Since its origins in the United States, the drum kit has been adopted around the world by many cultures that have employed it in different ways. Based on the rich traditions of their own countries, drummers have developed particular voices by applying phrasings and sonorities that came from diverse palettes of established musical practices. One of such case is Brazil, where the vast array of national rhythms ranges from samba and baião to maracatu and many others. Brazilians emulate percussion instruments such as pandeiro, tamborim, surdo and zabumba on the drum kit in order to simulate full percussion ensembles, creating sonic environments that are distinctly connected to their musical heritage.

Very often, drum kit scholarship focuses on jazz and rock music, ignoring genres outside of those realms. Drum kit culture was originally formed in English speaking nations and that seems to direct scholars’ main focus of research. As a consequence, one frequently finds generalizations about musics from other genres, without taking into account all the subtleties that differentiate them and labelling them in broad terms such as ‘Latin’ or ‘World Music’. Beyond the anglosphere, a growing body of academic work has developed over the early twenty-first century. Studies considering Brazilian drumming present clear examples of a valuable body of non-English scholarship. Research has revealed the intricacies of drummers such as Edison Machado (1934–1990), Airto Moreira (1941), Dom Um Romão (1925–2005), Márcio Bahia (1958), Wilson das Neves (1936–2017), Hélcio Milito (1931–2014) and Luciano Perrone (1908–2001), among others.1 In spite of the recentness of this scientific effort, this area has been competently mapped out and now can be scrutinized by scholars around the world.

Organized in two sections, this chapter presents research in the Portuguese language: Historical Overview and Technical Characteristics of Brazilian Drum Kit Playing. Through the lenses of scholars that explored the subject, there are indications of drummers with significant contributions and a short discussion on some of the aspects involved in what became known as ‘the Brazilian feel’. In no way do I intend for this chapter to be fully comprehensive, given the extent of the matter and the enormous collection of names and details involved. Ultimately, my aim is to display some of the academic achievements in the area, serving as a prelude to more in-depth studies on Brazilian music.

Historical Overview

Pioneer Players

The arrival of the drum kit in Brazil took place during the 1920s and, unfortunately, documentations about drumming pioneers in the country are scant. Nevertheless, there are names from that time frequently mentioned as relevant. Among those pioneering figures are Valfrido Silva, Joaquim Tomás, João Batista das Chagas Pereira (‘Sut’), and Luciano Perrone.2 The latter, although certainly not the first one, is known as a ‘father figure’ for Brazilian drummers.3 Perrone brought the drum kit into prominence with his groundbreaking work, which included the first recorded drum kit solo in Brazil.4

Luciano Perrone started playing in orchestras that accompanied silent movies and soon was applying elements of rhythms such as samba, baião and maxixe to the drum kit. He was the drummer for the first recording of ‘Aquarela do Brazil’ in 1939, composed by Ary Barroso and arranged by Radamés Gnattali, with whom he performed for more than fifty years. Together, Perrone and arranger Gnattali faced the challenge of adapting ensembles comprised of eight or more percussionists into the playing of a single musician, filling all the spaces left.5 When they began working at the Rádio Nacional in Rio de Janeiro, the drum kit was the only form of percussion available to handle all the arrangements. Those circumstances demanded exploration of the instrument’s sonic possibilities.6 Establishing a connection between the informal universe of samba playing, classical maestros, and arrangers, Perrone was pivotal in defining the development of his instrument.7

Luciano Perrone and his fellow peers made efforts to reproduce the sound of samba percussion instruments on the drum kit. One example is his playing on the snare drum with snares off, holding a stick with one hand while the other hand would play directly on the drum.8 The resulting muffling was very characteristic of atabaque or tamborim patterns.9 Perrone also was known for his samba cruzado (crossed samba), a style in which the right hand plays on the snare and the left crosses over to play the surdo figures on the floor tom, with a muffled strike on beat one and an open sound on beat two.10

During the 1930s and 1940s jazz bands proliferated throughout Brazil, performing regularly in nightclubs within major cities and thus jazz music was mixed with a diverse pool of rhythms such as samba, marcha-rancho, maxixe and the Argentinian tango.11 Along with the orchestras that emerged when television arrived in the early fifties, those bands set the scene in which Brazilian rhythms took form on the drum kit. The great success of Luiz Gonzaga, composer and accordion player from the northeast of Brazil, brought the rhythms baião and xote into the common repertoire.

The aforementioned samba cruzado is an example of samba batucado, which means it was played mainly on drums with minimal cymbal work. Cymbals were used for punctuating rhythmic figures and signalling section changes but not for ‘riding the rhythm’. Educator and drummer Oscar Bolão, who lived closely to Luciano Perrone for many years and was his student and disciple, noted that for Perrone ‘Brazilian music was about drums’ (rather than cymbals).12 In Perrone’s approach, even the hi-hat played with the foot was sporadic.13 The samba batucado was firstly played with both hands on the snare drum only and later there was a development, in which the left hand (for right-handed drummers) crossed over to play the toms. The snare drum invariably was the central component of the kit whereas the toms completed rhythmic ideas. That was the norm from the 1930s up to the 1950s, when US influences and technological progress led to new scenarios in the Brazilian musical landscape. Economic development and the strengthening of infrastructure became primary objectives in Brazil and everything related to the cutting edge was greatly cherished and valued.14

A new way to play samba became identified with innovation and modernity samba no prato (samba on the cymbal).15 The ride cymbal took on a central role, with sixteenth note riding patterns as well as a variety of broken syncopated patterns. The bass drum then was played with an ostinato (dotted eight note followed by a sixteenth note, hi-hat on the upbeats), substituting the simpler patterns previously used (most times only a quarter note on the second beat, with a rest on the first beat). That new pattern was known as bumbo a dois (two on the bass drum). Two drummers often get the credit for being the first to play in this new style of samba no prato, during the mid-1950s: Hildofredo Alves Correa and Edison Machado.16 What is certain is that Edison Machado was the one to popularize the novelty and eventually reap respect and recognition. Those new trends were not only stylistic changes, they represented the contrast of the new (samba no prato) against the old (samba batucado). That dichotomy was entangled in a larger discussion, one that included nationalist discourse, safeguarding the ‘authentic’ Brazilian music, and groups that believed Brazil should be open to the influences coming from the United States. The former considered samba batucado as the only genuine approach for the drum kit, the latter was listening to jazz and struggling for experimentation and freedom.

Bossa Nova and Samba Jazz

Within the context presented above, at the end of the 1950s bossa nova emerged as a prominent Brazilian genre. Displaying highly sophisticated melodic and harmonic lines, this music had a strong impact on Brazilian culture. The 1959 recording of ‘Chega de Saudade’ by João Gilberto was particularly influential, leading ears and eyes around the world to the music of Brazil. This was especially true after 1963, when Gilberto recorded the seminal album Getz / Gilberto with saxophone player Stan Getz. Jazz and Brazilian music were effectively blended. In 1962, Brazilian musicians went to perform a concert at Carnegie Hall in New York and stayed in the United States after that, beginning an era of collaborative work between musicians of both countries. At that time rock and roll had landed in Brazil, engendering jovem guarda and subsequently taking part in tropicalismo. Jovem guarda was heavily influenced by The Beatles’ music, irreverent behaviour and clothing style. Tropicalismo was a mix of a myriad of elements, including Brazilian rhythms (especially from northeast Brazil), American and British rock, and symphonic string arrangements.

Drummers were striving to keep up with all this newness. For instance, before bossa nova they usually played brushes just like drumsticks, striking drumheads in their batucadas. Within the delicate ambiance of bossa nova there was a demand for more intricate brush activity, including more of the swishing motions that were traditional for jazz drummers. Often bossa nova drummers played with a stick in one hand and a brush in the other.17 That approach required playing softer and with a smoother touch. Milton Banana (1935–1998) was the drummer for João Gilberto in both Chega de Saudade and Getz/Gilberto albums. To cope with Gilberto’s requests for gentle sounds, Banana had to delve into more advanced brushes technique.18 Helcio Milito also became a master with brushes, developing a particular style in which his left hand played sixteenth notes sweeping the drumhead (with a light accent on the third note of each beat) and his right hand played those same sixteenth notes, but tapping and accenting phrases (another possibility for the right hand would be to play only the accents, especially at fast tempos).19

The 1960s were a prolific era for instrumental trios (piano, bass and drums). Examples include Tamba Trio, with Helcio Milito on drums; Bossa Três and Rio 65 Trio, both with Edison Machado; Copa Trio, with Dom Um Romão; Sambalanço Trio and Sambrasa Trio, both with Airto Moreira; and Zimbo Trio, with Rubens Barsotti; among many others. There were also larger groups, such as the Copa 5 quintet, led by J.T. Meirelles and with Dom Um Romão and later Edison Machado on drums; and the Bossa Rio sextet, led by Sérgio Mendes and that had Edison Machado as well. These musicians pushed their artistic boundaries and were paramount in the development of Brazilian drumming on the drum kit. Those in Rio de Janeiro would gather at the Beco das Garrafas (Alley of the bottles) for jam sessions,20 where instead of a featherweight style the drums were played hard.21 With intense and substantial doses of jazz improvisation, the resulting music became known as samba jazz.

Samba jazz gave leeway to drummers to shine with their individual musical voices. With the samba no prato approach, they could phrase the left hand freely on the snare drum and toms accordingly to the soloist’s ideas, in a similar concept to jazz drummers comping. Edison Machado was the main purveyor in the diffusion of this new conception, having reached it through sheer fortuity. According to Machado, he started playing this way, playing on the ride cymbal, when his drumhead broke during a show.22 Machado’s bass drum technique was described by drummer Tutty Moreno as ‘velvety’ even at very fast tempos.23 Keeping the bumbo a dois solid, steady and effortless was fundamental to handling the syncopated rhythms that took place on the cross-stick and on the ride cymbal. In slow and medium tempos Machado usually played sixteenth notes with the right hand and a fixed pattern with the left (two eight notes on the first beat and the second sixteenth note of the second beat). In fast tempos, he abandoned the sixteenth notes and played both hands together with tamborim patterns, very syncopated and with irregular metrics.24 Machado’s artistry was best portrayed in his only recording as a band leader, entitled É Samba Novo (1963), with polyrhythmic perspectives, melodic lines on the toms, and intense interaction with improvisers.

Dom Um Romão was another influential drummer that emerged along with samba jazz. Romão often also employed samba no prato and bumbo a dois but with distinctive features on his left hand such as the raspadeira (scraper). That was the act of, before playing a cross-stick, quickly striking the rim of the high tom, resulting in a flam.25 When playing the snare and toms, Romão would emulate typical patterns of Afro-Brazilian percussion instruments such as surdo, pandeiro, tamborim, reco-reco, caixa, cuíca, repinique and chocalho, looking not only for the rhythms but also for the sonic singularities of those instruments.26 For instance, his recurrent use of the telecoteco27 and other syncopated patterns on the cross-stick alluded to tamborim figures whilst his rimshots on the snare drum implied the sound of the repinique.28

Dom Um Romão’s playing was fierce and energetic, but he had a delicate touch when the situation demanded, notable on his recording with Frank Sinatra and Antonio Carlos Jobim. The same could be observed in Edison Machado, who also had to restrain his dynamic gamut when he recorded the first Jobim solo album.29 These musicians ventured into uncharted territory with samba jazz but absolutely knew how to navigate in the calm waters of bossa nova. They were the two jazzier players in Brazil at the time and had prowess and finesse to perform at any musical circumstance.30

Technical Characteristics

The ‘Brazilian Feel’

In 1965 Dom Um Romão moved to the United States and three years later Airto Moreira did the same. Both musicians were, first and foremost, drum kit players but became successful musicians in the United States as percussionists.31 Playing a rich spectrum of timbres with their instruments, Romão and Moreira were responsible for the spreading of the berimbau outside Brazil. Both drummers were sought after due to the varied musical palette represented by their approaches and because they added the ‘Brazilian feel’ to their groups, a special quality that can be identified with the idea of ‘swing’ in jazz. Though a difficult concept to pinpoint, the ‘Brazilian feel’ can be explained in technical terms and understood by careful listening to specialist drummers such as Moreira.

Asked what was the best music he had ever played, Moreira points to Quarteto Novo, a group that mixed rhythms from north eastern Brazil with jazz improvisation and that grew to be a major reference for future generations of Brazilian musicians.32 The only record produced by this group dates from 1967 and in it, Moreira was already using different percussion instruments added to his drum kit, searching for ‘colours’ and ‘textures’ that later became his personal mark. Moreira also started emulating the sounds of the zabumba on the snare drum and of the triangle on the hi-hat, widening his vocabulary with new ideas. Unlike the other great Brazilian drummers of the sixties (Romão, Machado, Milito, Banana, etc.) that kept their playing within the samba terrain, Airto Moreira expanded his boundaries by pursuing new rhythms such as frevo, coco, xaxado and baiao.33 Moreover, Moreira brought different time signatures into rhythms that were usually played in 2/4, including sambas in 7/8 and 3/4.34

During the 1970s, especially in solo recordings Airto Moreira was playing drum kit and percussion, sometimes one after the other, sometimes putting it all together through the use of overdubs. That combination had a strong influence on many players that were focusing mainly on the drum kit, such as Robertinho Silva (1941), Nenê (1947), and Tutty Moreno (1947).35 Improvements in recording technologies made possible for various layers of percussion to be stacked on top of each other, and as a result drum kit parts were simplified, to ‘make room for other instruments’.36 The same simplification was happening to drummers who were working heavily in studios in Brazil, such as Wilson das Neves. Instead of his sambas with bumbo a dois and lots of cross-stick syncopations, he recorded many songs with only hi-hat and bass drum on the second beat.37 Das Neves is another name that embodies the Brazilian feel through the whole of his career, despite the fact that he moulded his playing in consonance to many different musical scenarios.38 Whatever the genre, these musicians always employed a considerable dose of ginga, the Portuguese word that corresponds to swing.

Music notation has its limitations to accurately capture the ginga of Brazilian rhythms. As Wilson das Neves has explained, ‘you can’t write down the swing of a person’.39 Understanding ginga with a physics lexicon, there are rhythmic fluctuations in a flexible net, in which the elasticity makes possible the existence of some basic structures, but not in metronomic perfection.40 Considering the question musically, one way to look at it is to ask: how successful is this drum kit player in the reproduction of various percussion instruments, including basic rhythmic structures and transitional sounds?41 Part of the challenge in answering that question stems from the interpretation of sixteenth notes, the ‘elementary pulse’ for samba42 and for other Brazilian rhythms as well.

The ‘elementary pulse’ is played with irregular spacing between the sixteenth notes as they do not each get twenty-five per cent of the beat. There are continuous variations in the distribution of these notes from measure to measure so any attempt to register ‘a definite notation for samba’ is likely to be ineffective.43 The nuances in dynamics also are hardly captured by music notation. Analyses of snare drum samba patterns have shown four levels in the accents played, with consecutive fluctuations in their disposition.44 Disparately, drum technique books usually display samba as an oversimplified pattern of four sixteenth notes, with accents on the first and on the fourth.

Facing all these subtleties in dynamics and note placement, it becomes evident that simply playing a samba pattern ‘as written’ is not enough to perform it authentically. Research on micro-rhythms has confirmed this discrepancy demonstrating that notation is a ‘virtual reference structure’ while the ‘actual sounding event’ often results from deviations from that presumed form.45 Hence samba comes alive from musicians’ use of expressive micro-timing, in the same manner that swing occurs in jazz.46 Just like jazz ride patterns rarely align perfectly on the beat, whether the ‘beat’ is provided by a metronome click or another instrument, samba drummers are playing with the beat, rather than playing with the beat.47

A dichotomy arises for drum kit players when working on stick technique and Brazilian rhythms. Traditionally, technique is developed through the study of rudiments, but that results in a paradoxical situation: when practicing rudiments there is a goal of perfect balance between hands in regards to sound qualities, dynamics and note placement. When playing Brazilian rhythms on the drum kit, however, hands often have to sound different for an authentic feel and note placement occurs within the above-mentioned flexible net and its fluctuations. As a consequence, when performing Brazilian rhythms one must ‘forget’ some of the equilibrium that was emphatically aimed for during technique practice. For those who have practiced rudiments for a long time and are first playing Brazilian drum kit rhythms, it might be difficult to abandon the rigidity and give in to elasticity in note placement. On the other side, those who were raised amidst Brazilian culture possibly have learned those rhythms aurally and might know their sounds, but then to evolve as a drum kit player there is a need to work on rudiments for the development of muscle memory and stick control.

Modern Brazilian Drumming

Those distinctive sixteenth notes fluctuations prompt a difficult task when playing samba no prato in fast tempos. There are alternatives of using broken patterns with hands in unison or in combinations of phrases, but many Brazilian drummers have risen to the challenge of playing the non-stop flow of sixteenth notes. That approach is inevitably burdensome and special techniques have been developed to cope with that demand in tempos over 130 bpm.48 For instance, renowned drummer Kiko Freitas plays sixteenth notes using what he denominates ação e reação (action and reaction), derived from the Moeller technique.49 This enables him to emulate the sound of the repinique, which is traditionally played with a stick in one hand (playing the first three notes of each beat) while the other hand plays directly into the drum (the fourth note), but using only his right hand to ride his samba rhythms.50

As part of a long lineage of players, Freitas is a symbol of modern Brazilian drumming. Between Freitas and Luciano Perrone, many others have carried on the traditions and taken them to new heights. Newer generations are in constant exposure to modern drumming concepts through communication technologies and the diffusion of hybrid styles, from influential musicians that have flourished since the 1970s. Examples are plentiful. Marcio Bahia came with a progressive rock background, and after jazz studies and classical percussion training, spent more than thirty years of intense work with Hermeto Pascoal, exploring an ample spectrum of Brazilian music. Bahia played rhythms such as choro, maxixe, samba, baião, xote, xaxado, frevo, and maracatu in odd times, orchestrated around the drum kit with great dexterity and four-way coordination.51 Because of the pluralism in experiences prior to joining Hermeto’s group, Bahia was able to adapt to multiple situations, sometimes improvising freely in complex structures and other times reading note per note dense and intricate written arrangements.

Before Marcio Bahia, two other prominent drummers had played with Hermeto Pascoal: Zé Eduardo Nazário and Nenê. Nazário acknowledges Edison Machado and Dom Um Romão as his foundations and understands that his generation took their work a step further.52 Realcino Lima Filho, best known as Nenê, replaced Airto Moreira in Quarteto Novo when Moreira left for the United States. Both Nazário and Nenê had the right skills and musical tools to embark on Hermeto’s artistic journey during the 1970s, just like they both did for multi-instrumentalist Egberto Gismonti in later years. Along with Paulo Braga, Pascoal Meirelles, Duduka da Fonseca and many others, these musicians shaped Brazilian drum kit drumming to modern times, building ideas that younger musicians are now fusing with past approaches, current techniques and twenty-first century drum sounds.

Conclusion

The influence of Brazilian drum kit drumming on global popular music has been immense and cannot be underestimated. It has been especially evident in the popularity of samba and bossa nova, as genres popular in their own right, but even more so in the influence of those genres on contemporary drumming in jazz and popular music throughout the world. Therefore, Brazilian drum kit drumming has been essential in the cultural flows that informed the development of the drum kit. As much as Brazilian musicians look for references within jazz and rock, the rhythms that emerged from Brazil are nowadays deemed to be a core part of the skillset for jazz drummers and players of other genres.

The fine details of what makes Brazilian drum kit drumming unique and special are yet to be explored thoroughly. Definitely the concept of ginga is a distinguishing element, in which musicians play around the rhythmic fluctuations and characteristics of the music. The verb gingar is also related to body movement and is used to describe the motions in capoeira, another cultural manifestation that vividly represents the essence of Brazilian people. In other words, gingar intrinsically means the expression of being Brazilian both musically and in the way dancers move. That idea resonates with ‘the fact that different microrhythmic designs appeal to (and signify differently for) different audiences’.53 Even though any rhythm may be deconstructed and mathematically analysed, that remains an ineffable and ethereal trait of all the drummers mentioned in this chapter.

Besides this intangible quality of ginga, Brazilian drum kit drumming comes from adaptations of percussion instruments, opening singular pathways for musical creativity. Drummers might emulate the sound of a pandeiro on the hi-hat and then make the snare drum have earmarks of a repinique; they might use the floor tom like a zabumba or bring tamborim patterns into life on the ride cymbal bell. They also often weave colours from assorted rhythms of the Brazilian plate, forging new combinations of ideas. Thus the ‘Brazilian feel’ keeps evolving, well grounded in its roots but open for innovation, establishing a fertile field for new music and for scientific investigation.

Introduction

The drum kit, an instrument deeply rooted in popular music traditions, is a defining element of many popular music styles. Since the early twentieth century, generations of drummers have explored new musical and technical possibilities of the instrument and, recent years, the drum kit has emerged in contemporary classical music settings as a solo instrument with prescribed notation. In this chapter, contemporary classical music refers to music being written now, or in the past few decades by composers operating within the framework of Western classical music notational traditions. While there is a growing interest in this repertoire today, composers have drawn inspiration from the drum kit since the early developmental stages of the instrument in the early twentieth century. I will present an overview of composed works starting with Darius Milhuad’s La Créations du Monde from 1923 and ending with Nicole Lizée’s Ringer from 2009. I will show that early approaches to drum kit composition began as an assimilation of existing popular music styles with little progression in performance techniques and expression for the instrument. In recent years, many composers have approached drum kit composition by balancing contemporary classical music techniques with the drum kit’s rich traditions, grooves, and styles to make something progressive and new. Through my own commissioning, performances, and research I have contemplated the elements that led to this confluence in contemporary classical drum kit music.

Personal Background

In 1988, I began taking drum kit lessons in my hometown of Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. Thanks to the exceptional drum instruction of my teacher David Schneider, I embraced a wide range of styles and playing traditions. I went on to play in a variety of bands ranging from punk, progressive rock, and reggae styles. After highschool I decided to pursue a music degree, but I chose to focus on orchestral and concert percussion instead of drum kit. I received a Bachelor of Music degree from McGill University in Montréal and a Master of Music degree from the State University of New York in Stony Brook, both in contemporary classical percussion performance. No longer receiving drum kit instruction, and with little time for playing in bands, I was quickly distinguishing myself as a classical percussionist rather than a drummer.

After my Master’s degree, I returned to Manitoba where I began teaching percussion at Brandon University and playing regularly with the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra. Around this time, I began to consider if the drum kit could have a greater role in my life of contemporary classical performance. I knew of a few composed works for drum kit such as Frank Zappa’s ‘The Black Page’ and Louis Cauberghs’s ‘Halasana’, and I wanted to expand on what I saw as a limited amount of repertoire. In 2006, I sought out and was successfully awarded my first commission of the solo Train Set by composer Eliot Britton.

In 2007, I met composer Nicole Lizée while performing her chamber work This Will Not Be Televised with members of the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra. Pleased with my performance, Lizée invited me to play drum kit for various works on her debut album This Will Not Be Televised, released by Centrediscs in 2008. That same year, with the support of the Canada Council for the Arts, I commissioned Lizée’s first solo for drum kit, Ringer. Encouraged by these new experiences, in 2010 I returned to McGill University in Montréal to complete a Doctor in Music degree where I wrote my dissertation ‘Defining the Role of Drumset Performance in Contemporary Music’. As of today, through collaborations with composers from around the world I have premiered an extensive collection of contemporary classical drum kit solos, chamber works and concertos. My solo drum kit album Katana of Choice – Music for Drumset Soloist was called ‘a modern classic’ by I Care If You Listen and the title track by Nicole Lizée was nominated for a JUNO (Canadian music award) for best classical composition in 2019. When I consider my broad range of musical training and performance experience it seems natural that I am drawn to an artistic practice that crosses between genres. I draw from this personal experience to articulate broader points about the place of the drum kit in the classical world and the unique skill sets required when approaching the drum kit in contemporary classical music.

Drummer or Multiple Percussionist?

In contemporary classical music practice, the term ‘multiple percussion’ is associated with a body of repertoire for the solo percussionist, which incorporates several instruments played by a single performer. As drum kit repertoire appears increasingly alongside works for multiple percussion, there is a tendency to place such performers and repertoire in the same categories. Drummer Max Roach was said to have brought ‘dignity to an instrument long misunderstood and assaulted by the ignorant’ and set a precedent by referring to himself as a multiple percussionist in album liner notes.1 At the time, this reflected his elevation of drum kit performance and the desire to be considered equal to the other instrumentalists.

As solo drum kit repertoire in contemporary classical music has increased, the discussion of its inclusion in college percussion pedagogy has led some authors to still justify its existence and continue the comparison to multiple percussion. The 2012 dissertation by Kevin Nichols called ‘Important Works for Drum Set as a Multiple Percussion Instrument’ provided an introduction and unique performance perspective to composed drum kit solos such as The Sky is Waiting … (1977) by Robert Cucinotta, One for Solo Drummer (1990) by John Cage, Brush (2001) by Stuart Saunders Smith and others. He noted the lack of studies or method books which ‘investigate the literature for drum set as a multi-percussion instrument’ and expressed his ‘desire to encourage solo drum set performance and composition by making this music and these concepts more widely known and understood’.2 Murray Houllif’s ‘Benefits of Written-Out Drum Set Solos’ encouraged solo repertoire for students as ‘an effective means to learning improvisation’.3 In ‘Drum Set’s Struggle for Legitimacy’, Dennis Rogers argued that written recital pieces can demonstrate that the ‘drum set is a legitimate instrument that is quite acceptable in the percussion curriculum’.4

In this chapter, I use the term drum kit without association to multiple percussion. I do so to distinguish the drum kit as an instrument worthy of its own legitimate considerations, apart from earlier efforts to elevate the instrument’s status. The label of multiple percussion places an unwanted shadow over the popular music styles and the associated players, techniques, and instruments that are the foundation of the instrument.

What, then, clearly distinguishes drum kit from other contemporary or multiple percussion performance? The Encyclopedia of Percussion says that the drum kit is ‘a set of drums, usually bass drum, snare drum, tom-toms, hi-hat, and cymbals’.5 James Blades describes drum kit performance as ‘the advancement of counter rhythms and independence’.6 Jazz drummer Kenny Clarke described his use of multiple limbs as ‘coordinated independence’.7 Combining these ideas, I suggest that the definition of drum kit performance is: the use of coordinated independence of multiple limbs on a collection of drums and cymbals, including but not limited to, bass drum with pedal, snare drum and hi-hat, set up for convenient playing by one person.

Early Drum Kit Composition Via Jazz Assimilation

La Création du Monde (1923) by Darius Milhaud

The earliest approach to drum kit composition appeared in Darius Milhaud’s ballet, La Création du Monde, premiered on 19 October 1923. Like many European composers of the time, Milhaud assimilated the sounds, instruments, and performance practices of the exciting new popular music style from the United States called jazz. Milhaud drew inspiration from the words of the artist Jean Cocteau. In his manifesto, Le Coq et l’Arlequin (1918), Cocteau called for a new sound in French music, dismissing the more ‘Russian-inspired impressionism’ of past composers such as Claude Debussy.8 ‘Enough of clouds, waves, aquariums, waterspirits, and nocturnal scents; what we need is a music of the earth, every-day music’.9 Cocteau encouraged composers to draw inspiration from the new sounds of jazz, bringing together the ‘low-art’ of the cafés and dance halls and exoticism of African culture into a new French modernist approach.

Author Bernard Gendron described Milhaud as a ‘modernist flâneur’ who was ‘more akin to the tourist, the slummer, and the fashion plate, than to the ethnomusicologist’, and Milhaud’s ‘adventures in curiosity and assimilation’ resulted in a very limited reflection and understanding of jazz and along with this, the drum kit.10

The limited understanding of jazz music assumed the term to include a variety of styles and techniques including blues, ragtime, the Original Dixieland Jazz Band’s popular take on ragtime known as Dixieland, Tin Pan Alley songs from New York City and, generally, any music played by dance bands at the time. The drum kit was at the centre of this style.

Despite the confusion during these early days, there was at least one common musical meaning when people in France invoked the term jazz: it meant rhythm and the instruments used to make it. Above all, the drums – la batterie – were not only the most prominent instrument but their mere presence, many believed, made any band into a jazz band.11

Milhaud toured through the United States in 1922 where he searched for what he called the ‘authentic’ elements of jazz.12 Immediately upon returning to Paris, Milhaud began to work on the music for the ballet, La Création du Monde for seventeen instrumentalists including drum kit. The drum kit included snare drum, bass drum with foot pedal, woodblock and cowbell. The ‘grosse caisse à pied, avec cymbale’, meaning ‘kick drum with cymbal’ referred to the ‘clanger’, a predecessor of the hi-hat.13 Milhaud indicated in the music when to activate or deactivate the clanger against the mounted cymbal.14 Ragtime rhythms common in the twenties were imbedded in the music with written out triplet figures, and instructions for rim shots and other jazz idioms were found throughout.

To appreciate how Milhaud assimilated the style, I recommend listening to Baby Dodds’s 1946 recording on Folkways Records for reference of period ragtime performance. Having remained committed to the drum kit instrumentation of the twenties (Dodds never took up the hi-hat, for example) the recorded solo Spooky Drums in particular is a window into early drumming and gives an authentic reference to ragtime rhythms and their placement around the drum kit.

Milhaud was not the only composer to assimilate jazz and, as a result, drum kit elements into the contemporary classical setting. Here is a brief list of other works that followed: George Gershwin, Rhapsody in Blue (originally for the Paul Whiteman Jazz Orchestra, 1924); Mátyás Seiber, Jazzolettes (1928); Igor Stravinsky, Preludium for Jazz Band (1936 / 37); William Walton, Façade, Second Suite (1938); Gunther Schuller, Studies on Themes by Paul Klee (1959); and Leonard Bernstein, Symphonic Dances from West Side Story (1960). While these composers included popular elements of early jazz and, along with it, the drum kit into a contemporary classical work of the 1920s, the music often suffered the fate of the limited understanding of the style. Milhaud himself bemused that ‘the critics decreed my music was frivolous and more suitable for a restaurant’.15 With works such as La Création du Monde we were given an early glimpse of a search for legitimacy of jazz in a classical setting and a hope that the new ‘everyday music’ would provide inspiration and new approaches to composition. It is a familiar theme when exploring the history of compositions for the drum kit and one we know still exists in recent discussions about percussion pedagogy. Jazz did not benefit from being placed in the concert hall, just as the drum kit did not need to be called multiple percussion.

Drum Kit Composition as Homage

Bonham (1989) by Christopher Rouse

Written for drum kit and percussion ensemble, Bonham by American composer Christopher Rouse was ‘an ode to rock drumming and drummers, most particularly Led Zeppelin’s legendary drummer, the late John (“Bonzo”) Bonham’.16 The work was for eight players: one drum kit and seven other percussionists. It was premiered in 1989 by the Conservatory Percussion Ensemble, conducted by Frank Epstein, at the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston.

In Bonham, the drum kit opened, and continued throughout much of the piece with an ostinato (repeating pattern) that quoted the iconic John Bonham groove from the song ‘When the Levee Breaks’ from Led Zeppelin IV (1971). The ‘Levee’ groove had been highly sampled by other popular artists such as Bjork, The Beastie Boys, Depeche Mode, Dr Dre, Coldcut, and Eminem. In Bonham, fragments of other Led Zeppelin songs such as ‘Custard Pie’, ‘Royal Orleans’, and ‘Bonzo’s Montreaux’ appeared in aspects of the drum kit music as well as throughout the entire ensemble, but it is the ‘Levee’ groove that defined the piece.

In the case of Bonham, the performer had to become familiar with the elements that made John Bonham’s sound iconic. Rouse recommended in the score that the drummer ‘use the fattest possible sticks to reproduce as closely as possible throughout the entire work the beginning of “When the Levee Breaks”, recorded by Led Zeppelin’.17 This referenced the legendary drummer’s reputation for being a powerful, dynamic player – so powerful, in fact, that he is often credited for being an early influence on the heavy metal drumming that would follow him. Jon Bream in Whole Lotta Led Zeppelin said, ‘no drummer ever created such a monstrous sound, and in Bonham’s force field of rhythm there ranks the basis of the sound now called heavy metal’.18

The drum kit performer should have not only adhered to Rouse’s suggestion of heavy sticks, but must have looked further into the characteristics of John Bonham that resulted in such a powerful sound. For example, Bonham played on large size drums associated mostly with his Ludwig Amber Vistalite set made from acrylic which was being commercially produced as ‘Plexiglas’ in the seventies. Another contribution to Bonham’s unique sound was the experimental recording techniques used by engineer Andy Johns and the band. While some variations on specifics exist, the basic concept was that the drums were placed at the bottom of a staircase, with microphones placed above, one or two floors up. This was ‘distant from the Beatlesque, cloth-covered drumhead sound that was de rigueur at the time’, which produced more clarity and articulation.19 Instead, the drums were given room to resonate while the microphones captured the natural power of John Bonham’s performance style.

The John Bonham sound on ‘When the Levee Breaks’ was a combination of the drummer’s distinct power and feel combined with his choice of instrument and the groundbreaking recording techniques that captured it all. Christopher Rouse’s suggestion for the ‘fattest possible sticks’ could not alone reproduce this complex sound. The drummer approaching Bonham should rather be educated in the important elements described above that formed the Bonham sound and draw from as many influences as possible to even come close.

The popularity and success of Rouse’s work, Bonham, was rooted in the adoration and idolization of a drumming icon that is common among generations of musicians. Placing Bonham grooves within the classical percussion ensemble context was an homage to this drummer and the music of Led Zeppelin. This type of composition remains popular within the classical percussion ensemble community because it allows players to explore drummers and styles that often have been separated from the typical focus in Western classical music. Similar approaches for drum kit and percussion ensemble include John Beck’s Concerto for Drum kit and Percussion Ensemble (1979), written for ‘Tonight Show’ drummer Ed Shaughnessy, and Larry Neeck’s Concerto for Drum kit and Concert Band (2005) featuring a rock groove in the style of Sandy Nelson, a jazz-waltz influenced by Joe Morello and a Gene Krupa, up-tempo swing.20

While recorded history has endless examples of drum solos, the drum kit as concerto soloist was indeed a new role found in the above works. What kept these works tied to their predecessors such as Milhaud is that the music was still copying styles and therefore not exploring new performance practices of the drum kit. The only thing new for drum kit was the performance context itself. We still ran the risk of displaying the traits that Gendron described in Milhaud’s case as ‘his excessively formalistic approach … his underestimation of performance at the expense of composition … his simplistic schemes of classification, and his virtual ignorance of the cultural and social context’.21 In the case of Bonham, the limitation was in the impossibility of recreating the drumming style of John Bonham. By placing such a reproduction of an iconic groove into the formula of contemporary percussion ensemble composition we have missed the true significance and brilliance of the original performance of John Bonham with Led Zeppelin and run the risk of sounding like a gimmick or simplifying the greatness of this performance.

As I have stated before, it is the drum kit’s roots in popular music and its rich traditions, iconic players, grooves, and styles that remain tied to the instrument at all times. It is what the previous composers were counting on as they quoted jazz or rock tradition. It took an artist equally versed in rock and contemporary classical music to create the first drum kit solo that seemed to be progressive rather than repeating the past.

Genre Cross-Over in Drum Kit Composition

The Black Page (1976) by Frank Zappa

The legendary rock bandleader Frank Zappa was able to cross over to contemporary classical traditions by writing chamber works for Ensemble Intercontemporain and conductor Pierre Boulez, among others and was said to ‘somehow manage to work with these many, many influences … for many composers this would be a really big danger, to get lost in all those things you could do … but he’s really original at using all these influences’.22 Zappa did not approach writing with regards to labels and class and he ‘refused to rank his own works or engage in debates regarding the difference between “popular” and “serious” music. It was all one to him’.23

Written for drummer Terry Bozzio, The Black Page was an ambitious solo expressing the melodic potential of the drum kit featuring an excessive use of nested polyrhythms and complex patterns demanding unusual crossing of limbs and rapid movement around the drum kit. The typical function of the bass drum foot changed. No longer the timekeeper and foundation, the bass drum was equally involved with the hands in the thematic and melodic material. While not indicated in the score, Bozzio added a constant quarter note pulse with the hi-hat foot in the original recording, a feature adopted by all future performances, and one that has remained standard practice today.24 This simple addition created a stable, familiar framework for the rhythmic complexity. Even with these complexities the solo still had an accessibility through an overall sense of groove that never strayed too far from the familiar. The performer and listener can hear a connection to the iconic drum solos of the past such as Gene Krupa’s solo in ‘Sing Sing Sing’, Max Roach’s ‘The Drum Also Waltzes’ or John Bonham’s many live solos with Led Zeppelin.

Because of the notational complexity and technical challenges mixed with rock sensibilities, The Black Page was a true crossover work and demonstrated a confluence between musical influences and new potential for drum kit composition. Just as important, the solo encouraged a new level of performer equally comfortable in contemporary classical music notation and rock-based drumming. Terry Bozzio described his progression since working with Frank Zappa and The Black Page:

Apply theory, harmony, and melody orchestration … to the modern drum kit, because it has evolved to the point where we can do those things. I see no difference between an organist who plays lines with his feet and four different voices with his two hands and the contrapuntal possibilities that are extant on the modern drum set.25

Complexity in Drum Kit Composition

Ti.re-Ti.ke-Dha (1979) by James Dillon

James Dillon was born in Glasgow, Scotland in 1950, and spent considerable time living in London. As a teenager in the sixties, he was drawn to rock and played in a rhythm and blues band called Influx.26 Dillon eventually pursued post-modern composition, but he did so on his own terms, receiving formal education at a university level for only two years before leaving disillusioned. Even so, by the mid-seventies Dillon was considered a part of the New Complexity school of composition and his music was described as ‘close to if not beyond the limits of performability, justified by reference to the fearsome intellectual discourse which is said to lie behind those torrents of notes’.27 While this style of composition often held a reputation of being elitist or overtly formalist, Dillon said that composing in the seventies was a time ‘to claw my way back to where music still has meaning and not present some kind of second-hand experience’.28

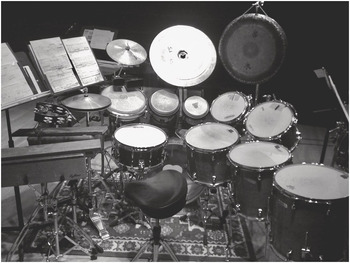

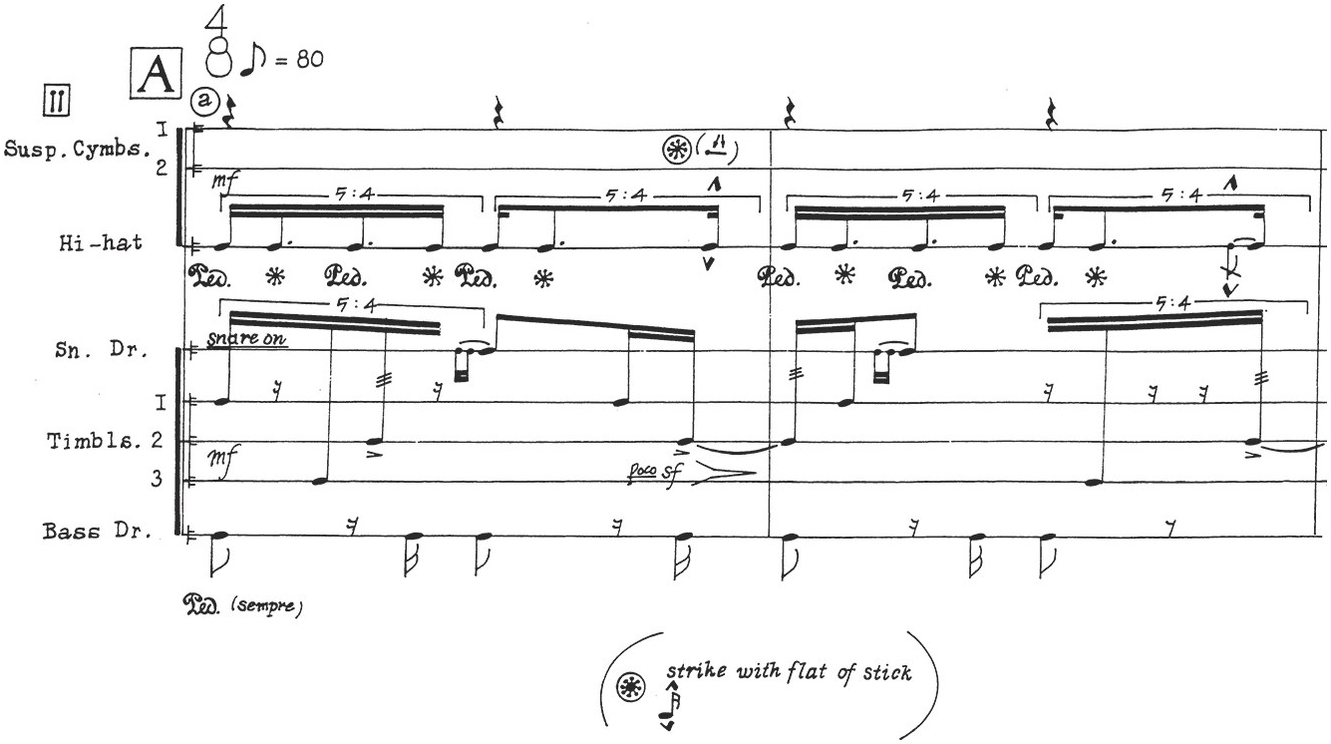

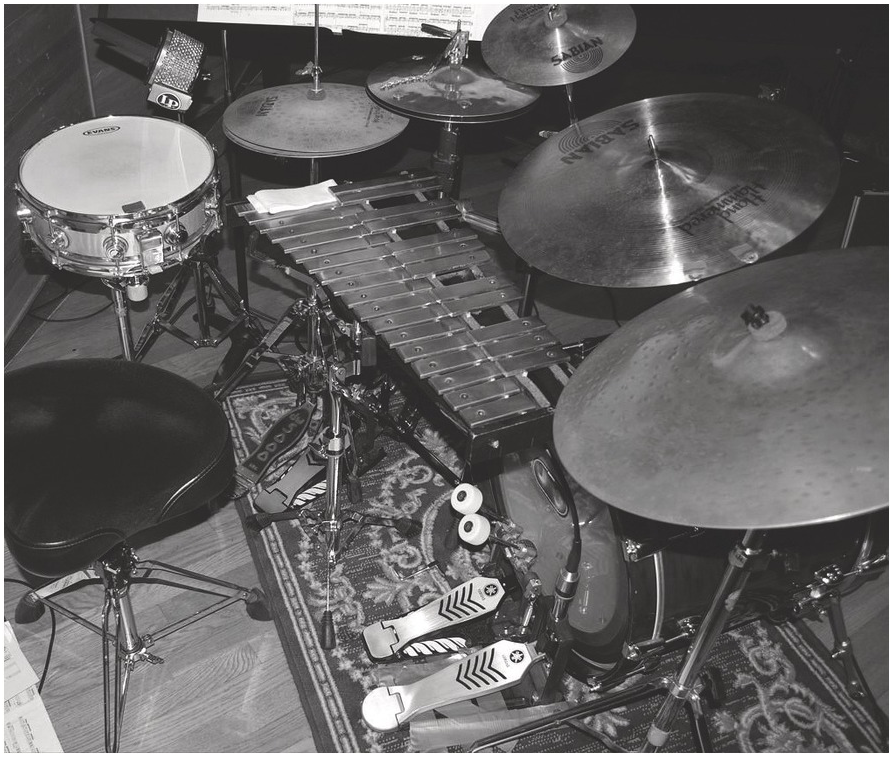

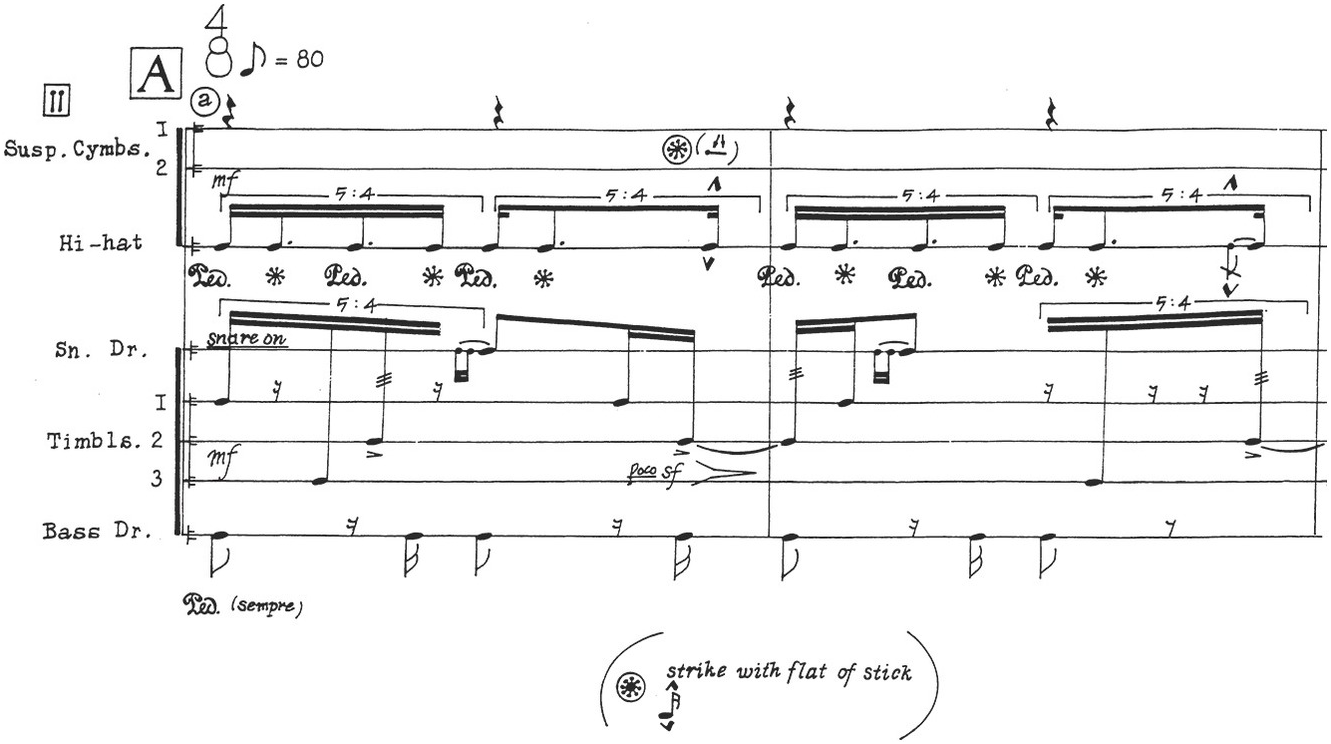

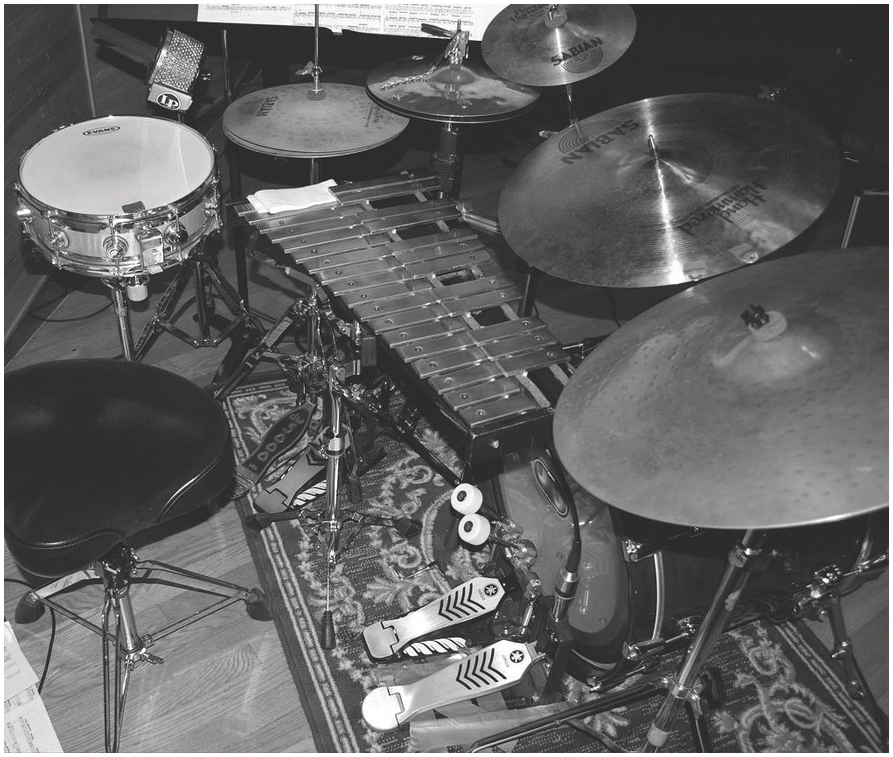

In 1979, Dillon wrote Ti.re-Ti.ke-Dha in celebration of the ‘International Year of the Child’.29 It was premiered by percussionist Simon Limbrick in South Bank, London, 1982.30 The complete list of instruments in Ti.re-Ti.ke-Dha extended beyond the common drum kit to form a massive setup with additional suspended cymbals (one screwed tightly and struck only at the dome), cowbells, hi-hat (with a collection of sleigh-bells attached to top), log drums, snare drum, three timbales, five tom-toms, bass drum with pedal, tam-tam and a bellstick (Figure 6.1). Balancing efficiency and playability with the unusual instrumentation and complex polyrhythmic material resulted in one of the most challenging works in contemporary drum kit repertoire. How each individual interpreted and solved these challenges is part of what made a performance unique. To illustrate, the following section presents two examples of setup challenges and recommended solutions.

The timbales had a far greater involvement in the music than the traditional tom-toms (which only enter at measure 82). Dillon’s recommended layout in the score recognized that they needed to be easily reached, placing them directly in front of the player with the tom-toms to the right. The timbales’ size and inability to be mounted on traditional drum kit hardware posed logistical issues. Also, the timbales had similar timbres to the tom-toms causing some difficulty in making a distinction between the two voices. As shown in Figure 6.1, replacing the timbales with a set of bongos and a travel conga offered a bright, short attack, distinct from the thunderous, resonant tom-toms. Not only sonically effective, they were compact and fit efficiently onto the drum kit.

Dillon also specified two log drums, each producing a single pitch. Generally placed on a flat surface, such as a trap table, the log drums did not attach to any type of hardware. Balance was also a problem since the log drum characteristically featured a ‘warm sonority with limited carrying power’.31 Since Dillon specified the use of snare drumsticks throughout the piece the sound produced from attacking the log drum was lacking in tone and volume. Shown in Figure 6.1, the solution was to attach a piece of ‘purpleheart’ wood onto, and extending beyond, each log drum to allow for a resonant attack area and mount each on a snare drum stand. A thoughtfully chosen setup improved efficiency of motion around the drum kit and clarified some of the dense layers of complexity which Dillon placed into his work.

Dillon employed three common hi-hat practices: loud foot attacks that splashed the cymbals together, dryer foot closing ‘chick’ sounds and playing the hi-hat with sticks. Traditionally used as a time keeping device or for accentuating the pulse, Dillon extended these techniques to be part of the upper layers of thematic material and linear movement (Figure 6.2). The constant execution of these complex foot techniques combined with polyrhythms was an exercise in multiple limb independence, polyrhythmic proficiency and physical balance. A drummer relies on a basic balance when performing and as Grammy-award winning drummer Paul Wertico stated, ‘it’s usually easier to feel balanced when playing simpler exercises. Grooves that require complex counterlines and polyrhythms can sometimes make you feel as if you’re going to fall over’.32

Figure 6.2 Foot techniques: closed HH with foot (𝆯); open HH with foot (𝆮); HH struck with stick (𝆜); repeating bass drum pulse, mm. 1 and 2. James Dillon: Ti.re-Ti.ke-Dha. Edition Peters No.7242 © 1982 by Peters Edition Limited, London.

While large drum kits, foot variations and polyrhythmic playing were all common tools of the modern drummer, James Dillon put these elements to the extreme in Ti.re-Ti.ke-Dha. Challenges with the setup, notational complexity and even basic balance demanded a unique combination of performance skill, much like The Black Page did a few years prior. Also similar is Dillon’s ability to combine New-Complexity style notation (more common with contemporary percussion performance practice than drum kit) with advanced drum kit techniques and fundamentals.

Recontextualization in Drum Kit Composition

Ringer (2009) by Nicole Lizée

Canadian composer Nicole Lizée has been commissioned by a wide range of artists such as Kronos Quartet, So Percussion, and BBC Proms. Her music has often involved unorthodox instruments such as the Atari 2600 video game console, omnichords, stylophone, and karaoke tapes. Lizée’s music has shown her pervasive interest in the drum kit and its connection to time, groove, popular music styles, and iconic performers. In her works for drum kit, she has expanded upon traditional performance practices through what she called recontextualization:

Referring to the past (or other contexts) but twisting, manipulating to create something new, vital, and meaningful to me (and to the ‘now’), without losing trace of its origins, place in history, functions, etc. but reinterpreting, filtering and distorting all of these – and placing it in a new context.33

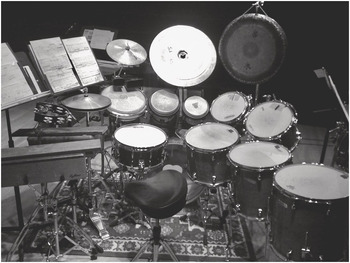

I commissioned and premiered the drum kit solo Ringer by Nicole Lizée in 2009. It was recorded for my album Katana of Choice – Music for Drumset Soloist in 2017 and has been performed by other contemporary drum kit players around the world. Lizée referred to iconic drum kit grooves (such as John Bonham’s in ‘When the Levee Breaks’) as ‘classic drumset paradigms’.34 The solo Ringer for drum kit was a recontextualization of such paradigms in which ‘the end result is intended to be at once familiar and alien’.35 This involved the emulations of drum machines and samplers behaving erratically, fragments of classic grooves characteristic of electronica and dance music warped and iconic drummer Steve Gadd’s paradiddle grooves reimagined as rhythmic and melodic themes.

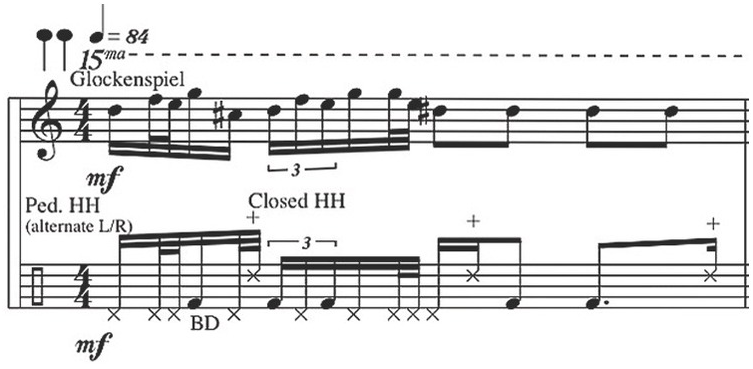

The drum kit in Ringer included kick drum with double pedals, hi-hat and remote hi-hat with pedal (placed to the right of the main kick drum pedal), snare drum, cabasa, cymbals (ride, splash and sizzle) and glockenspiel (Figure 6.3). The arrangement came from personal discussions with Lizée while trying samples of the material during the composers writing of the work and during preparation of the premiere.

Figure 6.3 Drum kit setup for Ringer.

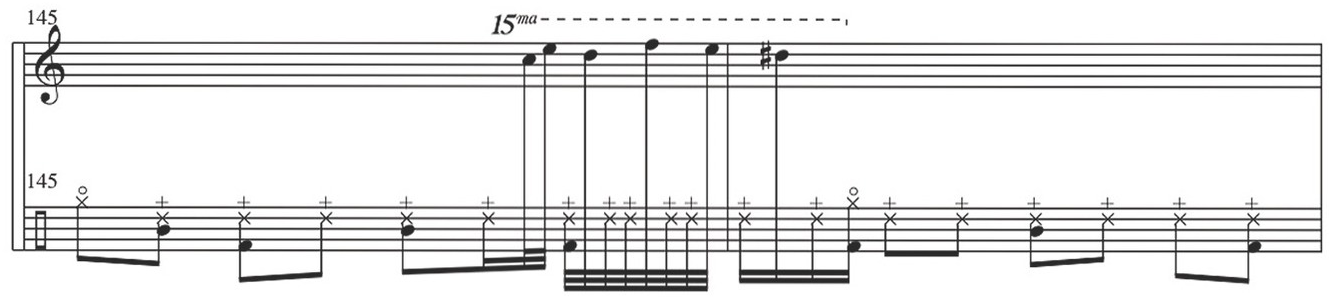

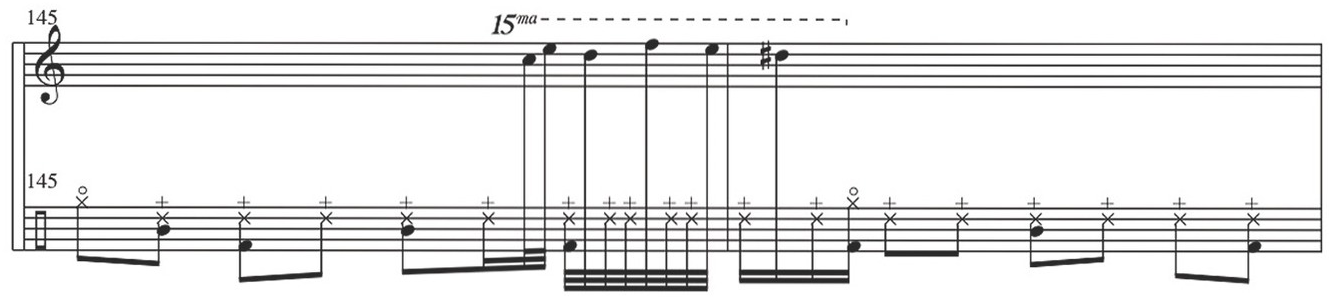

The glockenspiel was placed where the snare drum typically is on a drum kit. By doing so ‘the glockenspiel overtakes or replaces … the snare. In place of what would usually be pitchless accents and articulations, melodic fragments are formed’.36 This was most obvious in the section constructed around drummer Steve Gadd’s paradiddle grooves. Since the seventies, Steve Gadd has been considered one of the greatest drummers of all time, and he has changed how players approach the drum kit and even how the instrument was made. Endorsed by Yamaha since 1976, Gadd’s Yamaha Recording Custom drum kit defined the drum sound of the eighties.37 Gadd also established a signature groove commonly referred to as the ‘Gadd Paradiddle’ based around the sticking of the paradiddle rudiment (R-L-R-R, L-R-L-L) and its multiple variations. In Ringer, the Gadd Paradiddle was morphed and extended around the drum kit, most notably the glockenspiel. Ringer required advanced double bass pedal technique and double hi-hat pedal technique in rhythmic unison with hands (Example 6.2) or completely independent (Example 6.3). Example 6.1 shows ‘melodic fragments’ that were formed on the glockenspiel in replace of snare drum.

Example 6.2 Unison feet and hands in Ringer, m. 1.

Example 6.3 Independent feet and hands in Ringer, m. 202.

Just as James Dillon merged contemporary percussion complexity with drum kit techniques, in Ringer Nicole Lizée showed a confluence between various influences, or a ‘fusing of roles’ where ‘groove and melody synthesize and become one’.38 The inclusion of advanced melodic and rhythmic patterns on the glockenspiel emphasized the performance traditions of a classical percussionist. Typically, such player would have the most experience navigating this instrument since it has appeared most commonly in symphony orchestra repertoire and contemporary classical ensemble settings. Fused into the framework of the drum kit, the performer must be equally experienced in advanced foot techniques and other common drum kit techniques. The presence of rock icon paradigms such as Steve Gadd’s paradiddle required a deep appreciation and understanding of where the material came from and how it was originally played. Then when recontextualized into the new setting for which Ringer presents, the performance still has feeling and groove.

Conclusion

By studying this broad range of works together, I see consistent elements that are required when approaching the drum kit in contemporary classical composition. These are original thought, meaningfulness, and the knowledge of history. Of course, placing the drum kit in the context of the concert hall or within a string orchestra is an exciting premise, but without meaningfully connecting purpose with concepts that move drum kit performance to new places musically, technically, and artistically, the result, as discovered by Milhaud, will be ‘frivolous’.

Today, the drum kit has become a more common addition to ensembles such as Bang On A Can, So Percussion, Alarm Will Sound, my own quartet Architek Percussion, and many others who are performing and commissioning works which blur the boundaries between popular and contemporary classical music. Composers of the past few decades have had a greater opportunity through publications, recordings, online tutorials, and performance footage to learn about the rich history of the drum kit. Since I premiered Ringer in 2009, I have collaborated with a multitude of composers interested in writing for the drum kit. These collaborations have resulted in drum kit performances and recordings by such composers as Lukas Ligeti, John Psathas, Vincent Ho, Rand Steiger, Nicole Lizée, Eliot Britton, John Luther Adams, and many others. Performing this music links an individual to iconic players, grooves, and musical styles that should remain at the core of interpretation, appreciation and, ultimately, performance. It celebrates the evolution of the drum kit, the expressive potential that is possible today, and suggests that new ideas are still to come. I currently teach percussion at McGill University and I am seeing a new generation of players versatile in drum kit and classical percussion performance. I am regularly being introduced to players from around the world promoting the growing interest in this repertoire.

Introduction

Music-theoretical writing about the drum kit often stresses the instrument’s role in shaping listener experiences of musical time. Much of this work concerns the backbeat, whether establishing its prevalence in specific rock and pop genres,1 detailing a range of expressive microtiming feels,2 or contrasting the pattern with other characteristic rhythms.3 Study of the drum kit offers an effective point of contact between the sort of syntactic concerns central to much music-analytical writing and the experiential world occupied by performers and listeners.4 Inquiry into the explanatory potency of the drum kit – what it tells the listener, how it communicates, and how to best interpret its intimations – is still rapidly evolving.

One question that remains to be explored in detail concerns the role of the drums within metrically irregular grooves, which are incompatible with the paradigmatic backbeat pattern often heard in Euro-American popular music. I argue that listener understanding of such grooves is acutely reliant on the guidance of the drums. To investigate this claim, I have analysed the drumbeats of grooves with large irregular cycles, ranging from ten to over sixty beats or pulses. In this chapter, I theorize a typology of additive successions well suited to the analysis of such cycles – I classify patterns as either punctuated or split. Punctuated grooves arise when an established meter is interrupted at regular intervals by isolated measures in another meter. Split grooves comprise cycles with two or more subsections of approximately balanced lengths. My research forges connections between drum-kit practice, theories of rhythm and meter, and cognitive models of listener entrainment.5

In comparing irregular drumbeats with cycles of different durations, an important distinction must be drawn between two types of listener engagement. Listeners can easily entrain to shorter repeating cycles, developing an immediate, intuitive connection to a groove. With progressively longer temporal spans, the ability to entrain is attenuated.6 I posit that, as entrainment loses its efficacy, some listeners may choose to track irregularity through different means – either by counting, or by chunking and shifting between metric expectations.7 Where the entrainment model is colloquially described as feeling the groove, the other strategies could be described as thinking the groove. The boundary between the two modes of attending is fluid and will vary for each listener; differences in tempo complicate matters further.8

Moreover, in transcribing grooves with larger repeating cycles, there is often more than one viable arrangement of measures and time signatures.9 Whereas much music with a drum kit (rock, jazz, hip-hop, electronic, etc.) fits unproblematically into a 4/4 meter, even grooves with modest irregularities confound the straightforward mapping between meter and time signature that is often taken for granted in score-based musical traditions. Indeed, even the distinction between compound duple (6/8) and simple triple (3/4) meters can be difficult in the absence of a score.10 The transcriptions in what follows are all my own; most could be re-barred and some admit alternative beat-levels (e.g. my 11/4 may be another listener’s 11/8 or vice versa). My use of traditional European notation follows the practice of commercially available transcriptions of this music and that seen in private instruction common to neighbourhood lesson studios and institutions of higher education. Nevertheless, it remains a coarse shorthand for representing the sonic texts in question – not (as in the case of the classical score) the text itself. The best way to engage with my analysis involves finding and listening to the songs; this work is based on the original, studio-recorded album versions of each song, almost all of which can be found and heard online.

Regarding the repeating cycles under consideration, my criteria are as inclusive as possible: a groove is understood as any pattern of musical sounds that establishes a cyclic structure, and the cycles in question may be long enough to demand multiple meter changes. For example, I include a repeating pattern of sixty-one eighth notes in Radiohead’s ‘Paranoid Android’ (1997), but I would never transcribe the passage in 61/8 time – I hear four measures of 4/4, three of 7/8, and one of 4/4. In what follows, I often employ nested brackets to represent the subdivision structures of complex spans.11 The ‘Paranoid Android’ groove would be ((8,8)(8,8))((7,7)(7,8)). This method has the advantage of leaving certain potentially ambiguous features of the groove (e.g. beat level or time signature) open to interpretation.

In the songs analysed – mostly rock but admitting several outliers – the snare backbeat is often the most salient drumbeat cue and its metric role is the most codified of any drum-kit function, indeed, perhaps of any musical utterance. In 4/4 grooves, I hear the backbeat as exemplifying what Christopher Hasty calls ‘metric continuation’: an articulation that simultaneously extends the duration of an earlier counterpart, while itself demarcating a point of metric salience.12 In metrically irregular grooves, the snare retains this metric-functional role, aiding listeners in parsing the unfamiliar structure. Often this happens by imitating the familiar 4/4 backbeat as closely as possible within the irregular metric context. Less frequently the alternation of ‘forebeat’ (commonly articulated by the kick drum) and snare backbeat is more radically reimagined, or else the drumbeat abandons the backbeat trope altogether. I found one other common drumbeat option: undifferentiated articulation (i.e. using the same drum) of the beat or pulse level, or of a salient rhythmic pattern.

Punctuated Irregular Cycles

I refer to patterns in which one meter predominates, interrupted at regular intervals by measures in a second meter, as punctuated irregular cycles. Without exception, the interrupting change of meter comes at the end of the repeating cycle (or, put differently, exceptions to this trend are so rare that they foster ambiguity). The language that Scott Murphy uses in his discussion of Platonic-Trochaic successions is well suited to my analysis: both projects concern cycles made up of a run (a stable repeating pattern) and a comma (an interruption that punctuates that pattern).13 A heavy 11/4 groove in Tool’s ‘Right in Two’ (see Example 7.1) demonstrates a relatively simple punctuated structure, in which a single two-beat group punctuates an otherwise triple metric fabric (i.e. 3+3+3+2). In Murphy’s terms, the run comprises three groups of three, and the comma is the final two-unit group. I have transcribed the groove as comprising alternating measures of 6/4 and 5/4 time, approximating the measure lengths found in a familiar 4/4 backbeat, but there are other plausible alternatives. A transcription showing three measures of 3/4 and one of 2/4 would highlight the punctuated nature of the cycle, while a consistent 11/4 meter would reflect the regular patterning at the deeper hierarchical level of the phrase.

Example 7.1 A punctuated 11/4 groove in Tool’s ‘Right in Two’ (2006): 5:20

The drums are crucial in expressing the structure of this groove: an alternation of kick and snare stretches the standard backbeat to accommodate the three-beat spans, delaying the snare until every third beat. When the more familiar, two-beat backbeat alternation arrives at the end of the cycle, it expresses power and confidence, propelling the groove forward. The cymbals also participate in distinguishing the two-beat punctuation, switching from hi-hat eighths to emphatic quarter-note crashes.

Table 7.1 lists forty-one grooves with punctuated irregular cycles, organized according to drumbeat. Some songs contain more than one such groove. In the column that gives the cardinality of each cycle, I use an Asterix (*) to denote a sub-tactus pulse (i.e. at the eighth-note level or the quarter note in a double-time groove) and a double-sword (‡) to denote the level below that (usually that of the sixteenth note).

Table 7.1 Examples of punctuated irregular cycles

| Drums | Meter | Artist—Song (year) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Run | Comma | Cardinality | |||

| Kick-Snare Alternation | Backbeat; run has simple subdivision | 4 (×2) | 3 | 11* | Devo—‘Blockhead’ (1979) |

| 2 (×5) | 1 | 11 | King Gizzard & the Lizard Wizard—‘Gamma Knife’(2016) | ||

| 4 (×2) | 5 | 13 | King Crimson—‘Starless’ (1974) | ||

| 2 (×5) | 3 | 13* | Dream Theater—‘Metropolis Part 1: The Miracle and the Sleeper’ (1992) | ||

| 4 (×3) | 3 | 15 | TTNG—‘Gibbon’ (2008) | ||

| Yes—‘Siberian Khatru’ (1972) | |||||

| 5 | 17 | TTNG—‘Panda’ (2008) | |||

| 4 (×4) | 3 | 19‡ | Dream Theater—‘Scene Six: Home’ (1999) | ||

| Frank Zappa—‘Keep it Greasy’ (1979) | |||||

| Mahavishnu Orchestra—‘Celestial Terrestrial Commuters’ (1973) | |||||

| 5 | 21* | UK—‘In the Dead of Night’ (1978) | |||

| 7 | 23* | Dream Theater—‘Metropolis Part 1: The Miracle and the Sleeper (1992) | |||

| 4 (×6) | 5 (×2) | 34‡ | Dream Theater—‘Metropolis Part 1: The Miracle and the Sleeper’ (1992) | ||

| 4 (×7) | 5 | 33* | Phish—‘Split Open and Melt’ (1990) | ||

| 4 (×12) | (2,4)(1,4) | 61‡ | Metallica—‘Master of Puppets’ (1986) | ||

| 5 (×2) | 7 | 17 | Tool—‘The Grudge’ (2001) | ||

| 5 (×3) | 3 (×2) | 21 | Muse—‘Animals’ (2012) | ||

| (3,3,2) | 23 | Tool—‘Hooker with a Penis’ (1996) | |||

| 7 (×3) | 8 | 29* | Dream Theater—‘Scene Six: Home’ (1999) | ||

| Nine Inch Nails—‘March of the Pigs’ (1994) | |||||

| 4+5 (×3) | 4+4 | 35 | Dream Theater—‘The Count of Tuscany’ (2009) | ||

| Backbeat; run has compound subdivision | 3 (×4) | 3 | 15* | Queens of the Stone Age—‘I think I Lost My Headache’ (2007) | |

| 3 (×6) | 8 | 26* | Tori Amos—‘Virginia’ (2002) | ||

| 3 (×7) | 2 | 23* | Radiohead—‘You’ (1993) | ||

| 4 | 25* | Tori Amos—‘Carbon’ (2002) | |||

| Tori Amos—‘Spark’ (1998) | |||||

| Backbeat Variant; triple run | 3 (×3) | 2 | 11 | Allman Brothers—‘Whipping Post’ (1971) | |

| Tool—‘Right in Two’ (2006) | |||||

| Backbeat Variant; irregular run | 5 (×4) | (2,2,2) | 26* | TTNG—‘26 is Dancier than 4’ (2008) | |

| 5 (×7) | 7 | 42‡ | Tool—‘The Grudge’ (2001) | ||

| 7 (×7) | 9 | 58* | Tool—‘Forty Six & 2’ (1996) | ||

| (3,3,2) (×3) | (3,3,3) | 33* | Hail the Sun—‘Eight-Ball, Coroner’s Pocket’ (2012) | ||

| 5+4 (×2) | 3 | 21‡ | Frank Zappa—‘Keep it Greasy’ (1979) | ||

| Undifferentiated | 3 (×3) | 2 | 11 | Hail the Sun—‘Eight-Ball, Coroner’s Pocket’ (2012) | |

| 4 | 13(*) | Ben Folds—‘Bastard’ (2005) | |||

| Egg—‘I Will Be Absorbed’ (1970) | |||||

| Tool—‘Undertow’ (1993) | |||||

| Tori Amos—‘Carbon’ (2002) | |||||

| 5 (×2) | 4 | 14* | Dream Theater—‘A Nightmare to Remember’ (2009) | ||

| 4 (×5) | 5 | 25‡ | OSI—‘Memory Daydream Lapses’ (2003) | ||

| 8 (×2) | (3,4,3) | 26‡ | Mahavishnu Orchestra—‘One Word’ (1973) | ||

* Denotes probable sub-tactus pulse; ‡ denotes probable sixteenth-note pulse.

The most common subdivision structure for punctuated patterns retains the intuitive preference for quadruple hypermeter observed in most Euro-American music, rock and otherwise. Large-cardinality irregular grooves that follow this trend often comprise three measures in the initial meter followed by one in a new meter. Two variants of this three-plus-one hypermetric configuration are (1) a seven-plus-one patterning, as in Tool’s ‘Forty Six & 2’, and (2) cases in which the comma is better expressed by two measures, as in Muse’s ‘Animals’.

Thirty-three of the grooves analysed are based on a backbeat or a modified version of it, with the snare drum expressing metric continuation. In twenty-one of these, a 4/4 groove with a traditional backbeat serves as the primary meter. The punctuated elements of such grooves are sometimes based on the same backbeat, admitting subtle metric deletions or expansions to fit the punctuating meter. In the verse groove of Metallica’s ‘Master of Puppets’, every fourth measure can be heard as a distorted 4/4 with metric deletions within the first and third beats (i.e. the snare articulations retain their full quarter-note durations). Although the band’s practice of never recording to a click track makes it difficult to say with certainty, I hear an internal structure of (2,4)(1,4) at the sixteenth-note level. While commas that vary the backbeat are not uncommon, the prevailing strategy is to mirror the structural interruption to the meter with a stylistic interruption in the drumbeat – a fill. In the second verse of Dream Theater’s ‘Metropolis Part 1: The Miracle and the Sleeper’ (around 2:35), every third measure is abbreviated by an eighth note; drummer Mike Portnoy uses subtle fills to drive across these metric deletions to the downbeats of the following 4/4 measures. In this groove, the 4/4 backbeat is also modified in a way that prepares the recurring 7/8 measures. The second snare of every 4/4 measure is delayed by an eighth note, placing them in the final eighth-note position of those measures, recalling the placement of the final snare in many 7/8 backbeat variants.14

When 4/4 is not the primary meter, drummers usually retain the backbeat as much as possible within the metrically irregular context. Cycles that modify a compound quadruple (e.g. 12/8) feel, with the drummer marking the dotted eighth note with alternating kick and snare, account for five examples. Tori Amos is especially fond of stretching compound beats to form novel grooves. Larger cyclic patterns are found in ‘Carbon’, ‘Spark’, and ‘Virginia’ (see also ‘Datura’ in Table 7.2).15 Drumbeat patterns such as that seen in ‘Right in Two’, in which the alternation of kick and snare is played out every three beats, as opposed to the slower (five-, six-, and seven-beat) spans just described, suggest triple meter more readily than compound meter. The Allman Brothers’ ‘Whipping Post’ is another such example.

Table 7.2 Examples of split irregular cycles

Other primary meter options typically modify simple-time (4/4) backbeats trough deletion, as in 7/8 measures, or expansion. An example of the latter is the outro groove of TTNG’s ‘26 is Dancier than 4’, with a run comprising four repetitions of a 5/8 pattern followed by a six-pulse comma. The internal articulation of each subsection in the run is a quarter-note kick followed by three snares – a sixteenth, an eighth, and a dotted eighth. The first and third snare articulations are structural, resulting in a (4,3,3) pattern for each 5/8 measure.

Only eight of the punctuated grooves I surveyed eschew the backbeat possibilities just detailed, instead supporting a prominent rhythmic pattern with an undifferentiated articulation (i.e. playing the entire pattern on the same drum). The snare drum is the most common in this role, paralleling its importance in modified backbeat grooves. Many of the rhythmic succession represented in this category likewise have counterparts with modified-backbeat drum patterns (see e.g. Hail the Sun, ‘Eight-Ball, Coroner’s Pocket’, and Egg, ‘I Will Be Absorbed’); however, some successions are limited to this category. An instrumental near the three-quarters point in Dream Theater’s ‘A Nightmare to Remember’ has a pattern of (3,2,3,2,2,2), which I parse as a run of ten pulses (5,5) and a comma of four. In a recurring instrumental passage in OSI’s ‘Memory Daydream Lapses’ the ride cymbal subdivides a twenty-five-pulse cycle as (4,4,4,4,4,2,3) – a run of twenty and a comma of five. The initially even pulse is in a comfortable quarter note, making the five-sixteenth note comma especially jarring on early hearings. Some listeners may also entrain at the half-note level, parsing the pattern as (8,8,9).

Before moving on to split cycles, I consider a case where punctuated, large-cardinality groupings occupy regular metric frameworks. The rhythmic acrobatics of Swedish metal group Meshuggah are theorized by Jonathan Pieslak and Olivia Lucas, both of whom note the band’s penchant for cyclic irregular riffs, punctuated to fit phrase and formal boundaries based on 4/4 meter and foursquare hypermeter.16 What is remarkable about the band’s handling of these grooves is the functional promiscuity of the snare drum. Whereas the irregular cycle is almost always given by the guitars and bass, supported by the kick drum, and whereas the cymbals are almost always responsible for maintaining a steady quarter-note beat, allowing entrainment to the overarching foursquare organization of the groove, the snare is free to ally itself to either stratum. In my habit of hearing the snare as the leading metric cue in this music, the patterning of this drum has a decisive influence on my interpretation of Meshuggah’s various grooves. Thus, in the opening groove from ‘Stengah’ (Pieslak’s Example 7.3), where the snare supports an 11/8 riff on the third and sixth articulations in a (3,4,3)(3,4,5) sixteenth-note structure (until five repetitions lead to a 9/8 comma), that irregular organization is the dominant metric structure in my hearing. Conversely, in the opening of ‘Lethargica’ (Lucas’s Example 7.2), where the snare marks a slow half-time backbeat against the displaced 23/4 riff, I find it easier to move with the available underlying 4/4.

Split Irregular Cycles

Grooves of the split type are based on a cycle with two or more subsections, the lengths of which are approximately balanced. In the clearest split patterns, subsections are easily differentiated by a change in pulse grouping (e.g. shifting from 2s to 3s). Radiohead’s ‘Go to Sleep (Little Man Being Erased)’ exemplifies this strategy, alternating measures of 4/4 and 12/8.17 The change in meter is reinforced by a change in drumbeat, from standard backbeat in the 4/4 measures to a snare on every third eighth note in 12/8. Split patterns of this sort invite the listener to keep two metric schemas available at all times, shuttling between them as necessary.

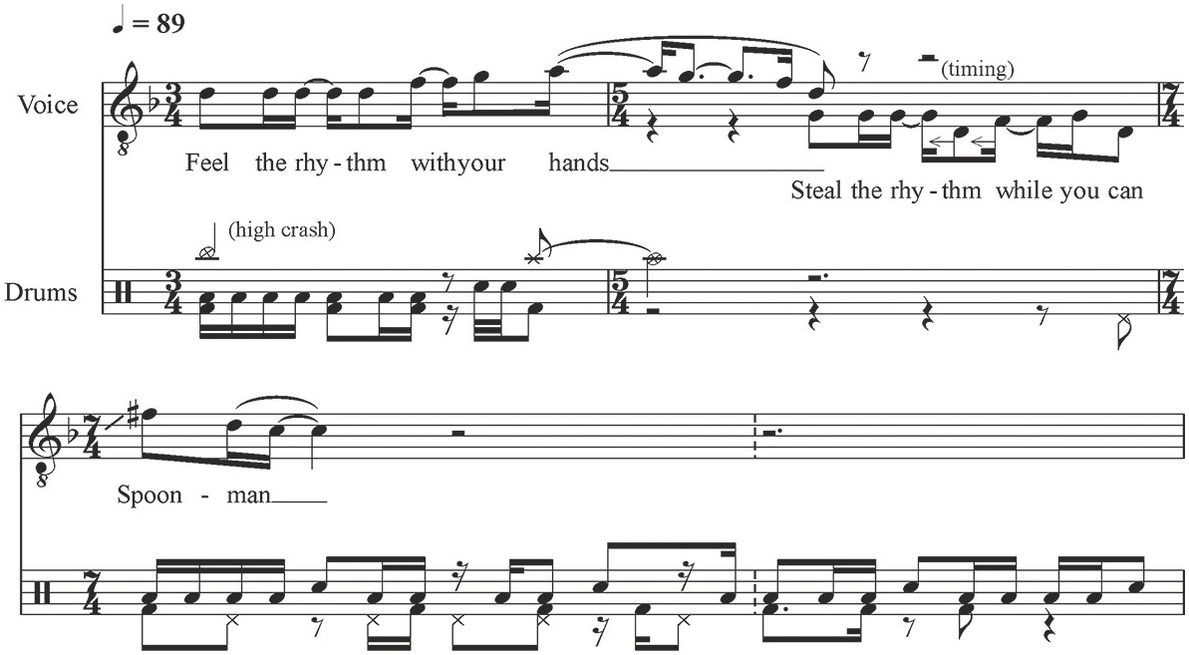

When no change of grouping occurs, cues in phrasing or arrangement are typically required to support a split interpretation. This is the case in Soundgarden’s ‘Spoonman’ (see Example 7.2). The repeating pattern of fifteen beats could be parsed as (4,4)(4,3) – suggesting a punctuated logic – but two features of the arrangement contradict this analysis. The first is the long instrumental pause through the second measure. In the absence of a continuous groove in any part of the rhythm section, the re-entry in the cycle’s third measure is marked as a new beginning, paralleling the first measure. Such parallelisms often indicate a split pattern, though they are seldom so clear. The second feature of ‘Spoonman’ that supports a split structure is the (3,2,3) grouping of the first half: the short drum fill marks beat three as closing a measure and the vocal phrasing establishes a more local parallelism between the first and sixth beats of the pattern (a transcription in 5/4 + 3/4 would better reflect the structure of the vocals, while my version prioritizes the drums). Without the stability of an ongoing 4/4 meter to connect the first two measures with the third, the punctuated possibility is untenable.

Table 7.2 catalogues fifty-nine split cycles. The most consistent trend within these grooves is the prevalence of two-part organization at the highest level, though three-and four-part structures are not uncommon. As with punctuated cycles, drumbeats derived from the backbeat predominate, accounting for forty-three groves. Twelve of the other sixteen use undifferentiated articulations, and the remaining four combine the two approaches.

Within split cycles with a backbeat-variant drumbeat, more than half (twenty-six grooves) are directly based on the 4/4 archetype; a further ten modify a compound- or triple-meter framework; and in the remaining seven irregularity is pervasive enough that comparison to a regular meter is less useful than simply considering the particulars at hand. With those rooted in the 4/4 backbeat model, the most common approach is a two-part split alternating between a septuple group and a quadruple one (the latter may require two measures, depending on hierarchical level). The first part invariably ends with a metric deletion, balanced by a second part without deletion. Examples include ‘Tattooed Love Boys’ by the Pretenders and ‘Make Yourself’ by Incubus. Fu Manchu’s ‘Pick-Up Summer’ expands the pattern, using a septuple sub-cycle as the base meter with only occasional 4/4 measures to begin the second part of the split: (7,7)(8,7) or (4,3)(4,3)|(4,4)(4,3) at the beat level. Björk’s ‘Crystalline’ demonstrates a related but distinct situation, leading with a measure of 4/4 and expanding the second part by an eighth note: (8,9) or (4,4)(4,5) in eighth notes.