gene copy number among susceptible (S) and resistant (R) Amaranthus palmeri accessions. Box plot shows median values (horizontal line inside the box), first and third quartile values (box outlines), and minimum and maximum values (whiskers).

Figure 3 EPSPS gene copy number versus level of injury in glyphosate-resistant and glyphosate-susceptible Amaranthus palmeri. Data were subjected to the quadratic regression equation a+b* injury+c* injury2, where a=intercept, b=slope of the line, c=quadratic. The correlation between percent injury (x-axis) and EPSPS:A36 relative gene copy number (y-axis) was (r=−0.78).

Taken together, studies indicate that weedy species have evolved various mechanisms to survive glyphosate application. It appears that GR plants (across species) harboring the EPSPS gene amplification mechanism have at least eight EPSPS copies, resulting in a wide range of resistance levels. In A. palmeri and L. perenne, at least 10 relative copies of the EPSPS gene confer resistance to glyphosate. The correlation between EPSPS gene copy number and resistance level had not been assessed in GR species except for L. perenne and A. palmeri; hence, a broad conclusion is not supported. At least two factors can modify the resulting whole-plant resistance level from increased EPSPS gene copies: (1) the realized level of protein expression and (2) the presence of other resistance mechanisms in the same plant. Different TSR mechanisms can occur in one species, as observed in E. indica. One GR E. indica accession had 28 more EPSPS gene copies than the SS, while other GR accessions had mutations at the target site (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Huang, Zhang, Wei, Huang, Chen and Wang2015). If plants with different resistance mechanisms are selected and survive to reproduce in one population, then multiple, separate mechanisms could accumulate in a plant via gene flow.

Partial EPSPS Gene Sequencing

Resistance-conferring point mutations at Pro-106 and Thr-102 have been documented in GR weed species. Substitutions of Pro-106-Ala in L. rigidum in Australia (Yu et al. Reference Yu, Cairns and Powles2007), Pro-106-Leu in L. rigidum from South Africa (Kaundun et al. Reference Kaundun, Dale, Zelaya, Dinelli, Marotti, McIndoe and Cairns2011), and Pro-106-Ser (Baerson et al. Reference Baerson, Rodriguez, Tran, Feng, Biest and Dill2002) or Pro-106-Thr (Ng et al. Reference Ng, Wickneswary, Salmijah, Teng and Ismail2004) in E. indica from Malaysia all resulted in low-level resistance to glyphosate. High resistance to glyphosate has been observed in the presence of a double mutation Thr-102-Ile and Pro-106-Ser (TIPS) in the corn (Zea mays L.) EPSPS gene (Eichholtz et al. Reference Eichholtz, Scott and Murthy2001). The same TIPS double mutation was discovered in a rare population of E. indica, resulting in high-level resistance to glyphosate (Yu et al. Reference Yu, Jalaludin, Han, Chen, Sammons and Powles2015). In our study, 38% of GR accessions did not have gene amplification (Figure 3). The GR plants did not contain any changes in amino acid sequence in the conserved region of EPSPS (unpublished data). Some silent mutations were observed in plants POI08-A1, STF08-A1, and STF08-A4 at Pro-106 (CCA to CCG) and in five plants from PHI08-A1, PHI08-A3, STF08-A1, STF08-A3, and WHI11-A1 at Leucine-107 (TTG to TTA). Therefore, none of the known target-site mutations were involved in resistance to glyphosate in these accessions.

The analysis of multiple accessions from different counties of Arkansas indicated variability within and among field populations for resistance level and resistance mechanisms. Additionally, there is a correlation between EPSPS gene copy number and resistance level to glyphosate. Resistance to glyphosate in A. palmeri is rampant in Arkansas. Nonetheless, 30% of the populations can still be controlled with glyphosate and should be managed proactively to delay and isolate resistance evolution. Large-scale surveys are informative in making appropriate management decisions. In conclusion, resistance to glyphosate among A. palmeri populations was conferred by amplification of the EPSPS gene among 62% of the GR populations studied. The GR plants showing neither EPSPS gene amplification nor resistance-conferring mutations indicate the putative involvement of NTSR mechanisms, which requires further investigation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Reiofeli A. Salas, Seth Abugho, and Leopoldo Estorninos for their help in planting and spraying. We also thank Kristin Elizabeth Beard from the Lawton-Rauh lab for sharing her modified protocol for EPSPS copy-number assay. This project was funded by Cotton Incorporated and Syngenta Crop Protection Inc. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.