Introduction

Spanish learning children (mono- and bi-lingual) gain verbal ability at a very young age (Grinstead, Reference Grinstead2000; Guasti, Reference Guasti2002; Montrul, Reference Montrul2004a), during their second year, when they show command of present tense and some past tense. Less frequent tense, mood and aspect forms are acquired later in development (Silva-Corvalán, Reference Silva-Corvalán2014). Once regular forms have been established, children (cross-linguistically) impose regularity on irregular forms, showing a pattern of overregularization. Pinker (Reference Pinker1999) devotes an entire chapter to the topic, giving examples from English such as I writed on it and she holded them, while Yang (Reference Yang2002, Reference Yang2016) devotes two books to a model accounting for such forms in regular, semi-regular and irregular linguistic phenomena. With a focus on overregularization of stem-changing verb forms, our study examines the mastery of present tense verb morphology by two groups of Spanish–English bilingual children in a dual-language immersion setting, heritage language (HL) speakers and second language (L2) learners.

Heritage speakers have the HL as their first language (L1), acquired in the home. The HL is a minority one in a majority language environment as, for example, minority Spanish in the majority English United States. Earlier research focusing on adult HL speakers has shown asymmetric grammatical competence in the HL compared to the L2 majority language and also in comparison with monolingual speakers of the same language (Montrul, Reference Montrul2008, Reference Montrul2016; Polinsky, Reference Polinsky2011, Reference Polinsky2018). Our project examines verbal inflection of Spanish heritage language (SHL) children and their Spanish second language (SL2) peers whose majority English environment is enriched by academic Spanish. Overall results (Fernández-Dobao & Herschensohn, Reference Fernández-Dobao and Herschensohn2019, described in section 3) indicated errors of overregularization of present tense forms that led us to our current study.

Given the importance of studying school age children (Montrul, Reference Montrul2018), the bilingual children in our study are fourth graders, nine to ten years old, who have been in a dual immersion program for five years, receiving a daily exposure of 50:50 English to Spanish. The immersion setting is known to promote bilingualism as well as biliteracy by enhancing both quality (variety of different speakers) and quantity (number of utterances) of Spanish in the environment (Collier & Thomas, Reference Collier and Thomas2004, Reference Collier and Thomas2017). Our area of investigation, present tense morphology of stem-changing and irregular verbs, is tested through written production tasks for the two bilingual groups and a third group of majority Spanish controls. Present tense is early acquired in L1A and should be solidly established by age 10 for both HL and L2 child learners, whose literacy skills should also be solid by that age. Compared to other tenses (e.g., preterite, imperfect), present tense should be the least vulnerable to instability (Montrul & Silva-Corvalán, Reference Montrul and Silva-Corvalán2019).

The first section of the paper provides the background in giving a brief overview of Spanish and English verbal morphosyntax. Then we examine the notion of asymmetric mastery by HL and L2 bilinguals, focusing on the issue of overregularization in verbal morphology development, which will lead us to our research questions. The following sections present the design of the study – participants, instruments, and data analysis, followed by the results and the discussion.

Background

Spanish and English verbal morphosyntax

Spanish verbs show robust inflection for person, number, tense, aspect and mood (PN, TAM) and comprise three distinct regular conjugation classes (with –ar, –er and –ir endings in the infinitive). Person and number are marked on six persons (first, second, third singular and plural) with consistent uniform suffixes for the three regular conjugation classes. In their most extended forms, Spanish inflected verbs include after the stem a conjugation class theme vowel (–a–, –e–, –i–), a TAM mark and a PN ending (Bermúdez-Otero, Reference Bermúdez-Otero2013; Harris, Reference Harris1987). For instance, for the imperfect form hablábamos ‘we were talking’, the stem habl– of infinitive hablar ‘to talk’ is followed by the theme vowel –á–, the TAM marker –ba– and the PN ending for first person plural –mos.

In addition to the three regular classes, there are a number of irregular verbs, whose irregularity is morphologically marked by suppletive forms, stem changes and inflectional differences from the regular conjugation paradigm. These verbs range from very suppletive high frequency ones, such as ir ‘to go’, to those that largely conform to a regular conjugation pattern but differ by diphthongizing their stressed vowel. For example, jugar ‘to play’ alternates juega ‘s/he/it plays’ with jugamos ‘we play’. We refer to these as stem-changing or diphthongizing verbs. They are quite systematic in their slight deviation from the regular conjugation. Nevertheless they constitute an exception to the regularity, and that exception must be learned as a lexical characteristic for each stem-changing verb.

HL and L2 bilinguals

Heritage language speakers have been subjects of research for over two decades (e.g., Montrul, Reference Montrul2002, Reference Montrul2004b; Polinsky, Reference Polinsky2006), with HL studies multiplying in recent years (for an overview, see Montrul, Reference Montrul2016, and Polinsky, Reference Polinsky2018). Although earlier researchers described HL acquisition as “incomplete” (Montrul, Reference Montrul2008; Polinsky, Reference Polinsky2006), more recent accounts suggest that HL competence is different, rather than incomplete (Pascual y Cabo & Rothman, Reference Pascual y Cabo and Rothman2012; Cuza, Reference Cuza2016); however, the terminology is still highly debatable and has led to animated exchanges (Bayram, Kupisch, Pascual y Cabo & Rothman, Reference Bayram, Kupisch, Pascual y Cabo and Rothman2019; Domínguez, Hicks & Slabakova, Reference Domínguez, Hicks and Slabakova2019; Kupisch & Rothman, Reference Kupisch and Rothman2018; Montrul & Silva-Corvalán, Reference Montrul and Silva-Corvalán2019; Otheguy, Reference Otheguy2019).

Montrul has pioneered work on HL grammars and has also observed similarities between HL and L2 speakers, noting that both groups share difficulties with inflectional morphology. In a series of studies, she compared the two groups in terms of morphological accuracy, using data from college students (Montrul, Reference Montrul2010, Reference Montrul2011; Montrul, Foote & Perpiñán, Reference Montrul, Foote and Perpiñán2008). For instance, Montrul (Reference Montrul2011) compared HL and L2 Spanish speakers matched for proficiency on oral and written tasks testing tense-aspect (TA, preterite/imperfect) and mood (M, indicative/subjunctive). Monolingual Spanish controls were at ceiling, but the two bilingual groups showed varying strengths, indicating differences between HL and L2 acquisition: HL speakers scored better on oral tasks, while L2 learners surpassed HL speakers on written tasks. Both groups had problems with morphosyntax, often using default forms for more specified ones.

Benmamoun, Montrul and Polinsky (Reference Benmamoun, Montrul and Polinsky2013), summarizing grammatical features of HL phonology, morphology and syntax, note that in the verbal domain tense is far more robust than aspect and mood. They suggest four contributing factors for the differences found between the HL version and the majority language version of a language. First, HL speakers hear more limited input as children so may not receive a sufficient amount to result in complete mastery. For example, HL Spanish speakers in a majority English environment do not show the full range of subjunctive mood that monolinguals in Mexico do (Benmamoun et al., Reference Benmamoun, Montrul and Polinsky2013). Another factor is attrition, whereby a feature established in early L1 grammar is lost as the child matures and becomes more fluent in the L2. Polinsky (Reference Polinsky2011) shows that adult HL Russian speakers are at chance in comprehension of object relative clauses, unlike child HL speakers and adult and child monolinguals. The cross-sectional comparison of child and adult HL speakers strongly suggests attrition of subordinate clause mastery as HL speakers mature. A third factor is influence of the majority language, which for many HL speakers becomes their dominant language (see discussion of Cuza & Pérez-Tattam, Reference Cuza and Pérez-Tattam2016 below). A final factor that Benmamoun et al. (Reference Benmamoun, Montrul and Polinsky2013) point to is the incipient changes in L1 input to HL children, given the fact that the older generation is itself modifying its native tongue under influence from the new environment. An additional element to take into consideration is literacy, since heritage speakers typically are not formally educated in the HL (Pascual y Cabo & Rothman, Reference Pascual y Cabo and Rothman2012).

Meisel (Reference Meisel2013) notes that the overwhelming majority of HL studies investigate adult HL speakers and advocates analysis of ongoing HL acquisition of both simultaneous and sequential bilingual children. Kupisch and Rothman (Reference Kupisch and Rothman2018) observe that studies of European HL often involve simultaneous child bilinguals, whereas research on American HL usually involves adults. An exception is the work by Cuza (e.g., Reference De Jong2016), who has looked at the grammatical competence of HL children in English language academic settings. Cuza and Pérez-Tattam (Reference Cuza2016), for instance, investigated predominance of masculine as default gender and nominal word order discrepancies of HL children compared to monolingual controls. They argued that the children's Spanish nominal gender had been revised due to contact with genderless English, which also shows a different adjective-noun order. Cuza (Reference Cuza2016) documented divergent question inversion by Spanish HL children (8;4 years), also explained by the influence of majority English.

Child L2 learners immersed in a language usually have the opportunity to fully develop their grammar if they are young enough and have sufficient exposure (Carroll, Reference Carroll2017; Montrul, Reference Montrul2016). As the Cuza studies show, what amount is sufficient is a question that remains unanswered. The educational model of dual immersion (Collier & Thomas, Reference Collier and Thomas2004) provides an environment of exposure to two languages in an academic setting; few studies have looked at the minority language in this setting. Herschensohn, Stevenson and Waltmunson (Reference Herschensohn, Stevenson and Waltmunson2005) investigated the mastery of present tense Spanish verbs by six- to seven-year-old Anglophone children in such a dual immersion setting. Collecting comprehension and oral production data from 26 Anglophones and five Hispanophones, they demonstrated a significant difference between comprehension and production for the Anglophone children (78% and 28% accuracy respectively). Verbal errors of production were far more frequently wrong inflection, rather than default inflection (the typical adult error), indicating that the children were focused on the inflectional affixes even if unable to produce them accurately.

Another study of children in a dual language academic setting is that of Montrul and Potowski (Reference Montrul and Potowski2007), who investigated gender assignment and agreement with Mexican monolingual controls and three groups of Spanish–English bilinguals, L2 learners, sequential and simultaneous HL speakers. Examining two age clusters (6–8 and 9–11 years) they used two tasks, a form-focused elicitation and a meaning-focused re-telling of Little Red Riding Hood in Spanish. Results indicated that bilinguals had incomplete command of gender assignment and agreement, that sequential HL speakers outperformed simultaneous ones, and that dual immersion education mitigated decline in gender ability over time. Unlike HL children in English language educational environments (cf. Cuza & Pérez-Tattam, Reference Cuza and Pérez-Tattam2016) these HL children showed a decline in gender errors over time, with the older group demonstrating a lower percentage of errors than the younger one. Finally, the HL and L2 children performed better on the meaning-focused narration, where they chose their vocabulary, than the form-focused elicited production task.

In sum, the studies cited point to several issues contributing to differences that grammars of minority HL speakers manifest compared to monolingual speakers in a majority language environment. Limited exposure in the minority environment (perhaps only the home), reduced literacy training, contact with majority L2 and even task design (e.g., elicited production) are factors influencing HL children. The preponderance of studies on adult HL speakers points to the need for child HL studies. The similarities in morphosyntactic reduction shown by HL and L2 learners (e.g., Montrul, Reference Montrul2011) indicate a need to compare these two groups in a childhood population still in developmental stages of L1 and L2 growth.

Overregularization in morphology acquisition and processing

Children learning Spanish as an L1 gain verbal ability during the second year of life (Grinstead, Reference Grinstead2000; Guasti, Reference Guasti2002; Montrul, Reference Montrul2004a), showing PN contrast from the earliest ages. Silva-Corvalán's (Reference Silva-Corvalán2014) detailed documentation of two bilingual siblings learning majority English and minority Spanish provides a longitudinal case study of grammatical development. By the end of the second year the children had about 25 Spanish verb types using present and some preterite. During their third year, they produced more verb types, more varied TAM, and regularization of irregular stems and suffixes. During the next three years simple indicative tenses were produced, but the less frequent and more complex forms were unstable due to limited exposure, as documented elsewhere (cf. Miller & Schmitt, Reference Miller, Schmitt and Grinstead2009, Reference Miller and Schmitt2012).

L1 and L2 learners manifest distinct stages of development including item learning, mastery of regular forms, overregularization, and eventually appropriate use. Three theoretical approaches have been proposed to describe acquisition, storage and access to morphological inflection. The single-mechanism model (e.g., Langacker, Reference Langacker2000; Rumelhart & McClelland, Reference Rumelhart, McClelland, McClelland and Rumelhart1986) uses general learning mechanisms, network associations and frequency of input to account for both regular and irregular inflection by listing all items. The dual-mechanism model (e.g., Pinker, Reference Pinker1999; Pinker & Prince, Reference Pinker and Prince1988) uses domain-specific learning mechanisms and proposes distinct means of storage and access for irregular (words) and regular (rules) morphology. A rule-based mechanism pairs a regular morpheme such as English past –d to verb stems, while irregular forms are listed as “words” such as come associated with past came. The variational approach (Yang Reference Yang2002, Reference Yang2016; Yang & Montrul, Reference Yang and Montrul2017) uses general learning mechanisms in domain-specific hypothesis space, frequency of input and probabilistic weighting of rules and exceptions. Yang's model quantitatively predicts learning patterns and eventual storage/access, gives a motivated account of mini-conjugations (contra dual mechanism, which sets up a binary system) and explains lack of irregularization (contra single mechanism that allows it).

Assuming unsupervised learning in L1A, Yang convincingly shows that developing children draw categorical distinctions in linguistic productivity to infer rules governing phonology, morphology and syntax. Rules are if … then conditions that specify structural description and structural change. He argues that “as the number of exceptions to a rule increases, the real-time processing cost associated with the rule also increases accordingly […] it becomes more efficient to lexically list everything and there will be no productive rules” (Yang, Reference Yang2016, 41). He proposes the Tolerance Principle that weighs the proportion of exceptions to rule and mathematically establishes a threshold of productivity. The percentage of exceptions is inversely related to the size of the data set. For example, English verbs with [i] (e.g., feed-fed, meet-met) may show vowel shift in past as i → e/ ___ [d,t]; that is, the high vowel becomes mid before an alveolar stop in past tense. If a child has ten verbs in this class, she can tolerate up to four exceptions and still maintain the rule. In initial stages, children acquire irregular rules for mini-conjugations such as feed-fed or bring-brought, since their repertoire mainly comprises frequent irregulars; but those mini-rules become lexicalized (frozen lists) as too many regulars meeting the same environment are added to the lexicon. As for regular verbs with past tense –d, children reach the threshold of productivity at total repertoire of 1000, with 130 exceptions. Once this default/elsewhere rule is established, it may be overapplied, providing an explanation for overregularization. This account also explains lack of irregularization (regulars are never irregularized), since irregulars constitute lexicalized rule classes. This model not only displays the positive points of the other two models, but also provides a very specific formula for predicting the numerical threshold for productivity and an explanation for the stages of acquisition. Adapting the Tolerance Principle to other populations predicts that there should be stages that encompass rules for regular and mini-conjugations, overregularization of irregulars, frequency effects related to a number of lexical factors and no evidence of irregularization.

Several studies (Aguirre, Reference Aguirre2006; Bowden, Gelfand, Sanz & Ullman, Reference Bowden, Gelfand, Sanz and Ullman2010; Clahsen, Aveledo & Roca, Reference Clahsen, Aveledo and Roca2002; Eddington, Reference Eddington2009; Mayol, Reference Mayol, Nurmi and Sustretov2003; Yaden, Reference Yaden2007) have compared single-mechanism and dual-mechanism morphology models for processing and acquisition of Spanish verbs for both L1 and L2. Of these studies, only Mayol considered Yang's approach, which she argued to be the best account for her data. In all the studies, the populations showed evidence of overregularization, virtually no evidence for overextension of irregular forms (irregularization), and often frequency effects for both regular and irregular verbs.Footnote 1 The frequency effects found for all verbs detract from the Words and Rules model (which claims that regulars should not be sensitive to frequency), whereas rule-like overregularization detracts from single-mechanism accounts (since overregularized forms are never in the input, the basis for learning). Indeed, the influence of frequency and other weighting factors and the mini-rule treatment of systematic mini-conjugations seen in these studies lend support to Yang's model, also underlined by Aguirre (Reference Aguirre2006), who notes that Spanish L1 children manifest verbal mini-paradigms.

Clahsen et al. (Reference Clahsen, Aveledo and Roca2002) examined production data from 15 Spanish learning children (1;7-4;7) to determine if they overused regular inflections and the open first conjugation class. They found 4.6% errors in irregular verbs, compared to .001% for regular verbs, indicating a clear asymmetry between irregular and regular morphology that they interpreted as evidence for the dual-mechanism approach, also advocated by Clahsen, Felser, Neubauer, Sato and Silva (Reference Clahsen, Felser, Neubauer, Sato and Silva2010), who compared L1 and L2 processing of regular and irregular morphology.

Bowden et al. (Reference Bowden, Gelfand, Sanz and Ullman2010), studying L1 and L2 adults, found a distinction between open-class –ar (first conjugation) regulars that showed no frequency effects and second-third class regulars that did. Stem-changing forms from all three classes were sensitive to frequency effects, leading the authors to conclude that for native speakers the single-mechanism model is incompatible for storage and accessing Spanish verbal morphology.

Research questions

Spanish verb morphology has been extensively examined in terms of L1 and L2 acquisition, storage and accessing of regular and irregular forms by developing and adult native speakers and by adult L2 learners. However, there has been scarce research dealing with child bilinguals. The present study examines production of stem-changing and irregular present tense verbs in two populations of child Spanish–English bilinguals, 9–10 year-old SHL speakers and SL2 learners in a Spanish–English 50:50 dual immersion academic setting, and compares them to age-matched Spanish majority children. Herschensohn et al. (Reference Herschensohn, Stevenson and Waltmunson2005) found that dual immersion first graders (5–6 years old) had limited command of present tense morphology. Our study focuses on fourth graders (9–10 years old), who have been in dual immersion for five years and therefore can be expected to have a working knowledge of present tense morphology. Using Yang's framework, we expect evidence of regular and mini-conjugation rules, frequency effects and no evidence of irregularization.

Montrul and Potowski (Reference Montrul and Potowski2007), who studied 6–11 year old children in an immersion setting, found distinct results in form-focused versus meaning-focused tasks. We analyze production of stem-changing and irregular present tense verb morphology using two written tasks, a form-focused task, that elicits production of preselected verb types, and a meaning-focused task, expected to elicit highly frequent verb types. Present tense verb inflection is early acquired (by the third year) by monolingual majority language children. However, given the extensive evidence for overregularization and frequency effects by both L1 children and L2 adults, we expect non-target responses for stem-changing verbs and frequency effects by both SHL and SL2 children. We also expect that more frequent verbs should show lower error rates than less frequent ones (Bowden et al., Reference Bowden, Gelfand, Sanz and Ullman2010). As for the path of morphology acquisition and storage, we will reconsider Yang's proposals to determine their applicability to the two populations under study.

Our research questions are the following:

1. How do SHL and SL2 children compare to majority Spanish controls in their morphology mastery of stem-changing and irregular present tense Spanish?

2. How does task design – form-focused or meaning-focused – affect morphological accuracy?

3. How well does the Tolerance Principle account for the data from Spanish verb morphology? Is there evidence of:

a. regular rules (accuracy of regular conjugation)

b. mini-conjugation rules (accuracy of stem-changing conjugation)

c. frequency effects (greater accuracy with higher frequency)

d. overregularization of irregulars

e. no irregularization?

Method

Participants

We tested 77 children (nine to ten years old): 62 English-Spanish bilinguals and 15 majority Spanish speakers. All bilingual children were enrolled in a dual immersion program, 21 of them were SHL speakers and 41 SL2 learners.

Following Valdés (Reference Valdés, Peyton, Renard and McGinnis2001), we considered any child raised in a home where Spanish was spoken and exposed to the language from birth to be a SHL speaker. The 21 SHL children in our study came from Hispanophone families, as reported by the parents to the school district and confirmed by the teachers. Spanish was the dominant language of 13 of them and 11 were English language learners. Because this information was furnished by the school district and confirmed by the teachers, we did not administer a language background questionnaire. While most SHL children were of Mexican origin, the group also included children exposed to Peninsular, Central and South American varieties of Spanish at home. One child of Cuban origin was not included in the study, since Caribbean varieties manifest final consonant elision (thus leveling present tense verb morphology). As in most dual immersion settings (see De Jong, Reference De Jong2014), the SHL children in our study illustrated a variety of linguistic backgrounds and language dominance profiles. While data on the amount of exposure to Spanish outside school was not available, they all had the common denominator that Spanish was their first language and the language spoken at home by at least one parent.

The 41 SL2 children were native English speakers. They had learned Spanish as an L2 in the school setting. At the time of the study, they had been enrolled in the dual immersion program for five years, since kindergarten.

Dual immersion programs integrate minority language-speaking children – in our case, Spanish L1 children – and majority language-speaking children – English L1 children – in the same classroom (Collier & Thomas, Reference Collier and Thomas2004, Reference Collier and Thomas2017). The 62 bilingual children in our study were fourth graders from two public schools located in a medium-size city in the US northwest. Both schools followed the same 50:50 dual immersion model. Since kindergarten, children received half of their instruction in Spanish and half in English. They were taught math and social sciences in Spanish and language arts in English. No explicit grammar instruction was provided. Literacy was introduced both in English and Spanish.

The 15 majority Spanish children were born and raised in Spain. They serve as the control group and will be referred to as the Spanish first language (SL1) children.Footnote 2

SHL and SL2 children had been assessed on their Spanish reading, writing, listening and speaking proficiency by the school district using the STAMP 4Se assessment test (Avant Assessment, 2017). This test has been specifically developed for elementary school students, grades 2 to 6, adapting the ACTFL Proficiency Guidelines (ACTFL, 2012) to an age-appropriate population.Footnote 3 The results of the test confirmed that both groups of dual immersion students had developed some level of literacy in Spanish. Most SHL and SL2 children placed at an Intermediate-Low or Mid level in reading. However, their writing skills were lower, mostly at a Novice-Mid level for the SL2 learners and at a Novice-High or Intermediate-Low level for the SHL children. As for oral skills, most SHL and SL2 children placed at Novice-Mid or Novice-High in speaking but a higher level in listening, Intermediate-Low or Mid level for SL2 learners and Intermediate-Mid or High level for SHL speakers.

Instruments and procedure

The current study is part of a larger project examining comprehension and production of present tense verbs. Drawing from earlier studies of children in dual immersion – Herschensohn et al. (Reference Herschensohn, Stevenson and Waltmunson2005) and Montrul and Potowski (Reference Montrul and Potowski2007) – three different instruments, a listening task and two writing tasks, were designed for the project. The analysis of the two production tasks revealed no significant differences in inflectional suffix accuracy between SHL and SL1 speakers, while SL2 learners were significantly less accurate than both SHL and SL1 speakers. However, “contrary to what we have seen for number, person and tense morphology, stem errors were frequent among SHL as well as SL2 children” (Fernández-Dobao & Herschensohn, Reference Fernández-Dobao and Herschensohn2019, 20). Prompted by this previous research, the present study focuses on stem-changing and irregular verbs, analyzing production data from the two writing activities, a form-focused and a meaning-focused task.

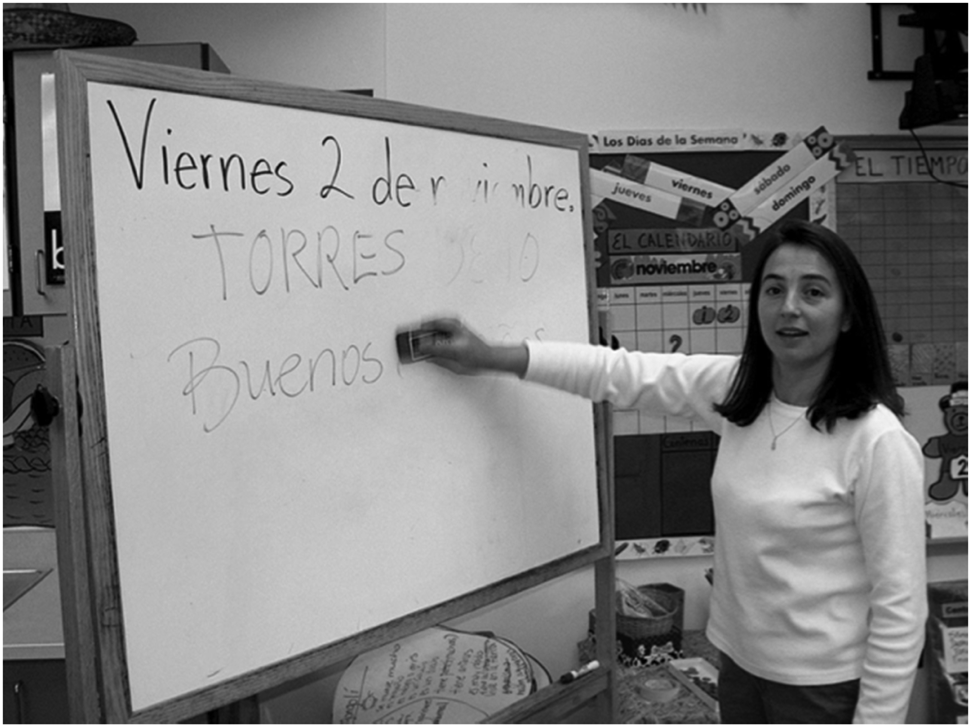

The first writing activity was the form-focused production task (FFPT), adapted from Herschensohn et al. (Reference Herschensohn, Stevenson and Waltmunson2005) – see Appendix A. Children were shown 10 photographs, all taken in a classroom and depicting common classroom activities. With each photograph we provided a verb (infinitive form). Children had to conjugate the verb in the simple present to answer the question: ¿qué hace/n? ‘what do/es s/he/they do?’. Half of the pictures showed one person and therefore required the use of a third person singular form. The other half showed two people and asked for a third person plural form. Children completed this task after a listening activity involving 20 pairs of similar photographs, each accompanied by a sentence with a simple present third person verb, half of them singular and half plural. This helped to prompt the use of simple present and minimize present progressive forms. Two practice items were developed:

(1) ¿Qué hace? Borra la pizarra

what do-3SG erase-3SG the-F-SG whiteboard-F-SG

‘What does she do? She erases the whiteboard’

(2) ¿Qué hacen? Hablan por teléfono

what do-3PL speak-3PL by telephone-M-SG

‘What do they do? They talk on the phone’

As shown in Table 1, the ten verbs included in the task were frequently used in the school setting, selected from Herschensohn et al. (Reference Herschensohn, Stevenson and Waltmunson2005) with the help of one of the teachers to make sure they would be familiar to fourth graders. Most of them were –ar verbs – since most Spanish verbs belong to this open class, but there were also –er and –ir verbs. Six of them had an invariable stem while the other four were stem-changing verbs requiring diphthongization of the mid-vowel in stressed syllables: cerrar ‘to close’, querer ‘to want’, pensar ‘to think’ and contar ‘to count’. The first three verbs present an ie diphthongization in the third person of the present tense: cierra/n, quiere/n, piensa/n. The fourth one shows an ue diphthongization: cuenta/n. In this study, we analyze these four verbs, examining both the stem vowel and the inflectional suffix. Mastery of inflectional suffix indicates the ability to conjugate the verb, whereas mastery of the diphthongization indicates accurate categorization of the stem-changing verb as belonging to the mini-paradigm.

Table 1. Verbs (infinitive) used in the form-focused task

a shows diphthongization of the stem in the present tense

The second task, the meaning-focused production task (MFPT), was a free composition. Children were asked to write an email to a new pen-pal from a Spanish speaking country – see Appendix B. They were told to introduce themselves, describe their families, friends, hobbies, school, etc. and ask their new friends about these same topics. Instructions focused exclusively on content, not form, but the topic prompted the use of simple present tense in all persons. Children could choose which verbs to use and how long their emails would be, although the topic influenced and limited their vocabulary choices. Table 2 presents the list of verbs used by the children ordered by frequency in our corpus. It includes verbs with regular present tense forms, stem-changing verbs requiring diphthongization of the stem in stressed syllable and verbs with irregular present tense forms.Footnote 4

Table 2. Verbs (infinitive) used in the meaning-focused task

a shows diphthongization of the stem in the present tense

b shows irregular stem and/or suffix transformation in the present tense

All children were tested in the school setting. Tasks were not counterbalanced. Children completed the two tasks in class, during the half of the day reserved for Spanish instruction. The first activity lasted approximately 15 minutes. For the second one, the email writing task, they were given as much time as needed until the end of the class session, approximately 30 minutes.Footnote 5

Data analysis

We analyzed all stem-changing and irregular verb forms produced in terms of both stem accuracy and inflectional suffix accuracy. The FFPT required use of four stem-changing verbs which show diphthongization of the stem in the present tense, but regular inflectional affixes. First, we identified those sentences that involved use of one of the stem-changing verbs. We ignored those sentences in which children used a present progressive form (30 instances) or a different verb than the one provided. The number of stem-changing forms conjugated by each child ranged from 4 to 0 (when the child used only present progressive forms). A total of 275 forms were identified.

We analyzed these 275 forms for stem accuracy and classified them in three groups. The following examples, all from the data produced by the children in the current study, illustrate these three categories: (a) correct stem, with the required stem change (Example 3); (b) overregularized stem, with a non-diphthongized stem form (Example 4); and (c) wrong stem, with an incorrect stem change (Example 5). Suffixation errors (that is, PN, TAM and conjugation class errors) were analyzed separately.

(3) Correct stem: Cierra los ojos

close-3SG the-M-PL eye-M-PL

‘She closes her eyes’

(4) Overregularized stem:

*Contan (cuentan) los números

count-3PL the-M-PL number-M-PL

‘They count the numbers’

(5) Wrong stem: *Quiren (quieren) los libros

want-3PL the-M-PL book-M-PL

‘They want the books’

In the MFPT, the emails varied in length (range: 27-185 words, median: 77 words) and number of present tense verbs required (range: 2-30 verbs, median: 11 verbs). Therefore, we started by identifying all contexts in which a present tense form was required. These included regular, stem-changing, and irregular forms that we illustrate below with correct examples taken from the data collected in the study. Regular forms take the stem of the infinitive and regular inflection (Example 6). Stem-changing forms require diphthongization of the stem vowel in stressed syllables, but show regular suffix inflection (Example 7). Irregular forms, in this study, are all those other forms that cannot be directly derived from the infinitive because of an irregularity in the stem, the inflectional suffix, or both (Example 8).

(6) Regular form: Yo vivo en Seattle (Infinitive: vivir)

I-1SG live-1SG in Seattle

‘I live in Seattle’

(7) Stem-changing form:

¿Qué deporte juegas? (Infinitive: jugar)

what sport-M-SG play-2SG

‘What sport do you play?’

(8) Irregular form:

¿Cuál es tu nombre? (Infinitive: ser)

what be-3SG your-M-SG name-M-SG

‘What is your name?’

Stem-changing and irregular forms were further analyzed for accuracy. Stem-changing forms were analyzed for stem accuracy and classified as correct stem, overregularized stem or wrong stem forms, as described above (see Examples 3, 4 and 5). Irregular forms were analyzed for stem/suffix overregularization (Example 9) and wrong stem/suffix errors (Example 10). Finally, all stem-changing and irregular forms were also analyzed for inflectional suffix accuracy: that is, PN, TAM and conjugation class accuracy.

(9) Overregularized irregular stem/suffix:

*Esto (estoy) muy contento

be-1SG very happy-M-SG

‘I am very happy’

(10) Wrong irregular stem/suffix:

Yo *sio (soy) muy feliz

I be-1SG very happy-M-SG

‘I am very happy’

Results

In this section we present the results of the accuracy analysis of the stem-changing and irregular present tense verbs used by the three groups of children in the form-focused and meaning-focused tasks. A full analysis of regular present tense verb morphology, which is beyond the scope of this study, can be found in Fernández-Dobao and Herschensohn (Reference Fernández-Dobao and Herschensohn2019).

Form-focused task

In the FFPT, for the four stem-changing verbs, the 21 SHL children conjugated a total of 77 forms, the 41 SL2 learners 140 and the 15 SL1 children 58. All these forms take regular inflectional suffixes but require diphthongization of the stem. We analyzed the inflectional suffixes and the stems separately.

The analysis of inflectional morphology – that is, PN, TAM and conjugation class suffixes – indicated that 72 of the 77 stem-changing forms conjugated by the SHL children (that is, 94%) showed correct inflectional morphology. SL2 learners correctly inflected 70% of the verbs analyzed, 98 out of 140; and SL1 speakers performed at 97% accuracy.

To compare the three groups of children we used a mixed-effects logistic regression model with a fixed effect for group and random effects for child and verb. Since intercept-only models may lead to larger Type I error rates (Barr, Levy, Scheepers & Tily, Reference Barr, Levy, Scheepers and Tily2013), we included a by-verb slope for the effect of group. We compared the two models, with and without this slope, using the Akaike information criterion (AIC) (Matuschek, Kliegl, Vasishth, Baayen & Bates, Reference Matuschek, Kliegl, Vasishth, Baayen and Bates2017), where a lower AIC is preferred. We determined the first model, without the slope, was best (AIC = 217.7 versus AIC = 226.0). The results of this model showed that while SHL and SL1 children did not differ in inflectional accuracy (SL1 versus SHL: β = 0.770, z = 0.682, p = 0.495), differences between SL2 and SHL as well as SL2 and SL1 children were significant (SL2 versus SHL: β = -2.355, z = -3.011, p = 0.003 and SL1 versus SL2: β = 3.125, z = 3.052, p = 0.002). In other words, regarding inflectional morphology of stem-changing forms, SHL children performed at the same level as SL1 children, while SL2 learners were significantly less accurate than both SHL and SL1 children.

The results of the analysis conducted on stem accuracy revealed quite a different picture. Only 43 of the 77 stem-changing forms conjugated by the SHL children, 56% of the total, were correctly diphthongized and 30, 39%, were overregularized. These children applied an incorrect stem change to four verb forms, 5% of all forms produced. SL2 learners had an accuracy rate of 32%, for they diphthongized only 45 of the 140 stem-changing forms they conjugated. They overregularized 92 tokens, 66%, and applied a wrong stem change to three, 2%. SL1 children made only one overregularization error, achieving an accuracy rate of 98%.

To examine these differences, we conducted two mixed-effects logistic regression analyses with a fixed effect for group and random effects for both child and verb: a first analysis of accuracy comparing correct versus incorrect (i.e., overregularized plus wrong) stem forms, and a second analysis of error types comparing overregularized versus wrong stem forms. Again, we compared the two models, with and without a by-verb slope. In both cases, we opted for the model without the by-verb slope since it had the lowest AIC value (first analysis: AIC = 266.0 versus AIC = 274.8; second analysis: AIC = 60.3 versus AIC = 70.2).

The first analysis confirmed that accuracy differences were statistically significant. Both SHL and SL1 children were significantly more accurate than SL2 learners (SL2 versus SHL: β = -1.760, z = -2.428, p = 0.015 and SL1 versus SL2: β = 7.096, z = 4.804, p < 0.001), while SL1 children were also significantly more accurate than SHL ones (SL1 versus SHL: β = 5.336, z = 3.740, p < 0.001). Regarding type of errors (i.e., overregularization versus wrong stem), no significant differences were found between any of the three groups: SL2 versus SHL (β = 1.452, z = 1.796, p = 0.073), SL1 versus SL2 (β = 13.967, z = 0.003, p = 0.998), or SL1 versus SHL (β = 16.430, z = 0.011, p = 0.991).

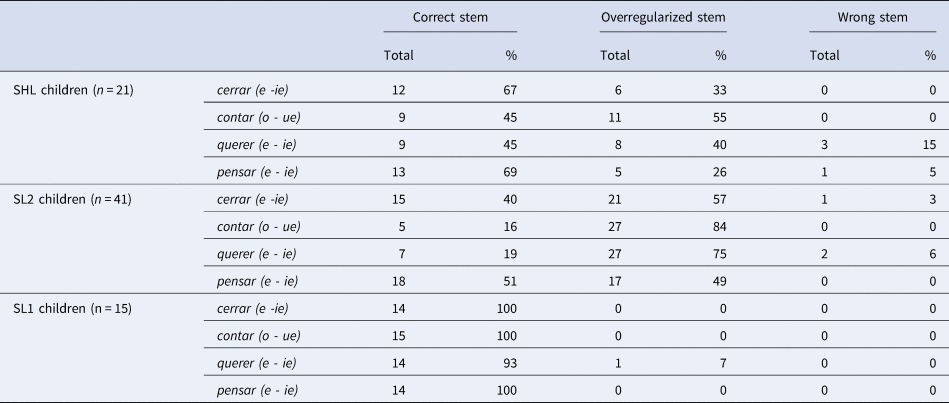

Table 3 presents the results of the individual analysis of each of the four stem-changing forms required by the task. It shows that SHL speakers outperformed SL2 learners in all four verbs. Furthermore, although both groups of bilingual children had some level of difficulty with each of the four verbs, two of them, cuentan ‘they count’ and quieren ‘they want’, had the highest rate of overregularization for both SHL and SL2 children. As for wrong stem errors, they mainly related to quieren. This means that the most problematic forms for the SHL children were also the most difficult ones for the fellow SL2 learners.

Table 3. Individual analysis of stem-changing forms in form-focused task

Meaning-focused task

Since in the MFPT children could choose which verbs to use, their emails varied not only in number of present tense verbs used but also in frequency of regular, stem-changing and irregular forms. SHL children produced a total of 246 present tense forms, 38 of them required diphthongization of the stem and another 127 had an irregularity in the stem, the inflectional suffix, or both. SL2 learners used 508 present tense forms: 183 regular, 95 stem-changing and 230 irregular. Finally, SL1 children produced 185 verb forms, 34 required diphthongization and 98 were irregular. Ignoring regular verbs in this study, we analyzed stem-changing and irregular forms for inflectional accuracy and stem accuracy.

We present first the results of inflectional accuracy: that is, the analysis of PN, TAM and conjugation class suffixes. A mixed-effects logistic regression model with a fixed effect for group and a random effect for child was employed to compare the three groups of children. SHL children performed at the same level as SL1 speakers with a 95% accuracy rate compared to SL1 98% (SL1 versus SHL: β = 1.214, z = 1.307, p = 0.191). SL2 learners, with a 78% accuracy rate, were significantly less accurate than both SHL and SL1 children (SL2 versus SHL: β = -1.826, z = -3.328, p = <0.001 and SL1 versus SL2: β = 3.040, z = 3.631, p = <0.001).

In order to examine overregularization, we analyzed stem-changing and irregular forms separately. The results obtained for these two types of forms are presented in the following two sections.

Stem-changing forms in the meaning-focused task.

In the MFPT SHL children produced a total of 38 stem-changing forms requiring diphthongization of the stem vowel. They correctly diphthongized 28 of them: that is, 74%. They were thus more accurate in this task than in the form-focused one where they showed 56% accuracy for stem-changing forms. The distribution of error types was also different, since SHL children made an equal number of overregularization and wrong stem errors, five of each (13% each of the total). SL2 learners were also more accurate in the MFPT, where they could choose their verbs, than in the FFPT, where they had to use the verbs we had preselected. They used 95 present tense stem-changing forms that required diphthongization. They diphthongized 84 of them, 89% of the total, overregularized six, 6%, and applied a wrong stem change to the remaining five, 5%. SL1 children made no overregularization or wrong stem errors in this task, achieving a 100% accuracy rate.

As we did for the FFPT, we conducted two analyses: an analysis of accuracy, i.e., correct versus incorrect stem forms, and an analysis of error types, i.e., overregularized versus wrong stem forms. Mixed-effects logistic regression with a fixed effect for group and a random effect for child was employed. Results revealed that accuracy differences between the three groups of children were not statistically significant, neither for SL2 versus SHL (β = 1.155, z = 1.286, p = 0.198), nor for SL1 versus SL2 (β = 22.689, z = 0.000, p = 1) or SL1 versus SHL groups (β = 34.08, z = 0.000, p = 1). As for error types, we compared only the SL2 and SHL children, since SL1 children made no stem errors. Differences between the two groups of bilingual children were not statistically significant (SL2 versus SHL: β = 0.182, z = 0.208, p = 0.835).

To better understand these results, we analyzed each of the verb types used by the children separately. As shown in Table 4, all three groups of children used quite a limited range of verb types in their emails. The 34 stem-changing forms identified in the 15 SL1 children's emails belonged to only four different verbs: jugar ‘to play’, querer ‘to want’, recordar ‘to remember’ and tener ‘to have’. The 38 stem-changing forms used by the 21 SHL children belonged to five different verbs: jugar, pensar ‘to think’, querer, tener and venir ‘to come’. Finally, the 95 stem-changing forms conjugated by the 41 SL2 learners were forms of four different verbs: jugar, querer, tener and poder ‘to be able to’. Once again, querer was a leading verb for errors among both SHL and SL2 children. More importantly, 24 of the 34 tokens produced by the SL1 children (71%), 21 of the 38 tokens by the SHL children (55%), and 57 of the 95 tokens by the SL2 learners (60%), were stem-changing forms of the verb tener. This is an extremely frequent verb in Spanish that was used by both SHL speakers and SL2 learners with very high levels of accuracy, 90% and 95% respectively. This explains, at least in part, the high accuracy rate achieved by both groups of bilingual children in this task as opposed to the FFPT.

Table 4. Individual analysis of stem-changing forms in meaning-focused task

Irregular forms in the meaning-focused task.

We now turn to present tense irregular forms, whose irregularity often involves both stem and suffix since they manifest a good amount of suppletion.

SHL children produced a total of 127 irregular forms, applying a wrong irregular stem/suffix to three of them and making no overregularization errors. This means that they achieved an accuracy rate of 98%. SL2 learners performed at a similar level, with a 99% accuracy rate. They used 230 irregular forms and made three stem/suffix overregularization errors but no wrong irregular stem/suffix error. SL1 children made no errors.

Again, two mixed-effects logistic regression analyses with a fixed effect for group and random effect for child were conducted. First, we compared correct versus non-correct (i.e., overregularized plus wrong) irregular stem and/or suffix forms. This analysis yielded no statistically significant differences in accuracy between any of the three groups: SL2 versus SHL (β = 0.605, z = 0.734, p = 0.463), SL1 versus SL2 (β = 28.02, z = 0.000, p = 1), or SL1 versus SHL (β = 28.25, z = 0.000, p = 1). Differences in error types between SHL and SL2 children were also not significant (β = 78.88, z = 0.000, p = 1).

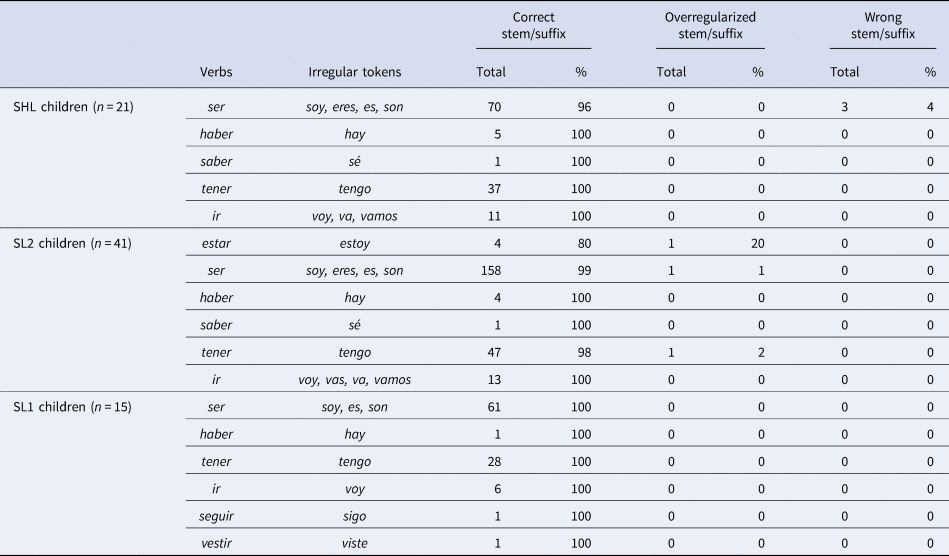

Again, the high level of accuracy achieved by the two groups of dual immersion students, who basically performed at ceiling, seems to be related to the verbs used. As shown in Table 5, SL1 children used irregular forms from six different verbs, SHL children from five and SL2 learners from six. Four of the six irregular verbs used by the bilingual children, ser ‘to be’, haber ‘to be’, estar ‘to be’ and tener ‘to have’, are the four most frequent verbs in Spanish (http://spanishlinguist.us/2014/02/the-most-frequent-spanish-verbs-are-irregular/, accessed December 2019). Not surprisingly, bilingual children had almost no difficulties conjugating these four verbs. One advantage of looking at irregulars is that they are the most frequent in daily use, and we see that the children (and adults, notes an anonymous reviewer) do very well with them, whereas SHL and SL2 children often overregularize stem-changing verbs, which are less frequent.

Table 5. Individual analysis of irregular forms in meaning-focused task

Discussion

We now turn to a discussion of our results in terms of the theoretical issues and research questions raised earlier: how do SHL and SL2 children compare to majority Spanish controls in their morphology mastery of stem-changing and irregular present tense Spanish? How does task design – form-focused or meaning-focused – affect morphological accuracy? How well does the Tolerance Principle account for the data from Spanish verb morphology? Is there evidence of: regular rules (accuracy of regular conjugation); mini-conjugation rules (accuracy of stem-changing conjugation); frequency effects (greater accuracy with higher frequency); overregularization of irregulars; no irregularization?

In our analysis of stem-changing and irregular present tense morphology, we found similarities and differences among the three groups. In the FFPT, that elicited production of preselected verb types, SHL children showed native-like mastery of PN and TAM suffixes – that is, mastery of regular rules – but made frequent stem overregularization errors. They performed at a higher level than SL2 learners for stem accuracy, but at a lower level than SL1 children, who were at ceiling. There was, then, a distinction between SHL mastery of inflectional suffixes as compared to stem morphology.

In the FFPT, SL2 children were significantly less accurate than both SHL and SL1 children. Unlike SHL children, SL2 learners had not yet mastered PN and TAM inflections; although with 70% accuracy they were well above chance. However, 66% of the stem-changing forms they conjugated showed overregularization.

The analysis of SHL and SL2 children's performance in the MFPT, where they could choose which verbs to use, revealed a very different picture. While results for inflectional suffixes mirrored those obtained for the FFPT, the analysis of stem accuracy indicated that both SHL and SL2 children performed at higher accuracy than in the FFPT. Furthermore, in their emails, SHL and SL2 children performed at ceiling when conjugating irregular verb forms. In fact, differences between the two groups of bilingual children and between these and the SL1 speakers, who were again at ceiling, did not reach statistical significance for the highly frequent irregular verbs. An analysis of verb types revealed that SHL and SL2 children achieved high levels of accuracy in this task because they used a very limited number of extremely high frequency verb types: ser ‘to be’, tener ‘to have’, haber ‘to be’ or ir ‘to go’. For the bilinguals, the accuracy of the highly frequent irregulars indicates evidence for the Tolerance Principle's prediction of frequency effects.

In sum, SL1 children were at ceiling on all measures regardless of task, whereas SHL and SL2 children showed both similarities and differences with the control group for present tense morphology and a clear effect for task type. We also saw a role for frequency in that the correctly conjugated irregular verbs were among the most frequent verbs in Spanish.

In both tasks, the verb querer ‘to want’ posed an unexpected high level of difficulty to both SHL and SL2 children. Although twelfth in overall frequency, it is a highly irregular verb. In the present tense, it is regular except for the diphthongization of the stem in all forms but first person plural. However, other tenses require irregular transformations that in some cases affect both the stem and the inflectional suffix, e.g., preterite: quise ‘I wanted’. Querer is then unique as compared to the other verbs of the FFPT, for while cerrar ‘to close’, pensar ‘to think’ and contar ‘to count’ undergo diphthongization in the present, they are regular in other tenses.

Stem-changing forms of the verb querer were used by both SHL and SL2 children in the FFPT and the MFPT. SHL children performed similarly in the two tasks. They correctly diphthongized 45% of tokens produced in the FFPT and 50% in the MFPT. However, SL2 learners were noticeably more accurate in the MFPT, where they correctly diphthongized 69% of the forms produced, than in the FFPT, 19% accuracy. Furthermore, an individual learner analysis revealed that 10 out of the 19 SL2 children who used the verb querer in both tasks produced the overregularized stem quer- in the FFPT and the correct diphthongized stem quier- in the MFPT, suggesting that the association between infinitive querer and its conjugated forms was not yet strong enough. In terms of the Tolerance Principle, it appears that for both bilingual groups the mini-paradigm for querer, with its three stems and irregular inflectional endings, has not been well established, resulting in variation in the production tasks.

Despite differences between the two tasks, overall the data analyzed confirmed that there was overregularization in SHL and SL2 bilingual production, thus providing support for the Tolerance Principle. While overregularization was common for bilingual children, there was only one instance of irregularization, salgen for salen ‘they go out’ produced by an SL2 learner in the FFPT. Overregularization was more frequent in the FFPT, where children had to conjugate preselected verbs, than when they chose their own verbs. These two points, overregularization and lack of irregularization, support Yang's model. Furthermore, the differences in stem accuracy evinced by the different verbs (cf. the individual analysis of verb types in Table 3) indicates that the acquisition, storage and accessing of verbal inflection was neither singular nor binary. In the MFPT, both SHL and SL2 children were more accurate in their use of irregular forms than stem-changing forms. According to the Tolerance Principle, stem-changing forms should be produced with a “mini-rule” for the mini-conjugation, whereas the irregulars such as suppletive soy ‘I am’ would be learned as tokens. The results indicate that majority language controls had mastered the mini-conjugations, but the SHL and SL2 children had not. Rather, these bilinguals were overregularizing stem-changing verbs, while at the same time using irregular tokens correctly. Their accuracy on the highly frequent irregulars, their overregularizations of stem-changing forms, and the clear importance of frequency (as indicated by the high accuracy of the irregulars and the more frequent stem-changing verbs) favors the more complex probabilistic model proposed by Yang. As for the other two morphology models, single mechanism predicts frequency effects and overregularization, while dual mechanism predicts frequency effects, overregularization and rules. However, neither gives as detailed and motivated an explanation of the acquisition and access processes as does Yang's model, which accounts well for the mini-conjugations. Indeed, the inconsistency of the stem-changing mini-rule (even within a single child's production) by the SHL and SL2 children indicates the lack of complete mastery by the bilingual children (as compared to the controls’ ceiling mastery of the mini-rule). The single and dual models do not address the issue of mini-conjugations. Finally, the regular conjugations clearly were rule-governed as indicated by the near-ceiling performance of SHL and SL1 children and the developing 70% inflectional accuracy of the SL2 learners.

Our results serve to illustrate the benefits of dual immersion programs for both minority and majority language speaking children, while at the same time pointing out some of their limitations. Potowski (Reference Potowski2007) and more recently Tedick and Young (Reference Tedick and Young2014) noticed that in two-way immersion programs HL children may not be reaching their minority language learning potential. As also seen in the current study, they observed that, after several years in the immersion context, learners developed functional language proficiency but were not grammatically as accurate as age-matched speakers raised in Spanish speaking countries. On this basis, they argued for explicit language instruction and a focus on language alongside content in the immersion setting – see also Howard, Christian and Genesee (Reference Howard, Christian and Genesee2004). It is an open question whether the children in our study will eventually acquire full mastery of stem-changing present tense morphology. Yet, the results of the analysis of SL2 and SHL production after five years of immersion suggest that the input received by these children, and in particular by the L2 learners, was not enough for the acquisition of the more complex stem-changing verb forms and therefore some form of explicit instruction may be necessary or at least beneficial.

Conclusions

In sum, the current study has provided evidence of overregularization for both SHL and SL2 children, while virtually no instances of irregularization were identified. The analysis of the overregularization and stem errors made by the bilingual children support Yang's Tolerance Principle and his probabilistic model for linguistic rules and exceptions.

Significant differences were observed between the SHL, SL2 and Spanish majority children who participated in the study, as well as between the form-focused and meaning-focused tasks. SL1 children, 9–10 years-old, showed full mastery of present tense regular, stem-changing and irregular morphology. Age-matched SHL children, after five years of dual immersion and enriched Spanish input, performed at the same level as SL1 children in terms of regular inflectional morphology, but still made frequent overregularization errors. SL2 children were significantly less accurate than both SHL and SL1 children in terms of both stem accuracy and inflectional morphology. These differences were evident when children were required to use a set of preselected verbs, as in the FFPT. When children could choose which verbs to use, as was the case for the open-ended MFPT, they limited themselves to extremely high frequency verbs, which they knew well, thus achieving high levels of accuracy.

The SHL and SL2 children in our study had received five years of Spanish and English instruction through a 50:50 dual immersion program. The results obtained suggest that future research, focusing on older children, is needed to determine whether immersion students in a minority language environment can eventually acquire full mastery of Spanish stem-changing present tense morphology. Additionally, to assess the full potential of dual immersion programs for development of the minority language, comparable data should be collected from age-matched SHL children receiving mainstream English language instruction. Research along these lines would contribute to our understanding of the role of both input and instruction in HL as well as L2 acquisition.

Acknowledgements

We thank the teachers who helped facilitate our collection of data, María Buceta, María Guzman, Teresa Colell and David González Gándara. We thank Dr. Michele Shaffer for the statistical analysis of the data in the study. We thank Kristen Piepgrass and Alec Sugar for transcribing and coding the data.

Appendix A

Form-focused production task sample

¿Qué hace? ‘what does she do?’

BORRAR ‘to erase’:

_______________________________

_______________________________

Expected response:

Borra la pizarra ‘she erases the whiteboard’

Appendix B

Meaning-focused production task prompt

Escribe un correo electrónico (email) a un niño español que quiere ser tu amigo por correspondencia (pen pal). Háblale de ti y de tu familia: ¿cómo eres? ¿cómo son tus padres? ¿tienes hermanos o hermanas? ¿cómo son?… Háblale de tus hobbies y de tus amigos: ¿cómo son? ¿qué les gusta hacer en su tiempo libre? ¿qué deportes practican? ¿cuál es tu juego favorito?… todo lo que creas que él debe saber de ti para ser tu amigo.

Write an email to a Spanish child who wants to be your pen pal. Tell him/her about yourself and your family: how are you? how are your parents? do you have any siblings? how are they?… Tell him about your hobbies and your friends: how are they? what do they like doing in their free time? what sports do they play? what is your favorite game?… anything you think s/he should know about you to be your friend.